Sherrie Flick's Blog, page 3

September 27, 2011

SULLIVAN STREET LAMB: A Guest Post by Catherine Piccoli

This week food writer Catherine Piccoli takes over my blog with a tale about her family, Greenwich Village, and a live lamb. –Sherrie

With NYU just nearby, Greenwich Village looks like any other urban university setting at ground level. Bars, hipsters, trendy cafes, and bicycles are the norm now, but the apartment building where my Grandma grew up and where my Dad was born still stands there, above the hip din – all seven floors of tan brick and black-painted fire escape at 142 Sullivan Street.

Each time I crane my neck upwards to see the stone lion embellishments above the window casements, I can feel my family's history. This is where I come from. The stories my grandmother has taken to telling me lately (of all the boys that wanted to marry her; of something involving a bank robbery, mistaken identities, and a gun thrown into a sewer; of being serenaded by young Frank Sinatra at a Hoboken club after her brother's wedding; of herbs sun-drying in the apartment window) root me in that heritage more than the scent of espresso rushing out of the tiny coffee shop now nestled on the building's first floor.

Her latest tale was no different, told to me on a chilly Sunday in June in her mustard yellow kitchen in suburban Ohio, just about as far from the Village as one can get. The sun streaked in hazily through the windows as Grandma proclaimed that when she was a girl her father would bring home a live lamb on the subway for Easter dinner. I coaxed her on.

It was the 1930s. My Great-grandfather worked on the New Jersey coal docks, next to a railroad yard where food was delivered and bought by wholesalers and retailers to feed the big city to the north. Every year before Easter, when the lambs came in, Grandma's father would buy one from the railroad yard after work, put it in a cloth coal sack and carry it home to Sullivan Street on the subway. During the day, he tied the lamb to one leg of the four-legged stove and set out food and a dish of water for it. At night, it was left outside, tied to a steam pipe and apparently, miraculously never stolen.

Just before Easter, Grandma's father would slaughter, clean, and dress the lamb himself, between two chairs in the apartment's courtyard. All the cuts were cooked in the third-floor apartment for the big crowd, including Grandma and her four brothers, that ascended each Easter Sunday to eat and talk and celebrate.

Grandma's story, so matter of fact and told with a laugh, fascinated me. A little lamb riding the subway in a coal sack and standing in the midst of a bustling Italian neighborhood in one of the biggest cities in the world sounds more like a children's book (save the gruesome ending) than something that really happened. But happen it did, and it was so normal to her that Grandma doesn't really understand why I keep bothering her with incessant phone calls weeks later to try and tease out more details. "Yes, it happened every year…No, I don't know what he fed it…No, I wasn't embarrassed, it was just something we did…That's the way years ago they used to do things."

On my last New York trip, I snooped about 142 Sullivan more than usual, carefully snapping photos with my digital camera. The shaggy haired barista/owner of the coffee shop couldn't let me into the apartment's courtyard to take a picture of the place where all those lambs used to live. It no longer exists. He said the old timers of the area tell him that you used to be able to escape from your parents or even the cops through the open courtyard. But sometime in the 70s, buildings expanded and the yard was lost. All that's out there now is the back of the building behind.

But there are still some courtyards between the streets that I might be able to get access to. He suggested I walk around to the MacDougal side of the street to see.

There does seem to be at least one courtyard there, the back patio of a restaurant all set for dinner service. I peered through the front door and decided not to go in. I rationalized it away at the time but now I wish I had asked to walk back and see for myself. I wouldn't even need a photo. Just being there and knowing what it used to be like for my family would have been enough.

Catherine Piccoli lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where she studies and writes about food. When not cooking, eating, or obsessing over graduate school, Catherine can be found playing clarinet in a local community band. Follow her at: gigaEATS.

September 16, 2011

Artists Eat (at my house): J.C. Hallman, Many Apples

Each day, these days, a sweet, earthy fall smell rises from my kitchen as I chop, chop, chop into chunks and slices the apples that Rick and I trekked to my parents' farmhouse to pick.

Two bushels is, in retrospect, a lot of apples. Half McIntosh, half what my mother calls Yellow Translucent (which lean toward Granny Smith), these apples come from uncoddled trees, and because of that some years the apples are good, some years they're bad. This year being the best year for picking in my memory. Rick, up on the ladder, threw good-sized, plump apples at me for hours, as I then gently lobbed them into baskets. Four pies, 6 pints of chutney, 3 jars of jelly, and 3 loaves of apple-walnut bread later, I still have 2 dozen left.

So, it was with 2 apple pies that I greeted J.C. Hallman when he visited from Oklahoma the other night with his wife Catherine and friend Carmen. I added writer Marc Nieson and his wife, dancer Beth Corning, their daughter Gigi, and the poet Joy Katz to the desserty mix.

The first pie, made with McIntosh, was a traditional double-crust with thinly sliced apples tucked inside the tightly sealed top and bottom. Light on the sugar with a hint of cinnamon. With the tarter apples, I put together a crumble-topped apple custard pie laced with a hint of cardamom.

J.C. was in town because his essay "Spate and Spite" received second prize in Creative Nonfiction's "That Night" contest judged by Susan Orlean. About the essay, which will be published on CNF's website, Orlean says: "Evoking the tattered world of Atlantic City, a place of perpetual night, this piece fused reporting (about a 'spate' of suicides in town) with a vivid first-person narrative."

We have a tiny house and 9 is the most I've ever entertained here. By adding a vintage card table to the end of our farm table and pulling in the kitchen chairs from the floor below—it worked.

J.C., who goes by Chris if you know him well, read an essay he'd written especially for the night about the James brothers and their theories of chewing (included below). As we took seconds, more aware of our mouths and molars, Rick broke out the rhubarb-blueberry vodka I'd infused earlier in the summer, more red wine, and (our new house drink specialty) another shaker of bourbon brambles. Gigi had some nice cinnamon tea.

Comfortable and cozy conversation ensued. As well as some slow, deliberate chewing.

