Nicola Griffith's Blog, page 15

September 15, 2024

Ammonite on sale $1.99—one day only!

One-day only sale of Ammonite

One-day only sale of AmmoniteAmmonite was my first novel. (Read all about it here.) Curious about why I’ve been inducted into the SFF Hall of Fame? About why this little mass market paperback original was named #25 on Esquire‘s Best Science Fiction of All Time? (“Gripping and gutsy, rich in layers of feminist and queer thought, Ammonite gleefully throws a stick of dynamite into the sci-fi firmament.”) This is where it all began. And here’s your chance to try it for just $1.99—today only. All US platforms:

September 10, 2024

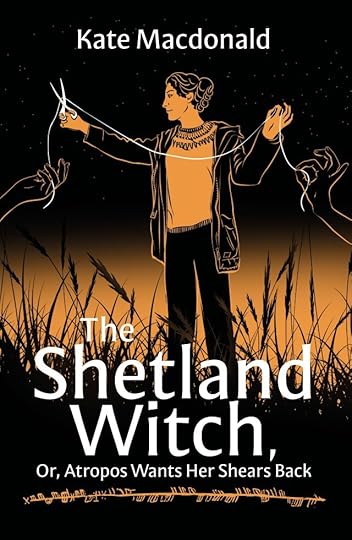

The Shetland Witch

The Shetland Witch and Stories from the Shetland Witch (The Peachfield Press, out now).

Kate Macdonald is a literary historian, editor, critic, and good friend who helped me with (very!) last minute edits to Menewood. She founded and for several years ran Handheld Press—a wonderful small press focused on selling stories mostly, but not wholly, by women from (often, but not always) the early 20th century that are unfairly out of print: fiction and nonfiction ranging from thrillers to women’s weird to biography to fantasy to disability to queer fiction. These are great books: Sylvia Townsend Warner, John Buchan, Rose Macauley, Vonda McIntyre… Handheld also briefly experimented with new fiction—including my own So Lucky—but found that wasn’t really their strong suit, so went back to focusing on the wonderful classics that deserve new audiences.

In 2019 Kate began writing a short story about witches in Shetland. To quote her: “It grew. She got an agent. The agent spent two years pitching The Shetland Witch, but these were the immediate post-Covid years when the publishing industry was swamped with everyone else’s novels written during the pandemic. In autumn 2023 Kate began serialising The Shetland Witch on Substack. In early 2024 she began serialising the two Shetland Witch novellas, In Achaea and Mrs Sinclair and the Haa, to her paying subscribers. Her subscriber numbers rocketed. The time had come to go to print.”

The Shetland Witch, and Stories from The Shetland Witch, both published yesterday as an ebook, paperback and hardcover. In the UK, order here, and here in the US. And also from Peachfield Press.

As Kate would say, “Come for the magic and the archaeology, stay for the mythic creatures and a malignant trow.”

September 6, 2024

Bird flu: It’s time to talk

I’ve been keeping an eye on the H5N1 bird flu situation for months, getting more and more frustrated at this country’s general indifference to its spread. I’m assuming most of my readers are perfectly capable of following the same news I do, so I haven’t bothered talking about it here. But now highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A (H5N1, ‘bird flu’) has been confirmed in 3 dairy cattle farms in California1—and it’s time to pay attention.

What’s changed?Why am I talking about this now? After all, it’s already in dairy herds in 13 other states.2 This is different. Here’s why:

California is the largest milk producer in the US. There are a ridiculous number of Californians who, despite all reason to the contrary, persist in consuming raw milk and raw milk products. Regular flu (H1N1, H3N2, and Flu B/Victoria) season is just around the corner.This combination of factors could change everything.

Why do these changes matter?Birds spread the virus between themselves via saliva, mucus and faeces. This is probably how it spread to cows—perhaps a sick grackle lands on the rail and poops into a feed trough. The main route of transmission between cows seems to be via their milk—or, rather, via contaminated milking equipment. The cows don’t get dangerously ill. But they shed the virus in their milk for quite a while after their symptoms abate.

