Nicola Griffith's Blog, page 18

February 21, 2024

Me and Kelly Link, Feb 28, Seattle

On Wednesday February 28th, 2024 @ 7:00PM – 8:30 PM I’ll be at Elliott Bay Book Company talking with Kelly Link about her fabulous fantasy novel—her debut novel!—The Book of Love. Kelly is well know for her smart, sly and sideways stories, but she might perhaps be even better at full-length. Come find out!

Lots of details here.

And, yes, this does mean I’m doing two events in one day—London, virtually, in the morning and Seattle, in-person, at night…

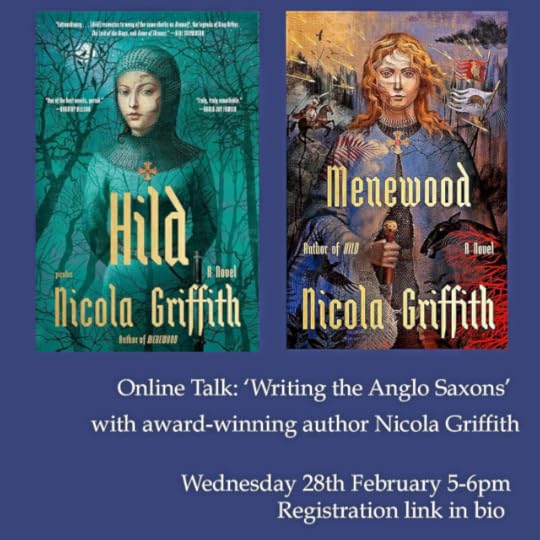

Writing the ‘Anglo-Saxons’ — Wednesday, 28 February (virtual)

On Wednesday, 28 February, 9:00 AM PT/5:00 PM UK, I’ll be doing an event for Westminster Libraries, London. In “Writing the Anglo-Saxons” I’ll be discussing writing historical fiction set in Early Medieval Britain with Kate Macdonald. Kate helped me out with a last-minute edit of Menewood and she’s a brilliant reader, book analyst, and friend. She is the mind (and muscle, and mover-and-shaker) behind Handheld Press. I’m so looking forward to this one!

The talk will be 40 – 50 minutes long, followed by a Q & A. Audience members will have the opportunity to submit questions in writing via the Q & A live chat. Register here for free.

And, yes, the sharp-eyed among you will spot that I’m doing two events that day: this one in the morning for a library in the UK, and another, with Kelly Link, in-person right here in Seattle. Perhaps the hardier souls among you will attend both!

February 17, 2024

The cost of bathing while disabled

Weirdly, I couldn’t find a picture of the model we chose but this one is sort of similar

How much does it cost to swap one bathtub for another? Guess. Imagine that all the plumbing will stay in the same place, you have a perfectly-working, almost-new hot water tank, and all parts are standard-size. Not much—or so you’d think. Obviously, here in Seattle, parts and (especially) labour and sales tax, cost more than almost anywhere else in the US except parts of New York, but still, you’re doing a straight swap of one tub for another, using the same pipes, the same drains, the same walls in the same places, the same floor—so how bad could it be?

Very bad, it turns out. $41,000+ worth of bad. Why? Because I’m a crip, and that means every single goddamn thing I need costs three (or five or ten) times as much as it might for a nondisabled person.

Let me explain. I’m reaching the point where I can no longer reliably get in and out of a standard bathtub, so I’m transitioning to a walk-in tub—the sort that has a door that opens in the side so you don’t have to climb over it but can step through. And that’s where the problem starts. If you can’t step over the side of a tub, manufacturers assume (correctly) that standing up from a lying position in an ordinary soaking tub is also difficult. So walk-in tubs are, by default, also tubs you sit in: no stretching out and sliding down to your chin and blissfully floating on your back in a pool of warmth. No. You sit with a straight back. To stay warm, the water has to come up to your armpits. Which means the tub has to be very deep. Which requires double the amount of hot water using by an ordinary tub.

So now as well as a new tub (and more on that in a bit) you need a high-capacity hot water tank. These aren’t cheap—which is especially galling when just four years ago you bought a brand new one with a spiffy recirculating system and it’s in perfectly good order, just too small. But, well, okay, if it has to be done, it has to be done And it’s just a few thousand. Except, well, no. You see, as you’re a crip you’ve previously had to use half what was the garage space for a wheelchair lift (which of course also cost a shit ton of money, but we won’t go there today) which meant the only place to put the hot water tank was—and is—the attic. And a big tank won’t fit up there. So now you have to tear out not just the tank but that whole system and put in a tankless (or multipoint) gas water heater.

