Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 14

May 3, 2023

Badge+Gun #2

David Baldacci is the mega-million bestselling author of Absolute Power, The 6:20 Man, Simply Lies, and many more. Here is his All Is Lost Moment and Epiphanal Moment (my interpretation, not his) derived extremely loosely from his MasterClass on Mystery and Thriller Writing (which I highly recommend.)

David Baldacci

David BaldacciMr. Baldacci was a successful lawyer, but his dream was to be a writer of fiction. The short version is after many tries and near-misses, he arrived at one final disappointment that convinced him his dream was never going to come true. In other words, an All Is Lost Moment.

For days, David Baldacci struggled with despair. Was he doomed forever to be a lawyer and nothing more? Then he had an epiphany.

He decided not to fight what he considered the verdict of the marketplace. Heartbreaking as it was, he yielded to what the Big Publishing Suits told him.

But, he said to himself, “I don’t care.”

“Okay,” David Baldacci declared to himself, “I might never see a novel of mine in print. Hollywood may never make a movie based on one of my yarns. But that will not stop me. I’m a writer,” he said, “and I’m going to keep writing. I don’t care if Random House or Simon & Schuster never publish my stuff. Life is unbearable for me if I can’t write. So I’m going to keep writing, success or no”

Why is this a Badge+Gun moment?

Remember, in the classic Cop Story idiom, when your boss takes your shield and your Smith & Wesson, he is yanking your mainstream credibility. You no longer have the full force (or any force at all) of the law behind you. But he, your supervising honcho, cannot take your moral credibility. Only you control that.

In The French Connection or The Silence of the Lambs or any of a thousand other Good Guys versus Bad Guys epics, the shorn detective keeps on going. He or she stays on the case, even at peril to his or her own freedom or worse.

That’s what David Baldacci did.

He dismissed what he believed at the time to be the verdict of the mainstream marketplace. He decided to pursue the case on his own.

There’s a happy ending to this story. David Baldacci kept writing. And it turned out that his All Is Lost Moment was a false alarm. He was a good writer. Readers did clamor for his books. He did realize his dream.

But the critical moment, for his own soul (and for the goddess), was when he turned in his badge and his gun and kept on writing anyway.

The post Badge+Gun #2 first appeared on Steven Pressfield.April 26, 2023

“Turn in your badge and your gun.”

I was working on the screenplay for the Steven Seagal movie, Above the Law. I forget who first said this—maybe Steve, maybe the director Andy Davis—but someone piped up, “We need a ‘Turn in your badge and gun’ scene.”

I remember thinking, “Oh no, what a terrible cliche! It’s in every cop movie. We can’t be that lame!”

Even Clarice Starling got yanked off the case.

Even Clarice Starling got yanked off the case.But of course Steve (or Andy) was right. It was not a cliche. It was a critical All is Lost Moment, in fact it was the All is Lost Moment.

Why is this moment so important? Because it calls forth from the story’s hero an Epiphanal Moment, i.e. his or her response to a make-or-break, life-and-death crisis. It reveals the hero’s true character.

It took me a while to grasp this, but when I finally did, I recalled to myself that even classic films and books are not too proud to have this exact moment. In The French Connection, Popeye and Cloudy are pulled off the case. In The Silence of the Lambs, Clarice Starling gets her credentials yanked. Even in Top Gun: Maverick, there’s an equivalent scene—when Jon Hamm fires Tom Cruise and takes his flying stripes “permanently.”

In the latter two cases (and in Above the Law), the heroes totally blow off their dismissals. They keep going on their own. And this shows us in the audience that they are driven, committed, all-in. They are real heroes. (In The French Connection, it’s an outside event—the bad guys trying to kill Popeye by ambushing him outside his apartment building—that gets our heroes put back on the case.)

What’s happening in a badge-and-gun moment is the hero, who had heretofore been pursuing his or her objective with the full backing of society or the institution in which he or she serves, suddenly gets her papers pulled. She’s now on her own, a totally free agent. Worse, she’s now been forbidden, under severe penalty, to pursue her object. Will she do it anyway? If she’s a hero in the best movie/novel/legend/myth sense, we already know the answer.

