Grace Elliot's Blog: 'Familiar Felines.' , page 6

May 10, 2015

Quintessentially Victorian: the Crinoline

It is arguable that nothing is as quintessentially Victorian as the crinoline. You only need to see the silhouette of a woman wearing a crinoline to place her fashion in the Victorian period. Whilst the Georgian period went through a fad for ridiculously wide skirts, it is the 1850s and 60s that were the era of the hoop shaped skirt we call the crinoline.

The height of fashion in 1854

The height of fashion in 1854

A balloon like skirt is so evidently impractical, how did such a garb come into being? The roots of the answer are found in that traditional essential garment for women down the centuries – the petticoat.

Much of the time people in earlier centuries were cold. There was no central heating, and a fire in the hearth doesn’t throw heat very far. The answer was to rug up with layers of clothing so as to insulate the wearer from the worst of the icy drafts and inclement weather.

Petticoats for WarmthFor women this meant wearing petticoats under their gown. Indeed, a white cotton petticoat was usually worn over the corset but next to the skin. The layer was a simple shape and unadorned, since it needed washing on a regular basis. The satirical magazine "Punch"

The satirical magazine "Punch"

loved to poke fun at the wildly impractical crinoline

On top of the cotton petticoat came a flannel one- again simple in shape but perhaps with some decoration. Interestingly, this layer wasn’t full length but stopped just above the knee. These two layers were considered basic for women not matter what their class.

Fashionable LengthsJust as in the modern day hemlines rise and fall, in the Victorian period fashion was all to do with the width and silhouette of the skirt. However, wide skirts needed support to hold them out and show them off to best advantage. In the 1840s the solution was to stiffen the fabric of a petticoat. The cheapest way to do this was “cording” which was a process of threading string between concentric rings of stitching on a white petticoat.

Itchy and ScratchyBut as the decade progressed, the stiffness provided by cording was not sufficient to support the weight of ever-bigger skirts. This lead to a new innovation and fabric with horsehair woven in or a “Crin au Lin”. Stiff, spring, and light, an underskirt made in this fabric or a “Crinoline” could support a weighty skirt. The diameter of some crinolines was a disabling 6 feet

The diameter of some crinolines was a disabling 6 feet

Steel Cages (…a comment on women’s lives in general?)Horsehair, however, is scratchy and to overcome this in 1856 the steel crinoline was invented. This consisted of steel hoops suspended by tapes. This formed a cage like structure that was considerably lighter (and less itchy) than the original horsehair item.

And finally….perhaps crinoline makers were in league with fabric manufacturers, because the cages themselves were relatively inexpensive (retailing at about a third of the purchase price of a gown) and yet required many yards of fabric to make a skirt to cover it.

PS. Can you think of anything more quintessentially Victorian than a crinoline? Do leave a comment.

PSS - "Hope's Betrayal" has been signed by a well-known publishing house. The book will shortly become unavailable, whilst it undergoes a "wash and brush up" - so grab your copy now or face a wait...

Click for link

Click for link

The height of fashion in 1854

The height of fashion in 1854A balloon like skirt is so evidently impractical, how did such a garb come into being? The roots of the answer are found in that traditional essential garment for women down the centuries – the petticoat.

Much of the time people in earlier centuries were cold. There was no central heating, and a fire in the hearth doesn’t throw heat very far. The answer was to rug up with layers of clothing so as to insulate the wearer from the worst of the icy drafts and inclement weather.

Petticoats for WarmthFor women this meant wearing petticoats under their gown. Indeed, a white cotton petticoat was usually worn over the corset but next to the skin. The layer was a simple shape and unadorned, since it needed washing on a regular basis.

The satirical magazine "Punch"

The satirical magazine "Punch"loved to poke fun at the wildly impractical crinoline

On top of the cotton petticoat came a flannel one- again simple in shape but perhaps with some decoration. Interestingly, this layer wasn’t full length but stopped just above the knee. These two layers were considered basic for women not matter what their class.

Fashionable LengthsJust as in the modern day hemlines rise and fall, in the Victorian period fashion was all to do with the width and silhouette of the skirt. However, wide skirts needed support to hold them out and show them off to best advantage. In the 1840s the solution was to stiffen the fabric of a petticoat. The cheapest way to do this was “cording” which was a process of threading string between concentric rings of stitching on a white petticoat.

Itchy and ScratchyBut as the decade progressed, the stiffness provided by cording was not sufficient to support the weight of ever-bigger skirts. This lead to a new innovation and fabric with horsehair woven in or a “Crin au Lin”. Stiff, spring, and light, an underskirt made in this fabric or a “Crinoline” could support a weighty skirt.

The diameter of some crinolines was a disabling 6 feet

The diameter of some crinolines was a disabling 6 feetSteel Cages (…a comment on women’s lives in general?)Horsehair, however, is scratchy and to overcome this in 1856 the steel crinoline was invented. This consisted of steel hoops suspended by tapes. This formed a cage like structure that was considerably lighter (and less itchy) than the original horsehair item.

And finally….perhaps crinoline makers were in league with fabric manufacturers, because the cages themselves were relatively inexpensive (retailing at about a third of the purchase price of a gown) and yet required many yards of fabric to make a skirt to cover it.

PS. Can you think of anything more quintessentially Victorian than a crinoline? Do leave a comment.

PSS - "Hope's Betrayal" has been signed by a well-known publishing house. The book will shortly become unavailable, whilst it undergoes a "wash and brush up" - so grab your copy now or face a wait...

Click for link

Click for link

Published on May 10, 2015 12:14

May 3, 2015

Victorian Life: The Health Benefits of the Corset

Fashions come and go, but in Victorian times one item of apparel that was considered ‘de rigeur’ by women of all classes was the corset. So much so that even women in prison or the workhouse, were supplied with corsets.

Part of the reason was that 19th century medicine held that women’s internal organs needed support. It was said that a woman’s midriff was weak and not up to the job of supporting her womb. Ironically, this was a self-fulfilling prophecy because the constant use of corsets weakened the abdominal muscles.

Waisting AwayAny muscle when not used, tends to waste away (waist away? See what I did there!) and the abdominal muscles are no different. Instead of having the female version of a six-pack, the Victorian lady had muscles equivalent in tone to a blancmange – thanks to the corset. Indeed, if a Victorian lady left off her corset, she was likely to quickly feel vulnerable and tired, thanks to the lack of support – and hence confirming the reason for wearing one.

“Women who wear very tight stays complain that they cannot sit upright without them, nay are compelled to wear night stays in bed.” Female Beauty – Victorian periodical A x-ray from 1908 showing how

A x-ray from 1908 showing how

a corset compressed the lower ribcage

Upright PostureThus the corset also braced the back and helped a lady to have an elegant upright posture and bearing – something much admired at the time.