THE ART OF CHEWING

or

How Righteous Chew Guru Horace Fletcher Murdered the Inveterate Muncher William James

By J.C. Hallman

For Henry James, the human mouth was useful first and foremost as the bell that finally expelled the sounds that the literally conspiring organs of the body – lungs, vocal chords, etc. – produced so as to shape the various tones and harmonies of our speech. The mouth's secondary (and unfortunate) vocation was to serve as intake mechanism for sustenance, a vulgar process that left dirtied and crumb-flecked an otherwise precious instrument. The mouth's dual roles were never made clearer to James than when he happened, on a trip to America after a quarter century spent in England, to find himself on a Chicago train seated near a family just coming home from the opera, where "Parsifal" was then playing. The family was dually engaged on the ride. On the one hand, they chatted out their Wagnerian experience. On the other, they were, as James put it, "occupied after the manner of ruminant animals." They were a family of gum-chewers, all of them, and while opera "might be their secondary care the independent action of their jaws was the first." James was scandalized at the proposed view of a "gentleman rolling his bolus about while he talked to a lady, or…a lady who rolled hers…while he was so engaged." American society had sunk so low as to become a world in which men and women eternally chewed in one another's faces.

Chewing was better employed, James seemed to believe, as metaphor – to ruminate, after all, was to think. He'd used this tool himself. In 1890, when his brother William James published his magnum opus Principles of Psychology, Henry employed masticatorial allusion to explain the impending chore of its more than one thousand pages. "It will be a tough morsel for me to chew," Henry wrote, "but I don't despair of nibbling it slowly up."

William understood. Some years later, he called Henry's attention to a piece he himself had written about the American occupation of the Phillipines, a clever essay in which he mined his medical training's comprehensive knowledge of the body's digestive process for just the right metaphor to expose the folly of colonization. Surely, William suggested, we had prehended, or taken into our mouth, our opponent quite well. We had deglutted, chewed and swallowed, them even better. But could we be said to have truly digested or assimilated them? Hardly! Henry agreed: the imperial adventure would never amount to a satisfying meal. In his reply he happily extended his brother's metaphor: it would be "a long day before we…revomit the Phillipines."

It was only two days after Henry belched this out that William wrote with the most unusual of suggestions: chewing – actually chewing food – just might solve the digestive problems that had plagued Henry for almost all of his life.

"I am sending you a book by Horace Fletcher," William wrote. Fletcher was a food guru, and "Fletcherism" was a fad nutritional theory that claimed that the extensive chewing of one's food – at least thirty-two chews for all bites, including liquids, at a rate of one hundred chews per minute – produced increased bodily strength on a dramatically reduced overall diet. Even though both brothers were past sixty years of age, William thought Henry a perfect candidate for this "art of chewing" and he promised his brother a "great revolution in [his] whole economy." William planned to become a "muncher" too.

Given Henry's aversion to public chewing, one might suspect he would not shine to such a scheme. One could "Fletcherize" in private, however. Henry dismissed Fletcher's more grandiose claims, but otherwise dug right in. "To have eaten one meal, one only, really according to his rites," Henry wrote to his brother, "is to be disposed to swallow him at least whole."

Henry muched happily for quite some time. After two months, he was star-struck. "[Fletcher is] immense," he wrote, "thanks to which I am getting much less so." That July brought faint signs of trouble. First, Henry realized that he had less begun to lose weight than merely arrest its gain. Second, Fletcherism was every bit as boring as the tedious walks he hoped it would displace. Indeed, one could find one's mind wandering while exhaustively chewing, and wind up swallowing by mistake. Even more difficult was attempting to read at table. Henry came up with a range of questions he wished to pose to Fletcher, and asked William to introduce him. Their first meeting left him "happy in his guts."

Both brothers gnawed away a number of years on Fletcher's system. Eventually, however, Henry was driven by bouts of "pectoral trouble" to visit an actual doctor. The doctor prescribed exercise, which Henry had abandoned completely. "Fletcherism lulled me," he admitted, "charmed me, beguiled from the first into the luxury & the convenience of not having to drag myself out to eternal walking." He'd been so won over by Fletcher he'd begun to think "non-walking more & more the remedy."

On February 13, 1909, Henry sent William the shortest letter of their more than eight-surviving bits of correspondence. There was no salutation. "Stopped fletcherizing practically well – Henry."

"Poor Horace Fletcher!" William replied. Fletcher feared of what would happen to his business if it got out that Henry James had abandoned him. The two met again, this time for ten days. Henry was duly impressed. By his count, Fletcher subsisted on a small meal of Welsh Rabbit only once every forty-eight hours, and often ate only a third of his portion. Henry was inspired to recommit himself to a more "consistent and holier" Fletcherism.

The new effort lasted only a couple of months, and at first Henry wouldn't even detail what was wrong except to say that he had reached "defiantly & unmistakeably, the finally proved cul de sac or defeat of literal Fletcherism." He spelled out the ongoing crisis twelve weeks further on in a passage of characteristic stream-of-consciousness:

But my diagnosis is, to myself, crystal clear – & would be in the last degree demonstrable if I could linger more. What happened was that I found myself at a given moment more and more beginning to fail of power to eat through the daily more marked increase of a strange and most persistent & depressing stomachic crisis: the condition of more & more sickishly loathing food. This weakened & undermined & and "lowered" me, naturally, more & more – & finally scared me through rapid & extreme loss of flesh & increase of weakness & emptiness – failure of nourishment. I struggled in the wilderness, with occasional & delusive flickers of improvement…& then 18 days ago I collapsed and went to bed.

William and his wife were so moved by this note they finalized plans for a long-delayed visit. Ever ready with a medical opinion, William recognized the symptoms his brother described as those of one starving to death. The same letter noted that William's own health was on the wane – he reported an onset of dyspnoea, troubling breathing, though he believed it was not cardiac in origin.

Now under a doctor's care, Henry began to improve long before his brother and sister-in-law arrived to tend to him. It was a battle. The effort to re-learn to eat was a greater strain than the chewing cure had become. His gut had been left "intensely enfeebled & perverted"; it had forgotten how to digest anything. But now that he was chewing properly again, he had seen gains. His stomach came home from its "long adventure," and he told his brother that "all anginal symptoms have quite left me since beginning to disFletcherize."

He apologized for his previous note's all-too-dire tone. "I am still flushed with the sad consciousness of the pretty wild wail I addressed you from Rye," he wrote. He admitted that it was at least in part driven by a "great yearning" to see his brother. "Your advent," he wrote, "that will be my cure."

