John G. Messerly's Blog, page 118

March 23, 2015

My Son’s Birthday

Thirty four years ago today my wife and I welcomed a beautiful son into the world. He was our firstborn. The thrill of watching him grow from an infant, to an inquisitive child, and to the wonderful adult he is today has been one of the most profound experiences of his mother and father’s lives. We cannot begin to express the joy he has brought us. All of this has reminded us of some simple poetry we read long ago:

Your children are not your children.

They are the sons and daughters of Life’s longing for itself.

They come through you but not from you,

And though they are with you yet they belong not to you.

You may give them your love but not your thoughts,

For they have their own thoughts.

You may house their bodies but not their souls,

For their souls dwell in the house of tomorrow,

which you cannot visit, not even in your dreams.

You may strive to be like them,

but seek not to make them like you.

For life goes not backward nor tarries with yesterday.

You are the bows from which your children

as living arrows are sent forth.

The archer sees the mark upon the path of the infinite,

and He bends you with His might

that His arrows may go swift and far.

Let your bending in the archer’s hand be for gladness;

For even as He loves the arrow that flies,

so He loves also the bow that is stable. ~ Kahlil Gibran

And what advice should we give our children? The best advice any parent can give their children is that they should strive for a meaningful life filled with joy, love, and inner peace. The best advice for parents is to listen to your children, they have a lot to teach you too.

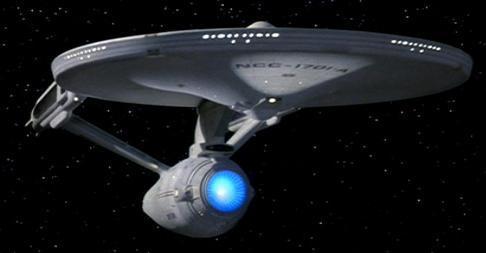

So happy 34th birthday to a most beautiful son, and thanks for all you have taught us. We love you son. Live long and prosper.

March 22, 2015

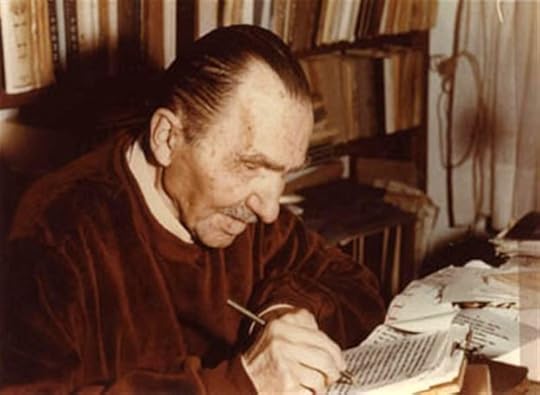

Nikos Kazantzakis: A Rejection of Hope

The Greek novelist Nikos Kazantzakis (1883 – 1957) wrote a 33,333 line sequel to Homer’s Ulysses. In Kazantzakis’ poem the bored Ulysses gathers his followers, builds a boat, and sails away on a final journey, eventually dying in the Antarctic. According to Kazantzakis, Ulysses does not find what he’s seeking, but it doesn’t matter. Through the search itself he is ennobled—and the meaning of his life was found in the search. In the end his Ulysses cries out “My soul, your voyages have been your native land.”[i]

Perhaps no one thought deeper about longings, hope, and the meaning of life than Kazantzakis. In his early years he was particularly impressed with Nietzsche’s Dionysian vision of humans shaping themselves into the superman, and with Bergson’s idea of the elan vital. From Nietzsche he learned that by sheer force of will humans can be free as long as they proceed without fear or hope of reward. From Bergson, under whom he studied in Paris, he came to believe that a vital evolutionary life force molds matter, potentially creating higher forms of life. Putting these ideas together, Kazantzakis declared that we find the meaning of life by struggling against universal entropy, an idea he connected with god. For Kazantzakis the word god referred to “the anti-entropic life-force that organizes elemental matter into systems that can manifest ever more subtle and advanced forms of beings and consciousness.”[ii]The meaning of our lives is to find our place in the chain that links us with these undreamt of forms of life.

