Robert M. Price's Blog, page 4

October 2, 2016

Chasing the Bus

Once Tony Soprano shared an insight with his therapist. He had “mother issues,” you see. Pretty serious ones: she wanted to have him rubbed out—and tried! Anyway, Tony said our mothers are like buses that drop us off and drive away. We ought to be grateful for the ride. Instead, we chase after the bus, desperate to get back on. Naturally, the wisdom of Tony is applicable to much of life, but here (all too predictably) I want to apply it to our interest in the Bible. What’a ya gonna do?

Once Tony Soprano shared an insight with his therapist. He had “mother issues,” you see. Pretty serious ones: she wanted to have him rubbed out—and tried! Anyway, Tony said our mothers are like buses that drop us off and drive away. We ought to be grateful for the ride. Instead, we chase after the bus, desperate to get back on. Naturally, the wisdom of Tony is applicable to much of life, but here (all too predictably) I want to apply it to our interest in the Bible. What’a ya gonna do?

I am right now working on a book called Bart Ehrman Interpreted. Like me, he was once a fundamentalist, then an evangelical, then an agnostic, and finally an atheist. It happens to a lot of us. In this evolutionary path many factors are at work, but one of the biggies, one might even say the fulcrum, is the Bible and our devotion to it. We get on the Bible Bus in our early years, eager to ride it to heaven! We have been told it will get us there as we take an exciting ride through the exotic neighborhood of the Old Testament, the shining landscape of the New Testament, the farther lands of Church History and Theology. So in order to appreciate these sights all the more, we study up on the guidebook, the Bible and commentaries on it. But every once in a while we are surprised to hear the sputtering ring of the stop signal, and the Bible Bus pulls over to let someone off. This surprises and concerns us! Why would anyone want to disembark from the Bible Bus? It’s so comfortable! The company is so pleasant! The group singing is such fun! Why? We are mystified.

That is, until we find ourselves reaching for the stop cord and getting up from our seat. Now we know why the others did the same. The closer we studied that guidebook, the more troubled we became. There were certain… discrepancies. Hell, was the bus actually going anywhere? We could swear we saw some of the same sights more than once! Were we just going in circles? Were we even moving?

Occasionally we look at the neighborhood we got dropped off in, and it looks pretty drab compared to the storybook paradise we used to think we were headed for. And in that moment, we think, as Tony Soprano said, of chasing that bus, or maybe waiting for another one to come along. But when one does, we realize we don’t have the required fare to get on. We’re plumb out of credulity! We’ve lost the overriding will to believe, otherwise known as the will to make-believe. So we start exploring the new neighborhood. Most of us sooner or later find new accommodations, discovering that living in the real world is not so bad, that it’s pretty good in fact, better than the fantasy dreamscape that once beguiled us.

But there are some of us, like Bart Ehrman, me, and a huge number of others, who manage to sneak back onto the bus, but we’re riding on the bumper!  We feel good being back on the Bible Bus—but without getting in! We got hooked on the Bible, and the hook went deep. It might be pretty hard to get it out without disemboweling ourselves! The Bible has become part of us, like it or not. But then what’s not to like?

We feel good being back on the Bible Bus—but without getting in! We got hooked on the Bible, and the hook went deep. It might be pretty hard to get it out without disemboweling ourselves! The Bible has become part of us, like it or not. But then what’s not to like?

We hopped off the bus in the first place because the bus was arriving at a crossroad. We wanted to understand the biblical text better and better, as all Bible-believers are supposed to want to do. But even to have gotten to this point we had already worked our way half-way off the bus without realizing it, because everybody in the seats around us wasn’t really that curious about the Bible. They just wanted to cling to the proof texts that promised them admission to Heaven. In fact, they may have been reluctant to explore the rest of the Bible precisely because it might complicate the picture, might loosen their tight grip on that hand full of cherished, out-of-context verses.

And that’s what had happened to us. We saw the crossroads approaching: we would have to decide whether we were more interested in Christian faith or in the Bible, because we saw we couldn’t have both. We had found that the religious beliefs about the Bible were a hindrance to understanding the Bible. “Hmmm… here’s a contradiction! But, oh yeah, there can’t be any contradictions in the Bible! So I guess they’ll have a clever solution to the riddle when I get to heaven!” But we got tired of that after a while. We began to wonder. “Suppose it is a contradiction? How would that have come about? Two different sources editorially combined? Two different writers’ opinions? But if they’re only opinions, that means they’re not ‘revelations’… But it makes more sense that way! Do I want to find out the truth? Or do I want to keep chanting those proof-texts?” That’s where we got off.

And back on, on the bumper—and under the bus, to see exactly how it worked.

Hegel and Kant couldn’t and probably wouldn’t have used a stupid analogy like the one I’ve beaten to death here, but they were making a related point. For them, the Bible and supernaturalist religion were storybook versions of moral instruction for the childish of mind. Kant said that the miracles were like parables, simply a means to an end; if they got their point, their lesson, across, fine. But if not, who needs ‘em? And if they do their job, who needs ‘em either?

It’s much like Zen. The monks found the old doctrines and techniques ineffective in producing Satori, Enlightenment, so they invented new gimmicks like the answerless riddle of the koan (“What is the sound of one hand clapping?”) designed to launch you off the track of mundane reasoning into a higher stratosphere. The main insight of Zen was that, a la Kant, if the old trappings of religion did not do the trick, to hell with ‘em!

But, as I said, even if they did, who needs ‘em? If they served their purpose, if they got you there, isn’t it kind of like keeping the Coke bottle after you’ve finished the soda? I love the Buddhist parable of the Raft. Imagine a man fleeing an angry mob through the forest. Luckily, he has a good head start. He stops short at a riverbank. He’s got to get across! But there’s no bridge, no stepping stones, and those crocodiles aren’t helping either! What are his options? After a moment’s thought, he begins gathering bamboo stalks and binding them together with tough vines. Soon he’s got a makeshift raft and begins poling it across the river, just as his pursuers arrive at the river. They shout curses and shake their fists, but there’s nothing more they can do. (I’m tempted to say their quarry gives them the finger, but I guess that’s inappropriate for a Buddhist parable.) Well, he makes it across. He’s safe! Now what do you think he ought to do with that raft? Out of gratitude to the raft, should he strap it onto his back and carry it around like a tortoise shell? Of course not! What a useless encumbrance it would be! Better just to dump it and get moving!

In the same way, the various features of religion are purely instrumental in nature. I just ate a couple of yummy fiber brownies. Is there any reason to keep the wrappers? No, they served their modest purpose, and now it’s time for them to exit Stage Garbage Can. You discard them precisely because they did what they were designed to do! One might object that this analogy is apt only for Eastern religions, where the goal is one’s own Enlightenment. In a paradoxical sense, it is “self”-centered. But in Western religion it is (supposedly) quite different: religion is centered on God. Worship benefits the worshipper, sure, but in the same way turning toward the sun benefits green plants, because it nourishes them. We are made to worship our Creator, so things are out of whack if we don’t. But God deserves the acclaim.

And yet I think the difference is finally overcome, since in Vedanta Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism one seeks to break down the (illusory) wall between Self and Other, to realize the unity, actually the identity, of the individual atman “within” and the universal Brahman or Sunyata “without.” This amounts to the humble self-abnegation of the individual in favor of the all-inclusive One. This seems to me quite parallel to the worshipper losing himself in the Worshipped.

Anyway, I think the Bible contradictions that shook us loose from fundamentalism are in effect biblical koans. They bring us to the end of faith and bid us jump off the track of conventional religious belief. They catapult us into Enlightenment (think equally of the European Enlightenment or of Eastern mystical Satori), and once they do, we can discard them—because they’ve served their purpose! The Bible nudged (or slapped) us awake so we wouldn’t miss our stop.

So says Zarathustra.

September 11, 2016

Politics and Paradigms

Political opinions are like scientific theories: they are cognitive frameworks through which we seek to make sense of the flood of disparate information. Otherwise we are left standing amid a roaring storm of raw data. We realize we must “come in from the cold” of confusion. Furthermore, we need to. We have to formulate a strategy to go further. We need to draw a map if we are to get anywhere, especially where we want to go, whether it is scientific research one is pursuing or a decision on how to vote.

