Jude Knight's Blog, page 74

January 26, 2020

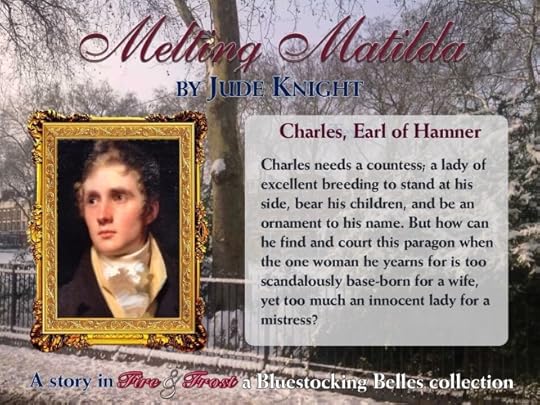

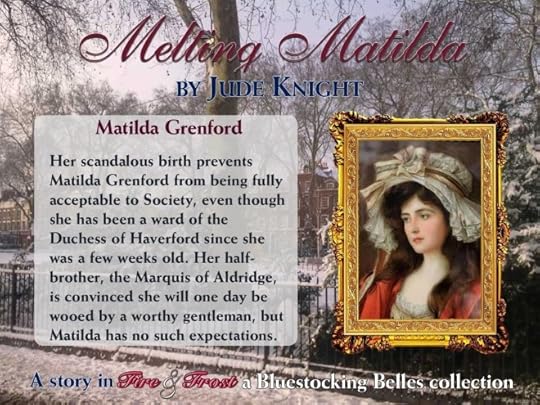

Spotlight on Fire & Frost: Melting Matilda

Fire & Frost is out in just over a week, and I’m really excited. I think this collection is the best the Bluestocking Belles have done yet! I’m going to be celebrating each of the novellas over the next couple of weeks, with excerpts and everything!

First up, my own novella, Melting Matilda.

Her scandalous birth prevents Matilda Grenford from being fully acceptable to Society, even though she has been a ward of the Duchess of Haverford since she was a few weeks old. Matilda does not expect to be wooed by a worthy gentleman. The only man who has ever interested her gave her an outrageous kiss a year ago and has avoided her ever since.

Charles, the Earl of Hamner is honour bound to ignore his attraction to Matilda Grenford. She is an innocent and a lady, and in every way worthy of his respect—but she is base-born. His ancestors would rise screaming from their graves if he made her his countess. But he cannot forget the kiss they once shared.

Here’s an excerpt:

For more than a year, Charles had kept to himself the fact that the Haverford Ice Princess kissed like a flame. As he abandoned his own granite facade for once and for all, he rejoiced in her heat. This time was even better than the last, and the best was yet to come. Though perhaps not here in a family parlor where her brother or sisters could walk in at any time.

“I hope you do not want a long betrothal,” he whispered, between kisses.

She broke off her attempt to completely unravel his cravat. “Not long,” she agreed.

Her fervent answer demanded that he kiss her again, losing himself so deep he didn’t know they were no longer alone until a voice behind him said, “I trust you are betrothed to my sister, Hamner, for it would be most inconvenient to start the evening’s celebrations by killing you.”

Meet my hero, walking in the fog.

Charles lifted his hat in greeting, and sensed rather than saw her shoulder’s ease. Did she think an assailant unable to ape good manners? Stride by stride he approached, and stride by stride she came into better focus.

His heart sank as he recognized her. Of all the females to need his help, it had to be the Haverford Ice Princess. Nonetheless, manners demanded that he lift his hat again, bowing. A slight bow, peer to commoner, but still a bow. He fiercely resented the necessity, telling himself that a female with her breeding — or lack thereof — should not expect such recognition from a gentleman, but the ward of the Duchess of Haverford had every right to be treated with respect.

Miss Grenford returned a small curtsey, though a quick darting look at the fog hinted that she no more wanted to be rescued by him than he wanted to play knight errant to her.

Matilda Grenford had been bedeviling Charles since she first made her entry to Society, side by side with her equally problematic sister. No. She was more problematic.

“Lord Hamner.” Just that, and in freezing tones. No explanation of her presence alone in the street. No pleas to see to her safety. No smile.

“Miss Grenford.” How he wished Miss Grenford were more like her sister so he could blame her, instead of himself, for the insult that had sunk him so low in her regard. He’d fought an unwelcome and inappropriate lust in her presence since he asked her to dance at her debut ball two years ago. It was, of course, only lust. He would have recovered long ago, he was certain, if she had been in his keeping, but that would never happen.

Besides, for all that he told himself he would tire of her, he could not imagine it. He would not take a mistress he could not give up. He had sworn on his mother’s grave that he would have no other women when he married. He would never do to his wife and children what his father had done; marrying a proper lady when his heart was with his irregular family.

To marry Miss Grenford was unthinkable. When he wed, it would be to a maiden of pure bloodlines, both maternal and paternal. He owed it to his name. He owed it to the heir he and his wife would raise to the dignities of his title, and to any other offspring.

To offer protection to a ward of the Duchess of Haverford was impossible. She behaved like a proper lady, whatever her appearance. If he compromised her, he would be honor bound to offer for her, and would do so without even the incentive of an angry brother. The Marquis of Aldridge would avenge insult to any of the Grenford sisters, and Aldridge was deadly with both sword and pistol, but Charles’s own sense of what was due a lady would propel him to the altar without such a threat.

