Geoff Nelder's Blog, page 12

November 18, 2016

New #scifi story THE CHAOS OF MOKII

THE CHAOS OF MOKII

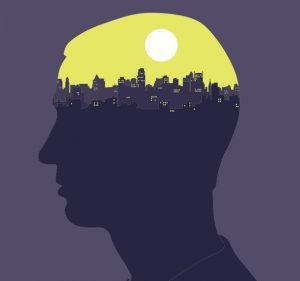

Imagine a city which exists only in the minds of its inhabitants. There’s everything you’d expect in a real city including fun and trouble. Olga, has to get past the bouncer then in Mokii she finds an intruder. He is trying to usurp the virtual city because there is financial reward from the advertising revenue beamed into the visitors’ minds. Can she thwart him?

New science fiction book release TODAY!

created as an ebook by Solstice Publishing read for only 99c The Chaos of Mokii

ebook at http://mybook.to/ChaosOM

Acknowledgments

The idea for this city that exists only in the consciousness of a group of people came to me after reading The Quantum Thief by Hannu Rajaniemi (2010). There are similar though not identical concepts there.

Further, my short story writing group, Orbiter #2 of the BSFA are instrumental in obliging me to submit this story to Solstice Publishing.

Thanks go to Olga Guseva of Moscow, Russia, who always supports my writing and after whom the main character in The Chaos of Mokii is named and to Tracy Guzzardo at Solstice for her editorial input.

No matter which country you are in this link will send you to the correct Amazon

Solstice and I tried various images for the cover art. We opted for one of Olga and a kind of electronic halo indicating she is in Mokii. Here are others that convey an aspect of the story.

The post New #scifi story THE CHAOS OF MOKII appeared first on Geoff Nelder - Science Fiction Writer.

November 16, 2016

The Codex by Helen McCabe

The Codex by Helen McCabe

The finale in the Piper Trilogy

Volume one is Piper (2008), Volume two is The Piercing (2014) – both excellent novels.

The Codex ISBN: 978-1-84583-923-9

Published by Telos

Kindle and Paperback

Paperback £12.99 UK Amazon link https://www.amazon.co.uk/Codex-3-Piper-Trilogy/

Link to the publisher’s site on the Piper Trilogy http://www.telos.co.uk/product/the-codex-the-piper-trilogy-3/

Ever since I saw the quaint, historical town of Hamlein from atop the shoulders of my father and chortled in delight at the re-enactment of the Pied Piper with his flute, luring the town’s children away, I’ve been absorbed by the genre. Of course, as a toddler I didn’t know it wasn’t real. Yet, that notion returns to bite me in the bum with Helen McCabe’s Piper trilogy. Why? Because The Codex didn’t stop in the Middle Ages. The piper is transformed and with us today!

The eponymous object, The Codex, refers to an ancient alternative Bible compiled by the dark side around 800 AD. Evil leaks from this tome and part of the mission by Pip is to seek the whole of the Codex and render it harmless. Forces are out to stop him and manifest themselves in unknown ways. This is a quest and in a kind of recursive, self-referencing way. I yearn to write a successful recursive story and find them as rare as black daisies. Note that the Codex has recursive elements. For instance it is the third volume of a trilogy. The protagonist is a writer needing to promote his third book of a trilogy, which in itself is a kind of Codex. It’s as if the readers are invited to be involved in drawing out the hidden elements of horror and evil not just written as writhing inside this novel.

As usual McCabe is a mistress of the artful word although I’m uncertain whether the Codex itself has its finger on her pen as for example: “ …a headache…skinny string reediness that crept through his skull and stuck like a hapless insect in his memory web.” The author is enviably skilled in oblique dialogue – I already refer my editing clients to chunks of her Piper stories for these writing masterclass elements.

Interesting left-field logic is used throughout such as should a virgin avoid the beast’s attention by giving herself to a willing lad and so change her sexual status?

In Codex we have medieval hardcore horror meeting the 21st Century where “secrets breed lies”.

Nelder News

One of my favourite short stories is CLOCKWORK. It’s a historical fantasy in which I’ve cheekily grabbed a day out of the life of Sir Francis Bacon in 1617 and made him and his dog experience an Earth-saving moment he had to pass on down the ages. A link to it is here (to buy but cheaper than a MacDonald’s fast meal and lasts much longer.)

One of my favourite short stories is CLOCKWORK. It’s a historical fantasy in which I’ve cheekily grabbed a day out of the life of Sir Francis Bacon in 1617 and made him and his dog experience an Earth-saving moment he had to pass on down the ages. A link to it is here (to buy but cheaper than a MacDonald’s fast meal and lasts much longer.)

http://www.fictionmagazines.com/shop/realm-issues/new-realm-vol-04-no-12/

Links to buy ARIA and other of my books are on my Amazon author page

Geoff’s UK Amazon author page

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Geoff-Nelder/e/B002BMB2XY

And for US readers http://www.amazon.com/Geoff-Nelder/e/B002BMB2XY

ARIA: Left Luggage is only 99p give or take a few pence at the moment on Kindle so grab it at smarturl.it/1fexhs

Or via other formats http://geoffnelder.com/project/left-luggage-arial-trilogy-part-1/

Geoff facebooks at http://www.facebook.com/AriaTrilogy and tweets at @geoffnelder

Later this week Solstice Publishing releases my Chaos of Mokii story as an ebook. More later.

Meanwhile I am writing a daft short story – Wits End in which a Welsh valley has experienced continuous rainfall since 1859. A meteorological phenomenon or a deliberate obfuscation by the military / aliens? I can’t wait to finish it and find out!

The post The Codex by Helen McCabe appeared first on Geoff Nelder - Science Fiction Writer.

November 14, 2016

Moon and Supermoon

Illusions, Coincidences and the Moon

Compiled by Geoff Nelder

Based on an article in Escape Velocity Issue #3 2008 by Geoff Nelder

Revised 2010 and 2016

A Supermoon – really?

In November 2016 the news media will excite us all over the opportunity to see our moon much larger than normal. In fact it will only be 14% larger but it will appear to be much larger when close to a low horizon. This article explores other aspects of the moon that has always fascinated me.

More than one?

Which moon I hear you ask. I could have filled a page or so about Cruithne, the 3-mile-wide (5-km) satellite, which takes 770 years to complete a horseshoe-shaped orbit around Earth. Some say it isn’t a proper moon, but let’s not go there. It will be up yet not easily visible around Earth for at least 5,000 years. I’ll focus this article on the moon we can see.

Dumbbell

I used to tease my students by saying that the Earth goes around the Moon. To my dismay I often found no reaction until I repeated it louder, and then they’d assumed I’d made a mistake. However, they accept the elliptical nature of the Moon’s orbit and when they are told that the focus is not in the dead centre of Earth but about 1700km beneath its surface, the unequal dumbbell dual orbit is appreciated.

A few facts

I could pack this magazine with dry facts such that the Moon is a quarter the diameter of Earth and 1/81 its mass. The average centre-to-centre distance from the Earth to the Moon is 384,403 km, which is about thirty times the diameter of the Earth. The Moon has a diameter of 3,474 km…. STOP! Anyone can scroll through data, let’s go for interesting.

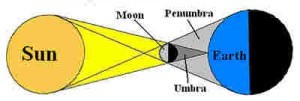

Now you see it…

Unlike ancient Man we now take eclipses for granted. Tabloid newspapers, not a wise old shaman, alert us these days. But would anyone have bothered were it not for the coincidence that the moon was orbiting just at the right distance for its disc to perfectly cover the Sun? Not that it always did so. The Moon used to be much closer, and so looked larger. It’s drifting away at a rate of around 4 cm per year. However, by the time Man kept records and made predictions, the eclipses were perfect. Why? The Sun’s diameter is 375 times that of the Moon. The Sun is 375 times the distance. Hence both have an angular diameter of around ½ degree as seen from your house. However, the gravitational tug is slowing the Earth’s spin. By the conservation of momentum and the Moon’s initial impetus, the Moon’s distance from Earth is increasing. Eventually, the Moon will not seem to cover the Sun giving us only annular eclipses. One day the Moon will stop drifting away – and return – whack. Or it will disintegrate at the Roche Limit, either way humans had better find somewhere else to live. On the other hand the Moon won’t reach us for another 50 billion years and we would have been engulfed by our sun doing its red giant trick long before that – maybe in 5 billion years. No sweat.

