Nicola Griffith's Blog, page 64

November 20, 2016

Short fiction bibliography

A few days ago on Facebook I promised I would put up a list of my short fiction. Then yesterday on Twitter I mentioned I’d written a couple of Warhammer* stories back in the day. Everyone seemed surprised. True, I don’t write much short fiction (I have a lot more nonfiction) but even so it seemed like a good idea to remind readers that, yep, there is some out there.

I have a total of 16 stories. Information listed includes date of first publication, length, and brief description including genre.

All, with the exception of “Libby Thomas” and “Princess Fat Grits,” have been reprinted, most many times, and may be available free online in both text and audio. Go look. Three are collected in With Her Body. (There is no other collection.) Quite a few are available in other languages. If you’re interested, there’s also a wonderful short video, “Sun on Dragonfly” based on my reading of “Touching Fire.”

Enjoy.

• “Cold Wind” (2014). Tor.com

3,500-word shape-changing dark fantasy set in contemporary Seattle.

• “Acid Rain” (2009). New Scientist

Very short piece of hynagogic writing (fantasy? SF? prophecy?)

• “It Takes Two” (2009). Eclipse 3, ed. Jonathan Strahan, San Francisco: Nightshade

12,000-word SF novelette about the biochemical nature of desire and its role in love.

• “A Troll Story” (2000). Ghost Writing, ed. Roger Weingarten, Montpelier: Invisible Cities

7,000-word fantasy set in 9th-century Norway, based on a Norwegian folk tale.

• “Libby Thomas’s Chemistry Set” (2000). Realms of Fantasy

Under 2,000-word story that’s maybe fantasy, or magic realism, or wish fulfillment.

• “Princess Fat Grits” (2000). Realms of Fantasy

2,500-word fairytale/cautionary tale about the perils of mocking a determined princess.

• “Spawn of Satan” (1999). Nature

1,200-word science fiction about consequences of older motherhood and egg donation.

• “Yaguara” (1994). Little Deaths ed. Ellen Datlow, London: Orion

18,000-word fantasy novella set in the lush jungle-covered Mayan ruins of Belize.

• “Touching Fire” (1993). Interzone

10,000-word science fiction about love, lust, music and what it means to be an artist.

• “Song of Bullfrogs, Cry of Geese” (1991). Aboriginal

7,000-word science fiction in which illness triggers a gentle apocalypse.

• “Wearing My Skin” (1991). Interzone

7.500-word dark fantasy about sisters separated at birth.

• “We Have Met the Alien” (1990). Iron Women ed. Kit Fitzgerald, North Shields: Iron Press

1,500-word fantasy (science fiction? meditation?) about an adolescent discovering she is Other.

• “Down the Path of the Sun” (1990). Interzone

4,500-word post-apocalyptic science fiction about the nature of grief.

• “The Voyage South” (1990). Red Thirst ed. David Pringle, London: GW Books

19,000-word novella set in the Warhammer Fantasy role-playing world, with love, lust, drugs, magic, and sea battles.

• “The Other”(1989). Ignorant Armies ed. David Pringle, London: GW Books

7,000-word fantasy set in the Warhammer Fantasy role-playing world, with love, lust, fear, and politics.

• “Mirrors and Burnstone” (1998). Interzone

8,000-word science fiction that, at the time, I had no idea was the prequel to Ammonite.

* Yes, they all feature queer women. Yes, even then. (I think I might have been the only woman in the anthologies. Certainly the only one writing under her own name.) They were commissioned by David Pringle who published them as is, though he did relay others’ comments to the effect that, “Judging by Nicola Griffith’s stories Warhammer is a matriarchy!” (It was a warning, I think: Write about boys! I did not listen.) There’s another Warhammer novella, “Blood and Earth,” that was never published—I did get paid, but the publishing programme ran into a problem—and a fourth, “Snakesteel,” that I outlined.

I had the best time writing those stories. So much so that in 2006 or 2007 I outlined a big sword-swangin’ fantasy novel based on my characters and plots. I got permission from Games Workshop to publish—if I de-Warhammered them; essentially filed off the serial numbers—but at the last minute started Hild instead. I still think about that novel sometimes. Swords, ponies, sex, angst, magic, war, betrayal, love…

November 9, 2016

Ashes

Trump won. A man with the internal psychology of a not-very-smart not-very-secure bully has just been elected the leader of the free world. Many people will suffer, especially those like me whose income is precarious and whose social position—woman, queer, crippled, immigrant—has just become even more so. The safety net is in ashes.

Russia will be happy. The right wings of many European parties will be happy. Selfish rich people will be happy. Those who resent the rule of law will be happy. Weapons makers will be happy. Those who voted for Trump—mostly straight white people—will be happy, for a little while. But when taxes for rich people go down and poor people up, when tens of millions of us lose our health insurance, when abortion is illegal and sexual assault laughed at, when facts are dismissed and it’s even harder for many of us to vote, when health, safety, financial, environmental, workplace (and more) regulations are weakened or discarded altogether, when people of differences races, religions, sexualities and religions are harassed in the streets, at work, and on social media, they may stop being so happy. For once, I won’t care: Trump voters will deserve every ounce of it. (ETA: That was anger, fear, and lack of sleep talking. Schadenfreude is not usually my style. Us vs Them politics isn’t, either. My gloves are off, in the sense that I’m more than willing to point and speak out, speak against untruths, semi-truths, and downright lies, point to selfishness and greed and small-mindedness, but I’d rather not actively wish ill to many people.)

But most of those who will suffer will not deserve it. And we will have to stick together. We need each other, more even than we needed each other during the Great Recession. So let’s take a few days, feel what we need to feel, take stock, check in with family and friends, and then next week get to work. I’ve no idea what form that work might assume. I’ve no idea how effective it will be or how long it will take. But as far as I can see there’s no choice but to do it.

So for the next few days do what will help you and let’s reconvene next week. Will a phoenix rise from the ashes? I don’t know. We’ll find out. Meanwhile, keep yourselves safe. We will need each other.

October 29, 2016

Ellen Key Harris-Braun

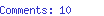

This morning I found out from a friend that my first US editor, Ellen Key Harris-Braun, has died. I will miss her. Ellen was the first book publishing professional I worked with in this country; her generosity, willingness to colour outside the lines, and overall kind smarts helped form my expectations of the US science fiction publishing community.

Ellen bought Ammonite for Del Rey in 1991. Del Rey did not have the reputation as a liberal or experimental press at that time so I was a bit surprised at the offer: both the fact that Del Rey wanted this sex-romp-on-girlie-planet, or radical-reexamination-of-gender, or biological-What-If (all terms used about the book) and the fact that the advance was a bit more than usual for a first-time effort.

Then, as now, the success of first novels from genre presses live or die on the buzz, internal and external, generated before publication. Without Ellen, Ammonite, like so many other deserving books, would have withered on the vine.