Sometimes, he struggled to remember that would be a bad outcome.

And my heroine:

If the two of them made it out of the near-invisible city streets alive, Matilda Grenford was going to kill her sister Jessica, and even their guardian and mentor, the Duchess of Haverford, wouldn’t blame her. Angry as Matilda was, and panicked, too, as she tried to find a known landmark in the enveloping fog, she couldn’t resist a wry smile at the thought. Aunt Eleanor was the kindest person in the world, and expected everyone else to be as forgiving and generous as she was herself. Matilda could just imagine the conversation.

“Now, my dear, I want you to think about what other choices you might have made.” The duchess had said precisely those words uncounted times in the more than twenty years Matilda had been her ward.

When she was younger, she would burst out in an impassioned defense of whatever action had brought her before Her Grace for a reprimand. “Jessica is not just destroying her own reputation, Aunt Eleanor. Meeting men in the garden at balls, going out riding without her groom, dancing too close. Her behavior reflects on us all.”

Was that the lamppost by the corner of the square? No; a few steps more showed yet another paved street with houses looming in the fog on both sides. Matilda stopped while she tried to decide if any of them were in any way familiar.

Meanwhile, she continued her imaginary rant to the duchess. “Even in company, she takes flirtation to the edge of what is proper. This latest start — sneaking out of the house without a chaperone or even her maid — if it becomes known, she’ll go down in ruin, and take me and Frances with her.”

Matilda had gone after her, of course, taking a footman, but she’d lost the poor man several mistaken turns back. Matilda had been hurrying ahead, ignoring the footman’s complaints, thinking only about bringing Jessica back before she got into worse trouble than ever before. Now Matilda was just as much at risk, and she’d settle for managing to bring her own self home to Haverford House, or even to the house of a friend, if she could find one.

Home, for preference. Turning up anywhere else, unaccompanied, would start the very scandal Matilda had followed her sister to avoid. If Jessica managed to make it home unscathed, Matilda would strangle her.

In her imagination, she could hear Aunt Eleanor, calm as ever. “Murder is so final, Matilda. Surely it would have been better to try something else, first. What could you have done?”

Fire & Frost : released 4 February. Buy now!

Join the

The Ladies’ Society For The Care of the Widows and Orphans of Fallen Heroes and the Children of Wounded Veterans

in their pursuit of justice, charity, and soul searing romance.

Join the

The Ladies’ Society For The Care of the Widows and Orphans of Fallen Heroes and the Children of Wounded Veterans

in their pursuit of justice, charity, and soul searing romance.

The Napoleonic Wars have left England with wounded warriors, fatherless children, unemployed veterans, and hungry families. The ladies of London, led by the indomitable Duchess of Haverford plot a campaign to feed the hungry, care for the fallen—and bring the neglectful Parliament to heel. They will use any means at their disposal to convince the gentlemen of their choice to assist.

Their campaign involves strategy, persuasion, and a wee bit of fun. Pamphlets are all well and good, but auctioning a lady’s company along with her basket of delicious treats is bound to get more attention. Their efforts fall amid weeks of fog and weather so cold the Thames freezes over and a festive Frost Fair breaks out right on the river. The ladies take to the ice. What could be better for their purposes than a little Fire and Frost?

Apple Books

Barnes & Noble

Kobo

Smashwords

Amazon Global: AU BR CA DE ES FR IN IT JP MX NL UK

January 23, 2020

A picnic by any other name…

Sometimes, you dodge a bullet by sheer happenstance. This week, Ella Quinn, in her wonderful resource on FaceBook, Regency Romance Fans, posted about the meaning of the term ‘picnic’ in Regency England, and I went back and did some more research.

I’d looked into it for the Bluestocking Belles new collection, Fire & Frost. The heroines of our five stories make baskets of food to be auctioned for the charity that is underpinning theme for the collection. The food is to be eaten at a Venetian Breakfast on the ice of the frozen Thames (a last minute change to take advantage of the unusually cold weather).

I knew, of course, that a Venetian Breakfast was an afternoon entertainment at which food was served. The ladies, in morning dress (anything worn before the change into dinner gowns in the early evening), and gentlemen of Society would have been familiar with the term ‘picnic’.

I knew, of course, that a Venetian Breakfast was an afternoon entertainment at which food was served. The ladies, in morning dress (anything worn before the change into dinner gowns in the early evening), and gentlemen of Society would have been familiar with the term ‘picnic’.

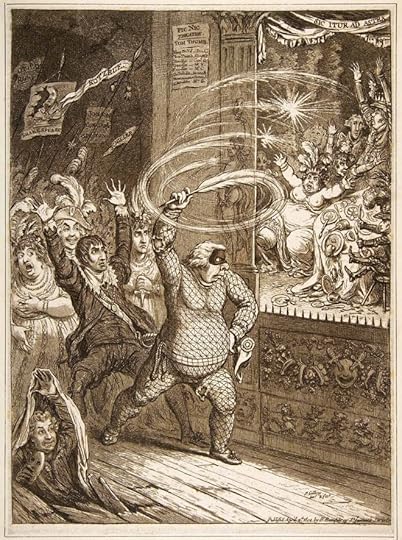

The term started in France as pique-nique, and referred to what we today would call a collaborative meal. Everyone either brought food or drink, or they paid something towards the costs. Pique-niques became very popular in Europe during the 18th century, and when people fled the French Revolution, some of them anglicised the term and started a Pic-Nic Club. The plan was to get together to eat, drink, gamble, and put on theatricals. Around 200 people joined, and the dramatist Sheridan saw it as competition for his own professional theatre. In 1802, the resulting spat spread across the newspapers, with cartoons and the lot.

