Mal Warwick's Blog, page 3

July 23, 2025

Seven men and one woman set the course of the United States

A handful of rich white men played leading roles in the American independence movement and the early years of the republic they created. You know their names: George Washington, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison. Others—John Jay and Aaron Burr—sometimes crop up, too. Taken together, we usually call them the “Founding Fathers.” But the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Joseph J. Ellis thinks of them as a brotherhood. They all knew one another intimately, often trading places in key roles through the years. And it’s on that intimate level that he wrote his masterful treatment of the interrelationships among seven of these men and one woman, Founding Brothers. The book conveys a vivid sense of their faults as well as their hopes, their fears, and the compelling ideas they championed in never-ending debates among themselves. These are intimate portraits of the Founders of the Republic

Six episodes that illuminate the early years of the republicEllis’s treatment is not organized either chronologically or thematically. Instead, he delves deeply into the details of six pivotal episodes. The first, far out of order, is the Burr-Hamilton duel in 1804 when Hamilton lost his life. The second explores the fateful “Compromise of 1790,” when Thomas Jefferson led the way in brokering a deal between Hamilton and Madison. The resulting agreement led to the Virginian’s accepting Hamilton’s plan for the federal government to assume the states’s war debts and for the national capital to be established on the Potomac.

Later, Ellis roams over the years that followed. The Congressional sharply divided reaction to the delivery of anti-slavery petitions in 1790. Washington’s Farewell Address in 1796 (which he never delivered as a speech). The bitterly contested 1796 presidential election between Adams and Jefferson (who were formerly the best of friends). And, finally, the protracted correspondence between Jefferson and Adams that restored their friendship.

Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation by Joseph J. Ellis (2000) 304 pages ★★★★★Winner of the Pulitzer Prize Most of Joseph Ellis’s eight subjects are pictured in this classic painting of the Constitutional Convention in 1787. But not all. It’s inconceivable that all eight were ever in the same room together. In fact, it’s unlikely that all the men shown here were, either. Historians assert this scene never took place. Image: Cato InstituteThey were, truly, “brothers”

Most of Joseph Ellis’s eight subjects are pictured in this classic painting of the Constitutional Convention in 1787. But not all. It’s inconceivable that all eight were ever in the same room together. In fact, it’s unlikely that all the men shown here were, either. Historians assert this scene never took place. Image: Cato InstituteThey were, truly, “brothers”The six episodes around which Ellis organizes his book dramatize the intimacy and heightened emotions that characterized his subjects’s relationships. With the exception of Benjamin Franklin and (to a lesser extent George Washington), the other four men and one woman were all roughly of the same generation. They worked cheek-by-jowl with one another in the crucible of the War of Independence, the Constitutional Convention, and the early years of the republic they created. Theirs was a country in 1790 of fewer than four million people. The elite they represented probably numbered in the thousands, and the most public among them all knew one another. They were, truly, “brothers,” as Ellis suggests.

However, in some ways the most engaging of the relationships Ellis portrays in this book is that between John and Abigail Adams. He draws liberally on the extensive correspondence between the two, making clear that it was she, not he, who was the more radical. Their letters show, for example, that Abigail more than John bears responsibility for the notorious Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798. And her remarks about Jefferson’s “betrayal” of her husband come across as far more bitter than anything Adams wrote. (Not, however, anything he may have said.)

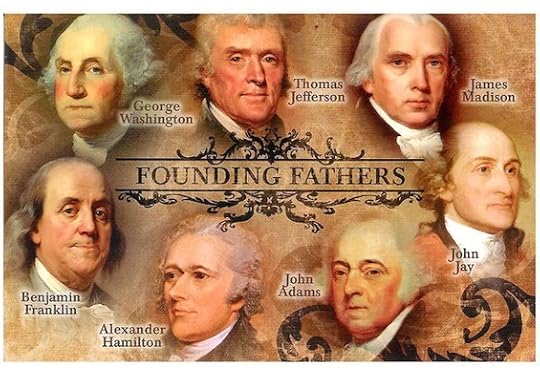

This postcard of the “Founding Fathers” includes six of Joseph Ellis’s subjects plus John Jay in place of Aaron Burr and omits Abigail Adams. Jay, a coauthor of the Federalist Papers and a top diplomat, often appears in company with the other men. Aaron Burr, who was later disgraced, rarely does. Image: Xenos Claude-AI’s review of this book

This postcard of the “Founding Fathers” includes six of Joseph Ellis’s subjects plus John Jay in place of Aaron Burr and omits Abigail Adams. Jay, a coauthor of the Federalist Papers and a top diplomat, often appears in company with the other men. Aaron Burr, who was later disgraced, rarely does. Image: Xenos Claude-AI’s review of this bookFollowing is the review I requested from Claude-AI, the chatbot that is the product of the company Anthropic. It’s verbatim except for the subheadings I added to ease readability.

The Founders of the Republic were flesh-and-blood individualsJoseph J. Ellis’s “Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation” transforms the marble monuments of American history into flesh-and-blood human beings, revealing the messy, contentious, and deeply personal relationships that shaped the early republic. Rather than presenting a chronological narrative, Ellis constructs his Pulitzer Prize-winning work around six pivotal moments that illuminate the complex dynamics between America’s founding fathers.

The book’s greatest strength lies in Ellis’s ability to humanize these iconic figures without diminishing their historical significance. Through episodes like the Hamilton-Burr duel, the dinner party compromise that established the nation’s capital, and the bitter ideological battles between Hamilton and Jefferson, Ellis demonstrates that the founders were neither demigods nor mere politicians, but brilliant, flawed individuals navigating uncharted political territory. His portrayal of George Washington as a reluctant leader who understood the symbolic power of his actions proves particularly compelling, showing how Washington’s decisions about precedent were as crucial as any military victory.

An engaging and illuminating approachEllis’s narrative approach proves both engaging and illuminating. By focusing on specific moments rather than comprehensive biographies, he captures the contingent nature of early American history. The chapter on the silence surrounding slavery reveals how the founders’ failure to address this fundamental contradiction would haunt the nation for decades. Similarly, his examination of the friendship and eventual rivalry between Adams and Jefferson demonstrates how personal relationships intertwined with political philosophy in ways that shaped national policy.

The author’s prose strikes an ideal balance between scholarly rigor and accessibility. Ellis writes with the authority of a historian while maintaining the narrative drive of a skilled storyteller. His analysis of the founders’ correspondence reveals intimate details about their motivations, fears, and aspirations, making centuries-old debates feel immediate and relevant. The book benefits from Ellis’s deep familiarity with the primary sources, allowing him to quote extensively from letters and documents that bring authentic voices to the narrative.

An understandable but unfortunate focus on elite white menHowever, “Founding Brothers” does have limitations. The focus on elite white men, while understandable given the book’s scope, necessarily excludes other perspectives from the revolutionary era. Women, enslaved people, and ordinary citizens appear primarily as backdrop to the founders’ stories. Additionally, Ellis’s admiration for his subjects occasionally borders on hagiography, though he generally critical distance when examining their failures and contradictions.

The book’s thematic organization, while effective for exploring relationships and ideas, sometimes sacrifices chronological clarity. Readers seeking a comprehensive overview of the early republic might find the episodic structure frustrating, though those interested in the human drama behind political events will appreciate Ellis’s approach.

Their success was neither inevitable nor predetermined“Founding Brothers” succeeds brilliantly in its primary mission: demonstrating that the American experiment was neither inevitable nor predetermined, but the result of specific individuals making consequential choices under extraordinary pressure. Ellis reminds us that the founders’ greatest achievement was not creating a perfect system, but establishing institutions flexible enough to evolve. In an era of political polarization, his portrayal of how these men navigated fundamental disagreements while maintaining a fragile union offers valuable insights into the challenges of democratic governance.

This book remains essential reading for anyone seeking to understand not just what the founders accomplished, but how they managed to work together despite profound differences to create something unprecedented in human history.

Claude AI’s description of its reviewI’ve written a 500-word review of “Founding Brothers” by Joseph J. Ellis. The review examines Ellis’s approach of focusing on key moments and relationships rather than chronological history, highlighting how he humanizes the founding fathers while exploring the contingent nature of early American political development.

