Mary Beard's Blog, page 36

March 25, 2014

Prisoners and their books

OK, there has been a lot of steam about the issue of prisoners not being allowed to be sent books (or most other gifts) from the outside. And no, it is not the case -- and most of us never claimed it was -- that books are to be banned in prisons. The precise details of the new regime (since last November) are clearly explained by the Howard League here.

But as the interview with the prisons minister, Jeremy Wright, on the Today programme this morning made clear, there is still loads to be anxious about. The first thing was that he was unwilling actually to discuss the issue with author Mark Haddon, but apparently insisted on being interviewed separately. Never a good sign when a minister wont discuss.

His first point was that prisoners had access to prison libraries. Well fine: but how well are prison libraries funded? what kind of ordering system is in place, with what kind of cash limits (will they really order a £50 book on twentieth-century painting)? and how often does the average prisoner get access to them? From what I have heard on the grapevine -- and there's no surprises here --prison libraries aren't immune from the kind of cuts that are afflicting public libraries. But it would nice to have some details of funding and opening hours if anyone has them. (And, as a friend asked today, what about books in foreign languages? Not all prisoners have English as their first language.)

Wright also said that prisoners could buy books if they wanted. But Mark Haddon and others have pointed out that these books have to be chosen from one catalogue (he wouldn't say which catalogue -- does anyone know that?). And with what money? The average work-earnings for a prisoner inside is about £8 a week, and that's for everything. Even if he or she spent all of it on books, £8 a week isnt going to go very far. Knight then said that they could have money sent to them from outside in order to buy. But how much? Is there no limit on the cash you can send a prisoner? (Again, I'd like some info here.)

All this seems to be driven by saving money on the appropriate security checks for incoming parcels. But it simply misunderstands how the pleasures and benefits and restorative potential of books can actually work. It's not always -- or even usually -- through picking something (cheap) from a catalogue.. it's often through someone saying, "I think you'd like this... I really enjoyed it.. why not borrow it". It's about being encouraged to try something new, to explore further interests you are only just discovering.

Amongst everything else, it's that kind of opening which is getting cut off here too.

And as Mark Haddon said, even the prisoners in Guantanamo can be sent books.

March 22, 2014

Problems with the Crimea -- ancient style

No, I'm not about to contribute to the "Crimea debate". Though I must say that I wish most of the media would stop writing about Russian actions as if they were somehow the equivalent of France aggressively annexing East Anglia. Whatever the wrongs and rights here (and there are plenty of wrongs), the status of the Crimea isn't anything like as simple as that.

Throughout the 20th century Crimea was "liminal" territory, and only "given" to Ukraine in 1954 (when Ukraine was a part of the USSR anyway). The recent coverage is mostly a typical example of simplifying a complex history (and then trying to rouse popular feeling -- "a new Cold War" -- on that basis). The Washington Post has been one of the best exceptions to this. Here is a good historical piece; here a critical fact-check on some of Putin's statements, with a different emphasis; and here some comparative examples.

But -- be that as it may -- I did come to reflect this week on what was going on it the Crimea in the ancient world.

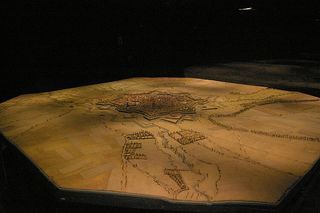

Quite a lot, is the answer.

The Black Sea area was one of the granaries of the Greek world, and various Greek cities sent out "colonies" there -- to the "Tauric Chersonesus" (chersonesus means "peninsula") as they called it. One of the best known is just on the outskirts of modern Sevastapol -- and was known simply as Chersonesus (pictured above). It has been excavated over the last 20 years by a team from the University of Texas and it's just been named a World Heritage Site.

In the Roman period, the region was almost as ambivalent as it is now. It was for centuries (from the end of the fifth century BC) part of the "independent kingdom of Bosporus", and it continued shipping grain to Greece through the Hellenistic period. Underneath this, however, there were changing power block. For a time it was under the control of the famous King Mithradates of Pontus (long term enemy of the Romans, who was eventually defeated by Pompey the Great in 63 BC); in fact, Mithradates died in one of the other towns in the Crimea, originally a Greek (Milesian) colony, Panticapaeum (modern Kerch). The tombstone of the Bosporan soldier above is from there.

