Andrew Sullivan's Blog, page 287

April 29, 2014

Mental Health Break

A Japanese music video with evolving stick figures:

Shugo Tokumaru / Poker (Official Music Video) from MIRAI_MIZUE on Vimeo.

The Smearing Of Ryan As A Racist, Ctd

In a lengthy profile of Paul Ryan, McKay Coppins suggests that last month’s “dog-whistle” controversy has genuinely shaken the congressman’s confidence:

He is like a singer who has suddenly discovered his lack of relative pitch while on stage, and now worries that every note he’s belting out is off-key. As we talk, he chooses his words with extreme care, and is prone to halting self-censorship. At one point, as he tells me about his efforts during the presidential race to get the Romney campaign to spend more time in urban areas, he says, “I wanted to do these inner-city tours – ” then he stops abruptly and corrects himself. “I guess we’re not supposed to use that.” …

It would be easy to use stuff like this to ridicule him for his tone-deafness, his white-guyness, his sheltered cluelessness. But Ryan, by his own admission, is receiving his sensitivity training in real time. He has charged headfirst into the war on poverty without a helmet; zealously and clumsily fighting for a segment of the American public that his party hasn’t reached since the Depression-era shantytowns that lined the Hudson River were named after Herbert Hoover. It is frequently awkward and occasionally embarrassing, but it is also better than staying on the sidelines.

Yglesias snarks that the article has everything “except for even a teeny tiny shred of insight into how Paul Ryan’s policy ideas will impact poor people”:

For example, what does Ryan’s budget mean for the poor? Well it turns out that the majority of his budget cuts come from programs that benefit poor people.

He wants to reduce spending on poor people’s Medicaid benefits. And on their nutrition assistance. And on their college tuition assistance. And on their access to subsidized private health insurance. Ryan does cut some programs that aren’t aimed at helping low-income Americans, but mostly he cuts programs for the poor.

At the same time as it cuts spending on the poor, Ryan’s budget also has tax provisions. Specifically he calls for $5.7 trillion worth of tax rate cuts. That money, he says, will be made up through unspecified reductions to tax credits and tax deductions. When the Tax Policy Center analyzed the distributive implications of this kind of plan, they found that it increases the after-tax income of the rich while raising taxes on the working- and middle-class.

Meanwhile, Chait sees Ryan “altering the basis for his public appeal in a significant way”:

Ryan burst upon the national scene by presenting himself as a wonk’s wonk, the concerned, helpful man with the calculator here to help America avoid its fiscal crisis. Ryan the Wonk did not always know what he was talking about, but the important thing is that he looked like he did.

The newer iteration wants to make his case in non-pecuniary terms. Point out that his budget enacts a massive upward redistribution of income, and he will tell you about his soul. It is very much the same method used by George W. Bush to ward off criticisms of his fiscal priorities. (When Al Gore stated during a 2000 presidential debate that Bush had taken funding from children’s health insurance in order to cut taxes for oil companies, Bush replied, “If he’s trying to allege that I’m a hard-hearted person and I don’t care about children, he’s absolutely wrong.”) It’s a tactic that meets both Ryan’s needs and the needs of journalists possessed of great confidence in their ability to judge the sincerity of political theater.

An Ocean Of Foam

Andy Cush captions:

36 ventilators, 4.7m3 packing chips, a new installation from the Swiss artist Zimoun, does what it says on the tin. The artist filled a space inside Switzerland’s Museo d’Arte di Lugano with lots and lots of polystyrene packing peanuts, and uses 36 fans to whip them into a stormy frenzy.

bitforms gallery elaborates on Zimoun’s mission:

Using simple and functional components, Zimoun builds architecturally-minded platforms of sound. Exploring mechanical rhythm and flow in prepared systems, his installations incorporate commonplace industrial objects. In an obsessive display of simple and functional materials, these works articulate a tension between the orderly patterns of Modernism and the chaotic forces of life. Carrying an emotional depth, the acoustic hum of natural phenomena in Zimoun’s minimalist constructions effortlessly reverberates.

