Mary Beard's Blog, page 35

April 26, 2014

Double take on Augustus: at the Grand Palais

Last summer I posted briefly about the big "Augustus" exhibition in Rome, and I reviewed it in the TLS. More or less the same show has now transferred to the Grand Palais in Paris, under the title "Moi Auguste".

It's only occasionally that I get to see the same exhibition in two different places. In this case it makes an interesting comparison -- and, good as the French version is (simply for the collection of stuff conveniently in one place), as a show it doesn't honestly come up to the original in Rome.

To be fair, there are a few impressive, wow-factor, moments. In the Grand Palais, you go straight in to face the Prima Porta Augustus (which does look amazing, although it wasnt quite as easy to get round the back of the piece in Paris as it had been in the earlier version of the show). In Rome, it had only travelled from just up the road in the Vatican, so probably wasn't thought unexpected enough to be the introductory moment.

But generally, the changes made in France haven't really helped, and there are some very odd (not to say occasionally disastrous) design decisions.

This starts very near the beginning, in just the second room. There is a brief line up of imperial/pre-imperial heads, each one aaccompanied by a coin portrait for comparison. Because of the potentially nickable coin, it appears, each of these portraits was covered by a large, not every elegant, perspex  box. Maybe that wasn't so bad. But they didnt actually have a marble bust of Antony, so they chose to have a large perspex box with just two coins and a gap where the marble head might have been.

box. Maybe that wasn't so bad. But they didnt actually have a marble bust of Antony, so they chose to have a large perspex box with just two coins and a gap where the marble head might have been.

Things got worse on the second floor, where the exhibition lost the tight focus it had in Rome and became more of an illustrated gude to the Roman empire, Roman everyday life  (with an accent on France). Some of the best pieces were dreadfully lit. (The husband poignantly observed that he had never seen the stunning bronze Augustus usually in Athens looking worse (left), and the Meroe head from the British Museum (above) presided over a pool of gloom.)

(with an accent on France). Some of the best pieces were dreadfully lit. (The husband poignantly observed that he had never seen the stunning bronze Augustus usually in Athens looking worse (left), and the Meroe head from the British Museum (above) presided over a pool of gloom.)

There were few cases where you could see both sides of an object. One of the few of these was  occupied by a rather undistinguishe; see rightd collection of glass ware (where nothing was gained by having the all-round view). The amazing Hoby silver cups (below),

occupied by a rather undistinguishe; see rightd collection of glass ware (where nothing was gained by having the all-round view). The amazing Hoby silver cups (below),  where it really is worth having the 360 degree angle, were stuck with their "backs" to the wall of a case -- painted a very ill-chosen shade of white).

where it really is worth having the 360 degree angle, were stuck with their "backs" to the wall of a case -- painted a very ill-chosen shade of white).

Sadly the star of the show on the second floor ('star' in the sense of what grabbed to attention of most visitors, were some projected images of the paintings of Livia's garden room at Prima Porta and assorted other high spots of Roman  painting (sadly my picture on the right -- though it shows the three clunky projectors, doesn't capture the fact that these "paintings" moved, and bits of them got magnified, then shrunk again). Needless to say, these hadn't been in Rome; and we couldn't help thinking "why waste money on this, rather than light the Meroe head properly, or show the back of the Hoby cups?".

painting (sadly my picture on the right -- though it shows the three clunky projectors, doesn't capture the fact that these "paintings" moved, and bits of them got magnified, then shrunk again). Needless to say, these hadn't been in Rome; and we couldn't help thinking "why waste money on this, rather than light the Meroe head properly, or show the back of the Hoby cups?".

Dont let these criticisms put you off visiting though -- just to see what there is. In fact, I'm going with some students next Saturday, and I think they'll get a lot out of it (plus, I'm afraid, being quizzed by MB on the museological deficiencies).

If you do go, there's a nice Italian restaurant nearby, Artcurial, with a ¢25 formule and some very nice N Italian wines -- who were very friendly when I emailed and said that we would like to book lunch at 3.00 pm. Try to come a bit earlier, they said, but if not -- we'll wait. Not a response I received from the other restos in the neighbourhood.