Blowing-up the Pic-Nic’s or Harlequin Quixote Attacking the Puppets, vide Tottenham Street Pantomime, James Gillray, April 2

The kerfuffle popularised the term, probably because it sounded kind of catchy. I’m guessing people began to apply it to the outdoor entertainments that were already happening, where people all brought their own food and sat and ate together. Jane Austen used it in the outdoor sense in Emma, and Dorothy Wordsworth used it in letters to a friend, both close to the period of Fire & Frost (Wordsworth in 1808 and Austen in 1816). So I think we could stretch a point to say that our Regency heroes and heroines of the winter of 1813 to 1814 might be a little ahead of their times in planning an outdoor event and calling it a picnic.

However, we were saved by the collaborative original meaning of the word. Our ladies are preparing baskets to share with the successful bidder at the auction. Hurrah! Picnic baskets.

In time, the outdoor sense outlived the joint meal sense. Meanwhile, I’ve sent a couple of line edits to make sure the picnic pedants (myself among them) don’t trip over an anachronistic name for a social practice. Phew!

***

Reference: https://www.historytoday.com/archive/historians-cookbook/history-picnic

January 22, 2020

Avowals of love on WIP Wednesday

Isn’t part of the fun of a romance seeing a strong man brought to his knees? Today, hit me with your excerpts where one party or the other speaks of their love. Could be a proposal, as in the following excerpt from Melting Matilda, my novella in the soon to be published Fire & Frost.

“I have been attracted to you since the first time we danced, but that is desire, and desire is a part of love but not the whole. I do desire you, my love, more and more each day, but I also admire you, I like being with you, I enjoy talking to you, I respect you. I want to see you every morning when I wake, to spend my days with you, to have the right to dance the first waltz with you at every ball, and to go home with you every night. I want to see your belly rounded with our child, and watch you as you gently teach them the way I’ve seen you teach your little sister. I want you and only you as my countess and the mother of my children. I want to grow old with you, Matilda Grenford.”

He dropped to one knee. “Miss Grenford, I esteem you with all my heart. Will you do me the very great honor of becoming my wife?”

He waited, his anxiety rising as she said nothing, despair taking over as tears rose and began to leak from her pansy eyes. Then she began to nod as she slipped to her own knees and reached out for him. “Yes. Oh, yes. Charles, I love you, too.”

January 20, 2020

Tea with the Ladies

Today’s Monday for Tea post is an excerpt from Melting Matilda, which is now available on pre-order in the box set Fire & Frost. The duchess is holding a meeting of her Ladies’ Society.

They dropped the conversation as they entered one of the less formal parlors, where the duchess waited for them, her current companion at her side, and Cedrica Fournier, her previous companion, already seated before a table, pen and paper ready to take notes.

Madame Fournier had left her position to marry, but she had volunteered to be secretary for this committee. Jessica and Matilda took turns in greeting her with a kiss in the vicinity of her cheek, and as they did, the other ladies began to arrive.

The first part of the meeting was given over to reports. The work of the Society was organized by small groups, sometimes as few as two or three ladies. Lady Felicity Belvoir, through her connections to half the families of the ton, kept them aware of social events at which they could canvas for votes in Parliament. Lady Georgiana Hayden was in charge of writing pamphlets to sway opinion, and Lady Constance Whittles marshalled a miniature army of letter writers for the same purpose.

Many of the Society’s members also volunteered at hospitals where injured veterans were nursed and orphanages that cared for veterans’ children. They visited widows where they lived, some in very insalubrious areas. The duchess agreed with the necessity: how else were they to meet real needs if they did not first talk to those who were suffering? She insisted on the volunteers and visitors travelling in groups and being escorted by stout footmen.

Once all the groups had reported back, they discussed their next fundraising event. The ladies offered one idea after another. The duchess would hold a charity ball, of course, as she did every year, but none of them felt that would be enough to really draw attention to the cause. Something special was called for. Something unusual.

Matilda was not sure who suggested a Venetian Breakfast, but the star suggestion of the day came from a shy girl who was new to the Society. Miss Fairley rose to her feet and waited for Mrs. Berrisford, the meeting’s chair, to notice her.

“I wondered if we might hold a picnic basket auction,” she said, flushing pink at being the center of attention. We have done them at home as fundraisers for the church, and they are very popular.”

Two of the ladies objected that midwinter was hardly time for a picnic, but Mrs. Berrisford called for silence. “Go on, Miss Fairley,” she encouraged. “How does it work?”

“The ladies provide a basket of food,” Miss Fairley explained, “and the gentlemen bid for the right to share the basket with the provider. It is usually the single ladies, of course.” Her voice faded almost to nothing as her blush deepened to scarlet.

Mrs. Berrisford called for order again, as the Society’s members all tried to express an opinion at once.

The duchess rose, and those who had not already stopped talking fell silent to see what she thought. “If we can ensure propriety, ladies, such an auction would be just the thing to bring in donations from the younger gentlemen, who are far more likely to spend their funds on less helpful activities.”

