Robert M. Price's Blog, page 5

April 1, 2012

Freethought Is Free but not Cheap

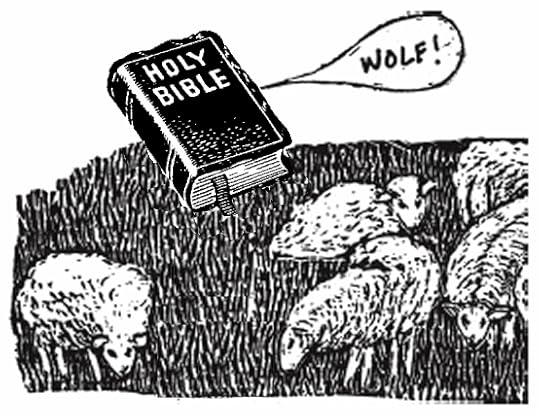

A church signboard reads, "Freethinkers are Satan's slaves." Well, isn't that special. Reminds me of the movie One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest. Jack Nicholson plays a sane man stuck in an insane asylum. He is sticking up for the rights of his fellow inmates, waging a real battle against institutional oppression. He pays a heavy price. And then you find out all these sad sacks are in the place by their own choice. No one's keeping them there, no one but themselves. Jack was fighting the wrong enemy. "We have met the enemy and he is us" as a talking muskrat once said. I believe this well describes the church with the signboard. They are afraid of freedom. They want to "escape from freedom" (Eric Fromm). They have mortgaged their souls to the Grand Inquisitor. They want him to do their thinking for them. It is they who are the slaves. They have the Stockholm Syndrome, rejoicing in their oppression—which they entered into voluntarily, as when the last of the Hasmonean rulers invited the Romans in to settle their disputes, surrendering their hard-won freedom in the process. They have subscribed to the Orwellian maxim: "Freedom Is Slavery." They're like the old man hanging by wrist manacles on the mossy prison wall in Monty Python's The Life of Brian (of Nazareth): "Crucifixion? Best thing the Romans ever did for us!"

Have I cussed them out sufficiently? Good. Now let me get on to a larger issue implied in the idiotic message of the signboard. Just what is free thought? What is a free thinker? We usually associate the word with religion rejecters. They announce that they have cast off the shackles of dogma. Church told them what to believe. Theologians said that was only natural, since the truth about supramundane things is not available to human sight and reasoning. If we are to know them at all, they must be revealed to the human race by God, and they have been. The only possible response is faith. But how can you know a particular set of scriptures or doctrines has really been revealed by God? Well, that's another thing you're just going to have to believe, since in the nature of the case there's no way to verify it. Freethinkers have opted out. They suspect a con job in progress. But let's assume good motives all around; there is still the problem of willing yourself to believe something. Sure, plenty of people do it, but a real thinker knows that would commit him to Orwellian Doublethink. Deep down you know you don't know that doctrine A or religion X is true, yet you tell yourself that you do. The Freethinker has had enough of this.

Freethought is thus the exact same thing as "heresy," which comes from the Greek word for "choice." It is what Orwell called Thoughtcrime. Listen, young lady, the Church will tell you what to think. What? You dare decide for yourself what to believe?" That's right, choosing for yourself what to think is heresy. It is Freethought.

Freethinkers are often characterized (accurately) as holding eccentric opinions. This may be because they are weirdoes like Dale Gribble. I have known more than a few. Conspiracy theorists of various stripes. Having rejected majority beliefs, it's open season. The sky's the limit! Anything and everything rushes in to fill the vacuum. The problem with such poor souls is that they do not yet know how to evaluate evidence and arguments in a genuinely critical manner. They didn't when they accepted orthodox dogma lock, stock, and barrel. And they didn't necessarily know any better when they exited their religion. As a result, they buy into the next thing with the same uncritical enthusiasm. They may not have thought their way out of religion so much as felt their way out.

But there may be more than one reason someone is found to embrace opinions outside the mainstream. As an advocate of the theory that there was no historical Jesus, I get "my fair share of abuse." Take a look at what Bart D. Ehrman says about me in his new book Did Jesus Exist? (Of course it's nothing compared to his slanderous attack on Earl Doherty! Professor Ehrman must be hoping Doherty, author of Jesus: Neither God nor Man) is not in a suing mood.) I am there painted as a blatant thought-criminal. The vast majority of New Testament scholars do not take my view. That could be for a couple of reasons. Maybe my foolishness if evident to anyone with a brain. Or it just might have something to do with the fact that the large majority of biblical scholars are still Christian believers, even if of only a liberal stripe. I don't want to commit the genetic fallacy or the ad hominem fallacy here. I can't read their minds. I am only saying that their faith and their need to appeal to a historical Jesus to support their views might have something to do with it. You really have to examine the issues for yourself.

Same thing with the political dogma of Global Warming or Climate Change (a rebranding much like today's Theistic Evolutionists hiding behind fancy new labels like "Evolutionary Creation" and "BioLogos"). I am not going to take for granted that the mass of supposed experts are right, when they have been wrong before (Nuclear Winter, Global Cooling, etc.). I go no farther than being suspicious, though, since, if I wanted to have a definite position on the question, I would have to take my own advice and do the research for myself. Otherwise I could not just take the word of either side. And I do not have sufficient time or interest to pursue the matter. If you do, good luck. But I am not going to treat any of these matters like a game of Family Feud: "Survey says…"

And this brings me to the main point I wanted to make. If you are genuinely free in your thought, not a dogmatist, you have to (theoretically) keep all questions open. You have to allow freedom to ask even the unaskable questions. Freethought is a matter of what boxes you are willing or unwilling to think outside of. I must admit that, knowing what I know of the claims and credentials of religion, it is hard for me to see how someone could take the opposite views. Having been one of them, I must suspect that apologists for Bible accuracy and inspiration are slanting the facts and care only to rationalize beliefs they hold on other, nonrational grounds. But it is I who am less than a Freethinker if I assume automatically that no one can arrive at very different views from mine by way of free thought and fair considerations. It remains true that honest minds differ. Who knows what factors limit our horizons of inquiry? Catechism? Social class? Vested interests? Ultimately you can't be totally objective, though we do have to try our best to spot our biases and free our thinking from them just as we have freed it from religious bullying and threats of hell.

I was privileged to know Clark H. Pinnock, an Evangelical theologian and a New Testament Ph.D. (he studied under F.F. Bruce). Pinnock was intellectually fearless. He said what he thought no matter whom he alienated. He was not afraid to change his mind publicly. He was one of the original rabble rousers who engineered the fundamentalist coup in the Southern Baptist Convention, yet he was later almost expelled by the Evangelical Theology Society. This man, I am sure, freely thought his way to his orthodox Christian beliefs and never saw sufficient reason to change them. I did not agree with his views, but it does not occur to me to question his intellectual honesty. I am familiar with his writings, and it is readily apparent that their author was struggling honestly with every issue he faced. If I don't allow for that, it seems to me I am no Freethinker.

I have gradually come to see questions on which, in retrospect, my thinking was not as free as I once thought and hoped. I do not have the right to make my own opinions, no matter how inductively derived, into dogmas from which I refuse henceforth to budge. That would be too easy, too convenient. It would be cheapthought, not freethought. If I do not keep an open mind, I am no Freethinker.

So says Zarathustra.

March 3, 2012

Are We at War with Islam?

"It's a simple question, Norm. Are we?"

Simple? Not necessarily. It is surprising, given what seems to spark murderous Muslim rage (cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad, the burning of Korans, etc.), how many people deny that we are fighting Islam, and some even label the very designation "Islamofacsism" as a sign of Islamophobia! Whence the confusion? It arises from the way we define our terms. The trouble is trying to determine what Islam (or any religion) "really" is. What is its essence? Who are the true Muslims, and who are promoting a false version, a perversion, of the faith? These questions are useless and impossible to answer, for there is no "essence" of any religion. What is it that you would name as the essence of your own religion? Your favorite part? Who has the copyright on the "true" form of a religion and with it the right to declare other forms of it to be heresies? Well, everybody seems to think they do, but they are self-appointed. You know they say "heresy" exists only in the second and third persons, orthodoxy in the first. I am by definition an orthodox upholder of the truth, while you and they are a bunch of heretics.

