John G. Messerly's Blog, page 91

May 26, 2016

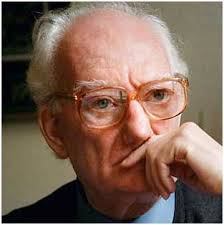

Review of Bryan Magee’s, “Ultimate Questions”

Bryan Magee (1930 – ) has had a multifaceted career as a professor of philosophy, music and theater critic, BBC broadcaster, public intellectual and member of Parliament. He has starred in two acclaimed television series about philosophy: Men of Ideas (1978) and The Great Philosopher (1987). He is best known as a popularizer of philosophy. His easy-to-read books, which have been translated into more than twenty languages, include:

Confessions of a Philosopher: A Personal Journey Through Western Philosophy from Plato to Popper;

The Great Philosophers: An Introduction to Western Philosophy;

Talking Philosophy: Dialogues with Fifteen Leading Philosophers ;

;

Philosophy and the Real World: An Introduction to Karl Popper;

The Story of Philosophy: 2,500 Years of Great Thinkers from Socrates to the Existentialists and Beyond ;

;

and Men of Ideas.

Now, at age 86, he has written Ultimate Questions, a summary of a lifetime of thinking about “the fundamentals of the human condition.” Its basic theme is that we know little about the human condition, since reality comes to us filtered through senses and the limitations of our intellect and language. And the most honest response to this predicament is to remain agnostic.

Magee begins considering that “What we call civilization has existed for something like six thousand years.” If you remember that there have always been some individuals who have lived a hundred years this means that “the whole of civilization has occurred with the successive lifetimes of sixty people …” Furthermore, “most people are as provincial in time as they are in space: they huddle down into their time and regard it as their total environment…” They don’t think about the little sliver of time and space that they occupy. Thus begins this meditation on agnosticism.

Furthermore, we are ignorant of knowledge of our ultimate nature: “We, who do not know what we are, have to fashion lives for ourselves in a universe of which we know little and understand less.” Yet this situation doesn’t lead Magee to despair. Instead he calls for “an active agnosticism,” which is “a positive principle of procedure, an openness to the fact that we do not know, followed by intellectually honest enquiry in full receptivity of mind.” If he had to choose a tag he says, it would be “the agnostic.”

However most people can’t live with uncertainty, with pieces missing from the jigsaw puzzle as Magee puts it, and they replace the unknown with religion. But religion “is a form of unjustified evasion, a failure to face up to the reality of ignorance as our natural and inevitable starting-point.” The challenge of life is to live and die in a world we admit we don’t understand “without either … denying the mysteriousness of it or … grasping at supernatural explanations.”

Yet he takes comfort in a world that is what he calls “us-dependent,” rather than independent or isolated: “One essential aspect of our situation is that we are social creatures, indeed social creations: each one of us is created by two other people. If we are not cared for by them or someone taking their place, we die. Our existence and our survival both require active involvement by others.”(What a beautiful rejoined to all those supposedly self-made men. Those who were born on third base and think they hit a triple!)

In the broadest light, the entire book attempts to reply to the assertion: “I know that I exist, but I do not know what I am.” But Magee, after decades of searching, replies that none of us know the answers to the big questions. As for faith, Magee answers firmly: “I can think of no other context in which people are commended for the firmness of beliefs for which there is little or no evidence.” Magee accepts that some need the comfort of religion because, for example, they can’t accept their own death, and he leaves such people undisturbed. “But I do regard such people as no longer committed to the pursuit of truth.”

Magee believe contra Hume that he has a self “but I am unable to fathom its inner nature, and I have no idea what happens to it when I die.” But he rejects the view that being unable to answer ultimate questions implies that asking them is worthless, inasmuch as some understanding of our self and the world can still be attained. “We may not know where we are, but there is a world of difference between being lost in daylight and being lost in the dark.” Still none of this implies relativism, as reason and evidence support some ideas and theories over others.

As for death, “the prospect of permanent oblivion” is painful. In death the magic of the world will vanish. Nonetheless, the brave face this truth without comforting themselves with false narratives. Magee says that at the moment of death “I may then be in the position of a man whose candle goes out and plunges him into pitch blackness at the very instant when he thought he was about to find what he was looking for.” These are the words of a brave and fearless intellect. What a wonderful book.

May 21, 2016

The Injustice of Sexism

I agree with the article completely, and I believe any woman who tells me the article speaks to their concerns. But it did get me to thinking about how to respond to this injustice or to any injustice. In the simplest language I’d say something like: we should try to make the world more just while remembering at the same time that there is a lot of good in life too. I know this is trite, but the point is to maintain a creative tension between being dissatisfied with injustice enough to want to remedy it, but not so dissatisfied that you sour on life and miss its beauty.

