Nicola Griffith's Blog, page 16

July 18, 2024

Butter-side-down papers

This short post exists so that I can link to it in the future—most immediately from an upcoming post about sex and gender—and not have to constantly explain what I mean.

About thirty years ago, as I sat at the breakfast table reading the news, I burst out laughing. Kelley wanted to know what had tickled me and I explained that I had just read a proof, by Robert Matthews of the University of Aston, that, indeed, toast does tend to fall butter-side down:

We investigate the dynamics of toast tumbling from a table to the floor. Popular opinion is that the final state is usually butter-side down, and constitutes prima facie evidence of Murphy’s Law (‘If it can go wrong, it will). The orthodox view, in contrast, is that the phenomenon is essentially random, with a 50/50 split of possible outcomes. We show that toast does indeed have an inherent tendency to land butter-side down for a wide range of conditions. Furthermore, we show that this outcome is ultimately ascribable to the values of the fundamental constants. As such, this manifestation of Murphy’s Law appears to be an ineluctable feature of our universe.

— Tumbling toast, Murphy’s Law and the fundamental constants 1

Since then, whenever one of us sees something perfectly obvious proved scientifically, we grin. Butter side down…

For which Matthews won the Ig Nobel Prize ︎

︎

July 17, 2024

Bony lives!

There seem to be horses in many of my books. And cats. Cats don’t surprise me; I’ve lived with them all my life. Life isn’t life without a cat in it. Horses, though… My family did not have the time/money/cultural expectation to spend time with horses. I grew up with zero knowledge of them except miserable trails up and down the beach on a sad worn out old pony on a seaside holiday. (I hated it. I felt so sorry for the poor beast.)

When I was about 11 my mother started a business that started making money—not gouts of money, just Oh, wow, maybe we could do do middle class things now kind of money, like go to a café and have a glass of lemonade each instead of having to share four between a family of seven (that is, three were shared; my father, of course, always got his own). By the time I was thirteen, two of my sisters had left home, another sister was about to, the business was doing solid numbers, and we could afford to spend a week in summer somewhere that wasn’t a damp self-catering bungalow on the cheapest parts of the northeast coast. We went across the Pennines: in different years to Cumbria, Lancashire, Cornwall, Somerset. I’m not sure whereabouts we were the summer I was 14 and I saw a sign near the beach saying, Riding Lessons.

It took some serious pestering on the part of me and my little sister, Helena, to persuade my parents to cough up for two days at the stables (and I think what swung it was the thought that they might then have precious hours to themselves—a pearl beyond price). Anyway, the next day we presented ourselves, 14 and 11, for instruction.

Looking back, I think I was extraordinarily lucky. This wasn’t some kind of tourist hack stable—they had excellent horses. One—not for beginners, obviously; only to be gazed at reverently—was the half-brother of Triple-Crown winner, Nijinsky Helena and I got serious instruction. From the first time of being on an actual horse (Oh my god, I thought, as I swung into the saddle. These things are high…) to the end of the second day I had learnt to walk, trot, lie on my back on the horse with arms crossed while it walked, canter, take small jumps (though they were so small I’m not sure they really qualify as ‘jumps’) to finally feeling (erroneously, I’m sure) that if I’d been born in a different family and socioeconomic circumstance I might have become a real rider. I loved that feeling of working with a massive beast in mutual cooperation (again, I’m probably fooling myself, but that’s how it felt: as though the horse were teaching me, and very patiently). For about two weeks after we got home I dreamt of horses…but then never got on one again until decades later when Kelley and I took a vacation at Sun Mountain in the Methow Valley. I’d had MS for years by then, so it was a challenge—but Kelley and I did a two-hour trail ride near Winthrop, riding Western style. It was hard, and I was glad we moved slowly with an expert trail guide, but it reminded me of the pleasure I’d had that first time. (Also, it seriously hurt to walk for two days afterwards but it was worth it.)

