Jude Knight's Blog, page 162

October 23, 2014

Finished by mid-November?

Today on the train on the way to work I passed the 116,000 mark. One month ago to the day, I posted to say I’d written 60,000 words. Looking back, I wrote 30,000 in the first three months, 30,000 in the fourth month, and 56,000 in this latest month. In part, I’m getting faster as I become more confident. In part, I’ve stopped putting down the novel to research every little fact. In part, it’s the new iPad, which makes it easy to sit up in bed at 1am and type another scene. And in largest part of all, its my personal romantic hero (aka the PRH), who keeps me fed and supplied with endless cups of coffee in the morning and tea in the afternoon (and a glass or two of wine in the evening). Love you, darling.

Today on the train on the way to work I passed the 116,000 mark. One month ago to the day, I posted to say I’d written 60,000 words. Looking back, I wrote 30,000 in the first three months, 30,000 in the fourth month, and 56,000 in this latest month. In part, I’m getting faster as I become more confident. In part, I’ve stopped putting down the novel to research every little fact. In part, it’s the new iPad, which makes it easy to sit up in bed at 1am and type another scene. And in largest part of all, its my personal romantic hero (aka the PRH), who keeps me fed and supplied with endless cups of coffee in the morning and tea in the afternoon (and a glass or two of wine in the evening). Love you, darling.

I still have 11 scenes and probably six or seven chapters to go. Boy, am I going to have to cut when I edit! I’ll have around 130,000 to 140,000 words, and I’ll need to trim back to 100,000.

October 22, 2014

Books I must have

This is my ‘to buy’ list. Not the only books I want to get before the end of December, but the ones I’ve been waiting for the writers to publish. The date is the release date. Must. Finish. First. Draft.

A Notorious Ruin: Sinclair Sisters

Carolyn Jewel

23 September 2014

The Governess Club: Louisa

Ellie Macdonald

7 October 2014

What a Lady needs for Christmas

Grace Burrowes

7 October 2014

The Counterfeit Heiress

Tasha Alexander

14 October 2014

Untitled rhymes with love novella

Elizabeth Boyle

15 October 2014

Darling beast

Elizabeth Hoyt

28 October 2014

The Viscount who lived down the lane

Elizabeth Boyle

28 October 2014

By Winter’s Light

Stephanie Laurens

28 October 2014

Only enchanting

Mary Balogh

28 October 2014

The shocking secret of a guest at the wedding

Victoria Alexander

4 November 2014

When sparks fly

Sabrina Jeffries

17 November 2014

Never judge a lady by her cover

Sarah MacLean

25 November 2014

An improper arrangement

Kasey Michaels

25 November 2014

Tall, dark, and royal

Vanessa Kelly

25 November 2014

Never judge a lady by her cover

Sarah MacLean

25 November 2014

Silver deceptions

Sabrina Jeffries

30 December 2014

Four nights with the Duke

Eloisa James

31 December 2014

Say yes to the Marquess

Tessa Dare

31 December 2014

October 21, 2014

Ewww, just ewww: or the cautionary tale of the perils of naming characters in a whole lot of books at once and then starting one without reference to the real world

The heroine also known as Anne

Let me start by saying I didn’t do it on purpose.

It’s like this. In the past two years, I’ve created more than 50 plots, detailing more than 30 of them. For most of the plots, the hero and heroine, and a few of the key secondary characters, have names, personal histories, and characters. I’ve also researched my period extensively. And since I’m a tad obsessive, that means a database, charts, sketches, photos, tables, and spreadsheets. Lots of spreadsheets.

When it comes to forenames, I’ve got two tables showing the most popular names in late Georgian England (one for male and one for female names), a spreadsheet of allocated names and titles, a list of possible other character names… okay, maybe more than a tad.

Now I come from a large family, and my own children have made an extensive contribution to the numbers. And we tend to pick traditional names for our babies. Perhaps you can see where this is going.