Wilfred Cantwell Smith addressed this issue in his book The Meaning and End of Religion. What he winds up saying is that you can't draw a circle around a single center and declare that center to be the essence of the religion around which everything revolves and from which it all stems. Reality is much sloppier than that, alas. Oh, it's not unfortunate for the people who belong to the religions; it just makes things tough for scholars seeking to understand religion.

Smith recommended that we picture a religion as an ellipse wrapping around twin foci. The one focus is the body of doctrines, or one might say, bodies of doctrines, for even this focus is not static. You would have to include the whole range of beliefs and how they have evolved, and this without value judgments as to which one is a true and legitimate mutation of the original, if we can even tell what the original was at this late date.

The other focus would be another pretty loose one, namely the collection of members of the faith community both diachronically (through time) and synchronically (a cross section of the membership at any given moment or era). Again, this way of looking at a religion is not very handy for defining the essence of a religion, but that's too bad. That is a bad idea. You'd be trying to measure something that doesn't exist. Like asking what color a symphony is. Huh? You'd better go back to the drawing board, and that's what Wilfred Cantwell Smith did.

One more stab at it. The great early twentieth-century theological historian Adolf von Harnack wrote a very popular book called What Is Christianity? Which, obviously, raised the essentialist question and answered it with his reconstruction of the historical Jesus (who looked suspiciously like a liberal Protestant!). Harnack thought Jesus' simple message had been corrupted by the church, and that we should get back to the simplicity of Jesus' message of the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man. His Galilean gospel, Harnack believed, was the kernel of Christianity, while all the subsequent institutional consolidation and philosophical-mythical interpretation was the husk. We ought to cast off that old husk. But Roman Catholic Modernist scholar Alfred Firmin Loisy rejected Harnack's approach. He was fully as critical, ready to peel back the layers of the evolution of Christianity, but he preferred a different metaphor: not kernel versus husk, but acorn and oak. Jesus' admittedly simpler message was the acorn, the seed, of what would eventually become a giant oak with mighty branches spreading in all directions (see the parable of the mustard seed in Mark 4:31-32). I think Loisy's point anticipates Wilfred Cantwell Smith's and even helps make it more understandable.

So are we at war with Islam? Well, any answer is wildly off course which refuses to recognize the plain fact that a radical segment of Islamists understand their own motivation to conquer the West (as Quixotic as that may seem) and to replace its way of life with the iron law of a worldwide Islamic caliphate. This is no mere interpretation by Westerners who may be misreading them; no, very clear statements by Muslims to this effect are on record, and plenty of them. They believe themselves to be attacking us in the name and for the sake of Islam. Who are we to say they are wrong about their own motives? Just because that scheme seems as bizarre to us as Charlie Manson's did doesn't mean it doesn't make sense to them. And it does.

Why are some Westerners so arrogant as to assume these chaps must really see things as we do? "It must all be a question of economics and anti-colonialism, right?" Don't you get it? Just as we cannot precisely define a religion, neither can we isolate religion from all the interlocking social and cultural factors that accompany it. Just because there is an economic aspect doesn't mean their motives are not religious. And just who thinks this? Those who cannot take religion seriously themselves (and believe me, I know the feeling!) just cannot get inside the heads of those strange (to them) birds who can and do. For all their multicultural pretence, they cannot take the otherness of the other very seriously. Believe them, why don't you? They are Muslims heeding the Koranic call to fight and kill infidels.

I find this especially ironic, since many of the same people who believe themselves just too enlightened to suppose we could be facing a religious war, that religion couldn't be the real issue, since religion is so silly, no one could possibly take it seriously—well, they are happy other times to condemn religion per se as a poison that is inherently bad. The evil religion does is not just a subset of "the evil that men do" because of their fanaticism, greed, and intolerance. It is not these vices that are at fault, expressed in the trappings of the religion that these evil people happen to hold. No, it is the religion that is the possessing demon. If reason could cast out religion, then all would be well. When you point out that the same horrors have been perpetrated in the name of atheistic philosophies and regimes, these religion haters will pivot and say that Mao and Stalin was acting in a religious way. Religion equals evil. But in the case of Islam, suddenly it is the other way around. It couldn't be the religion that drives them to the frenzy of murdering guys because they dared get a Western-style haircut! No, "it's the economy, stupid!"

What I want to know is: of all people, why are you trying so hard to give these nuts the benefit of the doubt? A Catholic lady demonstrating in front of an abortion clinic? Now that's terrorism! But the Muslim Brotherhood? A bunch of swell guys! I suspect it is a case of cowardly appeasement, what during the Cold War they used to call Finlandization. It is because they know the Catholics are not really dangerous that they can attack them so mercilessly. Bt those Islamists? Those bastards will saw your head off on camera! Uh, let's not step on any of their toes!

But what about all those peace-loving Muslims? Aren't they real Muslims, too? Yes, they are. I realize that militant Islamists regard these people as compromisers who are dropping their obligations in order to coexist with those whom they should hate and overcome. They are despised "liberals" and "modernists." It's the sort of abuse theologically liberal Christians have learned to endure from their fundamentalist cousins for generations (though without violence). But the more moderate Muslims view themselves just as theological liberals in Judaism and Christianity do. They practice an ancient faith in a modern world where many things have changed, and they have to come to some accord with reality. If militants view moderates as backsliding compromisers, moderates view militants as throwbacks who should get with the program as their religion tries to keep up with a changingworld.

My whole point here is that anyone who has his or her own version of Islam is a "true Muslim," no matter what other Muslims may think, because there is no demonstrable "true essence" version of Islam. It's all in the eye of the beholder. We are not fighting against all Muslims, though keep in mind that Sufi scholar Sayyed Hussein Nasr estimates that a mere ten percent of Muslims worldwide support Jihadism. That's a "mere" hundred million people! But it remains true that we are not fighting against all Muslims, because not all Muslims feel their faith requires them to hate and to kill us. But just because we're not fighting against all Muslims doesn't mean we aren't fighting against Muslims. It is not all(ah) or nothing.

I guess this means that we can face the nasty prospect of a war, not on behalf of our religion (especially since "we" don't have one), but against a religion, radical Islamism. We find it terribly hard to believe this, because we prefer to think we live in a more enlightened age. And we do. The trouble is, they don't.

So says Zarathustra.

February 12, 2012

Does the Bible Vilify Israel?

No, I'm not asking the old (and, unfortunately, good) question of whether the New Testament gives Jews a bum rap. I want to make the argument that the process of unfairly condemning Jews, Israelites, already begins in the Old Testament. We still read in Jewish as well as Christian writers, even ecumenically sensitive ones, about "the Israelites' tragic tendency to welsh on their covenantal duties to God." But what evidence is there for this sorry record? It is useful as a foil, a bad example to wield to shame Jews and Christians and guilt them into greater piety, I know, but I believe it is slander. Slander not of modern Jews, but of ancient ones.

My basic point is that Jewish "orthodoxy" keeps getting revised throughout the Bible and that the people of the past get blamed for not keeping up with the present. They are casualties of theological revisionism and ritual evolution. Their imagined crimes are committed against laws and doctrines they could never have known about. Why and how? Because, as Julius Wellhausen showed so long ago, as the priests and scribes "reformed" Israel's religion, they sought to avoid the charge of novelty and modernism by rewriting history: pretending, a la the Ministry of Truth in George Orwell's 1984, that these new stipulations and doctrines had been in force from the very beginning. The goal was to secure (i.e., fabricate) an ancient and authoritative pedigree. It was well known, however, that these were not in fact the old ways. Everybody knew their ancestors had not thus practiced the faith of Israel. So their ancestors (and their contemporary descendants in the time of the reforms) had to be retrospectively portrayed as apostates and backsliders who already knew good and well, for instance, that there was only one single deity, and that he alone should be worshipped. Since all knew Israelites had always worshipped many gods, they must have been lapsing from an already-existing monotheism, "whoring after the heathen" ways of their Canaanite neighbors! How wicked of them to have offered sacrifices on the hilltop shrines ("high places") and sacred groves and graves of sainted ancestors! But in their day nothing was considered wrong with that! The Bible itself mentions approvingly various sacred groves (Genesis 12:6-7; 13:18; 18:1) and saints' graves (Genesis 35:8, 19-22). But once King Josiah outlawed them, not only his subjects who might continue to patronize them were considered heretical outlaws, but even the people who had worshipped there when it was thought legitimate. These long-dead people were being tried at the court of the future, condemned for failing to observe its laws—which didn't exist yet!

