Grace Elliot's Blog: 'Familiar Felines.' , page 7

March 1, 2015

A Misbelief of Painters

My eldest son is working on the pieces for his final show of his fine art degree. Hopefully, this June he will graduate from art school and start earning a living as a professional artist. So it is with interest that I discovered the collective terms for a group of artists is a ‘misbelief’.This is one of those terms (a ‘misbelief of artists’) that make me think there was more humour around in the Middle Ages than we give credit for. The term ‘misbelief’ derives from the need of an artist to make a living (son take note!) and flatter the sitter. Thus, the corpulent patron appeared more svelte, and thin, reedy, clients were gifted broader shoulders and sturdier chests.

The job of the artist was to flatter – in exchange for which a pleased patron would be more likely to give employment in future. This makes sense because human nature dictates that no one wants to be remembered by posterity as looking anything less than your best. A skilled artist could conjure beauty where there was none, and rendered an image of the sitter as they wanted the world to see them. Perhaps one of the most famous examples, which also backfired, is Holbein’s portrait of Anne of Cleves. Anne of Cleves, by Holbein the Younger

Anne of Cleves, by Holbein the Younger

For those unfamiliar with the story, after the death of Queen Jane after the birth of Edward, King Henry VIII was now ready to marry again and on the prowl for his fourth wife. The ageing King still considered himself something of a catch, and whilst he understood the importance of making a good political match, it was a basic requirement that his future wife was beautiful. Henry despatched his court painter, Hans Holbein, to paint portraits of the likeliest candidates. One portrait depicted a serene lady dressed in red and gold, looking ethereal and regal. Henry fell in love with this woman, Anne of Cleves, and married her.

Unfortunately, the reality of of Henry’s ‘Flanders mare’ fell far short of the expectation raised by the portrait, he felt grossly misled, and the marriage ended in divorce. Detail from the painting of Christina of DenmarkWhat perhaps is less well known is Holbein’s portrait of another princess, Christina of Denmark. She is shown looking dour and plain, dressed in mourning black. Not surprisingly Henry overlooked her as not attractive enough – a lucky escape perhaps.What’s also interesting is that other portraits of Christina show her looking much more approachable and pretty. I can’t help suspecting she played the portrait game to her own ends, by putting forward an unappealing façade to put Henry off!

Detail from the painting of Christina of DenmarkWhat perhaps is less well known is Holbein’s portrait of another princess, Christina of Denmark. She is shown looking dour and plain, dressed in mourning black. Not surprisingly Henry overlooked her as not attractive enough – a lucky escape perhaps.What’s also interesting is that other portraits of Christina show her looking much more approachable and pretty. I can’t help suspecting she played the portrait game to her own ends, by putting forward an unappealing façade to put Henry off!

Christina of Denmark as a girlAnyhow, painters must find their own path and balance flattery with truth if they are to make a living. I suppose painting a realistic picture is all very well, but the chances are you won’t get repeat trade…then as now.

Christina of Denmark as a girlAnyhow, painters must find their own path and balance flattery with truth if they are to make a living. I suppose painting a realistic picture is all very well, but the chances are you won’t get repeat trade…then as now.

One of my son's pieces

One of my son's pieces

Click for a link to his Tumblr page

The job of the artist was to flatter – in exchange for which a pleased patron would be more likely to give employment in future. This makes sense because human nature dictates that no one wants to be remembered by posterity as looking anything less than your best. A skilled artist could conjure beauty where there was none, and rendered an image of the sitter as they wanted the world to see them. Perhaps one of the most famous examples, which also backfired, is Holbein’s portrait of Anne of Cleves.

Anne of Cleves, by Holbein the Younger

Anne of Cleves, by Holbein the YoungerFor those unfamiliar with the story, after the death of Queen Jane after the birth of Edward, King Henry VIII was now ready to marry again and on the prowl for his fourth wife. The ageing King still considered himself something of a catch, and whilst he understood the importance of making a good political match, it was a basic requirement that his future wife was beautiful. Henry despatched his court painter, Hans Holbein, to paint portraits of the likeliest candidates. One portrait depicted a serene lady dressed in red and gold, looking ethereal and regal. Henry fell in love with this woman, Anne of Cleves, and married her.

Unfortunately, the reality of of Henry’s ‘Flanders mare’ fell far short of the expectation raised by the portrait, he felt grossly misled, and the marriage ended in divorce.

Detail from the painting of Christina of DenmarkWhat perhaps is less well known is Holbein’s portrait of another princess, Christina of Denmark. She is shown looking dour and plain, dressed in mourning black. Not surprisingly Henry overlooked her as not attractive enough – a lucky escape perhaps.What’s also interesting is that other portraits of Christina show her looking much more approachable and pretty. I can’t help suspecting she played the portrait game to her own ends, by putting forward an unappealing façade to put Henry off!

Detail from the painting of Christina of DenmarkWhat perhaps is less well known is Holbein’s portrait of another princess, Christina of Denmark. She is shown looking dour and plain, dressed in mourning black. Not surprisingly Henry overlooked her as not attractive enough – a lucky escape perhaps.What’s also interesting is that other portraits of Christina show her looking much more approachable and pretty. I can’t help suspecting she played the portrait game to her own ends, by putting forward an unappealing façade to put Henry off!

Christina of Denmark as a girlAnyhow, painters must find their own path and balance flattery with truth if they are to make a living. I suppose painting a realistic picture is all very well, but the chances are you won’t get repeat trade…then as now.

Christina of Denmark as a girlAnyhow, painters must find their own path and balance flattery with truth if they are to make a living. I suppose painting a realistic picture is all very well, but the chances are you won’t get repeat trade…then as now. One of my son's pieces

One of my son's piecesClick for a link to his Tumblr page

Published on March 01, 2015 05:10

February 22, 2015

A Game of Swans: A Short History

Last week we learnt the collective term for ladies is ‘bevy’, and maidens are a ‘rage’. This week we discover the collective term for a group of swans is: A game of swans. So, taking out inspiration from history (rather than grammar!) lets look further into the history of swan keeping.