Which perhaps it was – Henry stopped Fletcherzing and lived another six years. William was less fortunate. Transatlantic travel had always laid him low, and when he arrived in England to rescue his brother, his own pneumatic symptoms advanced. He tried the baths at Nauheim; nothing worked. It was his heart, after all. He was now diagnosed with "aortic enlargement," and he noticed that his feet had begun to swell, his organ not strong enough to push the blood up from his toes. Henry improved such that he was well enough to travel back to America with William, when it became apparent they should flee the continent. They arrived home just in time. William died peacefully but prematurely. He himself had stopped "munching" long, long before, but the cure he'd once prescribed for his brother became a curse, and it found its way back to him in the end. ##

J.C. Hallman wrote about the history of the Slow Food Movement in the latest of his nonfiction books, IN UTOPIA: Six Kinds of Eden and the Search for a Better Paradise. More about his career can be found at JCHallman.com, and more about the correspondence of William and Henry James can be found at williamandhenryjames.blogspot.com.

August 31, 2011

Grilled Cheese Improvisation: Ciabatta, Istara, and Pickles

Texture is important. With a crusty loaf of ciabatta and a 1/2 pound of Istara (a semi-hard French sheep's milk cheese, slightly sharp and olive-y), I knew I hovered near grilled cheese nirvana.

What my sandwich needed was a little conflict though. Pickles abound in my fridge these days (see previous pickle recipe post), and once I thought about thinly slicing some onto my next grilled sandwich, I could see the tension building. Sharp but smooth cheese, crusty but thin bread, crunchy sweetly sour pickles…tension.

So I sliced the bread, smoothed butter on each side, heated up the pan, sliced the Istara, sliced the pickles, stacked everything inside snug—and grilled it.

With some stone ground mustard, it became a dramatic sandwich, a literary sandwich, with complex characters, rising action, and a predictable (but satisfying) ending.

August 24, 2011

Artists Eat (at my house): Nancy Krygowski and Luis Castellanos Valui

I felt it coming on…the need to make something complicated. In my 20s this impulse led to spontaneous road trips and bad relationships, but now it leads me into the kitchen.

The thought descends like a mist. Tourtes de Blettes. The scrumptious and strange sweet chard tart. Swiss chard booms in the garden. It's time.

Old friends are the type of people to have around when such a meal is brewing. And so I found myself surrounded by layers of friendship last Friday night. My old friend—a friend of over 20 years—the wonderful poet Nancy Krygowski and her husband Tom Kizer along with sculptor James Simon (my friend of over 10 years) and his friend, the artist Luis Castellanos Valui—a new friend to me—but a 20-year friend of James—just in from Mexico to paint a mural in the Uptown neighborhood of Pittsburgh. And, of course, my husband-friend of 14 years, Rick Schweikert. Connections ping-ponged around the dinner table. The kind of ease settled in that can only come with time, with knowing people and suddenly re-remembering why you've liked them for so long.

It's a two-day process, this tourte. Pick the chard, clean the chard, destem the chard, soak the chard again, make the crust, chill the crust, soak the raisins in brandy, chill the crust again, cook the chard, grate the parmesan, peel the apples, slice the apples, drain the chard. I pace myself. I really love this kind of baking. So, while I work through the complicated and, granted—very French—process of the tourte, I think through what I'll make for the rest of the meal.

There are beautiful pattypan squashes in the garden, the little UFO-shaped veggies that I love to sauté with cumin and garlic. They lean toward buttery and sweet and will passively compliment the tourte, the centerpiece of the meal. I have a half dozen small beets that will look stunning settled in on the tray with the squashes.

I think about the oodles of yellow pear tomatoes on the vine. I'll add olives and goat cheese, chickpeas and some parsley and pepper to them.

Dessert is a specialty of mine, and Nancy will have expectations for something glorious. James doesn't love super sweet things, and I have never met Luis, although James assures me when I call that he will eat anything. I get the brilliant idea of making a carrot cake with carrots from the garden—a low-sugar recipe that depends on an apricot filling for its sweetness. I've made this cake before, and it's fairly simple. This time, however, the cake becomes a flat rock in the oven. The key to this dessert is slicing the cake down the middle and filling it with apricot goo. The cake does not rise, will not rise. But I'm working in rounds here, and am ahead of myself dessert-wise. I abandon the carrot cake on the cooling rack, call it a failure, and turn to the blueberries my friend Marc Nieson has brought back for me from a recent trip to Maine. I find a not-too-sweet, interesting-looking Blueberry Molasses Cake recipe and think if I pair it with the vanilla coconut ice cream that I love from the co-op, everything will be back on track. The smell of molasses filling the house is worth the whole carrot cake debacle.

Suddenly the tourte is rolled, layered, sealed up tight in its crust, egg-washed, and in the oven—baking like a textbook tourte. There is no chance for a do-over on this thing. I put together some pre-dinner snacks for the guests, soon to arrive—homemade pickles and almonds, some homemade ricotta cheese (I'm on a roll), buttermilk bleu cheese, ciabatta, and crackers. Rick pulls together ingredients for cucumber margaritas.

The table is set, and my friends old, older, and new come through the door carrying bottles of wine, giving hugs, helping me carry food up the stairs to our cozy dining room. The little dog barks in joyous circles because these people are some of his favorites too.

It's easy this coming together, sitting down. Luis is like an old friend, instantly—except he's praising our city, which he has just seen for the first time that day. He loves Pittsburgh—the architecture and the hills. And then we turn to loving our city again like we do from time to time, remembering how fantastic it is and how so many people don't understand this and in that way we can hide out here and have wonderful lives without the complications that a city with an ego must bear.

We eat slowly. As the meal proceeds, Luis talks about the James he knew in the past. "He was crazy," Luis says, laughing. James lived in Mexico in those years and made his living making violins. He needed to make one violin a year to live well. James tells us about the final piece of wood that is placed into the violin—the piece that takes it from just a sculpted wooden box to an instrument. Translated as the soul in many languages this small piece of wood is like the magic that the maker holds and places into his creation. We all understand.

Luis gestures with his hands as we talk more about music, and Nancy recites a brief version of the lecture she'll soon give at Chautauqua on the history of the list poem. We plan to write our own list poem, and then get sidetracked discussing internet radio technology and looking at maps online to see where Luis lives in Mexico, in Chapala, on a beautiful lake.