We all ascend together, swept up by a mysterious and invisible urge. Where are we going? No one knows. Don’t ask, mount higher! Perhaps we are going nowhere, perhaps there is no one to pay us the rewarding wages of our lives. So much the better! For thus may we conquer the last, the greatest of all temptations—that of Hope.[iii]

I remember being devastated the first time I read those lines. I had rejected my religious upbringing, but why couldn’t I have a hope? Why was Kazantzakis taking that from me too? His point was that the honest and brave struggle without hope or expectation that they will ever arrive, be anchored, be at home. Like Ulysses, the only home Kazantzakis found was in the search itself. The meaning of life is found in the search and the struggle, not in any hope of success.

In the prologue of his autobiography, Report to Greco, Kazantzakis claims that we need to go beyond both hope and despair. Both expectation of paradise and fear of hell prevent us from focusing on what is in front of us, our heart’s true homeland … the search for meaning itself. We ought to be warriors who struggle bravely to create meaning without expecting anything in return. Unafraid of the abyss, we should face it bravely and run toward it. Ultimately we find joy by taking full responsibility for our lives— joyous in the face of tragedy. Life is essentially struggle, and if in the end it judges us we should bravely reply, like Kazantzakis did:

General, the battle draws to a close and I make my report. This is where and how I fought. I fell wounded, lost heart, but did not desert. Though my teeth clattered from fear, I bound my forehead tightly with a red handkerchief to hide the blood, and ran to the assault.” [iv]

Surely that is as courageous a sentiment in response to the ordeal of human life as has been offered in world literature. It is a bold rejoinder to the awareness of the inevitable decline of our minds and bodies, as well as to the existential agonies that permeate life. It finds the meaning of life in our actions, our struggles, our battles, our roaming, our wandering, and our journeying. It appeals to nothing other than what we know and experience—and yet finds meaning and contentment there.

Just outside the city walls of Heraklion Crete one can visit Kazantzakis’ gravesite, located there as the Orthodox Church denied his being buried in a Christian cemetery. On the jagged, cracked, unpolished Cretan marble you will find no name to designate who lies there, no dates of birth or death, only an epitaph in Greek carved in the stone. It translates: “I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free.”

The gravesite of Kazantzakis.

____________________________________________________________________

[i] James Christian, Philosophy: An Introduction to the Art of Wondering, 11th ed. (Belmont CA.: Wadsworth, 2012), 653

[ii] Christian, Philosophy: An Introduction to the Art of Wondering, 656.

[iii] Christian, Philosophy: An Introduction to the Art of Wondering, 656.

[iv] Nikos Kazantzakis, Report to Greco (New York: Touchstone, 1975), 23

March 21, 2015

Please Support the Institute for Ethics & Emerging Technologies

I know there are many requests for support from various individuals and organization, but I encourage my readers to support the Institute for Ethics & Emerging Technologies. Here is the mission statement from their website:

The Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies is a nonprofit think tank which promotes ideas about how technological progress can increase freedom, happiness, and human flourishing in democratic societies. We believe that technological progress can be a catalyst for positive human development so long as we ensure that technologies are safe and equitably distributed. We call this a “technoprogressive”orientation. Focusing on emerging technologies that have the potential to positively transform social conditions and the quality of human lives – especially “human enhancement technologies” – the IEET seeks to cultivate academic, professional, and popular understanding of their implications, both positive and negative, and to encourage responsible public policies for their safe and equitable use.