A Game of Swans

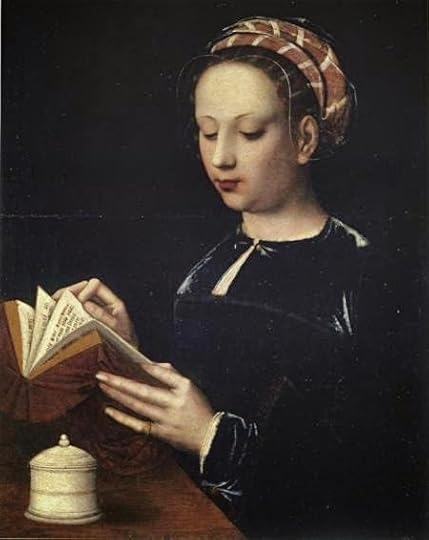

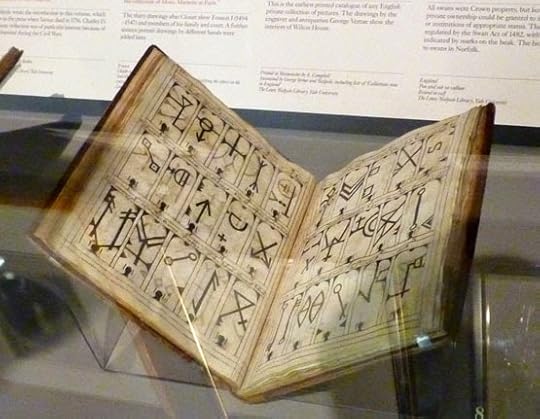

Swans have long been associated with royalty. This majestic bird is reputed to have been imported from Cyprus to England by King Richard I around 1189. This was widely held as fact until the middle of the 20th century when records came to light of an inventory of a feast served to King Henry III at Winchester in 1247. An original register of swan marksThe banquet included 40 swans that had been collected from all over the kingdom, including Cumberland in the north, and Somerset in the west. Now the swans are not rapid breeders in the same way rabbits are, and it seems unlikely that the wild swan population was so diversely spread in such a relatively short space of time.

An original register of swan marksThe banquet included 40 swans that had been collected from all over the kingdom, including Cumberland in the north, and Somerset in the west. Now the swans are not rapid breeders in the same way rabbits are, and it seems unlikely that the wild swan population was so diversely spread in such a relatively short space of time.

Swan marksWhatever their origins, their elegance and beauty was laid claim to by royalty and ordinary folk were not allowed to own them. However, this didn’t stop illegal ownership. By the late 1450s it wasn’t unheard of for yeoman to steal cygnets to keep themselves.

Swan marksWhatever their origins, their elegance and beauty was laid claim to by royalty and ordinary folk were not allowed to own them. However, this didn’t stop illegal ownership. By the late 1450s it wasn’t unheard of for yeoman to steal cygnets to keep themselves.

Swan upping

Swan upping

In 1483 a royal decree was passed which stated that all birds belonged to the crown, unless the ’owner’ had been granted a special dispensation. In these cases the birds were marked with a ‘swan mark’ on the beak so as to identify them.

Each mark was registered, and the design was usually complex, perhaps incorporating part of the coat of arms of the nobleman who was lucky enough to be permitted to own the birds. It was during Queen Elizabeth I’s reign that the register of swan marks was at its largest with around 900 marks registered. Swan upping on the Thames at Richmond

Swan upping on the Thames at Richmond

Of course, the birds had to be marked and this lead to an annual ritual of ‘swan-upping’. This involved visiting the riverbanks where the birds breed to catch the newly hatched cygnets and mark them.

A court proceeding from 1722 gives a glimpse into the ritual that was sometimes involved with swan upping. “…agreed to go swan-upping on the first Monday in August…the court desired the Renter Warden would be pleased to provide a dinner, three six-oared barges to carry the company up water…” Queen Elizabeth II attending a swan upping

Queen Elizabeth II attending a swan upping

With the passing centuries, people became more aware of the cruelty involved with permanently marking a bird’s beak. The RSPCA became involved in 1878 and as a result the practice dwindled and due to public pressure, stopped altogether. However, the correct term for a group of swans remains – as a ‘game of swans’.

A Game of Swans

Swans have long been associated with royalty. This majestic bird is reputed to have been imported from Cyprus to England by King Richard I around 1189. This was widely held as fact until the middle of the 20th century when records came to light of an inventory of a feast served to King Henry III at Winchester in 1247.

An original register of swan marksThe banquet included 40 swans that had been collected from all over the kingdom, including Cumberland in the north, and Somerset in the west. Now the swans are not rapid breeders in the same way rabbits are, and it seems unlikely that the wild swan population was so diversely spread in such a relatively short space of time.

An original register of swan marksThe banquet included 40 swans that had been collected from all over the kingdom, including Cumberland in the north, and Somerset in the west. Now the swans are not rapid breeders in the same way rabbits are, and it seems unlikely that the wild swan population was so diversely spread in such a relatively short space of time.

Swan marksWhatever their origins, their elegance and beauty was laid claim to by royalty and ordinary folk were not allowed to own them. However, this didn’t stop illegal ownership. By the late 1450s it wasn’t unheard of for yeoman to steal cygnets to keep themselves.

Swan marksWhatever their origins, their elegance and beauty was laid claim to by royalty and ordinary folk were not allowed to own them. However, this didn’t stop illegal ownership. By the late 1450s it wasn’t unheard of for yeoman to steal cygnets to keep themselves.

Swan upping

Swan uppingIn 1483 a royal decree was passed which stated that all birds belonged to the crown, unless the ’owner’ had been granted a special dispensation. In these cases the birds were marked with a ‘swan mark’ on the beak so as to identify them.

Each mark was registered, and the design was usually complex, perhaps incorporating part of the coat of arms of the nobleman who was lucky enough to be permitted to own the birds. It was during Queen Elizabeth I’s reign that the register of swan marks was at its largest with around 900 marks registered.

Swan upping on the Thames at Richmond

Swan upping on the Thames at RichmondOf course, the birds had to be marked and this lead to an annual ritual of ‘swan-upping’. This involved visiting the riverbanks where the birds breed to catch the newly hatched cygnets and mark them.

A court proceeding from 1722 gives a glimpse into the ritual that was sometimes involved with swan upping. “…agreed to go swan-upping on the first Monday in August…the court desired the Renter Warden would be pleased to provide a dinner, three six-oared barges to carry the company up water…”

Queen Elizabeth II attending a swan upping

Queen Elizabeth II attending a swan upping

With the passing centuries, people became more aware of the cruelty involved with permanently marking a bird’s beak. The RSPCA became involved in 1878 and as a result the practice dwindled and due to public pressure, stopped altogether. However, the correct term for a group of swans remains – as a ‘game of swans’.

Published on February 22, 2015 14:06

February 15, 2015

A Rage of Maidens and a Bevy of Ladies

‘Maidens’ is a delightfully old-fashioned word that sums up images of wholesome milk-maids blushing coyly when the handsome squire glances in her direction (or is that just me?) In the 15th century the change from girl to woman started at around 12 years of age, and represented a ‘perfect age’ in a romantic way. However, did you know there is a collective term for a group of maidens, and it is – a rage of maidens. Hmmm.

