Jude Knight's Blog, page 163

October 11, 2014

Why do I blog? And how?

On the Facebook group English Historical Fiction Writers, one of the members said that she’d been told she needed a blog, and asked for recommendations for a good blogging tool. The discussion segued, in the wonderful way that conversations do, into questions about whether ‘need’ was the right word.

Should writers blog? And if so, why?

As you will quickly realise if you look through my posts so far, I’ve been blogging for less than four weeks. At least as Jude Knight. But I’ve been blogging for a lot longer under my commercial writing identity, and I didn’t even think about whether or not to blog until Lynn’s respondents raised the question.

Key point number one: write a great book

Another discussion on Facebook a few days ago asked whether we write because we enjoy it, or whether we write to make money. Now, not being a fool, I don’t expect to make a fortune as a novelist. Would I like to? Too right! I’d love to write fiction full-time, and for that to happen, it needs to generate enough income to pay the bills.

To sell, though, I need a few things.

First, I need to write a book that is worth reading. Nothing else I need to do even comes close to this in importance.

Second, I need to let people know that the book exists. The kinds of people who read my kind of book. Lots and lots of people. They can’t buy it if they don’t know about it.

And then there are a heap of other practical things that I’m not going to talk about in this post.

My to-do list

If you look into my OneNote personal notebook, you’ll find a to-do list I made way back in May.

My idea was to raise my profile before I published Farewell to Kindness. To me, that means making myself visible to people who might enjoy reading what I’ve written. And that means giving them a reason to visit, which in turn means giving them something that they find interesting.

Liabilities and assets

In making myself visible, I have a few challenges. Here I am at the other end of the feed chain in so many ways.

I’m a new novelist, untried, and, as I said in my very first post, unsure about many, many things.

I’m in New Zealand, far away from most of my potential readers, and unable to easily connect with them in any way except online.

I have very limited time to introduce myself to people, and still write, and still work full-time to pay the mortgage, and still be a wife and grandmother. And let’s not even mention the garden.

And I have a few advantages.

First, I have some practical knowledge of the technicalities of creating and maintaining an online presence:

I work in the writing industry, and have created and maintained a number of websites and blogs

I know a little bit about other social media.

Second – and much, much more important – I really, really like getting into conversations with other people about books and about history.

Social media should be social

This is what blogging should be about, in my opinion. People meeting people and having conversations. So my plan is to blog about the things I’m currently thinking about – research that fascinates me, bits of the writing process, long answers to short online discussions.

I absolutely agree that a blog will not sell books. That’s not its purpose. What it will do, if it serves a useful purpose in the community of writers and history buffs, is attract people to your website (yes, your blog should be part of your website), thereby pushing the website up in search engine results. And search engines respond to changing content, so a blog helps there, too.

And useful content gets shared and it gets comments, and both of these also push the site up in search engine rankings.

Do readers read blogs? I’ve heard arguments both ways, but there is no doubt that readers go to authors’ websites to find out what books that author has. So the more likely you are to appear in the first two or three search pages, the more likely it is that your reader will find you.

Your blog can also be set to automatically update your Facebook page, so if you have a Facebook following, building a blog following should be pretty easy. (I’ve also set my Twitter feed to update my Facebook page, and to post to the right hand column of my blog. More automatic changes, so better search engine results, once again.)

The key, as always, is useful content.

This is a WordPress website

So, to answer Lynn’s initial question, I’ve used WordPress to create a website with a blog as the home page. I like WordPress; I’ve used it before, and I appreciate the broad range of plugins. I also found a very neat series of tutorials that pointed me to plugins that made it really easy to create a multi-functional website.

I particularly like MyBookTable, which turns creating book pages into a snap.

Summary

I’ve been exploring a number of different social media outlets, and here are my conclusions so far.

Blogging is a great way to share stuff I learn.

The website is a kind of an anchor for my online personality.