Well, okay. How bad could that be? For most people, not bad—and on the bright side there are energy-saving rebates, plus you don’t have to worry about rusting tanks failing in the middle of the night. So hey not so bad. But for me, for the tub I need? Very bad—very expensive.

Imagine running a bath; it takes maybe six or seven minutes, but then you take off your clothes and climb into a tub full of lovely hot water, sink down up to your chin, and think, Aaaaah… Now imagine stepping naked into a cold, empty tub and sitting there shivering while it slowly fills—taking twice as long as an ordinary tub. No fun. So what you need is something that will fill at 16-18 gallons a minute. But to heat that amount of water instantly as it runs through the pipes you need a gas output of 199,000 BTUs. And for that amount of gas—at least five times the rate an ordinary water tank needs—you need to run a secondary gas line from the meter. And of course pull a permit and then pay for an inspection.

Back to the tub itself. As well as the speed-of-filling problem, there’s the speed of emptying. Think about how long it takes for an ordinary bath to drain. Several minutes. Now double that. And remember you’re sitting there wet and naked for the whole time because you can’t open the door until every drop of water is gone. So you need the water out of that tub faster than gravity can do it. And for that you need electric vacuum pumps. And you also need some kind of build-in heating of the tub walls so you don’t just freeze in place. So then you need an electrician. And then the electrician takes one look at your existing panel and shakes his head because apparently 120 amps won’t do it. What you need, it turns out, is 200 amps Which means you need to replace the whole panel. Plus of course pull another permit and pay for another inspection.

The tub draws so much juice because it does a lot of things. As well as those vacuum pumps it has an ozone self-cleaning and air-drying system; it has air jets and water jets that are selectable and directable; it has nifty underwater ‘chromotherapy’ lights that can cycle in different colours and patterns (though sadly I can’t sync them to a playlist—no such thing as Apple TubPlay); an aromatherapy option that infuses the air jets with essential oils (if, y’know, you’re not allergic to everything, as I am); an inline tub-wall heating system so you can sit in that tub for six hours if you want and the water never goes cold; plus an unconditional lifetime guarantee on every bit of it. Also, given that MS is a relentlessly degenerative disease, I decided to future-proof this considerable investment by opting for the model that allows for a build-in Hoyer lift as/when transfer from a wheelchair gets too hard.

All this, of course, means the tub is big. So big we had to dismantle the bathroom door frame to get it in—and rebuild it afterwards. It all adds up. Specifically, the whole thing, parts and labour and permits, adds up to a smidge north of $41,000.

So, what’s the cost of bathing in Seattle when disabled? $41,000. $41,000. FOR A BATH. You can get a brand new Honda Odyssey minivan for that! Except, oh, right, I can’t, because I’m a crip: I have to spend $91,300 on a used, two year-old Odyssey instead. But I’ve talked about that before…

February 4, 2024

Snippets—Women and autoimmune disease, the first wine, early Americans, and how cats purr

Some of this stuff dates from late last year when I was too busy with Menewood stuff to comment. But as some of my favourite things in life (well, the favourite things we can talk about in polite company) are cats, wine, and history, and as one of my ongoing personal concerns is autoimmune disease, I thought, Eh, let’s combine them. We’ll start with the weighty stuff first then lighten up a little.

Why women get autoimmune disease more often than menNote: Given the nature of the science under discussion here I’ll be using ‘women’ and ‘female’ as shorthand for those with XX genotype. But do bear in mind that gender expression, phenotype, and genotype do not necessarily align.

About 80% of people with autoimmune diseases (e.g. lupus, rheumatoid arthritis) are women.1 In most mammals females have two X-chromosomes (XX) and males one X and one Y (XY). People are mammals: women are typically born with XX and men XY.2 Each X chromosome contains the full set of genetic instructions we need to build the proteins that run and maintain all our physical processes: no proteins = no life. But too many proteins are deadly. So one of women’s two X chromosomes has to be turned off to avoid fatal duplication. A recent paper in Cell suggests that it’s this process that’s a major driver of autoimmune disease.