April 24, 2014

Problems?

Just to say that currently I am not seeing any "comments" at all. They get to me, I publish them -- but they then don't appear on the blog. I am investigating. Meanwhile, I'm publishing this little notice as a main post! Mary

April 22, 2014

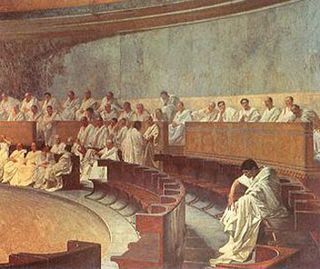

Catiline -- redivivus

It is the beginning of the Cambridge term (officially starting today) -- but there is a funny lull between the students returning, doing their first piece of work, and things really getting going for ME. I'm having the Newnham first and second years around on Sunday night (and we are going to have a drink or two and watch a Roman tv programme -- not mine -- and talk about the point etc). I am looking forward on Thursday to re-meeting one of my excellent Berkeley graduates (from back when I was doing the Sathers), who is passing through Cambridge. And on Friday Lin Foxhall is coming from Leicester to give the Jane Harrison lecture at college (on the public face of archaeology). Plus dinner (no free port!).

Meanwhile I am getting the first chapter of the new book in my head.

I am starting with Catiline in 63 BC (before going back to Romulus). That's partly because we know such a lot about his so-called "conspiracy", from contemporary accounts and later (it doesnt make it simple to unpick, but there is a richness there which I think will grip people to the cutting edge of Roman history).

But I am also interested in the long literary history of Catline's up-rising, and the different ways it has been appropriated in modern political history. That goes from Ibsen's radical democratic freedom-fighter to Ben Jonson's ambivalent Guy Fawkes look-alike -- or Dante's villain.

It's striking that the phrase -- "Quousque tandem.." -- that Cicero used at the very beginning of his first attack on Catiline (as it is "published" in the First Catilinarian) has had such a long life. It gets quoted and requoted in the ancient world (Sallust in his essay on the conspiracy neatly puts it into the mouth of Catiline himself, and Livy conscripts it to add colour to an early Republican conspiracy). But it survives as a political (and cutural) slogan right up to the present day. If anyone knows anything more recent than Hungarian protests a few years ago, I'd love to know.

So it seems a good incident and text to dwell on, when launching thoughts about the continuing resonance of Roman history. Hope it works.

Sorry by the way: Typepad has been a bit iffy these last few days; hope you have got on the blog.

April 19, 2014

Oxford Today -- online

Earlier this week three copies of Oxford Today (the Oxford alum magazine) came through the letter box, one each for the husband, daughter and son who have degrees, of different kinds at different levels, from the University of Oxford (cue, I fear, for outrage about elitist closed 'university shop' -- and I apologise and say 'fair cop', and I will discuss this on another occasion).

My first thought was about the waste of money, energy and paper sending three copies of this magazine to three people with the same surname at the same address. I am sure there is somewhere a bit of small print that suggests you 'unsubscribe' in these circumstances, but my family have never spotted it.

That said, I do rather prefer Oxford Today to Cam (the Cambridge equivalent) -- partly because it tells me things I didn't already know.

So I much enjoyed the Ruby Wax interview they printed, and I hadn't spotted before that Stephen Fry was going to be giving lectures about Contemporary Theatre.. and there was the neat little notice about Martin West getting an OM.

But there was also a long article on how up to the minute Oxford now is. It featured a no doubt innocent undergraduate reading English, and her day to day online life. She finds an out of print book via "m.ox.ac.uk (rather than "scouring the card catalogues"), and the app. gives her a map to show her how to get to the library concerned (presumably it was the Bodleian, and hardly rocket science to think that, as a copyright library, it might hold that out of print book??).

She then picks up her last assignment from her "virtual pigeon hole" and was pleased to see "that the automatic plagiarism report gave her full marks for her use of source citation", But before she could think about that, she had had a twitter message from @OxfordExams to say her exam results were ready to collect online.. while her tutor had sent her a party invitation on Facebook (oh, and dont lets forget the Facebook revision group chatroom that has been so helpful).

