Nicola Griffith's Blog, page 67

April 13, 2016

Nic is dead

Helena Carmel Griffith, 13 April, 1964 – 22 September, 1988. Photo by Heidi Griffiths (no relation), 1983.

My sister Helena would have been 52 today. She died when she was 24. Today I’m reminded afresh that she never read any of my books. She never met Kelley. She never saw my life as it is now. She is embedded in almost every memory of the first half of my life; we shared experiences no one else can. When she died she took a chunk of my life with her.

Spring is a grief-laden time for me: the birthdays of my mother and two sisters, all dead. They were the only three people in the world who ever called me Nic.* Now that they’re dead, Nic is dead too.

Nic is dead. That sounds final, like running into a wall or having my life sliced in half by a slamming blast door. That’s not how I feel. I feel as though there’s a door open—upstairs, down the hall, out of sight—to a room whose window is open to the night air, creating a persistent thread of disturbance.

But that, I have decided, is what life is: the unmade bed, the unsealed jar, the unfinished journey. Life is imperfect, unsettled. Life is to be taken on the volley. Nic is just part of Nicola. Nic might be dead but Nicola is just getting started.

Life is to be lived. We can never know who or what is around the corner.

* I have two others sisters and a father, very much alive. I love them, but they never called me Nic.

April 9, 2016

New $50,000 prize for stories about women

There’s a new literary prize: $50,000 cash for a short story, novel, or screenplay written in English—in any genre—that portrays one or more well-rounded female protagonists. This, as anyone who reads this blog knows, matters to me. Stories about women, stories about women as real people, human beings in, of, and for ourselves are vital to building and growing society. Women’s stories matter and are often devalued.

The Half the World Global Literati Prize is “specifically designed to put the spotlight on real female characters and positively impact how women are represented in contemporary writing.” They are looking for “work that gives fresh insight into the lives of women.” It’s a pretty interesting line-up of judges:

Anne Harrison, producer for the Oscar, BAFTA and Golden Globe nominated film The Danish Girl

Dr Lisa Tomlinson, scholar, cultural critic and professor of English literature at the University of West Indies

Margie Orford, internationally acclaimed writer, award-winning journalist, and President of PEN South Africa

Gina Otto, best-selling author of Cassandra’s Angel and founder of children’s social activation platform Change My World Now

Kenneth Goh, well-respected Editor-In-Chief of Harper’s BAZAAR Singapore

K.F. Breene, international best-seller of the Darkness and Warrior Chronicles series

Michael Marckx, lecturer, writer, environmental activist and former CEO of Spy

Debra Langley, Executive Director of Half the World Holdings.

This reasonably diverse crew are looking for unpublished work in one of three categories:

Short story (up to 7,500 words)

Novels (40,000 words or more)

Screenplay (for a movie or episode of a TV show)

All entries “will be judged on a mixture of factors; concept and originality, structure and pacing, character development and dialogue, creative flair and commercial potential.” Each entry (you can submit up to five) costs $20. Winners get $50,000 (US dollars) plus “the opportunity for a publishing or film production deal with our world-renowned partners.” It’s a little unclear what this means, exactly, but as the winner keeps the copyright in their work, I’m cautiously optimistic. (Read the full rules here.)

The deadline is 8 June. Enter here.

April 8, 2016

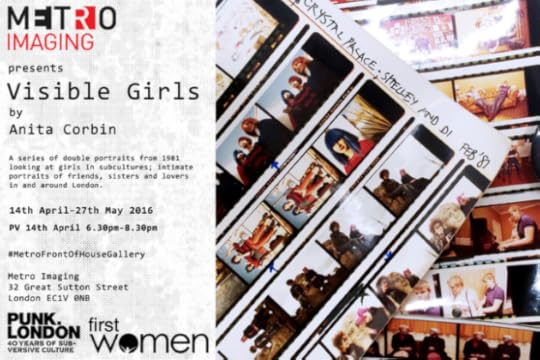

Save the date, 14th April, London

Anyone who is is London between 14 April and 27 May can see this photo of me writ large at Metro Imaging at the Visible Girls exhibit, “A series of double portraits from 1981 looking at girls in subcultures; intimate portraits of friends, sisters and lovers in and around London.”