And that’s it; that’s the sum total of my equine experience. Yet when I wrote Ammonite it wasn’t hard to conjure the feeling of being on a horse, and how horses—like people—can kind of lie to you, or at least pretend things to avoid doing extra work. And then in Hild and Spear and Menewood the horses all had their own personas. Being English, of course, an astonishing percentage of North Americans are not the least bit surprised I write about horses because they assume I grew up riding around my country estate (and know everything about perennial gardening, and probably met the queen a time or two at a garden party). I’ve mostly given up trying to persuade people I was a city kid whose understanding of nature was watching a ratty squirrel cough itself awake on the telephone wires outside my bedroom window. But believe me when I tell you: a) I am surprised at how often horses appear in my work, and b) I know a hell of a lot less about horses, horse vocabulary, and horse anatomy than you might think.

Which is all just a long preamble to explain why, when the image first dropped into my head of the bony gelding that I eventually learnt was Bony—the equine hero of Spear who teaches Peretur to ride, his coat was grey. Not the white that horse people call grey, but, well, grey. So that’s how I described him. It wasn’t until I was doing all the research I needed for the horse logistics of Menewood that I began to understand horse description terminology like dun, and true grey, and bay, and chestnut. And that certain leg/ear/nose/mane/tail colours fit together in certain patterns.

When I was creating maps for both Spear and Menewood I made various line drawings to use as little doodles or icons of interest. One was of Flýte, the powerful dun mare that carries Hild through the second half of Menewood:

Then Spear came out and I made a map for it—and needed a picture of Bony but didn’t have time to figure out how to draw a bony gelding, so stuck the picture of Flýte in as a placeholder.

Click to embiggen

Click to embiggenI forgot that placeholders (like the ‘temporary’ names of the Echraidhe in Ammonite) have a nasty habit of getting stuck in place—and that I then have an even nastier habit of pretending no one will notice. In this case I told myself, Hey, most people are as ignorant as I am about these things; they won’t know a grey gelding from a dun mare from a hole in the ground.

And all that, in turn, is just a preamble to explain why, when friend and fellow writer Sarah Pinsker painted a lovely sculpture of Bony (sculpted by Rachel Lane) for me, he looks very like I first pictured him, except that his mane, tail, and stockings are dark—because Sarah (who know more about horses than I ever will) assumed from the horse on the Spear map that Bony was a dun.

Which is all to say, I am inordinately fond of my actual, tangible Bony and look forward to watching him amble across my desk for the next decade or so. And who knows, perhaps we’ll meet him again sometime…

July 16, 2024

Ammonite—available wherever books are sold

US editions of Ammonite (1993, 1996, 2002)

US editions of Ammonite (1993, 1996, 2002) UK editions of Ammonite (1993, 2012)

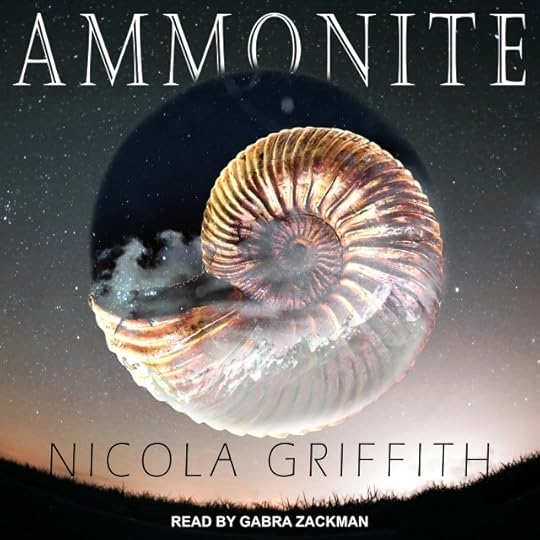

UK editions of Ammonite (1993, 2012) Audiobook of Ammonite (2020)

Audiobook of Ammonite (2020)Since the Esquire list thing I’ve had many emails and social media comments to the effect that, Damn, it’s a shame the book’s out of print! AMMONITE IS NOT OUT OF PRINT! It’s been selling merrily for over 30 years; I get royalty cheques twice a year. It keeps getting rediscovered—for example at the beginning of the pandemic when viruses were a hot topic—and it’s been a question in Trivial Pursuit (or was it Jeopardy? or maybe both?) and is still picked up now and then for bookclubs. I still get letters and email and DMs from readers testifying to its effect on their lives.