I eventually twigged that my research and planning was another way to practice avoidance. So I picked the first story in time – the one that happened in 1807, and began to write.

It didn’t even occur to me that the heroine having the same name as one of my granddaughters might be an issue. They were two different people who just happened to have the same name.

The thing is, this is my first book. I hope to be published in April, and – all going well – people will actually read it.

And my granddaughter, who I adore, whose umbilicus I cut 14 years ago, who I helped raise through her early childhood; my granddaughter had the same name as the heroine.

And on Monday I finally reached the hot scene.

Up till now, they’ve been attracted, there have been a couple of close calls and some fairly steamy kisses. But now I had them stranded for the night, alone, in a cottage far from everyone they knew.

And as the hero and heroine began to explore the possibilities that this opened, I began to experience dissonance. Each time the hero said her name in a voice growing huskier and huskier with passion, my dissonance grew.

I know, right?

It was creepy. and I don’t mean Halloween creepy. I mean scruffy man on the corner in nothing but a raincoat creepy.

Ewww. Just. Ewww.

So, thanks to search and replace, my heroine is now called Anne. She always has been called Anne. She always will be called Anne. And when Rede whispers endearments to her in the intimacy of the quiet cottage, he whispers a name that doesn’t belong to any of my granddaughters.

I don’t promise that I will never have a heroine up to steamy stuff who happens to have the same name as one of my nearest and dearest. But it won’t be my first book. And the person won’t be a teenager.

Okay, Debs?

October 20, 2014

Secrets, passion, and a nasty villain or two

Lady Beauchamp’s Proposal, by Amy Rose Bennett, had me from the first page. The author beautifully captures Beth’s desperate courage, and when her sleazy husband enters (on the next page) the atmosphere ratchets up another notch.

Lady Beauchamp’s Proposal, by Amy Rose Bennett, had me from the first page. The author beautifully captures Beth’s desperate courage, and when her sleazy husband enters (on the next page) the atmosphere ratchets up another notch.

Elizabeth is the neglected and ignored wife of the dissolute Lord Beauchamp. When she escaped from him before he can infect her with syphilis, she runs as far as she can, applying for a job as governess in a remote castle in Scotland. There, she meets James, the Marquess of Rothsburgh, and the attraction between them is immediate.

Both James and Beth are decent people, tormented by the events of their pasts, guilty about their growing attraction, and troubled by self-doubt. It isn’t hard to care about what happens to them. As the author turns up the heat on their sensual awareness of one another, we want them to be together despite the fact that Beth is still married.

In those days marriage really was till death. That Beth’s husband is a selfish, hedonistic rat oozing a particularly nasty infection doesn’t change his legal rights to insist on keeping his wife. Beth and James can’t see any path to a happy ending except to wait, perhaps for years, and the last chapters turn the gothic screws tighter still, with Beth facing something worse than she can imagine (no spoilers – you’ll have to read it for yourself).

I loved this book, and I found the ending very satisfying.

I have two tiny niggles.

One is the speed of the ending – ten months passes between the end of one chapter and the end of the book. It worked, but it seemed rushed to me. I’d have at least liked to see a scene played out between Beth and the two sleazes, where they make their threats to her, rather than just hear about them later when she is thinking over what they said.

The other is a continuity problem; early in the book, we’re told that Beth heard about the governess job a month before the day she arrives at the castle. The person she hears talking about the job mentions that the Marquis is a recent widower. More than a fortnight after she arrives – so close to seven weeks after someone in London mentioned the death, the Marquis tells Beth his wife has been dead for eight weeks. So how did the news arrive in London so fast?

As I say; tiny.

I still loved the book. I recommend it, and I’ll be looking forward to seeing more from Amy Rose Bennett.

