Mary Beard's Blog, page 21

September 2, 2015

More churchyard creeping -- and a great place to visit in Rome

I am working out of the country at the moment, and this morning had a few hours off in Rome. It wasnt exactly 'off' because it meant another little bit of delving into my Roman epitaphs' project.

That is to say I was paying my first visit for about twenty years to the non-Catholic cemetery (popularly known as the "Protestant Cemetery", but there's way more than Protestants in the ground there, hence the proper title). I was primarily looking for nineteeth-century replicas of the third-century BCE sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus, and there was a rich haul of those --as you can see from just this one (out of 9 or possibly, with the wind behind you, 10).

And this 'fashion' is one of the things that I am hoping to look at in my lectures in Bard in a few weeks. But that aside, the cemetery is a wondeful place, exactly where I would want to be buried -- after the rather more convenient St Giles' churchyard opposite my house.

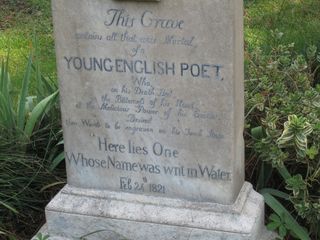

The most famous burial is probably that of John Keats (above), though he probably vies in fame with Antonio Gramsci. But what is wonderful about it are the visual links with the vast pyramid tomb of a junior member of the ancient Roman aristocracy just next door: 'the pyramid of Cestius'.

But there is a wonderful glimpse of the range of people, especially (but not only) in the nineteenth century, who died --as non-Catholics --in Rome. There's Shelley and the young Goethe, as well as Karl Bruilov (who painted the vast 'Last Day of Pompeii') and the sculptor John Gibson (he of the 'tinted Venus'). And it is wonderfully kept up by a maintenance team, busy at work while I was there, and volunteers and a band of money raisers.

I often suggest that when people go to Rome they visit the Centrale Montemartini museum. This is about 20 minutes walk away. They make a great pair, and the cemetery is well worth supporting.

August 29, 2015

The theatre at Palmyra

I exploded on Twitter, earlier in the week, as much as 140 characters will allow you to explode. It was after the nth report that I had heard, or read, discussing ISIS atrocities in the 'amphitheatre' at Palmyra. I admit that I have not been there, but so far as I know Palmyra has no amphitheatre. What it does have is a rather splendid theatre (above, photo Reuters).

The different is simple. In an amphitheatre the seat go all the way round in an oval (that's what the word basically means: amphitheatre). Here's the one at Arles:

In a theatre, the seats are in a semi circle, or sometimes a bit more than 'semi' and there is a stage at one end, as in the picture above.

The amphitheatre was a distinctively Italic/Roman invention; the theatre was found in both the Roman and Greek world.

So why get so cross about an innocent, if repeated, confusion? Why be a pedant?

It's a simple answer really. If we, in the west, want to protect our cultural heritage in the face of the forces of darkness, then we might at least get the details of that cultural heritage right. And that is especially so when we are mourning the death of an archaeologist for whom that sort of distinction was very important.

There is also a question of the easy and nasty associations of "amphitheatre" which seem to fit the bill all too well here. The truth is that the function of both theatres and amphitheatres was more varied than is often said. Amphitheatres must surely have been used for more peacable activities when gladiators etc were not on display (markets, for example, and other forms of popular entertainment). And theatres for dramatic performance could double as public meeting places, as well as being adapted (with speical bars and fittings for nets) for wild beast hunts. But the basic function of an amphitheatre, unlike the theatre, was always gory.

That is why it seems so seductively appropriate to imagine ISIS atrocities happening there. But it's a wrong analogy.

August 27, 2015

Remembering Sheila Browne

I always feel awkward about my reactions when I find myself grieving for the death of someone I have never met (yes I cried at Di���s funeral, but why exactly is a complicated question) or even of someone I haven���t seen for decades and exchange at best a desultory Christmas card.

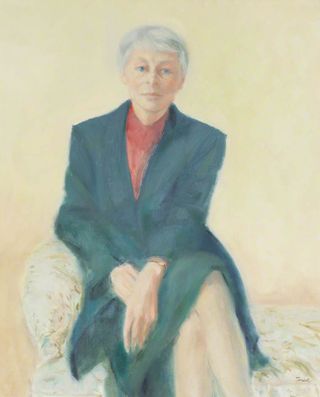

Yet I did feel sad today to learn the Sheila Browne, who was once Principal of my college had died at a ripe old age. I hadn���t seen her for many years although she did occasionally get in touch to tell me what she thought of what I had just written (often favourable, but always frank). But she was imprinted in my memory as the Principal of Newnham when I returned there as a fellow in 1984 and made one of those defining transitions into a new style of adulthood (and I don���t need any clever sod to tell me that my grieving is really for myself and my past..).