Facebook lets me connect with all sorts of people, and discover who has information I might be interested, and who needs help I might be able to give.

Goodreads lets me talk to other readers about the books I’ve loved and the ones I haven’t (as do the four or five review blogs I’ve started to follow).

Pinterest is an easy way to collect images I might use later, and keep them in a place where they might be useful to others.

Twitter is useful for small snippets of information, but can also be a great timewaster – I’m going to have to ration my use.

October 10, 2014

A proposal mixed up in a proposition

Here’s the scene I’ve been working on; the one where my hero and heroine confront their differences and realise that they do not have a future. I was trying for an irresistible force and immovable object thing. Disclaimer: this is first draft, unedited, and not proofread.

Just to set the scene, it starts as Rede and Elizabeth leave church on Sunday morning. Rain has stopped the birthday picnic, and so Rede has been commissioned to keep Elizabeth away from the house while the other members of the house party prepare a party for her.

A grinning Willie Bush had the chaise ready for them in the lane, and Rede handed her up into it. He slid in beside her, took up the reins, and told Willie, “Stand away, Bush, and thank you.”

Elizabeth was silent while he guided the horses through the home-going crowd. They passed the gates to the Squire’s house, and turned right into River Road.

Rede had planned this. She should have realised earlier that morning, when she saw his two prize bays hitched to the chaise for the under groom to drive. She was torn between annoyance and a certain pleasure at his persistence.

He broke the silence. “You have been avoiding me, Elizabeth.”

“I have,” she acknowledged, deciding that confrontation was safer than conciliation. “You do not seem to have taken the meaning I intended, however.”

He let out an impatient huff of air. “Should I take silence as an answer? No. I need you to say the words.”

They were silent as he coaxed the horses onto the bridge, then turned to pass the mill.

“I have been told to keep you from the house for one hour,” he said, “so I thought we would drive past the Roman fort, and then back across the bridge at the far end of the estate.”

An hour! How could she bear it, with his long warm thigh pressing against hers under the waterproof cover. She shifted, moving slightly to the left.

“You don’t need to be afraid of me,” Rede told her. “I will never do anything you did not want.”

“And yet, here I am,” she replied, tartly.

He shifted too, withdrawing slightly so that they no longer touched. Perversely, she missed the comfort, and had to fight the urge to follow.

“I won’t deny that I want you,” he said. “I think about you constantly. I dream of you at night. I imagine caressing every inch of you, kissing you, tasting you, completing what we began the other night. If you are honest, Elizabeth, you will acknowledge that you want me, too.”

“What I want or do not want does not matter.” Elizabeth sat up straighter. “All that matters is what my family needs.”

“Can you not have both?” he coaxed. “Can you not meet your family’s needs and your own?”

She shook her head. “If we make one slip, it will be all over the countryside, from here to Bath, that I am your mistress. Already people are talking about us, because I accepted your invitation to stay at the Court. We cannot give them more fuel for the fire. And scandal will destroy Kitty’s chances.”

“If you came to me at night, in the Long Gallery, no-one would know,” he insisted. “I have waited for you every night, thinking of you in the bedroom below me, thinking…”

“No, Rede,” she interrupted firmly. “There can be nothing between us. I will not put my family at risk for the sake of a passing lust.”

He turned towards her, jerking sharply on the reins and setting the horses shying nervously on the narrow hill road. Then, for a few moments, he was occupied with calming them. He was clearly calmer himself when he glanced back at her.

“Do you think it a passing lust then? Not for me, it isn’t. I have never before felt this overwhelming compulsion to be with someone. I don’t just want to make love to every inch of your body. I want to talk to you, spend time with you, meet you at dinner, sweep you into the dance, dress you in clothes that set off your beauty and—yes—and then remove them from you one layer at a time.”

Elizabeth felt the heat of his words setting fire to her core. But she shook her head. It had to be a passing lust. She could not bear to love him. Given her history, there could be no future for them.

