Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 16

December 14, 2022

The Wilderness Passage is Enacted in a Benighted State

We on our wilderness passage are blind. We’re acting out. We’re clueless.

I know I was.

I had no idea I was even in the wilderness, let alone that it was a passage. All I knew was that I was on a train and, no matter what I tried or how hard I tried it, I couldn’t get off.

This is as it should be.

“Now the word of the Lord came unto Jonah, saying, ‘Arise, go to Nineveh, and cry against it. But Jonah rose up to flee from the presence of the Lord … “

“Now the word of the Lord came unto Jonah, saying, ‘Arise, go to Nineveh, and cry against it. But Jonah rose up to flee from the presence of the Lord … “Consider the parameters of a Wilderness Passage.

The reason it starts for you and me is because we, in our ignorance, have pushed ourselves so far away from where we should be that the rubber band has snapped. Our own “life” (very definitely in quotation marks) has ejected us. We have blown up our marriage, lost our job, gotten sent to jail. Our own life has cast us out into the void.

By definition we are clueless.

By definition we are in denial.

If we weren’t in denial of who we really are, we wouldn’t have been kicked out into the wilderness in the first place.

In a way, this blog post and everything else I or anyone else mighty seek to communicate on this subject is wasted breath. The man or woman in the midst of their passage can’t hear us.

Again, this is as it should be.

The mouse in the maze has no choice but to bang head-first into all the walls. That’s how she learns.

And yet, as we said a few posts ago, we are not alone in this labyrinth. A goddess is with us. My old friend John McCown had a great metaphor for this. He said the goddess taps us first with a feather. When that doesn’t work, she swats us with a nerf bat. Then her bare hand, pow, across the face.

When that still makes no dent, she gets out the two-by-four and plants it full-force right between our eyes.

We wake up face-down in the gutter with an empty bottle of Jack Daniels beside us. “Oh? Really? I guess I DO have a drinking problem.”

In other words, the state of benightedness in which we pass through the wilderness is our own doing. Like Jonah in the Bible, we are in deliberate flight from that person, that calling, that gift that we know is us, is our truest and best self. We’re in flight for the same reason everyone is. Because it’s freakin’ SCARY to live out that person/life/gift!

Our passage through the wilderness will continue in blindness until we come face-to-face with something (whatever that Something may be) that is even scarier than being or becoming who were were meant to be—and who we have been all along.

P.S. My story of my own passage through the wilderness—GOVT CHEESE: A Memoir—became available for preorder on 12/6. Pub date: 12/30. Signed first edition hardbacks can be pre-ordered at www.stevenpressfield.com.

The post The Wilderness Passage is Enacted in a Benighted State first appeared on Steven Pressfield.December 7, 2022

Navigating without the stars

If you’ve ever studied land or celestial navigation, you know that both systems are based on reference points. From our frigate HMS Surprise off the coast of Patagonia, if we take a compass bearing on that headland off Rio Gallegos and another on the summit of Cerro Norte and scribe them both on a nautical chart, where the lines intersect is our position.

Russell Crowe in Patrick O’Brian’s “Master and Commander”

Russell Crowe in Patrick O’Brian’s “Master and Commander”We now know where we are.

You and I do the same thing every morning as we surface from sleep. “Ah, there’s my spouse next to me in bed … clock says 6:47 … dog is snoring on the carpet. Bathrobe. Slippers. Email …”

Each is a reference point. Each assures us that the Earth hasn’t spun off its axis during the night; we’re still alive and sane; life goes on in a manner with which we’re familiar.

A period “in the wilderness,” on the other hand, is by definition a passage without reference points.

Here’s a paragraph from my new memoir, Govt Cheese:

I wake up in my van. I don’t know where I am. I don’t know who I am. The reality of my existence is that my identity, if I ever had one, has dissolved. Goals. Do I have any? I can’t even conceive of the possibility. A purpose? To survive until tomorrow. I open the van’s side doors. It’s warm. I’m in a dirt turnout at the edge of a farmer’s field. Corn. Oh yeah, I’m in Iowa. Where, I have no clue. It takes me a moment to remember where I’m going. East? West? Where am I coming from?

