Sarah L. Johnson's Blog, page 110

January 2, 2014

Book review: The Lost Duchess, by Jenny Barden

Jenny Barden’s second book, a stand-alone sequel to her

Mistress of the Sea

, moves smoothly from Old World court etiquette to New World exploits. There are comparatively few novels that imagine the Elizabethan Golden Age from the perspective of its explorers, and even fewer about the lost Roanoke colonists, so The Lost Duchess deserves a warm welcome for those reasons alone.

Jenny Barden’s second book, a stand-alone sequel to her

Mistress of the Sea

, moves smoothly from Old World court etiquette to New World exploits. There are comparatively few novels that imagine the Elizabethan Golden Age from the perspective of its explorers, and even fewer about the lost Roanoke colonists, so The Lost Duchess deserves a warm welcome for those reasons alone.Its heroine is an appealingly spirited young woman with a strong heart for adventure, and other highlights include the many beautiful descriptions of Virginia, a land of glorious, unspoiled wilderness and life-threatening perils.

For lady-in-waiting Emme Fifield, a baron’s daughter, joining the expedition to form the first permanent English colony in America solves many problems. She’ll avoid the damaging repercussions of a scandal not of her making while escaping her rigid life in London and satisfying her yearning for freedom.

Emme promises to come home on the Lion’s return voyage and provide intelligence on the expedition to Queen Elizabeth and Francis Walsingham. To keep her plans secret, she’s advised to take a new name and travel as the maidservant of Eleanor Dare, daughter of colony governor John White. However, she has every intention of remaining in Virginia. Meanwhile, complicating her life is her growing attraction to master boatswain Kit Doonan, who has a complicated past of his own – and personal reasons for wanting to sail to Roanoke.

Readers get to experience every aspect of Emme and Kit’s journey alongside them: the dangerous lurches of the ship during storms at sea, the pride of the “planters” in their newly constructed City of Raleigh, and the pair’s tender romance, a selfless love that serves to make them both stronger. The colonists’ relations with the Indians are presented with complexity, from the Secotans’ hostility to English incursion – which, it has to be said, isn’t unjustified – to the heroic efforts of Manteo, the settlers’ Croatan ally, to preserve the peace. Emme comes to play a greater role in the colony’s planning than one would expect of an unmarried female servant, but many of its leaders either know or suspect that she’s more than she seems.

Mysteries surrounding the colony’s past, present, and future create an underlying sense of unease that heightens as the answers come to light. What tragedies befell the previous Roanoke settlement, and why? What reasons lie behind pilot Simon Ferdinando’s navigational choices? And since readers will know the new colony is doomed, how will Emme and Kit’s story end?

The language has an authentic period flavor without feeling fusty, and The Lost Duchess movingly expresses the sense of exhilaration and amazement felt by Emme at the natural beauty of Roanoke Island: “How to marvel at wonders without name? She could only relish through her senses like a child before mastering language: enjoying the sight of a bird like a flame in the trees, a vivid flash of vermilion; see gourds like luscious melons, and flowers taller than she was with heads of radiant suns…”

Moreover, it also captures the distress she and Kit feel at the wrenching decisions they and the others are forced to make, and at the realization that there’s an unavoidable price to be paid for their daring venture. It’s a well-rounded portrait in that respect, and Emme and Kit, both of whom are fictional characters, fit comfortably into known events. They both make for good companions on this exciting journey to the New World.

The Lost Duchess was published by Ebury/Random House UK in hardback (£16.99) and trade pb (export edition, £12.99) in November (432pp). Thanks to the publisher for sending me a copy at my request. Unfortunately there's no US publisher as yet, though it's available at Amazon UK and at Book Depository via ABE.

Published on January 02, 2014 11:08

December 27, 2013

Book review: The Mountain of Light, by Indu Sundaresan

Indu Sundaresan’s newest novel opens with an author’s note on the events surrounding the 186-carat Kohinoor diamond’s controversial journey from India to England. It’s an unusual choice to include this information up front, but to her credit, the story isn’t any less dramatic for knowing its outline in advance.

Indu Sundaresan’s newest novel opens with an author’s note on the events surrounding the 186-carat Kohinoor diamond’s controversial journey from India to England. It’s an unusual choice to include this information up front, but to her credit, the story isn’t any less dramatic for knowing its outline in advance. What the author’s note tells, the rest of the novel shows. Gracefully written with an underlying somber tone, The Mountain of Light details the personalities, social concerns, and deeply felt emotions behind the politics.

Five distinct episodes are related in chronological order. In the first, set in 1817, Shah Shuja, the former ruler of Afghanistan, lives in Lahore’s lush Shalimar Gardens as a “guest” of Maharajah Ranjit Singh, who sets the Kohinoor as the price of Shuja’s freedom. The last, set in a Paris apartment in 1893, focuses on Dalip Singh, Ranjit’s son, the deposed last ruler of the Punjab. As an elderly man, he looks back on his arrival in England nearly forty years earlier when, as a 16-year-old boy, he was forced to watch his empire being dismantled and the Kohinoor taken away. Tying all of the strands together are the glorious diamond and the tightening grip of the British and their East India Company on India.

Seen from the viewpoints of individuals from both countries, the stories are full of both great and foolish men; intelligent, forceful women; cross-cultural romances that don’t pan out; and promises that aren’t kept. While many of the British are sympathetic to the Indian people and realize the destructive effects of their presence (“We’re not a very friendly people, are we?” remarks Fanny Eden, sister of Governor-General Lord Auckland), the tragedy of their situation is laid bare. Even the guardians of young Dalip Singh, as kind and loving as they are to him, are left powerless against the forces of imperialism.

Along the way, the Kohinoor changes hands multiple times, by means of deception and theft or as a gift given under pressure. One suspenseful chapter takes the form of an adventurous mystery in which the diamond is stolen aboard ship as it’s secretly transported to England. The writing is lush yet focused, with vibrant descriptions of India’s beautiful landscapes and sumptuous treasures.

With its wide-scale historical perspective, The Mountain of Light may not be the best choice for readers who like attaching themselves to a single protagonist; as literary fiction, also, it deserves to be read slowly and carefully. Most of the characters once lived, which makes the reading an enjoyable educational experience. All in all, it’s an insightful and enlightening look at historical change and how one of the world’s largest diamonds came to take its place in the British crown jewels, a status that’s still contentious today.

The Mountain of Light was published by Washington Square Press/Simon & Schuster in trade paperback in October ($16.00 / $18.99 Canada, 314pp, plus detailed afterword, glossary, and readers' guide). Thanks to the publisher for sending me a copy at my request. See also Indu Sundaresan's guest post on this site: The Journey of the Kohinoor Diamond.

Published on December 27, 2013 13:12

December 24, 2013

My year-end wrap-up: 15 memorable reads of 2013

Over the past few weeks, I've enjoyed reading other bloggers' list of notable 2013 reads but have hesitated to write up my own list until now – mainly because December wasn't yet over, and I still had plenty of reading time ahead over the holiday break! Now, as Christmas is nearly upon us and the year is truly winding down, I figured this was a good time for a year-end wrap-up post.