Here’s the abstract:

Autoimmune diseases disproportionately affect females more than males. The XX sex chromosome complement is strongly associated with susceptibility to autoimmunity. Xist long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) is expressed only in females to randomly inactivate one of the two X chromosomes to achieve gene dosage compensation. Here, we show that the Xist ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex comprising numerous autoantigenic components is an important driver of sex-biased autoimmunity. Inducible transgenic expression of a non-silencing form of Xist in male mice introduced Xist RNP complexes and sufficed to produce autoantibodies. Male SJL/J mice expressing transgenic Xist developed more severe multi-organ pathology in a pristane-induced lupus model than wild-type males. Xist expression in males reprogrammed T and B cell populations and chromatin states to more resemble wild-type females. Human patients with autoimmune diseases displayed significant autoantibodies to multiple components of XIST RNP. Thus, a sex-specific lncRNA scaffolds ubiquitous RNP components to drive sex-biased immunity.

Dian R. Dou, et al (2024). Xist ribonucleoproteins promote female sex-biased autoimmunity, Cell, VOLUME 187, ISSUE 3, P733-749.E16, FEBRUARY 01. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.12.037

What all that boils down to is that something called XIST, made of long strands of RNA, wraps itself around one of the X chromosomes; the RNA attracts all sorts of proteins; and those proteins form complexes that smother the genes inside and prevent them sending out instructions to build more proteins.3 Every cell in a woman’s body contains this XIST complex. When in the natural course of things when cells die these complexes are exposed to the immune system. The immune system can then produce autoantibodies—that is, the XIST can trigger an inflammatory immune response as those autoantibodies go after otherwise healthy parts of the body mistaking them for alien intruders.

Why is this interesting? Two reasons. One, if you can pinpoint the exact autoantibody involved in a specific condition then you have an accurate diagnostic tool: you can detect a problem before symptoms manifest. Two, if you understand the specific autoimmune trigger then you cn start looking for ways to block it—which could lead to a hyper-targeted therapy. Today, most autoimmune disease is treated by shutting down huge swathes of the immune system—which is not just only partially successful as a treatment but quite dangerous in itself. Or, as with some drugs used for scleroderma, they target limited pathways of the disease, such as the decline of lung function.4 All drugs that suppress chunks of the immune system are dangerous. A hyper-targeted therapy would not only be more effective it would be much, much safer.

The true origins of wineThe story of wine has previously been told by archaeologists fussing with organic residue on pot sherds, or paleobotanists waxing ecstatic over bits of grape seed or pollen. Using this kind of material evidence, it was previously assumed that wine cultivation dates back 7,000 years, or 6,000 yearsor 9,000 years depending on who you were talking to andi which country. But now a large international group of researchers collected and analyzed 2,503 unique vines from domesticated table and wine grapes and 1,022 wild grapevines. By extracting DNA from the vines and determining the patterns of genetic variations among them, they found it dates back 11,000 years:

When the last Ice Age ended and the glaciers retreated, roughly 11,000 years ago, something appears to have changed among the wild grapevines of Asia. They became domesticated. The first farmers on Earth began cultivating the best vines with the biggest, juiciest grapes. Wine, and civilization, soon followed.

Washington Post

Grapes were probably the first domesticated crop. We have agriculture because of grapes. We have civilization because of grapes. Wine is good.

Pushing back the date of humans in North AmericaA while ago I was talking about pushing back the date of humans in the Americas. We now have another >20k years ago date, this time from North America—New Mexico, to be precise.

New research confirms that fossil human footprints in New Mexico are likely the oldest direct evidence of human presence in the Americas, a finding that upends what many archaeologists thought they knew about when our ancestors arrived in the New World.

The footprints were discovered at the edge of an ancient lakebed in White Sands National Park and date back to between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago, according to research published Thursday in the journal Science.

AP

According to Nature, the finding supports the idea that “people skirted down the Pacific coast of the Americas after crossing the Bering land bridge, rather than waiting until ice-age glaciers retreated from inland routes.” The timeline is also supported by indirect evidence (e.g. carvings made from dateable animal bone and horn) but the footprints are unmistakably and directly human. I’m still betting we can push the timeline back significantly. Stay tuned.

