They Come to Class

After reading Jolisa Gracewood’s post School Bully on her blog Busytown —an impassioned argument about the wisdom of teaching for testing—I’ve had a number of conversations about the direction and future of education. This guest blog, by a highly dedicated (and now despairing) teacher in the tertiary sector, is the result of one of those conversations.

They come to class, most of them. They turn up on time, or late, and queue after the end of teaching to get their names ticked off the roll. There’s no attendance criterion, but turning up seems to be taken as the principal work of doing a subject, which is why the weeks before the start of semester are so hectic, with everyone jockeying for the best timetable pattern they can get. But the day after results for the first assessment are released the round tables in the blending learning space have two or three people at them, not the usual five or six. Even though the day’s teaching is to help them with their next assignment, it is resentment, not practicality, that wins out.

They come to class, most of them. They turn up on time, or late, and queue after the end of teaching to get their names ticked off the roll. There’s no attendance criterion, but turning up seems to be taken as the principal work of doing a subject, which is why the weeks before the start of semester are so hectic, with everyone jockeying for the best timetable pattern they can get. But the day after results for the first assessment are released the round tables in the blending learning space have two or three people at them, not the usual five or six. Even though the day’s teaching is to help them with their next assignment, it is resentment, not practicality, that wins out.

It is the 7th week of semester. Once again the girl who sits with the girl with the straightened hair, the girl whose phablet is always in or near her hand, has not brought her book of essential readings to class. We have this routine. I lift my eyebrows, and say, ‘So you haven’t got your reader?’ ‘Do I need it?’ she asks, and I walk to the next table, laughing. Today, once again, most of them haven’t done the reading, and when I play the video lecture pods quietly in the background, the girl who never brings her unit reader points at the woman on screen and says, ‘Who’s that?’I mime a button being pushed, an ejector seat going up. ‘Massive fail,’ I say, ‘that’s the other lecturer. As everyone knows.’ I resist looking around the room: there were fewer laughs at the ‘Who’s that?’ than I’d expected, which means there are other people who haven’t watched the lectures, and don’t know what’s going on. Other people who will probably write anxious emails to me the night the next assessment is due, saying, ‘I don’t understand the instructions. Tell me what I have to do.’

I did tell them what they had to do at the time—when we were doing that week’s stuff. They were sitting in class, they were present—most of them—when we did the practical exercises, and ran through the conceptual terms. They sat at their round tables, staring at me as I stepped them through what their portfolio was, and what they had to do, what we expected to see. They were right there when I took them through it. Conversation analysis maybe, or semiotic analysis: Charles Sanders Peirce, he of the long beard and the overblown typology of signs: 60,000 separate elements. But the coarse makes it simple, going over Peirce’s trichotomy of signs: index, symbol, icon. Three is ok. Three is good. The holy trinity of signs. And when the assessment comes in, I find I’m marking one about Peirce’s tracheotomy. The word recurs. On the third repetition I write in the margins: ‘Did he do it with the casing of a ball point pen?’ realising, as I write it, that this is what being defeated means, and this is what I’ve come to.

Most of our students in the Bachelor of Arts are just travelling through—the BA is the gateway to a Masters of Teaching. They are training to become teachers, primary and secondary. I wonder a lot of the time now what they’re going to teach, what stuff of the world is in them that they’ll draw out for the children in their charge. Because they are not learning much here—they come to class, and that’s it. They don’t read. They don’t come to lectures, or watch the lecture pods that we’ve made, not like filmed lectures, but like film, they’re so highly produced. Most of them don’t watch them. And if I show an excerpt of a film in class and ask a question about some shot, or section of dialogue, most of them can’t remember it. Even if I’ve paused the video just after the line in question has been spoken.

One of my colleagues was teaching his First Years about metaphor. Whether its about Judy Garland and the musical or the behaviour of the gerund this man is as clear and engaging a teacher as you could ever want. That week he was teaching metaphor, by example and analogy, given that that’s the logic of metaphor. Loving a good show tune, he plays them Barbra Streisand’s ‘Evergreen’, then he asks them to unpack the song’s structure of metaphor. But there is no-one in the class who knows that there’s a type of tree called ‘evergreen’.

This is the problem of teaching now, not what to teach, nor even how: it’s how to manage the impossibility of teaching when there is nothing to teach to; nothing to hang the ideas off, no language to build on. Not even stories commonly shared. I use the Titanic a lot, because nearly everyone knows what it was, and that it sank. It is my principal teaching analogy now: that unsinkable ship, that wreck.

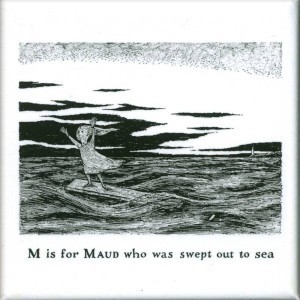

It used to be that before the start of a semester I’d have teaching nightmares. That I am late to class, that the tutorial room is in a building in another campus, that the tutorial room is in mid-air, above my head, with no way up to it. Those dreams come more frequently now. In my most recent, I am running to class but get caught in a crowd of people moving in another direction, and when finally they disperse I find I’m on a ferry, and there’s a widening expanse of sea between me and the building in which I teach.