Elizabeth Knox's Blog, page 2

November 11, 2014

Don’t say ‘sacrifice’

For Armistice Day here is my foreword to the Second Edition of my 1987 novel, After Z-Hour. More photos will follow. They are are being scanned by my scanning-elf.

John James ‘Jack’ Knox with son Jack and wife Rose

After Z-Hour is a ghost story in which one character declares, ‘We we all ghosts’, and in which time and space, period and place, are interpenetrating. It’s a book about memory and trauma set in a haunted house during a storm. And a book where everyone longs for home, and no one gets to go there.

I have a letter from my grandmother to my great uncle Jack (John James Knox) dated 8 July 1918. She is writing to give him the news of the birth of his second child, a daughter, Kathleen. She reports how his wife Rose—grandma’s sister— is getting along, and the baby, and Jack’s son, also Jack. ‘He would have you in fits of laughter, if you say where’s daddy gone, he says to the war to fight the Germans, he speaks so plainly for his age, God bless him. He says God bless daddy!’

Grandma’s letter came back with Jack’s belongings, so his family knew he had got it and its happy news. Jack’s belongings had been packed up and sent after him when he was wounded, and in time found their way back to the household at 12 Hospital Road, Newtown. But Jack did not. John James Knox was one of a handful of New Zealanders among 123 who died when the hospital ship Warilda, carrying wounded from Le Havre, was torpedoed and sank on the 3rd of August 1918.

I’ve been on Vimeo and looked at the schools of fish herded this way and that through the halls and companionways and across the decks of ‘one of the best diving wrecks in the channel’. The schools of fish are more expressive of the family’s thoughts about Jack than the marble of the Wellington Provincial War Memorial—the way they drift away, change shape, and return.

My grandmother married Jack’s brother Joe after the war—so that Jack’s son and daughter were my father’s cousins twice over. That double-strength blood bond kept drowned Jack Knox very present in the family; present as a blank loss, not a ‘sacrifice’.

I have written in my essay ‘On Being Picked Up’ about the moment when it first occurred to me what all this might mean. I was eleven and waiting with my father in Wellington Hospital’s Casualty ward after having fallen out of a tree.

It was a very busy day: a public holiday, ANZAC Day. Just down the hall a little girl who had swallowed some household poison was having her stomach pumped—a noise I’ve never heard on a hospital drama soundtrack. We knew what her problem was because an old man came along and leaned on the doorframe and said, ‘That poor wee girl.’ He had a bloodstained bandage wrapped around his head—my first blood in Casualty. He wore a suit that was shiny with wear. He was thin, with wrist bones like ping-pong balls. He told us that he’d been drinking and had fallen over in the street, hitting his head on the curb. Just below the bandage, by one ear, he had a scar, a long depression filled with smooth, snowy skin. It was an old shrapnel scar.

The old man started to talk to Dad about Passchendaele and life on the Salient in 1917. And I listened. Then Dad said a few things about his father, who had been there too. A nurse came by and tried to move the old guy and Dad said, ‘He’s all right, don’t bother him’, and she went away again.

And I was picked up. Because I had been in pain and wasn’t any more. Because I was hearing a story about horror and loss, the storyteller’s horror and loss, with a backing of these awful stomach-pump noises, and the sight of blood, a recent injury standing in for an old one—and because my father was talking about his father, whom he never talked about—I was picked up. Inspired. A subject had got hold of me until I had it out with it, in my first published book, After Z-Hour.

When my son, Jack, was in Year 11 at Wellington College he came in from a very long Anzac Day assembly, crawled up the last flight of stairs, and flopped at my feet. He didn’t complain of being bored, or even outraged. Instead he was filled with gloom and disgust, and this was how he explained himself (I wrote it down): ‘I just feel the whole thing is meant to prepare us to go be killed in some war, if there’s another big one. It’s all about how those soldiers were heroes who made a sacrifice. I was complaining to ——— afterwards about how the speakers don’t seem to be able to tell the difference between the reason soldiers died in World War 1, and why they died in World War 2. And ——— said I was dishonouring the dead. So, if I say their deaths were pointless I’m dishonouring them. But aren’t I honouring them if it’s true? That war didn’t do anyone any good, and now its just being used as an exercise in building school spirit.’

Jack was right. Even more so now, when Anzac Day is, year by year, becoming less a focus for national mourning than national pride—and, too often, a nation-building exercise. But Lest We Forget: for all the good and meaningful stories we’ve inherited, and the friendships formed and horizons expanded for that generation of combatants, it would have been a better, wiser, kinder fate for all those young men to have stayed at home.

Rereading After Z-Hour for the first time in over 25 years, I noticed how it is now set in two historical periods: 1916 to 1920, and the mid-1980s. So, along with the World War 1 story, there are also apparitions from that second bygone age. There’s the National Weather Bureau, tobacco-drying kilns in Riwaka, the Ministry of Works, street preachers railing against the evils of cash machines, and people as likely to drink sherry at home as wine. Plus student flatmates called Andrea, Sue and Mike, rather than Jacob, Dylan and Lily, and the idea of young people able to study things not vocationally, but for the sake of of learning.

This is a young writer’s novel, filled with intensity and evidence. And I’m particularly proud of the prescience of its youngest character, the Machiavellian Kelfie, who imagined pretty clearly the world we find ourselves in now.

For this new edition, I took the opportunity to make a few changes, mostly the vaunting dyslexic madness of the opening page and a half. Those paragraphs are now neatly combed and set in order. (Bill Manhire and Fergus Barrowman, faithful people, thought I was stretching out into my experimental style!) Also, throughout the novel, many semicolons have gone the way of all semicolons, and become a full stop and a new sentence. What I retained that still make me nervous are the pronoun-less opening passages of the first Mark chapter. My plan at the time was to have a ghost coming back to life by coalescing in the cloud of his life’s great and small moments, and his memories of the material. So—straw mattresses in a tent at the Trentham camp, the wet decks of a troopship, fallen snow feathering barbed wire. For a few paragraphs there is no distinct point of view at the centre of the memories. And then a ‘we’ appears. Mark is ‘we’ even as he comes back without his friends.

My grandmother Kathleen King and her sister Rose at war fund dance in 1914

October 12, 2014

Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita

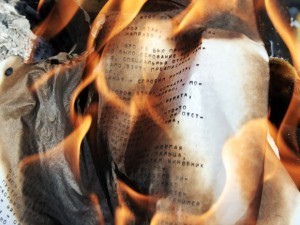

“Didn’t you know that manuscripts don’t burn?”

I first read The Master and Margarita when I came across it in the Tawa College library. It must have gone deep into me because I didn’t realise until I reread it many years later how much it had influenced me.

It comes at its main story by two debonair flanking movements. The devil and his retinue appear in Moscow in the slightest of disguises, and go largely unrecognised because vain members of Masslit – the writers union – and venal theatre managers, and rapacious, luxury-starved Muscovites, are all too busy being themselves, thus collaborating with the devil’s obscure mission – which might simply be to host his annual slap-up party. It is a book in which a novelist is driven mad by despair, and burns the manuscript of his book about which editors and critics have only wanted to know why he, ‘a Muscovite in this day and age’, wrote a novel ‘on such a curious subject’. The Master’s novel concerns Pontius Pilate. The reader encounters the novel’s story of Pilate in chapter two, around 150 pages before the man writing the Pilate novel – the Master – makes his appearance. We don’t know why we’re being told about Pilate. We do know it’s riveting. The Pilate chapters, which appear at intervals in the novel, are measured, realist, vivid. So is the ostensibly most fantastical chapter, in which the Master’s lover, Margarita, turns into a witch and flies around the city causing mayhem, then travels upriver on a senses-saturating summer night. Margarita’s every witchy move is real, concrete, logical. But the novel also has scenes in a confined commonplace present: the offices of a theatre manager, where a couple of worldly men get excited trying to work out why someone would be pretending to be the theatre treasurer and claiming to have been magically transported to Yalta. They discuss a series of telegrams from someone in Yalta. And the telegrams keep arriving, carried by the same girl from the post office, giving the two guys just enough to react to each message before she walks in with the next. It plays like a stage farce.