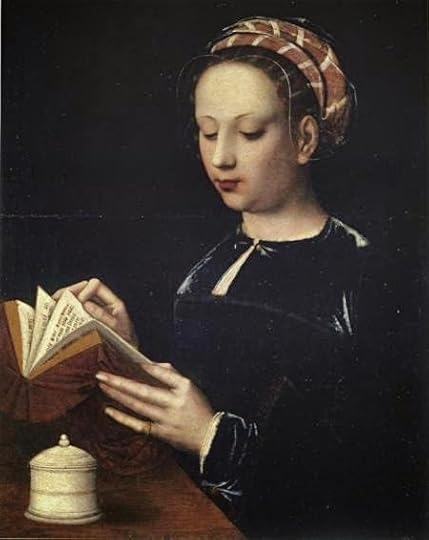

Vermeer's milk-maid

Vermeer's milk-maid

Apparently, in this context ‘rage’ is a derivative of a 15th century word which means to romp –or play wantonly. (There goes the image of coy blushes!) Whether this is a reflection on the social attitude of our maidens is anybody’s guess, however, the 15th century was perhaps more realistic about a woman’s nature urges than society was just a couple of centuries later. An aristocratic ladySo what of more mature ladies? The collective term for them is perhaps more familiar to us – as a ‘bevy of ladies’ – (a bevy of beauties?) This term can be traced back to 1702 and John Kersey’s New English Dictionary. The term ‘bevy’ was also appropriate for groups of roe (deer), quails, or larks. Along with these other delicate creatures, our bevy of ladies was upper class and refined.It is oddly appropriate to group ladies with livestock, because in the 18thcentury a woman was indeed the property of her husband and used mainly for breeding – her role being to produce heirs.

An aristocratic ladySo what of more mature ladies? The collective term for them is perhaps more familiar to us – as a ‘bevy of ladies’ – (a bevy of beauties?) This term can be traced back to 1702 and John Kersey’s New English Dictionary. The term ‘bevy’ was also appropriate for groups of roe (deer), quails, or larks. Along with these other delicate creatures, our bevy of ladies was upper class and refined.It is oddly appropriate to group ladies with livestock, because in the 18thcentury a woman was indeed the property of her husband and used mainly for breeding – her role being to produce heirs.

Roe deer

Roe deer

There was a less poetic term for her less salubrious sisters in arms, those who were paid for providing pleasure for men, and it is ‘a herd of harlots’. In medieval times prostitution was rife but widely accepted. St Thomas Aquinas wrote:‘If prostitution were to be suppressed, careless lusts would overthrow society.’ A detail from Hogarth's 'The Harlot's Progress'Society had its own way of dealing with prostitutes, preventing their company from sullying respectable women, by confining them to certain areas. However, it was natural for the prostitutes to seek out trade where it was most likely to be found. Therefore they congregated around taverns, universities, and popular bathing houses, and calling them a herd is perhaps another way of marking them as livestock.

A detail from Hogarth's 'The Harlot's Progress'Society had its own way of dealing with prostitutes, preventing their company from sullying respectable women, by confining them to certain areas. However, it was natural for the prostitutes to seek out trade where it was most likely to be found. Therefore they congregated around taverns, universities, and popular bathing houses, and calling them a herd is perhaps another way of marking them as livestock.

Vermeer's milk-maid

Vermeer's milk-maidApparently, in this context ‘rage’ is a derivative of a 15th century word which means to romp –or play wantonly. (There goes the image of coy blushes!) Whether this is a reflection on the social attitude of our maidens is anybody’s guess, however, the 15th century was perhaps more realistic about a woman’s nature urges than society was just a couple of centuries later.

An aristocratic ladySo what of more mature ladies? The collective term for them is perhaps more familiar to us – as a ‘bevy of ladies’ – (a bevy of beauties?) This term can be traced back to 1702 and John Kersey’s New English Dictionary. The term ‘bevy’ was also appropriate for groups of roe (deer), quails, or larks. Along with these other delicate creatures, our bevy of ladies was upper class and refined.It is oddly appropriate to group ladies with livestock, because in the 18thcentury a woman was indeed the property of her husband and used mainly for breeding – her role being to produce heirs.

An aristocratic ladySo what of more mature ladies? The collective term for them is perhaps more familiar to us – as a ‘bevy of ladies’ – (a bevy of beauties?) This term can be traced back to 1702 and John Kersey’s New English Dictionary. The term ‘bevy’ was also appropriate for groups of roe (deer), quails, or larks. Along with these other delicate creatures, our bevy of ladies was upper class and refined.It is oddly appropriate to group ladies with livestock, because in the 18thcentury a woman was indeed the property of her husband and used mainly for breeding – her role being to produce heirs.

Roe deer

Roe deerThere was a less poetic term for her less salubrious sisters in arms, those who were paid for providing pleasure for men, and it is ‘a herd of harlots’. In medieval times prostitution was rife but widely accepted. St Thomas Aquinas wrote:‘If prostitution were to be suppressed, careless lusts would overthrow society.’

A detail from Hogarth's 'The Harlot's Progress'Society had its own way of dealing with prostitutes, preventing their company from sullying respectable women, by confining them to certain areas. However, it was natural for the prostitutes to seek out trade where it was most likely to be found. Therefore they congregated around taverns, universities, and popular bathing houses, and calling them a herd is perhaps another way of marking them as livestock.

A detail from Hogarth's 'The Harlot's Progress'Society had its own way of dealing with prostitutes, preventing their company from sullying respectable women, by confining them to certain areas. However, it was natural for the prostitutes to seek out trade where it was most likely to be found. Therefore they congregated around taverns, universities, and popular bathing houses, and calling them a herd is perhaps another way of marking them as livestock.

Published on February 15, 2015 11:24

February 8, 2015

A Short History of the Yoyo

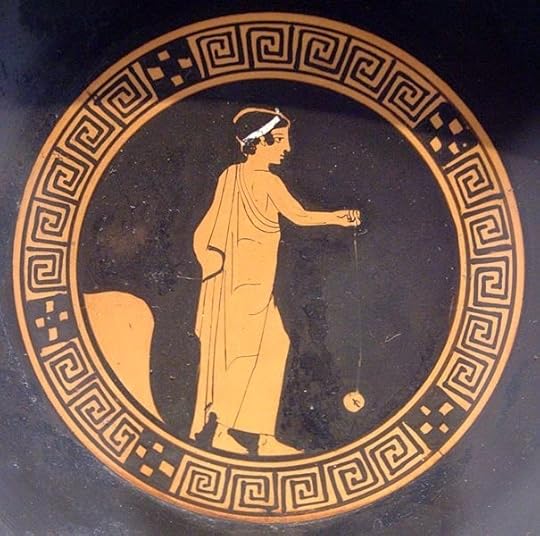

When do you think the yoyo was invented? a) 25 years agob) 250 years agoc) 2,500 years agod) None of these