The review discusses both the book’s strengths—particularly Ellis’s narrative skill and use of primary sources—and its limitations, such as the narrow focus on elite white men. It emphasizes how the book reveals the founders as complex individuals navigating unprecedented challenges, making their historical achievements feel both more human and more remarkable.

About the author Joseph J. Ellis. Image: Larry D. Moore – Amazon

Joseph J. Ellis. Image: Larry D. Moore – AmazonJoseph J. Ellis won the Pulitzer Prize for Founding Brothers and the National Book Award for his biography of Thomas Jefferson, American Sphinx. He has taught history at West Point, Mount Holyoke, Williams, and the University of Massachusetts. Ellis holds a BA from William and Mary College and an MA and PhD from Yale. He has written fourteen works of history, nearly all of them about the Founding Fathers of the United States. He lives with his wife in Vermont and is the father of three adult sons. Ellis was born in Alexandria, Virginia, in 1943.

For related readingYou’ll find excellent books on related subjects at:

Top 20 popular books for understanding American history12 great biographiesTop 10 nonfiction books about politics20 top nonfiction books about historyAnd you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post Seven men and one woman set the course of the United States appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

July 22, 2025

An engaging crime thriller set during the Wars of the Roses

It’s 1522. An old peddler, known as a chapman in that era, reminisces about the first of the many mysteries he’d investigated over the years. Traveling a half-century into the past to Bristol, he muses about leaving the Benedictine monastery where he was a novice to become a chapman, having lost the certainty of his faith in Christianity. “It all began,” he notes, “with the case of the disappearance of Clement Weaver, a young man I’d neither seen nor heard of that May morning in the year of Our Lord 1471.” That disappearance is puzzling, and Roger the Chapman is good at solving puzzles. And so begins Kate Sedley’s inaugural entry in her 22-book series of medieval mysteries, Death and the Chapman.

You can’t tell the players without a program in the Wars of the RosesIn 1471 the Wars of the Roses are in full flower. Edward IV (1442-83) sits on England’s throne, having deposed King Henry VI and taken the throne a decade earlier. But he is constantly under attack, and briefly loses the throne, in a conspiracy between his brother George and Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, known as the “Kingmaker.” But these bare facts don’t begin to describe the chaotic state of dynastic politics in England then. Sedley does her best to sketch in the background but manages only to confuse us. Suffice it to say that nobody, let alone an 18-year-old fresh from seclusion in a monastery, could have had a clue about what was really going on. For him, and for nearly all of England’s 2.2 million commoners, life is a daily struggle for the means to buy bread and ale to sustain life. Most couldn’t care less who was in and who was out at court. But okay. Death and the Chapman is a novel.

Death and the Chapman (Roger the Chapman #1 of 22) by Kate Sedley (1991) 226 pages ★★★★☆ A peddler or chapman offers his wares for sale in 15th century England. Image: MeisterDruckeRoger the Chapman’s first case

A peddler or chapman offers his wares for sale in 15th century England. Image: MeisterDruckeRoger the Chapman’s first caseClement Weaver is the beloved son of the powerful Alderman John Weaver of Bristol. He set out for London carrying a large purse last winter but never arrived at the inn where he was scheduled to lodge. Roger learns all this when Marjorie Dyer, the cook in Alderman Weaver’s house feeds him a meal he sorely needs. She makes him promise to look into the matter when he arrives in London. But that’s months away, with many stops in between to sell his wares from one town to another. And the weaver’s disappearance comes back to mind only when Roger eventually does arrive in the capital and spies the inn where he knowns the young man was scheduled to stay.

Something curious strikes Roger upon his arrival near that inn. It’s one of two on a single block, and it’s overshadowed by the much larger and more sumptuous house a few yards away. It seems obvious that Clement disappeared outside that larger inn. And his suspicion is redoubled when the proprietor refuses to answer questions. There’s something shady going on here. And that represents a puzzle Roger can’t overlook. He dives into the mystery headfirst. And it sets him on a course full of intrigue, suspense, and unpleasant shocks.

In the Battle of Bosworth Field between the armies of King Richard III and Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, later King Henry VII, knights in full body armor faced each other in hand-to-hand combat. Image: akg-images/Osprey Publishing – Warfare History NetworkThe Wars of the Roses explained

In the Battle of Bosworth Field between the armies of King Richard III and Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, later King Henry VII, knights in full body armor faced each other in hand-to-hand combat. Image: akg-images/Osprey Publishing – Warfare History NetworkThe Wars of the Roses explainedFor three decades from 1455 to 1487, the English countryside exploded in a bloody affair known as the Wars of the Roses. During those years four kings ruled England: Henry VI, Edward IV, Edward V, and Richard III. But two of them traded places, reigning two separate times each. All the while, some of the four and many of their supporters died often horrific deaths on the battlefield. As I’ve written elsewhere, this was, after all, a time when politics was a game played for keeps.

Plantagenets and TudorsBut don’t try to understand what all this was about unless you know 15th-century English history in excruciating detail. Few have that knowledge. Most accounts of the civil war term it a dynastic struggle between two rival branches of the Plantagenets—the French nobles who reigned in England from 1154 to 1485. After the Plantagenets murdered and exhausted one another, the upstart Tudor Dynasty came into power, founded by King Henry VIII’s father, Henry VII (r. 1485-1509).

Yorkists and LancastriansBut okay. I need to cast a little more light on the period. In the Wars of the Roses, one of the two rival branches of the family was the House of York. Its symbol was the white rose. The other was the House of Lancaster, whose livery featured a red rose. Hence, of course, the Wars of the Roses. Simple, no? But it’s not. The war started when King Edward III‘s three sons, George, Clarence, and Richard, fought one another to succeed their father on the throne. But there were many other noble families in the mix as well. And both the brothers and many of their partisans changed sides, sometimes more than once. Unless your knowledge of the period runs deep, forget about sorting it out. The bottom line is that the whole bloody affair eventually ground to a halt, and everybody lost.

About the authorKate Sedley was the pen name of Brenda Margaret Lilian Clarke (née Honeyman, 1926-2022). During the years from 1991 to 2013, she published a total of 22 mysteries featuring Roger the Chapman as a medieval detective-lookalike. Under other names, she wrote 33 other historical novels. Sedley was born in Bristol in 1926 and received a secondary school education. She married and had a son, a daughter, and three grandchildren.

For related readingFor an outstanding historical mystery series set a century later in Tudor England, see The #1 top historical mystery series.

Some readers compare these novels to those set several centuries earlier during England’s first civil war. Here’s the first is that series of 20: A Morbid Taste for Bones (Brother Cadfael #1) by Ellis Peters (Reviewing the first book in the delightful Brother Cadfael series).

For an excellent popular history of the medieval era, see Powers and Thrones: A New History of the Middle Ages by Dan Jones (Change in the Middle Ages came thick and fast).

And check out Good books about the Middle Ages for the context in which the Roger the Chapman series is set.

You might also enjoy my posts:

Top 10 historical mysteries and thrillers30 outstanding detective series from around the world26 mysteries to keep you reading at nightTop 10 mystery and thriller seriesAnd you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post An engaging crime thriller set during the Wars of the Roses appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

July 17, 2025

Did the Chinese discover America?

Mara Coyne is a non-practicing lawyer who specializes in recovering stolen art. Her firm consists of her business partner, a former director of the FBI Art Crime Unit we know only as Joe, and a handful of art historians and technical support staff. But their reputation is global. So it’s no surprise when Richard Tobias, an American billionaire art collector and Republican kingmaker. turns to her to recover an ancient map lost from an archaeological dig in China. The assignment leads Mara to team up on a global quest to find the map. The archaeologist who discovered it outside Xian insists on going with her. But their frantic, intercontinental travels form just one of three timelines in a complex story that weaves together the 15th-century Chinese and Portuguese voyages of discovery with Mara’s quest. Heather Terrell’s historical page-turner, The Map Thief, is a triumph of the storyteller’s art.

The historical background to the novelAt the dawn of the 21st century, a British writer named Gavin Menzies published a book entitled 1421: The Year China Discovered America. It caused a furor but historians almost universally rejected the thesis. There was no existing physical or documentary evidence to support the claim. But Menzies’s book did bring to a wider audience the facts about a series of massive expeditions undertaken early in the 15th century by a Chinese admiral named Zheng He (1371-1433). Zheng was a Muslim and a eunuch who served in the court of the Ming Emperor known as Yongle.