Why Net Neutrality Matters

Alexis Madrigal and Adrienne Lafrance explain why advocates of net neutrality approach the issue with such great passion:

This idea of net neutrality—this cherished idea, even, among Internet entrepreneurs and activists—has a long history, roughly as long as the commercial world wide web. It is, Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig has argued, what makes the Internet special. He used to call the principle e2e, for end to end: “e2e. Not b2b, or b2c, or c2b, or b2g, or g2b, but e2e. End to end. The core of the Internet, the core value that defined its power, the core truth that made innovation around it possible, is this e2e,” Lessig said in a 1999 talk. “The fact – a fact – that the network could not discriminate in the way that AT&T could.”

Comcast couldn’t privilege its own content over Netflix’s or PBS’ or Disney’s or your blog’s. He explained: “The network was stupid; it processed packets blindly,” he said. “It could no more decide what packets were ‘competitors’ than the post office can determine which letters criticize it.”

This was not just a nice thing, it was the very nature of the Internet. Without it, the Internet will become, as Tim Wu put it, “just like everything else in American society: unequal in a way that deeply threatens our long-term prosperity.”

But Jimmy Wales, the founder of Wikipedia, tells Jemima Khan that he’s not that worried about it:

I differ from many of my colleagues, in that I don’t think net neutrality is super-important. The fear is that companies which control the “last mile” to the consumer will leverage that choke point to stifle innovation (unless they get paid extra for it happening). And that’s not an entirely crazy thing to fear, particularly because much last-mile infrastructure remains under inappropriate, government-granted monopoly privileges—or derived from those privileges in the first place years ago.

But if we are worried about a handful of companies getting control of a choke point and using it to squeeze out competitors and make massive profits, we don’t need to look at the layer of network infrastructure and network neutrality. We just need to look at the Apple App Store (and similar), where everything that runs on your iPhone or iPad has to be approved by Apple, with them taking a huge cut of the revenue at every step, with no real competition in sight. Consumers should be very worried about that.

Can you imagine the outcry if 20 years ago Microsoft had decreed that no third-party software could run on Windows without being approved by them, and bought through their proprietary stores? Yet today we accept this model on mobile devices (and soon, I fear, on our computers) without blinking.

Barbara van Schewick discusses some of the dangers she sees in imposing access fees for Internet content:

Why should we care if start-ups or other innovators without significant outside funding cannot pay these fees and therefore lose the ability to innovate? Throughout the history of the Internet, innovators with little or no outside funding have developed many important innovations (including E-Bay, Facebook, Yahoo, Google, Apache Web Server, the World Wide Web, Flickr and Blogger), and there is no reason to believe this would change in the future. Thus, removing (or at least impeding) the ability of this important subgroup of innovators to develop new applications will significantly reduce the overall amount and quality of application innovation.

Finally, access fees may impose serious collateral damage on values like free speech or a more participatory culture by making it more difficult for individuals or non-profits to be heard or to find an audience for their creative works.

And Timothy B. Lee blames Congress for tying the FCC’s hands on net neutrality, noting that the relevant law predates the concept:

The 1996 Telecommunications Act prohibits the FCC from imposing common carrier regulations on “information services,” which (according to the FCC) includes broadband internet access. The law says that information services can’t be subject to common carrier regulations. In its January ruling, the court said that the FCC’s 2010 net neutrality rules constituted common carrier regulation and was therefore illegal. But the court signaled that it would accept a revised set of rules that only prohibited discrimination if it was “commercially unreasonable.”

Is that the result Congress intended? No one really knows. The term “network neutrality” hadn’t been coined yet in 1996. Cable modems and fiber optic services like FiOS were still in the future. Unsurprisingly, Congress wasn’t clear about how to handle concepts and technologies that didn’t exist yet, so the courts have had to make up the rules as they went along.

April 28, 2014

The Best Of The Dish Today

There’s Sullybait and then there’s Sarah Palin equating torture with Christianity. Not since Easter fell on 4/20 …

We introduced the remarkable evangelical Harvard drop-out, Matthew Vines, whose relentless logic and spiritual generosity comes through on every page of his depth-charge of a book, God and the Gay Christian: The Biblical Case In Support Of Same-Sex Relationships. If you read it, you’ll understand why the fundamentalists are in a bit of a panic.

Kerry told the tragic truth about Greater Israel. A reader defended the drug companies. Plus: Cicada Killer Wasps.

My Politics and Prose talk with Michael Lewis about his bestseller Flash Boys is now online. We had a lot of fun:

You can buy Michael’s book here.

