Grace Elliot's Blog: 'Familiar Felines.' , page 2

March 13, 2016

Cat-egorizing Cats 19th Century Style

How do you organize cats?

Last week in How the Victorians went Wild for Cat Shows we looked at the popular 19thcentury pastime of visiting dog or cat shows. However, the organizers of cat shows had a problem that dog show organizers did not have, which was how to group the entries. With dogs it was relatively easy because they came in so many varied sizes and shapes or breeds. Cats – not so much. A tortoiseshell and white cat by Louis WainCat fancier Harrison Weir, arranged the very first cat show, which took place at Crystal Palace, July 16, 1871. His stated aim as organizer in “a labor of love to the feline race,” was to draw attention and therefore favor to: “The different breeds, colors, markings.”

A tortoiseshell and white cat by Louis WainCat fancier Harrison Weir, arranged the very first cat show, which took place at Crystal Palace, July 16, 1871. His stated aim as organizer in “a labor of love to the feline race,” was to draw attention and therefore favor to: “The different breeds, colors, markings.”

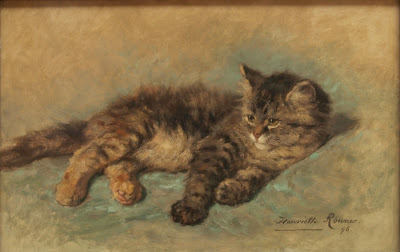

However, Weir had a problem because the existing description of cat breeds tended to dwell on distinctions that highlighted their weaknesses. One obvious solution was to arrange the cat classes by color. Gordon Stables, a man who was active in both the dog and cat show worlds, suggested categorizing cats into 13 groups. A tabby cat by Henriette Ronner KnipThese colors were:Tortoiseshell, tortoiseshell-and-white, Brow, blue, and silver tabbyRed, Red, red-and-white, tabbySpotted tabbyBlack-and-white, black, white, Unusual color and any other variety.

A tabby cat by Henriette Ronner KnipThese colors were:Tortoiseshell, tortoiseshell-and-white, Brow, blue, and silver tabbyRed, Red, red-and-white, tabbySpotted tabbyBlack-and-white, black, white, Unusual color and any other variety.

Stables asserted that color was actually key to the cats’ character, and that certain colors were more likely to have certain character traits. In effect he was trying to justify the color-grouped categories as being more significant than they really were.

He argued: “Properly speaking color is often the key to [the cats] characters…temper…and qualities as a hunter…and its power of endurance.” A black and white kitten by Henriette Ronner KnipThis is an interesting observation, because coat color does carry some associations in the modern age. For example, tortoiseshell cats are often described as “naughty torties” within vet clinics, because they have reputation for misbehaving.

A black and white kitten by Henriette Ronner KnipThis is an interesting observation, because coat color does carry some associations in the modern age. For example, tortoiseshell cats are often described as “naughty torties” within vet clinics, because they have reputation for misbehaving.

According to Stables:Tortoiseshells were “Good mothers and game as bull terriers”Black cats were “Noble and gentlemanly”White cats were “Far from brave…fond of society…gentle, and often delicate”And black-and-whites “Sometimes…did not trouble himself too much about his duties as a house-cat.”

Stables categories didn’t last long and soon went out of fashion. In the 1880s and 1890s Weir replaced them with not dissimilar groupings but broke them down into yet more colors, also long-haired or short-haired, age, and gender. However, he added one final category that was a bit of a showstopper. This was “Cats belonging to Working Men.” A blue Persian - in black and whiteThe latter category was put in place out of the notion that animal social standing mirrored that of humans, and it wouldn’t do to have working men getting ideas above their station. Incredibly, everyone seemed to go along with it, and in 1889, out of 511 entries, 102 were in the category Cats of Working Men.

A blue Persian - in black and whiteThe latter category was put in place out of the notion that animal social standing mirrored that of humans, and it wouldn’t do to have working men getting ideas above their station. Incredibly, everyone seemed to go along with it, and in 1889, out of 511 entries, 102 were in the category Cats of Working Men.

As the years passed, a greater study was made of the science of cat-breeding and specialist breed cat clubs sprang, such as the Siamese or the Abyssinian cat clubs, the Silver and Smoke Persian cat club or the Tortoiseshell society. However, rather than breeding to improve the cats, the main criteria for selecting animals to breed seemed to be rarity, with a cat with unusual colored eyes or a particularly striking coat commanding the most money.

But that was reckoning without the character of cats, which were perfectly capable of escaping and finding their own mate, much to the consternation of their own.

What are your experiences of different coat colors? Have you noticed distinctive personalities based on color or is it a load of bunkum?

Last week in How the Victorians went Wild for Cat Shows we looked at the popular 19thcentury pastime of visiting dog or cat shows. However, the organizers of cat shows had a problem that dog show organizers did not have, which was how to group the entries. With dogs it was relatively easy because they came in so many varied sizes and shapes or breeds. Cats – not so much.

A tortoiseshell and white cat by Louis WainCat fancier Harrison Weir, arranged the very first cat show, which took place at Crystal Palace, July 16, 1871. His stated aim as organizer in “a labor of love to the feline race,” was to draw attention and therefore favor to: “The different breeds, colors, markings.”

A tortoiseshell and white cat by Louis WainCat fancier Harrison Weir, arranged the very first cat show, which took place at Crystal Palace, July 16, 1871. His stated aim as organizer in “a labor of love to the feline race,” was to draw attention and therefore favor to: “The different breeds, colors, markings.” However, Weir had a problem because the existing description of cat breeds tended to dwell on distinctions that highlighted their weaknesses. One obvious solution was to arrange the cat classes by color. Gordon Stables, a man who was active in both the dog and cat show worlds, suggested categorizing cats into 13 groups.

A tabby cat by Henriette Ronner KnipThese colors were:Tortoiseshell, tortoiseshell-and-white, Brow, blue, and silver tabbyRed, Red, red-and-white, tabbySpotted tabbyBlack-and-white, black, white, Unusual color and any other variety.

A tabby cat by Henriette Ronner KnipThese colors were:Tortoiseshell, tortoiseshell-and-white, Brow, blue, and silver tabbyRed, Red, red-and-white, tabbySpotted tabbyBlack-and-white, black, white, Unusual color and any other variety. Stables asserted that color was actually key to the cats’ character, and that certain colors were more likely to have certain character traits. In effect he was trying to justify the color-grouped categories as being more significant than they really were.

He argued: “Properly speaking color is often the key to [the cats] characters…temper…and qualities as a hunter…and its power of endurance.”

A black and white kitten by Henriette Ronner KnipThis is an interesting observation, because coat color does carry some associations in the modern age. For example, tortoiseshell cats are often described as “naughty torties” within vet clinics, because they have reputation for misbehaving.

A black and white kitten by Henriette Ronner KnipThis is an interesting observation, because coat color does carry some associations in the modern age. For example, tortoiseshell cats are often described as “naughty torties” within vet clinics, because they have reputation for misbehaving. According to Stables:Tortoiseshells were “Good mothers and game as bull terriers”Black cats were “Noble and gentlemanly”White cats were “Far from brave…fond of society…gentle, and often delicate”And black-and-whites “Sometimes…did not trouble himself too much about his duties as a house-cat.”

Stables categories didn’t last long and soon went out of fashion. In the 1880s and 1890s Weir replaced them with not dissimilar groupings but broke them down into yet more colors, also long-haired or short-haired, age, and gender. However, he added one final category that was a bit of a showstopper. This was “Cats belonging to Working Men.”

A blue Persian - in black and whiteThe latter category was put in place out of the notion that animal social standing mirrored that of humans, and it wouldn’t do to have working men getting ideas above their station. Incredibly, everyone seemed to go along with it, and in 1889, out of 511 entries, 102 were in the category Cats of Working Men.

A blue Persian - in black and whiteThe latter category was put in place out of the notion that animal social standing mirrored that of humans, and it wouldn’t do to have working men getting ideas above their station. Incredibly, everyone seemed to go along with it, and in 1889, out of 511 entries, 102 were in the category Cats of Working Men. As the years passed, a greater study was made of the science of cat-breeding and specialist breed cat clubs sprang, such as the Siamese or the Abyssinian cat clubs, the Silver and Smoke Persian cat club or the Tortoiseshell society. However, rather than breeding to improve the cats, the main criteria for selecting animals to breed seemed to be rarity, with a cat with unusual colored eyes or a particularly striking coat commanding the most money.