Ever wondered how the Sun King Solomon, lauded in the Bible for esteeming divine wisdom over worldly riches, nevertheless turned into a bum? How he went down in Bible history as an apostate? How could that have happened, especially to a guy who, possessing the very wisdom of God, should have known better? Well, you ask, what did he do? What was his crime? Nothing at all in his own eyes or those of anyone else alive at the time. True, he made marriage alliances with scores of petty kings, marrying their daughters and building shrines in Jerusalem for their familiar gods so they'd feel at home away from home. (For the same reason, when Hellenized Diaspora Jews moved to the Holy Land in the first century CE, one might have thought they would be glad to worship only at the Jerusalem temple, leaving their local synagogues behind. Now they had the real thing. But they had been away from "home" too long! They missed their synagogues, so new ones were erected for them in Hellenized Galilean cities like Caesarea Philippi, the only Galilean synagogues we know of in the ostensible time of Jesus.) But, you guessed it, once history went on and official Israelite religion became monotheistic, Solomon started looking, albeit anachronistically, like some kind of an idolater.

All that stuff about Israel getting corrupted by the Canaanites? More of the same. Archaeology has made clear that the ancient Israelites simply were Canaanites (something already clear enough from all those Genesis tales explaining how the ancestors of Israel, the Ammonites, Moabites, Edomites, etc., were all close blood relatives). There was never any sojourn in Egypt nor exodus out of it; that's certain. There are no remains of such a mass movement of people and cattle, no matter which proposed exodus route you favor. (Did God send angels down with vacuum cleaners? Did Satan plant fake dinosaur bones to make us doubt Genesis? One's about as likely as the other.) There was never any Israelite conquest of Canaan, no genocidal extermination of Canaanite nations. The Israelites practiced pretty much the same Baal worship as their Canaanite brethren, not because they copied if from them, but because that was their own native religion. It was only later Jewish writers, having moved toward monotheism, the centralization of sacrifice in Jerusalem, and the outlawing of spirit mediums and sacred hookers, who looked back on the old religion with pious disgust. They couldn't deny that their own forbears had shared that worship, but since they were retrojecting much later theology back into the mythical time of Moses, they simply inferred (pretended) that their ancestors must have known better. And so they were backsliding sinners!

The scribes and priests kept retrojecting new versions of Israelite religion into the mythic past in order to provide a venerable pedigree. And this made the ancients look like transgressors of a covenant that hadn't actually existed in their day. It's just the same when Christians look back and wonder what the hell was wrong with "those Jews" who should have defined the messiah as Christians do now and should therefore have recognized Jesus as the messiah. It's a theological optical illusion, dangerous hindsight.

Ever read the Book of Judges? It is a long list of object lessons on how, as long as Israel keeps their covenant obligations of Torah observance, all will go swimmingly well for them. But as soon as they start cheating and backsliding, God will yank the rug out from under them, giving them into the hands of foreign oppressors. When they repent, God will send a deliverer to free them from their conquerors. But, as Old Testament scholars know well, this structure is entirely artificial. The Deuteronomic redactor has shoe-horned what were originally stories of how this and that Israelite tribe (or group of tribes) managed to win their first-time independence from their local overlords. They are stories of piety and valor, not of apostasy and repentance. Just read 'em. Another case of vilifying one's Hebrew ancestors in order to promote a later theology. Scapegoating the past.

How about the "murmuring," the incessant grumbling of the Israelites against Moses? No matter how many miracles they witnessed, they always believed they were doomed, and as a result they were full of complaints against Moses and his divine patron. But these stories are fictions, and the murmuring is a classic case of the skepticism motif intrinsic to miracle stories. It is merely a literary device to raise the bar for the miracle-worker to jump, to make his feat look all the more spectacular. Again, no sinful Israelites here.

There is another group of texts in the Bible which vilify ancient Jews and Israelites in order to justify the ways of God (Romans 3:4). The biblical narrators had to get God off the hook: hadn't he pledged himself to protect them? "He who guards Israel neither slumbers nor sleeps" (Psalm 121:4). But then how come Israel in the north got devoured by the Assyrian Empire? Why did Judah in the south get chewed up by the Babylonian Empire? Uh, they must have deserved it! Yeah, that's the ticket. It's just like Job's comforters, completely deductive: "We know God afflicts the wicked, not the righteous, so you must deserve what you're getting!" (Cf. Job 4:7-9). God couldn't have failed, so we must have. That may be a bitter pill to swallow, but would you rather believe your God is asleep at the switch? You can also see here how Sodom and Gomorrah got such a bad reputation. They were obliterated by volcanic activity. So people said, "Wow! They must have done something to royally piss off the Almighty! What do you suppose it was?" And then speculation begat good object lessons, "Men, don't let this happen to you!"

But don't we have solid evidence of Israelite wickedness in the books of the Prophets? Doesn't Isaiah (e.g., Isaiah 1:11-18) skewer the religious crowd for hypocrisy? He tells them God isn't interested in their fancy litanies and sacrifices as long as they are cheating customers and defrauding employees the rest of the week! Get out of here and clean up your act, and then maybe we'll talk ("Come, let us reason together."). But keep something in mind; historically people had made no connection between moral wrongs done to fellow human beings and "sins" committed uniquely against God. Sins were ritual infractions, as when hapless Israelites get executed for gathering kindling on the Sabbath (Numbers 15:32-36), getting the incense recipe wrong (Leviticus 10:1-3), steadying the Ark of the Covent so it didn't fall in the ditch, but without proper ritual preparation (2 Samuel 6:6-7). Even dietary infractions like eating pork weren't considered moral wrongs—who did they hurt? In all these things, you were affronting God who had laid down the law on matters of ritual and ceremonial uncleanness. "Sins" were purely religious in nature. The Prophets were in the vanguard of what Karl Jaspers called "the Axial Age," when religion worldwide became interiorized, moralized, rationalized. Originally the "holiness of God" had denoted his mind-blowing Otherness, but later it came to denote his moral righteousness. In the same way, the category of "sin" was moralized to include wicked deeds done to fellow mortals. These were just as much an offense to God as eating a goat boiled in goat's milk.

So, as I understand it, Isaiah was holding his public responsible for "violating" standards which they had never heard of. Like Moses coming down from Sinai with the news that you mustn't worship idols and getting furious at finding the people worshipping the Golden Calf. How did they know they weren't supposed to be worshipping it? One can only imagine the surprise at Moses' or Isaiah's rebukes. What were they doing wrong? Of course, the moralizing transformation of "sin" was a good and important development, but it isn't exactly fair to blame an older generation for not already being on Isaiah's wave length. It was always degrading and wrong to be a racist, but it looks a bit different before and after Dr. King. You know: "Where there is no law, sin is not reckoned" (Romans 4:16).

Look, admittedly the people I am talking about are long dead. But it bothers me to keep seeing the biblical Israelites reduced to a homiletical piñata when there is no reason to regard them as any more "sinful" or "faithless" than anybody else. It's all a bum rap. And I suspect it's a bum rap that makes it easier for those inclined to vilify modern Israel and Jews today.

So says Zarathustra.

December 31, 2011

Tempest in a Tebow

This month I am offering two essays, one dealing with religion in popular culture, the other with gospel criticism. I suspect Zarathustra's diverse readership contains individuals who might have little interest in one or the other of these mini-essays, so I figured the best option was to run both.