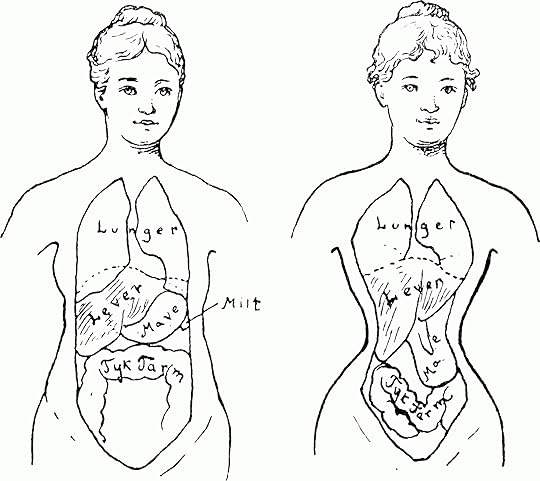

Warmth and ProtectionA corset was said to protect the delicate organs such as the kidneys. The garment kept in the body’s warmth and hence saved the kidneys from catching a chill. Indeed, the corset provided a valuable windproof weather, against the vagaries of the British climate. Normal anatomy on the left

Normal anatomy on the left

Corset restricted anatomy on the right

The Corset Not to BlameSo how come the corset has such a bad reputation as an instrument of subduing women and stopping them from leading active lives?

Mainstream medical thinking was that corsets were good, but could be made bad when laced too tightly. Unfortunately, the latter is exactly what happened because society admired a trim figure with a tiny waist – which meant women used every tool at their disposal to obtain just that.

It was the 1850s and 60s that saw tremendous pressure building to produce a tiny waist. Not only that, but it was positively encouraged, especially for young women with a husband to snare.

A Smaller Waist than a Toddler“When I left school at 17 my waist measured only 13 inches, it formerly having been 23 inches in circumference.”This was because fashionable schools actively worked on reducing the waists of their female charges. This was done by equipping the girls with a series of ever-smaller corsets. Of course being so tightly laced they could not eat large meals, and were forced to peck at food like a bird. Indeed, the corset was only removed for one hour per week for the girl to have a wash.

Contemporary Concerns

And finally…at the time people had concerns about the damage done by over-tight lacing, but the problem was no one could agree on how tight was too-tight. And remember that in addition, there was a cultural perception that an uncorseted woman was one of low morals – and you begin to see the mountain that had to be climbed to find a women’s undergarment that was both flattering and healthy.

Part of the reason was that 19th century medicine held that women’s internal organs needed support. It was said that a woman’s midriff was weak and not up to the job of supporting her womb. Ironically, this was a self-fulfilling prophecy because the constant use of corsets weakened the abdominal muscles.

Waisting AwayAny muscle when not used, tends to waste away (waist away? See what I did there!) and the abdominal muscles are no different. Instead of having the female version of a six-pack, the Victorian lady had muscles equivalent in tone to a blancmange – thanks to the corset. Indeed, if a Victorian lady left off her corset, she was likely to quickly feel vulnerable and tired, thanks to the lack of support – and hence confirming the reason for wearing one.

“Women who wear very tight stays complain that they cannot sit upright without them, nay are compelled to wear night stays in bed.” Female Beauty – Victorian periodical

A x-ray from 1908 showing how

A x-ray from 1908 showing howa corset compressed the lower ribcage

Upright PostureThus the corset also braced the back and helped a lady to have an elegant upright posture and bearing – something much admired at the time.

Warmth and ProtectionA corset was said to protect the delicate organs such as the kidneys. The garment kept in the body’s warmth and hence saved the kidneys from catching a chill. Indeed, the corset provided a valuable windproof weather, against the vagaries of the British climate.

Normal anatomy on the left

Normal anatomy on the leftCorset restricted anatomy on the right

The Corset Not to BlameSo how come the corset has such a bad reputation as an instrument of subduing women and stopping them from leading active lives?

Mainstream medical thinking was that corsets were good, but could be made bad when laced too tightly. Unfortunately, the latter is exactly what happened because society admired a trim figure with a tiny waist – which meant women used every tool at their disposal to obtain just that.

It was the 1850s and 60s that saw tremendous pressure building to produce a tiny waist. Not only that, but it was positively encouraged, especially for young women with a husband to snare.

A Smaller Waist than a Toddler“When I left school at 17 my waist measured only 13 inches, it formerly having been 23 inches in circumference.”This was because fashionable schools actively worked on reducing the waists of their female charges. This was done by equipping the girls with a series of ever-smaller corsets. Of course being so tightly laced they could not eat large meals, and were forced to peck at food like a bird. Indeed, the corset was only removed for one hour per week for the girl to have a wash.

Contemporary Concerns

And finally…at the time people had concerns about the damage done by over-tight lacing, but the problem was no one could agree on how tight was too-tight. And remember that in addition, there was a cultural perception that an uncorseted woman was one of low morals – and you begin to see the mountain that had to be climbed to find a women’s undergarment that was both flattering and healthy.

Published on May 03, 2015 12:24

April 26, 2015

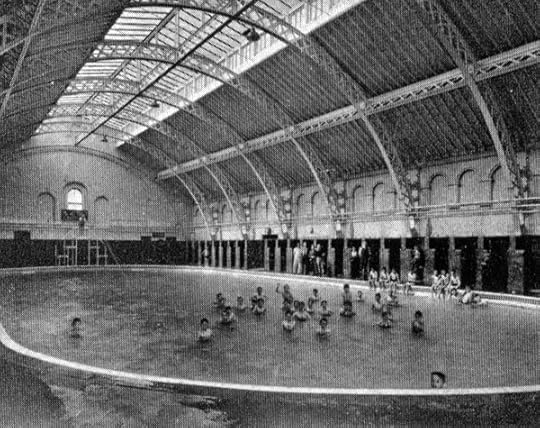

The Unexpected Origins of Victorian Swimming Baths

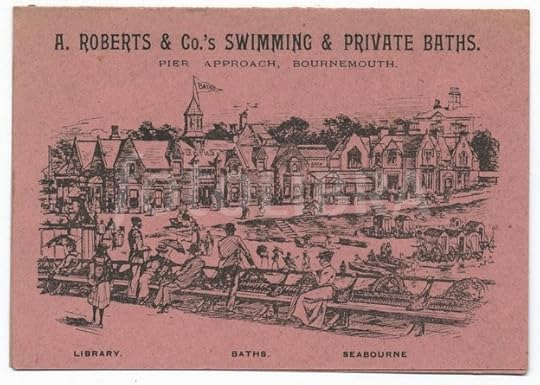

My neighbour has three young girls and every Saturday morning, the family set off to the local pool for swimming lessons. It makes sense. We don’t live near the sea, but swimming is an invaluable skill for children to learn. The idea of the swimming pool as we know it originated in the 19th century – but their original purpose is perhaps unexpected because the very first public baths came about because of cholera – or rather to prevent it.

