Elizabeth Knox's Blog, page 3

April 1, 2013

My Workspace

My Workspace (without the customary cats)

I guess this piece could be titled ‘How I came to change the way in which I do everything’. It could go two ways—and I’ve decided it’s better to resist neither, to do both, even if one is personal and might seem beside the point of workspaces, and the other will make me sound like a real geek. Well, for three years my life (and writing) pretty much circled one point, my mother. And I am a geek. I’ve always been quick to see how some new technology might be used to facilitate my writing work, or storytelling play. I adopted voice recognition software back in 1997, when the speech engines only operated with ‘discrete speech’, where you have to Say. Each. Word. Separately. (And that would have been nearest I ever got to discretion!) I had a Skype ID very early—2004—when my sister Sara and I reassumed playing our imaginary games, initially tied to our PCs by wired modem and headset.

My workspace is an upstairs bedroom, the quietest room in the house (when the boy below isn’t playing Defence of the Ancients, and yelling at Ukrainians.) However, from 2009 through to the start of 2012, my room was often occupied by Sara, who’d come from Sydney every few weeks. First she came for meetings with doctors when our mother was diagnosed with Motor Neurone Disease, then to help Mum move her from her little house in Picton to a villa at Sprott House in Karori, then many times during the year Mum was in the villa, and throughout Mum’s final year in a room in Sprott’s Duncan Wing. Sara took over some drawers in my office so that she didn’t have to lug all her stuff back and forth on those seat-only flights. Her things were in my office, along with Mums’ precious cast-off crockery and glassware, books, paintings, photos, file boxes full of my Dad’s old Listener articles, and drafts of his autobiography. There were so many boxes that there was scarcely room for my legs under my desk.

When mum’s voice was going, she could still make herself understood on the phone to her nearest and dearest. She would carry a pad and pen, but her writing was only supplementary and, when she wanted to tell a story she’d still get it out slowly in her robotic croaking voice. She’d take phone calls from speech therapists and dieticians and real estate agents, and make affirmative noises back at them as they talked. But she couldn’t talk to them. She’d take their numbers, ring me, and get me to call them. So, when she moved to Wellington, we got her an iPhone. It was way too late for her to get the knack of texting on a regular cell phone; she needed that QWERTY keyboard. And when she got an an iPhone, so did we. It really was the only way to get things said if we weren’t in the room with her. Sara and she got into the habit of writing one another long stories by text. Sara’s about—say—the large snake idling in her driveway (with pictures), mum’s about being highjacked in her wheelchair by one of Duncan Wing’s more doolally residents. Because I went to see her most days, our communications tended to be her shopping lists, or stuff like, Me: Up in ten. Mum: Thanks pet. Or the perennial weather. Mum: It’s blowing like stink and really giving me the pip.

Mum’s handwriting degenerated as she got weaker, and we bought her an iPad. Towards the end she’d have to support her hand on a pillow and rest between each letter of a word—and the predictive spelling would rush ahead of her to provide words she’d needed and used two months before, but didn’t want now.

So—we all had iPads, and I started reading on mine (Kindle), and editing (in Pages) and watching (via Air Video Server). So when my five year old Dell laptop finally refused resuscitation I decided I didn’t need to replace it.

During that time, when my legs wouldn’t fit under my desk, I’d work drifting about the house, following the sun, and followed by my cats. Or, if the weather was really cold, I’d climb into bed with my exercise books, and Stadler learner pencils, and the three furry furnaces. I wrote Wake and Mortal Fire. I kept drafts under my bed. I didn’t have a workspace, and life wasn’t in any way regular and orderly, despite the stern stricture of helping look after someone who, in the end, could scarcely move or make a noise.

Mum died this time last year and, after the funeral, once Sara and I had done a lot of feverish sorting, my office floor reappeared. Sara went back to Australia and got to stay put for eight months. My Dell laptop turned up it’s toes, and I had to face getting a new computer. My needs had changed, so I got a desktop, to which I attached a 42 inch Sony TV. Now I sit on my office couch, with my Logitech lap desk, and my wireless mouse and keyboard, and I do a little dictation maybe. But I still can’t stay in one place. I drift about the house, and I’m not carrying pencil and paper anymore, I’m carrying my iPad. And I’m no longer typing, since technology has finally caught up with what I need. This piece was composed in a handwriting recognition app, Myscript Notes Mobile. Then it was emailed to my desktop, which runs the bigger version of MyScript software that, as if by magic, turns my wonky writing into a typed document. The habitual, old-fashioned hand-writer has just used her squishy-tipped ‘capacitive’ pen as a pole to pole-vault over most of the intermediary stages between thought and manuscript.

In my workspace I have a red Bob MacDonald couch. I have Mum’s small coffee table with the hinged top where I keep my lap-desk. I have my computer and TV/monitor. The room has matai floors, a 60s acoustic tile ceiling, and sash windows facing the suburb of Northland and Te Ahumairangi Hill. The bookshelves house perhaps a quarter of our books. I have the essay collections; the art books; the 19th century fiction; all my favourite, touchstone books; and the poetry because, whenever I get stuck I tend reach for Eugenio Montale, or Anna Akhmatova, or Frederick Seidel, like someone sick taking a huff of pure oxygen.

This piece was first published in the summer issue of the New Zealand Book Council’s Booknotes[image error]

January 12, 2013

Next Big Thing

Margo Lanagan tagged me for this chain interview—her responses to the questions are here Margo’s Next Big Thing is her magnificent novel, Sea Hearts.

I’m tagging Dylan Horrocks. His answers should be up a week after mine. Dylan is in the home straight of his graphic novel Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen. Yay!

Here are the questions, and my answers.

What is the working title of your book?

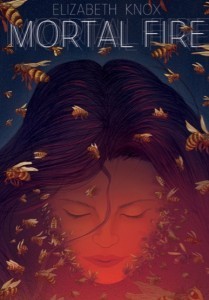

My book is called Mortal Fire—which is a phrase from a poem by William Blake. It is due for publication in June of this year.

Where did the idea come from for the book?

Like many of my book ideas it came from the imaginary game I’ve shared for years, on and off, with my sister and friends. The game provided the germ of a story about a hidden house ‘haunted’ by a powerful, mysterious, and mad young man who is being kept under a kind of house-arrest by his family. I was interested in the effect of solitary confinement on the prisoner, and what depriving a family member of his liberty would do to his gaolers. I was interested in ideas about guilt and revenge.

Of course the basic idea evolved quite a lot I started writing. Mortal Fire tackles the story through its heroine, Canny, who discovers the sad and dangerous, Ghislain. Canny is a person who hates it when anyone keeps stuff from her, and who will go to outrageous lengths to satisfy her own curiosity. She’s is a wilful, wayward, and strong. I’m a fan of powerful, active heroines, but didn’t want to do the weapons-toting kickass type. Canny is full of tricks and and rat-cunning. Much of the novel’s drama, and comedy, rises out of her manipulations—both when they work, and when they eventually, spectacularly, backfire.

What genre does your book fall under?

Mortal fire is a literary fantasy for older teen and adult readers, though it could be enjoyed by a smart 12-year-old

What actors would you choose to play your characters in a movie rendition?

This was a fun one to answer, but became quite hard when it came to Canny. Much as I love Chloe Moretz, Canny is a Pacific Islander. (A Shackle Islander, since the book is set in my made-up Republic of Southland—like the Dreamhunter Duet). So, there’s Keisha Castle Hughes, and possibly Ngahuia Piripi, or the gobsmackingly gorgeous Q’ Orianka Kitcher. I’d pick Ben Barnes as Ghislain – I mean, why wouldn’t you? Alan Rickman would make a brooding and scalding Lealand Zarene. I can see Gary Oldman as Ghislain’s sweet-natured beekeeper brother Cyrus, and Robin Wright as the tyrannical Iris. And someone like Eddie Redmayne would definitely be good as Canny’s long-suffering stepbrother Sholto.

What is the one sentence synopsis of your book?

Girl steals magic, wins boy, then has to outwit forces bent on their annihilation, all while trying to avoid getting told off by responsible older stepbrother.

Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency?

It’s is being published by Frances Foster Books at Farrar, Straus and Giroux in the US, and by Gecko in New Zealand. So far…

How long did it take you to write the first draft of your manuscript?

A couple of years. I was writing Mortal Fire in tandem with an adult literary science fiction novel, Wake.

What books would you compare this story to in your genre?

Megan Whalen Turner’s Queen’s Thief books, because of the machinations, vigour and sensitivity of the main character (plus the tricky romance). And my view of the magic as a kind of science owes a lot to Margaret Mahy (well—all my books do!)

Who, or what, inspired you to write this book?

The setting was inspired by a South Island trip I took with friends when I was 22, in a rusty 1957 Plymouth station wagon. We drove through a valley in central Otago, full of box beehives and beautiful cherry and apricot orchards, all of which now lie under Lake Dunstan, behind the Clutha Dam.

I wanted my heroine to be a Pacific Islander because of my Tongan/Kiwi niece and nephews. And because in various ways Canny’s heritage confounds the novel’s busybodies and generally generates drama.

My heroine is a maths genius, because I was trying to imagine what life might be like for another niece of mine, the very able Bethan, who is doing her Phd in Astro/particle physics at the SISSA research institute in Trieste.