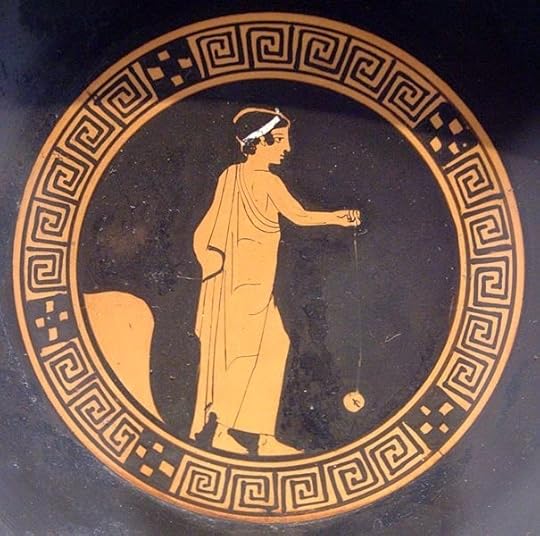

If you chose answer c), then give yourself a pat on the back. According to urban myth, the yoyo is the second oldest toy (the first is the doll) to have been invented. In ancient Greeks, children played with yoyos made of terracotta, metal, and wood. The two halves of these yoyos were decorated with pictures of Greek gods. Around 400 years ago, in the Philippines, yoyos were used as weapons. Agreed, they weren’t toys, but altogether more serious objects with studs and razor sharp edges that were attached to 20 foot ropes and thrown at the enemy (presumably, you took a lot of care when the yoyo returned to the thrower). Indeed, the word ‘yoyo’ meant ‘to return to the sender’.

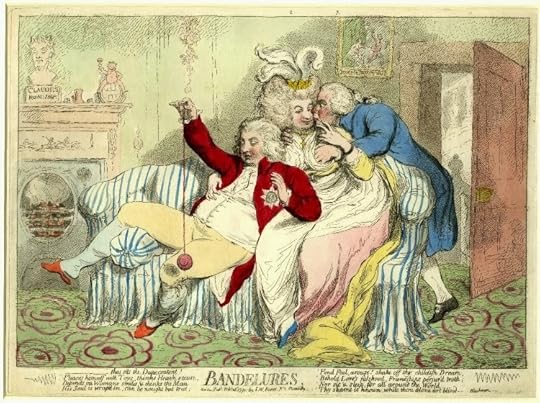

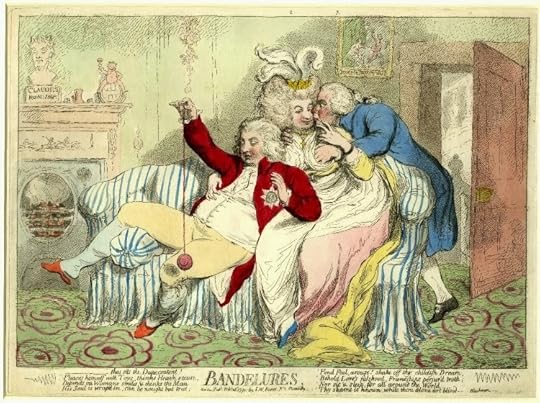

As the 1800s dawned the yoyo transferred from the Orient to Europe. It was initially known as the bandalore, whirly gig, or Princes of Wales toy. This print by Gillray, showing the Prince reclining on a sofa whilst dallying with a yoyo, offers some explanation as to why the device was linked to him in name. Also, around the same time, 1789, there is a painting of a young dauphin, then aged 4 years old, the future, King Louis XVII playing with a yoyo. The device first gained popularity in France. Napoleon was known to carry and use a yoyo, -possibly the equivalent of a PSP or hand-held gaming device in the late 18th century! Apparently he was seen playing with a yoyo on the eve of the Battle of Waterloo.For a period of around 20 years, the yoyo was the ‘must have’ have fashion accessory for adults, and described as offering ‘stress relief’. It wasn’t until after this that the yoyo became labelled as a childrens’ toy.

It was about the 1860s that the yoyo became popular in America, and patents for the toy were posted in Cincinnati. These patents mention improvements such as ‘weighting’, which improved the fly of the yoyo, and devices that acted as a flywheel for better yoyo returned. It was from there that the yoyo flourished and the devices we recognize in the modern day were born.

If you chose answer c), then give yourself a pat on the back. According to urban myth, the yoyo is the second oldest toy (the first is the doll) to have been invented. In ancient Greeks, children played with yoyos made of terracotta, metal, and wood. The two halves of these yoyos were decorated with pictures of Greek gods. Around 400 years ago, in the Philippines, yoyos were used as weapons. Agreed, they weren’t toys, but altogether more serious objects with studs and razor sharp edges that were attached to 20 foot ropes and thrown at the enemy (presumably, you took a lot of care when the yoyo returned to the thrower). Indeed, the word ‘yoyo’ meant ‘to return to the sender’.

As the 1800s dawned the yoyo transferred from the Orient to Europe. It was initially known as the bandalore, whirly gig, or Princes of Wales toy. This print by Gillray, showing the Prince reclining on a sofa whilst dallying with a yoyo, offers some explanation as to why the device was linked to him in name. Also, around the same time, 1789, there is a painting of a young dauphin, then aged 4 years old, the future, King Louis XVII playing with a yoyo. The device first gained popularity in France. Napoleon was known to carry and use a yoyo, -possibly the equivalent of a PSP or hand-held gaming device in the late 18th century! Apparently he was seen playing with a yoyo on the eve of the Battle of Waterloo.For a period of around 20 years, the yoyo was the ‘must have’ have fashion accessory for adults, and described as offering ‘stress relief’. It wasn’t until after this that the yoyo became labelled as a childrens’ toy.

It was about the 1860s that the yoyo became popular in America, and patents for the toy were posted in Cincinnati. These patents mention improvements such as ‘weighting’, which improved the fly of the yoyo, and devices that acted as a flywheel for better yoyo returned. It was from there that the yoyo flourished and the devices we recognize in the modern day were born.

Published on February 08, 2015 09:36

January 29, 2015

London Life: Victorian Coffee Sellers

My youngest son is into Warhammer. Apparently the hobby isn’t as popular in the US, and recently he overheard one American gamer explaining to another, how Warhammer outlets are: ‘In every town in the UK, they’re like Starbucks over there. ‘.

A game of Warhammer in progressWhen my son told me this I laughed. The idea seemed absurd. Then I realised how true it is, that there is a Warhammer shop in pretty much every major town. But also, what does that say about the popularity of Starbucks? Which leads us neatly onto the topic of today’s blog post – coffee shops, or more precisely – selling coffee.If you’ve read my post on the EHFA blog about an enterprising Victorian photographer, you will know my current bedtime reading is Henry Mayhew’s book, ‘London Labour and the London Poor’. First published in volumes during 1851-2, his great work chronicles everyday life as he saw it around him on London streets. Which leads me back to coffee selling.

