Andrew Sullivan's Blog, page 291

April 25, 2014

Putin vs The Internet

Michael Kelley explains why Russia is looking to assert more control over the Internet, which Putin said on Thursday was “a CIA project” and “is still developing as such”:

Today, Russia is leading the charge for breaking up the Internet as it currently functions by running Web traffic through servers in each respective country. “In two years we may get a completely different Internet,” Russian investigative journalist Andrei Soldatov told BI in January. “It might be a collection of Intranets instead of one Internet. Actually I think it’s very possible.”

Earlier this week, Russia’s parliament passed a law requiring foreign Internet services such as Gmail and Skype to keep their servers in Russia and save all information about their users for at least half a year. This would create a Russian ‘Intranet’ that would be separate from the globally-interconnected Web, much like social media website VKontakte now serves as Russia’s Kremlin-allied Facebook outside of Facebook.

Bershidsky focuses on the Kremlin’s attempt to censor blogs:

A bill passed by the Russian parliament on Tuesday says that any blogger read by at least 3,000 people a day has to register with the government telecom watchdog and follow the same rules as those imposed by Russian law on mass media. These include privacy safeguards, the obligation to check all facts, silent days before elections and loose but threatening injunctions against “abetting terrorism” and “extremism.” This signals to bloggers that they will be closely watched and that Russia’s tough slander and anti-terrorist laws will be applied when the authorities think it appropriate. Bloggers who fail to register as media face fines of up to $900.

There was no international outcry as in the case of the Turkish Twitter ban. Only Dunja Mijatovic, the media freedom representative of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, called on Russian President Vladimir Putin to veto the bill, which he is unlikely to do because it fits in well with his recent oppressive policies. Perhaps Russia has already been written off as a rogue state because of its heavy involvement in the Ukraine crisis, and more curbs on its media freedoms are no longer an issue for the international community. For Russian bloggers, however, the bill – which will come into effect from August assuming that Putin signs it – is a sign that the government is coming for them.

Pavel Durov, the founder of VKontakte, Russia’s answer to Facebook, fled the country earlier this week, saying his company had been taken over by Putin cronies:

Durov explained that after seven years of relative social media freedom in Russia, his refusal to share user data with Russian law enforcement has set him at odds with the Kremlin, which has recently been trying to tighten its grip on the internet, according to The Moscow Times. VK’s former CEO says that despite his multiple refusals of Kremlin requests to censor his site in a similar fashion to how it filters print and TV news, the site — which boasts 143 million registered users globally, 88 million of whom are based in Russia — is now effectively under state control.

Keating takes a closer look at the “Internet sovereignty” movement:

Russia is one of a number of countries pushing the idea of “Internet sovereignty”: the notion that governments—rather than multinational corporations based in the United States or U.S.-founded agencies like the ICANN, which is responsible for the Internet’s global domain name system—should have control over their own internal cyberspaces. …

Internet sovereignty might be a little easier to take seriously as a concept if many of the governments that are most enthusiastic about it weren’t so blatantly interested in policing their citizens’ Internet use. Iran, for instance, has been for years been pushing a “national Internet” project aimed at keeping unwelcome outside influences from reaching its citizens.

Holy Hilarity

Brian Doyle, a practicing Catholic, can’t help smiling at the beliefs of other faiths – “did Joseph Smith really see galaxies in his hat?” – but he suggests a little irreverence can go a long way:

For all that religion has been a bloody enterprise through history, and for all that religious people seem often the most almighty easy people to offend, and for all that there are many people in my faith tradition who think I am an idiot to grin over the most colorful of our traditions, I think we should grin over the more colorful parts of our faith traditions. For one thing, they are often funny—imagine the wine steward’s mixed feelings at Cana after the miracle, for example—and for another, it seems to me that real honest genuine spirituality is marked most clearly by humility and humor. The Dalai Lama, Desmond Tutu, Meher Baba, Flannery O’Connor, Sister Helen Prejean, Pope Francis—all liable to laughter, and not one of them huffy about his or her status and importance. Whereas all the famous slimy murderers of history—Hitler, Pol Pot, Stalin, Mao, bin Laden—what a humorless bunch, prim and grim and obsessed with being feared. Can you imagine any one of them laughing, except over some new form of murder? Think about it—could laughter be the truest sign of holiness?

