Mary Beard's Blog, page 18

December 16, 2015

Thought for the Day

The other topic I had thought about before Question Time last week was the Butler Sloss report on the place of religion in modern British life. This was full of all kinds of extremely sensible recommendations, widely decried by the usual suspects. These went from the idea that their might be fewer C of E bishops in the House of Lords, and the numbers made up by a sprinkling of imams and rabbis, to some serious reservations over whether 'faith schools' were the direction we wanted to travel in 21st century Britain. I haven't managed to find the full version of the report online (if anyone does, could they post a link), but it doesn't seem to have gone so far as to recommend the disestablishment of the Church of England (or to suggest for that matter that we might have NO 'faith leaders in the House of Lords), but that would surely be the obvious next step.

There was only one thing where the traditionalist in this old agnostic growled a bit -- and that was in opening up Radio Four's "Thought for the Day" to the non-religious.

There is, I concede, something faintly ridiculous about the whole programme. And it is very wonderfully parodied on this site (go to the earliest entries; they are fuller than the more recent ones and hilarious). It doesn't take much to get into the spirit of the thing: "I much enjoyed the big match last night, and when that last almost-goal was stopped by ManU's heroic goalie, I am sure all our hearts were in our mouths . . .

December 12, 2015

The Question Time exam: bombing Syria and banning Trump?

I was a panellist on Question Time again last week. I've said before that it is the closest thing I now know to doing an exam (psyching yourself up, question spotting, revising). And in a funny way it seemed even more so this time. For a start, I added in the kind of bodily relaxation that we always recommend to students coming up to finals (in my case, getting my hair cut and a facial done at Gary Ingham), and secondly I kicked myself in all the ways you do after an exam about the prep I had done for questions that didn't actually come up.

So, for example, I had done my research on the whole question of at what age people should be allowed to vote (in the context of the recent disagreement between Commons and Lords on the voting age for the EU referendum). I could tell you that the minimum voting age on the Isle of Man (not a well-known hot bed of youthful revolution) is 16, and the same goes for Austria; whereas the minimum voting age for the Italian senate appears to be 25 (is that really true, can anyone confirm?). Meanwhile, you can't buy a firework until you are 18 years old. I wasn't exactly sure what I thought I would do about the particular issue in question, but I had got some reflections up my sleeve on the general problems about deciding when children become adults (and memo to self not to mention sex).

Anyway, all to waste, except for my own particular knowledge improvement. Not a whisper of a question on the subject.

Much the same went for the Tyson Fury debacle. We only got allowed a one word answer to the question: should he be struck off the BBC Sports Personality of the Year shortlist. My answer was no, but that we should vote against him. What I had wanted to say was that the BBC had already dug a pit for themselves by calling it a "personality" award, which implies that you should be a decent person(ality) in order to win, with no noxious views or penchant for illegal substances -- unlike, say, 'sports performer of the year". But more important I would have wanted to point out the oddity of our own reactions to Fury. Isn't there something a bit awkward about the idea that one week we are apparently happy about Fury being grilled by the police for sounding off like, as Alice Arnold put it, a "homophobic idiot" -- while two weeks earlier many of us were cheering him on for beating the living daylights out of another human being, in the name of sport. Maybe the problem is that we have come to think of successful sports people as role models, rather than just winners, by hook or crook.

Throughout the programme there was an underlying theme of banning people, as if the first line of attack/defence against someone whose views were anything from silly and misguided to vile and offensive. I agreed with Greg Clark that rather than banning Donald Trump from this country, we should argue with him when he gets here (no known plans, we have to admit), show him the error of his ways and subject him to some tough democratic debate, rather than let him just go on spouting ignorant rubbish (about London or Katie Hopkins). A bigger worry, if you ask me, was Trump's role as business ambassador for Scotland (hence the beaming couple of Salmond and Trump above), a role of which Nicola Sturgeon has just relieved him. Did building an expensive golf course over some precious dunes near Aberdeen really get him that feather in his gap?

But banning him?

The husband, who had lived with my prep for a week, summed it up rather well: so is this the moment when we decide to bomb Syria and ban Trump?

December 9, 2015

Cuts to archaeology

When local government "savings" are meaning cuts to everything from frontline social services and home care to street lighting and pot-hole mending, it is hard to get people worked up about archaeology. But even some of the less headline-grabbing austerity measures are likely to have an impact for years to come.