When I’m working on a new story now (thanks, Steve and Andy, for teaching me this), I always ask myself, “Do I have the equivalent of a Badge-and-Gun Moment?” And if I don’t, I’d better have a damn good reason for not having it.

An All is Lost Moment (of any kind, not just the badge-and-gun variety) should always ask the hero, “How much do you want what you want?” (Love, redemption, saving the world, etc.) Most of us in real life would answer, “Not enough to risk my life/family/career/soul.” But a hero will always come out at, “I want it so much I’ll do ANYTHING.”

More on this next week.

The post “Turn in your badge and your gun.” first appeared on Steven Pressfield.April 19, 2023

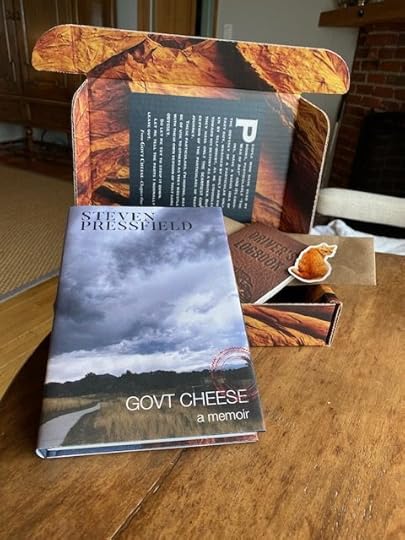

A Thank-you for “Govt Cheese: A Memoir”

Let me take a break from our Wilderness Passage posts to say a quick thank-you to everyone who ordered a signed copy of Govt Cheese: A Memoir. We’ve sent out twelve hundred so far, all packed by hand and trundled to the UPS store (actually a bunch of stores), in the VIP pack pictured below.

The VIP pack with a signed first edition

The VIP pack with a signed first edition(We just got a fresh 250 in, all first editions, still available for order here.)

For all of us who are indie authors or are thinking of becoming one, this VIP pack is a really interesting idea.

I first saw one from my friend, the thriller writer Jack Carr. For his fourth book, Savage Son, Jack put together a gift box—not for promotion but just for friends who had helped him on his journey. He mailed about a hundred of them. The outside of the box was designed colorfully, with FIRST EDITION on the spine. Inside Jack put a bunch of fun-type premiums—a cocktail coaster, a refrigerator magnet, a note of thanks from him (there was even a little utility knife), and a few promotional items from his sponsors. And of course the first edition itself, signed.

I got one. It was a real giggle. I wound up doing a video “unboxing” on Instagram, as did many others who received the package.

I’m not sure how much this helped Jack’s sales, but it certainly didn’t hurt.

When we—my better half, Diana, and I—were considering how to bring out Govt Cheese so that it might get a little attention, we thought, “Let’s do a VIP pack. We won’t tell anyone it’s coming. It’ll be a surprise when it arrives via UPS.”

A VIP pack can be a big hit, particularly when the recipient doesn’t know it’s coming.

A VIP pack can be a big hit, particularly when the recipient doesn’t know it’s coming.We hoped to get a few unboxings ourselves.

Two bottom lines from this:

One, if you’re an indie author like I am, consider doing this—if not on your next book (or album or announcement of any kind), then on the proper item when it comes up down the line. It’s not cheap and it’s a lot of work. But it’s fun. And it’s definitely appreciated by those who receive it, particularly if they don’t know it’s coming and are expecting only a box with a signed book inside.

And two, if you’d like a VIP pack of Govt Cheese yourself, we’ve still got 250 of them. Click here and we’ll get one out to you right away.

The VIP pack won’t be a surprise but, trust me, it’ll still be fun.

Thanks again to all who ordered!

P.S. Govt Cheese: A Memoir is my story of my own “wilderness passage”—in gory detail, all twenty-seven years of it.

The post A Thank-you for “Govt Cheese: A Memoir” first appeared on Steven Pressfield.April 12, 2023

Escaping the Wilderness

Does escape from our personal Wilderness always entail a gruesome All Is Lost Moment? Must we hit bottom before we can come back up?

I don’t think so. But the answer, it seems, always involves deep and serious introspection.