Here's a list of historical novels I read over the last year that I highly recommend and which stood out for one reason or another. I read many very good novels last year, so choosing them wasn't easy. I decided to expand the list to 15 titles since narrowing it down to 10 left out too many I wanted to include. I'll have more to say on a few of these books once the full reviews are published elsewhere.

Wishing all of you a happy holiday season and another good year of reading in 2014!

Susan Wittig Albert, A Wilder Rose - A meticulously researched, insightful look at a fascinating woman, Rose Wilder Lane, that grants her her rightful place as the ghostwriter for her mother's Little House books.

Susan Wittig Albert, A Wilder Rose - A meticulously researched, insightful look at a fascinating woman, Rose Wilder Lane, that grants her her rightful place as the ghostwriter for her mother's Little House books.

Patricia Bracewell, Shadow on the Crown - The author's skilled use of language and fine sense of dramatic timing brings to life the little-known story of Emma of Normandy, the “peaceweaver” bride of Æthelred II, King of England.

Jessica Brockmole, Letters from Skye - A romantic read set during both world wars that evokes the immediacy and intimacy to be found in the lost art of letter-writing.

Emma Donoghue, Frog Music - The seedy side of 1870s San Francisco features in this original literary mystery in which a French burlesque dancer pursues the killer of her only real friend, pants-wearing frog catcher Jenny Bonnet. Watch for it next April.

Tom Franklin and Beth Ann Fennelly, The Tilted World - A suspenseful, emotionally moving novel about the Great Flood of 1927 that resurrects this nearly forgotten natural disaster and showcases the talents of both authors, who have won awards for their fiction and poetry, respectively.

Tom Franklin and Beth Ann Fennelly, The Tilted World - A suspenseful, emotionally moving novel about the Great Flood of 1927 that resurrects this nearly forgotten natural disaster and showcases the talents of both authors, who have won awards for their fiction and poetry, respectively.

Elizabeth Gilbert, The Signature of All Things - A wonderfully old-fashioned epic, embodying the spirit of the transformative 19th century, that never tones down the intelligence of its scientifically-minded heroine.

Nancy Horan, Under the Wide and Starry Sky - Brimming with the same artistic verve that drives her complicated protagonists, this spectacular literary epic follows the loving, tumultuous partnership of Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson and his Indiana-born wife, Fanny Osbourne.

Dorothy Love, Carolina Gold - A beautiful evocation of the life of a female rice planter in Reconstruction-era South Carolina who gradually comes to terms with her changing world; based on a true story. Full review to come.

Henning Mankell,

A Treacherous Paradise

- The unique historical setting (1905 Mozambique) and courageous heroine distinguish Mankell's suspenseful standalone novel, which depicts the tragic effects of colonialism.

Henning Mankell,

A Treacherous Paradise

- The unique historical setting (1905 Mozambique) and courageous heroine distinguish Mankell's suspenseful standalone novel, which depicts the tragic effects of colonialism.

Mary Miley, The Impersonator - In her debut mystery, Miley takes a world that has vanished into the shadows of nearly a century ago – 1920s-era vaudeville – and pulls it back onto center stage.

Shona Patel, Teatime for the Firefly - In this immersive, romantic historical novel, the author's warm storytelling invites readers to the tea plantations of Assam in 1940s India.

Timothy Schaffert, The Swan Gondola - Magical wonders abound in the former frontier town of Omaha as it welcomes visitors to the 1898 World's Fair, and a ventriloquist falls in love with a beautiful traveling actress Look for it next February.

Lisa See, Snow Flower and the Secret Fan - A longtime book club favorite in which See consummately re-creates the inner lives, relationships, and rituals of women living in a remote province of 19th-century China.

Lisa See, Snow Flower and the Secret Fan - A longtime book club favorite in which See consummately re-creates the inner lives, relationships, and rituals of women living in a remote province of 19th-century China.

Elisabeth Storrs, The Golden Dice - Recounting the perspective of three women of the warring lands of ancient Etruria and Rome, this second novel in a series (following the excellent The Wedding Shroud) offers a much wider view of the era than the first, and is an even stronger book as a result.

Victoria Wilcox, Inheritance: Southern Son, Book 1, The Saga of Doc Holliday - This first volume in a series reveals John Henry Holliday's little-known origins as a son of the Old South: a sensitive yet hot-tempered young man whose early life, in the hands of this talented storyteller, proves every bit as fascinating as his legend.

Here's a list of historical novels I read over the last year that I highly recommend and which stood out for one reason or another. I read many very good novels last year, so choosing them wasn't easy. I decided to expand the list to 15 titles since narrowing it down to 10 left out too many I wanted to include. I'll have more to say on a few of these books once the full reviews are published elsewhere.

Wishing all of you a happy holiday season and another good year of reading in 2014!

Susan Wittig Albert, A Wilder Rose - A meticulously researched, insightful look at a fascinating woman, Rose Wilder Lane, that grants her her rightful place as the ghostwriter for her mother's Little House books.

Susan Wittig Albert, A Wilder Rose - A meticulously researched, insightful look at a fascinating woman, Rose Wilder Lane, that grants her her rightful place as the ghostwriter for her mother's Little House books.Patricia Bracewell, Shadow on the Crown - The author's skilled use of language and fine sense of dramatic timing brings to life the little-known story of Emma of Normandy, the “peaceweaver” bride of Æthelred II, King of England.

Jessica Brockmole, Letters from Skye - A romantic read set during both world wars that evokes the immediacy and intimacy to be found in the lost art of letter-writing.

Emma Donoghue, Frog Music - The seedy side of 1870s San Francisco features in this original literary mystery in which a French burlesque dancer pursues the killer of her only real friend, pants-wearing frog catcher Jenny Bonnet. Watch for it next April.

Tom Franklin and Beth Ann Fennelly, The Tilted World - A suspenseful, emotionally moving novel about the Great Flood of 1927 that resurrects this nearly forgotten natural disaster and showcases the talents of both authors, who have won awards for their fiction and poetry, respectively.

Tom Franklin and Beth Ann Fennelly, The Tilted World - A suspenseful, emotionally moving novel about the Great Flood of 1927 that resurrects this nearly forgotten natural disaster and showcases the talents of both authors, who have won awards for their fiction and poetry, respectively.Elizabeth Gilbert, The Signature of All Things - A wonderfully old-fashioned epic, embodying the spirit of the transformative 19th century, that never tones down the intelligence of its scientifically-minded heroine.

Nancy Horan, Under the Wide and Starry Sky - Brimming with the same artistic verve that drives her complicated protagonists, this spectacular literary epic follows the loving, tumultuous partnership of Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson and his Indiana-born wife, Fanny Osbourne.

Dorothy Love, Carolina Gold - A beautiful evocation of the life of a female rice planter in Reconstruction-era South Carolina who gradually comes to terms with her changing world; based on a true story. Full review to come.

Henning Mankell,

A Treacherous Paradise

- The unique historical setting (1905 Mozambique) and courageous heroine distinguish Mankell's suspenseful standalone novel, which depicts the tragic effects of colonialism.

Henning Mankell,

A Treacherous Paradise

- The unique historical setting (1905 Mozambique) and courageous heroine distinguish Mankell's suspenseful standalone novel, which depicts the tragic effects of colonialism.Mary Miley, The Impersonator - In her debut mystery, Miley takes a world that has vanished into the shadows of nearly a century ago – 1920s-era vaudeville – and pulls it back onto center stage.