Apparently the BBC (David Sillito, arts and media) will be covering the opening night so even though I can’t be there I’m hoping I get to see something of it. If anyone reading this can snap a photo of the exhibit I’d love to see it.

In honour of the occasion I spent an hour yesterday searching my hard drive for, converting, and tidying a second photo of me and Carol taken by Anita in 1981. It’s a very old scan so forgive the quality.

Me, a baby-faced 20, with Carol at the first UK Lesbian Conference, 1981. Photo by Anita Corbin. Scanned from an old book, Girls Are Powerful. Not the photo used in Visible Girls exhibit.

March 31, 2016

Intersectional weight penalties — 2015 VIDA count

Yesterday, VIDA published their 2015 count of over 1000 data points from the top tier literary journals to examine bias in the publishing industry, or at least part if it. This year, the count goes intersectional. They asked women writers who published with those top tier literary journals to take a survey on how they identified, looking not only at gender but at race and ethnicity, sexual identity, and ability.

I’m absolutely delighted that VIDA is folding in intersectional bias. I’m dismayed, though, at how few women writers are succeeding while carrying more than one penalty. (I think of each degree of departure from the Norm—Norm being straight, white, cis-gendered, male, and able-bodied—as a weight penalty, a bit like horse-racing. Only in this particular race the favourites carry less weight, not more. The unfavoured—the seriously Othered—must run the same course, leap the same hurdles as the Norms but carrying extra weight in their saddles. Add one kilo for being a person of colour, one for being queer, one for being trans, one for being disabled. Or, if you prefer, think of it as living under increased gravity. See “The Women You Didn’t See” for more on this.)

However, there was a relatively low response-rate on those surveys, which makes the data a wee bit less robust than I’d like. (I’ve no doubt that as women get used to the survey the response-rate will rise.) But this is a great start. For the first time we get to peek into how (if) women writers are managing with what degree of weight penalty.

Sadly—unsurprisingly—from this preliminary data, it’s clear that there are very few women being published in these journals who manage to surmount more than one degree of extra difficulty. I found myself eagerly searching for those like me—women writers who are also queer and crippled—because it really helps to know that there are others who have broken past multiple barriers to entry, that it’s possible to run the tortuous literary course carrying extra weight. But we have no idea whether those who responded are representative. Perhaps the percentages of those successfully carrying weight penalties is even lower than it appears.

Also, there’s no data on how many of those women reviewed were writing about women, or on what percentage of women chose to review other women and what percentage chose to review men. In other words, I’m none the wiser about the change, if any, in the perceived importance of women and women’s stories. And I think this information is vital.1

The news, though, is generally encouraging; most journals are improving their gender ratios (though The Atlantic is backsliding).2 To steal VIDA’s own phrase, this count makes me feel cautiously optimistic.

1 However, it’s much more time-consuming, not to mention subjective and so open to argument, to count protagonists. Having done it myself I understand how perilous the venture can be. The Literary Data group has ground to a halt because I have no had the time to pay attention to it. I still occasionally count things. Last year’s Booker Prize Shortlist appalled me: the novels were wonderfully diverse in terms of race but overwhelmingly about men. And when #OscarsSoWhite trended I thought, “Yeah, Oscars so Norm,” did some counting, and found (shockingly—not) that films about women hardly ever win big awards.

2 Women’s share of micro-reviews has gone down; we are less likely to be regarded as meriting only a little review. In review world size really matter, so this makes a difference.

March 29, 2016

Allies make diversity happen

According to the Harvard Business Review, women and people of colour in leadership roles are penalised for trying to diversify the workplace. White men are not.