One of our great archaeological success stories of recent years (and it is much admired abroad) has been the Portable Antiquities Scheme. Among other things, this has brought the "metal detecting community" into a much closer relationship with professional archaeologists, after a good few years of more or less open warfare. The idea is a very simple one. People who find things with their detectors on a Sunday afternoon's detectoring are encouraged (not forced) to report what they have discovered and get it properly identified -- and so to enable the professional archaeologists to plot what is coming up where, with all insights that brings into archaeological history of the region concerned.

Detectors have, of course, been responsible for some of the most glamorous finds over the last couple of decades (including the Staffordshire Hoard in 2009), But much more of what turns up, and often just as important for the big historical picture, is in the form of far less "wow" things (individual coins, the occasional Roman brooch... that kind of thing).

It goes without saying that, for the scheme to work, it needs the specialist staff locally to look at the finds and do the identifications.

Some of them are provided by the British Museum, which coordinates the PAS itself. But some key players are funded locally as part of the local archaeological service. And it's not hard to guess what's happening. Take Norfolk, the county where the PAS was first developed and trialled. Three posts (2.5 fulltime equivalents) in the archaeological Identification and Recording Service funded by the County Council are to be axed, leaving just three posts (also 2.5 fulltime equivalents) fully or part funded by the PAS. It is a team that has been dealing with over 15,000 archaeological finds each year, and the recording of these is making a big cumulative impact to our understanding of the history of the area.

A fifty percent cut will do more than cut the 'output' by fifty percent. If the whole process slows down and loses expertise, then people who find things will be far less keen to come and report them. And the historical benefits and good will of the system that has been built up will be lost.

OK, so it's not as affecting as the old lady whose already inadequate homecare is being cut by another ten minutes. But something else we will come to regret. And Norfolk cant be the only place this kind of thing is happening.

You can find out more here.

December 6, 2015

Museum legs in Vienna

After discussing the Romans on TV, I made it to the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, looking for my modern Roman emperors, and particularly keen to see the Kunstkammer, the extraordinary collection of exotic and virtuoso works of art (from cameos to automata) assembled by the Hapsburgs. I am still getting my eye in for emperors, and came across some excellent "12 Caesars" cameos from the late sixteenth century. But they were rather dwarfed by some of the other extravaganzas.

We are not necessarily talking great taste here, but for sheer bravura it takes some beating. Try this late sixteenth century version of Tantalus, whose head comes off (it's actually a bottle stopper).

Or this automaton of Diana on the back of a centaur (wasnt sure which parts actually moved!)

So that is where I spent most of my time, even though there were some great Caravaggios and Raphaels upstairs.

As for the practical side of the museum visit, then I can happily report that it is kitted out with the most comfortable chairs I have ever come across in a museum. They were not those usual padded benches, which are aimed to give your museum legs a rest but not to encourage you to sit for too long, but really comfy sofas to flop in.

And the Museum shop had its surprises too. It was the only museum I've visited for ages which really still takes its range of postcards seriously and has them prominently displayed, as you can see (and this was only part of it).

But in case you think it a little old-fashioned, it also had a ranfe of museum souvenirs that beat the standard fridge magnets etc. Pride of place in the shop went to a range of gold Kunsthistorisches Museum bicycle helmets, rather like my own, but not quite as solid. A match for the Kunstkammer in their way.

And what did I buy? A modest Christmas tree bauble celebrating Peter Breughel the Elder, which I will show you in due course if it gets back to the UK in one piece.

December 4, 2015

How to put the Romans on television

I am rather out of my usual habitat at the World Congress of Science and Factual Producers in Vienna a big media event, with all kinds of panels on such topics as "The 11 Commandments for Success with Online Content" and "The Rise of Multi-Platforms". It's all a bit different from "New Approaches to the Reign of Nero" or "Silius Italicus: texts and intertexts" that are the staples of my usual kind of conference. And the appearance of trays of wine after the sessions ending at 4 o' clock (yes, 4 o' clock) is not something you find at classical gathering; classical organisers take note. And instead of nervous post-docs trying to impress the professorial barons and get a leg up in the job market, it's nervous producers trying to pitch to the commissioning barons from the big tv channels.

