Nicola Griffith's Blog, page 66

June 17, 2016

The dozen daily delights

After the events of the last week I’ve decided to re-list the twelve daily deeds of delight for health and happiness. Each must be performed every single day. Each must be done without hurry, without thinking about what comes next.

Drink tea. (I like hot Irish breakfast but some strange people prefer it cold, with ice in it, and I’m okay with that, as long as the tea is freshly brewed and not some vile packet thing.)

Eat chocolate. (I mean chocolate not brown ‘candy’, and I most definitely do not, notnotnot, mean Hershey’s; may be combined with drinking tea.)

Drink wine. (May substitute beer.)

Eat a piece of fruit. (I mean fruit, a whole something you could pick from a tree or vine: an apple, a nectarine, a pear; not juice; not sorbet; not a disgusting frozen pie; a plump ripe luscious piece of mouth-watering fruit grown without herbicides or pesticides.)

Eat fresh vegetables. (I mean a brightly coloured, vitamin-stuffed vegetable, not starch, not french fries or creamed corn or frozen peas, but some still-glistening with the dew asparagus, lightly sauted in olive oil; roasted beets and leeks and rutabaga; steamed cabbage tossed in Danish butter and freshly-ground white pepper. Vegetables.)

Have a conversation. (I don’t mean an information exchange about who’s cooking dinner tonight; I don’t mean an online shouting match or politely modulated torment about politics; I don’t mean an angsty confession about childhood trauma, or a monologue about Ruby or javascript; I mean a relaxed, lively, back-and-forth exploration of what gives each of you joy; maybe combined with eating vegetables and drinking wine.)

Have sex. (Why would you do Kegel’s exercises when orgasm is the best way to exercise your pelvic floor? Why would you do step-exercises when you can use all major muscle groups and get a good cardiovascular exercise, with thrills? Why do couples therapy when you can bond the old-fashioned way?)

Get out in the fresh air. (Walking or rolling from the office to the car doesn’t count; I’m talking about the park, the beach, the city at one o’clock in the morning: breathe deep of cool, living air.)

Do nothing, think nothing, say nothing for at least 5 minutes. (It gets easier with practise; beginners should start in the bath.)

Look at something (or listen) with attention—a bird or a beetle, the back of your hand or a glass of water, a shoe or a pencil—until you see something new. (Newness is all around us; trust me, this one puts a sparkle around your day for hours, and it’s a must for beginning artists.)

Read a novel. (May substitute a good poem or two, or a play or script, but not non-fiction.)

Enjoy a glass of cool, clean water and feel very, very lucky.

A bad day is when I do fewer than seven things on this list. A good day is nine or more. A brilliant day is every single thing on the list (some more than once) plus a few extra.

Ponder what makes a good day for you, and do it.

June 12, 2016

Mass murder and the consequences of hate

I woke up today to news that an American citizen went to Pulse, a queer nightclub in Orlando, FL, and shot and killed at least 50 people and injured at least 50 more. This is the worst mass shooting in US history. It was aimed squarely at QUILTBAG folk (and on a club’s “weekly upscale Latin night”).

When and if you talk about this mass murder to others, do say it was aimed at queers. Do mention that it was on a night when Latin culture was being celebrated. This is a hate crime.

Rather than discuss this murder in detail I’m reposting something I wrote three years ago about the personal consequences of growing up queer and hated.

Hate is still thriving out there. We still have a lot of work to do. The best way to start? Talk about this. Talk about it clearly: this mass murder is not about gun policy, it is not about Islam, it is about the fear and hatred of queerness.

Most people who meet me think I’m lucky to have escaped the prejudice of the world. I don’t look damaged. I don’t look like a victim. I don’t behave—or write—that way.

But every year or two I wonder: who would I be, how might my life have turned out, if I hadn’t grown up facing a strong wind and having to walk uphill?

Some years ago I had a conversation with a friend (she is still a friend; she will remain nameless) who thought that prejudice was a thing of the distant past, something for the history books that maybe only happened to a vague and shadowy group of Disadvantaged. I told her that, no, it happened a lot. It happened to me. She just couldn’t accept it: I don’t look or behave like a victim. I’m not a victim, I said. She asked me some questions.

This is a paraphrased transcript of our conversation.

Well, have you ever been physically injured because you’re queer?

Yes. I was beaten by several men in a club and ended up in the emergency room with a broken nose, concussion, etc. Also, three men tried to burn the house down, and rape me to show me what I was missing. Oh, and someone threw a brick through my window (I got out of bed and cut my feet to ribbons). And two men shotgunned the bedroom window of the flat I’d just moved out of. And, well, the list, frankly, is almost endless. (Seriously, one day, when I have nothing better to do, I’ll write it all down. I bet I could come up with more than a hundred incidents.)

Have you ever been denied education for being queer?

Yes. I had to give up my degree course because my parents wouldn’t fund their part of the cost (this was in the UK before there were such things as student loans). “Why bother?” my mother said. “No one will give a lesbian a job, anyway.” And the fact is, no one would give me a job.

Have you ever been denied benefits for being queer?

Yes. I had to fight for five years to be able to get my Green Card. It cost somewhere between $15,000 and $20,000 (at a time when, between us, Kelley and I were earning less than $30,000 a year; we maxed out three credit cards). My case made new law. It took years to get free of the psychological stress (I had nightmares) and the burden of debt. If we had been legally married it would have been smooth and automatic and virtually free. In addition, I couldn’t get health insurance on Kelley’s employee ticket; this was before domestic partnership provisions. We were monumentally broke. I couldn’t get a job. I was sick. I had no health insurance. All because I’m queer.

Have you been been denied access to healthcare for being queer?

Yes. A gynecologist once tried to refuse me a Pap smear. Also, once in a very scary health situation, Kelley was told she would have no say should anything go wrong. Fortunately, we could leave. We did. (Again, I could make a list.)

There were many other questions with the same basic thrust: Did I really have a hard time? And all my answers were the same: Yes, I really did; I have been harmed physically, mentally, emotionally, legally, financially.

I don’t generally dwell on this. I am not a victim. I am not a pitiable figure. I choose—willfully, daily—to focus my energies on moving forward, on staying open, on interacting with the world as humanly as possible. I’ve seen what it does to those who get bitter and wary and overly defended. They retreat further and further from the mainstream. They become even more Othered. I honour activists who live in the war zone, and I understand those who retreat behind their fortress walls, but that’s not my path. My choice is to remain as undefended as possible, to share—in person and through my work—how it feels to be me, to help others understand and empathise. To be human not Other.

Perhaps because so many of us have somehow managed to weather this tide of prejudice without visible damage it’s easy for some to believe We’re All Equal Now. We’re not. Yes, as a class queers are becoming more politically significant. But those who argue (go listen again to the Supreme Court arguments about same-sex marriage) that we don’t need to dismantle prejudicial legislation right now are wrong. Individuals can and do still have a very hard time. Anti-queer prejudice is real. The legal and therefore social issues involved in the fight for marriage equality go far beyond being able to have a fabulous wedding.

Anti-queer prejudice in most parts of the US and UK is less than it was, certainly. But many of us over a certain age carry scars that influence our interaction with the world. I am smart. I love my work. I have a partner I trust with my life and heart. I have a home. I have a community (I have several interconnected communities). I have a vocation. I have friends and family. In most ways I am lucky. I have a magnificent life. And still, sometimes, every few years, I wonder how it might have been. I wonder how the world will change when we have marriage equality and its concomitant rights. A change in the law will lead to even faster and deeper change in the culture. It will make life easier, safer, richer (literally and metaphorically). It might help some of us let down the barriers, just a little. And then, oh, the world will need to get ready. There will be such a flowering of human art and joy and innovation…

For me and millions of others, tens of millions still to be born, this is not an academic exercise.

