Andrew Sullivan's Blog, page 288

April 28, 2014

A Soap Company’s Dirty Tricks

Virginia Postrel slams Dove’s recent viral ad, seen above:

Dove’s “Real Beauty” ads have always treated women as dumb, or at the very least immature. They’ve always preached that adult women are typically obsessed with their looks and that recognizing flaws is the same as feeling hideous and miserable. They’ve always projected adolescent attitudes onto grownups while styling Dove as an enlightened savior.

This time, however, the brand made its condescension a little too clear, sparking a well-deserved firestorm of criticism.

“Shame upon you, Dove, for making these women seem dumb,” declared a New York Magazine piece, the headline of which called the video “garbage.” AdWeek asked, “Is Dove empowering women or calling them gullible?” Dove’s whole campaign, concluded the feminist website Jezebel, is “about teaching women that Dove knows better. Dove is smarter,” than its foolish customers. Jezebel tagged the post with the category “Badvertising.”

Danielle Kurtzleben explains how Dove ads became love-your-body campaigns:

In 2000, Dove parent company Unilever crafted a strategy plan called the “Path to Growth,” in which it cut down 1,600 brands to 400, according to a 2007 Harvard Business School case study from HBS Professor John Deighton. A few of the lucky surviving labels were selected to be what are called “Masterbrands” — brands that were “mandated to serve as umbrella identities over a range of product forms,” as Deighton puts it. Dove was one of them.

In other words, Dove would now make the jump from being just a soap to being a brand that covered all sorts of products: shampoo, conditioner, deodorant, and so on. And that jump into lotion and hair mousse is why Dove became synonymous with “real” women posing in their undies.

Update from a reader:

You should post a link to this hilarious new Dove parody ad (it’s new, not one of the ones from last year). Very good satire:

The Importance Of Damage Control

It may be the key to immortality, according to James Vaupel, director of the Laboratory of Survival and Longevity at the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research:

“Every day we suffer damage and don’t perfectly repair it,” explains Vaupel, “and this accumulation of unrepaired damage is what causes age-related disease.” It’s not a trait that is shared by all living organisms. Hydra for example – a group of simple, jellyfish-like creatures – are able to repair almost all the damage they suffer, and readily slough cells that are too injured to heal. In humans, it’s damaged cells like these that can give rise to cancerous tumors.

“Hydras allocate resources primarily toward repair, rather than reproduction,” says Vaupel. “Humans, by contrast, primarily direct resources toward reproduction, it’s a different survival strategy at a species level.” Humans may live fast and die young, but our prodigious fertility allows us to overcome these high mortality rates. Now that infant mortality is so low, there’s really no need to channel so many resources into reproduction, says Vaupel. “The trick is to up-regulate repair instead of diverting that energy into getting fat. In theory that should be possible, though nobody has any idea about how to do it.” If the steady accretion of damage to our cells can be arrested – so-called negligible senescence – then perhaps we won’t have an upper age limit. If that’s the case, there isn’t any reason why we should have to die at all.

Previous Dish on longevity research here.

(Photo of Hydra vulgaris by Przemysław Malkowski)

Venezuela’s Commie Core

Juan Nagel examines how the Venezuelan government is meddling in the country’s school system in an apparent effort to push socialist propaganda on its children:

Venezuela has an extensive network of public schools, one that existed long before Hugo Chávez came to power. Due to the spotty quality of the education these schools impart, there is also a large web of private schools that has always operated with relative freedom, although under close government supervision. This peaceful coexistence, however, was shattered in 2012 when the government passed “Resolución 058.” The text, which emanated from the Ministry of Education, changed the entire governance structure for both public and private schools. Recent steps to fully implement it have set off alarm bells in the entire opposition education community.

In order to “promote participatory democracy,” the resolution states that all decisions in every school — public or private — must involve parents, teachers, students, workers, and even “the community,” represented by “communal councils.” Including communal councils in these decisions is done in order to “construct a new model of socialist society.” Many in the opposition view this as the last straw in a long line of attacks against the rights of parents to freely educate their children. While the government has talked of making schools epicenters of socialist indoctrination for years, they had not acted upon those wishes until now. Many thought the decree would never be implemented, but lately the government has started making good on its ill-favored promise, so the issue has come up again… with a vengeance.