An Enduring Escape

Hayley Birch tries to figure out why she finds distance running so appealing:

When you’re training for a marathon, you make up reasons for why your body isn’t performing the way you want it to. You didn’t stretch properly after your last run. Your shoes are getting old. It was windy. Muddy. Below zero. You’re still congested after that cold you had two weeks ago. Um… It’s January? The truth is you’re tired. You’re really, really tired. By Friday, a rest day, the lethargy of the week’s training – the hills session, the night at the track, the core strength exercises, the stretching, the 15 km ‘easy’ run at 6.30am – it takes its toll, and you start to doubt whether the 30 km run you have planned for the weekend is a good idea. …

It’s difficult to explain what’s going on in the head of someone who has committed to training five, sometimes six, days a week, to running hundreds of kilometres every month. It’s difficult to explain, even when that person is you. … What I come to accept is that the race itself is just an excuse for all the rest of it. For venturing outside more than once a fortnight, for staying on top [of] my life, for preventing each week from disintegrating into a sea of unanswered emails, unwashed coffee cups and unopened post. For guilt-free time out. For solace.

(Photo by Giorgio Galeotti)

The $84,000 Cure, Ctd

A reader writes:

Hopefully numbers like the price of the hep-C drug will remind us that when it comes to pharmaceuticals, the US is basically subsidizing the rest of the world (and I’m talking to you, countries with nationalized healthcare that negotiate much lower prices than the US). This is just foreign aid, in another guise, whether it goes to Sweden, France or Egypt. When we hear about the “efficiencies” and prices of other healthcare systems, let’s remember that part of the reason is coming right out of our pockets.

Another elaborates:

American citizens bear the costs (taxes, military, rule of law, patent system, education of scientists, etc.) of supporting the environment which makes possible the innovation these drug companies achieve. Then our reward for our collective largesse is that we as consumers get to pay more, by an order of magnitude, for the same drugs than consumers in other countries. How is that fair?

Another adds:

“For patients with a strain that is more difficult to treat, the regiment is 24 weeks. That comes in at $168,000.” Or $1,680 in Egypt – wouldn’t it be more cost effective for insurers to send US patients to “rehab” in Egypt? That price difference is enough that building a residential clinic from scratch, and flying all of the patients first class to Cairo, is likely to be more cost effective than treating them here. There is something economically perverse about that.

April 24, 2014

The Best Of The Dish Today

A reader sent me the above Youtube today. It made me miss Hitch a little more acutely than usual. To see why, go to 48:00 and stay for a few minutes. Watching Hitch stick up for gay love in front of an arch-Catholic audience while debating Bill Donohue all those years ago brought a lump to my throat. He is laughed at and jeered for saying what he says. And so he repeats it. This is the way to counter bigots – by fearless debate and relentless engagement. Hitch had no time at all for nasty bigots. But the last thing he’d ever want is to shut them up.

Leon Wieseltier, meanwhile, has written the same column again! But this time, it does include one pertinent aside:

[Obama] has been trying to escape the Middle East for years and “pivot” to Asia, as if the United States can ever not be almost everywhere, leading and influencing, supporting or opposing, in one fashion or another.

Really? The US must always be “almost everywhere“. Are there no places where the US can express disinterest or indifference or merely concentrate on safeguarding its vital interests? Apparently not. Somehow, the US has to actively stop Russia from meddling – as it has always done – with its near-abroad. How? Ay, that is the question. Wieseltier doesn’t say and never has to say. 1200 words is only ever enough for an indictment, after all.

But this is a live issue. If elected, Hillary Clinton or Marco Rubio or Jeb Bush may well resuscitate the Washington elite’s addiction to saving the world in classic neocon/liberal internationalist fashion. It doesn’t matter that in the last decade, we’ve endured the chaotic consequences of the Libya intervention, the ongoing catastrophe of the Iraq invasion, the impossibility of the Afghan occupation, and the near nightmare of plunging the US into the Syrian vortex (which Wieseltier enthusiastically endorsed). It doesn’t matter that the US is buried in debt, that the public’s opposition to hegemonic meddling is deep and broad, that there is no global ideological struggle to wage, and no genuine external state threats to counter. We just have to be everywhere.

Letting go of empire is never easy. But the prudent, minor unwinding of global hegemony that Obama has managed deserves more respect than this.