Stephanie K Johnson and David R Hekman write that 85% of corporate executives and board members are white men—and that the proportion hasn’t changed for decades. The authors suggest that this is because white men keep choosing and promoting other white men. They did a study. They found that diversity-valuing behaviour results in diminished performance ratings for women and people of colour.

We seek to help solve the puzzle of why top-level leaders are disproportionately white men. We suggest that this race- and sex-based status and power gap persists, in part, because ethnic minority and women leaders are discouraged from engaging in diversity-valuing behavior. We hypothesize and test in both field and laboratory samples that ethnic minority or female leaders who engage in diversity-valuing behavior are penalized with worse performance ratings; whereas white or male leaders who engage in diversity-valuing behavior are not penalized for doing so. We find that this divergent effect results from traditional negative race and sex stereotypes (i.e. lower competence judgments) placed upon diversity-valuing ethnic minority and women leaders. We discuss how our findings extend and enrich the vast literatures on the glass ceiling, tokenism, and workplace discrimination.

This tendency towards like-promotes-like occurs in many spheres beyond the corporate world—for example, academia, publishing, and politics—and to other discriminated-against groups.

We are all allies. Even those of us who belong to several oppressed groups have, in some situations, rank and power that some others don’t. Perhaps we’re able-bodied. Perhaps we’re straight. Perhaps we’re white. Perhaps we had a decent education, or have a fabulous income, or married. Rank, power, and privilege is always relative. In any given situation sometimes we have more, sometimes we have less. If we have more, we can be allies of those who have less.

As allies we need to step up on others’ behalf. This study shows that those who are being discriminated against are likely to be devalued for trying to change that; those who have rank and power are not.

My business is mainly books. Today that’s my focus. Here are five suggestions for what allies can do in the next month:

Take the Russ Pledge

Support We Need Diverse Books

Go to the Disability Lit Consortium booth at AWP; support the AWP Disability Caucus

Take the SF/F Convention Accessibility Pledge

Support Lambda Literary’s LGBTQ Writers in Schools programme

That’s just off the top of my head. There are many, many ways to support diversity. These range from occasionally saying something, to not using thoughtless language, to giving time or money or attention. The more rank, power, and privilege you have as an individual or a group member, the more opportunity you have to help. No matter who you are you will find some situations where you have more heft and influence than others. So step up, speak out, put your money where your mouth is. Do what you can. Make a difference.

March 1, 2016

Writing Slow River

Current US cover (Ballantine/Del Rey), current UK ebook (Gateway/Orion), original US cover (Ballantine/Del Rey), current UK print edition (Gollancz Masterworks), original UK edition (Voyager/HarperCollins).

Slow River comes from the intersection of two different experiences, both of which changed my perceptions of myself and my place in the world. The first experience was when I was eighteen, the second almost ten years later.

I was born in Leeds which grew to its present size during the textile revolution. It is now a bustling regional financial center. I was raised in a very conventional white middle-class Catholic family, and taught to always obey the rules—stay within the system and the system will protect you. I did not know that there was any other way to live. And then when I was eighteen I ran away from home to live with my girlfriend in another city, Hull. I stumbled from three square meals a day in a conventional lower middle-class atmosphere of wall-to-wall carpets and central heating into another world.

In Hull—a city whose economy was failing and drains collapsing—I had no job and no money. No belongings. No security or safety. My lover and I were hanging with bikers and drug-dealers and prostitutes. I submerged myself in this new reality utterly. It was all very exciting. Very adult. Begging for food and selling amphetamines for a living felt like a radical act: I was hardcore. Rules were for other people. I was above all that. I was different. This lasted for a few years, and then one day I woke up and realized that this was no longer a phase, or a game, or a diverting interlude; it was my life. This starving, cynical, uncomfortable, and dangerous existence, in a hopeless and declining city, was all I had. So I struggled to climb out of the pit. And as I struggled, I looked around me and wondered why all the other people I knew in similar straits were not struggling to climb, too. I began to wonder: what makes some people want to change, and others not? How come two people who seem to be faced with the same choices, with access to same resources (i.e. apparently none), make two different decisions? People, I understood suddenly, are not all the same. We are never in the same situation. We might seem to be, but we come from different places and have different experiences of the world. What looks like the same situation is, most often, a fleeting moment of crossover/coexistence. I came from the middle-class—admittedly the lowest rungs, but still I had been raised with a particular set of expectations, education, and values. Not everyone is so lucky.