Of course this is easy for a white male who has never been discriminated against to say. Moreover I have sufficient food, clothing, and shelter—as well as time to blog. For those who are starving, imprisoned, enslaved, etc. there is nothing one can say except that such injustices should be eradicated. So I address my concerns mostly to first world people who nonetheless face grave injustice. But again I can’t understand how difficult it is to be black or gay or a woman in that world either.

The only thing I might say is that we should all be sympathetic with each other. Consider that racism is about understanding the unique obstacles blacks face; understanding xenophobia about understanding the unique obstacles that immigrants face, understanding sexism is about understanding the obstacles unique women face. And all these groups face obstacles that white men don’t for sure. But when I taught existentialism it always reminded me how hard it is to just be human. Not as hard as being humans who face additional barriers, but hard nonetheless. Yet I do agree that being black or female or nowadays in the USA, mexican or muslim makes things much harder.

Again I know this is trite and I so wish we could undo the world’s injustices. There is something amiss about the reality we live in, and I’d guess it has something to do both with ourselves and the stars. But if we change ourselves then we might change the stars too.

May 16, 2016

William James: Once Born and Twice Born People

(This entry relies heavily on this article from the website The Pursuit of Happiness.)

In his famous book, The Varieties of Religious Experience, William James draws a contrast between what he calls “once born” and the “twice born” people. Once born people appear biologically predisposed to happiness. They accept life, and they seemed untroubled by their own setbacks as well as by the suffering the world. They never speak ill of others, and they never complain about much at all. They tend not to be fearful or angry. Today we might call them happy-go-lucky, easy-going or upbeat.

By contrast twice borns feel there is something wrong with reality that must be rectified. They have a pessimistic view of the world; they experience more ups and downs in life; they wish the world could be different from it is. James describes them like this:

There are persons whose existence is little more than a series of zigzags, as now one tendency and now another gets the upper hand. Their spirit wars with their flesh, they wish for incompatibles, wayward impulses interrupt their most deliberate plans, and their lives are one long drama of repentance and of effort to repair misdemeanors and mistakes. (p.169)

However this doesn’t mean that twice borns are unhappy. The reason for is that the attitude of twice borns often leads to a crisis, experienced as clinical depression, in a desire to understand the meaning of life. This desire for making sense of things is incompatible with their pessimism, and thus demands a resolution if life is to be loved again. As an example, James considers the crisis of meaning experienced by Leo Tolstoy. James describes Tolstoy’s transformation like this: “The process is one of redemption, not of mere reversion to natural health, and the sufferer, when saved, is saved by what seems to him a second birth, a deeper kind of conscious being than he could enjoy before. ” (p.157)

While the sense of being “born again” often describes so-called religious or mystical experiences, James uses the term to describe any experience where there is a strong sense of renewal after a tragic event. The point is that challenges and tragedies can be seen as a means to a deeper and more meaningful life.

In terms of happiness, James said that there are four main ingredients for a happy life. First we choose to view the world as positive even though life contains sorrow and pain. Second we must take risks by acting from the demands of our hearts. Third we must act as if we are free and life is meaningful even though we can’t be sure that any of this is true. Finally we should remember that some of the happiest and most important people in history were often transformed after experiencing a deep depression caused primarily by a loss of meaning. Thus a crisis for twice borns presents the possibility of renewal.

Postscript – William James knew a lot about this, as he suffered from depression for much of his life. A number of other people of historic importance suffered from depression as well including: Abraham Lincoln, Sigmund Freud, Georgia O’Keeffe, William Tecumseh Sherman, Franz Kafka, and the Buddha. I really think there is a lot to this, although that doesn’t mean that pain and suffering are intrinsically good. They are not. Still, given the reality we live in and the ubiquity of suffering, we do best by trying to learn from it and thus reduce its power as much as possible. The stronger view, that suffering is somehow necessary for redemption, was captured in these lines by Shelley:

We look before and after,

And pine for what is not:

Our sincerest laughter

With some pain is fraught;

Our sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest thought.

Yet if we could scorn

Hate, and pride, and fear;

If we were things born

Not to shed a tear,

I know not how thy joy we ever should come near.

May 15, 2016

Reply to Ms. Aurora Griffin on Abortion

While writing my last post on abortion I came across an anti-abortion piece written a few years ago by a Harvard undergraduate, Ms. Aurora Griffin. Having taught philosophical ethics to undergraduates for 30 years, I’m always happy to see an undergrad bold enough to wade into the philosophical waters. However, knowing the ins and outs of the argument in great detail, it is easy to see where Ms. Griffin’s argument goes awry.