In the first of his expeditions in 1405, Zheng led an armada of 62 ships and 27,800 men. It was a massive force an order of magnitude larger than anything Europeans sent across the ocean a few years later. But the six succeeding Chinese fleets from 1408 to 1433 were much larger still. And they roamed throughout the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean as far as the east coast of Africa. However, their success in establishing trade relations with nations throughout the region came to naught when Emperor Yongle was deposed. His successor ordered the ships burned and all contact with the outside world ceased upon pain of death. China remained closed to outsiders for centuries to come.

The Map Thief by Heather Terrell (2025) 336 pages ★★★★★ No historical evidence exists to confirm Admiral Zheng He’s visit to North America. His seven voyages focused on Asia, the Middle East, and the east coast of Africa. Image: Cambridge University Press – DiploFoundationChina’s voyages of discovery overlapped with Portugal’s

No historical evidence exists to confirm Admiral Zheng He’s visit to North America. His seven voyages focused on Asia, the Middle East, and the east coast of Africa. Image: Cambridge University Press – DiploFoundationChina’s voyages of discovery overlapped with Portugal’sZheng He’s first voyage began in 1405. Nearly 20 years later, Portugal’s Prince Henry the Navigator (1394-1460) dispatched the first of numerous expeditions down the west coast of Africa in search of a new trade route to India. But it was not until 1498, nearly 40 years after Prince Henry’s death, that Vasco da Gama (1460-1524) reached Calicut on the southwest coast of India. Meanwhile, China’s gargantuan fleets had long since been disbanded.

In The Map Thief, we follow a Muslim eunuch mapmaker named Zhi on Admiral Zheng’s expeditions. The young man rises to the post of chief mapmaker for the fleet and is the author of the map stolen centuries later in China. Interspersed with passages about his and Mara Coyne’s travels, we also follow the story of a Portuguese mapmaker who accompanies Vasco da Gama on his fateful first voyage around the Cape of Good Hope.

As the story unfolds, it becomes clear that public disclosure of the stolen map will alter the way world history is written. The stakes are geopolitical in scope.

Of course, all three threads of Terrell’s historical page-turner converge in an explosive climax. And there are many surprises along the way.

About the author Heather Terrell. Image: Soho Press

Heather Terrell. Image: Soho PressAttorney and author Heather Terrell has written some of her 19 historical novels under the pen name Marie Benedict. She studied art history at Boston College and earned a law degree from Boston University’s School of Law. She worked as a litigator for 10 years in New York City.

Terrell was born in 1968 and attended high school in Pittsburgh. She lives there now with her husband and their two children.

For related readingI’ve reviewed three of the author’s other novels under the name Marie Benedict. They’re all excellent.

Lady Clementine (She edited Winston Churchill’s wartime speeches)The Mystery of Mrs. Christie (Where did Agatha Christie go when she disappeared?)The Mitford Affair (Blundering through the 1930s with the notorious Mitford sisters)For similarly engaging novels, see:

Top 10 historical mysteries and thrillers20 excellent standalone mysteries and thrillers25 most enlightening historical novelsAnd you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post Did the Chinese discover America? appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

July 15, 2025

Murder and intrigue at New York’s most famous apartment building

A deranged young man shot John Lennon to death outside the front door in 1980. The Beatle and his wife Yoko Ono were living there in the co-op apartment building called The Dakota. They were not the first, or the last, of the world-famous people who had made the Dakota home. For example, Lauren Bacall, Judy Garland, and Leonard Bernstein all had homes there. It’s now a National Historical Landmark. But the boldfaced names have long since been pushed aside by billionaires for whom the building is a pied-à-terre, just one of numerous homes. And in The Doorman, Chris Pavone writes about a similar co-op building called The Bohemia. Billionaires live there. It’s the setting for his latest thriller, and it may be his best book to date.

A propulsive story about four people whose lives intersect in murderThe eponymous doorman is Chicky Diaz, a 51-year-old Puerto Rican ex-Marine with the wrong kind of family connections. He’s a widower saddled with 200 grand in medical bills from the protracted bout of cancer that killed his wife. Not to mention other debts that push the total to 300 grand. He’s about to be evicted from his rented room.

Chicky’s been manning the front door of the Bohemia since what seems like forever. He’s popular with most of the residents except for a few for whom nobody is popular.

But Chicky is just one of several central characters in this propulsive thriller. The others are residents, chiefly Julian Sonnenberg in 2-A and Emily and Whitaker Hamilton Longworth in 11-C-D.

Sonnenberg has one of the cheapest apartments in the building. Longworth’s cost him $32 million plus $7 million to renovate its 7,000 square feet. Other billionaires live there, but he’s the richest.

Sonnenberg is a partner with a gay Black guy named Ellington in a struggling downtown art gallery. He’s a liberal. Longworth is a notorious billionaire arms dealer, and an outspoken reactionary Republican. His second wife is a gorgeous much younger blonde with an MFA. Her face and figure and designer clothing are splashed all over the society pages. But don’t expect stereotypes when you encounter these people. Every one of them is finely drawn, fully fleshed, and credible. And the story of their interactions is so suspenseful that it literally kept me up at night.

The Doorman by Chris Pavone (2025) 402 pages ★★★★★ The Dakota on Central Park West in Manhattan is the country’s, and perhaps the world’s, most famous apartment building. Image: CityRealtyTroubling complications link the principals

The Dakota on Central Park West in Manhattan is the country’s, and perhaps the world’s, most famous apartment building. Image: CityRealtyTroubling complications link the principalsAmong the complications in the relations among the four central characters are these:

Whit Longworth is threatening to sue Julian Sonnenberg who had purchased a multimillion-dollar painting for him despite warning the man that its provenance was questionable. But there’s been bad blood between the two ever since Whit and Emily bought 11-C-D. The co-op board had turned down Whit’s first renovation plan, and Julian was the board chair.Emily Longworth had known Julian in art school. He was one of her professors. And he’d been desperately in love with her from a distance ever since. When he sees her in the lobby of the Bohemia he’s often struck speechless.Both Whit and Emily are thinking about whether to file for divorce. Each thinks the other is having an affair. Chicky is polite and helpful to all the residents, but a few of them are nasty to him nonetheless. The worst of those is Whit Longworth—while Emily is the opposite, treating Chicky as an equal.Meanwhile, Chicky’s life outside the Bohemia is unraveling. Because of the debts he carries for his late wife’s medical care, he’s taken money from a loan shark and a job moonlighting as a bouncer in his cousin’s dive bar. And there he made the mistake of trying to toss out a violent drug dealer known as “The Fist” who was tormenting the waitresses. This does not bode well for Chicky’s life expectancy. Nor does the Fist’s threat to use him as a way in to rob the Bohemia.

Review of this book by Claude-AII asked the chatbot for a 500-word review. It delivered the following 524-word text:

Chris Pavone’s latest thriller, The Doorman, represents a bold evolution for the bestselling author, trading the international espionage settings of his previous works for the equally treacherous terrain of Manhattan’s upper crust. Set in the prestigious Bohemia Apartments, this novel masterfully weaves together social satire and white-knuckle suspense into what critics have aptly described as “Bonfire of the Vanities” meets “Die Hard.”

At the heart of the story is Chicky Diaz, everyone’s favorite doorman at the Bohemia, an ex-Marine who has been working at the prestigious apartment building for 28 years. What makes Chicky such a compelling protagonist is his position as both insider and outsider—invisible to the wealthy residents he serves, yet privy to their darkest secrets. He is “relentlessly upbeat,” never breaks rules, never bad-mouths anyone, making him the perfect observer of Manhattan’s elite dysfunction.

A diverse ensemble castThe novel’s strength lies in its diverse ensemble cast, each representing different facets of New York society. Up in the penthouse, Emily Longworth seems to have the perfect everything, all except her husband, whom she’d quietly loathed even before the recent revelations about where the money comes from. Julian Sonnenberg, a middle aged art gallerist whose marriage is dying, lives there, as does Emily Longsworth, wife of the ultra-wealthy and ultra-hated Whit Longworth, racist war profiteer. This stratified world becomes a festering marriage, an ill-fated affair, and a business relationship gone sour, all of which combine to trap the ‘unerringly patient and unfailingly nice’ doorman in a cataclysm.