October 18, 2014

The sum total of human happiness is one minus part of my neighbour’s sorrow

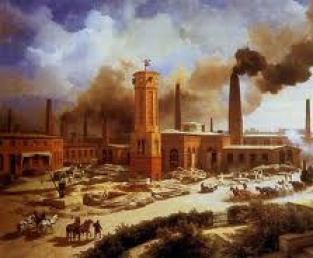

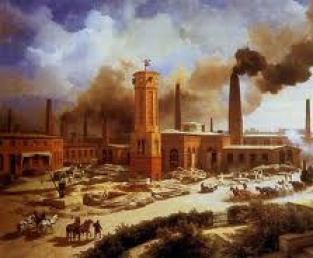

One of the reasons I love learning about the Georgian era is that I find so many parallels to our own time. It was a time of rapid change, not just because of the industrial revolution, but because of the ideas that were beginning to gain foothold: ideas about individual human rights, about economic theory and the use of capital, about class and religion. It was a time of great and growing rifts between the rich and the poor, and of sudden changes in the ways that people lived. It was, of course, a time when ideas became manifest in a raft of inventions – from gas lighting to better road surfacing to flushing indoor toilets. It was a watershed time, when the old ways lingered side by side with thinking that is recognisably modern.

One of the reasons I love learning about the Georgian era is that I find so many parallels to our own time. It was a time of rapid change, not just because of the industrial revolution, but because of the ideas that were beginning to gain foothold: ideas about individual human rights, about economic theory and the use of capital, about class and religion. It was a time of great and growing rifts between the rich and the poor, and of sudden changes in the ways that people lived. It was, of course, a time when ideas became manifest in a raft of inventions – from gas lighting to better road surfacing to flushing indoor toilets. It was a watershed time, when the old ways lingered side by side with thinking that is recognisably modern.

Today, we teeter on the brink of another great sea change in human thinking and endeavour, and the direction we may travel is by no means clear. Perhaps, by thinking about the past, we can be clearer about the present?

Thanks to a conversation on Goodreads, I’ve been thinking about the differences between standard of living and quality of living, and whether we can fairly say that our standard of living is better than that of past eras. The problem lies with what we mean by ‘our’ and who we’re comparing ourselves to in past eras.

Are we comparing a top movie or sports star with the peasant of Medieval Germancy? Or a shanty-town dweller in Rio de Janeiro with the very rich of Georgian England? Either would be a nonsense, of course. But it is common enough to compare the average middle-class Westerner with a slum dweller from the worst cribs in St Giles, the poorest part of Georgian London.

If we want to compare apples with apples, we can. According to some economic historians, around 80% of the world’s population lived in poverty in 1820. According to OECD figures, around 80% of the world’s population lives on less than $10 a day today. So not much change then.

We tend to think of the great poverty that Hogarth drew and Dickens wrote about as indicative of how things were since time immemorial. But as I began this post by saying, Georgian England was a society in transition, and the number of people who suffered from extreme poverty was one of the consequences.

In 18th and 19th century England, enclosure had a massive impact on ordinary working people. Before enclosure, the average farm labourer had little money but access to game, grazing for their cows, gleaning in the landlord’s fields, a pig and some chickens on the common, maybe a few vegetables also on common ground, and so on. None of this showed in the broader economic statistics, but it meant that life was liveable, even comfortable (by the standards of the time).

After enclosure, they had lost everything but the bit of money, and many of them lost that as well. They moved to town to work in factories or the like, and they may have shown up in the economic statistics, but they certainly weren’t comfortable.

All his auxiliary resources had been taken from him, and he was now a wage earner and nothing more. Enclosure had robbed him of the strip that he tilled, of the cow that he kept on the village pasture, of the fuel that he picked up in the woods, and of the turf that he tore from the common. And while a social revolution had swept away his possessions, an industrial revolution had swept away his family’s earnings. To families living on the scale of the village poor, each of these losses was a crippling blow, and the total effect of the changes was to destroy their economic independence. [The Village Labourer, 1760-1832: A Study in the Government of England before the Reform Bill, by J.L. and Barbara Hammond]

To give you an idea of the extent of the change, here’s a summary of the number of Acts of enclosure, and number of acres enclosed, in England over a 100 year period.

