Jude Knight's Blog, page 75

January 3, 2020

The Greatest Killer

In some parts of England, people with communicable diseases such as smallpox were isolated in so called Pest Houses like this one in Findon.

“The smallpox was always present, filling the churchyards with corpses, tormenting with constant fears all whom it had stricken, leaving on those whose lives it spared the hideous traces of its power, turning the babe into a changeling at which the mother shuddered, and making the eyes and cheeks of the bighearted maiden objects of horror to the lover.”

T.B. Macaulay

For at least 3,000 and perhaps as much as 6,000 years, smallpox was one of the world’s deadliest diseases. In countries where it was endemic, it was a disease of childhood, killing up to 80% of children infected. A person fortunate to escape infection in childhood who then caught the virus as an adult, had a 30% chance of dying. Either way, those who survived the disease were left with lifelong scars but also with lifelong immunity, so they could neither catch the disease nor transmit it to others.

Transmission was from person to person, including from droplets in the air from sneezing, coughing, or even breathing. Worse, body fluids on things like clothing or bedding could carry live viruses.

In countries where the disease was new, with no such protective pool of survivors, the infection rate was horrific and the death rate catastrophic. For example, in the Americas, it’s estimated that smallpox, measles and influenza killed 90% of the native population. Children and adults were affected alike.

Even in Europe, though, smallpox changed the fate of nations. In Britain, it played a part in the downfall of the royal house of the Stuarts. Smallpox put Charles II out of action for several weeks during a crucial time in the Civil War, and killed his brother Henry. Had this Protestant prince been alive when James II’s Catholicism caused the rift with the people, history might have been quite different. All of the new king’s sons died young, one of smallpox. He was succeeded by his daughter Mary and his son-in-law and nephew William of Orange.

Mary died of smallpox towards the end of 1694. Thomas Macaulay described her death as follows:

That disease, over which science has since achieved a succession of glorious and beneficient victories, was then the most terrible of all the ministers of death. The havoc of the plague had been far more rapid; but the plague had visited our shores only once or twice within living memory; and the small pox was always present, filling the churchyards with corpses, tormenting with constant fears all whom it had not yet stricken, leaving on those whose lives it spared the hideous traces of its power, turning the babe into a changeling at which the mother shuddered, and making the eyes and cheeks of the betrothed maiden objects of horror to the lover. Towards the end of the year 1694, this pestilence was more than usually severe. At length the infection spread to the palace, and reached the young and blooming Queen. She received the intimation of her danger with true greatness of soul. She gave orders that every lady of her bedchamber, every maid of honour, nay, every menial servant, who had not had the small pox, should instantly leave Kensington House. She locked herself up during a short time in her closet, burned some papers, arranged others, and then calmly awaited her fate.

During two or three days there were many alternations of hope and fear. The physicians contradicted each other and themselves in a way which sufficiently indicates the state of medical science in that age. The disease was measles; it was scarlet fever; it was spotted fever; it was erysipelas. At one moment some symptoms, which in truth showed that the case was almost hopeless, were hailed as indications of returning health. At length all doubt was over. Radcliffe’s opinion proved to be right. It was plain that the Queen was sinking under small pox of the most malignant type.

All this time William remained night and day near her bedside. The little couch on which he slept when he was in camp was spread for him in the antechamber; but he scarcely lay down on it. The sight of his misery, the Dutch Envoy wrote, was enough to melt the hardest heart. Nothing seemed to be left of the man whose serene fortitude had been the wonder of old soldiers on the disastrous day of Landen, and of old sailors on that fearful night among the sheets of ice and banks of sand on the coast of Goree. The very domestics saw the tears running unchecked down that face, of which the stern composure had seldom been disturbed by any triumph or by any defeat. Several of the prelates were in attendance. The King drew Burnet aside, and gave way to an agony of grief. “There is no hope,” he cried. “I was the happiest man on earth; and I am the most miserable. She had no fault; none; you knew her well; but you could not know, nobody but myself could know, her goodness.” Tenison undertook to tell her that she was dying. He was afraid that such a communication, abruptly made, might agitate her violently, and began with much management. But she soon caught his meaning, and, with that gentle womanly courage which so often puts our bravery to shame, submitted herself to the will of God. She called for a small cabinet in which her most important papers were locked up, gave orders that, as soon as she was no more, it should be delivered to the King, and then dismissed worldly cares from her mind. She received the Eucharist, and repeated her part of the office with unimpaired memory and intelligence, though in a feeble voice. She observed that Tenison had been long standing at her bedside, and, with that sweet courtesy which was habitual to her, faltered out her commands that he would sit down, and repeated them till he obeyed. After she had received the sacrament she sank rapidly, and uttered only a few broken words. Twice she tried to take a last farewell of him whom she had loved so truly and entirely; but she was unable to speak. He had a succession of fits so alarming that his Privy Councillors, who were assembled in a neighbouring room, were apprehensive for his reason and his life. The Duke of Leeds, at the request of his colleagues, ventured to assume the friendly guardianship of which minds deranged by sorrow stand in need. A few minutes before the Queen expired, William was removed, almost insensible, from the sick room.

(In my book To Mend a Proper Lady , a girls school is caught up in a smallpox epidemic, causing my heroine Ruth Winderfield to flee with three girls for whom she is responsible plus two more she promises to deliver home on her way back to London. Of course, she becomes trapped at the home of the girls’ guardian, nursing them and others who fall ill.)