For hundred of years, until the fourth century AD, the kingdom (including most of the Crimea) remained a client kingdom of Rome; that is, in a (formally) quasi-independent state, but de facto part of the Roman empire ("puppet kingdom" might be a better word). But it was always a perilous state. And in the reign of the emperor Nero there was a (Putin-style??) attempt to annex the region fully, and for a few years it was incorporated into the province of Moesia. But that turned out to be only temporary, part of some ambitious expansionist plans of the emperor.

But if all this sounds relatively cosy, dont forget that this was the place where Agamemnon's daughter, Iphigeneia ended up -- after she had been spirited away by Artemis from the famous scene where she was due to be sacrificed (left -- to ensure a fair wind for the Greeks trying to reach the Trojan War). As Euripides dramatises it in his Iphigeneia among the Taurians (the Taurians were the inhabitants of the Chersonesos), she was effectively imprisoned, as priestess in a temple, where she presided over the ritual slaughter of visiting foreigners. (There's a good new book on this by Edith Hall.)

But if all this sounds relatively cosy, dont forget that this was the place where Agamemnon's daughter, Iphigeneia ended up -- after she had been spirited away by Artemis from the famous scene where she was due to be sacrificed (left -- to ensure a fair wind for the Greeks trying to reach the Trojan War). As Euripides dramatises it in his Iphigeneia among the Taurians (the Taurians were the inhabitants of the Chersonesos), she was effectively imprisoned, as priestess in a temple, where she presided over the ritual slaughter of visiting foreigners. (There's a good new book on this by Edith Hall.)

So from the centre of the Greco-Roman world, the Crimea could look not just like a bread basket, but a cruelly exotic place of blood and slaughter. Let's hope history doesnt repeat.

March 18, 2014

The "new" British Library -- and "new" Galen

Last night I gave a talk on "ancient libraries" at the AGM of the "Friends of the British Library" -- which I much enjoyed (hope the listeners did too). But there were some ironies about this.

The first was that I have never actually used the new BL. I was a regular reader in the "old" Round Reading Room in the British Museum, pictured above (and, in fact, I carried round my "old" BM library card in my wallet until about 4 years ago when I saw sense). I can't honestly claim an ideological objection to the new library (though some of my mates did -- and fought close to the death for the old regime); I just never quite got round to it, and the longer this went on, the more difficult it proved to fill the form in!

But the second irony was that I was given a subject that lay outside my specialist area; that is, the history of ancient libraries.

There has been a lot of recent work on this (including a very useful collection of essays). And some of this has been kick started by the recent rediscovery (in a Greek library!) of Galen's second-century AD treatise Peri Alupias ("on keeping a stiff upper lip"). It is a discussion of the importance of not giving into grief -- and the prompt for these reflection was the loss of Galen's store room on the Sacred Way in Rome in a devastating fire in 192. The store room contained some silver ware, medical equipment and drugs (Galen was a notable doctor) and a quantity of books. But also destroyed in the fire of 192 were several public imperial libraries, whose loss Galen also discusses (while giving some nice insights into the condition of Roman public libraries: some scrolls were wrongly categorised, environmental conditions (ie damp) were so bad that the scrolls got stuck together and were in practice unopenable.

Anyway in the course of this, I got interested in the whole history of Aristotle's books . . . bequeathed down the generations, coveted by the royal library in Pergamum, eventually taken by Sulla to Italy, and possibly another victim of the fire of 192. It is a great story, and one that reveals the way that particular ancestral collections play a big part in the library culture of the ancient world.

But there was a plus/minus sting in the tail. It was really great to see Anthony Kenny at the talk. But, crikey, he knows a hell of a lot more than me about Aristotle's books. Hoping I got it right.

March 14, 2014

Many Happy Returns

Tomorrow I am off to a very special eightieth birthday lunch. It's in college, and it's to celebrate the three score years and twenty of one of my old undergraduate teachers, Pat Easterling -- a wonderful critic of Greek tragedy, academic friend to at least half the classicists in the world, and the first and only female professor of Greek in the University of Cambridge.

Some 150 of her ex-pupils (almost all from Newnham) are showing up to wish her happy birthday, ranging from those who have remained in the Classics trade to those who have branched into business, law, medicine, theatre ... and almost anything else you can think of. (We'll be living proof that doing a Classics degree opens doors rather than closes them.)