Common Field and

some waste

Waste only

Years

Acts

Acreage

Acts

Acreage

1750-1760

152

237,845

56

74,518

1761-1801

1,479 2

428,721

521

752,150

1802-1844

1,075

1,610,302

808

939,043

Total

2,706

4,276,868

1,385

1,765,711

The logic behind enclosure was improving the efficiency of the land. Which it certainly did. After enclosure, those who had benefited from land ownership certainly got richer.

The lives of the judges, the landlords, the parsons, and the rest of the governing class were not become more meagre but more spacious in the last fifty years. During that period many of the great palaces of the English nobility had been built, noble libraries had been collected, and famous galleries had grown up, wing upon wing. The agricultural labourers whose fathers had eaten meat, bacon, cheese, and vegetables were living on bread and potatoes. They had lost their gardens, they had ceased to brew their beer in their cottages. In their work they had no sense of ownership or interest. They no longer ‘sauntered after cattle’ on the open common, and at twilight they no longer ‘played down the setting sun;’ the games had almost disappeared from the English tillage, their wives and children were starting before their eyes, their homes were more squalid, and the philosophy of the hour taught the upper classes that to mend a window or to put in a brick to shield the cottage from damp or wind was to increase the ultimate miseries of the poor. The sense of sympathy and comradeship, which had been mixed with rude and unskilful government, in the old village had been destroyed in the bitter days of want and distress. Degrading and repulsive work was invented for those whom the farmer would not or could not employ. [ibid.]

We can see the results in statistics such as Dan Cruikshank‘s suggestion that 1 in 5 women in London made their living from the sex trade.

In the words of those in favour of enclosures, am I alone in hearing some of today’s economists? (No, I’m not.)

Not is it a consequence that there must be depopulation, because men are not seen wasting their labour in the open field…. If, by converting the little farmers into a body of men who must work for others, more labour is produced, it is an advantage which the nation should wish for … the produce being greater when their joint labours are employed on one farm, there will be a surplus for manufactures, and by this means manufactures, one of the mines of the nation, will increase, in proportion to the quantity of corn produced. [An Inquiry into the Connexion between the Present Price of Provisions, &c, John Arbuthnot of Mitcham, 1773]

And views about the poor seem also to have travelled well.

Everyone but an idiot knows that the lower classes must be kept poor or they will never be industrious. [Arthur Young, 1771]

The title of this post is based on two related concepts. One is that happiness, being a feeling, is not additive. Long ago, in another forum, I wrote about the sum total of human misery.

What is the sum total of human suffering? A stupid cliché, that’s what.

It implies that human suffering – or, for that matter, any other human experience – is additive; that if a whole heap of people are, for example, all bereaved simultaneously, then the experience is somehow worse than if only one is bereaved.

I might, if I am miserable, cause you to suffer in some way, if you feel sorry for me, or if I lash out in my misery to make you suffer too. But my misery remains my own; it isn’t added to yours.

Furthermore, suffering is time-bound. I might remember a past pain or anticipate a coming pain. But what I suffer in my present is the memory or the anticipation, not the pain. If you think you can accurately remember or anticipate pain, just think about a painful experience you’ve had, then repeat it. You’ll find the actuality is quantitatively and qualitatively different. (It may be lesser or greater; but it will be different.)

So the sum total of human suffering is the maximum amount that any one person can suffer at any one time.

And the same applies to human happiness. The sum total of human happiness is the amount of happiness that one person can feel.

The second concept is that – for normal, non-sociopathic people who feel empathy – the misery of others decreases happiness. If we know about the suffering of others and can help, we should. We cannot be fully happy until everyone else is, too. Even on a very pragmatic and selfish level, ignoring the suffering of others is stupid, as French aristocrats discovered in the late 18th century – and there have been many other examples before or since. Read Morris West’s Children of the Sun for a chilling and prescient forecast of the consequences of ignoring the plight of children in post-WWII Italy, as just one example.