That settled it, of course. Discussion turned to ways and means, and before the meeting was over, several more groups had been established, to cover the various aspects of three events: Venetian Breakfast, auction, and ball, all on the same day.

“Could the auction prize include a dance at the ball later?” Jessica made the suggestion. “That way, gentlemen who have bought a basket will also be obliged to buy a ball ticket.”

The suggestion was met with a hum of approval.

“We will need to enlist the ladies of the ton,” Mrs Berrisford said. “I suggest each of us talks to as many as possible; older ladies to the mothers, younger to the girls. The men, too, of course; but ladies first.”

“We can start at Lady Parkinson’s in two days’ time,” one of the other ladies proposed.

That seemed to be the end of the decision making, though many of the members lingered for another cup of tea and one of the delicious little cakes Monsieur Fournier supplied to the duchess for her meetings.

Matilda and Jessica, in their role as daughters of the house, moved from group to excited group, knowing Her Grace would wish to know what was being said in these more casual conversations.

Everyone was excited by the plans, and more than one person was hoping that the fog would lift so that Lady Parkinson’s soiree would proceed and they could begin their campaign.

January 15, 2020

Thinking series on WIP Wednesday

I’ve done very little writing over the last two months. I’m not entirely sure why. Christmas. Stuff going on with the family. Heavy lifting on a couple of projects at work. But I’m determined to get To Wed a Proper Lady out to beta readers and up for preorder in the next week, and to finish writing the first draft of To Mend the Broken Hearted before the end of February.

I’m also starting the next two, which need to be written at the same time since the heroines are sisters and the stories are concurrent. This week, I’m posting what might be the start of To Tame the Wild Rake, and I invite you to post anything you wish from a series work in progress.

He could not sense the presence of Lady Charlotte Winderfield in his room. The idea was ridiculous.

For a start, the bluestocking social reformer they called the West Wind would rather die than enter the bed chamber of any man, let alone the notorious Marquess of Aldridge.

For another, he was not in a position to sense anything outside of the plump white thighs of Baroness Thirby, unless it was the expert ministrations of her close friend, Mrs Meesham. Lady Thirby’s thighs blocked both his ears and his line of sight, and — in any case — no-one in the room could hear a thing over the yapping sounds she made as he drove her closer to her release. And he could not possibly smell the delicate mix of herbs and flowers that drove him crazy every time he was in Lady Charlotte’s vicinity; not over the musk of Lady Thirby’s arousal.

Damn it. The thought of the chit was putting Aldridge off his own release, despite Mrs Meesham’s best efforts. It was no use pining after her. With his reputation, her family would not even consider him. And if they could be persuaded, she couldn’t. She had made her opinion perfectly clear.

Above him, Lady Thirby stiffened and let out the keening wail with which she celebrated her arrival at that most delicious of destinations. At any moment, she would collapse bonelessly beside him, and he could maybe bury himself in her or her friend and forget all about the unattainable Saint Charlotte.

Instead, Lady Thirby stiffened still further. “What is she doing here?” She scooted backwards so that she could look him in the eye, still crouched, thank the stars. He didn’t fancy the weight of her sitting on his chest. “It’s one thing to do this with Milly. But you didn’t say you were inviting someone else.”

Standing in his doorway, her lips pressed into a tight line and her face white except for two spots of high colour on her cheekbones, was the woman of his fondest dreams. And she didn’t look happy to be there.

The cold air on his damp member told him that Mrs Meesham had likewise abandoned what she’d been doing to stare at the doorway. “She’s never here for a romp, Margaret. She’s one of the Winderfield twins.”

Aldridge sighed. He couldn’t imagine what sort of a crisis had brought Saint Charlotte here, but clearly he was going to have to deal with it.

“My lady,” he said, “if you would be kind enough to wait in the next room, I’ll find a robe and join you.”

She pulled her fascinated gaze from what had been revealed by Mrs Meecham’s movement, and glared at him. “More than a robe. You have to come with me and we have no time to waste.”

“He can’t go out,” Mrs Meecham objected. “Aldridge,” (when Lady Charlotte said nothing but just retreated into the next room), “you can’t go. You haven’t done me, yet.”

Aldridge had already left the bed, and was pulling on his pantaloons. “I am sorry to cut our entertainments short. Sadly, the messenger — who, by the way, neither of you saw,” (he gave them the ducal look learned from his father), “brings me word of an appointment I cannot miss. My heartiest regrets. Please, feel free to carry on without me.” He bowed with all the elegance at his command. He could shrug into his waistcoat and coat and pull on his boots while she told him what the problem was. It was a little late to worry about appearing in front of her improperly dressed.

January 13, 2020

Tea with a concerned mother

Eleanor, Duchess of Winshire had known Mia Redepenning since she was a child — a small girl with big eyes much overlooked by her only relative, her absent-minded father. Back when Eleanor was Duchess of Haverford, the man spent six months at Haverford Castle cataloguing the library while his little daughter did her lessons at a library table or crept mouse-like around the castle or its grounds.

Who would have thought, back in the days that Mia first became acquainted with the duchess’s goddaughter during a visit, that she would one day be a connection of Kitty’s and of Eleanor herself, by marriage? Or that, more than twenty years after the first time Mia and Kitty had joined Eleanor for tea in the garden, they met for tea whenever they were both in London?