Tempest in a Tebow

I will admit right up front that the Tim Tebow phenomenon is insignificant, but because it appears to be impossible to avoid if one watches the news (not even just the Sports segment!), I might get away with a brief comment on it here. As I understand it, this Tebow fellow drops to one knee and prays after any and every successful maneuver, right there on the gridiron, in full view of the stands. He wants to avoid claiming the glory for himself and giving the credit where it is due, to the Almighty, who, being omniscient, can scarcely be oblivious of what is happening in the game, or, for that matter, in every brothel, crack house, and Congress. Many applaud Tebow's "courageous" stand for his faith; others complain that he is imposing his religious expression on the stadium and TV audiences who do not necessarily share it. What are they supposed to do, turn off the game? They shouldn't have to. But what do you expect? This sort of piety masks its arrogance under the veil of humility: "You don't like it? Tough: it's my Christian duty to be obnoxious—take it up with God!" Yeah? Well, you can take your faith and…

I am not aware that anyone is urging that T-bone's freedom of expression ought to be curtailed by the authorities. I certainly am not. I just think of Janet Jackson and that guy that looks like an unshaven Popeye (what's his name again?) and I call his religious gesture a "piety malfunction." Actually, my critique is a purely theological one.

What I am about to say is basically superfluous given the expert comment rendered on a recent Saturday Night Live skit (available on YouTube) in which, in answer to Tebow's prayer in the locker room, Jesus himself shows up to ask the enthusiastic football player to tone it down a little. The Son of God congratulates the team on their latest victory but points out that he is doing most of the work! When Tebow invokes Jesus like a genie, Jesus answers, but wouldn't it be a little better if the team won the games on their own strength? Read the Bible, sure, but how about studying the playbook, too? This is an apt theological critique, very much akin to an SNL skit from years ago in which Sally Field plays a pious housewife asking Jesus not to let the roast burn, etc., every five minutes. Phil Hartman appears as Jesus, asking her to save the prayers for the really important matters. It is scathing because it is not a parody (a distortion for laughs) but rather a true satire (accentuating the actual absurdity inherent in a thing). The same goes for the Tebow skit. Bravo!

But some viewers didn't like it, a fact which will not exactly surprise you. Pat Robertson griped that, had such a skit been broadcast in Islamic countries, portraying the Prophet Muhammad instead of Jesus, the bombs would have been flying. I'm not quite sure what Robertson was implying with this comment: did he not-so-secretly want to issue a fatwa on the SNL cast?

What does surprise is that equal outrage came from a man one might deem Robertson's opposite number: arch-liberal Bob Beckel, one of the hosts of the FOX News talk show The Five and one-time campaign manager for Walter Mondale. Beckel said it was "despicable to portray our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ" in such a manner. Bob Beckel? Bob Beckel, Obama ass-kisser? Self-proclaimed Socialist? Aren't such people supposed to be secularists, even if they occasionally try to feign religiosity in order to gull believers (Howard Dean: "My favorite New Testament book is Job")? Well you see, until recently, Bob was languishing in the grip of alcohol and drug addiction. He snapped out of it with the help of one-time Moral Majority bigwig and conservative columnist Cal Thomas, who "led him to Christ." Sounds good to me; I think it is much more important for someone to get off drugs and booze than for one to come around to my views about religion. Whatever it takes! Nation of Islam? Scientology? Whatever gets you out of a living hell.

But perhaps ultra-liberal Beckel simultaneously being a religious fundamentalist is not so incongruous after all. He is refreshingly hilarious and not given to plaster sainthood. But one sense in which he is perfectly suited for his new creed is that he, as a political apparatchik, is a veteran spin doctor, ready to put a good face on a bad reality, making the outrageous seem plausible with a straight face. He could become another William Lane Craig if he wanted. Bad evidence is just waiting for Bob to redeem it. What he could do with intractable Bible contradictions! With the authenticity of the spurious Josephus passage! Of course, he could only convince those who already want to see things his way, but that's the whole point. And he's already a master at it.

I have to admit that, from a free thought, atheist point of view, I have one reaction to Tebow's forthright faith and its conspicuous confession. Have you ever heard a friend boasting about something that hardly deserves it? A bad record album or an utterly undistinguished acquaintance? You suspect it is a variety of the inferiority complex and signals an inner shame or embarrassment they deep-down know they ought to feel. They are bluffing their way through it, hoping to bamboozle you into thinking there must be something to it after all. Cognitive dissonance reduction? Just saving face? They'd rather seem deluded than admit to themselves they're magnifying nothing. I have to wonder if that is what is happening when Tebow and other in-your-face religious athletes publicly brag about faith. I cringe; I wince. I think it is sad they are just so proud of being so ignorant. I think of Philippians 3:19, "They glory in their shame." Sort of a religious equivalent to Larry the Cable Guy.

But from a Christian standpoint, the reaction has got to be one of amazement. How can this Tebow be giving glory to Jesus when he is in the same moment disobeying him? For Jesus said (we are told), "Be careful not to practice your religion in front of others so as to be seen doing it… And when you pray, do not be like the hypocrites, because they just love to pray standing in the synagogues and the corners of the public streets so they may be on display… But when you pray, enter into your private room and, having shut your door, pray to your Father, he who is invisible" (Matthew 6 1, 5, 6). Of course, one might counter that Tebow is not publicly praying with this motivation; rather, he feels it is important to make a testimony for Christ amid an irreligious culture. But is it? Is the stadium filled with members of the American Humanist Association and the Freedom from Religion Foundation? I doubt it. And besides, don't you think anyone who prays in public and makes a big deal of it rationalizes it this way? How can pride not enter in? "What a good boy am I!" The whole logic of the passage is to "build a hedge around the Torah," taking preventative measures lest a seemingly harmless act lead one into sin, in this case, self-righteous boasting.

And then there is the trivializing absurdity of bringing God down to the level of football while one stupidly thinks one is raising football up to God. There's a time and place for everything, as when Dietrich Bonhoeffer quipped that one really ought not to be longing for heaven while in the arms of one's spouse. Or remember when the Reverend Norman Vincent Peale, when a reporter asked whether Peale thought Jesus would have looked askance at his attendance at the Super Bowl, replied, "If Jesus were alive, he'd be here today."

So says Zarathustra.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Problem of the Parables

You may know that I have argued that exactly none of the gospel sayings "of Jesus" stem from a historical Jesus of Nazareth, and not for the simple reason that there was no historical Jesus. No, my reasoning on that score is inductive, not deductive. My initial working hypothesis was to assume there had been such a Jesus, an itinerate holy man active during the tenure of Pontius Pilate. Following in the seven-league footsteps of Rudolf Bultmann and Norman Perrin, I scrutinized the gospel sayings, alert for signs of anachronism, borrowing from other contemporary sources, tendential constructions by the early church, prophecies from the Risen One through the lips of charismatics and apostles, and anything else that might imply inauthenticity, that the material originated post-Jesus. But at length, I found so much of it to be fatally problematical on these criteria, that I wound up regarding the estimates of the oh-so-skeptical Jesus Seminar (18% of the sayings probably authentic to Jesus) as hopeless optimistic.

Now I find myself noticing gospel texts that come near to admitting the secondary character of a lot of the material. It starts with the parables, many of which were first collected as they appear in Mark 4. These include the parables of the Sower/Soils, the Lamp, the Seed Growing Secretly, and the Mustard Seed. Matthew revises and expands the section, as we read it in Matthew 13. The new Matthean parables look to me to come from Matthew's own hand rather than from some pre-existing "M source," and the same is true of the uniquely Lukan parables (Lost Coin, Lost Sheep, Prodigal Son, Good Samaritan, Dishonest Steward, Pharisee and Publican, Unjust Judge, etc), which all share similar narrative features; in other words, no "L source."

But back to Mark. Mark 4:33-34 says, "And in many such parables he spoke the word to them, as much as they were able to grasp. And unless he had a parable he did not speak to them, but in private to his own disciples he explained everything." It suddenly occurs to me that this statement implies that whoever said it did not know of other, non-parabolic teaching of Jesus, which nonetheless abound elsewhere in this gospel and all others: aphorisms, apocalyptic sayings, straightforward admonitions, etc. The impact of this incongruous statement is comparable to the astonishing statement in Mark 8:11-12: "The Pharisees came and began to argue with him, seeking from him a sign from heaven, to test him. And he sighed deeply in his spirit and said, 'Why does this generation seek a sign? Truly I say to you, no sign shall be given to this generation.'" Mustn't that verse stem from a time when people believed the incarnation was so complete that Jesus had left all divine powers behind in heaven (cf. Philippians 2:6-11)? First Corinthians 1:22 likewise says that "Jews seek signs [precisely as in Mark 8:12]… but we preach Christ crucified," which certainly implies Paul knew of no miracles ascribed to Jesus, which is why his letters never mention a single one.