The coal mining disaster backstory is there because of an email correspondence I had many years ago (for a book I didn’t write) with George Muise, a mine rescue captain from Nova Scotia who was the first man to enter the Westray Mine after a terrible methane explosion in 1992.

What else about your book might pique the reader’s interest?

Mortal Fire is one of my Southland books. I’m now planning five books set in my made-up South Pacific Republic: The Dreamhunter Duet (set 1906 and 1907); then three standalone novels, Mortal Fire (set in 1959), and a book set in the 1870s, and one contemporary. All the Southland books explore various versions of the Lazarus magic belonging to the five families who immigrated to Southland from the island of Elprus—the families Hame, Zarene, Eucharis, Magdolen, and Vale. The final book will be kind of a superhero story, with the different magics as superpowers—and the world to save (the books so far may be about saving something, but nothing as all encompassing as a world.)

September 23, 2012

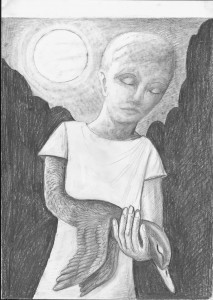

Margaret Mahy’s The Other Side of Silence

Margaret Mahy’s The Other Side of Silence is my favourite among her novels. It is a book that conducts an argument about nature and nurture, the effect of fame on families; that explores the power of speech and silence, of belief and skepticism; and that argues, explores, and demonstrates the shape-shifting nature of story. Actually, words like “argument” and “exploration” seem weak and vague in talking about this book, because all its arguments turn around on themselves, so that the book’s ideas are like a moebius strip; surface and underneath are interchangeable, and nothing comes out on top.

Hero, the protagonist, is a twelve-year-old elective mute, a girl who has stopped talking partly as a protest against the noisiness of her family, and particularly the lacerating rows between her mother, a educational psychologist, and her older sister Ginevra, who has run off four years before the story starts, and has only sent postcards to say she’s okay, but without any forwarding addresses–thus making it very clear that she doesn’t want to hear anymore what her mother has to say to or about her.

Hero and Ginevra’s mother Annie is the author of a famous book, Average/Wonderful, a book about what she learned raising her first two children–Ginevra and Athol. Annie hasn’t had quite so much time or energy for her younger children, Hero and Sap–and she was so busy proselytising on behalf of children everywhere that she was blind-sided by Ginevra’s sense of personal failure at her discovery that everything wasn’t always going to come easily to her, that she has to work at University maths, when maths had formerly been like magic, and her special thing. Ginevra’s version of the family story is as a kind of personal tragedy. Meanwhile, her brother Athol is sitting at the breakfast table, earphones in, apparently listening to music and making notes on a physics tome he carries around with him, but in fact writing down things his family say that particularly appeal to him. Athol doesn’t just see the humour in what happens around him, he also sees it as fodder for the saleable tales he’s farming, out in the back paddock of the family story, for Athol is writing scripts he hopes to sell to a soap opera.

So, this is the shape-shifting nature of story. The family story is a tragedy about a tyrannous mother and put-upon daughter. It’s an inspirational story about how children can be raised to shine. It’s a melodrama, a soap opera.

All these views are arguably true, based on the same evidence.

Then there is Hero’s speechlessness, which seems to be a response to her gut feeling about the potentially monstrous power of story. She doesn’t speak up for herself; she bows out of the struggle to be heard, and keeps a spectacular silence–a puzzle more arresting than speech. She doesn’t even need to be responsible for the story that starts to form around her silence, the story about her silence. She gets sent to a special school, where she can witness with sympathy, but without embarrassment, her highly motivated teachers gradually coming to feel that her continued speechlessness is their personal defeat. She can bear it that her mother takes her silence as punishment, and is puzzled by what she’s been punished for.

There are things that Hero is able to observe and understand because she doesn’t take part, but watches and listens. For instance, that there’s not only a real life but a true life. “Real was what everyone knows about. True is what you somehow know inside yourself.”

True life is the life of story. What is the roar that lies at the other side of silence? Perhaps to Hero it is the endless petitions from the adult world–the TV journalists and conference organisers who want something from her mother, something, then something more. Hero can see that her mother has drummed up attention, and that it has an insatiable appetite. And you can’t control other people’s attention once you’ve invited it, as Hero discovers when she finds a portrait hanging in the ruinous parlour of mad Miss Credence’s house, a portrait Miss Credence says is of Rhinda, her daughter, who has gone off into the world. But Hero knows that the portrait is based on a famous newspaper photo of her sister. Annie’s fame has led to the theft of the child Ginevra’s face.

The story you’re telling yourself about yourself can intersect with someone else’s story–you can turn out not to be the hero, the principal, but suddenly find yourself playing an instrumental role in someone else’s story, being seen according to its lights. This is what happens to Hero.

The old Credence house is at the heart of the posh suburb of Benallan. It is surrounded by a wall, and a garden full of old trees, so overgrown that a child can make its way by stepping from branch to branch. This garden is where Hero goes to exist at her true size–to be a self not constrained by family life.

Margaret really captures that formative time when a child is bold enough to go off and make some place their own–find a small bit of the world in order to become themself in it. A place in nature, or anyway the world without other people and it.

Hero crosses the wall into her kingdom of the trees, which she shares only with the birds, and the ginger cat she meets at the top of the wall: “one of those gentle cats that imagine people will always be kind to it.”

One day the wild girl of the trees takes a tumble out of them, and falls at Miss Credence’s feet. Miss Credence’s behaviour when a girl drops out of the trees in front of her is odd. She doesn’t touch Hero, but immediately begins to incorporate her into a story. “All birds fall before they can fly properly,” she says. It sounds like encouragement, even like Annie’s sort of encouragement, but Hero isn’t being asked, “Are you alright?” “Can you move?” Not that she’d answer, anyway. But Miss Creedence doesn’t want an answer. What answers to Miss Credence’s needs is someone who will listen and not speak.

“’Can’t you talk?’ Miss Credence asked me. I shook my head which seemed the simplest thing to do. I was puzzled by her sudden, odd, eager expression, the expression of someone coming upon something that nobody else wants, and seeing a special way of using it.”

Miss Credence seems to recognise Hero as a fellow soul, someone who is above it all, and apart. She knows that Hero will be aware she’s been trespassing, and that Hero might feel that she owes a debt. These are two people who know their fairytales, who know that if you pluck a rose you must to send your daughter to the beast’s castle. Hero is asked to come back and garden; she’s given a job, with pay. Gardening is the real job–the true one is to listen. As Hero weeds, Miss Credence tells her a modified version of a Grimms’ fairy tale. In the original there is a witch who catches girls, turns them into birds, and shuts them in a tower at the top of her castle. Hero thinks she is being told a story about herself: Jorinda, the bird girl. Miss Credence is in fact telling a tale about herself. She is the bird girl. And the evil wizard, Nocturno, with whom she has replaced the witch, is a version of her father. She is walking around wearing her father’s cloak and hat, mimicking his manner, and it can seem like a performance for Hero–eccentric, harmless, a private remedy to Miss Credence’s polite public existence behind the counter of the Benallan post office.

Listening is complicity, but Hero doesn’t really understand this, or how little power she has over her own path through the forest of Miss Credence’s tale till she is asked for a little favour: will she take a photograph of Miss Credence?

“‘Stand over there,’ she said, ‘Then I won’t be looking straight into the sun.’

I walked over to the door which was where she had pointed I should stand, and when I turned, the whole world changed in half a second.

Miss Credence was suddenly holding a gun under her left arm, and I caught her in the act of lifting a victim from the long grass of the ruined lawn which had hidden it till then. It was my old friend the ginger cat. She held him by the tail and his head bobbed a bit. He had not been dead long. He was still limp. His mouth was open. His tongue stuck out. It was a horror moment, real and true, and I actually felt the world darken around me.”

Miss Credence explains very plausibly that cats kill birds, and once this country was all birds, etc. But what we are meant to hear is this: that Miss Credence knows that to cultivate one thing to perfection necessitates killing something else. The reader’s horror isn’t just because this woman shoots cats. It’s that she gets a twelve-year-old to photograph her holding it up as a trophy. Hero takes the photo, and partakes of the killing.

And, as she does “a gust of wind suddenly struck us and brought to me the scream of the ginger cat’s ghost.” Of course the scream Hero hears is the child trapped in the tower at the top of the house. A foreshadowing–we’re being asked to consider that someone capable of the cruelty of shooting a bird-killing cat might be capable of greater cruelty.

Miss Credence covertly overpays Hero for her favour, and when Hero discovers it she feels obliged to go back to return the money. But Miss Credence won’t take it. She’ll only let Hero work it off. So Hero is gradually inducted further into the madness of Miss Credence’s life, by what she’s asked to do, by what she sees, and by the stories Miss Credence continues to tell her.

Professor Credence was, Miss Credence says, a man of ideas and a famous educator. And the reader cannot but think of Hero’s mother, Annie. The Annie of this book–rather than its back-story–has gradually been forced to accept that her view of herself as a benevolent mother wasn’t the whole truth. Despite her love and good intentions things haven’t turned out perfectly for her family.