Here in the US it’s published (as is Slow River—which next year will be celebrating its 30th anniversary of being continually in print) by Del Rey (part of Penguin Randomhouse)1 and is available in print, ebook, and audiobook. Available wherever books are sold. Though some smaller shops might not have it on their shelves—they tend toi privilege newer books for display) they can order it for you within a couple of days.

In the UK it’s published by Orion (part of Hachette) as part of their Masterworks of SF series. Again, available wherever books are sold.

It’s also been translated into 13 different languages (and won the Premio Italia for best novel translated into Italian) but frankly I forget in which countries it is or is not in print. (Translations tend to be for limited time periods; books are always going away from one publisher and reappearing from another. I stopped trying to track it a while ago.)

The screen rights, however, have just come back on the market so if you’re interested in those, talk to my agent.

A perennial question about the book—Will there be a sequel?—has also had a resurgence in the last few days. I’ve spent 30 years saying, No, absolutely not. I felt I had said all I had to say about Marghe and Jeep and Company and gender and viruses. But last year I realised I’d left something unexplored. So it’s possible, other commitments permitting, that one day I’ll write a followup. If I do it wold most likely be a novella. We’ll see.

Actually, the audiobook is from Tantor—but you can get it from any major online platform, from Libro.fm and from your local library. ︎

︎

July 13, 2024

Ammonite makes Esquire’s “75 Best Sci-Fi Books of All Time” list

It comes in at #25, which is cool. You can read the whole list here. I like what they say about Ammonite—and in fact have already lifted a quote to go on my Ammonite page. I mean, who wouldn’t want to claim this?

Ammonite asks: When does a human become an alien? Gripping and gutsy, rich in layers of feminist and queer thought, Ammonite gleefully throws a stick of dynamite into the sci-fi firmament.

The list is pretty interesting. There are some books on there that I haven’t read but almost all of the ones I have I think deserve to be on a Best list. And it’s lovely to be in such good company.

Go take a look and see what you think. Feel free to suggest additions but let’s not diss any of the books already on the list.

July 5, 2024

The 25th Choice

It’s been a miserable week in US politics: vile weather1, the Supreme Court decisions, and the horror of the Trump/Biden debate. As people yesterday wished me Happy Fourth! I found myself wondering what, if anything, might make that possible in future years. Which led me to pondering what, if I had the power to temporarily bend a couple of dozen minds to my will, I could do that would make the most difference.

Can Joe Biden win? At this stage it looks unlikely. And if he keeps insisting he will run, then Democratic coffers are going to suffer as supporters withhold donations. This could mean lack of advertising in down-ballot races which is, to put it mildly, Not Good.

But what Democratic nominee at this late stage could win? A short list might include Kamala Harris, Gavin Newsom, Gretchen Whitmer, Pete Buttigieg, and Andy Beshear. My utterly amateurish and shoot-from-the-hip opinion? None of them could win at this late stage—there simply isn’t time to build both name recognition and support. Unless, that is, they were running as an incumbent. In other words, Biden needs to resign or be removed as President, and, per the 25th Amendment, and with Biden’s full and public support, let Harris assume the presidency.

[And ha! I just went searching for a link for ’25th Amendment’ and came across this New Yorker article—so I’m not the only one thinking this way. But screw it, I think it’s a cool idea, so I think I’ll publish this anyway. I’ll just do it right now, today, instead of tomorrow as planned.]

Then there would be four months for the voters to see Harris as President. During which time every other Democrat on the planet could extoll the administration’s very many—and, seriously, there are many—achievements, to which—as the New Yorker also points out—Harris can lay claim. I have zero doubt Kamala Harris would make a good President; my doubts are all about her ‘electability’, that is, the perception of whether she would make a good president. As sitting President she would simply glide past that “But could she do the job?” whingeing: she would be doing the job for all to see—and doing so with the kind of sharp energy we haven’t seen since Obama was President.

So, yep, with the temporary power to bend minds I’d focus mine on Biden, Harris, and the Cabinet and get them to agree that Good Ol’ Joe has a grave and incurable condition that renders him unable to perform his duties. Something like, say, hélikia astheneia2 or, if you prefer, senectutis infirmitas. Harris would become President, nominate a Vice-President (and, oh, that’s a whole other blog post!), and the machine could move smoothly into full gear. Then we could all get on with making sure we don’t lose what might be our last chance to save democracy in the United States.