Right now, bird flu seems to be transmitted to humans rarely, usually from backyard poultry shedding virus in their saliva, mucous, and faeces. More recently there have also been a handful of cases of dairy workers being infected by cows. Most of these people have mild illness—red eyes and runny noses—or no symptoms at all. None appear to have passed the virus directly to another person. Not too scary, right? But bear in mind these people are merely handling the equipment used to milk the cows. The milk they actually drink is pasteurised, which kills bacteria and viruses.

What would happen if you drank that raw infected milk? I don’t know. But most cats who drink it die quickly, and, in a recent study, six of the six ferrets deliberately infected with H5N1 cultured from a dairy cow died.

Back to all those raw milk, and raw milk product-consuming Californians. They may not die, they may not even become terribly ill, but they will be infected. And with regular flu season almost upon us, the odds of people being infected by both H5N1 and, say, H1N1, H3N2, or Flu B/Victoria—all of which are easily transmissible between people—go way, way up.

When two influenza virus simultaneously occupy the same host, they tend to swap genetic material; mutation will eventually occur—sometimes a dramatic shift. Add to that the fact that the current H5N1 strain is already mutating in several ways associated with viral virulence and host specificity shifts, and the chances of a new, highly transmissible, highly virulent, highly pathogenic strain of flu increase drastically.

What should you do?Well, don’t panic; we’re not nearly at that point.3 Currently, the odds of any one of us getting bird flu are low. But here are some things I might consider doing:

Pay increased attention to the cats: cats can get bird flu from infected birds. If your cat is a chaser of our feathered friends make sure you either keep them indoors or, if that’s not really an option, make sure that if they catch a bird you take it away from them ASAP. And make sure that you wear gloves and a respirator to do so; that you then obsessively clean everything; and then that you watch the cat for any signs of illness and, if it develops respiratory distress, put on your mask and take it to the vet. (And warn the vet to wear a mask.) Take precautions out in the world: wear a good mask indoors (at least a KN95; an N95 respirator is better4) and in crowds outdoors (as you should be doing anyway). As we also have a lot of specific viral receptors in our eyes, you might want to think about goggles—or at least wearing glasses even if you might normally take them off if you’re not reading.Don’t eat raw milk or raw milk products. Ever. But especially not now. I don’t even eat eggs that aren’t dry-scrambled or hard-boiled, and I’ll be wary of homemade aioli for a while.5Get your flu shot.Think about what what happened during the first two months of Covid and consider laying in a few sensible supplies—emphasis on a few, and sensible. Think in terms of items you’ll absolutely be using soon anyway in the general course of things, like soap and hand sanitiser, and tissues and toilet rolls and disinfectant, and delicious food like butter and chicken that freeze well, and cheese that keeps a while and that you’ll enjoy anytime.6My hope—however unrealistically optimistic this is in context of the US medical and regulatory bureaucracy’s usual response—is that bodies such as the CDC and USDA and various state governments start taking this seriously: mandating the testing and quarantining of dairy herds (and very possibly beef cattle—but that’s a post for another day); manufacturing the appropriate vaccines and antivirals for both cows and people; and, at the very least, start vaccinating front-line dairy workers (as they very sensibly are already doing in Finland).

Just because a new, deadly pandemic could happen doesn’t mean it will. But just to be very clear, H5N1 avian flu can be and more than occasionally is fatal to humans. The WHO just shared more news about a young woman in Cambodia who died after food prep of an infected chicken—and the virus responsible was a novel reassortant of an older clade of H5N1 and the current clade.7 The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) has warned that this new reassortant is now circulating in chickens and ducks. It only takes a few mutations to turn any virus into something that can leap from person to person with the ease of a dancer. It mighut not yet be time to stay awake at night but, as always, it pays to stay informed.

Be sensible. Be safe.

Which I’m guessing means it’s actually present in many others. ︎That we know about. To me it’s very clear that it’s almost everywhere—farmers just aren’t testing because they don’t perceive it to be in their best interests.

︎That we know about. To me it’s very clear that it’s almost everywhere—farmers just aren’t testing because they don’t perceive it to be in their best interests.  ︎There again, it’s never a good time to panic. Panic never helped anyone with anything.