As Thomas Kuhn explains in his classic study The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, a workable paradigm is one that will enable predictability. “If we’ve got it right so far, this or that ought to happen next.” “If we are understanding how these factors work together, we ought to get these results; so-and-so should turn up in the next experiment.” If you don’t get the results predicted by your theory, your theory is apparently wrong. Back to the drawing board! No shame in that. You learn from your mistakes. You reduce the possibilities. It’s the process of elimination.

Suppose the experts have long rallied around a consensus paradigm that has worked pretty well, but there remain stubborn anomalies: things, phenomena, that resist incorporation into the paradigm. Clashing data that we wouldn’t have expected. What to do? There are two possible courses. One might propose ad hoc hypotheses for this and that bit of troublesome data, contrived though they may sound even to those who propose them. Are you going to give up the theory that deals successfully with 90% of the data because of the square pegs constituting the remaining 10%? I’ll get to the second option presently. But how about a couple of examples to flesh out the abstraction?

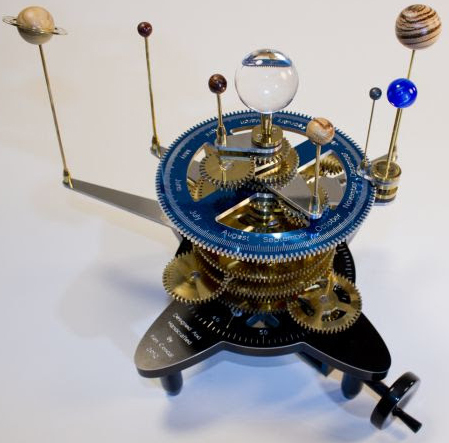

I guess the classic instance would be the astronomical paradigm shift Kuhn discusses so well. The trouble centered around the problematic “retrograde motion” of the planets. Classical Ptolemaic astronomy posited geocentrism: all the heavenly bodies rotated around the earth in regular circular orbits. Ptolemaic astronomers knew something was amiss because the planets didn’t quite follow their expected courses. Every once in a while they appeared to double back, bob around, then continue on their way. Aristotle thought the planets were sentient beings and just felt like doing a little Two-Step now and then. Later astronomers took a different approach, positing a super-complex system of wheels within wheels, like gears in a watch, atop which the planets rested, borne along on this elaborate mechanical lattice. And it worked! Reverse-engineered from the observed motions of the planets, the system of “epicycles” did fit the phenomena (and sailors still use sextants to navigate on the basis of the Ptolemaic system). But of course it couldn’t predict any new results.

But Nicolai Copernicus thought he could do better. Suppose the earth was merely one of the planets rotating about a central sun? In this case, the retrograde motion of the planets was not real motion on the part of the heavenly spheres. Instead it was all the result of shifting perspectives. The orbits were regular, but our platform of observation was moving, too! This allowed a much simplified method of calculation. Eventually Copernican, heliocentric astronomy won the day. Ptolemaic astronomy was consigned to the Museum of Obsolete Theories.

But Nicolai Copernicus thought he could do better. Suppose the earth was merely one of the planets rotating about a central sun? In this case, the retrograde motion of the planets was not real motion on the part of the heavenly spheres. Instead it was all the result of shifting perspectives. The orbits were regular, but our platform of observation was moving, too! This allowed a much simplified method of calculation. Eventually Copernican, heliocentric astronomy won the day. Ptolemaic astronomy was consigned to the Museum of Obsolete Theories.

From this case we can derive the major criterion for preferring one paradigm over another: the paradigm that makes the most economical sense of the data, and without having to posit far-fetched ad hoc hypotheses, is the better model. It’s an application of Occam’s Razor: the simpler explanation is the best. Is the truth always simple? Maybe not, but until we find out differently, we have to go by probability. And almost by definition the simpler explanation is more probable. Why bother multiplying redundant explanations when a simpler one cuts to the chase? There’s just no reason to add in needless complexities.

The second option for dealing with anomalous data is to start with it, theorize a new paradigm based on it, then see if the result can be reconciled with the old paradigm. Newton and Einstein found they were able to make new sense of what had remained baffling for Copernican astronomy, but without having to overturn the whole system. Their adjustments didn’t amount to a new set of contrived epicycles posited to rescue the old paradigm. It all proceeded inductively, and the data now made mutual sense in the same framework, all given equal weight.

It may take a long time for a new paradigm to prevail among the experts, because it must prove itself the superior option, and that quite properly requires a lot of detailed scrutiny. It is possible that some experts who have a big investment in the old paradigm (because most of their professional work was based on it) may have selfish reasons for opposing the new model, but usually that will only prolong a needful process, and most experts will welcome the new approach once they see its advantages. After all, they’re in the game because they want to get closer to the truth, not to defend some hobby horse or party line. At least one hopes so.

The same procedure obtains in biblical studies. For instance, scholars had long pondered the relation between the Synoptic gospels: Matthew, Mark, and Luke. They have much in common, almost verbatim. Why? It seems the three texts are interdependent in some way. But which way? Eventually, most scholars came round to accepting the Two Document Hypothesis, also called Markan Priority. In short, the paradigm runs like this: Matthew and Luke each independently copied material from Mark, making various changes in detail. This would explain the material shared by all three gospels. But there is also a large amount of sayings and stories shared by Matthew and Luke but with no parallel in Mark. Where did this stuff come from? There must have been a second prior source that Matthew and Luke used just as they did Mark. We call that one “Q” from the German word for “source,” Quelle. (Still awake?)

Scholars who accepted this way of making sense of the Synoptic material soon spotted anomalous data, sand in the gears of the paradigm: what to make of several places where Matthew and Luke do not quite agree with Mark but do match each other’s wording? Doesn’t that suggest that Matthew was using Luke or vice versa? It might! Starting with these data that did not fit the Two Document Hypothesis, some scholars have proposed various alternative models. Some say Mark combined material from Matthew and Luke, fusing (harmonizing) them as best he could and leaving the rest on the cutting room floor. Others suggest that Matthew used Mark, and then Luke used both Mark and Matthew. Still others think Luke used Mark, and then Matthew used both Mark and Luke. Thus there needn’t have been a Q document. When, e.g.,

Scholars who accepted this way of making sense of the Synoptic material soon spotted anomalous data, sand in the gears of the paradigm: what to make of several places where Matthew and Luke do not quite agree with Mark but do match each other’s wording? Doesn’t that suggest that Matthew was using Luke or vice versa? It might! Starting with these data that did not fit the Two Document Hypothesis, some scholars have proposed various alternative models. Some say Mark combined material from Matthew and Luke, fusing (harmonizing) them as best he could and leaving the rest on the cutting room floor. Others suggest that Matthew used Mark, and then Luke used both Mark and Matthew. Still others think Luke used Mark, and then Matthew used both Mark and Luke. Thus there needn’t have been a Q document. When, e.g.,

Luke sometimes matches Mark but other times matches Matthew, this would be because he sometimes preferred Mark’s original, sometimes Matthew’s revised version.

I am a partisan of the Two Document (i.e., Mark and Q) Hypothesis. The scholars who advocate the alternative solutions I just mentioned obviously feel it necessary to junk the formerly regnant model, just as Copernicus overthrew the Ptolemaic model. I do not. I think the Two Document Hypothesis requires only minor adjustments. It seems to me that the Matthew-Luke agreements against Mark simply imply that Matthew and Luke were using an earlier edition of Mark which contained the reading Matthew and Luke have in common, and they preserved the original Markan wording. But the specifics don’t matter for our purposes. I’m just trying to give a general impression of how the contest between theoretical paradigms works.

But things get more complicated still! There are also so-called “incommensurable paradigms,” which are invulnerable to change. You see, the closer you look, the more it begins to look as if the criteria for the plausibility of a paradigm (and for whether their adjustments look like special-pleading “epicycles” or rather extensions of the paradigm to incorporate hitherto-anomalous data) are functions of the paradigm itself, i.e., contained within the paradigm. For example, what are readers to do with the fact that, though all four gospels show Peter denying Jesus three times, each gospel has Peter talking to different bystanders? Fundamentalists, who take it on faith that there can be no contradictions in the Bible, find it perfectly natural to posit that Peter denied Jesus six or even eight times, in order to fit in all the denials with their varying details. If the explanation comports with the doctrine of biblical inerrancy, it automatically looks good! That’s their criterion for plausibility.