A game of Warhammer in progressWhen my son told me this I laughed. The idea seemed absurd. Then I realised how true it is, that there is a Warhammer shop in pretty much every major town. But also, what does that say about the popularity of Starbucks? Which leads us neatly onto the topic of today’s blog post – coffee shops, or more precisely – selling coffee.If you’ve read my post on the EHFA blog about an enterprising Victorian photographer, you will know my current bedtime reading is Henry Mayhew’s book, ‘London Labour and the London Poor’. First published in volumes during 1851-2, his great work chronicles everyday life as he saw it around him on London streets. Which leads me back to coffee selling.

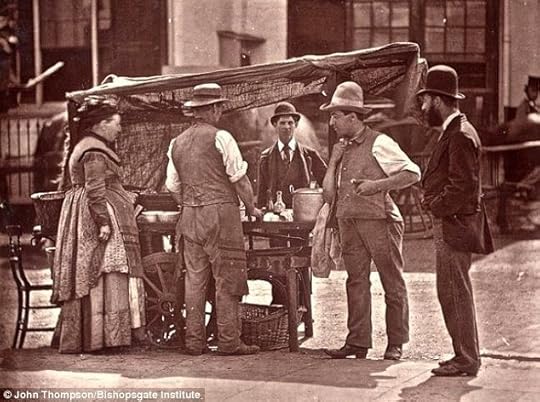

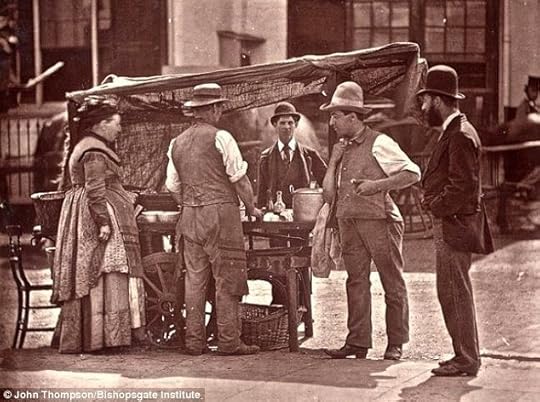

A photograph of a typical street vendor selling coffee

A photograph of a typical street vendor selling coffee

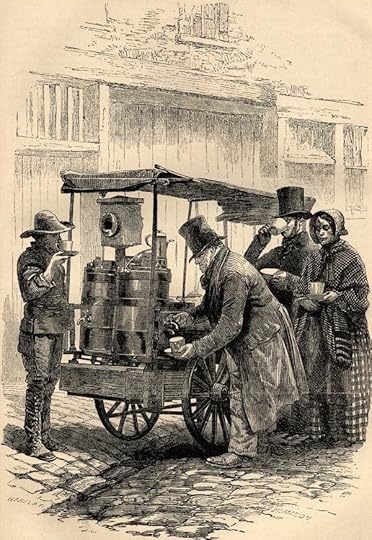

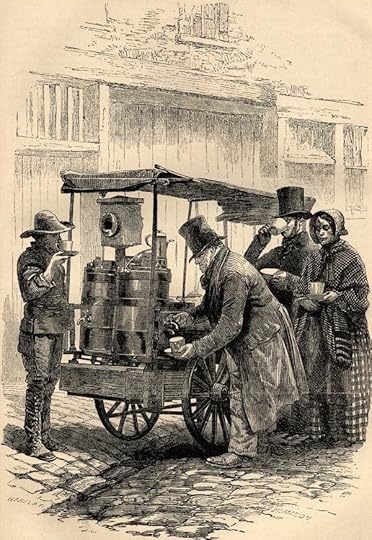

Is that Queen Victoria herself on the far left?Mayhew writes evocatively about the barrows that popped up on street corners, selling tea and coffee to other traders, market goers, and the general public. But this was a relatively recent innovation, because 20 years previously the beverage on sale was ‘saloop’. This prompted a cross reference with a dictionary to find saloop was a hot drink made from sassafras with added milk and sugar. Of course, then I had to find out what sassafras is – turns out it’s an evergreen tree that likes hot humid conditions and looks a bit like laurel but with larger leaves.Anyhow, inexplicably (or perhaps because tea and coffee taste nicer, and perhaps was being taxed less so was more affordable) saloop went out of fashion around about the time Victoria ascended to the throne, and beverages we still recognize today took over. The illustration of a coffee seller taken

The illustration of a coffee seller taken

from Henry Mayhew's book.

Note the lamp for night-time illuminationMayhew records how these coffee vendors enhanced their profits by blending coffee beans with cheaper additives such as chicory, or cheaper still – baked carrots or saccharin root. Apparently 4,000 – 5,000 tons of chicory was grown each year, the majority of which all went to coffee adulteration.The people running the stalls were often cabmen, policemen, artisans, or labourers not able to earn a living in the trade which they were apprenticed in. Some opened their stalls at midnight, specifically to cater for the ‘night-life’. The most lucrative pitch was said to be on the corner of Duke Street and Oxford Street, in London, with the best trade being done on market days.

A final thought. I wonder what the Victorians drank their street-bought coffee in? Cat coffee art

Cat coffee art

Presumably there were no disposable paper cups, and I wouldn’t have thought you’d take a mug wherever you went. This must mean the sellers leant out cups…hmmm…doesn’t sound terribly hygienic.

A game of Warhammer in progressWhen my son told me this I laughed. The idea seemed absurd. Then I realised how true it is, that there is a Warhammer shop in pretty much every major town. But also, what does that say about the popularity of Starbucks? Which leads us neatly onto the topic of today’s blog post – coffee shops, or more precisely – selling coffee.If you’ve read my post on the EHFA blog about an enterprising Victorian photographer, you will know my current bedtime reading is Henry Mayhew’s book, ‘London Labour and the London Poor’. First published in volumes during 1851-2, his great work chronicles everyday life as he saw it around him on London streets. Which leads me back to coffee selling.

A game of Warhammer in progressWhen my son told me this I laughed. The idea seemed absurd. Then I realised how true it is, that there is a Warhammer shop in pretty much every major town. But also, what does that say about the popularity of Starbucks? Which leads us neatly onto the topic of today’s blog post – coffee shops, or more precisely – selling coffee.If you’ve read my post on the EHFA blog about an enterprising Victorian photographer, you will know my current bedtime reading is Henry Mayhew’s book, ‘London Labour and the London Poor’. First published in volumes during 1851-2, his great work chronicles everyday life as he saw it around him on London streets. Which leads me back to coffee selling.

