John G. Messerly's Blog, page 89

September 19, 2016

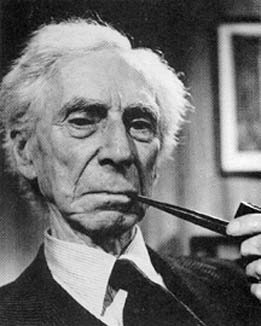

Bertrand Russell: The Value of Philosophy

Readers of this blog know that Bertrand Russell is one of my intellectual heroes. I believe that Russell was the greatest philosopher in the twentieth century and quite possibly the greatest philosopher of the entire Western intellectual tradition. (You can find a brief introduction to some of his many contributions to philosophy here.)

For many years I introduced philosophy in my college classes by discussing its value. One of the most beautiful statements on that topic is from Russell’s classic, The Problems of Philosophy[image error]. I know of no more beautiful statement of the value of philosophy than this. It deserves a careful and conscientious reading.

The value of philosophy is, in fact, to be sought largely in its very uncertainty. The man who has no tincture of philosophy goes through life imprisoned in the prejudices derived from common sense, from the habitual beliefs of his age or his nation, and from convictions which have grown up in his mind without the co-operation or consent of his deliberate reason. To such a man the world tends to become definite, finite, obvious; common objects rouse no questions, and unfamiliar possibilities are contemptuously rejected. As soon as we begin to philosophize, on the contrary, we find, as we saw in our opening chapters, that even the most everyday things lead to problems to which only very incomplete answers can be given. Philosophy, though unable to tell us with certainty what is the true answer to the doubts which it raises, is able to suggest many possibilities which enlarge our thoughts and free them from the tyranny of custom. Thus, while diminishing our feeling of certainty as to what things are, it greatly increases our knowledge as to what they may be; it removes the somewhat arrogant dogmatism of those who have never travelled into the region of liberating doubt, and it keeps alive our sense of wonder by showing familiar things in an unfamiliar aspect.

Apart from its utility in showing unsuspected possibilities, philosophy has a value — perhaps its chief value — through the greatness of the objects which it contemplates, and the freedom from narrow and personal aims resulting from this contemplation. The life of the instinctive man is shut up within the circle of his private interests: family and friends may be included, but the outer world is not regarded except as it may help or hinder what comes within the circle of instinctive wishes. In such a life there is something feverish and confined, in comparison with which the philosophic life is calm and free. The private world of instinctive interests is a small one, set in the midst of a great and powerful world which must, sooner or later, lay our private world in ruins. Unless we can so enlarge our interests as to include the whole outer world, we remain like a garrison in a beleagured fortress, knowing that the enemy prevents escape and that ultimate surrender is inevitable. In such a life there is no peace, but a constant strife between the insistence of desire and the powerlessness of will. In one way or another, if our life is to be great and free, we must escape this prison and this strife.

One way of escape is by philosophic contemplation. Philosophic contemplation does not, in its widest survey, divide the universe into two hostile camps — friends and foes, helpful and hostile, good and bad — it views the whole impartially. Philosophic contemplation, when it is unalloyed, does not aim at proving that the rest of the universe is akin to man. All acquisition of knowledge is an enlargement of the Self, but this enlargement is best attained when it is not directly sought. It is obtained when the desire for knowledge is alone operative, by a study which does not wish in advance that its objects should have this or that character, but adapts the Self to the characters which it finds in its objects. This enlargement of Self is not obtained when, taking the Self as it is, we try to show that the world is so similar to this Self that knowledge of it is possible without any admission of what seems alien. The desire to prove this is a form of self-assertion and, like all self-assertion, it is an obstacle to the growth of Self which it desires, and of which the Self knows that it is capable. Self-assertion, in philosophic speculation as elsewhere, views the world as a means to its own ends; thus it makes the world of less account than Self, and the Self sets bounds to the greatness of its goods. In contemplation, on the contrary, we start from the not-Self, and through its greatness the boundaries of Self are enlarged; through the infinity of the universe the mind which contemplates it achieves some share in infinity.