Now I am not saying this is a bad thing (and I am as addicted to social media as much as the average 18 year old). But crikey.. I couldn't help thinking that an evening face to face down the local pub might have been better than a Facebook revision group, and that maybe a nce little invitation in her REAL pigeon hole might have been an even better invitation to a party.

And I also couldnt help thinking why a university as computer literate as Osford claims to be could work out that it was sending three copies of its alum magazine to three people with the same surname at the same address.

April 16, 2014

A revision course in Livy

I think I have already said that my next book (the one that I am working on nowm not the one just about to appear) is a History of Rome -- from Romulus to Caracalla (reasons for end point will be revealed in due course). It is primarily meant for a general intelligent audience, and the register I am trying to hit is the one I struck in Pompeii. That is to say: I'm not assuming that the reader knows a lot about ancient Rome, certainly not the technicalities, but I am not assuming that they are stupid either or that they want to be given a "baby version" with the problems and big questions skated over.

The point about Roman history (as with the archaeology of Pompeii) is that "how we know what we know" can be almost as interesting (sometimes as interesting) as what we know. On the other hand, readers dont want a book which adds up to little more than a series of laments about how inadequate the evidence is (you cant believe Livy, the archaeology is misleading, etc etc, over and over again). The knack seems to me (and I hope I have got it) to find the right questions to ask of the material we do have, There is a hell of a lot of surviving evidence for ancient Rome. It is only inadequate if you ask it the wrong question.

Take the stories of Rome's foundation, Romulus and Remus inter alia.

There is very little benefit at all in trying to work out which bits of the ancient narratve history of the earliest phases of Rome might reflect historical reality. All those that survive were written well over half a millennium after the supposed events concerned, drawing on lost sources written about half a millennium. It is absolutely clear that some of the story is fantasy/myth (the suckling of the babies by the wolf, for example; some Romans themselves saw that couldnt be factually accurate and pointed out that lupa meant both wolf and prostitute -- the twins had actually been found by a prostitute). It is also quite likely that there are a few traces in the accounts of some aspects that may go back, albeit indirectly, to the very earliest period. The trouble is that we dont have any reliable criteria at all for sorting the wheat from the chaff. Most historians simply cherry pick the "facts" that suit their argument.

On the other hand, if you read the extensive foundation stories that we have (Livy's first book, 4 books of Dionysius of Halicarnassus etc ), you get a wonderfully rich view of how Rome had come to see itself, and debate its own position by the first century BC. The very "fact" that Romulus killed Remus seemed to write fratricide and civil war into Roman identity from the start (continued according to the "myth" by the idea that Romulus' death was not necessarily natural, nor some form of apotheosis; some said he was hacked to death by the senators). And the notion that Romulus first acquired a population for his new city by declaring an asylum, and inviting the runaways and criminals from Italy to join his settlement, chimes loudly with Rome's historical approach to migration and the extension of citizenship.

But the foundation stories (which are almost always retrospective creations anyway, in any culture) are the easy bit. I am now trying to get to feel a bit more comfortable with the "history" of the early Republic, and its rather ambivalent heroes (Camillus and Cincinnatus and co). It's not a period that I have taught for years and years. So I am sitting down with my Livy and reading it quite carefully (flitting a bit between the Latin and the translation I confess).

Going back to it after so long (and reading at a bit of a pace) , I must say that Livy seems sharper and wittier than I recall. Over the last few years, I have got rather stuck in all the cruces and puzzles (like on the impenetrable discussion on the origin of Roman theatrical performance in Book 7), to the exclusion of all else.

My favourite bit so far? It's when he writes (also in Book 7 I think) "I expect readers might have got a bit bored by now with all these wars against the Volsci"! Well, yes and no.

April 13, 2014

Political families?