In 1988 I came to the US for the first time to attend Clarion, a six week writing workshop at Michigan State University. As I flew over the cumulus clouds of the midwest, it occurred to me that there was not a single person on the continent who knew me. The sudden sense of being outside the world, of not being bound by ordinary rules or people’s expectations, was exhilarating. I could land and be anyone I liked. No one would know any different. But then I realized that this hiatus in my ordinary life gave me the opportunity to play a much more dangerous and high stakes game. I could find out who I really was. Me. Not me-and-my-family, or me-and-my-education, or even me-and-my-accent, just Me. Without the usual identifying cultural markers, my fellow students and teachers would have no choice but to evaluate me on the basis of now. And by doing that, they would form a human mirror. For the first time, I would see my essential self, stripped bare.

Is there such a thing as an “essential self?” I have no idea. But the idea fascinated me. If there is, where might that essential self originate? Can it be warped, encouraged, or destroyed? How far outside the moral and physical boundaries of that essential self would I we be willing to step in order to stay alive? And—if we stepped so far out that we became someone we did not recognise or like—would we still be us? I wrote Slow River to answer those questions.

Slow River is set in a near-future urbanscape. It begins with a woman, Lore, who is kidnapped, then dumped, nameless and naked and hurt, in the dead of night in middle of strange city. She has no name, no job, no money, and no clothes; no friends or family or support system; she can’t go to the police because she believes she has killed one of her kidnappers. How far will she go to stay alive? And what will happen on the morning she wakes up and finds she can no longer face the person she’s become?

The book is set in the near future, and deals peripherally with information technology. As a result, I’ve often seen it described as cyberpunk but I’ve never thought of it that way, perhaps because I associate cyberpunk with nihilism. While Slow River is as realistic in its depiction of urban lowlife as I could make it, it’s also full of the beauty and hope (and absurdity) of everyday life: sunshine and the way it changes the texture of stone-clad buildings; the taste of a hot, fragrant cup of tea; the eyes of a squirrel balanced on a power line…

Lore is the youngest of three siblings born to Katerine and Oster van de Oest, the owners and officers of the very rich, and very powerful—but still family-owned and -controlled—van de Oest corporation. The family made its money from patenting genetically engineered bacteria and fungi—and, importantly, the nutrients they need to live on—which are used in various bioremediation processes. Primitive bioremediation is already with us (think oil-gobbling microbes that help clear up oil spills), but in my near future I took the technological very much further. I had a fabulous time imagining solar aquatics: the transformation of sewage into clean drinking water, edible fish and recycled heavy metals without the addition of harsh chemicals. It was thrilling to figure out what it might take to return the Kyrgyz desert from its dioxin-riddled failed-cotton monoculture wasteland to its steppe state using six hundred-foot high heliostats, artificial waterfalls, and glass pipelines hundreds of miles long.

Writing Slow River used all that I knew and understood in 1993. There are descriptions of and opinions on: personality, a kidnapping, hot but science-fictional sex, nanotechnology, prostitution, growing up, dangerous and potent aphrodisiacs, illegal media piggyback scams, pornography, fashion, the responsibilities of the rich to the poor, fame, vice, survival and much more. Some of it has turned out to be true; some, eh, not so much (I missed social media completely).

◻︎

Slow River is fiction, I made it up. But I took the premise seriously. To get worthwhile answers to the questions of Lore’s essential self, I would have to show where Lore came from and how she found herself in her present situation. I had to include Lore’s background, history, and upbringing as well as her current dramatic situation. I wanted to show why she was not, in fact, in the same situation as those around her, even though she might, from an outsider’s perspective, seem to be.

