Robert M. Price's Blog, page 6

June 6, 2011

Deconstructing Virtue

The once chic term "deconstruction" is derived from Heidegger's term destruktion because the latter didn't actually mean "destruction" as in English. It meant something more like "disassembling" a mechanism in order to adjust or to fix it. Jacques Derrida therefore decided to modify the term as "deconstruction." One undoes the construction of terms, ideas, texts, philosophies, whole worldviews. In this way one sometimes discovers dimensions, shades of meaning, that have been suppressed or neglected, then forgotten, with a sad loss in meaning and utility. Perhaps the most famous of Heidegger's destruktionen or deconstructions was that performed upon the word "truth," in its Greek original aletheia. It breaks down into elements suggesting "removing forgetfulness." Remember the River Lethe, the River of Forgetfulness, that new entrants into Hades were required to sample? Truth is the revealing of the forgotten. That's certainly Plato's epistemology in a nut shell, right? All deconstructions seek to uncover such an underlying reality by taking a word or notion down to its basic roots and discovering thereby a dimension of meaning that has been overshadowed but which, when you think about it, has lingered unobtrusively nonetheless, still imparting, or trying to impart, an added element of meaning. This, I gather, is the basis for the attempt of the later Heidegger to read poems and to gain through them a new vision of the vista of truth the original poets saw and to draw new insights, new aspects of Being, from it.

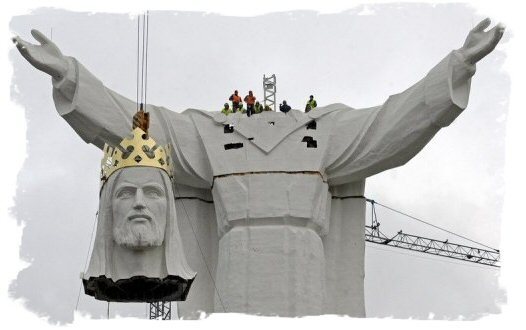

In any case, I want to suggest briefly the importance of another crucial word: virtue. The Latin virtus translates the Greek arête, which also means power and ultimately implies that moral virtue, too, is a kind of power. When Jesus is said to have involuntarily healed the woman with a hemmorhage (Mark 5:24-34), then sensed that "power had gone out of him," the word for power is dunamis, but the Latin Vulgate renders it with virtus. And this represents a deconstruction because it invites as its explanation Aristotle's teaching concerning morality as a power, ability, or skill. He discusses the subject in the Nichomachean Ethics (The Ethics, dedicated to his nephew Nicomachius).

Aristotle, for example, holds that we cannot expect little children to have developed any moral sense of their own. We hope that they will one day, but to start them off right, we must teach them what to do and not to do by command and by rote. "Because I said so, that's why." We don't want them to learn the hard way, by putting their hand on the stove. That will teach them, but we want to warn them and hope they'll take our word for it. Eventually we can reason with them and can explain why A is a wise course of action, and why B, by contrast, is not. Even better, we aim for the day when our children will not only see why we thought our moral rules to be right, but will also be able to evaluate for themselves whether we were right about it — and to reason out their own rules. They will have learned the skill of morality.

What about keeping moral rules, whether ours or theirs? Aristotle explained that we must first decide the right attitude, reaction or action and determine to shape our behavior into conformity with it, even if we feel we are play-acting. That does not make us hypocrites. No, it is the way to reprogram ourselves so that what we believe in our heads to be right will penetrate our hearts and become second nature. It will finally become spontaneous, our default behavior. This, by the way, is why the "daily affirmations" of self-help groups, often ridiculed ("I'm good enough, I'm smart enough, and, doggone it, people like me!"), are by no means silly. They represent good Aristotelian strategy. You are reprogramming yourself, refashioning your habits of thought, feeling, and reaction.

Thus virtue, morality, is seen to be a power and a skill that one may cultivate and strengthen. I say this is how morality ought to be taught. And I further believe that Humanism has a special mission to teach such morality. Let me back up and try to explain why.

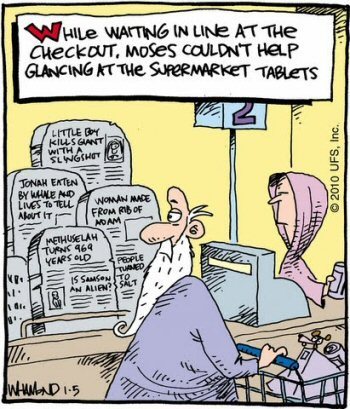

I see three basic approaches to moral thinking, each claiming many adherents. There is the traditional ethic of religion: deontological ethics. This means "duty ethics." The moral agent/actor obeys certain rules because an authority has promulgated them. God gave the Torah to Moses. Shamash gave the Code to Hammurabi. Apollo gave his law to the Greeks, etc. We are bound to obey the gods. (And this led Socrates to ask the theology-destroying question whether a thing is right because the gods love it, or if the gods love it and that makes it right. Kids, don't try this one at home, er, I mean in church.) Our duty is to know the rule, and we are judged by our obedience or disobedience whether or not we knew our duty. This is what Paul Tillich, following Kant, called "heteronomy," an alien law imposed upon the conscience from without. There is always the danger of stunting moral growth here in that we may obey the commandment simply out of fear of the repercussions if we do not. And that threatens to make moral obedience into mere lip-service and cringing hypocrisy.

Humanists have embraced the alternative ethical approach of teleological or utilitarian ethics. What is right is that act which brings the greatest benefit to the greatest number (or that which was intended to, as far as results could have been foreseen). The telos, the goal, of an act is what matters. And we humans must use our best wisdom to decide what that is. Situation ethics, obviously, is a type of teleological ethics. Remember Kant's dilemma? Suppose I knock furiously on your door, looking over my shoulder, and plead with you to let me hide in your basement, and you let me. Then, minutes later, here comes a knife-wielding enemy of mine demanding to know if you have seen me. What are you to do? Incredibly but consistently, Kant said your only obligation is to tell the truth, not to lie. "Yeah, he's in the basement." That is deontological ethics in its most stark and ruthless form! A utilitarian, on the other hand, would have no trouble deciding that in this particular case telling the truth is going to do no one any good, so his obligation is to save life. Thus he is obliged in this case to lie. "Price? Sorry, never heard of him! Have a nice day!"

The third option, while not incompatible with the others, is virtue ethics, which centers upon the moral character of the agent. What will the choice of a particular act do to one's character? To one's integrity? Are certain major acts degrading or destructive of character? Will certain patterns of minor acts, comprises, have the same desultory result? "I could tamper with that evidence to make sure the guilty party is punished, but what gives me the right? I could torture that terrorist to get vital information, but wouldn't that reduce me to his level? Could I live with myself if I did this or that?"

Both teleological and virtue ethics are "autonomous" rather than "heteronomous." They represent one's own law and morality, not someone else's. I like that. But I am often disturbed to observe Humanists acting from teleological, utilitarian ethics and thinking it is sufficient. They seem to me to be neglecting virtue and character. The result is, for example, what appears to be the unscrupulous machination of politicians who openly boast about their liberal policies to their constituents, the people, the nation, the majority, minorities, whatever. As individuals they may be exposed as rascals, adulterers, liars, embezzlers, tax cheats, etc., but their defenders maintain that these "personal" matters just do not bear on their job performance. They ridicule those who see the possible social/political/military implications of a lack of personal integrity. Such objectors are denounced as Puritans and prudes. Worse yet, as "conservatives." I was stunned when, after the commencement of the War on Terror in 2001, some fellow Humanists began to label anyone who believed in "Right and Wrong" as "fundamentalists" and apocalyptic nuts. I have news for you: if you don't think there is any such thing as "good," I don't know on what basis you mean to calculate "the greatest good for the greatest number."

We have to work out, I think, some sort of amalgam position. If there is nothing to duty ethics, why bother to be utilitarian? We believe we have a duty to benefit other people, as many as possible. And we must safeguard our own souls (an old term for integrity, nothing more) in the process. We cannot patronize others by usurping their own decisions.