Optical illusion or mental delusion

Many people think the moon looks large at the horizon in contrast to its overhead (zenith) position. This is an illusion and in spite of overhearing people mentioning the magnifying lens of the atmosphere, the apparent size of the moon hardly changes. A simple proof would be to hold a small coin (you’d be surprised how small) to just cover the moon at zenith and again on the horizon. This is probably more a perception than an optical problem. Even back in 200 AD, Cleomedes suggested that the horizon moon looks larger because it is farther away, and our minds thus trick us. This was perceptive of him since, of course, the moon is about an Earth’s radius farther away when we view it on the horizon! Washburn in 1894 suggested that if we look at the horizon moon from between our legs (ie upside down) then the illusion vanishes. Perhaps we could do a straw poll on that one!

Part of the illusion maybe because the moon appears squashed and more red at the horizon – not a lens but a prism effect. Certainly, the scattering of the shorter wavelength blue light through the atmosphere allowing only the near-red longer wavelengths through gives us orange and red moons as it does for the sun.

Impact

There are half a million impact craters on the moon, mostly on the side facing away from the Earth for obvious reasons. What the nearside does have are Maria, which are large solidified seas of lava. These are likely to be the results of collisions with meteors or comets, but why should the nearside have them in preference to the farside? One theory is that the side of the Moon facing the Earth has a higher concentration of heat-producing elements (Shearer, 2006). This is supported by geochemical mapping via the satellite Lunar Prospector.

Origin

Hartmann & Davis in 1975 produced the most acceptable hypothesis that the Moon is the result of a giant impact from a Mars-sized planet colliding with Earth around 4.5 billion years ago. By then much of the iron on our planet had accumulated into the core, but only lighter mantle rock was blasted off and after forming a ring then aggregated into a sphere but with little iron. Unlike the other solar system objects the moon shares similar oxygen isotopes to that found in the Earth. So it is unlikely the Moon is a captured planetoid nor did it form by spinning off an early Earth or it would have more iron and computer models don’t support the dynamics.

Now we know the moon has significant quantities of water, it will be shortly be occupied even if only by researchers. Water is handy stuff and not just for drinking and washing. We only know there’s a few water tanks full in one crater for sure. Maybe water was donated by crashed comets or from ancient volcanoes – whichever, a lot more surveying is needed. They’ll be able to split the molecules to extract oxygen and hydrogen.

Would minds on Earth have had their imagination stretched more if we’d had a ring orbiting us instead of a moon? If so, would we all have been more intelligent and creative now? Intriguing isn’t it?

References

Hartmann, W. K. and D. R. Davis 1975 Icarus, 24, 505

Shearer, C.; et al. (2006). “Thermal and magmatic evolution of the Moon”. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 60: 365–518

Nelder News

One of my favourite short stories is CLOCKWORK. It’s a historical fantasy in which I’ve cheekily grabbed a day out of the life of Sir Francis Bacon in 1617 and made him and his dog experience an Earth-saving moment he had to pass on down the ages. A link to it is here (to buy but cheaper than a MacDonald’s fast meal and lasts much longer.)

http://www.fictionmagazines.com/shop/realm-issues/new-realm-vol-04-no-12/

Links to buy ARIA and other of my books are on my Amazon author page

Geoff’s UK Amazon author page

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Geoff-Nelder/e/B002BMB2XY

And for US readers http://www.amazon.com/Geoff-Nelder/e/B002BMB2XY

Geoff facebooks at http://www.facebook.com/AriaTrilogy and tweets at @geoffnelder

Later this week Solstice Publishing releases my Chaos of Mokii story as an ebook. More later.

The post Moon and Supermoon appeared first on Geoff Nelder - Science Fiction Writer.

October 12, 2016

New Realms has my #Clockwork story

Earlier this year on holiday in Albufeira, Portugal I read Kim Stanley Robinson’s historical fantasy novel, Galileo’s Dream. It’s my mother’s fault. Not only did she join me to the Children’s Science Fiction Book Club when I was four but she was an unquenchable reader (I’ve never liked the word avid – reminds me of hive insects) of historical novels. I didn’t so much enjoy the historical romances but the Lost Legions type stories that Henry Treece wrote fired the history cells as much as Asimov and Wyndham for the what if futures. I blogged a review here http://geoffnelder.com/galileos-dream-a-review/

While reading Galileo’s Dream I found Robinson’s style a bit slow at times but that kind of suits the historical context and the witticisms are marvellous eg

To a servant, “Mazzoleni, I am stupid.”

“I don’t know, Maestro…where does that leave the rest of us?”

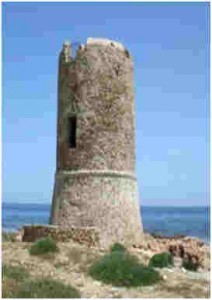

It grew on me that I would like to write historical fantasy and find I enjoy doing so. Hence my The Eidolon Redoubt in Twisted Tales IX: Wunderkind edited by J Richard Jacobs, published by DDP, in which is my EIDOLON REDOUBT story. It’s a historical fantasy based on a watch tower in Somerset during the Napoleonic wars. Not free but for those of you with a few pennies it can be yours here. http://hyperurl.co/fip106

It grew on me that I would like to write historical fantasy and find I enjoy doing so. Hence my The Eidolon Redoubt in Twisted Tales IX: Wunderkind edited by J Richard Jacobs, published by DDP, in which is my EIDOLON REDOUBT story. It’s a historical fantasy based on a watch tower in Somerset during the Napoleonic wars. Not free but for those of you with a few pennies it can be yours here. http://hyperurl.co/fip106

I am drawn to the Jacobean period when Newton, Hooke, Locke, Napier and how their women struggled to fight their subjugation. Clockwork is also inspired by a short black and white film, A Field in England (2013) written by Amy Jump, Directed by Ben Wheatley. In it a largely unexplained scene triggered my imagination. A rope is pulled as if the essence of the world will only be saved by such an action. The film is surreal, a wonderful peek into those mad English Civil War times of the 1640s and fuelled by Nature – especially magic mushrooms. Here’s the director talking about it https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bgwnlM4qpEU

The notion of a rope pulling at a capstan hidden from the world yet the planet needs it to be pulled forms the theme of Clockwork.

Alt History magazine rejected saying without elaboration that it didn’t fit. That annoyed me because I’d read their back issues and wrote Clockwork to fit. Nevertheless, Douglas W Lance at New Realms loved it and so it made it into New Realms magazine today. It tells the tale of a fictional day in the life of the real scientist Sir Francis Bacon. In my story he finds a rope and a message in an English wood – he has to pull the darn rope, doesn’t he?…

Click on the link if you’d like to read my tale and others for the price of a fast food meal, but lasting much longer.

http://www.fictionmagazines.com/shop/realm-issues/new-realm-vol-04-no-12/

Other Nelder News

I watched the film of book The Girl With All The Gifts by Mike Carey (2014) film is directed by Colm McCarthy (2016). It’s necessary to cut a lot of scenes to fit a 3-day read into a less-than-two hour film and it does feel rushed compared to the book. Disappointed that Melanie is black even though that’s a logical consequence of her name (from melanin) and that the hungries weren’t chased by bulldozers driven to action by outlaw ‘junkers’. In face the junkers don’t exist in the film. If you’ve not read the book, the film is good, if you’ve only seen the film, I’d advise to read the book – it will fill the gaps and enrich the experience.

Links to buy ARIA and other of my books are on my Amazon author page

Geoff’s UK Amazon author page

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Geoff-Nelder/e/B002BMB2XY

And for US readers http://www.amazon.com/Geoff-Nelder/e/B002BMB2XY

Geoff facebooks at http://www.facebook.com/AriaTrilogy and tweets at @geoffnelder

The post New Realms has my #Clockwork story appeared first on Geoff Nelder - Science Fiction Writer.

September 28, 2016

XAGHRA’S REVENGE to be published!

An outline of a historical fantasy.

XAGHRA’S REVENGE

I’m delighted to report that my latest novel, Xaghra’s Revenge, is to be published in 2017 by the publishers of the ARIA Trilogy, LL-Publications.

So, what is it? Overall, it is a historical fantasy within which are contemporary political scenes such as in present-day Libya, horror, humour and a titanic and epic religious struggle. We have pirates, slavery, a harem, revenge and retribution.

Fact:

In 1551 the Turkish buccaneer, Rais Dragut, sailed a pirate fleet to Gozo, abducted the population of 5000 and sailed them to North Africa.

The abducted were kept on the ships while Dragut won a siege against the Knights of St John at Tripoli. The surviving abducted were taken and sold into slavery at Constantinople, Tripoli and Tarhuna, Libya.

Some of the abducted had relatives on Malta sufficiently rich to buy them back, but most lost contact with their families.

Descendents of the original abductees live today in the Libyan town of Tarhuna.

One of the world’s most ancient buildings is on Gozo (Ggantija ‘temple’ at Xaghra, c. 3600-2500 BC) predates Stonehenge and the pyramids).