It is this melting, shimmering quality that I most love. The novel manages to be is stately and tragic – in Pilate’s and the love story – while also being antic and flamboyant. It thrives on madness and mixedness, but the net result is a strong sense of mission which I suppose could be distilled down to this idea: How easy it is for cruel and implacable individuals to create a world in which it is almost impossible for decent people to do good. Just that idea, with myriad proofs. It’s a novel in which almost all the heroes are compromised or defeated, and have given up on civilisation to save their souls.

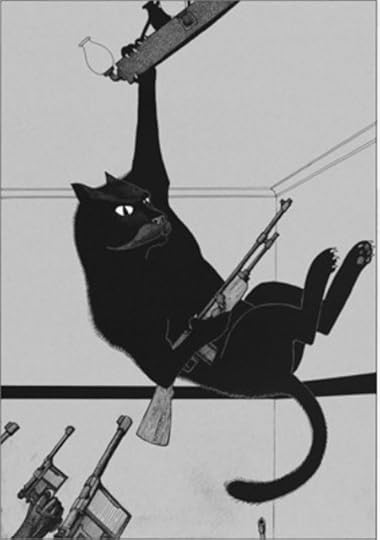

When I read The Master and Margarita at sixteen I thought it was the strangest and most astonishing book. I’ve read it twice since. It has changed and deepened, both with my accumulated life and with history, and is still the strangest and wildest, and wisest, book I’ve read. And the next time someone asks me dubiously about my use of fantasy I will wish that Woland would dispatch the black cat Behemoth to smack them in the ear.

April 17, 2014

They Come to Class

After reading Jolisa Gracewood’s post School Bully on her blog Busytown —an impassioned argument about the wisdom of teaching for testing—I’ve had a number of conversations about the direction and future of education. This guest blog, by a highly dedicated (and now despairing) teacher in the tertiary sector, is the result of one of those conversations.

They come to class, most of them. They turn up on time, or late, and queue after the end of teaching to get their names ticked off the roll. There’s no attendance criterion, but turning up seems to be taken as the principal work of doing a subject, which is why the weeks before the start of semester are so hectic, with everyone jockeying for the best timetable pattern they can get. But the day after results for the first assessment are released the round tables in the blending learning space have two or three people at them, not the usual five or six. Even though the day’s teaching is to help them with their next assignment, it is resentment, not practicality, that wins out.

They come to class, most of them. They turn up on time, or late, and queue after the end of teaching to get their names ticked off the roll. There’s no attendance criterion, but turning up seems to be taken as the principal work of doing a subject, which is why the weeks before the start of semester are so hectic, with everyone jockeying for the best timetable pattern they can get. But the day after results for the first assessment are released the round tables in the blending learning space have two or three people at them, not the usual five or six. Even though the day’s teaching is to help them with their next assignment, it is resentment, not practicality, that wins out.

It is the 7th week of semester. Once again the girl who sits with the girl with the straightened hair, the girl whose phablet is always in or near her hand, has not brought her book of essential readings to class. We have this routine. I lift my eyebrows, and say, ‘So you haven’t got your reader?’ ‘Do I need it?’ she asks, and I walk to the next table, laughing. Today, once again, most of them haven’t done the reading, and when I play the video lecture pods quietly in the background, the girl who never brings her unit reader points at the woman on screen and says, ‘Who’s that?’I mime a button being pushed, an ejector seat going up. ‘Massive fail,’ I say, ‘that’s the other lecturer. As everyone knows.’ I resist looking around the room: there were fewer laughs at the ‘Who’s that?’ than I’d expected, which means there are other people who haven’t watched the lectures, and don’t know what’s going on. Other people who will probably write anxious emails to me the night the next assessment is due, saying, ‘I don’t understand the instructions. Tell me what I have to do.’

I did tell them what they had to do at the time—when we were doing that week’s stuff. They were sitting in class, they were present—most of them—when we did the practical exercises, and ran through the conceptual terms. They sat at their round tables, staring at me as I stepped them through what their portfolio was, and what they had to do, what we expected to see. They were right there when I took them through it. Conversation analysis maybe, or semiotic analysis: Charles Sanders Peirce, he of the long beard and the overblown typology of signs: 60,000 separate elements. But the coarse makes it simple, going over Peirce’s trichotomy of signs: index, symbol, icon. Three is ok. Three is good. The holy trinity of signs. And when the assessment comes in, I find I’m marking one about Peirce’s tracheotomy. The word recurs. On the third repetition I write in the margins: ‘Did he do it with the casing of a ball point pen?’ realising, as I write it, that this is what being defeated means, and this is what I’ve come to.

Most of our students in the Bachelor of Arts are just travelling through—the BA is the gateway to a Masters of Teaching. They are training to become teachers, primary and secondary. I wonder a lot of the time now what they’re going to teach, what stuff of the world is in them that they’ll draw out for the children in their charge. Because they are not learning much here—they come to class, and that’s it. They don’t read. They don’t come to lectures, or watch the lecture pods that we’ve made, not like filmed lectures, but like film, they’re so highly produced. Most of them don’t watch them. And if I show an excerpt of a film in class and ask a question about some shot, or section of dialogue, most of them can’t remember it. Even if I’ve paused the video just after the line in question has been spoken.

One of my colleagues was teaching his First Years about metaphor. Whether its about Judy Garland and the musical or the behaviour of the gerund this man is as clear and engaging a teacher as you could ever want. That week he was teaching metaphor, by example and analogy, given that that’s the logic of metaphor. Loving a good show tune, he plays them Barbra Streisand’s ‘Evergreen’, then he asks them to unpack the song’s structure of metaphor. But there is no-one in the class who knows that there’s a type of tree called ‘evergreen’.

This is the problem of teaching now, not what to teach, nor even how: it’s how to manage the impossibility of teaching when there is nothing to teach to; nothing to hang the ideas off, no language to build on. Not even stories commonly shared. I use the Titanic a lot, because nearly everyone knows what it was, and that it sank. It is my principal teaching analogy now: that unsinkable ship, that wreck.

It used to be that before the start of a semester I’d have teaching nightmares. That I am late to class, that the tutorial room is in a building in another campus, that the tutorial room is in mid-air, above my head, with no way up to it. Those dreams come more frequently now. In my most recent, I am running to class but get caught in a crowd of people moving in another direction, and when finally they disperse I find I’m on a ferry, and there’s a widening expanse of sea between me and the building in which I teach.

February 12, 2014

Brothers and Sisters: A Grimm tale

I wrote this for a Grimm’s fairytale Bicentenary event. It was published in Sport Magazine in 2012, and I think it deserves another outing.

Stargazer is running the meeting. He unlocks the room and puts a fresh bag in the coffee machine. Hansel arrives with muffins.

Stargazer is running the meeting. He unlocks the room and puts a fresh bag in the coffee machine. Hansel arrives with muffins.

Stargazer is a pretty smug fellow. Things worked out for him and his brothers. He likes to say, ‘We had a dust-up but not a bust-up.’ He also likes to say that no princess can replace your brothers (but never ‘Bros before hos’ because even he can’t be sure princesses won’t be present).