My point is that Mark 4:33-34 makes the same sort of programmatic statement: there were no non-parabolic teachings circulating in the writer's day. Sure, we find non-parabolic material elsewhere in Mark, but the same is true about the miracles: Mark has plenty, even though he has preserved a saying that rules them out, justifying the absence of miracle stories in the time that saying originated. And this all in turn implies that the non-parabolic teaching was a subsequent addition, aimed at filling the perceived gap—just like the miracle stories.

But it occurred to me also that one must look again at the parables and ask if it is really plausible that people came in droves to listen to this stuff. The narrator himself tells us what the history of parable interpretation makes abundantly clear: there is no clear point to any of these parables. No one could have taken away enough meaning to keep him coming back for more. They are not like Aesop's Fables. Commentaries on Mark and tomes on the parables (and there are very many of both) offer endless possible interpretations of the parables, all of which make the parables' meaning dependent upon some larger theological system extrapolated from the gospel as a whole, or from a life of Jesus construct as a whole. Such a framework for interpretation is a chain of weak links.

And the recent readings of the parables by Dan O. Via, Bernard Brandon Scott, and Charles W. Hedrick strike me as so over-subtle and counter-intuitive that only fellow specialists playing the same exegetical game could possibly find their interpretations even plausible much less convincing. In short, I can imagine Jesus getting and keeping an audience with this lame material as easily as I can imagine anyone memorizing the whole of the Sermon on the Mount from hearing it once. Just take your head out of the text, and out of the scholarly game, and you'll agree with me.

So Jesus taught only in parables, which disallows everything else. But then he could not have taught with these parables either. It all reinforces the conclusion that there was originally no such figure as "Jesus the teacher" or Rabbi Jesus. Maybe this is why the Pauline epistles never appeal to any sayings ascribed to Jesus either. There weren't any yet. That would come later, and not from Jesus.

And remember Mark 13:11? "And when they lead you before the authorities, do not bother formulating beforehand what you will say, but whatever comes to you on the spot, say it. For you are not the speakers, but the Holy Spirit." I draw the same inference from it that Luke did in his rewrite: "I will give you a mouth and wisdom that none of your adversaries will be able to withstand or refute" (Luke 21:15; cf John 16:12-15: "I have many more things to tell you, but they would be too much for you to deal with now. But when that one comes, the Spirit of Truth, he will guide you into all the rest of the truth. For he will not speak his own opinions, but he will relay what he hears, and he will announce future events to you. He will glorify me, because he will receive revelation from my treasury and announce it to you.."). In the heat of argument, don't worry: Jesus will supply the words—which then must have been simply ascribed to him, with no concern whether they were spoken by an earthly, historical Jesus, or by a post-Jesus Christian prophet/confessor. Wouldn't this be the ideal candidate for the origin of all those controversy stories in which "Jesus" reduces his opponents to silence with his clever retorts?

Nor let us forget Matthew 10:27 (a saying from the Q source, shared with Luke 12:23, where, however, it is made to have a very different point), "What I tell you in the dark, utter in the light, and what you hear whispered, proclaim upon the housetops." Remember how the gospels sometimes rationalize the late appearance (thus secondary character) of certain stories like the Transfiguration and the Empty Tomb by claiming that the Jesus-era hearers either were warned to delay reporting it (Mark 9:9-10) or just failed to report it (Mark 18:8). That's why you're hearing about it only now—yeah, that's the ticket! Doesn't it make sense that Matthew 10:27 should denote the same thing? That those who later credited their own preachments to Jesus in order to give them added clout "explained" why no one had heard them before by claiming they had first been told in secret? That is a classic Gnostic ploy, to maintain that Jesus had taught their newfangled teachings to the apostles all right, but in secret, which is why riff-raff like you never heard of them till now! Again, this, I think, is a signal within the gospels that their material is spurious.

Another comes in Luke's version of a Q saying. Where Matthew had "Whoever welcomes you welcomes me" (Matthew 10:40), Luke (10:16) has added "Whoever hears you hears me." This might easily mean the same thing, but one must wonder whether Luke's version was understood (and was intended) as a license to speak (fabricate) new words of the ascended Jesus.

So says Zarathustra

(who knows a thing or two about parables)

December 4, 2011

Thanksgiving and Theonomy

I'll warn you up front. The theme I'm going to be expounding is really pretty simple, so obvious and transparent that the kind of explanation I propose giving you will only serve to cloud and burden the issue. But I can't resist seeing how the phenomenon invites "explanation" in needlessly abstract, theoretical terms! Bear with me. Or not. I may be an atheist (my Catholic mother-in-law says I'm not), but I'm still a theologian. So obfuscation, you might say, is my job.

A couple of days ago, on Thanksgiving, I read a post on our Bible Geek Facebook discussion page where some of the geeks were relating what the holiday meant to them. You see, many of The Bible Geek listeners are irreligious atheists. Yet they don't necessarily want to annoy others by making themselves conspicuous in their refusal to observe Thanksgiving—no One to thank, after all. What to do on that day? Can they munch turkey with a clear conscience? Or would that be atheist hyper-scrupulosity, the very kind with which we are familiar from fundamentalist legalism?

I also learned of the President (I guess I am thankful for his exterminating Osama bin Laden) neglecting to mention God in his yearly Thanksgiving radio address. A commentator proceeded to pontificate on the "real," "proper" meaning of Thanksgiving. Obama described it as a time for appreciating good things, like the courageous service of our troops. A time for community sharing and solidarity. You bet! But Obama didn't mention God. Perhaps the President is, as Eddie Tabash says, essentially a secularist. Or maybe he cared more about not "offending" the secularist minority (e.g., my pals at Freedom from Religion Foundation) than about the religious majority of his subjects (as he seems to perceive them). It is the kind of crazy thinking that will eventually lead to the banning of religious affirmation as hate speech. (On the other hand, certain big-mouth Muslims might give some credibility to that!).

Anyway, the commentator did not seem aware of the fact that the meaning of words and customs evolves. Like Christmas, it may simply be that Thanksgiving has grown to denote the things the President highlighted, even more than literal gratitude to a Providential Creator. One of the Bible Geek listeners said he was "grateful" for the good things in his life and felt nothing particularly theistic about being "thankful" for them. And why not? I would argue that Christmas, too, has become predominantly secular even for most Christians, though no less wholesome for that, a celebration of family, childhood, and giving. Why not? What's the problem with that? I remember hearing a fundamentalist years ago quipping, "For the Christian, Easter is where the action is, anyway." The New Testament would certainly back her up on that.

Pedantic weirdo that I am, I could not help noticing how the issue of a secular Thanksgiving is a good instance of something Friedrich Schleiermacher and Paul Tillich (my favorite theologians along with Thomas J.J. Altizer and Don Cupitt!) discussed. In Schleiermacher's terms, a secular Thanksgiving would be an example of the feeling of dependence but not of Absolute Dependence, the latter being the key element of religious consciousness. You see, Schleiermacher (my beloved Professor Robert F. Streetman, AKA the Swami Streetmananda, used to pronounce it with his unrepentant Mississippi accent, as "Sligh-uh-mok-uh") explained how we are all relatively dependent on all others in our world because we are interdependent. My safety depends on drivers not being drunk, on contractors not using flimsy materials, druggists not making mistakes like Mr. Gower's or employees like young George Bailey failing to catch those mistakes. We ought to recognize this fact. But to be religious, we need to recognize an absolute dependence upon the divine and infinite totality of Being, which is traditionally called "God." (Schlieiermacher was heavily influenced by Spinoza, dontcha know.) Well, our atheists and secularists who chew up turkeys and are thankful for the chance to do so are relatively but not absolutely dependent and acknowledge it. President Obama was showing his relative dependency on the people of his excellent country. But with no larger frame of reference, there was by definition no religious element.