Goals and a purpose are reference points too. They ground us. “Oh yeah, I’m doing this so I can get into Harvard!”

But in the wilderness, we don’t have those reference points. We are free-floating. We’re unmoored, unhinged, untethered.

And yet …

And yet, in many ways, the reason we have bungled or self-destructed or self-ejected our way into the wilderness, whether we realize it or not, is to blow up all points of reference.

We want to be lost.

We want to be cut free.

Why?

Because something was rotten in our prior state of Denmark. Our old reference points had led us to a dead end, a place of desperation (again, whether we realize this or not.) So we blow them up. We commit some crime/faux pas/outrage. We tell our boss to take this job and shove it. We bolt from our marriage. We join the Foreign Legion.

We leave the Ordinary World and step through the looking glass into the Inverted World. In this world, hatters are mad and every birthday is an Un-birthday.

It’s no fun to live without reference points. It’s hell. We wouldn’t wish it on our worst enemy. And yet, now that we’re here, there’s something exhilarating about the sheer formlessness and open-possibility-ness of everything.

We are free now to find new reference points. And with luck to locate our position on the chart in a place that we never knew existed but that is true, at last, to who we really are.

P.S. My story of my own passage through the wilderness—GOVT CHEESE: A Memoir—becomes available for preorder today! Pub date: 12/30. Signed first edition hardbacks can be pre-ordered right now at www.stevenpressfield.com.

The post Navigating without the stars first appeared on Steven Pressfield.November 30, 2022

The Shadow in the Wilderness

Last week we talked about our passage “through the wilderness” being imbued with meaning, i.e. not random, not absurd, not shameful, not meaningless.

Let’s dive into this a little deeper.

In Turning Pro, I wrote about “shadow careers.”

Sometimes, when we’re terrified of embracing our true calling, we’ll pursue a shadow calling instead. The shadow career is a metaphor for our real career.

Are you getting your Ph.D. in Elizabethan Studies because you’re afraid to write the tragedies and comedies you know you have inside you? Are you living the drugs-and-booze half of the musician’s life, without actually writing the music? Are you working in a support capacity for an innovator because you’re afraid to risk being an innovator yourself?

If you’re dissatisfied with your current life, ask yourself what your current life is a metaphor for.

That metaphor will point you toward your true calling.

“The wilderness” is a shadow calling.

The reason our lost years are loaded with meaning is because they’re a metaphor. It’s not random that one person becomes addicted (nor is it random, what they become addicted to), while another abuses his spouse and children. Hidden in each shadow is the Dream. Hidden is who the Dreamer truly is, what his or her true calling really is.

My wilderness/shadow was driving over the road—trucks, cars, whatever wheel I could get behind. Driving for me was mileage. Numbers on an odometer.

The (fake) idea that I was getting somewhere.

Ambition was my secret. I wanted to make something of myself. But I was too terrified to even realize it. So unconsciously I found a windshield to stare through and an accelerator to plant my foot on.

The metaphor for me was mileage. It was delivering a load.

The metaphor for me was mileage. It was delivering a load.Trucks for me was the metaphor. Because with trucks it wasn’t just driving, it was delivering a load. People were waiting for me. They wanted what I was bringing. They were happy when they saw my headlights come around the corner.

I had no sense of this “in the wilderness.” No clue. We’re blind to the meaning in the moment. We’re addicted. We’re not just imprisoned, we’re self-imprisoned. But the meaning is right there, staring us in the face.

I have a friend who’s an addiction counselor. The first time we went out to breakfast, he leaned across the table and looked me deep in the eye. “Are you sober?” he asked.

That was tremendously perceptive.

My friend saw the shadow in me. It isn’t alcohol, it’s self-sabotage. It’s Resistance.

That’s the wilderness for me. The only difference between me at twenty-eight driving over the road and me now is I see it now.

The meaning was there all along. It just took me a passage through the wilderness to see it.

