Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 13

August 9, 2023

Self-doubt, Part 4

A story from WWII:

In the early fighting in Southeast Asia, the Japanese were seriously kicking the British Army’s butt. Things had reached such a desperate pass that an entire division, including its Gurkha components, had to be airlifted 1500 miles to safety—an emergency evacuation, though smaller, nearly on a par with Dunkirk.

A Gurkha soldier of WWII

A Gurkha soldier of WWIIBut one Gurkha sergeant had been accidentally left behind. The poor guy was alone, with no radio, no compass. He had only his rifle and a map. The distance between him and his brothers-in-arms was unfathomable, across trackless jungle with which he was totally unfamiliar, to a needle-in-a-haystack place he had never been. He set off nonetheless.

Short version: nine months later, the Gurkha sergeant staggered into the base to which his division had been evacuated. He was barefoot, emaciated, sick with every kind of tropical disease imaginable. But he had miraculously made it! His mates swamped him ecstatically. His British colonel saluted him and made plans to honor his incredible achievement. Surely the sergeant’s feat was the greatest solo walking escape in the history of warfare.

The Gurkha sergeant spoke little English. but he was able to communicate his feelings to the colonel and his officers. He did not see his 1500-mile trek as particularly exceptional. After all, he said, “I had a map.”

He handed the map to the colonel. The paper was falling apart, the map itself torn and ragged and stained with jungle mud and dirt. “This is the map you used?” the colonel asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“The only one?”

“Yes, sir.”

The colonel held the map up for his officers to see. “This is a city map of London!”

Here’s the moral of the story, as I see it:

Self-belief (no matter how crazily-founded or materially divorced from reality) plus instinct plus grit may be the most powerful antidote to self-doubt.

The post Self-doubt, Part 4 first appeared on Steven Pressfield.August 2, 2023

Self-doubt, Part 3

There are certain skills that must be mastered by every writer, artist, entrepreneur, and athlete if she or he wishes to succeed. These skills are not taught in school. Many don’t even have a name.

These skills are not about craft. They’re about management of emotion. I’ve heard them called “soft skills,” though to me they’re anything but “soft.”

One of them is the ability to keep going when in the throes of desperate self-doubt.

John Keats, 1795-1821

John Keats, 1795-1821Keats called this skill “negative capability.” From a letter to his brothers, George and Thomas, in 1817:

I had not a dispute but a disquisition with Dilke (Charles Wentworth Dilke, a writer and editor whose home in London, Wentworth Place, is now called Keats House—a museum to the great Romantic poet), upon various subjects; several things dove-tailed in my mind, and at once it struck me what quality went to form a Man of Achievement, especially in Literature, and which Shakespeare possessed so enormously—I mean Negative Capability, that is, when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason … This pursued through volumes would perhaps take us no further than this, that with a great poet the sense of Beauty overcomes every other consideration, or rather obliterates all consideration.

My own poster boy for this skill is Christopher Columbus. Talk about uncertainties, mysteries, and doubts! “OMG, what if the world really is flat? Will my ships sail off the edge? No, that’s ridiculous. I know the world is round. But what if I miss the Indies? What if my course is too far north? Or south? Maybe the wise move is to sail back home … right NOW!!!”

The thing about soft skills like this—the ability to follow your vision when every cell in your body is revolting against this—is there’s no glamor to them. They’re boring. They’re quotidian. They’re the scenes we would cut out of a movie.

But they are the way we defeat our own Resistance.

Sit down. Get to work. Don’t stop.

Nobody gives you points for this stuff. No one cheers. No one even knows. The reason soft skills are so hard is they’re totally internal, producing no reward except that which we give ourselves.

A thought experiment:

Which writer/filmmaker/athlete/entrepreneur would you and I bet on?

The post Self-doubt, Part 3 first appeared on Steven Pressfield.

1. A one-in-a-million talent, but one who habitually faltered when confronted by self-doubt.

2. A far more modestly gifted performer, but one who could buckle up each day, no matter what emotional headwinds he or she was facing, and keep grinding.

July 26, 2023

Self-doubt, Part 2

We said in last week’s post that self-doubt was simply Resistance. And that the stronger it was, the more certain we could be that we were on the right track.

In other words, Resistance knows more than we do.

Resistance knows (don’t ask me how) how potentially good our work-in-progress is. By some infallible mode of calculation, Resistance can sense when you and I are onto something.

Its response: inflict us with self-doubt in inverse proportion to how potentially good our work might be.