Tillich, borrowing some terms from Kant, spoke of a dialectic between theonomy, heteronomy, and autonomy. He says that "religion is the substance of culture," while "culture is the form of religion." It is a philosophical approach to the same insight sociologist Peter L. Berger describes as the Sacred Canopy of values, myths, and meanings that constitutes traditional cultures. Everything has its place and derives its meaning from the Great Chain of Being, to switch metaphors again. Cultures like ours, in their modernism and pluralism, lose that integrating, defining center and have to come up with an artificial substitute (like Civil Religion or patriotism), sort of like that moon of Jupiter that anciently exploded but then imploded again to form a new sphere made of the same bits and pieces. Well, Tillich speaks of historical periods in which the culture was "transparent to its divine Ground." No tension was felt between the religious worldview and everyday life or even intellectual pursuits. Laws were to be obeyed because God or the gods have given them. One pursued scientific research because nature was the good creation of God. And so on. This condition can be called Theonomy (which has nothing to do with the use of the same word by the Christian Reconstructionist movement), or "divine law." Divine law is the inner law of one's own being, so there is harmony with it unless one be alienated from oneself.

But cracks begin to form. Scientists discover things about the world and about human nature that do not square with religious dogma, The Church cracks down and prosecutes "heresy." It censors scientific achievements and artistic creations, bans books with philosophies that ignore the theological party line. In this case religion has made an idol, a false god, of itself. Theonomy has soured and turned into heteronomy (an "alien law"), a counterintuitive law that must be imposed from without, outside of the individual's conscience and better judgment. Free souls and free thinkers have no choice but to reject heteronomous religious authority and to trust their own admittedly fallible judgments, Of course this is what happened in the Enlightenment, the Renaissance, and the French Revolution. The resulting condition is autonomy, steering one's course by one's own law. One's essence is still in harmony with its divine Ground so long as one searches for Truth, Beauty, the Good, which can never be other than Divine. But the autonomous thinker naturally does not see this, given the social and institutional options open to him. The autonomous person for the moment accepts the Church's claims to have a copyright on religion and therefore rejects religion along with the tyranny exercised in its name by those who made it into an idol. This, it seems to me, is where we find our militant secularists and atheists.

Tillich would say such autonomous souls are still grasped by the ultimate concern. A real and genuine "secularist" or "atheist" would be, he says, someone who sees no depth in life, who has nothing to live for. One addicted to superficialities. And that's no atheists I know. This means atheists/secularists are still grounded in the divine Depth, in the Ultimate, though they have for the time being had to repress knowledge of the fact, given the Church's arrogation of the "religious" label for itself. You can see exactly what I'm talking about in the virtually superstitious fears some secularists have toward myth and symbol. They know these things only from religion and religion's heteronomous use of them, so they recoil in terror when they come across them. I recall a friend of mine, an ardent Secular Humanist, who was fully as wary of the Harry Potter books as any fundamentalist, and for the same reason: the books depict magic as a reality, and children must be protected from that! Yet that same Humanist was a great fan of Star Trek. The imaginative realm is fine, then, as long as there is no fantasy about the supernatural! That's autonomy so afraid of heteronomy that it shuns theonomy, too, having forgotten the difference.

In a secular celebration of Thanksgiving, I see autonomy beginning to reopen itself to the "divine" grounding of its underlying depth, theonomy. Those who stubbornly refuse to eat the sacramental turkey and instead poke fun at the day by observing Norm Allen's anti-holiday "Blamegiving" are still on the far end of the pendulum swing.

If we understand this, we can see why Tillich seems to be co-opting idealistic, dedicated atheists as "religious" despite themselves (sort of like Karl Rahner's "anonymous Christians"). It is not a sneaky tactic of some kind, like registering Mickey Mouse or dead people as voters. It is a way of understanding the irreligious sympathetically in religious terms instead of considering them enemies. Come to think of it, maybe this is what my mother-in-law Cecilia has in mind when she says I'm not really an atheist. Maybe you aren't either.

So says Zarathustra.

November 6, 2011

Costumed in Confusion

It's time to defend Halloween again. It's coming up very soon as I write, but it will be just past when you read this. The other day, Carol and I noticed two Halloween-related items. First, the local newspaper carried a story about–get this—a Halloween egg hunt. Huh? I've heard of combining Christmas and Hanukah into "Christmukah," which makes little sense to me, mainly because it would appear to obscure the meanings of both holidays that have been crammed into the blender. Well, here we go again! Easter eggs for Halloween? Is the goal to assimilate Halloween, mistakenly imagined as a pagan holiday, to Easter? I could see it, I guess, if the point was to assimilate the resurrection to a zombie or vampire story, but I doubt anyone has thought it through to that extent.

I had noticed a day or so earlier how some school or church was advertising a "Harvest Festival." True, this is a farming community, so such a celebration would be entirely appropriate. But I cannot help suspecting that "harvest festival" is just a sanitized, emasculated substitute for Halloween, just like the Secular Humanist attempts to celebrate Christmas while denying they are doing it by renaming it "Solstice" or "Humanlight." Ho ho ho.

There is a particular irony in shrinking away from Halloween in superstitious fear and retreating to a Harvest Festival or Fall Festival, because such a celebration of seasonal passage is essentially pagan, a vestige of nature worship. By contrast, Halloween (which means "Eve of All Saints Day") is a Christian holiday, mocking the powers of Evil in light of the victory of Christ. But if that's too theological for you (and I admit, it is for me these days), how about this? Halloween is an occasion to laugh at our fears (especially fear of death), which is to defy death and thus to triumph over it in the only way poor mortals can.

And that leads me to the second thing Carol and I noticed. We were watching a new episode of The Office, and the theme was a Halloween party, organized by the office staff. The new CEO, Robert California, a bit of a Zen master, complains that the costumes and decorations, the general mood, are just not scary enough. He takes one look at the "costume" sported by new manager Andy Bernard, who is dressed as a utility worker of some kind, complete with flannel shirt, jeans, and a flashlight helmet. The boss says to him, "So on this night of wild fantasy, you've dressed as a laborer." Is Andy signaling that work is a horror to him?

Kevin, Darryl, and Jim are wearing Hockey (or some sport) jerseys. Angela is a cat, Pam a rabbit. Kelly, Toby, and Gabe are wearing cutesy skeleton costumes. Stanley is a chef. Only Dwight is really up for it, decked out as a monster queen from a video game. Creed is garbed as Osama bin Laden. Erin is made up as the hamburger mascot Wendy. Robert California (not costumed) goes around unobtrusively asking most of them what they personally fear the most. At the end of the evening, he tells the gang an impromptu scare story he has woven together from their individual fears. They seem more sobered than entertained. But the boss sees that this is the whole point: facing your fears. Not fleeing them. Not pretending there is nothing to fear (perhaps in the vain hope that religion can protect you from them). But facing them as fears, even if our Halloween celebration is to some extent whistling in the dark. What's wrong with that? At least it's not self-deception.

Tillich somewhere says that the more Nonbeing that Being can take into itself, the stronger it will be. The fantasy evils and monsters of Halloween serve to incarnate the Nonbeing of our fears. By embracing them in a spirit of shivery fun, we take the Nonbeing into our own being and become stronger for it. I think that, without that jargon, the basic lesson is conveyed even to children, or at least it would be if we still really celebrated Halloween.

The demise of Trick or Treat attests this cultural failure of nerve. Back in the early 1970s baseless urban legends of candies containing razor blades frightened foolish parents into keeping their little darlings home and off the streets. Didn't they realize they were implicitly casting the pall of suspicion on their neighbors, whom they signaled they believed might be molesters and child-murderers? So kids went instead to Halloween parties in private homes, churches, or schools. That would not have been a fatal blow (major though it was). The real damage to the holiday was the trend toward sickeningly innocuous costumes. Rainbow Bright? Clowns? Bums? Sponge Bob? Princesses? Dogs?

What the hell?

This is Halloween, for Boris's sake, not some "come as a weakling" costume party! Where are the Werewolf, Frankenstein, witch, mummy, vampire, and devil suits? They have succumbed to the real horrors: the friggin' Care Bears and Barney the Simpering Dinosaur (no wonder they went extinct!). "Harvest Festivals" denote a shallow sense of life, a self-deceiving pretense that there is nothing to fear, so that courage never even comes up as a virtue.