I’d been working as a critic/reviewer for Southern Voice, the Atlanta queer newspaper, and the books that got media attention were hardcovers with beautiful covers that came with blurbs from other writers, a glowing letter of praise from its editor, and announced plans for advertising, author appearances, and interviews. So I asked Ellen what I could expect. And she said, Well, er, nothing. It would be a mass-market edition, with tiny type on nasty paper with a generic sfnal cover. There would be no publicist (no publicity), no appearances, nothing. Del Rey were operating on the throw-spaghetti at the wall and see what sticks model as so many imprints were at the time. They made calculations about the general hunger of the genre readership and just pumped out stuff and hoped the profits averaged out.

But this was my first novel and I wasn’t in the mood to bow my head to How Things Are Done, so I said to Ellen: if I come up with a plan, will you help? She said yes.

So Kelley and I went out for dinner, drank an inordinate amount of wine, and came up with some kick-arse ideas. First and foremost: a marketing blurb. I can’t remember if it was me or Kelley who came up with the actual phrase but Change or die… became the organising principle of our joint effort. I asked some writers I admire—who didn’t know me from Eve—like Ursula Le Guin and Vonda McIntyre if they would read the manuscript with a view to a blurb. When they said yes, I asked Ellen to photocopy and mail it to them. (It’s amazing to think that this was all happening before you could just send a file attached to email. Before most people had email, actually.) Then I got on the phone with two of my Clarion instructors, Tim Powers and Stan Robinson, and asked them if they were willing, too. (I didn’t have a number for Chip Delany, and never heard back from Kate Wilhelm and Damon Knight.) Once again, Ellen stayed late at work illicitly photocopying and mailing using company resources.

Very generous blurbs came back pretty fast. Then I set out to create an official-looking publicity sheet. This was before Photoshop: I cut and pasted the Del Rey logo onto a blank page and got Kelley to photocopy it a few times using the corporate resources of her employer until we had what looked like letterhead. Then I wrote a spiffy marketing blurb following what I’d learnt from two years reading this stuff for others’ books as a reviewer. Then I put together a list of feminist bookstores and specialty SFF bookstores and sent it, and a zillion copies of the fake publicity sheet to Ellen.

Del Rey would not be creating ARCs, bound proofs, or even photocopied manuscripts. There was no way Ellen could illicitly photocopy, bind, and mail the whole novel to dozens of book shops so between us we decided on the 20 most important, and chose the first four chapters. Ellen stayed after work for a few days, photocopying and mailing, and into each packet she put the fake publicity sheet plus a personal letter.

Meanwhile, we put our heads together to come up with a cover concept. Bruce Jensen came up with a lovely sketch that showed Grenchstom’s Planet, GP, or Jeep, with cloud cover looking like an ammonite (at least I think that’s how it looked; it was 25 years ago, and I don’t have a copy to refer to). Ellen showed it around internally and most people at Del Rey approved it. I was excited: this going to be a good-looking book! And then one day the president of Ballantine, Linda Grey, walked through theh Del Rey offices, caught sight of the sketch, and said, “What the hell is that?” Ellen started to explain but Linda Grey gave her a look and said, “Del Rey’s an SF imprint; put a spaceship on the cover.” So that’s what happened. Ammonite, my precious first novel about self- and other-wordly exploration acquired a lurid orange and yellow illustration, complete with jelly-bean spaceship (which I admit I actually kind of liked but that seriously did not represent the book at all). We managed to get a sort-of ammonite shape overlaid on the planet but that’s about it.

Meanwhile, the simultaneous publication of Ammonite in the UK (acquired by Malcolm Edwards and with much more support behind it) steamed ahead. The UK version had a much better cover, based largely on a sketch I’d drawn; I was very happy with it. But for a while none of us would know anything. Ellen acquired other novels. I wrote Slow River. And we waited.

I can’t remember when I first knew things were beginning to go really well. Perhaps it was the excited phone call from Ellen telling me I was about to have a brilliant review in The New York Times Book Review (I have no data for this but suspect it might have been the first mass-market genre novel to get glowing praise from the NYTBR), and the Los Angeles Times and the Washington Post Book World. Maybe it was the notification that Ammonite was short listed for a Lambda Literary Award even before it was officially published (and went on to win; and I finally met Linda Grey who referred to me as “our award winner”). But it was clear to me that thanks to the hard work, smarts, and generosity of Ellen Key Harris-Braun I was on my way. I don’t know of any other editor who would have helped me in this way, or who made such a difference in my career. Ellen was the first of many—and I mean dozens—in publishing who have helped me. But she set the tone for me; she was the one who showed me how important it is to help each other. I will always be grateful.

Thank you, Ellen. I will miss you.

October 24, 2016

Living Fiction, Storybook Lives

Another entry in previously-published essays. This one was first published in the Harrington Lesbian Fiction Quarterly, Vol. 1, issue 1 (Binghamton: Harrington Park Press, 2000). It has been reprinted a few times, most recently in Narrative Power: Encounters, Celebrations, Struggles, ed. L. Timmel Duchamp (Seattle: Aqueduct Press, 2010).

There isn’t a culture on this earth without some kind of storytelling tradition, whether it takes the form of a wrinkled elder in some dusty village spinning tales of gods and demons, a sleek publishing industry churning out romances and thrillers, or a Hollywood production company filming teen splatter pics and syndicated genre series. As individuals and societies we are shaped by story: our culture and sense of self literally cannot exist without it because we only know who and what we are when we can tell a story about ourselves. We learn how to tell our story by listening to the tales that are out there and picking through them, choosing some details and discarding others. If something happens to us that doesn’t match the plot lines and characters we are familiar with, we don’t know how to classify it or describe it, we don’t know where or even whether it fits. It does not become part of our story. As Henry James once remarked, adventures happen only to those who know how to tell them.

Imagine you’re a young boy being raised in a large Christian fundamentalist family. You grow up thinking that everyone in the world believes in a particularly vengeful, unforgiving god—you might believe in that god yourself simply because you don’t know it’s possible to not believe. If one day you pick up and read The Sparrow, a novel by Mary Doria Russell in which a priest who loves the world and loves god is abused beyond endurance and loses his faith, it will change your life. Now imagine how it would be if you are a young girl living in that same household, told every day that women are lesser beings and weaker vessels, that the only purpose in your life is to marry and have children. You’re invited to a friend’s house and she turns on the TV. On comes Xena: Warrior Princess, and for the first time you see a woman who is faster, stronger, and smarter than anyone in her world, a woman who always wins and always gets what she wants. Your world is shaken to its foundations. When you go back home, you have secret dreams of resistance; for the first time, you understand the concept.

Stories give us role models and offer us tastes of other possibilities; even seemingly inconsequential experiences matter. Let me use myself as an example. I was raised in a very traditional English household where, thirty years ago, exotic food items such as pasta, rice—even mushrooms or peppers—simply did not appear on the menu. I ate some variation of meat, potatoes, and two veg every day of my life. If I ate lamb, it was roasted; potatoes were mashed or baked; beets appeared only in salad (which to the English of that time meant lettuce, sliced boiled egg, spring onion, sliced tomato, sliced beets, and salad cream). As soon as I left home I fell on the foods of other cultures like a starving wolf. I’ll never forget the first time I ate in a Spanish restaurant: lamb (cubed and marinated in lime juice, garlic, mint, and rosemary), served with patatas bravas, beets, and black beans. The same basic ingredients I had tasted before—meat, potatoes, beets—but so very different. I went home and the next day tried to make something like it for dinner. I didn’t use a recipe—I didn’t have to; it was enough to know that such a taste was possible. I kept trying, experimenting, because I knew it had been done before, and although I didn’t get it exactly right, I ended up with something quite individual, something I liked better. My very own recipe.