I’d been thinking about the book ever since that first visit to this country in 1989. I knew I didn’t have the skill to do justice to the vision. But at some point I just had to begin.

I wrote the first ten thousand words twice and threw them away. Then wrote the first thirty-five thousand and stared at it, and despaired. It wasn’t working. It wasn’t working at all. The narrative had become hopelessly muddled with flashbacks piggybacking on flashbacks, and dizzily escalating dream and nightmare sequences. Emotionally it was a mess. Each time I sat down to work I felt queasy. The more I tried to consciously wrestle the book into shape, the worse everything got. It wasn’t until I’d given up—or thought I’d given up—that I found the solution.

Kelley came home from work one night and found me sitting in a heap on the living room floor.

“How did your work go today?” she asked.

“It’s crap. I’m crap. I can’t write. I’ve given up. I’ll have to find a job.”

I meant every word; my life, as I understood it, was over. Once Kelley saw that I was utterly serious, that I could not be consoled, she disappeared into the kitchen and after a long moment re-emerged with two frosty Dos Equis.

“Okay,” she said. I looked up. She held out a beer. “This is a magic beer. When you reach the bottom of the bottle everything will be better. You’ll find out how tomorrow.” I stared. “Trust me,” she said. “Just drink the beer. It’s magic.”

I drank the beer. About one swallow from the end, I felt a stray thought break my brain surface and arrow back into my subconscious. I trusted the magic, though, and didn’t pursue it. In the middle of the night I woke up thinking, “Brazzaville Beach!” (Brazzaville Beach is William Boyd’s novel set in the Congo and written from two different points-of-view—both from the same character, one in first and one in third person.) And the solution lay there, whole and perfect, in my mind. The next day I deleted those thirty-five thousand words and began again.

Instead of two points-of-view I used three, though all were Lore’s. I used first person past tense for the narrative present (A); third person past tense for the immediate narrative past (B); and third person present tense for her childhood (C).

Present tense is the language of dreams, of dissociation and dislocation. It is malleable, the tense of events to be reviewed and interpreted later. It seemed suitable for a childhood that, in comparison to Lore’s present situation, was almost a fairytale—at least on the surface. Let’s call it layer C. Past tense, on the other hand, is much more concrete: this happened. The events described are not open to interpretation—just right for layer B, Lore’s immediate past. I wrote this section in third person because she is looking at it from a little distance; not the same distance as her childhood but no longer quite who she is in the narrative present. The main layer of the novel, though, A—the one with which we begin and end—is in first person. This is the mature Lore, the one who is working out how her childhood, her immediate past, and her present, fit together. This is the voice that decides, the one who chooses, the one with agency.

Slow River is a very deliberately layered book because that is how I have come to view the world. Details of Lore’s character are lacquered one on top of the other, each revelation seeping through to stain the next, each informing the whole. Layering forms not only the narrative structure, but also the predominant image of the novel. Lore knows the different strata of a bioremediation plant because she has, literally, been different people. Lore has been rich and spoiled. She has been a thief and a prostitute. She has been a kidnap victim. She has been a lowly grunt in sewage processing plant. Lore learns the city from a range of perspectives and finds out that the city is like a jungle, each layer having its own predators and prey. She understands where the power in each milieu lies, and how those milieux interact.

The greatest challenge for me, technically, was to layer these narratives in such a way that they reinforced each other emotionally, while also situating the reader, making sure they always knew what part of Lore’s life they were in, emotionally, timeline-wise, and geographically. To help with that I built a formal pattern that I knew a reader’s subconscious would recognise: a recurring ABA C ABA C ABA… The readers’ brain, I reasoned, would learn to expect various time and perspective shifts, and relax.