But critical scholars do not hesitate to say that the gospels contradict one another and that the various gospel writers simply changed the details for whatever reason. To them it seems patently ludicrous to suggest that Peter denied Jesus six times. Why? Because these scholars have rejected inerrantism as a workable paradigm. And why? On account of a different, equally important Protestant axiom: scripture must be interpreted according to the “plain sense,” what the words would seem to mean prima facie. Otherwise you can treat the Bible like a ventriloquist dummy, making it mean whatever you want it to. And no one would read the gospel texts as recordingt six denials unless they were desperate to get out of a tight spot.

There can be no real communication, not even any debate, between these factions. There is no common ground. As Stanley Fish (Is There a Text in this Class?) says, we are dealing here with two insulated “communities of interpreters.” Within each herme(neu)tically sealed community of interpreters there can be much debate and dispute, as when fundamentalists argue over whether the inerrant Bible teaches free will or predestination. Or as when critical scholars discuss what might have motivated the various gospel writers to recast the walk-on roles of the various bystanders in whose ears Peter denied Jesus. But debates between the two communities are useless. They cannot help talking past one another. Everybody ends up where they started.

This is where politics comes in. Having political discussions with your friends (who are not likely to remain your friends for long!), you quickly notice you are getting nowhere, and so are they. Each of you is starting from within a self-contained paradigm from which your opponent’s perspective seems baffling. Recently I was a guest (or was that “sideshow freak”?) on a podcast where I was called to account for my support for Donald Trump. My stunned hosts could not conceive of an atheist skeptic supporting Trump, opposing abortion, doubting Global Warming, etc. Likewise, I could not believe my ears at their arguments for “gun-free zones,” etc. Each side has different criteria for plausibility, deductively derived from their paradigm itself. These criteria will determine how one views data that seems to challenge one’s position. It was clear to me that neither side can make any headway until they dare to question their presuppositions, to ask themselves the question emblazoned on a bumper sticker: “What if you’re wrong?”

Each side of the political divide lives in what Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann (The Social Construction of Reality) call a “symbolic universe,” an internalized paradigm for construing data. Each side engages in “cognitive world-maintenance.” Each individual is reinforced (like a religious believer) in his convictions by surrounding himself with those who share his viewpoint. For instance, if you watch FOX News, as I do, and you hear people mock “Faux News” it is at once obvious they have never watched it. They are parroting the biases of the ideological “in-crowd” whose mockery is what Berger and Luckmann call a “nihilation strategy” aimed at discouraging one’s fellows from ever taking seriously any arguments from the other side. I am familiar with nihilation tactics from religious apologists who reassure their minions that biblical critics hold “skeptical” views only because they begin by arbitrarily rejecting the supernatural. That is nonsense, but they need to believe it in order to pre-empt any serious consideration of critical views. Political conservatives and liberals explain how the opposing faction suffers from psychological handicaps which incline them to their ill-founded opinions. Have you ever seen a more blatant example of the genetic fallacy?

Paul Watzlawick (How Real Is Real?) discusses the “self-sealing premise,” a belief or opinion or party-line that is invulnerable to disconfirmation by any objection, refutation, or contrary data. There is always a quiver full of explanations, excuses, rebuttals, whether consistent with each other or not. Remember, any argument supporting the presupposed position automatically sounds good, persuasive, and more than plausible to the one who offers it. And the defender is not pretending to believe these rebuttals: he really finds the excuses and alternative readings of the evidence to be convincing no matter how lame they sound to outsiders. (This is the larger reality of which the phenomenon of “confirmation bias” is the iceberg tip.)

This all raises the spectre of falsifiabilty. Karl Popper pointed out that some assertions are revealed, not as false, but as meaningless when the one making the assertion cannot think of any state of affairs that would falsify his assertion. You cannot really even define the state of affairs that is being asserted if you cannot specify what conditions would be inconsistent with it. My favorite example here is, not surprisingly, a theological one. If a religious believer asserts that God is in loving, providential control of the world, we would sort of expect this “hypothesis”

to have predictive value. Wouldn’t it seem to imply that God would protect us from tragedy and atrocity? But the facts do not seem to bear this out. Does the believer admit he was wrong? Not at all! He retreats to the position that God is in control, but that “he moves in mysterious ways.” But then we have to ask: if God’s being in providential control winds up looking just like God not being in control, what’s the difference? What, if anything, is even being asserted? If nothing counts against the claim, then there really is no claim.

And it is the same with political stances. You advocate policies that will, you claim, create more jobs and revitalize the economy, but there are no discernible results. Rather than going back to the drawing board or admitting that your opponents were right, you either “reinterpret” the statistics or stonewall with excuses, perhaps blaming the disastrous results of your policies on the previous administration’s policies which, you say, screwed up the economy worse than you first thought, so you double down on your failed policies. And when they fail again, you will sink still deeper into denial and excuse-making. The policies themselves have become the most important thing, not the goals to which they were originally dedicated.

Next step? Whatever destructive results the policies bring, even once they become undeniably obvious, will be considered noble simply because they are the results of the policy and the ideology underlying it. This is what happens when gun control advocates insist on reducing gun ownership by non-criminals. You would have assumed that safety and crime-reduction were the desired goals. But if, as in Chicago, New York City, and Brussels, the reverse happens, well, that’s still good. These murders were “collateral damage,” an unfortunate by-product of the inherently noble crusade to eliminate those nasty guns. Of course, criminals won’t cooperate, but let’s get rid of as many of those unholy and unclean guns as we can, and you can take them away from law-abiding citizens. “Oh,” you say, “but once we tighten gun laws, gun-owners ipso facto become criminals!”

Fossil fuels are inherently evil and unclean, so we must try to get rid of them. If this will destroy whole industries and many people’s livelihoods and make energy too expensive for the shivering poor, well, that’s just collateral damage! It’s all like pacifism: self-imposed martyrdom for the sake of ideals derived from abstract systems of political theory.

Theory is paramount in politics. Government ideologues attempt to reshape the world to make it conform to their theory’s picture of the world, as when George W. Bush sought to impose Western-style democracy on alien cultures, or when Obama thinks all he needs to do when Russia invades Ukraine is to pontificate that Russia is “on the wrong side of history.”

Worse yet, their policies assume the world already does correspond to the picture their ideology paints. Muslims can’t be terrorists, so they’re not! If you think otherwise, my friend, you suffer from Islamophobia! Crimes must be equally distributed among all population groups, so to claim one group commits a disproportionate amount of crimes can only be racist slander.

Committed to an ideology, the ideologue is living in an impenetrable bubble. Freud’s characterization of religion fits equally well here: “the projection of a wish-world onto the real world.”

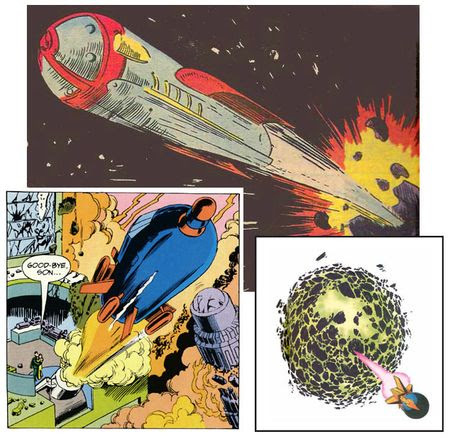

Peter Berger (in his The Heretical Imperative) speaks of “relativizing the relativizers.” Once a sociologist of knowledge (like him) succeeds in showing the largely psycho-social origins of any individual’s beliefs, the ground is cleared. We are left with no escape, no option but to try to bracket what we have been taught to think, what we would like to believe, and to try our best to look at the facts inductively. And to ask ourselves why we are inclined to one or another interpretation of the facts. Look, I know that voting is a forced choice. You’ll never get to the polling place if you think you have to master all the facts on every question. But you owe it to yourself (and everyone else) to take a cold, hard look at the facts, and at yourself as the evaluator of facts. Take your best shot. Take what Don Cupitt calls “the Leap of Reason,” launching yourself out of your confining paradigm like baby Kal-el rocketing out of exploding Krypton!