Now the beauty of this–of Margaret’s approach to all this–is that it isn’t decided. Annie isn’t at fault, nor is she blameless. The fact that she sees herself as a committed crusader (and she pretty much is) is balanced in the story by the reader’s understanding that Professor Credence also saw himself this way. Annie insists that every child has got the potential to be brilliant, or wonderful (a much better word, a Margaret word, that describes what Margaret desired for herself and everyone else–that is: to enjoy a sense of wonder, and to be made wonderful by it). This is sunny and positive, but it also has the possibility of defeat built into it–after all, what are we to think when someone is given every opportunity, yet can’t be coaxed into opening up–and we get a glimpse of this in the plight of Hero’s energetic, caring teachers at Kotuku House, who are defeated by her unwillingness to to give up even one negative decibel of her self-imposed silence. Also, in relation to her own wonderful children, Annie’s ideas have taken on the appearance of secret self-congratulation. Her kids are brilliant because she did the right things with them. This is closer than is comfortable to Professor Credence’s insistence on his daughter’s specialness because she’s his daughter. She’s not like her mother: “mother didn’t operate on our level,” as Miss Credence blithely tells Hero. Professor Credence’s brains are a bequest, a birthright. He and his daughter are an elect: “he was a member of MENSA as well, and they only take the top two and a half percent, so of course it was a thrill for him when I became a member too.” The Professor’s argument for the exceptional talents of his child is essentialist. Annie’s are about what astonishing material all children are, if nurtured in the right way. Here Margaret isn’t so much debating the nature/nurture argument as letting its tension, and our culture’s unease about its undecidability, hum away under her story. Margaret, or possibly the story itself, isn’t interested so much in whether Professor Credence is wrong, and Annie right. What the author and story seem to be interested in is how faithfully sticking to certain beliefs–whether the Professor’s essentialism, or Annie’s benevolent certainty that there is a best to be be made of everyone–shapes those nearest to the believer, those who are meant to demonstrate the truth of the believer’s beliefs with their real lives, or at least keep faith with those beliefs.

The Professor’s exceptionalist essentialism seems less a fully formed world view than a shrinking neurosis. The man teaches, is a celebrated educator, but still feels under-appreciated, slighted, sidelined by people around him, because, he says, they’re jealous of him because he’s the only person in New Zealand who gets his articles published in the august overseas magazine Philosophy and Literature. He is an embattled man. Of course there are people he courted, people he shone his light on. When his daughter was younger–she tells Hero–they had garden parties. And because her father’s sense of what he deserved was so great, his daughter always believed that the people who visited came to worship at his feet. However, it becomes clear to the reader, if not to Miss Credence herself, that the visitors came out of fondness for her home-making, flower-arranging, hostess mother. When her mother died there were no more visitors, apart from Clem–and it’s interesting that this acolyte’s name should suggest silence, being Clammed up. Clem was willing to sit and listen, and admire, and that’s what made him valuable company for Professor Credence.

Margaret lets us in on the operations of the terrible Professor’s mind by opening little windows in Miss Credence’s talk. She speaks about him with admiration. She exonerates him. She seems to forgive him. But cold winds of rage and betrayal are blowing through every window–with bits of straw–because he’s a man of straw. Margaret’s characterisation of Miss Credence’s own helpless characterisation of her father also provides yet another contradictory double-back in Margaret’s pursuit of the truth and utility of the nature/nurture argument. It’s the book doing its moebius strip thing. Professor Credence espouses a very rigid form of the nature argument–some people are born better than others–but as a dark echo of that, the way in which he is portrayed makes it look as though he is in fact one of those people who was born with a terrible lack: a developmental disability. I keep wanting to say, “Oh, he’s on the autism spectrum–or perhaps he’s a narcissist.” I want to make sense of his character as a pathology. I want to point to his lack of empathy, and his obsessive thought patterns–I even want to take as evidence Miss Credence’s quizzical squint, her wandering eyes, her monologues. I want to point out Miss Credence’s helplessness as a housekeeper. I mean–there’s never learning how to keep a place tidy, and there’s haplessly living in clutter and filth. All these things look like signs and symptoms and it does seem that, while Margaret presents the nature argument in a poor light, with a horrible champion, she’s also showing us a proof of the nature argument. There was something wrong with Professor Credence, wasn’t there? He was blind, not wilfully, but pathologically. This doubling back of proof and counter-argument, on argument and proof, is just one instance of the way in which this novel’s main–and great–business seems to be to embrace contradictions.

Hero’s sister Ginevra, finding herself pregnant, has the sense to come back to her family. And she has the luck to have Sammy with her, an older son of her baby’s father, also abandoned by him, whom she brings home to her family because she can finally recognise that it’s a good family, even if all families are kind of tyrannous.

In contrast, Miss Credence, when she has her child, is totally unsupported, abandoned by the child’s father, the scarcely audible and visible Clem, and by her own father, who has died and left her completely ill-equipped to cope, particularly with with her feeling that she’s let him down. He could never forgive the colleagues who failed to appreciate him. She can’t imagine him being forgiving, so can’t imagine him forgiving her. She says that when she first looked at Rhinda she saw something wrong with her. Rhinda was a mistake, so it followed there must be something wrong with her. It’s quite clear to the reader that there probably was never much amiss with Rhinda. When Hero is shut in the tower with the girl and watches her clawing at her own face and screaming silently, she thinks: “I knew she could scream, but she never did when there was anyone in the room with her. So she could be taught. She could learn.”

Now, this terrible story–the story of a closet child–also operates as a commentary on Hero’s voluntary speechlessness. Hero sees that Rhinda hasn’t chosen silence, she’s been silenced, and that’s a very different thing. It’s a great moment of revelation for Hero. She may have understood the impact of her silence on the people around her, but she hasn’t been able to see until that moment what an extremity it is. “What kind of person stops talking? Real people all talk. Perhaps the silence that had made a special person of me in my talking, arguing family really showed that I was a little mad, as well.”

People in this book are silenced. Hero by her desire to establish a separate, marvellous identity. Rhinda by a mother who sees mistakes everywhere, and stuff that needs to be kept under wraps. Miss Credence is silenced by a father who has taught her that she’s so special it shouldn’t be possible for her to put a foot wrong, so that when she does she can’t seek help. Sammy is silent (or unintrusive, rather, since he hovers around the edges, spying and bouncing his basketball). Sammy doesn’t know what to make of the family he finds himself with, and he’s waiting to figure it all out. No one quite manages to silence Annie, which I think is very good, because Ginevra certainly tries to drive her mother into a more manageable position, manageable for Ginevra. But Annie is kind of shameless and irrepressible, in pretty much the same way that Ginevra is.

And then, at the very end of the novel, the novel itself is silenced in a most interesting way. . .

We are told that Hero has written her story down and that that is what we’ve been reading. The narration switches from the first person to the third. Hero–silent Hero–has been talking to us, and now the story itself (or its author) is telling us about Hero. This last section is the story after the facts. After the facts of the story, comes the story of the facts.

Perhaps the most disturbing thing about this brilliant, disturbing book is that, at its end, Hero decides again on silence. She chooses self-abnegation. She’ll talk to her family, but she won’t talk to the world. She follows the advice of a fairytale and “tells her story to the old stove in the corner.” It’s actually the second time in a young adult novel by Margaret that a protagonist burns her book. In The Tricksters Harry burns her novel because when she hears someone else reading it aloud she realises that it’s a load of silly fantastical nonsense, an insult to the beauty and complexity of her real family life. Harry burns her novel because it’s bad, and because her heated fantasy has conjured fantasy figures into flesh people, has raised fleshly ghosts. The book-burning seems like a necessary, evolutionary step towards becoming a writer–a form of extreme editorial intervention. (Though I have to say, stories about writers burning their writings always give me qualms. I think of Emily Brontë burning her writings because she knew she was dying. Then of Emily Brontë dying perhaps because she burned her writing. I know that my father burned all his journals when my mother broke off their engagement, so that when he set out to try to write again he had nothing behind him. I’m sure that a writer’s many early accumulated pages provide that high place to which the devil can take them and offer them the world.

Harry, when she burns her book, seems to be having a moment of great good taste and judgement. But Hero immolates the story she’s just told us. The formerly silent child from a “word” family chooses to speak, but not write. Perhaps she’s going to become a barrister and keep people out of prison. That would be a good use of what she’s learned. But as a reader I was sad that Hero’s world lost the book I’d just read–which was, by the way, probably the best and most sensitive telling of poor Miss Credence’s story.

Annie has read the book and, because she’s Annie, her praise is threatening and off-putting to her daughter: “You’re a writer, you really are.” She says the word “writer as if she were announcing a great victory for Hero.” Hero is deeply suspicious of any claims to a world stage. She thinks, “Perhaps there’s only just enough light and warmth to go around, and people like Annie, whether they mean to or not, are using up someone else’s share.” So into the wood burner her pages must go. And, “By the time she closed the door of the wood-burner, her story was roaring like a lion in the long throat of the stove pipe.”