It could be psychoanalysis (of the talking kind, not the pharmaceutical) or its equivalent. Meditation perhaps. A mentor. A spouse. A friend. An ally who can provide the perspective (and the psychic safety) for us to face the demons we’ve been in denial of our whole life.

Or, if we’re really exceptional, we can do it on our own, looking deeply within.

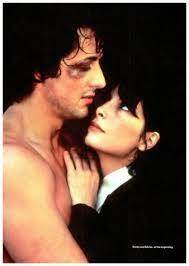

Sylvester Stallone and Talia Shire in “Rocky”

Sylvester Stallone and Talia Shire in “Rocky”There’s an axiom in screenwriting that the All Is Lost Moment is embedded in the Setup.

Another way to put this is, “Your shrink gets your craziness in the first session. He or she could spell it out for you right then, but they won’t because they know you’ll only reject it. You need to come to it on your own.”

Consider Sylvester Stallone’s script for Rocky. We see in the opening scenes (the Setup) that Rocky’s issue is that the world sees him as “a bum”—and, worse, he agrees. Everything in Rocky’s life, from his horrible apartment to his job as a bone-breaker to his locker at the gym reinforces the psychic reality of his bum-hood. In the audience, we sense that Rocky, if he’s going to save himself, is going to have to come to a crisis point where he must confront this—and make the decision to overcome it.

Here’s that moment, the Epiphanal Moment, from just before Act Three:

ROCKY

…it’s true, Adrian. I was nobody. But that don’t matter either, you know? ’Cause I was thinkin’, it really don’t matter if I lose this fight. It really don’t matter if this guy opens my head either. ’Cause all I wanna do is go the distance. Nobody’s ever gone the distance with Creed, and if I can go that distance, you see, and that bell rings and I’m still standin’, I’m gonna know for the first time in my life, see, that I weren’t just another bum from the neighborhood.

In Rocky’s case, he needed an All Is Lost Moment. He needed that Big Crash to give him the desperation to reach an Epiphany. But theoretically he could have come to that realization on his own or with assistance—as we said, a shrink, a mentor, a spouse, a friend—and, little by little, self-revelation by self-revelation, peeled back the onion till he came to its core.

There’s a word for this capacity.

Wisdom.

I didn’t have it in my own life, that’s for sure. I needed to hit bottom.

But that moment is not inevitable. I salute anyone who can get there on his or her own. God bless you. That’s guts. That’s insight.

That’s wisdom.

The post Escaping the Wilderness first appeared on Steven Pressfield.April 5, 2023

The feeling that it will never end

One of the primary characteristics of any “passage through the wilderness” is the excruciating belief/certainty, while we’re in it, that it will never end. We have been given a life sentence, we believe, without possibility of parole.

Are we addicted to alcohol or drugs? We can’t conceive of ever being able to stop. Are we in bondage to some toxic, soul-devouring relationship, profession, or conception of life? We believe we have no power to escape. PTSD? Anxiety? Compulsive self-sabotage? We’re powerless to break free, we believe.

We’re in denial when we’re in the wilderness. At least that’s how we respond when someone calls us on our bullshit. “I’m fine, man.” “I’m all right.” “Worry about yourself, brother!”

Tom Hanks in “Cast Away”

Tom Hanks in “Cast Away”How dangerous is our Wilderness Passage? It’s life-and-death dangerous. In the movies, heroes “make it out alive.” In real life, you can go down and never come back up. How many casualties can each of us count among friends and family? Remember Hemingway’s famous quote from A Farewell to Arms:

The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.

I’m not a believer that just because Ernest Hemingway said something, it’s necessarily true. But he certainly was onto something in this case, at least in the sense of how this passage feels.

The feeling that this agony, this exile will never end, excruciating as it is, is critical in a good sense because it reinforces for us the fact that the stakes are life and death. Which they are. There’s no guarantee that you or I—or anybody—will survive their ordeal in the Wilderness.

And yet people do survive. If you thought it was only a “passage,” while you were in it, it wouldn’t scare the crap out of you like it’s supposed to. In order for our ordeal to do its work, we have to believe completely (and we do, because it’s true) that our soul is in mortal danger and we must rally every resource to survive.