January 1, 2020

New Beginnings on WIP Wednesday

Happy new year, and welcome to my first WIP Wednesday for 2020. It seemed appropriate to post about beginnings. As always, I’d love you to share a start with me from your current WIP – the first paragraphs of a book, or of a chapter. Mine is the first scene from To Mend the Broken Hearted, the second book in The Children of the Mountain King. My goal is to finish this book by the end of the month, and publish it in May or June.

The crows rose in a flock over the tower on the borders of Ashbury land, a cacophony on wings. Val straightened and peered in that direction, shading his eyes to see if he could tell what had spooked them. It was unlikely to be a traveller on the lane that branched towards the manor from the road that passed the tower. After three years of repulsing visitors, the only people he ever saw were his tenant farmers and the few servants he had retained to keep the crumbling monstrosity he lived in marginally fit for human habitation.

He set the team moving again, the plough and seed drill combination creating a row of furrows behind him, but called a halt again when a bird shot up from almost under the horses’ hooves. Sure enough, a lapwing nest lay right in the path of the plough. Val carefully steered around it. He knew his concern for the pretty things set his tenants laughing behind his back, but they didn’t take up much room, and they’d hatch their chicks and be off to better cover.

One more evidence of his madness, the tenants thought, and in his worst moments he thought they were right, when thunder set him shaking or nightmares woke him screaming defiance or approaching anywhere close to that cursed tower froze him in his tracks.

The clouds that had threatened to disgorge all day finally sent a few stray drops his way, portents of more to come, but he had a bare two passes more to make to finish, and Barrow and his son were behind him with hoes, covering in the seed.

Another half hour would see the spring corn planted.

The gig from the inn went by beyond the hedge that bordered the lane. What was so important that it couldn’t wait until the housekeeper made her weekly trip to the nearest village? No matter. If he was needed, his manservant knew where to find him. He guided the team into the tight turn that would begin the second-to-last pass.

The rain thickened by the time he turned into the last row, and by half way down the field it’d soaked into the ground enough to make heavy going.

“Just a bit more,” he coaxed the horses, “just a bit more.”

He was half aware of the inn’s gig passing back along the lane in the direction of the village. Had it been making a delivery? His housekeeper had not mentioned any lack. His mind on the ploughing, he’d almost forgotten the gig by the time they at last reached the end.

“That’s it done, then, milord, “Barrow said, wiping his face which was as wet again a moment later.

Val agreed, habituation allowing him to hide his wince at being addressed with his brother’s title. Three years had not been enough to stop his reaction, but at least no one needed to know. “Get these boys home and give them a good feed,” he said, giving the lead horse a firm pat. “They’ve done well, and just in time.”

“That I will, milord. And you get yourself indoors, sir. Thankee,” Barrow said.

Did the man think Val too stupid or too far gone to go inside out of the rain? Well. No point in staying wet just to prove he was his own master. Val left Barrow to his son and horses, and set off to trudge back through the fields to the house, running the last few hundred yards through blinding hail.

Crick, his manservant, fussed over his towel and his bath and his dry clothes, and Val allowed it. This kind of weather was too much like Albuera for Crick’s demons, immersing him back into the confusion and the pain. Val told himself that he kept the old soldier out of compassion. During his worst moments, he feared his motivation was more of a sick desire to have someone around who was worse than him.

By the time Val was warm and dry again, the thunder had started. He sent Crick off to bed. There’d be no more sense out of the poor man tonight, nor much from Val, either. He refused the offer of dinner and shut himself up in his room so no one would see him whimpering like a child.

It was not until the following day, after the thunderstorm had passed, that he remembered the gig. Mrs Minnich, the housekeeper, remembered that it had delivered mail, and thought Crick had taken it, but what happened after that no one knew, least of all Crick. He had got roaring drunk and surfaced late in the day with a bad headache, a worse conscience, and no memory of the previous day at all.

The inn might know who it was from; even what it was about, since they’d sent someone out with it despite the weather. Val sent a note with Mrs Minnich on Friday, her regular day for shopping. She came back with the message that the gig had brought several letters, one of them marked urgent. It was from the school to which his sister-in-law had sent the girls before she absconded with the contents of the jewel safe shortly after she was made a widow, weeks before Val got word that he was now earl, and months before he got home.

The girls. He thought of them that way to avoid calling one of them his daughter, though the elder possibly was. The younger had been claimed by his brother, but not, in the end, by his brother’s wife. If the countess were to be believed, Val’s own lying wife was mother to the second child as well as the first. Perhaps even she had not known whether his brother had been father of both.

Whoever engendered them, the situation wasn’t the girls’ fault, but he still didn’t want to see either of them. He put the girls and the identity of their parents out of his head with the ease of long practice, along with any curiosity about the message. There were fields to plough, repairs to be made, and animal breeding to plan. If what the school wanted was important, no doubt they would write again.

December 29, 2019

More holiday reading — add your favourites (or your own) in the comments

My friends have also been publishing holiday books. I’ve put a few below. Please feel free to add more in the comments.

Caroline Warfield

Caroline Warfield’s Holiday Collection

Love and hope at Christmas and always.

The link takes you to more information and buy links for:

During four wartime holidays 1916-1919 a soldier and the widow whose love gives him hope cling to life and love. After the Great War will it be enough?

Lady Charlotte’s Christmas Vigil

Love is the best medicine and the sweetest things in life are worth the wait, especially at Christmastime in Venice for a stranded English Lady and a handsome Italian doctor.

Two people who don’t celebrate the same holiday as the other folk at a Regency house party, hold fast to their Judaic traditions. Can they also open their hearts and minds to love? It first appeared in Holly and Hopeful Hearts.