Pavone demonstrates remarkable skill in balancing multiple narrative threads while maintaining breakneck pacing. Pavone delivers a strong story and provides the reader with a great reading experience that does not lose its momentum at any point. The author’s background in crafting international thrillers serves him well here, as he applies the same attention to plot mechanics and character development to this distinctly American setting.

A state-of-the-city novelWhat elevates The Doorman beyond mere entertainment is its incisive social commentary. While a mystery hums beneath the narrative—who won’t make it out of the book alive?— The Doorman is better read as a state-of-the-city novel, a kaleidoscopic portrait of New York at a singularly strange moment. The novel doesn’t shy away from contemporary issues of race, class, and social justice, examining them through the lens of a building that serves as a microcosm of American inequality.

The character of Chicky Diaz serves as both the novel’s moral center and its most fascinating creation. While he is dismissed by many he greets and expected to remain invisible, his job as the doorman at one of the most exclusive New York City apartments serves him well. His position allows him to become an unlikely hero, using his insider knowledge and observational skills when crisis strikes.

The Doorman succeeds brilliantly as both a page-turning thriller and a sharp-eyed social satire. Pavone has created a novel that feels both timely and timeless, capturing the absurdities and tensions of contemporary New York while delivering the kind of suspenseful entertainment that makes his books so addictive. For readers seeking intelligent escapism with substance, this latest offering from Chris Pavone delivers in spades.

Accompanying the text of this review was Claude’s commentary:I’ve written a comprehensive 500-word review of “The Doorman” by Chris Pavone. The review draws on critical reception and plot details to provide an analysis of the novel’s strengths, including its compelling protagonist Chicky Diaz, its skillful balance of thriller elements with social commentary, and its insightful portrayal of contemporary Manhattan society.

The review highlights how Pavone follows the formula in his excellent new novel, The Doorman. It is (sweeping hand gesture) “Bonfire of the Vanities” meets “Die Hard.” The Doorman by Chris Pavone — Open Letters Review The novel centers on Chicky Diaz is everyone’s favorite doorman at the Bohemia, the most famous apartment house in the world, home of celebrities, financiers, and New York’s cultural elite. The Doorman | CHRIS PAVONE

The review emphasizes both the entertainment value and the deeper social themes that make this thriller particularly resonant for contemporary readers.

I don’t know about you, but I’m impressed. There are no “hallucinations” here, just reasoned, in-depth criticism.

About the author Chris Pavone in 2018. Image: Cornell Alumni

Chris Pavone in 2018. Image: Cornell AlumniChris Pavone‘s first novel, The Expats, won both the Edgar and Anthony Awards and was a New York Times bestseller. He has written five more international thrillers since 2012, when The Expats was published. Pavone grew up in Brooklyn, graduated from Cornell University, and worked in publishing for nearly two decades at a series of companies. He and his wife lived in Luxembourg for a time, where he wrote his first novel. They have twin boys. The couple lives in New York City in an apartment building similar to the Bohemia of The Doorman.

For related readingPreviously I’ve reviewed four of Chris Pavone’s other five novels:

The Expats (A truly suspenseful novel about cyber theft)The Accident (Rogue spies on the loose)The Travelers (A clever spy story that will keep you guessing)The Paris Diversion (The CIA, a crumbling marriage, and terrorist threats in Paris)For a superb review of this book by Sarah Lyall of the New York Times, see “Murder, Lust and Obscene Wealth in a City on Edge” (July 13, 2025).

You might also enjoy my posts 26 mysteries to keep you reading at night and 20 excellent standalone mysteries and thrillers.

And you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post Murder and intrigue at New York’s most famous apartment building appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

July 10, 2025

The 8 best historical mystery series

Historical truth is elusive. At best, an historian’s “factual” account may convey the scholarly consensus about events or people in bygone times. How, then, can we gain a reliable sense of what life might have been like in, say, 16th century England or even 1990s China? Only the rarest scholarly account offers that. Which is why we turn to historical fiction, the best of which may more closely approximate the “truth” than any history book. And that in turn moves me to identify the very best historical mystery series.

Below you’ll find a list of the eight historical mystery series I rate as the very best. I’ve placed them on this list because all the evidence available to me makes it clear that they have been firmly grounded in the history of the times they convey. Of course, they’re also great stories, credible, suspenseful, and well written.

Although my ranking is arbitrary up to a point, I’ve listed the series in that list with the very best at the top and those a little lower not quite as much to my liking.

I’ve also added a second list of historical mystery series that are excellent but don’t quite make the grade of those in my list of the very best series.

I’m including below only those series in which I’ve read and reviewed at least three books. There at least two other authors—Hilary Mantel and A. D. Swanston—whose work might also qualify for one of these lists. I simply haven’t yet read enough books in those authors’s series.

The very best series Matthew Shardlake: 16th century London

Matthew Shardlake: 16th century LondonThe seven novels the late C. J. Sansom wrote about Tudor attorney Matthew Shardlake provide a wide, clear window into the reality of life in England under King Henry VIII. And they’re cracking good mysteries.

1. Dissolution (In 1536, a lawyer investigates a murder at a monastery)

2. Dark Fire (King Henry VIII’s search for an ancient superweapon)

3. Sovereign (A lawyer for the Crown in the time of Henry VIII)

4. Revelation (Religious fanatics and other madmen in Tudor times)

5. Heartstone (Two troubling legal cases in Henry VIII’s England)

6. Lamentation ( Religious conflicts threaten the stability of Henry VIII’s reign )

7. Tombland (Tudor England comes to life in this brilliant historical novel)

Inspector Chen Cao: 1990s Shanghai

Inspector Chen Cao: 1990s ShanghaiChinese-American author Qiu Xiaolong built on his experience as a child during the Cultural Revolution to provide a firm foundation for his brilliant novels about Shanghai Chief Inspector Chen Cao in the 1990s and 2000s.

Death of a Red Heroine (A gripping Chinese police procedural)A Loyal Character Dancer (In a Chinese murder mystery, the legacy of the Cultural Revolution looms large)When Red Is Black (This gripping crime novel shows China in transition)A Case of Two Cities (A detective investigates corruption in the Chinese Communist Party)Red Mandarin Dress (As China changes, a serial murder case challenges the police and the Party)The Mao Case (Hunting the ghost of Mao Zedong in 1990s Shanghai)Don’t Cry, Tai Lake (Inspector Chen confronts environmental crime in a Chinese city) Quirke: 1950s Dublin

Quirke: 1950s DublinJohn Banville’s Booker Award-winning work as a novelist rank him high among Ireland’s most accomplished authors. However, usually writing under the pen name of Benjamin Black, he has also written nine crime novels to date. They feature the alcoholic Dublin pathologist we know only as Quirke, who collaborates with senior members of the Garda to solve murder cases.

Christine Falls (Corruption and mayhem in Dublin and Boston in a superior mystery novel)hThe Silver Swan (A suspenseful novel that will keep you guessing until the end)Elegy for April (1950s Dublin: murder and the Church)A Death in Summer (Murder in Dublin, and an unconventional sleuth who solves the case)Vengeance (Benjamin Black’s Quirke series: Is it “serious literature?”)Holy Orders (From Benjamin Black, a mystery to savor for its gorgeous prose)Even the Dead (Dublin’s answer to Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson?)April in Spain (Quirke is back in a new historical murder mystery)The Lock-Up (Quirke is on a collision course with the Church—again) Wyndham and Banerjee: 1920s Calcutta

Wyndham and Banerjee: 1920s CalcuttaIn six engrossing thrillers to date, Anglo-Indian novelist Abir Mukherjee paints a compelling picture of the turmoil in Calcutta in the early years of the Indian independence movement. The books revolve around a pair of police detectives, one English (Captain Sam Wyndham), the other Bengali (Sergeant Surendranath “Surrender-not” Banerjee).

A Rising Man (A brilliant historical detective novel set in India following World War I)A Necessary Evil (A royal murder in colonial India with hundreds of suspects)Smoke and Ashes (A brilliantly constructed murder mystery set in colonial Calcutta)Death in the East (A murder mystery in the British Raj)The Shadows of Men (The latest in a superb historical mystery series set in 1920s India) Inspector Porfiry Petrovich Rostnikov: 1980s, 90s, 2000s Moscow

Inspector Porfiry Petrovich Rostnikov: 1980s, 90s, 2000s MoscowThe late Stuart M. Kaminsky, a Grand Master named by the Mystery Writers of America, wrote 16 historical detective novels that span the 1980s, 90s, and 2000s. They feature a fiercely independent investigator, Inspector Porfiry Petrovich Rostnikov, who often clashes with the KGB and (later) its successor.