I am here to be part of a panel on "More Bloody Romans" -- discussing all kinds of varieties of screen Romans with Thomas Viner from Arrow TV, Caterina Turroni, my producer from Lion TV, Martin Davidson of the BBC, and Heinrich Mayer-Moroni of Interspot Film, who has just made a documentary called "Lost City of Gladiators" (about the Roman town of Carnuntum) and was very nice to me when I was less than complimentary about some of his "recons".

The fact is, of course, as Martin Davidson underlined, there is no one way to put Romans on television: drama doc, recon, cgi, and yours truly spouting about a surviving Roman sandal, all have their place. But, in order to get a bit of fully frontal debate going, I decided to have a go at "recon" (you know the kind of stuff -- it's when the programme includes little dramatic features where you see Socrates die on screen surrounded by his disciples, or a pair of sleek bronzed gladiators fight to the death, or (if more extras are avaliable) hordes of poor barbarians making a bloody, brutal and ultimately doomed assault on the Roman legions.

One problem with this is that the actors aren't usually much good (I've never seen a convincing Socrates) and it is all a bit low budget (a handful of people wrapped in sheets, toga party style). If you want good recon, feature films have better actors and a bigger budget to do it properly, Gladiator being a classic example. But it's more the certainty it suggests and the sanitisation that annoy me.We don't actually know what an ancient battle looked like (and if we wanted a recon of a gladiatorial contest, wouldn't it be better to go to one of the hundreds of images the Romans themselves have left us?). And its always going to be a bit cleaned up for our screens. People died in real, they didn't just pretend to, slugging it out with rubber swords.

There was some feisty debate on all this (would anyone watch if there wasn't recon, would any TV company in Germany even commission a programme without it?), which continued afterwards. And I got quite interested in different ways of bringing the ancient world to life without the B list actors. How far could you use animation, for example? Or silhouettes which didn't actually talk (it's at "pass the grapes, Marcus", that things usually hit rock bottom for me).

Anyway that was yesterday. Today I'm sloping off to search out Roman emperors in the Kunsthistorisches Museum.

November 29, 2015

Oxford paintings and donnish portraits

Oxford is stuffed full of paintings. The colleges and university have been commissioning portraits of their members and their benefactors for centuries, and inheriting (or being given) a good sprinkling of other works of art from grateful friends and alumni. In fact, between them Oxford and Cambridge must be the biggest customers for painted portraits in the country, as almost every college has its master or mistress immortalised, as well as assorted other figures from many parts of the college community.

Right now I am having fun exploring the Oxford collection, in two wonderful volumes from the Public Catalogue Foundation (one here, the second here ). The material is also available online on the BBC Your Paintings website, but I have been enjoying flipping through the pages in the old-fashioned way. I'm a paid-up supporter of the PCF, so I'm biased, but I think not hugely so.

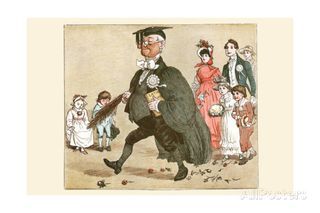

As you might expect there are plenty of rather pompous-looking male dons (it makes you remember, lest you ever forget, quite how white and male most of the almost 1000-year history of Oxford has been, and how rapid the recent change has been). Apart from the occasional benefactress or wife, women as subjects appear only in the late nineteenth century.

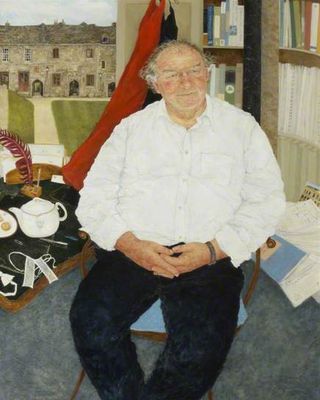

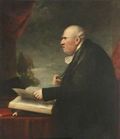

But there are many more striking and different paintings and styles than you would think. One is the recent triptych of the non-academic staff at All Souls by Benjamin Sullivan, pictured above (photo Simon Dunn of Scriptura) and you can read more here. But interestingly the idea of painting the staff rather than  just the 'top dons' goes back longer than you might have predicted. In 1929 the Fellows of Trinity commissioned a portrait (on the right, by Edwin Irvine Halliday, photo thanks to the college) of a long serving college "messenger"; not a job that has survived, I think!

just the 'top dons' goes back longer than you might have predicted. In 1929 the Fellows of Trinity commissioned a portrait (on the right, by Edwin Irvine Halliday, photo thanks to the college) of a long serving college "messenger"; not a job that has survived, I think!