And all that these weather events reinforce: the increasing rate of climate change, immigration, global instability, famine… ︎Yes, it’s tautological, but the bigger and more complicated a medical term sounds the more inarguable it feels.

︎Yes, it’s tautological, but the bigger and more complicated a medical term sounds the more inarguable it feels.  ︎

︎

July 2, 2024

The Supreme Right of Kings

The Supreme Court just turned the President into a monarch. Not even a constitutional monarch but an absolute monarch. A monarch not subject to the law.

When one cannot be prosecuted for something—anything—committed while in office, the Constitution becomes not worth the parchment it’s written on.

This ruling is the worst ruling I know of. I cannot imagine anything more likely to destroy democracy in the United States.

To quote the Guardian:

In her dissent, the justice Sonia Sotomayor listed some of the things that the president can now do without consequence, according to the majority. “Orders the Navy’s Seal Team 6 to assassinate a political rival? Immune,” she writes. “Organizes a military coup to hold onto power? Immune. Take a bribe in exchange for a pardon? Immune. Immune, immune, immune … The relationship between the president and the people he serves has shifted irrevocably. In every use of official power, the president is now a kind above the law.

Sotomayor’s dissent is among the most alarmed and mournful pieces of legal writing I have ever read. She concludes it: “With fear for our democracy, I dissent.”

The President is now a king. I fear for the world. I do not exaggerate.

June 29, 2024

Shouting at Magazines

A few weeks ago I read a question posed in an article in Current Archaeology that made me shout at the magazine: If you’d read Hild you’d know that!1 Fortunately, the perspicacious Kate Macdonald responded for me. Seeing Hild (and Gwladus!) and Menewood finally make it into my favourite archaeology magazine? A lovely start to the weekend!

The original paper on which the CA article on Early Medieval women’s mobility was based can be read here.

The original paper on which the CA article on Early Medieval women’s mobility was based can be read here.  ︎

︎

June 28, 2024

George Heals

How it started…

How it started… …how it’s going

…how it’s goingImage description: Left—A tabby cat asleep on a lap, showing a shaved leg with a long wound, mostly healed to a thin scar but with two stitches and one scabbed over place where he tore out a couple of stitches. Right—Tabby cat snoozes on a blue blanket showing the ruff of full fur around his foot and the just-growing-back fur of the rest of his leg.

George, as you recall, tangled with something bigger than himself and came off a poor second. Two weeks later here he is, all healed, the fur growing back on his leg, snoozing away the day, warm and snug while the Seattle summer ( ) throws more rain…

) throws more rain…

It’s been an odd spring and summer so far. Fingers crossed that the sun comes out to play once and for all—as it so often does here in Seattle—after July 4th.

June 26, 2024

A Miracle Built on a Moment: a 36-year love story in photos

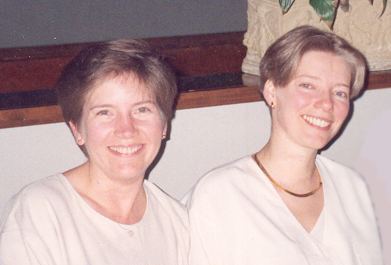

36 years ago today I met Kelley. 36 years ago today I fell instantly and irrevocably in love. Most people find that difficult to believe. I understand. I’ll say only that if you ever have every cell in your body stop, shiver, and align in one direction like iron filings around a magnet, you will know. It remains the oddest, most powerful and inarguable thing that’s ever happened to me. A done deal, the work of a moment. And absolutely non-negotiable.

36 years later, here we are, living the life that bloomed from that moment. Every day is a miracle.

Does this mean our life together was inevitable and easy? It was not. Against that simple, visceral knowing was ranged every rational, practical and institutional argument in the world.1 So although the connection, commitment, and (so far) life-long bond happened in an instant, it took 18 months to make it possible for me to move from the UK to Kelley in the US, and another 5 years of browbeating the world to make the US State Department declare it to be in the National Interest to grant me, an out lesbian with no money, connections, degree, or job offer, but with a chronic degenerative illness and no visible means of support, a waiver to live permanently in this country.2

36 Years: A PhotostorySix years ago, on our 30th anniversary, I amused myself by putting together a photo story. I thought it was time for an update.