If we take all this into consideration, we will have a persuasive package. I believe it is difficult to preach morality because it always sounds condescending and, worse yet, heteronomous: the imposition of the will of one's masters (teachers, parents, government). Who doesn't chafe at that? It is practically one's duty, in the interest of preserving one's integrity, to rebel. But if we were to approach moral education the way Socrates, Aristotle, and Epicurus did, we could show that it is each individual's duty to seek his own interests. Who does not seek his own interests, to attain what will be good for him? And everyone should! It's no one else's job, that's for sure. The trouble is that people lack knowledge of what course of action would be most effective. Certain acts would benefit the individual in the short run but erode the social fabric (and one's own integrity), in the long run. The goal is fine, but there's got to be a better way. That's why Socrates said "Knowledge is virtue."

Kant spoke of our "categorical imperative" to do as duty dictates. If a thing is right, we must do it even at great cost. (Of course we all agree there are some such occasions, like giving one's life for family or country.) Any other basis for decision, Kant said, is merely acting on a "hypothetical imperative." Mere strategy. "Do you want to avoid rush hour traffic? Then I'd take this alternate route." He dismissed teleological ethics as no ethics at all, merely pragmatism in ethical clothing.

But I think we ought to show students, our children, prisoners, whoever needs moral education, that morality is a hypothetical imperative as well as a categorical one. Your duty is to pursue your own welfare. We all need you to do it! We as a society are counting on you! Likewise, I am responsible, duty bound, to seek my own benefit, improvement, personal growth and welfare. You can't do it for me. All of us are like musicians in an orchestra. Each must play his or her own music, not the other guy's, if the piece is to come out sounding right! I want to seek my own good. I want you to seek yours. And part of my good is to enjoy your friendship, which is why "It is more blessed to give than to receive." I get more of a kick out of it than you! Is that "selfish"? Who cares? Works out pretty well if you ask me!

Evangelists use the simile that gospel witnessing is "just one beggar telling another where to find bread." I am saying that is what moral instruction ought to be like. There will be a moral and practical unity between self-regard (including care for one's integrity, virtue, and moral growth), regard for others' welfare, which gratifies us, and one's duty to both. Everybody wins! Virtue takes practice. It is training to win the game, and it is a game no one will have to lose.

So says Zarathustra.

May 11, 2011

Truth, Justice, and the Post-American Way

For one thing, the current flap over Superman renouncing his American citizenship attests the wide and deep hold the Man of Steel retains on the public consciousness. He has, in less than a century, become a genuine myth. One cannot escape references to him in popular songs, TV commercials, on Seinfeld, and in political discourse. That's fine with me! I love the character and always have. In fact, if they ever had the epic battle kids speculate about, where Jesus squares off with Superman, I'd be rooting for…

In Action Comics # 900, Superman finds himself surrounded by stereotypical federal agents, at least one of them aiming a Kryptonite bullet at him. The trouble is that he had recently flown to Teheran in the midst of popular demonstrations and stood there between the crowds and the gun-toting thugs, a silent witness for peace, for twenty four hours. Then he flew away, the Ahmedinejad regime screaming "provocateur" behind him. The feds want to know what Superman was thinking. Did he mean to create an international incident? The U.S. Government wanted to disassociate themselves from his actions, lest he draw us into a war. But Superman understands this and indeed has already surmised as much. So he tells them he has decided to "renounce [his] American citizenship" to make it clear he is an extension of no one's foreign policy, no one's weapon or ambassador. I doubt that would be very reassuring to the government, either, as it would seem to make Superman a near-omnipotent loose canon.

The decision sure discomfited lots of Superman readers. There was hoopla in the media including DC Comics' message boards. Memories are short, but you may recall the same furor erupting briefly over the scene in the movie Superman Returns when Perry White tells reporters to find out if Superman, just back from five years of space exploration, still stands for "truth, justice, and…" The rest is dropped or drowned out. Was the script trying thus to omit the traditional connection of the hero with "the American way" (a tag line added to the Superman mythos as part of the 1950s George Reeves TV series The Adventures of Superman)? They did the same thing explicitly in the comics back in the post-Watergate "dazed and confused" 1970s, when patriotism was libeled as chauvinism; DC replaced Superman's slogan with "Truth, Justice, and the Terran way," whatever that might mean. Many were sure the omission was designed to denote the hip post-Americanism of liberal "world citizenry." Maybe so. Is it now the real meaning of Superman renouncing citizenship? I think so.

The narrative motivation of Superman's decision makes sense. I mean, the story logic. But that is a different thing from what the writers had in mind by introducing the element, which they were by no means obliged to do (unlike, for instance, the question of whether Superman would eventually marry Lois Lane, which had to be addressed sooner or later). I think it is a safe bet that the renunciation of Superman's American identity is a political statement by people who think America is not good enough to have Superman represent it anymore. One reason to think so is the liberal agenda of DC Comics, especially under the regime of Dan Didio, who has repeatedly and unwittingly made clear just what a sick joke Political Correctness is. For instance, DC pursued his explicitly stated goal of increasing so-called "diversity" by killing off various iconic characters to replace them with minority versions. In this case it was so blatant that the writers clumsily backed into rank stereotyping. Ted Kord, the Blue Beetle was shot in the head and replaced by a Hispanic youth. The Beetle becomes the Cucaracha? Vic Sage, The Question, already renamed "Vic Szasz" to make him less of a WASP, dies of cancer (not even in battle!) and is replaced by a Lesbian, who is sleeping with the steely-thewed Batwoman (Bull Dyke stereotype). Ray Palmer, the Atom, vanishes for a while, to be replaced by a "typically" diminutive Chinaman. Worst of all, The Spectre, abandoning his previous mortal hosts, takes up with a new one, a freshly murdered African-American police detective. Get that? The black man becomes The Spook! It wouldn't be this bad if the whole thing were meant as a parody! When a company that engages in this sort of political ineptitude pulls the phony issue of Superman's citizenship out of their rear, you have to assume it's because of an elitist, Left-wing disdain for America.

It's not as if this kind of thing hasn't happened before. It was even more overt in the case of Marvel Comics' Captain America, where it has happened three times, though perhaps with more forgivable reasons. In the 70s Cap became disillusioned with the corrupt, corporate bosses who "really" run America, so he ditched the red, white, and blue and donned a mediocre costume and called himself Nomad since, like the Son of Man, he felt he no longer had a place to lay his head. A man without a country. Eventually he got over it and resumed the Captain America persona. In the mid-eighties he was fired as Captain America by the government who replaced him with a bigoted roughneck named John Walker, who, in the guise of the Super-Patriot, had previously fought Cap. The latter now took on the identity of The Captain, period, with a costume black where his old one had been blue and with no star on his shield, no "A" on his cowl. The stripes on his chest, formerly vertical, were now horizontal, and an empty black space gaped where his chest star would have been. Again, he and the government soon reconciled, and Walker became the U.S. Agent.

The next decade saw a reboot of Captain America in which we learn that Cap did not spend the years between World War Two and the present locked cryogenically in an iceberg till rescued by the Submariner and the Avengers (the traditional version). Rather, his eternal youthfulness was the result of the Super Soldier Serum that gave him his might and prowess. But where was he for all those years? Seems that President Truman had summoned him to the Oval Office, explaining his plan to nuke Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and expecting his support. Horrified, Cap refused, and Truman sicced the goons on him and had him injected with drugs. Under their influence he lived the next decades in Pittsburgh as an amnesiac steel worker until an old war veteran, a co-worker, recognized Cap and gave him his shield, which the man had kept for him all these years. Captain America lived again, no thanks to his ungrateful and intolerant masters in Washington.

It is too bad that, as Nomad and The Captain, he did not contest the red, white and blue, yielding his colors to those unworthy of them. In the same way, to depict Superman as renouncing his American citizenship is not to bemoan America's sometime failure to live up to her own ideals. It is worse: it is to reject American ideals as unworthy. To reject and to hate one's own identity as an American is neurotic, very much like hating your parents. You may even have some kind of reasons for doing so, but unless you go the second mile and reconcile yourself with the rock from which you were hewn, you will remain alienated not only from your roots but from parts of your own psyche, your own self. It is unfortunate that Dan Didio and company are thus degrading Superman as a symbol as well as that for which he stands.