After the last Olympics I wrote a post about family traditions in sport -- quickly counting up how many of our medal winners had parents in the athletics/cycling/rowing business. I now discover that the House of Commons do the same exercise for MPs, much more efficiently, checking out their family histories. There was one survey in 2008 and another earlier this year. The first one covers just one generational links, plus husbands and wives. The most recent one (though excluding "in-laws") goes four generations back -- from which we discover that David Cameron is the great grandson of Sir William Mount (Con. Newbury 1900-1906, 1910-1922), that William Cash is the great grandson of the cousin of John Bright (Lib. Durham 1843-1847, Manchester 1847-1857, Birmingham 1857-1889), or that Harriet Harman is the great great niece of Joseph Chamberlain (Lib etc, Birmingham 1876-1885, Birmingham West 1885-1914).

If you just stick to sons and daughters, the figures are pretty much identical in 2008 and 2014. Counting one stepson, there were 21 MPS who were the children of MPs in 2014, and 20 in 2008. They were pretty well balanced between Tory and Labour in 2008, tilted towards Tory in 2014 (14 plus 1 DUP, as against 6 Labour). There were four daughters in 2008, just 2 in 2014.

And there's no sign of the pattern changing, with Blair, Kinnock and Straw junior all said to be seeking parliamentary seats -- and there's no doubt more. And the USA, of course, have the families Bush and Clinton.

The more distant relatives intensify the picture. If you add in the grandchildren and great nephews/nieces etc, you get to 39 close relations in the House of Commons succession in 2014 -- or over 6%.

How come? And do we mind?

Well, I dont think we should mind about the husbands and wives -- who are also included in the calculations. Presumably people with similar political interests tend to get it together.

But I feel a bit torn about the succession rate of children and grandchildren. On the one hand, you can see a serious argument which says that there is a privileged political class in operation here -- a de facto aristocracy of political power. Take someone like Hilary Benn: son, grandson and great grandson (twice) of MPs. It does look much like a political silver spoon.

On the other hand, it may be much less sinister, and an almost inevitable spin off of family life. Just like those sports kids probably came home and got a real pat on the back for coming first in the sprint, so these political juniors probably got much more parental attention by chipping in with a clever remark about the budget than they did by achieving a record discus throw. Perhaps, in other words, it's all a bit more innocent.

And on reflection, it's probably not all that different in the Academy either. The Toynbees and the Darwins are academic dynasties on the scale of the Benns. And there are plenty of classical children in my particular neck of the woods -- Dorothy Thompson the daughter of Frank Walbank, Mark Griffith in Berkeley the son of ancient historian Guy Griffith, and there's no doubt plenty more.

And if I'm honest, when my kids came home from school, I was probably better pleased if they had got an A for a project, than if they had won the running cup. I would have tried to conceal it, but they would have noticed.

And what are they doing now? PhDs!

April 9, 2014

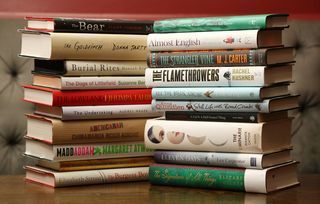

The women's fiction prize -- and Baileys

A couple of nights ago the short list for the Baileys Women's prize for Fiction was announced: a galaxy of six recent novels, that I have had a hand in choosing.

First point (ok let's be honest): it was a great party, with loads of great women, and men, letting their hair down at the Serpentine Gallery.

Second: we were celebrating a wonderful selection of books. You can see the shortlist here.

So what was it like being a judge?

For a start, it was damn hard work. It wasn't the case that every submitted novel was read by every judge; but each one was read by at least two of us at the first, pre-longlist, round (and after that we all read everything). So that was forty or so books for each of us, and 150 something for the chair. But for me it was a wonderful alibi. I spend most of my life reading non-fiction, but the pleasure of saying to all around me that I was bedding down on a Sunday with some fiction (and this was serious, and could count as work) was truly wonderful.

I don't think it's giving away any secrets to say that it was a really tough call to arrive at a shortlist, and it will be an even tougher call to find a winner (we dont decide that till just before the announcement, so there are none of those awkward days when the winning title might leak out). But for me -- hard work and alibis apart -- the process has been a tremendous privilege.