So says Zarathustra.

Launching Beyond Your World

Launching Beyond Your World

August 4, 2016

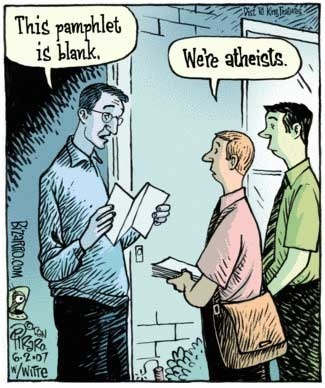

The Value of Theology for Atheists

Richard Dawkins

Richard DawkinsRichard Dawkins has ventured the opinion that theologians are experts in a subject without any subject matter. I take him to mean they are engaged in nothing but “mental masturbation.” They are, he thinks, like a group of Star Wars fans I once knew who believed the events of the movie were real, but in a different universe (in which they would have much preferred to dwell). Or imagine a self-proclaimed zoologist who specialized in werewolves, unicorns, and dragons. There is a large element of truth in such comparisons and thus also in his disdain. And yet I can’t help thinking he is engaging in overkill.

I am sure Professor Dawkins does not discount the importance of numerous fields like Anthropology, Psychology, and Sociology of Religion, much less the History of Religion, because these fields of study serve purposes valuable to secular intellectuals and to society at large. To put it bluntly: you need to know your enemy. The world is aflame with murderous religious fanatics, and we need to understand what motivates those who kill “infidels” with clean-conscience and abandon. We need to know the harm such jihads of madness have done in the past if we want to gauge dangers in the present.

Biblical Studies are, obviously, relevant if only to, as Robert Ingersoll did, demonstrate that the threatening gun is loaded with blanks, to render the Bible useless as a tool of oppression. It is imperative to debunk the notion that the Bible is the infallible Word of God, and this is true even if you think what the Bible says is not so bad, because it is still used as a ventriloquist dummy to impart divine authority to those demagogues who claim its inerrancy for their own opinions. I can think of people on the Left as well as the Right who make Scripture into their own private Charlie McCarthy.

My friend Hector Avalos has called for “the end of Biblical Studies” (in his great book of that title). What, is he trying to put himself out of a job? No, he means to call the bluff of those who merely use scholarship to defend the Bible in the manner of apologetics—spin-doctoring. A good example would be the study of “Biblical Archaeology,” which was essentially founded as an elaborate campaign to defend the accuracy of the Bible against the skepticism of the Higher Critics of the Nineteenth Century. Now this axe-grinding pseudo-archaeology has been revealed as cut from the same cheap cloth as “Scientific Creationism.” The new Ark replica unveiled by Ken Ham is a prime example of both.

What is less obvious as a piece of biblical PR, and from an unexpected quarter, is the sophisticated (but sophistical) production of scholarly studies that attempt to show that the Bible really supports equal rights for women and homosexuals, opposes colonial imperialism, fosters ecumenism, etc. The goal here is twofold. First, there is the cynical, Grand Inquisitor-like attempt to use the voice of unearned authority to trick the pew-potatoes into voting for so-called “Progressives” because the Bible is “really” on the Left, and so you should be, too. It is propagandistic manipulation, what some Liberation and Feminist Theologians call “a useable past.” You know, like the Ministry of Truth in Orwell’s 1984.

But the flip side of that coin is that such scholars also seek to rehabilitate the Bible’s reputation by arguing that it has good “Progressive” things to say (and that the bad stuff is either irony or interpolation). Why do they want to do that? Possibly to justify clinging to a self-identification as a Christian of some type.

I understand Hector to be calling the bluff of both Conservative and Liberal scholars who are grinding “the axe of the apostles.” I don’t read him as demanding that the study of the Bible be banned or boycotted. Rather, I would describe the situation as analogous to a bunch of neo-polytheists urging everyone to take Hesiod’s Theogony and Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey as infallible and historically inerrant. Classicists would enter the fray to demonstrate the mythic-fictional character of those works, but they would not discourage the study of these great old texts.

I think another friend of mine, John Loftus, means the same thing when he urges universities to drop Philosophy of Religion courses. So much of it has been (again) apologetics, propping up the faith of those would-be believers whose intellectual consciences forbid them to exclaim, “Oh, to heaven with it!” and just “believe.” (Still, you can teach Philosophy of Religion with a critical approach.)

I’m not sure Professor Dawkins stops there, however. I remember hearing him deride the Catholic doctrine of Transubstantiation as “a rabbi turning himself into a cracker.” The line got lots of laughs, but I didn’t join in the general hilarity. I knew from this joke that the noted atheist was not bothering to try to look at the question from the inside, the only place it makes any sense, and where it does make sense. It is its own language game, though most of those who play it are not aware that’s “all” they’re doing.

If you’ve been on the “other” side, whether religiously, politically, whatever, then switched sides, you know you can’t simply dismiss the old frame of reference as nothing but gibberish. You know there is a method in the madness, that it’s not just madness, even if you can no longer affirm it. I think of how, when I first read about Deconstruction, I thought it was crazy. But, as Mary Midgley said, when we call something “crazy” it just means we don’t understand it. And then I realized there had to be something to it that was not then apparent to me. So I read more, trying to see it. And I finally did see it.

In fact, I now see what first seem like absurdities as opportunities to expand my mind to see (and possibly embrace) new perspectives. I tried to convey this to a student in an Adult School course I later taught about Deconstruction. Though a very learned man, he went in with an attitude of unremitting determination to see and expose Deconstruction as nonsense. What a shame, because, if it wasn’t nonsense, he’d never be able to see it. You have to have an attitude of teachableness, and this man, for all his intelligence, did not. His loss.

Well, I have been on the side of theologians and believers. Though I have long since switched sides, I remember what it was like. And I know that theology is not a subject without subject matter, like Unicornology. Whether you are a believer or an atheist, you may approach theology as a subdivision of the history of thought that deserves at least as much respect as, say, ancient or medieval Philosophy. You most likely don’t find the views of Parmenides and Xeno to be persuasive. You don’t buy the idea that what the senses report to us has no relation to external reality, an infinite expanse indistinguishable by divisions or distinctions, and so on. But were the Eleatics just gushing verbal salad? You’re the fool if you think so.

In the same way, I just cannot look at the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas or the theological systems of Karl Barth and Paul Tillich and X it all out as a bunch of glossolalic gobbledygook. The interplay of competing concepts is exhilarating to explore! All the more if it is initially strange to you!

Theology thinks it is telling us about God. I don’t think there is a God. But theology has much the same attraction as mythology. Both are the cartography of dream worlds. Doesn’t that mean

Richard Dawkins is right after all: it’s just a stupid waste of time? No. Hans Jonas and Rudolf Bultmann explained how “every statement of theology is at the same time a statement of anthropology,” and that is the basis of demythologizing. To demythologize is to decode stories of, and beliefs in, God(s), to reveal the self-understandings of those who produce and who live by the myths. People who inherit or embrace (factually erroneous) myth systems assimilate their dictates and definitions. The systems of belief are projections of the “symbolic universes” (Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann) inside the heads of believers. This is the truth of the formula “As above, so below.” Theology does have subject matter: human beings.

I sent my Soul through the Invisible,

Some letter of that After-life to spell:

And by and by my Soul return’d to me,

And answer’d “I Myself am Heav’n and Hell:”

(Omar Khayyam, Rubaiyat, LXVI)

So says Zarathustra.

July 9, 2016

Schleiermacher’s Forgotten Religion

I don’t know if you will be familiar with the name or the thought of Friedrich Schleiermacher, and if you’re not, that helps prove my point: that this nineteenth-century thinker (one of my greatest heroes) had something to say about religion that clarified it in his day and would clarify it again today if it were more widely known. He was the first to turn the Wheel of Dharma for theology after the Copernican Revolution in epistemology wrought by Kant. Let’s back up.