For this reason greatness of soul is not fostered by those philosophies which assimilate the universe to Man. Knowledge is a form of union of Self and not-Self; like all union, it is impaired by dominion, and therefore by any attempt to force the universe into conformity with what we find in ourselves. There is a widespread philosophical tendency towards the view which tells us that Man is the measure of all things, that truth is man-made, that space and time and the world of universals are properties of the mind, and that, if there be anything not created by the mind, it is unknowable and of no account for us. This view, if our previous discussions were correct, is untrue; but in addition to being untrue, it has the effect of robbing philosophic contemplation of all that gives it value, since it fetters contemplation to Self. What it calls knowledge is not a union with the not-Self, but a set of prejudices, habits, and desires, making an impenetrable veil between us and the world beyond. The man who finds pleasure in such a theory of knowledge is like the man who never leaves the domestic circle for fear his word might not be law.

The true philosophic contemplation, on the contrary, finds its satisfaction in every enlargement of the not-Self, in everything that magnifies the objects contemplated, and thereby the subject contemplating. Everything, in contemplation, that is personal or private, everything that depends upon habit, self-interest, or desire, distorts the object, and hence impairs the union which the intellect seeks. By thus making a barrier between subject and object, such personal and private things become a prison to the intellect. The free intellect will see as God might see, without a here and now, without hopes and fears, without the trammels of customary beliefs and traditional prejudices, calmly, dispassionately, in the sole and exclusive desire of knowledge — knowledge as impersonal, as purely contemplative, as it is possible for man to attain. Hence also the free intellect will value more the abstract and universal knowledge into which the accidents of private history do not enter, than the knowledge brought by the senses, and dependent, as such knowledge must be, upon an exclusive and personal point of view and a body whose sense-organs distort as much as they reveal.

The mind which has become accustomed to the freedom and impartiality of philosophic contemplation will preserve something of the same freedom and impartiality in the world of action and emotion. It will view its purposes and desires as parts of the whole, with the absence of insistence that results from seeing them as infinitesimal fragments in a world of which all the rest is unaffected by any one man’s deeds. The impartiality which, in contemplation, is the unalloyed desire for truth, is the very same quality of mind which, in action, is justice, and in emotion is that universal love which can be given to all, and not only to those who are judged useful or admirable. Thus contemplation enlarges not only the objects of our thoughts, but also the objects of our actions and our affections: it makes us citizens of the universe, not only of one walled city at war with all the rest. In this citizenship of the universe consists man’s true freedom, and his liberation from the thraldom of narrow hopes and fears.

Thus, to sum up our discussion of the value of philosophy; Philosophy is to be studied, not for the sake of any definite answers to its questions since no definite answers can, as a rule, be known to be true, but rather for the sake of the questions themselves; because these questions enlarge our conception of what is possible, enrich our intellectual imagination and diminish the dogmatic assurance which closes the mind against speculation; but above all because, through the greatness of the universe which philosophy contemplates, the mind also is rendered great, and becomes capable of that union with the universe which constitutes its highest good.

September 12, 2016

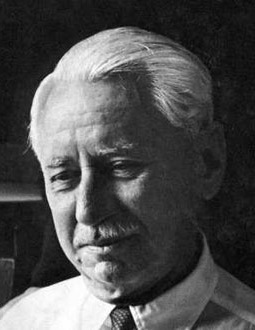

Will Durant: The Value of Philosophy

Readers of this blog know that Will Durant is one of my intellectual heroes.

William James “Will” Durant (/dəˈrænt/; November 5, 1885 – November 7, 1981) was an American writer, historian, and philosopher. He is best known for The Story of Civilization, 11 volumes written in collaboration with his wife, Ariel Durant, and published between 1935 and 1975. He was earlier noted for The Story of Philosophy (1926), described as “a groundbreaking work that helped to popularize philosophy”.[1] … The Durants were awarded the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction in 1968 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977. (from Wikipedia)

For many years I introduced philosophy in my college classes by discussing the value of philosophy. One of the most beautiful statements on that topic is from the introduction to Durant’s Pleasures of Philosophy[image error], a book I encountered in my late teens. Here is Durant’s beautiful prose:

The busy reader will ask, is all this philosophy useful? It is a shameful question: we do not ask it of poetry, which is also an imaginative construction of a world incompletely known. If poetry reveals to us the beauty our untaught eyes have missed and philosophy gives us the wisdom to understand and forgive, it is enough, and more than the world’s wealth. Philosophy will not fatten our purses nor lift us to dizzy dignities in a democratic state; it may even make us a little careless of these things. For what if we should fatten our purses, or rise to high office and yet all the while remain ignorantly naive, coarsely unfurnished in the mind, brutal in behavior, unstable in character, chaotic in desire and blindly miserable? …

Our culture is superficial today and our knowledge dangerous, because we are rich in mechanism and poor in purposes. the balance of mind which once came of a warm religious faith is gone; science has taken from us the supernatural bases of our morality and all the world seems consumed in a disorderly individualism that reflects the chaotic fragmentation of our character.

We face again the problem that harassed Socrates: how shall we find a natural ethic to replace the supernatural sanctions that have ceased to influence the behavior of men? Without philosophy, without that total vision which unifies purposes and establishes the hierarchy of desires we fritter away our social heritage in cynical corruption on the one hand and in revolutionary madness on the other; we abandon in a moment our idealism and plunge into the cooperative suicide of war; we have a hundred thousand politicians, and not a single statesman.

We move about the earth with unprecedented speed, but we do not know, and have not thought where we are going, or whether we shall find any happiness there for our harrassed souls. We are being destroyed by our knowledge which has made us drunk with our power, and we shall not be saved without wisdom.

I know no better statement of the value of loving wisdom.

September 5, 2016

Who Owns the Media? An Infographic

The following infographic created by Jason at Frugal Dad shows that almost all media that citizens of the United States are exposed to comes from the same six sources. And when a few of the world’s wealthiest corporations control all of the news and commentary, only limited political perspectives will be disseminated. The United States, according to the 2016 World Press Freedom Report Index of Reporters Without Borders, ranks as only the 41st freest press in the world. The US ranks behind Namibia, Surinam, Tonga, and Slovenia and just ahead of Botswana, Niger, Romania, and Haiti. Here is the infographic:

August 29, 2016

Longfellow’s “Morituri Salutamas” – A Poem About Old Age

In 1875, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807 – 1882) accepted an offer from the American Civil War hero Joshua Chamberlain to speak at his fiftieth reunion at Bowdoin College, Longfellow’s alma mater. There he read his poem “Morituri Salutamus.” (“We who are about to die, salute you.”) The poem begins with a Latin quote by the Roman poet Ovid which reads: “Tempora labuntur, tacitisque senescimus annis, Et fugiunt freno non remorante dies.” (“The times slip away, and we grow old with silent years, and the days flee unchecked by a rein.”)

The poem expresses his belief that while we cannot stop the inexorable march of time, we can mitigate its effects by learning as we pass through life—for maturity allows for insights unachievable in youth. He also voices his belief that there is much left to do in old age. And while many have criticized the simplicity of Longfellow’s simple rhymes, I find them comforting. It is true that most of us won’t do our best work in old age, but perhaps if we have learned something in life we will be the better people later in life.

Wadsworth ends the poem by exhorting his fellows to continue to work and dream even as they advanced in age. Here are its final stanzas:

But why, you ask me, should this tale be told

To men grown old, or who are growing old?

It is too late! Ah, nothing is too late

Till the tired heart shall cease to palpitate.

Cato learned Greek at eighty; Sophocles

Wrote his grand Oedipus, and Simonides

Bore off the prize of verse from his compeers,

When each had numbered more than fourscore years,

And Theophrastus, at fourscore and ten,

Had but begun his “Characters of Men.”

Chaucer, at Woodstock with the nightingales,

At sixty wrote the Canterbury Tales;

Goethe at Weimar, toiling to the last,

Completed Faust when eighty years were past.

These are indeed exceptions; but they show

How far the gulf-stream of our youth may flow

Into the arctic regions of our lives,

Where little else than life itself survives.

As the barometer foretells the storm

While still the skies are clear, the weather warm

So something in us, as old age draws near,

Betrays the pressure of the atmosphere.

The nimble mercury, ere we are aware,

Descends the elastic ladder of the air;

The telltale blood in artery and vein

Sinks from its higher levels in the brain;

Whatever poet, orator, or sage

May say of it, old age is still old age.