So says Zarathustra,

Awaiting the Superman

April 3, 2011

What Is Wrong with the Word of God?

What is it that disturbs many of us when we hear politicians call for laws based on the Bible? We fear a neo-Puritan theocracy which would stifle dissent and persecute dissenters. The Bill of Rights is effectively scripture for most of us and we can see the handwriting on the wall (or rather the erasure of it!) if Bible zealots took power.

A quick clarification: there are many in government who revere the Bible as the inspired Word of God and yet realize they serve all the people, not just co-religionists. Surgeon General C. Everett Coop is a shining example, and his lack of partiality got him in considerable trouble with fellow evangelical Protestants when he refused to ignore the plight of Gay Americans as some wanted him to do. I know better than to allege that all who believe in the authority, even the inerrancy, of the Bible would feel obliged to force it on everyone else. But there certainly are some. I think it is not much of a caricature to call "Christian Theonomy" or "Christian Reconstructionist" advocates a kind of Christian Taliban. Is it likely they might one day rise to power? The only way I can see it happening is via a military coup, given the presence of many Christian officers who openly proselytize among their vulnerable troops. Only recently have their extensive evangelism efforts come to public notice. But even such a government seizure could never last. Everybody else would be out on the street, daring the National Guard to shoot them, which they would never do, and the plotters would be left holding the biblical bag.

So there are scary partisans for making scripture normative for the rest of us, though not much chance of it ever happening. But what exactly are we afraid of in such a scenario, often raised like a spectre by Secular Humanist fundraisers? I think there is a significant confusion here, though in the end I admit it may not matter much. My impression is that those who fear a Christian theocracy reason (correctly) that an ethos derived simply from (ostensible) divine revelation is going to be based on arbitrary assertions from some weirdo in a trance. "Thou shalt henceforth walk only on thy hands!" "Thou shalt marry thy goldfish!" But that is not usually the problem. There have been rare examples of this kind, but usually they are what Albert Schweitzer called "interim ethics" designed for an emergency, short-lived situation until the imminent End of the world as we know it. The whole point is that, for Chicken Little, it is no longer business as usual, and so what "works" in the public, long-term society is no longer relevant. Certain emergency measures (quitting your job, fasting, celibacy—or license!–, giving away possessions, the Ghost Dance) are required, perhaps as tokens of lay-it-on-the-line, put-your-money-where-your mouth-is faith, either to demonstrate your worthiness to survive the Final Judgment or even to bring it about. Or a prophet (e.g., Jacob Frank) may reveal that the New Era has commenced, but as yet in secret, in the form of a mustard seed, waiting for the full, unmistakable fulfillment which every eye shall see. In the meantime, new "eschatological" behavior (usually licentious) is allowed and encouraged (holy orgies, etc.), but in secret, lest the unenlightened worldlings find out and compound their sins by martyring their superiors whose ways they fail to understand. Often these sects' belief that they sit on the cusp of the future leads to their disbanding, persecution, or collective suicide (Jonestown, Waco, Heaven's Gate). Their behavior is a repudiation of our ordinary world, and the universe is not big enough for both. So if the outward, public world will not oblige them and go away, the sect will go away. This world is no longer their home, so, one way or another, something's got to give. What I'm saying is that "revealed" commandments that would alienate us from the common life of our species have no lasting value. No one who espouses them (or secretly practices them) is likely to get or to keep power in America.

But that is not usually the problem with ostensible revelations that fanatics would like to impose. Oh the laws they promote are outrageous enough: stoning evangelists for nonbiblical religions, killing homosexuals, executing kids who curse at their parents, reinstating slavery, etc. It's just that these are not the rantings of manic oracles who ought to be in liturgical straightjackets. No, the problem is that scriptures merely preserve the legislation of communities of the distant past, societies in which these statutes once seemed quite reasonable. And the world has changed so much, very many of these archaic laws simply do not fit anymore. I don't mean to be a total relativist, implying that it used to be fine and dandy to stone adulterers and transvestites to death, or spirit mediums with their customers. It remains monstrous in any case to think of enforcing such arrangements in our day.

It does appear that certain distinctly ritual laws (Martin Noth called them "apodictic laws" in the Old Testament, Ernst Käsemann "sentences of holy law" and Bultmann "law words" in the New) were the direct product of priests and prophets "giving torah (instruction)." This had to do with acceptable sacrifices and prohibitions of ritually unclean food, ceremonially "impure" sex acts, etc., not morality. These varied from culture to culture yesterday as they do today, since all cultures have analogous mores, often so taken for granted that we do not even notice them. Not surprisingly, civil and criminal laws, even ethics, resemble one another quite closely the world over, despite infinite differences in detail and definition. This is no mystery. They reflect the common human nature of all mankind. We are social animals, and there are certain actions that cannot be allowed if we are to have a livable society. Certain ground rules must be laid down and reinforced by education and peer pressure. We try to program into children a super-ego, the disembodied voices of neighbors and parents, and if it works, we call it conscience. And to give them a good scare, we propagate the fiction that God or gods prescribed all these laws (plus customs, manners, etc.) and will punish violators even if no other human being catches them in the act.

Accordingly, every scriptural collection of laws merely reflects the standards of the surrounding environment. The Pentateuch seems heavily based on Assyrian law. The Koran encapsulates seventh-century Arab legal traditions, just as the Taliban enshrines local tribal law. None of it looks like it is even supposed to be "revelation" in the usual theological sense: information human beings couldn't have guessed. The "divine inspiration" business is an afterthought, a sanction. But once it is added on, naturally, it becomes very difficult to amend the laws thus made into an idol. And indeed, that might be said to be the whole point.

But eventually some updates need to be made. In the case of Jewish law, the major task has always been to apply the text to new situations not mentioned in the scripture. But back in ancient Israel/Judah, they did not hesitate to change and update the Torah. Just compare Deuteronomy ("Second Law") with the earlier codes contained in Exodus, and the still later provisions of the Priestly Code with those of Deuteronomy. All were attributed to Moses, and that legal fiction seemed to do the trick.

If a group rejects the old code completely, it is usually to make way for something new and different, and a new religion results—on purpose. When the Buddha rejected the Hindu scriptures, it meant he had started a new faith. Even so, when Mahavira rejected them, he hung out the shingle of Jainism. And when Marcion of Sinope cut loose the Old Testament, he was declaring Christianity a wholly new faith.

This total separation is the mirror image of the anguish of the members of a faith whose hierarchy has ordered major changes in the tradition without officially starting over. After the Second Vatican Council, many traditionalist Roman Catholics stumbled at the supposed fact that the old ways had been divinely decreed—but had now been set aside by divine leading! How could it have once been a terrible sin to eat beef on Friday but not anymore! Was Aunt Mimi sentenced to Purgatory for doing it but you would not be today? Fundamentalist evangelist Lehman Strauss, invited to Sunday dinner where pork was served, when asked to say the blessing over the food, prayed, "O Lord, if you can bless under grace what you cursed under Law, then bless this meal!"

Thus the business of updating is tricky and must be subtly done. The Koran contains the warning that "If Allah abrogates a verse or causes it to be forgotten, he is able to replace it with another like it or even better." The redactional changes Matthew made to Mark's gospel must be seen this way, too. Matthew (19:9) wasn't trying to give a more "accurate" account than Mark (10:10-12) did of what Jesus said about divorce, adding a clause Mark must have forgotten; rather, he was amending the sacred charter of his Christian community, trying to deal more leniently with sexual impropriety and divorce. But you see what difficulties it created for theologians: a contradiction in scripture! And here come the ridiculous harmonizations.