Fiction:

Both the spirits of the Gozitan abducted and of those Ottoman sailors and prisoners of war seek revenge but the time was never right. Finally, a man and woman, descended from key people involved in the 1551 travesty are thrown together in Lyon, France. The spirit of Gozo manipulates their relationship but the Ottoman spirit has other ideas.

The aim of the Ottoman spirit is to change the current historical timeline so that Suleiman wins the Siege of Malta in 1565 so that Christianity is beaten and dwindles.

Development of the novel

In Valetta, the Capital of Malta is a library dedicated to its history. I spent so many hours in that Melitensia library that it’s now built into the novel! Many trips as a researching tourist with my wife, and making friends with Maltese writers such as John Bonello and individual important locals such as Jimmy Farrugia and his wife, as well as British writers living on Gozo, helped me build up a feel for the country. I found ‘hidden’ tunnels and caves, and I always hug the world’s oldest building.

A few photographs:

Xaghra Ggantija temples. Over 6000 years old. Mostly buried and overgrown from Bronze age to 1827

1500s house in Xaghra

. Rabat the old name for Gozo’s main town, Victoria built entirely of limestone

© all images taken by Geoff Nelder 2005 — they may be copied with my blessing as long as credit is given

Pre-publication Review by novelist Gladys Hobson

XAGHRA’S REVENGE

A magic realism / historical fantasy by Geoff Nelder

Mid 16th Century Gozo, where the world’s most ancient building — the Gigantia temple at Xaghra — dwells in ruins, is the scene for the most outrageous episode in the history of Turkish buccaneering. Other than a few useless wrinklies, the entire population of Gozo, 5,000 men, women and children were carried off and kept onboard while Rais Dragut won a siege against the Knights of St John at Tripoli. The survivors were sold into slavery.

Nelder, in his unique style, uses this historical fact, and vivid magical Mediterranean settings, to weave his compelling contemporary fantasy, drawing the past into the present with mind-boggling paranormal happenings, his characters’ extrasensory perceptions, downright horror and kinky humour. Magic and mystery? More than that!

Murder, rape and mayhem! The story’s dramatic beginning takes place in the mid 16th Century Gozo, the three dimensional cast includes a Christian couple (Stjepan and Lydia), their infant Peter, Turkish buccaneers and Barbary corsair Rais Dragut. And importantly — the finding of a piece of stone bearing the likeness of a local ancient goddess.

Then in a change of scene, we are thrust into more familiar territory of Europe in the 21sst Century. Somewhat fickle-lover Reece is thrown (literally) into a relationship with a feisty, gorgeous damsel with nut-brown hair. But who is doing the pushing and matchmaking? Is Reece the secret agent he claims to be, in spite of his bumbling? What is the mystery concerning the sexy, boutique owner, Zita? Both of the partners with ancient bloodlines of Mediterranean origins.

It is a mistake to think the obvious, Nelder is too clever for that. Intrigue, fantasy, sexual encounters create literary magic, and transport us back and forth through time, holding the reader’s attention until the final END.

A thoroughly enjoyable read.

Gladys Hobson

Author of:

When Phones Were Immobile and Lived in Red Boxes.Blazing Embers, When Angels Lie, Desire, Seduction By Design, Checkmate

John Bonello, an award-winning Maltese author:

John A. Bonello, Malta

“A gripping tale, masterfully written that keeps you wanting for more with every line you read.”

The awards he won are:

2011 – First prize in the National Book Award, prose for young adults with ‘L-Aħħar Ħolma’

2013 – First prize in the National Book Award, prose for young adults with ‘Is-Sitt Aħwa’

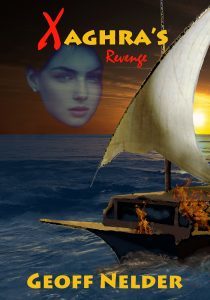

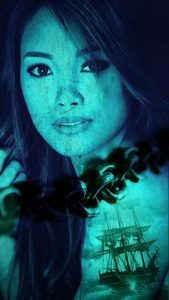

Cover Art

I have several ideas. Trouble is the whole book bulges with imagery. The world’s oldest building, pirate ships, Malta’s glorious mellow limestone fortifications, the final scene where a murmuration of good and evil spirits battle in the sky and Lidia, an abductee victim but also a fighter for freedom.

I’ll keep you up to date but here are some draft ideas. In order:

Lidia as captive – says it all especially with the revenge in the title

Pirate corsair ship with Lidia’s face rising above her abduction. Both  pictures are draft by John Keane

pictures are draft by John Keane

Another of Lidia this by Anita Kovacevic

A murmuration

A murmuration

A picture by the professional artist Daniel Dociu – already taken but I couldn’t afford his prices. If an amateur with reasonable prices for a poor author can do something similar than get in touch!

The post XAGHRA’S REVENGE to be published! appeared first on Geoff Nelder - Science Fiction Writer.

September 24, 2016

#Review The Man Who Lost The Sea

The Man Who Lost the Sea by Theodore Sturgeon

Theodore Sturgeon lived from 1918 to 1985. He was a prolific writer of speculative fiction with over 200 short stories and six novels, the most famous being More Than Human (1953), which I refer to in a blog post discussing Margaret Atwood’s assertion that she doesn’t write science fiction. See http://geoffnelder.com/is-it-science-fiction-2/

James Tiptree Jnr real name Alice B Sheldon (1915 – 1987) said in an interview that when writers’ block threatened she turned to Theodore Sturgeon’s The Man Who Lost The Sea for inspiration. I’d not read that short story and so printed it out to read on a plane to Athens last month.

Considering the story was written in 1959 I wanted to tell all the passengers on easyJet how much a contemporary style of writing lifted that story beyond most I read these days. It truly is inspiring and I can honestly say it is my number one favourite short story.

Because I am going to include the whole story in this blog, I’m not going to spoil the ending in these notes.

A helmeted man, stuck at night in sand or mud near an ocean, sees the stars including one shining object clearly orbiting the planet he’s on. It must be a satellite of some kind. In between hallucinations or dream / nightmare flashes he’s able to do some mental calculations and figures out what the satellite is and hence where he is. He realizes he will soon run out of air but instead of a morbid woe-is-me ending, he is absolutely delighted by his discovery. You’ll have to read it yourself. It won’t take long—less than a flight from Manchester to Athens.

Reading his short story has spurred me to find other works by Sturgeon. Tricky, because most are well out of print but a friend in the Chester Library SFF Book Group has given me a couple. Both are collections of shorts. One, E Pluribus Unicorn (1959), has an introduction by Geoff Conklin in which he says of his friend, “…a master of the weird, the supernatural, the horrible, the uncompromisingly fantastic…This slight and bearded satyr… is wilful, disobedient, lyrical, cruel, tender, taunting, haunting and (I suspect) a bit ‘tetched in the haid’. You don’t read these stories: they happen to you. When you meet some of their characters, you will wish you hadn’t—and that’s a warning. But once you’ve met them you’ll never forget them—and that’s a promise!”

I wish I had reviewers saying such things about my tales.

Before I leave him there is Sturgeon’s Law: “Ninety percent of science fiction is crud, but then, ninety percent of everything is crud.” No arguments there.

Originally published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, October 1959

The Man Who Lost the Sea by Theodore Sturgeon

Say you’re a kid, and one dark night you’re running along the cold sand with this helicopter in your hand, saying very fast witchy-witchy-witchy. You pass the sick man and he wants you to shove off with that thing. Maybe he thinks you’re too old to play with toys. So you squat next to him in the sand and tell him it isn’t a toy, it’s a model. You tell him look here, here’s something most people don’t know about helicopters. You take a blade of the rotor in your fingers and show him how it can move in the hub, up and down a little, back and forth a little, and twist a little, to change pitch. You start to tell him how this flexibility does away with the gyroscopic effect, but he won’t listen. He doesn’t want to think about flying, about helicopters, or about you, and he most especially does not want explanations about anything by anybody. Not now. Now, he wants to think about the sea. So you go away.

The sick man is buried in the cold sand with only his head and his left arm showing. He is dressed in a pressure suit and looks like a man from Mars. Built into his left sleeve is a combination time-piece and pressure gauge, the gauge with a luminous blue indicator which makes no sense, the clock hands luminous red. He can hear the pounding of surf and the soft swift pulse of his pumps. One time long ago when he was swimming he went too deep and stayed down too long and came up too fast, and when he came to it was like this: they said, “Don’t move, boy. You’ve got the bends. Don’t even try to move.” He had tried anyway. It hurt. So now, this time, he lies in the sand without moving, without trying.

