Sean Gabb's Blog, page 7

July 22, 2014

Green Moral Exhibitionism

Political arguments should primarily be based on reason, logic and empirical justification, with ethics taking only a secondary consideration. The reason being: if a policy passes the test with regard to reason, logic and empirical justification, it should pass the ethicality test too. But if ethics is the primary goal, then it can mislead, as reason, logic and empirical justification often take a back seat in the deliberations, which then increases the chances of a mistaken proposal.

Ethics in politics usually takes two distinct forms. There is the ethicality which says something should be done because it is morally the right thing to do, and there is the ethicality which is based on posturing and exhibitionism. The first kind correlates with rationality and economics, in that if a policy passes the rationality and economics test it is probably ethical too, and hence morally right to support it. The second kind is all about being ‘seen’ to be doing the right thing – which doesn’t always mean doing the right thing. Naturally, being seen to be doing the right thing is about winning popularity; actually doing the right thing is about adhering to good arguments and good ethics irrespective of whether they are popular or not.

Examples of being seen to be doing the right thing to win popularity are things like higher taxes for the rich, the minimum wage, and import tariffs. They are policies based on posturing, leading to a moral exhibitionism that purports to care about the right kind of people but actually harms them. Despite the fact that the minimum wage law does harm to the very people it claims to be helping, few politicians serious about their career would ever publicly argue against it. Despite the facts against the minimum wage, publicly supporting it gives the impression that you are a champion of the working class – and that’s always a good vote-winner.

This is what the political arena is like – it has many opportunistic, public relations politicians who care about ‘looking’ like they are doing the right thing rather than actually doing the right thing. If everyone in the UK had an economics degree then almost nobody would support the minimum wage, and any politician that did would look like an incompetent liability. But because most of the electorate is unapprised of economics, the opposite happens, with the majority injudiciously supporting the minimum wage, and considering themselves to be decent in the meantime.

The Green Party is a party that makes many appeals to ethics – much of their ethos is based on ethical appeals regarding the state of the planet, the well-being of future generations, and the need to recycle our waste, preserve our green land and lower our emissions. The driving force behind the green ethos is the moral high ground – their policies are built on what can be summarised as our moral duty to future generations. But the problem is, all of these policies are either counterfactual or they are bad economically (often both), which means that as well as being intellectually fraught, they do not have ethical weight behind them either.

This gives us the situation whereby the Green Party is endorsing bad policies on grounds that they are thought to be ethical – which really means two things: either the Green Party members are unapprised of the real nature of their bad policies and are promoting their cause with genuinely good intentions, or, probably more likely, they know their policies are counterfactual and bad economically, but yet still support them because the majority of the public perception is that its members are morally good and caring. Neither of these is commendable. Being wrong about the merits and demerits of a policy is bad (however good the intentions); placing a premium on moral exhibitionism while knowing the policies lack virtue is even worse.

While I can’t know the individual minds of Green Party members, it seems to me that there’s every indication that their situation is closer to the latter than the former. That is to say, I suspect that they know their policies are counterfactual and bad economically, but yet still support them because they are placing a premium on moral exhibitionism and focusing on one of the few remaining areas of politics that the mainstream parties have yet to claim with any rigour.

I don’t doubt that many Green Party members are fully aware of the counter-arguments to their proposals – but these counter-arguments seem to make no impression on them whatsoever. This would be strange if the party members were diligently looking for the truth; but it is perfectly understandable if they are more worried about surviving as a party and winning votes rather than truth-seeking. Look at it from a Green Party member’s perspective for a moment. Take a typical member; they probably grew up in a time when most of the political ground was commandeered by the mainstream parties. As the old left and right has gravitated towards the centre, what has been left are smidgens of opportunities to stand out in a political landscape dominated by blue, red and yellow.

The one way to make yourself stand out is to champion a cause that is under-represented by the mainstream parties. The hard left Greens have done this with environmental and climate issues, and hard right parties (like UKIP and the BNP) have done this with immigration. Naturally, as popularity increases for these fringe parties, the mainstream parties incur selection pressure to take note and act, incorporating into their manifesto policies on issues like the environment, climate change, immigration, the bureaucratic nature of the EU, and so forth.

So typical Green Party members are rather hamstrung by their political limitations – so they must fight hard to ensure that their perceived strengths and the ways their party is different are ways that will seem like a good alternative to the electorate. Sadly, just as an animal is more likely to become aggressive when cornered, a hamstrung political party is more likely to ignore reason and evidence and become skewed towards the significant, profile-inducing identity that sustains it, even if truth and facts lie elsewhere.

When you look closely at the Green Party, you find that they are quite unlike normal, rationally minded people – their obsession with climate and the environment would be an astonishingly unusual thing if it were not for the fact that green obsession is one of the few remaining political identities on which one could base a party and sustain some electoral territory. Without the need for this green obsession to hold themselves together as an alternative party, what they actually subscribe to is quite bizarrely alien to the ordinary human mental constitution.

The upshot is, the majority of citizens in this country, if they are not shackled by a particular heavy party skew, nor soaked in self-interested opportunism, are not naturally green conscious. They don’t go around believing that the carbon they emit or the extra flight to Spain they take will have any serious catalysing effect on the global environment. Rational people know that green issues are largely down to a simple arms race between increased science and technology enabling us to sort out these problems, and politicians sorting them out with punitive green taxations and social duress.

While we can’t foresee the future with any degree of certainty, we know that all the evidence shows that the past 200 years gives great indication that science, increased prosperity and increased technological capabilities will show these present day green obsessions to have been scarcely worth all the time and effort that has gone into them.

Filed under: Liberty

July 20, 2014

Richard Blake: “Why Byzantium?”

The Joys of Writing Byzantine Historical Fiction

Richard Blake

(Published on ForWinterNights, July 2014)

As the author of six novels set in seventh century Byzantium, I’m often asked: Why choose that period? There’s always been strong interest within the historical fiction community in Classical Greece, and in Rome a century either side of the birth of Christ, and the western Dark Ages. With very few exceptions – Robert Graves’ Count Belisarius, for example, or Cecelia Holland’s Belt of Gold – Byzantium in any period of its long history is a neglected area. Why, then, did I choose it?