An Overblown Problem

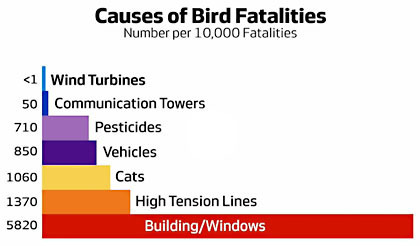

Kevin Drum is fed up with misinformation about the danger wind turbines pose to birds:

Wind turbines can be noisy and they periodically kill some birds. We should be careful with them. But the damage they do sure strikes me as routinely overblown. It’s bad enough that we have to fight conservatives on this stuff, all of whom seem to believe that America is doomed to decay unless every toaster in the country is powered with virile, manly fossil fuels. But when environmentalists join the cause with trumped-up wildlife fears, it just makes things worse. Enough.

Tom Randall looks into the stats:

The estimates above are used in promotional videos by Vestas Wind Systems, the world’s biggest turbine maker. However, they originally came from a study by the U.S. Forest Service and are similar to numbers used by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Wildlife Society – earnest defenders of birds and bats. No matter whose estimates you use, deaths by turbine don’t compare to cats, cars, power lines or buildings. It’s almost as if there’s been a concerted effort to make people think wind turbines are more menacing than they actually are.

This perception can delay project permitting. An expansion of the world’s largest offshore wind farm was recently scrapped after the U.K. would have required a three-year bird study. Only recently did the U.S. Interior Department loosen restrictions on wind farms, which according to the Wildlife Society kill dozens of federally protected eagles and about 573,000 birds a year. Other manmade killers take out almost a billion.

What’s Fair Is Fair

But who can say what “fair” means? Nicholas Hune-Brown wonders whether cross-cultural standards of fairness exist, drawing on a study of the Pahari Korwa tribe in central India. Anthropologists asked participants to play the “ultimatum game,” in which two players decide how to split up a given sum. The first player proposes a division, and if the second player disagrees, neither player receives anything:

The researchers visited 21 villages, inviting 340 people to play the game (each person could only play once, as either “proposer” or “responder”). The [sum to be divided], in this case, was 100 rupees, equivalent to about two days of work in the region. If fairness is a cultural norm, you’d expect there to be some consistency across a culture; bargainers playing the ultimatum game should act similarly. With the Pahari Korwa, researchers found that responders across each of the villages indeed reacted the same way: they took the money. Whether the offer was five percent of the pot or 80, in all but five cases the responders took what was available. The proposers, however, varied substantially in their suggested splits. The modal offer across all villages was 50 percent, but there was no consistency. Some villages offered around 30 percent, while others, bafflingly, went as high as 70 percent.

The Pahari Korwa were all over the map. There was no single idea of fairness, no cultural conformity. The researchers argue that this could be because fairness isn’t a cultural norm, or at least not one that is shared across an entire ethno-linguistic group. They write that “the variation in cooperative and bargaining behaviour across human populations that is currently ascribed to culturally transmitted fairness norms may, in fact, be driven by individuals’ sensitivity to local environmental conditions.” That is, maybe a sense of fairness isn’t something that exists in something as large as a “culture.” Maybe it’s only shared between neighbours—the people you’ve chosen to live next to, presumably because you’re able to cooperate and share the same sense of what is fair.

“The Power Of Weakness”

Morgan Meis considers Hitler’s aesthetic sensibilities in a review of the Neue Galerie’s “Degenerate Art” exhibition. He singles out a work by Emil Nolde, whose work was condemned by the Nazis even though the artist joined the party in the early 1920s:

Nolde’s art simply did not look right to Hitler and Goebbels and Ziegler. Looking at

his famous woodcut, “The Prophet” (1912), one can see why. It is a stark woodcut, with thick and harsh lines. The prophet’s face droops downward, sallow and a step away from complete defeat. Nolde’s prophet does not bear a message of triumph. He has a sadder tale to tell. This isn’t to say that the prophet lacks strength. He has learned something, Nolde’s prophet. He knows that life is made richer by the trials of pain and suffering. Nolde’s prophet wants everyone to know that our greatest strength can be found, paradoxically, in our weakness. This was a spiritual insight utterly intolerable to Hitler. Hitler had emerged from his own pain and suffering with a different idea: Strength comes from strength, power from power.