How cats purr—maybeHow do cats purr? I mean, they’re small beasties and purrs are deep and resonant—it doesn’t make a lot of sense. Deep sounds need long vocal cords. Yes, cats are masters of space and time—obviously they can defy the laws of physics—still, wouldn’t it be lovely to have a more down to earth explanation? And now we do! A new study in Current Biology suggests purring is made possible by fibrous pads in the cat’s vocal folds. And, what’s more, they can take their brains offline to do it. Maybe. (Note: no cats were harmed for the purpose of this study. Larynxes were taken from pets who had to be put to sleep due to old age or illness.)

People with Klinefelter syndrome are phenotypically male but with XXY genotype. They have the same elevated risk of autoimmune disease as women. ︎But the ratios vary wildly from one condition to another. In Sjögren’s for example, the ratio is 19:1.

︎But the ratios vary wildly from one condition to another. In Sjögren’s for example, the ratio is 19:1.  ︎Mostly—some genes escape inactivation, and that’s also a problem. But people have known about this for a while, and while interesting it isn’t very helpful

︎Mostly—some genes escape inactivation, and that’s also a problem. But people have known about this for a while, and while interesting it isn’t very helpful  ︎I’m focusing on scleroderma here a) because it helps to be specific, and b) because I have a very personal interest: my sister, Carolyn, died of scleroderma when she was 47.

︎I’m focusing on scleroderma here a) because it helps to be specific, and b) because I have a very personal interest: my sister, Carolyn, died of scleroderma when she was 47.  ︎

︎

January 17, 2024

Talking about Ursula Le Guin for the British Library

Tuesday, January 23, 2024 — London, UK and Virtual — The British Library

Event: 7:00 pm UK/11:00 am Pacific“The Realms of Ursula K Le Guin,” a public conversation between me, Julie Phillips (Ursula’s biographer) and Theo Downes-Le Guin (her son), moderated by Sarah Shin (editor of Space Crone). Held as part of the British Library’s flagship exhibition on FantasyTickets are £6.50, or £3.25 for Library membersThis is an online event streamed on the British Library platform. Bookers will be sent a viewing link shortly before the event and will be able to watch at any time for 48 hours after the start time.January 15, 2024

Snippets—sex-chromosome syndromes in history

Recently, in Communications Biology, Kyriaki Anastasiadou (Francis Crick Institute, London) et al report they have identified aneuploidies (atypical autosomal and sex chromosome karyotypes—that is, something other than XX or XY) in five people buried in Britain over the last 3,000 years, including:1

the oldest known instance of mosaic Turner syndrome dating to the Early Iron Age, three individuals with Klinefelter syndrome, spanning from the Iron Age to the Post-Medieval Period from England, an individual with 47,XYY syndrome in Early Medieval England and an Iron Age infant with Down syndrome.

Anastasiadou, K. et al.

These people would have displayed visibly different physical appearances and/or behaviours and/or health—the woman with Turner would be shorter than average whereas men with Klinefelter tend to be taller, with large hips and breasts—were, as far as it’s possible to tell from their remains, treated no differently than those with the usual binary XX or XY chromosomes. Nature interviewed Anastasiadou along with a couple of other researchers who weren’t part of the team.

There is no evidence that the people were treated differently from those without the syndromes, says Anastasiadou. “There didn’t seem to be anything different about how they died or how they were buried at first glance,” she says.

“This is a major breakthrough and provides us with a window into the perception and treatment of difference in ancient societies,” says anthropologist Bettina Arnold at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. The approach could shed light on what it means to be human, she says.

“The more studies like this are done, the better we can explore how past societies viewed sex and gender, or in the case of certain [genetic syndromes], how disability may have been understood in the past,” says archaeologist Ulla Moilanen at the University of Turku in Finland.

Ancient DNA reveals first known case of sex-development disorder, Nature.com

For me the really interesting part is how surprised those Nature commentators seem to be that people of the Long Ago behaved like, y’know, people: they treated difference with respect; that every person matters. Treating people differently is usually a product of fear—classically and most obviously of disease. But people learn pretty fast that this kind difference-at-birth isn’t contagious, and how can one be afraid of a tiny baby with a sweet smile? Or a toddler you’ve known since she was a baby? Or a young adult (ditto)? Or an old woman? I’ve always believed that our factory setting, what we’re born with, is kindness. It’s our default; it’s something we unlearn. Here in the 21st century, we should take note.