The most popular posts of the day were Sarah Palin: Anti-Christian; and The Pernicious Poison Of Palin.

See you in the morning.

(Photo: A pro-government supporter attends a rally on April 28, 2014 in Donetsk, Ukraine. Several people were injured when pro-Russian activists attacked the supporters when they began a march following the rally. By Scott Olson/Getty Images.)

Book Club: The Indispensable Jesus?

I’m sorry for not jumping into the debate more this weekend, but the pollen bukakke in DC right now has reduced my lung capacity a bit, and thinking about the resurrection is even more difficult while hooked up to a nebulizer with albuterol than is usually the case. Mercifully, many of my responses to this batch of criticism were pre-empted, rather eloquently, by this batch of counter-criticism.

A few thoughts on this question: given the many contemporaneous accounts of other religious figures rising from the dead (indeed several in  the Bible itself), and given that all Christians are supposed to rise bodily from the dead as well, why is Jesus so special? Why is he “consubstantial with the Father” in ways other resurrected beings are not?

the Bible itself), and given that all Christians are supposed to rise bodily from the dead as well, why is Jesus so special? Why is he “consubstantial with the Father” in ways other resurrected beings are not?

The obvious answer to this is that the early Christians obviously believed that he was uniquely divine in some form. Ehrman makes a good case that Jesus was viewed as special by his disciples in his lifetime because they deemed him to be the Jewish Messiah who would reign supreme at the end of the world. The specialness of his being the Jewish Messiah was then combined with the staggering revelation that he had risen from the dead. It was that combination – a resurrected Messiah – that upped the ante, setting the seeds for the gradual evolution of the doctrine of the Incarnation and the Trinity. The story of Apollonius, otherwise very close to the story of Jesus, lacked the Messiah prophesy. And it also lacked the retroactive examination of the Hebrew Bible for various prophesies to be fulfilled in Jesus.

Moreover, as Ehrman notes, although there were countless semi-divine characters and resurrected prophets in the early Christian era, even though the human-divine admixture included angels and strange gods and the off-spring of unnatural sex between gods and humans, only  two people were ever designated the “Son Of God.” One was the Roman Emperor, Caesar Augustus, and the other was Jesus, a rural apocalyptic preacher from Galilee. That is some elevated company to keep and it begs the question: why Jesus and no one else? What was so special about him?

two people were ever designated the “Son Of God.” One was the Roman Emperor, Caesar Augustus, and the other was Jesus, a rural apocalyptic preacher from Galilee. That is some elevated company to keep and it begs the question: why Jesus and no one else? What was so special about him?

What’s frustratingly lacking in Ehrman’s book – and it’s not its subject so it’s not Ehrman’s fault – are the teachings of Jesus and the way he lived. I don’t think you can understanding the full impact of the resurrection outside the disciples’ experience of the living Jesus, with his teachings and his healings and his miracles. For me, these remarkable stories are the missing tissue here. It is one thing for a prophet to be put to a gruesome death; it is another thing when that prophet lived and taught in such a way that he seemed to revolutionize human consciousness and then was put to death.

Jesus inverted so much of the world’s familiar lessons: don’t protect yourself in a dangerous world, make yourself vulnerable; don’t seek revenge on those who have wronged you, give them another chance to wrong you; don’t just love your friends, but love your enemies; don’t live abstemiously, give everything you have away to the poor; don’t worry about tomorrow, today will be taken care of; by all means obey the rules but never if they violate the deeper rule of love. Above all: love one another. These stories and sayings and teachings carry huge impact  today, even though we have lived with them for centuries. But I try to imagine myself as one of the disciples, busily fishing in the Sea of Galilee, and not only being astounded by these ideas, but dropping my life and abandoning my family altogether and following him because of the power of his ideas and example.

today, even though we have lived with them for centuries. But I try to imagine myself as one of the disciples, busily fishing in the Sea of Galilee, and not only being astounded by these ideas, but dropping my life and abandoning my family altogether and following him because of the power of his ideas and example.

Then, in a sudden development, this radically non-violent individual is seized under false pretenses and brutally tortured to death. And again, even here, it is not so much his death that resonates as the manner of his death. He refused to defend himself; he embraced the ridicule; he forgave the men driving nails into his wrists; he reached out in love to one of the poor souls hanging next to him; and he despaired. This happens after most of his loved ones either denied ever knowing him or fled. Only the women who loved him and the disciple Jesus loved stayed behind.