People do this all the time with new stories, and the truth or fictionality of the story doesn’t much matter; what counts is the story itself.

At the end of my second novel, Slow River, there is an Author’s Note which reads, in part, “There is a disturbing tendency among readers…to assume that any woman who writes about abuse…must be speaking from her own experience… Should anyone be tempted to assume otherwise, let me be explicit: Slow River is fiction, not autobiography. I made it up.” Like most fiction, this is a lie, but true.

Although most of the things that happen to Lore in Slow River never happened to me, I have felt most of the things she feels. To some extent, all good fiction is emotionally autobiographical. It’s impossible to describe a particular emotion well unless you’ve experienced it: a man who has never been in love or woman who has never been hungry won’t be able, respectively, to describe characters who love or hunger. This doesn’t necessarily mean, for example, that you have to be scared of spiders to write about a character who is arachnophobic, only that you have to have experienced fear itself. The adrenalin surge of fear—shaking muscles, dry mouth, and racing heart—is universal, so once a writer has experienced it, it’s relatively easy to transpose it to another key. All the primary, basic-drive feelings—lust, anger, hunger—are universal; it’s the circumstances under which we feel those emotions, and how we then choose to act in those circumstances, that are the subject of fiction.

But I’m being disingenuous because, of course, Slow River bears a much closer relation to my life than just the emotions I ascribe to its various characters. To understand why I thought such an Author’s Note necessary, or even relevant, you need to understand why I write, or at least part of why I do so.

One thing I have learnt about myself is that I enjoy forming theories. Give me a bunch of facts that appear related, and I’ll do my best to come up with a theory to explain it all. It’s a game I play: always trying to figure out how the world—people, plants, political systems—works. My favourite theories are the ones in which several other theories interconnect. One of the ways in which I use fiction is as a test ground for these theories.

The theories I test, revise, and test again most often are the ones about myself, the ones that try to answer the question, “Why and how did I become who I am?” (The fact that “who I am” is not a constant doesn’t make this any easier, but it does provide endless material.) An inevitable corollary of this question is, “Why and how did other people become who they are?” Slow River is largely concerned with a question that nagged at me for a long, long time: How come I spent many years living a rather squalid existence (no job, no prospects of making money legally, few scruples), yet managed to find my way out, to the quite staid and respectable life I have now, when others in the same situation never escaped? In the course of writing the book, I found that the answer to my question was that the question itself was not valid: people are never in the same situation. They might appear to be, but the similarities are superficial. In the novel, for example, although Lore and Spanner seemed to be in the same boat—no money, no family, no official existence, no resources but their bodies and their wits and the ability to use both without conscience—their situations were utterly different. Lore had been born to privilege. Her sense of self, her experience, both practical and cultural, her view of the world as a generally tameable place was at odds with Spanner’s. Lore could hope and Spanner could not. In the same way, you and I might appear to be in the same situation but we would have come to it from two vastly different places, via different paths, and bringing with us different internal resources. Our emotional and practical responses to the circumstances would be, like us, unique. When I understood this, my understanding of my whole past and all the other people in it changed; many of the value judgments fell away: I wasn’t better than others, or worse—just different. The story of Slow River mattered as much to me, the writer, as to any reader.

One of the things I enjoy about this kind of hypothesis testing is that it’s not me going through all that trauma. In fiction I get to turn up the heat and watch my guinea pigs run through the fire. More heat makes them scurry faster and brings things to a conclusion more quickly than in real life, and it’s more interesting for the reader. So although the city in Slow River is based on the city I lived in for more than 10 years, although I, too, moved from a comfortable background to pennilessness overnight, my family was never mega-rich, they never abused me (physically, emotionally, or sexually), I have never been kidnapped nor scammed the media, I’ve never lived under a false identity, and I haven’t any particularly esoteric knowledge regarding the running of any industrial processes. But the feeling, the emotional process, that Lore experiences living by her body and her wits resembles my own.

Many writers do this. This is probably why so many readers think they know an author after reading their story or novel. However, it is a grievous error for a reader to assume anything about a writer based solely upon that writer’s fiction. For one thing, you can never tell which bits are “true” and which bits are “fiction”; for another, to assume that some particular part of the fiction is autobiographical is to belittle the writer’s imagination. (See Joanna Russ’s How to Suppress Women’s Writing, an excellent book, for more on this.) For example, when the reader thinks, “Gee, here’s this white dyke who lived in the UK writing about a white dyke who is living in the UK and who was abused by her mother; therefore, the author must also have been abused by her mother,” s/he is saying the writer couldn’t imagine her character being any different from herself. Such readers don’t know logic from a hole in the ground. Funny how they never assume that because my character is fabulously rich (or stunningly good-looking, or quite deadly with her hands) I must be too. There again, being rich and good-looking and able to defend oneself are Good Things, and the farther a person seems to be from the cultural norm (and in this time and place the default is still set at Straight and White and Male), the less likely other members of that culture will be to ascribe positive traits to that person. One of the stories our culture constantly tells itself is that Different equals Bad, or at least Less.

◻︎

Every society has its own set of master stories, or cultural clichés: men are stronger, the infidel is less than human, the rich are more important. A storyteller, whether a novelist, singer or screenwriter, should be aware of these. Every time a cliché is uttered, it becomes stronger; the master narrative is reinforced. Don’t misunderstand me, I am not saying that a writer’s job is to change the world, that all fiction should be radical, positive, motivating, and so forth; I write, as I’ve already said, for myself. Nor am I saying that writers are responsible for what a reader does with the dreams and images we create with our fiction. I’m saying only that we should be conscious of the fact that our work affects others.

I receive countless emails from readers who tell me my work has changed their lives. One woman, married and the mother of two, emailed me from another country and said that, after reading my first novel, she was finally able to understand some of her feelings: she was a lesbian. After reading my second, she had the courage to do something about it. One man told me at a signing that reading about Lore’s struggles in Slow River had helped keep him sane during a terrible period in his career. Another woman in Atlanta told me that after reading Ammonite she’d left her solid, corporate job to pursue a dream of being an oral storyteller.

It’s partly because I know how deeply fiction can influence the lives of readers that I dislike stories that reinforce the status quo, that reiterate the old, master patterns of our culture (particularly those dealing with issues of power and prejudice). Some of these narratives reinforce consciously, some unconsciously; I prefer the former. Unconscious reinforcement is the result of bad writing, usually a combination of clichéd phrasing, laziness, and lack of imagination. With conscious reinforcement, I know the writer has done his or her job, and will most probably have made an attempt to explain in the text why a character believes in the status quo, which at least indicates to the reader that another way is possible.