Shona Patel, Teatime for the Firefly - In this immersive, romantic historical novel, the author's warm storytelling invites readers to the tea plantations of Assam in 1940s India.

Timothy Schaffert, The Swan Gondola - Magical wonders abound in the former frontier town of Omaha as it welcomes visitors to the 1898 World's Fair, and a ventriloquist falls in love with a beautiful traveling actress Look for it next February.

Lisa See, Snow Flower and the Secret Fan - A longtime book club favorite in which See consummately re-creates the inner lives, relationships, and rituals of women living in a remote province of 19th-century China.

Lisa See, Snow Flower and the Secret Fan - A longtime book club favorite in which See consummately re-creates the inner lives, relationships, and rituals of women living in a remote province of 19th-century China. Elisabeth Storrs, The Golden Dice - Recounting the perspective of three women of the warring lands of ancient Etruria and Rome, this second novel in a series (following the excellent The Wedding Shroud) offers a much wider view of the era than the first, and is an even stronger book as a result.

Victoria Wilcox, Inheritance: Southern Son, Book 1, The Saga of Doc Holliday - This first volume in a series reveals John Henry Holliday's little-known origins as a son of the Old South: a sensitive yet hot-tempered young man whose early life, in the hands of this talented storyteller, proves every bit as fascinating as his legend.

Published on December 24, 2013 11:00

December 19, 2013

Book review: Under the Wide and Starry Sky, by Nancy Horan

Horan’s spectacular second novel (following book-club favorite Loving Frank, 2007) has been worth the wait. Brimming with the same artistic verve that drives her complicated protagonists, it follows the loving, tumultuous partnership of Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson and his Indiana-born wife, Fanny Osbourne.

Horan’s spectacular second novel (following book-club favorite Loving Frank, 2007) has been worth the wait. Brimming with the same artistic verve that drives her complicated protagonists, it follows the loving, tumultuous partnership of Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson and his Indiana-born wife, Fanny Osbourne.Fanny, an aspiring artist still tied to her unfaithful first husband when they meet in 1875, is fiery, courageous, and the mother of two living children. Louis, a younger man whose frailty belies a joyous, energetic spirit, dreams of writing full-time. While he perfects his craft, she becomes his protector and editor-collaborator, accompanying him across Europe and America and finally to Samoa in hopes of healing his weak lungs.

This is more than just another novel designed to honor the unsung accomplishments of a famous man’s spouse, though. Equally adventurous and colorful, Louis and Fanny could each command the story singlehandedly. Together, they are riveting and insightfully envisioned, with moving depictions of how their relationship transforms over time. Horan also explores relevant social concerns, such as cultural imperialism and xenophobia, and how Stevenson’s life influenced his literary themes.

An exhilarating epic about a free-spirited couple who traveled the world yet found home only in one another.

Under the Wide and Starry Sky will be published by Ballantine in January (hb, $26.00, 496pp). I wrote up this starred review for Booklist's October 1st issue, then I reread the novel a second time in order to interview the author for next February's Historical Novels Review. This is a long book, and it took me a good week and a half to read initially, time very well spent; I discovered many additional nuances upon a second reading.

Published on December 19, 2013 11:06

December 11, 2013

Revolutionary Fiction: A Gallery of New and Forthcoming Titles about America's Founding

A story should, to please, at least seem true,Be apropos, well told, concise, and new:And whenso'er it deviates from these rules,The wise will sleep, and leave applause to fools.– Benjamin Stillingfleet, uncredited quote in Ben Franklin's Poor Richard's Almanack (1757)

A few years ago, when my library hosted a traveling exhibit entitled "Benjamin Franklin: A Search of a Better World," I put together a smaller exhibit on historical novels set around the time of the American Revolution. To set off the display, which I called Revolutionary Fiction, I found a witty, relevant quote from Franklin's Poor Richard's Almanack and included it on a placard alongside. (As I discovered this week when trying to find the quote again, Franklin had actually borrowed the words of an English poet without crediting him, as many of his contemporaries did, but I hadn't known that! I do like the quote regardless.)

Just in the last year, many historical novelists have jumped onto the early American bandwagon. While some have often made their home in this setting, such as Sally Cabot and Sharyn McCrumb, others are newcomers whose passion for their chosen period comes through on the pages. I was also thrilled to see that Stephanie Dray, whose 3rd novel about Cleopatra's daughter Selene was published this month, will be coauthoring a novel about Patsy Jefferson, America's First Daughter, with novelist-historian Laura Kamoie.

If this is a new trend, it's a most welcome one in my view. American settings often suffer from the perception that they're dreary and unexciting compared to those taking place in England or Europe, but nothing could be further from the truth! Below is a gallery of nine new and forthcoming novels set during the Revolutionary years, and all present fresh angles on this iconic period. If you enjoy this era, consider adding them to your reading list.

Benjamin Franklin – American patriot, diplomat, politician, writer, inventor – had an eye for the ladies. In her fourth work of historical fiction set in early America (after three written as Sally Gunning), Cabot brings to life the little-known story of his illegitimate son William, who was raised by his stepmother, Franklin's common-law wife Deborah, and who took the Loyalists' side in the War of Independence. William Morrow, May 2013.

Gabaldon's immensely popular historical fiction series needs no introduction, but the later volumes have served to introduce many new readers to the personalities and politics of the American Revolution. The eagerly awaited 8th novel in her Outlander saga, a thousand-page doorstopper, opens in the year 1778, right in the middle of the war, as Jamie Fraser learns that his beloved wife Claire married another man during the time she thought he was dead. From the blurb, Benedict Arnold is a major character here, too. Delacorte, June 2014.

In Massachusetts in 1763, as revolution looms on the horizon, a learned young woman from a well-off background defies her family to pursue a relationship with a country lawyer with patriotic leanings. I understand the plot is loosely based on the courtship of Abigail and John Adams. Hedlund writes detail-rich romantic stories for the inspirational market, though mainstream readers can enjoy them too. Bethany House, September 2013.

In her Ballad Novels, McCrumb has always delved deeply into the resonant folklore of the people from the Appalachian Mountains, but this is her first set during the Revolutionary era. Here she recounts the heroic story of the Carolina Overmountain Men and of their leader, John Sevier, one of her ancestors. Thomas Dunne, September 2013.

This debut novel imagines the life story of Deborah Samson, a strapping young woman from Middleboro, Massachusetts, who escapes her dreary life of toil in 1782 by disguising herself as a man and running away to join the Continental Army. Myers' insightful novel is based on the extraordinary service of the real-life Deborah; I've read it and can recommend it. Simon & Schuster, January 2014.

The name Peggy Shippen may not ring a bell for any but dedicated American history fans, but the name Benedict Arnold is another story. Pataki's debut novel aims to change that; it reveals Peggy's role as the orchestrator of the plot that turned her decorated war hero husband into America's greatest traitor. The publisher is playing up the author's family connections (she's the daughter of former NY governor George Pataki). Howard Books/S&S, January 2014.

This is the only Revolutionary-era novel in the bunch that isn't for sale in the US, which I find more than passing strange, especially considering it won the Ellis Peters Historical Dagger for 2013. Andrew Taylor's historical thriller is set in Manhattan, a haven for British Loyalists whose lives were upended by American rebels. Harper UK, July 2013 (this is the hardback cover).