The cake is served and some take seconds even though we've already consumed a lot of food. Luis unveils the painting he has brought for me, Good Morning, Good Coffee, which I love, and I know by now that we both love coffee and so I love the painting just a bit more.

The little dog is asleep on the floor by my feet, and we all settle back a bit and then say our goodbyes—head back into our lives, into our histories that we're all making with each other.

Luis Castellanos Valui

While in Pittsburgh, Luis is painting a mural as part of "Art on Gist Street" in Pittsburgh's Uptown neighborhood. It will be installed on the side of the Deaf Club's building and incorporate American sign language into its design. Based in Lake Chapala near Guadalajara, Mexico, Luis' paintings can be found in collections worldwide.

Nancy Krygowski

We all know Sherrie is a superb cook in addition to being a superb writer.

So any truth-seeking poet who has known her forever has to ask herself, Did I get pleasure knowing that the carrot cake failed to rise?

The answer: No, not at all.

What I got pleasure from was the creamy homemade ricotta and chewy ciabatta, the crunchy crackers and refrigerator pickles, Blue bouncing around my feet, Luis's white hair and dark eyebrows that bounced as he talked, Sherrie moving confidently around her small kitchen as she has for years.

I got pleasure from the cucumber margarita I could chew while I drank and the grey flowered curtains I've admired for a long time. From the knowledge that pattypan squash are smooth and buttery, a good accompaniment to baby beets. From the smoothness of my husband's face and the smoothness of the tourte's crust peeking out from the table behind him. From the sweet surprise of the apples layered under that crust. (See poem.) From the brightness of Luis's painting, Good Morning, Good Coffee and the brightness of his words. From the complex deliciousness of good, old friends.

What the Apples Did: Tourte de Blettes

Worried the pine nuts were their own innards

their own blanched seeds.

Ignored the raisins, having shared beds with them

before.

Said, We belong in baskets! In pies!

In some teenager's hand!

Gave in.

Nestled against the Swiss chard

distant cousins with the same favorite book.

Pretended to be offerings

of the sweet sliced moon.

Pushed yet comforted

like good, old friends.

Convinced artists and realtors

writers and engineers

There will always be surprises.

Best listen

with more than your ears.

Best taste

with more than your tongue.

Nancy Krygowski's first book of poems, Velocity, was chosen for the Agnes Lynch Starrett Prize from the University of Pittsburgh Press. She is a recipient of a Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Individual Artist Fellowship, a Pittsburgh Foundation Grant, and awards from the Academy of American Poets and the Association of Writers & Writing Programs.

August 17, 2011

Understanding Cucumbers: The Pickle

Having gardened for over 12 years, you would think I'd made my peace with vegetables. Yet, I hadn't seen any point in growing cucumbers until last year. I don't particularly like cold soups and cucumbers strike me as a bit slimey in their just-picked state. But then I realized I could pickle them. And a full-on household infatuation with pickles kicked in.

Even with a few gardening notches in my utility belt, I hadn't ventured too far into the canning realm. After planting my cucumbers last year, I started my search for an interesting pickle recipe. Something not sweet but not sour. Something revolutionary in its pickleness. Finally I found a fine one that used apple cider vinegar instead of white vinegar and used specific hand-ground spices instead of a pickling mix. They are refrigerator pickles, and that makes sense to me because they are so good there is no use in formally canning them, because you're just going to eat them up. I did think the original recipe was too sweet, and so I took to fiddling like I do and came upon my own pickle interpretation. I love these pickles. They are tart and interesting. They make you dig through the jar to find the last wedge. The fresh wig of dill you put on top makes everything good and fine and herby in all the right places.

Make some today.

Recipe

The following recipe is adapted from Bon Apetit.

1 small red onion thinly sliced

4 cloves of garlic, halved

2 pounds medium pickling cucumbers, scrubbed, cut into wedges

1 large bunch dill, coarsely chopped (stems included)

1 tablespoon yellow mustard seeds

2 teaspoons whole white peppercorns

1 1/2 cups apple cider vinegar

1 cup water

1/2 cup sugar (I use Sucanat)

3 tablespoons coarse kosher salt

2 teaspoons dill seeds

Prep

Divide sliced onion and garlic between two 1-quart wide-mouth glass jars. Strategically pack the cucumber spears into the jars. Top each jar with a wig of dill.

Using a mortar and pestle, crush the mustard seeds and peppercorns together. Place the crushed spices in a medium saucepan. Add vinegar, 1 cup water, sugar, coarse salt, and dill seeds. Bring the mixture to boil over medium-high heat, stirring until the sugar dissolves.

Ladle the mixture evenly over the cucumbers. Leave jars uncovered and chill 24 hours. Cover glass pickle jars tightly with lids. They will last at least 3 weeks. But if you're like us, you will eat them up and long for more.

August 9, 2011

Artists Eat (at my house): Bob Marion–Guitar, Pizza, Salad

Pizza

People are fierce about their pizza, taking sides in heated, generations-long arguments regarding thick, thin—crispy, chewy. But all that territorial debate goes out the window if you make someone a pizza from scratch in your home. It's like coaxing a wild animal into submission, sitting someone down in front of such a miraculous, inventive thing.

And so it happened that Bob Marion stopped over one summer evening a few weeks ago to play some music. We both detest the word "jam," so we "hoot" once a month. I am a new and inexperienced ukelele player. Bob is a patient man.

It was a glorious summer day, the kind of day that leads directly into a lush evening and a future fine memory of silky air and dense grass. The garden creaked upwards around us as Rick fired up the grill, a mid-sized Weber we've grown to love. We use hardwood charcoal, and Rick finesses the thing's heat using the lower vents in combination with the lid in a mysterious ritual I've never figured out. This night we set the pizza stone on the grate before everything got too hot, and then when Rick said go—at the peak of the heat—I slid the pizza crust onto the stone, followed by a slur of olive oil, and then the toppings and cheese.

Yuengling bottles were lined up in ice in a little cooler. I grabbed one, and as the grill heated, picked lettuce and kale and radishes from the garden, gathered together a bowl of new potatoes from the coop. Sometime during my foraging someone brought out the bottle of Maker's Mark, some tiny sipping glasses.