The post The feeling that it will never end first appeared on Steven Pressfield.March 29, 2023

After the Wilderness

Our passage through the Wilderness may involve action worthy of the next John Wick movie. We may survive IEDs in Afghanistan, divorces in Reno, stretches in Joliet or in a cubicle at Facebook. We may find ourselves brawling in bars in Ibiza, pursuing lovers across the Pampas in Argentina. We may wake up with strange tattoos, or beside even stranger bed-mates. Entire decades can go missing during our Wilderness Passage.

Keanu Reeves in “John Wick 4”

Keanu Reeves in “John Wick 4”But when we finally turn the corner—when we reach our All Is Lost Moment, followed by our Epiphanal Moment—all that adventure shifts.

It goes inside.

Our life becomes, now, about the work—the work we’ve been running away from all that time in the wilderness.

Dalton Trumbo wrote his best stuff in the bathtub. Churchill the same. Marcel Proust barely got out of bed. Even Hunter Thompson, mythology aside, took his orange juice straight when he settled down at the keyboard.

Me? The odometer on my ’65 Chevy van ticked over the six-digit mark so many times I can’t remember them all. That was during my hero’s journey.

Now on my Artist’s Journey I barely drive to the grocery store.

The post After the Wilderness first appeared on Steven Pressfield.March 22, 2023

The All Is Lost Moment in Nonfiction

Can there be an All Is Lost Moment in nonfiction?

Here’s an example from The War of Art, which is definitely not fiction.

The hero of The War of Art is the reader. I’m imagining this individual—male or female—to be an aspiring writer/artist/entrepreneur/human being.

The All Is Lost Moment happened before the reader/hero picked up the book. That moment (perhaps many, many moments) was constituted of the realization by the hero/reader that he or she possessed (perhaps in secret) a dream of creative fulfillment or self-realization that he/she had never fully committed to … and that his/her life had been disfigured emotionally and psychologically by this failure to take action in pursuit of that dream.

That’s the All Is Lost Moment.

What’s the Epiphanal Moment? Hopefully it occurs during the reading of The War of Art (or at some point thereafter), when the reader says to him or herself, “I’ve had enough! I can’t go on like this! One way or another, from this moment forward, I’m going to pursue my dream and my calling!!”

Elizabeth Gilbert from her TED talk, “Your Elusive Creative Genius”

Elizabeth Gilbert from her TED talk, “Your Elusive Creative Genius”Here’s a second example. This one comes from Elizabeth Gilbert’s 21-million-view TED talk, ‘Your Elusive Creative Genius.” In the talk, Ms. Gilbert tells her own story of a moment of personal crisis (in other words, nonfiction) that she experienced after the runaway success of Eat Pray Love.

The All Is Lost Moment was the coming together of her fears (reinforced by the concerns of others) that she could never top that hit, that she would spend the rest of her life banging out books and other creative projects and never, never produce one that rose to the artistic/commercial level of Eat Pray Love.

That’s the All Is Lost Moment.

What’s the Epiphanal Moment (again, in real life, in nonfiction)?

“And what I have to keep telling myself when I get really psyched out about that is don’t be afraid. Don’t be daunted. Just do your job. Continue to show up for your piece of it, whatever that might be. If your job is to dance, do your dance. If the divine, cockeyed genius assigned to your case decides to let some sort of wonderment be glimpsed through your efforts, then ‘Olé!’ And if not, do your dance anyhow. And ‘Olé!’ to you, nonetheless… for having the sheer human love and stubbornness to keep showing up. “

Ms. Gilbert’s epiphany was not some stroke of brilliance that guaranteed that she would top Eat Pray Love. Quite the opposite. Ms. Gilbert accepted that likely reality. But she added, “I don’t care.”

I’m a writer, Ms. Gilbert said to herself, and I’m going to keep doing my best at that craft and that calling. Come what may, I can do no more. And that, brothers and sisters, is enough.

So indeed, there can be (and, in my opinion, should be) an All Is Lost Moment and an Epiphanal Moment in our self-help book, our Substack post, our biography of our sainted aunt Hilda, and, yes, in our TED talk.