It is the waning, not the crescent moon;

The dusk of evening, not the blaze of noon;

It is not strength, but weakness; not desire,

But its surcease; not the fierce heat of fire,

The burning and consuming element,

But that of ashes and of embers spent,

In which some living sparks we still discern,

Enough to warm, but not enough to burn.

What then? Shall we sit idly down and say

The night hath come; it is no longer day?

The night hath not yet come; we are not quite

Cut off from labor by the failing light;

Something remains for us to do or dare;

Even the oldest tree some fruit may bear;

Not Oedipus Coloneus, or Greek Ode,

Or tales of pilgrims that one morning rode

Out of the gateway of the Tabard Inn,

But other something, would we but begin;

For age is opportunity no less

Than youth itself, though in another dress,

And as the evening twilight fades away

The sky is filled with stars, invisible by day.

August 22, 2016

The “Transcension Hypothesis” and the “Fermi Paradox”

John Smart, a colleague of mine in the Evolution, Cognition and Complexity Group, has advanced the transcension hypothesis. In Smart’s words:

The transcension hypothesis proposes that a universal process of evolutionary development guides all sufficiently advanced civilizations into what may be called “inner space,” a computationally optimal domain of increasingly dense, productive, miniaturized, and efficient scales of space, time, energy, and matter, and eventually, to a black-hole-like destination.

An important implications of the transcension hypothesis is as a possible explanation for the Fermi paradox—the apparent contradiction between the lack of evidence for the existence of extraterrestrials along with high probability estimates given for their existence by the Drake equation. (I have previously written about the Fermi paradox here and here.)

What all of this means is that rather than exploring the outer space of the universe, advanced civilization explore their inner space and eventually disappear from our view. And this is why the SETI Institute hasn’t found evidence of extraterrestrial intelligence. This two-minute video explains this clearly.

While the transcension hypothesis is speculative, it is also quite reasonable. The primary metaphysical implications of the hypothesis is that, if true, there is more to reality than we know, which opens the door to their being better realities than the one in which we currently reside. Perhaps our descendants will escape to such realities and somehow bring us along, maybe by running ancestor simulation? Who knows. But one thing we can say for sure; much is hidden from our ape-like minds, and this should cause us to be humble.

August 15, 2016

This election isn’t just Democrat vs. Republican. It’s normal vs. abnormal.

The above video from Ezra Klein is so clear and cogent that it deserves to be watched by anyone who desires not to be a low information voter. It perfectly expresses my own view. (You can view the video and is the entire transcript here: “This election isn’t just Democrat vs. Republican. It’s normal vs. abnormal.”

There is a lot to say about what has happened to the Republican party that an unfit, unqualified, and unhinged candidate is their nominee. And I understand how Republicans might still want to be team players, or believe it is their self-interest to support Trump. After all it is hard to change teams. Klein’s rejoinder to this line of thinking is perceptive:

But this is a dangerous game. We are a nation protected by norms, not just by laws. Our political parties should be held to certain standards in terms of the candidates they nominate, the behaviors they accept, the ideas they mainstream. Trump violates those standards. By indulging him, the Republican Party is normalizing him and his behavior, and making itself abnormal.

I would only add that the Republican party violated these norms even before Trump. For example, it is normal to allow sitting Presidents to nominate judges, but it is not normal to not fill the judiciary, shut down the government or threaten the world economy to get your way. The Republican party and their propagandists at Fox News and on conservative radio play a dangerous game by helping to unravel social stability. This may be in their short-term interest, but it is self-defeating in the long run. For the rich and powerful benefit the most from social stability.

August 8, 2016

Longfellow’s “A Psalm of Life” – A Poem About the Passage of Time

[image error]

The passage of time steals our youth, our vitality, and any permanence that we might hope for. How best to respond to our situation? Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) tried to answer this question in 1838 in his poem “A Psalm of Life.” They contain some of my favorite lines of poetry.

Tell me not, in mournful numbers,

Life is but an empty dream!

For the soul is dead that slumbers,

And things are not what they seem.

Life is real! Life is earnest!