Ms. Griffin argues that there are arguments from both philosophy and science that support her pro-life position. She says the philosophical argument “is that all human beings have the right to life because they are human,” and the scientific argument is “[human] life … begins at conception” because then “it has human DNA …”

Ms. Griffin does seems to recognize that these arguments don’t work because there is a difference between being biologically human, or having human DNA, and being a person who is a member of the moral community. Perhaps she has read Mary Anne Warren’s devastating critique of John Noonan’s notoriously weak argument, where Warren points out that being biologically human doesn’t mean you are a person, nor does the lack of a human DNA mean that you aren’t a person. There may be things that are biologically human but not persons—like zygotes, the recently deceased, and people in persistent vegetative states—and there may be things that aren’t biologically human but are persons—like intelligent aliens, cyborgs or robots. So having human DNA doesn’t mean that you are a person or a member of the moral community. After all, a swab of human saliva has human DNA but it not a person.

Sensing that personhood rather than biologically humanity is the key point, Griffin offers this argument. “If the human is a person only when neurologically functioning as a human, then by that same argument it would be permissible to kill people while they are in deep sleep, in comas, or mentally handicapped.” This argument is especially fatuous.

First, neurological functioning may be one of the necessary conditions for personhood, and one which the zygote without a brain clearly does not satisfy. It is hard to see how any entity that completely lacks consciousness is a person in any usual sense of the word. And, as is well-known in the literature, fetuses satisfy none of the criteria for personhood till well along in their development.

Second, the argument is a disguised version of a well-known informal logical fallacy known as the slippery slope. Ms. Griffin appears to believe that if we allow abortion in the early stages then sleeping and mentally handicapped people will be killed. Of course this doesn’t follow, since the sleeping and mentally challenged clearly have neurological activity—it is not as if they completely lack consciousness like early trimester fetuses.

All of this leads to Ms. Griffin’s conclusion that only “if the fetus is not a person and we know it definitively, is abortion morally permissible.” Of course we do know that the early fetus does not satisfy any of the criteria of personhood by any reasonable philosophical definition of the word, and we also know this beyond any reasonable doubt based on the science of embryological development.

Finally we might note that the majority view among ethicists by a large margin is that the pro-life arguments fail, primarily because the fetus satisfies few if any of the necessary and sufficient conditions for personhood. The impartial view, backed by contemporary biology and philosophical argumentation, is that a zygote is a potential person. That doesn’t mean it has no moral significance, but it does mean that it has less significance than an actual person. An acorn may become an oak tree, but an oak tree it is not. You may believe that your God puts souls into newly fertilized eggs, thereby granting them full personhood, but that is a religious belief not grounded in science or philosophical ethics.

May 10, 2016

Ethicists Generally Agree: The Pro-Life Arguments Are Worthless

Abortion continues to make political news, but a question rarely asked by politicians or other interlocutors is: what do professional ethicists think about abortion? If ethicists have reached a consensus about the morality or immorality of abortion, surely their conclusions should be important. And, as a professional ethicist myself, I can tell you that among ethicists it is exceedingly rare to find defenders of the view that abortion is murder. In fact, support for this anti-abortion position, to the extent it exists at all, comes almost exclusively from the small percentage of philosophers who are theists. Yet few seem to take notice of this fact.

To support the claim that the vast majority of ethicists don’t favor the pro-life position, consider the disclaimer that appears in the most celebrated anti-abortion piece in the philosophical ethics literature, Don Marquis’ “Why Abortion Is Immoral.” Marquis begins:

The view that abortion is, with rare exceptions, seriously immoral has received

little support in the recent philosophical literature. No doubt most philosophers

affiliated with secular institutions of higher education believe that the anti-abortion position is either a symptom of irrational religious dogma or a conclusion generated by seriously confused philosophical argument.

Marquis concedes that abortion isn’t considered immoral according to most ethicists, but why is this? Perhaps professional ethicists, who are typically non-religious philosophers, find nothing morally objectionable about abortion because they aren’t religious. In other words, if they were devout they would recognize abortion as a moral abomination. But we could easily turn this around. Perhaps religiously oriented ethicists oppose abortion because they are religious. In other words, if there weren’t devout they would see that abortion isn’t morally problematic. So both religious and secular ethicists could claim that the other side prejudges the case.

However, it is definitely not the case that secular ethicists care less about life or morality than religious ethicists. Consider that virtually all moral philosophers believe that murder, theft, torture, and lying are immoral because cogent arguments such prohibitions. Oftentimes there is little difference between the views of religious and secular ethicists. Moreover, when there is disagreement among the two groups, perhaps the secular philosophers are actually ahead of the ethical curve with their acceptance of things like abortion, homosexuality, and certain forms of euthanasia.