His head isn’t working right. But he knows clearly that it isn’t working right, which is a strange thing that happens to people in shock sometimes. Say you were that kid, you could say how it was, because once you woke up lying in the gym office in high school and asked what had happened. They explained how you tried something on the parallel bars and fell on your head. You understood exactly, though you couldn’t remember falling. Then a minute later you asked again what had happened and they told you. You understood it. And a minute later . . . forty-one times they told you, and you understood. It was just that no matter how many times they pushed it into your head, it wouldn’t stick there; but all the while you knewthat your head would start working again in time. And in time it did. . . . Of course, if you were that kid, always explaining things to people and to yourself, you wouldn’t want to bother the sick man with it now.

Look what you’ve done already, making him send you away with that angry shrug of the mind (which, with the eyes, are the only things which will move just now). The motionless effort costs him a wave of nausea. He has felt seasick before but he has never been seasick, and the formula for that is to keep your eyes on the horizon and stay busy. Now! Then he’d better get busy—now; for there’s one place especially not to be seasick in, and that’s locked up in a pressure suit. Now!

So he busies himself as best he can, with the seascape, landscape, sky. He lies on high ground, his head propped on a vertical wall of black rock. There is another such outcrop before him, whip-topped with white sand and with smooth flat sand. Beyond and down is valley, salt-flat, estuary; he cannot yet be sure. He is sure of the line of footprints, which begin behind him, pass to his left, disappear in the outcrop shadows, and reappear beyond to vanish at last into the shadows of the valley.

Stretched across the sky is old mourning-cloth, with starlight burning holes in it, and between the holes the black is absolute—wintertime, mountaintop sky-black.

(Far off on the horizon within himself, he sees the swell and crest of approaching nausea; he counters with an undertow of weakness, which meets and rounds and settles the wave before it can break. Get busier. Now.)

Burst in on him, then, with the X-15 model. That’ll get him. Hey, how about this for a gimmick? Get too high for the thin air to give you any control, you have these little jets in the wingtips, see? and on the sides of the empennage: bank, roll, yaw, whatever, with squirts of compressed air.

But the sick man curls his sick lip: oh, git, kid, git, will you?—that has nothing to do with the sea. So you git.

Out and out the sick man forces his view, etching all he sees with a meticulous intensity, as if it might be his charge, one day, to duplicate all this. To his left is only starlit sea, windless. In front of him across the valley, rounded hills with dim white epaulettes of light. To his right, the jutting corner of the black wall against which his helmet rests. (He thinks the distant moundings of nausea becalmed, but he will not look yet.) So he scans the sky, black and bright, calling Sirius, calling Pleiades, Polaris, Ursa Minor, calling that . . . that . . . Why, it moves. Watch it: yes, it moves! It is a fleck of light, seeming to be wrinkled, fissured, rather like a chip of boiled cauliflower in the sky. (Of course, he knows better than to trust his own eyes just now.) But that movement . . .

As a child he had stood on cold sand in a frosty Cape Cod evening, watching Sputnik’s steady spark rise out of the haze (madly, dawning a little north of west); and after that he had sleeplessly wound special coils for his receiver, risked his life restringing high antennas, all for the brief capture of an unreadable tweetle-eep-tweetle in his earphones from Vanguard, Explorer, Lunik, Discoverer, Mercury. He knew them all (well, some people collect match-covers, stamps) and he knew especially that unmistakable steady sliding in the sky.

This moving fleck was a satellite, and in a moment, motionless, uninstrumented but for his chronometer and his part-brain, he will know which one. (He is grateful beyond expression—without that sliding chip of light, there were only those footprints, those wandering footprints, to tell a man he was not alone in the world.)

Say you were a kid, eager and challengeable and more than a little bright, you might in a day or so work out a way to measure the period of a satellite with nothing but a timepiece and a brain; you might eventually see that the shadow in the rocks ahead had been there from the first only because of the light from the rising satellite. Now if you check the time exactly at the moment when the shadow on the sand is equal to the height of the outcrop, and time it again when the light is at the zenith and the shadow gone, you will multiply this number of minutes by 8—think why, now: horizon to zenith is one-fourth of the orbit, give or take a little, and halfway up the sky is half that quarter—and you will then know this satellite’s period. You know all the periods—ninety minutes, two, two-and-a-half hours; with that and the appearance of this bird, you’ll find out which one it is.

But if you were that kid, eager or resourceful or whatever, you wouldn’t jabber about it to the sick man, for not only does he not want to be bothered with you, he’s thought of all that long since and is even now watching the shadows for that triangular split second of measurement. Now! His eyes drop to the face of his chronometer: 0400, near as makes no never mind.

He has minutes to wait now—ten? . . . thirty? . . . twenty-three?—while this baby moon eats up its slice of shadowpie; and that’s too bad, the waiting, for though the inner sea is calm there are currents below, shadows that shift and swim. Be busy. Be busy. He must not swim near that great invisible amoeba, whatever happens: its first cold pseudopod is even now reaching for the vitals.

Being a knowledgeable young fellow, not quite a kid any more, wanting to help the sick man too, you want to tell him everything you know about that cold-in-the-gut, that reaching invisible surrounding implacable amoeba. You know all about it—listen, you want to yell at him, don’t let that touch of cold bother you. Just know what it is, that’s all. Know what it is that is touching your gut. You want to tell him, listen:

Listen, this is how you met the monster and dissected it. Listen, you were skin-diving in the Grenadines, a hundred tropical shoal-water islands; you had a new blue snorkel mask, the kind with face-plate and breathing-tube all in one, and new blue flippers on your feet, and a new blue spear-gun—all this new because you’d only begun, you see; you were a beginner, aghast with pleasure at your easy intrusion into this underwater otherworld. You’d been out in a boat, you were coming back, you’d just reached the mouth of the little bay, you’d taken the notion to swim the rest of the way. You’d said as much to the boys and slipped into the warm silky water. You brought your gun.

Not far to go at all, but then beginners find wet distances deceiving. For the first five minutes or so it was only delightful, the sun hot on your back and the water so warm it seemed not to have any temperature at all and you were flying. With your face under the water, your mask was not so much attached as part of you, your wide blue flippers trod away yards, your gun rode all but weightless in your hand, the taut rubber sling making an occasional hum as your passage plucked it in the sunlit green. In your ears crooned the breathy monotone of the snorkel tube, and through the invisible disk of plate glass you saw wonders. The bay was shallow—ten, twelve feet or so—and sandy, with great growths of brain-, bone-, and fire-coral, intricate waving sea-fans, and fish—such fish! Scarlet and green and aching azure, gold and rose and slate-color studded with sparks of enamel-blue, pink and peach and silver. And that thing got into you, that . . . monster.

There were enemies in this otherworld: the sand-colored spotted sea-snake with his big ugly head and turned-down mouth, who would not retreat but lay watching the intruder pass; and the mottled moray with jaws like bolt-cutters; and somewhere around, certainly, the barracuda with his undershot face and teeth turned inward so that he must take away whatever he might strike. There were urchins—the plump white sea-egg with its thick fur of sharp quills and the black ones with the long slender spines that would break off in unwary flesh and fester there for weeks; and file-fish and stone-fish with their poisoned barbs and lethal meat; and the stingaree who could drive his spike through a leg bone. Yet these were not monsters, and could not matter to you, the invader churning along above them all. For you were above them in so many ways—armed, rational, comforted by the close shore (ahead the beach, the rocks on each side) and by the presence of the boat not too far behind. Yet you were . . . attacked.

At first it was uneasiness, not pressing, but pervasive, a contact quite as intimate as that of the sea; you were sheathed in it. And also there was the touch—the cold inward contact. Aware of it at last, you laughed: for Pete’s sake, what’s there to be scared of?

The monster, the amoeba.

You raised your head and looked back in air. The boat had edged in to the cliff at the right; someone was giving a last poke around for lobster. You waved at the boat; it was your gun you waved, and emerging from the water it gained its latent ounces so that you sank a bit, and as if you had no snorkel on, you tipped your head back to get a breath. But tipping your head back plunged the end of the tube under water; the valve closed; you drew in a hard lungful of nothing at all. You dropped your face under; up came the tube; you got your air, and along with it a bullet of seawater which struck you somewhere inside the throat. You coughed it out and floundered, sobbing as you sucked in air, inflating your chest until it hurt, and the air you got seemed no good, no good at all, a worthless devitalized inert gas.

You clenched your teeth and headed for the beach, kicking strongly and knowing it was the right thing to do; and then below and to the right you saw a great bulk mounding up out of the sand floor of the sea. You knew it was only the reef, rocks and coral and weed, but the sight of it made you scream; you didn’t care what you knew. You turned hard left to avoid it, fought by as if it would reach for you, and you couldn’t get air, couldn’t get air, for all the unobstructed hooting of your snorkel tube. You couldn’t bear the mask, suddenly, not for another second, so you shoved it upward clear of your mouth and rolled over, floating on your back and opening your mouth to the sky and breathing with a quacking noise.