With Christmas coming, can the Earl of Chadbourn repair his sister’s damaged estate, and more damaged family? Dare he hope for love in the bargain?

This book is a prequel to both Children of Empire and the Dangerous Series. It first appeared in Mistletoe, Marriage, and Mayhem, and is always **FREE**

Sherry Ewing

Under the Mistletoe

A new suitor seeks her hand. An old flame holds her heart. Which one will she meet under the kissing bough? Under the Mistletoe

One Last Kiss

Sometimes it takes a miracle to find your heart’s desire…

E. Ayers

A Sister’s Christmas Gift

When tragedy strikes, career woman Brandy Devin is left to pick up the pieces of her sister’s life. What she finds changes her life forever. The bonds of family are strong, and love is even stronger.

Holiday reading in the spotlight

Are you looking for some holiday reading? I have some novellas and some collections for you. Click on the title to go to more information plus buy links.

Jude’s Christmas books

Paradise Regained

In discovering the mysteries of the East, James has built a new life. Will unveiling the secrets in his wife’s heart destroy it?

If Mistletoe Could Tell Tales

Wanted: love stories for a carriage-maker’s daughter, an admiral’s child, the unwanted wife of an earl, a nabob’s heiress, a duke’s cousin, and a fanatic’s niece

Wanted: love stories for a carriage-maker’s daughter, an admiral’s child, the unwanted wife of an earl, a nabob’s heiress, a duke’s cousin, and a fanatic’s niece

This 2017 collection has four novellas and two Christmas-themed short stories. Each of the novellas is also published separately, so you can buy individually if you have some of them and want the others without buying the collection.

A Suitable Husband (novella)

The cousin of a duke, however distant, can’t marry a chef from the slums, however talented. But dreams are free.

All that Glisters (story from Hand-Turned Tales)

Rose is unhappy in the household of her fanatical uncle. Thomas, a young merchant from Canada, offers a glimpse of another possible life. If she is brave enough to reach for it.

Candle’s Christmas Chair (novella)

Love blossoms between a viscount and a carriage maker’s daughter. Can they bridge the gap between them?

Gingerbread Bride (novella)

She runs away from unwanted complications and into disaster. Saving her has become a habit Rick doesn’t want to break.

Lord Calne’s Christmas Ruby (novella)

One wealthy merchant’s heiress who spurns fortune hunters. One impoverished earl with a twisted hand. Add one sweet aunt and one villainous rector, and stir.

Magnus and the Christmas Angel (story from Lost in the Tale)

Scarred by years in captivity, Magnus has fought English Society to be accepted as the true Earl of Fenchurch. Now he faces the hardest battle of all: to win the love of his wife.

Hearts in the Land of Ferns: Love Tales from New Zealand

Escape to beautiful New Zealand to enjoy tales of lovers who win against the odds.

A collection of Jude Knight’s New Zealand stories: two historical and three contemporary suspense.

All That Glisters: In gold rush New Zealand, they seek the treasure of a true heart (from Hand-Turned Tales)

Forged in Fire: Forged in Fire, their love will create them anew (from Never Too Late).

A Family Christmas: She’s hiding out. He’s coming home. And there’ll be storms for Christmas. (from Christmas Babies on Main Street)

Abbie’s Wish: Abbie’s Christmas wish draws three men to her mother. One of them is a monster (from Christmas Wishes on Main Street).

Beached: The truth will wash away her coastal paradise… (from Summer Romanceon Main Street ).

Christmas anthologies with other authors

Authors of Main Street

Contemporary romance. Most of the novellas are set in small town United States. My four (listed below) are set in New Zealand.

Abbie’s Wish in Christmas Wishes on Main Street

A Family Christmas in Christmas Babies on Main Street

Beached in Summer Romance on Main Street Volume 1

The Gingerbread Caper in Christmas Cookies on Main Street

Bluestocking Belles

Historical romance, mostly Regency or close.

The Bluestocking and the Barbarian in Holly and Hopeful Hearts

Forged in Fire in Never Too Late

Paradise Regained in Follow Your Star Home

December 27, 2019

The Seeds of Destruction

I was an omnivorous reader of history long before I started researching and writing historical novels. Indeed, it was that love for the stories of the past, and for what they can teach us in the present, that led to my current writing focus. Those who don’t learn from history, the old saying goes, are doomed to repeat it. In my books, I try to cast a spotlight on issues that are relevant today by showing them through the lens of a different place and time.

I write about a time when Napoleon had built an empire that had absorbed most of Europe as well as their colonial outposts, when the British empire was just beginning to flourish, when the nascent empire of the United States was less than half a century old as an independent political unit, when the empire of China was attempting to retain autonomy against the encroaching western newcomers. I try to write about real people facing eternal issues against genuine backgrounds.

The world has seen many empires rise and fall. Like the humans that build them, they’re all different and at the same time, all share common characteristics. They’re based on power and economic inequalities that allow some people to accumulate more wealth and leisure than others. This wealth and leisure permits a flowering of art, literature, and science that those in power celebrate as the result and evidence of their manifest worthiness. They exploit others, both inside and outside of their borders, to maintain their uneconomic lifestyle. They justify this exploitation by dehumanising and blaming those exploited. Over time, the gap between the poor and the wealthy grows until it become untenable. The Vandals pour over the borders. The colonies rebel. The sans-culottes storm the barricades.

(NOTE: I’m using the term empire to mean a sovereign political entity and its subsidiary nation states, including client states rather than those directly ruled. By this definition, I’m calling the hegemony of the United States an empire. Its boundaries shift and morph as nation states move in and out of client status. Empires also have a cultural impact far beyond their borders. As far as I can see, most empires have happily used their cultural influence for political and economic gain.)