I have always thought this wasn’t a coincidental simile–especially since it’s developed further. “She imagined her story, leaping up into the sky, shaking its mane of smoke, and then slowly dissolving over the city, becoming not just one but many stories.” I think we are being shown not just Hero’s, but Margaret’s, gesture of exorcism and renunciation. The author has written a book that explores the good and evil of privacy, the virtues and faults of silence, the good and bad of fame, and then seems to bring it all back to her own case where, after all, these interests come from–and “interests” is a weak word–it’s more than interest, it’s conscientious worrying, it’s real trouble. Margaret imagines the sound of the fire as a lion’s roar, and I can’t help but wonder whether she is having a moment of thinking if only I had not let my lion loose on the world. After all, if there is a moment in Margaret’s story of herself from which Margaret-the-writer proceeds, it’s from writing A Lion in the Meadow, a book with, as it insists, a lion that is there–a lion that is still there–like Margaret the writer is indelibly here, the subject of our talk. When Hero burns her book, Margaret is letting herself imagine a whole different life. A life without an afterlife. She imagines it–but of course the novel’s final, most sly, terrible, and triumphant contradiction is that, though Hero burned her story, and chose silence on these matters, we’ve just read the story, and need only to turn back the pages to read it again. So, Margaret imagines someone choosing not to be a writer, choosing not to trouble the world that way. She burns the book, but–as she would put it–it turned out that, all along, the book was a phoenix.

September 6, 2012

Hermitage

Ray Knox

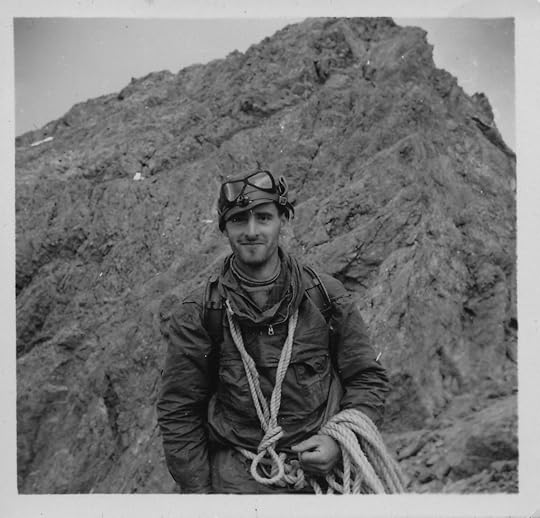

Between 1954 and 56 my father was a guide at the Hermitage, in the Southern Alps. I was brought up with Sefton and Sebastopol, shale and serracs. And with dad’s ice axe, which hung in the garden shed in Pomare, then the basement workshop in Wadestown, and finally in the garage in Paremata.

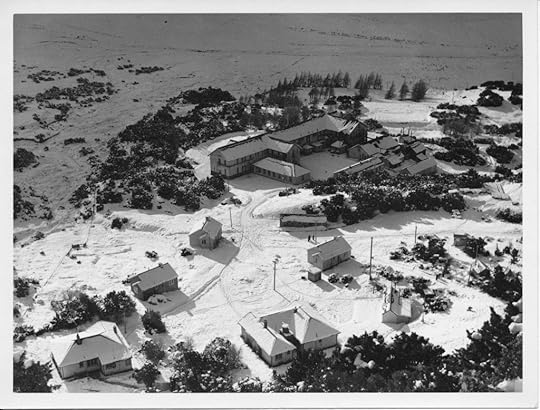

The Hermitage, which the Department of Tourism sold as: “Thousands of feet above worry level.” A little clutch of buildings set down in what one British journalist called a quarry. An Alpine Valley, with tussock, and heaps–not of slag, but shale, the gizzard stones of glaciers.

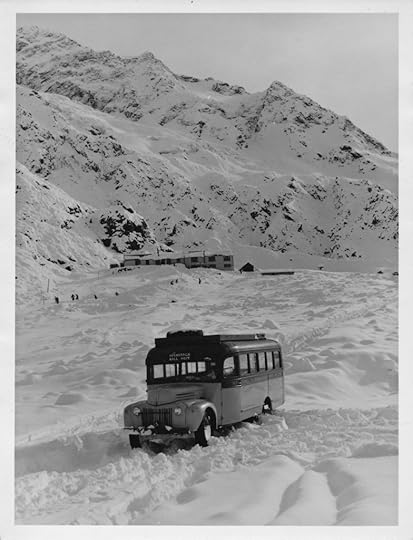

The Hermitage, which the Department of Tourism sold as: “Thousands of feet above worry level.” A little clutch of buildings set down in what one British journalist called a quarry. An Alpine Valley, with tussock, and heaps–not of slag, but shale, the gizzard stones of glaciers. This is the Ball Hutt bus. Winter was ski season and the guides would open the ski room, check all the bindings, shelac the skis, three coats each, and service the ski tow engine.

This is the Ball Hutt bus. Winter was ski season and the guides would open the ski room, check all the bindings, shelac the skis, three coats each, and service the ski tow engine.

When the snow was deep they’d move supplies up to the hut by tractor, on a road that in one section ran along the top of the moraine, with a big drop either side. They’d pick up supplies dumped by the bus at Husky Camp. In the worst weather they’d only go when they ran out of beer.

When the snow was deep they’d move supplies up to the hut by tractor, on a road that in one section ran along the top of the moraine, with a big drop either side. They’d pick up supplies dumped by the bus at Husky Camp. In the worst weather they’d only go when they ran out of beer.

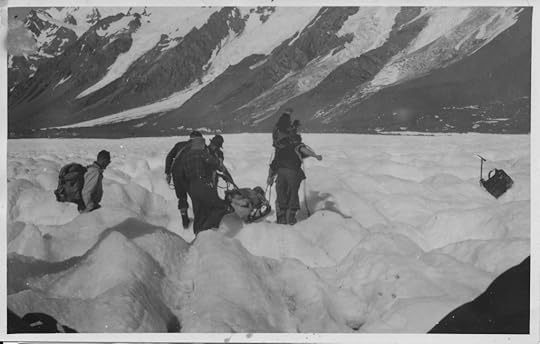

The guides thought the tractor trip so hair-raising they decided to do fewer, and carry more. They built a sledge, and only then ran their it past Mick Bowie, the head guide. Mick was famously inscrutable. He had a grunt which could mean he was a)disbelieving, b)deeply offended, c)at a loss for words d) grudgingly giving in. Mick grunted, but the sledge was a bust.

The guides thought the tractor trip so hair-raising they decided to do fewer, and carry more. They built a sledge, and only then ran their it past Mick Bowie, the head guide. Mick was famously inscrutable. He had a grunt which could mean he was a)disbelieving, b)deeply offended, c)at a loss for words d) grudgingly giving in. Mick grunted, but the sledge was a bust.

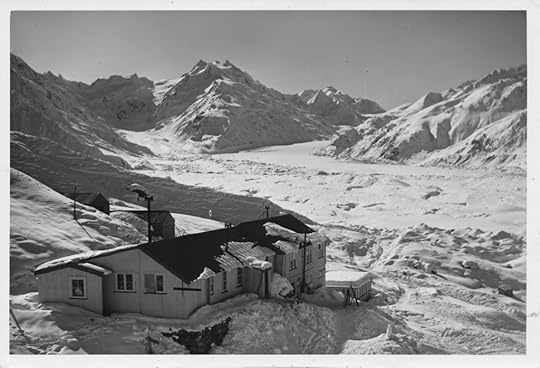

This is Ball Hut. The caption written in Dad’s hand on the back of the photo is, “My home most of the time.”

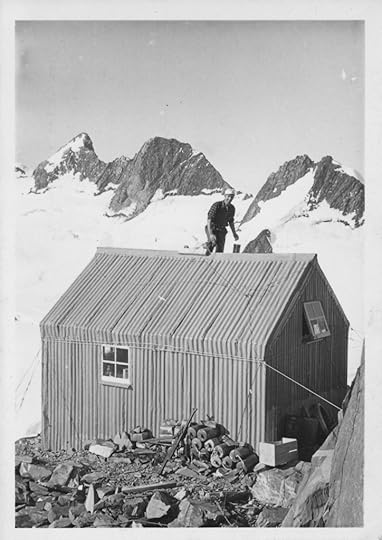

The rest of the winter the guides strapped their skis on their backs and trekked off to mend huts. Here’s Dad fixing a hut roof.

The rest of the winter the guides strapped their skis on their backs and trekked off to mend huts. Here’s Dad fixing a hut roof.

Dad loved the mountains so much that he bought pastels and started trying to capture them. He tossed his failed pictures of the perfectly round rainbow-hued cloud he’d seen. “Unbelievable” he said. “All it lacked was a little green man climbing out of it.” This he kept.

Dad loved the mountains so much that he bought pastels and started trying to capture them. He tossed his failed pictures of the perfectly round rainbow-hued cloud he’d seen. “Unbelievable” he said. “All it lacked was a little green man climbing out of it.” This he kept.

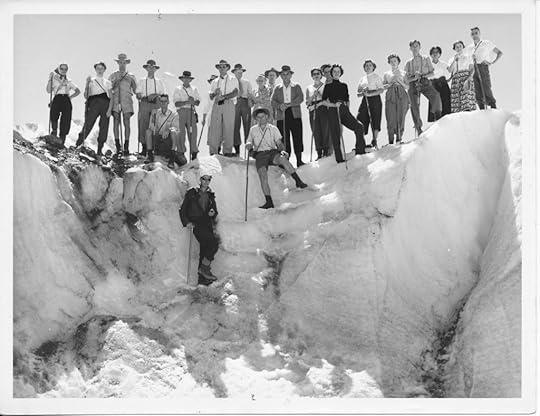

Summer brought tourists. The guys in swannies are the guides. The tallest is Phil Boswell about whom I know only this; that he could suck up a whole plate of jelly in one go with a sound like a cow pulling its leg out of a bog.