The better the work-in-progress might be, the more Resistance we will feel to doing it.

But there’s another entity who also knows how good our work-in-the-making might be.

The goddess knows.

The Muse knows, even if you and I do not.

The Muse knows, even if you and I do not.When I was working on The Legend of Bagger Vance, I was absolutely certain that no one would be interested in it but me. Two weeks after I sent the manuscript in to my agent, we had a book deal—my first one ever. And a week after that, a movie contract was in the works.

I felt the same way about Gates of Fire. That was 1.2 million copies ago.

In other words, the intense self-doubt I was feeling in both cases was absolutely wrong.

Worse than that, it was an insult to the Muse.

The goddess knows what she’s doing, even if you and I don’t. Our job is to trust her.

No matter how intense the feelings of self-doubt we’re experiencing, we must keep plowing ahead. As Paramahansa Yogananda said about thoughts of faltering or giving in, “You must dismiss them!”

The goddess knows, even if you and I do not.

The post Self-doubt, Part 2 first appeared on Steven Pressfield.Self-doubt #2

We said in last week’s post that self-doubt was simply Resistance. And that the stronger it was, the more certain we could be that we were on the right track.

In other words, Resistance knows more than we do.

Resistance knows (don’t ask me how) how potentially good our work-in-progress is. By some infallible mode of calculation, Resistance can sense when you and I are onto something.

Its response: inflict us with self-doubt in inverse proportion to how potentially good our work might be.

The better the work-in-progress might be, the more Resistance we will feel to doing it.

But there’s another entity who also knows how good our work-in-the-making might be.

The goddess knows.

The Muse knows, even if you and I do not.

The Muse knows, even if you and I do not.When I was working on The Legend of Bagger Vance, I was absolutely certain that no one would be interested in it but me. Two weeks after I sent the manuscript in to my agent, we had a book deal—my first one ever. And a week after that, a movie contract was in the works.

I felt the same way about Gates of Fire. That was 1.2 million copies ago.

In other words, the intense self-doubt I was feeling in both cases was absolutely wrong.

Worse than that, it was an insult to the Muse.

The goddess knows what she’s doing, even if you and I don’t. Our job is to trust her.

No matter how intense the feelings of self-doubt we’re experiencing, we must keep plowing ahead. As Paramahansa Yogananda said about thoughts of faltering or giving in, “You must dismiss them!”

The goddess knows, even if you and I do not.

The post Self-doubt #2 first appeared on Steven Pressfield.July 19, 2023

Self-doubt, Part 1

Have you ever met a writer (usually a very young one) who tells you, “I love to write! I can’t wait to sit down each morning. I love everything about it!”

My first thought: “Either this guy is crazy … or he’s living in a dimension with which I am not familiar.”

Likewise, I’ve encountered writers who will tell you of their work-in-progress, “It’s dynamite! Readers are gonna love it!”

Again I think, “What planet does this dude inhabit? Because it sure ain’t the one I live on.”

“Wait till you see what I’m doing with Twitter. It’s gonna be FAN-tastic!”

“Wait till you see what I’m doing with Twitter. It’s gonna be FAN-tastic!”Here’s my mantra re self-doubt:

If I’m not crippled with self-doubt for at least the first nine months of a project (and sometimes a lot longer), something is wrong.

You and I should be feeling self-doubt.

We should be terrified.

1. Because self-doubt comes (often) from trying to second-guess readers’ response to what we’re writing.

We can’t do that. Nobody can. William Goldman was 100% right when he said, “Nobody knows anything.”

2. But the main freight of self-doubt is simply Resistance, i.e. our own self-sabotage. And the First Law of Resistance is:

The more important a project is to the evolution of our soul, the more Resistance we will feel to it.

In other words, self-doubt is good. Massive self-doubt tells us that our Resistance, sensing the positive power of the book/screenplay/painting/dance/symphony we are working on, has pulled out all the stops, trying to undermine us and make us give up.

When I ask a writer of her current project, “How’s it going?”, the answer I want to hear is, “I hate it … I’m so confused … I have no idea what I’m doing … this is going to be a disaster!”

If you and I ain’t feeling self-doubt, we ain’t working.

The post Self-doubt, Part 1 first appeared on Steven Pressfield.Self-doubt #1

Have you ever met a writer (usually a very young one) who tells you, “I love to write! I can’t wait to sit down each morning. I love everything about it!”

My first thought: “Either this guy is crazy … or he’s living in a dimension with which I am not familiar.”