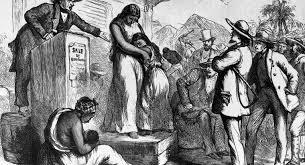

The unworthy poor

The unworthy poorEmpires, then, thrive on two factors–wealth accumulation through exploitation, and institutionalised discrimination against the exploited–and these two factors will eventually (within two or three hundred years, commonly) pull the empire to pieces. This is how predatory capitalism (defined as economics for the benefit of a few) is inevitably linked to racism or some other form of discrimination by stereotype.

Think of the British Empire: one of their management strategies was to demonise the Irish as poor, shiftless, and unworthy; the Chinese as crafty and near-demonic; the natives of the Indian sub-continent as lazy, stupid, and child-like. But never fear, oh inadequate people of the world. The British Empire was prepared shoulder ‘the white man’s burden’, and take over those places, stripping them of their resources and reducing said sub-human lifeforms to tenants in their own land (or worse).

I’m not picking particularly on the British. All empires do it. But I’m five generations from British ancestry, and those attitudes came down to me through my cultural ancestry. I had the good fortune to be born to a man who was a reverse racist; who collected people of all races to flaunt them as part of his rebellion against his family, and who insisted that all men (I choose the pronoun advisedly) were equal. I grew up with a much broader range of acquaintances than most white middle-class females of my age. Even so, I have spent a lifetime shedding preconceptions that I picked up from my elders and from the books made available to me.

To take just one example, my people were colonists. It was to their advantage to believe that they were on the side of the angels in New Zealand’s Land Wars. My elders were certain that Maori deserved to be on the bottom rung of our society because they were poorly educated and unsophisticated. It took more than a 100 years for New Zealand as a political entity to acknowledge that the government and the colonists were the aggressors in the Land Wars, and that repeated racism at every level of society, including in education and health, had maximised the impact of the theft of land by blocking any opportunity to succeed except by becoming a pseudo white person. (This is another standard strategy. Allow a few carefully selected individuals to fight their way into white positions and then blame everyone else for not doing so.

The Waitangi Tribunal provided a venue for hearing historical injustices. For all its faults, it has performed sterling service. Nearly 50 years on, we are still working our way towards reconciling the two views of history; that of the oppressors and that of the oppressed; but we’re trying.

Ancestral guilt

Ancestral guiltI’m inclined to think that guilt underpins our reluctance to believe in the ills of the past, or to deny their impact on the present. I’m not guilty of the casual racism of my ancestors and successive governments that ruled before I was born. I can’t take responsibility for things I can’t change. I am guilty of actions of my own that display unconscious bias. I am guilty if I support others in their bias. I can do something about those, so they are my responsibility.

Is this the reason why discrimination and racism are often strong in those cultures whose ancestors practiced the worst forms of chattel slavery? Ancestral guilt? The link between predatory capitalism and slavery is obvious. History tells us to expect slavery to be justified as being economically necessary and, in any case, for the good of the slaves. Justifying the last means regarding the slaves other and less; claiming that they are less than human, less than adult, dangerous to ‘normal’ people, morally defective, and so on and so on. The greater the guilt, the stronger the justifications that come rippling down through the centuries into the hearts and minds of descendants.

(Ironically, in both the United States and South Africa, DNA tests indicate that many who consider themselves both white and superior have unrecognised slave ancestors. But that’s another story.)

Where to from here?

Anger is growing, and so is fear. Is it too late to learn from history? We’re well into the decline. Is the fall inevitable? What do you think?

November 17, 2019

Absence makes the heart grow fonder

Is it ‘absence makes the heart grow fonder’? Or ‘out of sight, out of mind’?

You may have noticed I haven’t been around much. We’re selling our house and buying a new one, and my life is teetering on the edge of out of control. I’ve been proofing the Bluestocking Belles’ next anthology, Fire & Frost so we can get the ARC out. Add to that, I’ve other books to finish, grandchildren to cherish, and a day job.

Furthermore, we’re off on a road trip (organised months ago) a week today, so things are unlikely to improve for a while.

Received wisdom in the writer community is that we need to be constantly engaged on social media to keep people thinking about us, and buying the books we’ve written so we can afford to pay our bills for the books we want to write. If that’s true, I’m in trouble!

However, I won’t disappear entirely. I’m still promoting the Bluestocking Belles’ next anthology, Fire & Frost. I’ve written a short story for my newsletter, and will get that out before I go away. I’m about to put up the publication date for my novel The Darkness Within. (I’ll do a preorder on Smashwords which will feed back to the retailers it serves, but leave Amazon till I’m confident, because their punishment for getting it wrong is a year without preorder, and my life could spiral completely out of control at any moment.)

I also need to decide whether I’m going to publish something on 15 December. I’ve done so every year since Candle’s Christmas Chair came out in 2014, and I hate to miss a year. Options are a version of Chasing the Tale, my collection of newsletter subscriber short stories, and Paradise Regained, the prequel to the series I’m publishing next year, Children of the Mountain King. Let me know what you think!

Meanwhile, here’s an excerpt from the next newsletter subscriber story, which may (or may not) be called The Delinquency of Lord Clairmont. My heroine has waited years for her husband to return to England. When she learns from the gossip columns that he has done so, but is remaining in the south instead of coming home, she decides to retrieve him.