I met Kelley in the corridor of a dorm at MSU in East Lansing, Michigan. It was 104º with no air-conditioning. We were there for Clarion—I was their very first foreign student. I’ve told the story elsewhere. But the bottom line was: we had six weeks together and then I had to go back to my life—family, partner, job, mortgage—in the UK with no practical hope of coming back…

While we were apart. Kelley went to parties

While we were apart. Kelley went to parties I worked every hour the universe sent teaching to earn $$

I worked every hour the universe sent teaching to earn $$That autumn we were apart, in 1988, was very, very hard. Kelley was working at GE Computer Services, going to parties, and making friends in the Atlanta queer community. In Hull, I was grief-stricken (my little sister died), stressed out of my mind (in love with two women on opposite sides of the Atlantic), and frantically earning money to get back to the US. As well as my actual job as a caseworker at a street-drugs agency (basically doing social work for people using heroin and meth), I was teaching women’s self defence as many evenings and weekends as I could. I hadn’t really started to get sick yet…

1989—what is love without a cat?

1989—what is love without a cat?Then I did get sick. And I lost weight. But then, finally, I managed to get back to Kelley. I’m not sure we let go of each other for more than 5 minutes at a time the whole seven weeks I was in the US. This Polaroid was taken in Tampa, where Kelley introduced me to her mother and stepfather.

This time when I left her it was to return to the UK one last time, sell my house, leave my partner of 10 years, and say goodbye to my family. It took three months. It was hard.

We lived in a brand new apartment way outside Atlanta: Duluth, Georgia. Then moved closer into the city with a rented house in Decatur. Finally, with the advance I got from Ammonite, we had just enough to put down a scarily skimpy deposit and risk an adjustable rate mortgage on a little house in Atlanta itself. At some point I would either sort immigration and we’d move somewhere not so damned hot, or the immigration thing would completely implode and we’d have to leave the country. Either way, we’d be selling before the interest rate jumped too much. It was worth the risk. But money was tight, immigration was daunting, and my mysterious fatigue was not getting better.

Stressed and tired we find refuge in each other. Photo by Mark Tiedemann.

Stressed and tired we find refuge in each other. Photo by Mark Tiedemann.In this photo, taken in 1992, the strain is showing. We were seeing lawyer after lawyer and not getting the immigration answers we needed. I was having medical test after medical test, ditto. We knew it was serious when I began to limp. Six months later, I had my diagnosis: MS.

Six months after that, we got married. I wore long sleeves because of all the IV bruises on my arms. But I was so happy that day. I don’t think we let go of each other at all except to hug other people. It was a home-made wedding; the whole thing, excluding the rings, cost $500.

I started to let my hair grow

I started to let my hair growAlthough the marriage had zero legal force it had a profound effect on me. Weirdly, that manifested in me beginning to grow my hair. (Something about being settled? Being a wife? It’s a mystery.)

Now we play grownup, or maybe dress-up: Southern Ladies Who Lunch

Now we play grownup, or maybe dress-up: Southern Ladies Who LunchAnyway, by the next spring it was long enough to spray and pin into an up-do for a big ol’ Southern party at my editor’s father’s house: everyone who was anyone in Atlanta society was there. It was like playing dress-up. It was playing dress up.

Then I sold another book (Slow River). I got my Green Card. And we moved to Seattle.

1997 outside a friend’s house in Seattle

1997 outside a friend’s house in Seattle1997. Seattle. We are much more at home. Kelley has a fab job at Wizards of the Coast and I’ve published two novels and sold a third (The Blue Place). We have a lovely little house in Wallingford (that’s a friend’s house in the background). We’re bursting with happiness. One fly in the ointment: my hair. It’s long enough to plait, very heavy and very annoying. Here it’s scragged out of the way; I am sick of it.

1999, Monteplier VT

1999, Monteplier VT 2000, Queens Grill, Queen Elizabeth II

2000, Queens Grill, Queen Elizabeth II1999. Vermont. I’ve started to shorten my hair. One year later, in 2000, I’ve chopped it all off and bleached it white. This is us in the Queen’s Grill onboard QE2: a transatlantic crossing that was our 40th birthday present to ourselves. We’re both wearing long dresses because they take First Class seriously on that boat. (Next time: a tux! At the time I didn’t know anywhere I could get one.)