One recent trend in science fiction (and fantasy) that is an ugly but effective reinforcer of the status quo is what I call Sex & Servitude SF. There are two main types. The first is fiction in which the main character is or becomes a slave or bonded servant who falls in love with her (and I use the pronoun deliberately) owner. The reinforcing message here is usually that (a) love conquers all, (b) anything is better than being alone, and, sometimes, (c) some of us are just born lesser beings and need someone to tell us what to do. The second type dwells lovingly on physical torture, often sexual, in which the torturer is usually (though not always) male and the victim usually (though not always) female. A more subtle variation of this second type is one in which some kind of sexual threat or constraint is present but covert. The message here, of course, is that women are victims: we have been, are, and always will be.

Not all fiction with these tropes reinforces the status quo. Generally speaking, the better the writer, the less likely they are to fall into all the old trap of stereotyping (though there are stunning exceptions). Cliché is the great reinforcer. Examine it—the person, the situation, the culture—with a clear eye and strong prose, and the cliché melts, because the reader sees individuals in particular situations. We understand that this happened to them for particular reasons; that a different choice or different circumstance would have led to a different outcome. In other words, exposing the cliché, writing it out, renders it powerless because we see alternatives.

One of the most depressing stories I have ever read is Joanna Russ’s “When it Changed,” a novella that demolished stereotypes with one hand while reinforcing them with the other. Whileaway is a planet where, nine hundred years ago, Earth colonists landed and a virus killed all the men. In the story’s narrative present Whileaway is a world of thirty million women and girls. Russ gives us a gleaming vision of women as autonomous, whole human beings—human in and of themselves, not in relation to men; her characters marry and have children, they love and hate, are smart and stupid, tall and short. Women, she tells us, can do and be anything they want. And then, with the return of men from Earth, and the way the inhabitants of Whileaway respond, Russ smashes the glorious vision to pieces. She says, in effect: Men can come and take away women’s autonomy and humanity whenever they want. By refusing the imaginative leap—of showing the reader how eight or nine hundred years of freedom from prejudice would alter a woman’s psychological response to a man, alter feelings of relative self-worth and self-esteem—she reinforces the cultural stereotype, which runs: “Women only have what they have because men allow it; men are bigger and stronger and therefore will have their own way in the end.” All it takes is two sentences from the narrator, Janet, speaking on the day the men arrive on Whileaway:

He went on, low and urbane, not mocking me, I think, but with the self-confidence of someone who has always had money and strength to spare, who doesn’t know what it is to be second-class or provincial. Which is very odd, because the day before, I would have said that was an exact description of me. (1984, 17)

It is, indeed, very odd. In the context of Russ’s setup, Janet’s attitude makes no sense to me. She has never felt herself to be second class in her life, why does she start now? If anything, she should feel utterly superior to these beings: they don’t speak her language properly, they don’t understand how the Whileawayans have children, and they look like “apes with human faces.” They are bigger, yes, but I don’t imagine for a minute that if Janet met a bigger woman she would respond this way. It is only someone who has grown up in a sexist society who would be programmed for such feelings of inferiority.

When I first came across “When it Changed” I was about nineteen and re-discovering science fiction at roughly the same time that I was discovering feminism. They were my new toys, bright and shiny and exciting. “When it Changed” left me feeling bewildered, crushed, and angry. It seemed to be telling me there was no point to anything I was trying to do. These days, being a more sophisticated reader, and knowing Russ’s work, I suspect that Russ used cliché deliberately to shock readers like me awake, to say: It doesn’t matter how much women change themselves; unless the men change, too, there’s no point to any of this. But I’m not sure, and, frankly, those two sentences are still an unexplored (in the text, which is what we’re talking about) cliché; they therefore reinforce, by simple repetition, the master story with all its stereotypes.

One of science fiction’s traditions is that in the future many prejudices will magically disappear; I’m used to reading fiction where racism and sexism and homophobia barely exist. Last year I read a debut novel that broke this tradition. The novel is set in a very near future seemingly extrapolated in an uncomplicated fashion from the present world (there are a few, slight differences). The protagonist is a smart, good-looking, strong woman with a fair amount of professional expertise and general life experience. So far so good. Then as I read I realized the author was breaking the usual sf tradition of diminishing prejudice. At first, I assumed that the author had broken the tradition deliberately and with forethought to make some kind of point; I kept waiting for that point, or at least an explanation. When none was forthcoming, I realized that she had simply ignored the tradition and substituted instead an unexamined cliché: that men will always be more politically powerful than women and will abuse that power, sexually and otherwise. Given the changes in sexual politics in the workplace (in Europe and North America, at least) just within the last two decades, simple extrapolation would have led to a corporate climate of the near future being even more favorable towards women than at the present—yet the main character allows herself to be sexually intimidated and used by a series of men in the work place, for no reason that I could see. It made no sense. This kind of sexual harassment has been illegal in the US for years, and any smart, strong, savvy woman who experiences it has recourse to various professional and legal responses. If a fictional character (sf or otherwise) chooses to suffer silently, we need to know why, what the special circumstances might be, in either her character, or her situation. The author of this novel, though, gives us no special or particular circumstances; her premise seems to be that women have always had to have to put up with that kind of thing, therefore they always will. She reinforces the master story. It irritated me; I felt as though someone had tracked filth through my nice clean, optimistic little genre, which made me sit down and try to figure out why—which is why I have written this essay. So I suppose even bad stories bulging with cliché have their place in expanding our lives.

◻︎

If we want to expand our choices we need new stories—new tastes—to entice us from the old and familiar. Coming up with these stories is not always easy. Not only is struggling with the master narratives and trying to visualize new concepts, worlds, or ways of being, quite difficult, those of us who do so are often sneered at and accused of escapism. For example, some readers complain that the only sex in Slow River is lesbian. “It’s not like that in the real world!” they cry, to which I respond, “So what? And why does this bother you so much?” Sometimes I paraphrase Tolkien: those most likely to be upset by the notion of escape are the jailers.

Stories are important, precious, necessary. They are the tools with which we break free, with which we hack out new paths to untrodden places. Stories are not frivolous. Virginia Woolf’s novel, Orlando, has been criticized for being fanciful, for ignoring the constraints of gender, not dealing with the harsh facts of life. In Arguing With the Past, Gillian Beer states that Woolf moves her fiction away from the arena of real life facts and crises because she denies the claims of such ordering to be all inclusive. In other words, just because the master stories tell us that something is as it is does not mean that this is all there is, or that more (or difference) is not possible. We need only to climb onto the back of a new story and take that imaginative flight into the unknown. If when we get there we like what we see, we can choose to incorporate it into our vision of ourselves. It will become real, part of the story of our life.