She would not apologise for making sure he came home to lands and investments that were more profitable and in better heart than when she took them over. Surely, even the most selfish of men must see that she had a vested interest in securing the future of her children.

Which brought Seffie to the reason why she, Anna, and the servants were about to descend from their coach at a manor owned by one of Clairmont’s dissolute friends. Children. She would be twenty-four in a few days, and she was not waiting another twelve years for her errant husband to at least make the attempt to get her with child. Not another year, nor a month.

Given what she’d heard about the nature of the parties held in this rather pleasant-looking country manor house, Clairmont may have one or more other entertainments already at hand, but Seffie was prepared to do whatever she needed to oust them and take their place. Surely a man whose name had been linked with women all round the world would not refuse to bed his lawfully-wedded wife?

Seffie nodded to her footman, giving him the signal to rap the door knocker. Let battle commence.

The footman knocked twice more before the door opened a cautious crack to allow an elderly maid to poke her beaked nose around the edge of it.

Seffie stepped forward, and footman pushed the door fully open, overcoming the maid’s brief resistance. Not a maid. The bundle of keys at the woman’s waist indicated the housekeeper. She stepped backward at the aristocratic advance and curtseyed.

“I am Lady Clairmont,” Seffie said. “Announce me to your master.”

The housekeeper shook her head, cringing as if she expected a blow. “’is lordship be asleep,” she whined. “Them all be asleep. Even Mr. Barton, who be the butler. All night they was up, and be as much as my life to wake ’uns.”

Seffie gave a short nod. She should have expected this. “Show my cousin and my maid to a parlour where they can wait, and send someone to conduct me to Lord Clairmont’s room,” she commanded. She added instructions for refreshments to be brought to her and her cousin, and told William to stay with the other two women. They might need a stout defender in this house, though perhaps they could all retreat to a nearby inn before the other denizens woke up.

“Should you be alone, ma’am?” Polly ventured, and Anna agreed. “We could send for another of the men to go with you.”

What Seffie had to say to her husband was best said in private. “I shall be safe in Clairmont’s room,” she insisted, and followed another servant, this one still straightening her cap and tying her apron, up the long curve of the stairs.

It wasn’t until the housekeeper put a hand up to knock on the door that it occured to Seffie that her husband might not be alone.

“Don’t knock,” she said, hastily. Should she enter, or not? She had come this far, and she did not like to retreat.

She tried the handle. Locked. “Open it,” she insisted.

The housekeeper frowned but obeyed.

“That will be all, Mrs… ?”

“Barton, my lady. I’ll bring thy tea.”

“Do that.”

Seffie waited until Mrs. Barton retreated back towards the stairs before opening the door enough to slip silently into the bedchamber. A large four-poster bed dominated the room. To Seffie’s relief, the man sleeping in it was alone. She was less comfortable with his attire—or lack thereof. He lay sprawled on his front, his face turned away from her, the sheet pushed down to show his bare back from his broad shoulders to his narrow waist.

Seffie froze in the doorway. He was no longer pudgy; nor was the glorious expanse of skin marred by pimples or any other blemish. She gave herself a shake, stepped inside, and closed the door. She might be a virgin, but she hadn’t lived in a box for all the past years. Being married didn’t stop her from admiring a male form, and she knew desire when she felt it. She had never acted on it, and she could ignore it now. She wasn’t here to lust after her husband. Actually, that wasn’t quite accurate—if they could resolve the distance between what she wanted and what he apparently wanted, lust would be appropriate and useful in gaining her the children she yearned for. Provided he felt the same about her.

For a wild moment, she was tempted to undress and climb under the sheets with him, but she resisted the impulse. The maid would return with the tea. Besides, they should talk first; negotiate a way forward. In truth, despite her unexpected physical response, she was a little afraid. He was a stranger, and she had only the most general of ideas about what to expect of the marital act. It sounded like something better done with a friend, or at least a more than casual acquaintance.

She took a seat in the window bay, and pulled the book she had been reading from her reticule. From here, she could see his face. She would have walked past him in the street, except that she was very familiar with certain elements of his face. That square cleft chin appeared in a number of paintings at Clairhaven; that strong nose and those arched eyebrows in others. The boy of fifteen was still there, too, when she examined him closely, pared down, toughened, more square and decidedly formidable. In repose, he was not classically handsome, but he was attractive.

Her husband. She whispered it, to see if it felt more real when voiced aloud. “My husband.”

October 23, 2019

Escalating stakes on WIP Wednesday

A good story raises the stakes, chapter by chapter. In my favourite stories, the stakes are high to start with and keep getting higher. I’ve enjoyed books where the stakes are as simple as the happy outcome of a love story. Even in those, the story requires raising the stakes: rumours or misunderstandings that threaten the outcome, family disagreements, incompatible life goals. Add a suspense thread, and the stakes can include the fates of dependents, even lives. Different genres, different stakes. Failure must always be a viable option, even if we, the reader, know the author won’t let that happen.

Today, I’d welcome you to share an excerpt where the stakes are rising. Mine is from The Darkness Within. My hero is trying to gain entry to the community. Sebastian, by the way, is a memory. He has been dead for 10 years, but he won’t stop talking inside Max’s head.

Finally, Faversham looked in Max’s direction. When he caught Max’s gaze, he tipped his head to one side, his eyebrows lifting in question. Max pushed off from the cart. Time to discover whether he could pass the prophet’s test.

The first questions were about his name and history. He gave an edited version of the truth. He was Zeb Force, a workhouse brat turned apprentice turned soldier turned wandering handyman.