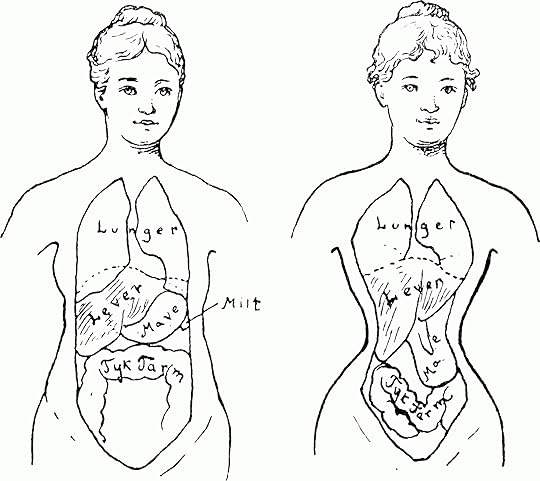

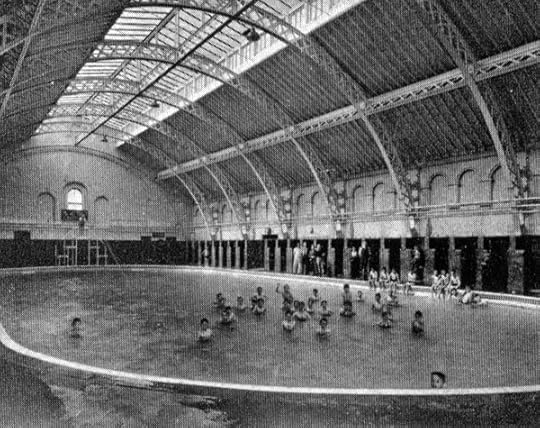

An original Victorian swimming pool

An original Victorian swimming pool

Shortly before Victoria came the throne, in 1832 an outbreak of cholera killed hundreds of thousands of people. This was at a time when few ordinary people had a bathroom to keep clean in, and the poor lacked even basic facilitates such as a “copper” to boil water to wash their clothes. At the time, no one knew how cholera spread but most people believed that boiling bedding and clothing went some way to protecting them – and remember at this time many people relied on second-hand clothing and bed-sharing. Kitty Wilkinson

Kitty Wilkinson

"Saint of the slums"

Kitty Wilkinson and her husband Tom lived in a poor street in Liverpool. However, they were better off than most in that they owned a copper. In an effort to help her neighbours avoid cholera, and at personal risk to herself and her husband, she invited her neighbours to use her wash facilities (for a minimal payment to cover the cost of coal). The story of Kitty’s generosity spread and the press took up her story. She became labelled “the saint of the slums”, but more than that the idea took hold of providing public facilities for washing. A movement a Public Wash and Bathhouse movement was born.

Ten years later, in 1842, the first public bathhouse was opened – in Liverpool, with Kitty and Tom Wilkinson as curators. By 1846 a legal act passed through Parliament which empowered local authorities to build equivalent facilities, paid for out of local taxes. The first baths to open in London in 1846, in Glass House Yard, then Goulston Square in Whitechapel – serving some of the most deprived slums. The baths had male and female areas, and were subdivided again by price. There were spacious baths supplied with hot water for those with cash to spare, or the economy version which was cramped – and you guessed it – supplied with cold water.

In addition, and cheapest of all, was the public plunge pool. This cost just 1/2 d and was within the reach of young working boys. No soap was allowed, it being said a brisk rub down was adequate for a basic bath. The same unfiltered water remained in the pool for a full week (!) during which silt and dirt accumulated. But the boys who used these plunge pools weren’t all that bothered about cleanliness- because splashing around in the water with their friends they had fun. They larked around and spent rare moments of fun playing together. Getting clean was a secondary consideration to them. Bradford, Manningham Pool

Bradford, Manningham Pool

But other bath users were less than impressed and bigger plunger pools were built and the boys sidelined to smaller pools. But over time, the idea of having fun in water stuck and it was the baths that suffered and fell out of use, leaving the plunge pools to be enjoyed as “swimming pools”.

The first few swimming pools were relatively small, but as their popularly grew, they became larger and larger – and recognised as the forerunner of the swimming pools my neighbour visits every Saturday morning.

An original Victorian swimming pool

An original Victorian swimming poolShortly before Victoria came the throne, in 1832 an outbreak of cholera killed hundreds of thousands of people. This was at a time when few ordinary people had a bathroom to keep clean in, and the poor lacked even basic facilitates such as a “copper” to boil water to wash their clothes. At the time, no one knew how cholera spread but most people believed that boiling bedding and clothing went some way to protecting them – and remember at this time many people relied on second-hand clothing and bed-sharing.

Kitty Wilkinson

Kitty Wilkinson"Saint of the slums"

Kitty Wilkinson and her husband Tom lived in a poor street in Liverpool. However, they were better off than most in that they owned a copper. In an effort to help her neighbours avoid cholera, and at personal risk to herself and her husband, she invited her neighbours to use her wash facilities (for a minimal payment to cover the cost of coal). The story of Kitty’s generosity spread and the press took up her story. She became labelled “the saint of the slums”, but more than that the idea took hold of providing public facilities for washing. A movement a Public Wash and Bathhouse movement was born.

Ten years later, in 1842, the first public bathhouse was opened – in Liverpool, with Kitty and Tom Wilkinson as curators. By 1846 a legal act passed through Parliament which empowered local authorities to build equivalent facilities, paid for out of local taxes. The first baths to open in London in 1846, in Glass House Yard, then Goulston Square in Whitechapel – serving some of the most deprived slums. The baths had male and female areas, and were subdivided again by price. There were spacious baths supplied with hot water for those with cash to spare, or the economy version which was cramped – and you guessed it – supplied with cold water.

In addition, and cheapest of all, was the public plunge pool. This cost just 1/2 d and was within the reach of young working boys. No soap was allowed, it being said a brisk rub down was adequate for a basic bath. The same unfiltered water remained in the pool for a full week (!) during which silt and dirt accumulated. But the boys who used these plunge pools weren’t all that bothered about cleanliness- because splashing around in the water with their friends they had fun. They larked around and spent rare moments of fun playing together. Getting clean was a secondary consideration to them.

Bradford, Manningham Pool

Bradford, Manningham PoolBut other bath users were less than impressed and bigger plunger pools were built and the boys sidelined to smaller pools. But over time, the idea of having fun in water stuck and it was the baths that suffered and fell out of use, leaving the plunge pools to be enjoyed as “swimming pools”.

The first few swimming pools were relatively small, but as their popularly grew, they became larger and larger – and recognised as the forerunner of the swimming pools my neighbour visits every Saturday morning.