Works cited:

Arguing with the Past, Gillian Beer (London, Routledge, 1989)

Ammonite, Nicola Griffith (New York: Del Rey, 1993)

Slow River, Nicola Griffith (New York: Ballantine, 1995)

How to Suppress Women’s Writing, Joanna Russ (London: Women’s Press, 1984)

“When It Changed,” The Zanzibar Cat, Joanna Russ (New York: Baen, 1984)

The Sparrow, Mary Doria Russell (New York: Villard, 1996)

Orlando, Virginia Woolf (London: Hogarth Press, 1928)

October 13, 2016

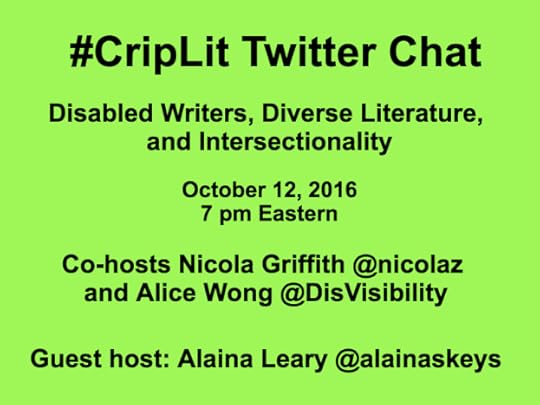

Disabled Writers, Diverse Literature, and Intersectionalism

Yesterday was the third #CripLit chat, this time about being disabled, a writer, and intersectional identities. It was a bit slower than usual (because Wednesday?) but still busy, with good, thoughtful, and thought-provoking conversation about, for example, internalised ableisim and #OwnVoices. It certainly helped me to a couple of realisations.

Alice Wong (@SFDirewolf) has put together the Storify of the Disabled Writers, Diverse Literature & Intersectionality chat. If you’re not a fan of Storify, then just visit the hashtag on Twitter. And do read the first two chats, Disabled Writers and Disabled Characters, and Disabled Writers, Ableism, & the Publishing Industry.

We encourage people to keep the conversation going, to continue to use the #CripLit hashtag to talk about disabled writers and disability literature of all kinds.

October 10, 2016

Trump is a monster

Donald J Trump on Friday boasted of being a sexual predator. Many Republicans are abandoning ship.

We know that Donald J. Trump, the Republican nominee for President of the United States of America, is a vile excrescence on the face of the earth. We have known for a very long time. This year alone we have watched as he:

claimed Mexicans are rapists

mocked a disabled reporter

is accused of not paying contractors

sneered at a prisoner of war for being captured

hired Roger Ailes, fired for sexual harrassment, as his debate advisor

insulted the parents of an officer who died for his country

probably did not pay federal taxes for the last 18 years

faces at least one lawsuit alleging attempted rape

accused 5 men cleared of rape charges via DNA evidence of being guilty anyway

boasted on tape to being a sexual predator

So I roll my eyes at the most recent breast-beating anguish of Republicans. They knew what they were getting when they voted this monster in as their standard-bearer. Why these sudden professions of outrage? Perhaps the voters and political operatives who elected him as the Republican nominee were genuinely ignorant but I doubt it. If they are ignorant they are wilfully so. They have been telling themselves fairytales.

In my opinion, those who voted for Trump are motivated by cynicism, anger, and/or fear.

Let’s take cynicism first. Trump is losing. His debate performances have been awful. On Sunday evening according to FiveThirtyEight the odds of Hillary Clinton winning are now 81.9%. The RNC are worried they’re going to lose their congressional majority, that animus against Trump will seep down-ticket and put even supposedly safe Republican seats at risk. So they are using this latest revelation as an excuse to publicly ditch him and see what they can salvage. Disavowing Trump is a strategic move; it is not motivated by surprise.

The angry people are those who were top of the pile—lots of straight white men who used to earn good money doing the kind of job that has been going away for a while (overseas or to automation or simply disappearing from the world) plus some of their wives who rely on their pension income. They want their stuff back, especially their status. They want to climb back on top of the pile; they want to be part of the majority again. It’s their god-given right. These are the kind of people who voted for Brexit: they want to take their marbles home and not let anyone else play. They are the Greatest Generation, dammit; they’re used to being in charge.

The frightened—ah, now this is the constituency that interests me the most. Over the years a lot of evidence has accumulated about the supposed correlation between a voter’s response to fear and their political leanings. As the Atlantic point outs:

“The common basis for all the various components of the conservative attitude syndrome is a generalized susceptibility to experiencing threat or anxiety in the face of uncertainty,” the British psychologist G.D. Wilson wrote in his 1973 book, The Psychology of Conservatism. In other words, an innate fear of uncertainty tends to correlate to people’s level of conservatism.

The world is changing fast: for those who grew up in a whiter, slower, more homogeneous world uncertainty is accelerating. They want a strong man, someone who can allay their fears, reassure them that now he is charge everything will be all right. They want their Daddy.

This partisan divide goes deep. According to the Wall Street Journal

Republicans and Democrats divide on policy positions, and the ideological divisions can extend to taste in music, movies and books. An analysis of what people who “like” the presidential candidates on Facebook “like” elsewhere shows interesting ways the partisan divide can go beyond the issues.

They show nifty maps of people’s tastes in music matched to their voting preference: if you like Adele, you’re most likely going to vote Democratic; Ted Nugent, Republican all the way.

And the partisan divide is getting harder, the barriers higher. This is particularly noticeable at the sharp end, in Congress, where, according to PLOS One, “partisanship or non-cooperation in the U.S. Congress has been increasing exponentially for over 60 years with no sign of abating or reversing.” And it started happening long before the confirmation bias enabled by social media. Look at their spiffy visualisation:

But let’s set all that aside and look at what Trump, today’s face of the Republican party, said about his attitude to women.

I moved on her actually. You know she was down on Palm Beach. I moved on her and I failed. I’ll admit it. I did try and fuck her. She was married. […] I moved on her like a bitch, but I couldn’t get there. And she was married. Then all of a sudden I see her, she’s now got the big phony tits and everything. […] You know I’m automatically attracted to beautiful— I just start kissing them. It’s like a magnet. I just kiss. I don’t even wait. And when you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything. […] Grab them by the pussy. You can do anything. (From full transcript at the Los Angeles Times.)

He “doesn’t wait.” He just starts kissing them. He believes that “when you’re a star, they let you.” He thinks of course that he is a star, and so can get away with anything. “Grab them by the pussy. You can do anything.” He is boasting of sexual assault. This man wants to be leader of the free world, arguably the most powerful person on the planet. What do you think he would do with that power?

Right now, the companies he leads—the people he has hired, who look to him for example—are facing more than 20 lawsuits over the harassment and mistreatment of women. Imagine what this country might look like after a year of his leadership. Intellectually, morally, and temperamentally Donald Trump is unfit to be President of the United States.

If you haven’t already registered to vote, please do so as soon as possible. Please do vote. And please vote for Hillary Clinton. I really don’t want to have to move…

October 8, 2016

Brexit-related death and decline: a rant

The day after the UK voted to leave the European Union I posted my opinion to the effect that many people would die as a direct result. I have not changed my mind. In fact, after the events of this week, I’m more certain than ever.