When people start arriving there are some familiar faces. The two ugly, limping women. And Hansel of course, his fat fingers still fidgeting over the muffins. Hansel blames his bad relationship with food on ‘what happened’. He still dreams about being force-fed, and complains about how long he was in the cage before his sister acted to save him.

There are a couple of eldest brothers, going thin on top, anxiously checking their phones, and only reluctantly turning them off. There’s a Chinese guy with old horn-player’s cheeks. He’s new.

Before they sit down, Stargazer has them move the chairs into a wider circle to make room for the sad-faced boy in the big orthopaedic boot, and another one who is wearing his bulky coat like a cape and constantly reaching one hand into its pocket to get at the trailmix he has stashed there.

But, before long, they’re all settled. Stargazer welcomes everyone. He spreads his hands and asks who’d like to start. Of course it’s the ugly sisters. These two have been coming for quite a while and they’re not gradually getting themselves to a better place. They’re just finding refinements for their cause for complaint.

‘So,’ thinks Stargazer, to whom nothing should surprise since he can count the birds in their nests at the tops of tall trees, ‘So— now it’s all their mother’s fault.’

One sister is saying, ‘It would be so much better for us if we hadn’t completely alienated little Ashputtel. But oh no, being stepmother of the Queen wasn’t good enough for Mother.’

‘Cutting off her nose to spite her face,’ says her sister. And the oldest and ugliest draws her brows together and looks pointedly at her sibling’s open-toed sandals. ‘More like cutting off a toe to spite someone else’s foot.’ The younger sister makes a noise of protest. Her disabilities are less visible—it was a heel she lost, not a toe—so she has to make more of a song, if not a dance about it.

‘It isn’t your stepsister or your mother who is the problem. It’s those damn fairies,’ says Briar Rose.

‘Or witches,’ says someone else.

Stargazer tries to think how to lead the discussion away from witches and fairies. He reminds everyone how unproductive it is to blame fairies and witches for family problems—and unlucky, since both can hear themselves being maligned from leagues away.

The Chinese Satchmo is shaking his loose jowls. Stargazer feels he should ask the man what he has to say, but when the man moves he gives off a dank fishy smell, like the seafloor. Stargazer has a strong suspicion that the fellow doesn’t quite belong, and that something alarming will happen if he does open his mouth.

‘It’s promises that are the problem!’ shrieks the funny little man, jumping up and down on his chair. He does that a lot. ‘Bargains and promises. They want them. Then they can never keep them.’

‘But who are they?’ says Stargazer, very wisely.

‘There is no They,’ says Rose Red, who’s a bit of a teacher’s pet, and only—she says—in the group because she’s mildly peeved that it was her sister who got the original Bear Prince while she had to make do with his far less husky brother.

The little man’s eyes pop. He fumes. Rose Red smirks at him—he’s just like a dwarf she knew once, and teasing him makes her quite nostalgic.

However, the room has already taken up the idea. ‘Yes, it’s the promises,’ says the boy in the coat-cape.

‘It’s breaking them,’ argues the sad-faced lad in the orthopaedic boot.

‘No, it’s keeping them,’ says the boy in the cape. ‘And being the youngest.’

‘Oh don’t give me that!’ snaps an elder brother. ‘I stayed home and looked after my father, who would weep every day about how hard he’d been on my youngest brother Heimdel, and meanwhile the whole world, and a princess, jumped into Heimdel’s lap!’

The other elder brother chimes in: ‘It’s easy for the youngest. He sets out last. He learns from our mistakes. Just once someone should send out the youngest first!’

The little man is still dancing about on top of his chair shouting about cheats.

‘Please sit down, Timothy, Ichabod, Benjamin, Jeremiah,’ says Stargazer.

‘That’s not my name,’ the little man gloats—but he resumes his seat. ‘Wretches all!’ he mutters. ‘Women! They’d rather marry the nasty cove who locks them in a tower and makes them spin straw into gold, than show any regard for the fellow who saves their bacon.’

‘With those promises there are always too many rules,’ says the former Goose Girl, now the Queen. She’s an only child so by rights shouldn’t be in the group at all—but her claim is that she saw her maidservant as a sister and just can’t get over the identity theft. ‘It’s terrible not being able to tell your own story.’

‘Or having no one around anymore who remembers your story,’ says the sad boy in the orthopaedic boot. ‘If only the town burghers had kept their promise to that man who came with this flute and vacuumed up all the rats. Then I would never have been left alone at the stone door in the mountain after all my playmates danced away inside—my playmates, who were like brothers to me.’

‘But things got so much better for me when I broke my promise and told my story,’ says the former Goose Girl.

‘You have to remember that abusers are always trying to get you to keep their secrets,’ says Stargazer, a routine observation. Then he sees a space for speechmaking. ‘But let’s think about these promises. What is a promise? A promise can help us not have to make further decisions on one subject. We know what our course will be with the promise. A promise is a way of imagining ourselves in the future, and making a pact with our future selves. Promises can give us a sense of identity . . .’

‘Promises can give us bupkis!’ says the little man, steam coming out of his ears.

‘My sister promised,’ says the young man wearing his coat as a cape. His eyes are on the former Goose Girl. ‘My sister kept silent. Even when she was on the gallows she kept her mouth shut and went on knitting her nettle shirts.’ He brushes the birdseed off his fingers and unfastens the button on the cape. He unfurls his single white wing. ‘This is the result of promises. And of being the youngest.’

There is a silence in the room. People hold their breath—the Chinese trumpet player continues to hold whatever it is he has in his mouth.

Finally, Stargazer says, very politely, ‘I’m sorry, but the Hans Christian Andersen group is in the church across the square.’

January 10, 2014

Why Horror?

This essay first appeared, in a slightly less finished form, in Canvas. I sat on it awhile before posting.

Horror has been called the most moral of the genres, perhaps because it deals in calamity, in inexorable events and the experiences of small human victims, witnesses, collaborators. Because human existence is prone to repeated visitations from monstrosity in the shape of war, disease, and natural disasters, we have deep feelings about these things, and some of those feelings are about appeasement, and come from the same instinct that prompts us to pray.

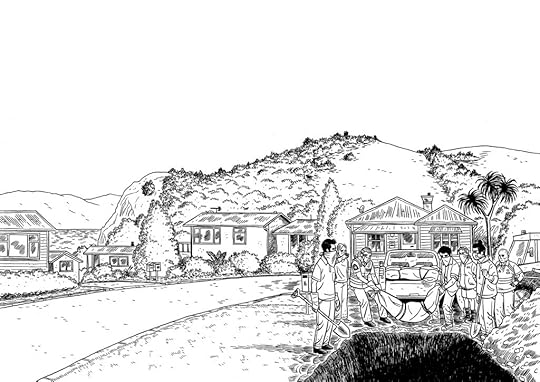

If asked, most of us could make a list of things we know the characters in horror film and novels should avoid doing – or being, as in the case of the unchaste blond girl. Joss Whedon’s Cabin in the Woods plays with all those expectations and, at the same time, makes them the guiding evil secret behind the fate of everyone in the story (the great gods of chaos are being appeased by ritual sacrifices where the rituals are a series of variations on horror narratives. The hero, whore, fool, and virgin are what the sacrifice requires; human stand-ins for story). Whedon really gets the connection between horror stories and our deep instinct for appeasement. I began by wanting to write a horror novel partly for the simple challenge of trying for effects that would inspire fear. That urge was enough to give me a seventy pages of mayhem (which survive, radically altered in tone), but it wasn’t enough for a novel. In the end I persisted in writing Wake because horror was personally useful to me, because horror stories are about helplessness, and our feeble efforts to make ourselves safe, and about doing the right thing in the face of narrowing choices.