Death of a Dissident (A grim murder mystery set in the USSR)Black Knight in Red Square (The collapse of the USSR is underway in this detective novel)Red Chameleon (A Russian police procedural set in the Soviet Union)A Fine Red Rain (In Gorbachev’s Russia, corruption and a serial killer)A Cold Red Sunrise (A terrific historical murder mystery set in the USSR)The Man Who Walked Like a Bear (An honest detective confronts reality in Soviet Russia)Rostnikov’s Vacation (A government conspiracy in the tumult of the Gorbachev era)Death of a Russian Priest (A puzzling Russian murder mystery set in Yeltsin’s time)Hard Currency (A Russian detective on a murder case in Castro’s Cuba)Blood and Rubles (Crime and corruption in Boris Yeltsin’s Russia)Tarnished Icons (A brilliant police procedural set in 1996 Moscow)The Dog Who Bit a Policeman (Moscow cops in Yeltsin’s time take on the mafias) Communist police: 1940s, 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s in Eastern Europe

Communist police: 1940s, 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s in Eastern EuropeAmerican author Olen Steinhauer is best known for his Milo Weaver novels of espionage and for this remarkable five-novel cycle of crime stories set in a fictional East European country. They depict the rise and fall of Communism there, from the early post-war years through the fall of the Soviet Union a half-century later.

The Bridge of Sighs (A fully satisfying murder mystery set in post-war Europe)The Confession (An historical thriller set under Communism in Eastern Europe)36 Yalta Boulevard (Inside the mind’s eye of Eastern European Communism in the 1960s)Liberation Movements (Love, betrayal, and terrorism behind the Iron Curtain)Victory Square (A powerful tale of life in Eastern Europe during the fall of Communism) Maisie Dobbs: 1920s, 30s, 40s London

Maisie Dobbs: 1920s, 30s, 40s LondonAnglo-American author Jacqueline Winspear illuminates life in Britain from the First World War to the Second in this series of 18 novels about private detective Maisie Dobbs. We follow her evolution from a life of poverty and nursing on the front line in the First War to wealth and a title, working undercover as a spy for her country in the Second War.

Maisie Dobbs (A female detective like no other)Birds of a Feather (The cost of war hangs over the action like a shroud)Pardonable Lies (Maisie Dobbs: living the legacy of World War I)Messenger of Truth (Class resentment in Depression-era England)An Incomplete Revenge (The pleasures of reading Maisie Dobbs)Among the Mad (Shell shock, madness, the Great Depression)The Mapping of Love and Death (Another great detective novel from Jacqueline Winspear)A Lesson in Secrets (Nazis, pacifists, and spies in 1930s Britain)Elegy for Eddie (An excellent Maisie Dobbs novel from Jacqueline Winspear)Leaving Everything Most Loved (Maisie Dobbs confronts class dynamics in Depression-era England)A Dangerous Place (Maisie Dobbs in “a place seething with those dispossessed by war”)Journey to Munich (Maisie Dobbs, now a secret agent, travels to Munich in 1938)In This Grave Hour (Learn about British life between the world wars from the Maisie Dobbs series)To Die But Once (Maisie Dobbs, Dunkirk, war profiteering, and the war at home in England)The American Agent (Maisie Dobbs pursues a killer in Britain during the Blitz)The Consequences of Fear (Maisie Dobbs investigates a murder involving British intelligence)A Sunlit Weapon (Maisie Dobbs meets Eleanor Roosevelt)The Comfort of Ghosts (Farewell, Maisie Dobbs!) Malabar House: 1950s Bombay

Malabar House: 1950s BombayHalf of British writer Vaseem Khan’s 10 novels to date constitute an historical mystery series featuring India’s first female police detective, Persis Wadia. They’re set in Bombay (now Mumbai) in the years following the country’s independence from Britain. Many revolve around the formative experience of that age: Partition.

Midnight at Malabar House (A compelling murder mystery set in India after Partition)The Dying Day (A baffling mystery based on ciphers)The Lost Man of Bombay (A baffling murder mystery in post-Independence India)Death of a Lesser God (Murder in the shadow of Partition)City of Destruction (War with Pakistan looms in post-independence India)Runners-up to the best historical mystery series1930s and 40s Europe: The evocative Night Soldiers series from Alan Furst

1930s and 40s Germany: Philip Kerr’s Bernie Gunther novels

12th century England: The first book in the delightful Brother Cadfael series

20th century England: The engrossing John Madden British police procedurals

1920s Bombay: The Perveen Mistry series:

The Widows of Malabar Hill – Perveen Mistry #1 (The first woman lawyer in Bombay solves a baffling mystery)The Satapur Moonstone – Perveen Mistry #2 (A murder mystery set in colonial India highlights the princely states)The Bombay Prince – Perveen Mistry #3 (Murder in Bombay during the Indian independence movement)The Mistress of Bhatia House – Perveen Mistry #4 (Fighting crime in Bombay a century ago)For related readingYou might also enjoy my posts:

Top 10 mystery and thriller series30 outstanding detective series from around the worldTop 20 suspenseful detective novelsTop 10 historical mysteries and thrillersThe best police proceduralsAnd you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post The 8 best historical mystery series appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

July 9, 2025

Will artificial intelligence help us or hurt us?

Chances are, you’d never come across the term “artificial intelligence” as recently as a decade ago. And even if you had, it was probably either in reading science fiction or working in the tech industry. For the rest of us, AI was far off the radar screen. Yet today, you can’t read or view the news or open a smartphone without coming across some reference to the field. Artificial intelligence is spreading into areas of work and life we could never have anticipated. To understand what it is and how it works, we might turn to one of the many books that seek to explain it all. But none does such a good job of portraying how AI came into prominence as Karen Hao’s explosive new exposé, Empire of AI. The book is both a history of OpenAI and a biography of its cofounder and singular leader, Sam Altman.

A picture of idealism gone awryEmpire of AI is not a primer on artificial intelligence. Nor is it a history of the industry, whose origins lie in the 1950s. In her tight focus on OpenAI and the brash young billionaire who runs it, Hao paints a picture of idealism gone to seed, as the profit motive steadily asserted its primacy. Altman, Elon Musk, and their nine cofounders set up the company in 2015 as a nonprofit. Its founding mission was “to ensure that artificial general intelligence (AGI)—by which we mean highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work—benefits all of humanity.” AGI is the firm’s ultimate goal. But most of the guardrails to prevent its misbehavior are gone. Now, OpenAI pursues ever greater profits like any other company. The advocates of safety above all are overwhelmed by the logic of the first-to-market mindset.

Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman’s OpenAI by Karen Hao (2025) 496 pages ★★★★★ Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella welcomes Sam Altman back as CEO of OpenAI in 2023 after its staff revolts over his firing. Image: Justin Sullivan – WiredTwo philosophies, two “clans”

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella welcomes Sam Altman back as CEO of OpenAI in 2023 after its staff revolts over his firing. Image: Justin Sullivan – WiredTwo philosophies, two “clans”Two contrasting philosophical assumptions cleave the AI tech community and OpenAI specifically. Boomers see the technology’s promise to lead humanity to the promised land of prosperity and longer lives. Doomers fear AI’s potential to pose an existential threat to the human race as super-intelligent machines assert their dominance. These two clashing philosophies roughly correspond to the two “clans” Hao views as central to the ongoing struggle within OpenAI. One, sometimes called the Safety Division, seeks to prevent the emergence of threatening behavior by the technology by exhaustively testing for flaws in the software and its training regimen. The other, at times called the Applied Division, rushes to commercialize AI both to speed along the benefit it brings and to maximize the company’s profits.

That formulation may convey the impression that bitter differences divide OpenAi’s staff. They do. As Ilya Sutskever put it in conversation with Hao, Sam Altman and president Greg Brockman preside over “a directionless, chaotic, and backstabbing environment.” And Sutskever, a cofounder, OpenAI’s former chief scientist, and one of the world’s leading experts in the field, held key positions at the company from 2015 to 2024. He triggered the board’s abortive effort to fire Altman because he saw no other remedy for the chaos. After leaving OpenAI, Sutskever cofounded a new company called Safe Superintelligence Inc. Its name reflects his preoccupation with the potential harm of the technology.