In this romantic adventure novel set in Boston of 1775, a pirate's daughter takes her future into her own hands when she takes a British naval officer hostage on her family's ship in Boston Harbor. Second in the Renegades of the Revolution series after The Turncoat. NAL, March 2014.

Turner's new historical epic steps further back in time to the year 1729, when Resolute Talbot is stolen away from her Jamaican family and sold into slavery in Massachusetts. As a talented weaver in the town of Lexington, she is ideally placed to play a major role in the coming revolutionary tumult. The author's The Water and the Blood, set in '40s East Texas, is one of my favorite historicals, so my anticipation for this one is running high! Thomas Dunne, February 2014.

Published on December 11, 2013 17:00

December 5, 2013

Victoria Patterson's The Peerless Four, an inspiring look at sports and women's history

“I pulled a novel from my purse. Always, I had a book to read... I read to find out what it was like to be a man. To be Russian, Spanish, and French, to be a different race, to be royalty, dirt-poor, a wealthy New Yorker, a homesteader or a gold miner in the pioneer West… I read to find out what it was like in another’s skin.”

“I pulled a novel from my purse. Always, I had a book to read... I read to find out what it was like to be a man. To be Russian, Spanish, and French, to be a different race, to be royalty, dirt-poor, a wealthy New Yorker, a homesteader or a gold miner in the pioneer West… I read to find out what it was like in another’s skin.” This may seem an odd way to begin a review of a sports novel. However, the wise words of Marybelle Eloise Lee “Mel” Ross, the tough yet perceptive woman who chaperones the Canadian women’s track team on their trip to the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics, explain why I wanted to read Victoria Patterson’s The Peerless Four. Competitive sports have only ever interested me as a spectator, so I wanted this novel to take me somewhere I’d never been: into the mindset of a group of young women whose determination and physical prowess took their world by storm.

It should be said up front that this work is more thoughtful than action-oriented. It celebrates the women’s accomplishments and provides glimpses of them in practice and competition, but it also succeeds in illustrating the social expectations for women in the '20s. The era didn’t treat its female athletes kindly. They were seen by many as unnatural creatures who might damage their uteri through vigorous exercise, destroying their chances of motherhood. Five track events at the 1928 Olympics were opened to women on a trial basis, so the future of the sport rested on their young shoulders. That they developed the mental stamina that let them thrive in these controversial circumstances is, quite simply, amazing.

Mel, who narrates most of the story, is a great character, a former runner and sports reporter who reads novels and keeps a personal journal – and who also keeps a flask of whisky hitched to her garter for the times when she needs it. She relates well to her charges and helps keep them focused as they train for victory and make their way by ship from Toronto to Amsterdam. Mel has her own gender-based expectations to surmount, since her husband, a bigwig in Canadian amateur athletics, would have preferred her to stay home.

The young women, dubbed the “Peerless Four” by the media, travel in a group that also includes Jack Grapes, their cigarette-smoking, Cadillac-driving sponsor, an ex-hockey player himself, and their team coach. Each of the four speaks in a short biographical segment in the beginning, providing background details on her life.

There’s Muriel Ziegler, nicknamed “Farmer,” the popular team captain who gets dinged by the press for her “masculine” attributes but is the most independent and grounded of the four. She has a terrific outlook on life, and I just loved her. Ginger Hadley is the team’s star high jumper, the enigmatic “Dream Girl” whose gorgeous looks attract swarms of admirers but who hates their misplaced attention and withdraws into herself as a consequence. High school student Bonnie Brody is a runner whose love for her married coach nearly crushes her, and Flo Smith is a single-minded athlete and good team player who hates academics but adores sports.

How everyone copes with the immense competitive and social pressures they all face is the novel’s main theme. For these groundbreaking women, as Muriel puts it, “We had to work things out for ourselves. We were the first ones to try, so there was no one to copy.” As their inspiring tale unfolds, Patterson’s spare, concentrated writing contains many subtle yet unmissable touches of irony. In her account, Mel shares relevant newspaper clippings she'd collected – such as an 1886 article about a race for women in which the prize was a silver dinner service! She also retells an instructive story about a distant relative which, at 16 pages, is unnecessarily lengthy, but nothing else in this short work feels out of place.

I found The Peerless Four well worth reading for its convincing characterizations and its eye-opening look at what early women athletes had to overcome, and the paths they blazed for their present-day successors. That said, it's never stated that the characters are fictitious. The 1928 Canadian women’s track team was actually called “The Matchless Six,” and Ginger Hadley is obviously based on Ethel Catherwood, the pretty “Saskatoon Lily” whose gold medal-winning high jump is shown on the cover (the photo description on the jacket gives her name).

This technique may have been ethically liberating for its author, and it doesn’t diminish the power of the writing, but the real Olympians whose lives are borrowed for the story deserve to be acknowledged in it. An author’s note would have gone far in preventing confusion between fact and fiction.

The Peerless Four was published by Counterpoint in October ($23.00, hb, 212pp). Thanks to the author's publicist for sending me a copy at my request.

Published on December 05, 2013 16:30

December 1, 2013

Bits and pieces: Staycation edition

Happy December! Today's the last day in a five-day stretch where I did very little except read, sleep, eat, and go shopping – a break I seriously needed. I don't normally get the chance to get this much reading done, but I've finished a book for every day I've been home.

First up was Mary-Rose MacColl's In Falling Snow, set at the Royaumont field hospital in France during WWI and in 1970s Australia. I wrote up my thoughts for the Historical Novels Review and will post them here later.

Next was Lynn Shepherd's A Treacherous Likeness, a twisting literary mystery in which London private detective Charles Maddox is asked by Sir Percy Shelley, son of the poet, and his wife Jane to investigate a case of blackmail. This sets him into looking closely at members of the Shelley Circle and into his own family history. The plot held my attention to the end, and the author was very clever in inserting her mystery into known events. All the same, I found some revelations historically unconvincing and the depiction of one real-life character ethically troubling.

Third was Barbara Davis' The Secrets She Carried, a family saga/mystery in which secrets (as you can guess from the title) from a small town in 1930s North Carolina emerge in the present day. Just my type of thing. This was a Kindle purchase; I hadn't requested a review copy for the HNR since I hadn't known the historical component was so prevalent, but since it was, I decided I should review it.

Finally, and to mark the halfway point in my TBR Pile Challenge, I read Lisa See's Snow Flower and the Secret Fan. By far it was my favorite choice out of the five I've read so far. It's the type of book that left me feeling somewhat dazed after I finished because I was so immersed in the story of Lily, her laotong bond of friendship with Snow Flower, and the author's consummate re-creation of the inner lives, relationships, and rituals of women in their remote province of 19th-century China. It's easy to see why it was a bestseller and book club favorite. See has taken a place and time that very few outsiders know and made it not only accessible but movingly real.

Now I'm on to a fifth book in five days, Victoria Patterson's The Peerless Four, about the Canadian women's track and field team in the 1928 Olympic Games, and hope to have a review up soon.