The post The Shadow in the Wilderness first appeared on Steven Pressfield.November 23, 2022

Wilderness = Hero’s Journey

Why do we view our ordeals “in the wilderness,” in hindsight, in such a positive light? Why do people make such statements as, “It made me who I am today,” or “Excruciating as it was in the moment, I wouldn’t trade it for anything.”

I think it’s because this passage is our hero’s journey, in the best and most positive sense.

What is “the hero’s journey,” anyway?

Denzel Washington in “The Book of Eli”

Denzel Washington in “The Book of Eli”According to Joseph Campbell (not to mention Carl Jung), the hero’s journey is a universal rite of passage that most, if not all, human souls must undergo in real life. Jung called it a passage to “individuation”—to becoming who we really are.

Our ordeals “in the wilderness” are exactly that.

Consider the beats of the hero’s journey, as Campbell and Jung have put them forward.

1. The hero’s journey starts in the Ordinary World. The hero—male or female—is “stuck,” but he or she senses some powerful, tectonic energy moving beneath the surface.

2. The hero receives a “call.” This may be positive—an invitation to climb Annapurna—or negative … we’re arrested and thrown in jail. Or, like Odysseus, the hero commits a crime against heaven and is “made to” undergo an ordeal of expiation. But one way or another, you and I are ejected from Normal Life and flung, willy-nilly, into Something Totally New.

3. The hero “crosses the threshold.” She moves from the Ordinary World to the Extraordinary World (also known as the Inverted World.) Like the children in The Chronicles of Narnia, we pass through a portal and enter a realm unlike any we have known.

Is any of this ringing a bell?

4. The hero encounters allies and enemies, undergoes challenges and heartbreaks, temptations and overthrows. The hero suffers. The hero loses her way. The hero has been caught up in an often hellish adventure (though with some good moments too), from which no escape seems possible. The stakes are clearly life and death.

5. The hero perseveres. Reckoning that there’s no turning back, the hero pushes on, often blindly, almost always wracked by despair and self-doubt, seeking he or she knows not what. Escape? Redemption? A conclusion of some kind to this crazy, upside-down enterprise?

6. The hero comes face to face with the villain. The villain may be internal. It may be a creation of the hero’s own mind. Or it may be the Minotaur/the While Whale/Satan in the Desert of Judea. Whatever form this villain takes, the hero fights it tooth-and-nail, to the death.

7. The hero reaches an All is Lost Moment. The villain is too strong. The abyss yawns. All hope seems gone …

8. The hero achieves an epiphany. Often this takes the form of a surrender or an acknowledgment of a truth long-denied. “I can’t do this alone.” “Yes, I have a problem with alcohol.”

9. The hero races toward Home (whatever form that may take in his/her mind), clinging to his/her epiphany. The villain may be hot on the hero’s heels, or time and distance may have taken his place as the enemy …

10. The hero returns Home. But she is no longer the person she was when the passage began. Her ordeal has changed her, matured her, broadened and deepened her view of herself and of life.

11. The hero returns with a “gift for the people.” This may take the form of violent action, like Odysseus slaughtering the Suitors, or it may come gently, as music or poetry, to restore order and bring harmony to a disordered world.

The point of all this is that our passage through the wilderness is not random and not meaningless. It is a hero’s journey, in the best and most positive sense. It may not seem that way while we’re in it. In fact, it must seem bereft of meaning while it’s happening or it wouldn’t be “the wilderness.”

In fact, our passage is not merely touched by meaning but imbued to its very core. This doesn’t help, I know, in the midst of the ordeal. But it’s true, and we will know it, on every level, when the passage is at last complete.

The post Wilderness = Hero’s Journey first appeared on Steven Pressfield.November 16, 2022

A Goddess at our Shoulder

We were getting a little airy-fairy in our last post, speculating that some Unseen Cosmic Force of justice compels you and me onto our ordeals “in the wilderness.”

Let’s stay in the same lane today.

Let’s go back to the Odyssey and see what happens if we take Homer’s epic literally.

