Mal Warwick's Blog

September 3, 2025

The outrageous woman who helped shape the Gilded Age

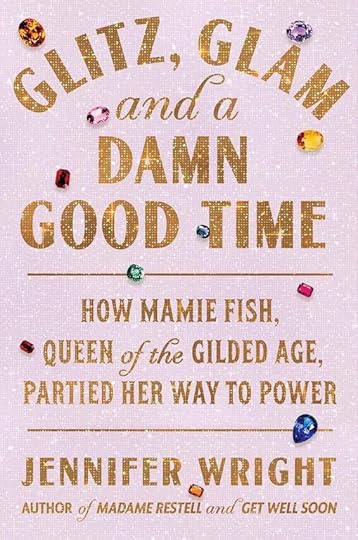

Mark Twain satirized the period as the Gilded Age, suggesting that an overlay of gold plating hid the seamy reality underneath. Later, historians fixed the term to the years from the late 1870s to the late 1890s. Then, America emerged from the devastation of the Civil War to become the world’s preeminent industrial power. And a few prominent men held most of the great wealth generated by this growth. They possessed private fortunes surpassed only by today’s high tech billionaires. Meanwhile, their wives, circumscribed by the sexist conventions of the Victorian era, rarely played any role in the economy. Instead, they held their own competitions for power and acclaim by building grand houses and holding parties. Journalist Jennifer Wright tells the story of one of the most acclaimed of these women in Glitz, Glam, and a Damn Good Time. It’s a biography of the Gilded Age itself.

Prominence based on genealogy and wealthWright’s subject is Marion Graves Anthon Fish (1853-1915), known to her friends as Mamie Fish or Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish. The Fish family (who called themselves “the Fish”) did not possess great wealth. Their prominence rested on their genealogies. The Fish traced their ancestry back to the Dutch colony that preceded English settlement in New York. Mamie’s husband, Stuyvesant Fish (1851-1923), was the son of Hamilton Fish (1808-93), formerly Secretary of State, President Ulysses Grant’s most trusted advisor, and in turn the son of Alexander Hamilton’s best friend.

However, the Fish were far from poor. Later in life, Mamie claimed that the family’s fortune never exceeded $3 million. In 1890 dollars, that was the equivalent of just over $100 million today. But the context suggests that Mamie was low-balling the claim. Even so, the family’s net worth paled beside the wealth of such men as Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller. But Mamie didn’t need hundreds of millions to “party her way to power,” as Wright suggests.

Glitz, Glam, and a Damn Good Time: How Mamie Fish, the Queen of the Gilded Age, Partied Her Way to Power by Jennifer Wright (2025) 235 pages ★★★★☆ Marion Graves Anthon Fish, known as Mamie Fish or Mrs. Stuyesant Fish. Does this woman look like she could EVER have a good time? Image: Newport Daily NewsChatty style with lots of exclamation marks

Marion Graves Anthon Fish, known as Mamie Fish or Mrs. Stuyesant Fish. Does this woman look like she could EVER have a good time? Image: Newport Daily NewsChatty style with lots of exclamation marksI don’t read gossip columns or celebrity stories in women’s magazines. But I imagine that readers of such things will find Jennifer Wright’s style in Glitz, Glam, and a Damn Good Time to be familiar. It’s casual, often chatty, and features liberal use of exclamation marks.

Wright prefaces Mamie’s story with a brief history of party-giving. This approach makes for an eminently readable story. But if you’re looking for a feminist angle on the Gilded Age, which was filled with consequential developments in America’s economic and political history and marked advances for women, you won’t find it here. This is Mamie Fish’s story. It’s about parties. The palatial homes where they were held. What people wore. What they ate. And what they thought about Mamie and Mrs. Astor and Ward McAllister and the other movers and shakers in Mamie’s social circle.

In fairness, Wright pays lip service from time to time to the contrast between the ostentatious (and obnoxious) display of wealth by the uber-rich and the abject poverty of millions of workers. She freely acknowledges the desperation of so many Americans in thrall to the winner-take-all economics of the Gilded Age. And she rightly pays special attention in these brief digressions into the suffering of the young women who powered so many of the wealth-generating factories owned by her subjects. But it’s not enough. Not nearly enough.

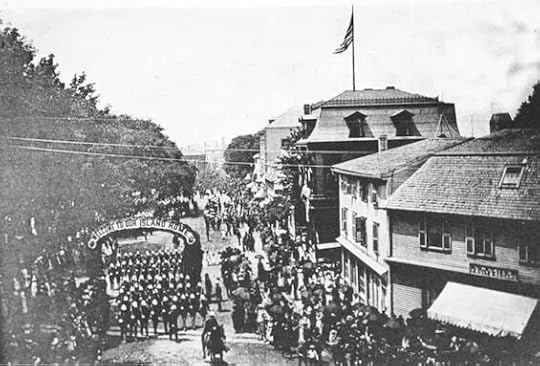

Newport, Rhode Island, in 1884 during a community “reunion.” The town was the site of Mamie Fish’s grandest exploits. Image: What’s Up NewpA kinder review of this book by artificial intelligence

Newport, Rhode Island, in 1884 during a community “reunion.” The town was the site of Mamie Fish’s grandest exploits. Image: What’s Up NewpA kinder review of this book by artificial intelligenceMost reviewers of Glitz, Glam, and a Damn Good Time were kinder than I was. That’s reflected in the following review by Claude-AI Sonnet 4, because it’s based on those other reviews as well as any available online summaries of the book. With the exception of one subhead I’ve inserted to break up the text, what follows is word-for-word what the AI wrote.

A Sparkling Biography of the Gilded Age’s Ultimate HostessJennifer Wright’s “Glitz, Glam, and a Damn Good Time: How Mamie Fish, Queen of the Gilded Age, Partied Her Way to Power” is a delightfully entertaining dive into the life of one of America’s most fascinating forgotten figures. Marion Graves Anthon Fish, known as “Mamie” and “The Fun-Maker,” threw the most epic parties in American history, and Wright brings her extraordinary story to vivid life.

Wright, acclaimed author of “Madame Restell” and “Get Well Soon,” demonstrates her signature ability to transform historical research into compulsively readable narrative. Rather than presenting Mamie Fish as merely a frivolous society hostess, Wright reveals how this remarkable woman wielded social gatherings as tools of influence and power during the Gilded Age. The book brilliantly illustrates how parties became political statements and how entertainment served as a form of female empowerment in an era when women had few other avenues to authority.

Witty, accessible proseWhat makes this biography particularly engaging is Wright’s witty, accessible prose that captures both the absurdity and the strategic brilliance of Fish’s approach to society. The author doesn’t shy away from the contradictions of the era—the extreme wealth alongside social inequality, the liberation and limitations faced by even privileged women. Through meticulous research, Wright paints a complex portrait of a woman who understood that in a world where she couldn’t vote or hold office, she could still shape society through her drawing room.

The book succeeds as both historical scholarship and pure entertainment. Wright’s narrative sparkles with the same energy that must have animated Fish’s legendary gatherings, making readers feel as though they’re receiving coveted invitations to the most exclusive parties of the 1890s. This is social history at its most engaging—serious enough to illuminate important themes about gender, power, and American society, yet light enough to be thoroughly enjoyable. Wright has crafted a biography that would make Mamie Fish herself proud: substantive, surprising, and undeniably fun.

About the author Jennifer Wright. Image: Audible

Jennifer Wright. Image: AudibleJennifer Wright, the political editor-at-large of Harper’s Bazaar. has written seven nonfiction books over the past decade. Born in 1986, she is a graduate of St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland. She is married and lives with her husband in New York.

For related readingFor additional insight into the Gilded Age, see:

The Tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J. P. Morgan Invented the American Supereconomy by Charles R. Morris (The Robber Barons who dominated the Gilded Age)The Murder of the Century: The Gilded Age Crime That Scandalized a City & Sparked the Tabloid Wars by Paul Collins (The Gilded Age murder that set off the tabloid wars)The Edge of Anarchy: The Railroad Barons, the Gilded Age, and the Greatest Labor Uprising in America by Jack Kelly (The American labor movement in the Gilded Age)You’ll find other sources of related information at:

12 great biographiesTop 20 popular books for understanding American history25 top nonfiction books about historyAnd you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post The outrageous woman who helped shape the Gilded Age appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

September 2, 2025

Politics and intrigue bedevil the police in Yeltsin’s Russia

From 1986 to 2001, the massive Russian space station Mir (“peace”) hurtled around the Earth at 17,000 miles per hour, circling the planet approximately every hour and a half. Usually, three cosmonauts lived aboard for periods lasting from several months to over a year. Cosmonaut Tsimion Vladovka and his two crewmates are eight months into their lives on board when one of them begins to act strangely. Then violence erupts, and officials in Star City send a three-person rescue mission to replace the crew. But no sooner are the rescued cosmonauts back on solid ground when one dies mysteriously. A second flees. And, when they return, the replacement crew are clearly in danger as well. Which opens up a case that lands on the desk of Chief Inspector Porfiry Rostnikov. His assignment: Tsimion Vladovka has disappeared, and he is to find him, dead or alive.