Privilege? Well, there were those marvellous afternoons spent talking about the books with the other judges (I've never actually been a member of a book group, at least not for fiction; but this felt to me like a really great book group.... swapping ideas and arguments, likes and dislikes, literary judgements etc). But, more broadly, the glimpse of English language fiction -- date line 2013 -- that I felt I got was indeed something to die for. In fact, I've come out of the process so far with a sense of knowing what is going on in the contemporary world of novel writing (I fear I might be a bit over-confident about that sense and it will no doubt disappear soon; but all the same it's very good to have it at this minute).

But a few questions. First, when the short list was announced, people pretty soon asked how come there were no British authors on it. Was this a sign that British fiction was in a state of decline? Answer. I dont think so. It was a real tough call getting the long list whittled down to a short list, and there had been a number of UK writers on the longlist. Besides, I dont think one should make too much of a single year. There were I think three British authors out of the six shortlisted last year.

Second, why a prize specially for women's writing? When many of the general prizewinning novelists are women (think Hilary Mantel), why a prize that puts the "girls" in a special category? There are lots of answers to that one. But mine is simple. There is still a job to be done for women's writing -- which is not finished simply because of the well deserved success of a few female novelists. As people are now increasingly pointing out literary attention (in terms of reviewing and being reviewed) is still weighted towards male authors. The Women's Fiction Prize is a great way of turning the spotlight on women's writing in English right across the globe.

But what about Baileys the new sponsor of the prize (pictured there at the top)? Here I have a confession. I had never tasted the stuff, and thought it would never ever be my kind of drink, even if I had to sip a little politely in the course of judging the prize. The truth is that at the shortlisting party I ventured to try a Baileys chocolate version with ice. And a great drink it was too.. both glasses of it. So I guess another plus point to being a judge is that I've found a new tipple!

April 6, 2014

The apology problem

Apologies are always difficult. There's always a fine path between the Scylla and Charybdis of saying too little and saying too much (do we really need to know...?. Then there's the question of whether you seem sincere or just mouthing it. There's hundreds of times we've heard people say "I am very sorry if I upset you over this" (carefully not, "I am very sorry to have done this"): good enough or not?

In a way, too much scrutiny of the words is perhaps beside the point. Apologies are rituals, they are a very simple case of "doing things with words". The only thing that actually counts is the audible expression of "I'm sorry" (like "I do" at a wedding). Or are we expecting people to SHOW contrition? And how do we recognise it, in any case. Some people can seem dead truculent and controlled but actually be eaten up inside -- and vice versa.

That is in a way Maria Miller's problem. My guess is that the party spin doctors instructed her to be as brief as possible, on the basis of "give the press any rope and they'll hang you with it", and I might have advised that too if I'd been a spin doctor; wrong call as it turns out. Not that prolixity (so far as I have been able to discover) is the trademark of House of Commons apologies. Nadine Dorries was no longer (even shorter) than Maria Miller, and David Laws a bit longer, but certainly not essay-length (it's the second, shorter one here).

But there are worse sides to public apologies and they can lead in dangerous directions.

I particularly dislike the governmental kind which fulsomely apologise for some dreadful wrong of the past (like slavery or our treatment of the Maori -- or, in the case of the Pope, the death of Galileo). It's not that those things are not terrible wrongs, but a government apology seems too easy a way out. It has all the appearance of a "that's OK then" line being drawn under the issue, and a pretty low cost one too. (Rather like "First Capital Connect apologises for the late running of this train and any inconvenience caused".)

When it's not a simple line being drawn, it can lead to some difficult follow-ups. In the case of Alan Turing, it was followed by a royal pardon for his conviction for gross indecency. Of course, noone would now think that he should have been convicted; so a good case for a pardon, in a way (symbolic as it is, as he's not here to enjoy it). But what about all the other people who were equally wrongly convicted on the same charge, and whose lives were no less ruined by it? Don't they get a pardon too? Not, it seems.

Another case where we think we can rewrite history with the flourish of a pen -- when we should be doing our best to do better than history (in whatever our new injustices may be).