Summer brought tourists. The guys in swannies are the guides. The tallest is Phil Boswell about whom I know only this; that he could suck up a whole plate of jelly in one go with a sound like a cow pulling its leg out of a bog.

Dad blew a hernia racing up a hill with a crate of beer. He spent three weeks in hospital in Timaru. The surgeon said to him, “It this operation succeeds you can keep on guiding. If not you can do something else.”

Dad blew a hernia racing up a hill with a crate of beer. He spent three weeks in hospital in Timaru. The surgeon said to him, “It this operation succeeds you can keep on guiding. If not you can do something else.”

“What else?” Dad thought. If he left the Alps he believed some part of him would die, change, vanish.

When he came back he was on light duties. He’d take tourists for an amble down the moraine onto the white ice of the Tasman, and they’d sigh with wonder.

When he came back he was on light duties. He’d take tourists for an amble down the moraine onto the white ice of the Tasman, and they’d sigh with wonder.

They’d go into an ice cave, or he’d let them toss rocks down a moulin to hear the distant splash in the blue depths of the glacier. When I was eleven he took me onto the Tasman, and we did those things.

They’d go into an ice cave, or he’d let them toss rocks down a moulin to hear the distant splash in the blue depths of the glacier. When I was eleven he took me onto the Tasman, and we did those things.

In summer serious climbers set off up mountains. Here’s Dad, about to break through a cornice onto a ridge.

In summer serious climbers set off up mountains. Here’s Dad, about to break through a cornice onto a ridge.

Once he fell into a crevasse, losing the white ski cap Mum had knitted for him, and his self-possession. He was saved by his ice axe and another guide’s belay. But it took him four hours to climb out.

Alpine rescue. Tasman Saddle, 1954. Dad is at the back, with a hat. The woman in the stretcher had slipped on the ice and broken her leg.

Alpine rescue. Tasman Saddle, 1954. Dad is at the back, with a hat. The woman in the stretcher had slipped on the ice and broken her leg.

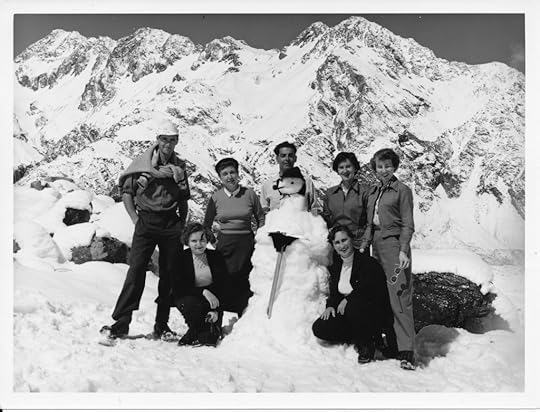

In February 1955 Dad married. Mum and he moved into Sealy cottage. Mum loved the white Rainer cherry trees around the Hermitage, the black Alpine butterflies, the white Alpine grasshoppers. But she didn’t like the winter, when the kea would come and swing upside down from her frozen washing.

In February 1955 Dad married. Mum and he moved into Sealy cottage. Mum loved the white Rainer cherry trees around the Hermitage, the black Alpine butterflies, the white Alpine grasshoppers. But she didn’t like the winter, when the kea would come and swing upside down from her frozen washing.

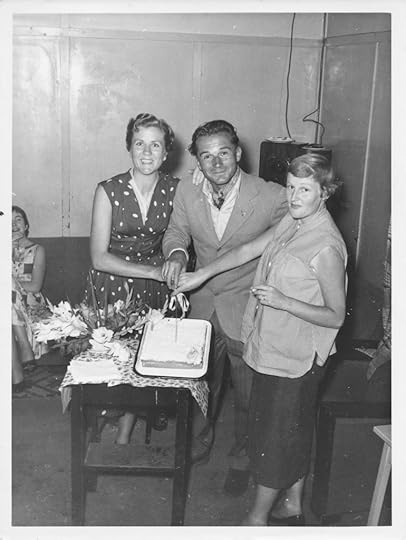

Mum is on the left.

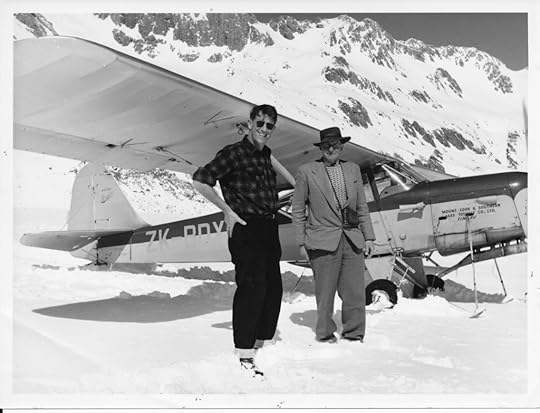

This is dad with Harry Wrigley on the day he first landed his prototype skiplane. It was a great success and there were many drop offs. Wrigley used to read his newspaper until the plane was right between the mountains, then he’d pass it back to another passenger, and open his window to pull the lever that made the wheels retract through slots in the skis.

This is dad with Harry Wrigley on the day he first landed his prototype skiplane. It was a great success and there were many drop offs. Wrigley used to read his newspaper until the plane was right between the mountains, then he’d pass it back to another passenger, and open his window to pull the lever that made the wheels retract through slots in the skis.

Sir Edmund Hillary and Harry Wrigley

Dad took this one of Harry and Sir Ed. Sir Ed and Dad were planning an ascent of Cook, but put it off when they found out their wives were pregnant. So, there was a baby on the way, no medical facilities, no other children, no promise of a school, and a doubtful future in guiding. The tourist department already had guides eradicating stoats, and cutting down the Rainer cherries.

So, there was a baby on the way, no medical facilities, no other children, no promise of a school, and a doubtful future in guiding. The tourist department already had guides eradicating stoats, and cutting down the Rainer cherries.

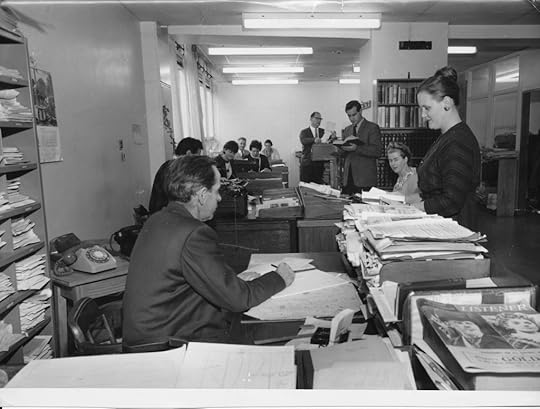

Listener offices

Dad applied for a job on the Listener, then went off of a Trans-Alpine climb. At Fox Glacier he had a call from Mum to tell him he was expected at an interview in Wellington in five days. At the interview Listener editor Monte Holcroft set Dad some test radio reviews. Dad wrote them looking out on Mt Blackburn. There was only one man the Listener wanted–Maurice Shadbolt. But Maurice changed his mind–and Dad got the job. When Dad was depressed, I’d imagine him in a snow cave. He took this photo when he and some friends were snowed in for six days on the Franz Josef Neve. He was probably quite content. He loved to keep moving–but he always carried a book, and he’d write poems on the end papers.

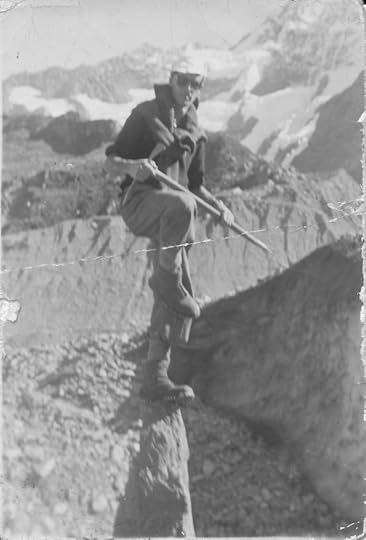

When Dad was depressed, I’d imagine him in a snow cave. He took this photo when he and some friends were snowed in for six days on the Franz Josef Neve. He was probably quite content. He loved to keep moving–but he always carried a book, and he’d write poems on the end papers. Here he is balancing on Turner’s Rock, above a two thousand foot drop. Never afraid of falling. The only time he had a near miss was when his jersey got caught on a nail in some scrap timber he was tossing onto the dump far below Malte Brun.

Here he is balancing on Turner’s Rock, above a two thousand foot drop. Never afraid of falling. The only time he had a near miss was when his jersey got caught on a nail in some scrap timber he was tossing onto the dump far below Malte Brun.See the cigarette in his mouth? That’s what eventually got him.

August 18, 2012

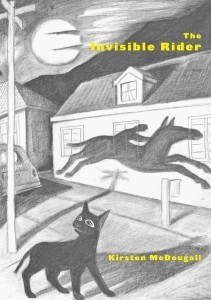

The Invisible Rider by Kirsten McDougall

The cover and illustrations are by Gerard Crewdson

I was pleased and privileged yesterday to launch this book at the Thistle Hall in Wellington. This is my launch speech.