A photograph of a typical street vendor selling coffee

A photograph of a typical street vendor selling coffeeIs that Queen Victoria herself on the far left?Mayhew writes evocatively about the barrows that popped up on street corners, selling tea and coffee to other traders, market goers, and the general public. But this was a relatively recent innovation, because 20 years previously the beverage on sale was ‘saloop’. This prompted a cross reference with a dictionary to find saloop was a hot drink made from sassafras with added milk and sugar. Of course, then I had to find out what sassafras is – turns out it’s an evergreen tree that likes hot humid conditions and looks a bit like laurel but with larger leaves.Anyhow, inexplicably (or perhaps because tea and coffee taste nicer, and perhaps was being taxed less so was more affordable) saloop went out of fashion around about the time Victoria ascended to the throne, and beverages we still recognize today took over.

The illustration of a coffee seller taken

The illustration of a coffee seller takenfrom Henry Mayhew's book.

Note the lamp for night-time illuminationMayhew records how these coffee vendors enhanced their profits by blending coffee beans with cheaper additives such as chicory, or cheaper still – baked carrots or saccharin root. Apparently 4,000 – 5,000 tons of chicory was grown each year, the majority of which all went to coffee adulteration.The people running the stalls were often cabmen, policemen, artisans, or labourers not able to earn a living in the trade which they were apprenticed in. Some opened their stalls at midnight, specifically to cater for the ‘night-life’. The most lucrative pitch was said to be on the corner of Duke Street and Oxford Street, in London, with the best trade being done on market days.

A final thought. I wonder what the Victorians drank their street-bought coffee in?

Cat coffee art

Cat coffee artPresumably there were no disposable paper cups, and I wouldn’t have thought you’d take a mug wherever you went. This must mean the sellers leant out cups…hmmm…doesn’t sound terribly hygienic.

Published on January 29, 2015 08:51

January 14, 2015

Mud-larks of London: Dirty Endeavours on the Banks of the Thames

What is a mud-lark? After 24 hours of constant rain the ground has turned to slush, which seems as good an excuse as any to post about mud-larks.

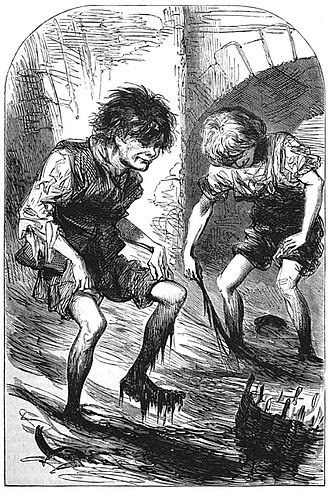

The Mud lark -

The Mud lark -

Illustration from Mayhew's

London Labour and the London PoorIn Victorian times necessity was the mother of invention and many poor people were driven to extraordinary lengths to make a living. A mud-lark is one such example, where people survived by scavenging through the mud left by the receding water of tidal rivers. The Thames is a capitol example as it was a water-way busy with all types of shipping where there was the potential for crew or passengers to drop things overboard. Mud larks circa 1871Mundane TreasureIn London, the mud-larks worked both banks of the Thames, covering a large area between Vauxhall Bridge and Woolwich. They weren't expecting to find gold, silver, or precious stones, - their treasure was of an altogether more mundane sort such as coal, rope, old-iron, copper nails, or even bones. Anything that might have come detached from a ship, or fallen overboard during repairs, had value to the mud-lark.

Mud larks circa 1871Mundane TreasureIn London, the mud-larks worked both banks of the Thames, covering a large area between Vauxhall Bridge and Woolwich. They weren't expecting to find gold, silver, or precious stones, - their treasure was of an altogether more mundane sort such as coal, rope, old-iron, copper nails, or even bones. Anything that might have come detached from a ship, or fallen overboard during repairs, had value to the mud-lark.

Boldness RewardedSometimes the mud-lark become over bold, such as one boy (as described by Henry Mayhew, the chronicler of Victorian life) who got fed up picking up coal from the shoreline and climbed on board a empty coal barge, where he swept up the leavings. His endeavor earned him 7 days imprisonment in a House of Correction. Not that he seemed to mind too much as he remarked that he preferred incarceration to being a mud-lark, as at least had a meal every night.

Caps for BasketsIndeed, the mud-larks arouse Mr. Mayhew's pity as he remarks that at one set of stairs (down to the fore-shore) he counted a dozen children wading through the mud, aged between 6 and 12 years old. Muddy slush dripped from their clothes and they left a puddle where they stood. When their basket was full, they'd remove their cap and fill it – adding to the general impression of filth and dirt. Spending all their time in mud, it wasn't worth wearing shoes (not that they could afford them), but these children felt the cold just like any other. "It is very cold in winter, to stand in the mud without shoes." A mud-lark The tidal shore of the Thames, as seen from the Millenium Bridge

The tidal shore of the Thames, as seen from the Millenium Bridge

Note the Shard in the background.The only positive in the dismal picture, it that mud-larking was an early form of recycling. The mud-lark sell scavenged coal to the poor. Whilst the iron, bones, and rope they sold to rag shops. Any tools, such as hammers or saws, they exchanged with seamen for biscuits and meat.

A Twist in the TaleHenry Mayhew wrote in 1951, and by 1904 although a person could claim "mud lark" as his occupation, public sensibility decreed it an unacceptable pursuit. The word however, re-emerged around 1936 when schoolchildren re-invented mud-larking but with a twist. This time they challenged passers-by to throw coins into the mud, and then entertained the onlookers by running to fetch (and pocket) it. The shore of the Thames A recent twist is that metal-detectorists who ply the banks of the Thames looking for historical artefacts, also call themselves mud-larks. Indeed, there is a London Mud-lark FB page, where examples of recent finds are shared.

The shore of the Thames A recent twist is that metal-detectorists who ply the banks of the Thames looking for historical artefacts, also call themselves mud-larks. Indeed, there is a London Mud-lark FB page, where examples of recent finds are shared.

The Mud lark -

The Mud lark -Illustration from Mayhew's

London Labour and the London PoorIn Victorian times necessity was the mother of invention and many poor people were driven to extraordinary lengths to make a living. A mud-lark is one such example, where people survived by scavenging through the mud left by the receding water of tidal rivers. The Thames is a capitol example as it was a water-way busy with all types of shipping where there was the potential for crew or passengers to drop things overboard.

Mud larks circa 1871Mundane TreasureIn London, the mud-larks worked both banks of the Thames, covering a large area between Vauxhall Bridge and Woolwich. They weren't expecting to find gold, silver, or precious stones, - their treasure was of an altogether more mundane sort such as coal, rope, old-iron, copper nails, or even bones. Anything that might have come detached from a ship, or fallen overboard during repairs, had value to the mud-lark.