Published on April 26, 2015 12:14

April 19, 2015

The Stand-Up Wash: Keeping Clean in Victorian Britain

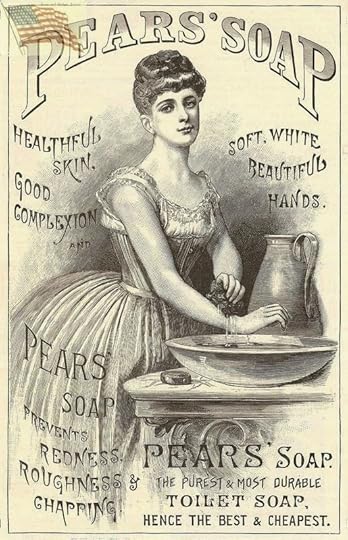

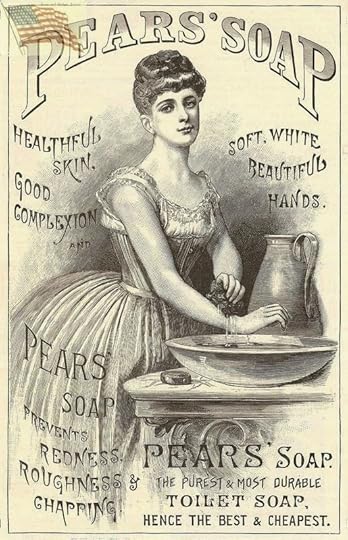

When is a bar of soap like a joint of beef? Answer: When they cost the same.

Money for Old SoapIn Victorian England, a four-ounce bar of soap cost roughly the same as a joint of meat. For poorer households, faced with a choice between cleanliness or eating, naturally they looked for other ways to keep clean.

Indeed, since Victorian soap worked best with hot water (it didn’t dissolve or lather well in cold water), this involved additional time, money, and effort, to bring coppers of water to the boil. So all in all, washing with soap and water was not a realistic daily habit for many people.

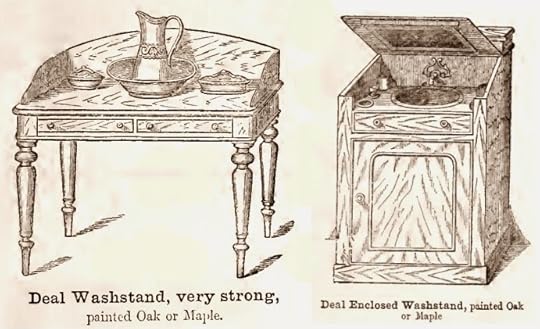

Stand and DeliverThis doesn’t mean people neglected their personal hygiene. Full immersion baths were a rarity but most peoples’ daily routine started with a stand-up wash. For most this was done in the bedroom, although some female servants may have done their ablutions at the kitchen sink – made more conducive by the heat from the range.

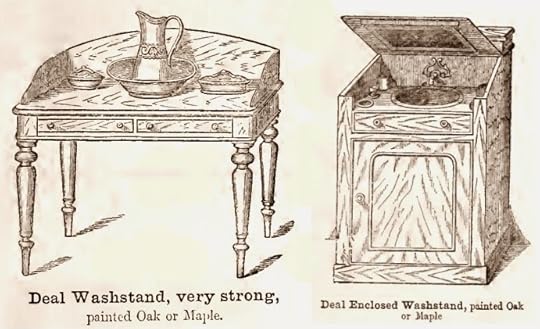

A washstand was a standard piece of furniture in many Victorian bedrooms. On it stood a jug of cold water, a bowl, and a clean rage. The person washed first thing in the morning, immediately after rising. Most bedrooms were cold, chilly places, especially as the sash windows were kept open at the top and bottom (regardless of weather) to allow good ventilation and reduce the risk of illness. This meant in winter most people kept their nightclothes and worked on one part of their body at a time.

The art of a stand-up wash was to pour water into the bowl. The soaked flannel was then rubbed on each part of the body, and rinsed. Once the water became too soiled it was discarded into the slop bucket and more water poured into the bowl. Working methodically, all of the body was cleaned, with each part being scrubbed and dried before moving onto the next bit.

Pore TheoryIn more affluent households, a servant rose before the rest of the house. She boiled a kettle, to provide hot water for her employers’ morning ablutions. Washing regularly was a Victorian phenomenon since previous to this it was believed that the skin’s pores allowed entry to disease. Since washing opened the pores, this made the activity potentially foolhardy for those wishing to keep well. Part of the change of attitude came about because the Victorians believed that oxygen passed into the body through the pores, and so clearing away dirt aided this process.

Dress ProtectorsBefore the advent of anti-perspirants the armpits of garments could be ruined by perspiration. To combat this, ladies who wished to protect expensive gowns used dress-protectors. These were small detachable pads which fitted into the armpit. These could then be removed and washed separately, having done their job of shielding expensive fabrics from sweat.

And finally, one home remedy to reduce the unpleasant odour associated with sweaty armpits was a wipe over with vinegar. In theory this might help kill the bacteria that created the worst smells – but the trade of was that it left you smelling like a fish and chip shop.

Money for Old SoapIn Victorian England, a four-ounce bar of soap cost roughly the same as a joint of meat. For poorer households, faced with a choice between cleanliness or eating, naturally they looked for other ways to keep clean.

Indeed, since Victorian soap worked best with hot water (it didn’t dissolve or lather well in cold water), this involved additional time, money, and effort, to bring coppers of water to the boil. So all in all, washing with soap and water was not a realistic daily habit for many people.

Stand and DeliverThis doesn’t mean people neglected their personal hygiene. Full immersion baths were a rarity but most peoples’ daily routine started with a stand-up wash. For most this was done in the bedroom, although some female servants may have done their ablutions at the kitchen sink – made more conducive by the heat from the range.

A washstand was a standard piece of furniture in many Victorian bedrooms. On it stood a jug of cold water, a bowl, and a clean rage. The person washed first thing in the morning, immediately after rising. Most bedrooms were cold, chilly places, especially as the sash windows were kept open at the top and bottom (regardless of weather) to allow good ventilation and reduce the risk of illness. This meant in winter most people kept their nightclothes and worked on one part of their body at a time.

The art of a stand-up wash was to pour water into the bowl. The soaked flannel was then rubbed on each part of the body, and rinsed. Once the water became too soiled it was discarded into the slop bucket and more water poured into the bowl. Working methodically, all of the body was cleaned, with each part being scrubbed and dried before moving onto the next bit.

Pore TheoryIn more affluent households, a servant rose before the rest of the house. She boiled a kettle, to provide hot water for her employers’ morning ablutions. Washing regularly was a Victorian phenomenon since previous to this it was believed that the skin’s pores allowed entry to disease. Since washing opened the pores, this made the activity potentially foolhardy for those wishing to keep well. Part of the change of attitude came about because the Victorians believed that oxygen passed into the body through the pores, and so clearing away dirt aided this process.

Dress ProtectorsBefore the advent of anti-perspirants the armpits of garments could be ruined by perspiration. To combat this, ladies who wished to protect expensive gowns used dress-protectors. These were small detachable pads which fitted into the armpit. These could then be removed and washed separately, having done their job of shielding expensive fabrics from sweat.