But perhaps the most amazing thing is that the "encomium" to the birthday girl will be given by her (and my) old teacher, Joyce Reynolds, who is herself just coming up to 95 years old, and still doing front line academic work on Roman inscriptions. I imagine there must be something comforting about reaching 80 and still having the applause led by your old teacher.

For me the pleasure will be basking in the joy of still being the little one at age 59, watching my two old teachers still going strong, still ticking me off when I've forgotten something, and still just being there in the way they have been since I was 18. A few months ago Joyce read the whole of the typescript of my book on Laughter, just as she had read my Phd thesis decades ago. (Crikey I thought, when I first sat in her slightly scary study in 1973, would I ever have believed that, 40 years on, I'd still be going round for what amounted to a supervision?)

What's funny is that I know that we must now look a pretty elderly trio to all the new students that come up. But in my eyes Pat and Joyce look just like they have always done -- and, as Joyce herself once said, for her students in a way seem eighteen forever. (Come to think of it, whatever I know he looks like, I still see Mick Jagger as thirty . . .)

But part of the fun will also be meeting all my old student mates among the 150 who are coming -- and the reminiscences that I can already confidently predict we will share (largely because they are always the same). There will be the stories about how we always tried to get taught by Pat at 12.00 or 6.00, because there was a very strong chance that we'd be plied with a glass of sherry (those were the days).

And there will be the terrors of honesty and dishonesty with Joyce. These terrors always tended to cluster around the begining and end of term interviews, when we would be asked to come clean about what we had read (read in Latin or Greek, I mean) over the preceding term or vacation -- books she would then enter on a running list that she kept for each one of us. I soon got the idea that one could look as if one had read more, if one read short things -- and I built up a considerable expertise in the shortest book by every major classical author (shortest play of Euripides, shortest dialogue of Plato etc). But then I discovered Plutarchs Essays (the Moralia). They were a god-send because some of them were only a few pages long.

So after one vacation I brightly volunteered my short plays, my short dialogues, and Plutarch On Right and Wrong. Joyce I recall looked surprised. Why did you choose that, she asked. The temptation to come clean and say "Because it's only 4 pages, FFS" was almost irresistable. But instead I mumbled some complete whoppper about how I had become rather interested in the philosophical culture of Greeks in the Roman empire. She just nodded -- I slunk out of the room, convinced I had been rumbled.

Not as bad as one of my friends, who confidently claimed that (among other things) she had read Virgil's Twelfth Eclogue over the summer. It was only after she got out of the room that it struck her that Virgil had only actually written ten Eclogues. We still wonder whether Joyce had actually spotted the lie, but decided to say nothing, while marking my friend (now a very respectable Head Mistress) down as a callow liar. Or whether she just hadn't noticed.

Back then we were convinced that she would have spotted and would be storing the offence up to refer to darkly in some future job reference. Now, older and more realistic, I tend to suspect that Joyce might not have been quite so interested in this ritual as we fearfully imagined, and that it probably passed her by.

March 9, 2014

Teaching and tears

There has been a great little series on Radio 4: "My teacher is an app". Dont be put off by the title, it's actually a rather telling glimpse at how new technology might (or might not) be making a difference to traditional methods of education. It's featured some scarily enthusiatic people singing the praises of having the teacher electronically linked to their pupils computer (so they can see exactly how they make their mistakes -- balanced by professors in the US worrying about the effect that MOOCS (Massive Open Online Courses) might have on traditional universities and university employment. Why employ a dozen philosophers at a medium sized state university, when you could get the students to watch the MOOCs from Harvard, and employ just a couple of adjuncts as personal back-up and graders? And how democratising are they anyway (there's an interesting article on that here).

Anyway, the last episode of the series is on at 8.00pm tomorrow (Monday), and it's a panel discussion with four experts, and a big audience, including "the nations ten best teachers" -- one of whom (errr yes) is me. Dont worry, I only agreed to go on after being assured that "the ten best teachers" headline was meant light-heartedly (thanks heavens -- as the thought of really getting up the nose of the thousands of far better teachers than me in the nation was not a happy one). It was all recorded a few weeks ago in the Great Hall at King's College London, where I showed up with a little group of my Cambridge students.

The whole thing took about 90 minutes, but it will have been edited down to just under 60. And I am now beginning to wonder which of my contributions will have made the final cut -- and which, maybe thankfully, not.