On Sunday, Theresa May declared a so-called ‘hard’ or ‘clean’ Brexit. In March 2017 she will trigger Article 50 setting the formal divorce in motion; she insists that the UK will take control of its own borders. That is, once the two-year divorce negotiations are concluded there will be no free movement of people. Many in the EU have already made it clear that free movement of people across borders is a condition of membership of the European Economic Area (EEA)—the single market.

EU Commissioner Juncker suggested that the EU should respond with intransigence. This sentiment was echoed by Francois Hollande and Angela Merkel. The Europeans will play hardball. Unless the UK allows free movement of people they will not be admitted to the EEA; they will not be part of the single market. Many tariffs and trade barriers will be reintroduced. This will have severe consequences.

Let’s begin with the cessation of passporting. Passporting, the ability to sell services across borders into markets where a company—a bank, say—has no branch, is a major factor in London’s status as a (perhaps the) centre of the global finance market. According to the Wall Street Journal, without passporting banks and other businesses face “extreme disruption.” Britain is the fifth largest national economy in the world as measured by GDP. It’s the fastest growing of the G7 countries and has been for 4 years in a row. Given that about 12% of that economy (not to mention 2.2 million jobs) is based on financial services, loss of passporting will have major consequences. It’s very likely that many global banks will decamp from London and set up shop in Amsterdam (where passporting will continue). A few might operate from Dublin (ditto) but Dublin, while a lovely city, does not have the energetic hum that attracts high-fliers.

Unemployment will rise. Tax receipts will fall. The government will have more people to help with less money.[1] Add the imposition of a whole slew of trade tariffs for goods as well as services, and you start to see the beginnings of a problem whose proportions might eventually reach crisis.

Markets last week began to notice. On Friday the British Pound fell off a cliff, plunging to 1.18 USD before recovering—a bit—to 1.24 USD. For a sense of what that means, since the paperback of Hild came out in the UK before Brexit my royalties have dropped 25%. I’m lucky, I get relatively little of my income from the UK. I am not going to suffer that much. The people who are going to suffer deeply are a) immigrants b) UK residents and/or citizens, especially the poor.

Let’s look at residents and/or citizens of the UK first. Take food as one example. According to a report in the Guardian earlier this year, the UK sources more than 50% of its food from abroad. Quartz suggests 27% of all food consumed in the UK comes from the EU. So the first piece of the picture is to immediately crank up the price of more than one quarter of the island’s food because of various tariffs. Then add in the fact that the pound is worth considerably less than it was and so will buy less for the same price. This means that now more than 50 percent of food will cost more, and probably a lot more. Don’t forget many people have also lost their jobs and that the government’s income from tax revenue is down as a result.

Now consider that the UK sends 70% of its food products to EU—or did. To some degree UK food will be more attractive to buyers in Europe because the exchange rate will reduce the price, but that price will be more than offset by the additional tariffs. No problem, right? “We just stop selling our stuff and go self-sufficient.” Well, no. The UK’s biggest foodstuffs export category? Beverages. Biggest imports? Fruit & veg, followed by meat. I love beer, but I’m guessing I’m not the only one who would choose dinner over a pint.

When food becomes scarce and expensive, who suffers most? The poor. Given that many in the UK are already using food banks (food bank use is at a record high) think how many will go without in the future. Let me spell it out for you: there will be fewer jobs paying less money; that money will buy less food; fewer people will be able to donate to food banks; so while demand on food banks will accelerate the resources available will plummet. Some schools are already reporting that 1 in 5 children are going hungry. At a guess (it’s just a guess) this will more than double. Imagine: 40% of all children in the UK hungry. Perhaps you should re-read Dickens to refresh your memory of what that looks like. While you’re at it, ponder the passages about stench and pollution because without the need to stick to the EU’s many environmental regulations companies will ignore inconvenient and costly measures to protect the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the soil in which we grow what food we can.

Child hunger leads to malnutrition. Malnutrition has long-term consequences. The effects will be with us for many years. Probably longer than the Second World War—when the government could enforce food rationing and mandate the ploughing of private land into fields.

So Brexiteers, are you happy yet? Will you be happy when your pretty garden has been dug up, when you can’t get your nice wine or chocolate anymore, when while there’s lots of good old British beer (except, oops, not so many hops to go around because that land use has been turned over to vegetables, rubbish vegetables at that because, hey, this isn’t Greece or Italy or the south of France, the climate is much less friendly and imported fertiliser is very pricey) you can’t get an orange. Oh, and you’ll have to do the hoeing and harvesting and equipment maintenance yourself because all those handy low-paid immigrants will have vanished. (There again, you could rent a few starveling urchins to grub about on the cold stony soil. But replacing them all the time because of their annoying tendency to die off might get a little tedious.) Also, if you happen to get your foot crushed by the tractor (y’know, if you can afford the petrol to run a combustion engine) you won’t be able to get medical attention because a huge percentage of NHS doctors and nurses have gone back to where they came from. I certainly would, if I had to deal with MEPs who dressed like brownshirts, or Blood and Honour fascists stomping around in my town . But, hey, it’s probably okay. After all, you’ve got your sovereignty back. Famine and fascism are just details, right? Besides, given the crisis you’ll turn to law and order candidates, someone who will promise swift justice to miscreants, just as a temporary expedient of course, a strongman (because women can be strongmen too) who promised to close the borders and keep those nasty, resource-sucking immigrants out.

According to the latest figures (2015) from United Nation’s High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), last year 65.3 million people, the highest number on record, were forced from their homes. There are, for example, 2.5M refugees in Turkey, most of whom want to go to Europe and live a life free of terror, bombs, and the other horrors of war. Many of them want to go to Germany or the UK. Angela Merkel has consistently championed the acceptance of those in need but more and more countries (like Hungary) are turning their backs. Theresa May, promising a ‘clean Brexit’ has just joined their reactionary group. She is a stongman-in-training; she is going to pander to the fearful, xenophobic, and wrong-headed Brexiteers and essentially close Britain’s borders.

This is heart-breaking, inhumane, and fatal for tens of millions of people who desperately need help. Many of them now will die. Some are already being ‘repatriated’ to their country of origin where nothing good awaits them. There are times, frankly, when I hate the kind of world that will permit this. In my opinion human displacement will only grow. I believe it’s a direct result of the chaos provoked by climate change. I believe there’s no stopping it; to try is as futile as trying to hold back the tide. We should accept the change, accept the people, and help our fellow human beings.

But that’s not how others see it. What’s happening now is a general rise in anti-immigrant sentiment which is really a rise in Us v Them antagonism. For someone who has been Othered her whole life (a queer, crippled, immigrant woman) this is disturbing.

It’s disturbing not just for me—as I said earlier in this post, I’m luckier than most—but for those UK citizens who are second- or third-generation immigrants from, say, India or Pakistan who are being verbally abused and physically attacked by the bigots who have been unleashed by Brexit. It’s disturbing for universities whose multi-national and collaborative EU research grants are now at stake. It’s disturbing for companies and government agencies who can no longer hire experts who are not UK citizens. It’s disturbing and unsettling for everyone—even those who aren’t disturbed yet, because they will be.