Now put yourself in the place of those bewildered, terrified, disloyal former followers.

In this miasma of fear, guilt, grief and disorientation, they suddenly see Jesus alive and walking around in various visions and mysterious manifestations. There you have the whiplash of the resurrection, and the obvious desire of the disciples to believe that all of it must mean something more profound than merely that Jesus was a man of God who was unjustly put to death. He was more than that to them – and the resurrection made that indelible. And I find it perfectly reasonable to see why the disciples began to tell and re-tell the stories of Jesus life as a way to keep him alive in their hearts and minds and to buttress and deepen the meaning of this revelation. I find it perfectly human to re-enact his last supper with them as a way to keep his memory and his presence in their lives.

In other words, Occam’s razor needs to take into account the life-changing ideas and the soul-changing way of life Jesus of Nazareth gave the world. When I say a deeper perfection lies behind the fallible game of telephone that the Gospels are, I mean simply this. The words that Jefferson excavated, the stories that Tolstoy marveled at, the way of life that Francis of Assisi embraced, all of this and so much more come from this man’s words and life. There is always something astounding when the victims of violence refuse to fight back and seek to love instead. It defuses all of our evolutionary impulses. It negates what was previously thought of as human. It instantly makes one think of something divine.

In other words, Occam’s razor needs to take into account the life-changing ideas and the soul-changing way of life Jesus of Nazareth gave the world. When I say a deeper perfection lies behind the fallible game of telephone that the Gospels are, I mean simply this. The words that Jefferson excavated, the stories that Tolstoy marveled at, the way of life that Francis of Assisi embraced, all of this and so much more come from this man’s words and life. There is always something astounding when the victims of violence refuse to fight back and seek to love instead. It defuses all of our evolutionary impulses. It negates what was previously thought of as human. It instantly makes one think of something divine.

There are many ways of understanding this, and Christians, as Ehrman shows, came up with countless permutations on the notion of God-Made-Flesh within the Trinity. None of it makes any worldly sense, the Trinity especially. It makes sense only as paradox and mystery, not as literal truth. And so I do not have a firm belief in the bodily resurrection of Jesus, because the Gospels don’t either. He is a vision, an angel, a man who walks through doors only to reveal himself in the flesh … and then he withdraws again from view. There is no single, literal account in the Jesus stories of his resurrection, which is one reason I prefer to leave its precise contours a little opaque. Ehrman suggests the conviction that Jesus had risen from the dead might be an instance of a very common form of vision of recently dead loved ones – which was not unique to the disciples but witnessed countless times across the globe then and now. And I sure keep that option open.

But because it is a mystery, I do not discount the possibility of a literal resurrection either. What matters to me is the life-changing message of Jesus, potent and rendered in unforgettable metaphor and parable, lived by him to the astonishment of all who encountered him, and speaking of a form of justice, of life and of love that we rightly associate with some power beyond us – because so much in our evolutionary make-up screams against it and yet somewhere within us we recognize it is the only transcendence we are capable of. In that sense, Jesus was the intersection of timeless truth with time. And nothing could be more miraculous in the long and brutal history of humankind than that.

(The entire discussion for How Jesus Became God is compiled here. Please email any responses to bookclub@andrewsullivan.com rather than the main account, and please keep them under 500 words.

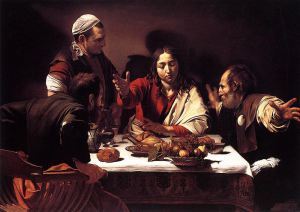

Photos: the road to Emmaus by Caravaggio; the Epstein statue of Lazarus in New College, Oxford; my own personal Jesus; and a cross at Hatches Harbor at the end of Cape Cod.)

A Global Tax On The Super Rich? Ctd

As the econobloggers dig into Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century, Felix Salmon notices a consensus emerging:

The many reviews of Piketty’s book are surprisingly unanimous on one point: that the weakest part of the book is the final part, where Piketty moves away from diagnosis and starts attempting to formulate a solution. Piketty’s rather French idea of a global wealth tax isn’t getting nearly the same amount of acclaim as the rest of the book is, and is very unlikely to happen: countries will always compete with each other to attract the stateless rich by not taxing them.