And the grave is not its goal;

Dust thou art, to dust returnest,

Was not spoken of the soul.

Not enjoyment, and not sorrow,

Is our destined end or way;

But to act, that each to-morrow

Find us farther than to-day.

Art is long, and Time is fleeting,

And our hearts, though stout and brave,

Still, like muffled drums, are beating

Funeral marches to the grave.

In the world’s broad field of battle,

In the bivouac of Life,

Be not like dumb, driven cattle!

Be a hero in the strife!

Trust no Future, howe’er pleasant!

Let the dead Past bury its dead!

Act,— act in the living Present!

Heart within, and God o’erhead!

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time;

Footprints, that perhaps another,

Sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, shall take heart again.

Let us, then, be up and doing,

With a heart for any fate;

Still achieving, still pursuing,

Learn to labor and to wait.

Epilogue – Still, as I have argued in my recent book on the meaning of life, the wisdom that may come with age makes death even more tragic. The wisdom which took so much time and effort to achieve vanishes with our passing, since it is mostly ineffable—incapable of being transmitted to the young. They have to learn it on their own … as they age.

So for now, until we have eliminated death, the passage of time drives us inexorably toward our end. And this is a reason to lament our fate … and battle to defeat it.

August 1, 2016

Summary of Ken Burns 2016 Anti-Trump Commencement Speech at Stanford

Filmmaker Ken Burns delivers the 2016 Commencement address at Stanford.

(Image credit: L.A. Cicero – The full text can be found here.)

“Ken” Burns[1] is an American filmmaker, known for his style of using archival footage and photographs in documentary films. His most widely known documentaries are The Civil War (1990), Baseball (1994), Jazz (2001), The War (2007), The National Parks: America’s Best Idea (2009), Prohibition (2011), The Central Park Five (2012), and The Roosevelts (2014). Also widely known is his role as executive producer of The West … and Cancer: The Emperor of All Maladies ….[2] (from Wikipedia)

Summary

Objectivity About History – Burns begins by stating that he is “in the business of memorializing … history.” He reminds people of the power the past exerts on us, and how it helps us better understand the present. He also says that for “nearly 40 years now, I have diligently practiced and rigorously maintained a conscious neutrality in my work, avoiding the advocacy of many of my colleagues, trying to speak to all of my fellow citizens.” (In other words, he has tried to tell both sides of the story as impartially as possible.)

Inspiration From The Past – As we look back over the past Burns asks where we should look for inspiration. “Which distant events and long dead figures will provide us with the greatest help, the most coherent context and the wisdom to go forward?” Why is this important? Because:

The hard times and vicissitudes of life will ultimately visit everyone. You will also come to realize that you are less defined by the good things that happen to you, your moments of happiness and apparent control, than you are by those misfortunes and unexpected challenges that, in fact, shape you more definitively, and help to solidify your true character—the measure of any human value.

Burns vividly recalls finding out at age 8 that his mother was dying of cancer. She was not crying about her impending death, but about how her illness was bankrupting her family. Fortunately her neighbors’ small donations kept the family solvent, and Burns learned about how life’s struggles can be ameliorated with small victories. In his filmmaking career he has tried “to resurrect small moments within the larger sweep of American history, trying to find our better angels in the most difficult of circumstances, trying to wake the dead, to hear their stories.”

Meaning From The Past – But how do we overcome the fear of death? How do we find meaning in life if we all die? History helps us answer these questions.

The past often offers an illuminating and clear-headed perspective from which to observe and reconcile the passions of the present moment, just when they threaten to overwhelm us. The history we know, the stories we tell ourselves, relieve that existential anxiety, allow us to live beyond our fleeting lifespans, and permit us to value and love and distinguish what is important.

The United States Government – Burns himself finds particular inspiration from Abraham Lincoln. In 1858, while speaking his colleagues in the new Republican party about slavery, he uttered these words: “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” But within a few years he was president of a divided nation and, in his Annual Message to Congress, he asked us to rise to the occasion.

Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history. … The fiery trial through which we pass will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation. We say we are for Union. … We know how to save the Union. … In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free—honorable alike in what we give, and what we preserve. We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth.