Meanwhile, the most popular post of the day was on the humiliation of Sean Hannity in the Cliven Bundy affair. Hannity has since done a triple lutz in distancing himself from his heretofore hero. On his radio show he declared that Bundy’s remarks

are beyond repugnant to me. They are beyond despicable to me. They are beyond ignorant to me,

I just can’t wait to watch the Daily Show tonight, can you?

Runner-up was my post yesterday on Obama’s unsung progress on WMDs in Syria and Iran. Other popular posts were Chad Griffin’s attempt to make amends for the Becker book and Chait’s bon mots about the right and racism. And, er, pseudo-penises.

Our Book Club discussion kicked off – and you can join in by emailing us at bookclub@andrewsullivan.com. You can also leave your unfiltered comments at our Facebook page and @sullydish.

20 27 more Dishheads became subscribers today. You can join them here.

And see you in the morning.

Book Club: Can Christianity Survive Modernity?

[Re-posted from earlier today]

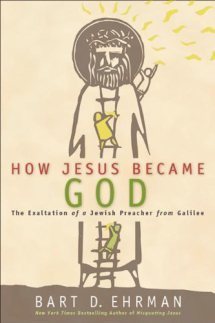

That may seem a rather strange way to kick off discussion of a book about the beliefs of Christians in the decades and first few centuries after the death of Jesus of Nazareth. But it’s the question that lingers in my head after reading Bart Ehrman’s How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of A Jewish Preacher From Galilee.

What Ehrman does in this book – as he did most memorably in Misquoting Jesus – is explain how the texts that we have about the life, death and resurrection of Jesus came to be written. I am not qualified to judge the details of the scholarship – my knowledge of such matters is a tiny fraction of Ehrman’s. I know no Aramaic or Hebrew and very little Ancient Greek. Readers with more expertise may well, with any luck, deal with some of the specific controversies – such as the notion that Jesus probably wasn’t buried at all – as we go along.

But the book’s main claims about the origins and nature of the texts are not in any scholarly doubt. And  they challenge the traditional and reflexive mental universe that most Christians, and all fundamentalists, share. For many Christians in the modern world, there is an unchallenged notion of an inerrant text that contains what we have even come to call the “gospel truth.” It is entirely inspired by God. It has complete authority in Protestant circles and shared authority in Catholicism (along with church teaching and the sensus fidelium). It is the sole authorized account of the extraordinary story that changed the world.

they challenge the traditional and reflexive mental universe that most Christians, and all fundamentalists, share. For many Christians in the modern world, there is an unchallenged notion of an inerrant text that contains what we have even come to call the “gospel truth.” It is entirely inspired by God. It has complete authority in Protestant circles and shared authority in Catholicism (along with church teaching and the sensus fidelium). It is the sole authorized account of the extraordinary story that changed the world.

And yet it isn’t the only account – we have many other extant Gospels that never made the cut. Those Gospels are not as compelling or as coherent or as influential – but they sure do exist. That very fact – established in the 20th Century – explodes any idea of “orthodoxy” among the first Christians. Like any human beings trying to grapple with grief and empowerment and fear and supernatural experiences, they did not understand them fully at first or ever. They disagreed among themselves about them. They had very different perspectives and interactions with Jesus. In the Gospels themselves, Jesus’ disciples are a mess half the time – misunderstanding him, betraying him, frustrating him, and abandoning him at critical moments throughout. Whatever else the Gospels teach us, they sure teach us not to trust Jesus’ followers for either truth or morality. Peter disowned him three times in his hour of greatest need. And most fled after his crucifixion.

And the Gospels offer radically different accounts of what Jesus did, said and meant. There is no single coherent account, for example, of Jesus’ last words in the cross, or of his first appearances after his death – critical moments that you might think would have been resolved as fact early on, but weren’t. If I were to come up with a phrase to describe what has been handed down to us in these texts, it would be a game of Chinese whispers.

Does this rebut Christianity in a decisive way? For many orthodox Christians, wedded to the notion of a single, coherent and inerrant text, it must. But since the scholarship is pretty much indisputable, it seems to me that it is not Christianity that should be abandoned in the wake of these historical revelations, but a false understanding of what the Gospels and Letters actually are. In the end, the sole criterion of a religion is whether it is true. And if you’re misreading its core texts and failing to understand their origins and nuances, you’re not committed to the truth. You’re committed to a theology that has become more important than the truth.