And finally, one home remedy to reduce the unpleasant odour associated with sweaty armpits was a wipe over with vinegar. In theory this might help kill the bacteria that created the worst smells – but the trade of was that it left you smelling like a fish and chip shop.

Published on April 19, 2015 11:26

April 13, 2015

The Victorian Knocker-Upper

Having trouble getting up in the morning? Having just had a fantastic few days away, I’m struggling to get back into routine. What could be more of a rude awakening than a hateful alarm clock?

But what if there were no alarm clocks? Bliss, might be your response. But what if keeping a roof over your head and feeding your family meant getting up on time. And in Victorian times that often might rising in the pitch black of night, without even the dawning sun to alert you to the time. The problem was that in the 19th century a pocket watch or clock were expensive items to purchase, and something that many working class people simply couldn’t afford. After the industrial revolution when people did shift work in factories, the problem of getting up on time was even more acute.

But as is so often the case, where there’s a need someone steps in to supply demand. Enter the “knocker-upper”. This enterprising individual invested money in a timepiece, and then armed with a long pole and a lantern, wandered the streets at night to alert his customers when it was time to rise. The long pole was used to tap on first floor or hard to reach windows, with some knocker-uppers seemingly using a peashooter for the same purpose. A female knocker-upper using a pea-shooterA typical fee was one penny a month, and for that the knocker-up would be there outside their window at the appointed time to tap on the windowpane with the end of his long cane. The conscientious knocker-up gave an undertaking not to leave until the occupant had proved they were awake.

A female knocker-upper using a pea-shooterA typical fee was one penny a month, and for that the knocker-up would be there outside their window at the appointed time to tap on the windowpane with the end of his long cane. The conscientious knocker-up gave an undertaking not to leave until the occupant had proved they were awake.

And if you think this sounds an unlikely way to make a living, consider how many people needed to get up early. In Baldock, Hertfordshire, had a population of around 2,000 people, and many of the workers were employed by the railway and brewing industry – which meant shift work and early starts. Indeed, there were not one but three local breweries, that all employed draymen whose day started at 3 am so there was plenty of work for a knocker up, who went to bed once everyone else was up.

Knocker-upper continued to do their duty through to the 1920s, indeed, the last professional knocker-upper turned in his long pole in the 1950s in Manchester.

All in all, perhaps my 7.15am start isn’t so bad after all…

But what if there were no alarm clocks? Bliss, might be your response. But what if keeping a roof over your head and feeding your family meant getting up on time. And in Victorian times that often might rising in the pitch black of night, without even the dawning sun to alert you to the time. The problem was that in the 19th century a pocket watch or clock were expensive items to purchase, and something that many working class people simply couldn’t afford. After the industrial revolution when people did shift work in factories, the problem of getting up on time was even more acute.

But as is so often the case, where there’s a need someone steps in to supply demand. Enter the “knocker-upper”. This enterprising individual invested money in a timepiece, and then armed with a long pole and a lantern, wandered the streets at night to alert his customers when it was time to rise. The long pole was used to tap on first floor or hard to reach windows, with some knocker-uppers seemingly using a peashooter for the same purpose.

A female knocker-upper using a pea-shooterA typical fee was one penny a month, and for that the knocker-up would be there outside their window at the appointed time to tap on the windowpane with the end of his long cane. The conscientious knocker-up gave an undertaking not to leave until the occupant had proved they were awake.

A female knocker-upper using a pea-shooterA typical fee was one penny a month, and for that the knocker-up would be there outside their window at the appointed time to tap on the windowpane with the end of his long cane. The conscientious knocker-up gave an undertaking not to leave until the occupant had proved they were awake. And if you think this sounds an unlikely way to make a living, consider how many people needed to get up early. In Baldock, Hertfordshire, had a population of around 2,000 people, and many of the workers were employed by the railway and brewing industry – which meant shift work and early starts. Indeed, there were not one but three local breweries, that all employed draymen whose day started at 3 am so there was plenty of work for a knocker up, who went to bed once everyone else was up.

Knocker-upper continued to do their duty through to the 1920s, indeed, the last professional knocker-upper turned in his long pole in the 1950s in Manchester.

All in all, perhaps my 7.15am start isn’t so bad after all…

Published on April 13, 2015 07:19

April 5, 2015

Traditions and Superstitions: New Clothing at Easter

Happy Easter! A chocolate egg bigger than my head – that’s what hubs gave me this Easter. He knows the way to my heart! Aside from the importance of Easter as a religious festival, it is also associated with chicks, chocolate, and in previous century….new clothes.

Traditionally, Easter was linked to the wearing of new clothes. Although this was also linked to other times of the year such as New Year and Christmas day, with its symbolism of renewal and rebirth, Easter was a key time to start afresh with new garments.

This tradition was mentioned in 1662 when Samuel Pepys wrote in his dairy about getting new clothes for his wife “against Easter”. Previous to this, Shakespeare hints at the importance in Romeo and Juliet, 1597, when Mercutio asks, “Didst though not fall out with a tailor for wearing his new doublet before Easter?”

Apart from anything else, it seems one penalty if you didn’t respect this superstition was that you ran the risk of being fouled upon by a bird. “It is deemed essential by many people to wear some new article of dress, if only a pair of gloves or a new ribbon; for not to do so is considered unlucky; and the birds will be angry with you.” Writings from 1911

This is borne out by Burne, writing in 1883“…he used to look out anxiously for rooks on Easter Day, and run to shelter if he heard on cawing, in spite of his mother’s habitual care to provide each of her family with some new garment for Easter wearing.”

The wearing of new clothes on Easter Sunday, also ties into to other superstitions regarding garments. There was a strong superstition that to be lucky, new clothes should first be worn to church for a sort of “blessing”. The consequence was to call bad luck upon your head. “You must be careful not to put on any new article of clothing for the first time on a Saturday, …or some severe punishment will ensue. One person put on his new boots on a Saturday, and on Monday broke his arm.“Jefferies. 1889

But if you couldn’t afford new, but bought second hand clothes, there was a way to counteract any lingering back luck. If you bought a garment which contained money in a pocket, this ensured prosperity for the rest of the year. Seemingly those selling second hand clothes cottoned on fast and learnt that simply by placing a small coin in the pocket they could inflate the price of the garment for sale!

Traditionally, Easter was linked to the wearing of new clothes. Although this was also linked to other times of the year such as New Year and Christmas day, with its symbolism of renewal and rebirth, Easter was a key time to start afresh with new garments.

This tradition was mentioned in 1662 when Samuel Pepys wrote in his dairy about getting new clothes for his wife “against Easter”. Previous to this, Shakespeare hints at the importance in Romeo and Juliet, 1597, when Mercutio asks, “Didst though not fall out with a tailor for wearing his new doublet before Easter?”