In the best horror stories, in the end, the danger for the heroes isn’t death, it’s doing the wrong thing by others, somehow failing that final companion who makes the experience bearable, and surviving it sustainable. Because a sole survivor hasn’t any other witnesses. No one to agree, ‘Yes, that happened.’ The sole survivor has the burden of explaining themselves, and never being fully understood. So, in horror stories, the most valuable life is that of the last person to die (because there’s usually a survivor). Horror stories are also about madness. How to respond to a world that is behaving in an utterly unreasonable way. A world where what was merely material and accidental suddenly seems to have sinister significances, traps and portents, and behind that maybe even a scheming and malevolent intelligence. (If you’ve ever tried to reason with someone in the throes of paranoid psychosis, all this will make real terrifying sense. And I’ll admit this much, I was writing about this because it was near to me and I had to deal with it, think about it, be responsible).

I started writing a horror novel for reasons of dread a little mysterious to me then, and as an exercise in seeing whether I could scare my readers. I continued writing because it was a very suitable way of talking about calamity, and how we cope — because of actual, biographical calamities, and having to cope. And I chose the non-realist mode because that’s what I do, and because of a deep aversion to a what is sometimes termed ‘catastrophe porn’: a sub-genre of that crypto-genre literary fiction. Catastrophe porn is a term sometimes used to characterise books that get their dignity from being ‘about’ real historical atrocities: wars, massacres, genocides. These are books written not by survivors or their children, but by authors for whatever reason wanting to grapple the world’s acknowledged serious matters.

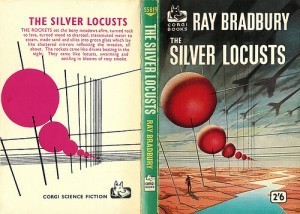

I’ve alway been a little suspicious of writers who claim to be ‘using’ genre as a way of doing something more mannerly than actually writing a thriller or science fiction book or whatever. I don’t ‘use’ genre or ‘adopt its tropes’. I write as I read. I am in this corner with the Portal gun, and I can make a hole in the world and come out anywhere. Literature can appear in any genre – and I’ve often thought the literary works in genre are particularly delightful because they’ve discovered their own voice by finding their own orbit between competing gravities. It is often a voice with a flavour of freedom, and sly charm, and friendliness. When you hear it you feel that the writer is sitting down at the reader’s table. Raymond Chandler, Stephen King, Robert Louis Stevenson, Georgette Heyer; Ray Bradbury – all have this in spades. They are very attractive writerly personalities to be in the presence of.

The morality in horror stories is often punitive and conservative – if you don’t stay home you’re punished; if you’re a loose woman you’re punished; if you don’t respect other’s beliefs, you’re punished; if you don’t respect the story, you’re punished. Because of this, horror can be the most misanthropic genre. But what I had set myself to do was write a people-loving horror novel. The threats were going to be inhuman, for openers, but my story wasn’t going to be pitiless towards human failings. Nor was it going to reward virtue – except in the sense that some of the characters do work out that the last hope they have left to them was to not let others down. My horror novel was explore the heroism of stoicism, honour, and valour – all of which may seem remote as stated values, and old-fashioned. But, you see, I’d been watching these very things sustain my mother through the loss of her power of speech, of her strength, her mobility, her sense of taste and smell, her eyesight, her ability to breathe. And, in the end, if Mum hadn’t been treated with such tender sympathy by her grossly underpaid caregivers she would even have lost her dignity. So, for instance, when Mum was diagnosed the doctors had said -had promised – that she’d keep her bowel and bladder control. That, and that she’d be alert, intelligent, and herself right up to the end. They were right about the second thing, but not the first. Motor Neurone Disease attacks the control of voluntary muscles first, then the involuntary (it is paralysis of the diaphragm that kills its longest surviving sufferers). The gut has involuntary muscles. Peristalsis is involuntary. But the rectum is a voluntary muscle, and, in the end, Mum wasn’t able to control hers. The point I’m making here is how everyday and unexceptional horrifying things actually are. My characters in Wake, baffled by how little they can do for themselves and each other, and by how sequestered with their trials they are, with no rescue on hand, are just me. They are just us. And it is my observation that many people faced with tough shit, cope bravely.

But there are many ways to fail – and in my novel the failures were never going to be the archetypical horror story’s fatal errors of too little chastity or too much curiosity, they were going to be real-world failings, some of which are the dark side of virtues – like an exclusive and inflexible devotion to a regimen whose aim is bodily perfection. This is the kind of loose thread of a person’s character that the novel’s monster picks and pulls at. This is the threat – delusion, solipsism, selfishness, cowardice, despair. And that isn’t to say that the monster and its acts are allegorical. It’s a real monster. (All monsters are real, like all angels are terrible.) The things that were scaring me were psychoses in people near to me, the fatal offhand malice of the man who killed my brother-in-law, and my mother’s terrible disease. That, and my own shrinking inadequacy in the face of it all. Real things and feelings just then best expressed as horror – as mad acts, bloodshed, being trapped, having no help, having crushing responsibility, and the gradual closing down of all means of doing any good.

November 21, 2013

My History with Horror

I will begin with withered leaves blowing through an empty fairground, tent canvas gulping and gulping, and the seats on the dark Ferris wheel creaking, rocked by ghostly fairgoers. By the pricking of my thumbs, something wicked this way comes.

I will begin with withered leaves blowing through an empty fairground, tent canvas gulping and gulping, and the seats on the dark Ferris wheel creaking, rocked by ghostly fairgoers. By the pricking of my thumbs, something wicked this way comes.

My first encounter with horror was a book of ghost stories I sneaked from the bookcase in my Uncle Keith’s bach, and a story which kept me feverishly awake as one of its protagonists was also up all night, disturbed by whispering, a breath blowing on his ear through ‘the chink in the wall’. I write ‘his bed’, but want to write ‘the bed’, smudging the story’s shades into my own, because, more than any other kind of reading, ghost stories work that way. They chase you when you’re alone and undefended, as we all are when worn out by wide-eyed, wakeful terror, when we’re only eight years old, in the top bunk, and the hot lights of the poultry farm hatchery on the other side of the hedge are crawling on the ceiling and bedclothes like larvae of daylight, while dawn is still hours away. I wish I could recall the title of that book. An omnibus of ghost stories. Omnibuses were things you got on innocently and which carried you off along some dark road with tight corners and bluffs where buses shouldn’t go, in a countryside of stark grazed hillsides with black macrocarpa shelter-belts.

Close to that time there was also Doctor Who, and the Macra Terror, a crablike monster lurking in ‘the old shaft’, waving its claws and blinking its bulbous eyes. (The brainwashed inhabitants of the planetary resort were almost as scary as the monster, with their crisp, positive voices and satin bandmaster suits.)

At eleven I encountered Ray Bradbury. He could be very scary – it was his haunted fairground. And even when things turned out all right in his stories because the boy whom no one would believe was finally able to convince someone that there were screams coming from the empty lot. Even then, when they dug up the woman in the box, and she was saved, the boy vindicated, and the slighting adults chastened, you were still left wondering what it was like for that woman afterwards, and how would she feel if she woke up with her face two feet from the ceiling in the top bunk?