In modern secular societies like ours, the laws are regarded as a man-made social contract. But we realize that laws which can change as the wind blows, or at the whim of a dictator, are not real laws at all (since the humans who cook them up and then disobey them at will are superior to them, not subordinate to them). Thus we regard our Constitution as if it were infallible scripture, not to be set aside with impunity or for anyone's convenience. We even have the same sort of hermeneutical debates over things like "authorial intent" and the "intent of the Founders" that theologians have in the interpretation of the Bible. But we have the advantage of knowing that mere humans wrote the thing and that it may need updating. But it is not subject to just anyone's whims to update and alter. The Constitution has become reified, that is, possessing its own gravity and substance, preceding the existence of any American citizens. It was here before we were. It is a human creation, but not our creation, and this gives it a gravitas equivalent to a divinely inspired scripture but without the paralyzing superstition that plagues theocrats whose chapter-and-verse adherence to their superannuated texts is eerily like the cultists of whom one hears every so often who stand vigil around the stinking corpse of their leader, expecting him to rise from the dead. Get real: he's gone. History has devoured him. History has devoured the Koran, the Sharia'h, the Priestly Code, and the Code of Hammurabi. Once the imprimatur of divine origin lent authority to the law codes; now it reduces them to grotesque preserved corpses like Lenin's on display for pious Communists to venerate in the Kremlin.

So we can amend our laws, free of the pretense that they were written in stone by Jehovah's fingernail. There is nothing to explain, no need to harmonize. But it is purposely hard to update them, because we want the law to continue to exist as something greater than any government or individual. Thus we have an elaborate process of state ratification. When we are done, it still will not seem fly-by-night. We will still stand before it with awe and freely yielded obedience, like the ancient Israelites agreeing with Moses to make the Book of the Covenant their own. But without illusions.

By all means, let us glean what wisdom we may from the pages of ancient scriptures, one and all. But we must not allow them to chain us to the past, which is, in religion and theocracy, only a futile pretense that the God who prescribed them still lives, that he has not long since died of extreme old age.

So says Zarathustra.

March 5, 2011

Heavenly Head Trip

Remember in the sixties and seventies they used to debate whether hallucinogenic drugs could bring about the same effect as years of yogic meditation? Some claimed there was no real difference, and this seemed to them an apologetic on behalf of drug use. In fact it sort of implied that the Hindu or Buddhist who spent all that time in the lotus position was just wasting his time. "Did the saints owe their visions to some biological short-circuit which caused them to experience spontaneously what LSD cultists achieve with a chemical?" (William Braden, The Private Sea: LSD & the Search for God, p. 23). Others resented such talk, holding that, as Paul Tillich said, "There can be no depth without the way to the depth. Truth without the way to truth is dead" (The Shaking of the Foundations, p. 55). The desired end had to be the culmination of a process of spiritual training, the practicing of "virtue" in the sense of a power or a skill. You can't just use drugs to say the magic word "Shazam" and turn immediately from Billy Batson into Captain Marvel. Or if you do, you won't know what to do with the powers you gain! That is why you had, for instance, to devote much study to the Tibetan Book of the Dead or it would do you no good to hear it recited on your death bed. You just wouldn't know what to make of what you experienced. Same with the Jewish story of the Four Who Entered Paradise. Four would-be mystics embarked on an exercise in Merkabah meditation. The Merkabah was the throne chariot of God which Ezekiel had seen in chapter one of that prophet's book. They believed that by meditating on that chapter of scripture one could recapitulate that vision and gain a glimpse of the heavenly throne room. When it was all over, only Rabbi Akiba came out of it safe and sound. Of the other three, one went insane, another became a heretic, and the last dropped dead! It was a question of being prepared for the experience. (See Gershom G. Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, p. 52; Alan F. Segal, Two Powers in Heaven: Early Rabbinic Reports about Christianity and Gnosticism, p. 10).

But recent neurological research has tended, as I understand it, to vindicate Freud's view of mystical experience as an imaginative return to the "oceanic feeling" of the womb. It appears that meditators are managing to affect the temporal parietal lobe of the brain, which contains the mechanism that kicks in early in a child's life, enabling him or her to distinguish between self and others, self and world. Meditation temporarily disables this gizmo, returning the meditator to the experience of primordial Oneness of infancy. This implies at least two surprising things. First, like the use of LSD (which, in case you're wondering, I've never done), "real" enlightenment experiences seem to be chemical in nature, the result of brain chemicals acting in a special way. Second, this means that it is superfluous to seek some higher, metaphysical explanation for what is going on in experiences of Satori, Samadhi, Moksha, what have you. Occam's razor dictates that there is simply no reason to add redundant, fancier explanations when a simpler one will do. And now we've got one.

Now that we know what is going on in enlightenment peak experiences, how shall we categorize them? Why would one seek them, and is it somehow even morally incumbent on the serious person to seek them?

The great ninth-century Advaita (Nondualist or Monist) Vedanta mystic Shankara believed that the experience of unity with Brahman (recognition that it was always an error to perceive oneself as being different from Brahman) was the final penetration of the veil of maya, illusion. One thus attained the highest degree of knowledge and of reality. One attained unto the divine existence as Satchitananda: Being-Consciousness-Bliss. Commenting on this mystical ascension, Huston Smith (the great comparative religionist) argued that the "bliss" aspect was secondary to the ontological (being) and epistemological (knowing) aspects. He believed that it was only popular, emotional mysticism (bhakti) that made bliss number one (Forgotten Truth: The Primordial Tradition, pp. 3-4). I would venture to suggest that the recent brain-science discoveries tend to support the "popular" approach, since Samadhi turns out to be a brain-chemical-induced head trip, becoming "blissed out" as the devotees of seventies guru Maharaj Ji called it. This means the experience of enlightenment is after all little different in character from the drug trip. Both are thrills, though the traditional meditators are paying quite a lot more for the ticket. As for the trippers, remember what the Reverend Billy Saul Hargis used to say: "Most Protestants go coach!" In other words, any mysticism is all about thrills, but drug induced mysticism is cheap thrills.

Twelfth-century critic of Shankara, the Visistadvaita ("Qualified Nondualism") theologian Ramanuja held that Shankara was not experiencing what he thought he was during his mind-blowing experiences of nonduality. He thought Shankara was not encountering pure divine Presence, but rather merely temporarily breaking down the cognitive barriers that distinguish one from others and from God, whom Ramanuja, by contrast, understood as a personal deity. Yes, there is a divine substance or ground out of which everything is formed by God (including his own individual personhood), but to experience it directly in meditation is more like a dive into a pool of prime matter, not an ascent to the spiritual summit. It is retrograde, though harmless enough. Guess what? Ramanuja, too, would seem to have been vindicated by modern neuroscience. The mystic is temporarily erasing the defining boundaries of individuality and personality. We go Ramanuja one better since we can pinpoint where in the brain those lines are drawn and erased.

But wouldn't a Nondualist mystic like Shankara or Meister Eckhardt know what it was he was experiencing? After all, it was his experience, not ours! "In every case, – whether the experience comes unheralded or whether it is produced by drugs or Yoga techniques, – the result is the same… The experience seems overpoweringly real; its authority obtrudes itself and will not be denied" (R.C. Zaehner, Mysticism Sacred and Profane, p. 199). "Mystical experiences… are face to face presentations of what seems immediately to exist." (William James, The Varieties of Religious Experience, NAL, p. 324). But remember this caution:

The fact is that the mystical feeling of enlargement, union, and emancipation has no specific intellectual content whatever of its own. It is capable of forming matrimonial alliances with material furnished by the most diverse philosophies and theologies… We have no right, therefore, to invoke its prestige as distinctly in favor of any special belief. (Ibid., p. 326)

Mystics are enjoying the fruits, not inspecting the roots. And the simple fact that they take their experiences (very similarly described!) to prove the truth of various contradictory theologies implies the seers do not in fact simply perceive some self-evident truth. By contrast, they are making the error Derrida called that of "Presence Metaphysics," the failure to see, in the blinding light of "direct" experience, that the phenomena are already products of subconscious construction, definition, and inference. There is a man behind the curtain.

Agehananda Bharati, a double hybrid, as he was both half Indian and half Austrian and both a trained anthropologist and a Hindu monk, was sure that the non-dualist experience, the only kind he was willing to dignify with the term "mystical," was purely "hedonistic; the canonical scriptures talk overtly about delight and pleasure." "There are no ontological implications" (The Light at the Center: Context and Pretext of Modern Mysticism, pp. 29, 42).