Anastasiadou, K. et al. Detection of chromosomal aneuploidy in ancient genomes. Commun. Biol. 7, 14 (2024). ︎

︎

January 11, 2024

Stay warm, Seattle!

Temperatures in Seattle this weekend could be heading as low as 11° F ( -11.5°C). Even if it doesn’t go quite that low (there’s still wiggle room in the forecasting models) it’s going to be *cold*. On the plus side, it seems that we’ll avoid Snowpocalypse—Portland’s going to get that. Again.

I know folks in the Midwest and Northeast laugh at Seattle people and think we’re like Kenneth the emu.

But Seattle climate is modulated by the Kuroshio Current; we’re not used to snow or cracking cold. We don’t have snow-mitigation infrastructure (the ploughs, the sanding/salting trucks, underground and/or otherwise enclosed paths). And we’re built on a series of very steep hills. If you’ve ever seen an articulated city bus glide backwards down a city-centre hill and turning with slow grace in a waltz of doom, you, too, might pause.

Weather forecasting is improving (it’s now as accurate to five days as it was 10 years ago to two). Even so, it’s not infallible, and I’m very much in the ‘Hope for the best, plan for the worst’ camp. Our fridge is stocked, supplemental power packs are charged, and media downloaded. If you have the resources to do the same, you might want to consider it. And if you know people who don’t have those resources, maybe think ways you offer help if it’s needed.

Meanwhile, if you want to track the weather this is my preferred site. Stay warm, people!

January 10, 2024

Author Bios: Saying the quiet part out loud

On Monday I posted a photo and talked briefly about portraits. Today I’m thinking about word portraits—author bios.

Two days before Christmas, an interviewer used my rather cavalier (lively? light-hearted?) website bio to introduce a lengthy and serious conversation about prose style and the nature of literary creativity—not light or careless in any way. The dissonance between the bio and the essay/interview was jarring. This isn’t the interviewer’s fault—I sent him the link; it’s my fault for assuming he would pick out the factual nuggets to build his own, more suitable bio. And, well, you know what they say about assumptions—this isn’t the first time it’s happened. The difference was, this time I realised I was tired of it. I unpublished my About page. Then realised it was the day before Christmas Eve, an author website should never not have an About page—it’s sort of the point of the thing—and I had just forty minutes before cocktail hour, after which I was closing up shop until after the holidays. Despite the time constraint I tried to imagine what a reasonably serious, factual, unembellished but not diffident bio might look like, wrote 900 words, posted it, and went to have a drink. Today I’m finally reading what I’ve written and thinking, Hmmm. (Also fixing a couple of typos.)

Nobody really talks about about Author Bios. Consequently, when I was first asked to write one (in the late 80s, for Interzone, or maybe Iron Women) I hadn’t a clue where to begin. If I’d thought about them at all I probably assumed somebody else wrote them. After all, as my English, trained-to-not-blow-my-own-horn inner voice reminded me, If you have to tell people you’re important/interesting, you’re not. Looking back, I’m glad I was clueless about this kind of self-promotion. I might never have begun this writing thing if I’d had any idea how much being a working novelist depends on blasting out your own brassy fanfares all the time, about everything: not just social media but essays, interviews, panels, readings, think pieces, puff pieces, listicles, blog posts, podcasts… It’s a very large part of the job. And all those things rest on the bio—usually between 500 and 1,000 words for your own website (the Inside Bio), and anything from 25 to 200 words elsewhere (the Outside Bio)1

Those Outside bios are remarkably easy to get wrong. By ‘wrong’ I don’t mean grammer, spelling, or facts but tone: sending the editor of, say, a short fiction anthology an earnest paragraph about your artistic intentions and your writing mentors only to find out on publication that all the other contributors are declaring their fealty to cheese or making quips about birbs and doggos. Or the other way around.

I’m being a bit disingenuous here. This has never actually happened to me but I’ve seen it happen to others, and it makes my toes curl in sympathy. It’s a question of understanding the zeitgeist feeling the vibe. This can be hard for newcomers, whether new to the profession or to a particular genre or category. A bio for the NYT is quite different to that for a small community press, or for an academic journal versus a picture book. No one tells you this. More accurately: no one ever mentioned it to me, and I, in turn, have never thought to mention it to anyone else until today. Why? Well, speaking purely for myself, when I first began I was so arrogant I just assumed that whatever I said would be perfect and if it wasn’t like other people’s bios then, hey, other people were wrong. A while later, swimming in the full professional tide, I just never thought about it. And now I’ve been doing it so long that even when I do pause for thought I don’t think anything of that—it’s just part of the job, as usual as the sun rising in the east.