June 6, 2016

My Story, Mystery: A Letter to Hild of Whitby

Another is my never-ending quest to add previously-published essays to this site. This one first appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, September 10, 2015

Dear Hild,

You were magnificent, I think, but hidden: a black hole at the heart of history. We can trace you only by your gravitational pull. We know, for example, that the very first piece of English literature was forged in the fire of your influence; that in the so-called Dark Ages you built and ran Whitby Abbey, the foundation at the centre of what became Northumbria’s Golden Age. There you hosted and facilitated the meeting of kings, princes, and bishops that changed Britain, the Synod of Whitby. But we have no account of you beyond a five-page sketch in a 1300-year old history, most of which recites the standard hagiographic miracles and visions of the time. We have no gossipy Life, no scholarly monograph, no racy romance cycle. There isn’t even a grave.

¤

Whitby Abbey is now a ruin overlooking a harbour on the northeast coast of Yorkshire less than two hours’ drive from where I was born. It’s visible for miles, from land and sea. On a summer day, the cliff-top ruins are lovely, but northern summers are brief, and when the sun isn’t shining it’s impossible to ignore the winds that howl in off the North Sea. What prompted you to choose such an exposed spot? Vanity, asceticism, a craving for God’s presence? I doubt it. I think the sea itself was the point.

The poetry of your era is full of voyages; Anglo-Saxons were born sailors. For you, the sea was not a wilderness or a barrier but a road—one less treacherous than the broken remains of those built by Romans. Roman roads were a marvel: cutting through mountains, slicing across valleys, soaring over rivers. They were monumental, implacable. But not indestructible. When Roman military power withdrew, administrative structures failed. Without taxes, regular maintenance ceased. Trees grew, bridges fell, and ditches clogged. Marsh reclaimed great stretches; locals took beautifully-trimmed mile markers, bridge footings, and foundation pavers to shore up walls or use as post-foundations. As the once-unified province broke into warring tribes, parts of any traveller’s route ran through enemy territory.

It was quicker and easier to sail from Whitby to Bamburgh, the seat of Northumbrian royal power, than to ride. York and every other major Northumbrian centre was on a navigable river.

So the sea was the point; the sea and the harbour, one of the only havens on that stretch of coast, a place where a ship could pull in at night for travellers to rest, or to consult you. Travel was clearly one of your priorities: your ease of access to those in power—and theirs to you. Why? What made you so important? We don’t know. We don’t even know your full name.

¤

Anglo-Saxon names are generally dithematic, built of two elements, a prefix and suffix. According to the only document that attests to your existence, Bede’s Historia ecclesiastica gens Anglorum (HE), your mother was Breguswith, your father Hereric, and your sister—neatly—Hereswith. But you were just Hild, which means battle. Bede was writing fifty years after you died; I doubt you met him, or would have liked him if you had. He was a monk, one of the first generations of English oblates, with a very particular idea of women. Royal virgins were acceptable; wives and mothers of especially pious kings might rate a mention. Most of the time, though, Bede’s monarchs seemed to mate with the air. HE was the foundational text of English history, the model and exemplar of the genre for the next millennium and a half, and, in it, women barely exist.

You are an exception.

Even so, HE‘s scant mentions of you consist mainly of lists of the (male) bishops and (mostly male) saints you trained, and the (male) monarchs you advised. Bede writes that your father was murdered in exile, and while you were in the womb your mother dreamt you would be the light of the world and lead the way for Britain. He gives no clue how you might have managed this. I suspect, in fact, that Breguswith’s prophecy, which imbued you with a corona of singularity, was part of what made your achievements, your whole life, possible; it was the best protection a mother could give.

As the second daughter of an assassinated should-have-been king, you needed all the help you could get. You were probably homeless and hunted, almost certainly illiterate—everyone was—a child surviving among petty warlords. Bede says none of this, of course. In his text you are born (we don’t know where, exactly) and glide invisibly through the world until you appear at age 13 alongside the real subject of his narrative, your uncle the king (who may be the one who murdered your father; Bede is conspicuously silent on this point), with whom you were baptised in the first wave of Anglo-Saxon conversions. Then you vanish again for twenty years.

Twenty years. That’s a big chunk of anyone’s life. Who did you love, kill, nurture, bear, heal, persuade, or fight in that time? We’ll never know. But those twenty years must have been a crucible because the person who emerged was extraordinary.

You reappear at 33, recruited to the church by the founding Bishop of Lindisfarne, Aidan, an Irishman by way of Iona. Aidan went to some lengths to persuade you; he must have needed you. Bede, though, doesn’t see fit to tell us why—nor why you said yes. You joined the nascent Northumbrian church and founded Whitby Abbey, a double house—with women and men religious—which shortly became the jewel of the north. Archaeological finds indicate that Whitby was a hive of cultural production: goldsmithing, weaving, and, of course, books. Bede tells us you ran the place “with great energy,” that kings and princes “used to come and ask [your] advice in their difficulties and took it,” and that you were so revered all called you Mother.

Some time after Aidan’s death, you brought together the overking of Britain, his son, and the cream of the northern ecclesiastical elite for the famous Synod where the fate of the English church was decided. The overking spurned the so-called Celtic church (centred at Lindisfarne) in favour of aligning with Rome. Reading between the lines (not your lines, of course, and not in your language—there was no written Old English at that point) it was you who brought together the factions, forging an amalgam of the best of both, mitigating Pauline misogyny with Irish cultural egalitarianism.

That gift, the ability to bring together competing cultures, is what made the early creation of Old English literature possible. Religion and literacy, both previously the province of the elite, met and mated with the vernacular artistic tradition because you made it happen. You told Cædmon, a cowherd, to use his song-making gift in your service to spread the word of God. He did. His song, his poem, Cædmon’s Hymn, was written down in the vernacular, probably at your abbey, very likely at your instigation. You brought together different traditions, different ways of understanding the world, and made something new. In terms of English literature, at least, your mother’s prophecy came true: you lit the way.

You yourself remain in shadow.

¤

We tend to think of history as fact, but history is just moments that have come down to us, embroidered over the ages: stories. And women’s stories are missing. In a recent issue of the Paris Review, Hilary Mantel said, of revising a draft of A Place of Greater Safety a dozen years after she had written it, “When I read my draft, I saw that the women were wallpaper. There had been no material. Today you would think, Well, I must invent some, then. At the time I hadn’t seen the need—I hadn’t thought the women interesting.”

Of course we don’t seem interesting, because our interesting bits are missing. As Virginia Woolf said, “The history of England is the history of the male line, not of the female. For very little is known about women. Of our fathers we know always some fact, some distinction. They were soldiers or they were sailors; they filled that office or they made that law. But of our mothers, our grandmothers, our great-grandmothers, what remains? Nothing but a tradition. One was beautiful; one was red-haired; one was kissed by a Queen. We know nothing of them except their names and the dates of their marriages, and the number of children they bore.”

You are remembered as a woman so revered everyone called you Mother, but we don’t know if you had children of your own, the colour of your hair, or the names of anyone you kissed. We have two legends: that the ammonites that are found in such plenty at Whitby are the snakes you turned to stone, and seagulls dip their wings over the cliffs in your memory. The rest is a mystery.

¤

his story

history

my story

mystery

(adele adridge; NOTPOEMS, Black Maria, 1:1, 1972)

Stories help us empathise. Without them, we lose sight of who we can be. Elena Ferrante says, “I wouldn’t recognize myself without women’s struggles, women’s nonfiction, women’s literature—they made me an adult.”

Without stories of women with power and agency, women like you, we don’t see our shape and heft in the world or our own possibilities. We are poorer for it. We have no pictures of you, and no grave, but Whitby is built in your image and is your monument: elemental, unmistakable, arresting. It and you changed my life.