At eleven I encountered Ray Bradbury. He could be very scary – it was his haunted fairground. And even when things turned out all right in his stories because the boy whom no one would believe was finally able to convince someone that there were screams coming from the empty lot. Even then, when they dug up the woman in the box, and she was saved, the boy vindicated, and the slighting adults chastened, you were still left wondering what it was like for that woman afterwards, and how would she feel if she woke up with her face two feet from the ceiling in the top bunk?

So, there was Bradbury with his mists and autumn and leaves that weren’t leaves blowing through ruined Martian cities. There was Disney’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, the reliably frightening Doctor Who, and all the other omnibuses and anthologies – Irish, German, Latvian, Japanese ghost stories. And there was Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte and Robert Wise’s film of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting. (Only my inconsistently prohibitive parents would have thought to exile Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination to the top shelf of the hall cupboard, and let me watch The Haunting.)

I’ll jump a few years then, to my teens, and The Legend of Hell House. After I’d seen the film Dad pointed me to Richard Matheson’s novel on which the film was based. Dad admired Matheson the screenwriter, especially the beautiful transcendence of the final monologue in The Incredible Shrinking Man. But Dad was contrary, he loved science fiction and despised fantasy. For him horror was in an uncomfortable territory between the two, and the virtue of Hell House was that it turned out that the evil guru Belasco’s ghost had an electro-magnetic rather than spiritual existence, and that his spirit survived with his enthroned, mummified form in a lead-lined room at the heart of the house. The scientist investigating the haunting was gruesomely dead, but vindicated. There was a charge for me too in that, something that sat beside Dad’s approved of ‘science in the fiction’, and that was the spectacle of people negotiating their fear with thought and problem solving. It was meaningful to me not because it made these victims of the supernatural evil more hopeful, but because it made them more human – more valuable, more energetically alive, and more comprehensively doomed in the face of the story’s malignancy.

I’ll jump a few years then, to my teens, and The Legend of Hell House. After I’d seen the film Dad pointed me to Richard Matheson’s novel on which the film was based. Dad admired Matheson the screenwriter, especially the beautiful transcendence of the final monologue in The Incredible Shrinking Man. But Dad was contrary, he loved science fiction and despised fantasy. For him horror was in an uncomfortable territory between the two, and the virtue of Hell House was that it turned out that the evil guru Belasco’s ghost had an electro-magnetic rather than spiritual existence, and that his spirit survived with his enthroned, mummified form in a lead-lined room at the heart of the house. The scientist investigating the haunting was gruesomely dead, but vindicated. There was a charge for me too in that, something that sat beside Dad’s approved of ‘science in the fiction’, and that was the spectacle of people negotiating their fear with thought and problem solving. It was meaningful to me not because it made these victims of the supernatural evil more hopeful, but because it made them more human – more valuable, more energetically alive, and more comprehensively doomed in the face of the story’s malignancy.

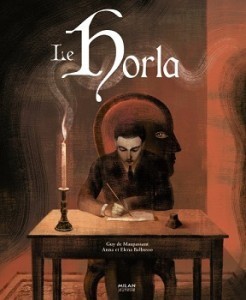

In my teens I especially loved stories where someone waits in dread. M R James’s ‘Whistle and I’ll Come to Ye Laddie’. Bram Stoker’s ‘The Judge’s House’. And, most of all, Guy de Maupassant’s ‘The Horla’ – one of those ‘This manuscript was discovered after the death of…’ stories, of which The Blair Witch Project is a direct descendent. No one is left alive to tell the tale, except it is already told, there’s this mad journal, this mad film, and what are we to make of it?

The other given of horror, besides menace, is madness. Not so much madness from the outside: the distressing spectacle of insanity, of madness as a problem to the sane. (Though I will always regard Lucy Westernra’s simultaneous physical failure and sustaining mania, and her friends’ and parents’ misery, as the most terrifying things in Dracula.) No – it’s the loneliness of madness that is at the heart of horror. Think of the demented hero of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, screaming ‘They’re already here!’ at people on the highway, peering with fear into every face, in deep doubt about who can be trusted and who cannot, who is human and who is not. Think of ‘The Horla’, a story which takes the form of the journal of a man who went mad and burned his house down, killing all his servants, because he had come to feel, over a series of darkening days, that he was never alone, even in an empty room. To feel that a presence was ghosting his steps, reading the pages of his journal when his back was turned, drinking the milk on his bedside table, bowing its head beside his to smell a rose, enjoying his life as he was, day by day, less able to. I read ‘The Horla’ when I was fourteen and understood why I was frightened by this invisible stalker with unknown intentions towards the story’s protagonist. I was scared of what scared him. But, without fully understanding why, I was also deeply frightened by the protagonist’s dread itself, by the way in which his life became strange to him, the tale’s stain of depression and slow estrangement from self. (Maupassant’s story was written under the influence of a mood of alienation from things – the beginning of a mental dissolution from the effects of syphilis on the brain.)

The other given of horror, besides menace, is madness. Not so much madness from the outside: the distressing spectacle of insanity, of madness as a problem to the sane. (Though I will always regard Lucy Westernra’s simultaneous physical failure and sustaining mania, and her friends’ and parents’ misery, as the most terrifying things in Dracula.) No – it’s the loneliness of madness that is at the heart of horror. Think of the demented hero of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, screaming ‘They’re already here!’ at people on the highway, peering with fear into every face, in deep doubt about who can be trusted and who cannot, who is human and who is not. Think of ‘The Horla’, a story which takes the form of the journal of a man who went mad and burned his house down, killing all his servants, because he had come to feel, over a series of darkening days, that he was never alone, even in an empty room. To feel that a presence was ghosting his steps, reading the pages of his journal when his back was turned, drinking the milk on his bedside table, bowing its head beside his to smell a rose, enjoying his life as he was, day by day, less able to. I read ‘The Horla’ when I was fourteen and understood why I was frightened by this invisible stalker with unknown intentions towards the story’s protagonist. I was scared of what scared him. But, without fully understanding why, I was also deeply frightened by the protagonist’s dread itself, by the way in which his life became strange to him, the tale’s stain of depression and slow estrangement from self. (Maupassant’s story was written under the influence of a mood of alienation from things – the beginning of a mental dissolution from the effects of syphilis on the brain.)

This is my history with horror. All these things taken together. A vortex formed by the rattling wind from Ray Bradbury’s haunted fairground, which spins through it all. A vortex that takes in the Macra Terror; sweet Charlotte and her axe; Roderick Usher and Emeric Belasco; rapt, wrongheaded, ghost-haunting Eleanor Vance; the judge’s house, dead Martians, people buried alive, and an invisible something bending the steel stairs of Forbidden Planet‘s spaceship as it climbs clandestinely inside. A vortex takes in the horla, and every other monstrosity who, for whatever inscrutable reason, chooses to put its mark on you. Every easily offended, grimly playful monster that comes to show you the consequences of your hapless transgressions. Every monster – hidebound and punitive – enacting revenges from old stories that are nothing to do with who their victims really are. That kind of monster, or one that is sad and deathly, lonely and cold, like Bradbury’s Martian ghosts, or Tove Jansson’s Groke – the creature who comes in her halo of frost, fixes her pale, hungry eyes on the lamp and shuffles nearer, ever nearer, until that lamp goes out.

This piece first appeared on the Booknotes Unbound website

October 13, 2013

Where Wake Came From

As an blogger’s introduction to Wake I’ve decided to transcribe what I wrote in my journal some months into my writing the novel. I had returned to it after a break, finally seeing what it was doing and what it might be for.