One of the aspects of the Odyssey that is often overlooked, probably because it’s so up-front and in-your-face, is that Odysseus throughout his ten-year ordeal is accompanied, aided, and advised by the goddess Athena.

More than once, when our hero washes ashore on some unknown isle, the goddess steps in to transform his appearance, making him look younger and more handsome so that he has a better chance of being welcomed by the inhabitants. Athena counsels Odysseus. She guides him. He pours out his woes to her and she responds with wisdom and kindness.

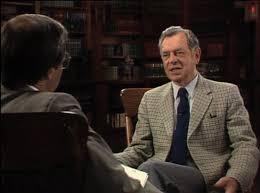

Joseph Campbell with Bill Moyers on the 1988 PBS series, “The Power of Myth”

Joseph Campbell with Bill Moyers on the 1988 PBS series, “The Power of Myth”What does this mean? Is it just a literary device? Did Homer really believe that the real Odysseus really did possess an immortal companion—a deity on the scale of Athena, for whom Athens was named and whose temple, the Parthenon, remains one of the architectural wonders of the world?

More importantly for you and me on our sojourns in the wilderness … do we have any help? From anywhere?

If some Unseen Force of justice compelled Odysseus onto his journey (and compels you and me on ours), could there also be a countervailing Force of Wisdom that can come to our aid as well?

You won’t be surprised, I’m sure, when I say I believe there is such a force … and that it is working for you and me even in—specifically in—our darkest moments. Here’s Joseph Campbell on what he calls “the hero path.”

We have not even to risk the adventure alone, for the heroes of all time have gone before us. The labyrinth is thoroughly known … we have only to follow the thread of the hero path. And where we had thought to find an abomination we shall find a God. And where we had thought to slay another we shall slay ourselves. Where we had thought to travel outwards we shall come to the center of our own existence. And where we had thought to be alone we shall be with all the world.

What Joseph Campbell means, as I understand it, is that on some higher or deeper level of consciousness, our ordeal “in the wilderness” has been laid out for us, like a map from a navigation app, and that signposts and constellations are already in place to guide us.

As we are “made to” stray grievously about the coasts of men, we’re also channeled infallibly, whether we believe it or not, into pathways that will serve us ultimately—even if we have no clue in the moment and even if, in reflection, we dismiss the whole process as hogwash.

Our time in the wilderness is our “hero’s journey,” complete with the acts of being cast out, the ordeal of wandering, and the return home.

I’ll go even further (with no evidence of course) from my own life. I believe that the people we encounter in our wilderness condition were guided to us, or us to them, for some unknown but mutually beneficial purpose. My upcoming memoir, Govt Cheese, is broken into eight books. Each one is named after a mentor—a boss, a teacher, a partner—all of whom appeared, as far as I can tell, at once randomly and also with cosmic purpose.

They were my “little divinities” and the actions they took toward me, whether they knew it or not (99% not), were the kicks in the ass and the pats on the back I needed—and at precisely the point I needed them. Not Athena maybe, but the next best thing.

The post A Goddess at our Shoulder first appeared on Steven Pressfield.November 9, 2022

Justice in the Wilderness

Today I want to get to my favorite—and the most provocative—phrase in that passage from the Odyssey that we’ve been examining for the past two weeks.

To refresh our memory, here’s the full text:

… the various-minded man who, after he had plundered the innermost citadel of hallowed Troy, was made to stray grievously about the coasts of men, the sport of their customs, good and bad, while his heart ached with an agony to redeem himself and bring his company safe home.

What part hooks me the most?

… was made to stray …

Specifically, “was made to.”

The Three Fates by Alexander Rothaug

The Three Fates by Alexander RothaugWho “made” Odysseus undergo his ten years in the wilderness? The translation I’m quoting from is by T.E. Lawrence, i.e. Lawrence of Arabia, who was an Oxford-educated Classical scholar and, for sure, no one to be imprecise. So …

If Odysseus, after he had committed a crime against heaven—plundering the innermost citadel of hallowed Troy—“was made to stray grievously etc.,” doesn’t that imply some cosmic engine of justice? The Fates? The Furies? Almighty Zeus himself?