Yorkshire has been settled for thousands of years. Everywhere one turns there are the marks of human habitation: standing stones, Iron Age hillforts, Roman roads. The past is part of my landscape. I’ve danced katas in castles on mist-drenched mornings, day-dreamed of Neolithic raiding parties on the moors, and hummed songs a Roman auxiliary’s child might have learnt by Hadrian’s Wall. But Whitby Abbey is unique. There the skin of the earth feels thin, the boundary between past and present non-existent. Fossil plesiosaurs, like flying dragons that have crashed into the cliff in some alternate reality that might be running alongside our own, are freed from the rock every day by the tides; light shimmers over the sea like the first breath of the world; even the turf seems to tremble with immanence. To stand on the cliff at Whitby is to balance at the edge of reality. It was there that I understood the people from the past were real; at Whitby that I first wanted to know what it would be like to live in another time and place in another’s skin. It was at Whitby Abbey, with a hand on those fallen stones, that I knew I would become a writer.

You made Whitby. On some level, you made me.

Of all the women remembered by history—even sketchily—you’re the only one I know of who lived on her own terms. Your renown was not as anyone’s parent or wife, or for suffering unspeakable torment or a martyr’s death. All you achieved was as a person in your own right. You lived a long and successful life, and died admired and powerful. You won.

You won. That single fact, that women can win, helped counter-balance all the nonsense I’d absorbed from history. Partly because I stood in those ruins and saw what you had made, I knew we could each triumph on our own terms and in our own service.

In a very real sense, then, I owe you everything. But I didn’t want to write your story.

¤

History—his story—tells us that in the past, particularly so long ago, women lived narrow, caged lives: pawns of the marriage game; baby-making machines; handmaids of dynasty. The master story is that your constraints and those of your peers were terrible. But Bede tells us kings and princes travelled to you for advice—and took it. I could not see how you’d remained outside the master story.

The only way to find out how, to discover what made you who you were, was to write your story myself.

A paradox. To write a novel set in the Long Ago realistic enough, immersive enough, to persuade readers that this is how it was, this is who you were yet might appeal to those like me who have been taught to imagine women’s roles in the past as claustrophobic. It seemed impossible. Then I saw one faint and glimmering path.

If I could recreate the seventh century—a working world; its people, places, and web of political, religious, and personal relationships—I could then replay known events and watch what happened, see what shape a person with your achievements might take. But to feel confident that the you I imagined could have existed—for the experiment to be valid—I could not contravene what was known to be known, even in the smallest detail.

To even attempt such a thing was ridiculous. Intellectually, I knew this. But what keeps a writer going, what makes her able to think she will succeed where millions fail, is an almost psychotic self-belief. I’m guessing you had that too. However, to paraphrase Trollope, while the difficult can be done at once, the impossible takes a little longer.

It took me thirty years. For half that time, I didn’t even know I was working my way in to telling your story. My first novel, Ammonite (no, really, I didn’t know), was set in the far future, my second in the near future, my next three, about a character named for Aud the Deepminded, a ninth-century Norwegian, then Irish queen, who founded Iceland (I still didn’t know), set in the here and now. Some time after finishing the first Aud novel I started reading everything I could lay my hands on about the late sixth and early seventh century. Ethnography, archaeology, numismatics, jewellery, textiles, languages, food production, flora and fauna, weapons and warfare, medical approaches, religious belief—even the weather. I read a lot of poetry. Old English was foundational for me. I read several different translations of the extant poetry, then I read the originals (they come in a variety of recensions)—though I admit my understanding of the language is pitiful.

When I began to dream in the rhythms of heroic poetry, when I heard the shiver of new leaves in the wind and saw that shimmer of light over the sea, I was ready. And there you were, at the foot of an elm: three years old, wary, with a will of adamant. I fell for you, and I ached, because to get this right I could not flinch—there’s no story, no growth and change, without struggle. And your name, after all, means battle.

¤

When a novel is published these days it’s part of the author’s job to write publicity pieces to accompany the launch: lists, personal essays, travel-related features, anything which could plausibly relate to the work and might appeal to an editor or producer hungry for content. As Hild will be reprinted as a UK paperback in October, I recently pondered what I could write to support it. The first thing I set about was a list, a Five Best essay for a national daily in which one talks about five novels that have influenced the work at hand.

It seemed easy. Five titles dropped into my head immediately: powerful, immersive novels set in a time, like yours, when wind and animal muscle powered the world, and life could be brutal. Each was an old friend, read and reread for decades. Three by women and two by men; this proportion pleased me.

Then I realised that all, without exception, were about men. This disturbed me. These were the stories I loved, the historical fiction that had a powerful influence on my approach to writing; stories of war and leadership, personal and political change, and great deeds. Stories of lives history tells us matters. Men’s stories. I was appalled to see how the master story had influenced my own writing life.

I expanded the list of historical novels to ten, with the same result. It wasn’t until I increased that number to twenty—this time including books set in much more recent times—that women began to pop up. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that every single one of these historical novels about women were created by women who identify as lesbian.

¤

Did you love women, or men, or both (or neither)? We’ll never know, and I doubt it mattered. But we all like to see ourselves mirrored in the world, so I chose to make you bisexual (not a word you would have understood). The experience has brought—is still bringing—me vast joy. But, ah, I would give my big toe—perhaps even a foot—to have had your story, in your words, or the words of a female contemporary, to light the way.

Adrienne Rich said, “We must use what we have to invent what we desire.” What I desire is a world in which the you I have imagined could have existed, a world in which you lived your life with grace and agency.

History is our interpretation of what happened, our shared understanding of past events in the light of what we know today. I’m tired of the master story, his story. I’m tired of our story, my story being a mystery. Tired of women never making the hero’s journey, of women never leading their people just because they can, of never changing the world because they want to. I’m so very tired of reading about women who get where they do by marrying into power or giving birth to those who will inherit it, of women who are more object than subject.

By writing your story I am looking at where we come from—the past—and believing we could have survived there as ourselves. By imagining you as possible, I am recasting what today we think might have been possible. By reclaiming the past, retelling it to include women as people, I’m remaking the present, and, I hope, changing the future.

In my version of the world, you are no longer missing.

Cædmon’s Hymn, the earliest extant example of Old English vernacular poetry. For a discussion of what that means, exactly, a good place to begin is Double Agents, by Clare A. Lees and Gillian R. Overing (University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 2001).

These days the preferred terms is Early Medieval, though some might argue for Late Antiquity or the Anglo-Saxon age, depending on geographical location or area of interest.

Hild would have called it Streonæshalch. The current ruins are that of a Benedictine monastery founded in the late 11th century on the ruins of Hild’s foundation—maybe. There’s been a lot of coastal erosion; it’s possible that Streonæshalch—or what was left of it after the Vikings destroyed it in the 9th century—lies beneath the waves. (“Whitby” is a Viking name.)

Poetry written down long after Hild’s death, once an Old English literary tradition was well established. A tradition she may well have created.

There’s mention of Hild, too, in another document but it adds nothing. (But see Christine E. Fell, “Hild, Abbess of Streonæshalch” in Hagiography and Medieval Literature: A Symposium, ed. Hans Bekker-Nielsen, Peter Foote Jorgen Hojgaard Jorgensen and Tore Nyberg, Odense, Odense University Press, 1981, for discussion of a lost Life.) There are a variety of translations of Bede. These days it’s fashionable to interpret the title as The Ecclesiastical History of the English People. I first read it as A History of the English Church and People, translated by Leo Sherley-Price and revised by R.E. Latham (Penguin, London, 1968). All translations are from that revised and reprinted 1968 edition, unless otherwise specified.

There is some scholarly debate about what the rest might have been: Hildeswith? Hildeburh? (I like the latter: battle fortress.)