I have used letters or a long dash to replace some names that naturally appear in full in the journal. I’ve fixed my spelling but have left the language as headlong as it tends to be. ‘Duncan’ is my husband’s brother Duncan Barrowman, who was deliberately hit by a truck in Rarotonga in May 2009 and died some hours later, leaving behind a wife and four children. The man driving the truck was convicted of manslaughter. My mother was diagnosed with Motor Neurone Disease in June 2009. She died in January 2012. There was more in the journal about the biographical ‘madness’ connections, but I left it out because it all needs a fuller context.

From my journal. 14 September 2009

I’m writing something new that feels by turns completely unfitted to my talents and like going west in a plane, chasing daylight, when the light stays ahead and the night is a dark river you’re rocking along in. The new thing is a horror novel based on a story from the game – naturally – a plot I explored twice, with M and then later with Sara. M and I did a version years back, the late ’90s, inspired by a dopey horror movie with Ben Affleck and Peter O’Toole set in a town full of corpses and ghosts beset by an ancient Lovecraft-type monster.* We liked the film’s set-up, but not its ramped up middle and end. Our version had an insidious monster and a desert town and apparently straight roads that magically doubled back on themselves so that one character, a road-racing cyclist, didn’t have to think about turning at the town’s limit, but could just peddle on in the trance of his obsessive exercise regimen, except when waylaid by the whirlwind dust devil monster. I remember the whirlwind was only a symptom. I don’t remember a whirlwind in the film. I think there was a big black cloud full of lightning which Peter O’Toole shouted at it like King Lear.

In the journal there follows a plot summary with several spoilers for Wake. I left that stuff out. Though, reading it, I was interested to see just how much of my very first version of the story I had used in the novel, especially how the trapping device worked (I had a ‘barrier’ in early versions of Wake, but reverted to the first game’s ‘inertial field’ without remembering that this was what we’d done!)

After the omitted spoilers the journal goes on:

… sometime later – 2000, I think – I floated the basic plot in front of Sara when we were holidaying at Hukawopa on Tata Beach and were trying to come up with a senario. Sara didn’t feel like deserts, so we set our version of the story in a small coastal settlement, somewhere in California. One character was a fisherman, another a police officer, another a mysterious reclusive man in black. Someone else was a crim in the Witness Protection Program, and another person appeared to suffer from Multiple Personality Disorder. The survivors all holed up in the local spa. Anyway, a lot of this is useful to this novel. But the novel’s coastal town is NZ, the fisherman is Maori, the sportsman is a sportswoman, there are no mafiosi, or men that stare at goats. It’s a science fiction story but it starts as horror because I just sat down one afternoon in the chair in the corner of my bedroom and began writing scenes of mayhem because, for a start, I wanted to see if I could scare people. Then I kept on with it despite worrying that it was too genre, and a bad fit for me, because I discovered that writing it was a way to explore the experience of people in a catastrophe and because I feel like I’m in one. — has been sliding into craziness for years, but suddenly it’s acute and Mum’s desperation about it even more so. Duncan was killed, and now Mum has this horrible disease. I’m not in my Mum journal so I’m not going to go into detail. Which is nuts. Why am I trying to be tidy-minded about my feelings? I’m writing horror because I’m horrified, and blackness is pouring out onto the page – horror and doubt, about how to think, what to do, how to help. Horror and doubt and hopelessness, but not despair. Because life may be a vale of tears and I’m trying to get some of that down, to one side of my own biography, but informed by it. But if life is a vale of tears, people are mostly good at heart (as Anne Frank said). My people in this story have to to try to keep doing their best (as I am and Fergus is.) When Hurricane Katrina happened there were hundreds more folks with boats rescuing people off the roofs of drowned houses than there ever were looters. So this book has a catastrophe, but it’s also about the struggle to stay useful and good, and what’s encouraging in that. And my catastrophe is made up because I don’t like books that get their dignity by being about real, terrible historical events – ‘catastrophe porn’ books about the vast engulfing human-engineered horrors of history – the holocaust, other historical massacres and atrocities (books not written by survivours or their children, people who lived daily with what happened) books that that get taken seriously even when they’re quite glib – the evil humans do discussed with big noises and gestures. I guess maybe I’m more interested in trying to talk about the evil people endure (old age, illness, failure, and casual and scarcely meant violence, like that of the guy who killed Duncan). I want to write about the narrow vale where you have to take your turn among others crying and trying not to cry while the valley fills with tears and won’t drain till we’ve all drowned and the great logjam of our bodies has dissolved and gone.

The novel is also meant to be a kind of desert island story. Something between Then There Were None and every other desert island story. So, a book about being trapped with mystery and malevolence, and trying to get by, and get on. A story with the pleasure of problem solving, about ingenuity and work, about morale and social cohesion, and about loss and futility. This, from my mum journal: Futility isn’t only our fears about the future, it also makes itself felt retrospectively – it’s seeing how futile our past hopes were.

Why a monster instead of human evil? It’s not exactly the case that I decided not to think about the evil people do. I was thinking about it, but each word separately as well as in concert. The man who killed Duncan did so impulsively, spitefully and, in the end, impersonally. Impersonally because he simply aimed his truck at one person in a group of people after having argued with others in the group. Duncan hadn’t spoken to the man, or even been awake during the argument. So the ‘doing’ part of the evil people do was on my mind – the question of volition, a terrible thing carelessly done, malice directed nowhere special, just somewhere, and the disaster of that. I was thinking about people who make others suffer without having any sense of who it is who suffers – no imagined antagonist against whom they have even a feebly motivated or wrongheaded grievance. The act is empty, but the consequences full.

I was also thinking about the spectacle of madness. About the slide into madness through small distortions in perception, small unconquerable anxieties. A gradual slip into resentful and self-congratulatory isolation. I was thinking about how people lose themselves – that is, they lose themselves in proper relation to others – that kind of madness. Like always hearing slights in others’ addresses to us. Or that stoned sense of losing track of something fundamental, like how many people are in the room with us when the doors are closed and haven’t opened to admit anyone new. That business of setting the table for one person too many (I remember doing that, and feeling sad every time I did after our cousin Steph who lived with us for a year when I was about 14, had gone elsewhere). Remembering someone missing. Conjuring someone who should be there, who might be there, and isn’t (or is, but isn’t recognisable). Or that business of looking into a mirror and suddenly seeing signs of illness, of turning an ear to your own body and hearing some kind of internal cellular conspiracy. The small things that get on top of people and, cumulatively, hammer them into the ground.

* The 1983 novel the 1998 film was based on is Dean Koontz’s Phantoms. Stephen King has said Phantoms was one inspiration for The Dome. (Another was The Simpsons movie). This is all part of the great cross-pollination of horror. I’m going to write about that in a piece I’m doing for the Book Council of NZ’s magazine, Booknotes, which I’ll post here once it has done its dash in print.

August 3, 2013

Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries

This is my speech for the launch of Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries at Unity Books in Wellington, 3 August 2013. ‘Fergus’ is Fergus Barrowman, my husband, and Ellie’s New Zealand Publisher. I was honoured that Ellie asked me to launch her novel.

I have a habit from my student days of writing page references and brief notes on the flyleaves of books when it’s a book I have to say something about. When I first started reading The Luminaries I was conscientiously doing this with my launch speech in mind, but, once I came to write the speech I discovered I’d left off my note-taking at page 262 with a brief ‘very funny’. This was the point where it completely slipped my mind that I had to react in any articulate way to what I was reading, and probably began to either annoy—or possibly please—Fergus (on the brown couch reading manuscripts) with my Ah Ha! and Oh No! and the Bastard! and my general squirming around finding comfortable positions so that I could keep on lying there hour after hour, balancing the book on its edge and tormenting its spine. Thus proving two things: Victoria University Press’s hardback edition is a robust piece of bookmaking, and that Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries is, first and foremost, a gripping and infinitely surprising mystery novel. This high degree of suspense and sheer reading pleasure is the cumulative result of all the novel’s other astonishing richnesses. In equal measure, the beauty of its writing, the devilish intricacy of its plot, its and loving interest in human minds and motivations, and it’s extraordinary mathematical architecture. And, of course, all these virtues are interdependent.