Not that Mia and her husband Jules spent much time in London. He owned a coastal shipping business in Devon, and they lived not far from Plymouth, but Eleanor suspected that the main reason for their dislike of London Society lay in their three oldest children. And those children, if Eleanor was not mistaken, were the reason for Mia’s call today, and her distraction.

“Yes, I will help,” she said.

Mia, startled, opened her eyes wide.

“You want a powerful sponsor to introduce your Marsha to Society, and I am more than happy to bring her and Frances out together, my dear. Marsha is a very prettily behaved girl, and will be a credit to you and to me.”

Mia laughed. “I was wondering how to work around to the subject, Aunt Eleanor. I should have known you would see right through me.”

“It won’t be entirely straightforward, my dear,” Eleanor warned. “Thanks to that horrid man that kidnapped Dan all those years ago, everyone who was out in Society when you brought the children back from South Africa know what their mother was to your husband. Most people won’t be rude to Marsha’s face, not when she is sponsored by your family and mine. But they will talk behind our backs, I cannot deny it.”

“Talk behind our backs, I can handle,” Mia commented, “and the children all know the truth, so they cannot be hurt by having it disclosed.” She frowned. “But will they really invite her to their homes? Will she have suitors?”

“The highest sticklers will ignore her,” the duchess said. “She might not receive tickets for Almacks. But for the most part, Society will pay lip service to story you tell them, since what you tell them is supported by the Redepennings, the Winshires, the Haverfords and all our connections.” She returned Mia’s tentative smile.

“I have done this before, my dear, and am about to do it again. All the world knows my wards are more closely related to the previous duke than we admit, but as long as I insist that they are distant connections, born within wedlock to parents who died and begged me to take them in, they all pretend to believe it. As to suitors, Matilda married well, and my poor Jessica’s problems had nothing to do with her bloodlines — the match seemed a good one at the time. I expect Frances to also make an excellent marriage.”

Mia shook her head slowly. “They are wards to a duchess. Jules and I are very ordinary by comparison. We can dower our girls, though, and as long as we can protect them from direct insult, we do not wish to deny them the same debut as their cousins and their younger sisters.”

“No need to deny them. The Polite World will accept that Marsha is, as the public story has it, the daughter of a deceased couple that Jules knew while he was posted overseas with the navy. We shall watch them closely to keep the riff raff at bay, and they will have a marvelous time, as shall you and I, Mia.” She held out her hand, for all the world as if they were men sealing a business deal, and after a moment, Mia took her hand and shook it.

Mia and Jules have their story in Unkept Promises, where you can meet Marsha, Dan, and their little sister. Matilda’s love story is coming soon, in Melting Matilda, a novella in Fire & Frost. Jessica is also introduced in that story. Her tragedy will be a sub plot of her brother’s story, the third book of The Children of the Mountain King series. As to Eleanor’s story, it spans that series, and concludes in the sixth novel.

January 10, 2020

Write what you know (and if you don’t know, find out)

Beginning writers soon hear the advice ‘write what you know’. Often, teachers of writing classes interpret this to mean ‘write about the places and activities, and base your characters on the people, in your own life’.

Which sucks for writers of historical fiction, fantasy, or sf.

Even leaving aside questions of time and space, a literal interpretation limits people to writing within their own race, class, age, gender, religion, and physical or mental condition. I totally agree with those who want fiction to be more representative of the glorious and diverse range of human kind. Tribalism is the scourge of civilisation, and those who tell stories have an obligation to show that the differences between people make them interesting, not scary; that difference does not mean wrong.

Know what you write

On the other hand, there’s a non-literal interpretation. Every writer I know mines their own life and their own feelings for the emotional energy that goes into a story. They study the people around them to give dimension to their own characters. They research so that the facts they portray are accurate.

I write historical romance, mostly set in places I’ve never been to and involving societies I’ve never lived in. I read historical research and primary sources. I watch documentaries and other videos set in the places my characters travel. (A bike tour gives almost a horse rider’s view of the countryside.) I talk to other people who are studying the same topics. I take classes. I read some more. I stop mid-sentence to check facts, such as the time from the onset of fever to the first appearance of the rash in smallpox.

And I check things out with experts. A battlefield medic and an emergency room nurse read my operation scene in A Raging Madness. I sent the draft of Paradise Regained to the Iranian wife of my cousin’s son. A kura (woman elder) of the people descended from the tribe at Te Wharoa agreed to look at Forged in Fire for me. I’m not going to stop writing about diverse characters, but I’m also going to be careful that my unthinking assumptions don’t trap me into being offensive.

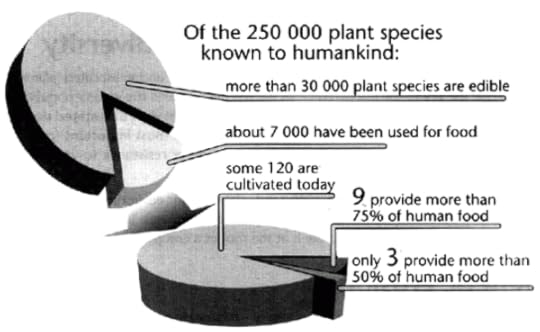

Life is rich, but we human beings have a habit of simplifying it to our own detriment. For example, there are thousands of edibles plant species in the world, and each of them comes in multiple types. We cultivate around 120 today. Three of those crops account for half of all food eaten on the planet.