Which brings up a Big Question. Is there in the fabric of the universe some scale-balancing force of Justice or karma or whatever we might choose to call it? Could this possibly be true? And if it is, did this entity somehow enforce punishment upon Odysseus?

We could say that something in the hero’s psyche—a sense of guilt or remorse perhaps—drove him himself to create his own ordeal. But that seems, to me at least, like an overly modern interpretation of this mysterious mechanism.

I believe there IS some force of Justice in the Cosmos. I believe Homer chose exactly the phrase and the sequence of crime and punishment he intended.

Our hero commits a crime against heaven.

No earthly tribunal judges him. Seemingly Odysseus gets away with it.

But some unseen force of payback or retribution intervenes. This force. by some mysterious means, sends storms to blow our hero’s ship off-course; it maroons him and his crew on god-forsaken isles. The force is always one step ahead of Odysseus. It buffets him from catastrophe to ordeal to disaster, foils his enterprises and stratagems, brings his most cunning designs to nothing.

Is any of this sounding familiar? In our own passages through the wilderness, yours and mine, isn’t there a feeling of some Cosmic Hand pushing us this way and that, tugging us back just when we seem to be making progress, shoving us over a cliff when we lapse even a little?

The good news—if this scenario contains any element of truth—is that our odyssey through exile POSSESSES MEANING. It is not random. It is not without significance.

If you and I have been “made to” suffer an ordeal of exile and banishment from ourselves, there must be meaning to it. Otherwise, why is some unseen force making us to stray grievously?

In other words, the mystery of our ordeal is not without a solution. The passage is not devoid of a culmination.

If you and I were made to stray, then there was a cause. Something we had done or failed to do. And hidden within that action or inaction was a violation of some law or precept. Not a human law perhaps, but a law that the gods know. And our way out, if this is true, can only be found in identifying this felony and coming clean about it, if only to ourselves—and then serving our sentence, doing our time.

Oh, by the way. If you and I are writing a story—any story, fiction or nonfiction—the scenario above is our spine.

The post Justice in the Wilderness first appeared on Steven Pressfield.November 2, 2022

Odysseus in the Wilderness #2

Let’s jump back into the Odyssey and see what else we can glean from Homer’s synopsis of his hero’s ordeal “in the wilderness.”

…. this song of the various-minded man, who, after he had plundered the innermost citadel of hallowed Troy, was made to stray grievously about the coasts of men, the sport of their customs, good and bad, while his heart, through all the seafaring ached with an agony to redeem himself and bring his company safe home.

Here’s my third takeaway from this passage:

… while his heart ached with an agony to … bring his company safe home.

Home.

All Odysseus wanted (and all you and I want on our passage) is to get home.

But what does “home” mean in mythic/legendary/metaphorical terms? It means that place where we belong. It means that sphere of action or contemplation that is our soul’s true epicenter. It means the Self we were born to be.

“A journey that’s homeward-bound”

“A journey that’s homeward-bound”So why did we leave home in the first place? Maybe we were too young or too deluded to see it for what it was. Maybe we were cast out, as in last week’s post, by a crime we had committed or that someone had committed against us. Maybe “home” had become intolerable to us or wasn’t ready for the self we wished to become. Maybe we were summoned away to an emergency of our own or of someone to whom we were obligated, as Odysseus was by Agamemnon to the siege of Troy. Or maybe we just dreamt of “something better.”

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

This is T.S. Eliot from Little Gidding, but it could have been Homer as well. For the Ithaca that Odysseus returned to after his ten years “in the wilderness” was not the same place he had left, nor was he the man he had been a decade earlier.

The point for me is that our odyssey, whatever form it takes, is not random. It’s not going nowhere. Herman Melville in White-Jacket wrote, “Life is a voyage that’s homeward-bound.”

Whether that’s true or not, or whatever meaning Melville intended, certainly our passage “in the wilderness” is a voyage whose ultimate aim is the discovery of our True Home, our authentic Self, the calling or love that is ours alone.