Roy M Liuzza interprets this line as “Her wisdom was so great that not only ordinary people, but even kings and princes sometimes asked for and received her advice.” (Broadview Anthology of British Literature, Vol. 1, Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press, 2006). But whichever translation you read, the gist is clear: Hild spoke, important people listened.

This makes Hild sound nurturing and kind. But you don’t get to be renowned enough to be remembered all over the world fourteen hundred years later by being sweetness and light. Mother Theresa might have helped millions but from what I can gather she was not a gentle soul.

Synod of Whitby, 664 CE. There are many chewy academic discussions of the event, but Wikipedia gives a reasonable overview.

Hilary Mantel, the Paris Review # 212, Spring 2015, p.49

Virginia Woolf, “Women and Fiction,” The Forum, March 1929

The genus of ammonite found at Whitby is Hildoceras bifrons. In fact the whole family of ammonites is known as the Hildoceratidae.

http://researchnews.osu.edu/archive/exptaking.htm

Elena Ferrante, Paris Review #212, 2015, p. 219

My first novel was titled Ammonite (Ballantine, New York, 1993). But it was set in the future.

The five books of the Long Ago are: The Crystal Cave, Mary Stewart (Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1970—about Merlin), Sword at Sunset, Rosemary Sutcliff (Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1963—Arthur), Fire From Heaven, Mary Renault (Pantheon, New York, 1969—Alexander), Master and Commander, Patrick O’Brian (Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1969—Jack Aubrey & Stephen Maturin), and The Great Captains, Henry Treece (Random House, New York, 1956—Arthur again). What is it about Arthur? We know even less of him than about Hild—I doubt he even existed. But we ‘know’ the name of his magician/teacher/prophet, his sword, dog, and boon companions. His story has become history.

So much so that I wrote a blog post about it, complete with brightly-coloured pie charts. Those charts appeared in media all over the world. A picture, they say, is worth a thousand words. Those pictures, those charts, were reproduced a thousand times. It’s a start, but only a start. A billion stories are missing.

For example, Stella Duffy, Jeanette Winterson, Emma Donoghue, Sarah Waters, Ellis Avery, Manda Scott…

Before the Christian conversion in the seventh century, there is no evidence that sexuality was a moral issue: no material culture, no text, nothing. For a detailed examination of the available information, see my research blog, Gemæcce. For more personal thoughts on Hild’s sexuality, see my personal blog

Adrienne Rich, What is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Politics (W.W. Norton, Boston, 1993)

First published in the Los Angeles Review of Books, September 10, 2015

June 3, 2016

Hild cat pictures and fan art

I’m hard at work on Menewood, aka Hild II. So here are a bunch of cat pictures, that is, cats with Hild, followed by some Hild fan art. Some of these you will have seen before, some are new.

First, pictures sent by readers of their cats (and one dog) reading (ignoring/sleeping on/about to destroy) the book.

Bliss (who supervises Jo Booms) reads to the fish

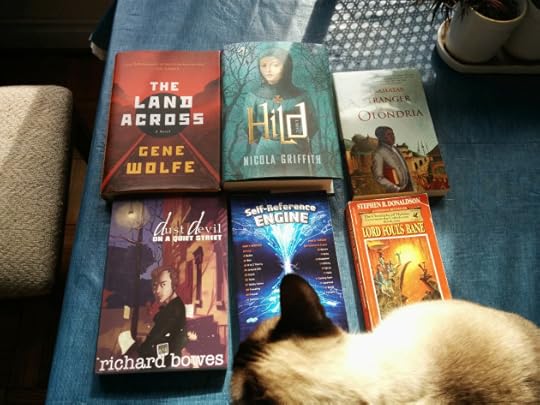

Cassie, who owns Brian Zottoli, ponders Hugo nominations

Stinkyboy the valiant (and greatly missed) guards Colleen

Fitz (who owns Traci Castleberry) can read upside down—and prefers library books

Ajax, who utterly dominates David J Williams, can also read upside down

Hilda (who advises Pastor Pilgrim) communes with an ARC

Kevin dreams of being a gesith.

Harvest Moon (who shares Jo Booms with Bliss and Joy) likes reading on the mantel

Joy, who owns Jo Booms (at least for now) reads her six-day old son, Wensleydale, to sleep…

…and Wensleydale gets big enough to learn to read

Petunia will fight you for a book

Talya the Russian Princess (who is served by Anne) has her way with Hild

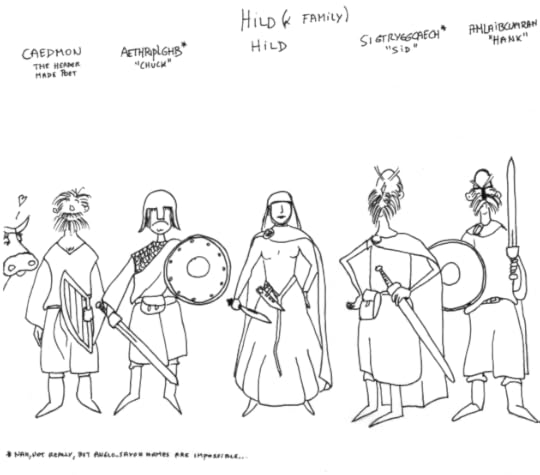

And now readers’ artistic imaginings of Hild and other characters. These first two are pictures of Hild by Justine. In the first, I imagine Hild’s just figuring out this staff thing.

And here she’s a bit older, a bit more at home with it. But clearly unhappy about something. Maybe she’s just seen what happened to the farming couple who hosted that family of bandits.

The second two are by Angelique, one drawn not long after a magnificent gift of wine while I was still writing Hild and neither of us knew where the story was heading or how much of Hild’s life I would cover. But we did know we’re both fans of Asterix the Gaul…

The second is after Angelique read the book and was complaining about some of the character names—and assigning different ones. (“Gwladus,” for example, became “Gladys.”)

Cian, by Felix Ortiz, stands tall, very tall (not to mention broad).

And finally here’s a pic based on Hild, by Carolyn Raship, who is selling the painting on Etsy—with more than a quarter of the sale price going to Planned Parenthood. So go buy it.

If you have pictures you want to share do send them. I’ll turn this post into a page so people can find it anytime.

May 31, 2016

The Women You Didn’t See: A Letter to Alice Sheldon

Another in my never-ending quest to post my previously-published essays to this site. “The Women You Didn’t See” first appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books, July 2015, and Letters to Tiptree, ed Alexandra Pierce and Alisa Krasnostein, August 2015.

Dear Alice,

You were brilliant, I think, but consumed by the inevitability of the abattoir. In your fiction all the gates are closed; characters are funnelled down a chute to flashing knives. In your best fiction, the characters know what is happening but the knowledge makes no difference; there’s no way out.

You didn’t believe in the possibility of escape. Assuming the persona of James Tiptree, Jr. meant at least you could step outside the chute and be the one wielding the knife. Raccoona Sheldon, on the other hand, bound you—and us—inside the doomed and running cows; then you sometimes tantalised your victims with a vision of a better reality before tearing it to shreds before our eyes (“Your Faces, O My Sisters! Your Faces Filled of Light!” ), and sometimes you focused unwaveringly on the stark machinery of death (“The Screwfly Solution” ). But for you there was no way out.

¤

When you were little, you saw filth, death, deprivation, and suffering in India and Africa. So too, of course, did many of the hundreds of millions who lived there. Unlike many you were not, as far as I know, physically brutalised. But you were alone: a pretty, pampered, privileged little girl plunged unprepared into violent contradiction—then exposed by your writer mother just before puberty to the hot breath of public scrutiny. You had no herd protection, no people just like you, nowhere to turn for comfort or take shelter. Did it warp you in the chrysalis? Or were you exactly as you were born to be?