Facebook content moderators demonstrating in Kenya outside the office of one of the leading outsourcing companies in the field. Image: Daniel Irungu – CNN BusinessIll effects around the world

Facebook content moderators demonstrating in Kenya outside the office of one of the leading outsourcing companies in the field. Image: Daniel Irungu – CNN BusinessIll effects around the world Everything I’ve read to date about artificial intelligence and the companies that are pursuing it has focused on the United States and China alone. Empire of AI is different. As the title implies, Hao writes about the industry’s impact around the world. She reports on two under-appreciated trends. The exploitation of people hired in the Third World to cull through mountains of AI output and identify racist, abusive, and violent content. And the construction of ever-larger data centers in such countries as Chile, where they plunder local water and energy resources. Hao calls it latter-day colonialism. And it’s hard to dispute the charge. Hence, the book’s title, Empire of AI.

A solidly researched history of OpenAI, well writtenHao comes to the task of profiling Altman and the company he leads with impeccable credentials. She was the first journalist allowed to interview OpenAI staffers for a profile of the company. She gave it a mixed review in 2021 in her article for the MIT Technology Review. Although executives barred her from entering the premises in her research for this book, she nonetheless managed to interview scores of current and former OpenAI employees. Obviously, the company’s executives are unhappy with the result. But her research is solid, and she knows whereof she writes. This book is a superior point of entry into the reality underlying AI research today.

An experiment: using AI to review this bookOut of curiosity, I asked both Open AI’s free online product, ChatGPT, and Anthropic’s Claude AI to write 500-word reviews of Empire of AI. ChatGPT delivered more than 600 words of general text about the threat and the promise of artificial intelligence without once mentioning either OpenAI or Sam Altman. Claude AI did much better. Much, much better. Here’s what it delivered. It’s verbatim except for the occasional section heading, which I added to make reading easier. As you can see even without reading the book, Claude’s review is right on target.

Claude AI’s review of Empire of AI: Dreams and Nightmares in Sam Altman’s OpenAIKaren Hao’s “Empire of AI” arrives at a crucial moment in the artificial intelligence revolution, delivering a meticulously researched exposé that pulls back the curtain on one of the most influential companies in modern tech history. As an award-winning journalist who covered OpenAI years before ChatGPT became a household name, Hao brings unique insider access and perspective to this compelling narrative.

The book’s central thesis is provocative yet persuasive: that the AI industry, led by companies like OpenAI, operates with the same extractive logic as colonial empires of the past. Hao draws deliberate parallels between historical colonialism and what she terms “AI colonialism,” arguing that these companies seize and extract precious resources—artistic works, personal data, and human labor—to fuel their ambitious visions of artificial general intelligence.

A central focus on Sam AltmanAt the heart of the narrative is Sam Altman himself, portrayed as a charismatic yet polarizing figure whose optimism about AI’s transformative potential clashes with his pragmatic, sometimes ruthless business approach. Hao’s reporting, based on interviews with around 260 people plus correspondence and internal documents, reveals the complex dynamics within OpenAI’s leadership and the tension between the company’s founding nonprofit mission and its commercial ambitions.

One of the book’s greatest strengths is its global perspective. Rather than confining her analysis to Silicon Valley boardrooms, Hao examines the hidden human and environmental costs of AI development, from data centers in Chile to data workers in Kenya. This approach provides crucial context often missing from tech journalism, highlighting how the AI boom creates new forms of inequality and exploitation across the Global South.

OpenAI’s shift from nonprofit to capitalismThe timing of the book’s release in May 2025 allows Hao to incorporate the full arc of OpenAI’s transformation, from its nonprofit origins through the ChatGPT explosion and subsequent corporate restructuring. Her narrative captures the breathless pace of AI development while questioning whether this speed comes at the expense of safety, ethics, and global equity.

Hao’s writing is both accessible and urgent, making complex technical and geopolitical concepts understandable without sacrificing depth. The book succeeds in being both a corporate biography and a broader critique of how technological power is consolidated and wielded in the 21st century.

A strained central metaphorHowever, some readers may find the colonial empire metaphor occasionally strained, and the book’s focus on OpenAI, while deep, leaves questions about how other AI giants like Google and Microsoft fit into this framework. Additionally, the rapidly evolving nature of AI means some developments may already feel dated by the time readers encounter them.

“Empire of AI” stands as essential reading for anyone seeking to understand not just how we arrived at our current AI moment, but where we might be heading. Hao’s reporting reveals that the choices made by a small group of tech leaders will have profound consequences for global power structures, labor markets, and human agency itself. The book serves as both a warning and a call to action, suggesting that alternative, more equitable approaches to AI development remain possible—if we act soon enough.

This is investigative journalism at its best: rigorous, revelatory, and urgent. In an era when AI hype often drowns out critical analysis, Hao’s work provides the sober assessment we desperately need.

About the author Karen Hao giving a bookstore talk in 2025. Image: Wikipedia

Karen Hao giving a bookstore talk in 2025. Image: WikipediaKaren Hao has written about artificial intelligence since 2018. She worked as a senior artificial intelligence editor at the MIT Technology Review, then moved to the Wall Street Journal and The Atlantic. The Journal hired her in 2022 to report on Chinese technology from Hong Kong for a year. Today she freelances for many of the country’s most prominent magazines. She holds a BA in Mechanical Engineering from MIT. Hao is a native speaker of Mandarin Chinese as well as English.

For related readingYou’ll find many other views on AI at 30 good books about artificial intelligence.

For books about other companies and other business leaders and scientists, see:

My 10 favorite books about business historyScience explained in 10 excellent popular books12 great biographiesAnd you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post Will artificial intelligence help us or hurt us? appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

July 8, 2025

Inspector Chen confronts environmental crime in a Chinese city

Anyone who’s even dimly aware of events in China today understands that the country faces a host of pressing environmental challenges. For example, more than 100 of its cities languish under clouds of lethal air pollution. And “as much as 90% of the country’s groundwater is contaminated by toxic human and industrial waste dumping.” The latter is the underlying theme in the seventh novel in Qiu Xiaolong’s uniquely original series of mysteries featuring Chief Inspector Chen Cao of the Shanghai Police Bureau. When ordered to take a vacation on a lakeshore in the city of Wuxi (WOO-shee), he stumbles into a murder case that involves chemical dumping in the famously crystalline lake, now overgrown with green algae. Working undercover, Chen works with a local policeman to solve the murder. Meanwhile, he takes steps to expose the criminal dumping that has despoiled the lake.

On vacation, Chen investigates a murderAs you’re aware if you’ve read any of the preceding entries in this series, Chief Inspector Chen is a published poet. He’s also a “rising cadre” in the Communist Party, identified as a prospect for higher office. His patron is a retired senior official in Beijing. Now, around the turn of the 21st century, the old man insists that Chen replace him on a luxurious, two-week vacation in an exclusive resort for senior cadres. It’s on the shore of the famous Tai Lake.

Chen is reluctant to leave his work but has no choice. Bored with inactivity, he responds like the detective he is when he learns of the murder of Liu Deming. The victim is the general manager of the region’s largest chemical company, which is responsible for much of the pollution. Teaming with local detective Sergeant Huang Kang, a fan of his work and his poetry, Chen stays in the background, using him for the legwork.

The two detectives are up against Huang’s superiors in the Wuxi Police Bureau. But the real roadblock are the Internal Security officers who seize control of the case. Responding to political pressure, they have identified the killer as an environmental activist named Jiang. They allege he had feuded with Liu Deming about his company’s industrial dumping in the lake.