How then do we adjudicate disputes in the moral realm when ethicists, like ordinary people, start with different assumptions? The key to answering this question is to emphasize reason and argument, the hallmarks of doing philosophical ethics. Both secular and religious individuals can participate in a forum of rational discourse to resolve their disputes. In fact, natural law moral theory—the dominant ethical theory throughout the history of Christianity—claims that moral laws are reasonable, which means that what is right is supported by the best rational arguments. Natural law theorists argue that by exercising the human reason their God has given them, they can understand what is right and wrong. Thus secular and religious philosophers work in the same arena, one where moral truths are those supported by the best reasons.

That ethicists emphasize rational discourse may be counter-intuitive in a society dominated by appeals to emotion, prejudice, faith, and group loyalty. But ethicists, secular and religious alike, try to impartially examine the arguments for and against moral propositions in order to determine where the weight of reason lies in the matter. Ethicists may not be perfect umpires, and the truth about moral matters is often difficult to tease out, but ethicists are trained to be impartial and thorough when analyzing arguments. Some are better at this than others, but when a significant majority agrees, it is probably because some arguments really are stronger than others.

Now you might wonder what make ethicists better able to adjudicate between good and bad arguments than ordinary people. The answer is that professional ethicists are schooled in logic and the critical thinking skills demanded by those who carefully and conscientiously examine arguments. They are also trained in the more abstract fields of meta-ethics, which considers the meaning of moral terms and concepts, as well as in ethical theory, which considers norms, standards, or criteria for moral conduct. Moreover, they are familiar with the best philosophical arguments that have been advanced for and against moral propositions. So they are in a good position to reject arguments that influence those unfamiliar with positions that oppose their favored ones.

All this education doesn’t mean that the majority of ethicists are right, so individuals who disagree with them may choose to follow their own conscience. But if the vast majority of ethicists agree about an ethics issue, we should take notice. It might be that the reasons you give for your fervently held moral beliefs don’t stand up to critical scrutiny. Perhaps they can’t be rationally defended as well as those reached after conscientious, informed, and impartial analysis. This doesn’t mean that you should ignore your conscience and accept expert opinion, but if you are serious about a moral problem you should want to know the views of those who have thoroughly studied the issue.

At this point you might object that there are no moral experts because ethics is relative to an individual’s opinions or emotions. You might say that the experts have their opinion and you have yours, and that’s the end of it. Perhaps behaviors in the moral realm are just like carrots—some people like them and some don’t. This theory is called personal moral relativism. However, not only do most ethicists reject moral relativism, so must pro-lifers. After all, pro-lifers think that the moral prohibition against abortion is relative; they thinks its absolute. They believe that there are good reasons why abortion is immoral that any rational person should accept. However these reasons must be evaluated to see if they are really good ones; to see if they convince other knowledgeable persons. Yet so far, the pro-life arguments haven’t persuaded many ethicists.

Lacking good reasons or armed with weak ones, many will object that their moral beliefs derive from their God. To base your ethical views on Gods you would need to know: 1) if Gods exists; 2) if they are good; 3) if they issue good commands; 4) how to find the commands; and 5) the proper version and translation of the holy books issuing commands, or the right interpretation of a revelation of the commands, or the legitimacy of a church authority issuing commands. Needless to say it is hard, if not impossible, to know any of this.

Consider just the interpretation problem. When does a seemingly straightforward command from a holy book like, “thou shalt not kill,” apply? In self defense? In war? Always? And to whom does it apply? To non-human animals? Intelligent aliens? Serial killers? All living things? The unborn? The brain dead? Religious commands such as “don’t kill,” “honor thy parents,” and “don’t commit adultery” are ambiguous. Difficulties also arise if we hear voices commanding us, or if we accept an institution’s authority. Why trust the voices in our heads, or institutional authorities?

For the sake of argument though, let’s assume: that there are Gods; that you know the true one; that your God issues good commands; that you have access to them because you have found the right book or church, or had the right vision, or heard the right voices; and that you interpret and understand the command correctly—even if they came from a book that has been translated from one language to another over thousands of years or from a long ago revelation. It is unlikely that you are correct about all this, but for the sake of the argument let’s say that you are. Even in that case most philosophers would argue that you can’t base ethics on your God.

To understand why you can’t base ethics on Gods consider the question: what is the relationship between the Gods and their commands? A classic formulation of this relationship is called the divine-command theory. According to divine command theory, things are right or wrong simply because the Gods command or forbid them. There is nothing more to morality than this. It’s like a parent who says to a child: it’s right because I say so. To see how this formulation of the relationship fails, consider a famous philosophical conundrum: “Are things right because the Gods command them, or do the Gods command them because they are right?”