Some other news updates:

I learned some sad news via Facebook recently. T.D. (Tim) Griggs, who contributed a guest post here in April ("The Boer War: Britain's Vietnam"), passed away suddenly in October. Tim was the author of numerous works of fiction, most recently Distant Thunder, set in India, Britain, and the Sudan during Victorian times. He had won a book in my giveaway for Small Press Month and, in the course of our correspondence, kindly offered to write a post for my site. My sympathies to his wife and family.

I've been debating whether to commemorate Small Press Month again next March. If I do, I'll include some reviews of non-small press books during that time because removing an entire month from my blog schedule created a backlog, but I'm unsure how much effort to put into it otherwise. Any thoughts?

On this topic, one of my more popular small press giveaways was for Sarah Kennedy's The Altarpiece, about a nun living through Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries; the author contributed a guest post in May. Her book came out in paperback ($14.00) in October.

Finally, since I've gotten questions about this here and elsewhere on social media – I did send a note to the Library of Congress via their website comment form about the "Puritan maiden's diary," with a citation and link to Mary Beth Norton's article. It may be a little while until it reaches the right person and gets investigated by their staff, but I've found LC quick to respond to questions and comments in other instances and am hopeful that will be the case here too.

First up was Mary-Rose MacColl's In Falling Snow, set at the Royaumont field hospital in France during WWI and in 1970s Australia. I wrote up my thoughts for the Historical Novels Review and will post them here later.

Next was Lynn Shepherd's A Treacherous Likeness, a twisting literary mystery in which London private detective Charles Maddox is asked by Sir Percy Shelley, son of the poet, and his wife Jane to investigate a case of blackmail. This sets him into looking closely at members of the Shelley Circle and into his own family history. The plot held my attention to the end, and the author was very clever in inserting her mystery into known events. All the same, I found some revelations historically unconvincing and the depiction of one real-life character ethically troubling.

Third was Barbara Davis' The Secrets She Carried, a family saga/mystery in which secrets (as you can guess from the title) from a small town in 1930s North Carolina emerge in the present day. Just my type of thing. This was a Kindle purchase; I hadn't requested a review copy for the HNR since I hadn't known the historical component was so prevalent, but since it was, I decided I should review it.

Finally, and to mark the halfway point in my TBR Pile Challenge, I read Lisa See's Snow Flower and the Secret Fan. By far it was my favorite choice out of the five I've read so far. It's the type of book that left me feeling somewhat dazed after I finished because I was so immersed in the story of Lily, her laotong bond of friendship with Snow Flower, and the author's consummate re-creation of the inner lives, relationships, and rituals of women in their remote province of 19th-century China. It's easy to see why it was a bestseller and book club favorite. See has taken a place and time that very few outsiders know and made it not only accessible but movingly real.

Now I'm on to a fifth book in five days, Victoria Patterson's The Peerless Four, about the Canadian women's track and field team in the 1928 Olympic Games, and hope to have a review up soon.

Some other news updates:

I learned some sad news via Facebook recently. T.D. (Tim) Griggs, who contributed a guest post here in April ("The Boer War: Britain's Vietnam"), passed away suddenly in October. Tim was the author of numerous works of fiction, most recently Distant Thunder, set in India, Britain, and the Sudan during Victorian times. He had won a book in my giveaway for Small Press Month and, in the course of our correspondence, kindly offered to write a post for my site. My sympathies to his wife and family.

I've been debating whether to commemorate Small Press Month again next March. If I do, I'll include some reviews of non-small press books during that time because removing an entire month from my blog schedule created a backlog, but I'm unsure how much effort to put into it otherwise. Any thoughts?

On this topic, one of my more popular small press giveaways was for Sarah Kennedy's The Altarpiece, about a nun living through Henry VIII's Dissolution of the Monasteries; the author contributed a guest post in May. Her book came out in paperback ($14.00) in October.

Finally, since I've gotten questions about this here and elsewhere on social media – I did send a note to the Library of Congress via their website comment form about the "Puritan maiden's diary," with a citation and link to Mary Beth Norton's article. It may be a little while until it reaches the right person and gets investigated by their staff, but I've found LC quick to respond to questions and comments in other instances and am hopeful that will be the case here too.

Published on December 01, 2013 07:00

November 26, 2013

A Puritan Maiden's Diary: The Early American Primary Source that Wasn't

As part of the requirements for the Plagues, Witches, and War historical fiction MOOC I've been participating in this fall, students were asked to complete an archival assignment. We were to choose and describe a primary source new to us that we'd found in an online or bricks-and-mortar archive, then write a short descriptive essay about it – including, if we liked, details on how we might use it as the basis for a work of historical fiction.

The following essay isn't what I turned in for the class. However, I found the background research for one archival item that I examined so startling and enlightening that I wanted to write it up for inclusion here anyway. And so we have...

A Puritan Maiden's Diary:

The Early American Primary Source that Wasn't

The primary source I had initially selected for the assignment is entitled “A Puritan Maiden's Diary.” One of the education departments at Eastern Illinois University, where I work as a librarian, has a web page that links out to several online archives whose contents were judged useful for teaching purposes. One of them is the website of the Library of Congress, which has a section entitled Pages from Her Story that contains the text of women’s historical diaries, letters, and memoirs.

The first example in their list of resources, a diary written by a 15-year-old girl from Rhode Island in 1675-77, fit my interests perfectly. I’m originally from New England and especially enjoy reading about life in the colonial period. In addition, this particular diary called to mind Geraldine Brooks’ Caleb’s Crossing, one of my favorite novels about the era. Both recount culture clashes in Puritan times from the viewpoint of an educated young woman.

The first example in their list of resources, a diary written by a 15-year-old girl from Rhode Island in 1675-77, fit my interests perfectly. I’m originally from New England and especially enjoy reading about life in the colonial period. In addition, this particular diary called to mind Geraldine Brooks’ Caleb’s Crossing, one of my favorite novels about the era. Both recount culture clashes in Puritan times from the viewpoint of an educated young woman.

When I read the text of the diary, hosted at the Library of Congress’ American Memory Project, I was fascinated by the illustrative details this unnamed girl recorded, as well as her eloquence. Here’s the first paragraph, dated December 5, 1675:

I am fifteen years old to-day, and while sitting with my stitchery in my hand, there came a man in all wet with the salt spray. He had just landed by the boat from Sandwich, which had difficulty landing because of the surf. I myself had been down to the shore and saw the great waves breaking, and the high tide running up as far as the hillocks of dead grass. The man, George, an Indian, brings word of much sickness in Boston, and great trouble with the Quakers and Baptists; that many of the children throughout the country be not baptized, and without that, religion comes to nothing. My mother has bid me this day put on a fresh kirtle and wimple, though it not be the Lord's day, and my Aunt Alice coming in did chide me and say that to pay attention to a birthday was putting myself with the world's people. It happens from this that my kirtle and wimple are no longer pleasing me, and what with this and the bad news from Boston my birthday has ended in sorrow. (Slicer, 1894, p. 20)

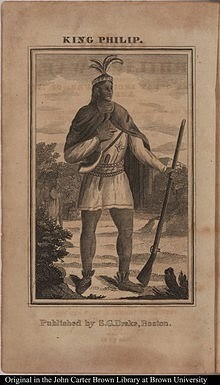

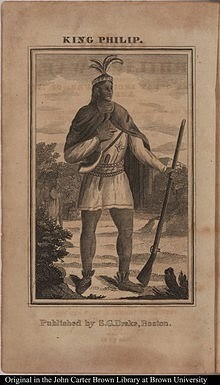

King Philip, as interpreted by a later artist

King Philip, as interpreted by a later artist

In particular, the girl was a keen observer of King Philip’s War (the bloody Native American uprising against the English colonists in 1675-78, named after the Wampanoag chief Metacomet, who was called “King Philip” by the English). In her journal, she documented her family’s reactions to her uncle Benjamin’s (“Captain Church”) involvement in the fighting; her internal struggle between observing proper Puritan behavior and her desire to enjoy life; repairs to her family’s house; day-to-day events like preparing meals; and the contrast between her humble life in Rhode Island and that in Boston, where she was sent for her safety.