Is the experience merely fun? I think it goes beyond that. I think we can call the mystical experience wholesome. It may even have moral relevance in that it stimulates momentary ego-transcendence, a perspective that helps us think of others and their welfare. But I do not think we have an obligation to seek it out. If the experience were truly a union with Ultimate Being, it might be argued that we have a categorical imperative to seek it, to become what we are, to awaken from a dulling dream of mundane consciousness. But it seems it is not a case of that. It seems that, a la Ramanuja and Freud and Bharati, Satori is pretty much a temporary vacation. The goal is that of H.P. Lovecraft in his fiction: "to achieve, momentarily, the illusion of some strange suspension or violation of the galling limitations of time, space, and natural law which for ever imprison us and frustrate our curiosity" ("Notes on Writing Weird Fiction," emphasis mine). It is not business but pleasure. It seems to amount to a drug trip whether or not one is ingesting "substances." The right hand and left hand paths would seem to be one. And they don't lead nearly as far into the distance as we used to think. It is to subsume the Sacred underneath the category of the Profane. That might not be a bad thing, at least according to those of us who think there is a reality to the Sacred but prefer science to supernaturalism.

So says Zarathustra.

February 2, 2011

The Unbelievable and the Inconceivable

As I reflect upon a lengthening career refuting implausible religious claims, it occurs to me that it is valuable, for both evangelists and their nemeses, to draw a distinction between two types of claims, both of which leave unbelievers unpersuaded, but for entirely different reasons. Actually, I guess I am saying this for the benefit of religion promoters rather than for my own advantage. At least it might bring a bit more clarity to the debates.

As I reflect upon a lengthening career refuting implausible religious claims, it occurs to me that it is valuable, for both evangelists and their nemeses, to draw a distinction between two types of claims, both of which leave unbelievers unpersuaded, but for entirely different reasons. Actually, I guess I am saying this for the benefit of religion promoters rather than for my own advantage. At least it might bring a bit more clarity to the debates.

First, evangelists and apologists make claims that might be true, but for which there is no evidence, or nowhere near enough. The existence of God and the resurrection of Jesus would fall into this category. It is by no means impossible that these tenets may be factually correct, but where is any serious reason to think so? Obviously (even if they are true!), most people who hold these doctrines do so because of early instruction and continued peer pressure. The beliefs in question may well be true even though people believe them for inadequate reasons. They would just be lucky, as opposed, say, to Buddhists or Shintos who believe what they believe for the same lame reasons but (if Christians are right) happen to have stumbled into the wrong thing. But once one presses the claims of one's faith onto outsiders, or once one begins to question the adequacy of one's own too-easily accepted creed, things begin to look different. I believed in the resurrection of Jesus because I was told it was true and assumed those authority figures, older than me, knew what they were talking about. Then I learned all about apologetics, with its sophisticated arguments. The next stage was seeing through those arguments, discovering with bitter chagrin how very shoddy they were. They are not even strong enough to put the unbeliever on the defensive. He has no problem, as if there were no viable naturalistic alternative to the resurrection. I will not repeat here what I have said and written so many times before.

The existence of a powerful, never-aging divinity invisible to mortal eyes is another of the same kind. It is not a foolish notion, but what reason can there be to accept it? It is like belief in space aliens or Atlantis. Not laughable, not at all. But why on earth credit it? There would still, regrettably, be room for doubt even if the Martians or the Venusians were to pop in and say hello, with all requisite special effects. Because of the special effects. It is easy to be gulled. Even in the Hellenistic period of the New Testament, there were plenty of conjurers and charlatans bilking the credulous into new religions. But there were also careful individuals who refused to be won over (taken in) by signs and wonders. These feats seemed "too good to be true." Even the gospels condemn "lying wonders."

Why do miracle-mongers try to short-circuit the natural means of convincement, namely, rational argument and persuasion? "I, too, brothers, when I came to you, I did not come armed with excellent rhetoric or wisdom as I announced to you the witness to God. I had decided that while among you I should offer no other answer to any question, but Jesus-Christ, and him crucified. And it was in weakness and fear and much trembling that I was with you, I freely admit, and my speaking and my proclamation were not marked by sophistical rhetoric, but by a definitive display of spirit and power. Otherwise you should have placed your faith in human wisdom, not in divine power" (1 Corinthians 2:1-5). They say faith in divine revelation is the only way to rise above the deafening clash of merely human guesses and speculations. But faith does not trump argumentation; it only cheats, tearing up the rules and claiming victory, like Buck Strickland playing golf on King of the Hill. That is what they are saying, albeit with euphemisms. That is the sin of faith. You're just deciding to believe something because you want to, without sufficient reason, and then you pretend you know. It is what Francis A. Schaeffer used to call an "upper-story leap" when he thought he saw other people doing it.

But there is worse. There are the claims of religion that are inconceivable, unacceptable on their face. Notions so unreasonable that no evidence brought forth could help. As Voltaire (I think it was) observed: if I tell you I will now prove two plus two equal three by making a ball disappear from my outstretched palm, and I do in fact make it disappear, guess what? Two plus two does not suddenly start making three. The one has nothing to do with the other. The thing Voltaire's charlatan seeks to prove is absurd on the face of it, and nothing will change that. "Even if we or some angel from heaven should proclaim to you some message of salvation besides the one we proclaimed to you, let him be excommunicated" (Galatians 1:5). It won't start looking truer just because there's an angel endorsing the nonsense. I am thinking of claims of divine Providence amid the seeming chaos of the world, of the inspiration of the Bible, an eternal Hell of torment, and (of course!) the Trinity. It's not that these claims are known not to be true. Rather, it is that they could not be true, they make no sense.

Is God in hands-on control of the world? The believer says he is, despite appearances. He even admits he cannot imagine an atrocity so hideous as to debunk that claim. "So your loving God did not lift a finger to save Jews from the Holocaust, but he's still loving and provident? Suppose the whole population was wiped out by AIDS or nuclear weapons; would that convince you no loving God is in control of things? No? Then I'm afraid I no longer have any idea of what we are arguing here! What can be meant by the 'love' of such a being?"

Can the righteous Father-Creator of the human race possibly be pictured as assigning individuals, in fact most who have ever lived, to a never-ending ordeal of suffering in Hell? Not even the loathsome Hitler, Stalin, Genghis Khan, or Pol Pot could deserve that. To believe otherwise is to redefine God's "righteousness" as compatible with an avenging sadism worthy of the very devils he would be tormenting. C.S. Lewis once wrote: "But there is a difficulty about disagreeing with God. He is the source from which all your reasoning power comes: you could not be right and He wrong any more than a stream can rise higher than its own source. When you are arguing against Him you are arguing against the very power that makes you able to argue at all; it is like cutting off the branch you are sitting on." (Mere Christianity, pp. 52-53). Uh, you think this is an argument for your view, "Jack?" Turn it around the other way: if your own moral sensitivity is higher than that of your supposed Source, the odds are good that He is not your Source.

Look, if he's going to impose a sentence on the damned souls against their will, why not sentence them to sanctification? That way, everybody winds up, forgiving and forgiven, in heaven. And the minute you begin back-pedaling to argue that the damned choose Hell, you are admitting the outrageously nonsensical character of the whole silly business.

Biblical inspiration is another ultimately meaningless claim, based as it is on the postulate that scripture is infallible only in its plain sense as derived from a straightforward, exoteric reading. It becomes meaningless as soon as, in order to sidestep a difficulty, the apologist for inerrancy begins arguing that the dubious text must be taken in some less than literal way, that it is but an "apparent" contradiction. Those are the worst kind, since they in the very same moment vitiate the fundamental axiom of "apparent sense" infallibility. Look elsewhere for a consistent theory. This one is gibberish from the word go.

And the Trinity! Need one say more? It is fine to fall silent in reverent contemplation of a sublime mystery transcending human ken, as when physicists admit that light behaves sometimes like a wave, sometimes like a particle, so we cannot really hope to describe it. But when it comes to the Trinity, I am going to need quite a bit of evidence to convince me we have a real paradox on our hands, and not just a bad theory resulting from the ancients trying to cobble together a theological compromise enabling all parties in the debate to agree with their favorite parts of it.

Add the so-called "doctrine" of the atonement. It confuses torts with crimes and imagines that an innocent man can pay with his life's blood for the wicked deeds of wicked men. This is the beginning and revelation of the righteousness of God? I know of ten or a dozen models for explaining the atonement, and I will confess not one makes any real sense of it to me. Can you make any sense of it? Come on!