It was then and there that the monster well and truly engulfed you, mantling you round and about within itself—formless, borderless, the illimitable amoeba. The beach, mere yards away, and the rocky arms of the bay, and the not-too-distant boat—these you could identify but no longer distinguish, for they were all one and the same thing . . . the thing called unreachable.

You fought that way for a time, on your back, dangling the gun under and behind you and straining to get enough warm sun-stained air into your chest. And in time some particles of sanity began to swirl in the roil of your mind, and to dissolve and tint it. The air pumping in and out of your square-grinned frightened mouth began to be meaningful at last, and the monster relaxed away from you.

You took stock, saw surf, beach, a leaning tree. You felt the new scend of your body as the rollers humped to become breakers. Only a dozen firm kicks brought you to where you could roll over and double up; your shin struck coral with a lovely agony and you stood in foam and waded ashore. You gained the wet sand, hard sand, and ultimately, with two more paces powered by bravado, you crossed high-water mark and lay in the dry sand, unable to move.

You lay in the sand, and before you were able to move or to think, you were able to feel a triumph—a triumph because you were alive and knew that much without thinking at all.

When you were able to think, your first thought was of the gun, and the first move you were able to make was to let go at last of the thing. You had nearly died because you had not let it go before; without it you would not have been burdened and you would not have panicked. You had (you began to understand) kept it because someone else would have had to retrieve it—easily enough—and you could not have stood the laughter. You had almost died because They might laugh at you.

This was the beginning of the dissection, analysis, study of the monster. It began then; it had never finished. Some of what you had learned from it was merely important; some of the rest—vital.

You had learned, for example, never to swim farther with a snorkel than you could swim back without one. You learned never to burden yourself with the unnecessary in an emergency: even a hand or a foot might be as expendable as a gun; pride was expendable, dignity was. You learned never to dive alone, even if They laugh at you, even if you have to shoot a fish yourself and say afterward “we” shot it. Most of all, you learned that fear has many fingers, and one of them—a simple one, made of too great a concentration of carbon dioxide in your blood, as from too-rapid breathing in and out of the same tube—is not really fear at all but feels like fear, and can turn into panic and kill you.

Listen, you want to say, listen, there isn’t anything wrong with such an experience or with all the study it leads to, because a man who can learn enough from it could become fit enough, cautious enough, foresighted, unafraid, modest, teachable enough to be chosen, to be qualified for. . . .

You lose the thought, or turn it away, because the sick man feels that cold touch deep inside, feels it right now, feels it beyond ignoring, above and beyond anything that you, with all your experience and certainty, could explain to him even if he would listen, which he won’t. Make him, then; tell him the cold touch is some simple explainable thing like anoxia, like gladness even: some triumph that he will be able to appreciate when his head is working right again.

Triumph? Here he’s alive after . . . whatever it is, and that doesn’t seem to be triumph enough, though it was in the Grenadines, and that other time, when he got the bends, saved his own life, saved two other lives. Now, somehow, it’s not the same: there seems to be a reason why just being alive afterward isn’t a triumph.

Why not triumph? Because not twelve, not twenty, not even thirty minutes is it taking the satellite to complete its eighth-of-an-orbit: fifty minutes are gone, and still there’s a slice of shadow yonder. It is this, this which is placing the cold finger upon his heart, and he doesn’t know why, he doesn’t know why, he will not know why; he is afraid he shall when his head is working again. . . .

Oh, where’s the kid? Where is any way to busy the mind, apply it to something, anything else but the watchhand which outruns the moon? Here, kid: come over here—what you got there?

If you were the kid, then you’d forgive everything and hunker down with your new model, not a toy, not a helicopter or a rocket-plane, but the big one, the one that looks like an overgrown cartridge. It’s so big, even as a model, that even an angry sick man wouldn’t call it a toy. A giant cartridge, but watch: the lower four-fifths is Alpha—all muscle—over a million pounds thrust. (Snap it off, throw it away.) Half the rest is Beta—all brains—it puts you on your way. (Snap it off, throw it away.) And now look at the polished fraction which is left. Touch a control somewhere and see—see? it has wings—wide triangular wings. This is Gamma, the one with wings, and on its back is a small sausage; it is a moth with a sausage on its back. The sausage (click! it comes free) is Delta. Delta is the last, the smallest: Delta is the way home.

What will they think of next? Quite a toy. Quite a toy. Beat it, kid. The satellite is almost overhead, the sliver of shadow going—going—almost gone and . . . gone.

Check: 0459. Fifty-nine minutes? give or take a few. Times eight . . . 472 . . . is, uh, 7 hours 52 minutes.

Seven hours fifty-two minutes? Why, there isn’t a satellite round earth with a period like that. In all the solar system there’s only . . .

The cold finger turns fierce, implacable.

The east is paling and the sick man turns to it, wanting the light, the sun, an end to questions whose answers couldn’t be looked upon. The sea stretches endlessly out to the growing light, and endlessly, somewhere out of sight, the surf roars. The paling east bleaches the sandy hilltops and throws the line of footprints into aching relief. That would be the buddy, the sick man knows, gone for help. He cannot at the moment recall who the buddy is, but in time he will, and meanwhile the footprints make him less alone.

The sun’s upper rim thrusts itself above the horizon with a flash of green, instantly gone. There is no dawn, just the green flash and then a clear white blast of unequivocal sunup. The sea could not be whiter, more still, if it were frozen and snow-blanketed. In the west, stars still blaze, and overhead the crinkled satellite is scarcely abashed by the growing light. A formless jumble in the valley below begins to resolve itself into a sort of tent-city, or installation of some kind, with tubelike and sail-like buildings. This would have meaning for the sick man if his head were working right. Soon, it would. Will. (Oh . . .)

The sea, out on the horizon just under the rising sun, is behaving strangely, for in that place where properly belongs a pool of unbearable brightness, there is instead a notch of brown. It is as if the white fire of the sun is drinking dry the sea—for look, look! the notch becomes a bow and the bow a crescent, racing ahead of the sunlight, white sea ahead of it and behind it a cocoa-dry stain spreading across and down toward where he watches.

Beside the finger of fear which lies on him, another finger places itself, and another, making ready for that clutch, that grip, that ultimate insane squeeze of panic. Yet beyond that again, past that squeeze when it comes, to be savored if the squeeze is only fear and not panic, lies triumph—triumph, and a glory. It is perhaps this which constitutes his whole battle: to fit himself, prepare himself to bear the utmost that fear could do, for if he can do that, there is a triumph on the other side. But . . . not yet. Please, not yet awhile.

Something flies (or flew, or will fly—he is a little confused on this point) toward him, from the far right where the stars still shine. It is not a bird and it is unlike any aircraft on earth, for the aerodynamics are wrong. Wings so wide and so fragile would be useless, would melt and tear away in any of earth’s atmosphere but the outer fringes. He sees then (because he prefers to see it so) that it is the kid’s model, or part of it, and for a toy it does very well indeed.

It is the part called Gamma, and it glides in, balancing, parallels the sand and holds away, holds away slowing, then, settles, all in slow motion, throwing up graceful sheet-fountains of fine sand from its skids. And it runs along the ground for an impossible distance, letting down its weight by the ounce and stingily the ounce, until look out until a skid look out fits itself into a bridged crevasse look out, look out! and still moving on, it settles down to the struts. Gamma then, tired, digs her wide left wingtip carefully into the racing sand, digs it in hard; and as the wing breaks off, Gamma slews, sidles, slides slowly, pointing her other triangular tentlike wing at the sky, and broadside crushes into the rocks at the valley’s end.

As she rolls smashing over, there breaks from her broad back the sausage, the little Delta, which somersaults away to break its back upon the rocks, and through the broken hull spill smashed shards of graphite from the moderator of her power-pile. Look out! Look out! and at the same instant from the finally checked mass of Gamma there explodes a doll, which slides and tumbles into the sand, into the rocks and smashed hot graphite from the wreck of Delta.

The sick man numbly watches this toy destroy itself: what will they think of next?—and with a gelid horror prays at the doll lying in the raging rubble of the atomic pile: don’t stay there, man—get away! get away! that’s hot, you know? But it seems like a night and a day and half another night before the doll staggers to its feet and, clumsy in its pressure-suit, runs away up the valleyside, climbs a sand-topped outcrop, slips, falls, lies under a slow cascade of cold ancient sand until, but for an arm and the helmet, it is buried.