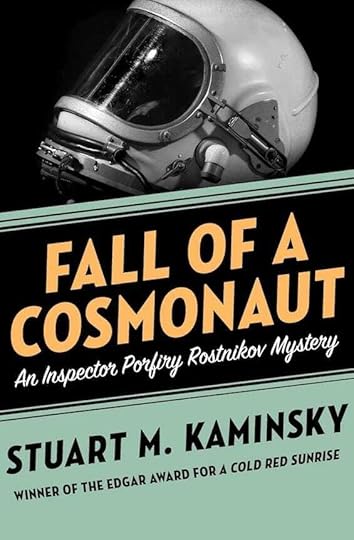

Three difficult cases in this police proceduralIn Fall of a Cosmonaut, the 13th in a series of Russian police procedurals by the late Stuart Kaminsky, Rostnikov’s search for Vladovka is one of three cases we follow. Igor Yakovlev (“the Yak”), chief of the Office of Special Investigation, has required Rostnikov to detail his colleagues to pursue other matters.

Emil Karpo (“the Vampire”) will get to the bottom of a blackmail scheme with political implications. Someone is holding hostage the original print of a forthcoming film biography of Leo Tolstoy, destined to be a classic and popular with the government. The intimidating Karpo will have the assistance of Akardy Zelach (“the Slouch”), whose nickname is also descriptive.And young Sasha Tkach and Elena Timofeyeva are to unravel what’s happening at the Center for the Study of Technical Parapsychology. There, someone has murdered a specialist in “telekinesis, dream states, several things.” Suspects abound.Meanwhile, Rostnikov (“the Washtub”), who resembles his nickname, will have the assistance of his son, Iosef, a former soldier and failed playwright who has joined the unit.Unlike most police procedurals, which focus the efforts of a large force of investigators on a single difficult case, Kaminsky uses this device of portraying Rostnikov and his colleagues as they engage in three separate investigations.

Fall of a Cosmonaut (Inspector Porfiry Rostnikov #13 of 16) by Stuart M. Kaminsky (2000) 340 pages ★★★★☆ The Russian space station Mir in 1998. Image: WikipediaRevealing what life in Russia is like in Yeltsin’s last years in power

The Russian space station Mir in 1998. Image: WikipediaRevealing what life in Russia is like in Yeltsin’s last years in powerRussia early in the 21st century has left behind the certainties and artificial shortages of the Communist era. Yet little has changed for the majority of the population. Most remain poor. Healthcare, no longer free, now depends on bribes. Doctors are poorly trained, underpaid, and often of little help to their patients. Life expectancy lags far behind that of Europe and the United States. The abundant brand-name goods on display in Moscow and other large cities are far out of reach for most Russians. And organized crime (the “Mafias”) runs rampant while the country’s biggest crooks, the oligarchs, dominate the central government.

In this grim setting, the Yak has engineered an agreement with Porfiry Rostnikov. The Chief Inspector will have a free hand to conduct investigations as he wishes, without interference. But, once concluded, the Yak will lay claim to the information he and his colleagues uncover and use it at his discretion. Which he puts to work in his never-ending quest for higher and more powerful posts in the Ministry of State Security. And Rostnikov’s current case, locating the missing cosmonaut, may turn up information that will vault the Yak to the very top, as Minister. Because whatever happened on that Russian space station represents a secret that the government cannot afford to admit. If only the Chief Inspector continues to play ball . . .

Three beguiling central charactersIn another significant way, the Porfiry Rostnikov mysteries do resemble other police procedurals. Kaminsky writes in the omniscient third person, taking us into the private lives and the minds of the people of the Office of Special Investigation. They’re all continuurng characters in the series, and over time—this novel is the 13th of 16 that Kaminsky wrote—we have gotten to know them all rather well. This is especially true in the case of the three central figures in the ongoing story.

Chief Inspector RostnikovNow past 50, Porfiry Rostnikov is a champion senior weightlifter. He lost the use of a leg as a child soldier in the Great Patriotic War and now wears a prosthesis. He is deeply in love with his wife of many years, Sarah, who is Jewish and whose religion has prevented him from rising any further in the Ministry. But the Chief Inspector’s neighbors know him best for his hobby as a plumber. He’s masterful with a wrench.

“The Vampire”Emil Karpo was for decades a deeply committed Communist. He has never reconciled himself to the fall of the state early in the decade. Humorless and unrelenting as an investigator, he strikes fear into most people merely at a glance. He maintains vast files of unsolved cases which he continues to work after hours. Somehow, though, he fell in love with a prostitute years earlier. Her death in a crossfire between two Mafias left him devastated and lonelier than ever.

The boyish inspectorSasha Tkach, now 34, continues to look far younger than his years. Tall, blond, and boyishly handsome, his philandering and repeated absences for him to do his duty undercover have driven his wife, Maya, to leave for her hometown, Kiev, with their two children. He misses them terribly, especially so as his insufferable mother has insisted on moving in with him. Life with her is torture, but he needs the money she has made as a businesswoman.

All the while the team pursues its various investigations, readers who follow the series continue to grow closer to these three unique individuals.

About the author Stuart Kaminsky. Image: Mysterious Press

Stuart Kaminsky. Image: Mysterious Press According to the popular website Book Series in Order, “Stuart M. Kaminsky was an American author best known for writing the Toby Peters series of detective novels, the Inspector Porfiry Petrovich Rostnikov series, the Abe Lieberman series, and the Lew Fonesca series. During his career, Stuart wrote sixty-three novels and eleven non-fiction books.” You can see all those books listed, with links, on the site.

Kaminsky (1934-2009) was a professor of film studies as well as a mystery writer. He was born in Chicago and educated at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, which granted him both a BS and an MA, and Northwestern University, where he earned a PhD in speech. Wikipedia notes that “Kaminsky and his wife, Enid Perll, moved to St. Louis, Missouri in March 2009 to await a liver transplant to treat the hepatitis he contracted as an army medic in the late 1950s in France. He suffered a stroke two days after their arrival in St. Louis, which made him ineligible for a transplant. He died on October 9, 2009.”

For related readingI’m reviewing this whole series in chronological order. You’ll find a guide to the series, as well as my reviews of the preceding 12 books, at Police procedurals spanning modern Russian history. And you’ll see this book in good company at The best police procedurals.

And check out Good books about Vladimir Putin, modern Russia and the Russian oligarchy and The best Russian mysteries and thrillers.

You’ll find other excellent crime stories at:

30 outstanding detective series from around the worldTop 10 mystery and thriller seriesTop 20 suspenseful detective novelsTop 10 historical mysteries and thrillersAnd you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post Politics and intrigue bedevil the police in Yeltsin’s Russia appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

September 1, 2025

What if Japan also had an atomic bomb in August 1945?

Anyone with a passing knowledge of World War II is aware that Germany attempted to build a nuclear weapon. What is less well known is that Japan did so, too. Both programs failed, the Japanese more quickly and decisively than the German. But at least one prominent US-trained Japanese nuclear physicist was involved. And his role is central in Samuel Hawley’s novel Daikon, his spellbinding alternate history of the final days of World War II.

A plan for mass suicideThe Japanese homeland was a shambles. Raids by American bombers had reduced 60 of its cities to rubble and ashes. In Tokyo alone, a single night’s raid on the night of 9-10 March 1945 by 279 Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers had killed 100,000 people. Almost all were civilians, and one million more became homeless. By early August, desperation reigned among the the populace. The politicians and some military officers were fed up. The nation was ready to call it quits. But the suicidal fanatics dominating the Japanese Army still held the reins of power. And they were preparing the population for mass suicide to resist the inevitable Allied invasion. However, defying the army, diplomats representing the civilian leadership were secretly negotiating the terms of surrender. And a military coup was in the offing. Japan’s fate hung in the balance.

Daikon by Samuel Hawley (2025) 352 pages ★★★★★ An iconic image of Hiroshima after the atomic bombing of August 7, 1945. Image: International Campaign Against Nuclear WarThe Hiroshima bombing goes awry

An iconic image of Hiroshima after the atomic bombing of August 7, 1945. Image: International Campaign Against Nuclear WarThe Hiroshima bombing goes awryAgainst this background, Samuel Hawley imagines a twist on the US plan to drop an atomic bomb on Hiroshima. With Col. Paul Tibbits confined to a hospital bed, his understudy leads a replacement crew on the first nuclear-armed mission. But on the approach to his target, a kamikaze fighter rams his aircraft. The B-29 goes down in flames over southern Japan and breaks up on the ground. “Little Boy,” the first atomic bomb designated for use in war, hurtles free of other wreckage and lies intact lodged in a hillside.