We storytellers can (and some do) create a Regency society devoid of people of colour, LGBTQ characters, people with disabilities, poor people, people of different faiths. It sure isn’t true to history, and it’s also boring. Those who do write characters that represent such diversity often come from a community that has been marginalised, and they protest at being further marginalised by being blocked from publication and being shoved off into a corner if they are published. The assumption is that people want to read what they know.

I think — I hope — the assumption is wrong.

So let’s be brave

If you’re a reader, choose to read a novel that challenges your assumptions about your favourite historical era. And please, put your suggestions for novels to read into the comments so we all have a chance to try something new.

If you’re a writer, include diverse characters. Go out and learn so you know what you write. Present humankind in all its wonderful variety. Here’s a resource list, courtesy of Louisa Cornell, who says she got some of the list from Vanessa Riley (who writes great novels with black heroes and heroines).

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Equiano; or Gustavu Vassa, the African written by Himself

Children of Uncertain Fortune: Mixed-Race Jamaicans in Britain and the Atlantic Family, 1733-1833 by David Livesay

Black London: Life Before Emancipation by Gretchen Gerzina

Britain’s Black Past by Gretchen Gerzina (3/31/20)

A South Asian History of Britain: Four Centuries of Peoples from the Indian Subcontinent, Michael Fisher, Shompa Lahiri and Shinder Thandi. London: Greenwood Press, May 2007.

The Chinese in Britain – A History of Visitors and Settlers by Barclay Price (2019).

The Chinese in Britain, 1800 – present, Economy, Transnationalism by Benton Gomez and Gregor Edmund

Chinese Liverpudlians: A history of the Chinese Community in Liverpool, by Maria Lin Wong. Liver Press, 1989.

Poor Relations: The Making of a Eurasian Community in British India, 1773–1833. by Christopher J. Hawes

The Infidel Within: The History of Muslims in Britain, 1800 to the Present. by Humayun Ansari

(And here’s what 31 authors said about Write What You Know.)

January 8, 2020

New Year’s goals on WIP Wednesday

So what are your writer goals for 2020? Can you share an excerpt that relates to those goals? One of mine is to publish at least the first four novels in The Children of the Mountain King.

Paradise Regained, the prequel, went out in December. Melting Matilda, an associated novella, is in the Belles’ box set Fire & Frost, published on 4 February. And I hope to have the preorder for To Wed a Proper Lady up by the end of the weekend, with publication early in April.

As always, put your extract in the comments. Mine is from the next Mountain King novel: To Mend the Broken-Hearted.

Ruth roused from a doze in the small dark hours after midnight, though she hadn’t known her eyes had closed until a sound startled her awake. Something out of place, it must have been, alerting the sentinel in her brain that she’d developed when she and Zyba were out in the field. They had served her father and honed their skills by dressing as boys and riding with the guard squads assigned to escort caravans through bandit country in the mountains and deserts of her homeland.

There it was again. A metallic scrape. Silently, she uncurled from her chair, reaching through the slit in her skirt for the dagger in the sheath strapped to her thigh. Against the gray of the night, a blacker shape climbed onto the window sill, pausing there to whisper. “Lady Ruth?”

Assassins do not usually announce themselves. She could probably acquit the intruder of malicious intent, which meant he was more in danger from the illness than she and her charges where from him.

“Go away,” she told him. “This room is in quarantine. We have four cases of smallpox.”

The man moved, coming fully into the room so she could see hints of detail in the far reaches of the candle light. He was tall, with broad shoulders. A determined chin caught the light as he pulled something from his pocket and sat on a chair by the window. The light also glinted off a head of close-cut fair hair.

“I am aware. Four patients, one of them my responsibility. One exhausted doctor. You need help.” As he spoke, he lifted one bare foot after the other, rolling on a stocking each and then tucking the long elegant foot into a soft indoor shoe.

“I don’t need more patients,” Ruth objected, less forcefully than she might if he had not moved closer so that the light touched half of his face, making the rest seem darker by contrast. What she could see was lean, carved with grief. Dark eyes glinted in the shadows cast by firmly arched brows. His gaze was intent on hers.

“I have had the smallpox, my lady, and I am not leaving, so you might as well make use of me. I’m no doctor, but I can follow instructions. You need sleep if you’re to avoid illness yourself.”

Her tired brain caught up with the comment about his responsibility. “You are Lord Ashbury,” she stated. “You cannot think to nurse the girls.”

“What prevents me?” Ashbury demanded. “My amputation? I have one more hand than you can muster on your own. Their modesty? Leaving aside that you and the maids can manage their bathing and other personal matters, I can free you to look after them by lifting and carrying for you. My dignity? I work my own fields, my lady. I am not too exalted to fetch and carry for the woman who intends to save my niece’s life.” She turned, then, and looked straight at him, and he moved so that the lamp shone directly on his face. A long jagged scar skirted the corner of his eye and bisected his cheek and then one side of his mouth, trailing to nothing on his chin.

“You are not qualified,” she told him.

Ashbury shrugged. “True. I daresay half the world is better qualified than I. But I have done some battlefield nursing and I am here.”

“You cannot stay. I am an unmarried woman. You are a man.” A ridiculous statement. Here, isolated from the foolish scandal-loving world of the ton, who was to know. Besides, she would never put something as ephemeral as ‘reputation’ ahead of the needs of her patients.

He took another meaning from her objection, spreading both hands to show them empty, and saying gravely. “I will do you no harm. I give you my word.”