Apart from anything else, it seems one penalty if you didn’t respect this superstition was that you ran the risk of being fouled upon by a bird. “It is deemed essential by many people to wear some new article of dress, if only a pair of gloves or a new ribbon; for not to do so is considered unlucky; and the birds will be angry with you.” Writings from 1911

This is borne out by Burne, writing in 1883“…he used to look out anxiously for rooks on Easter Day, and run to shelter if he heard on cawing, in spite of his mother’s habitual care to provide each of her family with some new garment for Easter wearing.”

The wearing of new clothes on Easter Sunday, also ties into to other superstitions regarding garments. There was a strong superstition that to be lucky, new clothes should first be worn to church for a sort of “blessing”. The consequence was to call bad luck upon your head. “You must be careful not to put on any new article of clothing for the first time on a Saturday, …or some severe punishment will ensue. One person put on his new boots on a Saturday, and on Monday broke his arm.“Jefferies. 1889

But if you couldn’t afford new, but bought second hand clothes, there was a way to counteract any lingering back luck. If you bought a garment which contained money in a pocket, this ensured prosperity for the rest of the year. Seemingly those selling second hand clothes cottoned on fast and learnt that simply by placing a small coin in the pocket they could inflate the price of the garment for sale!

Published on April 05, 2015 11:06

March 29, 2015

The Trials of Buying an Owl in Victorian London

Long story short, today I happened upon a copy of “A London Year” [*] a compilation of diary and journal entries reflecting London life in yester year. It seemed natural to turn to today’s date, curious as to the entry. It turned out to be a lively tale of one-up-man ship (or reverse snobbery – I’ve yet to decide) about owls.

The journal entry dates from 1881 and was made by a gentleman with the grand name of Mountstuart Grant Duff. This day 134-years ago, Duff dined at his club, the Athenaeum, with two friends. He recounts a conversation whereby one friend claimed you could buy anything and everything in London.

Determined to be underwhelmed the other friends reply was: “Really? Well not everything. I wanted to buy an owl the other day …and I had to send to the country for that.”“Had you? Then come with me to Leadenhall market, to-morrow.”

The following day the two men went to Leadenhall and walked up to a livestock stall. Inquiries were made of the stallholder, and when asked if he had owls for sale the man replied:“No sir, not today, this is Wednesday. Tuesday and Fridays are the days for owls.”

All of which left me slightly worried about where the owls came from and what they were used for. Hey ho. Anyway, broadening out the topic let’s take a look at some of the folklore associated with owls. Indeed, in popular culture of the day (late Victorian times) many people actively disliked the bird as they thought it an omen of death.

“When a screech-owl is heard crying near a house, it is an indication of death on the premises. When a barn-owl alights on a house, hoots and then flies over it, an inmate will die within the year.” Trevelyn (writing slightly later in 1909)

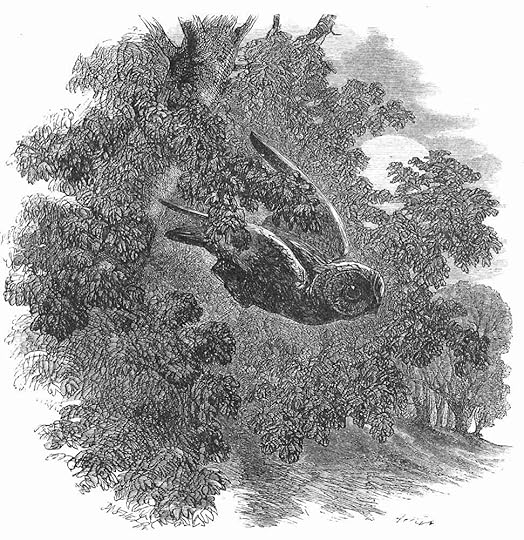

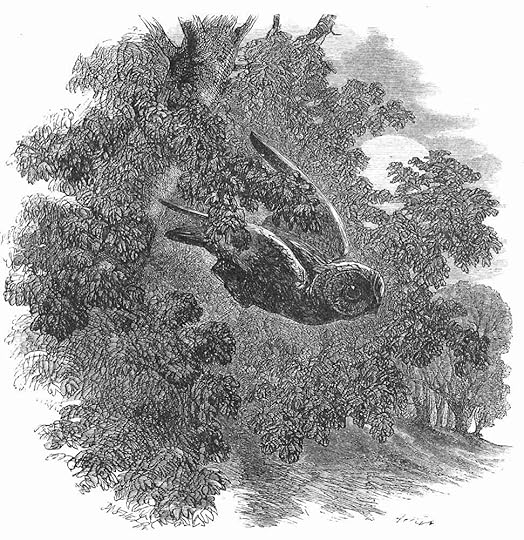

And an owl was also a bad omen for livestock“…a cow will give bloody milk if it is frightened by an owl, and will fall sick and die if touched by it.” Folklore 1874 Night owl - etching by Harrison Weir

Night owl - etching by Harrison Weir

Suspicion of owls had a long history, as recorded by Chaucer’s Parliament of Fowls written around 1380:

“The oule eke, that of deth the bode bringeth [sic]”

Indeed, in India it is an insult to call a person an “owl” because it implies they bring bad luck with them. One can only speculate why the poor owl came by such a bad reputation, perhaps it was because of their silent flight and that eerie nocturnal cry.

And finally, it seems there was no term recorded for a group of owls until the 1950s! The credit for the most commonly used collective ‘a parliament of owls' was first used by CS Lewis in The Chronicles of Narnia. It seems CS Lewis adapted the expression from Chaucer’s poem, referenced above, called a Parliament of Fowls. The Narnia books were so widely read that Lewis' term seeped into popular usage.

[*] A LondonYear. Compiled by Elborough & Rennison. Publishers: Francis Lincoln Limited.

The journal entry dates from 1881 and was made by a gentleman with the grand name of Mountstuart Grant Duff. This day 134-years ago, Duff dined at his club, the Athenaeum, with two friends. He recounts a conversation whereby one friend claimed you could buy anything and everything in London.

Determined to be underwhelmed the other friends reply was: “Really? Well not everything. I wanted to buy an owl the other day …and I had to send to the country for that.”“Had you? Then come with me to Leadenhall market, to-morrow.”

The following day the two men went to Leadenhall and walked up to a livestock stall. Inquiries were made of the stallholder, and when asked if he had owls for sale the man replied:“No sir, not today, this is Wednesday. Tuesday and Fridays are the days for owls.”

All of which left me slightly worried about where the owls came from and what they were used for. Hey ho. Anyway, broadening out the topic let’s take a look at some of the folklore associated with owls. Indeed, in popular culture of the day (late Victorian times) many people actively disliked the bird as they thought it an omen of death.