The short answer is that I wanted to be different. I won’t say that there are too many novels set in the other periods mentioned above. There is, even so, a very large number of them. If there is always a market for them, standing out from the crowd requires greater ability than I at first thought I had. And so I began Conspiracies of Rome (2008) I ran at once into difficulties I hadn’t considered, and that could have been shuffled past had I decided on a thriller about the plot to kill Julius Caesar. Solving these difficulties put me through a second education as a writer, and may even have shown that I do possess certain abilities. Before elaborating on this point, however, let me give a longer answer to my question: Why choose Byzantium?

Looking at our own family history, we tend to pay more attention to our grandparents than our cousins. Whatever they did, we have a duty to think well of our grandparents. We often forget our cousins. So far as they are rivals, we may come to despise or hate them. So it has been with Western Europe and the Byzantine Empire. The Barbarians who crossed the Rhine and North Sea in the fifth century are our parents. They founded a new civilisation from which ours is, in terms of blood and culture, the development. Their history is our history. The Greeks and Romans are our grandparents. In the strict sense, our parents were interlopers who dispossessed them. But the classical and Christian influence has been so pervasive that we even look at our early history through their eyes. The Jews also we shoehorn into the family tree. For all they still may find it embarrassing, they gave us the Christian Faith. We have no choice but to know about them down to the burning of the Temple in 70AD. The Egyptians have little to do with us. But we study them because their arts impose on our senses, and because they have been safely irrelevant for a very long time.

Byzantium is different. Though part of the family tree, it is outside the direct line of succession. In our civilisation, the average educated person studies the Greeks till they were conquered by the Romans, and the Romans till the last Western Emperor was deposed in 476AD. After that, we switch to the Germanic kingdoms, with increasing emphasis on the particular kingdom that evolved into our own nation. The continuing Empire, ruled from Constantinople, has no place in this scheme. Educated people know it existed. It must be taken into account in histories of the Crusades. But the record of so many dynasties is passed over in a blur. Its cultural and theological concerns have no place in our thought. We may thank it for preserving and handing on virtually the whole body of Classical Greek literature that survives. But its history is not our history. It seems, in itself, to tell us nothing about ourselves.

Indeed, where not overlooked, the Byzantines have been actively disliked. Our ancestors feared the Eastern Empire. They resented its contempt for their barbarism and poverty, and its ruthless meddling in their affairs. They hated it for its heretical and semi-heretical views about the Liturgy or the Nature of Christ. They were pleased enough to rip the Empire apart in 1204, and lifted barely a finger to save it from the Turks in 1453. After a spasm of interest in the seventeenth century, the balance of scholarly opinion in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was to despise it for its conservatism and superstition, and for its alleged falling away from the Classical ideals – and for its ultimate failure to survive. If scholarly opinion since then has become less negative, this has not had any wider cultural effect. As said, there are few novels set in Constantinople after about the year 600. I am not aware of a single British or American film set there.

I discovered Byzantium when I was fourteen. I was already six years into what has been a lifelong obsession with the ancient world. I had devoured everything I could find and understand about the Greeks between Solon and Alexander the Great, and about the Romans till the murder of Domitian. I was teaching myself Latin, and thinking about Greek. Then, one happy afternoon in my local library, I came across Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. I could, and one day will, write an essay about the literary and philosophical debt I owe him. For the moment, it’s enough to say that he led me straight into the so far unexplored history of Late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages. And, though frequently gloomy, what a magnificent history that is. When I studied History at university, I chose every course option that kept me there. Since then, sometimes for years on end, I’ve buried myself in the unfolding story of the Byzantine Empire. Hardly surprising that, when I turned to historical fiction, my first and only choice should be Byzantium.

Of course, I revere Classical Antiquity. But, once your eyes adjust, and you look below the glittering surface, you see that it wasn’t a time any reasonable person would choose to be alive. The Greeks were a collection of ethnocentric tribes who fought and killed each other till they nearly died out. The Roman Empire was held together by a vampire bureaucracy directed more often than in any European state since then by idiots or lunatics. Life was jolly enough for the privileged two or three per cent. But everything they had was got from the enslavement or fiscal exploitation of everyone else.

Now, while the Roman State grew steadily worse until the collapse of its Western half, the Eastern half that remained went into reverse. The more Byzantine the Eastern Roman Empire became, the less awful it was for ordinary people. This is why it lasted another thousand years. The consensus of educated opinion used to be that it survived by accident. Even without looking at the evidence, this doesn’t seem likely. In fact, during the seventh century, the Empire faced three challenges. First, there was the combined assault of the Persians from the east and the Avars and Slavs from the north. Though the Balkans and much of the East were temporarily lost, the Persians were annihilated. Then a few years after the victory celebrations in Jerusalem, Islam burst into the world. Syria and Egypt were overrun at once. North Africa followed. But the Home Provinces – these being roughly the territory of modern Turkey – held firm. The Arabs could sometimes invade, and occasionally devastate. They couldn’t conquer.

One of the few certain lessons that History teaches is that, when it goes on the warpath, you don’t face down Islam by accident. More often than not, you don’t face it down at all. In the 630s, the Arabs took what remained of the Persian Empire in a single campaign. Despite immensely long chains of supply and command, they took Spain within a dozen years. Yet, repeatedly and with their entire force, they beat against the Home Provinces of the Byzantine Empire. Each time, they were thrown back with catastrophic losses. The Byzantines never lost overall control of the sea. Eventually, they hit back, retaking large parts of Syria. More than once, the Caliphs were forced to pay tribute. You don’t manage this by accident.

The Byzantine historians themselves are disappointingly vague about the seventh and eight centuries. Our only evidence for what happened comes from the description of established facts in the tenth century. As early as the seventh century, though, the Byzantine State pulled off the miracle of reforming itself internally while fighting a war of survival on every frontier. Large parts of the bureaucracy were scrapped. Taxes were cut. The silver coinage was stabilised. Above all, the great senatorial estates of the Later Roman Empire were broken up. Land was given to the peasants in return for military service. In the West, the Goths and Franks and Lombards had moved among populations of disarmed tax-slaves. Not surprisingly, no one raised a hand against them. Time and again, the Arabs smashed against a wall of armed freeholders. A few generations after losing Syria and Egypt, the Byzantine Empire was the richest and most powerful state in the known world.