Faversham was sympathetic. “Many soldiers have found jobs hard to come by,” he condoled. “You have no family to help you? Your old master? Comrades in arms or friends from your workhouse days?”

Sebastian, cynical as ever, perked up at that. “He likes that you are alone,” he observed.

Sebastian thought the worst of everyone. Still, Max told Faversham, “No, sir. No one.” In his mind’s eye, he saw Lion, anxious to get home to his beloved countess. “I haven’t seen anyone from the workhouse since I was eight. My old master—it was his death that sent me into the army. Those I fought with—the ones who survived—have their own lives.”

Faversham nodded, his face grave. “You have suffered many losses, Zeb.”

“I want a place to belong,” Max said, the fervent intensity of the words surprising him.

“What sort of work have you been doing?” Faversham asked, then held up a hand to stop Max’s answer. “No. What I really want to ask is what could you do in the community, Zeb? What are your skills?”

“I can turn my hands to most things,” Max replied. “I have shod horses, dug ditches, built walls, ploughed fields, stitched wounds, taken dictation to write letters, kept accounts. I can teach, too, if that is of use.”

Faversham’s eyes widened. “An unusual set of skills for a workhouse brat. You learned to read and write in the army?”

Max shook his head. “My master had me taught. He was a steward.” That was what Sebastian always said: ‘I hold the wealth created by those who came before me as steward for those who will follow.’ “He planned for me to replace his secretary,” Max explained.

“You outstripped your first tutor in less than a year,” Sebastian reminded him. “I was so proud. I gave you a holiday while I found a new one; do you remember? I took you with me to my hunting lodge.”

“His successor did not wish to keep you on? I’m sorry to hear that. Still, you found a place in the army. What rank?”

Max had prepared an answer for this. If he passed this test, he would be living at close quarters with Faversham and his people, so he was keeping as close to the truth as he could.

“Someone who knew my master bought me a commission as a cornet. I made lieutenant by the end of the war. My commander put me up for captain, but they wouldn’t give the rank to a workhouse brat.”

“And your regiment?” Faversham asked.

Max named the regiment he had nominally been part of, though he’d gone straight from signing his papers to a hidden training camp that taught and tested the skills they’d recruited him for. The regiment was based far enough north that it was unlikely in the extreme that he’d meet any ex-soldiers who might be supposed to know him.

Faversham fell silent. Max waited, his body relaxed though his mind was on high alert. The disciples talked among themselves, a low murmur of voices a few yards away. The fair made more racket—squeals of excitement, gleeful shouting and angry yelling, vendors’ calls, babies crying, half a dozen different tunes from a score of instruments.

Finally, Faversham seemed to make up his mind. “Very well. I will take you, I must first tell you what you are choosing. You must turn your back on every one and every place you know. People enter heaven with nothing. What you see there; what you experience—you will love it, I am sure, but I invite you in for a trial period only. If we accept you and you accept us, you will be initiated and become one of us forever. If not, we will part ways with no hard feelings.”

He held out a hand. “Are you in?”

Max took it, and accepted the firm handshake. “I am, sir.”

“In Heaven,” Faversham explained, “I am called the One, and addressed as Lord or Father.” He beckoned to the three disciples, ignoring the bodyguards. “Courage? Justice? Peace? Meet Zebediah. He wishes to enter Heaven, and I have agreed.”

Max accepted handshakes and broad smiles from each of the three men. He was in. Now to see if Paul Stedham was still with the community. Briefly, he wondered if Paul was now named for a virtue. “I’d love to know what virtue they’d name you after,” Sebastian commented. “Vengeance, perhaps?”

October 21, 2019

Tea with Harry

London

1919

Harry leaned his head into the wind. London’s weather proved as appalling as his grandfather remembered. He had three hours before the train left again, and he had been too restless to sit in the station. He left his friend Mac on a bench sipping a mug of hot black coffee while he wandered the streets his ancestors once walked.

He found himself drawn to an elegant square in Mayfair, and a grand old mansion. He couldn’t explain what drew him; it was just a feeling really. He stood for a long while staring up and the magnificent old place, while traffic zoomed by behind him, wondering if it could possibly be a private residence. Many of the grand houses had been turned into hospitals or schools. Some even housed museums. He gave into impulse and knocked on the door.

A man in the formal clothing of an earlier time greeted him. How odd, he thought. He soon found it even odder. “Welcome, Lieutenant Wheatly. Her Grace is waiting for you,” the strange man said.

“Her Grace?” Harry parroted.

“Yes. If you would follow me,” the man said. What else could Harry do? He followed.

The man led him to an elegant sitting room where a tiny woman with silvery hair and sparking blue eyes greeted him and invited him to sit. A wave of her hand brought a liveried footman with a cart containing tea and cakes. Conversation seemed unnecessary while they served Harry. What are these people? Reenactors?

The man led him to an elegant sitting room where a tiny woman with silvery hair and sparking blue eyes greeted him and invited him to sit. A wave of her hand brought a liveried footman with a cart containing tea and cakes. Conversation seemed unnecessary while they served Harry. What are these people? Reenactors?

“Pardon me, er, Your Grace, but what era are you meant to represent?”

“Era Harry? You are visiting me in 1819, but I’m getting ahead of myself,” the woman said.

Harry clamped his jaw shut. 1819? She must be mad.

“Let me explain. I am the Duchess of Haverford. I’ve known your family for generations. Why, your great grandfather visited me earlier this month. Of course he is just a gangly adolescent at the moment, and having rather a difficult time of it at Harrow.”

“My great grandfather? Randolph Wheatly?” He had been the last of Harry’s line to live in London, the first to migrate to Canada. Randolph Wheatly died in 1893 when Harry was a toddler.