She also introduced me to some of the ambivalences of academic character from close up.

As I recall, Sheila had been at Oxford, then briefly an academic, before becoming in the days before Ofsted an HMI, and later Her Maj���s Chief Inspector of Schools. I discovered after my Mum died, as I went through her papers, that Sheila had visited her school and had been gratifyingly complimentary about it. But for me in the early 80s her claim to fame was having stood up to Margaret Thatcher on some educational issue that I now dont fully remember but seemed hugely important at the time.

In public Sheila could be terrifying. She always complained that at meetings the younger fellows would never speak up. She didn���t seem to realise that if, when they did, her response was to say something along the lines of ���I���m sorry, you���re wrong���, it wasn���t a great "come-on" to open your mouth. But if you did persist, as I and some other trouble makers did, you got rewarded with dinner and generous quantities of the alcohol she didn���t touch.

Her dietary habits were in general austere. At big dinners the chef would present for pud some elaborate, over-the-top meringue creation, which came in the Principal���s job description, I then imagined, to consume; Sheila would push it away and demand a Coxs Orange Pippin. She was before her time, perhaps, as I now think, in refusing to 'eat for the college'.

In private, she was quite different. She did have a tendency to see the blacker side of life (I longed for the day when Sheila would have watched a telly programme that she actually liked...). But anyone who needed help could -- clich�� as it must sound -- always count on her. She would beetle up to the hospital with almost anyone in college who needed a trip to A and E. And she gave me some of the best advice I ever had.

When I was pregnant with child number 1, I went to her to discuss the arrnagemets for my maternity leave. I was intending not to take all I was entitled to (with pay... never quite understood this concept of unpaid maternity leave), and to come back to coincide with a new term and so sacrificing a few weeks.

Sheila, childless and so far as we could tell (I get more anxious about saying that as I get older) unpartnered, simply said: "you take every week you can get... they give you four months , because that is what you need". And -- happily -- she gave me no choice.

Cheers to her.

August 23, 2015

Roman graves

The truth is that before I really get down to the Leverhulme project on images of emperors, I am doing a three lecture gig at Bard near New York for the Anthony Hecht Lectures; the subject is Roman Epitaphs. In some ways I guess it is an obvious theme. But that is why I chose it I suppose.

There are well over 180,000 epitaphs surviving from the Roman world, and they have been well studied from all kinds of angles (age at death, family relations etc..). And I hope I will touch on some of those angles in my lectures, but I am also interested in how people have been interested in these texts, grand and humble, in the centuries that have followed.

One of the things that has struck me is the impact, from the late eighteenth century on, of the Tomb of the Scipios, discovered just off the Appian Way. This tomb plays quite a big part in my book, partly because -- as Peter Wiseman has already pointed out --the epitaph of Scipio Barbatus (who died around 280 BCE) must count as the first surviving bit of Roman history writing to survive.

CORNELIVS��LVCIVS��SCIPIO��BARBATVS��GNAIVOD��PATRE PROGNATVS��FORTIS��VIR��SAPIENSQVE���QVOIVS��FORMA��VIRTVTEI��PARISVMA.FVIT���CONSOL CENSOR��AIDILIS��QVEI��FVIT��APVD��VOS���TAVRASIA��CISAVNA SAMNIO��CEPIT���SVBIGIT��OMNE��LOVCANA��OPSIDESQVE��ABDOVCIT

or

'Cornelius Lucius Scipio Barbatus, sprung from Gnaeus his father, a man strong and wise, whose appearance was a match for his virtue, who was consul, censor and aedile among you - He captured Taurasia, Cisauna, Samnium - he subdued all Lucania and led off hostages.'

I have had quite a lot to say about this in the book (I like the idea about Roman bigwigs looking the part: the 'appearance was a match for his virtue' line). But now I am interested in the whole early modern fame of the tomb. It was rediscovered in the late eighteenth century and there are an extraordinary array of tall stories about what happened to the bones of Scipio Barbatus among others.

What I had not realised until recently is how many modern graves copied the sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus, and how weirdly. The tomb from Highgate cemetry at the top of this post is that of the novelist, Mrs Henry Wood, the Victorian chick-lit novelist... so why on earth was she buried in a look alike copy of Scipio Barbatus' tomb?

August 21, 2015

Sorry . . .