Uncomfortable with the direction of her thoughts, she lashed out. “How did you feel about your wife, then?”

She could feel Rede stiffen. Then, as if reaching a decision, he relaxed again. “She came with a trade agreement,” he said. “I would not have chosen to take a wife if I had not needed the agreement. And I would have taken any woman they offered for the sake of the deal. I was lucky that she was comely; and yes, I desired her. But I did not ever want her the way I want you.”

Elizabeth regarded him intently. “But you loved her,” she said. “You had three children by her. When you spoke of her, I heard your grief.”

Rede nodded. “Yes, we had children. She was my wife. We were married by the Catholic priest in her village, and again in the Church of England chapel at St Johns. She was a warm body in my sleeping bag at night, and I am not a castrate. And,” his voice softened, “I grew to respect and admire her. She was not, precisely, a lovable woman. But I loved her in a way.”

“How did she die?” Elizabeth had been wondering this for a while.

Rede gave her the bare brutal facts, spoken in a level monotone. “She was raped and killed by renegades in the pay of an English company that wanted to destroy my own company. They attacked ten winter stations, and killed everyone they found: men, women, children.”

“Oh, Rede.” Impulsively, she moved closer, and clasped his arm, resting her head on his shoulder. He slid his arm out of hers and instead, put it around her, pulling her tight against his body.

When Rede spoke again, his voice was tight with suppressed emotion. “John and I were out checking the trapping lines. We should have been back when they arrived, but I stopped to investigate a valley that I thought might be a good spot for beavers. We saw the smoke from the fire as we came in. By the time we arrived, the wolves and the hawks…” he broke off.

Elizabeth cuddled as close as she could, trying to give comfort without words.

“We couldn’t stay there; they’d had carried off anything portable and burned or broken the rest. So we cut trees and burned them till we had thawed enough ground to bury my wife and my babies. And then I swore on the grave that I would hunt the killers down and give my family justice.

“We followed them for days. For days, we were too late at house after house. But then we caught up.

“They had become careless, or they were fools, or they were drunk. John and I picked them off one at a time, until only three were left. Then…

“You don’t need to hear about that. We caught them, we questioned them, and we took them into St Johns for the military to deal with them.”

He fell silent again, driving with one hand and holding her against him with the other, her head tucked under his chin.

“So you got justice for your family,” Elizabeth said.

“We got the renegades, but those who paid them? We didn’t have enough information to track them down, and the authorities were not interested. One idiot had the nerve to tell me ‘if you want a half-breed wife, go and get another one.’ ”

Elizabeth was shocked. “How could he say such a thing to a grieving widower!”

“He realised he had been unwise,” Rede commented, and smiled, grimly.

Elizabeth thought of asking what happened to the foolish official, but decided she didn’t want to know.

He bent his head to reach under her bonnet and give her a tender kiss. “Thank you, Elizabeth.”

“For what?”

“For caring. You do care, don’t you?”

Elizabeth wriggled, putting more distance between them.

“I cannot care. We have no future, Rede.”

“Future,” Rede repeated. They crested the hill, and he needed to turn his attention and both hands to the horses, as they shied restively in the sudden wind. Through the drizzly rain, Elizabeth could see the even shapes of the Roman fort groundworks, softened by centuries of weather.

“I cannot promise you a future. I don’t break my promises, and I already have a promise to keep. Until I have given my family justice… I’m close, Elizabeth, but they know I’m after them.”

Elizabeth immediately understood. “The accidents. You think your family’s killers are trying to kill you.”

“I think the people that ordered the murders are behind at least some of the accidents. I think I am unlikely to survive these next few weeks.” He sounded calm, so matter of fact. How could he say such a thing as if he was announcing what he had for dinner last night?

“I cannot promise you a future,” he said again. “But I could give you my name. And I will, if that’s what it will take to get you into my bed. Marry me, Elizabeth. Make me happy in the last weeks of my life.”