In short order, word of the enormous bomb reaches the desk of Lieutenant Colonel Shingen Sagara, head of the Defense Section of the Ordnance Bureau in Tokyo. Meanwhile, Navy Petty Officer Ryohei Yagi, head of the small team who discover the bomb on the ground, has cleverly run an experiment proving the super-heavy material inside the bomb is uranium. To confirm the finding, and manage the bomb’s retrieval, Col. Sagara enlists Dr. Keizo Kan. Leader of the Separation Team in Japan’s abortive effort to enrich uranium for use in a bomb of its own. Yagi calls it the Daikon because it resembles a giant radish.

One helluva taleYagi, Sagara, and Kan collaborate uneasily to ready the bomb for use on the enemy. Because Sagara believes that a powerful blow against the United States will strengthen the hand of the army leadership in Tokyo and prevent the surrender the civilian politicians are pushing for. And even though Kan is reluctant to contemplate mass murder, Sagara holds power over him. The physicist’s wife, Noriko, a Japanese American working for NHK as “Tokyo Rose,” has been arrested by the Tokkō “Thought Police.” And Sagara will obtain her release if Kan follows orders.

Hawley’s tale then follows Noriko and the three men as the date on Sagara’s planned attack on the US grows near. Complications develop right and left, and the suspense builds to a crescendo. This is one helluva tale.

A duplicate of the “Little Boy” atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima prepared for the US Air Force Museum. The aircraft in the back ground appears to be a B-29 Superfortress, possibly the “Enola Gay” that delivered the bomb over Japan. Image: US Air Force. Based on solid research

A duplicate of the “Little Boy” atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima prepared for the US Air Force Museum. The aircraft in the back ground appears to be a B-29 Superfortress, possibly the “Enola Gay” that delivered the bomb over Japan. Image: US Air Force. Based on solid researchIn a fascinating author’s note at the conclusion, Hawley describes the factual basis, and the real-life figures, on which he based the novel. For example, “The character of Dr. Keizo Kan is loosely based on three men involved in Japan’s atomic bomb program, Project Ni-Go.” And “Petty Officer Ryohei Yagi was inspired by a real person: Japanese actor Toshiro Mifune. It is not widely known, but Mifune served for six years in the Japanese army. He was drafted in 1939 in Manchuria, where he was born and grew up.”

Hawley’s character, Petty Office Yagi, is in reality Korean, as he discloses in the story. Hawley chose this detail because he himself was born and grew up there. He has written three books about Korean history. And, to judge from the text of the novel, he is at least familiar with the Japanese language if not a fluent speaker. Furthermore, he cites a long list of memoirs, reports, and other nonfiction books as his sources for the period detail in his story. It’s an impressive display for a novelist.

The formal surrender of Japan: While dozens of Allied leaders look on, Japanese Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu signs the Instrument of Surrender aboard the USS Missouri anchored in Tokyo Bay. Image: US Army – US Naval InstituteAn AI reviews the novel

The formal surrender of Japan: While dozens of Allied leaders look on, Japanese Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu signs the Instrument of Surrender aboard the USS Missouri anchored in Tokyo Bay. Image: US Army – US Naval InstituteAn AI reviews the novelFor a broader perspective, I asked Claude-AI Sonnet 4 to write 300 words reviewing this novel. Drawing from numerous sources online, the following was the result. You’ll find in it a more in-depth picture of the story. It includes many key details that my own review above doesn’t mention. The text is word-for-word except for the subheads I inserted to break up the text and make it easier to read.

A man stripped of everything preciousSamuel Hawley’s debut novel “Daikon” is a masterful work of alternative historical fiction that reimagines the final days of World War II with devastating emotional impact. The result of twenty-seven years of meticulous craftsmanship, this gripping narrative presents a chilling “what if” scenario: what would have happened if a third atomic bomb had fallen into Japanese hands?

At the heart of this epic lies physicist Keizo Kan, a man stripped of everything precious by war—his daughter killed in the Great Tokyo Air Raid, his Japanese-American wife Noriko imprisoned by the Thought Police. When tasked with examining an unexploded uranium device recovered from a downed American bomber, Kan faces an impossible bargain: unlock the bomb’s secrets to secure his wife’s freedom, knowing it could prolong the devastating conflict.

Hawley’s background as a longtime resident of Korea and Japan, combined with his extensive research, creates an authentically immersive portrayal of wartime Japan. The author skillfully avoids cultural stereotypes while depicting the complex tensions within Japanese leadership between hardliners and those advocating surrender. His technical descriptions of the bomb’s mechanics feel both scientifically grounded and dramatically compelling.

Excels in its moral complexityThe novel excels in its moral complexity, forcing readers to grapple with agonizing ethical dilemmas alongside its protagonist. As Kan witnesses his assistant’s radiation sickness and experiences his own symptoms, the human cost of nuclear warfare becomes viscerally real. The mounting pressure from military commanders creates a ticking-clock tension that builds to a pulse-pounding climax.

“Daikon” stands among the finest World War II fiction, earning comparisons to classics like “Cold Mountain.” Hawley has crafted a haunting meditation on love, loyalty, and the impossible choices war demands, introducing a singular new voice to contemporary literature. This extraordinary debut proves that some stories are worth decades of patient development.

About the author Samuel Hawley. Image: Audible

Samuel Hawley. Image: AudibleSamuel Hawley’s publisher, Simon & Schuster, writes that “Samuel Hawley was born and raised in South Korea, the son of Canadian missionaries, and taught English in Korea and Japan for nearly two decades. He is the author of the nonfiction book The Imjin War, the most comprehensive account in English of Japan’s 16th-century invasion of Korea and attempted conquest of China. He currently lives in Istanbul, Turkey. Daikon is his debut novel.” However, Amazon credits Hawley with one earlier novel and half a dozen nonfiction books. Hawley’s own website lists the same books and adds, “Samuel Hawley is a Canadian writer with BA and MA degrees in history from Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario.”

For related readingFor other excellent examples of alternative history, see Great alternate history novels.

And you’ll find top-notch science fiction novels at:

These novels won both Hugo and Nebula AwardsThe ultimate guide to the all-time best science fiction novelsThe top science fiction novelsThe top 10 dystopian novelsAnd you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post What if Japan also had an atomic bomb in August 1945? appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

August 28, 2025

How Iran came to be America’s bitterest enemy

When future historians tally the most consequential revolutionary movements of the modern era, the choices will be obvious. The Russian Revolution re-set the balance of power almost throughout the 20th century. In China, the Communists set the world’s most populous nation on a dramatic new course, leaving it poised to dominate the 21st century. And the Iranian Revolution unleashed a global wave of radical religious movements that have bedeviled the world ever since 1979. That epic event also installed a regime that ever since has been America’s bitterest enemy. The stories of those transformations in Russia and China are well known. But the Iranian picture is far less clear to Americans. In King of Kings, veteran journalist Scott Anderson offers a remedy in his dazzling account of Iran’s trajectory from the American-led coup in 1953 to the cataclysmic events of 1979.

The Iranian Revolution did not have to happenIt’s difficult not to conclude after reading King of Kings that the Iranian Revolution wasn’t inevitable—at least in its now-familiar theocratic form. Even given the 1953 coup that ousted Iran’s elected government and restored Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (1919-80) as Shah, or King, that course might have been averted. And, as Anderson makes clear, the fault mostly lies in the US government. He charges our country’s decision-makers in the 1960s and 70s with “hubris, delusion and catastrophic miscalculation.”

The Shah himself shared those faults. But the United States wielded so much power that we could have ensured the pliable monarch took a more measured course. Had he done so, the Ayatollah Ruholla Khomeini (1900-89), the unhinged fanatic who spearheaded the Revolution, might have been sidelined with ease.

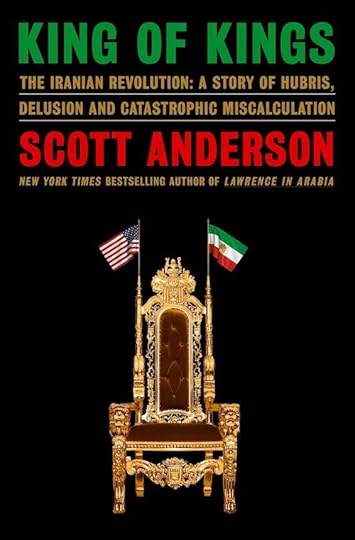

King of Kings: The Iranian Revolution: A Story of Hubris, Delusion and Catastrophic Miscalculation by Scott Anderson (2025) 746 pages ★★★★★ Mass demonstrations of people protesting against the Shah and the Pahlavi government in December 1978. Image: WikipediaThe book’s key sources were close to the action

Mass demonstrations of people protesting against the Shah and the Pahlavi government in December 1978. Image: WikipediaThe book’s key sources were close to the actionScott Anderson is an accomplished investigative journalist. He does his homework. And in writing King of Kings he delved deeply into the available record, often newly opened, and interviewed several of the key figures in his story, including the Shah’s third and last wife, Empress Farah Pahlavi. The result is a story that comes to life with immediacy, revealing the passions, fears, and miscalculations that triggered the Iranian Revolution.