This is an inspiring story – as inspiring as the resistance put up by the Greek city states a thousand years before to Darius and Xerxes. Why write yet another series of novels about the Persian or Punic wars, when a lifetime of research had given me all this as my background? You can ask again: Why Byzantium? My answer is: What else but Byzantium?

And so I’ve written six novels set in the seventh century, mostly within the great cities of the Byzantine Empire. The background in each is the wavering but increasingly successful struggle to break free of the Roman heritage. Conspiracies of Rome (2008) is a kind of prelude. It explains how Aelric, the hero of the entire series – young and beautiful and clever, at least two of which things I’m not – is kicked out of Anglo-Saxon England, and comes to Rome to try his luck. At once, he trips head first into the snake pit of Imperial politics, and doesn’t climb out again until the body count runs into dozens. In Terror of Constantinople (2009), he’s tricked into a mission to Constantinople, where we see the old order of things falling apart in a reign of terror. In Blood of Alexandria (2010), he’s come up in the world, and is in Egypt as the Emperor’s legate, sent there to impose a plan of land reform – which is, you can be sure, entirely his idea. Faced with a useless Viceroy, an obstructive landed interest, and an intrigue featuring the first chamber pot of Jesus Christ and the mummy of Alexander the Great, everything goes tits up, and there’s a climax in an underground complex near to the Great Pyramid.

The next two novels in the series are an apparent digression from the overall scheme. In Sword of Damascus (2011), a very aged Aelric is kidnapped from his place of refuge and retirement in the North of England and carted off to the heart of the Islamic Caliphate. Ghosts of Athens (2012) returns us to the immediate aftermath of Aelric’s less than triumphant efforts in Egypt. I did intend this to be a tightly-constructed thriller set in a horribly broken down Athens. It turned instead into a gothic horror novel – quite a good one, I think; a surprise for the reader, even so.

In Curse of Babylon (2013), I return to Imperial high politics, complete with a Persian a Great King who is described by one of the reviewers as “possibly the most sadistic fictional bad guy I’ve ever encountered.” Because I don’t think I shall write any more in the series, I made Curse of Babylon the most expansive and spectacular of the whole set. It has kidnaps and daring escapes, blood and sex everywhere, acrobatic fights that owe much to Hollywood at its best, and a gigantic battle at the climax.

I suppose there is room for another three or even six. But I’ll not be thinking about that this year, or next year, or perhaps the year after that. My latest novel, The Break (2014) – written under another name – is post-apocalyptic science fiction. This will be followed by a horror novel set in York.

I haven’t bothered with detailed outlines of the six Byzantine novels. What I will say, however, is that I’ve worked very hard not to make any of them into a factual narrative enlivened by a bit of kissing and a few sword fights. I greatly admired Jean Plaidy as a boy, and she taught me as much as I still know about France during the Wars of Religion. But I don’t regard her as a model for writing historical fiction. So far as we can know or reconstruct them, the facts must always be respected. Indeed, I would say that anyone who wants a reliable introduction to the world of seventh century Byzantium could do worse than start with my novels. Even so, these are novels, and they must stand or fall as entertainment. The plots have to keep the reader guessing and turning the pages. The characters have to live and breathe. Their language and actions need to be credible.

Rather than argue that this is what I’ve achieved, let me quote from one of the reviews. According to The Morning Star, I give readers “a near-perfect blend of historical detail and atmosphere with the plot of a conspiracy thriller, vivid characters, high philosophy and vulgar comedy.” Another reviewer has called me “the Ken Russell of historical fiction.” I don’t think this was meant to be a compliment, but I’ll take it as one.

I come now to the difficulty I mentioned in my second paragraph. If you want to write a novel about the plot to kill Caesar, you can leave my readers to supply much of the background. From Shakespeare to Rex Warner and beyond, the reading and the viewing public know roughly what is going on. Everyone likely to buy such a novel knows that Rome had expanded from a city state to an empire, and that its constitution had broken down in the process. Everyone knows that Caesar was ruling as a military dictator, and that this was resented by much of the senatorial aristocracy. Everyone knows who Cicero was, and Mark Antony, and Cleopatra. If you want to write about this, you can largely get on with the plot. You may need to go into a few details about the theoretical legality of Caesar’s power, or the oddities of the Roman electoral system. But much of the job has already been done for you.

You can’t do this with seventh century Byzantium. The reading public can’t be expected to know much at all. You have a continuing Roman Empire after Rome itself has fallen. Paganism is out. Instead, you have a legally established Christian Faith, with ranting clerics whose differing views of the Nature of Christ are turning the Empire into a patchwork of mutually-hostile classes and nationalities. You have a crumbling tax base and an omnipresent threat on the borders with Persia. Later, you have militant Islam. Because readers can’t be expected to know this, you have to tell them.

In Claudius the God, Robert Graves explains the obscure facts of Roman policy in the East with what amounts to a long essay. It’s a good essay. But you can’t do this nowadays. Fashions have changed. Readers are less patient. They want a story to keep moving. You need to integrate your background into the action and dialogue.

I didn’t get this entirely right in Conspiracies of Rome. There’s an authorial explanation at the start of the second section of the novel. This works, but displeased my editor at Hodder & Stoughton. So I worked like a slave on Terror of Constantinople and the other four novels to give my editor exactly what she wanted. In Terror, I allowed myself one explanation of background, but put this into a dialogue between Aelric and a drunken slave who needs to be told about the civil war between Phocas and Heraclius to make sense of a failed murder attempt. In Sword of Damascus, old Aelric is allowed to turn garrulous once or twice when the fourteen year-old English boy he has with him asks questions about the world they’ve entered. On the whole, though, I’m proud of how I eventually got past what seemed an insuperable barrier to writing popular historical fiction set in a fairly unknown period.

It’s easier to show than to describe. But how you do it is a matter of casual asides and revealed assumptions. You pick up what is happening in much the same way as you might from an overheard conversation. To give one example from an alternative history novel I wrote a few years ago, something is described as being “about the same size as a self-charging television battery.” You get the size of the object described from the context. The purpose of the comparison is to tell the reader something more about the technology available. Continue with this throughout the whole course of a novel, and you explain your background without slowing the pace.

But let me give a longer example of how I do this. Here is a passage from Chapter 8 of Curse of Babylon. Aelric is walking through Constantinople in a filthy mood. He’s late for a meeting, and has just had to listen to a couple of hired libellers denouncing him in the street.