Suddenly, she was furious. “How dare you. How dare you offer me a few weeks of your life. You talk about caring, but you would upend my life—yes, and the lives of my family—and then leave us.”

“Think of what you could do for your family as my countess,” he pleaded.

He held the horses tightly in hand, as the road descended rapidly to the river in a series of switchbacks.

“Not your countess. Your widow!”

“Yes. Probably. Elizabeth, I’m being honest with you. I’ve always been honest with you.”

“You do not understand, Rede.”

“You’re right. I don’t understand. Elizabeth, what we could have together is incredible. I don’t understand how you can just ignore it.”

“If it is so incredible, how can you plan to just throw it away? How can I let myself love you if I know I am going to lose you?”

“Love.” She felt him go still beside her, and he was silent for a while, seemingly concentrating on turning the horses onto the approach to the small bridge that connected the north end of the Longford Court estate with the road to Niddberrow.

“You are right,” he said at last. “Loving me would be a mistake. Even if I survive…” He broke off again.

After a time she prompted, “If you survive, what?”

“I have never loved the way you mean the word. Perhaps I could have learned to do so before my family was killed. But for these past years I have lived to destroy their killers. I don’t know if I have room in me for love. I only know that I want you past all reason.”

They were across the river now, and entering the woods that could be seen from the North face of the house.

She wanted to take him in her arms and kiss away the bleak look he wore. But so many reasons held her still. “I am not fit to be your countess. My past…”

He stopped the horses, and set the brake. “I knew George. I have seen Daisy. None of it matters, Elizabeth.”

“There would be gossip.”

Rede was dismissive. “There will be always be gossip. We can ignore it.”

“If you are dead there will be no ‘we’. You cannot expect me to face the ton alone.”

He pushed down the waterproof so that he could take both of her hands. “You cannot hide in Longford forever. What of Kitty? What of Daisy when she comes of age?”

She had no answer.

He stretched his head around to look under her bonnet. “You’re crying.”

“I am angry,” she said, swiping at her cheek with her gloved hand. “Why can you not just let the past go? I do not want you to die, Rede.”

“I made a promise,” he repeated. “And even if I hadn’t… I have to go on, now, Elizabeth. I told you that I’m close. I’ve found the men I’m hunting, and I have the means to bring them down.”

She felt hope, like a warmth rising within her. “Then you will be safe.”

Rede shook his head. “They have a backer; a powerful man who commands them. We need to find out who he is. Until we find him and stop him, we… I won’t be safe.”

Elizabeth was quick to hear what he almost said. “He might go after your family.” It was a statement, not a question.

To his credit, Rede answered her immediately. “I believe he will.”

“That is why you have servants patrolling the grounds, and escorting Kitty and Mia when they go out.”

“It is.”

Elizabeth talked her thoughts out loud as fast as they occurred to her. “Ever since we moved to Longford Court, you have sent escorts with us, too. Even into the grounds. You think he may be after us, too.”

“If he guesses how important you are to me.” Rede followed the words with a deep sigh of resignation. “That finishes it, doesn’t it. You won’t trust me to keep you safe?”

He answered his own question before she could speak. “Of course not. I didn’t keep Marie-Josephe safe, or the children. Why should you trust me?”

Impulsively, she kissed him, a brief peck on the cheek. “If it was only me, Rede… But I cannot risk Daisy. I cannot choose my own wants over the safety of my family.”

Rede turned his face and touched his lips to hers, and then wrapped his arms around Elizabeth to pull her closer. “One more kiss,” he murmured, almost against her mouth, and then their lips touched and her world narrowed and exploded all at the same time. She lost all sense of the woods, the rain, the chaise, the horses. She was aware only of Rede, only of his lips, and tongue, and teeth exploring hers, coaxing her to explore him in turn; only of his hands—one holding her firmly and the other lightly roaming and caressing, setting her body aflame.

Elizabeth did not know how much time passed before he pulled away.