Let’s look at the polities. The Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland share a border which, after the Good Friday Agreement (that finally ended 30 years of sectarian violence), is currently an informal affair. European citizens from the UK (Northern Ireland) and Ireland (Republic of Ireland) can move freely between the countries. As a result, the peace accords have become a living thing. But a hard border—the cessation of free movement of EU citizens between countries—will imperil the agreement. Once again, Ireland will probably be a place of strife and suspicion. (On the other hand, weapons will be scarcer: AK47s will cost more; Heckler & Koch will cost a lot more, as will Semtex.)

Scotland wants to remain in the EU; its citizens voted heavily in favour of Remaining. It will seriously consider leaving the union in order to do so; Wales may follow. So five years from now instead of a peaceful United Kingdom with a purring economic engine powering the fifth highest GDP in the world there will be a squabbling set of little countries separated by hard borders and seething with resentment, violence, and economic inequality.

It’s not only the UK that will break; I believe it’s entirely possible that the EU will gradually fray and dissolve. The GDP of the European Union is the second largest in the world; if that machine falters the impact will be widespread. Given that trade agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership are also looking very dicey[2] I think we’re in for hard times.

Some of these hard times will be a direct consequence of all the dog-whistling right-wing politicians have indulged in over years that have flared in open hostility with the campaign to leave the EU. Some of them stem from the global changes that provoked the sentiments behind the vote. Chicken or the egg, it doesn’t matter what’s cause and what’s effect. The end result for me is that I am no longer thinking of moving back to the UK. I am no longer considering Europe. I’ll stay in North America. If Trump is elected (still unlikely, but still possible) then I’ll start thinking about Canada. If they’ll have me…

[1] Admittedly inflation at this point could (maybe) rise, which would go a long way to wiping out the national debt. But inflation is just one among a host of factors. And inflation has not followed expected paths in the last few years, so really no one knows.

[2] I will vote for Clinton but her decision to condemn the TPP was not smart. Politically I understand why she thought she had to, but it was a foolish move. And, oh yes, I have things to say about Trump but that’s for another post.

October 5, 2016

#CripLit Twitter chat: Intersectionality, 12 October 4pm Pacific/7 pm Eastern

The third #CripLit Twitter chat, on disabled writers, diverse literature, and intersectionality, is scheduled for Wednesday, 12 October, 4 pm Pacific/7 pm Eastern. The first one was so fast and furious that for the second I prepared answer tweets ahead of time to give me more time during the actual chat for conversation and hosting. I was damn glad I did: it was even busier than the first time. (If you’re curious you can see a Storify of the first #CripLit chat: Disabled Writers and Disabled Characterst, and a Storify of the second #CripLit chat: Ableism in the Publishing Industry, courtesy of the fabulous Alice Wong.) So if I have time I’ll probably do that again in order to focus on interacting with others. If you’re a planner, or get overwhelmed by furiosity, you might want to consider doing the same.

#CripLit Twitter Chat

Disabled Writers, Diverse Literature, and Intersectionality

Guest host: Alaina Leary @alainaskeys

Wednesday, October 12, 2016

4 pm Pacific/ 7 pm Eastern

The Disability Visibility Project is proud to partner with novelist Nicola Griffith in our third #CripLit Twitter chat for disabled writers. Nicola Griffith is the creator of the #CripLit series and the DVP is the co-host/supporting partner. For our third chat, we are both excited to have guest host Alaina Leary, a queer disabled activist and social media team member of We Need Diverse Books™.

All disabled writers are welcome to participate in the chat including reporters, essayists, poets, cartoonists, bloggers, freelancers, unpublished or published. We want to hear from all of you! Check the #CripLit hashtag on Twitter for announcements of future chats that will focus on different genres or topics.

How to Participate

Follow @nicolaz @DisVisibility @alainaskeys on Twitter

Use the hashtag #CripLit when you tweet. If you only want to respond to the questions, check @DisVisibility’s timeline during the chat. The questions will be timed several minutes apart.

Check out this explanation of how to participate in a chat by Ruti Regan: https://storify.com/RutiRegan/examplechat

If you don’t use Twitter and want to follow along in real-time, check out the live-stream: http://twubs.com/CripLit

#CripLit Tweets for 10/12 chat

Welcome to our 3rd #CripLit chat! Created by @nicolaz, this chat will discuss diverse literature, intersectionality & disabled writers.

We’re thrilled to have guest host @alainaskeys of @diversebooks join us in this conversation #CripLit

If you respond to a question such as Q1, your tweet should follow this format: “A1 [your message] #CripLit”

Q1 Please introduce yourself, describe your background in writing plus any links about you & your work #CripLit

Q2 As a disabled writer, what does intersectionality mean to you? How does it impact your writing? #CripLit

Q3 Are there times when your identities are erased or devalued by publishers/editors? Why does it happen? How do you respond? #CripLit

Q4 Why is it essential to discuss intersectionality in relation to power & privilege in the publishing industry? #CripLit

Q5 How do your intersectional lived experiences contribute to the creation of diverse stories and characters? #CripLit

Q6 When did you first read a book w/ a character similar to you? How did you feel before and after? #CripLit

Q7 Do you write about all your intersectional identities? Why/why not? #CripLit

Q8 How can we improve disability representation in lit & all forms of diversity as part of the #WeNeedDiverseBooks mvmt? #CripLit

Q9 What are your thoughts on cultural appropriation & creative freedom of writers? #CripLit

Q10 Are disabled writers the ‘best’ ones to tell disabled stories? Do these stories belong primarily to us? #CripLit

This concludes our 3rd #CripLit chat! Please keep the convo going. Thank you very much to our guest host @alainaskeys!

Be sure to tweet co-hosts @nicolaz @DisVisibility questions, comments, and ideas for the next #CripLit chat

Additional Links

Disability Art, Scholarship and Activism

Nicola Griffith (5/18/16)

4 Important Reasons Why Disability Visibility Matters

Alaina Leary, Everyday Feminism (9/27/16)

Why Intersectionality Can’t Wait

Kimberlé Crenshaw, Washington Post (9/24/15)

Perspectives of Authors with Disabilities, Part 1

Lyn Miller-Lachmann, We Need Diverse Books

Perspectives of Authors with Disabilities, Part 2

Lyn Miller-Lachmann, We Need Diverse Books

Looking Back: From Deaf Can’t to Deaf Can

Angela Dahle, We Need Diverse Books (8/31/16)

Disability in Kidlit

http://disabilityinkidlit.com

About

Alaina Leary is a Boston-based editor, social media manager, writer, and intersectional feminist activist. Her work has been published in Cosmopolitan, Marie Claire, Seventeen, Everyday Feminism, BUST, and The Establishment, among others. She is pursuing an MA in publishing at Emerson College. When she’s not reading, she spends her time at the beach and covering everything in glitter.