People seem to think that fear is the thing to fear. But it is not. What is courage after all, but the determination to act, to do one's duty, despite one's fears? To act without fear is mere rashness, foolhardiness. I think of a 1990S Justice League comic written by Grant Morrison. In it, Daniel the Sand Man, a master of dreams and the subconscious, reassures Kyle Raynor, the new Green Lantern, as he is about to go into battle, unsure of his abilities to fill the shoes of his illustrious predecessor Hal Jordan. The Sandman says, "You will surpass him. You already know what he could never learn." Kyle asks, "What's that?" The answer: "Fear."

So says Zarathustra.

October 9, 2011

Is Mitt Romney a Cultist?

The other day, the pastor of First Baptist Church of Dallas, not exactly a bastion of intellectualism or fairness, lambasted Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney as being a member of a "cult" and not a Christian at all. One might dismiss the whole thing as a case of the pot calling the kettle African American (that is the Politically Correct idiom, no?), given that the pastor is a Southern Baptist. I think Mike Huckabee (also a Southern Baptist) had it right when he said Americans must be tolerant above all else, and that Romney's denominational tag is immaterial for political purposes. Indeed, the fact that his Dallas colleague sought to disqualify Romney for public office on account of his "heretical" creed is itself pretty "cultic." But the pastor's concern is an interesting one and raises a couple of important issues and opportunities for clarification, which I intend to exploit here. Hope you don't mind.

The other day, the pastor of First Baptist Church of Dallas, not exactly a bastion of intellectualism or fairness, lambasted Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney as being a member of a "cult" and not a Christian at all. One might dismiss the whole thing as a case of the pot calling the kettle African American (that is the Politically Correct idiom, no?), given that the pastor is a Southern Baptist. I think Mike Huckabee (also a Southern Baptist) had it right when he said Americans must be tolerant above all else, and that Romney's denominational tag is immaterial for political purposes. Indeed, the fact that his Dallas colleague sought to disqualify Romney for public office on account of his "heretical" creed is itself pretty "cultic." But the pastor's concern is an interesting one and raises a couple of important issues and opportunities for clarification, which I intend to exploit here. Hope you don't mind.

First, what is a "cult"? The term is commonly hurled at religions that most people don't like, minority religions which one feels it is possible to get away with offending publicly. But there is a "proper" use of the term, that is, a technical denotation. Two of them in fact, and they sometimes overlap. First, a cult is a religion transplanted from one culture into another, e.g., by way of missionary efforts, planting the religion's flag in new territory. It appears, at least initially, odd to its new neighbors who are unfamiliar with its tenets and are roused to suspicion by the simple fact of novelty. :"Whatsamatta? Ain't the old time religion good enough for ya?" Eventually the new religion becomes more familiar, even if most folks don't agree with it, and the members seem less threatening. The ancient Mystery Religions with their dying and rising gods and their secret initiations were originally at home in their Eastern agricultural settings. When many members relocated in the West through commerce, being taken as slaves, or whatever, they congregated in new urban surroundings and became Mystery Cults, since they were new and strange-seeming. Sometimes such exotic "cults" were attractive to many outsiders, like the Isis and Osiris religion and Judaism.

The cultural and ethnic foreignness makes such a new, transplanted faith seem suspicious to many, as was the case, I am sure, with the Unification Church of Korean Reverend Sun Myung Moon and the Hindu sect the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, a venerable and familiar faith in its native India, dating back to the 14th century. Yellow Peril and all that nonsense. People took one look at Reverend Moon and thought "Fu Manchu" or "Ming the Merciless." Mormonism was not foreign in origin, but it was new and different, and it did suddenly pop up in various American communities, so the effect was much the same. So it is not too far-fetched to call Mormonism (the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) a "cult" in this sociological sense. But by now, how can it seem subversive to outsiders, most of whom hear "Mormon" and think of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir? If you have any Mormon acquaintances, you know them to be nice people of good character and the staunchest imaginable upholders of traditional values. Even at that, there is a healthy range of opinions among their ranks, as witness the liberal Harry Reid.

I know what you are thinking: "Traditional values? These people are polygamists!" I hate to tell you what you already know, but even this is a traditional value, certainly older than the monogamous nuclear family. Just look at the Hebrew patriarchs Abraham, Jacob, and others. Polygyny (a husband with multiple wives) persisted into Jesus' era and survives today among Muslims, of whom there are over a billion. Like arranged marriages, polygamy is one of those practices, one of those values, we have jettisoned in favor of newer models. So you may not fancy polygamy, but it is certainly not some wacky innovation like, say, dating, romantic love (a modern Western invention and, of course, a good one) or Gay marriage.

And the major Mormon denomination officially frowns on polygamy anyway, though it remains widely practiced in Utah, where the police pretty much ignore it, being too busy out catching crooks.

There is, as I anticipated, a second denotation of "cult." A cult may refer to a religion, usually necessarily a small one, in which a charismatic leader controls the lives of individual followers, perhaps dictating marriage partners (even dissolving marriages and reshuffling spouses) and career choices. Such a cult leader may maintain a surveillance system among members. His word goes. Reverend Moon chooses who will marry whom in the notorious mass weddings. Often the spouses have never even met one another before they are matched by the Lord of the Second Advent in his Spirit-inspired wisdom. The sinister Jim Jones made life hell for many in the People's Temple, meting out cruel and unusual punishments for perceived disobedience. Does Mormonism feature anything like this? Jailed prophet Warren Jeffs sure did, but remember, he was the head of an outlaw sect, the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Was the original LDS prophet Joseph Smith a cult leader in this sense? I should think believing, ground-floor Mormons were pretty eager to obey his every behest, as many of us would if we were in the same situation (not that we should). But the larger a faith community grows, the quicker such a stage will be left behind. There will be too many Indians and not enough chiefs to keep an eye on them. The prophetic decrees of the founder will have been laundered and whittled down, the weird and arbitrary elements, anything unworkable, quietly trimmed away. Thus, as Max Weber said, charisma is routinized, and charismatic authority (with its arbitrariness) yields to legal authority (with its regularities). So I think Mitt Romney's religion is no longer a cult.

But is it a heresy? Is it no longer Christian? It is not Trinitarian. It adds the Book of Mormon (strictly irrelevant to LDS beliefs), the Book of Abraham, Doctrines and Covenants, and The Pearl of Great Price into its scriptural canon. They believe the angel Moroni appeared to Joseph Smith and charged him with restoring genuine apostolic Christianity (just like many other sect founders) and sent him to dig up the Golden Plates of the Book of Mormon which recounted an ancient voyage of Judeans to American shores, eventually giving rise to the Indian tribes. These are not exactly standard brand Christian tenets. These beliefs mark Mormons off from mainstream Christians, who may debate over infant versus convert baptism but who do not practice baptism for the dead (as the Mormons do, based on 1 Corinthians 15:29, and as the ancient Marcionites and Cerinthians did).

The question is: how do we define Christianity? Who has the copyright on the term? Who is entitled to draw up the ruler against which would-be Christianities are measured, qualified or disqualified? I reject that approach as utterly unhelpful. I want to draw distinctions, too, so we can clarify things. But there is a better way to do it. We can construct a basic "ideal type" or textbook definition of "Christianity." It will not cover every detail or department. Some supposed Christianities will fit the paradigm better, more closely, than others. That is okay, for the goal is not to see which faiths can be neatly stuffed into the box labeled "Christianity." Rather, the idea is to provide coordinates along which each type of ostensible "Christianity" can be measured, and this is merely descriptive, implying no value judgments.