But that was reckoning without the character of cats, which were perfectly capable of escaping and finding their own mate, much to the consternation of their own.

What are your experiences of different coat colors? Have you noticed distinctive personalities based on color or is it a load of bunkum?

Published on March 13, 2016 12:08

March 6, 2016

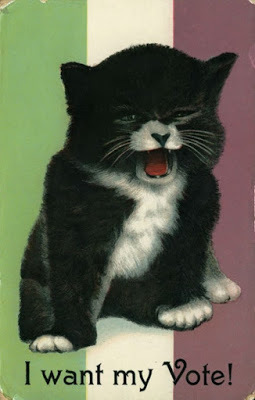

How the Victorians went Wild for Cat Shows

In the 19th century there was a mania for dog breeding and dog shows. Dogs proved to be ‘plastic’ when it came to manipulating their size, shape, and general appearance, which leant itself to the Victorian desire to control everything around them. Cats, however, were not so obliging

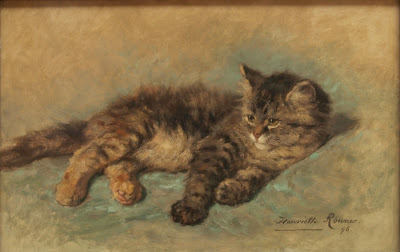

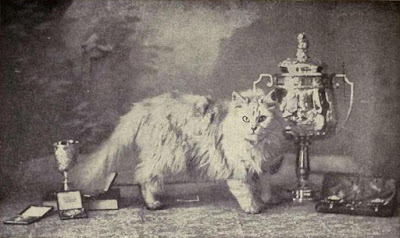

A prize-winning Persian catFor those ambitious cat owners who wished to exhibit their pet in a cat show and have other people appreciate them, their first problem was to devise categories within which to classify the cats. For dogs this was easy because there were distinct breeds ranging in size from a tiny Yorkshire terrier up to a giant Newfoundland. Not so for cats.

A prize-winning Persian catFor those ambitious cat owners who wished to exhibit their pet in a cat show and have other people appreciate them, their first problem was to devise categories within which to classify the cats. For dogs this was easy because there were distinct breeds ranging in size from a tiny Yorkshire terrier up to a giant Newfoundland. Not so for cats.

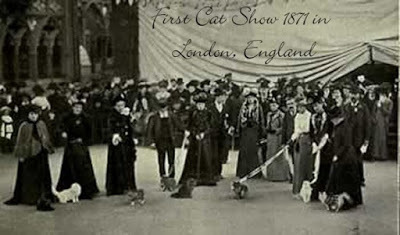

It was ever the bane of the Victorian pet keeper that cats defied their master’s (or mistresses – as cats were far more likely to be kept by women) wishes. Cats had a habit of breeding willy-nilly and behind their owner’s back, which made manipulating matings to produce a specific look all the more difficult. Indeed, Charles Darwin himself said as much in 1868. The first Crystal Palace cat show - 1871Darwin noted that people’s effort to alter the appearance of cat’s had done – “…nothing by methodical selection, and probably very little by unintentional selection…” except to save the cutest kittens and destroy adult cats that poached gamebirds.

The first Crystal Palace cat show - 1871Darwin noted that people’s effort to alter the appearance of cat’s had done – “…nothing by methodical selection, and probably very little by unintentional selection…” except to save the cutest kittens and destroy adult cats that poached gamebirds.

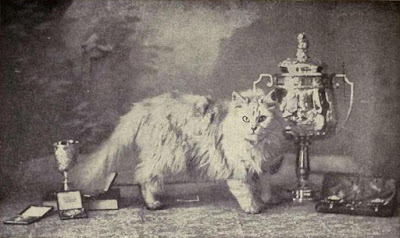

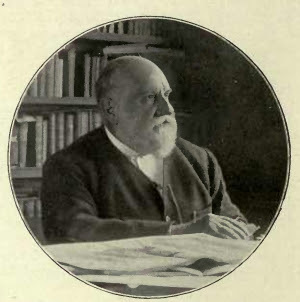

Thus it was accepted that the aspiring cat breeder was actually rather deluded, and that even if they created a stunning cat with wonderful potential, it could all go to pot with the next generation. This was also reflected in the price of purebred kittens, where £1-2 was considered a high price for a kitten “Good enough to win a first-class exhibition.” Harrison Weir- organizer of the first cat showHowever, the lack of diversity in the size and appearance of cats did not deter cat fanciers. On July 16, 1871, the first ever cat show took place. Held at Crystal Palace, it was organized by a well-known writer on animal topics and illustrator, Harrison Weir. His objective for the show was to raise awareness of the “Different breeds, colors, markings etc.”

Harrison Weir- organizer of the first cat showHowever, the lack of diversity in the size and appearance of cats did not deter cat fanciers. On July 16, 1871, the first ever cat show took place. Held at Crystal Palace, it was organized by a well-known writer on animal topics and illustrator, Harrison Weir. His objective for the show was to raise awareness of the “Different breeds, colors, markings etc.”

An exhibitor grooming her cat at a showDespite Weir’s best intentions, the main method he hit upon of distinguishing the different categories of cats was color. Even so, the show was a success and within ten years, many of the larger cities followed his example and could “boast of an annual exhibition of feline favorites.”

An exhibitor grooming her cat at a showDespite Weir’s best intentions, the main method he hit upon of distinguishing the different categories of cats was color. Even so, the show was a success and within ten years, many of the larger cities followed his example and could “boast of an annual exhibition of feline favorites.”

Next week we look at the categorization of cats at cat shows and the vagaries of fashion.

A prize-winning Persian catFor those ambitious cat owners who wished to exhibit their pet in a cat show and have other people appreciate them, their first problem was to devise categories within which to classify the cats. For dogs this was easy because there were distinct breeds ranging in size from a tiny Yorkshire terrier up to a giant Newfoundland. Not so for cats.

A prize-winning Persian catFor those ambitious cat owners who wished to exhibit their pet in a cat show and have other people appreciate them, their first problem was to devise categories within which to classify the cats. For dogs this was easy because there were distinct breeds ranging in size from a tiny Yorkshire terrier up to a giant Newfoundland. Not so for cats. It was ever the bane of the Victorian pet keeper that cats defied their master’s (or mistresses – as cats were far more likely to be kept by women) wishes. Cats had a habit of breeding willy-nilly and behind their owner’s back, which made manipulating matings to produce a specific look all the more difficult. Indeed, Charles Darwin himself said as much in 1868.

The first Crystal Palace cat show - 1871Darwin noted that people’s effort to alter the appearance of cat’s had done – “…nothing by methodical selection, and probably very little by unintentional selection…” except to save the cutest kittens and destroy adult cats that poached gamebirds.

The first Crystal Palace cat show - 1871Darwin noted that people’s effort to alter the appearance of cat’s had done – “…nothing by methodical selection, and probably very little by unintentional selection…” except to save the cutest kittens and destroy adult cats that poached gamebirds. Thus it was accepted that the aspiring cat breeder was actually rather deluded, and that even if they created a stunning cat with wonderful potential, it could all go to pot with the next generation. This was also reflected in the price of purebred kittens, where £1-2 was considered a high price for a kitten “Good enough to win a first-class exhibition.”

Harrison Weir- organizer of the first cat showHowever, the lack of diversity in the size and appearance of cats did not deter cat fanciers. On July 16, 1871, the first ever cat show took place. Held at Crystal Palace, it was organized by a well-known writer on animal topics and illustrator, Harrison Weir. His objective for the show was to raise awareness of the “Different breeds, colors, markings etc.”

Harrison Weir- organizer of the first cat showHowever, the lack of diversity in the size and appearance of cats did not deter cat fanciers. On July 16, 1871, the first ever cat show took place. Held at Crystal Palace, it was organized by a well-known writer on animal topics and illustrator, Harrison Weir. His objective for the show was to raise awareness of the “Different breeds, colors, markings etc.”

An exhibitor grooming her cat at a showDespite Weir’s best intentions, the main method he hit upon of distinguishing the different categories of cats was color. Even so, the show was a success and within ten years, many of the larger cities followed his example and could “boast of an annual exhibition of feline favorites.”