To understand more about their mission and the specific nature of their current fundraiser just click here. For a small $50 donation you get to choose one from among several of the most recent and important books in the genre. If there is anything worth supporting, it is a better future. I encourage you to consider supporting the future. ~ JGM

March 20, 2015

P. B. Medawar: Critique of Teilhard de Chardin

Yesterday’s post discussed the Teilhard de Chardin’s The Phenomenon of Man. While I do think the cosmic evolution holds the key to understanding if life is, or is not meaningful, I would be remiss if I didn’t note my discomfort with some of Teilhard’s more esoteric ideas. And I would also be negligent if I didn’t alert readers to the famous, devastating critique of Teilhard’s book by P. B. Medawar.

Sir Peter Brian Medawar OM CBE FRS (1915 – 1987)[1] was a British biologist born whose work on graft rejection and the discovery of acquired immune tolerance was fundamental to the practice of tissue and organ transplants. He was awarded the 1960 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet. For his works he is regarded as the “father of transplantation”.[2]He is remembered for his wit in real life and popular writings. Famous zoologists such as Richard Dawkins, referred to him as “the wittiest of all scientific writers”,[3] and Stephen Jay Gould called Medawar “the cleverest man I have ever known”.[4]

In 1961, in the philosophical journal Mind, Medawar reviewed Teilhard’s book. The review is unique in eviscerating both the book and its audience. Medawar begins:

It is a book widely held to be of the utmost profundity and significance … Yet the greater part of it … is nonsense, tricked out with a variety of metaphysical conceits, and its author can be excused of dishonesty only on the grounds that before deceiving others he has taken great pains to deceive himself. The Phenomenon of Man cannot be read without a feeling of suffocation, a gasping and flailing around for sense.

The book’s style and language appal Medawar: “the style that creates the illusion of content, and which is a cause as well as merely a symptom of Teilhard’s alarming apocalyptic seizures.” He hates Teilhard’s fuzzy concepts and obfuscating metaphors. “… he uses in metaphor words like energy, tension, force, impetus and dimension as if they retained the weight and thrust of their specific scientific usages.” And Medawar hates Teilhard’s adjectives:

Teilhard is for ever shouting at us: things or affairs are, in alphabetical order, astounding, colossal, endless, enormous, fantastic, giddy, hyper-, immense, implacable, indefinite, inexhaustible, extricable, infinite, infinitesimal, innumerable, irresistible, measureless, mega-, monstrous, mysterious, prodigious, relentless, super-, ultra-, unbelievable, unbridled or unparalleled.

And here is a typical incomprehensible paragraph:

Love in all its subtleties is nothing more, and nothing less, than the more or less direct tract marked on the heart of the element by the psychical converge of the universe upon itself.’ ‘Man discovers that he is nothing else than evolution become conscious of itself,’ and evolution is ‘nothing else than the continual growth of. … ‘psychic’ or ‘radial’ energy’. Again, ‘the Christogenesis of St Paul and St John is nothing else and nothing less than the extension … of that noogenesis in which cosmogenesis … culminates.

This may be profound—if only we knew what he was talking about. Medawar also felt this kind of writing appealed to the scientifically illiterate and the credulous.

Just as compulsory primary education created a market catered for by cheap dailies and weeklies, so the spread of secondary and latterly tertiary education has created a large population of people, often with well-developed literary and scholarly tastes, who have been educated far beyond their capacity to undertake analytical thought.

Ouch! Medawar concludes with an exhortation to clear thinking:

I have read and studied The Phenomenon of Man with real distress, even with despair. Instead of wringing our hands over the Human Predicament, we should attend to those parts of it which are wholly remediable, above all to the gullibility which makes it possible for people to be taken in by such a bag of tricks as this. If it were an innocent, passive gullibility it would be excusable; but all too clearly, alas, it is an active willingness to be deceived.

Such a critique reminds us not to take flights of fancy too quickly.