Don’t Cry, Tai Lake (Inspector Chen Cao #7) by Qiu Xiaolong (2012) 273 pages ★★★★☆ This water and soil turned red after being contaminated by industrial waste from a closed dye factory in China in 2014. In Don’t Cry, Tai Lake, the lake has turned green from algae growth caused by similar discharges. Image: Business InsiderA whodunit interlaced with a love story and a political theme

This water and soil turned red after being contaminated by industrial waste from a closed dye factory in China in 2014. In Don’t Cry, Tai Lake, the lake has turned green from algae growth caused by similar discharges. Image: Business InsiderA whodunit interlaced with a love story and a political themeDon’t Cry, Tai Lake is a whodunit. At first, the suspects in Liu’s murder include his wife, whom he may have been about to divorce, and Jiang. who was allegedly blackmailing the general manager. But Chen is skeptical. With Huang’s help, and some digging in Shanghai by his own partner at the Shanghai Police Bureau, Chen’s investigation turns up others who benefit from the man’s death. The top suspects are the assistant general manager who moves into the top job at the chemical factory and his “little secretary.” (“Nowadays a big boss, whether at a private or a state-run company, had to have a ‘little secretary’—a young girl who accompanied him in the bedroom as well as in the office.”) But the solution to the case doesn’t arrive until late in the day. The story is suspenseful to a fault before that point.

However, this novel is more than a simple whodunit pairing a brilliant detective with a crafty killer. In part, it’s a love story, as Chen falls for an attractive young woman who, like Jiang, is an environmental activist critical of the chemical company’s illegal dumping of its waste products. And the story offers opportunities for Chen (read: Qiu Xiaolong) to show off his command of classical Chinese poetry, and of his own. But, above all, Don’t Cry, Tai Lake, is an exposé of the Chinese Communist Party’s reckless disregard of the environment. The novel is a worthy extension of Qiu’s outstanding series of Inspector Chen mysteries.

About the author Qiu Xiaolong in 2016. Image: Wikipedia

Qiu Xiaolong in 2016. Image: WikipediaWikipedia describes Qiu Xiaolong as “a Chinese American crime novelist, poet, translator, critic, and academic.” And all those strands of his identity emerge clearly in the text of Don’t Cry, Tai Lake. Born in Shanghai in 1953, he has lived in the United States since 1988. In that year he traveled to St. Louis to write a book about T. S. Eliot. But he stayed after the Tiananmen Square Massacre, fearing arrest if he returned because of his foreign connections. Qiu had been a teenager and young adult during the Cultural Revolution and suffered greatly like millions of others. The event looms large in many of his Inspector Chen Cao novels. In addition to the 13 books to date in that series, Qiu has also written five other books and published seven volumes of Chinese poetry in translation.

For related readingI’ve also reviewed all six of the previous books in this series:

Death of a Red Heroine (A gripping Chinese police procedural)When Red Is Black (This gripping crime novel shows China in transition)A Case of Two Cities (A detective investigates corruption in the Chinese Communist Party)A Loyal Character Dancer (In a Chinese murder mystery, the legacy of the Cultural Revolution looms large)Red Mandarin Dress (As China changes, a serial murder case challenges the police and the Party) The Mao Case (Hunting the ghost of Mao Zedong in 1990s Shanghai)Check out The best mystery series set in Asia and 30 insightful books about China.

You’ll find other great mysteries and thrillers at:

30 outstanding detective series from around the worldTop 10 historical mysteries and thrillersTop 10 mystery and thriller seriesTop 20 suspenseful detective novelsAnd you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post Inspector Chen confronts environmental crime in a Chinese city appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

July 3, 2025

Tudor England comes to life in this brilliant historical novel

When C. J. Sansom died early last year at the age of 71, he left behind a series of seven outstanding historical novels set in the time of Henry VIII. Illness prevented him from continuing the series during the final years of his life. Otherwise, we might have followed his uniquely insightful mind well into the reign of Henry’s younger daughter, Queen Elizabeth I. Sadly, for Sansom’s final interpretation of the Tudor Era, we’re left with his seventh Matthew Shardlake novel, Tombland. But there is no better rendering of the critical time immediately following Henry’s death, when a regent for his young son, King Edward VI, ruled the realm and peasants throughout the south and west of the country rose in rebellion. It’s a masterpiece of historical imagination.

A turbulent time of popular unrestIn 1549, two years after the death of King Henry VIII, the consequences of his incompetence as a ruler were fully out in the open. The country was bankrupt, the coinage debased, taxes high, and inflation rampant. Compounding the problem for the rural poor, who constituted the majority of the population, wealthy landowners were “enclosing” the land to raise sheep, leaving hundreds of thousands to hunger and destitution. And making matters even worse for many, religious “reforms” laid down by the regent denied them a source of solace in their unhappy lives.

Of course, the 1,500 nobles who ran roughshod over England’s three million subjects were well insulated from the damage. And they could readily shift course from Protestantism to Catholicism and back again, as the situation demanded. But the opulence of their lifestyle, and the indifference most of them showed to the plight of the poor, enraged peasants and townsfolk alike. First in the west, then in the south and southeast, and finally spreading elsewhere, they rose in revolt. And nowhere was the rebellion more widely followed and better organized and led than in Norfolk, on England’s southeast coast.

Tombland (Matthew Shardlake #7 of 7) by C. J. Sansom (2018) 882 pages ★★★★★ Robert Kett leading the rebellion that bears his name to this day. Image: C L Doughty – The History of EnglandA convoluted murder case takes Matthew to Norfolk

Robert Kett leading the rebellion that bears his name to this day. Image: C L Doughty – The History of EnglandA convoluted murder case takes Matthew to NorfolkMatthew Shardlake knows he’s in for a rocky time when Lady Elizabeth summons him to her castle. King Henry’s younger daughter and third in line to the throne after King Edward and her sister Lady Mary, Elizabeth is a brilliant and assertive teenager. She calls on Matthew’s assistance as a troubleshooter from time to time. Now she needs his legal skills to help defend her distant cousin in Norfolk, John Boleyn. He’s accused of the brutal murder of his wife. Matthew’s job is to investigate the case, determine whether the man is truly guilty, and if not to assist his barrister in clearing his name. Matthew sets out for Norfolk in short order, his assistant in tow.

The murder case proves to be nettlesome. Boleyn appears to be guilty, but there are signs that’s highly unlikely. Several other suspects emerge, cast into suspicion by inter-family passions and land disputes involving powerful nobles in the region. However, Matthew is making good progress toward resolving the case in Boleyn’s favor when disaster strikes. Peasants in the region are rising in revolt.

This story revolves around Kett’s RebellionIn some parts of England, notably the southwest, the religious reforms imposed on churchgoers led to open revolt. But the causes of the rebellion in Norfolk and elsewhere in the south and southwest were largely economic. The enclosure movement was spreading rapidly, impoverishing thousands of peasants as the “gentlemen” and noble landlords grabbed their lands, erected fences, and imported sheep in large numbers to graze in place of growing food crops. In 1549, in Norfolk, a remarkable man named Robert Kett emerged as a leader of the revolt. Himself a minor landlord raising sheep, he tore down his fences and took the helm of the forces challenging enclosure. The events that followed in the ensuing months came to be known as Kett’s Rebellion.

At the rebellion’s peak, Kett led 16,000 men—and enormous force far larger than most armies fielded at the time. Among them were soldiers, veterans of the Scottish wars, who helped Kett and his older brother organize and train the men in the ways of battle. They were a formidable force, capturing the city of Norwich and defeating the first of the armies the regent sent to subdue them. Only months later, when he dispatched a larger and better-led army that included thousands of Swiss mercenaries did Kett and his force face defeat. They captured and later executed Kett, his brother, and other leaders of the rebellion.

Historical fiction at its bestSansom is a trained historian. He reads primary as well as secondary sources and the work of later scholars. All this comes to light in a lengthy and detailed historical note he appends to the novel. It’s a revelation.

In his summary of the extant research about Kett’s Rebellion, Sansom notes what’s lacking and what’s open to debate in the historical record. Much is uncertain, leaving the author opportunities to exert his imagination. For example, little is known about Robert Kett, although his skill as a leader is well established. But Sansom must imagine what he looks and talks like. And he deduces from multiple sources where certain key events in the rebellion took place, contesting the scholarly consensus.

But what is equally remarkable about Tombland and the six earlier novels in the Matthew Shardlake series is the great care Sansom devotes to exploring the conditions and the temper of the time. This is a long book, running to nearly 900 pages, and Sansom’s pacing is deliberative. He takes the time to convey in evocative prose how people spoke, what they ate, how they dressed, what they believed, and the day-to-day challenges they faced. And his description of the battle scenes renders all the blood and gore of fighting by sword and pike and cannon fire that gave Kett’s Rebellion its reputation as such a bloody episode in English history. You’re unlikely to find a better account of life during one of the seminal periods in the Tudor Era.