It’s interesting to me that the way Homer describes Odysseus’s ordeal is not in terms of physical torment, as, say, Prometheus bound upon his Rock or Sisyphus toiling on his hill. Rather, the poet phrases it as a passage whose pain comes from being far from home.

… was made to stray grievously about the coasts of men, the sport of their customs, good and bad …

If you’ll forgive me for digressing to Liverpool in 1965, here are a few verses from Gerry and the Pacemakers that I’ve always hoped to be able to say for myself.

The post Odysseus in the Wilderness #2 first appeared on Steven Pressfield.

So ferry ‘cross the Mersey

Cuz this land’s the place I love

And here I’ll stay

And here I’ll stay

Here I’ll stay.

October 26, 2022

Homer in the Wilderness

We suggested in the last two posts that some form of “sojourn in the wilderness” seems to be necessary for the evolution of the soul. Let’s check in, then, with the seminal myth of Western Civ on this subject: Homer’s Odyssey.

Odysseus’s ten-year ordeal in the aftermath of the Trojan War is the Ur-saga of this type of passage. There’s a reason the tale is still around, three thousand years after it was written.

” … the various-minded man …

” … the various-minded man …Let’s examine one specific passage. See if Homer’s verses below comport with whatever “odyssey” you yourself might be on right now (or have been in the past).

…. this song of the various-minded man, who, after he had plundered the innermost citadel of hallowed Troy, was made to stray grievously about the coasts of men, the sport of their customs, good and bad, while his heart, through all the seafaring, ached with an agony to redeem himself and bring his company safe home.

I don’t know about you, but that’s my wilderness story to a “T.”

There’s too much here to unpack in one post, so let’s start with just one takeaway (we’ll get to the others in subsequent posts):

” … after he had plundered the innermost citadel of hallowed Troy … “

In other words, the Odyssey starts with a crime. A crime committed by Odysseus. In story terms, this is the “inciting incident” that kicks off the great warrior’s ten years in the wilderness.

Note: Homer could have used any adjective (or none) to describe Troy. He could have said “windswept” or “glorious” or “doomed,” as he did in other contexts.

Instead he chose “hallowed.”

In other words, Odysseus has not just committed a crime but a crime against heaven.

Here’s my theory: I think ALL sojourns in the wilderness start with a crime. For sure, mine did. I hurt someone I loved deeply. That was what cast me out.

But every crime against another is really a crime against ourselves because, in committing that crime (and it may be one of omission as well as commission), we betray and violate the Self we were born to be. This crime is against heaven because the Self we’ve betrayed is that which the gods have vouchsafed us at birth as their noblest and most precious gift.

Let me jump ahead to the third of the five takeaways in this passage from Homer:

” … while his heart ached with an agony to redeem himself … “

The “criminal,” on his or her passage through the wilderness, knows he/she has done wrong.

Again, I don’t know about you, but that describes my feelings exactly on my own passage. I was excruciatingly aware, every second, that I had committed some betrayal, not just of another, but also of myself and of heaven (even though I refused to bring it specifically into consciousness) … and I wished like hell that I could atone and be released.

To be clearer on the definition of “crime”in this interpretation … the violation doesn’t have to be a literal felony or even a conscious act. The crime you and I commit may be one of naivete. We were clueless. We knew not what we did.

Our crime can be well-intentioned. We only tried to do what our parents/elders/tribe/religion told us was the right thing.

Or we may simply have failed to act. We took a job/enrolled in a school/married a spouse and stuck with this choice even though it was taking us—and others—straight to hell (and even if we were utterly blind to this.)

The crime, nonetheless, is against heaven, i.e. our Highest Self, the self we were born to be. And for that, we must pay, like Odysseus, by an ordeal “in the wilderness.”

More on this passage in Homer next week.

The post Homer in the Wilderness first appeared on Steven Pressfield.October 19, 2022

Wilderness = Exile

What do we mean in this series when we say “wilderness?”