Much of Anderson’s story rests on the testimony or written records of four key individuals:

A former Peace Corps VolunteerForeign Service Political Officer Michael Metrinko (1946-) was U.S. Consul-General in Tabriz, where some of the signature events of the Revolution transpired. Metrinko was a former Peace Corps Volunteer who had served both in Iran and in Turkey and spoke both Farsi and Turkish. In this he was nearly unique among State Department officials. Metrinko was serving in Tehran and became a hostage when Iranian students overran the US Embassy. He resisted his captors so persistently that he spent much of the time in solitary confinement.

The Iran desk officer(1931-2022), who was the State Department’s Iran Desk Officer from 1978 to 1981. Anderson paints him as one of the earliest and most assertive skeptics of the Shah’s ability to stay in power. However, he was unable to persuade many of his colleagues despite the fact that he was the department’s principal Iran expert.

The President’s designated Iran specialistGary Sick (1935-) was the National Security Council (NSC) officer handling Iran affairs in 1978 during the Carter administration. Like his counterpart at the State Department, Henry Precht, he appreciated far earlier than others the weakness of the Iranian regime. However, his boss, the National Security Advisor, was an aggressive advocate for the Shah until the very end.

The empressFarah Pahlavi (1938-), empress of Iran (Shahbanou), the shah’s third and last wife, struggled to moderate her husband’s impulsive and highly questionable decisions over the years. (They were married from 1959 to 1980.) He almost always disregarded her—and just about everybody else, for that matter.

Anderson’s account also rests on extensive records of several men who served the shah as prime minister or in other key positions. Their unfamiliar names blend into the woodwork. In addition, he gained access to several US and Iranian military officers who played significant roles in the final, tumultuous days of the regime.

His Imperial Majesty Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi Shahanshah Of Iran, KIng of Kings. Image: Queen Farah PahlaviThe US officials who bear the greatest responsibility for the debacle

His Imperial Majesty Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi Shahanshah Of Iran, KIng of Kings. Image: Queen Farah PahlaviThe US officials who bear the greatest responsibility for the debacleAnderson paints a sad picture of high-level American decision-making during the critical years of 1978 and 1979. The story he tells lays much of the blame at the feet of three men:

President Jimmy CarterJimmy Carter (1924-2024) was President during the Iranian Revolution. He bears ultimate responsibility for the catastrophic failure of the US relationship with imperial Iran. Long after there was abundant evidence that the shah’s regime was on its last legs, Carter continued to praise and support the man. And his decision to admit the shah to the United States for medical treatment in 1979 enraged Iranian opinion and led to the hostage crisis.

National Security Advisor Zbigniew BrzesinskiCarter’s powerful National Security Advisor from 1977 to 1981, Zbigniew Brzezinski (1928-2017) suppressed every attempt from his subordinates or from the State Department to question the wisdom of US policy toward Iran. Like most American officials, he believed that Iran, with its massive oil revenues and military power—the fifth largest army in the world—was invincible. None of them understood the appeal or the power of the ayatollahs’s message.

Ambassador Willian SullivanVeteran State Department diplomat William Sullivan (1922-2013) served as US Ambassador to Iran from 1977 to 1979. Like Brzezinski, he was an outspoken advocate of the shah and remained close to him throughout his posting in the country. However, unlike the National Security Advisor, he came to realize that the regime’s days were numbered and toward the end he attempted for months, in vain, to persuade the shah to leave Iran. His doing so might have opened an opportunity for moderate forces among those pressing for change to gain the upper hand. Delaying as long as he did instead ensured the ascendancy of Ayatollah Khomeini.

Richard Nixon and Henry KissingerAlthough they were not involved in the events of 1978 and 1979, President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger bear some measure of responsibility for the debacle, too. Early in the decade they forged an agreement with the shah to permit him to buy any and all arms from the United States with no questions asked. This agreement tied the hands of officials who later sought to raise concerns about the wastefulness of the purchases or the questionable ways that US armaments were used in suppressing resistance among the Iranian people.

About the author Scott Anderson. Image: Pulitzer Center

Scott Anderson. Image: Pulitzer CenterScott Anderson, formerly a war correspondent for the Associated Press, the New York Times, and Harper’s Magazine, is the author of eight notable works of nonfiction as well as two novels. He was born in California in 1959 but grew up in East Asia where his father was a US government agricultural advisor. He holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Iowa Writer’s Workshop. His brother Jon Lee Anderson is also an accomplished writer. The two co-authored two nonfiction books. Anderson currently lives in Brooklyn, New York, with his wife and daughter.

For related readingI’ve also reviewed two other excellent books by the author:

The Quiet Americans: Four CIA Spies at the Dawn of the Cold War (How the CIA helped set the course for a half-century of US policy)Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East (Was Lawrence of Arabia the man you thought he was?)For related subjects, see:

Top nonfiction books about national security12 great biographiesBest books about the CIA30 good nonfiction books about espionageTop 20 popular books for understanding American historyAnd you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post How Iran came to be America’s bitterest enemy appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

August 27, 2025

A British historian questions why the Allies won World War II

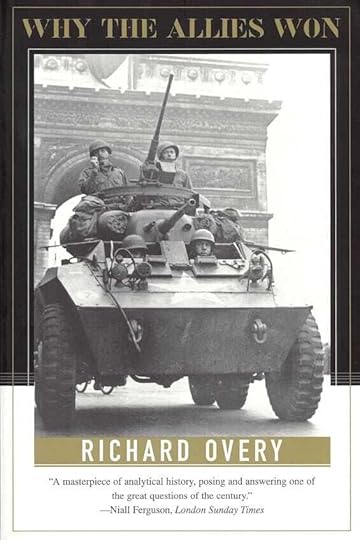

Brace yourself. Much of what you believe about why the Allies won World War II may not be true. British historian Richard Overy challenges the received wisdom in his eye-opening revisionist interpretation of the six-year ordeal, titled simply Why the Allies Won.

For most historians, that question makes little sense. The accepted understanding among them is that two reasons stand out. First, Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union collectively mustered manpower and resources far in excess of Axis capabilities. And, second, the Nazis made the tragic error of entering into a two-front war confronting both the West and the USSR. But Overy drills down into the history of the period, arguing the reality was not so simple. He raises penetrating questions about both assumptions in this extraordinary book. It’s one of the most revealing accounts of the war I’ve ever encountered.

Not a comprehensive accountOvery’s book is not a retelling of World War II history. His arguments apply largely to the European conflict and not the equally momentous war in China and the Pacific. (There, the consensus is that Imperial Japan made the fatal error of taking on the United States and overextended itself in the vastness of the Chinese mainland.) Nor does Overy address critical topics such as the impact of intelligence, which he thinks is overestimated.

Why the Allies Won by Richard Overy (1995) 406 pages ★★★★★ Sometime in the Autumn of 1942, Soviet soldiers advance through the rubble of Stalingrad. Victory there is one of the signal events analyzed by Richard Overy in this book. Image: Georgy Zelma/Waralbum.ru – The AtlanticDebunking the conventional wisdom

Sometime in the Autumn of 1942, Soviet soldiers advance through the rubble of Stalingrad. Victory there is one of the signal events analyzed by Richard Overy in this book. Image: Georgy Zelma/Waralbum.ru – The AtlanticDebunking the conventional wisdomOvery easily dismisses the assertion that the Allies won because they possessed superior resources. In fact, it was not until midway through the war in Europe that US industrial capacity came into its own, turning out hundreds of thousands of aircraft, tanks, and trucks like so many widgets. Before then, the industrial resources available to Germany at home and in the nations it occupied greatly exceeded what Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States could bring to bear. Even then, Germany did have the capacity to produce far more weaponry and munitions than it did. But the Allies learned to mobilize and organize their economic potential more effectively than the Axis powers. Overy argues that raw resources alone weren’t decisive. It was differences in their ability to convert economic strength into military power with efficiency.

The author gives equally short shrift to the argument that when Germany elected to fight a two-front war the die was cast. Overy cites numerous examples from history, and from that of World War II itself, to debunk this claim. In fact, the US was fighting a three-front war beginning in November 1942, when British and American troops landed in North Africa in Operation Torch. Again and again history shows that fighting a two-front war has little bearing on the outcome.