You can ask me to accept the "fact" that Jesus rose from the dead, and I must shake my head, unable to oblige. I cannot pretend the case is a good one when I know better. I agree, it might have happened, but if so, the information is beyond recovery, short of somebody inventing a time machine. But if you ask me to believe in the saving death of Christ, the superintending love of God, a Hell compatible with his ostensible mercy, etc., heck, you might as well be speaking in tongues. There is just nothing to see there.

I say there are these two distinct categories of unacceptable arguments, but in fact they fade off into one another as follows. If you step back to look at the big picture, you see that on the one hand God is said to hold us responsible for accepting the one true, saving belief. On the other he has not allowed us sufficient evidence for such belief—or even defined it adequately enough that we can grasp what it is (the Trinity?). It is grossly unfair. And that cannot be predicated of the sort of deity Christianity claims to represent. Again, the claim is torn apart by a jagged fault of self-contradiction.

Oh what a tangled web we weave when first we practice to believe!

So says Zarathustra.

January 2, 2011

Resolutions and Revolutions

Why do our New Year's vows, so heartily and seriously resolved, end in defeat? And why did we more than half expect them to? Perhaps the second question is the answer to the first: defeatist self-fulfilling prophecy. But I suspect there is another reason, namely the cyclical nature of the calendar year. We know we will end where we started. What first seems a brand new beginning will wind up running out of gas and slowing to a halt, trailing off to silence. And then we will renew our vows again. But we will not get anywhere with them then, either. Because the whole thing is the eternal return.

If our earth really became unchained from the sun, as Nietzsche once posed, it would mean we no longer had any central focus to orbit. This was a metaphor for the lack of a central objective truth upon which to base normative moral or religious thinking. It was a parable of the glad knowledge of Nihilism: not the denial of meaning so much as the free creation of meaning. I for one am happy to affirm that slipping of the solar apron strings!

But what, then, of cyclicality? What of the round of repeating seasons? Imagine the earth like the moon on the seventies Sci-Fi program Space 1999, having escaped its geocentric orbit and drifting out through and beyond the Solar System. The inhabitants were still able to count hours and days and weeks and months and years, but these quantifications had assumed the character of artifice. They no longer recorded arrival at a scheduled juncture, at an accustomed niche in the year or tick on the clock. One might, stranded in space for a long time, look back on experiences a year before, but it would be an illusion. The present moment would no longer correspond to an earlier counterpart in the orbit of the sun. Time would have switched from cyclical to linear. History would be like sentences that lack punctuation or even syntactical sense. We would be advancing into raw existence, unprecedented and without meaning-lending reference to anything that had gone before, motion into a future completely open and therefore unknown, no landmarks or pointing signs informing us that we have been this way before, because we will not have.

In such a framework of free fall, soaring flight into an empty void, one might make resolutions that one might keep, because no cycling calendar would insist on bringing us back to square one to start the identical dance again.

But as it is, Siva dances his infinitely complex choreography, with the Universe as his partner, until they both tire and decide to sit the next one out. And then the Manvantara, the Great Night, settles over the cosmos—until it starts again. And that is what it does: it starts to repeat itself, and so do you. You will resume the circle dance and get precisely nowhere.

But maybe there's a lesson there. Maybe you are disappointed because there is no way off the merry go round, and you mistaken think there should be. But if there were, that would be the end of the ride. The merry-go-round is a passing parade of fantasies and fantastic sights. There is nothing to see once the ride stops, unless you want to start it again. And we do. You are not trying to reach a destination when you pay for your ticket and hop aboard the ride, are you? The merry-go-round is not a train. You are only there for the ride. I suspect life is like that. And I'm enjoying the ride. I'm in no hurry to get off.

Part of that ride is making New Year's resolutions, and part of it is realizing you haven't kept them. What of it? It's the ride that counts.

So says Zarathustra.

December 5, 2010

The Idea of the Unholy

In the aftermath of last month's Zarathustra Speaks essay, about the meaning and value of Halloween, at least as I understand it, my wife Carol got herself involved in a fruitful conversation (frustrating as it may have seemed at the moment) over the ostensible sacredness of Halloween. She was discussing the matter with a columnist for our town newspaper, a man active politically and religiously. Carol and I share many of his conservative political views but not his theological opinions. He sure does not share ours! But I admired his consistency. He not only dismissed Halloween as unimportant, he threw Christmas and Easter into the dustbin along with it! All these holidays, he averred, had pagan origins, and Christians ought not have anything to do with them. Of course he endorsed the idea that the birth, death, and resurrection of the Christian savior were something to rejoice in. But that's no reason for all these expensive occasions. (No, he didn't mutter "Bah! Humbug!")

I thought at once of a conversation I had nearly twenty years before with a Southern Baptist minister whose toleration, cultural pursuits, and sense of humor defied the stereotypes. A fine fellow. He mentioned to me that the idea of the liturgical year left him cold. It seemed like a pointless charade to pretend, during Advent, that Christ is coming to us in some way he hadn't been the day before Advent starts when it is some other season of the church calendar. What is the point? he reasoned. Don't Christians believe Christ came once, made a difference in the world, and that ever since it has been our responsibility to get busy continuing his work? In the meantime there is no reason to waste time pretending that we are going down the Time Tunnel to participate in the events of redemptive history as if they were not already fully accomplished. Roman Catholics have always maintained that in the weekly sacrament they are "re-presenting" the one-time sacrifice of Jesus to provide ever-new opportunities for us to tap into the grace dispensed then. Protestants seem not to get this, maintaining to the contrary that the Catholic Mass is a vain and insidious attempt to offer the sacrifice of Jesus Christ all over again, as if it had not really sunk in, done its thing, the first time. Else why would all this repetition be necessary? (That, we may note, is precisely the logic of the Epistle to the Hebrews when it argues that the old Levitical sacrifices were well supplanted by the cross of Christ. They must not have worked if they had to repeat it frequently.

Thus Protestants lost any sense of Sacred Space and Sacred Time, those universal, archetypal features of the religious instinct underlying the religious expressions of all cultures, ancient and modern. These elements Protestants sought to excise from religion with the slashing knife of Rationalism, the weapon they wielded so effectively against Medieval Catholic dogma/superstition (if one could tell the difference, hence the need for the house-cleaning). No more Virgin Mary or saints bridging the gap between heaven and earth so densely as to require Air Traffic Control. Let Jesus, mighty as Atlas, uphold the vault of heaven by himself. The Eucharist did not change the substance of food into the body and blood of Christ. "Hoc est corpum Christi" became laughable hocus pocus. Esoteric meanings were banished from scripture, which must henceforth be read by strict secular methods even if divinely inspired. This process of rationalizing is what Durkheim called "the disenchantment of the world."

Once Protestants had dispensed with the rest of the forest of mediators, the Jew and the Muslim, one may suspect, looked on from the sidelines, betting on how long, if ever, it would take the Protestants to realize that Jesus was as little necessary as a go-between as Mary and Saint Christopher had been. In fact, it wasn't very long at all before advancing rationalism led Unitarians to reject the Popish "mystery" of the Trinity and to return to Ethical Monotheism. And then into Religious Humanism, and then to Paul Beattie, who famously proclaimed "Secular Humanism is my religion." But by this time, only a few runners were left at the finish line of the race to reason. Most of the rest had long since fallen by the wayside, huffing and puffing the increasingly thin theological air. The Baptists lie maybe half-way. In a sense, they had already succumbed to rationalism. It isn't immediately apparent because they retained so much belief in supernaturalism.

In an important sense, no room for Mystery remains in Baptist, Presbyterian, Methodist Protestantism, what one might call "the lowest common denomination." It is the result of the belief on "propositional revelation." That is, in scripture God has disclosed privileged "information unavailable to the mortal man" (as Paul Simon sang). It is as if a new telescope, or even space visitors, had imparted vital new information. Picture a cure for cancer or the news of an approaching asteroid. Very important, life and death information. But sacred? If he existed, would Superman be holy? Or just important?