So, while I’m still not equating standard of living and quality of life, if one person in the world is too poor to be able to enjoy life, the happiness of each other individual is a little diminished.

When I write about late-Georgian life, I want – first and foremost – to tell a good story. I want my readers to care about the love story of my characters, and to cheer them on to a happy ending. But I also want to do this against the background of a world with eerie similarities to our own.

The sum total of human happiness is one minus my neighbour

One of the reasons I love learning about the Georgian era is that I find so many parallels to our own time. It was a time of rapid change, not just because of the industrial revolution, but because of the ideas that were beginning to gain foothold: ideas about individual human rights, about economic theory and the use of capital, about class and religion. It was a time of great and growing rifts between the rich and the poor, and of sudden changes in the ways that people lived. It was, of course, a time when ideas became manifest in a raft of inventions – from gas lighting to better road surfacing to flushing indoor toilets. It was a watershed time, when the old ways lingered side by side with thinking that is recognisably modern.

One of the reasons I love learning about the Georgian era is that I find so many parallels to our own time. It was a time of rapid change, not just because of the industrial revolution, but because of the ideas that were beginning to gain foothold: ideas about individual human rights, about economic theory and the use of capital, about class and religion. It was a time of great and growing rifts between the rich and the poor, and of sudden changes in the ways that people lived. It was, of course, a time when ideas became manifest in a raft of inventions – from gas lighting to better road surfacing to flushing indoor toilets. It was a watershed time, when the old ways lingered side by side with thinking that is recognisably modern.

Today, we teeter on the brink of another great sea change in human thinking and endeavour, and the direction we may travel is by no means clear. Perhaps, by thinking about the past, we can be clearer about the present?

Thanks to a conversation on Goodreads, I’ve been thinking about the differences between standard of living and quality of living, and whether we can fairly say that our standard of living is better than that of past eras. The problem lies with what we mean by ‘our’ and who we’re comparing ourselves to in past eras.

Are we comparing a top movie or sports star with the peasant of Medieval Germancy? Or a shanty-town dweller in Rio de Janeiro with the very rich of Georgian England? Either would be a nonsense, of course. But it is common enough to compare the average middle-class Westerner with a slum dweller from the worst cribs in St Giles, the poorest part of Georgian London.

If we want to compare apples with apples, we can. According to some economic historians, around 80% of the world’s population lived in poverty in 1820. According to OECD figures, around 80% of the world’s population lives on less than $10 a day today. So not much change then.

We tend to think of the great poverty that Hogarth drew and Dickens wrote about as indicative of how things were since time immemorial. But as I began this post by saying, Georgian England was a society in transition, and the number of people who suffered from extreme poverty was one of the consequences.

In 18th and 19th century England, enclosure had a massive impact on ordinary working people. Before enclosure, the average farm labourer had little money but access to game, grazing for their cows, gleaning in the landlord’s fields, a pig and some chickens on the common, maybe a few vegetables also on common ground, and so on. None of this showed in the broader economic statistics, but it meant that life was liveable, even comfortable (by the standards of the time).

After enclosure, they had lost everything but the bit of money, and many of them lost that as well. They moved to town to work in factories or the like, and they may have shown up in the economic statistics, but they certainly weren’t comfortable.

All his auxiliary resources had been taken from him, and he was now a wage earner and nothing more. Enclosure had robbed him of the strip that he tilled, of the cow that he kept on the village pasture, of the fuel that he picked up in the woods, and of the turf that he tore from the common. And while a social revolution had swept away his possessions, an industrial revolution had swept away his family’s earnings. To families living on the scale of the village poor, each of these losses was a crippling blow, and the total effect of the changes was to destroy their economic independence. [The Village Labourer, 1760-1832: A Study in the Government of England before the Reform Bill, by J.L. and Barbara Hammond]

To give you an idea of the extent of the change, here’s a summary of the number of Acts of enclosure, and number of acres enclosed, in England over a 100 year period.