If things are right simply because the Gods command them, then their commands are arbitrary. In that case the Gods could have made their commandments backwards! If divine fiat is enough to make something right, then the Gods could have commanded us to kill, lie, cheat, steal and commit adultery, and those behaviors would then be moral. But the Gods can’t make something right, if it’s wrong. The Gods can’t make torturing children morally acceptable simply by divine decree, and that is the main reason why most Christian theologians reject divine command theory.

On the other hand, if the Gods command things because they are right, then there are reasons for the God’s commands. On this view the Gods, in their infinite wisdom and benevolence, command things because they see certain commands as good for us. But if this is the case, then there is some standard, norm or criteria by which good or bad are measured which is independent of the Gods. Thus all us, religious and secular alike, should be looking for the reasons that certain behaviors should be condemned or praised. Even the thoughtful believer should engage in philosophical ethics.

So either the Gods commands are without reason and therefore arbitrary, or they are rational according to some standard. This standard—say that we would all be better off—is thus the reason we should be moral and that reason, not the Gods’ authority, is what makes something right or wrong. The same is true for a supposedly authoritative book. Something isn’t wrong simply because a book says so. There must be a reason that something is right or wrong, and if there isn’t, then the book has no moral authority on the matter.

At this point the believer might object that the Gods have reasons for their commands, but we can’t know them. Yet if the ways of the Gods are really mysterious to us, what’s the point of religion? If you can’t know anything about the Gods or their commands, then why follow those commands, why have religion at all, why listen to the priest or preacher? If it’s all a mystery, we should remain silent or become mystics.

In response the religious may say that, even though they don’t know the reason for their God’s commands, they must oppose abortion because of the inerrancy of their sacred scriptures or church tradition. They might say that since the Bible and their church oppose abortion, that’s good enough for them, despite what moral philosophers say. But in fact neither church authority nor Christian scripture unequivocally oppose abortion.

As for scriptures, they don’t generally offer specific moral guidance. Moreover, most ancient scriptures survived as oral traditions before being written down; they have been translated multiple times; they are open to multiple interpretations; and they don’t discuss many contemporary moral issues. Furthermore, the issue of abortion doesn’t arise in the Christian scriptures except tangentially. There are a few Biblical passages quoted by conservatives to support the anti-abortion position, the most well-known is in Jeremiah: “Before I formed you in the womb I knew you, and before you were born I consecrated you.” But, as anyone who has examined this passage knows, the sanctity of fetal life isn’t being discussed here. Rather, Jeremiah is asserting his authority as a prophet. This is a classic example of seeking support in holy books for a position you already hold.

Many other Biblical passages point to the more liberal view of abortion. Three times in the Bible (Genesis 38:24; Leviticus 21:9; Deuteronomy 22:20–21) the death penalty is recommended for women who have sex out-of-wedlock, even though killing the women would kill their fetuses. In Exodus 21 God prescribes death as the penalty for murder, whereas the penalty for causing a woman to miscarry is a fine. In the Old Testament the fetus doesn’t seem to have personhood status, and the New Testament says nothing about abortion at all. There simply isn’t a strong scriptural tradition in Christianity against abortion.

There also is no strong church tradition against abortion. It is true that the Catholic Church has held for centuries that activities like contraception and abortion which interrupt natural processes are immoral. Yet, while most pro-lifers don’t consider those distributing birth control to be murderers, the Catholic Church and others do take the extreme view that abortion is murder. Where does such a strong condemnation come from? The history of the Catholic view isn’t clear on the issue, but in the 13th century the philosopher Thomas Aquinas argued that the soul enters the body when the zygote has a human shape. Gradually other Christian theologians came to believe that the soul enters the body a few days after conception, although we don’t exactly know why they believed this. But, given what we now know about fetal development, if the Catholic Church’s position remained consistent with the views of Aquinas, they should say that the soul doesn’t enter the zygote for at least a month or two after conception. (Note also that there is no moment of conception, despite popular belief to the contrary.)

Thus the anti-abortion position doesn’t clearly follow from either scripture or church tradition. Instead what happens is that people already have moral views, and they then look to their religion for support. In other words, moral convictions aren’t usually derived from scripture or church tradition so much as superimposed on them. (For example, Christians used the Bible to both support and oppose slavery in the period before the American Civil War.) But even if the pro-life position did follow from a religious tradition, that would only be relevant for religious believers. For the rest of us, and for many religious believers too, the best way to adjudicate our disputes without resorting to violence is to conscientiously examine the arguments for and against moral propositions by shining the light of reason upon them.

It also clearly follows that religious believers have no right to impose their views upon the rest of us. We live in a morally pluralistic society where, informed by the ethos of the Enlightenment, we should reject attempts to impose theocracy. We should allow people to follow their conscience in moral matters—you can drink alcohol—as long as others aren’t harmed—you shouldn’t drink and drive. In philosophy of law, this is known as the harm principle. If rational argumentation supported the view that the zygote is a full person, then we might have reason to outlaw abortion, inasmuch as abortion would harm another person. (I say might because the fact that something is a person doesn’t necessarily imply that’s it wrong to kill it, as defenders of war, self-defense and capital punishment maintain.)