Take this as an example from Curse of Babylon:

But all that could wait. Lucas was waiting outside the walls, and with evidence that might let me save still more of the taxpayers’ money on salaries and pensions. I prepared to hurry down into Imperial Square.

‘Might Your Honour be a gambling man?’ someone asked in the wheedling tone of the poor. I paid no attention and looked up at the sky – not a cloud in sight, but the gathering shift to a northern wind would soon justify my blue woollen cloak. ‘Go on, Sir – I can see it’s your lucky day!’ I looked round at someone with the thin and wiry build of the working lower classes. He looked under the brim of my hat and laughed. ‘For you, Sir, I’ll lay special odds,’ he said. ‘You drop any coin you like in that bowl down there.’ I didn’t follow his pointed finger. I’d already seen the disused fountain thirty feet below in Imperial Square. He put his face into a snarling grin. ‘Even a gold coin you can drop, Sir. The ten foot of green slime don’t count for nothing with my boy. He’ll jump right off this wall beside you, and get it out for you.’

I was about to tell him to bugger off and die, when I looked at the naked boy who’d come out from behind a column. I felt a sudden stirring of lust. Like all the City’s lower class, he was a touch undersized and there was a slight lack of harmony in the proportion of his legs to his body. For all this, his tanned skin was rather fetching. Give him a bath and…

Oh dear! He’d no sooner got me thinking of how much to offer, when he swept the hair from his eyes and parted very full lips to show two rows of rotten teeth. The front ones were entirely gone. The others were blackened stumps. Such a shame! Such a waste! So little beauty there was already in this world – and why did so much of that have to be spoiled? I could have thrashed the boy’s owner for not making him clean every day with a chewing stick. I wrinkled my nose and stood up.

His owner hadn’t noticed. ‘Oh, Sir, Sir!’ he cried, getting directly in my way and waving his arms to stop me. ‘Sir, the deal is this. You throw in a coin. If the boy gets it out, you pay me five times your coin. If he can’t find it, I pay you five times. If he breaks his neck or drowns, I pay you ten times.’ He laughed and pointed at the boy again. I didn’t look, but wondered if I might make an exception. Bad teeth are bad teeth – but the rest of him was pushing towards excellent.

But I shook my head. I could fuck anything I wanted later in the day. Until then, duty was calling me again. Trying not to show I was running away, I hurried down the steps.

I think this does the job. It sounds natural. The incident isn’t a diversion from the plot: the boy comes in handy later on. It also tells a lot about the social background – sexual assumptions, the condition of slaves, modes of tooth cleaning, a general air of decadence – and it does so without beating the reader over the head.

This quote being given, I should take the chance to continue discussing it. First the language. In these novels, I don’t face the same problems as I might with a novel set in England or America before about 1900. Because the pretence here is that Aelric is writing his memoirs in Greek, I can give a translation into reasonably idiomatic English – reasonably idiomatic, that is, because a faint Augustanism creates a sense of distance. No one has complained about the faint echoes of Gibbon or Congreve. But there have been complaints about the swearing. One of the American reviewers even says that the books should be R-rated for all the rude words in them. My answer is that this is how people have always spoken. Though heroic and often noble, Aelric is a cynical opportunist. He is always eager to think the worst of people, and to write about them in matching terms.

The reviewer also complained about the extreme and graphic violence. If I never trouble the reader with graphic descriptions of the sexual act – like most other people, I’m useless at writing porn, and there’s tons of it nowadays on the Internet to suit every taste – my novels are drenched in violence. Another American reviewer said that the torture chamber passages in Blood of Alexandria made him feel unwell for several days. My answer again is that this is how it was, and still is. No government has ever lasted without at least the threat of the executioner and the torture chamber. I see no point in hiding the disgusting means by which power is generally got and maintained.

This has turned out to be a somewhat longer advertisement for my novels than I intended, or was asked, to write. So I’ll conclude by saying that, if you like the sound of them, please consider buying my novels. I think they’re rather good. More to the point, so do the reviewers. You should probably begin at the beginning with Conspiracies of Rome, though Sword of Damascus is my own favourite.

All else aside, they make ideal presents for those hard-to-please loved ones.

Filed under: Libertarian Fiction, Liberty

Henry George

by James Tuttle

http://c4ss.org/content/29415

Henry George

The following article was written by Kenneth Gregg and published at CLASSical Liberalism, September 4, 2005.

What is necessary for the use of land is not its private ownership, but the security of improvements. It is not necessary to say to a man, ‘this land is yours,’ in order to induce him to cultivate or improve it. It is only necessary to say to him, ‘whatever your labor, or capital produces on this land shall be yours.’ Give a man security that he may reap, and he will sow; assure him of the possession of the house he wants to build, and he will build it. These are the natural rewards of labor. It is for the sake of the reaping that men sow; it is for the sake of possessing houses that men build. The ownership of land has nothing to do with it. –Henry George

Henry George (9/2/1839-10/29/1897) was born in Philadelphia, the second of ten children of a poor, pious, evangelical Protestant family. His formal education was cut short at 14 and went to sea as a foremast boy on the Hindoo, bound for Melbourne and Calcutta eventually making a complete voyage around the world. Three years later, he was halfway through a second voyage as an able seaman when he left the ship in San Francisco and worked at various occupations (including gold mining) and eventually went to work as a journeyman printer and occasional typesetter before turning to newspaper writing in San Francisco including four years (1871-1875) as editor of his own San Francisco Daily Evening Post. George’s experience in a number of trades, his poverty while supporting a family, and the examples of financial difficulties that came to his attention as wage earner and newspaperman gave impetus to his reformist tendencies. He was curious and attentive to everything around him.

“Little Harry George” (he was small of stature and slight of build, according to his son) was fortunate in San Francisco; he lived and worked in a rapidly developing society. George had the unique opportunity of studying the change of an encampment into a thriving metropolis. He saw a city of tents and mud change into a town of paved streets and decent housing, with tramways and buses. As he saw the beginning of wealth, he noted the appearance of pauperism. He saw a degradation forming with the advent of leisure and affluence, and felt compelled to discover why they arose concurrently. As he would continue to do as he struggled to support his family in San Francisco following the Panic of 1873.