He smiled, ruefully. “They will be expecting us at the house,” he said.

She nodded, unable to speak, still lost in a sensual haze.

“We had better go.”

She nodded again.

“You might want to…” he gestured to her head. She realised that her bonnet was hanging from her neck, and her hair was half down.

Between them, they found enough hair pins to restore some sort of order, and Rede set the horses walking. They did not speak again until he turned into the driveway in front of the Court, where Willie Bush was waiting to hand Rede an umbrella and take the horses.

Then, as they walked up the stairs to the front door, Rede bent down so that his mouth was close to Elizabeth’s ear. “This isn’t over,” he said, as Cole opened the door and they entered to be grabbed by laughing children and ushered upstairs to the party.

October 8, 2014

Image quilts

Someone on Twitter introduced me to Image Quilts, an app for Chrome invented by Edward Tufte, a statistician, to help people visualise data. It captures any images produced by an image search, and then lets you move them around, delete them, introduce others, turn them into black and white, and change their size.

And what beautiful results it makes. Here’s one I produced showing landscape paintings from the Georgian era:

And here’s one of book covers. My search term was “Historical romance cover best seller”.

October 7, 2014

Too many dukes?

Image used in Czechoslovakia for Sabrina Jeffries’ book Only a Duke will Do. And he would, wouldn’t he?

Because I’m trying to write historicals that are historically plausible, I do a lot of research. And one thing I found early on is that the trios (and more) of sexy young or youngish dukes that pop up in some books are just not historically plausible. In 1814, Great Britain had 28 ducal titles, held by 25 people. (Not counting the royal dukedoms given to the sons of the reigning monarch.)

These dukes all tended to marry within the upper peerage. The chances of a herd pack of them descending on an unsuspecting village and carrying off the local dressmaker, the cook, and the retired courtesan were pretty slender.

This doesn’t prevent me from enjoying a good series with more than one gorgeous eligible duke in it. Let’s face it. Dukes are sexy. As this article in the Huffington Post points out:

…duke is shorthand for the type of hero they can expect to read about and the kind of hero readers love: the powerful, alpha male who bows down to no one (except the heroine).

What’s not to love?

But I’m trying to keep my own duke heroes down to an acceptable level. I have none in the current book, but three, all of different ages, over the 50 or so books I have planned.

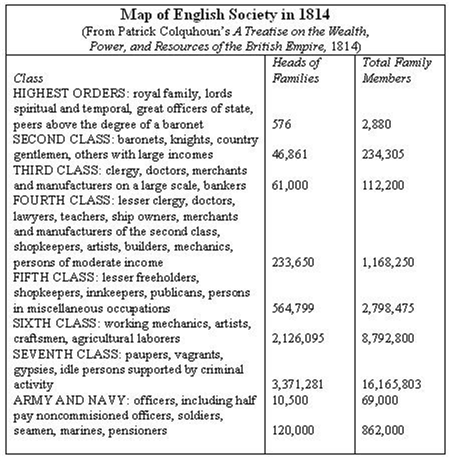

The picture shows a map of society in 1814, and here’s a summary of my research on the nobility at the time.

The picture shows a map of society in 1814, and here’s a summary of my research on the nobility at the time.

Nobility = 2,880 people with 576 heads of family (includes royalty and bishops as well as nobility)

The numbers below do not include secondary titles. The dates mark states of union. Until 1707, England, Ireland and Scotland were separate countries. In 1707, Great Britain was formed through the union of England and Scotland. Between 1707 and 1801, Great Britain and Ireland were separate countries under one ruler. From 1801, the state became the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland – one country. In 1922, the Irish Free State seceded, but that’s outside of our period.

Dukes: 28 titles held by 25 people: Title comes from shire

11 titles in peerage of England to 1707

9 in peerage of Scotland to 1707 (including two doubles with England and one double within Scotland)

7 in peerage of Great Britain and Ireland 1707 to 1801 (6 GB and 1 Irish)

1 in peerage of UK and Ireland 1801 onwards (the Duke of Wellington)

So 17 English, 7 Scots only, 1 Irish duke.