Which means that my reading of Piketty is ultimately pessimistic. The dynamics of the world economy are bad, and they’re getting worse; inequality is natural in human history, and right now we’re reverting to a state of affairs which is highly unfair but also both sustainable and, in its own way, unsurprising. Piketty has diagnosed a nasty condition. But I don’t think there’s a cure.

Ryan Avent’s take on Part 4 exemplifies that consensus:

The economics gets a serious treatment in this book, but the politics does not. That’s somewhat ironic; Mr Piketty winds down his conclusion by saying that economics should focus less on its aspirations to be a science and return to its roots, to political economy. But theories of political economy should be theories of politics. And there is no r>g for politics in this book.

There are nods at the importance of the interdependence between the political and economic. He notes that epoch-ending political shifts, like the French and American revolutions, were motivated in large part by fiscal questions. Similarly, he observes that progressive income taxation tended to emerge alongside the development of democracy and the expansion of the franchise. (Though, he also admits, the fiscal demands of world war one deserve most credit for adoption of meaningful income taxation across the rich world.) And he discusses how concern about rising inequality (often among elites) helped motivate rising tax rates in America in the early 20th century.

But the ending the book deserved was another look back at the data, to see whether patterns in the interaction between wealth concentration and political shifts could be detected and described. That’s not Mr Piketty’s area of expertise, necessarily, but neither is most of the stuff in Part 4.

Tyler Cowen points to a review by Ryan Decker that also criticizes Piketty’s conclusion:

Piketty’s data on the rise of middle-class capital ownership raise an important point. A key theme of the book is that poor people don’t own productive assets, so they must rely entirely on labor for income. But is taxation and redistribution the only way to address this situation? This poses a difficult question for those who oppose some form of privatization of government retirement programs. One cannot simultaneously claim that owners of capital stand to gain absurd riches in coming decades and that privatization and choice for Social Security is a terrible idea.* This is not the only possible alternative to taxation, but it is a reminder that one way to treat the problem of poor people not owning stuff may be to help poor people, well, own more stuff. But Piketty simply asserts that “only a progressive tax on capital can effectively impede” increasing wealth concentration (439). More generally, Piketty decries the ability of those with large fortunes to access opportunities for higher rates of capital return than those with smaller starting funds, but he makes no mention of the fact that this is due in part to laws banning small investors from participating in alternative investments. By law, if I want to invest in a startup, I can only do it in undiversified ways (like starting my own firm or investing in a friend’s). We don’t need higher taxes to help lower classes invest better.

Though he praises Piketty’s history of inequality and wealth, Greg Mankiw takes issue with his predictions and prescribed solution:

As we all know, you can’t get “ought” from “is.” Like President Obama and others on the left, Piketty wants to spread the wealth around. Another philosophical viewpoint is that it is the government’s job to enforce rules such as contracts and property rights and promote opportunity rather than to achieve a particular distribution of economic outcomes. No amount of economic history will tell you that John Rawls (and Thomas Piketty) offers a better political philosophy than Robert Nozick (and Milton Friedman).

The bottom line: You can appreciate his economic history without buying into his forecast. And even if you are convinced by his forecast, you don’t have to buy into his normative conclusions.

Douthat, on the other hand, credits the Frenchman with helpfully complicating our national conversation about inequality:

Piketty’s book, as my colleague David Brooks suggests today, has ended up folded into that “we are the 99 percent” framework by some of its interpreters. But I’m not sure it completely belongs there. Indeed, insofar as he focuses on capital more than income, raises the issue of the petits rentiers and their increasing patrimonies, and … explicitly talks about the 10 or 12 or 15 percent and not just the 1 percent, I think Piketty implicitly challenges that framework, and in the process raises much harder questions for his professional-class liberal readers … because he’s saying, in effect, that they too are the problem, they too are part of the anti-egalitarian trend, in ways that the comforting “we are the 99 percent” narrative doesn’t capture or admit.

Catch up on the Dish’s coverage of Capital here, here, here, and here.