So Maria Miller's apology is part of a more complicated set of issues on that particular score. As for the rest of her case, the husband has been doing his citizenly duty by starting to read the more than 100 pages of the Committee on Standards report on the case, and I have had a peek. Far too soon to say what we think -- except to know already that anyone who pontificates about the rights and wrongs of this particular case, as many seem to be prepared to do, without reading this detailed report are talking through their hats. (Whether we feel, in general, that there is a glaring and unjust disparity between "benefits" for the rich and "benefits" for the poor -- and I do feel that, pretty strongly -- is another matter.)

A very brief glimpse of the complexity, for those without several hours to spare, can be found in this joint statement from the Chair of the Standards Committee and the Commissioner, reacting to some of the press reports.

April 3, 2014

Cemetery reflections at St Symphorien

Yesterday I made a flying visit to the First World War cemetery at St Symphorien, near Mons in Belgium. I've had a bit of experience with war graves, particularly in Crete. When we went there on holiday when the kids were young, we used quite often to visit both the allied and the German cemeteries.

There were some good and wholesome family activites to be had. I remember getting the kids to find the graves of the archaeologists, or the different commonwealth nationalities, at Suda Bay, and making them reflect on the different aesthetic styles of commemoration -- and of course on the sheer scale of the human slaughter on both sides which the rows of headstones brought out better than any figure in a book. And the truth is that these cemeteries were always beautifully cool and watered when it was very hot in the Cretan summer. It was impossible not to admire what the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, and their German equivalent the VDK, did to make these places so beautiful and so affecting... and so wonderfully un-jingoistic. There was no lack of welcome, I remember, for a family of Brits at the German graves.

That said, I am of course far to old to have done what seems to be now the regular school visit to the battlefields and cemeteries of Flanders (though both my kids did .. coming back rather moved by Thiepval and frankly thrilled-and-scared by all the tales of unexploded ordnance still lying around the Flanders fields. So it was great to get a chance to have a good visit to one of the WW1 cemeteries in Belgium. I have, you see, just joined the Government's First World War Centenary Commemoration Advisory Group,

and St Symphorien is where one of the commemorative events will be held this summer. This visit was by way of a reccy for that event.

It is an extraordinarily beautiful place -- and very special because it holds roughly equal numbers of casualties on both sides. In fact it was originally established by the Germans for the British and Commonwealth soldiers, as well as their own (that's a German headstone on the left), who died at the battle of Mons in the first year of the war.

It is an extraordinarily beautiful place -- and very special because it holds roughly equal numbers of casualties on both sides. In fact it was originally established by the Germans for the British and Commonwealth soldiers, as well as their own (that's a German headstone on the left), who died at the battle of Mons in the first year of the war.

It's quite hard to capture the site if you've not been there, because it is arranged in small areas (for different nationalities, even different regiments) and surrounded by trees. The land was given by a local landowner (keen on horticulture -- hence in part the expert landscaping), and his donation is still commemorated, in the neutral language of Latin, close to the entrance (above); and it's now beautifully tended by the War Graves Commission, and their local staff.

Apart from the loveliness of the place, it makes a particularly appropriate spot for a commemoration, because it has the graves (just a few yards from one another) of the first British soldier -- Private John Parr  -- to die in action and probably the last one to die before the armistice (not the last to die in the war itself; there were plenty of deaths after the armistice of course).

-- to die in action and probably the last one to die before the armistice (not the last to die in the war itself; there were plenty of deaths after the armistice of course).

Like all such places it's an extraordinary stimulus to reflections, doubts, conumdrums and questions. You look at the words at the bottom of the headstone, that the families of the soldiers were allowed to choose themselves, and you cant help wonder what lay behind their choice. One just says "kismet" ("fate") -- one has the famous phrase "dulce et decorum est.." (now so mired in irony, but was it then for those choosing their commemorative lines?)

These things, of course, raise the issue of the fading individuality of these men. There is noone alive now who could possibly actually remember any one of them personally (well ok, to be strictly accurate... if they were 107 or so, maybe they could, but I dont think it's likely ). There is an inevitable tendency to think of them all together as "the brave and tragic fallen". But as those brief personal mottoes hint, one of the terrible over-simplifications of history is to merge them into a single category like that. Some would have been brave.. but some wouldn't. Some would have thought they were fighting a valiant fight. Some would have been not so sure. Some would have been good men and true, but petty criminals and drunks fell too (and yes, of course, we want to remember them, but does that retrospective sanctification come at a cost?)