An exhibitor grooming her cat at a showDespite Weir’s best intentions, the main method he hit upon of distinguishing the different categories of cats was color. Even so, the show was a success and within ten years, many of the larger cities followed his example and could “boast of an annual exhibition of feline favorites.” Next week we look at the categorization of cats at cat shows and the vagaries of fashion.

Published on March 06, 2016 01:35

February 28, 2016

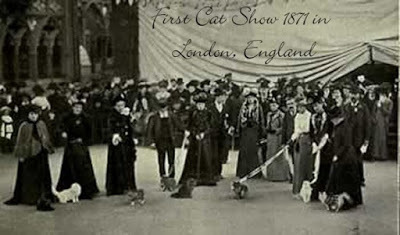

Cats as People in the 19th Century

In earlier posts we learnt that in the 19th century dogs’ embodied masculine superiority and cats’ feminine promiscuity. The Victorian’s liked people to be neatly pigeon-holed within society and kept nicely in their place. This even extended to the images in popular culture which reinforced the message that people were happier when they accepted their proper rank. To emphasize this message, there was a fashion for vignettes of animals depicted as people, looking civilized, content, and happy because they had decided to conform to human standards.

Detail from Walter Potter's "The Kittens Wedding"A typical example is the work of Walter Potter, an hotelier by day and a taxidermist by night (he ran a hotel in Sussex and used his wages to finance his hobby.) He started small by stuffing birds and worked his way up to large-scale scenes depicting animals engaged in human activities.

Detail from Walter Potter's "The Kittens Wedding"A typical example is the work of Walter Potter, an hotelier by day and a taxidermist by night (he ran a hotel in Sussex and used his wages to finance his hobby.) He started small by stuffing birds and worked his way up to large-scale scenes depicting animals engaged in human activities.

His tableaus may seem bizarre (and even repulsive) to modern tastes but at the height of his popularity Potter’s scenes attracted 30,000 visits a year. It was the human-like qualities of the stuffed animals which made them so popular, of which perhaps one of his best known exhibits was “The Kitten’s Wedding”. (Sold in 2003 for £21,150!) Beatrix Potter's 'Miss Moppet'In the modern age it is entirely distasteful to think of kittens being killed to provide corpses to put on display (but before getting too irate, don’t forget the numbers of pets which are killed each year because shelters can't house them. OK we don’t display their corpses, but modern society isn’t above killing for convenience.)

Beatrix Potter's 'Miss Moppet'In the modern age it is entirely distasteful to think of kittens being killed to provide corpses to put on display (but before getting too irate, don’t forget the numbers of pets which are killed each year because shelters can't house them. OK we don’t display their corpses, but modern society isn’t above killing for convenience.)

It is perhaps the execution (taxidermy) we find unpleasant, rather than the images themselves. Think of Beatrix Potter (no relation to Walter), Louis Wain, and Aesop’s Fables and animals acting out human adventures becomes more engaging than repulsive.

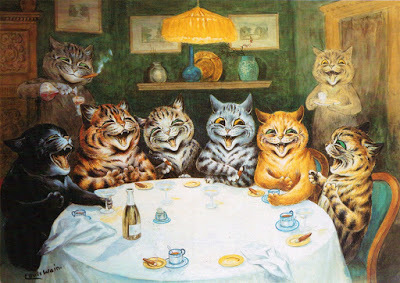

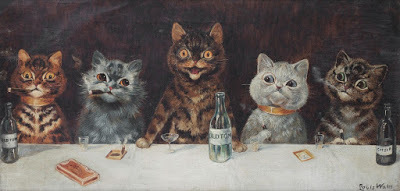

What we also have to remember is that in the 19th century cats had a more conflicted popular image than today. Memories were long and cats were still associated with witchcraft and devilment, and thought of as dangerously independent (at a time when obedience was prized) and sexually promiscuous (scandalous and totally unacceptable). Cats were linked to behaviors which were frowned upon, such as being independent and promiscuous, and therefore seeing them ‘civilized’ in humanized vignettes made the average Victorian feel self-righteous, masterful, and triumphant. Louis Wain showing cat's behaving badly.The message in scenes such as ‘The Kittens’ Wedding” was seen and understand by the Victorians. It rather amused them to see cats standing upright like people and engaged in ‘polite society’ activities such as being guests at a wedding.

Louis Wain showing cat's behaving badly.The message in scenes such as ‘The Kittens’ Wedding” was seen and understand by the Victorians. It rather amused them to see cats standing upright like people and engaged in ‘polite society’ activities such as being guests at a wedding.

By having the kittens participate in such a human activity, it emphasized the difference between human civilized society and the behavior of cats. This amused the Victorians and made them feel superior to see animals successfully integrated (or redeemed from their base nature) in this way. Clearly, if you wanted to be accepted in the 19th century this meant conforming – no quarter given to individuality and instinct, especially if you were a cat.

Detail from Walter Potter's "The Kittens Wedding"A typical example is the work of Walter Potter, an hotelier by day and a taxidermist by night (he ran a hotel in Sussex and used his wages to finance his hobby.) He started small by stuffing birds and worked his way up to large-scale scenes depicting animals engaged in human activities.

Detail from Walter Potter's "The Kittens Wedding"A typical example is the work of Walter Potter, an hotelier by day and a taxidermist by night (he ran a hotel in Sussex and used his wages to finance his hobby.) He started small by stuffing birds and worked his way up to large-scale scenes depicting animals engaged in human activities. His tableaus may seem bizarre (and even repulsive) to modern tastes but at the height of his popularity Potter’s scenes attracted 30,000 visits a year. It was the human-like qualities of the stuffed animals which made them so popular, of which perhaps one of his best known exhibits was “The Kitten’s Wedding”. (Sold in 2003 for £21,150!)

Beatrix Potter's 'Miss Moppet'In the modern age it is entirely distasteful to think of kittens being killed to provide corpses to put on display (but before getting too irate, don’t forget the numbers of pets which are killed each year because shelters can't house them. OK we don’t display their corpses, but modern society isn’t above killing for convenience.)

Beatrix Potter's 'Miss Moppet'In the modern age it is entirely distasteful to think of kittens being killed to provide corpses to put on display (but before getting too irate, don’t forget the numbers of pets which are killed each year because shelters can't house them. OK we don’t display their corpses, but modern society isn’t above killing for convenience.) It is perhaps the execution (taxidermy) we find unpleasant, rather than the images themselves. Think of Beatrix Potter (no relation to Walter), Louis Wain, and Aesop’s Fables and animals acting out human adventures becomes more engaging than repulsive.

What we also have to remember is that in the 19th century cats had a more conflicted popular image than today. Memories were long and cats were still associated with witchcraft and devilment, and thought of as dangerously independent (at a time when obedience was prized) and sexually promiscuous (scandalous and totally unacceptable). Cats were linked to behaviors which were frowned upon, such as being independent and promiscuous, and therefore seeing them ‘civilized’ in humanized vignettes made the average Victorian feel self-righteous, masterful, and triumphant.

Louis Wain showing cat's behaving badly.The message in scenes such as ‘The Kittens’ Wedding” was seen and understand by the Victorians. It rather amused them to see cats standing upright like people and engaged in ‘polite society’ activities such as being guests at a wedding.

Louis Wain showing cat's behaving badly.The message in scenes such as ‘The Kittens’ Wedding” was seen and understand by the Victorians. It rather amused them to see cats standing upright like people and engaged in ‘polite society’ activities such as being guests at a wedding. By having the kittens participate in such a human activity, it emphasized the difference between human civilized society and the behavior of cats. This amused the Victorians and made them feel superior to see animals successfully integrated (or redeemed from their base nature) in this way. Clearly, if you wanted to be accepted in the 19th century this meant conforming – no quarter given to individuality and instinct, especially if you were a cat.

Published on February 28, 2016 02:21

February 14, 2016

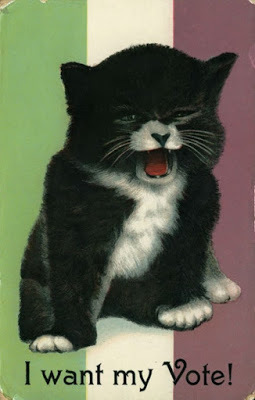

How Cats were Used to Discredit the Suffragettes

In earlier posts we saw how the Victorian’s viewed pet cats as overtly female - and this wasn’t a good thing. For a start, the Victorian’s used the link in a negative way by implying both cats and women were promiscuous with a natural inclination to low morals, and therefore in need of a firm male hand for their own good.