Dabbling in local politics, he shifted loyalties from Lincoln Republicanism to the Democrats, and became a trenchant critic of railroad and mining interests, corrupt politicians, land speculators, and labor contractors. He failed as a Democratic candidate for the state legislature, but landed a patronage job of state inspector of gas meters (which allowed him time to write longer expositions).

As Alanna Hartzok has pointed out, Henry George’s famous epiphany occurred:

One day, while riding horseback in the Oakland hills, merchant seaman and journalist Henry George had a startling epiphany. He realized that speculation and private profiteering in the gifts of nature were the root causes of the unjust distribution of wealth.

His son, Henry George, Jr., said,

…Henry George perceived that land speculation locked up vast territories against labor. Everywhere he perceived an effort to “corner” land; an effort to get it and to hold it, not for use, but for a “rise.” Everywhere he perceived that this caused all who wished to use it to compete with each other for it; and he foresaw that as population grew the keener that competition would become. Those who had a monopoly of the land would practically own those who had to use the land.

…in 1871 [he] sat down and in the course of four months wrote a little book under title of “Our Land and Land Policy [PDF].” In that small volume of forty-eight pages he advocated the destruction of land monopoly by shifting all taxes from labor and the products of labor and concentrating them in one tax on the value of land, regardless of improvements. A thousand copies of this small book were printed, but the author quickly perceived that really to command attention, the work would have to be done more thoroughly.

Over the next several years, George devoted his time to the completion of his major work. In 1879, finding no publisher, he self-published Progress and Poverty (500 copies), and issued the following year in New York and London by Appleton’s after George transported the printing plates to them. The plates were then taken by Appleton’s and the book soon became a sensation, translated into many languages and assured George’s fame, selling over 3 million copies.

At the heart of his critique of Gilded Age capitalism was the conviction that rent and private land-ownership violated the hallowed principles of Jeffersonian democracy and poverty was an affront to the moral values of Judeo-Christian culture. Progress and Poverty was “an inquiry into the cause of industrial depressions and of increase of want with increase of wealth.” In the fact that rent tends to increase not only with increase of population but with all improvements that increase productive power, George finds the cause of the tendency to the increase of land values and decrease of the proportion of the produce of wealth which goes to labor and capital, while in the speculative holding of land thus engendered he traces the tendency to force wages to a minimum and the primary cause of paroxysms of industrial depression.

The remedy for these he declares to be the appropriation of rent by the community, thus making land community owned and giving the user secure possession and leaving to the producer the full advantage of his exertion and investment. This notion of the single tax [PDF] (the term which the successful attorney and free-trade advocate, Thomas G. Shearman (who, along with C.B. Fillebrown, led the more hard-core, pro-free market position within the single tax movement–although later to falter), gave to George’s solution.

George moved his family to New York in 1880 due to the demands as writer and lecturer. In 1881 he published The Irish Land Question, and in 1883-4 he made another trip at the invitation of the Scottish land restoration league, producing on both tours a strong international interest in his ideas. In 1886 he was the candidate for the United Labor Party for mayor of New York, and received 68,110 votes against 90,552 for Abram S. Hewitt (Democrat), and 60,435 for Theodore Roosevelt (Republican). In 1887, George founded the “Standard,” a weekly newspaper (1887-92). He also published Social Problems (1884), and Protection or Free-Trade(1886), a radical examination of the tariff question, An Open Letter to the Pope (1891), a reply to Leo XIII’s encyclical The Condition of Labor; A Perplexed Philosopher (1892), a critique of Herbert Spencer and, finally, his The Science of Political Economy (1897), begun in 1891 but uncompleted at his death, when he was running for Mayor of New York one final time.

George’s legacy has been long and vibrant over the last century, leading to utopian communities, legislators, economists and political activists of all sorts. This is a mixed legacy which one can argue both positive and negative influences. But it cannot be ignored.

Filed under: Economics, Liberty

Is Market Anarchism eclipsing Anarcho-Marxism?

http://attackthesystem.com/2014/07/18/is-market-anarchism-eclipsing-anarcho-marxism/

Is Market Anarchism eclipsing Anarcho-Marxism?

It seems to me that in the last couple of years “free market anarchism” in its various forms has grown to the point where it’s now starting to eclipse or even surpass the “anarcho-Marxists” in terms of size and influence. I base this observation on the number of public events sponsored by both, and the online presence of both. Am I right or wrong in this perception?

I ask not because I think either the anarcho-Marxists or the mainstreams libertarians are genuinely radical or revolutionary movements for the most parts, but because I’m interested in what the prevailing ideological currents are at present. It seems to me the anarcho-Marxists are in the process of self-destructing. It’s getting to where every time they hold a public meeting a fight breaks out between rival PC factions which, ironically, results in the cops often being called. I don’t see a movement like that ever growing or sustaining itself because it’s so ineffective at organizing, maintaining present participants, or recruiting new ones. In my view, the anarcho-Marxists cannot self-destruct soon enough. I say that for functional and strategic reasons rather than ideological ones. They’re a collection of dysfunctional overgrown 12 year olds who are a barrier to the development of a more genuinely radical movement with an anarchist orientation. If “free market anarchism” were to eclipse them, it would simply be a matter of eliminating one obstacle that’s presently in the way.

This is not to say that there are not also many problems within libertarianism/market anarchism. With the growth of libertarianism in recent years, it seems like it’s being pulled towards efforts at co-optation from two main directions. One of these is obviously the corporate-oriented right wing, e.g. Americans for Prosperity, Freedom Works, etc. The other is the PC Left, e.g. C4SS, BHL, Reisenwitz, etc. All that is to be expected. Much of libertarianism is just a microcosm of the wider society. The left wing of libertarianism are Democrats under another name, and the right wing of libertarianism are Republicans under another name. Indeed, at present there seems to be civil war going on among libertarians/market anarchists between the brutalists and the bleeding hearts is a way that’s reflective of the mainstream “culture wars” that represent rivalries among elite and/or middle class factions, and that are irrelevant to actual revolutionary struggle.

Opposition to US imperialism has to be the flagship issue of any serious radical movement in North America, and not arguing about mainstream issues. Anyone who wants to soft pedal that or water it down, much less compromise with the empire, is out of the game before it begins. Whenever I encounter any purported “radical” movement, organization, or individual, the first thing I usually ask is how do they feel about breaking up the USA into smaller political units. If they express opposition, then I know they’re already out of the game. I’ll then ask how they would feel about achieving such through capital “R” Revolutionary action. If they don’t recoil in horror, then I’ll assume maybe they have some potential.