We DON’T mean the positive, life-enhancing experience of a journey into Deep Nature, to Alaska or the Antarctic or the wild sea or the Himalayas. We mean “wilderness” as in lost. Alone. As in exposed and vulnerable to wild creatures and storms and floods and cold that will kill you. We mean “far from home and family and in serious peril.”

We mean exile.

In my own wilderness years I had no communication with my family, with my wife, my brother, my parents, with anyone. I was too ashamed of myself to write or call or reach out. And if others reached out to me, I ducked them.

That’s exile. The feeling of wilderness years is the feeling of being outcast. We are the black sheep. We are the bastard. We are the prodigal daughter or son.

The Doors

The DoorsIn wilderness years, we’re “a stranger in a strange land.” Remember that Doors song:

People are strange

when you’re a stranger.

Faces look ugly

when you’re alone.

Women seem wicked when you’re unwanted.

Streets are uneven, when you’re down.

And yet.

And yet, in some cosmically ineluctable way, the experience of feeling in exile is necessary. It’s indispensable to our evolution. Why? Because we, whether we realize it or not on our wilderness passage, are seeking to free ourselves from an Inauthentic Self. From who we were. From what others expected of us, even if those expectations were and are entirely well-meaning.

THAT’s what we’re in exile from. So when we encounter new people and they react to us as if we are strangers, “not from here,” as painful as that experience is in the moment, that’s exactly what we need. I’m thinking of a time for me in New Orleans, where I was totally a stranger. Nights on rainy streets in the French Quarter, then working on oil rigs in the Gulf. What was I doing there? Nobody knew me. And though I hated it, it cut me free from all conceptions of who I was or would be or could be.

When you’re strange,

faces come out of rain.

When you’re strange,

no one remembers your name,

When you’re strange,

When you’re strange.

Sometimes we need to be strange. We need to be “cast out.” We have to be in exile, so that we’re open to hearing such wisdom and imbibing such hard truths as we would never accept if we were not “strangers.”

We have to be desperate to face the truths about ourselves that we’ve been in denial of all our lives. That’s the sense that makes “wilderness years” so powerful and so productive.

The post Wilderness = Exile first appeared on Steven Pressfield.October 12, 2022

In the Wilderness

I’m thinking about my friend Gil, who served three years in prison.

That’s the wilderness.

Other mates have endured years-long ordeals enslaved to alcohol, drugs, trauma, PTSD, self-dramatization, toxic family dysfunction, you-name-it.

That’s the wilderness.

My friend Gil at Pro Camp, Gold’s Gym, Venice CA 9/28/22

My friend Gil at Pro Camp, Gold’s Gym, Venice CA 9/28/22Think about artists stuck in denial of their gifts … or too terrified to find or embrace their calling. Henry Miller worked for the phone company. Salman Rushdie toiled in advertising. Charles Bukowski labored for the post office. For years!

That’s the wilderness.

It seems that, one way or another, each of us must undergo a passage—internal, external, or both—of exile and estrangement from ourselves. I’ve touched on my own peregrinations in The War of Art and other books. I drove tractor-trailers, I picked fruit, I worked as an oilfield roustabout. I was lost lost lost. Yet in the end, when I finally emerged from this passage, I came to consider it the most fertile and cosmically-alive time of my life—and utterly indispensable to my evolution as a writer.

I’m starting a video series on Instagram on this subject. I’m calling it “In the Wilderness.” I’ll keep the videos short, and I’ll post them here as well as on IG, etc. weekly or maybe even more frequently.

Full disclosure: part of my motivation is to draw attention to an upcoming book of mine called GOVT CHEESE, a memoir of my “lost years” that I’ve always wanted to write but never found the guts to.

I’m also hoping that this video series will work as a standalone examination of this most critical (and creative) period in all of our lives—our years in exile from ourselves and from our calling.

P.S. Gil finished a second college degree (he already had one) while he was behind bars. He’s doing great now–and he has been for years. And for sure he’s never going back.

The post In the Wilderness first appeared on Steven Pressfield.