I de-vein and then soak about 6 cups of roughly chopped kale, heat my pan to medium-high, and add 2 tablespoons of olive oil, 2 cloves of thinly sliced garlic. I let the garlic sizzle for a minute, and then add the greens. The water that lingers on them from the soaking helps steam the kale right in the pan. I sauté everything for about 8 minutes or to when the kale hits vibrant green, turn off the flame, and add 4 chopped up radishes, salt, and pepper. Next, I slice the potatoes—about a pound of them—very thin. Heat 1 tablespoon of olive oil and 2 more cloves of minced garlic in another pan, let it sizzle for a minute again, and then add the potatoes and cover, stirring occasionally, until they begin to brown about 10 minutes later.

I have pesto on hand, because it's summer, and it's a staple in my fridge (see my pesto recipe in a previous blog post). I scoop some of the thick basil goodness out of the glass container and out onto the pizza on the stone after its initial drizzle of oil, then sprinkle on the kale-potato-radish mixture. The final act is tossing about ¾ cup of freshly grated Parmesan over the top, some salt and pepper. Rick grills the pizza for 10 minutes, and then it's ready to roll.

The salad we eat includes a simple lemon vinaigrette, nuts, seeds, lettuce, and fresh garden peas (blanched for 20 seconds in salted boiling water).

We sit on our deck, which has a beautiful view of our city, with Bubby the Yorkie fetching sticks up from the yard every now and then. The world sighs.

Music

Bob brings out his guitar as it gets late, and we move inside to escape the mosquitoes. Bob is a long-time guitar guy—more comfortable with his instrument than without. Rick is on vocals. I play my banjolele, hovering over my songbook for my own moral support.

And we play into the night. I imagine the sounds of "By the Light of the Silvery Moon" traveling quietly out the screen door and drifting down our street, greeting a few happy sleepy neighbors, some drunken students parking cars, the stray dog sneaking into garbage—the groundhog waddling her way into the fruiting raspberry bushes.

Bob Marion is a singer and songwriter, ocassional playwright and actor, and all around facilitator. He was a co-founder of Seattle Public Theater and proudly held the title of "Meat Guy" for the Gist Street Reading Series.

Here is Bob singing "Sittin' by a River" in my living room. Take a listen.

Preamble

Blue, the Yorkie in residence at the Holt Street estate of Sherrie and Rick, often stays with me when the humans leave town. He seems to find that I'm an acceptable substitute and for the most part we get along just fine. But on the morning of their return—somehow, he just knows—his hyper-vigilance and tendency to yelp and screech at each and every passer-by can jangle the nerves of the most sympathetic dog-sitter.

But this last time was different. Not for Blue; he was just as annoying as ever. Rather he would have been, had I not been gripped by some of the same enthusiasm. I can't explain it, but when Sherrie and Rick showed up some recent Monday morning to pick up The Dog, I had a feeling something special had happened while they were away.

My feeling was confirmed when Rick opened the hatch of their sensible new Nissan to grab and display what was surely a case for some stringed instrument. But its size and shape were puzzling. It weren't no guitar, I knew, nor was it a fiddle. The thing had a homemade. backroads sort of feel, like something you could only find if you weren't looking for it, at a swap meet, say, far from home, discovered while trying to find the interstate after breakfast. And when it was revealed to be a banjolele, and further, that it was Sherrie's banjolele, I remember thinking it was most right and quite good for her to have such a thing.

So I was of course thrilled when I was invited for dinner and a South Slopes hoot with two of my favorite humans.

DINNER

I know others have rhapsodized in this space about The Deck, so I won't, except to say that it was a perfect night to cast mine eyes above and beyond the mighty Monongahela, sip Yuenglings with Maker's Mark, and scarf what is easily the worlds' most dangerous food, Sherrie's garlic scape pesto, with a perfect little loaf of Allegro Hearth goodness.

And that was just the first course. A grilled pizza and a fresh garden salad were yet to come.

Now. Because this night was about music as well as food, I got to thinking that a great meal is like a great song. In each, the ornamental and the structural need to be in perfect balance. Take Ringo Star from the Beatles and what have you got? A lot of great chord changes, melodies, harmonies, and bass notes, but nothing underneath to drive it all. You'd have a beautifully designed car with a flashy paint job with no engine. And though I'll admit I was skeptical about the potatoes on the pizza, I see now that they had to be there to complete the radishes and kale.

As I thought about it more, I began to see it. We were in a roadhouse in West Virginia. A five-piece honky tonk band was playing for all they were worth. An old up-right bass and a stripped-down drum kit propelled the band through all the Hank Williams and George Jones you could imagine. The guitar wailed hard and tough and sweet over the melody through a beat-up old tube amp. At the mic, in the center of it all, the singer sang of being broken, busted, and free in a voice seasoned with hope and loss. And just to her right, where you'd have expected a fiddle, the banjolele player plucked those achingly harsh and fragile notes and sang a sweet, high, lonesome harmony that'd break your heart if it wasn't already there.

Toward the end of the second set, this singer asked us all to settle down, they were about to do a special song. A new song. And it was all about love and how, if you believed in it, it might could work.

I can't remember when I've eaten a better song.

July 26, 2011

Grilled Cheese Improvisation: Black Brandywine Tomato

I grow a variety of heirloom tomatoes in my garden and in the past week they've kicked in. My favorite, the tomato I would take with me to a desert island, is the Black Brandywine. It has a dusty red bottom that rises to a crown of green. The inside meat is dense but still perky. A slice of this tomato grilled with Gruyère in between multi-grain sunflower bread is the answer to many of life's problems.

July 19, 2011

Ricotta Cheese to Gnudi: Homemade Delicious with Bo Young's Help

As I tucked my finger into the room temperature cheese and took a small taste, the creamy texture accented by a tiny ting of lemon, I realized I had been—for years—eating an unimaginative imitation. The ricotta I'd spooned out of a tub and layered into my lasagna was just the idea of ricotta, a rough estimate. Here before me rested the real deal. This ricotta sang a little tune, as it shimmered in its authenticity.

I had typed "Homemade ricotta cheese. Why not?" into my Facebook status after Smitten Kitchen's blog recipe for it popped into my inbox. With leftover half-n-half and heavy cream from the goat cheese flan I'd made for our wedding anniversary dinner, along with a bagful of lemons on hand, it seemed easy to start in on a cheese experiment.