There is, I confess, a bit of a worry here. Not because I think I said something I didn't mean, but because over the last few weeks, all kinds of things I've said have been picked up by some bit of the press, then by another, then taken entirely out of context, and then used as stick to beat me. Hard not to be a bit pre-occupied in trying to remember EXACTLY what I DID say, and to speculate what might be made of it. (OK, I hear you saying, do you never learn, Beard?)

I DO remember starting off by asking the panel what exactly a MOOC was. This was quite intentional, partly because anyone who hadnt listened to the whole series needed (I thought) a bit of help, and partly because we use the term in very different ways and sometimes pretty loosely -- and it needed a bit of tying down. But in retrospect it was a hostage to fortune of a question. "So, Professor Beard, you've been questioning the virtues of MOOCs this last few weeks, but you dont actually know what they are..."

I also recall that I had a good-humoured set-to with my friend Jonathan Bate, who is very keen on MOOCs and has just made a Shakespeare online course. I'm sure it is excellent, but I did state pretty firmly (and I intended funnily) that -- however good it was -- it would be a truly nightmare scenario if every Shakespeare student in the world was to access the bard through the Bate MOOC (where was diversity...?). What might be made of this? "Controversial classicist scorns Shakespeare scholar"...? (You can bet your bottom dollar that most of the irony will be lost in the telling.)

And finally I remember saying that no computer course could make you cry and that good teaching was always liable to lead to tears. Now this is a favourite, slightly exaggerated, image of mine. It's meant to capture the idea that really learning to THINK can be hard, uncomfortable and actually UPSETTING ... sometimes it HAS to make your head hurt, and make you feel you can't do it. That's what learning really difficult stuff means. It's not all touchy feely, or continual success and smooth progress. Now the truth is I don't think I HAVE ever made a student actually cry (the tears in my study have been caused by all those other prompts to student misery -- from errant partners to distressing parents or not getting a longed for job). But you know what I mean. Can't you just see the headline though. "TV historian admits to terrorising tearful students". . .?

So, as you asked, shouldn't I have learned? Maybe yes, for a quiet life. But there is something totally dispiriting about policing what you say, just in case someone is going to quote it back again at you, misleadingly out of context. That's what leads to political soundbite culture, where the fearful junior minister will never deviate from the ("hardworking families") slogans on his or her prepared script. And we know how ghastly that is.

So bring 'em on.

March 8, 2014

Lent again

As some of you may remember, the husband and I have the habit of giving up alcohol for Lent (here is last year's Lenten bulletin). I caught this from my much missed old editor, Peter Carson (I've linked you to Rodric Braithwaite's wonderful obituary), and this is only the second Lent I have faced without him.

There isn't anything religious in this abstinence for us. It is proof that we can do it, a chance to give the livers a break, and generally an exercise in latter day "moral improvement".

Each year, there is a rather dispiriting round of attempts to find a nice soft drink (is it to be a ginger beer year or a tomato juice one?), and a series of reflections about what our links with the fermented grape (for apart from some signature cocktails, wine is our tipple of choice) actually depend on. It is I have to say, as I have observed before, something of a relief to discover that a desire for a drink is almost overwhelming at 6.30/7.00pm, but has pretty much disappeared by 9.00pm (so this is SOCIAL addiction, right?).

The other question is what exceptions we are to be allowed. On my understanding, the observant Catholic would have a free alcohol pass every Sunday, so reducing the rather more than 40 days between Ash Wednesday and Easter Sunday. Do do we get some days off too?

In the past, I have taken the line that the Lenten rules don't apply abroad, or -- to be more precise -- dont apply airside at an airport and beyond (have never thought that a flight to Los Angeles without a single drink would do me, or my aeroplane neighbours, any good at all). Some years this has resulted in quite a few days off, other years none at all.

So this year, our -- admittedly self-obsessed -- family negotiations have concentrated on getting this sorted in advance. If we have the Catholic allowance of six days, then which are they to be? Well, I think I will be the other side of the Channel for 3 days (so that's the "abroad allowance"). But then maybe there could be a tiny "party allowance"? Perhaps 2 days, which would still keep us within the target six. There's a great book launch coming up, and an Oxford "feast" for me (now given an asterisk in the diary).

But, oh dear, we also had an invitation to a rather good bash last Thursday. It was very tempting to make it the sixth day off. But in the end, we both decided that you couldnt give yourself a free pass just two days in. So fruit juice it had to be -- though, blimey, parties where everyone else is getting nicely mellow and you are stone cold sober, can be hard work. (How on earth do people who regularly dont drink manage? That's the other learning experience of a dry Lent -- makes one realise how silly one is when you've had one or two).