About to dance the Freedom Fandango

About to dance the Freedom Fandango 2002 at the PKD Awards

2002 at the PKD Awards2000 was a big year. My MS was increasing upon me and Kelley cashed in her stock options. Life was uncertain. We had no idea how many years of good life I, and so we, had left. Live life now, is what we decided. Kelley quit her job and we threw an enormous party—rented out a whole nightclub in Pioneer Square—called it the Freedom Fandango, and invited everyone we knew.

I underwent an experimental course of chemo. Felt brilliant. Felt terrible. Then stabilised. The second photo was taken after I’d stabilised again: me and Kelley at the PK Dick Awards with our friends Mark and Donna. I was there to support Mark, who was nominated, and to accept the award for Steve Baxter if he won—which he did. I was about to publish the second Aud novel, Stay. Kelley was about to publish her brilliant novel Solitaire .

‘Stabilised’ is always a relative term when it comes to MS. It’s actually a course of endless decline. By 2004 it was clear we would have to leave our beloved house-with-all-the-steps in Wallingford and find something more accessible. So here in 2005 is one last shot of Kelley making hummus in the kitchen of our old house. One of me in the kitchen of our new single-level house a month later in Broadview. Kelley has published Solitaire and just started the longest-ever negotiation for the movie rights. I’m working on Always.

Los Angeles: Lammy #6

Los Angeles: Lammy #6 We were up late...

We were up late... Celebrating 20 years

Celebrating 20 yearsMay 2008 in Los Angeles: winning my sixth Lambda Literary Award (for And Now We Are Going to Have a Party). Then the day after in the bar feeling a leetle rough. Then June in Seattle: a dinner party at home to celebrate our 20th anniversary. I am about to start writing Hild. Kelley is writing the screenplay for OtherLife.

These are all taken between 2009 and 2012. The black and white one by Jennifer Durham is me being delirious with delight at getting an offer from FSG for Hild.

2013. General happiness, and then, a few months later, a fully legal wedding on the 20th anniversary of our first nothing-legal wedding. All these photos by Jennifer Durham, too.

2013, as co-Guests of Honour at Westercon.

2013, as co-Guests of Honour at Westercon.In 2013 Kelley and I were co-Guests of Honour at Westercon. It was fabulous. We turned it into a mini Clarion reunion and had a splendid time. All that year, and the next, we travelled: a US hardcover tour for Hild, then a UK tour, then a US paperback tour, culminating in Washington DC for Kelley’s father’s 80th birthday.

In 2015 and 2016 I found myself in the news, a lot. In 2015 it was the unexpected whirlwind around the Literary Bias data I put together. In 2016 it was the even more unexpected resurrection of Anita Corbin’s Visible Girls series and then Visible Girls Revisited. It’s pretty weird being recognised for a random moment 43 years ago.

By this time I’d transitioned to using a wheelchair. I was ill and tired. Kelley was working staggering hours as a freelancer. We were dealing with a Lot of Family Stuff. This photo was taken by Anita for the new series; I don’t like the photo, perhaps because I feel as though I look heavy. (I’m not talking about physical weight but emotional weight.) And I was unhappy about the wheelchair. It’s hard to explain: I’m not unhappy about using a wheelchair—the wheelchair has given me a kind of freedom I had lost. I was unhappy about being posed with the wheelchair. It felt…weird. Sort of fetishistic. In fact I’ve cropped this photo because in the original the chair became the focal point.

2019. © Anita Corbin as part of the Visible Girls Revisited series..

2019. © Anita Corbin as part of the Visible Girls Revisited series..Then it was the pandemic, and we went nowhere and took only endless photos of experiments with home hair cuts.

Then, woo-hoo, we started going to conventions again—specifically ICFA. Here we are in 2022 and 2023, loving the sun and the company.

2022. Blurry photo by the pool

2022. Blurry photo by the pool 2023. A less blurry photo on the other side of the pool

2023. A less blurry photo on the other side of the poolSpear won awards and nominated for a bazillon more, and Menewood came out. And here we are at the World Fantasy Convention last year.