All Dukes are also Marquesses as secondary titles.

Marquesses/Marquises: 32 titles: Titles come from place names, originally border marshes (chiefly with Wales)

1 in peerage of England to 1707

3 in peerage of Scotland to 1707

19 in peerage of Great Britain and Ireland 1707 to 1801 (10 GB and 9 Irish)

9 in peerage of UK and Ireland 1801 onwards (6 UK and 3 Irish)

So 16 English, 3 Scots, and 12 Irish marquesses.

Earls: 210 titles, including 11 doubles – 6 held by women: 70% of titles come from place names and use ‘of’; remaining 30% come from surnames

25 in peerage of England to 1707

41 in peerage of Scotland to 1707 (4 held by women)

12 in peerage of Ireland

97 in peerage of Great Britain and Ireland 1707 to 1801 (38 GB and 59 Irish – 1 of the Irish titles held by a woman)

35 in peerage of UK and Ireland 1801 onwards (24 UK – 1 of which was held by a woman – and 11 Irish)

So 87 English, 41 Scots, and 82 Irish earls.

Viscounts: 66 titles, includes 2 held by women, includes 1 double; ancient title for sherrif – usually the title name is the same as the surname

1 in peerage of England to 1707

2 in peerage of Scotland to 1707 (uses ‘of’)

11 in peerage of Ireland (1 held by a woman)

36 in peerage of Great Britain and Ireland 1707 to 1801 (9 GB and 27 Irish – 1 of the Irish titles held by a woman)

16 in peerage of UK and Ireland 1801 onwards (8 UK and 8 Irish)

So 18 English, 2 Scots, and 46 Irish viscounts.

Barons: 172 titles; title name is usually the same as surname

17 in peerage of England to 1707 (4 held by women) plus 16 vacant

16 in peerage of Scotland to 1707 (1 held by women)

5 in peerage of Ireland

81 in peerage of Great Britain and Ireland 1707 to 1801 (50 GB and 31 Irish)

28 in peerage of UK and Ireland 1801 onwards (23 UK and 5 Irish)

October 5, 2014

Mob football

On Facebook, I’ve just reposted an article by EE Carter about medieval football. Great article, and I love the videao clip (an ad starring David Beckham and friends) that she’s used to illustrate her piece.

I came across a description of mob football when I was researching village Whitsunweek activities for Farewell to Kindness, and I loved the idea. So a football match duly made its way into the novel, giving the villain an opportunity to attempt to kill my hero. (Yes, I know that would be a breach of mob football’s one rule, but he’s a villain, okay?)

Mob football is still played today in several parts of Britain, as shown in the following clip.

October 4, 2014

A profound curtsey

When I first started blogging (in my other life), I came across the acronym H/T. This, I found out, meant hat tip, or a tip of the hat, or thank you very much.

When I first started blogging (in my other life), I came across the acronym H/T. This, I found out, meant hat tip, or a tip of the hat, or thank you very much.

I’d like to H/T Jane Austen’s World, which I’ve already quoted several times in the couple of weeks I’ve been blogging. Under the circumstances, a curtsey seems more appropriate, and I’ll make it a very deep one.

Thank you, Jane Austen. I’ve visited you many times over the past year, and my little OneNote database is full of links to interesting articles about all sorts of things.

For almost anything you want to know about late Georgian and Regency Britain, this list on Jane Austen’s World is a great place to start.

And also try her list of original sources.

October 3, 2014

Dance for your mammy

A country assembly brings a number of my characters into close proximity, so I’ve been reading up on late Georgian dance moves.

A country assembly brings a number of my characters into close proximity, so I’ve been reading up on late Georgian dance moves.