Anyway, at the bash, I bumped into one of my fellow strandees in Delhi, and explained -- to his slight amazement at catching sight of me with a tumbler and a straw -- that I was off the booze for Lent. And I went through the whole litany of how it wasnt for religious reasons, but just to make my self feel better etc. And he elegantly turned on me, to point of that this was only, then, an exercise in self satisfaction and moral arrogance, and that I should have a glass of wine immediately.

I didn't (think of the liver, Beard), but I fear he was right.

March 4, 2014

What I really said about women's voices

After the misleading headlines in reports of my piece in the Radio TImes (making it look as if I was positively encouraging women to lower their voices!).. this is what I actually wrote (as edited by RT). It's a preview of some of the issues in my Public Voice of Women lecture, which is due to be broadcast in mid March.

"What are we going to do about women on television? I don’t mean whether they should be there at all (even grumpy old men don’t want to make tv a male-only zone). I mean, how do we get beyond those niche roles for women in sitcoms – or sitting next to the main (male) presenter on the breakfast tv sofa?

I gave at least two hearty cheers to Danny Cohen, the director of BBC television, when he said a few weeks ago: "We're not going to have panel shows on any more with no women on them. You can't do that. It's not acceptable."

The trouble is that it’s easy enough to agree with Cohen’s instincts, but it’s less easy to see what practical steps the BBC (or any media company) should take. And it’s not just about panel shows.

The underlying “maleness” of all these shows is more hard-wired in our culture than the presence of a few extra women is likely to solve. In my programme, Oh Do Shut up Dear, which is due to air on BBC?? on ?? March, I argue that the “silence” of women in public debate goes right back to the very origins of the Western tradition; and I mean the very origins -- already in Homer’s Odyssey, almost 3000 years ago, we find a wet-behind-the-ears teenager telling his savvy mother not to speak in public. Of course, the Greeks and the Romans didn’t have panel shows. But the kind of male banter and repartee that we still see in these programmes – its aggression, its “wit” – does go back thousands of years to ancient dialogue and debate (where no woman got much of a look in, and where there was plenty of male “willy-waving”).

Of course, there are women who have already gone beyond that. Think of Stephanie Flanders being wonderfully persuasive on economics, or Emily Maitlis who can be as powerful as anyone on Newsnight. But there are still relatively few, and they still tend to be relatively young and conventionally pretty (their looks, perhaps, tending to sugar the pill of hard-core political debate). And there can be an outcry when women move into what are perceived as traditional male areas. Remember the abuse directed at Jacqui Oatley when she dared to “leave the netball court” and become the first woman commentator on Match of the Day.

So what can we do? Quotas are obviously one answer. They can certainly help in the short term: people come to expect to see women right across the television schedules and that in turn encourages women to see themselves there. But, to be honest, I rather dread any idea of a fixed quota of women per programme. It’s likely to leave desperate producers ringing round all the women they can possibly think of to fill “the woman’s slot”. I don’t think it would be much fun being the woman vilified in all the reviews as the one taking the quota place.

Quotas don’t really get to the root of the problem, which has a lot more to do with images of authority that most of us share, than with particular choices made by producers. The fact is that even now authority still seems to reside with the men in suits, and their deep voices; and those are the types we still assume we’ll see when we are looking for words of wisdom on television (or, with a few notable exceptions, in parliament). You need only think of how most viewers accept, without a blink, the craggy, wrinkled faces and bald patches of male documentary presenters, as if they were the signs of mature wisdom; yet in the case of women presenters, grey hair and wrinkles often signal “past-my-use-by- date” – or at least glaring eccentricity and deficient grooming. And it’s not a coincidence that even on radio, the successful women presenters tend to have unusually deep (ie male) voices.

If viewers want to change this, the power lies partly in their hands. We all need to think a bit harder about the assumptions we have about whose face fits the tv screen. Or to put it another way, we’ll know that we have finally bridged the gender gap not when we can point to mixed line-ups on every panel show, but when almost every viewer in the land would simply think that it looked very weird (and unbelievably old-fashioned) to have a panel made up of four blokes -- and would switch off."

March 1, 2014

Feminism or femininity?