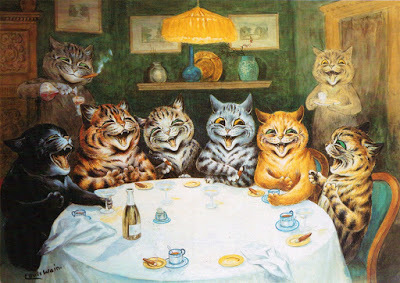

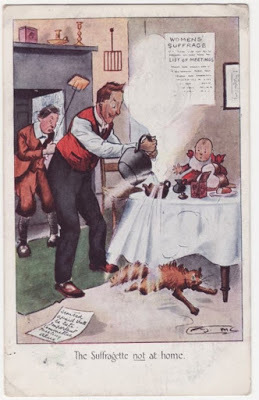

The independent nature of cats was another negative point against them. A good wife and mother was obedient to her husband, and her purpose in life was to please her husband (qualities more associated with dogs than cats). A hard-done-by husband struggling to cope at home,

A hard-done-by husband struggling to cope at home,

whilst his suffragette wife is out.

Note the scalded cat under the tableTherefore what better way to discredit the growing women’s suffrage movement than to use propaganda images of cats? Linking women to cats in such an obvious way sounded a warning shot across the bows of early female emancipation, subtly linking independence with promiscuity, and making the former seem less desirable.

In the mid to late 19th century women fought for the right to vote in public elections. Prior to this they had no political rights and were not allowed to vote in elections. This was because husband’s looked after their women, freeing them from the need to worry about political matters so they could concentrate on rearing children and keeping their husbands happy.

However, since the industrial revolution many women now worked full-time, and the inequality of their lives became increasingly difficult to ignore. Incensed by their lack of rights, women organized themselves into groups to campaign for the right to vote. As you can imagine, their menfolk were less than thrilled and felt threatened by their women wanting to be more independent. You couldn't be both feminine and a suffragette.

You couldn't be both feminine and a suffragette.

Being a suffragette changed you into a hissing spitting monster

In the 19th century, women Suffragists worked towards 'The Cause', which was a general movement to improve women's rights. Originally apolitical, as time passed the idea of 'Votes for Women' took shape and became a focal point. At first the suffragists campaigned using entirely peaceful means, but by the early 1900s a breakaway movement led by Emmeline Pankhurst became impatient with the slow progress and became increasingly militant.

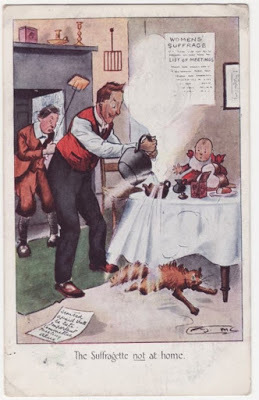

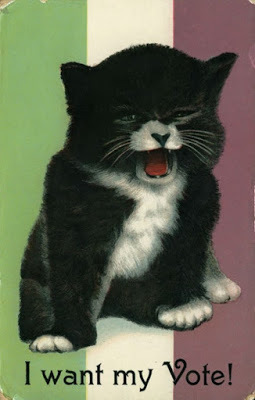

By 1912 their motto was “Deeds not words” and these new suffragettes were prepared to go on hunger strike and use violence to draw attention to their cause. All of which left male politicians with the problem of how to handle this political insurrection. One tactic was to discredit the suffragettes, and for that they used images of cats. A fat conceited cat making a fool of herself

A fat conceited cat making a fool of herself

by demanding a vote

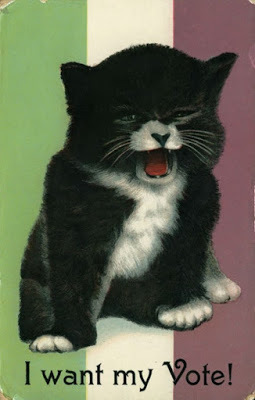

Postcards were circulated showing images of hissing, spitting cats, sending a message that femininity had gone terribly wrong. Other images, showing an angry cat holding a placard saying “Down with the Tom Cats”, which implied men had better watch out if women got the vote.

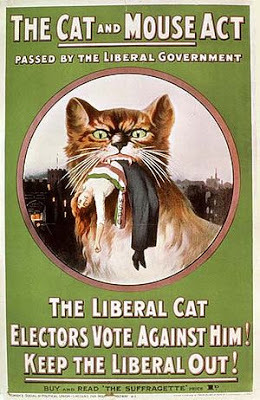

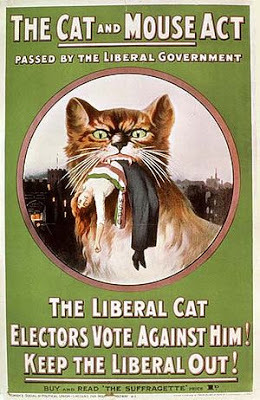

Another image showed a fat, ugly cat dressed in a suffragette’s sash, lecturing a room full of toys. The message being that the cat is self-important and engaging in a childish fantasy. By 1914 the suffragettes learnt to fight fire with fire. They created the powerful “Cat and mouse” poster, in response to the Prisoner’s Temporary Discharge Act (April 1913)-also known as the “Cat and mouse” act. The government used this law to release women on hunger strike from prison, only to have them re-arrested once they had gained weight and health back at home. The suffragettes turned male/ female iconography

The suffragettes turned male/ female iconography

on its head, to great effect

The “cat and mouse” poster reversed traditional roles, and had men play the part of a cold-blooded killer (the cat) preying upon the defenseless mouse (the woman). As a propaganda poster it made a huge impact, largely because it reversed the imagery associated with men and women.

In Britain, women over 30 gained the right to vote in 1918.

The independent nature of cats was another negative point against them. A good wife and mother was obedient to her husband, and her purpose in life was to please her husband (qualities more associated with dogs than cats).

A hard-done-by husband struggling to cope at home,

A hard-done-by husband struggling to cope at home,whilst his suffragette wife is out.

Note the scalded cat under the tableTherefore what better way to discredit the growing women’s suffrage movement than to use propaganda images of cats? Linking women to cats in such an obvious way sounded a warning shot across the bows of early female emancipation, subtly linking independence with promiscuity, and making the former seem less desirable.

In the mid to late 19th century women fought for the right to vote in public elections. Prior to this they had no political rights and were not allowed to vote in elections. This was because husband’s looked after their women, freeing them from the need to worry about political matters so they could concentrate on rearing children and keeping their husbands happy.

However, since the industrial revolution many women now worked full-time, and the inequality of their lives became increasingly difficult to ignore. Incensed by their lack of rights, women organized themselves into groups to campaign for the right to vote. As you can imagine, their menfolk were less than thrilled and felt threatened by their women wanting to be more independent.

You couldn't be both feminine and a suffragette.

You couldn't be both feminine and a suffragette.Being a suffragette changed you into a hissing spitting monster

In the 19th century, women Suffragists worked towards 'The Cause', which was a general movement to improve women's rights. Originally apolitical, as time passed the idea of 'Votes for Women' took shape and became a focal point. At first the suffragists campaigned using entirely peaceful means, but by the early 1900s a breakaway movement led by Emmeline Pankhurst became impatient with the slow progress and became increasingly militant.

By 1912 their motto was “Deeds not words” and these new suffragettes were prepared to go on hunger strike and use violence to draw attention to their cause. All of which left male politicians with the problem of how to handle this political insurrection. One tactic was to discredit the suffragettes, and for that they used images of cats.

A fat conceited cat making a fool of herself

A fat conceited cat making a fool of herselfby demanding a vote

Postcards were circulated showing images of hissing, spitting cats, sending a message that femininity had gone terribly wrong. Other images, showing an angry cat holding a placard saying “Down with the Tom Cats”, which implied men had better watch out if women got the vote.

Another image showed a fat, ugly cat dressed in a suffragette’s sash, lecturing a room full of toys. The message being that the cat is self-important and engaging in a childish fantasy. By 1914 the suffragettes learnt to fight fire with fire. They created the powerful “Cat and mouse” poster, in response to the Prisoner’s Temporary Discharge Act (April 1913)-also known as the “Cat and mouse” act. The government used this law to release women on hunger strike from prison, only to have them re-arrested once they had gained weight and health back at home.