No waltz, of course.By 1807, the waltz had spread out from Germany and was fashionable in Vienna. It didn’t arrive in England until after the start of the Regency proper – the exact date is a little vague, but they were dancing it by 1815 (although as late as 1825, strict moralists frowned at the close position required).

English Historical Fiction Authors, in a post called ‘A Private Ball’ (by Maria Grace) quotes a manual of the day:

“The characteristic of an English country dance is that of gay simplicity. The steps should be few and easy, and the corresponding motion of the arms and body unaffected, modest, and graceful.” – The Mirror of Graces, 1811

She goes on to say:

…most of the ball dances were lively and bouncy. Country dances, the scotch reel, cotillion, quadrille made up most of the dancing.

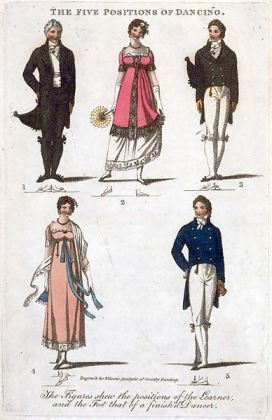

Most dances seem to have been danced in squares or in long lines of couples. As with ballroom dancing today, dancers suited their footwork to their level of skill (if they were wise), but the five positions I learned long ago in ballet classes will come in handy if I ever find myself transported to a regency ballroom.

Regency Dances Org has a list of the basic steps required, and how to do them. They also have a long list of dances, which can be sorted by year of publication. Click on any dance to see an animation showing the figures of the dance. And, under Regency Style, they say:

Regency Dances Org has a list of the basic steps required, and how to do them. They also have a long list of dances, which can be sorted by year of publication. Click on any dance to see an animation showing the figures of the dance. And, under Regency Style, they say:

In his 1815 Essay on Deportment Wilson [Thomas Wilson, the Dance Master at the King's Theatre Opera House] offers advice to dancers. “The following errors are particularly to be avoided:

Making awkward bows

Shuffling and rattling about the feet

Looking at the feet

Bending [sharply] the arm at the elbow, in giving the hand in Dancing

Holding the hands of any person too fast

Bending down the hands of your partner

Bouncing the hands up and down

Bending the body forward.”The dancer should move with a relaxed upright carriage, with the head erect but level. Wilson goes on to say: “To Dance gracefully, every attitude, every movement, must seem rather the effect of accident than design; nothing should seem studied, for whatever seems studied, seems laboured, and every such appearance is absolutely incompatible with any endeavour at a display of graceful ease”.

He also advocates “a graceful elevation of the head”, “an easy sway of the whole frame” and “hands gently raised when presented to join your partners”. “In all movements of the feet, the toes pointed downwards, and in general turned (as much as with ease to the performer they can be) outwards”.

The excellent Regency Dance Org resource is designed for modern balls in the Regency form, but I used it to understand where my characters were when they were dancing at my country assembly. The site doesn’t have the Sir Roger de Coverley or Le Boulanger – or, for that matter, the minuet. The minuet was falling out of use by 1807, but the others were in use right through to the middle of the century.

Here’s the Sir Roger.

And here’s the minuet.

In Bath, the minuet was danced by single couples from six until eight, followed by country dances, according to austenonly.com. But in other provincial towns it was seldom danced.

The link above is to the second of a brilliant four-part series on Georgian assemblies, as is the next quote.

Interestingly the summer was the most important time for assemblies in the provincial towns. They were larger and more prestigious, and often coincided with important local events such as fairs, the assizes or races week in the towns. The assizes was the time in the year when the Circuit judges appeared in town to hear locally important civil and criminal trials and they were a time of much entertaining and ceremony. The same held with any local horse racing meeting( without the pomp of the judges’ processions etc).

October 2, 2014

Nothing is inconsequential

Elizabeth Boyle writes on synchronicity in the writing process; something I’m experiencing every day as I write Farewell to Kindness, and pieces go ‘click’.

Elizabeth Boyle writes on synchronicity in the writing process; something I’m experiencing every day as I write Farewell to Kindness, and pieces go ‘click’.