We’ll never know. It doesn’t matter. But this, if I had to guess, is why you hid all your life. This is why you picked up professions and dropped them as soon as you got good, and why, when you found writing as an adult, you took pseudonyms: the best way to stay safe was to not be known. You could rotate a facet of yourself before a curtain with a single slit. No one ever got to see the whole, not even you.

We never met in person. I didn’t smell your skin or feel the vibration of your voice. I can’t call up a memory of how you moved or the way you responded to particular sounds. But I heard your written voice: I read your fiction. Now that you’re beyond hurt, I admit: I did not admire your novels or your later short fiction. For this reader, you produced your best work when you were behind the curtain.

¤

One of the things we don’t know about that person who hid is whether choosing to write as a man meant you also wanted to be, or felt as though you were, a man.

You wrote a letter in response to Joanna Russ in which you said, “I am a Lesbian.” If this is true, you identified as a woman who loved women—or tried—rather than as a man in the wrong body. Weighed against this is the youthful (I think, and, according to your biographer, probably drunken) cri de coeur scribbled in a sketch pad. “[I long to] ram myself into a crazy soft woman and come, come, spend, come, make her pregnant Jesus to be a man…I love women I will never be happy.…” Given the (possible) youth and (probable) drinking this might be the melodrama of immaturity. It could be a test, an exploration of the kind teenagers indulge in, donning and doffing identities and attitudes to see what suits the emerging self. You emerged many times, of course, most spectacularly in middle age. I suspect that if wanting to be a man was a thing of the body rather than the spirit, if you wanted physically to have been born a man—as opposed to yearning to be treated with the respect usually reserved to men—being among women would not have made you feel free or proud. But that’s exactly how you felt when you joined the Women’s Army Corps: “the first time I ever felt free enough to be proud.”

We don’t know, we can’t know. So I will take you at your word: you were a lesbian, a woman who loved women.

¤

There are two words—both with the same root in covert, the past participle of covrir, Old French for to cover—that I suspect you understood in your bones: covert and coverture. I have no doubt that as part of the CIA you were deeply and consciously familiar with the denotation, connotations and consequence of the former. The latter is a legal doctrine, probably introduced to English common law by the Normans, by which a wife’s legal identity is covered and subsumed by her husband’s. As Wikipedia puts it, in a marriage there is only one person, and that person is the husband. Some aspects of coverture survived into the second half of the twentieth century—more than fifty years after you were born.

This doctrine influenced the relative status, behaviour, and regard (including self-regard) of women and men. Men were real people, judged as such. Women were not. And it’s my belief that “James Tiptree, Jr.,” three words, gave you cover, a way to be free in the world without risking a particular scrutiny. A man, even a clearly pseudonymous one, is judged as a person and not for the myriad ways she is a not-quite-person. Given your experience, you believed Tiptree could be a writer. Alice Sheldon could only have been a female not-quite-person who wrote.

It’s likely, then, that you became Tiptree because as a man you could write what you think and how you feel, be respected and liked. You deserved to live in a place of respect, a place we all deserve, a place we all belong: recognised as real people without having constantly to fight to be a human being.

So why did you—ex-CIA—let slip a vital piece of information about the death of your mother? Did you want, on some level, to be revealed? Or did grief fuck with your head? Grief does that; it can make you crazy.

Whatever the reason, you were grieving far more than your mother when your first novel came out under the Tiptree byline but was understood to be written by Alice Sheldon. You were mourning the cover and camouflage that kept you secret, kept you safe. You had lost the hidden place that felt like home. Once again, you were exposed to the world.

¤

I’m a woman. A dyke. Foreign (even in the UK, where now I’m often thought to be Canadian). A cripple. In today’s parlance I suffer a lot of intersectional micro-aggression: the constant, mostly unintentional but damaging nonetheless, insult of unthinking words and attitudes scraping along my hull below the waterline. Most of us in oppressed groups tend to seek out our own kind as a matter of survival; people like us offer us a mirror, a place to belong and be understood. Shelter from the cold.

I’m the only expat lesbian cripple I know. It gets lonely.

Being out my whole life—even when I was four I knew I would not marry a man; actually falling in love with a woman when I was 15 was just a detail—meant I had nowhere to hide. Queer was the only minority I knew without grants, government departments or liaisons, laws, schools, or families of origin who understood how hard it is, and whose mission was your encouragement and support. I felt isolated, alone. I’ve no doubt you did, too. Many of us do.

So I understand why you might not have wanted to be out in the early twentieth century. Being out was hard. It cost a lot.

¤

Of your major works, “The Women Men Don’t See” is singular. The two women our traveller meets don’t know what they’re heading towards, exactly, whether they are jumping from the frying pan into the fire. They know only that they are burning and must get out.

Two things about this story interest me particularly. First, we are left with hope for the women. It’s only a sliver, true, and sharp with irony, but it’s there. Second, neither of the women has—as far as we know—suffered physical violence. They are damaged, yes—as are all of us who, day in and day out, navigate cold and hostile waters, scraped and battered and weighed down by that ice—but not broken, not essentially breached. They will live. They are making a choice.

It’s a forced choice, but a choice. We are shown some of their circumstances but not all; we have to make assumptions. We can’t know for sure whether what they’re doing is a good idea. Similarly, we can never know a writer’s reasons. We can make assumptions—about why, say, for one woman gender-neutral initials will be enough to provide cover to write; why another keeps an obviously female name but clears her path by hosing everything with rage; why yet a third takes a male name—but we can never know. They all grow in different microclimates, under different gravities.

Living under a higher gravity than those around us levies a weight penalty: we have to use more energy, more strength, more attention to run the same distance and hurdle the same obstacles.

¤

I listened the other day to a panel of women talk about diversity in fiction. They talked about how difficult it was to grow up as immigrants to another culture, how they were pressured by family to succeed in a profession—engineering, medicine, law—rather than art. I resonated with some of their experience but in another way I could not. I could not imagine growing up in a world where my family and wider society assumed I was capable of a profession, where I would be welcome in a profession, where I could survive in a profession.

I can’t know anyone’s struggles. I do know that they and you and I laboured under different burdens; our eras, places, classes, and cultures were different. But for the women on that panel access to a profession was a given. We may as well have been born on different planets.

¤

Today, women and quiltbag folk still live under a greater gravity than others but that is changing every day. Hopefully, by the time others read this the gravity will have dropped a notch: same-sex marriage with be the law of the land. I’ve written elsewhere about how, in my opinion, this will change gender equality on a fundamental level. It will take time, of course; it always does. But what I’m getting at is that already, today, there are women growing up who will not labour under any weight penalty.

Girls losing their milk teeth today will become women who won’t have the faintest idea what coverture means unless they become historians. These women will be able to put their strength, attention and brilliance into forging new paths, making new connections, dreaming of new possibilities rather than carrying extra weight or keeping themselves safe.

These are the women you didn’t see. They will own the world.

“Your Faces, O My Sisters! Your Faces Filled of Light!” Raccoona Sheldon, Aurora: Beyond Equality (Fawcett, New York, 1976)

“The Screwfly Solution,” Raccoona Sheldon, Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact, June 1977

This direct quote from Sheldon, and others below, are from James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon, by Julie Phillips (St. Martin’s, New York, 2006).

https://www.sfsite.com/fsf/2006/eh0610.htm (accessed 4/30/2015)

http://jamestiptreejr.com/asawriter.htm (accessed 4/30/2015)

“… in the rain, under the flag, the sound of the band, far-off, close, then away again; the immortal fanny of our guide, leading on the right, moved and moving to the music—the flag again—first time I ever felt free enough to be proud of it; the band, our band, playing reveille that morning, with me on KP since 0430 hours, coming to the mess-hall porch to see it pass in the cold streets, under that flaming middle-western dawn; KP itself, and the conviction that one is going to die; the wild ducks flying over that day going to PT after a fifteen-mile drill, and me so moved I saluted them…” http://jamestiptreejr.com/army.htm (accessed 4/30/2015)

This makes me glad—though every now and again my gladness is bittersweet. This is something anyone from any traditionally downtrodden minority understands: the new generation has no clue how hard it was. We are happy for that. Mostly.