March 19, 2015

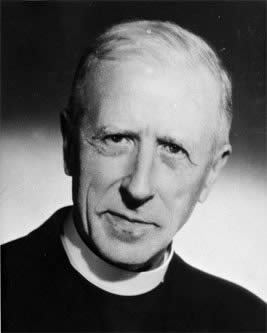

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin: Universal Progressive Evolution

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881 – 1955), a Jesuit priest trained as a paleontologist and geologist, was one of the most prominent thinkers who tried to reconcile evolutionary theory, religion, and the meaning of life. In his magnum opus,The Phenomenon of Man

he sets forth a sweeping account of cosmic unfolding.

While Teilhard’s philosophy is notoriously complex, the key notion is that cosmic evolution is directional or teleological. Evolution brings about an increasing complexity of consciousness, leading from an unconscious geosphere, to a semi-conscious biosphere, and eventually to conscious sphere of mind. The arrival of human beings on the cosmic scene is particularly important, signaling that evolution is becoming conscious of itself. As the process continues, the human ability to accumulate and transmit ideas increases along with the depth and complexity of those ideas. This will lead to the emergence of what Teilhard calls the “noosphere,” a thinking layer containing the collective consciousness of humanity which will envelope the earth. (Some contemporary commentators view the World Wide Web as a partial fulfillment of Teilhard’s prophecy.)

Not only does evolution explain how mind arose from matter, it is also the key to all metaphysical understanding, if such understanding is to be based on a firm foundation.

Is evolution a theory, a system or a hypothesis? It is much more: it is a general condition to which all theories, all hypotheses, all systems must bow and which they must satisfy henceforth if they are to be thinkable and true. Evolution is a light illuminating all facts, a curve that all lines must follow. [i]

Teilhard recognized this evolutionary worldview, with its oceans of space and time, as a source of disquiet for minds previously comforted by childlike myths. Anxiety begins when we reflect, and reflection on the nature of the universe clearly discomforts.

Which of us has ever in his life really had the courage to look squarely at and try to ‘live’ [in] a universe formed of galaxies whose distance apart runs into hundreds of thousands of light years? Which of us, having tried, has not emerged from the ordeal shaken in one or other of his beliefs? And who, even when trying to shut his eyes as best he can to what the astronomers implacably put before us, has not had a confused sensation of gigantic shadow passing over the serenity of his joy? [ii]

Yet psychic troubles derives from this evolutionary worldview. “What disconcerts the modern world at its very roots is not being sure, and not seeing how it ever could be sure, that there is an outcome—a suitable outcome—to that evolution.”[iii]But alas the source of our discomfort is also the fount of our salvation. For if the future is open to our further development, then we have the chance to fulfill ourselves, “to progress until we arrive … at the utmost limits of ourselves.”[iv]

The increasing power and influence of the noosphere or world of mind will culminate in the Omega Point—a supreme consciousness or God. At that point all consciousness will converge, although Teilhard argues that individual consciousness will somehow still be preserved. While the Omega point is extraordinarily difficult to describe, it must be a union of love if it is to be a sublimely suitable outcome of evolution. Here Teilhard waxes poetic:

Love alone is capable of uniting living beings in such a way as to complete and fulfill them, for it alone takes them and joins them by what is deepest in themselves. This is a fact of daily experience. At what moment do lovers come into the most complete possession of themselves if not when they say they are lost in each other? In truth, does not love every instant achieve all around us, in the couple or the team, the magic feat, the feat reputed to be contradictory, of personalizing by totalizing? And if that is what it can achieve daily on a small scale, why should it not repeat this one day on world-wide dimensions?[v]

In Teilhard’s vision, all reality evolves toward higher forms of being and consciousness, which includes more intense and satisfying forms of love. Thus spirit or mind, not matter or energy, ground the unity of the universe; they are the inner driving force propelling evolution forward. (This is Teilhard’s god.) Teilhard found meaning and purpose in this sweeping epic of cosmic evolution in which the endpoint of all evolution will be the highest good.