The duchess beamed at him as if he were a particularly bright school boy.

“The very one! You see, I know your family well, and so when I sensed your distress I had to reach out to you. It must be a very great distress indeed to come to me across… a century is it?” She gazed at him expectantly.

“A century. Surely you know it is 1919 and this…” he gestured around him with one hand, his expression troubled. “Confusing. What it is is confusing.”

The duchess chuckled. “I imagine it is. Let’s just say I knew you needed sympathy and a cup of tea and leave it at that. Don’t try to understand the rest.”

Harry felt his shoulders relax. It had been a long while since he had enjoyed such elegance. The chair and the tea were a far cry from army fare, and finer and more comfortable than even Rosemarie’s cottage—though he’d trade them in a heartbeat to be back with her.

“Suppose you tell me why you are in London and what troubles you,” the old woman said.

“I’m not staying here. I’m merely between trains,” he began. When she looked confused about “trains,” he wondered if he ought to explain the concept but decided not to. “I’m on my way to France to search for Rosemarie. We became separated in the last year of the war.”

“So much grief in time of war,” she murmured sympathetically. “I’m distraught to hear we’re at war with France again a hundred years from now. Does it never end?”

“Actually France was our ally. We fought the Germans for almost five years.”

“Which Germans?” she asked looking as puzzled as Harry felt. He recalled that the various German states unified late in the 1800s, long after this woman’s time.

He stared at her. Can this all be real? Surely not. “All of them, Your Grace,” he muttered.

She said something under her breath about never trusting Prussians, but she smiled up at him immediately. “Tell me about this Rosemarie. Why are you searching for her?”

“I need to reserve space on a repatriation ship to bring her to Canada. For that I need a marriage certificate. But I can’t marry her if I can’t find her. I’ve been given leave and I’m on my way back to Amiens to search for her and Marcel.”

“I need to reserve space on a repatriation ship to bring her to Canada. For that I need a marriage certificate. But I can’t marry her if I can’t find her. I’ve been given leave and I’m on my way back to Amiens to search for her and Marcel.”

“And who is Marcel?”

“Her son. Soon to be mine, I hope,” he replied.

“How wonderful! You are a fine young man, Harry Wheatly. Your great grandfather will be proud of you.”

“Now you best hurry. You won’t want to miss that… train, did you call it?”

He surged to his feet. “Yes train, and I most certainly don’t want to miss it. Thank you for the tea, Your Grace. It has been entertaining.”

“I’m glad to give you a respite. Now go find your Rosemarie, and God go with you.”

Moments later he stepped out of the mansion onto a busy street and rushed away dodging cars and rain puddles in the direction of St. Pancras Station.

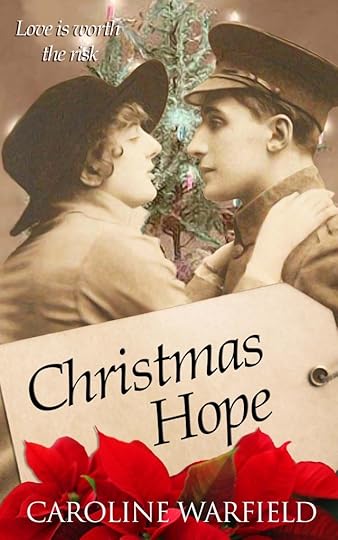

Harry is the hero of Christmas Hope, a wartime story in four parts, each one ending on Christmas, 1916-19.

When the Great War is over, will their love be enough?

A wartime romance in four parts, each ending on Christmas, 1916-1919.

After two years at the mercy of the Canadian Expeditionary force and the German war machine, Harry ran out of metaphors for death, synonyms for brown, and images of darkness. When he encounters color among the floating islands of Amiens and life in the form a widow and her little son, hope ensnares him. Through three more long years of war and its aftermath, the hope she brings keeps Harry alive.

Rosemarie Legrand’s husband left her a tiny son, no money, and a savaged reputation when he died. She struggles to simply feed the boy and has little to offer a lonely soldier, but Harry’s devotion lifts her up. The war demands all her strength and resilience, will the hope of peace and the promise of Harry’s love keep her going?

Buy links:

Barnes & Noble * Kobo * Apple

Amazon: US * UK * CA * AU * IN

October 20, 2019

Sunday Spotlight on Christmas Hope

A compelling story of love in impossible circumstances

I loved this book.

Caroline Warfield invariably engages our hearts, and Christmas Hope is no exception. Harry has the heart of a poet; a heart that is sickened by life with the Canadian Forces in the trenches of WWI. Rosemarie is a widow struggling to feed herself and her son, Marcel, while withering under the contempt of small-minded locals. Harry’s hunt for his lost bible brings them together. For Harry, Rosemarie and Marcel come to represent all that is good and peaceful. For Rosemarie, Harry is a light in the darkness.

The book follows them through four years, each ending in a Christmas, as their relationship deepens in brief encounters stolen out of the ruinous war. Even the end of the war does not bring peace for this small would-be family — Rosemarie has been evacuated out of the path of the battles, and she and Harry have lost touch with one another.

Part 4 of the book is set in 1919, beginning as Harry faces repatriation from Wales to Canada, his father’s well-meant interference in his future, and the influenza that devastated the post-war world. Rosemarie leaves her son with his uncle to search for her beloved. Nothing is easy.