I walked the dog while waiting an hour for the curdling dairy to strain out its whey and returned to the final ricotta. I could've eaten it as it was on crackers and remained exuberant. But just then a message from my Facebook friend Bo Young rolled onto my computer screen. "You should make gnudi with your ricotta," he said. "They're divine." Just as quickly he messaged me a recipe.

Even though I'd planned for the night's dinner to be relatively simple, I soon took to the task of making the gnudi. Why? The word "gnudi" looked like "gnocchi," and it got my nostalgia running high. Back in the late 80s and early 90s when I lived first in New Hampshire and then California, a certain large group of friends got together fairly frequently to make huge gnocchi feasts. The dough would be made from scratch using potatoes, and then we'd stand around a large table and roll the gnocchi by pressing one finger in and push-rolling, tossing them onto dozens of lightly floured cookie sheets. Thinking about those big group dinners and my early foodie years always makes me happy, and so I set about figuring out the gnudi—without a herd of friends, but with their spirit nearby—assuming gnudi must be gnocchi's distant cousin.

I discovered the last container of last year's homemade tomato sauce in the freezer, and it seemed perfect using it to celebrate the first making of cheese in my house, the onslaught of summer, the memories of friends and meals, the new friends who come unexpectedly into your life, and the gnudi themselves! Delicious pillows.

Now in love with this food as much as Bo, I invited him to write a few words about gnudi, which also has a little to do with gnocchi for him too.

Bo Young

It was my 40th birthday and I was in Assisi, Italy, sitting at a table in a restaurant called I Leoni, perched atop catacombs in the hillside where the local priest had hidden Jews in WWII. I asked the chef to surprise us, and after he had invited me back to the kitchen to see his operation, I sat down in eager anticipation.

The memory of that meal has faded now, save for one primi piati that stayed with me for 20 years. Soft, silky pillows—that in my mind I remembered as gnocchi—a small arrangement of three or four, as I recall, on a plate masked with a gorgonzola sauce. Eyes-rolling-back-in-your-head divine.

For twenty years I had tried and failed to recreate these delectable bites. Everything was too heavy no matter how lightly I whipped potatoes, no matter how many "lifters" I attempted to add, all fell like belly bombs on my disappointed palate.

I'm in upstate New York now, and I produce an event at the Pember Library and Museum here called First Fridays, where in addition to local artists and music we feature local food. I visit local farmers and bakers and caterers and invite them to show their artistry right along with the framed pieces. The selections are world class. In some cases award-winning. And it was through this that I discovered Dancing Ewe Farm and Jody and Luisa Somers sheep operation.

I've spent many a Wednesday with Jody, elbow deep in ground up lamb, mixing spices making Daniel Boulud's recipe for merguez sausage. And every time I leave, Luisa gives me a basket of their sublime sheep's ricotta. Tucked away on their website I found a recipe to use their ricotta. For gnudi. Gnot potato gnocchi…ricotta gnudi! Who gnew?

~Recipe for Gnudi~

By Bo Young

First written about on Bo's blog: http://wondermachine.typepad.com/certainseason/

1 c. whole milk ricotta cheese [I recommend following Smitten Kitchen's recipe for homemade ricotta, posted here. ~SF]

1 lb. fresh spinach (or frozen, thawed and squeezed dry) [I used chopped, de-stemmed Swiss chard from my garden. Blanched quickly in the waiting, boiling gnudi water and then squeezed dry. ~SF]

1 c grated fresh Parmesan

2 eggs

2 egg yolks

¼ tsp. freshly grated nutmeg

1 tsp. salt

1 tsp. freshly ground black pepper

5 Tbls. all-purpose flour, plus 1 c. for coating

1 jar marinara sauce [I used 2 c. homemade tomato sauce. ~SF]

1. Bring a large pot of salted water to a boil.

2. In a large bowl, mix ricotta, spinach, Parmesan, eggs, and yolks. Stir in nutmeg, salt, pepper, and flour. Form mixture into small quenelles.

3. Dredge the formed gnudi in flour to coat, tapping off the excess. Slide the formed gnudi into the boiling water. Be careful not to overcrowd the pan; work in batches if necessary. Remove the gnudi using a slotted spoon after they float to the top and have cooked for about 4 minutes.

4. Arrange gnudi on a platter and lightly drizzle with marinara sauce.

Makes about 16 gnudi. Serve with a fresh garden salad.

Bo Young published White Crane: A Wisdom and Culture Quarterly for Gay Men for seven years and is editorial director for White Crane Books. A devoted epicure, he was a caterer in Palm Springs and has cooked in two and three star restaurants in Los Angeles, New York City, and East Hampton. Originally from Chicago, via San Francisco, Los Angeles, Palm Springs, Connecticut, and New York City, Bo now lives in upstate New York with his beloved partner, William Foote, a cat and a dog. He is in his 60s but he reads at a 70-year-old level and can still lift heavy things.

July 12, 2011

The Egg Route: Farm to Table, 1953

Conversation and a big bowl of steaming mashed potatoes traveled around the long oak table the day I first heard about my dad's egg route. It was another Flick holiday, a plate of ham, a basket of rolls—everything eventually passed to the card table, pushed up snug to seat the 20 plus people my family has become.

My dad likes to reminisce, and I like to ask questions. We talk through dessert (usually a selection of 5 or 6 homemade pies), and continue sometimes even after most everyone else has retired to the living room to nap and watch sports. While I can't remember what I ate for breakfast, he easily recalls the name and hometown of a person he worked with for two months, 58 years ago.

I learned that day that the urban eater's desire for local farm fresh eggs isn't a new thing. That the act of farm-to-table kept my parents in gas money and connected to both the city and their rural roots for the first four years of their marriage.

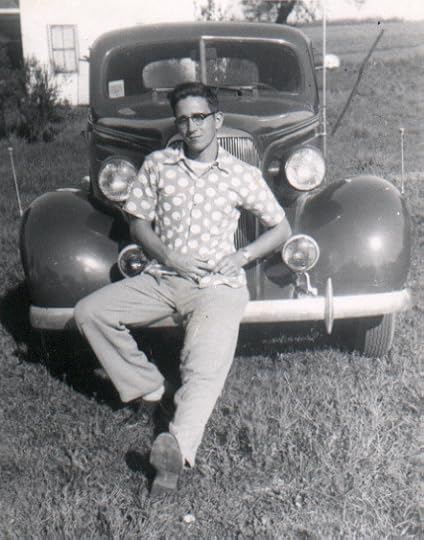

In 1953, just graduated from high school, Dad took a job with the Pennsylvania Highway Dept. Survey Corp. His supervisor was a mean guy, unfair to his workers and foul mouthed. My father wasn't thrilled with this situation, and after the supervisor threw Howard Raybuck from West Hickory up against a bus and said that he'd beat the [expletive] out of him if he made a mistake again, Dad knew he needed to find a different job.