(Note – I do have doubts about some of Teilhard’s esoteric ideas and concepts. A lot of what he says is profound, but some of it is probably nonsense. For the most devastating critique of Teilhard ever penned see the great biologist P. B. Medawar’s “Review of the Phenomenon of Man” (1961). I will write about this in tomorrow’s post.)

______________________________________________________________________

[i] Teilhard de Chardin, Pierre, The Phenomenon of Man (New York: Harper Collins, 1975), 219.

[ii] Teilhard de Chardin, The Phenomenon of Man. 227.

[iii] Teilhard de Chardin, The Phenomenon of Man, 229.

[iv] Teilhard de Chardin, The Phenomenon of Man, 231.

[v] Teilhard de Chardin, The Phenomenon of Man, 265.

March 18, 2015

The Origin of Scientology

Salon magazine recently featured an article about the forthcoming Oscar-winner Alex Gibney’s explosive new HBO documentary “Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief.” I encourage my readers to view the article and the documentary about this horrific cult. It saddens me that life’s difficulties compel some people to turn to nonsense for comfort. And it makes me sad that that people exploit others who are having trouble.

Pursuant to the above paragraph, I thought my readers might be interested in this video. In it L. Ron Hubbard’s great-grandson suggests that L. Ron was a disturbed charlatan. One can’t conclude that all religions start with psychopaths, but no doubt many did. (You know the old saying: “when a few people believe something crazy, it’s called a cult; when many people believe something crazy, it’s called a religion.”) You can’t buy the answers to life’s big questions, as Spinoza noted 400 years ago:

“If the way which, as I have shown, leads hither seem very difficult, it can nevertheless be found. It must indeed be difficult, since it is so seldom discovered, for if salvation lay ready to hand and could be discovered without great labour, how could it be possible that it should be neglected almost by everybody ? But all noble things are as difficult as they are rare.”

March 17, 2015

Carl Sagan’s Pale Blue Dot Revisted

The astronomer Carl Sagan is one of my intellectual heroes, and one of the great secularists of the twentieth-century. In 1989, after both Voyager spacecraft had passed Neptune and Pluto, Sagan wanted a last picture of Earth from “a hundred thousand times” as far away as the famous shots of Earth taken by the Apollo astronauts. No photo has ever put the human condition in better perspective; it is worth seeing and hearing at least once a year for the rest of one’s life. Thank you Carl Sagan.

The text:

“Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there-on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot.

Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand.

It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”

March 16, 2015

Different Kinds of Love

I have discussed love in a number of previous posts here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here. But it occurs to me that we need to carefully define love.

The Different Kinds of Love

The Greeks distinguished at least 6 different kinds of love:

1) Eros was the notion of sexual passion and desire but, unlike today, it was considered irrational and dangerous. It could drive you mad, cause you to lose control and make you a slave to your desires. The Greeks advised caution before one gives into these desires.

2) Philia denoted friendship which was thought more virtuous than sexual or erotic love. It refers to the affection between family members, colleagues, and other comrades. However these persons are much closer to you than Facebook friends or Twitter followers.

3) Ludus defines a more playful love. This ranges from the playful affection of children all the way to the flirtation or the affection between casual lovers. Playing games, engaging in casual conversation, or flirting with friends are all forms of this playful love.

4) Pragma refers to the mature love of lifelong partners. After a lifetime of compromise, tolerance, and shared experiences a calm stability and security ensues. Commitment between partners is the key; they mutually support and respect each other.

5) Agape is a radical, selfless, non-exclusive love; it is altruism directed toward everyone (and perhaps to the environment too.) It is love extended without concern for reciprocity. Today we would call this charity; or what the Buddhists call loving kindness.