Likewise, I’ve encountered writers who will tell you of their work-in-progress, “It’s dynamite! Readers are gonna love it!”

Again I think, “What planet does this dude inhabit? Because it sure ain’t the one I live on.”

“Wait till you see what I’m doing with Twitter. It’s gonna be FAN-tastic!”

“Wait till you see what I’m doing with Twitter. It’s gonna be FAN-tastic!”Here’s my mantra re self-doubt:

If I’m not crippled with self-doubt for at least the first nine months of a project (and sometimes a lot longer), something is wrong.

You and I should be feeling self-doubt.

We should be terrified.

1. Because self-doubt comes (often) from trying to second-guess readers’ response to what we’re writing.

We can’t do that. Nobody can. William Goldman was 100% right when he said, “Nobody knows anything.”

2. But the main freight of self-doubt is simply Resistance, i.e. our own self-sabotage. And the First Law of Resistance is:

The more important a project is to the evolution of our soul, the more Resistance we will feel to it.

In other words, self-doubt is good. Massive self-doubt tells us that our Resistance, sensing the positive power of the book/screenplay/painting/dance/symphony we are working on, has pulled out all the stops, trying to undermine us and make us give up.

When I ask a writer of her current project, “How’s it going?”, the answer I want to hear is, “I hate it … I’m so confused … I have no idea what I’m doing … this is going to be a disaster!”

If you and I ain’t feeling self-doubt, we ain’t working.

The post Self-doubt #1 first appeared on Steven Pressfield.July 12, 2023

Wilderness = Individuation

Forgive me if I keep coming back to the idea of a Passage through the Wilderness. I started this series of posts originally because I wanted to tie it in to my just-published memoir, GOVT CHEESE, which is about my own Wilderness Passage. But I keep coming back to the topic because it seems so central to all of our lives—and particularly our “hero’s journey” odyssey that leads us to our calling as artists and as human beings.

Carl Jung

Carl JungMost of us are familiar with Jung’s term “individuation.” It was, Jung always said, the goal and the object of any exercise in therapy.

In “the talking cure,” we work with a psychotherapist to explore the content of our unconscious as a means of stripping away all false or delusory selves with the aim of arriving ultimately at our true individuated self.

In real life, the world kicks the crap out of us until we arrive at the same place.

What the person in therapy is seeking is to answer the question, “Who am I?” And to take it to the next level: “How do I become that? How do I become who I already am?”

A Wilderness Passage, in our real lives for ourselves or in our fiction for a character we have created, is a real-world version of psychotherapy. It’s the psychotherapy of hard knocks.

Are we struggling with anxiety, depression, isolation, PTSD, addiction (of all kinds)? Are we a writer who doesn’t write, a painter who doesn’t paint, an entrepreneur who never starts a business? All these, if you ask me, are versions of the same question:

“Who am I?”

And the deeper corollary questions:

“What is stopping me from finding out who I am … and what is stopping me from becoming that?”

The passage itself is often the answer. Why do I have a problem with alcohol/porn/doom-scrolling? What does my anxiety protect me from? Why can’t I finish my novel/screenplay/dissertation?

The wilderness itself will teach us because it will break us down. We will run and run until we run out of bullshit. At that point—an All is Lost Moment—we’ll come face to face with Jung’s question.

For me it was, “I’m running from writing.”

Individuation for me was, “Sit the f*ck down and start writing.”

That was my answer to the question, “Who am I?”

When all the false selves and the runaway selves and the let’s-try-this-version-of-who-we-are selves have shot their wad and fallen to the wayside, what is left?

That’s individuation.

That’s who we really are.

The post Wilderness = Individuation first appeared on Steven Pressfield.July 5, 2023

Robert DeNiro sits in a chair

I was working on a screenplay a few years ago with director Andy Davis (The Fugitive, Under Siege, Above the Law) when he got an odd, dissatisfied look on his face.

“Something’s missing in this sequence. We need a Private Moment.”

I had never heard of a Private Moment. What could it be? I asked Andy.

He answered. “Did you ever see True Confessions? Remember the scene where Robert DeNiro goes back to his room and sits in the chair? That’s a Private Moment.”

Robert DeNiro as Monsignor Des Spellacy in “True Confessions”

Robert DeNiro as Monsignor Des Spellacy in “True Confessions”Let’s examine this.

A private moment, in a movie or a book, is a scene where a character (usually the lead, but not always) is alone with his or her thoughts. It’s a contemplative moment. It’s in a minor key. Almost always there’s no dialogue. Everything is communicated by facial expression, body language, or action. Often this is extremely subtle.