I don’t know if you will be familiar with the name or the thought of Friedrich Schleiermacher, and if you’re not, that helps prove my point: that this nineteenth-century thinker (one of my greatest heroes) had something to say about religion that clarified it in his day and would clarify it again today if it were more widely known. He was the first to turn the Wheel of Dharma for theology after the Copernican Revolution in epistemology wrought by Kant. Let’s back up.

Immanuel Kant, raised as a Lutheran Pietist in the century before Schleiermacher, demonstrated the impossibility of gaining true knowledge apart from the senses (and the processing of sense data through our built-in array of the Categories of Perception and the Logical Functions of Judgment). There could be no “revealed knowledge” such as theologians had always claimed as the indispensable basis of their doctrines. So what sort of reconstruction of religion might be possible?

Kant himself (like Hegel, I believe) viewed religion, with its miracle stories and ancient myths, to be essentially a symbolic language for morality. If all that stuff helped you learn the lessons of righteousness, great. But if it became an end in itself, if it distracted from morality, or worse yet, as in the devastating wars of religion (still fresh in memory in Kant’s day and new again in our own), if it prompted horribly immoral behaviors, then to hell with it. Religion was like a cartoon version of morality for children, and eventually the time arrives to put away childish things. So Kant decided that “enlightened piety” consisted in morality. Ethics is the essence of religion.

Schleiermacher believed Kant was right about the unavailability of extra-sensory knowledge, the lack of revelation. But he could not agree with Kant’s view of the essence of religion. In his view, Kant had reduced religion to ethics. Just ethics? Sure, morality is indispensable, non-negotiable in importance. But if religion simply boils down to morality, religion is revealed as superfluous. And Schleiermacher thought that completely inadequate. Kant was selling religion short. He had missed the essential thing about religion. And what was that?

Schleiermacher distinguished between three aspects of religion. First was knowledge. This was information about God and his unseen world. It could not be discovered but had to be revealed. But, in the wake of Kant, it turned out there was no such knowledge. The second was practice, specifically ethics. We have seen how Kant subtracted knowledge, emptied that category. Ethics was what was left of religion. Schleiermacher thought Kant had jumped the gun, skipping a third aspect of religion, one which should now be recognized as the essential aspect, in fact, the very essence of religion.

That aspect is piety, which Schleiermacher defined as “a sense and taste for the Infinite” and “the feeling of absolute dependence” upon the great totality of Being, God understood in pretty much a Pantheistic sense (Schleiermacher was much influenced by Spinoza). Schleiermacher explained that all life is contingent upon a web of many factors: your parents happening to fall in love, your food not being poisoned, the roof above you not falling in, etc. And much depends upon you in turn. We are all relatively dependent upon all these factors, but upon the great overarching Whole each of us is absolutely dependent. Everyone is, but not everyone lives in conscious, grateful awareness (“feeling”) of it. Those who do are pious in Schleiermacher’s sense. This awareness is intuitive, a thing more fundamental than cognitive knowledge, i.e., knowledge of discrete things, available to us through the senses.

That aspect is piety, which Schleiermacher defined as “a sense and taste for the Infinite” and “the feeling of absolute dependence” upon the great totality of Being, God understood in pretty much a Pantheistic sense (Schleiermacher was much influenced by Spinoza). Schleiermacher explained that all life is contingent upon a web of many factors: your parents happening to fall in love, your food not being poisoned, the roof above you not falling in, etc. And much depends upon you in turn. We are all relatively dependent upon all these factors, but upon the great overarching Whole each of us is absolutely dependent. Everyone is, but not everyone lives in conscious, grateful awareness (“feeling”) of it. Those who do are pious in Schleiermacher’s sense. This awareness is intuitive, a thing more fundamental than cognitive knowledge, i.e., knowledge of discrete things, available to us through the senses.

Schleiermacher thought we could draw certain inferences from our subjective religious experiences, experiences of “God.” These would count as “knowledge” only in the sense Kant described as the fruit of “practical reason” as opposed to “pure reason.” This was the way Kant arrived at his “practical” argument for God’s existence. Technically, Kant admitted, we cannot know there is a God, but if there is no God to guarantee moral standards, then the whole thing is an illusion. Are we really prepared to accept that? It seems a better bet to proceed on the working hypothesis that there is a Creator who instilled within us the universal moral law and provides an afterlife in which our character development may be brought to completion. This is, roughly speaking, the kind of inference Schleiermacher thought we can derive from religious experience, from “God-consciousness.”

So what’s the difference between Kant and Schleiermacher on this point? For Kant, this experiential argument was just a way to secure a reason for morality, while Schleiermacher saw it as a source from which some sort of religious doctrines might be derived. To use traditional terms, Schleiermacher was willing to be satisfied with faith and not to lay claim to genuine knowledge. Henceforth, for Liberals, theology was no longer a matter of systematizing revealed knowledge (e.g., from scripture), but rather of interpreting religious experience.

But soon after Schleiermacher, Liberal Protestantism took a more purely Kantian direction, defining religion as essentially moral. Albrecht Ritschl, the second founder of Liberal Theology, moved the rudder, and the result was the influential Social Gospel Movement championed by Adolf Harnack, Wilhelm Herrmann, and especially Walter Rauschenbusch. As I understand the current religious climate, Liberal (what used to be called “Mainstream” or “Mainline”) Protestantism as represented by, e.g., the Episcopal Church, the Presbyterians, the United Methodists, the United Church of Christ, and the American Baptists, have moved much, most, or all of the way in the direction of Rauschenbusch, Ritschl, and Kant. Religion has become essentially moral, specifically political. For these denominations, Christianity has become a subset of the Democratic and Green Parties.

As you know, much of Conservative Protestantism has likewise become heavily politicized. I believe that only a tiny fringe repudiated by the vast majority even of fundamentalists wants to impose a theocracy, a Christian counterpart to Islamic Sharia (though I have heard of a small movement of radical Christian theocratic terrorists in Latin America).

For the purposes of the point I am trying to make here, let me distinguish Conservative and Liberal political Protestantisms this way. The Conservatives still (erroneously) believe there is revealed information, infallible commands from a deity. This would seem to make them more potentially dangerous than their Liberal counterparts, but in fact there turns out to be little practical difference since Liberalism is not Libertarianism. Liberalism tends to impose, to regulate, to centrally plan, to patronize, to ostracize and vilify because the end is held to justify the means.

That is the ironic result of “situation ethics,” once a banner of personal freedom. This is the same danger inherent in the larger approach of Teleological ethics, which seeks to escape/avoid the legalism of Kantian Deontological ethics. Results, not rules, make an action right.

But there is an ironic vestige of the otherwise discarded faith that “calls things that are not as though they were.” We expect Liberal Protestantism, in the wake of Harvey Cox’s The Secular City, to be pragmatic, bare-knuckled, disabused of illusion in its pursuit of its social ideals. But there remains a worrisome Hegelian confidence in humans’ ability to discern what God is up to in the unfolding of history and whose side he is on to achieve his aims. That is implicitly theocratic, isn’t it?

And this species of hubris begets another: the faith that ignores likely consequences and that acts against the odds, assuming a diplomatic stance of “believing all things” that one’s nation’s enemies may promise one. That is no more noble, and is considerably more dangerous, than the “faith” by which Jim Bakker pursued various construction projects for which he lacked the funds, believing God would send him the money. I call it “political snake-handling.”

Is there a contemporary version of what Schleiermacher called piety? I should think

Oversoul by visionary artist Alex Grey

Oversoul by visionary artist Alex Greydevotees of contemplative prayer, “practicing the presence of God,” would qualify. They are certainly striving for God-consciousness. But, within the Christian fold, those who take this approach are more likely to be Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox. I am dealing with Protestantism here, the quadrant of Christianity Schleiermacher lived in.

As Unitarianism represents the extreme of the Kantian religion-as-morality trajectory, I should call New Thought (much of which has gone beyond specifically Christian symbolism) the stripped-down version of Schleiermacher-style religion. Of all Christian varieties, New Thought believers focus most clearly on a rather abstract, near-pantheistic God understood as a universal Source of abundance. One strives to remain open and receptive to that fund of endless possibility. This spirituality combines the feeling of absolute dependence and constant God-consciousness.