I know Twitter may have its downsides. But I've always said that on balance there were more pluses than minuses. And that was nicely illustrated yesterday.

I always imagined that I knew my way rather well around the BBC's website, but until I got yesterday's tweet (thankyou @DrImogenTyler) I hadnt come across their archive section, which has a whole array of programmes and clips on "second wave feminism" mostly from the 1970s, but with a few pieces going back to the 60s, and then up tp the early 1990s.

The clip that Imogen linked me to was this (click on 'this' -- it starts without a picture, but persevere -- you get visuals afater a couple of minutes). It was broadcast on "Tonight" in 1963 just after Oxford had opened up its Union Society to women ("Oxford's given in"), and Cambridge (it was claimed) was the only remaining "unequal" university in the land ("a girl is just a girl") -- though there were compensations, we were assured, in the shape of 10 men dancing attendance on every woman student.

So Chris Brasher, intrepidly, went off to Birmingham (a university for women and men from its very beginning) to interview women students about what they thought of Cambridge and what their own experiences were. Just how equal did women want to be? Did they want feminism or feminity? Did they want to compete with men, or be competed for by men?

What really struck me was the thought that this was the world in which I grew up. I was 8 when this piece of film was made; this is what I (and my mum and dad) would have been watching on television of an evening (at least I THINK we had television then, we were rather later converters). And it all seems so unbelievably foreign.

For a start, the voices. Everyone interviewer spoke like a toff. Then the language. For the most part, when he spoke of the students, Brasher referred to the "men" and the "girls", without apparently a flicker of anxiety at the unequal comparison (which was an instantiation of what he was supposed to be investigating).

And whatever they really thought, most of the women interviewed seemed ambivalent about "girl power". One of the feistiest did express the view that -- nice as Cambridge was (she'd visited for a weekend and came back "feeling ten foot tall") -- she wouldn't want to give up equality. And the editor of the University paper was keen on competing with men and entering the ratrace of journalism, but when it came to marriage, then her man was going to be the dominant partner, please. In fact, the woman who was Secretary of the Birmingham Debating Society was absolutely convinced that the only power worth having was "behind the throne" (if men compete for you, you are more likely to get what you want). That's exactly the power she thought she had as the Secretary, while the Chairman was really in charge.

It is truly gob-smacking. But I came away, after a couple of watchings, feeling hugely cheered. It's easy enough to complain at the slowness of women's path to equality; and it really does sometime feel very slow indeed. But this snapshot of the changes that have been achieved in the last 50 years was a good anitidote to the gloom.

It wasn't just what these women said (which I am sure some people would still agree with), it was the language of the questions and their answers that was so unbelievably different, and their knee-jerk (possibly defensive) reactions about the way marriage would and should work for them. I do wonder what happened to them later (if anyone recognises them do say -- who IS that would-be journalist who wanted domination by her other half?)

Meanwhile the rest of the feminist collection on the website is brilliant too (including a great piece from 1971, about lone women not being served in coffee bars after midnight -- in case they were prostitutes, apparently).

February 25, 2014

The pleasures of Lille

Last week the husband and I went on a day trip to Lille -- to see the Palais des Beaux Arts (which we had been told was a real treasure chest of "arts" and which to our shame we had never visited). We went through a whole load of domestic debates, trying to find a Saturday when we could make a full day to get there. Then we made the brave and obvious decision: as we work seven days a week anyway (that's a confession not a boast), it would be perfectly OK to go on a weekday! So we opted for a Friday.

I cant say (after a quick visit) that Lille is the kind of place that I would like to take a week's holiday, but -- blimey -- the Palais des Beaux Arts is as good as everyone said it was.

On the ground floor, there is a marvellous collection of nineteenth-century sculpture. The hunk at the top of this post is a nineteenth-century Spartacus. But we were especially entranced by the nineteenth-century  French copy, by an artist scholar at the French School in Rome, of the famous "hermaphrodite" (I hadn't quite realised before that this particular piece -- obvious as it might seem -- had been a target for copyists).

French copy, by an artist scholar at the French School in Rome, of the famous "hermaphrodite" (I hadn't quite realised before that this particular piece -- obvious as it might seem -- had been a target for copyists).

And on the basement floor, apart from a few OK bits of Greek pottery etc, there were an extraordinary collection of eighteenth-century landscape relief-models of the countryside and towns around Lille. Never seen anything like them.