My plan for this speech is to try to describe what the experience of reading Ellie’s totally one of a kind novel was like for me.

The Luminaries is a book where things move and are altered. All but one of the characters is from elsewhere—not Hokitika and the west coast. And Te Rau Tuwhare, who most naturally knows how to live where he is, keeps trying with puzzled patience to correct various of the book’s fortune-seekers in their attitudes to what is valuable—though, notably, he agrees with others about who is valuable. Ellie’s characters are seeking their fortunes and trying figure out how to live where they find themselves, with each other, and with themselves. Many are transmuted in the course of the story—in ways that are echoed by the gold of the contested fortune that is so central to the plot. Gold mined in Otago, siphoned from a safe, smuggled, hidden, sewn into garments, seeded back into a dry claim, panned again from gravel, then smelted and stamped—that is, finally named and set—only to be stolen again, hidden, found again, and fought over. And believe me I’m not telling you much because, no matter what order it happens in, we don’t discover it that order. Because, whether we are learning about gold or people we are shown that their eventual shapes have no greater interest, or currency, than all their successive forms. Everyone and everything changes. Solitary people are befriended. Law-abiding people commit crimes. People are gulled, then undeceived. They fall, and are returned to innocence. And the gold is no simple allegory. It’s only one of the chimerical things the reader has to keep their eyes on. There are letters, sea chests, lost and hidden people, people in sea chests, guns, bullets shot from guns that end up in the darnedest places. The novel’s plot is like a shell game played with dozens of shells, some of them covering startling compressed wonders like a magician’s silk flowers. Understandings are bundled up in the plot, then burst into sight at ten times their expected volume.

Some of my favourite things: Te Rau Tuwhare being forced to keep a tangi’s vigil at some distance from the body—and his thoughts about that. Actually, lots of characters’ thoughts about lots things. The justice’s clerk, Gasgoine’s strange loving memories of his dead wife, and her burial at sea. The whole scene in the little gold diggers shack on the gravels of the Arahura river with two Chinese men who don’t quite approve of one another, one with some English, the other with very little, a blustering ridiculous bully, a well-meaning and slightly timid young man, a gun, and an excitable dog. Or the broiling tenderness of the dark and seething Edgar Clinch when he thinks of his preparations for the prostitute Anna Wetherall’s bath night. Gasgoine slyly banking the villain Francis Carver’s good will by explaining the niceties of maritime insurance while, at the same time, gathering information and getting a measure of the man. Ah Sook’s terrible first weeks in the port of Sydney. The seance and the soirée leading up to it. And I loved it every time anyone emerged from one of Hokitika’s tent-like timber buildings with ‘breathing’ scrim walls to see the mountains or the the harbour bar shining in glimpses whenever the theatre curtains of west coast weather part. And all of it so alive that I felt fed when the characters were having breakfast, drunk when they were drinking, wet when they were rained on, and that I’d taken a wound when one of the characters was betrayed—as if I, the novel’s reader, was also its astral twin.

The narrative voice of this novel is perhaps its greatest asset—a masterful ‘we’ as changeable as the contested gold. Sometimes patient and reflective, especially in describing how the characters see themselves. Often graceful or brisk—in dialogue especially each character utterly distinct and alive. And then there’s the deft turns in tone, which simultaneously remind you you’re being told a story, and that the story matters, while making feel comfortably trusting of the author and that you’re in her very good hands. These deft turns are often funny, take this, from page 262, the occasion of my last fly leaf notation:

‘He began speaking, for example, by observing that upon a big tree there are always dead branches; that the best soldiers are never warlike; and that even good firewood can ruin a stove—sentiments which, because they came in very quick succession, and lacked any kind of stabilising context, rather bewildered Quee Long. The latter, impelled to exercise his wit, retaliated with the rather acidic observation that a steelyard always goes with the weights—implying, with the aid of yet another proverb, that his guest had not begun speaking with consistency.

We shall therefore intervene, and render Sook Yongsheng’s story in a way that is accurate to the events he wished to disclose, rather than to the style of his narration.’

I think that, ultimately, there’ll be a lot written about the decisions Ellie has made regarding the structure of The Luminaries. Astrology is a remarkable choice. An ancient artificial systems for making sense of human nature and what happens to us. The Luminaries is a book shaped by the stories in astrology—stories about birth, timing, and fate. The novel’s chosen system stands in for nature, something already present outside what the characters’ social circumstances make happen to them. Astrology comes with it all kinds of imagery and metaphorical significances that relate to time-honoured attempts to find shapeliness in life stories. Astrology provides Ellie with templates for the temperaments of her 12 good men (or mostly good men). Temperaments separate to the biographies shaping each one’s attitude and behaviour (almost as if Ellie wants to let the nature/nurture argument about character play itself out in a zodiac mask.) Also the novel’s astrological/golden mean design gives it a disciplined mathematical structure that creates an enormously pleasurable sense of pace. Because the book is in 12 parts, and each part is half the length of the one before, as it goes on the story accelerates—very like accelerating montage, that great tool of film directors. The story begins gradually, like the tide coming into a wide estuary, then it quickens, like the tide coming into a wide estuary, then it’s a river, then it’s a river in flood, and in the end its swooping like the albatrosses that first bring its lovers together. The pace of the novel is a miracle—mathematical, but not mechanical. It’s the mathematics of nature, and once you’ve surrendered to The Luminaries and you’re in its grip you’ll feel that pace, and its poetry, in your body, in your bones and blood.

July 25, 2013

My Interview for YALSA

This is an interview I did for The Hub website. Julie Bartel provided the questions. It is mostly about my teenaged self.

One Thing Leads to Another: An Interview with Elizabeth Knox

May 28, 2013

Letting in the Ghosts: Why certain things are in Mortal Fire

Southland, showing main cities, rivers and mountain ranges. A detailed map of the Zarene Valley and environs with be added in later post.

I keep producing blogs that are highly finished pieces of writing, like essays. Which isn’t to say I labour over them, more that I keep feeling each has to be a thing in itself. But that’s not what blogs are for. So this one is just a few thoughts about how I came to write Mortal Fire and why some of the things in it are in it. And if it does happen to organise itself in composition then yay.

To coincide with Mortal Fire’s publication in the US I’ve been writing a few guest blogs. They’ll appear over the next few weeks, and I’ll post links. Those guest blogs talk about stuff I won’t cover here. So that you know it is covered – or at least addressed – I’ll give you the subjects. 1) My kind of Heroine 2) Invisible Monsters 3) How using an exotic – to Northern Hemisphere readers – location in a fantasy novel creates ‘two levels of invention’ in the work. And 4) How, when writing, to get out of your own way. Since I’ve promised blogs on those topics I will try not to stray into them here.

The keywords websites use when they first begin characterising a book are a pretty good guide to the things those commentators feel readers will find remarkable in that book. It’s all factual stuff of course. So: World War Two, mining disasters, beekeeping, South Pacific, polio… As opposed to: identity, loyalty, crime and punishment, family, heritage, theft… I think I’ll do what the keyword formulas do and ignore the abstract nouns, and tell how some of the other stuff comes to be in the book.