“When a screech-owl is heard crying near a house, it is an indication of death on the premises. When a barn-owl alights on a house, hoots and then flies over it, an inmate will die within the year.” Trevelyn (writing slightly later in 1909)

And an owl was also a bad omen for livestock“…a cow will give bloody milk if it is frightened by an owl, and will fall sick and die if touched by it.” Folklore 1874

Night owl - etching by Harrison Weir

Night owl - etching by Harrison WeirSuspicion of owls had a long history, as recorded by Chaucer’s Parliament of Fowls written around 1380:

“The oule eke, that of deth the bode bringeth [sic]”

Indeed, in India it is an insult to call a person an “owl” because it implies they bring bad luck with them. One can only speculate why the poor owl came by such a bad reputation, perhaps it was because of their silent flight and that eerie nocturnal cry.

And finally, it seems there was no term recorded for a group of owls until the 1950s! The credit for the most commonly used collective ‘a parliament of owls' was first used by CS Lewis in The Chronicles of Narnia. It seems CS Lewis adapted the expression from Chaucer’s poem, referenced above, called a Parliament of Fowls. The Narnia books were so widely read that Lewis' term seeped into popular usage.

[*] A LondonYear. Compiled by Elborough & Rennison. Publishers: Francis Lincoln Limited.

Published on March 29, 2015 12:02

March 22, 2015

Rags to Riches: The true story of Elizabeth and Maria Gunning

In 18th century Georgian high society, a well to-do-lady aspired to catch herself a titled husband. With fierce competition from other, equally ambitious debutantes to attract the eye of an eligible bachelor, interlopers were discouraged and frozen out of society. Which makes the story of the Gunning sisters, Maria and Elizabeth all the more unusual.

Elizabeth Gunning, after her marriage The two sisters were genteel nobodies: the daughters of an Irishman with neither money nor connections, and yet they did have one attribute in abundance – they were great beauties. When they were old enough, they worked in a Dublin theatre to help boost the family income. This was a potentially disastrous move for their reputations because most actresses were considered harlots. However, they survived the risk and were invited to a ball at Dublin castle.The story goes that they had no money for ball gowns. But the theatre manager, Tom Sheridan, came to the rescue and leant them the Juliette and Lady Macbeth costumes to wear. Once at the ball they made such an impression on the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland that he granted their mother a reasonable pension.

Elizabeth Gunning, after her marriage The two sisters were genteel nobodies: the daughters of an Irishman with neither money nor connections, and yet they did have one attribute in abundance – they were great beauties. When they were old enough, they worked in a Dublin theatre to help boost the family income. This was a potentially disastrous move for their reputations because most actresses were considered harlots. However, they survived the risk and were invited to a ball at Dublin castle.The story goes that they had no money for ball gowns. But the theatre manager, Tom Sheridan, came to the rescue and leant them the Juliette and Lady Macbeth costumes to wear. Once at the ball they made such an impression on the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland that he granted their mother a reasonable pension.

Elizabeth Gunning

Elizabeth GunningMrs Gunning used the money to take her daughters to England, and their house in Huntingdon. They attended local assemblies, and created such a sensation that word of them spread ahead to London. With a reputation akin to that of a modern celebrity, the sisters entered London society feted as beauties – and took it by storm. This was unusual for the day, where manners, breeding, grace, and connections dictated how ‘beautiful’ a lady was. But more than that, they did the unthinkable and completed a rags to riches story by snagging aristocrats for husbands.

Elizabeth again

Elizabeth againIn 1752, after a whirlwind romance, Elizabeth married the Duke of Hamilton, and went on to bear three children. When he died in 1758, she still attracted noble interest and remarried a Marques, who then inherited a dukedom. Elizabeth was a favourite at court and became a lady for the bedchamber for Queen Charlotte, during George III’s reign. She died at the age of 57, quietly in her bed.

Maria Gunning

Maria GunningHer sister, Maria, was more controversial. She was renowned as being tactless, but for some reason this amused the haut ton and it added to her popularity. Also in 1752, Maria married the Earl of Coventry, but it seems he quickly tried to clip her wings. Whilst on honeymoon in Paris, he reportedly publically wiped her face with a handkerchief, when she wore rouge at dinner after he had forbidden it.

Maria, Countess of Coventry

Maria, Countess of CoventryHowever, his aversion to Maria wearing cosmetics was strangely prophetic. A woman famed for beauty, she did everything she could to preserve that image. This meant wearing the heavy makeup that was fashionable in some quarters. But unfortunately that makeup contained lead and arsenic which slowly poisoned her. She was caught in a vicious circle, because the symptoms of poisoning included skin breakouts and redness, which undoubtedly meant she applied yet thicker layers of cosmetics.

Maria's mirror.

Maria's mirror.It was this very mirror Maria looked in to apply her makeup

Her continued use of makeup signed Maria’s death warrant and she died at the tender age of 27. A rags to riches story, which unlike Cinderella has a sad ending.

Published on March 22, 2015 13:38

March 15, 2015

Mothering Sunday or Mother’s Day?

Here in the UK, today is Mothering Sunday. I know in the US, Mother’s Day happens on a different date, but until now I hadn’t realised the subtle difference between the two.

The Origins of Mother’s DayWhereas Mothering Sunday has its roots back in the 17thcentury, Mother's Day was first suggested in 1907 by a schoolteacher from Philadelphia. Apparently, Miss Anna Jarvis wanted to honour her own mother and by extension mothers everywhere. After a vigorous campaign to get the day officially recognized, Congress did so in 1913 – with the date set as the second Sunday in May.

In Britain people latched onto the American idea and it gained the support of many influential people including the Queen. Mother's Day was set in August, however, enthusiasm for the event faltered and it quickly fell out of vogue.

Mother’s Day vs Mothering SundayIn the UK there was an upsurge in interest around the time of the Second World War, because of American servicemen stationed on these shores. This time commercialism started to rear its head and the day gained more momentum, but got tangled up with the quasi-religious celebration of Mother’s in lent (Mothering Sunday). In the end, under the influence of the Church of England, Mothering Sunday won out – and is the day we celebrate to this day in the UK.

The 17th Century and Mothering SundayWhich brings us back to this weekend. Traditionally, Mothering Sunday is said to have come about when young people (usually young women who had gone into service) tried to get back home to share a family meal. The custom seems well established by the mid-17thcentury. Every mid-Lent Sunday is a great day in Worcester, when all the children and godchildren meet at the head and chief of the family and have a feast. The call it Mothering-day. Richard Symonds 1644

The date for this happy reunion was the fourth Sunday in Lent, known at Mid-Lent Sunday. It seems the tradition started in the west of England, as spread over time to the whole of the country. In the same way you have turkey at Thanksgiving, so special foods became associated with the day. These include veal, rice pudding (!), frumenty, and simnel cake. Speaking of which – take a look at what I had for breakfast today, courtesy of my eldest son…..There’s a lot to be said for Mothering Sunday!

The Origins of Mother’s DayWhereas Mothering Sunday has its roots back in the 17thcentury, Mother's Day was first suggested in 1907 by a schoolteacher from Philadelphia. Apparently, Miss Anna Jarvis wanted to honour her own mother and by extension mothers everywhere. After a vigorous campaign to get the day officially recognized, Congress did so in 1913 – with the date set as the second Sunday in May.