In True Confessions (1981), Robert DeNiro plays a rising young monsignor in the Los Angeles diocese. He’s not a priest who ministers to a congregation. He’s the right hand man to the powerful cardinal (Cyril Cusack). His duties include acquiring land for schools, hiring contractors, overseeing and trouble-shooting many of the financial and political intrigues that the diocese of necessity finds itself involved in.

He’s a fixer. An operator. He’s ambitious. One day, we imagine, he’ll be a cardinal himself.

The film is based loosely on the true-life “Black Dahlia” murder of 1947. Robert Duvall plays DeNiro’s brother, Det. Tom Spellacy, a jaded homicide cop investigating this horrific crime.

P.S. The screenplay is by Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne.

But back to DeNiro. In the scene immediately preceding his Private Moment, he’s on the golf course with some L.A. big shots, making deals for the diocese. He’s dressed in civilian clothes. He wields power. He’s driving hard bargains on behalf of the Church.

After golf, DeNiro returns to the residence he shares with other monsignors and high-ranking prelates. Here’s the scene:

DeNiro enters the residence in his civilian attire—slacks, a cardigan, a short-sleeved shirt. He mounts the stairs to a second story. The residence is like a dormitory. We glimpse in the hall several other priests. One passes in slippers and a bathrobe, carrying a towel and a shaving kit, apparently returning to his room from a communal bathroom.

DeNiro enters his own room and closes the door. The space is spartan in the extreme. A bed. A chair. An armoire. DeNiro opens the armoire. He hangs his cardigan sweater on a hanger. Inside the armoire are only one or two other items of apparel, on simple wire hangers.

DeNiro’s expression throughout is weary, self-reflective, melancholy. He seems to regard his surroundings and what they represent with a sense of defeat and futility, even despair.

He sits slowly on the single chair and looks pensively into nowhere.

That’s the scene.

What does it communicate? In the audience, we can’t be sure yet (and we won’t know until a few scenes later) but we sense that if DeNiro’s character were to articulate overtly what he is feeling (which of course he never would), it might go something like this:

“I entered the priesthood understanding the sacrifices I would have to make, exemplified by the barrenness of this room. I sought this humility deliberately, so that I could be of service to others, so that I could be a priest. Now look at me. I’m making deals like a gangster. What happened to me? I can’t go on like this.”

All this is communicated powerfully with no dialogue and absolutely minimal action. More importantly, because the scene is so spare of cues, the audience is drawn in and asked to read DeNiro’s interior experience without the aid of speech or other overt expression..

That’s a private moment.

P.S. The story I’ve heard (I can’t vouch for its veracity) is that this scene was not in the screenplay. DeNiro himself asked for it during the shooting. He felt something was missing. He felt his character needed a private moment.

The post Robert DeNiro sits in a chair first appeared on Steven Pressfield.June 28, 2023

At Norm’s Memorial

At my friend Norm’s memorial a couple of months ago, his son Matt got up to speak. Norm died at 94, so Matt was closing in on his own seventies. Here’s a story he told about his father.

Norm Stahl, who taught me the Foolscap Method. Photo by Sys Trier Morch.

Norm Stahl, who taught me the Foolscap Method. Photo by Sys Trier Morch.

“This was back in the ’80s. My Dad got a frantic phone call from his cousin. The cousin said, ‘Norm, I need 15 grand and I need it now. Today.’ Apparently he was in trouble from gambling.

“Dad came through, got him the money. This was when $15,000 was a fortune. Of course his cousin never paid him back. Years went by. They would see each other from time to time at family functions. It was always excruciating because everybody knew the story.

“Finally at one get-together … Christmas, Thanksgiving, I can’t remember … they were both there and the tension was terrible because they hadn’t spoken since forever. My Dad started across the floor toward his cousin. Everyone in the house was watching. Dad walked up, didn’t say a word. Just put his arms around his cousin and hugged him. Everybody started bawling. The spell was broken.

“That was the kind of man my father was.”

Remember, as you hear this story, that this was a son summing up his Dad’s life. Matt could have talked about success, achievement, family, whatever. But instead he chose this one story.

And it was perfect.

Here’s what I take from this. I’m sure that, over the years, Norm had many thoughts like these: “That deadbeat cousin of mine! We grew up together, played ball, chased girls. I came through for him when he was in desperate trouble, when it broke my own household bank. And he totally blew me off. He hasn’t paid me back and he’ll never pay me back. That sonofabitch!”