An excerpt from her words on the latter:

Through all my life I have never seen such an array of fashion and splendor as I have seen here in Boston. Silken hoods, scarlet petticoats, with silver lace, white sarconett plaited gowns, bone lace and silken scarfs. The men with periwigs, ruffles and ribbons. (p. 24)

The diary is presented by Adeline E. H. Slicer, a 19th-century historian, who wrote that she came across it in her travels. She published the contents in New England Magazine in September 1894. (Cornell University has the scanned images of Slicer’s article in their Making of America journal archive.) In her article, Slicer added her own editorial commentary and clarifications on what the girl wrote so her contemporaries would understand the historical background. To my mind, this “Puritan maiden’s diary” perfectly exemplified one of the themes Geraldine Brooks spoke about in her MOOC course lecture: that although customs change, human nature remains constant despite the passage of time.

I was also thrilled to see that Slicer, in her historical asides, mentioned the name of a colonial-era relative of mine, the Rev. James Keith of Bridgewater, Massachusetts, who felt sorry for the son of King Philip, a young boy who would likely be enslaved after his father was killed. (Rev. Keith was married to the sister of my direct ancestor, Samuel Edson of Bridgewater.) A search that began at my university’s website eventually ended at a resource that cited a member – albeit a distant one – of my family. How’s that for synchronicity?

The Rev. James Keith Parsonage, West Bridgewater, Mass.

The Rev. James Keith Parsonage, West Bridgewater, Mass.

When I worked at Bridgewater State College, I drove by this house all the time.

And yet... the diary somehow seemed too perfect. Over the next few hours, I began to have uneasy feelings about its provenance, even though its presence on the LoC website seemed to verify its authenticity. Basically, the girl helpfully noted so many things which later generations would likely want to know about that place and time, such as clothing, food and drink, religion, and larger events happening all around her but which she didn’t personally take part in. She seemed all too aware that she was writing for posterity.

She also described many situations that would make it easy for modern, secular readers to relate to her. As in: she told of how she wanted to fall asleep during a lengthy church sermon one afternoon. I found it odd that with so many names of relatives listed in the text, Adeline Slicer wasn't able to supply the girl’s name; Slicer also gave no details on where and how she found the journal, its physical description, or where the book was kept. I also began to wonder whether a teenage girl from Puritan America would have written a diary in the first place.

She also described many situations that would make it easy for modern, secular readers to relate to her. As in: she told of how she wanted to fall asleep during a lengthy church sermon one afternoon. I found it odd that with so many names of relatives listed in the text, Adeline Slicer wasn't able to supply the girl’s name; Slicer also gave no details on where and how she found the journal, its physical description, or where the book was kept. I also began to wonder whether a teenage girl from Puritan America would have written a diary in the first place.

So I began googling around for more information… and found, alas, just what I was looking for.

An email message on a history discussion list from Brigham Young University’s Jenny Hale Pulsipher (2003) listed the diary’s purported author as “Hety Shepard” and expressed her doubts about it, despite finding it in an online primary source database. “I am convinced that it is a 19th century invention,” Pulsipher wrote. “It is riddled with anachronisms, one of the most glaring of which is the diarist’s exact quotation of Benjamin Church’s description of Philip (Metacom) years before Church's account was written or published… [but] the few mentions of it that showed up on a general internet search seem to accept it as genuine.”

However, conclusive proof of the diary’s fabrication came from Mary Beth Norton, Professor of American History at Cornell – an award-winning scholar, incidentally, whose In the Devil’s Snare has the most persuasive argument I’ve read for the reasons behind the Salem witchcraft accusations. In an article for the Journal of Women’s History (1998), Norton demonstrates that that the “so-called Puritan Maiden’s Diary” is a unquestionably a fake written by Adeline Slicer herself.

Little Compton, RI (formerly Saconet), the supposed residence of "Hetty Shepard"

Little Compton, RI (formerly Saconet), the supposed residence of "Hetty Shepard"

(and where her real-life uncle, Captain Benjamin Church, is buried)

The evidence is considerable: lack of genealogical connections between the family members included in the diary; the unlikely possibility that clerics named in the journal would have traveled to “preach to a tiny congregation in the wilds of Plymouth Colony” (p. 147); the surprising insider knowledge about events not widely known at the time; and several anachronisms, “the clincher” being the diarist’s citing of the date of an infamous Indian massacre using the Gregorian-style calendar – which wasn’t in use in the British colonies until 1752 (p. 148). Therefore, per Norton, the diary must have been composed after that year.

What was presented to me as a primary source dating from the 1670s turned out to be a primary source of a different kind from the 1890s – and a very convincing piece of historical fiction at that! Works of historical fiction not only evoke the period they describe, but also the time at which they’re written, and, as Norton has uncovered (and others have suspected), this one betrayed many clues to its true late 19th-century origins.

In conclusion, although the class's archival assignment didn’t turn out at all as I intended, it was still an instructive and eye-opening exercise. If there’s a moral to this story, it’s that researchers, historical fiction writers included, need to be skeptical of the historical sources they find. Rather than taking them at face value, we need to trust our gut if they seem suspicious and thoroughly investigate the circumstances behind their creation.

References

Norton, M. B. (1998). Getting to the source: Hetty Shepard, Dorothy Dudley, and other fictional colonial women I have come to know altogether too well. Journal of Women’s History, 10, 141-54. doi:10.1353/jowh.2010.0311

Pulsipher, J. H. (2003, Oct. 14). “A Puritan Maiden's Diary” by Hety Shepard. Message posted to http://www.h-net.org/~ieahcweb/

Slicer, A. E. H. (1894). A Puritan maiden’s diary. The New England Magazine, 17, 20-25. Retrieved from http://digital.library.cornell.edu/n/newe/index.html

The following essay isn't what I turned in for the class. However, I found the background research for one archival item that I examined so startling and enlightening that I wanted to write it up for inclusion here anyway. And so we have...

A Puritan Maiden's Diary:

The Early American Primary Source that Wasn't

The primary source I had initially selected for the assignment is entitled “A Puritan Maiden's Diary.” One of the education departments at Eastern Illinois University, where I work as a librarian, has a web page that links out to several online archives whose contents were judged useful for teaching purposes. One of them is the website of the Library of Congress, which has a section entitled Pages from Her Story that contains the text of women’s historical diaries, letters, and memoirs.

The first example in their list of resources, a diary written by a 15-year-old girl from Rhode Island in 1675-77, fit my interests perfectly. I’m originally from New England and especially enjoy reading about life in the colonial period. In addition, this particular diary called to mind Geraldine Brooks’ Caleb’s Crossing, one of my favorite novels about the era. Both recount culture clashes in Puritan times from the viewpoint of an educated young woman.