I was fortunate to be present at the birth of Philip Fetch. It was during a workshop on world-building that my sister Sara and I ran on four consecutive Saturdays a few years back. The workshop group figured out between themselves a plot germ, and a collection of character germs. These characters were put in a hat and everybody in the workshop picked one. (Sara’s and my plan was to try to shake the writers free of any cherished avatars or Mary-Sue characters they might have brought with them into the room.) The person Kirsten pulled out of the hat was one half of a couple who ran a garden centre. The writer who got the other half of the garden-centre couple wasn’t particularly happy to lose the beautiful young mistress of a bondage and discipline loving super-rich CEO–the character she’d brought into the room and which she really probably should have carried off again and developed! Anyway–though she wasn’t happy, for Kirsten this early-middle-aged fellow she’d had wished on her was a very happy accident. None of us–Sara, me, the group–had any idea what the character was like. A bloke, thirty-something, that was all we had. But when, the following Saturday, Kirsten produced her piece of writing she came up with an unusual and authentic voice, and a fully formed worldview. It was like magic. And Philip was what Kirsten carried away from that world-building workshop. Some time–and baby Francis– later I got to read the manuscript of The Invisible Rider. And to meet the true and final Philip Fetch.

Philip is a husband, to Marilyn, the father of a young family, George and Charlie, a lawyer with an office in the local mall, who handles conveyancing, property, wills, the occasional divorce–those little bits of road, and bridges, and driveway in an ordinary life. He is a man who believes that cycling to work is a good thing–though he doesn’t do it often enough. He’s a man who isn’t so much keen on exercise, or self-improvement, as someone who likes to commune with the wind, and have a bit of time to himself to think. He’s a particular man, a well-intentioned man, someone who would like to save the planet, be a better husband, be a better father, a better friend. He has, like most of us, a feeling for how things should be. The shape of a good life. But he’s frequently baffled, and better suited to acts of wish than acts of will. Though his wishes are very powerful. “I won’t die. You won’t die. You will never, ever have to make your own dinner” he thinks, in desperate benediction, at one of his children.

The Invisible Rider is a discontinuous narrative–a wonderful and under-explored form, somewhere between a collection of stories, and a novel. (The Invisible Rider‘s illustrious predecessor in New Zealand writing is, of course, Barbara Anderson’s brilliant Girls High.) In these stories–or chapters–nothing plays out the way the reader expects. Kirsten’s imagination is social, socially observant–for instance she notices the way that people disavow things they supposedly approve of in the way they talk about them: a man says, ostensibly praising his wife, “She was all for feminine rights and that sort of thing.” “Feminine”. But Kirsten doesn’t give us social satires. The fictional situations are recognizable and real, and they’re always being altered by the way the main character thinks or feels, or by someone doing something odd, strange, playful, whimsical, silly.

Philip keeps trying to come to grips with people’s real selves, but his gears are constantly slipping. This makes for magnificent bits of comedy, for instance when Phillip’s greengrocer comes in wanting a divorce, and an exchange ensues that is puzzling and exhausting for Philip, and hilarious for the reader. Let me quote a bit that’s a little after the section Kirsten intends to read, but from the same scene.

“This is my lawyer,” said the grocer. “I want a divorce.”

“What?” she said.

“You heard me,” he said.

“What lawyer?” she said.

She looked at Philip when she said it. She glanced at him as if he was just another passenger on a crowded train.

Kirsten has a lot of fun with this stuff. Frustrations and ludicrous mishaps may be trouble for the characters, but the reader is filled with affection for this anxious, gloomy, hopeful, experimenting man.

The Invisible Rider is a book that has a very strong feeling for its setting, particularly Island Bay and Wellington’s south coast, where the sea breathes, and the moon burns like Moloch, like a hungry God, where people look across, up, or down into other’s houses, and grand operas, farces, and pantomimes are played out on the sloped stages of hillsides. Landscape and cityscape are central to this book, which is about, among other things, encroachments. Encroachments and the self. The little wilderness of a section next door is bulldozed and developed. Ground is broken for a local supermarket, a project Philip had thought was “up for appeal”. Things change, and Philip starts mourning his children’s childhoods while they’re still quite small. He can see it all going. He can see it all coming. He doesn’t know quite what to do about it. Philip isn’t a sensible man, except in the old-fashioned sense. He’s alive to the moment and the possibilities of the moment, is a thoughtful person whose thoughts are reactive. Distressing events occur and Philip tries to resist. He puts his foot down on the road and stops the traffic, or tries to, but there is always someone shaking their head, and tapping their watch.

One meaning of the word “rider” is an addition or amendment to a document or testament. So, there’s this invisible rider, on his bike, a man making his own way, under his own power, disregarded and endangered by momentous, hurtling forces. Encroachments, the big cars that bloody own the road, the developer breaking ground immediately outside the kitchen window; something strange and death-dealing at the local pond; Christmas music ramping up in November at the local mall, and leaking in through all the seams of Philip’s flimsy office–there’s all this, road rage, headwinds, head lice, the silence between a man and his wife that pushes them to opposite ends of their marriage; the ghost of the dead mother who doesn’t console, or offer good advice, but just wafts in with her niggling commentary. How can a hero have boundaries if he can’t make himself seen? This funny, thoughtful book gives us all this in prose that is somehow condensed, like poetry, but prose with plenty of air in it. The narrative is a honeycomb holding good, glowing, flowing observation and invention. And a “rider”, an addition or amendment to the testament, does follow each story invisibly. We are shown what the protagonist notices, then, for the most part not articulated, but only implied, is this: If these things are noticed, what do we know? What we feel we now know after finishing each story–that’s Kirsten’s invisible rider.

I’m very proud to be launching this book which brings a wise and highly distinct new voice to New Zealand writing. So without further ceremony I will hand Kirsten and her invisible rider over to all you visible readers who will, I hope, carry the book from this place and bring it to the attention of many more readers not currently visible.

Thank you.

July 24, 2012

Margaret Mahy, Hero

I first met Margaret Mahy when I was working in the shop in the old National Museum, Buckle Street. I met her in The Haunting, then, the very next day, in The Changeover. I was too old to have read Margaret’s picture books as a child, and I sometimes think what it would have been like to have gone on missing her until I had Jack, to whom I read The Lion in the Meadow, and The Boy who was Followed Home, and The Great White Man-eating Shark. As it was, when I was twenty-five I took up reading young adult literature again (after giving it up fourteen as being something I should grow out of). My renascence began when I picked up Diana Wynne Jones’s A Charmed Life in a fifty-cent stack in a second-hand bookstore. I’d plunged back into those books and was reading Diana Wynne Jones and Robert Westall, William Mayne and Antonia Forest and Cynthia Voigt. One Saturday morning in the shop I was unpacking book boxes and found a pile of hardbacks of The Changeover. I loved the cover–that dark, sombre-faced girl holding up an old coin, or token. That cover sang “heroine” and “magic”.

I first met Margaret Mahy when I was working in the shop in the old National Museum, Buckle Street. I met her in The Haunting, then, the very next day, in The Changeover. I was too old to have read Margaret’s picture books as a child, and I sometimes think what it would have been like to have gone on missing her until I had Jack, to whom I read The Lion in the Meadow, and The Boy who was Followed Home, and The Great White Man-eating Shark. As it was, when I was twenty-five I took up reading young adult literature again (after giving it up fourteen as being something I should grow out of). My renascence began when I picked up Diana Wynne Jones’s A Charmed Life in a fifty-cent stack in a second-hand bookstore. I’d plunged back into those books and was reading Diana Wynne Jones and Robert Westall, William Mayne and Antonia Forest and Cynthia Voigt. One Saturday morning in the shop I was unpacking book boxes and found a pile of hardbacks of The Changeover. I loved the cover–that dark, sombre-faced girl holding up an old coin, or token. That cover sang “heroine” and “magic”.

Cheryl said, “You are probably going to want to read the other one first,” and passed me The Haunting. (I still don’t know whether she thought that the two stories were related, or whether she just wanted to make sure I started with the book she had already read and enjoyed.) I took The Haunting home and read it that night, holding it with very clean hands, peering into its right-angled pages, careful not to crease the spine–all of which meant I could return it to the shop looking untouched. I consumed The Haunting, and took The Changeover home the following night.

It is difficult to describe the impact of that reading. I loved The Haunting and The Changeover like I loved Diana Wynne Jones–without yet understanding how lucky I’d been to encounter those two writers so early in my young adult reading. I loved Wynne Jones, but with Margaret I understood I’d met a writer who was for me. She was a New Zealander and, reading those two books, I felt that she was building a room in New Zealand literature where I wanted to go, be, hang out, get comfortable. I’d read Maurice Gee and Katherine Mansfield, Patricia Grace and Janet Frame–my big four–and I felt their presence as explorers. They’d gone off in various directions and hammered in their boundary pegs in places that felt less hospitable to me. Margaret’s boundary peg was a spar, standing upright in the sand of a sheltered cove, flying the salty remnants of a black flag, and with sea-pink growing around its base.

After that first encounter I read everything I could find, the picture books in stock in our well-stocked shop, and everything in the Wellington Public Library. I bought the YA books as they came out–in hardback–and this was when I was a poor student, so the book-buying was quite a commitment. I didn’t feel I had to own Wynne Jones; but I had to own Mahy. I can remember my excitement when I found one of her speeches, about reading and writing, the first piece of writing by her I’d read that was intended for an adult audience–an audience of librarians and scholars. I remember hitting myself on the head a few times with the literary magazine it appeared in, and then hiding my eyes in the open book. It was Margaret’s thinking that I wanted to be able to beat into myself, or isolate myself with. Her thinking–always unusual, and always right. How did she do it? How could she always seem to take a different tack and still always head in the right direction? (By this time I was beginning to see that, at least for me, Margaret’s boundary marker was in two pieces, and in numerous places. Part of it was buried in the sand in that friendly cove, the other was still attached to a roving vessel, somewhere over the horizon, still flying its black flag, and picking up any treasure it could find.)