. . . I know I said that I was not going to inflict more of the book on you. But the truth is that I haven't been doing anything else for the last few weeks, and not much else is in the head. It is a nice illustration of how 'finishing' a book is not quite the simple idea that it can seems, or how the goal posts constantly recede.

To start with, it seems that it is when you have put the (metaphorical) pen down on the last chapter, or maybe on the Acknowledgements . . . one of the nicest things to write actually (and you commenters get your fair mention, let me say). But that is only the very long beginning of the very long end. That's not just the copy-editing (and I have had a great editor) and the picture chasing (great help there too). But it's things like the caption-writing, the bibliography and the maps. You were all very keen on the maps, may I remind you.

So you will be pleased to know that SPQR has no fewer than five maps (don't say I don't listen). That's fine, and I think you will be really pleased with the result, but getting them into a usable shape, even with a really great cartographer (and he is), is easier said than done. Italy, for example is a naturally long and thin shape, and fits readily into the shape of a single page. But what happens when your beautiful peninsula looks gorgeous on its single page, but is just a bit too small to read all the names very clearly. Should you just cut off Sicily and the north (bye-bye Pliny's Comum and the lovely Patavium)? Or does that look too silly (especially when Corsica and Sardinia get half the chop too)? So do you decide to put the map over a double spread, which makes it bigger of course, but means that you have to put it horizontally, meaning an awkward swivel for the reader (and is actually rather TOO big anyway)?

Before you get too fixed on your solution, let me say that we decided to stick on a single page and cut as much as possible, without sacrificing Comum etc, and to slightly expand beyond the standard boundaries of a map on a single page (ie cut down the margins). I hope it meets with your approval. (At the same time, may I admit, I discovered when blowing up the plan of the Roman Forum that a hard to spot that a simple typo had crept into the 'Lacus Curtius', making it 'Lacua Curtius' (how many times had I seen it, and not spotted?).

Anyway, so pass many days. I have to say that I am extremely grateful to all the technical people who are putting this together (the designer was still taking on corrections at 7.30 tonight), and to all at Profile, the publishers, who operate in a reassuring combination of new fangled hi-tech and old-fashioned face to face. This may seem like nauseating sucking up, and I realise that over fifteen years with the same publishers has earned me privileges that others may not get.. but to spend today in their office, at the desk adjacent to the main editor (correcting errors together), within a shout of the in-house designer, and a few feet from the publicity director.. and sharing a drink at the the close of play... seemed to me to be how publishing should be. Thank you all.

August 16, 2015

Compliance by website

For various reasons, I was having a careful look yesterday at a secondary school's website and was surprised to discover that they had a whole section of their website devoted to the question of how they promoted British values. For those readers abroad, this clearly related to a government directive last year that all schools should do precisely that: promote Britishness. This apparently means the values of "democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty, and mutual respect and tolerance for those with different faiths and beliefs".

Now there are all kinds of obvious problems with this. For a start, it is hard to know what the government thought any teacher was supposed to do when confronted by the clever 13 year old who asked if the law-breaking suffragettes were promoting British values or not. And the idea that these values are peculiarly British causes one to gag a bit (one section of the government guidelines actually suggests that teachers should get across "the strengths, advantages and disadvantages of democracy, and how democracy and the law works in Britain, in contrast to other forms of government in other countries". Like what "other countries"? France?

But there are more problems than that.

My first reaction was to imagine that the school I was looking up had gone over the top in parading all this on the web. But a bit of googling proved me wrong. Almost every school in the country seems to have done the same. And not only that, but in more or less identical words.

"The importance of laws, whether they be those that govern the class, the school, or the country, are consistently reinforced at ...." runs almost all of them, before going on to add a local detail or two about home/school agreements or how "Circle time is used as an opportunity to discuss difficult situations that benefit from whole class discussion" and so on. And there was hardly a single one which didn't emphasise that "Visits from authorities such as the Police and Fire Service help reinforce these messages."

And there was much the same on democracy, with more identical phrases about schools councils and mock elections.

Now none of this is in itself a bad thing. And to start with I felt rather impressed with the way that head teacher after head teacher had ticked the government box by lifting a standard text (I never found the source) and shoving it on the website with the occasional idiosyncratic detail.

"Children in Sapphire Class are required to put together a manifesto which they present in assembly before the vote. School Council are involved in the recruitment of new staff." (This is a primary school, by the way, so I may be old fashioned but I hope that the seven year olds do not have TOO MUCH involvement in staff recruitment...?)