Mud larks circa 1871Mundane TreasureIn London, the mud-larks worked both banks of the Thames, covering a large area between Vauxhall Bridge and Woolwich. They weren't expecting to find gold, silver, or precious stones, - their treasure was of an altogether more mundane sort such as coal, rope, old-iron, copper nails, or even bones. Anything that might have come detached from a ship, or fallen overboard during repairs, had value to the mud-lark. Boldness RewardedSometimes the mud-lark become over bold, such as one boy (as described by Henry Mayhew, the chronicler of Victorian life) who got fed up picking up coal from the shoreline and climbed on board a empty coal barge, where he swept up the leavings. His endeavor earned him 7 days imprisonment in a House of Correction. Not that he seemed to mind too much as he remarked that he preferred incarceration to being a mud-lark, as at least had a meal every night.

Caps for BasketsIndeed, the mud-larks arouse Mr. Mayhew's pity as he remarks that at one set of stairs (down to the fore-shore) he counted a dozen children wading through the mud, aged between 6 and 12 years old. Muddy slush dripped from their clothes and they left a puddle where they stood. When their basket was full, they'd remove their cap and fill it – adding to the general impression of filth and dirt. Spending all their time in mud, it wasn't worth wearing shoes (not that they could afford them), but these children felt the cold just like any other. "It is very cold in winter, to stand in the mud without shoes." A mud-lark

The tidal shore of the Thames, as seen from the Millenium Bridge

The tidal shore of the Thames, as seen from the Millenium BridgeNote the Shard in the background.The only positive in the dismal picture, it that mud-larking was an early form of recycling. The mud-lark sell scavenged coal to the poor. Whilst the iron, bones, and rope they sold to rag shops. Any tools, such as hammers or saws, they exchanged with seamen for biscuits and meat.

A Twist in the TaleHenry Mayhew wrote in 1951, and by 1904 although a person could claim "mud lark" as his occupation, public sensibility decreed it an unacceptable pursuit. The word however, re-emerged around 1936 when schoolchildren re-invented mud-larking but with a twist. This time they challenged passers-by to throw coins into the mud, and then entertained the onlookers by running to fetch (and pocket) it.

The shore of the Thames A recent twist is that metal-detectorists who ply the banks of the Thames looking for historical artefacts, also call themselves mud-larks. Indeed, there is a London Mud-lark FB page, where examples of recent finds are shared.

The shore of the Thames A recent twist is that metal-detectorists who ply the banks of the Thames looking for historical artefacts, also call themselves mud-larks. Indeed, there is a London Mud-lark FB page, where examples of recent finds are shared.

Published on January 14, 2015 08:40

January 7, 2015

Rubbish! A Short Muse on Why Dustbins are so Called

Rubbish!Refuse in on my mind a lot at the moment, because over the Christmas period our dustbin has not been emptied. When the dustmen come tomorrow, it will be a full 4 weeks since their last collection. Not great.

Dustbins are funny things. For instance, have you noticed how they have "No hot ashes" stamped into the side? This seems rather peculiar given that so many households rely on central heating now, and no longer have a hearth and a real fire. Even stranger when you think about it is the term "dustbin". (In fairness this is largely supplanted by "wheelie bin" but I'm of an age to still refer to a bin as a dustbin.) Have you ever wondered how they got this name?

There's an old saying: Where there's muck there's brass. Would it surprise you that dust was once a valuable commodity? In fact, in the 19thcentury the demand for dust was so great that dust-collectors paid the householder for the privilege of taking away their dirt, and then sold it on for a profit to brick manufacturers and for fertilizing poor soil.

So where did all the dust come from? Coal fires. White ash, cinders, and fragments of unconsumed coke were waste products from the coal fires used to supply heat, hot water, and cooking facilities to domestic houses. In the 1850s it was reckoned an average household burnt 11 tons per house, with poor people consuming around 2 tons. All of which created a considerable amount of dust and ash.

If this dust was simply emptied onto the street, the roads would have quickly become submerged beneath grey powder and filth. The answer was for each household to keep a bin in which to store the ash (a dust-bin), which was collected by a designated dust-contractor. The later needed the equipment to handle the waste, such as a horse, cart, baskets, shovels, and a buyer for the ash, or a plot of land on which to dispose of it.

The trade was so lucrative that dustmen paid for the privilege, and recouped outgoings by selling the dust on. However, as city's expanded, there was less and less land that needed fertilizing, and more and more households producing dust. Thus the market changed and it was no longer made business sense to pay for a dust-round. Instead, positions were reversed and parishes had to pay dust-contractors to take the rubbish away – a situation similar to today.

When Henry Mayhew wrote in 1851 about the dust-men of London, he reckoned there were 90 contractors, servicing around 300,000 houses – each looking after around 3,333 properties. Fascinating.

Speaking personally, I'd settle for less fascination and an empty bin. So let's hope the dustmen call tomorrow…

Dustbins are funny things. For instance, have you noticed how they have "No hot ashes" stamped into the side? This seems rather peculiar given that so many households rely on central heating now, and no longer have a hearth and a real fire. Even stranger when you think about it is the term "dustbin". (In fairness this is largely supplanted by "wheelie bin" but I'm of an age to still refer to a bin as a dustbin.) Have you ever wondered how they got this name?

There's an old saying: Where there's muck there's brass. Would it surprise you that dust was once a valuable commodity? In fact, in the 19thcentury the demand for dust was so great that dust-collectors paid the householder for the privilege of taking away their dirt, and then sold it on for a profit to brick manufacturers and for fertilizing poor soil.

So where did all the dust come from? Coal fires. White ash, cinders, and fragments of unconsumed coke were waste products from the coal fires used to supply heat, hot water, and cooking facilities to domestic houses. In the 1850s it was reckoned an average household burnt 11 tons per house, with poor people consuming around 2 tons. All of which created a considerable amount of dust and ash.

If this dust was simply emptied onto the street, the roads would have quickly become submerged beneath grey powder and filth. The answer was for each household to keep a bin in which to store the ash (a dust-bin), which was collected by a designated dust-contractor. The later needed the equipment to handle the waste, such as a horse, cart, baskets, shovels, and a buyer for the ash, or a plot of land on which to dispose of it.

The trade was so lucrative that dustmen paid for the privilege, and recouped outgoings by selling the dust on. However, as city's expanded, there was less and less land that needed fertilizing, and more and more households producing dust. Thus the market changed and it was no longer made business sense to pay for a dust-round. Instead, positions were reversed and parishes had to pay dust-contractors to take the rubbish away – a situation similar to today.

When Henry Mayhew wrote in 1851 about the dust-men of London, he reckoned there were 90 contractors, servicing around 300,000 houses – each looking after around 3,333 properties. Fascinating.

Speaking personally, I'd settle for less fascination and an empty bin. So let's hope the dustmen call tomorrow…

Published on January 07, 2015 08:01

December 31, 2014

2014 - Top of the Posts!

A time of reflection.As 2014 draws to a close I hope it has been a happy and fruitful year for you all. On a personal level, it's been a year of changes and for a cautious person I made some bold decisions. Strange really, because this time last year I'd no inkling that I would give up the day job and strike out in a different direction.