Face Of The Day

Egyptian defendants’ relatives mourn after an Egypt court refers 638 Morsi backers, including the Muslim Brotherhood leader Mohammed Badie, to the death sentence in the latest mass trial in the southern city of Minya, Egypt on April 28, 2014. By Ahmed Ismail/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images. Previous Dish on the first round of mass convictions here.

Maduro’s Political Theater

José Cárdenas calls the peace talks that began in Venezuela late last week a “scam” and warns the US not to fall for it:

What observers need to be aware of is that the opposition representatives arrayed around the negotiating table and those protesting in the streets are not one and the same. As I have written before, the protests began as spontaneous, organic eruptions of student discontent over street crime and economic hardship under chavismo. They were neither called for nor led by the organized opposition forces. As such, the latter does not have the power to turn them on or off depending on which crumbs the government decides to dole out.

All of this means that negotiations will not end Venezuela’s crisis — only real reforms will. Effective reforms would arrest the economic freefall wrought by the hare-brained statist policies of Maduro and his Cuban advisors, and re-establish credible institutions to channel discontent and foster real debate about the future of the country. The problem with that scenario is that to Maduro, all opposition is illegitimate and deserves no voice in the country’s affairs.

Javier Corrales analyzes the class politics of Venezuela’s crisis, disputing the government’s claim that the protesters are too bourgeois to represent the general population:

The claim that the protesters are “too middle class” implies a double criticism. The first is about values: The protesters are imputed to be embracing values that are somewhat elitist, or at least, unpopular among the bulk of Venezuelans, the so-called popular classes. The second is about politics: The protesters have failed to expand their political coalition. They remain circumscribed to a mere quarter of the population.

These criticisms deserve closer scrutiny. Venezuela has been classified as an “upper middle-income” country for decades. Furthermore, the government claims that the country has seen an expansion in the size of the middle class since 2004. In that case, observing that the protests are too middle class seems unworthy of note: What else would one expect from such a country? If there were going to be discontent, especially about governance issues, it would come from the middle classes.

Previous Dish on the Venezuelan crisis here and here.

The Soaring Suicide In South Korea, Ctd

South Korean prime minister resigns over ferry disaster: http://t.co/4ZFL9epSxf #c4news pic.twitter.com/CuEUbKQnwS

— Channel 4 News (@Channel4News) April 27, 2014

A reader is put off by this post:

I’m staggered that you used the South Korean ferry tragedy as an excuse to run an unhinged rant by an entitled Westerner about the alleged lack of professionalism in “Korean business culture at large”. The Asiana crash was possibly human error – so were plenty of crashes in the West. Korean firms cut corners? General Motors is currently in the news for ignoring a critical problem for years while people were dying. Didn’t your reader wonder for a moment how such an unprofessional bunch of losers, in a country smaller than many American states, managed to build companies like Samsung, LG, Hyundai, Kia, Lotte, that are household names the world over?

The supposed “entitled Westerner” clarified where he’s coming from:

I am Korean-American-British. My family immigrated before I was born from Korea to the US. I spent most of my 20s in the UK where I got naturalized, and then moved to Seoul a year ago. Over the past year I’ve been cataloging a variety of facets of Korean culture that are in need of reform, the biggest areas being sex, business, and education. One thing I’ll give to Koreans is they are very good at introspection when they are put under the spotlight. The chapter on Korean Air in Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers caused a big stir, but now one of the biggest hagwons (after-school academy) uses it as a source text.

By the way, I should clarify that the comparison to 9/11 is not something I’ve heard on the Korean press; it’s a purely personal observation based on:

the level of media saturation

anguish due to the man-made nature of incident

innocence of victims (high school kids going on vacation!)

high numbers of missing, presumed dead but not confirmed

logistical difficulty of the rescue effort

numbers relative to population (about 300 out of 50 million)Also, I was half a mile from Ground Zero on 9/11, so it jumps more readily to my mind.

Another reader:

I wanted to give you a slightly different take on what is happening in S. Korea at the moment.

I’ve been teaching English here for the past three years, and I’ve had my share of ups and downs with the people and the culture. Sure, they work too hard, and it’s from start to finish. The kids have homework on every single vacation, which kind of misses the point of vacation, and by the time they hit middle school most of them go to school and academies from 8 in the morning to 8 or 9 at night.

Once they become adults, as your other reader said, face-time is what counts. It’s quite normal to work 6 days a week here for 10 hours a day, no matter your position. Most people are lucky to get one full week of vacation, and good luck with sick days.