“Wife,” June 23, 2014, https://nicolagriffith.com/2014/06/23/wife/ (accessed 4/30/2015)

First published the Los Angeles Review of Books, July 9, 2015, and Letters to Tiptree, ed Alexandra Pierce and Alisa Krasnostein (Twelfth Planet Press, Perth, Australia, 2015)

May 23, 2016

Do not message me on Facebook

I post to Facebook, and I respond to comments on those posts, but that’s it. I don’t read others’ timelines, I don’t use Facebook Messenger, and I don’t interact with Facebook Groups. The only Facebook Events I take note of are those in which I’m scheduled to participate. If you post about the death of your dog on Facebook, I won’t see it. If you send me a Facebook message, I’ll miss it. If you insult me on Facebook, I won’t read it.

The takeaway? If you want me to know something, email me. If you don’t have my email address, use this site’s contact form and I’ll write back—then you will have it.

Facebook is a broad and public communication tool; I use it the same way I use Twitter (and Instagram, and LinkedIn). I do read all blog comments—and respond to many—but, again, that’s a very public forum. To communicate one-on-one, email is better. With email, I can tag and categorise and file in exactly the way that works for me: I don’t lose track of requests and conversations.

So, once again, if you want to talk to me about anything, use email.

May 18, 2016

Disability Art, Scholarship, and Activism

Me and Riva (left) talking about making her portrait of me. Photos by Jennifer Durham.

On Friday May 13 I gave a presentation at the University of Washington’s Pacific & Western Disability Symposium. The theme of this year’s symposium was making disability public in art, scholarship, and activism, so that was how I focused my talk. I spoke for 35 minutes (about half was taken by 2 readings), and then artist Riva Lehrer spoke for 40 minutes about her work as a portraitist. We both then talked about the process of making her portrait of me, from our different perspectives as subject and artist, and then we did audience Q&A.

The event was captured by a CART stenographer but we only have a rough, unedited version. I’ll talk to Riva about her whether or not she’s okay with me posting what she said, but for now here’s the main part of my own segment.

I write for three reasons. I write because I love it; I write to find out; and I write to change the world—which is what I’ll be focusing on today.

Adrienne Rich said, “We must use what we have to invent what we desire.” What I desire is a world where those of us who are traditionally Othered—women, people of colour, poor people, old people, crips and queers—live lives of grace and agency. I want the world—and the visual and literary representations of that world—to behave as though we’re real people, not signifiers or metaphorical props: human beings in, of, by and for ourselves.

I grew up in the north of England where it was dangerous to be an out dyke—and I was always out. I was 4 when I declared I’d never marry a boy and over the last 50 years I’ve seen no reason to hide. To me it seemed so obvious it might as well have been tattooed on my forehead: my name is Nicola, I’m a girl, I fancy other girls.

It all seemed perfectly obvious and perfectly natural. Most of the world, of course, didn’t think that way.

When I was 21 I lived in a depressed and depressing city on what you might call, ah, the fringes of society. It was a hostile, physically dangerous place.1 And I was in a band: very visible. So a group of women formed a collective to learn self-defence. Once I’d learnt, I started to teach my community, for free. Then I discovered, to my unutterable delight, that I could get paid by institutions like the Equal Opportunities Unit, the Union of Catholic Mothers, and the Girl Scouts of America.2

Anyway, as a result—of being an out dyke and being paid to think about danger—I lived in the red zone a lot. In other words, I was not one of those writers who knew from age 5 I wanted to be an author. I didn’t go to college to study creative writing—when I was living in Hull I didn’t even know such a thing as an MFA existed.

It’s not a great leap from writing story songs to writing stories, and once I started writing fiction I found it addictive. It was at this point (I was 24 or 25) that I founded something called the Northern Dykes Writing Workshop.3 But didn’t think about formally studying writing til I was 27 when I applied to a 6-week residential workshop called Clarion here in the US. But even as I applied to Clarion I was so ambivalent about the idea of formally studying writing that I also applied to a 4-week women’s martial arts camp in the Netherlands. I didn’t know what I really wanted so I applied for both and thought I’d leave it in the hands of fate: Whichever accepted me first would win. (It never occurred to me I might not be accepted…)

Clarion said yes first—and gave me a partial scholarship, so writing it was.

Clarion has a reputation as a 6-week writing bootcamp that changes your life. I had no clue about that reputation; I knew nothing about it; I just saw an ad in the back of a magazine and thought: Hey, that sounds interesting…

But it did change my life. Clarion is where I met Kelley. Clarion is where I began the slow journey to thinking of myself as a writer.

As a writer it turns out that my primary joys are pretty much the same as those out in the real world. I’m very much a creature of the body.

I could talk for hours about what that means but instead let me read you something from my fifth novel, Always, the third in a triptych of novels about a woman called Aud Torvingen, a 6-foot tall Norwegian American.

[I read from Always. You can listen to me read a version here]

As living beings we are our bodies; it’s impossible to separate the physical self from the mental or emotional: the mind/body binary—Cartesian dualism—is rubbish. We experience the world, we learn it, through our bodies.

As a writer, I bring the reader into my fictional world through the characters’ physical, embodied, experience. What a character feels, what they notice of their world—and how they feel about it—tells the reader a vast amount.

Imagine an upscale Italian restaurant: polished marble (or stone composite) floor, open kitchen with chefs chopping things, one of those central fire pits with the hammered copper hood. Now imagine you’re a woman walking in with two small children. The first thing you’ll see are those sharp knives and open flames: dangerous for your kids. (Then, maybe, you’ll look at the menu and think, Huh, no fish sticks; they aren’t going to like this place…) But what if you’re someone who’s just been beaten in a hate crime? It’s probably that you’ll immediately focus on men with big hands or loud voices, or who have drunk too much and so seem unpredictable, or are wearing something—a particular colour of shirt of type of boot—that triggers memories of your assailants. But if you’re running for your life all those issues take second place. You dart in off the street and what you’re looking for is a hiding place, or another exit.

As a northern dyke teaching women’s self-defence if I’d gone somewhere like that restaurant (if I’d been able to afford it) the first thing I’d have done when I walked in is do a visual sweep for exits, defensible positions, and anything I could use as a weapon. And I’d pay attention to the people who represented potential danger. But that was then. This is now. I’ve changed. I’m no longer a women’s self-defence teacher living in the red zone. Now I’m a married, tax-paying, post-menopausal, disabled citizen of Seattle; for me the world is no longer immediately physically dangerous.

Now when I enter that Italian restaurant (assuming I can get in, that it’s accessible) I don’t look for exits and weapons; my focus has changed. If it’s raining will my crutches slip on that shiny floor? Are the chairs okay for my back? Can I get into the bathroom?

As people what we notice of the world depends on who we are. As readers, what we learn of a fictional world depends largely on the character experiencing that world. To show you what I mean, I’m going to read the beginning of most recent novel, Hild, which is set in north of Britain 1400 years ago

[I read from Hild. You can watch me read a version here.]

All my fiction opens with place. I funnel and filter the environment through the emotional lens of my protagonist. The 7th century was so different from our word, the 21st century, that I thought the best way to help a reader understand it was to encounter it the way a child might and learn alongside her.

There’s a lot of evidence from cognitive science to show that we as readers take the experience—the emotion, the thoughts, the struggles—of well-drawn characters as our own: books are empathy machines.

But writers aren’t machines, we’re people. We are not separate from our work; we imbue our work with our own experience and perspective. I don’t care what most artists say, I think you can know us through our work (you just don’t know what bits you’re knowing). I bet, for example, that you could read one of Kelley’s books and one of my books, and within two minutes of meeting us you’d know who had written what.