Today, though, I’m going to say the quiet part out loud: If you’re sometimes not sure what to put in your Inside or Outside Bio, you’re not the only one. Of course you, reading this now, probably don’t need any advice, but perhaps one of your friends might find it useful to know how I approach it. If not, no worries: I find it helpful to work out my own thinking.

Let’s start with an Outside Bio. First, get word count guidelines. They’re usually short, some very short—from the one-line tag that goes after your review in a Sunday broadsheet, to the 100-word paragraph on the contributors’ bio page of a disability anthology. The reason they’re short is that, counterintuitively, they’re not really about you. No one buys the NYTBR because you reviewed a book in it—but having read your review they need to know how to weigh your opinion. So if your review of, say, a middle-grade novel about a bear, spits upon that book from a great height, your take-down is less likely to be rejected out of hand if your bio says, “Nicola Griffith won the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature for The Bear Who Ate Christmas,” rather than “Nicola Griffith is the managing editor of Astrophysical Review.” Both statements could be true, but only one matters in this context. For an anthology, the point becomes using your bio to reinforce what your story was about and give a potential new reader a reason to pick up some of your other work. The easiest way to demonstrate what I mean is to give your an example, so here’s a paragraph I wrote five or six years ago to go with a piece for a disability-focused publication:

Nicola Griffith: English novelist (now dual UK/US citizen) living in Seattle. Author of seven novels. Winner of Nebula, World Fantasy, Tiptree, Lambda Literary, Premio Italia, and Washington State Book Awards, among others. So Lucky, out in May 2018, is her first book from a disability perspective, a story that blazes with hope and a ferocious love of self, of the life that becomes possible when we stop believing ableist lies. Founder and co-host of #CripLit, a regular Twitter chat for disabled writers. Holds a PhD from Anglia Ruskin. Married to author & screenwriter Kelley Eskridge. Currently lost in the 7th century (working on the second novel about Hild of Whitby). Emerges to drink just the right amount of beer and take enormous delight in everything.

Here I was aiming to reinforce my crip credentials, both lived experience and academic, and my literary credentials. All while suggesting I’m at ease in different cultures and communities, that I’m queer, and have a great zest for life (an important counter to so many nondisabled people’s belief that all crips live sad grey existences). It also mentions two specific books to read, along with a link to find out more.

Here, on the other hand, is the bio I wrote for Menewood. It’s shorter and plainer. It has a lot less work to do because whoever’s reading it has probably already invested a good chunk of change in the book itself. I’m no longer trying to persuade them to find out more—if they like the book they’ll do that anyway. In a way, I’m reinforcing and congratulating the reader on their taste while at the same time suggesting that, yes, actually I do know what I’m talking about when it comes to both nature and interpersonal violence…

Nicola Griffith is a dual UK/US citizen who lives in Seattle, Washington. She is the author of award-winning novels including Spear, Hild, and Ammonite, and has written for Nature, New Scientist, The New York Times, The Guardian, and other publications. She is the founder and cohost of #CripLit, holds a PhD from Anglia Ruskin University, and enjoys a ferocious bout of wheelchair boxing. She is married to the novelist and screenwriter Kelley Eskridge.

There are other types of Outside bios—Artist’s Statements and/or Biobibliographies required by some conferences/conventions and grant applications—but I’ll skip those and get right to the heart of the matter, the Inside Bio, usually found on an author’s About page. This is the foundation on which everything rests, the font from which readers, journalists, and academics draw. Over the years I’ve taken different approaches, ranging from the self-deprecating false modesty of Nicola Griffith writes stories to tales of zany badassery, social and legal activism, fronting a band and arm-wrestling in bars. Over the holidays I did some thinking, and I’ve decided that the About page’s primary purpose is as a discovery tool. A beginning. An introduction. Imagine someone who knows nothing about publishing—what genres are, how they work, which which are admired—nothing about disability activism or gender bias, nothing about history or immigration, nothing about my personal background, and not one single thing about my writing. They need simple, obvious, fact-forward and easily-verifiable statements. In other words, more like a Wikipedia page with a little literary spice sprinkled on top. It’s truth, nothing but the truth, but not necessarily all the truth. Lots of touchpoints, lots of taking my space and taking credit where credit is due—without boasting or false modesty—and what spin there is, is subtle.