Nor is this a matter of coincidence, or of reinventing the wheel. It is instead a case of heredity. You see, New Thought owes a significant debt to the New England Transcendentalists and their belief in the Oversoul. And the Transcendentalists’ great source of inspiration was–guess who? Schleiermacher. New Thought seems to me the last redoubt of Schleiermacher’s spirituality. It may be judged a bit debased, often reducing God to a genie to conjure with, but even then it is refreshing in its lack of the hypocritical pretense to “radical discipleship” made by some political Christians.

So says Zarathustra.

June 17, 2016

Hystereotypes

I have often suggested that moral decadence need not be a decrease in morality. I understand it also to refer to a kind of cancerous growth of hyper-morality. I could just call it that, but I use the word “decadence” to differentiate what I mean from the fanatical zealotry in an individual resulting from some psychological quirk, like neurotic hyper-scrupulosity, a moral version of Obsessive Compulsion Disorder. I use the word “decadence” to denote a dangerous cultural senescence or senility in which a civilization loses perspective and begins to embrace fanciful sentimentalism as a moral code. This is especially dangerous when there are serious, real-world issues that demand attention but get neglected because of this ethical fiddling while Rome burns.

A few examples may help. I regard it as decadent, cancerously mutated, morality when people crusade for Animal Rights. (Don’t worry; I do not want to paint vegetarianism with the same brush. That is a separate and eminently defensible point, though I am far from a vegetarian.) There is a foolish confusion here. We humans have the duty to treat animals kindly, not to be cruel to them. But rights belong uniquely to human beings because we are located in a framework of social relations, even if we are pre- or post-rational (babies and the senile and comatose). Animals are not. Is it murder for a lion to kill and eat an antelope? Is the lion violating the rights of the antelope? Can they sue one another over grazing territory or prey-poaching? Do they talk and say, “What’s up, Doc?” But look at the antics of PETA activists. Somewhere along the line they have made a wrong toin in Alba-quoi-que.

It’s even worse when Animal Rights zealots are happily pro-abortion when it comes to human beings. But it’s not exactly inconsistent. Both positions stem from an “Earth First” anti-humanism. Leftists have a neurotic (and dangerously decadent) hatred for their own country. Like a freshman Anthropology student, they espouse value-free cultural relativism—except for America. It is a reverse “American exceptionalism” whereby one hates America as uniquely evil and despicable. One has to, like Noam Chomsky and Saul Alinsky, fabricate libels and myths of “Amerika” to justify this hatred. The sins of Muslim terrorists and Socialist Totalitarians can be forgiven or explained away, but not only are America’s sins excoriated, but her many virtues must be denied.

“Internationalism” and “World Citizenship” are foolishly and even nefariously naïve, imagining that the “collective” opinion of all nations should be our lodestar, when in fact international bodies tend to be tools manipulated by the Anti-Semitic, pro-terrorist, economy-destroying states that dominate them.

Well, the PETA fanatic hates his own species in precisely the same way. Some go so far as to say the earth would be better off without humans, and that we are a plague on the world which should be wiped out, though few go so far as to advocate any action toward that end (like the red-haired scientist in the movie Twelve Monkeys). But the tendency is in that direction, something you need to point out in order to show how wrong-headed some things are. Animal Rights believers are in effect saying that biological Darwinism is just as reprehensible as Social Darwinism and, come to think of it, is actually the same thing.

Hyper-moral decadents live in a world of paper games and official statements. When the disastrous results of that kind of economic and foreign policies become tragically evident, there will be more vacuous idealistic bluster to shift the blame and to make lemons into NutraSweet Lemonade. As Freud said of religion (of which hyper-moral decadence is a certainly a variety), “Progressivism” is an exercise in projecting a wish world onto the real world. This is cultural senile dementia.

Another symptom of hyper-moral decadence is to always make the exception into the rule: the tiny minority rules. Everything must be changed for them. In my view, groups like the ACLU and the Freedom from Religion Foundation are busy pulling on the loopholes of the social order in order to unravel it. Criminals have more rights than their victims. Separation of Church and State is interpreted as restricting any public display of religious symbolism, implying that tolerating it and promoting it are the same thing. Military combatants must be read “their” Miranda Rights.

Because a microscopically tiny group of self-described Transgender kids feel they are in the wrong body (why isn’t that considered Body Dysmorphic Disorder?), adolescent boys and girls must have Unisex showers. I suspect that whole condition is like “Recovered Memory Syndrome.” I wonder how many kids would become gender-confused if school counselors, promoting certain ideologies, did not lead them into thinking so. I’m not a mind-reader or a medical man. I don’t pretend to know.

Because a microscopically tiny group of self-described Transgender kids feel they are in the wrong body (why isn’t that considered Body Dysmorphic Disorder?), adolescent boys and girls must have Unisex showers. I suspect that whole condition is like “Recovered Memory Syndrome.” I wonder how many kids would become gender-confused if school counselors, promoting certain ideologies, did not lead them into thinking so. I’m not a mind-reader or a medical man. I don’t pretend to know.

But I do know this: many will automatically denounce my question as definitive proof that I’m a bigot. Thus, they highlight another aspect of today’s hyper-morality (and in this case, I’d call it “post-morality”): an impatience with rational debate, an attitude I am used to encountering with unreasoning and ax-grinding religionists. Silence the bigot! Shout down any non-“progressive” heresy! “We already know we’re right!” This is the essence of Fascism, but the unbelievable historical amnesia of today’s youth forbids them from learning the lessons of history. If they’ve ever even heard his name, they probably think Santayana lives at the North Pole.

Yet another symptom of today’s cultural dementia is the abandonment of logic as a tool of Dead White Male oppression. Radical Feminists have explicitly argued that, since Aristotle was a male who lived in a patriarchal culture, formal logic can be dismissed as oppressive. How convenient! Using the genetic fallacy as the excuse to topple a system of logic that would have shown you how abysmally stupid the genetic fallacy is! Just the other day I heard Geraldo Rivera brushing off the evidence marshaled against Hillary Clinton because it was presented by a “Right-wing” organization. In other words, because I don’t like their results I can simply assume they fudged the whole thing. Oh, I know that, as my beloved ultra-Leftist history professor Robert Beckwith taught me years ago, “Figures don’t lie, but liars sure figure!” But you have to examine the evidence no matter who marshaled it or why.

Another very chic logical fallacy is that of hasty generalization. The whole Black Lies Matter movement, founded upon debunked falsehoods about police murdering black youths (“Hands up don’t shoot!”), is based on vilifying policemen in general because of the actions of a tiny minority, the logic being that if any black youths are killed by police, this must mean that all cops are at war with black youth simply for being black. In practice, according to this ideology, there can by definition be no black criminals because to accuse one is to accuse all, and that would be racist. Any criticism of any blacks becomes racism. Since it would be racist to suggest that the disproportion of blacks in prison is due to the fact of disproportionate black crime would be racist, too, since we know that is impossible. Crime rates must be equal for all ethnicities. If you suggest that, no, there really is a disproportionate crime rate among blacks but that the reason for it, far from the absurd claim that blacks are genetically predisposed to crime, is the decay of the African-American family because of disastrous government welfare policies, even that will be condemned as racist. Merely pointing out a difficulty in the black community is racist, implying blacks can do no wrong. And the resulting Politically Correct hatred of the police, leading to their refusal to fight crime lest they be pilloried and even arrested for it, shows how absurd things have become. Just as absurd as W.B. Yeats saw that they would.

Another very chic logical fallacy is that of hasty generalization. The whole Black Lies Matter movement, founded upon debunked falsehoods about police murdering black youths (“Hands up don’t shoot!”), is based on vilifying policemen in general because of the actions of a tiny minority, the logic being that if any black youths are killed by police, this must mean that all cops are at war with black youth simply for being black. In practice, according to this ideology, there can by definition be no black criminals because to accuse one is to accuse all, and that would be racist. Any criticism of any blacks becomes racism. Since it would be racist to suggest that the disproportion of blacks in prison is due to the fact of disproportionate black crime would be racist, too, since we know that is impossible. Crime rates must be equal for all ethnicities. If you suggest that, no, there really is a disproportionate crime rate among blacks but that the reason for it, far from the absurd claim that blacks are genetically predisposed to crime, is the decay of the African-American family because of disastrous government welfare policies, even that will be condemned as racist. Merely pointing out a difficulty in the black community is racist, implying blacks can do no wrong. And the resulting Politically Correct hatred of the police, leading to their refusal to fight crime lest they be pilloried and even arrested for it, shows how absurd things have become. Just as absurd as W.B. Yeats saw that they would.