But there are also a nice lot of variants on the standard "don-portrait" -- that is, the late middle-aged man, in suit or gown, sitting by desk with some appropriate book or trinket as prop.

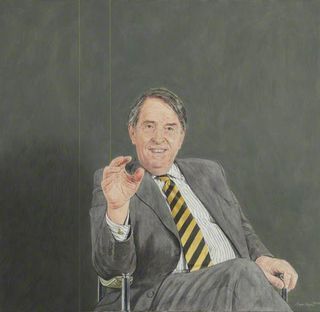

For me Jennifer McRae's portrait (above, photo courtesy Worcester College) of Richard Smethurst, a recent Provost of Worcester, a nice change. A the pared down versions by Bryan Organ also hit home. This is his version of John Barron, who was my first boss at Kings College London, before he went on to be the Master of St Peter's (photo courtesy college).

That raised hand just captures nicely his memorable affability, his sense of relaxation, as well as his conviction that hard work needed to be balanced with a good time, and that the rat race might just be for rats. Or is it just because I knew him that I think that?

The women sitters capture the variety too. There are some traditional and slightly scary 'frumps', as well as some pretty powerful ladies converted into chocolate box style. One lesson here is that quite a few good portrait artists have trouble whith finding a visual rhetoric for female success (either over or  under "feminizing" them).

under "feminizing" them).

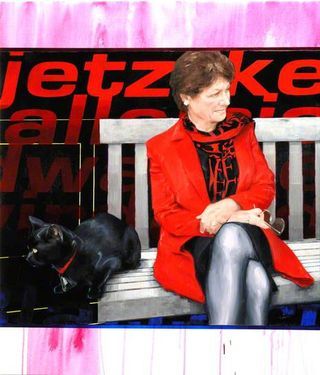

But Somerville should be proud, I think, of the paintings of two of its recent Principals. I'd happily live with Thomas Leveritt's portrait of Fiona Caldicott (right) and Claude Rogers's portrait of Janet Vaughan (left, copyright Crispin Rogers; both photos courtesy of the college).

Overall, though, I decided that the prize should go to the Pembroke College JCR Art Collection, entirely run and funded by the Junior Common Room, whose students since 1947 have paid a little subscription each term in order to buy work by emerging British artists, which can then be hung in student rooms. These students have had good advice and/or a good eye and overall their collection gives the official college collection, including a great master-portrait by Tom Phillips and a memorable version of a late eighteenth-century master, John Smyth, by Henry Howard (below right, courtesy of the college), a good run for its  money. The students can boast, among other things, a nice John Craxton, Mary Fedden and Duncan Grant.

money. The students can boast, among other things, a nice John Craxton, Mary Fedden and Duncan Grant.

The idea was, as now enshrined in the charity the collection has become, 'to advance the education of undergraduate members of Pembrole College, Oxford by the acquisition and display to them of artworks of high quality by contemporary artists'. It would work for me I think.

November 27, 2015

Christmas in the amphitheatre

The gallery in Sofia in which I sadly found no (modern) Roman emperors was the recently restored National Gallery. It seems that the old National Gallery of Bulgarian Art is mostly in mothballs, though it still holds the ethnographic collection (ie Bulgarian national costumes) and also attached to that a small display of gifts made to earlier heads of state. Below is a leather coat presented to Mr Zhivkov by a delegation from Mongolia (and there was much else along the same lines as you can glimpse).

The main collection has been moved to what was the Gallery of Foreign Art, which now has a wonderful extension at the back -- which is one of the very best modern museum extensions I have seen, although photos dont really do it justice.

On the morning I visited, it was full of kids (right) doing wholesome things such as they do in museums amongst what I might call the "ethnographica", which was  indeed beautifully displayed. That apart, I didnt quite think that they collection itself quite came up to the building, although I

indeed beautifully displayed. That apart, I didnt quite think that they collection itself quite came up to the building, although I  found a soft spot for some of the modern Bulgarian art (which had not been consigned to the Museum of Socialist Art). This included the rather elegant "cement factory" from 1987 (on the left) , and plenty more of that easy-on-the-eye type.

found a soft spot for some of the modern Bulgarian art (which had not been consigned to the Museum of Socialist Art). This included the rather elegant "cement factory" from 1987 (on the left) , and plenty more of that easy-on-the-eye type.