︎There again, it’s never a good time to panic. Panic never helped anyone with anything.  ︎See https://sph.umd.edu/news/study-shows-n95-masks-near-perfect-blocking-escape-airborne-covid-19

︎See https://sph.umd.edu/news/study-shows-n95-masks-near-perfect-blocking-escape-airborne-covid-19  ︎You know you don’t have to use egg in aioli, right?

︎You know you don’t have to use egg in aioli, right?  ︎Y’know, unless like me and can’t eat fermented diary and other high-histamine foods.

︎Y’know, unless like me and can’t eat fermented diary and other high-histamine foods.  ︎See WHO report: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2024-DON533

︎See WHO report: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2024-DON533  ︎

︎

September 4, 2024

Life, the universe, and everything

31 years ago today I married Kelley for the first time. It had no legal force. In fact, where we got married—in the back garden of our Atlanta home—being queer, doing queer, was actively illegal.1 Exactly 20 years later, we got married again, this time with the full might of the State of Washington and the United States of America behind us.2

Those double rings carry the weight and joy of 42 years of love. Kelley is my life, my universe, my everything.

11 years ago: The second wedding

11 years ago: The second wedding 31 years ago: The first weddingThe applicable law, Bowers vs Hardwick, was not reversed until 1998. I always called Kelley’s parents my outlaws, because they were witness to and did not attempt to prevent an illegal act.

31 years ago: The first weddingThe applicable law, Bowers vs Hardwick, was not reversed until 1998. I always called Kelley’s parents my outlaws, because they were witness to and did not attempt to prevent an illegal act.  ︎Because, as the best 25th anniversary present ever (this one the anniversary of the day we met), SCOTUS struck down DOMA.

︎Because, as the best 25th anniversary present ever (this one the anniversary of the day we met), SCOTUS struck down DOMA.  ︎

︎

August 29, 2024

Breaking Down Walls

Not long after I was inducted into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame I sat down with Will Taylor for an interview for the Museum of Popular Culture. We talked about all kinds of things: the title comes from my recent decision to start making a concerted effort to break down the walls between my various literary gardens, that is, to get rid of all these artifical genre labels so that readers of my SFF know about the Aud novels, readers of Aud know about Hild, and readers of Hild know about my SFF. (And my memoir. And edited anthologies. And essays. And short fiction…)

Here’s one small segment to whet your appetite.

Whose science fiction and fantasy work would you recommend for those who love yours? Who should be taking their place in the Hall of Fame next year?

I would like to see Suzy McKee Charnas in the Hall of Fame. She was a contemporary of Vonda McIntyre and Russ and Tiptree. She wrote the Holdfast Chronicles, and as a writer she was fearless, utterly unflinching. I’ve just written an introduction to a new edition of The Vampire Tapestry that I think will be out either the end of this year or beginning of next. Charnas completely changed vampire fiction. She also wrote the very first novel that I know of with no men in it at all. She was a great writer. And her influence . . . Think of her as the SF equivalent of the Velvet Underground. They might not have sold a lot of albums, but a huge percentage of people who bought one of those albums formed a band that did sell a lot. She’s like that—more influential than first appears. I think a lot of people owe quite a bit to Suzy Charnas.

For those who like my books, who else might they enjoy? I would say Kate Atkinson—also from Yorkshire, also with a science-fictional mind. And if you like the Hild books, or at least the Early Medieval north, then Maria Dahvana Headley’s Beowulf translation—it’s not like any other, more a thrillingly modern but capturing-the- essence interpretation of the original, as Christopher Logue’s All Day Permanent Red does with Homer. Elizabeth A. Lynn. Both her science fiction, like A Different Light, and fantasy, such as the Chronicles of Tornor. And Jo Walton, she has a wonderful range. Rivers Solomon is doing some very interesting things.

Breaking Down Walls, MoPOP, August 2024

July 27, 2024

Infectious agents *can* encourage parthenogenetic, all-female reproduction (score one for Ammonite!)