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Ever notice that muggers and burglars on TV are almost always white? This is, obviously, because the depiction of a black criminal would supposedly implicate all blacks as criminals. That in itself would be a ludicrous hasty generalization. But the “solution” is to imply that the reverse is true: criminals must never be depicted as black. Either all of them are, runs the murky logic, or none are.

In the same way, hyper-morality decrees that no one criticize Muslim terrorists because to do so would be to vilify all Muslims. Of course, it would not, but the PC cries of “Islamophobia!” imply (unwittingly and falsely) that all Muslims are terrorists. If to condemn some Muslims is to implicate all Muslims, which we must not do, then to defend all Muslims even if some are terrorists, is to imply all Muslims are exonerated. If we say any are evil, we are saying all are, and since that is obviously false, then all Muslims must be innocent, right?

Our multicultural hyper-sensitivity functions as a Trojan horse for the open society to be subverted by its enemies. Decadent, naïve societies, engaged as they are in a Mad Hatter’s tea party, are inviting and facilitating their own demise. They are spreading their own blood on the water: “Come and get us! We’re ripe!”

“What if they gave a war and nobody came?” You may not show up, but rest assured, they will.

So says Zarathustra.

Patronize me! Please!

Patronize me! Please!

As several of you have advised me to do, Qarol and I have set up a Patreon account. This is a wonderful way of bringing into the 21st century the venerable tradition of patronage: donors supporting artists, philosophers, and scholars, leaving them free to devote more time to their valuable work. In the past, it was only wealthy aristocrats who patronized creators, but Patreon democratizes patronage, inviting interested supporters to contribute whatever they can each month. As Father Guido Sarducci said about those “thirty-five cent sins,” “they mount up!” As you know, I am busy at (too) many things: this blog, my many book projects, the Bible Geek podcast, debating and speaking, and editing fiction anthologies (plus writing my own stories). I have no teaching position because my well-known writings have made me notorious, but I still must share what I know, share it with you.

It would be a very great help to me and my family if we could receive enough support on a regular basis to pay our bills and to allow Carol to leave her (low-paying) job to become my partner and administrative assistant. I would also love to pay my volunteer Bible Geek producers for their heroic efforts on my behalf and yours. Also, Qarol and I would like to share our Heretics Anonymous discussion groups with you, on-line and in person. Your generosity will help us cover our current projects and enable us to expand our efforts. I hope you will consider it! Thanks! https://www.patreon.com/robertmprice

May 30, 2016

It All Boils Down to Stoicism

Marcus Aurelius on his death bed

Marcus Aurelius on his death bedLast night I was watching The Flash and heard Barry Allen say to his foster-father something to the effect of, “You’ve always said that everything happens for a purpose, and I’m beginning to believe it.” I’m not convinced (though, admittedly, I have no connection to the Speed Force, so what do I know?). Let me see if I can demythologize the notion.

Back when I was an Evangelical Christian, I noticed something suspicious about all the big promises about answered prayer and discerning the will of God, plus the teaching that Christians could rest assured that we would lead a charmed life. We could be confidant that God would take care of us. Naturally, it didn’t take very long to realize these promises were false, because equivocal, though we discovered that the hard way. What I mean is that no one had told us about the fine print. Did God always answer prayer? “Well, er, yes, he does, but, heh-heh, sometimes (in fact most of the time!) the answer is a big fat No.” Oh! So that’s the way it works! Bait and switch, no?

But no Christian can dismiss the whole thing as a con game and still qualify as a Christian. His fellow believers, suspecting this, would assure him it wasn’t an option. If you’re a Christian, you have to pray; it’s part of the job description. (And this pops another theological balloon: salvation by grace, since prayer turns out to be a non-negotiable practice of piety.) So what do you do? You keep on praying and you utilize the magic word “faith” as permission to ignore the clanging bell of cognitive dissonance. That is, you undertake to ask God for this or that blessing, for healing, for guidance, etc. You can find some scripture verse that assures you God wants this for you, so you can approach him with confidence! Believe and you shall receive! B…u…t… you don’t. It doesn’t happen. And there’s another cliché designed for that disappointment: “Who has known the mind of the Lord?” How foolish you were to think you, a puny mortal, could know the will of the Creator God! So you reproach yourself in proper Christian humility. But you know what’s going to happen the next time you need something from God. You will quickly forget the human incapacity for reading the mind of God, and you will be back on your pious knees, asking God for some boon. And round and round you go.

There was a clue that should have tipped us off, but we ignored it, were implicitly taught to ignore it. We were told to add to any request the proviso, “if it be Thy will.” Aha! If! In other words, God must already have had a plan for you, and you, like Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane, were willing to acquiesce in it if necessary. Why kick against the goads? But if you thought about it long enough to put two and two together, you saw the irony: surely God must know what he’s doing; he needs you to tell him what to do? If God decided to set aside his plan and answer your prayer instead, it would become like “The Monkey’s Paw,” backfiring in ways you hadn’t foreseen. You might as well stop telling God his business.

This is why Meister Eckhart said a praying Christian should say no more than “Thy will be done.” What is such a prayer designed to effect? You’re no longer asking God to grant a request. So what would you be doing when you prayed such a prayer? You would of course be trying to sensitize yourself to the leading of the Spirit, to reorient yourself to be willing to accept what comes to you from the hand of God. And that, friends, is Stoicism.

Stoicism is an ancient Hellenistic philosophy founded by Xeno of Citium in the third century B.C.E. It was a mutation from Cynicism and upheld the Cynic tenet of “living in accord with Nature by reason.” Stoics were pantheists and believed that the divine Logos permeates all things (kind of like the Force) and controls all things. The only good thing is virtue, and everything that happens to you is, and should be viewed as, a kind of chisel to chip away at your character. You are entitled to enjoy the pleasures of life; just maintain a degree of inner detachment to possessions, hobbies, relationships. That way, you will not feel devastated when you lose these things, as you sooner or later will. Ultimately, these are adiaphora, indifferent things. Take ‘em or leave ‘em. Because ultimately, virtue is the only real good. Tragedy strikes? Hey, go ahead and cry, but buck up! You can choose how you will react to it. You can decide that this unpleasant event will nonetheless be an opportunity for character growth if you accept it as such. “Why kick against the goads?” was a Stoic proverb. How foolish to curse your luck; do you know better than God? He sent it to you, smart guy. Acquiesce; you’ll be glad you did.

Stoicism is an ancient Hellenistic philosophy founded by Xeno of Citium in the third century B.C.E. It was a mutation from Cynicism and upheld the Cynic tenet of “living in accord with Nature by reason.” Stoics were pantheists and believed that the divine Logos permeates all things (kind of like the Force) and controls all things. The only good thing is virtue, and everything that happens to you is, and should be viewed as, a kind of chisel to chip away at your character. You are entitled to enjoy the pleasures of life; just maintain a degree of inner detachment to possessions, hobbies, relationships. That way, you will not feel devastated when you lose these things, as you sooner or later will. Ultimately, these are adiaphora, indifferent things. Take ‘em or leave ‘em. Because ultimately, virtue is the only real good. Tragedy strikes? Hey, go ahead and cry, but buck up! You can choose how you will react to it. You can decide that this unpleasant event will nonetheless be an opportunity for character growth if you accept it as such. “Why kick against the goads?” was a Stoic proverb. How foolish to curse your luck; do you know better than God? He sent it to you, smart guy. Acquiesce; you’ll be glad you did.

And this is what all the Christian talk about God’s providential care boils down to: he approves or sends all events your way to assist in the process of your moral sanctification. Sure, you may not like it in the moment, but you will thank God for it one day, all the sooner if you cooperate. “Good” things are all that will happen to you, that is, things conducive to your sanctification. That makes plenty of sense; it’s just not what they told you at first. But you should have suspected as much if you’d ever read James 1:2-4. “Count it all joy, my brethren, when you meet various trials, for you know that the testing of your faith produces steadfastness. And let steadfastness have its full effect, that you may be perfect and complete, lacking in nothing.”