And I’d argue that seeing them in this flawed and human way does not reduce their power. In fact, their very humanness, their messiness, their reflection of competing memories and rival understandings and evolving theologies make the Gospels a riveting tapestry of anecdotage and love and grief. I think that when you treat these texts that way, the figure of Jesus does not become more opaque. He becomes more alive in moving and marvelous detail through the distorted memories of those who loved him and through the stories that the generations that never saw or knew him in the flesh told each other about who he was. Is this human mess guided by the Holy Spirit? That’s obviously a question only Christians can answer.

My own view is that the sheer vibrancy, power, shock, detail and beauty of these stories – and their enduring resonance over the centuries – makes the presence of the Holy Spirit obvious. In fact, if we want to understand how God interacts with human beings, these Gospels show the way. Even through their obvious literal imperfections, a deeper perfection shines. Agnostic and atheist readers will of course disagree. But my point is simply that, for Christians, there is no need to be afraid of the truth about these texts. Because as Christians, there can never any need to fear the truth. In fact, fear of what such scholarship might reveal exposes a defensive crouch and a neurotic denialism that can only lead us away from Jesus rather than toward him.

The truths of this book that only the neurotic or defensive Christian will deny are the following:

Jesus was not the only first-century figure who was deemed to have a virgin birth, martyrdom and resurrection. In fact, these were quite common tropes in the Greek and Roman world at the time. Jesus was far from unique in being seen as part human and part divine in his time. The understanding of his divinity evolved over the years, as his followers argued among themselves and tried to make sense of the incarnational mystery that emerged from his first followers. Jesus himself was clearly an apocalyptic Jewish preacher who believed that the entire world was about to end, to usher in a new kingdom of heaven on earth. The Gospels are a mishmash of competing memories filtered through decades of repetition and translation and manual transcription. The followers of Jesus in his lifetime were primarily illiterate rural Galileans – far removed from the Greek and Roman sophisticates who later tried to make sense of them. All of this comes down to these peasants’ memories and the stories they told each 0ther and then the world.

We see, in other words, through a glass darkly when we look at these texts. But through that darkness, one palpable truth also emerges. It’s a truth that Ehrman once didn’t believe but now does. There is no question that the very first Christians only truly realized the full import of what they had seen and witnessed after it was too late. Their beloved teacher and friend was dead – and executed in a brutal, if conventional, way. But something happened to them after his death. They believed that they had seen him again alive! The revelation of the incarnation of God was a very early Christian conviction – not something that emerged much later, as was once thought. And in that astonishing vision of a Jesus fully alive after death, so much that had mystified his disciples in Jesus’ life and teachings suddenly became clear. This man truly was God. And his teachings and actions in retrospect suddenly took on a deeper and more cosmic and even more urgent meaning.

To kick off the Book Club discussion, I thought it would be helpful to grapple with the core question of these Biblical texts and how they can be integrated (or not) into orthodox Christian belief and practice. Does this book effectively debunk Christianity’s core claims in modernity … or does it point to a new way of understanding and believing them?

Email us your response to this email address: bookclub@andrewsullivan.com. Please keep them to a 500-word maximum, so we can better cope with the curating and editing. We can tackle more specific arguments and themes as the next week goes by.

(Photo: Frederik Mayet as Jesus Christ performs on stage during the Oberammergau passionplay 2010 final dress rehearsal on May 10, 2010 in Oberammergau, Germany. By Johannes Simon/Getty.)

Face Of The Day

A Kashmiri Muslim woman show her indelible ink-marked finger after casting her vote during the sixth phase of Indian parliamentary elections on April 24, 2014 in Vejbeour 45 km (28 miles) south of Srinagar, the summer capital of Indian-administered Kashmir, India. Polling stations opened amid tight security, but very few people turned out to cast their votes in the South Kashmir constituency during the Sixth phase of parliamentary elections (Indian national elections).