Filed under: Economics, Liberty

DRIP and Tricks of the Political Trade

by Stewart Cowen

http://www.realstreet.co.uk/2014/07/drip-and-tricks-of-the-political-trade

DRIP and Tricks of the Political Trade

The real reason for the drastic Government reshuffle, according to many commentators, is to deflect our attention from the Data Retention and Investigatory Powers (DRIP) Bill which has been rushed through the Commons after the European Court of Justice decided the current measures were ‘illegal’. But according to The Freedom Association:

With the Snoopers’ Charter already having been widely rejected by the public and parliamentarians – the DRIP Bill looks far too similar. While the Home Secretary has claimed this is “merely status quo” legislation – a short glance at it clearly shows that it will grant the security services and police carte blanche access to the emails, telephone calls, texts and internet usage of all UK citizens at home and abroad.

Hat-tip to Leg-iron, who writes,

It’s how stage magic works. While you watch the fancy moves of the left hand, you don’t notice the casual slip of the right hand into a pocket.

It’s like that lesser-used trick made famous by Labour ‘spin doctor’ Jo Moore, “A good day to bury bad news” while thousands had just been killed on 9/11.

Miss Moore’s memo, written at 2.55pm on September 11, when millions of people were transfixed by the terrible television images of the terrorist attack, said: “It is now a very good day to get out anything we want to bury. Councillors expenses?

The first shock is that she’s not a ‘Ms’. The second shock is that such a callous, heartless female was not put on one of those all-women MP shortlists.

But – and this is my point – the U.S. security services were passed intelligence from various governments’ security services about an imminent attack pre-9/11 and ignored them (I wonder why!).

Secondly, if it’s the paedophilia they’re concerned about re. the need for data retention – it seems endemic in Westminster, the judiciary and the upper echelons of the police and is well known about (among themselves and by MI5), but gets covered up.

No. The data retention is for us. If not for now, for the future. Not for terrorists or paedos, but to intercept anti-government talk and catch manmade climate change ‘deniers’, etc. and probably for other reasons, like sifting ‘chatter’ for evidence of tax evasion and benefit fraud.

Re. Jo Moore’s comment in 2001:

But around Westminster, where there was shock and distaste at her cynicism, it was thought that she would have to go.

Sure. You can imagine the ‘shock’ among the heartless and the brain dead in Westminster, can’t you? I can picture them laughing their heads off while they down another subsidised G&T.

The Rev David Smith, whose cousin died in the attack, told the BBC that Miss Moore’s attempt to exploit the tragedy represented the very worst in modern politics.

Now that IS funny. Considering New Labour had recently won their second general election and routinely dumped on us all for years.

But the thought occurs that all this paedomania has been engineered, not only as a sleight of hand to distract us from what the right hand is doing (or the other left hand), but to bring in more surveillance. It could be why, decades later, hundreds of women (and a few blokes) have appeared as if by magic to accuse all manner of people – the living who have mainly managed to defend themselves and been found ‘not guilty’ and the dead Jimmy Savile, where the claims of his alleged abuses are being systematically exposed as fabrications by Anna Raccoon as Savile routinely seems not to have been at the hospitals at the periods in question or he was not left unaccompanied at all when the ‘victims’ were subjected to his hand up their blouse, etc.

So what we need is more surveillance. More intrusion. Scotland’s “Named Person” police state nannyism.

Another famous trick that the best illusionists can do is to make an elephant disappear. That’s why so many people fail to see the elephant in the room.

Or rather, the herd of elephants…

Filed under: Liberty, politicians, Scumbags

Attention Economy

by Nick Land

http://www.xenosystems.net/attention-economy/

Attention Economy

rkhs put up a link to this (on Twitter). I suspect it will irritate almost everyone reading this, but it’s worth pushing past that. Even the irritation has significance. The world it introduces, of Internet-era marketing culture, is of self-evident importance to anyone seeking to understand our times — and what they’re tilting into.

Attention Economics is a thing. Wikipedia is (of course) itself a remarkable node in the new economy of attention, packaging information in a way that adapts it to a continuous current of distraction. Its indispensable specialism is low-concentration research resources. Whatever its failings, it’s already all-but impossible to imagine the world working without it.

On Attention Economics, Wikipedia quotes a precursor essay by Herbert A. Simon (1971): “…in an information-rich world, the wealth of information means a dearth of something else: a scarcity of whatever it is that information consumes. What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it.” Attention is the social reciprocal of information, and arguably merits an equally-intense investigative engagement. Insofar as information has become a dominating socio-historical category, attention has also been (at least implicitly) foregrounded.

Attention Economics is inescapably practical, or micro-pragmatic. Anyone reading this is already dealing with it. The information explosion is an invasion of attention. Those hunting for zones of crisis can easily find them here, cutting to the quick of their own lives.

A few appropriately unstrung notes:

(1) No less than those described by Malthus or Marx, the modern Attention Economy is afflicted by a tendency to over-production crisis. Information (as measured by server workloads) is expanding exponentially, with a doubling time of roughly two years, while aggregate human attention capacity cannot be rising much above the rate of population increase. This is the ‘economic base’ upon which the specifics of ‘information overload’ rest. Relatively speaking, the scarcity of attention is rapidly increasing, driving up its economic value, and thus incentivizing ever-more determined assaults designed to impact or capture it.

(2) Attention is heterogeneous. Sophisticated differentiation (discrimination) is encouraged as the aggregate value of attention rises. As capturing attention (in general) becomes more expensive, it becomes increasingly important to target it selectively.

(3) The limits of Attention Economics are not easily drawn. Is there any kind of work that is not essentially attentive (or affected by problems of distraction)? In particular, any sector of economic activity susceptible to information revolution falls in principle within the scope of an attention-oriented analysis.

(4) Education and politics are inseparable from demands for attention. (Religion, art, pageantry, and circuses carry these back into the depths of historical tradition.)