Nolde was compelled to make art that expressed the power of weakness even while he professed Nazi doctrine that strength comes from strength. This proves how thin and sometimes imperceptible is the line between these two thoughts. The latter is so much more compelling. It is an idea we tell ourselves every day; that we must ever be strong.

(Image of The Prophet by Emil Nolde, 1912, via Wikipedia)

Setting Softer Standards

Eric Hoover reports on college admissions programs that increasingly eschew standardized test scores in favor of evaluating potential students for “soft skills” like curiosity and optimism:

DePaul is implementing their own tests for non-cognitive skills, with a series of essay questions. For the entering class of 2012, about 10 percent of applicants (or about 5 percent of the freshman class) chose not to send ACT or SAT scores. Instead they completed four short-answer questions, designed to measure their leadership skills and their ability to meet long-term goals. Systematically scoring the responses to those questions, DePaul reported that the freshman-to-sophomore retention rate was almost identical for those who submitted standardized test scores (85 percent) and those who did not (84 percent). [DePaul University’s associate vice president for enrollment management Jon] Boeckenstedt is encouraged by these preliminary results.

However, even as schools make progress in quantifying non-cognitive skills, there is also worry about the assessments they are building. Non-cognitive skills are often measured through self-ratings, which means respondents can fake their answers. This is partly why Brandeis University did not add non-cognitive assessments when it dropped its testing requirements recently. “Once you introduce these measurements into your system, you introduce the ability to game those measurements, especially if students know they are being tested for an opportunity,” says Andrew Flagel, senior vice president for students and enrollment at Brandeis. “With most of these questions, it’s awfully hard to frame them in a way where one couldn’t intuit the best answer.”

April 27, 2014

The Best Of The Dish This Weekend

A brief round-up: two new batches of Book Club emails – one lacerating me for clinging to faith, the other providing some back-up. I’ll do my best to respond tomorrow.

Four more: the voguers of Baltimore; two poems by Nina Cassian; C.S. Lewis on the need for old books; and a peak into the actual – love-drenched – life of Michael Oakeshott.

The most popular post of the weekend remained my takedown of the Becker book on the marriage equality movement.

See you in the morning.

(Photo: Re-enactors take part in a display as part of the ‘St George’s Festival’ at the English Heritage’s Wrest Park estate on April 26, 2014 near Bedford, England. ‘St George’s Festival’ at Wrest Park takes place on April 26 and 27, 2014 and features reenactments of various eras of British history from medieval times to the First World War. By Oli Scarff/Getty Images.)

The Pernicious Poison Of Palin

She represents an absurdist nadir in the history of presidential campaigns. But in case you ever doubted just how callous and toxic she can be, I give you the following:

“Well, if I were in charge …. They would know that waterboarding is how we baptize terrorists.”

A Christian who can equate the sacrament of baptism with a barbaric form of torture is not a Christian, whatever self-righteous blather she emits. And a former vice-presidential candidate who talks of “baptizing” Muslim terror suspects through waterboarding is handing al Qaeda a propaganda coup on a platter. She disgusts me. And what disgusts me even more is the rank cowardice of so many sane Republicans who for far too long have failed to take her on.

Why We Can’t Leave Beauty Behind

In an interview, the writer and editor Gregory Wolfe, who helms the journal Image, explains why so much of his work grapples with beauty rather than ideology:

One of the key dimensions of beauty that theologians and philosophers consistently refer to is beauty’s disinterestedness. The very nature of beauty is that it escapes our attempts to turn it into an instrument for the benefit of the group or tribe to which we belong. There’s something both gratuitous, elusive, and yet attractive about beauty. That paradox is essential as a kind of leavening or balancing force in a world where there are always people with axes to grind, cases to make, and interests to promote. The theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar says that in a fallen world questions of truth and goodness will always be heavily debated, and people will always invest these debates with their interestedness, their parties, and their political leanings. He argues that beauty has the capacity to sail right under the radar of those interested parties. So, while truth and goodness are also “transcendentals,” beauty has the possibility of coming at us with a purer ray from the beatific vision itself.

(Image of Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, 1483, depicting the classical personification of beauty, via Wikimedia Commons)

Andrew Sullivan's Blog

- Andrew Sullivan's profile

- 153 followers