Writing, then, is a weird mix of public and private. We write in private, we read in private, but the work itself is shared publicly: not only is the book available all over the world, and across the years, but criticism of the work is published in mass media, and the book is discussed in the academy, in book groups, and in casual conversation.

Books reflect who the writers are and where they are, physically and emotionally, when we conceive them. Mostly.

Late last year, two years after Hild was published, I finally read it. And I discovered an odd thing: there’s not a single crip in that book; not one. There are queer women, and men, there are people with different levels of power and access, people with different skin colours and different languages. But not one character with a disability. What’s that about?

I’ve been thinking about that. I was born a woman—female experience is embedded in my life and work. As far as I’m concerned I was also born a dyke—just about all my protagonists are queer. And I spent many years before and after starting to write being poor—it’s not surprising there’s lots of class awareness in my work. In other words, a whole matched set of Otherings—being a woman, queer, poor—came naturally to me. But being a crip didn’t. It’s taken me a while to wrap my head around it.

I was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1993 but didn’t try to write fiction about it until 6 years later. That attempt was a novella, “Season of Change,” about a woman who, when she’s diagnosed with MS, thinks her life is over. It’s speculative fiction, so the metaphor is made external and concrete: MS becomes a literal monster who haunts/hunts the protagonist. It ends with protagonist’s epiphany: she can accept MS because she realises she’s different, not dead, and instantly feels better. I sold the novella for what was then, to me, a lot of money.

Publishing operates on geological time not human time—its pace is glacial—so there was a long pause between selling the novella and the intended publication date. I had lots of time to think about it. And the more I thought about it the more uneasy I got. The whole thing just felt…wrong, though I couldn’t quite put my finger on why. But that wrong feeling got worse and worse and eventually I pulled the novella—voided my contract—stuck it in a drawer and tried to forget it.

Fast forward eight years, to the third Aud novel, Always, in which Aud meets and falls in love with Kick—whom you met. Kick’s a stuntwoman, fantastically fit—there I was typing away, halfway through the book, when I realised Kick was about to be diagnosed with MS. I’d known she was sick but planned for the diagnosis to be something else and realised I was just kidding myself: she had MS. It was hard to write, but I did it, and I’m proud of the book—but as soon as Always was published I found I didn’t want to write anymore Aud novels.

I told myself it was a publishing issue4 but I suspect I just didn’t want MS in my fiction as well as my life. It made me feel too vulnerable, too exposed.

Then about three months ago I read an interview with two writers who work in disability studies who used the phrase narrative prosthesis. This is a term originally developed by David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder to describe literary or visual narratives that use disabled people as a metaphorical opportunity. Mitchell & Snyder tell us that traditional narrative arcs are built to restore the status quo. So crips in fiction are either fixed, by which I mean:

– we’re cured

– our ‘problem’ is overcome—and it is entirely our problem: nothing to do with the miseries inflicted by the built environment or ableist culture

– or we have an epiphany so everything’s magically okay now

or eliminated. (Not unlike early queer narratives…5)

I read that and thought, Ah, shit: I realised what was wrong with “Season of Change:” the crippled protagonist has an epiphany in which she ‘accepts’ MS and thereby her MS is magically no longer a problem for her. I was ignoring the fact that being disabled is a problem not because of our impairment but because the world has a problem with our impairment. I was using MS as a narrative prosthesis.

This is the kind of beginner’s mistake I never made about women or queers or class even when I was a beginner. So it’s clear that when it comes to disability the writing me learns slowly.

But the writing me is finally ready.

I’m rewriting “Season of Change” and retitling it “Small Dog Theory.” Also, the novel I’m writing now, Menewood, the second book about Hild, has a variety of disfigured and disabled characters.

Now I have an expanded toolbox, tools I will wield with intent. And my intent, as I said at the beginning, is to change the world.

My aim as a writer is to persuade readers to recreate the characters’ experience inside themselves and, by so doing, invite then to consider those they’ve thought of as Other (people of colour; women; the queer, disabled, and poor) as real human beings like themselves. I’m norming the Other.

In art as in life crips don’t exist to be objects of others’ pity—or amusement, or tolerance. We are not here to teach or inspire anyone. We’re not signifiers or metaphorical props. We are people: human beings in, of, by, and—importantly—for ourselves

With my writing then, by re-imagining what was possible for us in the past, what’s possible today, and what could be possible in the future, I’m recasting what might have been, reinterpreting what actually is, and reshaping what will be possible.

I am inventing what I desire: a world where we are real people at the centre of our own lives.

1 I’ve written about the violence and other consequences of growing up queer.

2 Kelley and I once taught a memorable date-rape class in Georgia for a horde (it could have been as few as 35—but it felt like a horde) of tweens and teens and their mothers.

3 The Northern Dykes Writing Workshop was a periapetetic event held every few months in a different northern city such as Hull, Bradford, and Manchester.

4 There are three Aud novels. Each was published by a different publisher and given utterly different covers and flap copy and marketing focus: a recipe for disaster. I’m tryin to get the rights reverted so they can be published properly but it will take time.

5 And is still happening. I’ve lost count of the number of lesbians who are killed off on broadcast and cable TV (though Autostraddle hasn’t).

May 5, 2016

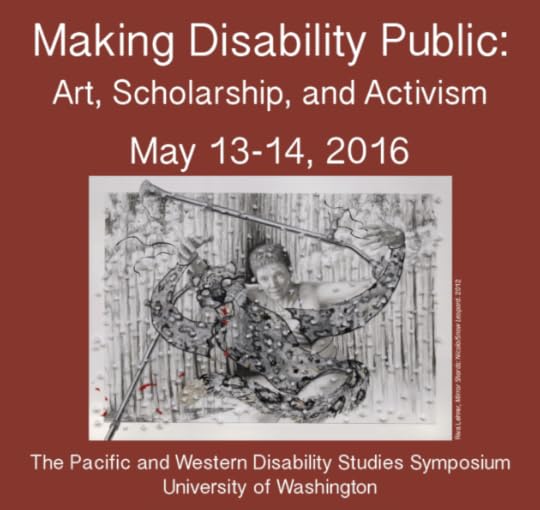

Making Disability Public, Friday May 13

I’ll be doing an event at the University of Washington, Seattle, with artist Riva Lehrer. It’s the headline event for the Pacific and Western Disability Studies Symposium 2016: Making Disability Public: Arts, Scholarship, and Activism. It’s free and open to the public.

This is a kind of coming-out for me: my first appearance where I not only talk about and read from my work but discuss how my MS and disability have had an impact on that work. It’s absolutely fitting that I’m appearing with Riva, whose portrait of me was one of the catalysts of coming out as a crip. Riva and I are friends, so expect the unexpected.

Anything I read will be based on the body and its delights with full-sensory physicality. Something from Hild, maybe. Or a brand-new bit of Menewood. Or The Blue Place. Not sure yet. I might also read from a not-yet-finished novella, “Small Dog Theory.” So, hey, it’s going to get…interesting.

Here’s the official description of my event:

Friday, May 13, 4:30-7:00pm“Disability Arts & Culture: An Evening with Riva Lehrer & Nicola Griffith”

University of Washington, Seattle, Odegaard Library (ODE), Room 220

4:30-5:00 Poster and Art Display

5:00-7:00 Presentations by Nicola Griffith and Riva LehrerWe’re honored to host a reading & discussion with Nicola Griffith, whose novels include Ammonite, Slow River, and Hild. Griffith will talk for the first time about disability in her work, and participate in Q & A with Riva Lehrer about the making of her portrait “Nicola Griffith / Snow Leopard” that’s featured on the advertising for this event.