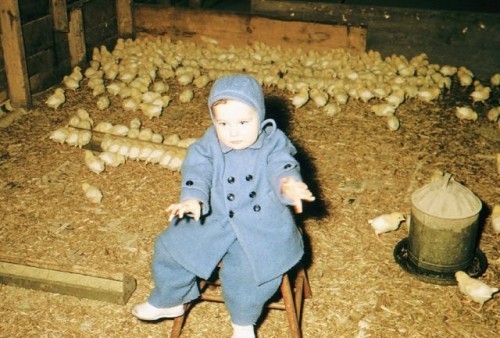

Tionesta, Pennsylvania, located in Forest County, at the southwestern edge of the Allegheny National Forest was and still is a tiny town surrounded by small farmsteads. My mother's family ran the McWilliams Dairy Farm, and my relatives still grow crops on their land. From the age of 7 Dad did farm work. There's a great story about him driving a big truck when he was so little he couldn't see out the windshield while engaging the clutch.

Just around the time that Dad yearned for a career change, his friend Karl Karlson suggested he apply for a job at the Westinghouse Electric Plant in Pittsburgh, where Karl worked. The plant, a sturdy brick building on Penn Avenue, rested between the neighborhoods of Point Breeze and Wilkinsburg, across the street from the (still there) shot-and-a-beer Evergreen Cafe.

My father made the trek into the city like so many other rural men in the U.S. at that time. As he put it, "That next Monday I drove to Pittsburgh, walked into the Westinghouse plant, and asked the Personnel Manager, Logan Roan, for any job that would allow me to enroll in a night school program. Roan said I could start as a Core Winder the next week at a salary of $156 per month."

Dad, 18 years old, moved to Pittsburgh, moved in with Karl and his sister Marsha, a school teacher, and my parents set a wedding date for that November. They'd gotten engaged at their senior prom, and soon were married and renting their first apartment in Wilkinsburg along with Dad's twin sister Doris, two hours from their families. Both Doris and my mother found secretarial jobs and they split the $50-a-month rent three ways. "We ate lots of Spam, potatoes, and things we could bring back from the farm. We did quite well," Dad noted, "and were able to save some money."

I should note here both the Flick and McWilliams clans were large—6 siblings in the Flick family and 12 in the McWilliams'. Every weekend my parents drove back to Tionesta to have supper at the McWilliams' on Friday and Saturday, and then Sunday lunch at the Flick's. Grandma Flick cultivated a huge, beautiful hillside garden and was an obsessive canner, pickler, quilter, and rug hooker. I still remember the taste of her unsweetened concord grape juice and her sweet-and-sour pickle relish, always served in a cut class bowl.

Mom hung out with her sisters—Edna, Lois, and Arlene. Dad hunted and trout fished with my uncles Gene, Maurice, Jake, Harry, and Ralph. Mom's sisters made the same weekly weekend trek in from Erie with their husbands and children in tow. They would all check in at the McWilliams Farm upon arrival. "I don't know how Grandma and Grandpa McWilliams put up with us," Dad said, "but they would be upset if we didn't come home."

What does this have to do with eggs?

By 1955, Dad's salary was up to $250 a month. My brother Danny was born. They moved into a bigger apartment, and Doris moved back to Tionesta to marry Jim Tucker. "Somewhere in the process our Pittsburgh friends knew we were going to the Farm in Tionesta every weekend," Dad told me. "I told them Shirley's brother had a chicken farm, and I had access to good fresh eggs. At first I would bring back a few dozen as a favor for a few friends. Then the word got around that I could bring back fresh eggs at a good price."

Since my parents had some difficulty paying the 25 cents a gallon that gasoline cost at the time, Dad determined they could subsidize their weekend trips if he charged people 10 cents more than he paid for the eggs. And so the egg route was born.

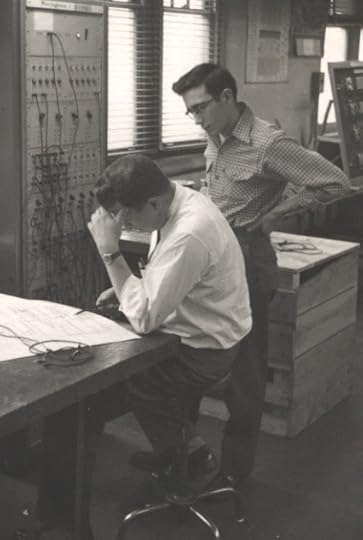

Dad picked up the eggs in Tionesta each weekend, and then delivered them Monday morning before his workday began. Around this time, Westinghouse had moved into a 4-story plant in East Liberty, radically upping potential egg sales. The egg route exploded to over 100 dozen per week. "Management, security officers, secretaries, people from all parts of the plant were my customers," Dad said.

I love the vision of my young, optimistic father walking into the plant (stark industrial rooms filled with wires and buzzing electronic progress), carrying trays of freshly laid eggs.

Ralph, Mom's oldest brother, a "gentleman farmer," kept the chicken coop. He gathered the eggs each day, brought them to the spring house, and put them through an egg washer. The second level of the spring house was damp from the creek running through the room below. "The grain and various chicken feed had a good smell," Dad remembered. "The spring house was cluttered with egg baskets, egg boxes, and various milk separator parts and binder twine." Ralph made a good supply of dandelion wine each year and stored it in the spring house to keep it cool. "He would offer me a drink from time to time," Dad said. "It was real smooth."

Dad rigged a candling device, checking each egg for the blood spots that his urban customers adamantly refused. The double-yolked eggs, on the other hand, were extremely popular. "They loved them," he said. At the peak of his egg business he had to visit 3 to 4 farms to fill his orders. He made some good friends with local farmers in Redbrush—the Alexanders, Korbs, and Mongs. "When I would go to the Korbs for eggs during the middle of the winter," Dad remembered, "she would give me some fresh apples that they kept in their spring house." Keep in mind that from December 1954 to June 1957 my brother Danny was in the car with my parents, the eggs, suitcases, and the bags of canned goods and garden produce Grandma Flick handed out.