The post The All Is Lost Moment in Nonfiction first appeared on Steven Pressfield.March 15, 2023

My All is Lost Moment

The year was 1980. I was living in New York and driving a taxicab. The short version is I finished Novel #3 and couldn’t sell it (much like Novels #1 and #2.)

I was thirty-seven years old. My entire life, from twenty-four on, had been devoted either to writing fiction, working so I could afford to write fiction, or running away from writing fiction. I thought now, “There’s no way I can put in another five years, saving money and then writing, to try to do Novel #4. I just don’t have it in me.”

My All Is Lost Moment was kinda like this guy’s.

My All Is Lost Moment was kinda like this guy’s.That was not my only All Is Lost Moment up to that point, but it certainly was the biggest and the scariest. From GOVT CHEESE: A Memoir:

For four days I’m seriously teetering. My cat has stopped going outside. He’s looking at me funny. Clearly he’s thinking, “How am I gonna clean up the mess after Steve blows his brains out? Or get him down from the hook when he hangs himself ?”

That’s the All Is Lost Moment. Here’s the Epiphanal Moment:

Then at the fifth midnight I have a flash.

Why don’t I try writing screenplays?

I’ll move to LA. Why not? I’ve failed as a novelist. Why not go out there and fail as a screenwriter?

My friend Jennifer has worked as an assistant to a Hollywood agent. I phone her at one in the morning.

“You have to write a sample,” she says. “A screenplay on spec. No agent’s gonna take you on without something they can show around.”

Next morning I’m standing in the dark outside Barnes & Noble waiting for the doors to open.

I buy a $3.95 paperback, “How to Write a Screenplay.”

All Is Lost Moments happen in real life, and they follow the same principles as All Is Lost Moments in books and movies.

Sometimes the answer to an All Is Lost Moment is to give up a dream that can never come true, at least not for the present moment. Sometimes the answer is to embrace reality, even if—especially if—that reality breaks your heart.

It was no small thing for me to give up on the dream of writing a novel. That was my whole fantasy identity. And I certainly had no illusions that I was going to set the town on fire in Tinseltown. But to drop back to an aspiration that was (slightly) more realistic at least gave me hope. I got me down from that hook on the ceiling.

My epiphany was like Rocky’s, “If I can only go the distance … “

Rocky’s breakthrough self-assessment was, “I might not be able to fight or box or compete on the championship level. But goddamit, I can take punishment. That, I can control. All I have to do is keep getting to my feet when they ring the bell for the next round.”

In my case, as it turned out (not without irony), my moving to Hollywood proved to be the step—fifteen years later–that finally helped me get a novel published.

That was my All Is Lost Moment. And my epiphany.

P.S. Signed hardcovers of “GOVT CHEESE: A Memoir” are still available here.

The post My All is Lost Moment first appeared on Steven Pressfield.March 8, 2023

Ego and Self in the All is Lost Moment

Why do we (so often) need an All Is Lost Moment in our own lives to break through to another level? Can’t we just do it at a happy time? Do we have to push ourselves to the absolute abyss in order for real change to sink in?

I hate to say it, but that seems to be true. Certainly it has been in my own life. And for sure it’s true in fiction.

In fact, we might define “wisdom” as the ability to transform oneself to a higher level WITHOUT going through an All Is Lost moment. Have you done this? Neither have I.

I think the reason is that in an Epiphanal Moment, the epicenter of our psyche shifts from the ego to the Self. That’s the definition of an Epiphanal Moment. And the nature of the ego is to hang onto the steering wheel with everything it’s got. You and I (or Life itself) have to pulverize that SOB before it’ll let go.

Stanley Tucci and Tony Shalhoub (with Marc Anthony) in “Big Night”

Stanley Tucci and Tony Shalhoub (with Marc Anthony) in “Big Night”Here’s another All Is Lost/Ephiphanal Moment—this one from the movie Big Night (1996). Have you seen it? It’s a great one. Starring Stanley Tucci and Tony Shalhoub, with Minnie Driver, Isabella Rossellini, Campbell Scott, Ian Holm, Marc Anthony, and Allison Janney.