The first example in their list of resources, a diary written by a 15-year-old girl from Rhode Island in 1675-77, fit my interests perfectly. I’m originally from New England and especially enjoy reading about life in the colonial period. In addition, this particular diary called to mind Geraldine Brooks’ Caleb’s Crossing, one of my favorite novels about the era. Both recount culture clashes in Puritan times from the viewpoint of an educated young woman. When I read the text of the diary, hosted at the Library of Congress’ American Memory Project, I was fascinated by the illustrative details this unnamed girl recorded, as well as her eloquence. Here’s the first paragraph, dated December 5, 1675:

I am fifteen years old to-day, and while sitting with my stitchery in my hand, there came a man in all wet with the salt spray. He had just landed by the boat from Sandwich, which had difficulty landing because of the surf. I myself had been down to the shore and saw the great waves breaking, and the high tide running up as far as the hillocks of dead grass. The man, George, an Indian, brings word of much sickness in Boston, and great trouble with the Quakers and Baptists; that many of the children throughout the country be not baptized, and without that, religion comes to nothing. My mother has bid me this day put on a fresh kirtle and wimple, though it not be the Lord's day, and my Aunt Alice coming in did chide me and say that to pay attention to a birthday was putting myself with the world's people. It happens from this that my kirtle and wimple are no longer pleasing me, and what with this and the bad news from Boston my birthday has ended in sorrow. (Slicer, 1894, p. 20)

King Philip, as interpreted by a later artist

King Philip, as interpreted by a later artistIn particular, the girl was a keen observer of King Philip’s War (the bloody Native American uprising against the English colonists in 1675-78, named after the Wampanoag chief Metacomet, who was called “King Philip” by the English). In her journal, she documented her family’s reactions to her uncle Benjamin’s (“Captain Church”) involvement in the fighting; her internal struggle between observing proper Puritan behavior and her desire to enjoy life; repairs to her family’s house; day-to-day events like preparing meals; and the contrast between her humble life in Rhode Island and that in Boston, where she was sent for her safety.

An excerpt from her words on the latter:

Through all my life I have never seen such an array of fashion and splendor as I have seen here in Boston. Silken hoods, scarlet petticoats, with silver lace, white sarconett plaited gowns, bone lace and silken scarfs. The men with periwigs, ruffles and ribbons. (p. 24)

The diary is presented by Adeline E. H. Slicer, a 19th-century historian, who wrote that she came across it in her travels. She published the contents in New England Magazine in September 1894. (Cornell University has the scanned images of Slicer’s article in their Making of America journal archive.) In her article, Slicer added her own editorial commentary and clarifications on what the girl wrote so her contemporaries would understand the historical background. To my mind, this “Puritan maiden’s diary” perfectly exemplified one of the themes Geraldine Brooks spoke about in her MOOC course lecture: that although customs change, human nature remains constant despite the passage of time.

I was also thrilled to see that Slicer, in her historical asides, mentioned the name of a colonial-era relative of mine, the Rev. James Keith of Bridgewater, Massachusetts, who felt sorry for the son of King Philip, a young boy who would likely be enslaved after his father was killed. (Rev. Keith was married to the sister of my direct ancestor, Samuel Edson of Bridgewater.) A search that began at my university’s website eventually ended at a resource that cited a member – albeit a distant one – of my family. How’s that for synchronicity?

The Rev. James Keith Parsonage, West Bridgewater, Mass.

The Rev. James Keith Parsonage, West Bridgewater, Mass. When I worked at Bridgewater State College, I drove by this house all the time.

And yet... the diary somehow seemed too perfect. Over the next few hours, I began to have uneasy feelings about its provenance, even though its presence on the LoC website seemed to verify its authenticity. Basically, the girl helpfully noted so many things which later generations would likely want to know about that place and time, such as clothing, food and drink, religion, and larger events happening all around her but which she didn’t personally take part in. She seemed all too aware that she was writing for posterity.

She also described many situations that would make it easy for modern, secular readers to relate to her. As in: she told of how she wanted to fall asleep during a lengthy church sermon one afternoon. I found it odd that with so many names of relatives listed in the text, Adeline Slicer wasn't able to supply the girl’s name; Slicer also gave no details on where and how she found the journal, its physical description, or where the book was kept. I also began to wonder whether a teenage girl from Puritan America would have written a diary in the first place.

She also described many situations that would make it easy for modern, secular readers to relate to her. As in: she told of how she wanted to fall asleep during a lengthy church sermon one afternoon. I found it odd that with so many names of relatives listed in the text, Adeline Slicer wasn't able to supply the girl’s name; Slicer also gave no details on where and how she found the journal, its physical description, or where the book was kept. I also began to wonder whether a teenage girl from Puritan America would have written a diary in the first place. So I began googling around for more information… and found, alas, just what I was looking for.

An email message on a history discussion list from Brigham Young University’s Jenny Hale Pulsipher (2003) listed the diary’s purported author as “Hety Shepard” and expressed her doubts about it, despite finding it in an online primary source database. “I am convinced that it is a 19th century invention,” Pulsipher wrote. “It is riddled with anachronisms, one of the most glaring of which is the diarist’s exact quotation of Benjamin Church’s description of Philip (Metacom) years before Church's account was written or published… [but] the few mentions of it that showed up on a general internet search seem to accept it as genuine.”

However, conclusive proof of the diary’s fabrication came from Mary Beth Norton, Professor of American History at Cornell – an award-winning scholar, incidentally, whose In the Devil’s Snare has the most persuasive argument I’ve read for the reasons behind the Salem witchcraft accusations. In an article for the Journal of Women’s History (1998), Norton demonstrates that that the “so-called Puritan Maiden’s Diary” is a unquestionably a fake written by Adeline Slicer herself.

Little Compton, RI (formerly Saconet), the supposed residence of "Hetty Shepard"

Little Compton, RI (formerly Saconet), the supposed residence of "Hetty Shepard"(and where her real-life uncle, Captain Benjamin Church, is buried)

The evidence is considerable: lack of genealogical connections between the family members included in the diary; the unlikely possibility that clerics named in the journal would have traveled to “preach to a tiny congregation in the wilds of Plymouth Colony” (p. 147); the surprising insider knowledge about events not widely known at the time; and several anachronisms, “the clincher” being the diarist’s citing of the date of an infamous Indian massacre using the Gregorian-style calendar – which wasn’t in use in the British colonies until 1752 (p. 148). Therefore, per Norton, the diary must have been composed after that year.

What was presented to me as a primary source dating from the 1670s turned out to be a primary source of a different kind from the 1890s – and a very convincing piece of historical fiction at that! Works of historical fiction not only evoke the period they describe, but also the time at which they’re written, and, as Norton has uncovered (and others have suspected), this one betrayed many clues to its true late 19th-century origins.

In conclusion, although the class's archival assignment didn’t turn out at all as I intended, it was still an instructive and eye-opening exercise. If there’s a moral to this story, it’s that researchers, historical fiction writers included, need to be skeptical of the historical sources they find. Rather than taking them at face value, we need to trust our gut if they seem suspicious and thoroughly investigate the circumstances behind their creation.