The suffragettes turned male/ female iconography

The suffragettes turned male/ female iconographyon its head, to great effect

The “cat and mouse” poster reversed traditional roles, and had men play the part of a cold-blooded killer (the cat) preying upon the defenseless mouse (the woman). As a propaganda poster it made a huge impact, largely because it reversed the imagery associated with men and women.

In Britain, women over 30 gained the right to vote in 1918.

Published on February 14, 2016 13:43

February 7, 2016

Victorian Animal Welfare: Don't Leave Your Cats to Starve

In this series of blog posts about attitudes to cats in the 19th century, this week we look at cat welfare...but all is not as it seems .

The ideal pet cat was passive and well-behaved,

The ideal pet cat was passive and well-behaved,

just like their female ownerVictorian (male-dominated) society regarded cats as the embodiment of femininity – and this wasn’t meant as a compliment. Cats were seen as promiscuous, innately sexual, and too independent for their own good and only made good pets if they were less…well…cat-like.

In the 19thcentury men expected their wives to be obedient, chaste, and biddable. The message was clear: women needed firmly keeping in line, or much like any untrustworthy creature their morals might degenerate to those of an alley cat.

By the end of the 19th century it was estimated most households owned at least one cat, but these were working animals. They lived outdoors, and allowed in during the day to catch mice and keep vermin down. However, there were a significant number of middle class women who kept a pet cat. This was acceptable if the pet was well behaved, because it exemplified the triumph of civilization over baser nature; woman over cat, man over woman.

The problem then arose as to what happened to that pet cat when the household went on holiday. Frequently the answer was to turn the cat out onto the street for the duration of the time the owner was away. However, by the 1880s there was a ground swell of opinion, given voice by the newspapers and pet-keeping manuals, against this practice. “Don’t leave your cats to starve while you go for an enjoyable holiday.”

On the face of it, this would seem to be the birth pangs of animal welfare concerns for our feline friends. But when you delve deeper it seems the appeal was not made for the reason you might suppose (i.e. the poor animal suffering through lack of food)

The motivation behind this appeal was that a cat forced onto the streets, without the civilizing influence of man, would revert to their bestial habits. This wasn’t a case of chastising owners for abandoning their pets, but shining a light on the weak moral nature of cats, as proven when they reverted to natural behavior.

Stray cats were regarded as the equivalent of prostitutes, while a pet cat was equivalent to a good housewife. To turn one (the wife) into the other (a prostitute) was what the protests objected to – not because they were worried about cat welfare, but because of the example it to women. Female cat owners were often stereotypedA cat left to fend for themselves, was “corrupted by their own impulses” (presumably to eat and reproduce) and the degraded animal was no longer a suitable companion for a gentlewoman.

Female cat owners were often stereotypedA cat left to fend for themselves, was “corrupted by their own impulses” (presumably to eat and reproduce) and the degraded animal was no longer a suitable companion for a gentlewoman.

So there we have it: “Don’t leave your cat to starve”…but because 19th century men feared it might corrupt their wives.

Next week: The Suffragettes and Cats. As a taster, what do you make of the imagery in the postcard show below? Do share your thoughts and leave a comment.

The ideal pet cat was passive and well-behaved,

The ideal pet cat was passive and well-behaved,just like their female ownerVictorian (male-dominated) society regarded cats as the embodiment of femininity – and this wasn’t meant as a compliment. Cats were seen as promiscuous, innately sexual, and too independent for their own good and only made good pets if they were less…well…cat-like.

In the 19thcentury men expected their wives to be obedient, chaste, and biddable. The message was clear: women needed firmly keeping in line, or much like any untrustworthy creature their morals might degenerate to those of an alley cat.

By the end of the 19th century it was estimated most households owned at least one cat, but these were working animals. They lived outdoors, and allowed in during the day to catch mice and keep vermin down. However, there were a significant number of middle class women who kept a pet cat. This was acceptable if the pet was well behaved, because it exemplified the triumph of civilization over baser nature; woman over cat, man over woman.

The problem then arose as to what happened to that pet cat when the household went on holiday. Frequently the answer was to turn the cat out onto the street for the duration of the time the owner was away. However, by the 1880s there was a ground swell of opinion, given voice by the newspapers and pet-keeping manuals, against this practice. “Don’t leave your cats to starve while you go for an enjoyable holiday.”

On the face of it, this would seem to be the birth pangs of animal welfare concerns for our feline friends. But when you delve deeper it seems the appeal was not made for the reason you might suppose (i.e. the poor animal suffering through lack of food)

The motivation behind this appeal was that a cat forced onto the streets, without the civilizing influence of man, would revert to their bestial habits. This wasn’t a case of chastising owners for abandoning their pets, but shining a light on the weak moral nature of cats, as proven when they reverted to natural behavior.

Stray cats were regarded as the equivalent of prostitutes, while a pet cat was equivalent to a good housewife. To turn one (the wife) into the other (a prostitute) was what the protests objected to – not because they were worried about cat welfare, but because of the example it to women.

Female cat owners were often stereotypedA cat left to fend for themselves, was “corrupted by their own impulses” (presumably to eat and reproduce) and the degraded animal was no longer a suitable companion for a gentlewoman.

Female cat owners were often stereotypedA cat left to fend for themselves, was “corrupted by their own impulses” (presumably to eat and reproduce) and the degraded animal was no longer a suitable companion for a gentlewoman.So there we have it: “Don’t leave your cat to starve”…but because 19th century men feared it might corrupt their wives.

Next week: The Suffragettes and Cats. As a taster, what do you make of the imagery in the postcard show below? Do share your thoughts and leave a comment.

Published on February 07, 2016 06:00

January 31, 2016

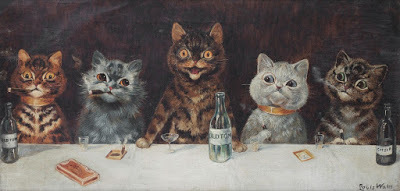

Victorian Snobbery about Cats as Pets

Last week I asked if you own an iPhone. This week my question is: Do you drive a Skoda or a Ferrari?

The reason is to illustrate how the Victorian’s could be very sniffy about cat-ownership. If we think of this snobbery in terms of cars (rather than cats – See what I did there), those people who own and drive a luxury brand such as Ferrari or Porsche, wouldn’t be seen dead anyway near a humble Skoda. Likewise, you may form a very different mental picture of a stranger based on the vehicle they drive. Thus was also the case for pet ownership in the 19th century.

The Victorian’s jumped to a lot of conclusion about your status and importance, based on the pets you kept. When it comes to our feline friends the very attributes that made them ideal pets in the middle ages made them less acceptable in the 19thcentury. Quite simply, the idea that cats caught mice gave them the mantle of a “poor man’s pet”. A lot of responsibility was placed on the furry (or feathered) shoulders of a Victorian pet. For a start, an animal that was welcomed into the home was expected to ditch their “beastly” attributes and become civilized. Indeed, the pet’s behavior reflected on the morals of the owner, so the independent nature of cats, plus their propensity to roam and find boyfriends, made them far too base and lascivious for Victorian tastes. Louis Wain's "The Bachelor Party" - Cats behaving badly

Louis Wain's "The Bachelor Party" - Cats behaving badly

Indeed, dogs were thought to show masculine qualities (and were therefore superior) such as heroism and loyalty, whereas cats exhibited inferior female tendencies such as perfidy and sexual inconsistency. In fact, in the early 20th century militant suffragettes sought to dissociate the link between women and cats in order to get men to take them more seriously. Anyhow, I digress. Most pet cats were expected to catch mice, and to encourage this cats were often kept hungry. “…the cruel mistake of supposing that a cat will be a keener and better mouser if not sufficiently fed.”

However, there were some people who kept cats and were proud of it. But if they decided to sell the cat, for whatever reason, they tended to stress their practical qualities. “Angora cats. Several very handsome ones, splendid mousers.”

So whilst the Angora was a rare and expensive breed, it was still thought best to point out their hunting prowess. Indeed, the breeding of pedigree cats was considered second rate compared to that of dogs, and ranked alongside breeding rabbits, guinea pigs and other pets of the working man.