The sun is high now, high enough to show the sea is not a sea, but brown plain with the frost burned off it, as now it burns away from the hills, diffusing in air and blurring the edges of the sun’s disk, so that in a very few minutes there is no sun at all, but only a glare in the east. Then the valley below loses its shadows, and, like an arrangement in a diorama, reveals the form and nature of the wreckage below: no tent city this, no installation, but the true real ruin of Gamma and the eviscerated hulk of Delta. (Alpha was the muscle, Beta the brain; Gamma was a bird, but Delta, Delta was the way home.)

And from it stretches the line of footprints, to and by the sick man, above to the bluff, and gone with the sandslide which had buried him there. Whose footprints?

He knows whose, whether or not he knows that he knows, or wants to or not. He knows what satellite has (give or take a bit) a period like that (want it exactly?—it’s 7.66 hours). He knows what world has such a night, and such a frosty glare by day. He knows these things as he knows how spilled radioactives will pour the crash and mutter of surf into a man’s earphones.

Say you were that kid: say, instead, at last, that you are the sick man, for they are the same; surely then you can understand why of all things, even while shattered, shocked, sick with radiation calculated (leaving) radiation computed (arriving) and radiation past all bearing (lying in the wreckage of Delta) you would want to think of the sea. For no farmer who fingers the soil with love and knowledge, no poet who sings of it, artist, contractor, engineer, even child bursting into tears at the inexpressible beauty of a field of daffodils—none of these is as intimate with Earth as those who live on, live with, breathe and drift in its seas. So of these things you must think; with these you must dwell until you are less sick and more ready to face the truth.

The truth, then, is that the satellite fading here is Phobos, that those footprints are your own, that there is no sea here, that you have crashed and are killed and will in a moment be dead. The cold hand ready to squeeze and still your heart is not anoxia or even fear, it is death. Now, if there is something more important than this, now is the time for it to show itself.

The sick man looks at the line of his own footprints, which testify that he is alone, and at the wreckage below, which states that there is no way back, and at the white east and the mottled west and the paling flecklike satellite above. Surf sounds in his ears. He hears his pumps. He hears what is left of his breathing. The cold clamps down and folds him round past measuring, past all limit.

Then he speaks, cries out: then with joy he takes his triumph at the other side of death, as one takes a great fish, as one completes a skilled and mighty task, rebalances at the end of some great daring leap; and as he used to say “we shot a fish” he uses no “I”:

“God,” he cries, dying on Mars, “God, we made it!”

Theodore Sturgeon 1918-1985

Nelder News

Links to buy ARIA and other of my books are on my Amazon author page

Geoff’s UK Amazon author page

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Geoff-Nelder/e/B002BMB2XY

And for US readers http://www.amazon.com/Geoff-Nelder/e/B002BMB2XY

Geoff facebooks at http://www.facebook.com/AriaTrilogy and tweets at @geoffnelder

The post #Review The Man Who Lost The Sea appeared first on Geoff Nelder - Science Fiction Writer.

September 18, 2016

#Review The Girl With All The Gifts

The Girl with all the Gifts by M. R. Carey (2014)

My Science Fiction book group discussed The Girl With All The Gifts by M Carey yesterday. Although we all had issues with gaping plot holes and cliched characters we ALL enjoyed it. That’s the first book we liked unanimously after reading and reviewing 120 books these last 10 + years!

It’s another Zombie but these can run really fast and I recall a workshop on fantasy writing in which it was hilariously argued that zombies can’t run, only shuffle. Hence these are called hungries, a good name because they are insatiably hungry. They’ve caught a plague-like virus in which a fungus replaces your neurons effectively replacing your brain with commands to eat to feed the fungus stages of development. This story has Melanie, a partial hungry as the main character making the novel a compelling, original read.

Accessible writing style with no challenging vocabulary except in the realm of neuroscience where some terms are necessarily fictional eg Ophiocordyceps. Also pseudo words used by Dr Caldwell to enhance her science persona eg p295 “…neotenuous form…the GABA-A receptor. The hyperpolarisation of the nerve cell…” Much of the biology is dubious. Weird stuff can happen in fiction, especially Science Fiction and Fantasy with the reader not needing a detailed explanation. Indeed when a zombie plague is explained (or attempts to) repeatedly and increasingly as with Dr Caldwell, the reader can become increasingly suspicious and the fictive dream becomes thin.

Having said that, I enjoyed this page turner and didn’t want it to end. I enjoyed the various main character points of view, especially that of Melanie (also appreciated her comment on her name – I’m not black so shouldn’t have been called Melanie. Yet the film of the book has her as black) as her high intelligence yet placid acceptance of her situation in the base, led her to understand more of what has happened to her. It is basically a post-apocalyptic action thriller but unusual in that humans as we know them, do not survive – except, possibly the teacher and Melanie’s crush, Helen Justineau, who (spoiler) after the final adult Ophiocordyceps spore are released effectively infecting all remaining humans including Junkers, wears a biohelmet.

Not sure I liked the denouement in that when Dr Caldwell made her breakthrough in her dying moments, she tells Melanie all but not the reader, who has to surmise it through the girl later, and might get it wrong. Presumably it was indeed the final ‘environmental trigger’ event that was needed to open the pods although that didn’t explain how the new form of the neural fungus / plague is different. In any case Jack Pine cones need heat to open (not all the time) because they thrive better in a cleared forest milieu eg after a fire. Good simile though. Nice phrase of Melanie’s in that ‘There’s no cure for the plague but in the end the plague becomes its own cure.’ I say that even though the science remains obscure in spite or because of Caldwell’s obfuscations and hypothesising.

Not sure I understand the time scale of the progeny element in the explanation. Humans contracting the plague initially, are brain dead with minutes or hours, their bodily functions continue under the spore control, and they become insatiably hungry in order for the spore to be ‘fed’. However, their children have partial immunity to the fungus eg Melanie in which its development is slowed and the child’s intellect functions normally. In which case, if the parents are brain dead in minutes how are their children conceived? We are given hints that the plague has mutated over the 20 years so maybe earlier forms were not as quick? However, Melanie and the other children appear to be around 5 to 15 years old so why were they only discovered recently?

Issues the book group had with the novel include the gaping holes in the plot. John reckoned that since hungries are attracted by noise and movement (as well as uninfected humans) then when Junkers (uninfected humans determined to survive but who want to attack the defended base that Melanie and her partial ‘hungries’ classmates are schooled but also cut up to see why they are different) drive hungries toward the base they should have turned to attack the bulldozers. Fair point.

I like the symmetry in the plot line where it starts and ends with a class lesson and it’s interesting, at least to me, that ‘schooldays’ was the prompt for Mike Carey to write this story as a short for an anthology.

Not keen on the title. The girl with all the gifts is catchy, a hook, but does Melanie really have all the gifts? She certainly possesses some handy attributes eg seeing very well at night, running fast, super-strong, and at the end, she is able to control the other children, possibly because her killing of the previous leader – a clan, pack thing? On the other hand, she can only eat meat so how does her body get things like vitamin C and fibre. She can’t feel pain and her wounds will fester, but then she will inherit the Earth so perhaps that’s the real gift.

In the afterword section of the book it is suggested that the novel Never Let Me Go (2005)by Kazuo Ishiguro possesses similar themes. These similarities include the school setting, children as main characters, and their bodies being cut up – in the case of NLMG for body parts as the kids are cloned from people who might need transplants. Many ethical issues here and some feature in Carey’s book too.

John also mentions Neal Asher’s book The Skinner (2002) in which an alien leech uses neuro replacement via a virus to symbiotically stay alive and so needs its host to stay alive too.

I enjoyed reading M Carey’s The Girl With All The Gifts and didn’t want it to end. There are unanswered questions but since humans continue to live but not as we know them, and the post-apocalyptic Britain, and Earth, is changed I don’t want to read a sequel. Nor really, a prequel thank you.

Nelder News I enjoyed a fabulous nine days in Greece. Most of it was on the archipelago of Methana at an artists and writers’ retreat, Limnisa run by a Dutch woman, Mariel and Englishman, Philip. Retreat members came and went with around eight or nine of us staying at Limnisa or the local village Agios Georgias. All women except for me! Margaret and Lillian met me at Athens. Margaret is an artist from the same sparsely populated island of Raasay off the Isle of Skye as writer, Lillian. I hired a mountain bike and charged up the slopes of extinct volcanoes in the mornings and wrote in cool, shady nooks at Limnisa in the afternoons. I was able to read The Girl With All the Gifts and write its review. I read papers on the science of creativity as research and used it to inform preparation for my talk to the U3A at Ruthin later this month on ‘Releasing the writer within me’. I finished the first draft of a fantasy story, Wandering Wood, in which a woman botanist is trapped by strange trees (looking like the wonderful eucalyptus at Limnisa).