References

Norton, M. B. (1998). Getting to the source: Hetty Shepard, Dorothy Dudley, and other fictional colonial women I have come to know altogether too well. Journal of Women’s History, 10, 141-54. doi:10.1353/jowh.2010.0311

Pulsipher, J. H. (2003, Oct. 14). “A Puritan Maiden's Diary” by Hety Shepard. Message posted to http://www.h-net.org/~ieahcweb/

Slicer, A. E. H. (1894). A Puritan maiden’s diary. The New England Magazine, 17, 20-25. Retrieved from http://digital.library.cornell.edu/n/newe/index.html

Published on November 26, 2013 11:00

November 24, 2013

Book review: The Emperor's Agent, by Jo Graham

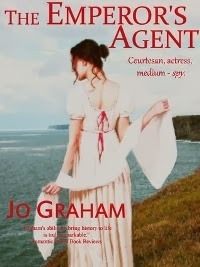

This invigorating follow-up to

The General’s Mistress

finds its heroine, Dutch courtesan-actress Elzelina Ringeling, aka Ida St. Elme, in a tough spot. It’s 1805 in Paris, and she’s being blackmailed by Fouché, the Minister of Police, into informing on people from her past. A crucial choice on her part brings her to Napoleon, who charges her with flushing out a spy who’s been feeding his invasion plans to England. Arriving in the coastal city of Boulogne, she finds herself in way over her head. There are many highly-placed suspects, and as she tries to scout for the traitor, she’s forced into the company of Michel Ney, her soul mate, who had previously left her to marry someone else.

This invigorating follow-up to

The General’s Mistress

finds its heroine, Dutch courtesan-actress Elzelina Ringeling, aka Ida St. Elme, in a tough spot. It’s 1805 in Paris, and she’s being blackmailed by Fouché, the Minister of Police, into informing on people from her past. A crucial choice on her part brings her to Napoleon, who charges her with flushing out a spy who’s been feeding his invasion plans to England. Arriving in the coastal city of Boulogne, she finds herself in way over her head. There are many highly-placed suspects, and as she tries to scout for the traitor, she’s forced into the company of Michel Ney, her soul mate, who had previously left her to marry someone else. Elza is one of the most distinctive characters in Napoleonic-era fiction. She is based on a real person whose provocative journals (Mémoires d’une Contemporaine) gained her considerable renown, and through her eyes, we observe both the feminine demi-monde as well as the camaraderie and banter among officers in the Grande Armée. A woman of her times, Elza acknowledges gender constraints while boldly fashioning her own way of life within them. Dressed as her alter ego Charles van Aylde – or in shedding her male garb when slipping into bed with an understanding lover – she can embrace the other side of her nature.

With this sequel, Graham brings readers fully into the realm of historical fantasy as her reincarnation themes become more prominent, and Elza comes to accept her clairvoyant abilities. One of the most enjoyable aspects is that the novel’s mystical tone isn’t limited to these scenes; the descriptive language simply glows as it awakens us to the realization that all around us is a place of marvels. Not only a beguiling story of political espionage, self-discovery, and deeply felt love in early 19th-century Europe, it also gives us a creative and enchanting way of envisioning these characters’ world.

The Emperor's Agent was published by Crossroad Press in September (290pp, $15.99 pb / $27.99 hb / $4.99 ebook). This review first appeared in November's Historical Novels Review.

Published on November 24, 2013 08:00

November 21, 2013

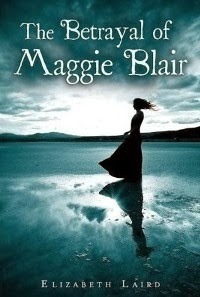

For the TBR Pile Challenge: The Betrayal of Maggie Blair, by Elizabeth Laird

Entry in the 2013 TBR Pile Challenge: #4 out of 12

Entry in the 2013 TBR Pile Challenge: #4 out of 12Years on TBR: 2

Edition owned: Houghton Mifflin, 2011 (hb, 423pp)

I haven't been keeping up well with the TBR Pile Challenge, with only four books read so far in 2013. (I made an attempt with a fifth, Diana Norman's Daughter of Lir , but have put it aside.) On my original list of twelve, I noted the following for Elizabeth Laird's The Betrayal of Maggie Blair: "YA historical about an accused witch in 17th-century Scotland... adventure, religious repression, and so forth. I don't read much YA but should."

A brief synopsis: Maggie Blair, a sixteen-year-old orphan living in a ramshackle cottage with her sharp-tongued Granny on Scotland's Isle of Bute in the 1680s, narrowly escapes to the Scottish mainland after she and her grandmother are condemned as witches. After reaching safety at her uncle Hugh's wealthy estate of Ladymuir, Maggie learns about her relatives' religious beliefs and political stance – Hugh is a Covenanter who rejects the king's interference in the Presbyterian Church – and unwittingly brings danger to their doorstep.

What impressed me: The Scottish Lowlands in the late 17th century is a setting virtually untouched in fiction, and The Betrayal of Maggie Blair presents the reign of Charles II from a less familiar, revelatory perspective. Here the king is a distant figure living in sinful splendor in London while denying his Presbyterian subjects the freedom to select their own bishops and worship as they choose. Hugh Blair is a man of deep religious principles (he's a historical character based on the author's ancestor) who's willing to martyr himself for his cause.

I admired how Laird depicts her characters' strong faith and the moral conflicts it engenders. Through Maggie's eyes, readers see how her uncle's choices, while they may be justified, negatively affect his wife and children. There are no simple answers, and other mature themes are presented as well, but Laird doesn't talk down to her readers at any point. I also appreciated the book's dark, moody tone and the descriptions of the heather-covered hillocks and other aspects of the landscape as Maggie travels over land and water.

Maggie is an engaging and courageous protagonist who stays true to herself even when it costs her. She longs to be a wife and mother someday but knows her circumstances won't allow it – so accepts it and gets on with her life. Her conflicted relationship with her Granny feels realistic, and although Maggie finds one itinerant preacher attractive and charismatic, no romantic subplot is forced upon readers, something I found refreshing.

I was less enamored of some characters' actions (I underlined "really stupid behavior" twice in my notes). Nobody deserves to be accused or convicted of witchcraft, but with her habit of placing curses on people who make her mad, Maggie's spiteful Granny goes out of her way to attract her neighbors' suspicions. Also, Maggie's aunt is extremely gullible, taking the side of a pretty, young stranger over Maggie's and not realizing she's nurturing a viper in her own household.

The jacket design evokes a fantastical atmosphere (and the girl's curvy, slender silhouette resembles a historical Bond girl more than a flesh-and-blood teenager), but there are no supernatural elements here, just a detailed exploration of Scottish folk customs and beliefs at this time and place. Also, the plot is paced more slowly than other YAs I've read; it's not quite an exciting adventure but thoughtful and character-centered, which suits the storyline.

Finally, for me personally, there was one amusing glitch: one minor character is alternately called both Sarah and Susan. This happens to me all the time!

Despite some frustrating moments, I recommend the novel for YAs and adults as a thought-provoking look at women's roles and people's complicated relationships with each other and with God in late 17th-century Scotland. A note that in the UK its title is The Witching Hour.

Published on November 21, 2013 09:00