Two recent papers have explained how Wolbachia, a bacterium that infects parasitic wasps, ensures that most of the wasps’ offspring are parthenogenetically-inclined females. This pleases me very much because it means that maybe the virus on Jeep—the all-female planet of Ammonite1—could do what some of what I said it could do, in terms of enabling human parthenogenesis. I mean, okay, people aren’t wasps, and a virus is very different to a bacterium—but, hey, it’s now been established that infectious agents can so too encourage parthenogenetic reproduction! There’s proof of concept: an all-women planet could sustain itself! So, ha, this is where I dance around singing  Let a bug bite your eye—it’s a parasite, my!—that’s me laughing…

Let a bug bite your eye—it’s a parasite, my!—that’s me laughing… That is, laughing at all those who rolled their eyes at Ammonite and, in a get-this-turd-off-my-shoe tone, labelled it ‘science fantasy’. Amd, well, yes, okay, it absolutely is fantasy, in the sense that faster-than-light travel is fantasy—which makes 95% of all SF ever written fantasy—but, in other senses, no, it is fucking not. Chortle.

That is, laughing at all those who rolled their eyes at Ammonite and, in a get-this-turd-off-my-shoe tone, labelled it ‘science fantasy’. Amd, well, yes, okay, it absolutely is fantasy, in the sense that faster-than-light travel is fantasy—which makes 95% of all SF ever written fantasy—but, in other senses, no, it is fucking not. Chortle.

Anyway, I’ve linked to both papers so that those so inclined can read for themselves. If you don’t want to struggle through the whole papers I’ve pasted in the abstracts below—but life is short, so tl;dr: At some point in the Wolbachia bacterium’s distant past, long before it started focusing on parasitic wasps, it infected a different insect and from that beastie borrowed some genes that code for a protein that plays a key role in sex determination. When it infects the wasps that lay eggs in flies, the baby wasps that munch their way out of those flies tend to be overwhelmingly—100 to 1—females that can reproduce parthenogenetically. (I do recommend reading the second paper, if only because they provide a nifty graphical abstract as well as the written one. I wish more papers would do that.)

The first paper is “Identification of Parthenogenesis-Inducing Effector Proteins in Wolbachia” in Genome Biology and Evolution:

Bacteria in the genus Wolbachia have evolved numerous strategies to manipulate arthropod sex, including the conversion of would-be male offspring to asexually reproducing females. This so-called “parthenogenesis induction” phenotype can be found in a number of Wolbachia strains that infect arthropods with haplodiploid sex determination systems, including parasitoid wasps. Despite the discovery of microbe-mediated parthenogenesis more than 30 yr ago, the underlying genetic mechanisms have remained elusive. We used a suite of genomic, computational, and molecular tools to identify and characterize two proteins that are uniquely found in parthenogenesis-inducing Wolbachia and have strong signatures of host-associated bacterial effector proteins. These putative parthenogenesis-inducing proteins have structural homology to eukaryotic protein domains including nucleoporins, the key insect sex determining factor Transformer, and a eukaryotic-like serine–threonine kinase with leucine-rich repeats. Furthermore, these proteins significantly impact eukaryotic cell biology in the model Saccharomyces cerevisiae. We suggest that these proteins are parthenogenesis-inducing factors and our results indicate that this would be made possible by a novel mechanism of bacterial-host interaction

And the second is “Wolbachia symbionts control sex in a parasitoid wasp using a horizontally acquired gene” in Current Biology.

Host reproduction can be manipulated by bacterial symbionts in various ways. Parthenogenesis induction is the most effective type of reproduction manipulation by symbionts for their transmission. Insect sex is determined by regulation of doublesex (dsx) splicing through transformer2 (tra2) and transformer (tra) interaction. Although parthenogenesis induction by symbionts has been studied since the 1970s, its underlying molecular mechanism is unknown. Here we identify a Wolbachia parthenogenesis-induction feminization factor gene (piff) that targets sex-determining genes and causes female-producing parthenogenesis in the haplodiploid parasitoid Encarsia formosa. We found that Wolbachia elimination repressed expression of female-specific dsx and enhanced expression of male-specific dsx, which led to the production of wasp haploid male offspring. Furthermore, we found that E. formosa tra is truncated and non-functional, and Wolbachia has a functional tra homolog, termed piff, with an insect origin. Wolbachia PIFF can colocalize and interact with wasp TRA2. Moreover, Wolbachia piff has coordinated expression with tra2 and dsx of E. formosa. Our results demonstrate the bacterial symbiont Wolbachia has acquired an insect gene to manipulate the host sex determination cascade and induce parthenogenesis in wasps. This study reveals insect-to-bacteria horizontal gene transfer drives the evolution of animal sex determination systems, elucidating a striking mechanism of insect-microbe symbiosis.