The six reasons why the Allies won World War II?Overy’s argument boils down to six principal factors:

Mobilizing and organizing industrial resourcesAs suggested above, the Allies won in part because they were more successful in mobilizing and organizing the industrial resources available to them, not because they simply had more available. That wasn’t even the case until 1943. Hitler had conquered most of Continental Europe with its massive industrial capacity. But as the war dragged on, the Allies produced more and more weapons and munitions than the Axis. By contrast, the output of war materiel in Germany, Japan, and Italy steadily declined beginning in 1943. And while Germany poured precious resources into the development of advanced weaponry such as jet aircraft and ballistic missiles, the Allies focused on the technology that truly sustained the war effort: airplanes, tanks, and trucks.

Capitalizing on scientific research and developmentDespite Germany’s long preeminence in science and technology, the Allies simply did a better job managing the application of scientific research and development. Although beginning with a deficit in such technologies as radar and submarine design, the Allies steadily gained an advantage in such fields as radar and code-breaking. And they proved adept in directing the efforts of private industry in the US and Britain and the economy at large in the USSR toward continuous improvement into the most fundamental tools of war: ships, planes, tanks, and trucks.

Building an effective coalitionThe Allied coalition triumphed because its principals—Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union—worked together more successfully than did the Axis nations. Even the Western powers’s relationship with the USSR, which was at best distant early in the war, became cooperative beginning with the Normandy Invasion. Meanwhile, the US and Britain, however tense their relations from time to time, successfully coordinated their military activities. The Axis powers never truly formed a coalition. They were on their own from the start.

Evolving tactics and strategyAllied military leadership proved far more flexible than that of the Axis powers. While Germany persisted in the tactics that gained them such a rapid initial advantage, shifting its approach only after its loss at Stalingrad, Allied strategy and tactics steadily evolved and adapted to meet new circumstances. This flexibility proved significant especially in such areas as combined arms tactics, amphibious warfare, and strategic bombing.

Superior leadershipAllied political and military leadership proved superior to that of the Axis. In Japan, right-wing military fanatics dictated policy until the closing days of the war, abetted by a willing emperor. And Hitler proved again and again the folly of his insistence on personally running the war. In both nations, the leadership’s insistence on fighting to the death hobbled its commanders in the field. Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin all demonstrated their willingness to delegate military decision-making to professional soldiers, who made no such mistake. None of the three was perfect. Far from it. But they all proved flexible and pragmatic.

A moral advantageThe Allies gained a moral advantage as the volume of reports about Axis atrocities mounted through the years. They developed greater resilience and commitment as the war progressed. Strong morale among the British, Soviet, and American public through much of the war bolstered their governments’s pursuit of unconditional surrender.

About the author Richard Overy lecturing in 2015. Image: Wikipedia

Richard Overy lecturing in 2015. Image: WikipediaRichard Overy is a Cambridge-educated British historian who has written extensively about World War II, Nazi Germany, and military history. He taught history at Cambridge, King’s College London, and the University of Exeter. He has written 33 books to date but is best known for Why the Allies Won.

For related readingYou’ll find other enlightening books about the war at the following pages. Most rely on a more conventional view of the war, including my own “7 misconceptions.”

10 top nonfiction books about World War II10 top WWII books about espionageGood books about the Holocaust25 top nonfiction books about history7 common misconceptions about World War IIThe 10 most consequential events of World War IIAnd you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post A British historian questions why the Allies won World War II appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

August 26, 2025

Politics intrudes as Inspector Chen investigates corruption

No large institution is free of corruption. The temptation to gain personal wealth or power is too great for some individuals to ignore. Of course, the incidence of self-dealing may be lower in business organizations engaged in fierce competition. Corruption adds costs that top executives are usually inclined to eliminate. The same may be true in democratic institutions where checks and balances abound. But in any one-party system, endemic corruption is inevitable. The histories of Russia, India, Mexico—and China—bear out this truth. And Chinese corruption is especially dramatic. Today, President Xi Jinping confronts it at every turn, no matter how many “anti-corruption” campaigns he may mount. Widespread corruption, from the very top to the village level, has been a reality in China for centuries. And the Chinese American author Qiu Xiaolong explores that theme as it appeared early in this century in Enigma of China.

A special assignment to cover up a murderThe novel is the eighth in Qiu’s long-running series of detective tales featuring Chief Inspector Chen Cao of the Shanghai Police Bureau. Chen is a “rising Party cadre” who heads the Special Cases Squad organized to tackle the most politically sensitive investigations. But in Enigma of China, Chen has been elevated to the position of Deputy Secretary of the Communist Party in the police bureau. His friend and assistant, Detective Yu, now effectively runs the day-to-day operations while Chen deals with the challenges thrown his way by his superior, Party Secretary Li Guohua, or his influential patron in Beijing.

This time it’s Li who orders Chen to take on an unusual assignment. He is to serve as a “consultant” to the homicide Detective Wei on an investigation into the death of Zhou Keng, a senior city official in a five-star hotel room. The hidden agenda: Wei and Chen are ordered to conclude that Zhou died a suicide, no matter what the evidence might show. Except that such direction runs counter to Chen’s nature—and to Wei’s as well.

Enigma of China (Inspector Chen Cao #8) by Qiu Xiaolong (2013) 288 pages ★★★★☆ Scenes like this are common in every large Chinese city. And projects like this are the root of the overheating in the country’s housing market . . . and a source of corruption like that brought to light in Qiu Xiaolong’s novel. Image: Wired A dangerous investigation that may turn deadly

Scenes like this are common in every large Chinese city. And projects like this are the root of the overheating in the country’s housing market . . . and a source of corruption like that brought to light in Qiu Xiaolong’s novel. Image: Wired A dangerous investigation that may turn deadlyAs Wei has learned from the city officials who have rushed to the hotel to investigate, Zhou Keng was the director of the Shanghai Housing Development Committee. “About two weeks ago,” Wei explains to Chen, “he was targeted in a ‘human-flesh search,’ or crowd-sourced investigation, on the Internet. As a result, a number of his corrupt practices were exposed. Zhou was then shuangguied and kept at the hotel, where he hanged himself last night.” (Shuanggui is a sort of extralegal detention by Party disciplinary bodies. When we read of high officials who have disappeared in corruption investigations, they’ve been shuangguied.)

However, the way that “human-fleshed search” got started is the central mystery in the novel. Someone had sent a photograph of a pack of cigarettes on a table in front of Zhou to a blogger the government considered a troublemaker. That pack of cigarettes was of a brand available only to the highest officials in China, who live inside the Forbidden City in Beijing. Which suggests to the blogger some sort of corrupt relationship. That photo could only have come from Zhou’s computer. But who could have sent it to the blogger?

Naturally, evidence turns up that Zhou was in fact murdered. Either Zhou himself, or someone else, had administered a large dose of sedatives, the autopsy reveals. However, high-ranking officials from both the city and from Beijing descend on the hotel in an effort to ensure that the verdict is suicide nonetheless. Soon, it’s clear that Wei and possibly Chen as well are risking their lives if they continue their investigation.

Warning: this book ends on a cliffhanger. It will leave you with a vivid sense of the uncertainty that reigns in China today.

About the author Qiu Xiaolong in an unidentified Chinese city. Image: Washington University

Qiu Xiaolong in an unidentified Chinese city. Image: Washington UniversityFor a biographical portrait of the author, see “Qiu Xiaolong and the Chinese Enigma” by Caroline Cummins in January Magazine. Or check out any of my reviews of the previous seven novels in this series. (They’re linked below.)

For related readingI’ve also reviewed all seven of the previous books in this series:

Death of a Red Heroine (A gripping Chinese police procedural)When Red Is Black (This gripping crime novel shows China in transition)A Case of Two Cities (A detective investigates corruption in the Chinese Communist Party)A Loyal Character Dancer (In a Chinese murder mystery, the legacy of the Cultural Revolution looms large)Red Mandarin Dress (As China changes, a serial murder case challenges the police and the Party) The Mao Case (Hunting the ghost of Mao Zedong in 1990s Shanghai)Don’t Cry, Tai Lake (Inspector Chen confronts environmental crime in a Chinese city)Check out The best mystery series set in Asia, 30 insightful books about China, and The best police procedurals.

And you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post Politics intrudes as Inspector Chen investigates corruption appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

August 20, 2025

During that fateful year when Abraham Lincoln saved the Union

Today we speak of “the imperial presidency” to reflect the staggering breadth of the power that the White House has amassed over the past century. And the term is more apt than ever today under the expansive view of presidential power that has motivated the Roberts Supreme Court to abet its further spread. But a century and a half ago, when Abraham Lincoln moved into the Executive Mansion, he confronted an array of challenges that overwhelmed the meager tools at his disposal to meet them. Yet four years later, after Lincoln fell to an assassin’s bullet, he had somehow taken on those challenges and subdued them—and the office he’d held had gained immeasurably in stature. Most of the most consequential events that produced this change took place in the year 1862, and the historian David Von Drehle brilliantly tells the story of Lincoln’s Rise to Greatness.