It’s not branding2 but it is a necessary step in the branding process. It’s less, This toothpaste will make you feel like a powerful, good-looking, smart shopper, than Hey, look, this is one of those pastes that clean teeth. It’s informational: I’m letting you know I’m here but I’m not selling you anything. It’s also a bit, well, impersonal. You don’t get the flavour of me. So after I’d written it I decided it needed something extra, and that turns out to be my old Writer’s Manifesto—written over a dozen years ago but still saying what I mean about why I write and how I feel about my fiction. The two together work well; in a little over a thousand words I think they give a reasonably rounded portrait of who I am now and where I’ve been. (And then, because journalists, librarians, and other working professionals sometimes don’t have much time, I wrote the grab-and-go version.) No doubt at some point—next week? in 10 years?—I think of something better, but for now, here it is.

Take a look. Let me know if you think I’ve left out anything essential—or if anything surprises you. And if you have any thoughts on bios in general—how you approach them, what you want from them, if you know of anyone teaching how to do them, lessons you’ve learnt whilke writing or reading them, how you feel about them in general—I’d love to hear them.

Not official terms. Just how I think of them. ︎I’ve written about branding before: “Branding: It Burns”

︎I’ve written about branding before: “Branding: It Burns”  ︎

︎

January 9, 2024

In the Stacks—a conversation with Curve

I’m delighted to announce that I’ll be doing an online event for the Curve Foundation next week, on Tuesday, Jan 16, at 5:00 PM PST. It’s free, and you can join from anywhere in the world. Sign up here.

What is the Curve Foundation, you ask?

Launched in 1991 as Deneuve magazine, Curve has been America’s best-selling lesbian magazine for nearly three decades. As Curve’s 30th anniversary approached, founder Franco Stevens reimagined how Curve will serve lesbians and queer women in its next chapter. Her journey to this historic decision is captured in the documentary film Ahead of the Curve.

Franco, along with a dynamic Advisory Council, started The Curve Foundation to empower the Curve Community – lesbians, queer women, trans women, and non-binary people of all races, ages, and abilities. The Curve Foundation will spur active storytelling and cross-generational dialogue around the Curve Community by supporting journalism inspired by the tradition of Curve magazine, investing in the next generation of intersectional leaders, and bolstering existing community archives as a resource to ensure LGBTQ+ women’s culture and history can be known.

The Curve Foundation

The interview initiative seems to be relatively recent. I know of two interviews so far, with Jewelle Gomez and Katherine V. Forrest—icons of lesbian fiction. So, wow, I’m honoured to be included.1 If you want to know what you might be getting into before you sign up, get a taste of Jewelle Gomez’s conversation here. I think if you sign up but can’t make the live event—I know the timing is awkward for folks in Europe—I think there’ll be a recording you can access. But I’ll check on that.

So if you’ve always wanted to know something about my work, about me, about writing queer fiction, and/or about Hild, this is a great opportunity to ask. Sign up here. It’s free.

See you next week!

Hey, I’m a dykon! ︎

︎

January 8, 2024

Portraits

Nicola Griffith, November 2023. Photo by Mark Tiedemann.

Nicola Griffith, November 2023. Photo by Mark Tiedemann.Image description: White woman with short fair hair going grey, wearing a black leather jacket and sitting in a black wheelchair at a black table surrounded by beer and pens, and talking animatedly to someone off camera

Mark Tiedemann, a writer and friend we’ve known for many years, posted this photo at the weekend. It was taken in November in Kansas City, at the mass autographing session at World Fantasy Con. It took me by surprise—I hadn’t known he was taking it; I hadn’t seen the photo before he posted it—and for a split second I didn’t like it. I thought I looked old and tired in an old and ugly hotel basement room. Then I grinned: I am old! I was tired! (Weeks of book tour will do that to a person.) The room was horrible (but the people were lovely)! But I still look like me, that very particular juxtaposition of fair-going-grey dyke haircut, ancient black leather jacket and black wheelchair, the beer and the pens, and the obvious engagement with whoever I’m talking to—very probably a reader.

This is who I am. It may not be the most beautiful photograph of me but it’s nonetheless a remarkably true portrait. And that’s a gift.