Scores of people were left injured in four South Kashmir districts as youth clashed with government forces to enforce a poll boycott call given by the dissent politicians in the region. At least four pro Indian political workers were gunned down by suspected rebels in the region days ahead of the voting in the disputed Himalayan region. A polling officer was killed while five others were critically injured after unidentified gunmen attacked polling staff in South Kashmir’s Shopian district on Thursday evening. The polling staff was returning home when they were fired upon in Nagbal area of the town. The area has been cordoned off. The identity of the slain is being ascertained. By Yawar Nazir/Getty Images.

The Obamacare Debate Is Not About Obamacare, Ctd

I echoed this point a few months ago. Garry Wills nails it:

I fear that the president declared a premature victory for the Affordable Care Act when he said that its initial goals were met, it was time to move on to other matters, and the idea of repealing it is no longer feasible. He made the mistake of thinking that facts matter when a cult is involved. Obamacare is now, for many, haloed with hate, to be fought against with all one’s life. Retaining certitude about its essential evil is a matter of self-respect, honor for one’s allies in the cause, and loathing for one’s opponents. It is a religious commitment.

The irrelevance of evidence in the face of sacred causes explains the dogged denial of global warming, the deep belief that the Obama Administration was responsible for the killing of Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens in Benghazi and that Obama is not a legitimate American. To go back farther, it explains the claims that FDR arranged for the attack on Pearl Harbor and gave much of the world away to Stalin at Yalta (an idea Joe Scarborough is still clinging to). Repealing Obamacare will eventually go the way of repealing the New Deal. But the opposition will never fade entirely away—and it may well be strong enough in this year’s elections to determine the outcome. It is something people are willing to sacrifice for and feel noble about. Creeds are not built up out of facts. They are what make people reject all evidence that guns are more the cause of crime than the cure for it. The best preservative for unreason is to make a religion of it.

Cowardice In Combat

The made-for-tv movie The Execution of Private Slovik – based on the true story of Eddie Slovik, the only American soldier executed for desertion during WWII – aired 40 years ago last month. Chris Walsh considers the film’s success in 1974 and ponders why today “cowardice in the military is a topic too obscure and tender for nonmilitary Americans to contemplate”:

We are willing to have other people’s children put themselves in harm’s way, but we feel both ignorant and guilty about it, and that is enough to keep us from presuming to criticize, much less punish, a deserter. Reflecting on the alleged cowardice of a soldier like Slovik leads to disturbing questions: What would we do in his place? Why haven’t we joined the fight, or more actively supported those who do — or, alternatively, joined in the debate about whether fighting is the right thing? Why did we leave Iraq in such a mess, and is it as big as the mess we left in Vietnam? Bigger? Why did we invade in the first place? Did we really go to Afghanistan to get Bin Laden (who of course was killed independently of the war)? Why are we leaving there now? Is what has been called the cult of national security itself a symptom of cowardice? The prospect of executing a deserter is even more disturbing. Would you have hit Slovik’s heart?

A Supreme Impediment

The chances of an Iranian deal are looking up, but Daniel Berman rightly worries about domestic politics over there:

Khamenei is 78 years old, and rumored to be ailing. His successor will be chosen by the Assembly of Experts, a group of clerics elected by the public (from an approved list of candidates) who are tasked with selecting the Supreme Leader and supervising his activities (at least in theory). Last elected in 2006, the Assembly serves for a term of eight years, though the term of the present Assembly has been extended to 2016. That means that the next Assembly will serve until 2025, and is almost certain to select Khamenei’s successor. …

Rouhani is therefore to focus much of his energy over the next two years on the goal of maneuvering for those 2016 contests, and as a consequence his objectives in talks with the United States are likely to be very different from Obama’s. Obama seems to want a genuine normalization of relations, whereas Rouhani is merely seeking a reduction in tensions. Obama is willing to sacrifice domestic political capital to improve relations with Iran; Rouhani by contrast, is attempting to use American concessions as a currency to purchase political capital at home. He is willing to sell symbolic concessions such as a less anti-American line in the state media, which now focuses largely on a Saudi-Israeli “axis,” or photo-ops at the UN, in exchange for U.S. concessions on real issues like sanctions and the nuclear program. However, the key point is that Rouhani is looking to accumulate political capital rather than expend it, and it can only be accumulated by winning concessions from the United States, not by working with it.

The domestic politics in both Iran and the US is what can still make this deal unravel – and war therefore more likely.

Andrew Sullivan's Blog

- Andrew Sullivan's profile

- 153 followers