It was rather like what a now retired colleague used to say to us when some new directive came down to my Faculty from the central offices on some new policy: "just say what we do already, but put it in their words.." he would always advise. It's the easiest way of acceding without actually changing too much, or moving in directions you wouldn't want to go. And it has been similar with the REF: if you want to claim you do something, make sure it's on your website to "prove" it.

But on the other hand there was something terribly depressing in the idea that across the land in schools of all sort (against a background of the rhetoric of school autonomy), websites were being plastered with an off-the-peg statement of British values and how the school in question promoted them...

.. while presumably Police Forces and Fire Services have begun to operate a waiting list for all those schools that want a visit to show they are complying with the promotion of Britishness directive.

Is this really the way of talking about being human?

August 14, 2015

Bad lucks

It has, I fear, been a bad week. It started on Sunday night when I was away and having trouble getting the BBC on my laptop. In the hope of getting a better connection, I switched off and switched on again. Well I tried to switch on, because what came up on the screen was not the friendly apple, but a far from friendly question mark. Absolutely no way of getting in to my documents.

This was a nasty moment. I am not wholly efficient about backing up and though I knew I had most of the book in several places, I wasn't completely certain that I had backed up the Further Reading I was just finishing. It wasn't until about 2.30 in the morning that I could make certain via my iphone that it really was on Dropbox (I'd forgotten my Dropbox password).

There was still quite a lot, however, that would have been very inconvenient to lose and that I knew full well was not copied anywhere. So as soon as I got back to Cambridge I dashed round to our excellent Faculty Computer Officer to throw the laptop on his mercy. I have to say it did not look hopeful to start with, but 4 hours later, the hard disk had been taken out of my machine and copied onto another one. And I had been packed off with a loaned laptop attached to said disk, with nothing lost.

And the moral is . . .?? How often do I say that to my students... 'you mean you didn't have it backed up?'

It wasn't the end of my troubles, though.

On Wednesday I was taking all proofs -- a very large bundle -- to my publishers, and had the loaned laptop with me (now fully kitted out with my documents) in order to be able to check things against my original versions. So I was pretty loaded. About three minutes after I had got off the train at Kings Cross I realised that I didn't have the laptop with me. Apart from everything else, imagine going to tell the computer officer that I had left the machine he had kindly leant me on the train (isn't that what only civil servants in the MOD do?). So I ran back to the train, picking up a very kind man from the station staff on the way, and we just managed to get on and rescue the poor object about 30 seconds before the train was chuffing back to Cambridge.

And then things got worse. I had had a bit of a dicky knee while I had been away, but it had recovered with some low level tlc (hence I could run to rescue the laptop!). This morning I was leaving the house, walking up the garden steps on the way to London again when I wrenched it...in a rather painful way, as I later realised (not soon enough to realise that biking to the station wasn't really a good idea).

As the day has gone by, I have got slower and it has got more uncomfortable, at least when I put any weight on it. (For those of you who know Cambridge station, you'll understand why I wanted to weep when I realised on my return that we were getting into platform 8.)

So I'm writing this in bed, having done the ice pack treatment, and got the poor limb elevated on the pillows. And I'm wondering rather gloomily if this is what old age WILL be like, or if -- more realistically -- what it IS like.

August 9, 2015

The love of art

Somewhat prematurely perhaps I have moved on to the next book project, which is to write up my Mellon lectures on images of Roman emperors in post Roman art. There's quite a lot more primary research to do, so it's a very good job that I was lucky enough to get two years research leave from the generous Leverhulme Trust to collect just that. This means, I fear, that you will be hearing a lot more about small galleries and museums in charming (and not so charming) European locations.Because some of the most interesting relevant pieces are not well published and tucked away in rural France in particular.

One of them came up today in the excellent Mus��e Paul Val��ry at S��te. It was a tremendous nineteenth-century canvas by the wonderfully named Jean-Paul Raphael Sinibaldi, of the elevation of Claudius to the throne. Here's a detail.

It's a great encapsulation of a shocked middle-aged man pushed onto the throne by the Praetorians after the murder of Caligula (if you believe the story...reluctance being one of the best alibis for ambition then as now). But it was the painting at the top of this post that really caught my eye.