Today’s idea that “everything happens for a purpose” is more vague, kind of slippery. It does not necessary entail theism. It might fit better with Pantheism, since there seems to be no thought of a personal Controller weaving a tapestry, every thread in the right place, with a definite finished product in mind. No God plotting out everything as a vast novel. It sounds more like the impersonal Dominoes game of Karma. But even this is not demythologized enough for me.

I think that the idea of events being somehow aimed at you (“Special delivery for Mr. Price!”), a form of the doctrine of predestination, is the result of our confusing two very different things. We look back at what has happened to us and we know we can’t change the past. We are stuck with it. But we seem to be inferring that it couldn’t have been avoided beforehand even if we had known what was on the way. This assumption becomes theologized as God’s word (his promise or command) which shall not and cannot return to him void, i.e., having failed in its purpose. I think Stoicism shares this confusion. But, fortunately, the value of Stoicism does not require it.

Forget about second-guessing the past: what if you had done things differently? Why did God make this happen to me? Who cares? The thing is: it has happened, tragic or trivial. Now what are you going to make of it? What are you going to do with it? You’d be wise to cut your losses, to calculate, “What can I learn from this?” “How does this reshuffle the deck?” “What’s the lay of the land now?” “Where do I, where can I, go from here?”

What new opportunities might suddenly have opened up before you? Opportunities for lessons learned, for introspective self-scrutiny, character growth. Why not? The Stoics were right: why waste the opportunity? Why fail to make lemons into lemonade? Is it better just to curse the luck? I don’t see how. This is just common sense. Use the big word “philosophy” if you want. Try to inflate it into theology if you prefer. But I think that is a distraction. It makes you agonize over insoluble pseudo-problems. Or put it this way: theology breeds questions that, as the Buddha said, “tend not unto edification.”

So says Zarathustra.

April 2, 2016

CINEMapocrypha

I am thrilled to greet the arrival of several new movies that celebrate my faith! You may have viewed some of them and may be eagerly anticipating others: Batman Versus Superman, Deadpool, Captain America: Civil War and X-Men: Apocalypse. But there are other flicks which I am planning to avoid like the plague: Killing Jesus, Risen, The Young Messiah, Miracles from Heaven, and God’s Not Dead 2. I am about to do what you’re never supposed to do: comment on these flicks without having seen ‘em. Well, not exactly, because I intend only to make a few

broad remarks based on what the commercials reveal about them. If I am somehow misrepresenting them it is because the commercials are misrepresenting them, and I doubt that. But please feel free to correct, chide, and excoriate me if I get any of them wrong.

broad remarks based on what the commercials reveal about them. If I am somehow misrepresenting them it is because the commercials are misrepresenting them, and I doubt that. But please feel free to correct, chide, and excoriate me if I get any of them wrong.

You probably know what I think of Bill O’Reilly’s book Killing Jesus. I wrote a detailed refutation of it, a book called Killing History: Jesus in the No Spin Zone. I very much doubt the movie version is any better. The book lent itself to easy adaptation because it was already fictional in form, though it loudly claimed to be pure history. It was anything but. By the way, unless I am mistaken, O’Reilly sneeringly dismissed my book without profaning his lips with my name or the book’s title, but I’m pretty sure mine was the only book he could have been referring to.

Risen looks to be a fictional apologetic (is there any other kind?) meant to buttress the faith of fundamentalist viewers in precisely the same way that End-Times movies (Left Butt-cheek, er, I mean, Left Behind, Distant Thunder, etc.) do. The Rapture flicks (one can hardly dignify them with the term “films,” and many are so amateurish that I even hesitate to call them “movies.”) try to reinforce the ever-disappointed expectation of the Second Coming by seeming to depict the eschatological events in a contemporary setting, so the viewer may think, “Yes! This is what’s going to happen! It looks so real, not just some fantasy!” It’s all an ad hoc stop-gap that encourages the drooping faith of the faithful. Well, Risen does the same thing with the resurrection of Jesus. This drama of a Roman soldier being dragged kicking and screaming to faith in the resurrection substitutes for the sketchy, fragmentary, and contradictory Easter accounts of the gospels. A connected narrative with well-delineated characters like us, people who might be convinced that Jesus rose from the dead if there were any real reason to think so. Apologists ask, rhetorically, how the skeptic can explain the origin of the gospels’ “eyewitness reports” if there was no event to give rise to them. But none of the gospel resurrection stories read like anyone’s memories. Instead, they closely resemble myths of Pythagoras, Asclepius, and Apollonius of Tyana. Some are cobbled together from out-of-context and unacknowledged quotations from Daniel. Several quite different Easter tales claim to represent the very first appearance of the risen Jesus. Some include important features (e.g., guards posted at the tomb) that no other gospel has but must have had if they were facts. What the gospels offer us is not convincing, so why not pretend we are looking over the shoulder of someone who might have been present on the hypothetical scene? It is, in fact, all pretend, faith based on fiction.

The Young Messiah might as well have been called “Jesus in Smallville.” This Jesus must have arrived on earth in a rocket launched from heaven before it exploded. In one scene, it has Mary tell the boy Jesus not to display his super powers till he is grown and embarking on his ministry—just like Pa Kent tells young Clark in Man of Steel. Of course, parallels with Superman are unavoidable since the Man of Tomorrow was obviously a Christ analog to begin with (though created by two Jewish lads, Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster). But the point is that Superman becomes a mirror in which we see what Jesus really is: a mythic superhero.

Interestingly, Jesus’ legend, like Superman’s, developed back-to-front (“The first shall be last,” I guess). Superman debuted in 1938 as an adult hero, but he sold so many comics that his publishers decided to create Superboy, “the Adventures of Superman when he was a boy.” Again, enormously popular, so next we read the exploits of (ready?) Superbaby! The same thing happened with Jesus Christ. In Mark, Jesus’ miracle-working ministry and divine Sonship began when he was an adult (Luke estimates Jesus was “about thirty”). But Christian imagination started filling in the gap of “the missing years.” So Luke tells a story of Jesus at 12 years old, confounding the Temple scribes with his prodigious wisdom. Several Apocryphal Infancy Gospels depict Jesus’ boyhood adventures, e.g., striking dead a playground bully. And Jesus becomes Superbaby in Matthew’s and Luke’s Nativity stories, where the Wise Men and the Shepherds visit Jesus’ rocketship, er, manger. The Young Messiah is a cinematic Infancy Gospel.

Miracles from Heaven is based on a medical anomaly that, however, would not even command Fox Mulder’s attention: some kid with neurological problems falls out of a window (or something) and is not only unhurt, but cured. I am not convinced this is other than a pious fraud, but if it really happened—great! But isn’t it jumping the gun to declare it a miracle? Believers constantly turn ignorance into faith (which is why they turn out to be the same thing): “We can’t explain how this happened, so it must have been an invisible deity at work!” That’s like concluding that space aliens must have built the pyramids since we can’t quite figure how the Egyptians could have done it. Similar ancient engineering feats, once baffling, have since been cracked, so it seems worth waiting to see if there is after all some mundane reaction. After all, there’s no reason to attribute epilepsy to demons anymore.

There’s another problem in the premise of this flick. Does it not occur to these people that, if their daughter was really the recipient of a miraculous healing granted by God, it would seem to mean he ignored the prayers of very many other afflicted children? The fact that it didn’t implies that calling it a miracle is really a mystification of saying, “Wow! I can’t believe the luck! Whew!”

And calling it “an act of God” really means the same thing it means in an insurance policy: it was simply an event, dumb luck, not a deed. To say, “God did it” is like saying, “God knows!” In other words, no human being knows. No one did it. But believers, ever eager to claim pretty much anything as evidence for their faith, blur the distinction and wind up thinking the Omnipotent Lord of the Universe broke into the immanent chain of natural causation just for the benefit of one crummy mortal—and not for the rest of the poor saps in the same boat. (You might want to follow up this reasoning in D.Z. Phillips’s book The Concept of Prayer, which shines a Wittgensteinian light on religious language.)