Burns points out that Lincoln is speaking to us, we must rise to the occasion and save the country. He also rejects cynicism about our government even though it has made “catastrophic mistakes.” In fact the lives we live are made possible, to a large extent, by our government.

From our Declaration of Independence to our Constitution and Bill of Rights; from Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments to the Land Grant College and Homestead Acts; from the transcontinental railroad and our national parks to child labor laws, Social Security and the National Labor Relations Act; from the GI Bill and the interstate highway system to putting a man on the moon and the Affordable Care Act, the United States government has been the author of many of the best aspects of our public and personal lives.

Individualism – We forget how much government gives us “because we live in an age of social media where we are constantly assured that we are all independent free agents.” We don’t see our connection to the entire community because of:

a sophisticated media culture that … desperately needs you – to live in an all-consuming disposable present, wearing the right blue jeans, driving the right car, carrying the right handbag, eating at all the right places, blissfully unaware of the historical tides that have brought us to this moment, blissfully uninterested in where those tides might take us.

Our false individualism makes us feel important “but this kind of existence actually ingrains in us a stultifying sameness that rewards conformity (not courage), ignorance and anti-intellectualism (not critical thinking).” And now such ignorance threatens our political future. ” And there comes a time when I—and you—an no longer remain neutral, silent. We must speak up – and speak out.”

The Unique Danger of Donald Trump – Here is best to quote a man who knows so much of American history, Burns himself:

For 216 years, our elections, though bitterly contested, have featured the philosophies and character of candidates who were clearly qualified. That is not the case this year. One is glaringly not qualified. So before you do anything with your well-earned degree, you must do everything you can to defeat the retrograde forces that have invaded our democratic process, divided our house, to fight against, no matter your political persuasion, the dictatorial tendencies of the candidate with zero experience in the much maligned but subtle art of governance; who is against lots of things, but doesn’t seem to be for anything, offering only bombastic and contradictory promises, and terrifying Orwellian statements; a person who easily lies, creating an environment where the truth doesn’t seem to matter; who has never demonstrated any interest in anyone or anything but himself and his own enrichment; who insults veterans, threatens a free press, mocks the handicapped, denigrates women, immigrants and all Muslims; a man who took more than a day to remember to disavow a supporter who advocates white supremacy and the Ku Klux Klan; an infantile, bullying man who, depending on his mood, is willing to discard old and established alliances, treaties and long-standing relationships. I feel genuine sorrow for the understandably scared and—they feel—powerless people who have flocked to his campaign in the mistaken belief that—as often happens on TV—a wand can be waved and every complicated problem can be solved with the simplest of solutions. They can’t. It is a political Ponzi scheme. And asking this man to assume the highest office in the land would be like asking a newly minted car driver to fly a 747.

Burns has seen this type of figure arise many times and many places in history.

an incipient proto-fascism, a nativist anti-immigrant Know Nothing-ism, a disrespect for the judiciary, the prospect of women losing authority over their own bodies, African-Americans again asked to go to the back of the line, voter suppression gleefully promoted, jingoistic saber-rattling, a total lack of historical awareness, a political paranoia that, predictably, points fingers, always making the other wrong. These are all virulent strains that have at times infected us in the past. But they now loom in front of us again – all happening at once. We know from our history books that these are the diseases of ancient and now fallen empires. The sense of commonwealth, of shared sacrifice, of trust, so much a part of American life, is eroding fast, spurred along and amplified by an amoral Internet that permits a lie to circle the globe three times before the truth can get started.

Burns does decry that the media has not exposed this charlatan, primarily because he delivers good ratings. “In fact, they have given him the abundant airtime he so desperately craves, so much so that it has actually worn down our natural human revulsion to this kind of behavior.” As Burns notes, “This is not a liberal or conservative issue, a red state, blue state divide. This is an American issue. Many honorable people, including the last two Republican presidents, members of the party of Abraham Lincoln, have declined to support him.” And he implores those Republicans” who have endorsed him to reconsider. “We must remain committed to the kindness and community that are the hallmarks of civilization and reject the troubling, unfiltered Tourette’s of his tribalism.”