I wrote each viewpoint in chronological order.I don’t remember how long it took me to actually write. Not long, I suspect. I was moving through an ecstatic dream. Then I printed it and chopped everything up (literally—when it comes to think kind of work physical paper works better for me than screens), spreading it out all over the living room, dining room and hall floors, then splicing it all back together. Undoing. Redoing. That took two solid weeks of twelve hour days accompanied by curses at playful cats and petulant glares at Kelley when she told me it was time to eat. (And one particularly horrible day when she flung open the front door, announced, “Honey, I’m home!” and set a whirlwind loose on my carefully arranged piles of paper, destroying all the work I’d done so far.) But eventually I had it all arranged to my satisfaction: emotional chords and plot lines harmonised, character development and reader movement through the book followed pleasing peaks and troughs.

I printed the final draft. Gave it to Kelley. She read it, burst into tears, and told me it was brilliant. I beamed and told her she gave good beer. “Oh, god,” she said, “I was so scared that day, I didn’t know what to do, I’d never seen you like that before. The magic beer thing was sheer desperation.”

◻︎

Technically, Slow River owes its initial inspiration to Boyd. Structurally, it is my own. Texturally, the book is a direct descendant of those historical novelists I refer to as the English Landscape Writers—Rosemary Sutcliff, Henry Treece, and Mary Renault. I want a reader to be able to pick up the book, open it at any page, and know immediately the smells and sounds of a character’s surroundings; the taste of the wind, if there is any wind; the ambient air temperature. I want the milieu to say something of the character surrounded by it. Emotionally, I want Slow River to feel, well, like a river. A river in its many phases: cold and thin and bitter; smooth and deep and dangerous; big and glad and energetic.

I wrote Slow River for myself, to answer those early questions about the essential self, but I also hoped lots of different people—men and women, gay and straight, those in search of serious literature and those wanting a beach book—would pick it up and give it a go.

Slow River is science fiction: it’s set in the near future and the plot revolves around a technology that is (still) in its infancy. But I’ve seen it described in a variety of ways—a novel about sex and industrial sabotage, lesbian fiction, a picaresque whodunnit, a page-turner about corruption and corporate dynasties—and I don’t really care, as long as readers approach it with an open mind.

In March 1995, three months before the book came out, I was at OutWrite, the lesbian and gay writers’ conference in Boston. I was appalled by the ignorance and prejudice on casual display. At the end of the conference I took my last two advance reading copies of Slow River to the exhibitors’ hall to get rid of so I didn’t have to lug them back to Atlanta with me on the plane. I approached a woman at one of the booths. She will remain nameless, but let’s just say she represented a (now defunct, ha!) review journal. I said hello and asked her if she wanted a galley of my new book. She reached out a rather disdainful hand.

“Well, I’m sure there’s someone in our office who likes this kind of thing.”

“What kind of thing, exactly?”

“You know, rockets and ray guns and computers.”

“Just try it,” I said, exercising great restraint. “You might like it.”

There are many editors and reviewers and critics like this woman. They will condemn the book without reading it. “Oh,” they sniff, “science fiction,” the same way those who compile the Canon have previously sniffed, “Oh, women’s fiction. Minority fiction. Queer fiction. Regional fiction.” What, I wonder, are they afraid of?

To some extent all fiction is autobiographical. To convincingly describe fear, for example, we have to understand fear, but that fear can be transposed from one key to another. Fear of heights can become fear of snakes. In case you were wondering, I was not born into money, I was not abused as a child, and my mother was not a monster.

Now I know that this despair is just part of my novel-writing process. At least for about half my novels: for Slow River and Stay and Always. Not for Ammonite or The Blue Place or Hild. It doesn’t seem to happen with stories, and it didn’t with my memoir. Why? No idea.

For an example of how I’d like to see the book read, see this review.

This was idiotic. One, fiction can’t make you be anything you have no capacity for, and two, why was I assigning such enormous power to heterosexuality? That was when I realised: this is what some homophobes feel. It gave me a vast new sympathy for those who are/have been homophobic. This shit is real and not initially under our conscious control. But here’s the thing: it’s fixable. Face it and you’ll find you can get over it. As soon as I realised what my problem was, I could laugh at it. Think of it as recovery. Or at least amelioration of the reflexive fear response. I can recommend to every writer the trying on of a perspective you find alien, even repugnant; you might learn something.