6) Philautia is self-love. The Greeks recognized two forms. In its negative form phiautia is the selfishness that wants pleasure, fame, and wealth beyond what one needs. Narcissus, who falls in love with his own reflection, exemplifies this kind of self-love. In its positive form phiautia refers to a proper pride or self-love. We can only love others if we love ourselves; and the warm feelings we extend to others emanate from good feelings we have for ourselves. If you are self-loathing, you will have little love to give.1

These distinctions undermine the myth of romantic love so predominant in modern culture. People obsess about finding soulmates, that one special person who will fulfill all their needs—a perpetually erotic, friendly, playful, selfless, stable partner. In reality no person fulfills all these needs. And the twentieth-century commodification of love renders the situation even worse. We buy love with engagement rings; market ourselves with clothes, body modifications, Facebook profiles, and on internet dating sites; and we look for the best object we can find in the market given an assessment of our trade value.

This is not to suggest that everything is wrong with the modern world or that the internet isn’t a good place to find a mate—it may be the best place. (Although I’m much too old to worry about it!) Rather I suggest that to be satisfied in love, as in life, one must cultivate multiple interests, strategies, and relationships. We may get the most stability from our spouse, but find playful times with our grandchildren or our golfing partners; we may find friendship with our philosophical comrades; and we might find an outlet for altruism in our charitable contributions or in productive work.

As for our most intimate relationships, we would do best to lower our expectations—again no one satisfies all our needs. As I said in my previous post, this is not the idealized love of Hollywood movies, but it is real love. No, you won’t have heart palpitations every time you see your beloved after 35 years, but you will feel the presence that accompanies a lifetime of shared love, a lifetime of struggling and fighting and working together. You will feel the continuity of knowing someone who knew you when you were young, middle age, and old, and they will feel the same. The accompanying serenity is peaceful and priceless. I hope everyone can experience this.

1. Rousseau made a similar distinction between amour-propre and amour de soi. Amour de soi is a natural form of self-love; we naturally look after our own preservation and interests and there is nothing wrong with this. By contrast, amour-propre is a kind of self-love that may arise when we compare ourselves to others. In its corrupted form, it is a source of vice and misery, resulting in human beings basing their own self-worth on their feeling of superiority over others.

March 15, 2015

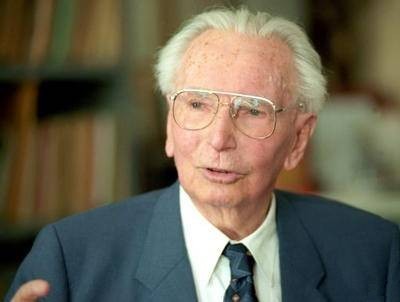

Meaningful Suffering

After hearing heartbreaking stories on the radio about what desperate children want—food, medicine, parents—it got me thinking about whether philosophical ruminations about the meaning of life are really important.

I think we can say that one’s basic needs must be met first before we can think about abstract philosophical problems. So food, clothing, shelter and the like are fundamental human needs without which the needs for self-actualization (as in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs) cannot be met. Survival is more basic than meaning. Perhaps this is what is meant by the cliché “philosophy bakes no bread.”

Still, after all basic human needs are met, human life will not necessarily be meaningful. Basic needs are a necessary but not sufficient condition for human flourishing. Aristotle thought the same thing; bodily and physical goods are necessary for good human lives, but they are not sufficient. For full human flourishing, for full human meaning and happiness we also need what Aristotle called “goods of the soul,” essentially the need for self-actualization as in Maslow’s hierarchy.

In cases of extreme deprivation the basic needs obviously come first. We ought to create a world where everyone has at least the minimum amount necessary to lead decent human lives. When that is accomplished, we can then move to creating a world where everyone has the opportunity to flourish by actualizing their potential.

Thus Frankl may have been wrong to claim that the search for meaning is the primary motivation of human life; survival needs are more basic. But as soon as those needs are fulfilled, the desire for meaning swells up from within. And I think the reason is as follows. Yes, philosophy bakes no bread, you can’t eat your thoughts. But in another sense no bread is baked without philosophy. For why do anything—even try to survive—if we don’t have a reason for living? If we don’t think our lives are meaningful?