Burns concludes this section of his speech by saying to these graduates of one of the most prestigious universities in the world:

The next few months of your “commencement,” that is to say, your future, will be critical to the survival of our Republic. “The occasion is piled high with difficulty.” Let us pledge here today that we will not let this happen to the exquisite, yet deeply flawed, land we all love and cherish—and hope to leave intact to our posterity. Let us “nobly save,” not “meanly lose, the last best hope of earth.”

Fatherly Advice – He finishes by offering some advice. Take it seriously when someone tells you they’ve been sexually assaulted; be for things not just against things; be curious; feed your mind; remember that insecurity makes liars of us all; don’t confuse success with excellence; don’t overspecialize, be generally educated; think beyond the binary; seek out mentors; embrace new ideas; travel; read; have children, you will learn much; be enthusiastic; remember the great threats to your country come from within; support science and the arts; vote; and

Believe, as Arthur Miller told me in an interview for my very first film on the Brooklyn Bridge, “believe, that maybe you too could add something that would last and be beautiful.”

What a wonderful speech. Thank you Ken Burns.

July 25, 2016

The Movie “Spotlight”: Philosophical Reflections

Last night I watched “Spotlight,” one of the finest films I’ve seen in years.

The film follows The Boston Globe‘s “Spotlight” team, the oldest continuously operating newspaper investigative journalist unit in the United States,[6] and its investigation into cases of widespread and systemic child sex abuse in the Boston area by numerous Roman Catholic priests. It is based on a series of stories by the “Spotlight” team that earned The Globe the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service.[7] … The film … was named one of the finest films of 2015 by various publications. Spotlight won the Academy Award for Best Picture along with Best Original Screenplay … (from Wikipedia)

I am no expert on pedophilia and there is no consensus about its causes even among experts. However, pedophilia does not appear more prevalent among Catholic clergy than among other professions. The best estimates are that about 4% of the general population are pedophiles and between 90 and 99% of these are men. This is consistent with “the best available data … [that] 4% of Catholic priests in the USA sexually victimized minors during the past half century.”

Still, we recoil when abuse is perpetrated by those who claim to be moral exemplars. Many expect the mafia or military to be violent and corrupt, but not the clergy. But it doesn’t take much life experience to learn that hypocrisy is a defining trait of human beings. If someone boasts about his moral character, it’s a good bet that he is a scoundrel. As for the subsequent cover up, churches, governments, businesses, political parties and individuals usually try to hide their misdeeds, even if others are hurt in the process. This is a near truism of human life.

Another thing that struck me was how costly and difficult it is to do investigative reporting. It really takes a lot of work to uncover corruption, and the supposed purveyors of decency do their best to keep their hypocrisy from being illuminated. Thus it is easy to understand attacks on the media by the rich and powerful, inasmuch as they know that a really free press is one of the only constraints on their power.

In response, a few of the most powerful have simply bought the media. Most people don’t realize that 90% of all the media in the United States is owned by one of 6 corporations. “With the country’s widest disseminators of news, commentary, and ideas firmly entrenched among a small number of the world’s wealthiest corporations, it may not be surprising that their news and commentary is limited to an unrepresentative narrow spectrum of politics.” – (Ben Bagdikian, former dean of the School of Journalism at UC-Berkeley)

Given this state of affairs the spotlight investigative team deserves our unending praise for uncovering just a small bit of the corruption that surrounds us. I thank them for reminding me once again that a defining trait of most human beings is hypocrisy.

July 18, 2016

Skepticism and the Meaning of Life

I received a correspondence from a reader who wonders about “the triumph of judgment over spontaneity as we emerge from childhood into adulthood and the consequent obstacle it poses for living in psychic comfort.” In other words she worries about how to reconcile “a naturally felt purposefulness and zest for life against an intellectual sense of life’s essential pointlessness and its indifference to human concerns that give rise to the recognition of absurdity.” The only consolation she experiences is with her grandchildren “as they go about engaging the world with perfect unmediated wonder, boundless energy, and demands for attention.”

I too have felt this tension. When I watch the delight my young granddaughter takes in looking at every flower and insect, when I sense the innocent eyes through which she sees the world, I am saddened beyond words. Like any adult I know the ugliness of the world that waits to trample on that innocence. I clearly see the contrast between childlike wonder and the pessimistic conclusions about the nature of reality that mature reasoners often draw. Given this tension, how do we carry on without accepting some silly supernaturalism?