Still, one must marvel at what they’ve accomplished here in such a short time. Since the opening up of the economy in the ’60s and ’70s, Korea has served as a model for what is possible. The technological capacity on display here would put most of America to shame. Honestly, you can’t blame them for how hard they work either. My bosses saw their world destroyed during the Korean War. To go from being a citizen of a war-torn, underdeveloped nation to a citizen of modern-day Korea, well one could understand why Koreans value a good work ethic.

That said, they are reeling as a country right now. It’s ironic when you think about it. This is a country that has been at war for roughly 60 years. They have an unpredictable, nuclear-obsessed neighbor to the north that likes to remind them of their situation from time to time. I was here when N. Korea bombed the western island of Yeonpyeong in 2010. It was both tragic and important, but this is so much bigger. Let’s put it this way: think about the firestorm of media coverage that happens every time N. Korea does something provocative compared to the coverage of the sinking of the ferry, and reverse it. That’s what the coverage is like here.

After living here for a few years, I feel as though I can understand why it’s that way too. Children are everything here (I know they are everywhere, but hear me out). When you look at the amount of money parents spend on their children in S. Korea as a percentage of their overall income, it’s staggering. So much is put into providing children with every possible advantage. It’s super competitive and failure isn’t viewed as an option. In turn, the children (specifically first-born sons) are expected to return the favor once parents are ejected from the work force. Children are very sheltered to the dangers of the outside world. It’s extremely safe here (even with N. Korea lurking), and when that illusion of safety gets shattered by an event such as this, it can be very difficult to deal with the feelings afterwards.

Event after event has been and is being cancelled (festivals, races, trips). I was talking to some middle-schoolers today as a matter of fact, and they said all of their school trips for the rest of the year (the school year just started in March) are cancelled. Not only is everything currently being cancelled, but there is the issue of suicide. It isn’t surprising at all to me that the assistant principal killed himself, and don’t be surprised if any of the surviving crew members, especially the captain, do so as well. For Koreans, this is taking responsibility (in fact, this is what the principal said in his note).

As an outsider with a Western point of view, it’s very sad to watch everything unfold. The idea that suicide is a way out is so difficult to grasp. How is killing yourself taking responsibility for the deaths of so many students? Be there for the families and the rest of your students. Help people get through this tragedy. Don’t take the easy way out and leave the survivors to deal on their own. Now is when you should be coming together. Stop canceling events. Do them in memory of those lost. Dedicate everything you do to those people who lost their lives. You are still here, so embrace it.

Another:

Sorry I’m late to this conversation, but I live in South Korea, so I get your posts late. I was a journalist here, and now I’m a lawyer here. I speak Korean fluently. I went to college here. I like to think I know Korea pretty well, and the stuff your readers have submitted strikes me as totally wrong.

Yes, there is a problem with Korean culture that is absolutely behind the rash of accidents and poor responses that plagues Korea, and it’s not Confucianism or bad business practices. It’s a complete lack of safety. This is something so deeply ingrained in Korea that it permeates the culture. I doubt Koreans themselves are aware of how incredibly reckless they are compared to people elsewhere.

People in Korea do not look where they are going when walking. If they bump into someone, they keep walking without saying a word. When they drive, it is a mad rush to get in front of everyone, to the point that newcomers are advised to run red lights just to avoid being rammed. Builders cut corners; investors leap before looking; the South’s generals go golfing when the North threatens apocalypse Everything here is done “bbali bbali,” meaning “fast fast,” which they are very proud of. It is easy to see how that runs the gamut from not looking where you’re going to cutting corners in order to get that ferry to port, ASAP.

For that reason, I chuckled when I saw your reader describe Korea as “safe.” The fact that there is very little visible violent crime does not make Korea “safe.” It is, in fact, very dangerous if you drive, live in or near tall buildings, fly airplanes, take ferries, invest your money, or come within artillery range of the DMZ.

As I was pondering this coming back from the morning workout, I almost creamed a man with my car. I was driving down a narrow curving ramp into my building’s parking lot. He was walking up the middle of it, because … hey, it’s a short-cut.

Andrew Sullivan's Blog

- Andrew Sullivan's profile

- 153 followers