So–that was me–working part-time in the Museum shop, reading Mahy, and writing my own novel, which was a ghost story, but not a young adult book. Then After Z-Hour was published and, lo and behold, Margaret Mahy reviewed it for the Listener.

At the time of the publication of my first novel I was both a newly published and a novice writer–still a novice because I wasn’t fully literate. I might have been the daughter of an editor, and have attended one or two PEN parties as a young person. I might have seen Witi Ihimaera hiding behind a piano, and a sozzled Denis Glover kissing my sixteen-year-old sister–seen writer antics–but the writing life I imagined was one where I got to talk to other writers about writing. I figured that since Margaret had reviewed my book she’d know I was a real writer and it would therefore not be too rude or forward of me to invite her to have a cup of tea with me when I was in Christchurch with my husband at a Booksellers Conference. It was 1988. Margaret came to our hotel at two in the afternoon when Fergus was at a seminar, and we had tea and cakes in my room. She was friendly and nervous. I was a starstruck mess of shyness, enthusiasm, and entitlement. She had a cold. At one point she fished in her sleeve for a tissue and pulled out a teabag. She looked at it. I looked at it. We both laughed and, after that, settled into a conversation about writing–which would have been far more satisfying for her I’m sure if I had written more and really knew something!

Margaret was always very kind, and she had time for people, for readers and teachers, librarians and people running international conferences on this and that. She had time for fellow writers (even youthfully callow fellow writers). She liked to meet people and talk to them, but she did say to me, years later, that when she did “too much”–being available, pleasing people, being loved, feted, owned–she’d sometimes feel raw and skinned and would take a long time to settle back into herself, her true self, her born writer’s solitary, savage self.

So, there I was, probably providing her with some pleasure and entertainment, but blithely and thoughtlessly taking up her time. It never occurred to me.

Soon after, Cheryl decided that it would be a very fine thing if the Museum shop could bring Margaret up for a weekend reading in the Theaterette. “You’ve met her, you can ask her.” I called Margaret up and asked, and she said yes (as she invariably did). “And you can stay with us,” I added.

“I be delighted to,” she said.

That is how Fergus and I came to be entertaining Margaret–having her all to ourselves–at dinner, at our dilapidated flat. The bed she was offered was sitting on bricks (low beds were in vogue and all my friends were removing their bed legs. Besides–well–bed legs creaked so, and we were all in flats with thin walls…). 246 The Terrace, the top back flat, was leaky and draughty, and had torn curtains and a loose weatherboard that went “Thwang, Thwang” all night in a northerly.

I feel astonished and rueful looking back on this. But I think how good Margaret was writing about these things–the things that young people just don’t see, with their sharp senses and vigour and appetite. She could write for the young–and gently and coaxingly against them too. Her books love their young heroes’ capacity, but almost all of those young heroes are, at some point in the story, innocently hardhearted towards their elders.

That night was one of the first of a very few long conversations I had with Margaret. Like most of them it was shared. (There were others, very rewarding, shared with Kate De Goldi, and Yvonne Mackay’s cousin Denise, a Christchurch photographer, and with my infant son Jack and her infant granddaughter Alice on our legs in a cafe, kept quiet by being fed bits of rosemary roasted potato, but nevertheless gradually covering us with grease till Margaret was looking at me through glasses stippled with tiny fingerprints.)

What was it like to have a conversation with Margaret?

She was widely and deeply read, and curious. But that only describes her habits of acquiring the world, not how her mind worked. Her mind was astonishing (a word she loved). People have remarked on her feeling for myth. But what she had a feeling for was significance. She saw possibilities for meaning, for story, in the way ideas fitted together, not mechanically, but as if this thought and that would suddenly seem subject to the same gravity, as if the way things fell together revealed the star they belonged to–the shining star, or the obscure one, whose only energy is gravity. This meaning-seeing and making was simultaneously playful and serious. It seems to me that her thinking and her work never sought to find a balance between fun and seriousness, fancy and portent. The opposing qualities just partnered-up, and wobbled, and danced. Margaret could say so much, and do so much, with one stroke of the tongue or pen. For instance, I remember yelling with joy at the line in The Pirates’ Mixed-up Voyage concerning the philosophical position of the parrot given to intoning “Doom and destiny!” With just four or five lines she produced 1) a very funny joke, and 2) a deeply felt personal worldview, and 3) a potted history of Western philosophy in all its sober nuttiness. I mean–this was a book for 8 to 11 year olds and it clearly came out of the same mind that, in The Changeover, spends a certain amount of time–a bit too long for comfort–contemplating the terror of the death of a child. Talking to Margaret I always had the sense that there were things she had made up her mind about for the purposes of transmitting helpful and thoughtful views to her readers, and that, beyond that, the generative and noticing imagination that came up with the thoughts was always turning up as many monsters and paradoxes, and that those monsters and paradoxes drove her as much as her kindness and wisdom and generosity led her.

At some point in that evening in 1988 Fergus and I became conscious of the wind snoring through the taped-over gaps in the lounge windows, and the curtains puffing and strutting. What nerds we were, inviting the celebrated writer to stay because it might be nice for her to have conversation about books and writing. So we nervously began to tell her about the flat, which was in this state of dilapidation because it was part of the long-disputed estate of the madam who had run most of the brothels in World War II Wellington. “This was once a brothel,” we proudly said. The wind got up even more and the unsecured weatherboard began its thumping. We apologised again and Margaret said how appropriate it would be to have a disturbed night in an old brothel because of a loose bawd.

Oh, she would pounce upon a pun! No pun had any hope of escaping her catlike attention. She’d make a joke, and then laugh at it herself–and her laugh–croaky, deep, warm, piratical–always urged everyone else to laugh even more.

It’s hard to describe what she was like to listen to. What she’d say–you can get the tenor of that by reading the talks and essays in A Dissolving Ghost. But the thing was, she could talk like that off the cuff with only a little less structure and polish. I think of the many times I’ve seen her on stage, in conversation or being interviewed. While her manner always put people at ease, because, whoever she was talking to, she’d treat them the same–or perhaps it was that she’d find exactly the right level to communicate and still be the authentic Margaret. However, in those interviews or staged conversations I did sometimes see her interlocutor (great word) ask a question and realise that they were about to receive a peroration rather than an answer. Margaret’s talk would go out wide, springing away from the question like a bird leading a predator away from its nest. But she’d always answer the question, and give the answer the question deserved and required. She didn’t make points, she made maps. She didn’t do soundbites, and following her thinking was often like following the flight of a bird through a forest to find that the bird isn’t being birdy–no, the bird is a little god that stitching the forest together.

While I’ve been writing this I’ve gone to my shelves to find books I need: The Changeover and The Pirates’ Mixed-up Voyage and The Other Side Of Silence (my favourite book of hers). They are missing. Who has them? Really, who has them? And I’ve been delving into my files to find letters. I found one to a friend describing how “the best thing about our trip to Christchurch was meeting Margaret Mahy”. “She came to our hotel room with her daughter Bridget, and Bridget’s being there prevented me from too much gushing admiration, because I was worried I might embarrass them both.” And I’ve found letters from Margaret–letters that are models of Margaretness–so keen and kind.

I’m thinking of her laugh, her hats, her dogs and cats, her winter coughs, her knitted coats, her rainbow wig, and very imposing penguin suit. I’m thinking of her long sentences and pithy quips; of the rose window of the top bedroom or her flat in Cranmer Square; of her empty refrigerator, of her very model of a modern Major General and, in the same vein, her virtuoso “Bubble Trouble”, and the loving rapture in her grandson Harry’s eyes when he watched to perform it at the launch of Tessa Duder’s book.

Charles Dickens was probably Margaret’s favourite writer. So I’m also thinking of the beginning of David Copperfield: “Whether I’ll turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.” Margaret had absorbed and understood the whimsy and seriousness of that. I am curious to know what she decided about it, if anything, towards the end of her life in regards to herself, especially since so much of her idea of a large and full life was one with a great measure of something self-forgetting–her story-telling and writing. But, anyway, I can say with certainty that she was one of the great heroes of my life. Of our lives.

From a letter, May 1991.

“I expect your house in Aurora Terrace really feels like home now. But houses can be altered so easily. I have just acquired a puppy and it makes me think of the house differently, as a series of dog places and non-dog places, depending on the time of day. Nothing stands still for long, even when it has foundations and four walls.”

June 11, 2012

My post-Leipzig talk

In March of this year ten writers and six publishers from New Zealand were at the Leipzig Book Fair, on the Frankfurt Book Fair’s stand. We were being introduced to German journalists, publishers and readers as part of the preparations for New Zealand’s appearance as Country of Honour at the Frankfurt Book Fair this October. When were were home again the Wellington contingent—me, Fergus Barrowman, Jenny Patrick, and Damien Wilkins gave talks about the experience. This is mine.