Enjoy!

Recently named #25 on Esquire‘s 75 Best Sci-Fi Novels of All Time. No, I will never get tired of saying that. ︎

︎

July 26, 2024

Identity and SF

Yesterday I announced I was a 2024 Inductee into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame—and how astonished I was by that. Why the astonishment? Because while I’m absolutely a native of SF, and the only writing workshop I’ve ever attended was Clarion, most recently I’ve been better known for writing novels that aren’t SFF in the classic sense—though, as I’ve argued elsewhere, they are speculative fiction. So what works have I authored that are inarguably SFF?

I’ve written two SF novels, Ammonite and Slow River; one Arthurian fantasy novel, Spear; and one contemporary disability-with-monsters short novel, So Lucky. I’ve edited three anthologies in the Bending the Landscape series: BtL: Fantasy, BtL: Science Fiction, and BtL: Horror. And every single piece of shorter fiction I’ve ever published has been SFF, from my first, “Mirrors and Burnstone” (the prequel to Ammonite), to the Warhammer work-for-hire stuff I did in 1989 and 1990, to the two most recent, “Glimmer” and “Cold Wind.” (I’m not really known for my shorter fiction and don’t write a lot of it but most of it has been shortlisted for SFF awards of some variety or other1 and/or been reprinted in Year’s Best anthologies. And in case you’re wondering, no, it’s never been collected. And, yes, I have more than enough for a collection, and yes, I’d like to publish a collection; I’ve just never quite got around to it.)

I love science fiction (and fantasy and speculative fiction of every flavour); it lies at the core of my writing career. I have never for a minute tried to ‘walk away from SF’ or ‘transcend SF’ (the very idea pisses me off—SF does not need ‘transcending’). SF people are my people. In honour of the honour of being a 2024 inductee into the SFF Hall of Fame, then, here’s an essay I wrote a while ago about why SFF matters to me.2

Identity and SF: Story as Science and FictionScientific theory and fiction are both narrative, stories we tell to make sense of the world. Whether we’re talking equation or plot, the story is orderly and elegant and leads to a definite conclusion. Both can be terribly exciting. Both can change our lives.

I was nine was I realised I wanted to be a white-coated scientist who saved the world. I was nine when I read my first science fiction novel. I don’t think this is a coincidence, though it took me a long time to understand that.

For one thing, I had no idea that the book I’d just read, The Colors of Space, an American paperback, was science fiction: I had no idea that people divided books into something called genres. In my world, there were two kinds of books: ones I could reach on the library shelves, and ones I couldn’t. My reading was utterly indiscriminate. For example, another book I read at nine was Gibbon’s History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, dragged home volume by volume. (Obviously, at nine, much of it went over my head but it fascinated me nonetheless.) But my hands-down favourite at that time wasn’t a library book, it was an encyclopaedia sampler.

When my parents were first married, my father, to make ends meet (they had five children in rapid succession), sold encyclopaediae door-to-door at the weekends. Long after he’d stopped having to do that, he kept the sampler. I loved that book. Bound in black leather, it had gold-edged pages and the most fabulous articles and illustrations—artists’ impressions of the moon or Mars or a black hole. It was state-of-the-art 1950s, samples of articles on everything from pastry to particle physics. I would read that book on Saturday mornings, lying on my stomach on my bedroom carpet. Those pages were my Aladdin’s Cave. I read entirely at random. Looking back, probably the thing that hooked me irrevocably was that almost every article was incomplete: they finished mid-paragraph, often mid-sentence. I knew, reading that black sampler, that there was more, that the story always continued, out there somewhere, in the big wide world.