But then something changed. Norm must have thought something like this:

“What’s really important here? On my deathbed, am I gonna begrudge my cousin a few lousy bucks or a bad moment he once had under pressure? What counts is I love the guy. He’s my flesh and blood. Forget what he did. It’s nothing.”

In story-principle terms, Norm had an All is Lost Moment, followed by an Epiphanal Moment.

The change in Norm was he shifted from the ego to the soul. This is monumental. It’s the equivalent, if you ask me, of what the Buddha would call Enlightenment.

The ego holds grudges. The ego sees only its own self-interest. The ego hoards slights and grievances. The ego hates.

But the higher self sees soul-to-soul. It pierces the Little Picture and perceives what’s really important. It loves. It forgives.

All this is a long-winded way of getting to this question:

How does a Wilderness Passage end? How do you and I come out of a period of exile-from-Self and get our feet back on the ground?

I think we make the same transition Norm did, only instead of the shift happening in relation to another person, it happens within ourselves.

We perceive at last our own crimes and failings. We can say of ourselves, “What you did was unforgivable. It was a betrayal of all that you love and honor and hold dear. You failed yourself and your calling, grievously hurt those who love you, etc. But ya know what? It’s okay. It’s all right. I put my arms around you and hug you to my breast.”

An All is Lost Moment comes when our ego hits the wall. We cannot find a way around on that level. We must upshift to the plane of the Self, of the soul. This can mean resolving to change our lives, to make good on what we have previously crapped out on. Or it can mean a simple acceptance (as in the final scene of the movie, Big Night) of a reality that we cannot change but that, with love, we can live with and muddle through.

So I take my hat off to the son, Matt, for telling that story about his Dad. And I stand in even greater awe of Norm for how he resolved the issue with his cousin.

That was the kind of man he was.

The post At Norm’s Memorial first appeared on Steven Pressfield.June 21, 2023

A Hero of Mine

I don’t have many heroes, but one of them is Seth Godin. Do you know him? I’d try to pin Seth down in one phrase but the range of his work is so vast—from one of his early companies, Yoyodyne, through his ground-breaking books Tribes and Purple Cow and Linchpin (not to mention his educational masterpiece, the altMBA Program) and his current collective anti-climate-change enterprise, The Carbon Almanac––that the best I can say to describe him is “VISIONARY.”

My hero, Seth Godin

My hero, Seth GodinI follow everything Seth does, from his daily blog posts to every book and video and project he comes up with.

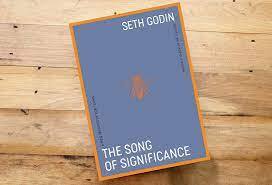

But this post is to give a shout-out to Seth’s newest book, out just last week, The Song of Significance. Two of the Evil Monsters that Seth regularly jousts with are Education—the factory-prep way we teach our kids—and Conventional Work—the jobs that our race-to-the-bottom economic culture holds out to us as ways of making a living. Ugh!

The Song of Significance is aimed at an audience caught in one or both of these hellholes, but it’s equally applicable (maybe more so) to those of us who are either independent operators or are striving to be independent artists/writers/filmmakers, etc.

I think of Seth sometimes as a Periclean Athenian. What I mean by that is that his ideal man or woman (and he walks this walk himself) embodies that Classical-citizen self-autonomy that I at least associate with the original democratic Golden Age. Seth’s ideal is the self-contained individual, who knows her own mind, who holds herself to a high moral standard, whose work is aimed at service to the greater community and to the planet, and who follows the calling she was born to be and to become without the need for societal approval or third-party validation. That’s a mouthful, I know. It’s what Seth means in this new book by Significance.

Can we, Seth asks, find in our lives, work, and family not just meaning … but our meaning? And how can we live it out within cultural and economic environments that are indifferent to such an aspiration, if not outright hostile?

The Song of Significance by Seth Godin. Five stars. Check it out!

Five stars, baby!

Five stars, baby!On another, semi-related note, the thirteen short videos I did for Instagram about “The Foolscap Method”, i.e. how I start a book or movie … are now available on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL_6twVl5XOXvZiV4JEPiwr1GeslgHj4NQ.

They’re free, they’re all in one place. You can start at Episode 1 and scroll straight through to Episode 13. I will almost certainly at some point put these ideas together into a book, but for now you can get a pretty full picture at the link above.

The post A Hero of Mine first appeared on Steven Pressfield.