Let's take one particular coordinate. It would be reasonable to posit that any form of Christianity would be Christocentric. Jesus Christ would be the central figure, the mediator between God and the human race. Jesus is quite important in Islam but by no means central. That place of honor belongs instead to the Prophet Muhammad, who has superceded him, just as in the Baha'i Faith Muhammad has been superceded by Baha'ullah. This is why we do not consider Islam part of, a type of, Christianity (or the Baha'i Faith part of Islam). What about Lutheranism or Wesleyanism? The respective founders are very important as interpreters of Christian faith, even as normative ones, but they are not central. They do not threaten the centrality of Jesus Christ. A wonderful old story recounts how a devout old lady interrupted a polemical sermon taking sides in the raging debate between Calvinism and Arminianism. She urged the preacher to forget about John Calvin and Jacob Arminius and to get back to Jesus Christ! Such a rebuke made sense because neither Calvin nor Arminius are supposed to have nearly the same importance as Jesus Christ does in either system. If Jesus has been pushed out of the spot light, something is wrong because Christianity of any stripe is by definition Christocentric.

But the same is not true in the Unification Church. No one would say, "Enough already about Sun Myung Moon! Stick to Jesus!" In Unificationism it is understood that Reverend Moon occupies the prophesied role of the Lord of the Second Advent, he who is destined to bring the work Jesus began to final fruition. Thus Jesus is no longer quite central. No mere appendage or predecessor, not a forerunner like John the Baptist was to Jesus, and surely a tough act to follow. But his successor is taking the stage. The ellipse has two foci, and the focus is shifting to Reverend Moon.

I should say the same thing has happened in the case of Mormonism, where Joseph Smith is more important than Luther for Lutherans, Wesley for Wesleyans. But Joseph Smith is not so important as Jesus. After all, the movement is called "the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints," not "the Church of Joseph Smith." But the focus has shifted a bit, maybe more than a bit.

In short, in a merely descriptive sense we could say that both Unificationism and Mormonism fall farther from the Christocentrism coordinate than Lutheranism, Calvinism, etc., but not quite so far as Islam does. Mormonism may be on its way to becoming a separate religion, though it has not arrived there yet and may never do so. Is this way of charting it out messy and inconclusive? Why, yes, but that's the only accurate way to view the matter. Reality is messier than the categories we rightly use to analyze it. A ruler is for measuring. It is not the same thing as a carpenter's straightedge which you use to cut away whatever does not neatly conform to pattern.

So is Mitt Romney not a Christian? Is Harry Reid? Is John Huntsman? Is Glenn Beck? Was Brigham Young? It is hard to answer that question precisely because it demands a degree of clarity that does not exist. It demands that the factual phenomena fit squarely into boxes, but that is not what religious tags refer to. They are ideal types, coordinates by which to measure and tools to understand the uniqueness of every particular item we examine. The question is not "Is a Mormon a Christian?" but rather "What is a Mormon?"

And if both Reid and Romney can be Mormons, I cannot see why anyone should worry about Mormonism dictating an office-holder's politics in any particular direction.

So says Zarathustra.

September 9, 2011

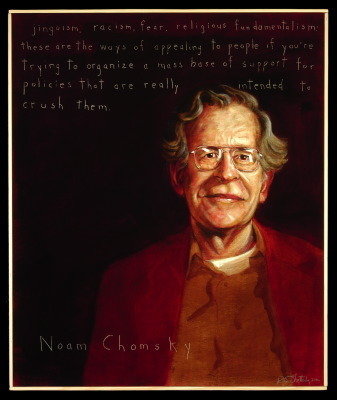

The Roaming Noam

I just watched the Noam Chomsky documentary Manufacturing Consent and enjoyed it very much. Chomsky comes across as unassuming and humble, a man enduring what he has to both in labor and in reprisals, for pursuing the course he believes destiny has assigned him. Very likeable. And admirable.

Yet I can't help thinking he is seeing a conspiracy where none exists. He is an anarcho-syndicalist and therefore despises any form of government (and all give plenty of reasons to do so!), and this is inevitably going to mean he is going to barrage them with criticism no matter what they do, for existing at all. He aims his thunderbolts from an empty heaven of pure theory that is never sullied by no-win situations and lesser evils. He does not propose an alternative type of government, but merely wishes there were a vacuum, and he would try to prevent human nature from filling it, as it did in the beginning and would do again. It is not a conspiracy for there to be government, though a relatively small number of people are in charge. That is theoretically no more than specialization, though in fact an oligarchy/plutocracy may develop (I think of Leonid Brezhvev, man of the people, with his collection of luxury cars). But somebody would rule, and we would want somebody to, to protect us. Even if the best candidate were Tony Soprano.

I found it remarkable that Chomsky admitted both that this is the freest society in the world and that it had been necessary to sacrifice that freedom temporarily to survive during WW2. Doesn't that tell him anything? Like maybe that government isn't necessarily so bad? And that occasional control over human behavior (which is what any government is, after all) isn't necessary only when Hitler looms?

I loved what Chomsky said about the Superbowl and other popular idiotic entertainments, how they are mere distractions to give the cows some cud to chew on instead of thinking about anything important. And yet I think Dostoyevsky rings truer: people want such bread and circuses, because they shun the burden of real thought, responsibility, and decision. There is not some secret cabal that keeps them hypnotized. No such thing is necessary (alas!).

I've read enough of the Utne Reader to know that certain news stories are never allowed coverage, but it is not necessarily a result of corporate interest. When it is, it may be an exception, as when everyone knew CBS killed a story on Big Tobacco because they wouldn't be able to afford the lawsuit they were threatened with. People despised and derided CBS for this. Which implies it doesn't happen all the time as a matter of policy. My guess is rather that the choice of news has more to do with the Family Feud model–what do the average viewers want to hear about? Surely that is the reason there is time wasted with sports "news" daily. In other words, I suspect a lot of what Chomsky attacks comes from the ground up, from the grassroots, not from the top down. And that is far more depressing.

Conspiracy theories are the most optimistic theories around! They centralize and simplify our problems. They are demythologized versions of the Christian belief in Satan. Stop me if you've heard this one before, but shortly after the 1978 Jonestown suicide I was talking with a professor at Gordon Conwell Theological Seminary, and he asked me (rhetorically) if I didn't think these events were not a compelling demonstration of Satan's power. I replied that I didn't think so at all. Instead I took the whole terrible business as more evidence of the awful capabilities of human nature. If you think you need a devil to account for the Holocaust, you are a cock-eyed optimist! "Everything would be fine if we could just get rid of that horned, hoofed terrorist!" Don't kid yourself. The problem is much more complex than that, and so is any possible solution. Same thing with secular conspiracy theories. They are imaginative schemes to find a scapegoat with a single face. They tend to absolve us of collective guilt and the complicity of our institutions as a whole. If you blame the Ku Klux Klan for our race problems, you are avoiding the much, much larger problems of institutional racism. (Not that the KKK deserves any mercy or even patience!)

You might wonder what Noam Chomsky thinks about 9/11. Surprisingly, he does not believe there is anything to the conspiracy theories. But this turns out to be the exception that proves the rule, since he suspects the Bush administration purposely fueled such conspiracy theories in order to distract the public from other nefarious actions the administration was performing! Nevertheless, the "Truther" movement seems Chomsky-esque to me. And it reveals the peculiar perversity of hate-America conspiracy theories. This is one of those rare instances where we do have an actual sinister conspiracy: Al Qaida—and it isn't good enough for paranoids like theologian David Griffin. No, the World Trade Center demolition had to be the work of an even more sinister conspiracy, one worthy of an espionage novel: our own government took down the towers and killed 3, 000 of its own citizens, and this for no particular reason. (There were certainly better excuses, true or false, to attack Iraq.)

I was interested to hear from Chomsky, in answer to a simple question, that he gets his information about what is really going on in the world, not from the sold-out propaganda mills of the American news media, but rather from newspapers in other countries—which, presumably, are as objective as the day is long. Somehow, though working within societies that are anything but free, whose newspapers are not just de facto but de jure propaganda arms of the controlling juntas, these papers and broadcasts tell the unvarnished truth.

It reminds me of the college freshman who learns just enough anthropology to become convinced of Cultural Relativism, which he construes to mean: everybody is right except for the United States. "My country, wrong or wrong."

Don't get me wrong: I am far from trying to pretend everything is right with America, especially with her government and her policies. Far from it! I am by now pretty cynical. But nobody (e.g., Ron Paul, Pat Buchanan) is going to get me to believe that theocratic, nuke-toting Iran is harmless and that America ought to be spelled with a "k."

So says Zarathustra.

July 30, 2011

No Truth but this One?