It took the founding of the National Cat Club in 1887 for the social status of cats to see an upward swing. However, in part this was done by arranging working men’s cats to be exhibited in a separate class, as if to emphasize the difference between cats belonging to the less affluent and those of the middle or upper classes! Evidently this was a sort of social segregation for cats, or a feline apartite, the like of which would hopefully never see the light of day in the modern age.

The reason is to illustrate how the Victorian’s could be very sniffy about cat-ownership. If we think of this snobbery in terms of cars (rather than cats – See what I did there), those people who own and drive a luxury brand such as Ferrari or Porsche, wouldn’t be seen dead anyway near a humble Skoda. Likewise, you may form a very different mental picture of a stranger based on the vehicle they drive. Thus was also the case for pet ownership in the 19th century.

The Victorian’s jumped to a lot of conclusion about your status and importance, based on the pets you kept. When it comes to our feline friends the very attributes that made them ideal pets in the middle ages made them less acceptable in the 19thcentury. Quite simply, the idea that cats caught mice gave them the mantle of a “poor man’s pet”. A lot of responsibility was placed on the furry (or feathered) shoulders of a Victorian pet. For a start, an animal that was welcomed into the home was expected to ditch their “beastly” attributes and become civilized. Indeed, the pet’s behavior reflected on the morals of the owner, so the independent nature of cats, plus their propensity to roam and find boyfriends, made them far too base and lascivious for Victorian tastes.

Louis Wain's "The Bachelor Party" - Cats behaving badly

Louis Wain's "The Bachelor Party" - Cats behaving badlyIndeed, dogs were thought to show masculine qualities (and were therefore superior) such as heroism and loyalty, whereas cats exhibited inferior female tendencies such as perfidy and sexual inconsistency. In fact, in the early 20th century militant suffragettes sought to dissociate the link between women and cats in order to get men to take them more seriously. Anyhow, I digress. Most pet cats were expected to catch mice, and to encourage this cats were often kept hungry. “…the cruel mistake of supposing that a cat will be a keener and better mouser if not sufficiently fed.”

However, there were some people who kept cats and were proud of it. But if they decided to sell the cat, for whatever reason, they tended to stress their practical qualities. “Angora cats. Several very handsome ones, splendid mousers.”

So whilst the Angora was a rare and expensive breed, it was still thought best to point out their hunting prowess. Indeed, the breeding of pedigree cats was considered second rate compared to that of dogs, and ranked alongside breeding rabbits, guinea pigs and other pets of the working man.

It took the founding of the National Cat Club in 1887 for the social status of cats to see an upward swing. However, in part this was done by arranging working men’s cats to be exhibited in a separate class, as if to emphasize the difference between cats belonging to the less affluent and those of the middle or upper classes! Evidently this was a sort of social segregation for cats, or a feline apartite, the like of which would hopefully never see the light of day in the modern age.

Published on January 31, 2016 03:32

January 24, 2016

The Importance of Pets to the Victorians

Do you have an iPhone 6? If so, why did you choose it: Did you buy into the latest trend or was it because of the functionality (or a bit of both)? In the 19th century consumerism was in full swing, and pets were every bit as important to advertise your disposable income as an iPhone 6 is in the 21st century.

Control and discipline of pets

Control and discipline of pets

was a mustIndeed, the 18th and 19th centuries there was a huge upsurge in pet keeping and activities such as visiting the zoo. By 1851 over half the population of England lived in cities, and yet this was a time when people were still strongly connected to animals. You only have to think of the horse troughs in High Streets to realize how different life was back then.But the role of animals was changing from being beasts of burden or livestock, to something altogether more social. The new phenomenum of keeping animals as pets was catching on. Indeed, visiting zoos became hugely popular, where the exhibits were regarded as public pets and objects of scientific interest. The idea of the hidden beast within man led to some confusing ideas

The idea of the hidden beast within man led to some confusing ideas

However, keeping pets was more complicated than having a cozy companion to snuggle on your lap. The Victorians, being Victorians, believed that an animal’s behavior was a reflection of their owner. Therefore the lapdog, caged parrot, or house cat became a symbol for the morals of their owner. Indeed, the human – animal bond became an expression of many of the inequalities of Victorian society such as social hierarchy and class, and your gender or ethnic origins. Good behavior reflected well on the ownerThis belief system intensified with the publication of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of the Species (1859). This stimulated debate (amongst other things) about how man’s genetic kinship to animals and amplified anxieties about the hidden beast lurking within man.It became doubly important to have control over your pets, because well-behaved animals were an indicator of a harmonious household run by a civilized master. Hence there was a strong emphasis on discipline when it came to dog training – and the beginnings of the misplaced “wolf-model” of dog behavior are evident, with it being crucial to dominate your dog in order to prove man’s superior status.

Good behavior reflected well on the ownerThis belief system intensified with the publication of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of the Species (1859). This stimulated debate (amongst other things) about how man’s genetic kinship to animals and amplified anxieties about the hidden beast lurking within man.It became doubly important to have control over your pets, because well-behaved animals were an indicator of a harmonious household run by a civilized master. Hence there was a strong emphasis on discipline when it came to dog training – and the beginnings of the misplaced “wolf-model” of dog behavior are evident, with it being crucial to dominate your dog in order to prove man’s superior status.

At the same time, another side of pet-keeping was growing – that of “Animal Fancies” or breeding animals to enhance beauty. In the latter part of the Victorian era this saw the rise of dog and cat shows, as well as exhibitions to display the latest in pet-keeping accoutrements such as cages, collars, and luxury beds.

The singular relationship of Victorians to animals was recognized by foreign nations, who frequently gifted exotic animals to the crown or her government in order to curry favor. But this gives just a hint of the complex flavor of the Victorian’s attitude to pets… to be explored in future posts.

Control and discipline of pets

Control and discipline of petswas a mustIndeed, the 18th and 19th centuries there was a huge upsurge in pet keeping and activities such as visiting the zoo. By 1851 over half the population of England lived in cities, and yet this was a time when people were still strongly connected to animals. You only have to think of the horse troughs in High Streets to realize how different life was back then.But the role of animals was changing from being beasts of burden or livestock, to something altogether more social. The new phenomenum of keeping animals as pets was catching on. Indeed, visiting zoos became hugely popular, where the exhibits were regarded as public pets and objects of scientific interest.

The idea of the hidden beast within man led to some confusing ideas

The idea of the hidden beast within man led to some confusing ideasHowever, keeping pets was more complicated than having a cozy companion to snuggle on your lap. The Victorians, being Victorians, believed that an animal’s behavior was a reflection of their owner. Therefore the lapdog, caged parrot, or house cat became a symbol for the morals of their owner. Indeed, the human – animal bond became an expression of many of the inequalities of Victorian society such as social hierarchy and class, and your gender or ethnic origins.

Good behavior reflected well on the ownerThis belief system intensified with the publication of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of the Species (1859). This stimulated debate (amongst other things) about how man’s genetic kinship to animals and amplified anxieties about the hidden beast lurking within man.It became doubly important to have control over your pets, because well-behaved animals were an indicator of a harmonious household run by a civilized master. Hence there was a strong emphasis on discipline when it came to dog training – and the beginnings of the misplaced “wolf-model” of dog behavior are evident, with it being crucial to dominate your dog in order to prove man’s superior status.

Good behavior reflected well on the ownerThis belief system intensified with the publication of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of the Species (1859). This stimulated debate (amongst other things) about how man’s genetic kinship to animals and amplified anxieties about the hidden beast lurking within man.It became doubly important to have control over your pets, because well-behaved animals were an indicator of a harmonious household run by a civilized master. Hence there was a strong emphasis on discipline when it came to dog training – and the beginnings of the misplaced “wolf-model” of dog behavior are evident, with it being crucial to dominate your dog in order to prove man’s superior status.

At the same time, another side of pet-keeping was growing – that of “Animal Fancies” or breeding animals to enhance beauty. In the latter part of the Victorian era this saw the rise of dog and cat shows, as well as exhibitions to display the latest in pet-keeping accoutrements such as cages, collars, and luxury beds.

The singular relationship of Victorians to animals was recognized by foreign nations, who frequently gifted exotic animals to the crown or her government in order to curry favor. But this gives just a hint of the complex flavor of the Victorian’s attitude to pets… to be explored in future posts.