But for now the received view among ethicists is that the pro-life arguments fail, primarily because the fetus satisfies few if any of the necessary and sufficient conditions for personhood. The impartial view, backed by contemporary biology and philosophical argumentation, is that a zygote is a potential person. That doesn’t mean it has no moral significance, but it does mean that it has less significance than an actual person. An acorn may become an oak tree, but an oak tree it is not. You may believe that your God puts souls into newly fertilized eggs, thereby granting them full personhood, but that is a religious belief not grounded in science or philosophical ethics.

As for American politics and abortion, no doubt much of the anti-abortion rhetoric in American society comes from a punitive, puritanical desire to punish people for having sex. Moreover, many are hypocritical on the issue, simultaneously opposing abortion as well as the only proven ways of reducing it—good sex education and readily available birth control. As for many (if not most) politicians, their public opposition is hypocritical and self-interested. Generally they don’t care about the issue—they care about the power and wealth derived from politics—but they feign concern by throwing red meat to their constituencies. They use the issue as a ploy to garner support from the unsuspecting. These politicians may be pro-birth, but they aren’t generally pro-life, as evidenced by their opposition to policies that would support the things that children need most after birth like education, health-care, and economic opportunities. But what politicians and many ordinary people clearly don’t care about is whether their fanatical anti-abortion position is based in rational argumentation.

May 6, 2016

The Positive Effect of Nature on People

A colleague recently sent me a link to an article which claims that having nature in your surroundings extends life and increases happiness. The article titled, “Having a nice garden could save your life, study suggests,” notes the strong association between exposure to greenness and vegetation and lower mortality rates. Nature also has a positive effect on mental health according to the article. In addition, people living in places with beautiful natural scenery have better health as reported in “Scenery not just greenery has an impact on health.” For those in urban environments, getting as much nature in it as possible is beneficial too, according to the research.

A large part of what underlies all this is Attention Restoration Theory which “asserts that people concentrate better after spending time in nature, or even looking at scenes of nature.” Moreover, the researchers Atchley and Strayer argue in “Creativity in the Wild: Improving Creative Reasoning through Immersion in Natural Settings,” that creativity is positively affected also.

All of the seems reasonable, with the caveat that social science research is particularly provisional. But as anyone who has been fortunate to walk in the woods or feasted their gaze on mountains or oceans know, the beauty of nature restores and inspires.

May 2, 2016

Nicotine Gum for Depression and Anxiety

(Disclaimer – I’m not a medical doctor. For more info on these topics consult an M.D.)

I was thinking about a friend who quit smoking about 10 years ago with the help of nicotine gum. She eventually kicked the nicotine gum habit too, although she claimed that it was about as difficult to quit the gum as it was the cigarettes. She did notice that her ability to deal with anxiety was reduced after quitting the gum, and she also became more depressed. As a result, she has considered starting to chew gum again.

Her main arguments against chewing the gum are: 1) the cost of the gum; 2) the worry that will come with always having to make sure she has enough gum; 3) possible dental issues caused by the gum; and 4) the sense of failure she feels in not being able to live without this crutch. Moreover, there is no guarantee that the gum will minimize her anxiety or depression, although there is some reason to think it will.

The main argument for chewing the gum is the reduction in anxiety and depression. (There are good reasons to think nicotine can help.) The thing to remember about this benefit, if it occurs, is that it is substantial and multi-faceted. Not only would she feel better—because her anxiety and depression would be minimized at all times—but she would be able to participate in and better enjoy other things that would make her life go better, like social relationships and productive work. Moreover, this reduction in anxiety and depressive symptoms would have good consequences for her physical health. (This assumes there are no negative health risks from chewing small doses of nicotine. As best as I can determine, there are no health risks.) So nicotine gum might both minimize her negative symptoms and make it more likely that she participates in activities that help her symptoms. You don’t want to join a group or do productive work if you are anxious and depressed.

Now let’s consider her arguments against using the gum. If you can’t afford it, then you can’t buy the gum. In her case she can afford it, although the $60 or so a month is costly. The worry about having the gum readily available is a reasonable one, although it isn’t any different from worry about having any other kind of medicine with you. That is a small price to pay for a medicine that is effective. As for oral health, the evidence suggest it has no ill effects at least as far as I can tell.