I enjoyed a fabulous nine days in Greece. Most of it was on the archipelago of Methana at an artists and writers’ retreat, Limnisa run by a Dutch woman, Mariel and Englishman, Philip. Retreat members came and went with around eight or nine of us staying at Limnisa or the local village Agios Georgias. All women except for me! Margaret and Lillian met me at Athens. Margaret is an artist from the same sparsely populated island of Raasay off the Isle of Skye as writer, Lillian. I hired a mountain bike and charged up the slopes of extinct volcanoes in the mornings and wrote in cool, shady nooks at Limnisa in the afternoons. I was able to read The Girl With All the Gifts and write its review. I read papers on the science of creativity as research and used it to inform preparation for my talk to the U3A at Ruthin later this month on ‘Releasing the writer within me’. I finished the first draft of a fantasy story, Wandering Wood, in which a woman botanist is trapped by strange trees (looking like the wonderful eucalyptus at Limnisa).  Best experience is meeting new friends from the Netherlands, Italy, France and Britain but the very best – the feeling of bliss putting on a wet cycling shirt I’d just soaked in icy water in an upland Greek village then cycling in hot weather downhill back to Limnisa.

Best experience is meeting new friends from the Netherlands, Italy, France and Britain but the very best – the feeling of bliss putting on a wet cycling shirt I’d just soaked in icy water in an upland Greek village then cycling in hot weather downhill back to Limnisa.

In Athens I stayed overnight in the suburb of Sepolia in a cheap apartment. The owner was surprised I’d want to walk anywhere! However, it is only 9 minutes by Metro from the city centre and the Sepolia Metro station is right outside the apartment. In fact I walked all the way to the Acropolis from the apartment. How long did it take? I’m a writer and yearn to absorb the atmosphere of marvellous cities like Athens. I stop to watch playful children with their kittens, sample the many friendly bars and cafes en route, and do a little shopping. Oh, and gaze in awe at the railway train hooting and tooting its way across a busy street with NO crossing barriers. I would have missed much of that had I stayed in the centre. I’d say it would take a writer / rambler like me an hour to reach the Plaka but more fool you if you’re in a hurry. I hasten to add that the apartment is only three and half kilometres from the centre.

The apartment then is more like student digs but that’s fine for a few days. There are three double and two single beds, a big sofa that could be slept on, and air con in both main bedrooms. Well-equipped kitchen, bath – a luxury these days of travelling, and a washing machine. There’s no TV but hey, who needs TV when you can emerge from the kitchen or bedroom and gaze over the balcony, with its own table and chairs, and people watch. Honestly, stories were unfolded to me, better than on TV. Man-crisis over a puncture and his pals lifting the car up! Lovers ambling through the trees, Shoppers with excited kids coming and going to the toy /arts and craft shop and TWO good supermarkets I could see from the fourth floor. Wonderful. Sepolia is a vibrant suburban community and I wished I could have stayed longer. From the balcony you have a good view to the south west to Dafni and hills beyond and to the North.

Yes, improvements could be made to the décor but every minute I’d pinch myself and say, “You’re in ATHENS, home to Aristotle, Plato, the ‘gadfly of Athens, Socrates!

Publishing news

I have my Prime Meridian SF short in an anthology, Twisted Tales. The anthology was commissioned by the Readers Club Avenue Park and is available free from their website here. http://readersavenuepark.weebly.com/ or on Amazon at http://hyperurl.co/t7n22f

Also my Ubiquitous crime / SF story is in Crooked Tales at http://bit.ly/CrookSS

My ‘Accident waiting to happen is in this issue’ of New Realm Vol. 01 No. 07

It’s what could happen when you concentrate on a large book about to topple off a tall shelf in a library – fantasy.

Geoff’s UK Amazon author page

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Geoff-Nelder/e/B002BMB2XY

And for US readers http://www.amazon.com/Geoff-Nelder/e/B002BMB2XY

Geoff facebooks athttp://www.facebook.com/AriaTrilogy and tweets at @geoffnelder

http://nelderaria.wikia.com/wiki/NelderAria_Wiki

The post #Review The Girl With All The Gifts appeared first on Geoff Nelder - Science Fiction Writer.

August 22, 2016

Montygavus – plants & fiction

This is a Montygavus. Sounds as if it could be right, right? Not. My dad gave me a piece of root 30 years ago because I liked the flowering metre-high plant in his Cheltenham garden and I wanted it in my Chester hedge. Except it died, but not until a neighbour transplanted a bit and it grew next door where this photo comes from. Dad didn’t know what its proper name was but wanted to play a joke on his uppity neighbour, who knew the latin names of all his plants. Dad convinced him this flower is a Montygavus. His pal, Monty, gave it to him.

This is a Montygavus. Sounds as if it could be right, right? Not. My dad gave me a piece of root 30 years ago because I liked the flowering metre-high plant in his Cheltenham garden and I wanted it in my Chester hedge. Except it died, but not until a neighbour transplanted a bit and it grew next door where this photo comes from. Dad didn’t know what its proper name was but wanted to play a joke on his uppity neighbour, who knew the latin names of all his plants. Dad convinced him this flower is a Montygavus. His pal, Monty, gave it to him.

I used a Pl@ntNet app on my phone to identify it. The app said it was an Anemone hupehensis. The wonders of modern tech. Apparently it’s widespread in China and brought to England as recently as 1844 by botanist Robert Fortune. I’m still calling it a Montygavus.

On a similar theme (how plants entertain us, or possibly the other way around?) here’s a pretty yellow oxalis found everywhere on Gozo and most of Malta.

16. Yellow oxalis – all over Gozo BUT also called the English Weed cos an English woman brought it to Gozo in 1806!! Note the lizard.

Nomenclature: Oxalis pes-caprae with common names Bermuda buttercup(though it is neither a buttercup nor from Bermuda – haha) and African wood-sorrel. This bright yellow plant is the most common wild flower in the Maltese islands and has the local name of Haxixa Ingliza, which means English plant. This is because the plant was introduced to the islands by an Englishwoman around 1806. Just a dozen plants gave rise to the golden flowers everywhere in the Maltese spring months. It escaped from Malta to the rest of the Mediterranean.

I wanted to use the plant in my historical fantasy novel, Xaghra’s Revenge, but that is set in 1551 – 1565 so not possible! I can have ancient spirits and fantastic deeds but not the wrong plant.

Xaghra’s Revenge is still waiting for a smart publisher to snap it up.

Nelder News

I have my Prime Meridian SF short in an anthology. The anthology was commissioned by the Readers Club Avenue Park and is available free from their website here.

http://readersavenuepark.weebly.com/ or on Amazon at http://hyperurl.co/t7n22f

My ‘Accident waiting to happen is in this issue’ of New Realm Vol. 01 No. 07

My ‘Accident waiting to happen is in this issue’ of New Realm Vol. 01 No. 07

It’s what could happen when you concentrate on a large book about to topple off a tall shelf in a library – fantasy.

Geoff’s UK Amazon author page

http://www.amazon.co.uk/Geoff-Nelder/e/B002BMB2XY

And for US readers http://www.amazon.com/Geoff-Nelder/e/B002BMB2XY

Geoff facebooks athttp://www.facebook.com/AriaTrilogy and tweets at @geoffnelder

http://nelderaria.wikia.com/wiki/NelderAria_Wiki

The post Montygavus – plants & fiction appeared first on Geoff Nelder - Science Fiction Writer.

August 17, 2016

Life after Life

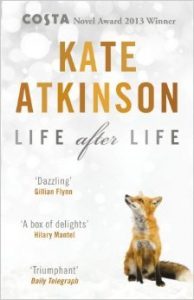

Life after Life – Kate Atkinson 2014

Review notes by Geoff Nelder

I read this novel as part of a trilogy of books on the theme of reliving lives – a topic we considered in literature in the Chester Library Science Fiction Book Group. I compare Kate Atkinson’s novel to the other two at the end of these notes.

Ursula Todd (Tod is death in German, something I found out from reading and enjoying Times Arrow by Martin Amis) has her life story retold many times from birth to when ‘darkness falls’. Each life she experiences is different: married / single / met Adolf Hitler (Adolf = Noble wolf and his fave song, allegedly is ‘who’s afraid of the big bad wolf’ / didn’t meet him / died as a child / died at 57)

It’s a kind of cross between Groundhog Day (1993 film starring Bill Murray based on a story by Danny Rubin) and Sliding Doors (1996 film starring Gwyneth Paltrow written by Peter Howitt)– more the latter because Ursula only has the impression of déjà vu of her past lives. It’s as if each life is a quasi memory of her existences in multi, parallel universes. No explanation of the phenomenon is in the novel, not that it matters as the reader then is free to conjure up their own.