I enjoy Warfield’s decent men and courageous women. Harry might just be one of my favourites. I particularly cherished his scenes with Marcel. As for Rosemarie, watching her overcome obstacle after obstacle, including her own self doubt, broke my heart — but I trusted Warfield to mend it again, and she did. Right at the eleventh hour, which is the best time, in a novel.

I strongly recommend Christmas Hope.

Christmas Hope

When the Great War is over, will their love be enough?

A wartime romance in four parts, each ending on Christmas, 1916-1919.

After two years at the mercy of the Canadian Expeditionary force and the German war machine, Harry ran out of metaphors for death, synonyms for brown, and images of darkness. When he encounters color among the floating islands of Amiens and life in the form a widow and her little son, hope ensnares him. Through three more long years of war and its aftermath, the hope she brings keeps Harry alive.

Rosemarie Legrand’s husband left her a tiny son, no money, and a savaged reputation when he died. She struggles to simply feed the boy and has little to offer a lonely soldier, but Harry’s devotion lifts her up. The war demands all her strength and resilience, will the hope of peace and the promise of Harry’s love keep her going?

Buy links:

Barnes & Noble * Kobo * Apple

Amazon: US * UK * CA * AU * IN

Excerpt

Harry woke with a stab of fear. He reared up, groping for his rifle, afraid he had fallen asleep on duty.

He sank back into the bed as awareness flooded in. No enemy lurked. He reposed in soft covers in an unfamiliar room, his clothes had gone missing, and he wasn’t alone. A small boy watched him steadily from the doorway. Memory flooded back—fleeing from Lens, frantic to get to Rosemarie. He hadn’t deserted; he’d gotten leave or rather had it thrust on him with orders from Captain Mitchell to come back whole. He remembered a frantic journey, reaching her cottage, falling against the door, and not much else.

“You are dirty,” the boy said, approaching the bed. Harry ran a hand across the stubble on his face. It came away filthy.

“Apparently so. And you are tall, much too tall to be Marcel.”

The boy stiffened in offense. “I am Marcel. I am three.” He held up three fingers.

Before Harry could think what to say next the boy ran to the stairs shouting, “Maman, ‘arry is awake!”

His soldier’s instinct took stock of his surroundings. The room spread out under peaked roof beams. He doubted he could stand upright anywhere but the center of the room; it had only one way out, the direction Marcel had taken. He had slept in an actual bed. Rosemarie’s bed, it has to be. Did we share it? He thought not. If we had, I would certainly remember.

The blankets he lay in were worn and mended, but warm enough and clean—at least they had been until he lay in them. Since whoever took his clothing left his drawers and nothing else, he thought it best to stay nested where he lay. A tiny window at the peak of the roof let in a beam of light. It appeared to be slanted low in the sky. Does that window face east or west? Did I awake at dawn or sleep round the clock?

He could hear the boy talking with his mother and the sounds of pots and pans. Sharp awareness told him one more thing. Somewhere in this haven, fresh bread baked, sweet dough, he thought. His mouth began to water. With that, came the realization of gnawing hunger.

He debated what to do, undressed and feeble as he was. He envisioned Rosemarie fussing over her baking, and an even greater hunger overcame him, one he might do well to tame before he got out from the covers.

Her appearance in the doorway, his own vision of heaven itself, carrying a basin of steaming water, saved him the decision.

She put it on the little three-drawer chest against the opposite wall, along with the towel and rag she had over her arm.

“You’ll want to wash up,” she said. “I’m sorry we have no bathing tub. I found Raoul’s robe in storage,” she added, pointing to a purple robe draped over a trunk. The trunk, Marcel’s pallet at the foot of the bed, and a chest of drawers furnished the tiny room. She looked oddly shy, as if having him tucked in her bed with her late husband’s things nearby made her awkward.

Raoul. He had forgotten the husband, long dead now. The acid of pointless jealousy ate at him, and he could think of nothing to say. He sat up, letting the blanket fall to his lap, and her eyes dropped to the floor, but not before he caught the heat when she spied his naked chest. The jealousy fell away.

Meet Caroline Warfield

Caroline Warfield

Award winning author Caroline Warfield has been many things: traveler, librarian, poet, raiser of children, bird watcher, Internet and Web services manager, conference speaker, indexer, tech writer, genealogist—even a nun. She reckons she is on at least her third act, happily working in an office surrounded by windows where she lets her characters lead her to adventures in England and the far-flung corners of the British Empire. She nudges them to explore the riskiest territory of all, the human heart.

Visit Caroline’s Website and Blog http://www.carolinewarfield.com/

Meet Caroline on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/carolinewarfield7

Follow Caroline on Twitter https://twitter.com/CaroWarfield

Email Caroline directly warfieldcaro@gmail.com

Subscribe to Caroline’s newsletter http://www.carolinewarfield.com/newsletter/

Amazon Author http://www.amazon.com/Caroline-Warfield/e/B00N9PZZZS/

Goodreads https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/8523742.Caroline_Warfield

Bookbub https://www.bookbub.com/profile/caroline-warfield

Caroline’s Other Books

Amazon https://www.amazon.com/Caroline-Warfield/e/B00N9PZZZS/

Bookshelf http://www.carolinewarfield.com/bookshelf

October 18, 2019

Making glass for windows

Until the early 20th century, all glass was hand-blown. This video shows how they made large sheets back in the day. Invented in the 17th century, it was expensive and didn’t become the common method until the early 19th century. Something to keep in mind when writing a scene in which someone is seen in a window is that such glass had ripples and faults. The view would have been distorted to some extent.

Even more so before that, for all those centuries when window glass was crown bullions, or bullseye glass, as shown below. This video also shows the cylinder method.