The fourth argument is particularly interesting, but I think ultimately fallacious. There are many “crutches” people use to get by including but not limited to: alcohol, tobacco, food, sex, religion, therapy and exercise. We also depend on things for our well-being like air, water, medicine, and more. If something helps you live better and doesn’t hurt anyone else, why not utilize the help? In fact, given that our behavior affects others, we may be morally obligated to do what’s necessary to help ourselves so as to be in a better position to help others. So if someone tells me they need to take some medicine or other drugs to physically or psychologically function, or they need to go the therapist or to church or for a long jog, I say … go for it. I believe contrary views stem primarily from guilt or perfectionism.

In the end we were all thrown into this world without our consent. And we must live in a world about which ultimately we know very little. We don’t know what to believe or what we should do. All we can do, is do our best. So if nicotine gum helps you, or you think it might, it is probably worth the risk. In this context we might remember the words of the philosopher and psychologist William James, who was himself tormented by depression.

We stand on a mountain pass in the midst of whirling snow and blinding mist, through which we get glimpses now and then of paths which may be deceptive. If we stand still we shall be frozen to death. If we take the wrong road we may be dashed to pieces. We do not certainly know whether there is any right one. What must we do? ‘Be strong, and of good courage.’ Act for the best, hope for the best, and take what comes. If death ends all, we cannot meet death better.

April 28, 2016

Religious Belief Might Bring About the End of the World

I recently did a book review of Phil Torres‘ important new book The End: What Science and Religion Tell Us about the Apocalypse . Here is a sample of my effusive praise for the book:

. Here is a sample of my effusive praise for the book:

… Torres’ book is one of the most important ones recently published. It offers a fascinating study of the many real threats to our existence, provides multiple insights as to how we might avoid extinction, and it is carefully and conscientiously crafted. Perhaps what strikes me most about Torres’ book is how deeply it expresses his concern for the fate of conscious life, as well as his awareness of how tenuous consciousness is in the vast immensity of time and space. The author obviously loves life, and hates to see ignorance and superstition imperil it. He implores us to remember how the little light of consciousness that brightens this planet can be quickly extinguished—and that we will only be saved by reason and science.

This praise was ever so slightly mitigated by my concern that the “secular apocalypse can arrive independent of any belief in a religious eschatology … We might use nuclear or chemical weapons to kill each other because we are greedy, aggressive, racist, ideological, or territorial . . . [so]. . . consideration of biological, psychological, social, cultural and economic factors are also important in understanding how we might avoid oblivion.”

Torres replied with a powerful response that I’ll reprint in full:

I would agree that the book doesn’t adequately deal with apocalyptic scenarios brought about by phenomena that are “non-religious” in nature. In one of the appendices, I do mention how eschatological beliefs imbue and animate strictly-speaking “secular” ideologies, such as Nazism and Marxism. The point of the book, though, is to specifically focus on the potential connections between religion and existential risks — to show that these two topics are mutually relevant, and therefore that the secular community and the x-risks community ought to be speaking to each other. According to the Global Terrorism Index, religious terrorism is the leading motivator of terrorism today, and as I attempt to argue in a forthcoming Skeptic article, I think there are fairly robust reasons for thinking that apocalyptic terrorism — arguably the most dangerous kind — will actually increase in the future. (Several terrorism scholars that I’ve sent the paper to share my conclusion, as it happens!)

Furthermore, while human irrationality — the ultimate danger here — can take many forms, such as nationalism, radical anarchism, and so on, I take it that religion offers perhaps the most compelling instance of bad epistemology in the world today. It’s also an immensely pervasive social-cultural phenomenon that, according to Pew, is projected to grow this century. Reasons like this are why I focus on religion in particular. But the ultimate point here is a very, very good one: there most definitely are other phenomena that could nontrivially increase the probability of an existential risk. (Is North Korea motivated by religion? Arguably, yes, a “cult of personality.” But there’s a lot more to be said here about this ongoing, and possibly increasing, danger, that doesn’t immediately fit into the categories that I discuss.) As John mentions, we could be greedy, aggressive, racist, ideological, territorial, and so on. So the point is definitely understood, and further exploration should be a focus of future work! In the last chapter of the book, I note that there are few shoulders upon which to stand when it comes to x-risks studies, simply because the field is a mere 20 years old, at most (in my estimation; starting with John Leslie’s The End of the World: The Science and Ethics of Human Extinction

. Once the field emerges a bit more from a “pre-paradigmatic” state, perhaps a more comprehensive analysis can be given.

. Once the field emerges a bit more from a “pre-paradigmatic” state, perhaps a more comprehensive analysis can be given.In conclusion let me reiterate that Torres’ book is extraordinarily important.