And then there is the fact that they are all men. I found myself conflicted on this one too. Part of me was asking, in a pretty obvious way, where are the women? Where are the nurses and those slaving on the home front? Some of them died too, if not in ways so obvious to commemorate. (Actually I'd taken Deborah Thom's excellent Nice Girls and Rude Girls: women workers in World war 1 to read on the train, so I'd already been thinking about this). But another part of me felt a bit uneasy about that slightly knee-jerk reaction. What the cemetery so vividly (and poignantly) demonstrated was that these victims were young men. Maybe, I wondered on the way home, we have take head on the fact that is was a generation of men, not women, who were nearly wiped out.

To be honest, I just dont know. But I think that the commemorations coming up this summer and over the next four years will do their job very well if they give us all some space to have such doubts and questions.

March 28, 2014

The curator's egg

Museum and gallery curating seems just to have become sexy (again). That's partly thanks to the appearance of Hans-Ulrich Obrist's book, Ways of Curating (a riff on John Berger's Ways of Seeing, I assume). Obrist is co-director of the Serpentine Galleries and is interviewed here on curating history and ideology.

Quite why people like Obrist have to resort to Latin etymologies, heaven only knows. ("It comes from the Latin word curare, meaning to take care. In Roman times, it meant to take care of the bath houses" he says in the interview. What on earth does it have to do with "bath houses"??). But -- that apart -- I'm looking forward to getting my hands on the book, which (from what I'm told -- not seen it yet) explores all kinds of aspects of the art of gallery curation, and the different experimental forms it can take.

But it's just not Obrist. Curation seems to be the flavour of the month in Cambridge Museums too, with an on-going project on the "art and science of curation" -- including contributions from museum professionals and visitors too.

There's going to be a five week season of "curating events" later in the year. But there's a prequel already on this website. It hosts a variety of comments from members of the public on what they think "curating IS..." ("Curating is" ...."fun", "critical and controversial", "a vexed question" and so on. I particularly liked the one which said "How would you respond to the question, "Can I talk to your curator'?"). And there are also blogs from the curators themselves, including a nice mini-autobiography in curating by the new Director of the Fitzwilliam, Tim Knox.

It all took me back 20 odd years to 1991/92 and a little exhibition in the Ashmolean in Oxford that I co-organised with one of my colleagues, called the "Curator's Egg" (OK, feeble pun).

We were, I have to say, very lucky to be allowed to do this (neither of us could lay claim to any actual hands-on museum experience). The fact was that we had exploded at a seminar to Michael Vickers then curator of Greek and Roman at the museum -- about the conventions of curating, the silences of the display (why never say how much something cost?), the rebarbative conventions of the museum label (all those abbreviations that mean nothing to most visitors), and the blind eyes that curating tends to turn (when do we learn that most of the ancient artefacts of Greece and Rome on display were produced by slaves?).

Michael's response was brave." OK," he said, "if you think we have got it so wrong, then you can have one of our little exhibition spaces to show us how you think it should be done." We could hardly say no.

We crammed the little room in the Ashmolean with crazy labels and spoof information panels ("Please dont touch the ceiling", "SHHHHHHH!", "This is a product of slavery", "What aren't they showing you?" ... and a variety of price tags tied onto the objects). We piled up fragments of pottery in a big random heap, we treated a broken off statue head as if it really was a decapitation victim, and we introduced into the precious originals a plastic "garden-centre" Venus.

As museology, it was probably a bit mad (and there were rather too many juvenile jokes in a small space). But it did score a few good hits. One critic recently (and generously) wrote about how the show worked by "making visible questions of curatorial etiquette and decision making, challenging the devices that inscribe the visitor into the museum experience . . . and disturbing the prescribed routine of silent contemplation, non-tactile interaction and one-way routing." Which is exactly what we were trying to do!

I still have that plastic Venus in my college room -- and I have a feeling that Obrist himself might have quite liked the show.

Mary Beard's Blog

- Mary Beard's profile

- 4110 followers