There are a number of strategies we might adopt here. We might follow Victor Frankl (Man’s Search for Meaning) and conclude that the problem of life is not learning to live with its absurdity—since we can’t know for sure that it is absurd—but to learn to live not being sure if life is meaningful or not. Or we might follow a philosopher like E. D. Klemke’s (Summary of E.D. Klemke’s “Living Without Appeal“) who held that we can find subjective meaning in an objectively meaningless world by responding positively to its beauty. As Klemke put it: “if I can so respond and can thereby transform an external and fatal event into a moment of conscious insight and significance, then I shall go down without hope or appeal yet passionately triumphant and with joy.”

Still I agree with my reader that no amount of intellectual reflection ever fully dispels our deepest existential concerns. For the movement of time spoils even those things that make us happy and which, for the moment, give our lives purpose. This passage of time haunts us; that perpetual perishing which diminishes our joy by its intrusion into the present. This radical impermanence, and our consciousness of it, reminds us that our own demise rushes toward us as the present recedes away. The awareness of our impending doom is a constant companion capable of poisoning our momentary happiness, leading in turn to the inevitable realization that it not just we who may die, but our children, and their children, and all children, and, in the end, all of reality as well.

Reaching the limits of the intellect’s power to dissuade our existential fears, perhaps we can be comforted by an exuberant affirmation of the meaning found in life’s activities. Any serious student of philosophy is struck by the stark contrast between the somber tone of our philosophical musings, and the joy we feel through our immersion in the world of the senses. In the mountains and oceans we see, in the walks we take and the meals we eat, in the joy we find in physical play and philosophical talk, and in the warmth we feel when surrounded by those that love us and whom we love, there we don’t so much find meaning as transcend the need for it. At those times life is sufficient unto itself. When we laugh and play and love, all the misery of the world momentarily vanishes. We hardly give meaning a thought. And if thought brings existential anguish back again—perhaps we can and should think less. In short, we live deeper than we can think.

But is living with less thinking a realistic antidote? Can we live this way after reflectivity has become interwoven into our natures? Can we live constantly in motion, so that troubling thoughts do not disturb? No, we cannot suppress our most important questions indefinitely. For after laughing and playing and loving, thought returns. Why is happiness so fleeting? Why must we suffer and die? Why do we all meet tragic ends? What if all is for naught? We cannot avoid our questions for long; eventually we drop our guard and they return.

But even if we could avoid our deepest questions, should we? I don’t think so. Our questions bring forth the deep reservoir of our inner life that is often hidden from normal viewing, and our curiosity and inquisitiveness ennoble us, differentiating us from less conscious beings. Our thinking may not make us happy, but it nourishes a deep interior life. However much we love the world of body and sense, thought is our salient feature. We should not repress it. And, since we cannot and should not evade our questions, the prescription to find meaning in activity only partially satisfies. No matter what we think or do, our questions remain.

Nothing then completely silences all our doubts and soothes all our worries—not the limited meaning life offers us, not the knowledge of a purpose, not the promise of hope, not the engagement in activity. How then do we proceed? We must accept something of our present life lest resentment cause us to curse it. Yet, at the same time, we must reject the present or nothing will improve. This creative tension acknowledges the limitations of reality as a starting point while rebelling against its shortcomings. It involves working to mold, create, and increase meaning. We don’t know that reality will progress, but if we partially accept our present reality, if we dream of a future without limits and struggle to bring it about, we may increase the meaning in our lives and in the world.

Yet for now we are forced to live with uncertainty and angst, as a testimony to our intellectual honesty and emotional integrity. Unlike those who adopt blind faith, we scorn the facile resolutions of the cowardly. And if we must die, we will die as free people who did not yield to the forces that sought to destroy them from the moment of their birth. Those are the forces we seek to defeat, but which have not yet been defeated. In the meantime, we should relish the limited joy and meaning life offers, work to eliminate human limitations, and suppress negative thoughts as best we can. This is no solution, only a way to live.

__________________________________________________________________________

Klemke, “Living Without Appeal: An Affirmative Philosophy of Life,” 194