When I asked straight writers to contribute a queer story, and litfic writers to contribute a fantasy, science fiction, or horror story to Bending the Landscape my intent was to break down barriers. I admit I had no idea what I was asking of some people. But they came through like heroes. I admire each and every one of them (especially those who went there with someone of the same gender. It’s easy enough for a straight woman to pretend to be a man in love with a man, or a straight man to pretend to be a woman in love with a woman. But for those straight men who wrote from the point of view of a queer man, straight women writing from the perspective of a queer woman, queer women writing about a straight woman, well, I salute you).

February 26, 2016

Voting for Hillary Clinton

Today is my third anniversary of becoming a US citizen. I’ve lived here much longer than that, of course; during the last 27 years I’ve seen some good changes for this country and some terrible ones. I won’t list them here because that’s not the point of this post. This post is about voting.

A country (state, county, city) gets the government its citizens vote for. What this means is that every citizen over the age of eighteen has not only the privilege of voting but, in my opinion, the obligation. It’s your job as a citizen to make sure decent and competent people occupy public offices, people who will write legislation that is fair, well-written, and transparent. In other words, it’s your responsibility to ensure that the polity you live is well run. It’s down to you.This means actually voting. Voting is not tweeting, or ranting on Facebook, or writing angry blog posts. It is not having arguments with friends and family or waving placards at passersby. Voting is completing and submitting a ballot, raising your hand or number at a caucus, or walking to the designated corner—whatever you do in your part of the country. It means getting off your arse and doing it not just talking about it.

Washington State’s Democratic Presidential precinct caucuses are scheduled for Saturday March 26th. As I have MS I qualify as having a disability which means I’m allowed to send in something called a Surrogate Affidavit. So I’ve already voted. It was a shit ton easier than turning up in person and listening to a lot of tedious discussion and uninformed opinion. (It’s one of the two benefits of having a seriously vile illness. The other? Cruising through the airport security line in a wheelchair. Not much to weigh against all the disadvantages of MS but, hey, I’ll take it.)

I voted for Hillary Clinton.

I have many reasons for this but the main one is that I think of all the candidates, from either side, she’d do the best job of being President. If I could have voted in 2008 I would have voted for her. She strikes me as someone who knows how to make things work—a skill for which this country is in dire need. Clinton has practise at maintaining poise under scrutiny; she has good relationships in the Senate and various governments across the globe; and she understands how to manage people and keep them on-side. Importantly—at least to me—she’s a policy wonk.

For more impassioned reasoning, see How Hillary Clinton Won Harlem and Sady Doyle. For a more data-driven assessment see The Upshot on the Clinton-Sanders voting record.

This will be my first vote in an American presidential election. I like to think I’m making an informed choice. But the point is that I am making a choice. If you’re a citizen so should you. We don’t have to agree on that choice but, hey, voting is a citizen’s superpower. Why not use it?

February 15, 2016

Morning after

We tend to celebrate most things, and we often do it with wine, almost always with splendid food, and every single time with conversation. The conversations continue: they grow and change, get added to and rethought over the years. Conversations ebb and flow, lapping at our lives with a reassuring rhythm.

The wine, sadly, goes. One of our favourite wines is Pio Cesare Barolo. I’ve written about it before (see, for example, sixteenth wedding anniversary). But as each bottle is completely different, each has a special memory built around it. Last night’s was particularly delicious. I’ll remember it for a while, and smile.

In the cool light of February morning, what’s left of a fabulous evening.

February 14, 2016

Four-word love story

Then there she was…

If you want the longer version of this story, you can find it in my multi-media memoir, And Now We Are Going to Have a Party: Liner notes to a writer’s early life. If you want to see it from Kelley’s perspective, take a look at our joint essay, As We Mean to Go On.