(5) A psychological orientation to Attention Economics is scarcely less compelling than a sociological one. ‘Attention-seeking’ is a trait so general as to amount almost to a basic impulse, tightly bound to the most fundamental survival goals, with their clamor for nurture, sex, reputation, and power, and then reinforced by formalized micro-economic motivations. The opposite of attention is neglect. Attention-seeking achieves hypertrophic expression in Narcissistic personality disorders, often conceived as the emblematic pathology of advanced modernity. Digital hooks for attention-seeking are evidenced by the reliance upon ‘likes’, ‘favorites’, and ‘shares’ — motivational fuel for the attachment to social media.

(6) The celebrity economy — in academia, journalism, and business no less than in entertainment — is a component of the attention economy. Celebrity is valued for its ability to command attention. Drawing on the structures of evolved human psychology, it lends special prominence to the face.

(7) Mathematical description of the attention economy has been hugely facilitated by the existence of an atomic economic unit — the click. (David Shing, in the video linked at the start, suggests that the age of the ‘click’ is past, or fading. Perhaps.)

Any strategic insights — whether for action or inaction — which do not square themselves with a realistic comprehension of the attention economy and its development cannot be expected to work. NRx, for example, engages a series of practical questions that include the husbanding and effective deployment of its internal attention resources (“what should it focus upon?”), interventions into the wider culture (an attention system), complex relations with media and — to a lesser extent — education, and finally, enveloping the latter, an ‘object’ of antagonism “the Cathedral” which functions as a contemporary State Church — i.e. an attention control apparatus. There is really no choice but to pay attention.

Filed under: Liberty, Science and Engineering

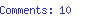

Peace Through Superior Firepower

David Davis

Three and more decades ago, when the Libertarian Alliance kept “The Alternative Bookshop” in Covent Garden, we used to print badges that said useful things to people: rather as if we were Marxists-Turned-Upside-Down – in the words of one of my very perceptive and incisive University chums.

I call this badge to mind [I have kept in the Main Lower Library's Archive Of Objects an example of all the best ones we made] in view of the events of Thursday et-seq. If the Liberal Capitalist West was properly at “Defence-Stations” – and it is not – then it is quite inconceivable that the Russian dictatorship-Junta would even dare to contemplate thinking even privately of destabilizing Ukraine to chew off bits of it – let alone (worse) inveigling traitorous Marxist-sympathisers within Ukraine to do so as its catspaws.

Incidentally we also wouldn’t have more than a light regional but nugatory difficulty with “Islam”: which it is believed is a sort of mysogynistic pre-capitalist desert-survival-guide, but which most of its tacit adherents resignedly accept the Fatwa that it is a “Religion”. For the individual human costs of trying to “leave” it, as prescribed in its Book, don’t bear thinking about.

A major and exact historical parallel, in the same continent, is in front of our noses. In 1938 as you all know, this is when the Third Reich privately egged on the Sudeten-”Germans” under the fascistleftoid Nazi Conrad Henlein, in their efforts to dismember Czechosolvakia. In that instance a major reason was the intended confiscation of Europe’s third largest military organisation, plus the hijacking of Czech and Slovak heavy industry like the Skoda armaments-complex. The Czechoslovak Army alone fielded 43 divisions in that year, not counting its armour-capability.

Eastern Ukraine, as you all know, contains the major part of that country’s industrial and coal mining areas.

I leave you all to draw your own conclusions.

In the meantime, as War Secretary, I’ll ensure that all Anglosphere Nations that wish to “travel with us on the Rad Map For Peace” – the proper one, not the US Democratic Party one – at the very least, are armed to the teeth, without any sort of restriction.

I’ll also be tearing up the Ottawa Treaty and denouncing it on behalf of the UK, for which I will have defence responsibility. It will be my decision, taken in the UK’s best interests. It’s no other nation’s damn business whether we choose to deploy “airfield denial weapons” or not, for example.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ottawa_Treaty

Filed under: Anglosphere, Announcements, army, British Media, Calssical liberal, cheeseburgers, Culture War, de-civilisation, defence, depleted uranium, Groan, history, Law, Liberty, politicians, poor people, Practical Coal Mining, Science and Engineering, Scumbags, War

July 19, 2014

If you can’t laugh at this…

July 18, 2014

The Malaysian Aeroplane Crash

Though short of time, I feel some obligation to comment on this. Let’s take it as read that it was a horrible thing, and move to the questions of who did it and what it may lead to.

Here are the probable candidates for blame:

1. Moslem suicide bomber;

2. The Americans;

3. The Russians;

4. The Ukrainians

5. The rebels.

1. We can probably discount the Moslems. I should imagine it’s rather hard to get a suicide bomb through a West European airport, and blowing up this particular aeroplane had little obvious cause for celebration among the usual suspects.

2. Without better evidence than I’ve seen, we can also discount the Americans. The earliest reports said there were American citizens among the dead. If this had been true, it might have been taken as reason by the more crazed neo-cons to start demanding American air strikes against the pro-Russian rebels in the East of Ukraine. But even if something benefits a particular group, that doesn’t mean the group is behind it. I don’t believe the Americans are up to a false flag operation. The truth would leak out within days. Besides, everyone important in America seems thoroughly disinclined to get into more than a shouting war with the Russians.

3. It’s the same with the Russians. They are better at keeping secrets than the Americans. But I fail to see how shooting down a foreign aeroplane, and blaming the Ukrainians, would bring them any benefit they don’t already have. Mr Putin holds all the cards, and he’s the type of man who only acts when he needs to. To get everything he wants in the Ukraine, all he needs to do is sit and wait for the country to fall apart and for the Americans to walk away.

4. It would benefit the Ukrainian State for the rebels to be denounced across the world as international terrorists. But they are even less capable of a false flag operation than the Americans. They can’t trust each other to keep their mouths shut. They are riddled with Russian spies and with opportunists who will turn pro-Russian the moment it suits their interest. A room full of conspirators can easily come up with a wicked idea. It only needs a couple of men to press the relevant button on a rocket launcher. But there are too many others who need to stand in the chain of command between conception and execution.

5. That leaves the rebels. They keep insisting that they haven’t anything capable of shooting down an aeroplane at 32,000 feet. The problem with this claim is that there is no unified rebel army, and no one knows what the various groups have captured from the Ukrainian armed forces or been given by the Russians. I can easily imagine that a gang of drunks with moustaches let a rocket off, and then spent five minutes dancing about with bottles in their hands. Arguing that the rebel movement as a whole had no interest in doing this is beside the point. No one is in control. Even if not drunk, much of the rebel movement is mad.