Likes: description of Edwardian upper middle class life; description of experiencing being bombed in London in the blitz; her love of brother Teddy; literary style on the whole is elegant and inspirational; I liked it when Ursula found Renee in the bombed cellar when it was herself who’d died there in a previous (or parallel) life. Much liked the description of what Ursula as baby experiences – she sees a cricket ball passing over her pram; she’s left too long outside – forgotten?; beech leaves brown and brittle smothering her in autumn and yet beech leaves don’t generally fall then – they are pushed off in spring.; “…the train began to heave itself slowly out of the station”.

Ursula’s sliding down the wet roof and while doomed, grabs for her French knitting doll, reminds me of an unstable cliff in Whitby when I inadvisably climbed up to get a piece of shining black jet stone exposed in a recent storm. I needed to traverse but slipped, however, on my way down damaging knees and fingernails, I grabbed for the piece of jet and got it!

Dislikes: Sometimes the repetition is laborious in that I didn’t need to know at each birth what the doctor was eating or again why the midwife was stuck in snow. – Odd too though I appreciate the symmetrical plotting, is to have the midwife Point Of View right at the end instead of Ursula as the main character; German experiences on the Berg didn’t feel compelling; who was Nancy’s rapist and killer?

Concepts of time in the story. For Ursula, time is a jumble not a straight line as it is for Pamela and for most people.

Hugh, Ursula’s dad, told her that her future is all ahead of her but “Ursula harboured the feeling that some of her future was also behind her.”

It’s all a Dream? (stories that depend on dreams for their plot, especially in the denouement is considered a definite no-no by editors). There is a dreamlike quality to the whole book and near the end Ursula says, “It’s all like a dream,” but we don’t die in our dreams, do we? Reminded of Times Arrow by Martin Amis and Pincher Martin by William Golding where the whole story occurred in the dying moments of their lives.

Meaning of life theme. Ursula often refers to Nietzsche and perhaps it’s Atkinson saying that contrary to one of his philosophical points about your life is completely what you make it and kind of be happy all the time, the premise here is that life is beyond your assistance by and large.

I enjoyed this book far more than it niggled. I can recommend it.

Life after Life is similar in some ways to Replay by Ken Grimwood and

The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August by Claire North. Let’s see why:

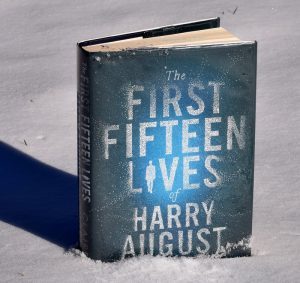

The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August by Claire North

Reviewed by Geoff Nelder

Paperback:448 pages

Publisher:Orbit; 2014 edition edition (28 Aug. 2014)

ISBN-13:978-0356502588

Harry is born in 1919 as the result of the rape of a maid, who dies in Harry’s birth in the station at Berwick-upon-Tweed. (I know that station because my dad lived in that town for a while.) He died in 1989 as the Berlin Wall fell and was born again in 1919 back in Berwick. He is one of several people who experience this phenomena – perhaps we all do in some way? – but few have perfect recall of their previous lives. Such people are mnemonics and have to wait until they are old enough (about 5 or 6) before they realize it. Many driven to suicide because they believe they are mad, many are protected and helped by members of the secret Chronus Club.

Harry is able to recall the results of races and successful businesses and so able to create wealth for himself along with false identities left in secret ‘dropboxes’.

He uses knowledge to protect future women from premature death by always killing their erstwhile murderer, Richard Lisle. He meets another mnemonic, Vincent Rankis, who has a goal of building a Quantum Mirror, which might bring about the end of the world as we know it. Other Chronus members are warned of this by future members sending messages backwards. The book’s hook is a clever, inspiring use of this by a young girl appearing at the deathbed of Harry and telling him to send a message to an aging man when he is reborn. “The end of the world” and that end is advancing. This is because Vincent is ‘breaking the rules’ by introducing future science and technology too early to industrialists. Vincent doesn’t realize that Harry is on to him even after making him forget the events in his life by short-circuiting his brain – doesn’t work with Harry. Vincent recruits a woman to help him eliminate kalachakra / ouroboran /: Chronus members – often before they are born. (spoiler – which is how he is finally eliminated – a disappointing ending considering it is just a repeat of what he did).

Although North uses the correct names for St Petersburg and Stalingrad for the time she uses Beijing even when it was called Peking. (although maybe the Chinese always called it Beijing?)

Interesting thought that everyone in Harry’s lives are reborn; they just don’t remember their past.

McGuffins ? (contrivance used as a plot motivator with little or no explanation – in this case the premise of reliving your life)

Much Tell and repetition though a fascinating concept used in several other books and films eg Groundhog Day(1993); Kate Atkinson’s Life after Life.(2014); Replay by Ken Grimwood (1986)

Brief note on Ken Grimwood’ Replay. Jeff dies of a heart attack in 1988 and awakes in 1963 as himself at aged 18. He recalls his previous existence and this is repeated often in spite of research to try and prevent his heart attack. In one of the 1974s he meets up with another replayer Pamela. At each replay they return later than the previous one but always die on the same date. Eventually this means the return time will postdate their death date and the book ends in some ambiguity as Jeff survives his last heart attack.

Nelder News

Limnisa

I’m off soon to the writing retreat Limnisa in Greece where I’ll be cycling, again, and outlining a sequel to Xaghra’s Revenge, writing up a short story called Wandering Wood (that’s a literal description and it’s not about Ents, Triffids or Mythago), and meeting up with pals from UK Authors forum.

Geoff’s UK Amazon author page http://www.amazon.co.uk/Geoff-Nelder/e/B002BMB2XY

And for US readers http://www.amazon.com/Geoff-Nelder/e/B002BMB2XY

Geoff facebooks at http://www.facebook.com/AriaTrilogy and tweets at @geoffnelder

http://nelderaria.wikia.com/wiki/NelderAria_Wiki

ARIA: Left Luggage, the first in this pre, during and post-apocalyptic novel about infectious amnesia is only 99p for the Kindle now at http://smarturl.it/1fexhs

The post Life after Life appeared first on Geoff Nelder - Science Fiction Writer.

July 10, 2016

The Lure of Bridges

The lure of bridges

Geoff Nelder

Whether it is a subject for art, films, books or poetry sooner or later we are drawn over or under a bridge. They are the subject of international competitions because they link territory and by metaphor, people with their cultural differences. (Ironbridge in Shrophshire from a bike ride)

As a climatologist I have been fascinated by and measured the effect of bridges on microclimates. In Chester, UK, the Grosvenor Bridge was the world’s largest single stone span for 30 years, when it was built in 1832. High above the waters of the River Dee the bridge separates airflow, mainly from the west so that it jets over the parapet threatening to blow this cyclist into the path of buses. Three miles downstream is the village of Eccleston where Chester’s coldest spot can always be found under a road bridge. The road dips to go under and so katabatic cold air pools there. The first survey of Chester’s urban heat island effect was undertaken by me leading a group of adult student across the city waving digital thermometers and the results published in 1985. Our coldest spot for that night and others was under the bridge in Eccleston often 5 degrees Celsius lower than in the city centre. The absence of sunlight reaching under the middle of the bridge also keeps it cool, along with the cool air flowing down into it. Another cold spot is under the Bridge of Sighs in Chester. The bridge used to be the last walk for prisoners trudging to the gallows on Northgate bridge nearby from the old prison, now Bluecoat Hospital School.

keeps it cool, along with the cool air flowing down into it. Another cold spot is under the Bridge of Sighs in Chester. The bridge used to be the last walk for prisoners trudging to the gallows on Northgate bridge nearby from the old prison, now Bluecoat Hospital School.

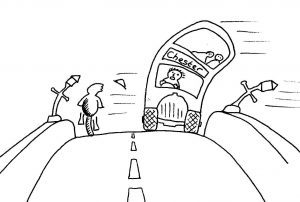

Illustration from Nelder, Geoff Chester’s Climate: Past, Present and Future (1985)

In science fiction literature there is hardly a more iconic bridge than in William Gibson’s Virtual Light. Here is my review.

Virtual Light by William Gibson

Penguin, 1993 ISBN 0-14-015772-7

First in the science fiction Bridge trilogy. Great though rather preposterous dystopian concept of a community living on the San Francisco Bridge.

Chevette Washington, a bike messenger, steals VR glasses at a party she crashes. Corrupt police, private security and other mysterious people are after her. One, Berry Rydell, rescues her from a security abduction even though he is part of it. He begins to fall for her though their relationship develops very late in the story without time to properly develop.

The bridge concept comes from a short story Gibson was commissioned to write by an architect group in SF. In the novel, one character is a rather shy (as opposed to all the others) Japanese sociologist, Yamazaki. He is in awe of the bridge and their people as shown in this superb setting piece: Note the poetic prose – repetition and echoing normally expunged by editors.