One Saturday morning when I was nine, I read the most gobsmacking thing of my life: everything in the world was built of something called atoms. They were tiny and invisible and made mainly of nothing. If you could crush all the nothing out of the Empire State Building, it would be the size of a cherry stone but weigh…well, whatever the empire state building weighs. I clapped the book shut, astonished, leapt to my feet and thundered downstairs. In the kitchen, where my mother was cooking a big fried breakfast for seven, I announced my incredible discovery. She said, “How interesting. Pass the eggs.” I blinked. “But Mum! Atoms! The Empire State Building! A cherry stone!” And she said, again (probably with a bit of an edge), “Yes. Very interesting. Pass the eggs.” So I passed the eggs, and wondered briefly if my mother might be an alien. (Unlike many of my other friends it never occurred to me to wonder if I might be adopted: too many sisters with features just like mine. Understanding of some of the laws of genetics was inescapable.)

I spent the rest of that weekend in a daze, resting my hand on the yellow formica of the kitchen table while everyone ate their bacon and eggs, wondering why my hand didn’t melt into the table. They were both mainly nothing, after all. What else in the world wasn’t what it seemed? What other wonders were waiting for me to stumble over them?

About a month later, I was helping my mother clean the local church hall where she ran a nursery school during the week, and under a bench I found a book with a lurid red and yellow cover: The Colors of Space. (Until two weeks ago, I didn’t know the author was Marion Zimmer Bradley. I could easily have found out anytime in the last few years, but I didn’t. Not checking on memory is one of my superstitious behaviours. I also don’t take photos of special occasions or keep a journal. I don’t like freezing things in place. I prefer fluidity, possibility. However, before I sat down to write this essay, I went to Amazon, looked up the book, and ordered it. When it arrived, I was delighted by the lurid red and yellow cover, then amused when I realised it explained something that puzzled my friends a dozen years ago. My first novel, Ammonite, was published in 1993. The first edition had a truly cheesy red and yellow cover with a spaceship front and centre. No one could understand why I wasn’t upset but, clearly, I was drawing fond associations with my nine year-old self, remembering another ugly paperback. When I’ve finished writing this, I’ll re-read it…)

I don’t remember a thing about the story or the characters, only that it was about aliens (aha, I thought, imagining my mum) and the discovery of a new colour. That night, lying in bed, I nearly burst my brain trying to imagine a new colour, just as in my teens I would drive myself to the brink of insanity (not so hard, really, when a teenager) trying to imagine infinity.

At some point we moved to a new house—we were always moving—and the black leather encyclopaedia sampler disappeared. By this time I had discovered Asimov and Frank Herbert and a collection of ’50s SF anthologies with introductions that banged on the SF drum and introduced me to the notion of genre. I was hooked. Through these stories, far more than through any school lessons, science came alive for me: surface tension (Blish’s “Surface Tension”), ecology (Herbert’s Dune), multi-dimensions (Heinlein’s “And He Built a Crooked House”), politics (just about anything by Asimov). Science became my religion. I stopped day-dreaming about taking gold in the Olympics and started thinking about changing the world. I didn’t fret over minor details such as which discipline to choose—who cared whether it was physics or chemistry or maths or biology that ended up saving humanity?

That was the beauty of being twelve, and then thirteen. I didn’t have to deal with reality. I didn’t have to ignore with scorn the messy inexactness of zoology in order to devote myself to the purity of maths or to the measurability of chemistry. Watching a bird, considering Newton’s laws, learning about the tides of history seemed equally important. I wanted it all. The world sparkled. Einstein’s photoelectric effect, a spoof proving one equals two, Popper’s swans and Pavlov’s dogs: I fell in love with each in turn, depending on what class I was in. (Funnily enough, I never much liked any of my science teachers; they never liked me, either.) I tried on future identities: discovering an anti-grav drive; feeding all those starving children in fly-buzzed parts of the world; finally pinpointing the location of Atlantis.

At the same time, I was busy being a teenager. I tried on here-and-now identities: short hair or long? Hippie or punk? Beat poet in black or sweet-faced thing in pastels? Judas Priest or David Bowie? Monty Python or Star Trek?

An American SF editor, David Hartwell, has said that the golden age of SF is twelve. He has a point. The essence of being twelve, and of science fiction, is potential. They are both all about hopes and dreams and possibilities, intense curiosity aroused by the knowledge that there’s so much out there yet to be known. As we get older and do fewer things, and fewer things for the first time, that sense of potential diminishes. The open door starts to close—just like the anterior fontanelle of an infant’s skull.