Published on January 24, 2016 04:42

January 10, 2016

What is a Pet? A Historical Perspective

Pets are important to me and I can’t imagine life without them. Fortunately, in the modern day pet keeping is accepted and thought of as normal – but this wasn’t always the case. In medieval times it was the strongly held Christian belief that God created animals for the use of man. Animals had the status of slaves, there to serve, with man as their superior. It was held that a deep affection for a pet was a sin.

Times were tough so you can understand this functional outlook on life. After all if you were a regular man or woman struggling to feed your family, then it could easily be argued it was a sin to put food into the mouth of an animal that didn’t have a use or purpose. Although people did keep pets in the dark and middle ages, this was largely the preserve of the wealthy. Any self-respecting Lord and his lady kept pets because they had the money to do so and wanted to advertise the fact as a sign of their status and power. Indeed, these pets were often overweight as they were overfed to make it obvious that their owner wanted for nothing.

In medieval times people expected animals to live outdoors and to be functional, so the idea of indoor animals that existed purely for companionship or amusement seemed alien and extravagant. It took a shift in attitude in the 18th century, for pet-keeping to become more widely accepted. This change took place because of a philosophical argument that taking good care of animals articulated what it was to be a human or “humane”. Keeping a pet was looked on as a sign of moral-care rather than profligacy. In the 18thcentury saw the birth of consumerism. More people were living in towns and cities, and so more people were spending more time indoors. The idea of “indoor animals” or pets was truly born. As the British Empire expanded and travelers returned with exotic animals, this coincided perfectly regular people having a modicum of disposable cash and their interest in keeping pets.

But what of the word “pet” itself? The first reference to a “pet” comes from 1539 and refers to a lamb hand-reared in the house. These two characteristics, being tame and living in the house, formed the basis for the definition of pet but fails to hint at the favoritism with which pets are held.A modern definition is: “A domestic or tamed animal or bird kept for companionship or pleasure.”And finally, historian Prof Keith Thomas proposed three defining features of a medieval pet: · It’s kept in the house· It’s given a name· It’s never eaten…

Can’t say fairer than that!

Times were tough so you can understand this functional outlook on life. After all if you were a regular man or woman struggling to feed your family, then it could easily be argued it was a sin to put food into the mouth of an animal that didn’t have a use or purpose. Although people did keep pets in the dark and middle ages, this was largely the preserve of the wealthy. Any self-respecting Lord and his lady kept pets because they had the money to do so and wanted to advertise the fact as a sign of their status and power. Indeed, these pets were often overweight as they were overfed to make it obvious that their owner wanted for nothing.

In medieval times people expected animals to live outdoors and to be functional, so the idea of indoor animals that existed purely for companionship or amusement seemed alien and extravagant. It took a shift in attitude in the 18th century, for pet-keeping to become more widely accepted. This change took place because of a philosophical argument that taking good care of animals articulated what it was to be a human or “humane”. Keeping a pet was looked on as a sign of moral-care rather than profligacy. In the 18thcentury saw the birth of consumerism. More people were living in towns and cities, and so more people were spending more time indoors. The idea of “indoor animals” or pets was truly born. As the British Empire expanded and travelers returned with exotic animals, this coincided perfectly regular people having a modicum of disposable cash and their interest in keeping pets.

But what of the word “pet” itself? The first reference to a “pet” comes from 1539 and refers to a lamb hand-reared in the house. These two characteristics, being tame and living in the house, formed the basis for the definition of pet but fails to hint at the favoritism with which pets are held.A modern definition is: “A domestic or tamed animal or bird kept for companionship or pleasure.”And finally, historian Prof Keith Thomas proposed three defining features of a medieval pet: · It’s kept in the house· It’s given a name· It’s never eaten…

Can’t say fairer than that!

Published on January 10, 2016 12:07

January 3, 2016

Van Amburgh: Animal Trainer or Bully?

Many things interest me- from animal behavior to history. So it was with interest that I came across a reference in a Victorian book to training cats. The author (Henry Ross) was talking in general terms about the independent nature of cats.

“It must not be inferred, however, that they [cats] are untamable, for every creature is capable…of being trained by man, provided it [the animal] receives due attention.”This sounds promising – and I went on to read:

“We have sufficient evidence in the feats performed by the lions and tigers of Mr. Carter and Van Amburgh that felines are by no means destitute of intelligent docility.”

Keen to know more, I researched Isaac Van Amburgh, but was horrified by what I read.

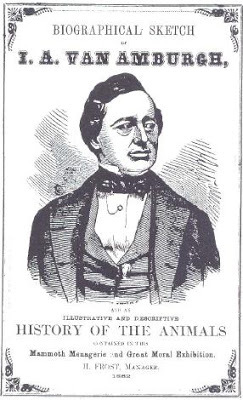

Van Amburgh’s LegendBorn in 1811, Van Amburgh started out from humble origins working as a cage cleaner at the Zoological Institute of New York. He became fascinated by the biblical story of Daniel in the lions’ den and the idea of dominating big cats. Indeed, as he went about his work cleaning out the lions and tigers, his employer noticed the commanding control he had over them.

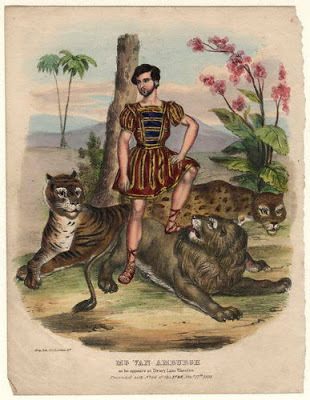

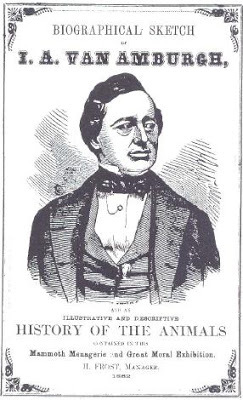

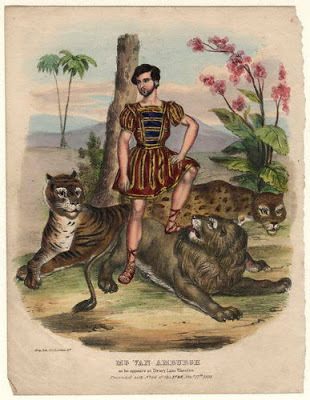

An animal dealer, Titus, with links to the Zoological Institute saw the potential for a novel act, where a man “tamed” wild animals. In his own words:“Novelty plus publicity meant money.” Van Amburgh in his early costume of a Roman toga

Van Amburgh in his early costume of a Roman toga

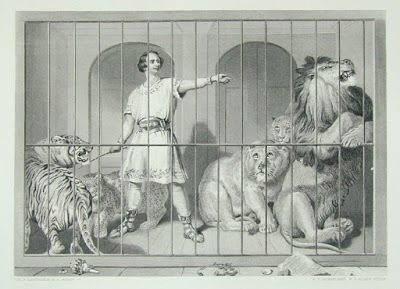

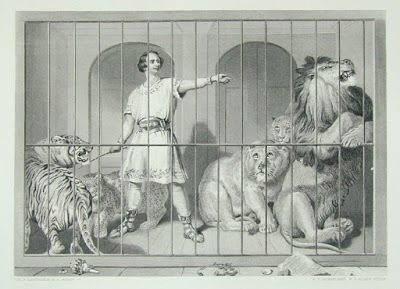

Titus’ instincts were correct, and the act that made Van Amburgh a rich man, went from strength to strength. He entered a cage containing a lion, lioness, panther, leopard, leopardess, and a black-maned lion. The animals shrank away from him, such was his commanding presence. Then he reclined and commanded each animal to approach him, one by one, and lick his feet in deference.

“The effect of his power was instantaneous. The Lion halted and stood transfixed. The Tiger crouched. The Panther with a suppressed growl of rage sprang back, while the Leopard receded gradually from its master. The spectators were overwhelmed with wonder .... “

Indeed, Van Amburgh was a sensation not just in America, but in England where he performed for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. He refined his act, adding in such spectacular feats as putting his head in the lion’s mouth. Victoria, filled with admiration, even commissioned Sir Edwin Landseer to paint Van Amburgh’s portrait.