…in writing, it is often a sort of synchronicity of pieces: a treasure exhibit, a line from a biography, and a literature degree that left me with a profound love of myths. None of them are truly connected, but they all came together for this story. I have come to believe that nothing in life is inconsequential. It all has value eventually. Just keep your eyes and imagination open.

At last, my jackdaw mind is finding a use for all those shiny facts and snippets.

October 1, 2014

So many resources, so little time

“I have to organise my research and my plots and my characters,” I said to my personal romantic hero over the Christmas break. “I need a database. I need to be able to keep all the resources where I can reach them.”

So off he went, like the hero he is, on a quest to find a simple tool that would do what I want.

The answer proved to be OneNote on the PC, linked via the ether with Outline on my IPad. Now I always know who lives at Dennings farm and what the head groom at Longford Court looks like. And the phases of the moon and weather in my part of England during May and June 1807.

September 29, 2014

The problem with pedantry

My hero and heroine being invited to dinner, I set out to confirm what I knew about seating etiquette at a formal Georgian dinner. I’ve read heaps of novels in which the dinner guests process couple by couple into the room in order of precedence, and are seated male, female, male, around the table. But I wanted to get it right.

My hero and heroine being invited to dinner, I set out to confirm what I knew about seating etiquette at a formal Georgian dinner. I’ve read heaps of novels in which the dinner guests process couple by couple into the room in order of precedence, and are seated male, female, male, around the table. But I wanted to get it right.

Turns out that it isn’t that simple. Jane Austin’s world tells me that, in 1791, the etiquette was quite different.

When dinner is announced, the mistress of the house requests the lady first in rank, in company, to shew the way to the rest, and walk first into the room where the table is served; she then asks the second in precedience to follow, and after all the ladies are passed, she brings up the rear herself. The master of the house does the same with the gentlemen. Among the persons of real distinction, this marhalling of the company is unnecessary, every woman and every man present knows his rank and precedence, and takes the lead, without any direction from the mistress or the master.

When they enter the dining-room, each takes his place in the same order; the mistress of the table sits at the upper-end, those of superior rank next [to] her, right and left, those next in rank following, the gentlemen, and the master at the lower-end; and nothing is considered as a greater mark of ill-breeding, than for a person to interrup this order, or seat himself higher than he ought. –John Trusler, 1791

A further quote from the same book says that:

Custom, however, has lately introduced a new mode of seating. A gentleman and a lady fitting alternately round the table, and this, for the better convenience of a lady’s being attended to, and served by the gentleman next to her. But notwithstanding this promiscuous seating, the ladies, whether above or below, are to be served in order, according to their rank or age, and after them the gentlemen, in the same manner. – John Trusler, p 6

Austenised has these rules, culled from Georgette Heyer’s Regency World, by Jennifer Kloester.

When going in to dinner, the man of the house always escorted the highest-ranking lady present. The remaining dinner guests also paired up and entered the dining room in order of rank.

Dinner guests were seated according to rank, with the highest-ranking lady sitting on the right-hand side of the host, who always sat at the head of the table.

When dining informally it was acceptable to talk across or round the table.

At a formal dinner one did not talk across the dinner table but confined conversation to those on one’s left and right.

Ladies were expected to retire to the withdrawing room after dinner, leaving the men to their port and their ‘male’ talk.

A hostess should never give the signal to rise from the table until everyone at the table had finished.

I’m not sure that these would apply in 1807, though. I found a lovely post on Georgian eating, which gave the same message as Trusler – ladies on one side, and gents on the other.

A call for help on Goodreads led me to the wonderful English Historical Fiction Authors, and the post by MM Bennetts, which told me about late Georgian servings, but not about 1807 seating.

A second post on the same site. this one by Maria Grace, gave me more details about how the courses were served and what they might comprise.

The truth is out there, but perhaps I should just send my characters on a picnic!