They traveled to Tionesta on Route 8 through Oil City, no expressways yet existing. "Pittsburgh was still a smoky city, and you would have soot on your car and house a lot," Dad said. "The houses we lived in had Coal Furnaces. You would notice the clear air and quiet nights when we were in Forest or Clarion County. Our favorite stop on each trip was the ice cream store in Harrisville." Hughes, also known as The Ice Cream Factory, has been in operation since 1928. Gary Hughes runs the store, still there on Harrisville's Main Street. They serve their own Penn-Gold Ice Cream.

By this time Dad had inched another notch up the long Westinghouse ladder to a position working directly with the engineers, making $300 a month. "They were pleased that I was going to night school four nights per week. When I had some spare time I would do my homework, and they would help me with any math or science questions," Dad said. Most of Dad's fellow employees at Westinghouse were from the Pittsburgh area, and a boy migrated in from the country was a novelty to them. Dad, a friendly and curious guy, made lots of friends.

Yet by July 1957 he had to make a hard decision. My father wanted to become an engineer, working his way through school, but he needed to make more money than Westinghouse could offer him with his present skills. Even though he'd earned an academic scholarship that year, he and Mom decided to move to Koppel and then Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, and my father trained to become a life insurance salesperson. With this move, the egg route came to an end. You can imagine Dad's disappointed customers reluctantly buying eggs at their local super market each week.

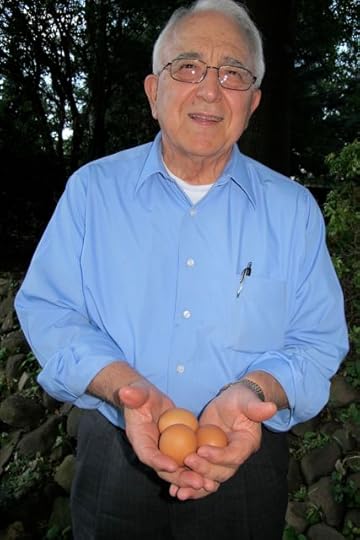

My parents settled in Beaver Falls and still live there today. They purchased Uncle Ralph's farm in 1987, making a big circle in this egg story, and it is now a weekend retreat for my family, and where I got married 14 years ago. The chicken coop is gone, but the outline of its stone foundation is still there. The spring house remains the water source for the farmhouse, and Dad said when they bought the farm there were still a few jugs of dandelion wine in there. He was tempted, but decided it was best to dump them out.

These days when I visit and walk out into the farmyard to inhale the wonderful silky night and zillions of glittering stars, I think about how hard it must have been some Sundays to pack up that car and head back into the city, slag heaps aglow.

Shirley Flick's Deviled Egg Recipe

1 dozen fresh eggs

¼ – ½ tsp. prepared mustard

Miracle Whip

Paprika

Salt and pepper

My mother makes her deviled eggs from memory, but she wrote down this recipe for me. They are delicious.

Hard boil one dozen eggs by cooking for 20 minutes, remove from water and cool to a temperature you can handle them. Peel off the shells, cut in half, and remove yolk. Mash the yolk, add salt and pepper, 1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon of prepared mustard, and enough Miracle Whip to create a firm consistency. Fill the egg halves, with the prepared filling and sprinkle with paprika. Place in a deviled egg dish, refrigerate until meal time.

Don and Shirley Flick have been married 57 years. Don Flick is now a retired Senior Partner at Metropolitan Life, where he has worked for 54 years. Shirley Flick is president of the Heritage Valley Auxiliary, where she has served more than 18,000 volunteer hours. They have three grown children, seven grandchildren, and two great grandchildren.

July 5, 2011

Grilled Cheese Improvisation: Beemster Graskaas and Pesto!

I'd already ordered a half pound of Cabrales at Pittsburgh's Penn Mac deli when I asked the nice counterperson to recommend the best cheese for grilled cheese sandwiches. I think my cheese cred, established by selecting a smelly gooey bleu, pushed her beyond suggestiong cheddar to the magnificent, seasonal Beemster Graskaas.

I'd already ordered a half pound of Cabrales at Pittsburgh's Penn Mac deli when I asked the nice counterperson to recommend the best cheese for grilled cheese sandwiches. I think my cheese cred, established by selecting a smelly gooey bleu, pushed her beyond suggestiong cheddar to the magnificent, seasonal Beemster Graskaas.

Beemster Graskaas (fun to spell as well as say) comes from the milking of the Dutch Beemster cows after they've first eaten the fresh spring grasses. You can learn more about this cheese and see a joyous video of the happy looking cows' spring foray here. The cheese is sold in limited quantities for only a limited time each year. It's creamy and smooth and, if a cheese can be happy, it's happy too. And—it's true—Beemster Graskaas is perfect for melting on a grilled cheese sandwich, especially if you have a crusty wheat loaf on hand.

This grilled cheese sandwich also includes a slathering of pesto. Each year, I anxiously wait for my basil plants to grow enough so I can start harvesting leaves for batch after batch after batch of pesto. It doesn't stay long in our house, and once the basil is done for the year, so is the pesto making.

Recipe

Basil Pesto

3 c. packed, fresh basil leaves, roughly chopped

1/4 c. nutritional yeast

1/2 c. olive oil (or more if needed)

1/2 c. walnuts, roughly chopped (I toast mine lightly for a few minutes in a pan on the stove as well)

1 1/2 tsp. sea salt

3 garlic cloves, crushed

2 tsp. fresh lemon juice

Pesto lovers find their signature pesto, and then swear by it. This is mine, and it comes from Isa Chandra Moskowitz's Vegan with a Vengeance cookbook. You can substitute freshly grated parmesan cheese for the nutritional yeast for a more traditional version.

Combine all of these ingredients in a food processor or blender (or in a coffee bean grinder if you're desperate) and combine until you have a grainy but not silky consistency. Eat. With. Anything. Including on grilled cheese sandwiches.

Yum.

Sherrie Flick's Blog

- Sherrie Flick's profile

- 38 followers