David Larsen, interviewing me for The Listener, wanted to know why I’d set the book in 1959. It’s a big decision with a huge input into the flavour of the book, but it was one I came to kind of expediently – although very happily. I’d decided one of the defining characteristics of my protagonist, Canny, was that she had a mother who was a heroine. And that Sisema was the kind of heroine who becomes more celebrated as time goes on, because her story is one that her Nation’s identity is forming around. I decided that this would work best if Sisema was a war hero. That immediately led me to World War Two and a Pacific island occupied by Japan. I’m not going to tell Sisema’s war story here, but this decision gave me a possible date for Canny’s birth. I wanted to write about a sixteen-year-old, and my addition gave me the year 1959. To my amused exasperation one mostly very positive review on Goodreads worries that Canny sounds “young for her age compared to US teenagers I know”. Perhaps – the reviewer writes – that’s because she comes from this New Zealand-like place and maybe teens grow up slower there. And I’m reading this and going like, “Um – it’s 1959.”

Beekeeping. I wanted to set my story in a pastoral paradise. The Zarene Valley is kind of based on valleys now beneath Lake Dunstan. Those now-drowned valleys circa 1981, when I was down there with my sister and some friends (touring about in a 1957 Plymouth station wagon). Back then there were no vineyards, and more kiwi holidaymakers than tourists. 1981 is pretty much equidistant from 1959 and 2013, but it was more like 1959. Also I felt that I was in some ways writing the book for my editor, Frances Foster. I was thinking of her as a first reader. And I remembered how, when I met Frances at the Disney Convention Centre in 2008, when I was there for the American Library Association Conference, she told me about being a child visiting her grandparents’ farm in Anaheim, back before Disneyland bought up all the land. I remember her description of the pastoral paradise now under the theme park and hotels and highways. So – old Anaheim, and the apricot orchards under Lake Dunstan, are what made the Zarene Valley.

A Mining Disaster. The disaster was in Mortal Fire before Pike River. I considered taking it out, but then I thought about all the mining disasters in New Zealand – a whole history of them – and told myself not to be so shallowly presentist, and, besides, the Bull Mine Disaster is historical in the novel (1929). Where the novel’s mining disaster came from is quite interesting. When I was first planning my novel Daylight – a book which gestated between 1997 and 2001 – I had this high-concept idea about a small society of vampires who, in order to “give something back”, had decided to use their strength, resilience and lack of any need for oxygen to become a crack underground rescue team. I talked to a cave rescuer in Motueka, and had an email correspondence with one George Muise, a Mine Rescue Captain from Nova Scotia. I was writing to Mr Muise in 1997 (and only printed out a few emails, the rest were deleted with my account once my time as Writer in Residence at Victoria University came to an end. There were also many emails between me and my US agent about the sale of The Vintner’s Luck. I printed some out. I have these things, and my handwritten ms, but I’m not feeling any archive love…). George Muise was the leader of the first rescue team that went into the Westray Mine after a catastrophic methane gas explosion in 1992. His team went the deepest and recovered a number of bodies. George Muise described it all to me. His namesake in Mortal Fire – George Mews – gives Canny’s brother Sholto a tour of a mine while telling him what Bull Mine was like when he led rescuers into it thirty years before. That chapter is Mr Muise speaking, and the report of the Government enquiry into the Westray disaster, a report which I ordered, in its four volumes, from Nova Scotia, in 1998. I’d read that report – so I wasn’t really in the dark about Pike River when it happened. I wish the right people – those who weren’t mere novelists – had had the Westray report sitting in their bookshelves.

Canny’s pacific heritage. Though the fact Canny is a Pacific Islander first rose out of my wanting her to have a mother who was a civilian hero – a mother who was a teenager when she did her brave things – there were other reasons for Canny’s Pasifika heritage. Reasons mixed up in complex ways with some very personal matters. And not just personal to me. More personal to other family members. But I’ll give this a go. My sister-in-law is Tongan, and my nephews and niece south Auckland Pasifika kids. I’m very fond of the them, and, I hope, have been slightly useful to them since their father, my husbands’ brother, died. What isn’t complicated is my affection for them, and my curiosity about them and their lives (very different than my life). The kids are great conversationalists when they get going, especially the two older boys, and I’m sure Auntie and Uncle exasperate them with questions about how school is and whether they’re playing rugby (their Dad used to coach kids’ teams at Manukau Rovers), but sometimes we hit on stuff we have in common, like the fascinating behaviour of certain family members, and – more me than Fergus – TV, films, books. I’m all over that stuff like a happy dog. Anyway – there’s so much not to take for granted about the relationship that I spend quite a bit of time thinking about them. About what kind of people they are and how they’re coming along. Their father, Duncan, was killed, and the man who killed him went to prison for manslaughter. Duncan died in Rarotonga (where he was with his team on a Golden Oldies rugby tour). The trial was over a year later. That’s my only visit – so far – to a Pacific Island. I thought a lot about that visit and that time. I loved Rarotonga and the people we met, the strangers who talked to us about what had happened. Being at the trial was difficult and sad, but also very vivid and somehow a satisfying experience. It was – the whole thing was – proof of a something about life, and people, that I think most of us know but don’t always feel, and that is: for all that there are careless people capable of callously destructive acts, most people make things, and mend things, and are quiet supporters of the world’s greatest and most ordinary cause – the long cause of care.

All of that went into Mortal Fire, a knot of loyalties and pity and sympathy and realisations and enchantment. Also, I had a thought I’d never really had before. And it became Mortal Fire‘s secondary theme. (The primary theme is how you can’t always save people, or spare them. The two books I wrote between 2009 and 2012 have that, mostly because of my mother and her Motor Neurone Disease – which among other things is an exercise in being able to do less and less to help all the time. But because of Duncan too, and my husband’s family, especially the kids. Because of many nights lying awake, thinking in desperation and worry, ‘What can I do? What can I do?’) Anyway – this was the secondary theme-inspiring thought I had, and when I had it. It was about our desire to punish people who harm us, and what that desire does to us. We were in Rarotonga, attending the trial, and all hoping for a guilty verdict. The idea that the guy who did it might get off was awful. (It wasn’t very likely – but with awful possibilities the odds always seem shorter than they are.) In the hours and days when the court wasn’t in session we looked around the island. Once when we were driving on the inland ring road we passed a sign pointing to the Cook Island prison and went to take a look. We sat in the car for a short time looking across a humpy green field at the long, low building. It had barred windows, each with a single horizontally-hinged shutter. The shutters were propped open. The sunshine was bright and hot and the prison’s interior was just a blackness. Now, I might have wanted the guy to go to prison, but right then the thought of putting any fellow human being in that place and making them stay was quite hard. Or serious. Or just real – it made my desire for this man’s punishment something I had not just to feel, but to be responsible for. So, the trial ended and I came home and I went on thinking about that moment, and my own piteous human hesitation, a piteous human hesitation which the man who drove his truck into Duncan failed to have. Anyway – it wasn’t that I stopped feeling angry and vengeful, or even thought I should, only that I came to understand that my human hesitation was a far, far more valuable feeling (I mean not just to me – but in life, in the world). And some of this found its way into Mortal Fire.

That’s it. That’s why my this and that is in the novel. I don’t think writers look around for things to put into books, like everyday cooks staring at the shelves of their pantry. I’ve always loved this quote from Emily Dickinson: “Nature is a haunted house – but Art – is a house that tries to be haunted.” Dickinson gets the sense of there being something wrongheaded in what art wants for itself. I mean, who wants to live in a haunted house? But I know this: though I don’t hold a seance and invite the ghosts, I do let them in when they appear at my doors and windows.