Nov 2023, WFC. We’re in the bar—shocking, I know—I’m off camera to the left

Nov 2023, WFC. We’re in the bar—shocking, I know—I’m off camera to the left Nov 2023, WFC. We’re in the mass signing—Kelley’s off camera to the right

Nov 2023, WFC. We’re in the mass signing—Kelley’s off camera to the rightAnd here we are just two weeks ago at the same event—Kelley at the pre-game wine-and-nibbles (I was doing the meet-and-greet with board members and donors at the other end of the room) and me on the stage an hour later. 3

Kelley listening to friends talk while I sing for my supper at the other end of the room

Kelley listening to friends talk while I sing for my supper at the other end of the room Me on stage getting intense about queerness in the Early Medieval while Kelley watches from the audience

Me on stage getting intense about queerness in the Early Medieval while Kelley watches from the audienceWe’re both tired. We’ve been through a lot of external stresses the last couple of years.4 But as you can see between the photos of late last year and this summer we’re beginning to get a lot of that sorted and the strain is easing. And, as always, we find our refuge each in the other—and the strength inside ourselves to be strong for the other when they can’t.

Kelley is the finest person in the world. I fell in love with her in a moment but have spent my life since then trying to be the person she deserves. I might never get there but it continues to be an amazing journey.

Little things like reason—everyone, even Kelley to begin with, thought I was, well, perhaps ‘not sensible’ is the kindest way to phrase it—family, my partner, friends, jobs, money, health, immigration law… ︎And thereby create new immigration law.

︎And thereby create new immigration law.  ︎So many photos these days seem to be taken at events where for one reason or another we can’t sit, as we prefer, right next to each other. We really, really have to fix that!

︎So many photos these days seem to be taken at events where for one reason or another we can’t sit, as we prefer, right next to each other. We really, really have to fix that!  ︎I wrote about that here and here.

︎I wrote about that here and here.  ︎

︎

June 25, 2024

Photos of the Queer Medieval

I promised photos of the Queer Medieval event for Pride at Town Hall Seattle, sponsored by Humanities WA. And here they are. All photos by Libby Lewis.

lt’s always cool seeing one’s name on a big ol’ board

lt’s always cool seeing one’s name on a big ol’ board Bookselling b the fabulous Charlie and Colleen of Charlie’s Queer Books

Bookselling b the fabulous Charlie and Colleen of Charlie’s Queer Books The folks who made it all happen: Sarah, Maria, and Julie

The folks who made it all happen: Sarah, Maria, and Julie Mega Cavell supplied the fabulous Old English riddle games and illustrations

Mega Cavell supplied the fabulous Old English riddle games and illustrations It’s a big stage, and the lights are bright…

It’s a big stage, and the lights are bright… We sold over 500 tickets

We sold over 500 tickets After Maria’s lovely intro I spoke for about 45 minutes

After Maria’s lovely intro I spoke for about 45 minutes I couldn’t see the audience—I could have been speaking to an empty hall for I know—so I’m glad of these pictures

I couldn’t see the audience—I could have been speaking to an empty hall for I know—so I’m glad of these pictures Maybe it’s time I bought some brightly -coloured clothes…

Maybe it’s time I bought some brightly -coloured clothes… Clearly people were engaged—but they were quiet, so, again, I couldn’t tell…

Clearly people were engaged—but they were quiet, so, again, I couldn’t tell… So I was encouraged when people started to laugh

So I was encouraged when people started to laugh Then lots of applause when the keynote was done

Then lots of applause when the keynote was done then it was time for a serious question or two from Maria

then it was time for a serious question or two from Maria And again people were quiet

And again people were quiet But by then I was excited

But by then I was excited And the audience was too

And the audience was too I demonstrate how hard it is to not Say The Swears

I demonstrate how hard it is to not Say The Swears And now I’m rocking and rolling

And now I’m rocking and rolling And the audience—including my sweetie—is appreciative

And the audience—including my sweetie—is appreciative I forget which question this was a response to

I forget which question this was a response to But by now I knew the audience was there :)

But by now I knew the audience was there :)If you want to watch the video, you can see it here.