Of course, he wouldn’t. Even if he were so inclined, he would not get close enough to try. Something of her thoughts must have shown in her face, because one corner of his mouth kicked up.

“I suppose you are a warrior after the fashion of that fiercesome maiden you have guarding the quarantine. You are three-times safe then, my lady, with my honour backed by your prowess and reinforced by the knowledge that any missteps on my part will anger your champions.”

Her spurt of irritation was prompted by Lord Ashbury’s amusement, not by the unexpected physical effect of his desert anchorite’s face, lightened by that flash of humour. “I was more concerned about the impact on our lives if it is known we’ve been effectively unchaperoned for perhaps several weeks.

He raised his brows at that and the amusement disappeared. “My servants are discreet and yours would die for you. Besides, you have your maid with you at all times, do you not? And I have my—” he hesitated over a word; “my charges,” he finished.

His niece and his daughter, Ruth thought, wondering what story explained his reluctance to say the words. No matter. He was determined. He was also right; she needed someone else to share the nursing, and now she had a volunteer. Her attraction to him was undoubtedly amplified by her tiredness. She would ignore it, and it would go away.

She would sleep. At the realisation she could finally hand her watch over to someone else, her exhaustion crashed in on her, and it was all she could do to draw herself together and say, “Come. I will show you what you need to do, and explain what to watch for.”

January 6, 2020

Tea with youthful memories

The Duke of Haverford slammed the door on his way out, but it wasn’t his temper that left his duchess trembling in her chair, her limbs so weak she could do nothing but sit, her chest hurting as she tried to force shallow breaths in and out. She had grown so used to his tantrums that she barely noticed.

“Your Grace?” Her secretary held out a hand as if to touch her then drew it back. The poor girl — a distant cousin just arrived from Berkshire — was as white as parchment. “Your Grace? Can I get you something? Can I pour you a pot of tea?”

Brandy would be welcome. A slight touch of amusement at Millicent’s reaction to such a request helped soothe Eleanor’s perturbation. “I should like to be alone, Millicent,” she managed to say. A lifetime of pretending to be calm and dignified through grief, anger, fear, and desperate sorrow came to her rescue. “Can you please send a note to Lady Carew to ask her to hold me excused today? Ask her if tomorrow afternoon would be acceptable.”

Once the girl left the room, casting an anxious glance over her shoulder, Eleanor stood and crossed to her desk, stopping before the mantel when her reflection caught her eye. If Millicent had been pale, Eleanor was worse — so white that dark patches showed under her eyes, eyes in which the pupil had almost swamped the iris.

It was the shock. Perhaps she would have that cup of tea before she fetched the box.

She poured it, and then added a spoonful of sugar. Two spoonfuls. She normally took her tea unsweetened, with just a slice of lemon, but hot sweet tea was effective in cases of shock, was it not?

With the cup set on the table by the chair, she spent a few minutes moving panels of wood in her escritoire, until the secret compartment at the back opened. She had not taken out the box inside since the afternoon of the day Grace and Georgie had told her — oh, some 15 years ago — that James still lived.

James.

Haverford could shout as much as he liked about Winshire’s heir being an imposter, about all the world knowing that the youngest son of the family had died in Persia three decades ago and more. But Eleanor had known almost as soon as Winshire’s daughter and daughter-in-law knew that James still lived. Of course he would come home now, when Winshire’s other heirs had died. She should have expected it. Why had she not expected it?

Words from Haverford’s rant came back to her as she sipped her tea and looked through the few treasures she had kept all these years, sacred to the memory of their doomed courtship. The ribbon she wore in her hair the first time they danced. Winshire says the man is his son. A dried rose from a bouquet he had sent her. The man has a pack of half-breeds that he claims are his children. Several notes and two precious letters, including the one in which he asked her to elope. Barbarians as Dukes of Winshire? Over my dead body! A handkerchief he’d given her to dry her eyes when she cried while telling him that they must wait; that her father would come around. Better to see the title in the hands of that idiot Wesley Winderfield that handed over to some clothhead.

If she had said ‘yes’, what would have happened? He had a curricle in the mews. They could have left that night, straight from the garden where they’d slipped out for a private conversation. Haverford would not have assaulted her on her way back inside. James would not have challenged him to a duel, wounded him, and been exiled a step ahead of the constable. Eleanor would not have been left with her reputation in tatters, refusing to marry Haverford and unable to marry James.

Or if she had stayed true to her memories of him, and had not finally given way to her sister’s pleadings, for Lydia had been set firmly on the shelf because of Eleanor’s scandal. But they told her James was dead, and what did it matter what became of her after that?

They lied. And now James was back in England, and she would need to meet him and pretend that they hadn’t broken one another’s hearts so many years ago.

A few tears fell onto the letters, and then the Duchess of Haverford packed everything away, dried her eyes and returned the box to its compartment.

She had children who loved her, friends, important work in her charities, and a full and busy life. Weeping over the past and fretting over the future never helped.

Her reflection in the mirror showed her complexion returned to normal, and if her eyes were sad? Well. That was normal, too.

James Winderfield senior and his family are introduced in Paradise Regained. His return to England as a widower and heir to the Duke of Winshire, and the subsequent love story of his son and namesake, James Winderfield junior, is in To Wed a Proper Lady, coming in March or April. The stories of his other children and his nieces are in the following books in the series The Children of the Mountain King.