February 8, 2016

Intellectual judgement buried in the syllabus

This is interesting1: a whole graduate class at Texas A&M focused on Hild to illustrate medievalisms in British literature as a major movement. Hild is also being used at King’s College London in an MA course on the Contemporary Medieval, and in a couple of other places. It’s been my experience that for every course I hear about, there’s at least one other that I don’t, which means that Hild is probably being taught in half a dozen institutions this year.

Hold that thought.

Last August I came across English Literature By the Book, a look at the texts set by OCR, a “leading UK awarding body” that “provide GCSEs and A Levels in over 40 subjects and offer over 450 vocational qualifications” for the UK’s GCSE English Literature examinations from 1988 – 2015. In the UK, GCSE study begins when the student is about 14. So the formalisation of what is “important” literature begins early. And according to these statistics the literature that UK schoolchildren are taught is important is largely by and about men. Women wrote 29% of the prose set texts.2 (I have no idea what percentage of those books are written by women are about women. If anyone is willing to investigate further I’d be thrilled.). ELBTB doesn’t break out race of the authors but they do list nationality; it’s pretty clear the writers are overwhelmingly white. Sexual orientation is not even mentioned.3

A couple of weeks ago, I heard about the Open Syllabus Project, an “effort to make the intellectual judgment embedded in syllabi relevant to broader explorations of teaching, publishing, and intellectual history.” Essentially, the project has scraped the metadata from over a million US university syllabi and built something called Syllabus Explorer so that anyone can look at and play with the data. Naturally (hey, writing is a vainglorious profession!) I looked for Hild. I found nothing. So clearly the system isn’t perfect. But it’s still pretty interesting. People are already using it and coming up with broad trends of what’s being taught where. For example, the Washington Post have put together a comparison between the ten most-assigned books in the Ivy League and those assigned in universities as a whole. There’s a little overlap so instead of 20 titles there are 16. Of those 16 only 3 are by and about women, and only 1 by and about people of colour. White men rule.4

School, at all levels, is where we learn what’s important. We are still being taught, in the UK and US at least, that white men’s perspective—what white men think, how white men feel, and what white men believe—is overwhelmingly more important than any other. If you wonder why writers self-censor when it comes to subject matter, if you wonder why judges award literary prizes to novels by and about white men, look no further.

If you are a teacher at any level, consider putting effort into changing this. Consider what you can do to change the syllabus—any syllabus, all syllabuses5—to mirror the diversity of the world.6 Apart from the purely personal thrill of seeing Hild taught (and it really, seriously is a thrill) I’m warmed by the thought of students getting to read about a woman who has agency and smarts, who doesn’t suffer any sexual threat from anyone, who loves people of all colours and persuasions, and who always (in the end) wins. There are worse examples.7

1 The only bit I take issue with: “The novel is one that is an historical novel though Griffith is a science fiction author.” No. I’m a writer. Full stop. I’m no more an SF writer than a woman writer or a lesbian writer or a historical novelist. I write everything, but labels are like adjectives; they often diminish the impact of the noun. In this instance they qualify the word writer. I prefer that to stand on its own.

2 That Sexist Ratio again. But note that Drama is far, far worse than Prose: 96.7% of the set texts are by men.

3 Interestingly, page count is tallied: long books outnumber short. Size, apparently, does matter.

4 As with the Oscars and Emmys, it would have been to depressing to count QUILTBAG authors or subjects, ditto people with disabilities, so I didn’t bother.

5 UK and US populations are slightly different. The proportion of women is broadly similar: close to 51% in the UK and a little over 50% in the US. Race, however, is very different: only 18% of the UK identify as people colour whereas in the US it’s twice that, at 37%. In my opinion there are no good estimates of queer populations. Stonewall’s sounds about right, 5-7%. But it’s pretty much a guess.

6I tried writing syllabi, as I was taught. But it just irritated me. So, stylesheet-wise, while I still prefer millennia to millenniums (shudder) this blog is switching from syllabi to syllabuses. (For the record, I’m okay with either octopodes or octopuses.)

7 All my novels have been taught. Interestingly, none of the Aud books show up on the Open Syllabus Explorer.