Oh, I suppose the Ukrainian military might have done it by accident. The main difference between them and the rebels is that they still wear uniforms from time to time. On the whole, though, I suspect it was the rebels.

So what does all this mean? At first, I imagined a rerun of the first July Crisis – the Americans screaming blue murder, the Russians threatening to shoot any NATO war planes above Eastern Ukraine, etc, etc. But this is unlikely to happen. So I’ll turn to what it should mean.

I believe that the Germans should call a conference in Berlin. The Americans should stop handing round bribes and fraudulent promises in Kiev. The Russians should get their annexation of the Crimea ratified, and some kind of autonomy and assured minority status for their people in the Ukraine. The Ukrainians should get their unpaid gas bills written off. The Americans should get all Russian assistance in saving their face in Iraq and in getting a negotiated end to the civil war in Syria.

I say the Germans, because they have influence in Moscow and are not gross puppets of the Americans. As for the Americans, they should be persuaded as firmly as everyone else can manage to give up their ludicrous ambitions of world domination. They are collectively not up to the job of forming a coherent strategy of domination, in terms both of strategy and of implementation. Their effective power in the world is visibly waning. Unless checked, however, they do have the ability to continue turning the world upside down for years to come. They make trouble where none was before. When there is trouble they haven’t made, they make it worse. The sooner they are knocked off their perch – or are assisted in a reasonably graceful departure from it - the better for us all.

Filed under: Liberty, War

The Ideology of Totalitarian Humanism

http://attackthesystem.com/the-ideology-of-totalitarian-humanism/

The Ideology of Totalitarian Humanism

Many on the alternative Right are inclined to refer to PC as “cultural Marxism.” In some ways, this is an apt metaphor, as the PC ideology bears a resemblance to the reductionist concept of class antagonism that orthodox Marxism advances. If the dualistic class dichotomy of “proletarians and bourgeoisie” is replaced with a newer dichotomy pitting feminist women, minorities, gays, immigrants, the transgendered and others having been or believed to be oppressed against the “hegemony” of “straight, white, Christian, males,” then similarities between PC and Marxism do indeed emerge. However, PC could in some ways be compared with totalitarianism from the other end of the political spectrum. If the duality of “Aryans” believed to be oppressed by and in mortal struggle with “the Jews” is replaced with the aforementioned dichotomy advanced by PC, a reductionism of comparable crudity likewise becomes apparent. Yet it would seem to me that such metaphors as “cultural Marxism” or “liberal Nazism” are not really the best characterizations of PC.

The best label for PC I ever encountered was “totalitarian humanism.” I can’t take credit for this term. I lifted it from an anonymous underground writer some years ago. Read the original essay here. Here’s a particularly enlightened part:

When one looks up the word ‘Humanism’ in an encyclopedia it states that Humanism is an ideology which focuses on the importance of every single human being. That it is an “ideology which emphasizes the value of the individual human being and its ability to develop into a harmonic and culturally aware personality”. This sounds fair enough, right? Indeed it does, but it is my firm belief that the explanation here does not match the humanism of our time.

The so-called Humanists I have met have been putting a strong emphasis on humanity as a gigantic community rather than on the individual. Often one will even find alleged humanists who insist that the views, aspirations and basic happiness of indigenous Europeans is of no importance. Instead, these Humanists say, indigenous Europeans should bow down and forget about their own wants and desires for the greater good of humanity. The greater good of Humanity usually seems to be to take no interest in Europe’s cultural heritage and integrate into a grey, world-wide, uniform “globalization” with the Coca-Cola-culture as loadstar.

Totalitarian humanism is a derivative of the classical Jacobin ideology that loves an abstract and universal “humanity” so much that its proponents don’t care what has to be done to individual human beings or particular human cultures in order to advance their ideals. Perhaps the best summary of the political outlook of totalitarian humanism was provided by the maverick psychiatrist and critic of the “therapeutic state,” Thomas Szasz:

In the nineteenth century, a liberal was a person who championed individual liberty in a context of laissez-faire economics, who defined liberty as the absence of coercion, and who regarded the state as an ever-present threat to personal freedom and responsibility. Today, a liberal is a person who champions social justice in a context of socialist economics, who defines liberty as access to the means for a good life, and who regards the state as a benevolent provider whose duty is to protect people from poverty, racism, sexism, illness, and drugs.

Dr. Szasz wrote this passage nearly twenty years ago. Nowadays, the laundry list of “poverty, racism, sexism, illness, and drugs” might be lengthened to include classism, ageism, homophobia, xenophobia, ableism, looksism, fatphobia, thinism, beautyism, transphobia, producerism, “appearance discrimination,” speciesism, adultcentrism, pedophobia, chronocentrism, and other creative efforts at dictionary expansion. Likewise, the therapeutic component of totalitarian humanism has expanded so as to include the supposed necessity of state action to save us all from fatty foods, salt, smoking, and soda vending machines in public schools. Like all totalitarian ideologies, totalitarian humanism has its contradictions, hypocrisies, and absurdities. For instance, public acts of anal intercourse are regarded as virtuous and courageous manifestations of human liberation and personal fulfillment, while smoking in bars or even in strip clubs is a grave menace to public health. Suggestive music videos and violent video games are symptomatic of an oppressively patriarchal and testosterone-fueled society, while surgically altering one’s “gender identity” is just routine day-to-day business, like getting a tattoo.

As one with something of a taste for the bizarre and eccentric, I might find the PC circus to be little more than a philistine but amusing bit of outrageous entertainment, akin to professional wrestling or the old freak shows of carnivals past, if it weren’t for the fact that these folks are hell-bent on imposing their “ideals” on the rest of us by force of the state. Totalitarian humanism is a war on sovereignty. It is a war on the sovereignty of individuals against arbitrary and coercive authority, the sovereignty of non-state institutions against political authority, the sovereignty of organic communities against a centralized leviathan, the sovereignty of nations against global entities, the sovereignty of history, tradition, and culture against prescriptive and prohibitive ideology. Totalitarian humanism is an effort to reduce all of us to the level of dependent serfs on a plantation ruled by an army of overly zealous concerned mommies and busy-body social workers backed up by the S.W.A.T. team and paramilitary police. Give me beautyism or give me death.

Filed under: Culture War, Liberty