The challenges Lincoln faced on New Year’s day 1862No American President, not even George Washington or Franklin D. Roosevelt, has encountered a more daunting set of challenges than did Abraham Lincoln as the year 1862 dawned. The U.S. Treasury was broke. The Union’s top general, Winfield Scott, was gravely ill. His War Department was corrupt and dysfunctional. Britain and France threatened to side with the Confederacy. His unstable and demanding wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, was embezzling government funds. Critics abounded, accusing him of incompetence. And Congress, his generals, his cabinet, and the Radical Republican abolitionists who dominated his party made conflicting demands on him. In Rise to Greatness, Von Drehle recounts Lincoln’s steady course through a perilous year as he led the republic to the cusp of victory—and the Emancipation Proclamation—precisely one year later.

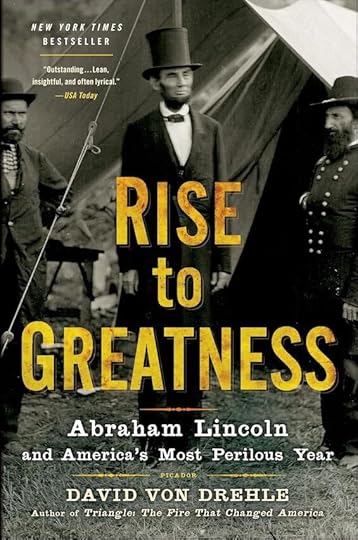

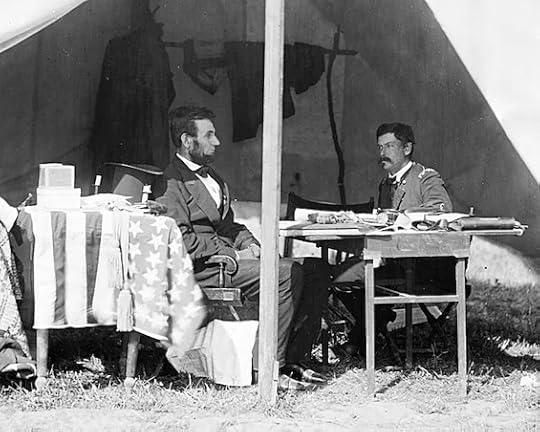

Rise to Greatness: Abraham Lincoln and America’s Most Perilous Year by David Von Drehle (2012) 492 pages ★★★★★ In a famous photo, Lincoln and McClellan confer during the President’s visit to the Army of the Potomac in October 1862. Image: Emerging Civil WarTwo men at loggerheads stymied Union action

In a famous photo, Lincoln and McClellan confer during the President’s visit to the Army of the Potomac in October 1862. Image: Emerging Civil WarTwo men at loggerheads stymied Union actionIf Rise to Greatness were a novel, the protagonists would be Abraham Lincoln and General George B. McClellan. And the president could hardly have faced a more problematic foe.

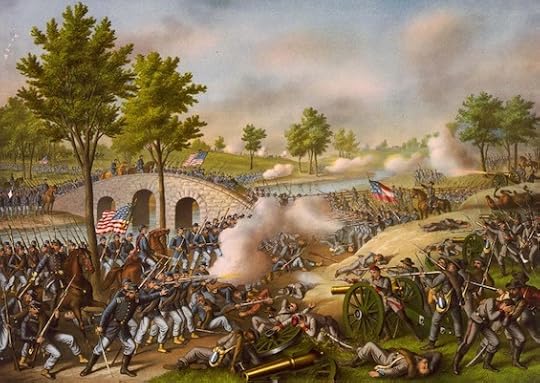

Known as “Little Mac” or “Young Napoleon” for his short stature, the commander of the Army of the Potomac was the president’s nemesis. He refused to lead his troops into battle for months on end, constantly demanding reinforcements to match the wildly inflated numbers of Confederate troops he claimed to face. He was a West Point graduate who disparaged Lincoln’s military advice even after the president had studied the art and science of war in depth and was at least the general’s equal in both strategy and tactics.McClellan had no respect either for Lincoln personally or for the office he held. He refused to inform him about either his plans or the state of the battlefield, refusing week after week to communicate with what was then called the Presidential Mansion. But, most tellingly, McClellan was a Democrat, loyal to the Union but sympathetic to the South and a fierce opponent of emancipation. Von Drehle implies that McClellan deliberately held back his troops from taking the initiative when resolute action might have destroyed Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. McClellan favored an accommodation with the Confederacy that would preserve both the Union and slavery.Just for exampleConsider “Little Mac’s” frame of mind before the massive battle of Antietam in September 1962. His Army of the Potomac numbered 90,000 troops in active service. By contrast, Lee could count on about 30,000. But McClellan insisted he was badly outnumbered and, as always, called for reinforcements before he could move forward. As Von Drehle observes, “Victory lay before his eyes, but all he saw was disaster.” And this was but one example of the general’s endless foot-dragging.

So, why didn’t Lincoln fire the man?Despite all this, Lincoln was unable to fire McClellan until nearly the end of the year. The general was the darling of the Unionist Democrats who held the balance of power in several states. Though not a fighting general, he was a genius at organization, training, and logistics. His troops loved him and might mutiny—or stage a military coup—if the president dismissed him. The unpopular president’s hands were tied until McClellan’s obduracy finally became obvious even to many of his supporters.

Confederate dead by a fence on the Hagerstown road, Antietam, Maryland, in September 1862. Image: Alexander Gardner – BritannicaA momentous year by any measure

Confederate dead by a fence on the Hagerstown road, Antietam, Maryland, in September 1862. Image: Alexander Gardner – BritannicaA momentous year by any measureAlthough the rivalry between Lincoln and McClellan runs like a thread through Von Drehle’s account, the book abounds with other significant characters. The leading members of his Cabinet—his “Team of Rivals,” to use Doris Kearns Goodwin’s famous phrase—loom large in the story. Secretary of State William H. Seward, a former Whig and moderate Republican like Lincoln himself. Salmon P. Chase, the Secretary of the Treasury, detested Seward and fed negative and often manufactured information about him to his enemies in Congress. Edward Bates, the Attorney General, the most conservative member of the group who prevented it from reaching unanimity on important issues. And, among still others, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, whose respect for Lincoln grew steadily through the year.

A banner year for CongressBut some of the most significant events of the year 1862 took place not within the Administration but in Congress. Ever since the days of Andrew Jackson, momentum had built behind a set of nation-building measures that would ensure the growth of the United States into a world power. But the weight of conservative Southerners in Congress prevented the advocates—first, the Whigs, then the Republicans—from garnering the necessary votes. Secession changed that. And a flood of major legislation issued forth from Capitol Hill. These actions included:

The Homestead Act, which provided land to settlers in the WestThe Pacific Railway Acts, supporting the construction of the transcontinental railroadA major move toward emancipation with the Second Confiscation Act, which declared free the slaves of those found guilty of engaging in rebellion against the UnionAnd the Morrill Land-Grant Act that established land-grant colleges later numbering more than 100 and including such institutions as the University of California, Berkeley, Cornell University, and Texas A&M University.Von Drehle doesn’t single out the legislators most responsible for these bills. His focus remains squarely on Lincoln. But, Lincoln did sign all this legislation.

About the author David Von Drehle in 2023. Image: Jeremy Theron Kirby – Kansas City Magazine

David Von Drehle in 2023. Image: Jeremy Theron Kirby – Kansas City MagazineThe American journalist and author David Von Drehle was born in Denver, Colorado, in 1961. With a BA from the University of Denver, he earned a Master of Letters from the University of Oxford. A former sports writer for the Denver Post and the Miami Herald, he later served as the New York bureau chief for the Washington Post and as an Editor-at-Large for Time. He is now an opinion columnist for the Washington Post. Von Drehle is the award-winning author of five nonfiction books.

For related readingYou’ll find other enlightening books on similar themes at:

12 great biographiesTop 20 popular books for understanding American historyTop 10 nonfiction books about politicsAnd you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post During that fateful year when Abraham Lincoln saved the Union appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

August 19, 2025

Taking down a sinister Right-Wing militia

John Sandford has been writing bestselling crime novels since 1989. Three dozen chronicle the amazing career of Lucas Davenport in law enforcement, a tech millionaire who began on the Minneapolis police, continued as a top executive in the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, and then moved to the US Marshals Service. Along the way, he and his neurosurgeon wife adopted a 12-year-old girl named Letty whose parents had died in a confrontation with Davenport. Now, a dozen years later, Letty Davenport has herself taken a job with the Department of Homeland Security. In The Investigator, Sandford reveals the young woman to be a force to rival her adoptive father as she takes on a powerful Right-Wing conspiracy.