In Britain people latched onto the American idea and it gained the support of many influential people including the Queen. Mother's Day was set in August, however, enthusiasm for the event faltered and it quickly fell out of vogue.

Mother’s Day vs Mothering SundayIn the UK there was an upsurge in interest around the time of the Second World War, because of American servicemen stationed on these shores. This time commercialism started to rear its head and the day gained more momentum, but got tangled up with the quasi-religious celebration of Mother’s in lent (Mothering Sunday). In the end, under the influence of the Church of England, Mothering Sunday won out – and is the day we celebrate to this day in the UK.

The 17th Century and Mothering SundayWhich brings us back to this weekend. Traditionally, Mothering Sunday is said to have come about when young people (usually young women who had gone into service) tried to get back home to share a family meal. The custom seems well established by the mid-17thcentury. Every mid-Lent Sunday is a great day in Worcester, when all the children and godchildren meet at the head and chief of the family and have a feast. The call it Mothering-day. Richard Symonds 1644

The date for this happy reunion was the fourth Sunday in Lent, known at Mid-Lent Sunday. It seems the tradition started in the west of England, as spread over time to the whole of the country. In the same way you have turkey at Thanksgiving, so special foods became associated with the day. These include veal, rice pudding (!), frumenty, and simnel cake. Speaking of which – take a look at what I had for breakfast today, courtesy of my eldest son…..There’s a lot to be said for Mothering Sunday!

Published on March 15, 2015 05:01

March 8, 2015

A Mutation of Thrushes

This weekend there’s a hint of spring in the air. The sun is shining and birds are singing – albeit from bare branches. So in this series of posts about unusual collective terms, it seemed appropriate to write about birds.

A song thrushA Mutation of Thrushes

A song thrushA Mutation of Thrushes

With their fawn-coloured speckled breasts, thrushes are such pretty birds. It seems odd then that the correct term for a group of thrushes is a ‘mutation’. This term goes back to a belief held in ancient Roman and Greek empires, which was still current in the middle ages – and even later. “It’s a recognized fact amongst naturalists that thrushes acquire new legs, and cast of the old one when about ten years old.”Letter to Science Gossip, published in the 1800s.

Perhaps it was this rather strange idea, or that thrushes moult and adopt thicker feathers for winter, which inspired the intriguing ‘mutation of thrushes’.

A wren

A wren

A Herd of Wrens

The collective term for that jolly little bird, the wren, is altogether more evocative of larger animals. However, ‘A herd of wrens’ is most likely derived from an ancient fable that was known to Aristotle and Pliny.

In the story the birds hold a meeting to decide who should be king of all the birds. They all agree the winner will be the bird who can fly the highest. The eagle flies much higher than all the others and jubilantly shouts, “I am king”, at which point the wren who had stowed away beneath his wing, pops out and flutters higher. The birds then agree that despite his small size, the wren’s ingenuity and daring do indeed make him worthy of the title- king of the birds.

The word ‘herd’ in the medieval context, was derived from the term for a group of male red deer – those considered king of the deer and most prized by royalty.

A turtle dove

A turtle dove

A Pitying of Turtle Doves

And finally, a pitying of turtle doves. This term first appears in a 15th century manuscript and relates to the association between turtle doves and sorrow. In turn this probably came about because of the birds’ plaintive “Woo-woo” cry.

Prior to this, in the 14th century, the Book of St Albans refers to a ‘dule of doves’ – where the word dule came from the Latin, dolere, to mean sorry of grief.

However, if you’re a glass half full type of person, there is another term – ‘a truelove of turtle doves’, which reflects that these birds chose one mate and remain devoted to each other for life.

A song thrushA Mutation of Thrushes

A song thrushA Mutation of Thrushes

With their fawn-coloured speckled breasts, thrushes are such pretty birds. It seems odd then that the correct term for a group of thrushes is a ‘mutation’. This term goes back to a belief held in ancient Roman and Greek empires, which was still current in the middle ages – and even later. “It’s a recognized fact amongst naturalists that thrushes acquire new legs, and cast of the old one when about ten years old.”Letter to Science Gossip, published in the 1800s.

Perhaps it was this rather strange idea, or that thrushes moult and adopt thicker feathers for winter, which inspired the intriguing ‘mutation of thrushes’.

A wren

A wrenA Herd of Wrens

The collective term for that jolly little bird, the wren, is altogether more evocative of larger animals. However, ‘A herd of wrens’ is most likely derived from an ancient fable that was known to Aristotle and Pliny.

In the story the birds hold a meeting to decide who should be king of all the birds. They all agree the winner will be the bird who can fly the highest. The eagle flies much higher than all the others and jubilantly shouts, “I am king”, at which point the wren who had stowed away beneath his wing, pops out and flutters higher. The birds then agree that despite his small size, the wren’s ingenuity and daring do indeed make him worthy of the title- king of the birds.

The word ‘herd’ in the medieval context, was derived from the term for a group of male red deer – those considered king of the deer and most prized by royalty.

A turtle dove

A turtle doveA Pitying of Turtle Doves

And finally, a pitying of turtle doves. This term first appears in a 15th century manuscript and relates to the association between turtle doves and sorrow. In turn this probably came about because of the birds’ plaintive “Woo-woo” cry.

Prior to this, in the 14th century, the Book of St Albans refers to a ‘dule of doves’ – where the word dule came from the Latin, dolere, to mean sorry of grief.

However, if you’re a glass half full type of person, there is another term – ‘a truelove of turtle doves’, which reflects that these birds chose one mate and remain devoted to each other for life.

Published on March 08, 2015 04:54

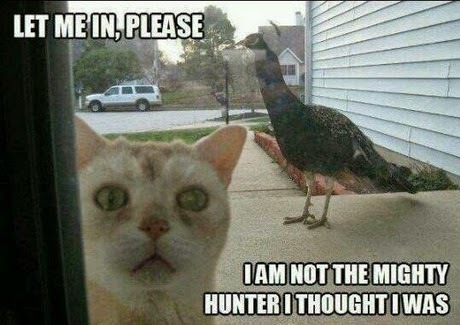

'Familiar Felines.'

Following on from last weeks Halloween posting, today's blog post looks at the unwanted image of cats as the witches familiar - from the Norse Goddess Freya to lonely women in the middle ages.

The full Following on from last weeks Halloween posting, today's blog post looks at the unwanted image of cats as the witches familiar - from the Norse Goddess Freya to lonely women in the middle ages.

The full post can found at:

http://graceelliot-author.blogspot.com

...more

The full Following on from last weeks Halloween posting, today's blog post looks at the unwanted image of cats as the witches familiar - from the Norse Goddess Freya to lonely women in the middle ages.

The full post can found at:

http://graceelliot-author.blogspot.com

...more

- Grace Elliot's profile

- 156 followers