Reading good fiction, particularly good SF, keeps the adolescent sense of possibility jacked wide open. A sense of possibility maintains plasticity, it keeps us able to see what’s out there. Without this sense of possibility, we see only what we expect.

Someone who runs on the same beach at dawn every day for two years gets used to certain things: being alone, the hiss and suck of the waves, the boulder that juts from the rock pool at the point where she leaps the rill, the cry of the gulls, the smell of seaweed, all in tones of grey and blue. So there you are one morning, running along, cruising on autopilot, using the non-slippery part of the boulder to give you a boost as you jump over the rill, listening unconsciously to the gulls squabbling over something at the water line. You’re thinking about breakfast, or the sex you had last night; you’re humming that music everyone’s been listening to the last week; you’re wrestling with some knotty problem for which you have the glimmerings of a solution. There’s a dead body on the beach. You run right past it: you literally don’t see it.

It’s counterintuitive, but it happens all the time: the white-faced driver staring at the tricycle crushed under his front wheel, “I just didn’t see him, officer.” The microbiologist who skips past the Petri dish in a batch of sixty cultures with that curiously empty ring, that lack of growth, in the centre. The homeowner who returns to his condo and doesn’t see the broken window, the muddy footprints leading to the closet and the suitcase full of valuables lying open on the bed. Every day, during our various routines, the movie of what we expect plays on the back of our eyelids while our brain goes on holiday. How many times do we got out of the car at the office and realise we don’t remember a thing about the journey?

Reading SF, the over-riding value of which is the new, keeps our reticular activating systems primed: we expect everything and anything. And if we expect, we can see. If we see, we try find an explanation. We form a hypothesis. We test it. We learn. We tell a story.

A science fiction story not only excites us about the world, it excites us about ourselves, how we fit within the systems that govern our universe, and excites us, paradoxically, about our potential to change the world. The best SF is, in a sense, about love: loving the world and our place within it so much that we make the effort to make a difference. But science fiction changes more than the world, changes more than our place in the world; it changes us. Science fiction has changed the discourse on what it means to be human. It introduced us to the notion that the nature of body and mind are mutable through tall tales of human cloning, prosthetics, genetic engineering. What would people look like today without prosthetics (contact lenses, artificial hips and knees, pacemakers and stents, dentures), cosmetic surgery, gene therapy? The more we change our story of ourselves, the more we change.

Which brings me full circle to the idea of fixing memory. I don’t like taking photographs or keeping a journal because, on some level, it stops me learning about myself. If I freeze an image permanently, I can’t revisit it and recast it, I can’t retell the story. I believe in story. Without it we don’t learn, we don’t grow, we don’t re-examine what is known to be known. I believe in science fiction stories, I believe in scientific theories. I read a novel about the fragility of the Y chromosome, or a text on the myth and mystery of the constant, phi, and both make me stop and think: Oh. My. God. Each blows me away, puts a shimmer around my day and lightens my step—and urges me to turn an eager face to the possibilities of tomorrow.

Everything from the Hugo to the Nebula to the Locus to the Tiptree/Otherwise to the BSFA… ︎SciFi in the Mind’s Eye (ed. Margret Grebowitz, Open Court, 2007)

︎SciFi in the Mind’s Eye (ed. Margret Grebowitz, Open Court, 2007)  ︎

︎

July 25, 2024

2024 Inductee to the SFF Hall of Fame

I am being inducted into the Museum of Popular Culture’s Science Fiction + Fantasy Hall of Fame. (The other 2024 Creator Inductee is Nnedi Okorafor.) When I found out I blinked. Blinked again, a bit dazed. Then, as it sank in, I started alternately grinning and blinking, thinking Yay! and What?

I am a native of sf, but not a resident.

— William Gibson, acceptance speech at MoPOP, Seattle, 2008

This is something William Gibson said at his 2008 induction into SFFHO.1 It encapsulates beautifully how I feel: I may no longer be a full-time resident of SFF but I am a citizen: I go back to the Auld Country fairly regularly; the vocabulary and grammar of SF are my first language; and my passport is current. Still, I am amazed to be invited to join the grandees in the Hall of Fame. I mean, go look at that list!