Protestants are logocentric, totally into the cognitive aspect of religion. They have information, and they mean to act on it. And to talk about it. Endlessly. That is why the pulpit, the lectern, is central in their churches, with the communion table off to the side. The sacraments are mere vestiges. Fundamentalists are as impatient with them as Unitarians, and for the same reason. Both are interested only "the facts, just the facts, ma'am." They just have different sets of ostensible facts, albeit held with the same zeal. You may be sure Baptists would be baptizing nobody if they didn't read the command to do so in scripture. Likewise holy communion.

Thinkers like Friedrich Schleiermacher tried to isolate the nature of religion, to delineate the unique character of religious experience. What is piety? What is uniquely religious about religion? It cannot be ethics, as Kant maintained, because religion adds nothing to morality and is not constituted by it. It is a mystery unto itself. Nor can it be equivalent to knowledge. Something eerier and more spine-tingling, something more fulfilling to the soul is going on in religion. No, piety transcends, while including, both ethics and knowledge. This set of distinctions came in quite handy when the Higher Criticism demonstrated that the Bible could no longer be relied upon to dispense hitherto-hidden knowledge as believers once imagined. Without the old belief in supernatural revelation of the information necessary to be saved, religion could still go on, basing itself, as it always should have, on the basic experience of awe and wonder, of humble receptivity.

But today's fundamentalists still imagine themselves the recipients of revealed knowledge ("propositions"), which they take very seriously, anxiously striving to convey it to everyone around them (an amazing irony, since they inhabit a culture already thoroughly familiar with it). It is all cognitive. "Mystery" for them refers not to conditions, entities, feelings transcending reason, but merely to problems the solution to which God has not yet provided (but he will in a vast seminar once we reconvene in heaven!). Sacred Time? Sacred Space? Cyclical reliving of the holy past? These things are mere charades to the rationalist Protestant, as they would be to the political scientist or the economist or the biologist. Such religionists believe in God, but not in the Sacred. It is peculiar. It is ironic. It is tragic.

Schleiermacher believed in religious experience, but not in revealed knowledge. Oh, one might (indeed must) infer certain things about God from our experiences of him. But one could not dogmatize. He called himself an "agnostic pietist." He did not look beyond the limits of the normal and the natural to see God at work. Instead, he said, "To me, all is miracle." One might say that rationalistic fundamentalism has erased the Sacred, making even revelation essentially secular: vital information, like news about global warming. In turn, Schleiermacher erased the secular, making everything, all experience, sacramental: material conveyances of spiritual experience. He was influenced by Spinoza, though he didn't think he had followed Spinoza all the way into Pantheism, the doctrine that all things are faces/revelations of God, who is their inmost nature. The religious person learns to read the rarified aura of divine holiness in all things, where the unenlightened see only the mundane, only junk punctuated with fool's gold.

Pantheism was Stoic in origin. These ancient Greek and Roman philosophers taught that Zeus was not a personal being but rather an all-permeating Logos-mist, living and governing at the heart of all things, creating a sublime harmony of destiny and virtue which the worldly man need only strive to recognize in order to see all things in the inner-radiating light of their own divine dignity. Leibniz postulated a related model of reality according to which the world is composed of tiny monads (units) endlessly and perfectly reflective of one another, resulting in a universal harmony. It was with reference to Leibniz that Ira Progoff (in Jung, Synchronicity, and Human Destiny) tried to unpack the implication of Carl Jung's theory of Synchronicity, the acausal principle of connection. Jung sought to explain the striking, meaningful coincidences we occasionally experience. Progoff proposed that we take seriously Leibniz's "monadology" system: everything is in fact coordinated, and instances of Synchronicity are momentary flashes that make visible small portions of that coordination, if only to assure us that it is there.

The whole thing, a sublime vista of cosmic order, is the Sacred, for Meaning is Sacred. The monadology is Sacred Space. Mere information, no matter how vital, no matter how surprising, is not sacred and cannot be.

So says Zarathustra.

November 4, 2010

The Eve Is the Edge

I find myself occasionally called on to defend Halloween. When it is attacked, I, too, am attacked, for Halloween is sacred to me. Its armies of ghosts and ghouls, of monsters and mad scientists: these imaginary beings populate my sacred cosmos. In the last week my devotions have consisted of viewing Frankenstein, The Bride of Frankenstein, The Son of Frankenstein, The Ghost of Frankenstein, The Wolf Man, Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, Dracula, The Son of Dracula, The Return of the Vampire, The House of Frankenstein, The House of Dracula, and Abbot and Costello Meet Frankenstein. Today and tomorrow I hope to add to the list Dracula's Daughter, The Mark of the Vampire, and Brides of Dracula. For me Halloween is not merely an annual reminder of something not otherwise on my mind. No, in its shadows and starry voids, its open doors to unknown voids, there I live and move and have my being. It began early in childhood as I experienced both the Mysterium Tremendum et Fascinans, not of the Holy, but of Horror. Once, many years after reading H.P. Lovecraft, I read Rudolf Otto, too, and realized they were the same, and that all that mattered was which one you granted priority to, i.e., which you defined in terms of the other.

I have had to defend Halloween against ignorant and superstitious claims that Halloween is a Satanist holiday (though Satanists are welcome to celebrate it, too). By contrast, the very name denotes its ecclesiastical character: its occasion is the eve before All Saint's Day. The logic and symbolism of Halloween is perfectly depicted in Mussorgsky's piece Night on Bald Mountain (especially as made visible in Disney's Fantasia). The powers of evil know they must hasten from the scene (like Trick-or-Treaters who must get up early for school the next morning) when the dawn of All Saints' Day comes. For then the light of godliness will eradicate every nefarious shadow. And it is this futility that reduces the evil powers to mere shadows who mime and cavort, paper tigers and bristling pussycats hissing at the moon. And it is such monsters that children portray so convincingly as they drift from door to door demanding tribute lest a trick follow. That practice is the dim echo of ancient superstitions that demanded the poor householder make some offering so as to avoid the vengeance of malevolent entities. Halloween defangs the meanies and the monsters because, Christian mythology tells us, Christ has already nullified them, as when Jehovah boasted to Job that he had reeled in Leviathan and tamed him as a plaything for his children (Job 41:1-8) Oh how sad that modern fundamentalists never learned the theological background of holy Halloween! In their fear of it as "Satan's holiday" they have only rebuilt the castle of fear from which Christ once liberated them (Colossians 2:13-17; Galatians 4:8-11).

But lately I find myself defending my sacred day against a different assault, that mounted by priggish, brain-dead schoolmarm types who pooh-pooh Halloween for its excesses. We spend fantastic sums on Halloween accoutrements, costumes, decorations, and candy. It would be more prudent not to. And remember the disapproving disdain of the nanny state we live in, where the only allowable way to observe Halloween is to dress up as Michelle Obama and be glad if you get a goodie bag full of asparagus. The real Halloween is excessive, immoderate, tending toward gluttony and obesity. And that the finger-wagging block-heads cannot allow! But they are missing something. Something essential to human culture. Something they teach in Freshman Anthropology. Victor Turner called it "liminality."

Turner studied rites of passage among African tribes (though the same things go on the world over), and he noticed that the function of these rituals was to conduct the individual through the end of one life stage into another. Each stage has its own integrity as a "life." Each is a defining period of life: childhood, adolescent, marriageability, career, retirement, death and passage to the Next World. In each case it is a matter of crossing over a social boundary, setting aside the privileges of childhood for the quite different privileges and responsibilities of adulthood, for example. The symbols used in celebrating these rites (man-animal masks and such) partake of the character of hybrid mythical beasts or gods, ontological fence-straddlers, because they are the symbols of the social lines we are crossing. Each life period will be stable because of the built-in role-expectations and norms of one's society. If a man refuses to work for a living and wants to sit around and "play" all the time, his neighbors look askance at him because he has not made the complete transition from adolescence. He is still acting like a child. Once a man marries, dating is over. If a husband forgets that, he earns shame and disapproval.