First I’m going to say I had a wonderful time in Germany and the thronging exhibition halls of the Leipzig Book Fair were an eye-opener. Everyone concerned with our trip performed energetically, gamely, and bravely—or some of that and in character in the case of Alan Duff. I had a few fans who came to my appearances to get their copies of Der Engel mit den dunklen Flugeln signed. One of them, to my delight, was dressed up as Carmen San Diego.

I’ve had two books in German, hardback and paperback, both out of print now due to the vagaries of publishing companies swallowing each other. But, that said, I’ve been doing this for a long time now and have, as far as editions of books go, the usual long campaigner’s proportion of spent shell casings to live ammunition.

This talk is about being in Leipzig, but its subject is possibly the recession, and how we talk about what we do.

One night when we were in Leipzig, Fergus and I went along with Damien to a party at the house of Josef Haslinger, head of the University of Leipzig creative writing program. The party was for the students and two visiting writer faculty members from their partnership school at Columbia University New York.

Josef Haslinger’s house was on the fourth floor of a building in a suburb full of converted Eastern Block factories beside one of Leipzig’s four rivers, which Haslinger told us in August would echo with the voices of people in dingys and kayaks. The house was double glazed and had two terraces, one for the smokers with ashtrays, and tea lights which stayed lit—something that never happens with candles on the deck of our villa in Kelburn. I was appreciating the windlessness and double glazing and, as I do, looking around and thinking, “People live like this.” I’d recently seen dusty courtyards off quiet alleys—Hutongs in Beijing—and high-rises studded with air-conditioning units dripping black mould in Shanghai, and had thought, “People live like this.” It’s never pejorative. It’s not envious. Nor am I location-shopping for fiction. But every difference represents one more thing to explain about what’s familiar to me. For instance I can say “Our Villa in Kelburn” to you Wellingtonians and I don’t have to do a whole lot of describing after that. Differences require description—and description is out of fashion in books. (Fair enough, since we can Google all terms of reference, and there are certainly those who think that all imagery is just fancy terms of reference.)

When I travel I’m being alert, and also half asleep. Half asleep because part of me is always registering that going to a foreign place is like going to the future—you’re somewhere you’ve looked forward to, but where you have no say or influence. You’re a ghost. Or you’re in someone else’s story. At the same time I often get to see things I’ve absorbed from books and films, and sometimes feel I’ve waited for my whole life. Like the spring thunderstorm Fergus and I got caught in in the gardens of the Nymphenberg Palace just outside Munich, when planetary thunderheads, so big and dense they looked like they should have their own gravities, came together and squeezed the sun. There was sunburst. A corona of light and filmy grey shadows bristled in the little bit of blue sky between the clouds. Then blue went green, and we heard a slow-motion rockslide of thunder, and felt and saw the first ‘plops’ of rain. We don’t get raindrops that size. Foreign raindrops; coins I can’t spend here.

So here’s me in Leipzig, at Josef Haslinger’s house, eating black bread and frankfurters. We’re hungry because we didn’t eat enough of the nibbles at the Leipzig Museum, where the New Zealand string quartet were playing. I’m still thinking about the museum and the music and walking behind the moment—pretty much the same way I walk behind Fergus when we are out on a long ramble. I always start plotting something, and if I’m behind him he can deal with obstacles and oncoming people, and never mind that he ends up feeling like a cow with a calf, or one of those patriarchs whose wives always follow a step after him. I can’t be expected to think and steer myself.

What I’m thinking at Haslinger’s party, and will go on thinking throughout our German trip, is something like that there’s room for everything, but not now, not at the moment, and whatever you look at could be different. I’d just seen old musical instruments. Old pianos, from back when there was no accepted size or shape for them and a buyer might have asked for one to fit the corner of a particular parlour. I’ve seen the museum building itself—made from pink stone quarried somewhere near Leipzig. It had fossils in it. I dropped a nibble and it landed on a black glyph in the flagstone at my feet that was really a prehistoric centipede. When we were in the taxi on the way to the museum we’d passed the University and a building made of steel and glass, and, and sockets in the steel, the rose window, pillars, and Gothic arches from the old cathedral that was wrecked during the unrest in 1989. I was planning to go back and photograph it and tweet it for my Christchurch followers to show them what’s been done with rubble, and old stones in new settings. I was feeling proud of the string quartet. Their Death and the Maiden had earned a standing ovation from the Germans. I was feeling proud of Michael Norris whose piece they played first. He teaches at Vic and though he’s on my back doorstep I hadn’t heard of him before. I was moved and excited by his Exitus.

Josef Haslinger, Damien, Fergus, and another German writer are talking about New Zealand’s being country of honour and how Fergus is spending his days talking himself hoarse on behalf of his authors—and how he feels a bit awkward doing so because Leipzig isn’t really a Rights fair, with selling, and he’s rudely—he feels—trying to sell. Ten writers and six publishers are at the Leipzig Fair on the Frankfurt Book Fair’s stand. We are introducing New Zealand—country of honor at Frankfurt in 2012.

Fergus is saying that there is a very short lead-time. “Translations take time we might not have.” He’s concerned that New Zealand might end up being represented only by what just happens to already be in translation and in print—or pending. “Of course we can curate what appears around that,” he says.

I’m standing next to him shrugging. My “What can you do shrug”. Then I’m nodding because he’s saying, “We can only do our best.” I’m nodding because of how important all this is. I’m shrugging because when I was talking to someone that very day about the ideal of New Zealand literature being well presented at Frankfurt they said, “Well, Elizabeth, it’s a book Fair not a literature Fair.” Which, of course, has the virtue of being true.

I think of something to say. With my usual apparently beside-the-point scene-setting: “When Damien and I were in the Messe tram the other day with Claudia from the Frankfurt Book Fair she was talking about how few German books make it into English. And how many books in English are translated into German. That Germany is on the downstream end of the flood of books in all the Englishes. Or, actually, books from New York and London and whatever makes it through New York and London.”

The other German writer’s eyes light up. “Yes,” he says. “That’s true. You have to ask yourself: does my book need to be translated? Why should my book be in German?”

And—at that moment—with the bread and frankfurter working their magic on my blood sugar, this struck me as a rather delightful and liberating question.

One of the wonderful things about Leipzig the city is, in fact, the gift of failure. In the years after reunification around 50% of the city’s population moved away. Leipzig is full of empty buildings. There was one grand old hotel near the Hauptbahnhoff that nearly got me killed because I’d be staring at its name in perplexity while crossing the road. The Hotel Seaview. The Hotel Seaview translated from the seaside by an Eastern Block hotelier. There were falcons nesting at the top of our taller hotel and we still couldn’t see the sea from there. Most of the empty buildings in the depressed Leipzig have been preserved. Now they’re being slowly bought up and restored. Leipzig may not boom, but it will grow and be beautiful.

Because of where history is at we have all spent our adult lives with talk of success at the centre of much our talk. And we’re still doing it, like birds awake when they should be asleep and singing in the light of a distant forest fire. I was lucky to see those Hutongs in Beijing. Most of them were leveled for high-rises. The people from the vanished neighborhoods gather after work in parks near to where they once lived. They get together and do ballroom dancing, which keeps them warm on late-winter nights. Success can erase things as effectively as failure. That’s what I was thinking about when I left the party. That all any empty building says is: “Not now.”

We were at a party. Our hosts were generous and gracious. The food was good. We imagined the lives of others. We remembered things we already knew like how quickly some literary folk from New York can work out that they don’t need to talk to you. We exerted ourselves for ourselves and others. Damien tried to get up something reciprocal between Haslinger’s program and the IML in Wellington. Fergus talked himself hoarse. We walked down four flights of stairs. The tram floating down the dark street like a lit barge was the wrong tram. But taxi drivers all speak English. The glyph in the pink stone was once alive. And rain coins have no face value, they might be worth anything or nothing.

April 11, 2012

In purgatory stories are street lamps (1)

I thought it might be easiest just to post the lovely photo of Mum from her order of service (it’s on my facebook). But then I wrote this.

Over the past few years it’s been family, friends, and fiction for me. They were all a challenge, and all sustained me. I want to write a bit about the fiction, and some of the things I watched and read that got me through. I’ll start by reflecting upon why those things and not others. Why th0se books, films, TV—all superior entertainment, all very good of their kind, and all very different.

One of the things you hear people say when they’re discontented, and hard-pressed, is that they don’t have the energy for anything difficult, sad, or dark. “I just want diversion. Something that carries me away.” I been thinking about how “diversions” work in our times of crisis (and of waiting). I thought how, years ago, during a relationship breakup, my sister told me that she got through her hardest night by watching John Ford’s The Man who Shot Liberty Valance, watching John Wayne call Jimmy Stewart “Pilgrim”, watching a story that says—among other things—this: Just because something comes to an end that doesn’t mean it wasn’t real, or in itself the heart of a story. I thought of that, and I remembered my son at 18 months, the night before he had grommets put in his ears to save his hearing, already brewing another ear infection and up all night, lying on the couch, flushed, tearful, and exhausted. We were watching Disney’s The Jungle Book for the first time, and when Baloo began to sing “Bare Necessities” Jack got up off the couch to do a smiling, tearstained dance, because the invitation of the music, and Baloo’s performance, was irresistible to him. I was thinking was that we have this wonderful ability to be comforted by the life we see in art. And how it’s not simply a matter being diverted. Art isn’t an analgesic. It’s more like a temporary cure.