But on the first floor, there was a stunning collection of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century classical painting. Above is a version of "Virgil reading the Aeneid to Augustus and Livia" (Octavia is swooning as the poet gets to the bit where we meet the dead Marcellus, her son). And one of my favourites is this picture  on the left of Hippocrates coming to the city of Abdera to try to cure Democritus of his constant laughter (which is something I talk about in my forthcoming book on laughter).

on the left of Hippocrates coming to the city of Abdera to try to cure Democritus of his constant laughter (which is something I talk about in my forthcoming book on laughter).

And that's just a couple of highlights (among a real wealth of stuff), which makes the Eurostar nip (90 minutes) well worth it. Plus, let us recommend, a nice bar in the Museum and a 5 minutes walk a trad. French brasserie in the shape of Brasserie André (dont think you'll get anything nice near the Eurogare Lille, unless we missed something).

But I went away with a real highlight for me, which was back down on thge ground floor, among the gallery devoted to ceramics. What you see below (taken through the glass) islabelled merely as an eigtheenth-century bust. In fact, it is a version of my old friend, the "Grimani Vitellius". And it reminded me that as soon as I have finished my history of Rome, I'm getting back to writing up my project on modern images of Roman emperors.

February 22, 2014

Who should get promoted?

There's a letter in this week's THE, from 50 Cambridge academics, which may interest some readers. It's about the "gender gap" in academic promotions. The basic message (which I am no doubt crudifying) is that the current criteria (formal and practical) for promotion, let's say from Reader to Professor, are too much framed in terms of research publication and research grants, and not enough in terms of teaching, administration, and various other forms of service -- and that this tends to dis-favour women applicants.

I'm hugely pleased that this is all getting a good public airing. And it also raises some interesting questions about how promotions work, or dont, outside areas where there are measurable targets/archievments.

I mean I can see that in commercial selling it might seem fairly simple. Rewards and/or promotion presumably correlate more or less directly with profits achieved. Though even there, there must be some tricky areas. No one wants to promote the guys whose vast sales figures were achieved by terrorising old ladies out of their life savings -- nor those whose only achievement was to clinch the final deal after months of hard work by others (one suspects there could be a gender gap there).

But it's inevitably harder when a whole series of value judgements are at stake, and however hard HR departments might try, cases can't be reduced to box-ticking.

In the case of Arts and Humanities academics (and it may be different in the sciences), even if we stick to research alone, the issues are infinitely tricky. It's partly a question of how we evaluate a 20 page article, by a lone scholar beavering away in the library -- one that really changes the whole area that it is discussing -- vs a big, million pound research grant financed project, that produces a couple of extremely long, very useful, but un-ground changing tomes. I know which side I am prone to come down on, but I also know that others differ.

But even less easy to figure is what work is going to prove to last the longest. It's all very well making an apparently ground breaking splash today; but what do we think if in 20 years time it has all proved to be a dead end, a wrong turning, or quite forgotten. I remember talking at a conference in Cambridge a few years back and asking a pretty senior humanities audience (most of them loaded with hon. degrees etc) to reflect on whose work they thought woud last. It was clear from the looks on most of the men's faces that they had never really considered that it might not the theirs. But a trip to the old shelves of many a library will reveal plenty of once fashionable contributions now more or less on the dusta cart (or, to be more charitable, awaiting rediscovery).

As for the teaching and administration, I am right behind the signatories of the letter. It is mad to suggest that teaching the next generation to change their minds about things is NOT in some senses the equivalent of research.(One of my proudest moments was when, after a supervision, a guy popped his head back around the door and said "I've never thought about things in that way before.")

And certainly, in any place I have worked, everyone on the "shop floor" has known who really pulled their weight in administration (that's making the whole show work) and who didn't. And it's that "on the ground" knowledge that we have to find a way of tapping. The truth is that, in my time (and I'm talking 35 years not only in Cambridge), I've seen quite a lot of attempts to "pull the wool" in this area on cvs. It's easy to get a great administrative record on paper if you choose your committees carefully. Some people have a great knack of chairing working parties that never meet, of acquiring impressive looking administrative sinecures, etc -- while others are slaving away, unsung, and often fixing the damage wreaked by the lazy.

But lets hope that getting these issues into the open will make an impact; because there is no doubt that in some parts of academe the ladies are still, promotionally, lagging behind.

Mary Beard's Blog

- Mary Beard's profile

- 4071 followers