We welcome Chicago-based artist Riva Lehrer, an award-winning painter, writer, and speaker whose work explores issues of identity and cultural depictions of disability. Her visual art and writing have been featured in several documentary films and publications. Among her best-known projects is “Circle Stories,” a series of portraits of disabled people with careers in the arts, academia, and activism. Lehrer writes about her latest project, “The Risk Pictures”: “For twenty years, I have been using the language of portraiture to explore what it means to live in a stigmatized body. My portrait collaborators have often been made to feel ashamed of their physical selves, as a result of being targeted by judgmental, aggressive gazes leveled in their direction. Reasons for stigma might be due to disability, sexuality, gender affiliation or racial identity; all can lead to difficulty in living in one’s actual body.”

Attendees on Friday will also be invited to the poster session of student disability studies research, art, and social justice engagement.

Sponsored by the Disability Studies Program, ASUW Student Disability Commission, and other UW units

Map: Odegaard Library. Time: 4:30 – 7:00 pm. Free! Facebook Event. (FYI, I’m assured that if you have difficulty with registration via FB not to worry: come on down anyway, there’ll be room.)

April 28, 2016

Aud tweetchat

I’ve used Storify to collect all the questions asked and answers given for the tweetchat I just did with Rocky Mountain College’s ENG 120 class all about Aud.

ETA: Originally I embedded the chat. Here’s what my edit screen looks like

But when I publish, it all turns to hell. No idea what the problem is. Any experts out there who know what this is and can fix it?

April 25, 2016

Coming out as a cripple

Today I’m coming out as a cripple. I’m not talking about acknowledgement of physical impairment but about claiming identity as a crip.

In some ways this decision follows the same pattern as calling myself dyke (at age 19, many years after I understood I liked girls, several years after I started having sex) and naming myself a writer (years after I started selling fiction). There is a world of difference between being physically impaired and claiming crip. When I say I’m claiming crip it means it’s time for me to talk about disability as a political and relational issue. (Disabled is a relative term; its meaning is not fixed. Cultural ideals of normalcy vary from place to place, time to time, and culture to culture.) For me disability is not a medical problem. My impairment is not the problem. Cultural attitudes and built environments are the problem.

In 1993 I was diagnosed with MS; I’ve never hidden its physical effects.1 I’ve been publicly using a cane, then double crutches, for nearly 20 years; last time I was Guest of Honour at a convention I used a power chair; the bio on my latest novel is clear about the fact that I have MS. I have also regarded my MS and its consequences as a tedious, time-consuming thing Over There, separate from my real life. My illness, I reasoned, was a personal difficulty that took a lot of bandwidth to mitigate; why give it any more attention than necessary?

I came to think of this stance as the Small Dog Theory of illness: keep the irritating, yappy little hairball fed and watered and it won’t annoy you as much.

The Small Dog Theory is a load of rubbish.

As I become less physically able—as I start using a wheelchair sometimes, as I prepare to buy a car with the express purpose of converting it to hand controls—I find that my cripness is assuming greater heft. Being a cripple is taking up more and more space. It does not and cannot exist separately from my life. Every time I want to go out for coffee, or a beer, or dinner, every time I’m asked to speak somewhere I’m faced with attitudinal and environmental obstacles. I have to spend an inordinate amount of time and energy asking questions and explaining.

I begin, of course, with whether or not the venue provides step-free access. Oh, yes, I’m generally assured. So then I have to make sure that the hosts or organisers understand what that means. Most know enough to work out that if there’s a flight of steps up to the entrance, the venue is not accessible. (Though you’d be surprised at how many think two or three steps is the same as zero steps.) Many people don’t think beyond that. I’ve lost count, for example, of the number of bookshops that have no bathroom on the main floor—and no elevator. Yet the managers still call their store accessible. You want me to speak at your conference from a stage or raised platform? Great. How do I get up there? And when I get there will there be an adjustable-height microphone and a chair (because I can’t stand for an hour)? Will there also be a small table (because if I’m not standing I can’t use the podium)? How far away is parking? How far is it from the entrance to the table/stage/counter? Importantly, are there automatic doors?

Frankly, doors are the bane of my life. In most restaurants, bars, and hotels, for example, public bathrooms have massive, spring-loaded slabs for outer doors. (Why? To keep muscular germs away from the unsuspecting public?) These doors are physically impossible to open while using double crutches or a wheelchair. They are also hard for small children and those accompanied by small children; they’re difficult for the elderly, for those with painful joints, anyone in a cast… (The list is almost endless.)

Take a moment. Imagine how it feels to be an adult and have to ask help to get in and out of the fucking bathroom.

Inaccessible bathrooms are not a problem I should have to solve; they are a problem of the built environment, of urban planning, of economics, and of political awareness and will.2 I’m tired of that. So today I’m making a conscious choice to begin to talk about political issues relating to disability.

Would I rather not be a cripple? Yes. I’d love to run again. I’d love to go for a walk. I’d love to even be able to carry my own pint from the bar to the table or plate from the buffet. I’d love to just show up at a bookshop in the carefree knowledge that I can access everything I need. I’d love to be able to get in and out of any cab, car, train, plane, or boat without constantly checking on its specs or whether the driver knows to drop me/pick me up right outside the entrance. None of that will happen; there is no cure for MS. But there is a cure for ableism.

The world has to change. We all need to start helping the world to change—to learn to think about access issues and attitudes. Because it’s unjust for those with the least access to political power to always be the ones to think about it. And, as studies have shown, it’s allies who make diversity happen, not those who are discriminated against.

I’ll give you one example of what needs to change: the Washington State Democratic Caucus. This is my first presidential election as a US citizen. I wanted to find out how to make my voice heard despite the fact that I couldn’t attend in person. It was not easy. I had to email the local party three times before I got a response on how to do it. Most voters probably wouldn’t bother.

Caucuses attract those who are:

Able-bodied (mobility, sight, hearing—how many ASL interpreters do you suppose they had standing/sitting by just in case?)

Time-rich (those with the leisure to spend several hours of a precious Saturday afternoon in non life-maintenance tasks, like rich people, or students—how many minimum wage earners, how many single mothers, how many carers of the sick and elderly can get there?)

Socially at ease (how many agoraphobics, or those on the autism spectrum, or with social anxieties?)

Politically educated (I’ve talked to a few people who didn’t even know what a caucus was, or how to find out where to go)

Etc. (This list, too, is almost endless…)

Is this the epitome of democracy? No. There are too many barriers to entry. Voting should be easy, as close to friction-free as humanly possible. For that reason caucuses, in my opinion, should be discontinued in favour of primaries using postal ballots.

As I say, that’s just one example of the kind of thing that’s now on my radar. I’ll be exploring further what it means to be disabled in this culture. I may explore in person, on this blog, in essays, or in my fiction. I’m not sure yet.

To mark the occasion of claiming crip, on Friday May 13th I’m doing an event with artist Riva Lehrer3 at the Pacific & Western Disability Studies Symposium, at the University of Washington, Seattle. This year’s Symposium is subtitled Making Disability Public: Art, Scholarship, and Activism. It seems apt.

I’ll talk more about that event in a week or two. For now, save the date.

1 I’ve talked on this blog about the etiology of MS; I have a page on this website dedicated to what I need if you want me to come to your convention/bookshop/school. I’ve found that no matter how superficially appealing hiding the truth can seem, it ends up a waste of everyone’s time and energy. And it’s damaging. I learnt that by the time I could decide anything for myself. Perhaps one day I’ll write another post—it will be long—about all the different coming outs of my life so far. But today is not that day.

2 Don’t even get me started on gendered bathrooms. Idiotic, discriminatory, and occasionally quite literally deadly.

3 Riva created MIRROR SHARDS: NICOLA/SNOW LEOPARD, a portrait of me. Here’s a post about the process—though that’s not the whole story. I’ll be talking about it at the symposium.