There is nothing in the world to compare to the feeling of being honoured by peers, part of something—belonging. I feel great! You can’t see me as I type this but believe me when I say: I am still grinning my head off. And I am grateful. Thank you.

I’m sure I’ll have more to say in a day or two. Meanwhile, here’s the press release.

I had the story from an attendee at the ceremony.

Seattle Author Nicola Griffith Inducted into Science Fiction & Fantasy Hall of Fame at MoPOPThe celebrated speculative fiction author and disability activist becomes the third local creator to be honored since MoPOP became steward of the Hall of Fame exactly twenty years ago.

SEATTLE, WA. (July 25, 2024) – Seattle-based speculative fiction author and activist Nicola Griffith (Hild; So Lucky) is being inducted into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame at Seattle’s Museum of Pop Culture.

Griffith joins Nnedi Okorafor, bestselling Nigerian American writer of Africanfuturist science fiction and fantasy, as one of two annual inductees in the “Creator” category for the class of 2024.

Founded in 1996, the Hall of Fame was relocated from the Gunn Center for the Study of Science Fiction at the University of Kansas to its permanent home at MoPOP in 2004. Inductees are nominated by the public, and a panel of professionals selects the final four annual inductees—two creators and two creations.

Each addition to the Hall of Fame reshapes the whole, providing fresh inspiration and lived experience and furthering MoPOP’s mission to ensure the full scope of science fiction and fantasy is honored.

Griffith’s first novel, Ammonite, was just named #25 on Esquire’s “75 Best Sci-Fi Books of All Time” list, and her Pride Month talk The Queer Medieval drew a crowd of hundreds to Town Hall Seattle on June 11, 2024.

The two previous Seattle-area inductees to the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame are Dreamsnake author Vonda McIntyre (2018) and Arrival author Ted Chiang (2020).

About Nicola Griffith

Nicola Griffith is a British American speculative fiction writer and activist. Author of the Hild Sequence, Ammonite, So Lucky, Slow River, Spear, and more, Nicola’s work has been awarded the Nebula Award, Otherwise/Tiptree Award, World Fantasy Award, Los Angeles Times Book Prize, two Washington State Book Awards, and six Lambda Literary Awards.

About MoPOP

The Museum of Pop Culture is a nonprofit museum in Seattle, Washington dedicated to contemporary pop culture. Founded by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen in 2000 as the Experience Music Project, MoPOP has showcased dozens of world-class exhibitions and offers extensive education and popular programming in music, film, gaming, and more.

The Museum of Pop Culture’s mission is to make creative expression a life-changing force by offering participatory experiences that inspire and connect our communities.

More About the Science Fiction & Fantasy Hall of Fame

︎

︎

July 21, 2024

Roll up your sleeves

No doubt you’ve already seen this:

Kamala Harris will make a kick-ass President—if we can get her elected. The Trump machine is already cranking; the Democratic Party need to get behind Harris fast and start drumming for votes.

So it’s time for us to stop whingeing and wondering and wishing, time to roll up our fucking sleeves, get behind those who truly want this country to remain a democracy, and push. The clock is ticking.

July 19, 2024

Functional brain networks are associated with both sex and gender

This is one of those butter-side-down papers, in that it demonstrates scientific proof of what to many of us seems perfectly obvious but that others can find difficult to accept: using fMRI imagery, Elvisha Dhamala et al have now actually shown that—in children at least—sex and gender are reflected in different neural networks.

Sex and gender are associated with human behavior throughout the life span and across health and disease, but whether they are associated with similar or distinct neural phenotypes is unknown. Here, we demonstrate that, in children, sex and gender are uniquely reflected in the intrinsic functional connectivity of the brain. Somatomotor, visual, control, and limbic networks are preferentially associated with sex, while network correlates of gender are more distributed throughout the cortex. These results suggest that sex and gender are irreducible to one another not only in society but also in biology.

That’s all I’ve got to say, really. Go read the paper at Science Advances for yourself. Yay science!