A young investigator and her opposite heading a gang of craziesSandford writes in the omniscient third person, seamlessly shifting from Letty’s perspective to that of John Kaiser, her older, ex-Delta Force partner, to Jane Jael Hawkes, the leader of the Right-Wing crazies and criminals in a militia that calls itself the Land Division. The effect is to place two women, Hawkes (who goes by Jael) and Letty at the opposite poles of the story.

It all begins when Letty, employed as an off-the-books investigator by Senator Christopher Colles (R-Florida), returns to him after successfully uncovering those responsible for the theft of $300,000 in his campaign funds. Then the senator inserts her in the Department of Homeland Security to bird-dog an investigation as a “researcher” after she quits her job working directly for him. (It’s boring, she tells him.) That leads her to a partnership with Kaiser and sets up the standoff with Jael.

The Investigator (Letty Davenport #1) by John Sandford (2022) 400 pages ★★★★★ Members of a Right-Wing militia like those in the formidable force confronting Letty Davenport and her partner in The Investigator. Image: Seth Herald – The New YorkerNot-quite polar opposites

Members of a Right-Wing militia like those in the formidable force confronting Letty Davenport and her partner in The Investigator. Image: Seth Herald – The New YorkerNot-quite polar oppositesTwenty-four-year-old Letty Davenport spent the first half of her young life living in extreme deprivation with an alcoholic mother and a violent father. Jael Hawkes’s experience is not much different. But their circumstances changed radically when Lucas Davenport adopted Letty at age 12. Now, Jael runs a small gang of violent miscreants, several of them ex-cons, in a delusional quest to stop the flood of migrants across the Southern border. But Letty is ignorant of Jael’s elaborate plan, or its nationwide dimensions, until nearly halfway through the story.

She and Kaiser are detailed to Texas to investigate the disappearance of small quantities of oil fresh from the wells. It turns out that, though the individual thefts are tiny, collectively they amount to the loss of millions of dollars a year in revenue for the oil companies. But DHS isn’t concerned about the thefts in themselves. The companies earn billions and can easily afford the loss. Instead, the Department wonders what all that money is being used for. And therein lie the roots of the standoff between Letty and Jael.

What drives Right-Wing militias?I read a lot of news, so I’m quite well aware of the various justifications that Right-Wing militia members advance for their sociopathic stance. And I know, as you’re likely to be aware, that the belief system driving Jael Hawkes reflects only one aspect of the prevailing militia ideology. There is a much broader set of motives behind the phenomenon. But I would be hard-pressed to sum up those motives in a relatively few words. So I asked Claude-AI Sonnet 4 to do it for me in about 300 words. The result follows, unchanged in any way except that I’ve inserted subheads to make the text more readable. I can find nothing in this analysis to raise questions about its accuracy.

A set of interlocking motivesRight-wing militias in the United States are driven by several interconnected motives that reflect broader ideological and cultural tensions within American society.

Anti-Government Sentiment forms a core motivation, with many militia members viewing the federal government as an overreaching entity that threatens individual liberty and constitutional rights. This distrust often stems from specific incidents like Ruby Ridge (1992) and Waco (1993), which galvanized perceptions of government tyranny. Members frequently cite concerns about gun control measures, federal regulations, and what they perceive as unconstitutional expansions of federal power.

Constitutional Fundamentalism drives many participants, particularly their interpretation of the Second Amendment as guaranteeing not just individual gun rights but a collective right to armed resistance against tyrannical government. They often view themselves as modern-day minutemen, prepared to defend constitutional principles through force if necessary.

On a more personal levelRacial and Cultural Anxieties significantly motivate some militia groups, particularly fears about demographic changes, immigration, and multiculturalism. These concerns often manifest as beliefs in “white genocide” theories or fears that traditional American culture is under threat. Some groups explicitly embrace white nationalist ideologies, while others frame their concerns in terms of preserving “American values.”

Economic Displacement and rural decline contribute to militia appeal, as members often come from economically struggling communities that feel abandoned by mainstream political institutions. The loss of manufacturing jobs, farm consolidation, and urban-rural cultural divides create fertile ground for anti-establishment movements.

Conspiracy theories aboundApocalyptic Beliefs and conspiracy theories also play important roles, with some militia members subscribing to theories about New World Order plots, deep state conspiracies, or impending societal collapse. These beliefs create urgency around preparedness and armed resistance.

Community and Identity provide powerful draws, as militias offer belonging, purpose, and masculine identity in communities where traditional sources of meaning may have eroded. The combination of ideological conviction, social bonds, and perceived existential threats creates a potent motivational framework that sustains these movements despite legal risks and social stigma.

I would defy anyone to write a more cogent and comprehensive account than this.

About the author John Sandford. Image: Amazon

John Sandford. Image: AmazonJohn Sandford, the pen name of John Roswell Camp, is a New York Times best-selling author of crime novels, former journalist, and recipient of the Pulitzer Prize. He earned both a bachelor’s degree in American history and literature and a master’s in journalism from the University of Iowa. He worked as a journalist for nearly two decades before publishing two novels, each of which inaugurated a popular series. One was his long-running Prey series featuring Lucas Davenport, Letty’s adoptive father. Sandford has written 40 Prey books, a dozen in the spinoff Virgil Flowers series, a dozen other novels, and two works of nonfiction. Sandford, born in 1944, has been married twice. He lives with his second wife in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

For related readingI’ve reviewed dozens of John Sandford’s bestselling crime novels, including all 12 books in the Virgil Flowers series and many of the 40 Prey novels. (There is slight overlap between the two series and now again with the new Letty Davenport novels.) My most recent post was Masked Prey – Prey #30 (John Sandford’s millionaire investigator takes on the alt-right). For my reviews of all the books about Davenport’s most enterprising agent at the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, see John Sandford’s excellent Virgil Flowers novels.

You might also enjoy my posts:

Top 10 mystery and thriller series20 excellent standalone mysteries and thrillersTop 20 suspenseful detective novelsAnd you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post Taking down a sinister Right-Wing militia appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

August 18, 2025

A clever new twist on an old sci-fi trope

Writers have to earn a buck to put food on the table. Once they’re well established as professionals, some grab the opportunity to contract with a deceased author’s estate to continue a best-selling series or use some of its characters in works of their own. And the Australian science fiction author Peter Cawdron followed that course with an authorized short story featuring Kurt Vonnegut and characters he presented in his most famous novel. Later, disguising the connections to Vonnegut, he expanded that story into a short book called Dark Beauty. “Dark Beauty is a tribute to Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five: The Children’s Crusade,” he writes, “a science fiction novel written to deconstruct the Hollywood myth of the war hero.” Cawdron uses the platform to explore the wider dimensions of that myth in a story that piggybacks on the familiar sci-fi trope of humans trapped in an alien zoo.

By the way, just to be clear, I’m certain Cawdron did not enter into this project in hopes of making money. A 100-page novella, much less the short story that spawned it, is unlikely to sell in huge numbers. No doubt, as he intimates in his author’s note at the conclusion of the book, he greatly admires Kurt Vonnegut (as do I) and sincerely wished to honor his memory.

Cleverness aside, the novel has its flawsCawdron’s story works. It’s typically well written, carefully paced, and thoughtful. Unfortunately, his efforts to disguise the Vonnegut connection are clumsy. Vonnegut himself becomes “Kurt Nobody.” The hero of Slaughterhouse-Five, Billy PIlgrim, is Billy Crusader. Billy’s mate in the alien zoo is Dakota Monroe, not Montana Wildhack. I found the obvious distortions to be distracting. Also, to ground the tale on Earth, Cawdron uses not just Billy’s flashbacks to the fire-bombing of Dresden, the central scene in Vonnegut’s novel, but introduces a pair of reporters on a newspaper back home. That doesn’t quite gel for me. Otherwise, as I’ve intimated, the novella is a fun read.

Dark Beauty (First Contact #29) by Peter Cawdron (2025) 105 pages ★★★★☆ As an experiment, I asked Chat GPT to create an image of two 20-something people, a busty blonde woman and a dark-haired man, alone under a geodesic dome in an extra-terrestrial zoo. You see the result. It falls short of an accurate illustration of this story, because in the novella they’re both naked and the extra-terrestrials are all of one species different from those shown above. But you get the point. Image: Chat GPTReflections on philosophy

As an experiment, I asked Chat GPT to create an image of two 20-something people, a busty blonde woman and a dark-haired man, alone under a geodesic dome in an extra-terrestrial zoo. You see the result. It falls short of an accurate illustration of this story, because in the novella they’re both naked and the extra-terrestrials are all of one species different from those shown above. But you get the point. Image: Chat GPTReflections on philosophyWhile Vonnegut’s novel centers on the firebombing of Dresden, Cawdron introduces another, later example of the senselessness of war: the My Lai massacre in Vietnam, when a small detachment of US Army soldiers systematically murdered more than 500 Vietnamese villagers. And he showed that they would have killed another 1,000 or more if a courageous group of soldiers from another unit hadn’t intervened to stop them. The references to this heinous act broaden the anti-war argument that is at the heart of both novels. And together that might have made the point perfectly well.