Website: http://www.alainaleary.com

Twitter: @alainaskeys

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Alainaskeys/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/alainaskeys/

Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/alainaskeys/

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/alainaleary/

Nicola Griffith is a British novelist, now dual US/UK citizen. In Yorkshire, England, she earned her beer money teaching women’s self-defence, fronting a band, and arm-wrestling in bars, before discovering writing and moving to the US. She was diagnosed with MS the same month her first novel Ammonite was pubished. Her other novels are Slow River, The Blue Place, Stay, Always and Hild. Her essays and short fiction have appeared in an assortment of academic texts and a variety of journals, including Nature, New Scientist, Los Angeles Review of Books and Out. Among other honours she’s won the Washington State Book Award, the Tiptree, Nebula, and World Fantasy Awards, the Premio Italia, and six Lambda Literary Awards. She is married to writer Kelley Eskridge and lives in Seattle where she emerges occasionally from work on her seventh novel to drink just the right amount of beer and take enormous delight in everything.

Twitter: @nicolaz

Blog: https://nicolagriffith.com/blog/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/nicolagriffith

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/user/amm0nit3/playlists

Alice Wong is a San Francisco-based disability advocate, freelance journalist, television watcher, cat lover, and coffee drinker. Alice is the Founder and Project Coordinator for the Disability Visibility Project (DVP), a community partnership with StoryCorps and an online community dedicated to recording, amplifying, and sharing disability stories and culture. Currently she is a co-partner with Andrew Pulrang and Gregg Beratan for #CripTheVote, a non-partisan online campaign encouraging the political participation of people with disabilities.

Twitter: @SFdirewolf

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/groups/356870067786565/

Website: http://DisabilityVisibilityProject.com

September 23, 2016

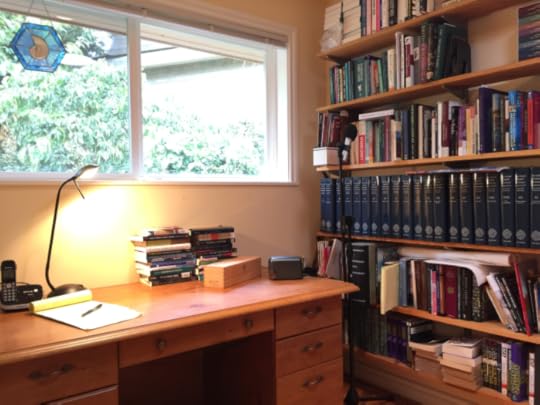

Writing space, September 2016

On Monday, Vulpes Libris republished a slightly edited piece about my writing space that I first published here five years ago. (One of their contributors Kate Macdonald wrote a splendid review of Hild. Kate also runs her own site, on writing, reading and publishing, and wrote a great academic paper arguing that “writing the past as an estranged history gives authority to the female experience in the historical novel,” referencing my work and that of Naomi Mitchison’s.) Anyway, the VL piece has prodded me to post this update. (ETA: But do go read that first post: there’s lots of info in it about the Armagnac box I’ve repurposed as a giant pencil box; why I have the OED on paper; where that shell comes from, etc.)

In the last five years my office has changed only slightly. It’s still painted butter yellow, still occupies the dark NW corner of our house, and still has two desks. Probably the biggest difference is that the larger of those desks has moved 90 degrees. It’s now under the window. This way I have a big space in the centre of my office for exercise and to zip from one desk to the other in my not-quite-ergonomic-enough chair. (Any suggestions for a good chair?)

You can see that in this photo, taken last week, the tree is not in bloom. Soon, in fact, the leaves will be changing colour. They turn a beautiful sherbet pink and apricot which every year I try to capture on camera and every year fail. One day technology will improve enough to get it.

The hanging shell is still there, still set in stained blue glass to catch the light. By the desk you’ll see the same microphone stand but the microphone is modern; it does many nifty things. The phone, too, is new, as is the pencil sharpener. I got tired of the old one breaking so I splurged on one of those electrically-powered heavy-duty sharpeners that schools use. Last year we had a major clear-out of books, fiction and not. So you’ll see my office now only carries research non-fiction (lots of history, and nature, and a bunch of texts for the big project I’m not talking about yet). Add to that my favourite dictionary in 20 volumes (love that book!) and a few copies of my novels for giveaway purposes. Oh, there’s also a new desk lamp.

One big thing missing from last time: no humongous pile of typescript printed out for edits. I’m still writing Menewood. When it’s done it will be even bigger than the Hild print-out.

The small desk with screen and keyboard is still tucked in the corner to avoid distractions.

The maps on the wall are still, on the left, the south sheet of the First Edition Ordnance Survey map of Britain in the Dark Ages, and on the right, the north sheet of the OS Ancient Britain. (I’m not sure what edition it is, but the visual style is pretty different). I refer to them fairly often, but what I use most these days is a map that’s too big to hang in my current space: the Second Edition Ordnance Survey map of Britain in Dark Ages. It’s pretty good but far from perfect. See those hand-made single-sheet maps on the file folders on the bar-trolley I use as mobile cabinet? Those are my own researched maps—different to OS stuff because they these take into account all the drainage changes from 11th century onwards, particularly Vermuyden’s massive scheme in the 17th. Also, there’s new information regarding Roman roads in the area. The map I’ve linked to above has names I don’t actually use in the book, because it was an early attempt to figure out what things might have been called in Old English. Further thought shows I got some of it pretty wrong—Æxigland, for example, might be better rendered as Haksigland. But I’ll probably use a mix of Brythonic and OE names anyway, as I’ve already done for some of the rivers and places, so many of the names will be quite different.

I have a new screensaver, Lu Jian Jun’s The Lady in the Forbidden City—a wonderful painting by the same artist who painted our Antique Dressing Table, that is, the painting we call Flossie. Here’s a blurred low-light version of Flossie courtesty of crapcam, or a slightly better version here, still taken with crapcam but with explanation.

The computer itself is a new Mac Mini, so small it’s hidden behind that pile of paper, but the screen is long past due for replacement. I want something with better resolution and a built-in webcam. (That’s an ancient Logitech that keeps failing.) Eh, I’d rather have a new desk, a nifty sit-stand thing. Meanwhile, as you can see, I’m still using the Klipsch speakers; I loathe and detest having things on or in my ears, so I use headphones as little as possible.

Also on the desk, silicon hand-squeezy things—vital for someone who spends so much time at the keyboard. On the trolley are three ancient Klutz juggling sacks. I learnt to juggle years ago, got pretty good at it, then because of progressive MS I could no longer catch and throw properly. However, in the three months, due to the wonders of a new drug (a potassium channel blocker), I have now recovered some function, so I’ve been slowly relearning. I’m not very good—the drug is good but it’s not a miracle—but at least I can now approximate juggling again. Soon I might venture back to the ukulele—which will thrill me but might lead to neighbourhood suffering (I have an amplifier…).

Not visible, but something that’s made a huge difference this year, the solar tube that renders the previously dark NW corner office brilliantly bright—so bright I keep trying to turn off light that’s not on when I leave the room…

Which I’m about to do, to eat breakfast. Enjoy poking around a big while I’m gone.

August 30, 2016

Some thoughts on Ableism & the Publishing Industry

Thanks to Alice Wong the Storify of the second #CripLit Twitter chat is up. It’s way too big to embed here (I haven’t counted but we trended on Twitter again).