But strangely, once I'd skipped the archaeological museum (probably an error), I found it was my hotel that offered the best classical remains, heading up this post.

It turned out that the aptly named "Arena di Serdica" had been built over the remains of the amphitheatre of the Roman town of Sofia (Serdica) and the lowest floors featured some of the distinctive curved stone walls of the original structure. And in the very bowels of the building the hotel spa gave you the best view of the ruins of all.

In all sorts of ways, it was a very nice bit of "heritage" (and a nice spa), but there was a certain wry irony -- given what occasionally happened to Christians in amphitheatres -- to discover (as you see in the picture at the top) that what was left of its walls was lightly adorned with Christmas decorations.A far cry from lions.

November 22, 2015

A Museum of Socialist Art

I suppose it is obvious, but I hadn't quite realised that the use of Latin was one of the cultural targets of old Soviet bloc. But this weekend, in an attempt to recover from the joust with Boris and also in the lookout for modern images of Roman emperors, I took a break in Sofia (clearly, from a quick look at the passengers on the plane, a current favourite for lads' holidays). Very first stop was The Museum of Socialist Art, which isn't exactly in the centre of town and isn't open on Saturday or Sunday, but is well worth the taxi ride.

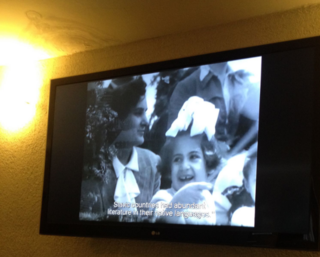

The Latin point was made in some of the communist "propaganda" videos on show. Although you can't quite read it, the subtitle on the picture above reads "Slavic countries had abundant literature in their native languages" -- and it immediately follows a sequence of a youth march where the commentary (referring to Western cuture) reads "nobles were ashamed of their native tongue, using Latin".

But the videos weren't the real highlight of the Museum (which is really an annex of the Ministry of Culture). Most striking of all was the sculpture garden, a home for dead statues of the Soviet era, like this marvellous Lenin:

or these women workers:

The whole thing was strikingly non-judgmental. But it felt as if one was in a strange limbo-land, with a group of art works that were making their way from reviled object to "heritage", but (perhaps thankfully -- as they were much more effective like this) hadn't quite made it yet.

The paintings -- all done between 1944 and 1989 -- were in the one inside gallery, comprising mostly scenes of industrial work and a whole series of almost classicizing history paintings, which made for a fantastic speedy education in Bulgarian history since the nineteenth century (and there's a lot of it).

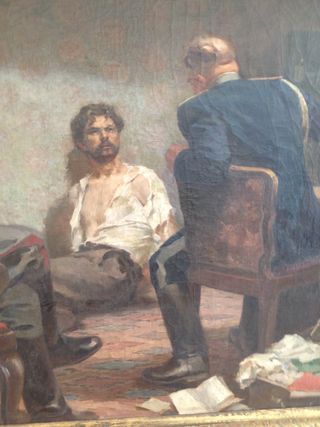

A particular favourite was "The Interrogation" (presumably of a young communist radical) by N Mirchev. That's a detail above, and here is the whole thing, complete with the louche fag-smoking general.

But there were plenty of others to ponder. Rather more, it has to said, than any images of Roman emperors. I had rather imagined that young Bulgarian artists in the nineteenth century would have been churning out scenes of the murder of Caligula etc. But if so, then they werent on display in any of te (many) galleries I visited.

November 19, 2015

Greece versus Rome

This evening I did a gig with Boris Johnson at Intelligence Squared: a cultural combat of ancient Greece versus ancient Rome. It was partly an event in benefit of "Classics for All", the charity that gets Classics teaching into state schools. Boris was supposed to be sticking up for Greece, Beard for Rome -- and there was a couple of thousand people there in Central Hall Westminster to hear and vote.