About the author C. J. Sansom. Image: Andrew Hasson – New York Times

C. J. Sansom. Image: Andrew Hasson – New York TimesThe late Christopher John Sansom (1952-2024) published seven novels in the Matthew Shardlake series from 2003 to 2018. He was working on the eighth when he died of bone marrow cancer in April 2024. Sansom also wrote two other historical novels, one set during the Spanish Civil War and an alternate history of England under Nazi rule. He was born in Edinburgh and educated at the University of Birmingham, which granted him both a BA and a PhD in history. He worked as a solicitor for most of his adult life.

For related readingI’ve reviewed all six preceding Matthew Shardlake books at The #1 top historical mystery series.

Check out the Guardian’s informative C. J. Sansom obituary.

You’ll find other great reading at:

Top 10 historical mysteries and thrillers25 most enlightening historical novels30 outstanding detective series from around the worldAnd you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post Tudor England comes to life in this brilliant historical novel appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

July 1, 2025

A royal scam in 15th century England

One day in 1480 a nameless nobleman and a priest show up at Will Collan’s farm. They’ve come for his 12-year-old son, John. As they explain to the boy, he’s not John Collan but a legitimate claimant to the English throne. As a small child, his partisans had hidden him away in the countryside to save him from his homicidal uncle, King Richard III. Now the priest would prepare him to take his rightful place as the country’s monarch. And this sets off a four-year saga that includes extended stays in Oxford with the priest, in Burgundy with his royal “aunt” to learn courtly manners, and in Ireland to prepare for the day when he would “lead” his troops against the usurper on the throne, the Tudor King Henry VII. Jo Harkin spins this tale in The Pretender, about a royal con job based in part on historical fact.

The historical basis for this storyThe Wars of the Roses came to an end in 1485 on Bosworth Field when the Welsh usurper Henry VII defeated King Richard III, who lost his life there. But, true to their nature, Richard’s partisans in the House of York and many of their allies refused to give up. One of them, a priest in Oxford, chanced upon a handsome boy of about 10 named Lambert Simnel (c. 1475-1535?). The priest, Richard Symonds, saw a strong resemblance to one of the “princes in the Tower.” They were the young sons of the late King Edward IV, who were legitimate claimants to the throne.

A pawn in a high-stakes gameSymonds concocted a wild story that the prince had been spirited away at a young age and raised in Oxford as the son of a craftsman there. The real prince, then, was supposedly Lambert Simnel, who became a pawn in an elaborated Yorkist plot to overthrow King Henry and place the boy on the throne under their control. To present him as the real Edward Plantagenet, 17th Earl of Warwick, they schooled him in reading, writing, and court manners after moving him to Dublin, Ireland. Two years later, bolstered by German mercenaries, they invaded England. At the Battle of Stoke they met King Henry’s army in a bloody encounter, which they lost decisively. The King’s forces captured Simnel, whom they recognized as a harmless dupe. Henry put him to work in the palace kitchens, where he worked for the rest of his long life.

The true story is buried in centuries of conflicting accountsWikipedia’s entry for Lambert Simnel is much more extensive and raises doubts about some of the scholarly Britannica article, which I used above. For example, “Simnel was born around 1477. His real name is not known—contemporary records call him John, not Lambert, and even his surname is suspect. Different sources have different claims of his parentage, from a baker and tradesman to an organ builder. Most definitely, he was of humble origin. At the age of about ten, he was taken as a pupil by an Oxford-trained priest named Richard Simon (or Richard Symonds / Richard Simons / William Symonds) who apparently decided to become a kingmaker.”

Whatever the details of this royal con job, Harkin bases The Pretender very loosely on the basic facts.

The Pretender by Jo Harkin (2025) 471 pages ★★★★☆ Illustration depicting the Battle of Bosworth Field, the decisive event that brought the Wars of the Roses to an end and entrenched the Tudor Dynasty. King Richard III is on the white horse. Image: BritannicaTaking liberties with history

Illustration depicting the Battle of Bosworth Field, the decisive event that brought the Wars of the Roses to an end and entrenched the Tudor Dynasty. King Richard III is on the white horse. Image: BritannicaTaking liberties with historyHarkin’s telling of the story in The Pretender adds years to John Collan’s life and depicts him spending long periods in Burgundy and Ireland as well as Oxford. In truth, he was probably rushed into place as the supposed Lambert Simnel when still no more than 10 or 11 years of age. After all, he was merely a figurehead for the rebels who adopted him. Making him an adolescent rather than a pre-teen gives her the opportunity to concoct a love story between John and a young Irish woman, the daughter of the Yorkist Earl of Kildare, who was effectively the king of Ireland. And that love story in many ways dominates the boy’s life for years to come despite their separation once her father discovers the connection. The historical record reveals no such affair.

Understanding the Wars of the RosesThere’s a lot of killing and dying in The Pretender. Of course, the story takes place during the Wars of the Roses, which was a bloody affair from beginning to end. During the three decades of that protracted conflict (1455 to 1487), four kings sat on the English throne: Henry VI, Edward IV, Edward V, and Richard III. And two of them traded places twice as legions of their partisans died in recurring battles. This was, after all, a time when politics was a game played for keeps.

Jo Harkin exerts little effort to explain the Wars of the Roses. But no matter. The event is beyond the comprehension of mortal human beings who are not minutely versed in the history of 15th century England. Most accounts of the period gloss over the reality by noting that the wars were a dynastic struggle between two rival branches of the Plantagenets, who ruled England from 1154 to 1485. Their mutually destructive civil war ushered in the Tudor Dynasty under King Henry VII (r. 1485-1509).

One of the warring parties was the House of York, whose symbol was the white rose. The other was the House of Lancaster (red rose). Hence, the Wars of the Roses. Seems simple enough, right? But it’s not. The whole thing started when the three sons of King Edward III, all of them Dukes, decided to fight it out for succession to the throne. Other prominent noble families took part as well. And many of the principal figures in the war frequently shifted their allegiance from one of the two “houses” to the other. For any casual reader, it’s hopeless to try to sort it all out. Suffice it to say that eventually the whole thing came to an end, and everybody lost.

An annoying writerly ticHarkin’s prose is generally lively and sometimes funny. She conjures up the cadence of speech in 15th century England by using archaic words and expressions. On the whole, it’s effective. Unfortunately, though, she gets carried away with the effort. Several of these words turn up repeatedly, and the repetition is disruptive. For example, on countless occasions you’ll find the word puissant or puissance, meaning powerful. Also, astonied, meaning dazed or dismayed. Dole (grief or sorrow). Jape (gibe or joke). And wroth (incensed or intensely angry). Admittedly, the meaning of most of these words becomes clear in context, at least eventually. But their repetition is annoying. There are good reasons why writers avoid repeating words again and again.

About the author Jo Harkin. Image: McCarthy Harkin – The Bookseller

Jo Harkin. Image: McCarthy Harkin – The BooksellerInformation online about Jo Harkin is spotty. Both Amazon and Google Books tell us that “Jo Harkin’s passion is literary sci-fi, with an emphasis on how new technology impacts human lives. Her first speculative fiction novel [was] Tell Me An Ending” (2022). . .” The Pretender is her second novel. She lives in Berkshire, England.

For related readingCheck out:

25 most enlightening historical novelsTop 10 historical mysteries and thrillers20 excellent standalone mysteries and thrillersThe #1 top historical mystery seriesTop 10 great popular novelsAnd you can always find the most popular of my 2,300 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

The post A royal scam in 15th century England appeared first on Mal Warwick on Books: Insightful Reviews and Recommendations.

June 25, 2025

How would the states have become united without the post office?

For many Americans today, the daily mail is a nuisance rather than a cherished service. Most advertising matter (and many bills) go straight into the trash. It’s been years since we wrote letters to one another. In fact, when we read how frequently authors, public officials, and family members corresponded 50 years ago or more, we marvel. How did they ever find the time? Letter-writing was a daily occupation for many literate Americans. And the post office was a lifeline, predictably delivering our letters, postcards, and greeting cards within a few days at most. We took that for granted. And precious few of us had any appreciation for the pivotal role “the post” had played in binding the states together and creating a national consciousness. That’s the subject of Winifred Gallagher’s exceptionally good history of the mail, How the Post Office Created America.