January 3, 2020

The Greatest Killer

In some parts of England, people with communicable diseases such as smallpox were isolated in so called Pest Houses like this one in Findon.

“The smallpox was always present, filling the churchyards with corpses, tormenting with constant fears all whom it had stricken, leaving on those whose lives it spared the hideous traces of its power, turning the babe into a changeling at which the mother shuddered, and making the eyes and cheeks of the bighearted maiden objects of horror to the lover.”

T.B. Macaulay

For at least 3,000 and perhaps as much as 6,000 years, smallpox was one of the world’s deadliest diseases. In countries where it was endemic, it was a disease of childhood, killing up to 80% of children infected. A person fortunate to escape infection in childhood who then caught the virus as an adult, had a 30% chance of dying. Either way, those who survived the disease were left with lifelong scars but also with lifelong immunity, so they could neither catch the disease nor transmit it to others.

Transmission was from person to person, including from droplets in the air from sneezing, coughing, or even breathing. Worse, body fluids on things like clothing or bedding could carry live viruses.

In countries where the disease was new, with no such protective pool of survivors, the infection rate was horrific and the death rate catastrophic. For example, in the Americas, it’s estimated that smallpox, measles and influenza killed 90% of the native population. Children and adults were affected alike.

Even in Europe, though, smallpox changed the fate of nations. In Britain, it played a part in the downfall of the royal house of the Stuarts. Smallpox put Charles II out of action for several weeks during a crucial time in the Civil War, and killed his brother Henry. Had this Protestant prince been alive when James II’s Catholicism caused the rift with the people, history might have been quite different. All of the new king’s sons died young, one of smallpox. He was succeeded by his daughter Mary and his son-in-law and nephew William of Orange.

Mary died of smallpox towards the end of 1694. Thomas Macaulay described her death as follows:

That disease, over which science has since achieved a succession of glorious and beneficient victories, was then the most terrible of all the ministers of death. The havoc of the plague had been far more rapid; but the plague had visited our shores only once or twice within living memory; and the small pox was always present, filling the churchyards with corpses, tormenting with constant fears all whom it had not yet stricken, leaving on those whose lives it spared the hideous traces of its power, turning the babe into a changeling at which the mother shuddered, and making the eyes and cheeks of the betrothed maiden objects of horror to the lover. Towards the end of the year 1694, this pestilence was more than usually severe. At length the infection spread to the palace, and reached the young and blooming Queen. She received the intimation of her danger with true greatness of soul. She gave orders that every lady of her bedchamber, every maid of honour, nay, every menial servant, who had not had the small pox, should instantly leave Kensington House. She locked herself up during a short time in her closet, burned some papers, arranged others, and then calmly awaited her fate.

During two or three days there were many alternations of hope and fear. The physicians contradicted each other and themselves in a way which sufficiently indicates the state of medical science in that age. The disease was measles; it was scarlet fever; it was spotted fever; it was erysipelas. At one moment some symptoms, which in truth showed that the case was almost hopeless, were hailed as indications of returning health. At length all doubt was over. Radcliffe’s opinion proved to be right. It was plain that the Queen was sinking under small pox of the most malignant type.

All this time William remained night and day near her bedside. The little couch on which he slept when he was in camp was spread for him in the antechamber; but he scarcely lay down on it. The sight of his misery, the Dutch Envoy wrote, was enough to melt the hardest heart. Nothing seemed to be left of the man whose serene fortitude had been the wonder of old soldiers on the disastrous day of Landen, and of old sailors on that fearful night among the sheets of ice and banks of sand on the coast of Goree. The very domestics saw the tears running unchecked down that face, of which the stern composure had seldom been disturbed by any triumph or by any defeat. Several of the prelates were in attendance. The King drew Burnet aside, and gave way to an agony of grief. “There is no hope,” he cried. “I was the happiest man on earth; and I am the most miserable. She had no fault; none; you knew her well; but you could not know, nobody but myself could know, her goodness.” Tenison undertook to tell her that she was dying. He was afraid that such a communication, abruptly made, might agitate her violently, and began with much management. But she soon caught his meaning, and, with that gentle womanly courage which so often puts our bravery to shame, submitted herself to the will of God. She called for a small cabinet in which her most important papers were locked up, gave orders that, as soon as she was no more, it should be delivered to the King, and then dismissed worldly cares from her mind. She received the Eucharist, and repeated her part of the office with unimpaired memory and intelligence, though in a feeble voice. She observed that Tenison had been long standing at her bedside, and, with that sweet courtesy which was habitual to her, faltered out her commands that he would sit down, and repeated them till he obeyed. After she had received the sacrament she sank rapidly, and uttered only a few broken words. Twice she tried to take a last farewell of him whom she had loved so truly and entirely; but she was unable to speak. He had a succession of fits so alarming that his Privy Councillors, who were assembled in a neighbouring room, were apprehensive for his reason and his life. The Duke of Leeds, at the request of his colleagues, ventured to assume the friendly guardianship of which minds deranged by sorrow stand in need. A few minutes before the Queen expired, William was removed, almost insensible, from the sick room.

(In my book To Mend a Proper Lady , a girls school is caught up in a smallpox epidemic, causing my heroine Ruth Winderfield to flee with three girls for whom she is responsible plus two more she promises to deliver home on her way back to London. Of course, she becomes trapped at the home of the girls’ guardian, nursing them and others who fall ill.)