At this time I like to look back and see which have been the most popular posts. It never ceases to amaze me that once again the runaway winner is Cat's Eyes: Seeing is Believing. With over 42,000 views in 2014 alone (not counting all the years its been top since first posted) I can only assume that the school curriculum includes the topic of light-reflective studs in the road and school children everywhere are eagerly Googling the subject.So, apart from Cat's Eyes, which were the most popular posts of 2014?In reverse order, they are:

#5 The Angels of St Helens

#4 Of Proper Gentlemen and Ladies

#3 A Short History of Wigs

#2 St Albans in the Times of the Wars of the Roses

#1 Mouse-skin Eyebrows: A short history of makeup

A huge thank you from me, to you – for visiting Fall in Love with History. At the time of writing the blog is just 2,619 visitors short of half-a-million readers – amazing! Thank you!

If you have any topics you would like featured in 2015, please leave a comment. I'd be happy to oblige. Kindest regards,

Grace x

At this time I like to look back and see which have been the most popular posts. It never ceases to amaze me that once again the runaway winner is Cat's Eyes: Seeing is Believing. With over 42,000 views in 2014 alone (not counting all the years its been top since first posted) I can only assume that the school curriculum includes the topic of light-reflective studs in the road and school children everywhere are eagerly Googling the subject.So, apart from Cat's Eyes, which were the most popular posts of 2014?In reverse order, they are:

#5 The Angels of St Helens

#4 Of Proper Gentlemen and Ladies

#3 A Short History of Wigs

#2 St Albans in the Times of the Wars of the Roses

#1 Mouse-skin Eyebrows: A short history of makeup

A huge thank you from me, to you – for visiting Fall in Love with History. At the time of writing the blog is just 2,619 visitors short of half-a-million readers – amazing! Thank you!

If you have any topics you would like featured in 2015, please leave a comment. I'd be happy to oblige. Kindest regards,

Grace x

Published on December 31, 2014 09:59

December 24, 2014

A Festive Quiz: some Georgian Slang

This week's blog post is by way of a festive quiz. Guess who this dapper fellow is – as described using Georgian slang.

"Our friend in no crack lay and has the best intentions when he enters your crib – even if he needs no locksmith's daughter to get in. He is a trifle fubsey in the mid-section and has crook shanks. He is brandy faced with a malmesbury nose topped with barnacles, and sporting a turnip pate. He is smartly dressed in matching red inexpressibles and an upper toge. "

Have you guessed the mystery fellow yet?

If you are left scratching your upper storey, here is a translation.

Our friend is no house-breaker and has the best intentions when he enters your house – even if he doesn't need a key to get in. He's a trifle plump around the tummy and has bandy legs. He is red-faced with a jolly red nose topped with spectacles, and a thatch of white hair. He is smartly dressed in matching red breeches and top coat.

Of course, it's Saint Nicholas – better known as Santa Claus!A very merry Christmas to one and all. Be of good cheer, and I'll see you again in the New Year.

Happy Christmas everyone!

Happy Christmas everyone!

Published on December 24, 2014 02:57

December 20, 2014

The Angels of St Helens - A Christmas Celebration

For the second year running the village of St Helens on the Isle of Wight is celebrating Christmas by inviting angels to visit. The community has come together to create angels as a means of raising money for local charities. So, without further procrastination meet the angels of St Helens.

An angel in the garden of a house on Latimer Road

An angel in the garden of a house on Latimer Road

The bus shelter on the green is converted into a manger

The bus shelter on the green is converted into a manger

A beer barrel angel outside the Vine public house

A beer barrel angel outside the Vine public house

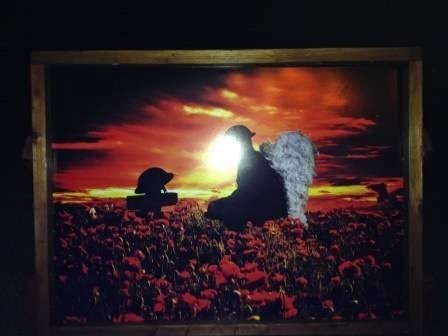

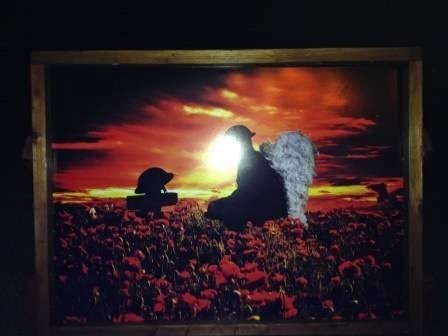

A tribute to World War I veterans

A tribute to World War I veterans

A painting on the village green A choir of angels made from plastic milk cartons!

A choir of angels made from plastic milk cartons!

Wine bottle angels outside a bistro

Wine bottle angels outside a bistro

A bay window angel

A bay window angel

Another front garden angel

Another front garden angel

An angelic neighbour

An angelic neighbour

A giant angel

A giant angel

The driftwood angel on the green

The driftwood angel on the green

Angelic shadows

Angelic shadows

And this one? I'm not so sure about this one...

And this one? I'm not so sure about this one...

An angel in the garden of a house on Latimer Road

An angel in the garden of a house on Latimer Road

The bus shelter on the green is converted into a manger

The bus shelter on the green is converted into a manger

A beer barrel angel outside the Vine public house

A beer barrel angel outside the Vine public house

A tribute to World War I veterans

A tribute to World War I veteransA painting on the village green

A choir of angels made from plastic milk cartons!

A choir of angels made from plastic milk cartons!

Wine bottle angels outside a bistro

Wine bottle angels outside a bistro

A bay window angel

A bay window angel

Another front garden angel

Another front garden angel

An angelic neighbour

An angelic neighbour

A giant angel

A giant angel

The driftwood angel on the green

The driftwood angel on the green

Angelic shadows

Angelic shadows

And this one? I'm not so sure about this one...

And this one? I'm not so sure about this one...

Published on December 20, 2014 13:17

'Familiar Felines.'

Following on from last weeks Halloween posting, today's blog post looks at the unwanted image of cats as the witches familiar - from the Norse Goddess Freya to lonely women in the middle ages.

The full Following on from last weeks Halloween posting, today's blog post looks at the unwanted image of cats as the witches familiar - from the Norse Goddess Freya to lonely women in the middle ages.

The full post can found at:

http://graceelliot-author.blogspot.com

...more

The full Following on from last weeks Halloween posting, today's blog post looks at the unwanted image of cats as the witches familiar - from the Norse Goddess Freya to lonely women in the middle ages.

The full post can found at:

http://graceelliot-author.blogspot.com

...more

- Grace Elliot's profile

- 156 followers