The pattern in Intelligence Squared debates is that a vote is taken when people come in, and again after the debate. I was well prepared to lose, but had hoped to have a bit of an inroad on the majority that I predicted for Greece at the first vote. Winning was not in my sights.

My case for the Romans was a sincere and honest one. They were a load of not nice bullies (but then so was every culture in the ancient Mediterranean), but they faced our problems with our wit and realism. That is to say, I talked about Roman debates about civil liberties (Catiline et al), about urban living (a snatch of Juvenal appeared) and about the rights of women (Alciphron got a look in here, and a reading from Letters of Courtesans thanks to my mate Helen) and about incorporation of foreigners.

Boris was all for democracy, the originary moment of literature and the rights of the individual. He had readings from Sappho and Pericles' funeral speech.And he was very very funny.

The end result was that, contrary to my own expectations (I thought Boris was rhetorically brilliant), I somehow pulled off an outright victory for the Romans -- after they started, on the first ballot, several percentage points behind. Quite what the killer point was I dont know. But I was very tough on Boris's view that you could make Greece equal Athens. OK, there are problems with even Athens. But you certainly can't make all of Greece be a landmark of intellectual inquiry and democracy, which Boris sort of tried. And even in Athens, the women issue is hard to get over.

So thank you all. I would love to know what any other attenders thought. I am going to bed a bit stunned.

November 14, 2015

Smalle Latine and Lesse Greeke

It is always very hard to judge what most people in the past knew. And it is particularly hard to judge how much Latin university students (men mostly) in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century knew, partly because of the nostalgic mythology that surrounds classical learning: the almost automatic assumption that our predecessors were always better than us, could knock off at sight perfect translations of anything from Livy to Lucian, Petronius to Pindar, without batting an eye-lid.

I tend to be suspicious of this. Just to focus on my own home patch, I realise that there were a few of the likes of Richard Jebb, who terrified his fellow student by walking into the exam room, picking up the translation paper and starting to write straight away. We���ve all known blokes like him, but he actually got his come-uppance in once of the translation papers into Greek verse, because he was in such a hurry and so much on autopilot that he translated one of the passages into the wrong metre (how often do we tell students READ THE DAMN QUESTION?). It meant that he didn���t get quite the stratospheric first class mark that he might have.

But generally I get the impression that, even those who had had years and years of training, they weren���t all that hot (certainly their curmudgeonly examiners were often complaining about ���standards���). And if they could rattle through some of the ���unseens��� it was because they had actually read the passages before over their decade or so of experience of Latin and Greek. Even in my day (a mere 40 years ago), we expected to have already read, in the course of what we had been studying, two or three of the ���unseen��� passages. To be honest, I think that is the only way that most non-Jebbs can translate Pindar ���at sight��� (it���s actually second sight!).

On the other side of the picture, I don���t have much faith in the so-called auto-didacts either: the untrained geniuses who taught themselves Greek with just a battered old primer and a copy of the Iliad. I mean, I may not be the best linguist in the world, but I am not bad��� and Greek is just harder than that. Or, at least, there is a big gap, between knowing the alphabet and spouting some paradigms and actually being able to read the stuff.

Some of this is a combination of gut feeling and long experience on my part. But when I was preparing a lecture I gave a couple of weeks ago at the British Academy (now online here), I did get a bit more data on this. I stopped to take a look at the late nineteenth-century Greek and Latin language tests set in the notorious Cambridge ���previous examination���, which tested the necessary ability in both Latin and Greek that was required for anyone to qualify for a Cambridge degree until after World War 1.

The Greek part of this became hugely controversial. And it was obviously a major mechanism of social exclusion. If you were at a school that didn���t teach Greek you were very unlikely to be able to pass the Greek test no matter how easy it was.

But it (and the Latin) certainly was easy ��� well within modern GCSE standards. Basically it was a question of learning a ���set book���. And in the case of the New Testament Greek questions (in the paper I looked at most carefully it was based on St Mark), it actually said, words to the effect of, ���you are advised to base your translation as closely as possible on the Authorised Version���. In other words, use the crib.

Nostalgia about standards is a dangerous thing,

(If you are interested in this, I have another go on nostalgia in the recent TLS; not sure if that link takes you directly through, but my review is called "Grammar School Gripes")

Mary Beard's Blog

- Mary Beard's profile

- 4110 followers