April 24, 2016

More Reflections on the Meaningful Life

Comments from a colleague solicited a recent blog post “Do We Make Our Lives Meaningful By How We Live Them?” In that post I reached this tentative conclusion:

… Not only do we live best by doing our duty and then recognizing that the outcome is out of our control, but we should remember that meaningful lives are those in which we are actively engaged as subjects in objectively projects—helping people, trying to achieve inner peace, pursuing the good, true, beautiful, etc. From an external perspective good results—people really being helped, more peace, truth, goodness, and beauty in the world—is an added bonus. So I now think … meaningful living is mostly about something inside of us … Still our lives are made even more meaningful to the extent that we affect the world for the better.

I still agree with the above, but further discussions with my colleague have helped understand the situation more clearly. Since we don’t know whether or lives are subjectively or objectively meaningful or meaningless, let’s put that issue aside. The main issues are: 1) whether meaning emanates primarily from our intentions, or from achieving our goals; 2) our actions are directed toward ourselves or others; and 3) whether meaning emanates primarily from a moral life rather or immoral one. In that case there are 8 possibilities:

1 – focus on intention, self-directed, immoral – Example – I intend to live the life of a self torturer, and my life is meaningful independent of whether or not I’m successful.

2 – focus on intention, self-directed, moral – Example – I intend to be a good monk, and my life is meaningful independent of whether or not I’m successful.

3 – focus on intention, other-directed, immoral – Example – I intend to live the life in which I torture others, and my life is meaningful independent of whether or not I’m successful.

4 – focus on intention, other-directed, moral – Example – I intend to help other people, and my life is meaningful independent of whether or not I’m successful.

5 – focus on consequences, self-directed, immoral – Example – I want to achieve my goal of being a self torturer, and my life is meaningful if I’m successful.

6 – focus on consequences, self-directed, moral – Example – I want to achieve my goal of being a good monk, and my life is meaningful if I’m successful.

7 – focus on consequences, other-directed, immoral – Example – I want to achieve my goal of torturing others, and my life is meaningful if I’m successful.

8 -focus on consequences, other-directed, moral – Example – I want to achieve my goal of helping other people and my life is meaningful if I’m successful.

Most of us would say that lives 2, 4, 6, & 8 are more meaningful than the other ones because they are moral lives. It seems morality has something to do with meaning. It is hard to say whether self or other directed lives are more important or whether intention or consequences or more important. Perhaps we need to attend both to our own development as well as other people and, at the same time, recognize that we might fail in both endeavors. So I still do believe that meaningful lives are both those that try to transform the self and, in the process, hopefully transform reality.

April 20, 2016

Is The Singularity A Religious Doctrine?

A colleague forwarded John Horgan‘s recent Scientific American article, “The Singularity and the Neural Code.” Horgan argues that the intelligence augmentation and mind uploading that would lead to a technological singularity depend upon cracking the neural code. The problem is that we don’t understand our neural code, the software or algorithms that transform neurophysiology into the stuff of minds like perceptions, memories, and meanings. In other words, we know very little about how brains make minds.

The neural code is science’s deepest, most consequential problem. If researchers crack the code, they might solve such ancient philosophical conundrums as the mind-body problem and the riddle of free will. A solution to the neural code could also, in principle, give us unlimited power over our brains and hence minds. Science fiction—including mind-control, mind-reading, bionic enhancement and even psychic uploading—could become reality. But the most profound problem in science is also by far the hardest.

But it does appear “that each individual psyche is fundamentally irreducible, unpredictable, inexplicable,” which that suggests that it would be exceedingly difficult to extract that uniqueness from a brain and transfer it to another medium. Such considerations lead Horgan to conclude that, “The Singularity is a religious rather than a scientific vision … a kind of rapture for nerds …” As such it is one of many “escapist, pseudoscientific fantasies …”

I don’t agree with Horgan’s conclusion. He believes that belief in technological or religious immortality springs from a “yearning for transcendence,” which suggests that what is longed for is pseudoscientific fantasy. But the fact that a belief results from a yearning doesn’t mean the belief is false. I can want things to be true that turn out to be true.

More importantly, I think Horgan mistakenly conflates religious and technological notions of immortality, thereby denigrating ideas of technological immortality by association. But religious beliefs about immortality are based exclusively on yearning without any evidence of their truth. In fact, every moment of every day the evidence points away from the truth of religious immortality. We don’t talk to the dead and they don’t talk to us. On the other hand, technological immortality is based on scientific possibilities. The article admits as much, since cracking the neural code may lead to technological immortality. So while both types of immorality may be based on a longing or yearning, only one has the advantage of being based on science.

Thus the idea of a technological singularity is for the moment science fiction, but it is not pseudoscientific. Undoubtedly there are other ways to prioritize scientific research, and perhaps trying to bring about the Singularity isn’t a top priority. But it doesn’t follow from anything that Horgan says that we should abandon trying to crack the neural code, or to the Singularity that might lead to. Doing so may solve most of our other problems, and usher in the Singularity too.