But in the short time during which one is crossing the boundary into a new life-stage, one may (or must) pause on the boundary. In that interstitial vacuum, that twilight zone, certain behaviors, ordinarily forbidden, are now allowed, even customary. Why? Because they, too, serve to punctuate the process of transition. One example observed in New Guinea (I think) is ritual homosexuality between nephews and uncles (don't ask me why!). Or it may be orgies. This element survives today in the form of wild bachelor parties. You're not supposed to mind this behavior, ladies, or to feel ashamed of it, gentlemen. It's like the slogan "What happens in Vegas stays in Vegas," which conceives Las Vegas as liminal to the workaday culture and its mores, an amoral "safety zone" where ordinary rules do not apply. (I'm not advocating this one, mind you. I believe engagement vows of fidelity trump this particular excess. But that is the why of it, anyway, in case you wondered.)

The Eve of All Saints Day marks the cusp between the Dionysian night realm where dreams and nightmares caper through one's head with wild abandon, and the Apollonian day world of law and culture and order and responsibility. The Eve is the edge. The prescribed behavior is liminal, and therefore excessive. When we forget all this, the deep structure of human cultures, culture is "secularized" in the worst possible sense: everything is flattened out. The world is disenchanted, emptied of meaning, and every day xeroxes the one before it. Oh, I know all meaning is fictive play. But that is just what is being bleached out, grayed out, when the schoolmarms warn us not to have too good a time. The Eve is the edge, and I intend to keep walking along it, tightrope though it is.

So says Zarathustra.

October 2, 2010

The Sword of the Stillborn

A Review of Thomas Ligotti's

The Conspiracy Against the Human Race

(Hippocampus Press, 2010. 246 pp.)

Remember how, in Robert W. Chambers's "The Yellow Sign," anyone who attended the decadent play The King in Yellow or even read it was at once plunged into suicidal melancholy? Well, this new book by Thomas Ligotti is The King in Yellow. The real one In his first nonfiction book, a text(ure) woven with all the skill of his superb fiction, Ligotti makes the case for consistent and radical pessimism. Along with a surprising number of previous authors to whose writings he introduces us, the modern master of the macabre argues that humanity is an uncanny alien presence in this world. We do not belong. We, and not some pantheon of gods or ghosts or Great Old Ones, are the intruding blasphemies against the natural order. How so? In what sense? Simply that human consciousness is an aberration of evolution, creating a brain too big for its needs, so it manufactures artificial needs, i.e., for answers to questions which are inappropriate and have no answer. We create delusions and illusions such as the very notion of meaning, not to mention fantasies like a hopeful future, gods, and life after death. Our consciousness, unlike that of the blissfully sleeping world of beasts and stones around us, and trampled by us, makes us aware of the eventuality of death and the acuity of suffering. Pain is the chief occupation of the sentient, Ligotti says, with a negativism worthy of doctrinaire Buddhism (which he discusses). In company with Ernst Becker, Ligotti unmasks virtually all human belief and effort as a pathetic series of failing stratagems to avoid facing the prospect of our own deaths. With Arthur Schopenhauer and Job, he avers that it would be better never to have been born at all.

Whatever joy we may experience ought to make us feel guilty for ignoring the suffering that fills and defines the existences of most people in the world, not to mention the animals we raise to eat. We sin against future generations whom we beget and bear, since we are condemning them in the moment of their conception to a pain life such as our own. Why do we have them? As a (foolish) device to project our doomed selves into a kind of future existence beyond our own deaths. The only decent thing for us to do, as a race, would be to extinguish ourselves. To agree no more to procreate. While Ligotti would have no objection to some act of race-inclusive suicide, he does not advocate it. Nor does he urge his readers to kill themselves, though he blames no one who does. He notes that when readers are moved to jeer at him, "Then why don't you just end it all, huh?" it is a cheap attempt at refutation by reductio ad absurdum. Not that the one who aims that quip would mourn if the pessimist did kill himself, since the former should be relieved at the silencing of a voice attempting to remind him of what he fears because he knows it: life is indeed meaningless, pointless, fruitless, "malignantly useless."

Would you dismiss Ligotti's coolly reasoned jeremiad as the product of a depressive's distorted outlook? Ligotti turns the table: no, it is precisely the depressed observer who sees things accurately. For him the fog of emotion has rolled away. He beholds everything as it is in itself, objectively, namely bereft of all value, interest, and meaning. You know the feeling, I'm sure. When you start feeling good again it is because your emotions are returning, and it is they which project a mirage-like sheen of interest and meaning on the things in one's life. Valorization is mystification. It is not the depressed observer who distorts; rather, it is the optimist whose bubbling emotions cause him to view all things through a rose-colored haze. The fumes of emotion in the brain make everything glow with a splendor that is pure hallucination. It is not the pessimist engaging in reductionism we ought to worry about, but the optimist engaging in mystification.

We are puppets dancing at the ends of strings which are held by no hands, directed by no purpose. That is, we are determined by our upbringing and our genes. There was no rhyme or reason to any of it, but it has made us what we are and dictates what we do. And the knowledge of this, of which again, we remain uneasily and dimly aware, frightens us, impresses upon us the unwelcome knowledge that we are not "humans" as we wish to define them. Not autonomous, not even possessing an underlying self. Robots and toys, zombies, pods replicated by the Body Snatchers, cheap copies without any originals other than the genuine persons we falsely tell ourselves we are. We hate to know this, so we create or embrace foolish theories of free will. We tell ourselves we posses free choice, but, behind all our desires, there is some unknown agency which has delimited our choices. There are some we will never make even though a friend or neighbor readily makes them. We, too, one would think, are "free" to make them. But some prior hand controls even those strings. We are on the receiving end, puppets made to dance by an idiotic demiurge: Azathoth. How terrible, we think, to have to accept that another has scripted this play and that we are but characters within it. But that is what we are. And no sane mind wrote the novel—just the proverbial room full of monkeys madly clacking on typewriters.

Though Ligotti does an admirable job citing Eastern as well as Western precursors to his pessimism, I found, as I read, that I could not help thinking of some parallels in other Asian sources he did not see fit to mention. Some helped me appreciate his position more; others made me dissent from it. Let me take a little "journey to the East" with you.

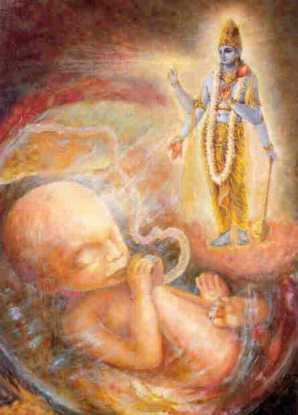

I think of a cosmogony shared by Samkaya Hindus, Patanjala yogis, and Jainists, all of whom purportedly believe that universal human suffering is the result of a contamination of the primal ocean of undifferentiated matter (prakriti) by a rainfall of germs of purushas (or jivas), life monads. The entrance of these magic bullets caused the primal stew to start percolating, issuing in the formation of countless matter-forms and life-forms, each dominated by greater or lesser amounts of the three gunas, or modes: awareness, energy, and inertia. (The envisioned scheme is much like that of the pre-Socratic Empedocles as well as the Gnostics.) Your ego or psyche, the conditioned, ever-changing psychological "self" you see reflected in the mirror and on Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Tests, is material in nature (even we admit brain action is chemical in nature, right?), and if the luminous mode of buddhi (cognate, I assume, with Buddha, enlightened one) was not awakened by the unwelcome and unnatural intrusion of the purushas, you would not know pain. The purusha becomes the isolated, unconditioned, and eternal self, the atman, which is carried along passively from one incarnation to the next, held by the conditioned self and the karma that propels it. The purusha, being unconditioned, unaffected, does not suffer (like Aristotle's Unmoved Mover). But its linkage to the ego self makes it possible and inevitable for the material ego self to experience suffering, which it does in incarnation after incarnation. Yoga of various kinds promises techniques to enable the suffering soul to find liberation from reincarnation and suffering. Through meditation one learns to pry the atman / purusha loose, whereupon it flies back up to the summit of the Universe whence it originally came. Bingo! For the rest of the duration of this last incarnation, the yogi abides in a placid state of "mere witness" (the ego-death state Ligotti discusses) and then vanishes when the final incarnation is over. The atman is like the battery in the flashlight: it does not itself illuminate/experience suffering, but it makes it possible for the lens of the flashlight to illuminate it.