When science and technology are available to provide for everyone’s basic needs, and when humanity has the moral and political will to use that technology to provide for everyone’s needs, we will have taken a first step toward creating a better world. But much will remain to be done. We will need also to create a world where everyone can flourish as humans or even as post humans, a place where life will be both beautiful and meaningful. We must first address suffering; but we must also address meaning.

March 14, 2015

Meaningful Work

Victor Frankl claimed that creative, productive work was one of the three main sources of meaning in human life. (The others are human relationships and bearing suffering nobly.) If the most meaningful lives entail meaningful work a number of questions arise. What kind of work is meaningful? Is meaningful work an objective or subjective notion? Can we find meaningful work in a capitalist economic system? Can we find meaningful work in any conditions?

Consider that you are a hunter gatherer. You are walking along hunting and gathering. This is work, but is it meaningful? Ultimately this question relates to the question of whether life is meaningful. If life is meaningful, then we would have to infer that hunting and gathering the food that makes life possible is meaningful.

Now let’s consider that the agricultural revolution has taken place. There is now excess food so one can be an artist, philosopher, priest, engineer, merchant or statesman. Are these occupations more meaningful than hunting and gathering? Here the answer is subjective. Some would prefer growing food; others prefer creating art or reading books or running governments. If you want to grow food and find that more meaningful than writing computer code or trading on Wall Street, then by all means do it.

Now let’s consider a complicated global economy. You could still write books or paint pictures, but you might make more money on Wall Street, practicing medicine, or writing computer code. Suppose you’re convinced that the former is much more meaningful (to you) than the latter? If you are equally capable of being a starving artist as you are of writing computer code then you must decide what’s more important—the money or the work. Would you rather make $20,000 a year selling art or teaching school or $200,000 a year practicing medicine or being a software engineer? The answer seems to depend on the individual. Most people would probably take the higher salary because of the security and freedom they gain from the extra income—an earlier retirement, less financial stress, more money for their children, etc. But many would choose differently. Perhaps the higher paying jobs have more stress or are less fulfilling.

Now if you think this global economic system is corrupt, that participating in it violates your values, then you could choose the less corrupt occupation. Perhaps practicing medicine or writing computer code exploits more individuals than teaching school or being a social worker. If you are convinced that any work makes you complicit in an immoral system, then you could move to a more socialistic country or, even more radically, you could move “off the grid” or, if possible, you could move to a new planet and create a new Eden. (More than one Star Trek episode has explored such themes.)

But is it necessarily more meaningful to live outside the world’s economic system or on a different planet? I’m not sure. Rousseau argued that we become human to the extent we participate in civilization. He thought that being civilized was better than being a “noble savage.” I do think we have more opportunities for meaningful lives in our present time, with our present technology, then we have had at any other time in human history. In the past few people read books, practiced medicine, designed the internet or received the goods and services that many of us now do. Do these goods and services make our lives more meaningful? I think so. If meaning is emerging it is primarily because science and technology have created the conditions that make human flourishing possible. This doesn’t guarantee that everyone flourishes though, primarily because of flaws in human psychology, biology and in the flawed political systems human create.

Still this does not answer all our questions. Perhaps you would rather care for your child than advance your career; perhaps you would rather teach than write computer code. In the end each person must make the best choice they can … and then hope for the best. The tragedy is that we live in a world where such choices must be made. I must work multiple low paying jobs, sell my services as an athlete and damage my body for life, or do other work which isn’t meaningful.

Yet we should not curse this world; nor feel existential guilt in it merely by being alive, for there is meaningful work in the world. Maybe not perfectly or fully meaningful, but meaningful nonetheless. And with effort we can find it. Good luck.

Man’s search for meaning is the primary motivation of his life. This meaning is unique and specific in that it must and can be fulfilled by him alone; only then does it achieve a significance which will satisfy his own will to meaning. ~ Victor Frankl