Van Amburgh’s MethodsVan Amburgh was a mega-star in his time and his act made him a wealthy man. However his methods were not without controversy, even during his life time, and looking back it has to be said that his training methods were shameful. However, his immoral methods paid off, he earnt a fortune and died a wealthy man safe in his bed.

He regularly beat the animals with an iron bar, and his “training” method was to intimidate the big cats using pain, fear, and hunger. Van Amburgh’s publicity agent even admitted the lions were starved for days prior to a royal performance, as if this was something to be proud of. Landseer's portrait of Van Amburgh

Landseer's portrait of Van Amburgh

In fairness, right-minded Victorians were horrified, but Van Amburgh’s defended his methods by quoting the bible, and Genesis 1:26 saying that God had given man dominion over the animals.

Van Amburgh appears to have been an early proponent of an extreme form of dominance method of training, so popular in dog obedience circles until it’s debunking in recent years. The physical and mental abuse of animals for human entertainment completely immoral, and beating animals into submission is wholly unacceptable.

Let us hope against hopes that if in the modern age a similar misuse of animals took place for our entertainment, we would not be taken in and object in the strongest terms.

“It must not be inferred, however, that they [cats] are untamable, for every creature is capable…of being trained by man, provided it [the animal] receives due attention.”This sounds promising – and I went on to read:

“We have sufficient evidence in the feats performed by the lions and tigers of Mr. Carter and Van Amburgh that felines are by no means destitute of intelligent docility.”

Keen to know more, I researched Isaac Van Amburgh, but was horrified by what I read.

Van Amburgh’s LegendBorn in 1811, Van Amburgh started out from humble origins working as a cage cleaner at the Zoological Institute of New York. He became fascinated by the biblical story of Daniel in the lions’ den and the idea of dominating big cats. Indeed, as he went about his work cleaning out the lions and tigers, his employer noticed the commanding control he had over them.

An animal dealer, Titus, with links to the Zoological Institute saw the potential for a novel act, where a man “tamed” wild animals. In his own words:“Novelty plus publicity meant money.”

Van Amburgh in his early costume of a Roman toga

Van Amburgh in his early costume of a Roman toga

Titus’ instincts were correct, and the act that made Van Amburgh a rich man, went from strength to strength. He entered a cage containing a lion, lioness, panther, leopard, leopardess, and a black-maned lion. The animals shrank away from him, such was his commanding presence. Then he reclined and commanded each animal to approach him, one by one, and lick his feet in deference.

“The effect of his power was instantaneous. The Lion halted and stood transfixed. The Tiger crouched. The Panther with a suppressed growl of rage sprang back, while the Leopard receded gradually from its master. The spectators were overwhelmed with wonder .... “

Indeed, Van Amburgh was a sensation not just in America, but in England where he performed for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. He refined his act, adding in such spectacular feats as putting his head in the lion’s mouth. Victoria, filled with admiration, even commissioned Sir Edwin Landseer to paint Van Amburgh’s portrait.

Van Amburgh’s MethodsVan Amburgh was a mega-star in his time and his act made him a wealthy man. However his methods were not without controversy, even during his life time, and looking back it has to be said that his training methods were shameful. However, his immoral methods paid off, he earnt a fortune and died a wealthy man safe in his bed.

He regularly beat the animals with an iron bar, and his “training” method was to intimidate the big cats using pain, fear, and hunger. Van Amburgh’s publicity agent even admitted the lions were starved for days prior to a royal performance, as if this was something to be proud of.

Landseer's portrait of Van Amburgh

Landseer's portrait of Van AmburghIn fairness, right-minded Victorians were horrified, but Van Amburgh’s defended his methods by quoting the bible, and Genesis 1:26 saying that God had given man dominion over the animals.

Van Amburgh appears to have been an early proponent of an extreme form of dominance method of training, so popular in dog obedience circles until it’s debunking in recent years. The physical and mental abuse of animals for human entertainment completely immoral, and beating animals into submission is wholly unacceptable.

Let us hope against hopes that if in the modern age a similar misuse of animals took place for our entertainment, we would not be taken in and object in the strongest terms.

Published on January 03, 2016 04:34

December 20, 2015

Some Old Sayings about Cats

Some expressions concerning cats are well known, such as “Not enough room to swing a cat”, or “Let the cat out of the bag”, but what of some of the more unusual sayings.

There were actually a surprising number, although few if any are still in wide parlance, which is a shame judging from the few that I’ve listed below.

“Fain would the Cat fish eat, but she is loth to wet her feet” In more modern language:“The cat would eat fish, but will not wet her feet”. The saying is about wanting the result but not being prepared to put the effort in – a fancy way of saying “No pain, no gain.”The first written record of this saying goes back to 1380 and Chaucer’s “House of Fame.” The expression seems to have been in wide usage and is mentioned by numerous other authors in the middle ages, and then by Shakespeare

“How can the cat help it if the maid be a fool?” This is asking a basic question of morality: How can it be stealing if temptation is left in one’s path. So that fish that’s left on the table is asking to be eaten by the cat (without getting her paws wet!) This is an old American saying dating from around 1810, and implies a certain abrogation of personal responsibility.

“A cat always falls on its feet.”Dating from the early 18th century, this is a marker of good luck. “[He] had a cat’s luck, always landing on his feet.” Church History. 1713Or there’s this optimistic way of saying that truth will out in the end. “Truth is like a cat and always comes down on its feet; jerk it as high as you please.” Cooper’s Letters. 1831.

Of course the last part of this statement is not technically correct, as there is an optimum height for cats to fall from, in order to rotate fully and land with all four paws on the ground. Also “High rise syndrome” refers to cats that fall from above two floors high, and hit the ground so hard they break their jaws and pelvis – so not even landing on all fours is enough to protect you from injury in some circumstances.

“The cat in gloves catches no mice.”Another American saying dating from around 1754. I rather like the allusion, a cross between having the right tools for the job and not handicapping yourself. In fact, it would make rather a good personal motto.

There were actually a surprising number, although few if any are still in wide parlance, which is a shame judging from the few that I’ve listed below.

“Fain would the Cat fish eat, but she is loth to wet her feet” In more modern language:“The cat would eat fish, but will not wet her feet”. The saying is about wanting the result but not being prepared to put the effort in – a fancy way of saying “No pain, no gain.”The first written record of this saying goes back to 1380 and Chaucer’s “House of Fame.” The expression seems to have been in wide usage and is mentioned by numerous other authors in the middle ages, and then by Shakespeare

“How can the cat help it if the maid be a fool?” This is asking a basic question of morality: How can it be stealing if temptation is left in one’s path. So that fish that’s left on the table is asking to be eaten by the cat (without getting her paws wet!) This is an old American saying dating from around 1810, and implies a certain abrogation of personal responsibility.

“A cat always falls on its feet.”Dating from the early 18th century, this is a marker of good luck. “[He] had a cat’s luck, always landing on his feet.” Church History. 1713Or there’s this optimistic way of saying that truth will out in the end. “Truth is like a cat and always comes down on its feet; jerk it as high as you please.” Cooper’s Letters. 1831.

Of course the last part of this statement is not technically correct, as there is an optimum height for cats to fall from, in order to rotate fully and land with all four paws on the ground. Also “High rise syndrome” refers to cats that fall from above two floors high, and hit the ground so hard they break their jaws and pelvis – so not even landing on all fours is enough to protect you from injury in some circumstances.

“The cat in gloves catches no mice.”Another American saying dating from around 1754. I rather like the allusion, a cross between having the right tools for the job and not handicapping yourself. In fact, it would make rather a good personal motto.

Published on December 20, 2015 11:42

'Familiar Felines.'

Following on from last weeks Halloween posting, today's blog post looks at the unwanted image of cats as the witches familiar - from the Norse Goddess Freya to lonely women in the middle ages.

The full Following on from last weeks Halloween posting, today's blog post looks at the unwanted image of cats as the witches familiar - from the Norse Goddess Freya to lonely women in the middle ages.

The full post can found at:

http://graceelliot-author.blogspot.com

...more

The full Following on from last weeks Halloween posting, today's blog post looks at the unwanted image of cats as the witches familiar - from the Norse Goddess Freya to lonely women in the middle ages.

The full post can found at:

http://graceelliot-author.blogspot.com

...more

- Grace Elliot's profile

- 156 followers