Big Night is about two brothers recently emigrated from Italy—Primo (Tony Shalhoub) and Secondo (Stanley Tucci)—whose restaurant in 1950s America is struggling desperately to survive. The problem is that Primo, a genius chef, refuses to compromise his integrity by dumbing down his cuisine … and the mac-and-cheese US palate isn’t ready yet to embrace his lofty standards. The crisis comes on one “big night” when the brothers prepare an all-out feast anticipating the visit of famous bandleader Louis Prima—and Prima fails to show. The whole idea, it turns out, was a ruse by a rival restaurateur to drive Primo and Secondo out of business.

The All Is Lost Moment comes at the end of this desperate night—in a slap-happy brawl on the beach between the two brothers.

PRIMO

(in Italian with subtitles)

I have tried to teach you, Secondo … but you’ve learned nothing! Why do you want to stay here? This place is eating us alive! If I give up my art, it dies. Better I should die.

Primo staggers off with his new girlfriend Allison Janney. The brothers part. They’re broke. They’re too proud to work for anyone else. And any new restaurant they might open is sure to fail as their current one has. The situation is definitely All Is Lost.

Now comes the Epiphanal Moment.

The morning after. Restaurant kitchen. Secondo enters. The mood is bleak. Marc Anthony, the busboy, is asleep on the butcher block table. Secondo gets down a skillet from an overhead rack. Marc Anthony rises, steps to the side. Without a word Secondo prepares an omelet for himself and Marc Anthony. Secondo sits at the butcher block and begins to eat.

The Epiphanal Scene in “Big Night”

The Epiphanal Scene in “Big Night”Now: Primo enters. Still in his chef’s white jacket from the night before. Primo says nothing, simply stands there. Secondo glances uneasily to his brother. Then he rises, gets a plate down from the shelf, spoons a portion of omelet onto it for his brother and sets the plate down beside his own. He adds a baguette and sits back down. A few more anxious beats pass. Will Primo resume the clash from last night? Has the brawl itself—and the angry words spoken—shattered the bond between them forever?

Primo grabs a chair and carries it over to the butcher block. He sits beside his brother. Primo takes a first bite of the omelet. Secondo takes a bite of his own.

Tentatively, Secondo puts an arm around his brother’s shoulder. He pats Primo’s back. Another bite from Primo. Primo puts his arm around Secondo. No word has been spoken. The brothers continue eating their omelets, side by side.

Sometimes an Epiphanal Moment simply acknowledges What Is Really Important. This acknowledgment doesn’t solve anything in the material world. For Primo and Secondo, their business prospects continue to be beyond bleak. Neither one has any idea how to go forward professionally. But they have both recognized What Really Counts.

They have moved from the ego to the Self.

Here’s the scene on YouTube.

And the fight on the beach.

Big Night was directed by Stanley Tucci and Campbell Scott from a script by Tucci and Joseph Tropiano. It’s a good one!

The post Ego and Self in the All is Lost Moment first appeared on Steven Pressfield.March 1, 2023

Einstein and the Epiphanal Moment

Albert Einstein famously said, “No problem can be solved from the same level of consciousness that created it.”

Now I can’t claim to ken the mind of Einstein (as my eight-grade Earth Science teacher, Mrs. Wright, used to tell me, “You ain’t no Einstein!”), but I think Mr. E. has hit on the exact formula for the Epiphanal Moment.

In the All Is Lost Moment, the mind must upshift. It must ascend from a lower dimension to a higher. That’s the only way it can “solve” the All Is Lost Moment.

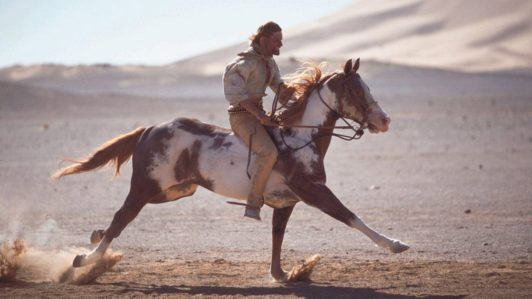

Viggo Mortensen as Frank T. Hopkins in “Hidalgo”

Viggo Mortensen as Frank T. Hopkins in “Hidalgo”This can mean (sometimes) simple acceptance. Isn’t that, in the end, what Elisabeth Kubler-Ross described as the final (and most highly-evolved) stage of grief? In other words, the last beat of wisdom before dying?