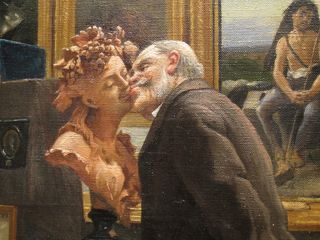

It's by Edouard Antoine Marsal (1887), entitled "Satyr and Bacchant" -- and what it shows is an elderly art 'lover' (the satyr) kissing a bust of a Bacchant, while a disapproving lady in the background notices what is going on. It is a scene from the Paris Salon of 1880, and is presumably meant to parody the many Satyr and Bacchant painting at the time, while also exposing the 'amateur' of art for what he is -- a lover. I liked the nice rhyme between the cane of the lover and the cane of the picture in the background, which was exhibited in the 1880 Salon and is also on show at S��te. It's the Prodigal Son.

In part I liked it because it fits into the grand tradition of erotic encounters with works of art, right back to the poor guy who tried to make love to the famous statue of Aphrodite at Knidos (the stain on the statue left a permanent trace of what he had been up to). But I also began to wonder if the 'satyr' was identifiable and if there was another story here. Anyone know?

August 6, 2015

Nuns in the hills

The main reason for our visit to Lebanon was for the husband to go and see a thirteenth century icon in the monastery of Greek Orthodox nuns in the hills outside Beirut at Kaftoun. I can't easily tell you how far outside Beirut it is, as we got lost so many times that distances became rather notional.

Sense of direction may have been a problem, but it really was hard to find, partly because it was, half intentionally no doubt, hidden under the cliffs.

When we arrived, there was not much sign of life, except for the sound of an electric saw. Sourcing the  sound, we found that the saw was being wielded by an admirably tough nun, who told us to go upstairs. And so we obediently went, but didn't find anyone there either. But as the men of the party took a lift down again (appropriately decorated with the icon we had come to see), the daughter and I (waiting to be the second party in the lift) were rescued by a nun, who whisked us off inside.

sound, we found that the saw was being wielded by an admirably tough nun, who told us to go upstairs. And so we obediently went, but didn't find anyone there either. But as the men of the party took a lift down again (appropriately decorated with the icon we had come to see), the daughter and I (waiting to be the second party in the lift) were rescued by a nun, who whisked us off inside.

This is where some decent Arabic would have helped. French was a bit of an asset, but not hugely.We were swiftly taken to the chapel where the icon was kept. And after a little while the men joined us, after some discussion about whether men were to be admitted or not. I have to say that after all those occasions in which Athos-style orthodox monasteries have been unwilling to admit the daughter and me, we felt secretly a bit pleased that the boot was on the other foot.

We spent a good 15 minutes 'doing' the icon (Virgin and Child on one side, Baptism on the other -- part of the Baptism at the top of the post), then off the buy the nuns' honey (pricey, but the cost of the entrance), before being allowed to spend a few minutes in their other chapel, with early wall paintings.

And then I confess it was on to lunch, and a quick trip around the ancient city of Byblos.

All this was made possible thanks to the husband's former PhD student, Rico Franses of the AUB, and his partner Nawal, who runs a great vintage clothes shop in Beirut, Depot-Vente --and I have come back with a great sparkly jacket!

And the food was stupendous. Extraordinary place.

August 2, 2015

Discovering a new star archaeological museum

For reasons I shall share in due course, I hitched a ride with the husband who was off to see an icon in Lebanon. I had never been there before, but had always wanted to see Baalbek. One should of course check ahead. It was only by the time that all had been booked that I discovered that Baalbek was very definitely now off limits, But it turned out that there was plenty more good stuff.

We arrived, as you can see, in the middle of a 'rubbish breakdown' (which was being very speedily cleared up by the time we left). This made the walk to the Archaeological Museum on the first morning rather smelly. But blimey, it was worth it. The whole place has been splendidly redone since the war, refitted with some of the best cases I have every seen (I loved the movable magnifying glasses attached to many of them) and has some fantastic things, from Egyptian prehistory on.

Poignantly the last case you pass includes some remnants of antiquities that melted when a shell landed nearby during the war -- though there were also moving tributes to Emir Maurice Chehab who as Director of Antiquities (and with the help of a lot of concrete) seem to have ensured that most things survived more or less unscathed.

For me the highlights included (1) a wonderful Roman sarcophagus that showed the dragging of the body of Hector behind the chariot of Achilles:

(2) a series of fifth-century BC votive babies (a bit cringe-making, but what does this say about images of childhood in antiquity?)

and 3) a couple of extraordinary architectural models -- one of a theatre and one of a temple. What on earth they were for. The labels suggested that they really were working guides for the builders. But they were surely very expensive for that, when some diagrams on a convenient bit of papyrus would surely have been sufficient.

Overall it was a very calm, cool, hopeful -- and actually very beautiful place.

Mary Beard's Blog

- Mary Beard's profile

- 4110 followers