However, Cawdron doesn’t let the story get the point across. Billy’s ruminations on the mindless cruelty of war, and the aliens’s incomprehension about the insanity of a species so easily driven to violence, afford him the opportunity to explore the broader philosophical implications for humanity at large. Cawdron comes across, as he does so often as a philosopher masquerading as a science fiction author. I’m sure many if not most of his fans enjoy that. But I’d often prefer he just told a story.

A summary of the Vonnegut novel on which Dark Beauty is basedJust for the record, I asked Claude-AI Sonnet 4 to summarize Kurt Vonnegut’s novel in about 300 words. The result follows, interrupted only by the subheads I’ve added to break up the text. As you can see below, there are major elements in the two stories that do not match in any meaningful way. This demonstrates that Peter Cawdron has created an almost entirely original story.

A darkly comic anti-war novel“Slaughterhouse-Five” is Kurt Vonnegut’s darkly comic anti-war novel that follows Billy Pilgrim, an optometrist and World War II veteran who becomes “unstuck in time.” Billy experiences his life non-linearly, jumping between his childhood, war experiences, post-war suburban life, and encounters with aliens called Tralfamadorians.

The novel’s central event is Billy’s experience as a prisoner of war during the Allied bombing of Dresden in 1945, where he witnesses the destruction of the city and its civilian population. Vonnegut, who was himself a POW in Dresden, draws from his own traumatic experiences to create this haunting narrative.

Billy’s time-traveling episodes reveal his entire life simultaneously: his unhappy marriage to Valencia, his successful but unfulfilling career, his survival of a plane crash, and his alleged abduction by Tralfamadorians to their planet Tralfamadore. The aliens teach Billy their philosophy that all moments exist eternally, making free will an illusion and death merely a transition between moments.

A familiar refrain in Vonnegut’s writingThe novel’s famous refrain “So it goes” appears after every mention of death, emphasizing the inevitability and randomness of mortality while highlighting Vonnegut’s fatalistic worldview. This phrase becomes a literary device that both acknowledges tragedy and suggests acceptance of life’s absurdities. [Note: Cawdron uses a similar device in Dark Beauty.]

Through Billy’s fragmented narrative, Vonnegut explores themes of trauma, the meaninglessness of war, the illusion of free will, and the human struggle to find purpose in an indifferent universe. The novel’s science fiction elements serve as metaphors for dealing with psychological damage and the inability to process overwhelming experiences.

“Slaughterhouse-Five” stands as both a powerful condemnation of war’s senseless destruction and a meditation on time, memory, and survival. Vonnegut’s blend of dark humor, philosophical inquiry, and autobiographical elements creates a unique work that captures the absurdity of human existence while offering a compassionate view of those damaged by forces beyond their control.

About the author Peter Cawdron. Image: Amazon

Peter Cawdron. Image: AmazonPeter Cawdron‘s bio on Amazon reads in part as follows: “Peter is a New Zealand/Australian science fiction writer specializing in making hard science fiction easy to understand and thoroughly enjoyable. His First Contact series is topical rather than character-based, meaning each book stands alone. These novels can be read in any order, but they all focus on the same topic of First Contact with extraterrestrial lifeforms. In this regard, the series is akin to Black Mirror or The Twilight Zone.”

For related readingThis is the latest entry in Peter Cawdron’s insightful First Contact book series.

For more good reading, check out:

The five best First Contact novelsThese novels won both Hugo and Nebula AwardsThe ultimate guide to the all-time best science fiction novelsThe top science fiction novels10 new science fiction authors worth reading nowThe 10 best time travel novelsAnd you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post A clever new twist on an old sci-fi trope appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

August 14, 2025

This gorgeous Hollywood star was a brilliant inventor

Version 1.0.0

Version 1.0.0You might not think a biographical novel about a glamorous Hollywood star could figure in the history of World War II. But then you wouldn’t reckon with the Austrian American actress Hedy Lamarr (1914-2000). Born Hedwig Kiesler in Vienna to a nonobservant Jewish father and married six times in the course of her 85 years, Lamarr signed a contract with MGM’s Louis B. Mayer as a refugee on board ship en route to the US. In a long film career, she costarred with the likes of Clark Gable, Jimmy Stewart, and Judy Garland. However, unknown to her millions of fans, Lamarr’s first husband was an arms dealer for Mussolini and Hitler, and she met both men. She was also a brilliant inventor whose concept for a remotely guided torpedo might have saved thousands of lives had the US Navy not refused to adopt it because its inventor was a woman.

First, a marriage to a fascist arms dealerIn The Only Woman in the Room, historical novelist Marie Benedict celebrates Lamarr’s life and achievements. She devotes the first half of her book to Lamarr’s closeted life in Austria as the trophy wife of the country’s richest man. Friedrich (Fritz) Mandl was insanely jealous of his gorgeous young wife—she married him at 19—and was so controlling that he locked her in her room for extended periods. Although he was aware that she was unusually bright, it never occurred to him that she could follow the detailed technical discussions about arms and munitions he had at their dinner table with Austrian, German, and Italian leaders and military experts. She carried this understanding with her when she escaped him after four years of marriage and made her way to the United States.

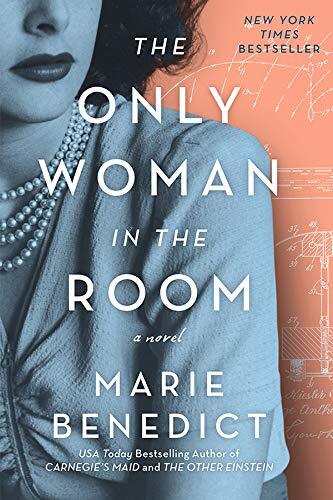

The Only Woman in the Room by Marie Benedict (2019) 320 pages ★★★★★ Publicity still of Hollywood star and inventor Hedy Lamarr, publicized as “the most beautiful woman in the world.” Image: eBayIn Hollywood, quickly emerging as a box-office sensation

Publicity still of Hollywood star and inventor Hedy Lamarr, publicized as “the most beautiful woman in the world.” Image: eBayIn Hollywood, quickly emerging as a box-office sensationHired to join MGM’s stable of pretty starlets, Hedy Lamarr—Mayer’s wife gave her the work name—refused to be content as one among many. Soon, she got her break costarring with Charles Boyer and was on her way to costarring roles with Hollywood royalty. Her on-screen presence was electric, as critics universally noted. Studio publicists promoted her as “the most beautiful woman in the world.” She became one of the studio’s biggest stars. And she slept with many of the men.

A community of fellow refugees sustained herMeanwhile, Lamarr joined the growing community of European refugees in Hollywood—producers, directors, writers, and actors who had fled the Nazis, most because they were Jewish. Among her circle of intimates were Peter Lorre, Otto Preminger, and Joseph Schildkraut. Undoubtedly she knew and often met with others, including Billy Wilder, Marlene Dietrich, Ingrid Bergman, and Fritz Lang. As a group, with connections reaching back to Europe, their knowledge of conditions in Nazi-occupied lands was without doubt more accurate than that of American intelligence. And they lamented the failure of the American press to write about the persecution and, later, the wholesale murder of Jews.

Forced to hide her Jewish heritageHowever, even though Louis Mayer, the Warner Brothers, and many of the other studio heads and owners were Jewish, as were many producers, directors, and writers, they consistently avoided casting Jews in roles on-screen. Lamarr had lied to Mayer about her Jewish heritage, or he would not have hired her on that cross-Atlantic journey.

Austrians cheering Nazi troops as they enter Austria in 1938 in the Anschluss, when Hitler annexed his homeland. This event, one year after Lamarr fled Vienna, haunted her for the rest of her life. Image: Holocaust EncyclopediaObsessed with doing something to help the Allies

Austrians cheering Nazi troops as they enter Austria in 1938 in the Anschluss, when Hitler annexed his homeland. This event, one year after Lamarr fled Vienna, haunted her for the rest of her life. Image: Holocaust EncyclopediaObsessed with doing something to help the AlliesLamarr despaired of the slow progress of the war against the Nazis. All the while she performed her duties for the studio, she agonized over the thought that there must be something she could do to help bring about a speedy Allied victory. After all, she knew a great deal about Axis armaments and their weaknesses as well as their strengths. But nothing gelled until she met an experimental composer named George Antheil. In a flash, she realized that there must be a way to avoid one of the greatest challenges to both of the warring sides: the inaccuracy of their torpedoes. American torpedoes in particular were notoriously unreliable. Lamarr and Antheil figured out how to guide them remotely with perfect accuracy.