But back to Einstein.

Let’s consider the 2004 movie Hidalgo. Have you seen it? It stars Viggo Mortensen, Omar Sharif, and several American Paint horses as the real-life mustang, Hidalgo. The film (screenplay by John Fusco) is the more-or-less true story of Frank Hopkins, the famous long-distance endurance racer, and his participation in the 3000-mile “Ocean of Fire” race across the Najd desert in 1891 against purebred Arabian and other beyond-price equine champions.

Bear with me as I go into this. It takes a few paragraphs to tell the story.

Frank is half-white, half-Native American. When we first meet him, he’s drinking heavily; we see he’s troubled. In an early flashback, we learn that Frank, as a horseback courier for the US Army, was the one who delivered the orders to the Seventh Cavalry, authorizing the massacre of Lakota Sioux at Wounded Knee. Frank didn’t know what was in the pouch, he was just delivering the orders. But the catastrophe (his mother, we learn later, was Lakota Sioux) has haunted him ever since.

In another early scene, Frank’s friend and mentor, Chief Eagle Horn (Floyd Red Crow Westerman), addresses him by the name “Far Rider.” But he, Eagle Horn, immediately qualifies this.

EAGLE HORN

I call you Far Rider, not for your long-distance racing, but because you ride ‘far from yourself.’

Frank signs up for the race across Arabia. His horse, as I said, is the unbeaten mustang Hidalgo, whom Frank loves more than life itself. The All is Lost Moment comes after three thousand miles and untold hazards and horrors across the Iraq and Arabian deserts. Hidalgo, exhausted from wounds and dehydration, collapses on the sand. He can’t go any farther. Frank Hopkins is near the end himself. With obvious agony, Frank unholsters his six-shooter, cocks it, and aims it point-blank at Hidalgo’s head, ready to put the suffering beast out of its misery.

This is the All Is Lost Moment.

Viggo Mortensen wound up buying one of the American Paint horses who played his pony “Hidalgo.” The film’s writer, John Fusco, bought another.

Viggo Mortensen wound up buying one of the American Paint horses who played his pony “Hidalgo.” The film’s writer, John Fusco, bought another.Now comes the Epiphanal Moment.

Frank, apparently hallucinating from the heat and the ordeal of the race, hears an eerie sound—like the ceremonial beating of drums. He hears voices. Are they singing? Frank peers out into the desert mirage, seeking the source of this mysterious phenomenon. There, shimmering above the sand about fifty feet away, stand three figures. The figures are clearly Native American. They say nothing to Frank. They come no closer. Are they Ancestors? Spirit guides?

We see from Frank’s expression that he interprets their appearance at this moment as a blessing. The figures have come from who-knows-where to tell him by their presence that he is not alone, that other Forces are witnessing his ordeal and are supporting him. They seem to tell him that his essence is Native American. This is his tribe. He is one of them. He is theirs and they are his.

The figures fade into the shimmering mirage. Frank still holds his cocked .45. But suddenly Hidalgo stirs. The great mustang gets to his feet. He’s alive! He can still race! Frank mounts Hidalgo and they gallop off, chasing their rivals toward the finish line.

My interpretation of this Epiphanal Moment is that, following Einstein’s idea above, the problem (Hidalgo’s near-death, Frank’s deep estrangement from himself) cannot be solved by any action or concept on the material plane. The answer must come from someplace higher—the plane of the spirit.

Did Frank hallucinate the three figures? Maybe. Probably. But they arose, nonetheless, from the core of his being, from his spirit or soul. They forgave him for his unwitting role in the massacre at Wounded Knee and they set him blameless for his drinking. They re-unite—or unite for the first time—Frank’s lost self and his true place of belonging.

I won’t spoil the movie for you by revealing the ultimate ending. Suffice it to say it is in perfect alignment with Frank’s new-found sense of himself.

The Epiphanal Moment has solved the All Is Lost Moment by addressing it from a higher plane of consciousness.

More examples (and a deeper examination of this) in the coming weeks.

The post Einstein and the Epiphanal Moment first appeared on Steven Pressfield.