Common Field and

some waste

Waste only

Years

Acts

Acreage

Acts

Acreage

1750-1760

152

237,845

56

74,518

1761-1801

1,479 2

428,721

521

752,150

1802-1844

1,075

1,610,302

808

939,043

Total

2,706

4,276,868

1,385

1,765,711

The logic behind enclosure was improving the efficiency of the land. Which it certainly did. After enclosure, those who had benefited from land ownership certainly got richer.

The lives of the judges, the landlords, the parsons, and the rest of the governing class were not become more meagre but more spacious in the last fifty years. During that period many of the great palaces of the English nobility had been built, noble libraries had been collected, and famous galleries had grown up, wing upon wing. The agricultural labourers whose fathers had eaten meat, bacon, cheese, and vegetables were living on bread and potatoes. They had lost their gardens, they had ceased to brew their beer in their cottages. In their work they had no sense of ownership or interest. They no longer ‘sauntered after cattle’ on the open common, and at twilight they no longer ‘played down the setting sun;’ the games had almost disappeared from the English tillage, their wives and children were starting before their eyes, their homes were more squalid, and the philosophy of the hour taught the upper classes that to mend a window or to put in a brick to shield the cottage from damp or wind was to increase the ultimate miseries of the poor. The sense of sympathy and comradeship, which had been mixed with rude and unskilful government, in the old village had been destroyed in the bitter days of want and distress. Degrading and repulsive work was invented for those whom the farmer would not or could not employ. [ibid.]

We can see the results in statistics such as Dan Cruikshank‘s suggestion that 1 in 5 women in London made their living from the sex trade.

In the words of those in favour of enclosures, am I alone in hearing some of today’s economists? (No, I’m not.)

Not is it a consequence that there must be depopulation, because men are not seen wasting their labour in the open field…. If, by converting the little farmers into a body of men who must work for others, more labour is produced, it is an advantage which the nation should wish for … the produce being greater when their joint labours are employed on one farm, there will be a surplus for manufactures, and by this means manufactures, one of the mines of the nation, will increase, in proportion to the quantity of corn produced. [An Inquiry into the Connexion between the Present Price of Provisions, &c, John Arbuthnot of Mitcham, 1773]

And views about the poor seem also to have travelled well.

Everyone but an idiot knows that the lower classes must be kept poor or they will never be industrious. [Arthur Young, 1771]

The title of this post is based on two related concepts. One is that happiness, being a feeling, is not additive. Long ago, in another forum, I wrote about the sum total of human misery.

What is the sum total of human suffering? A stupid cliché, that’s what.

It implies that human suffering – or, for that matter, any other human experience – is additive; that if a whole heap of people are, for example, all bereaved simultaneously, then the experience is somehow worse than if only one is bereaved.

I might, if I am miserable, cause you to suffer in some way, if you feel sorry for me, or if I lash out in my misery to make you suffer too. But my misery remains my own; it isn’t added to yours.

Furthermore, suffering is time-bound. I might remember a past pain or anticipate a coming pain. But what I suffer in my present is the memory or the anticipation, not the pain. If you think you can accurately remember or anticipate pain, just think about a painful experience you’ve had, then repeat it. You’ll find the actuality is quantitatively and qualitatively different. (It may be lesser or greater; but it will be different.)

So the sum total of human suffering is the maximum amount that any one person can suffer at any one time.

And the same applies to human happiness. The sum total of human happiness is the amount of happiness that one person can feel.

The second concept is that – for normal, non-sociopathic people who feel empathy – the misery of others decreases happiness. If we know about the suffering of others and can help, we should. We cannot be fully happy until everyone else is, too. Even on a very pragmatic and selfish level, ignoring the suffering of others is stupid, as French aristocrats discovered in the late 18th century – and there have been many other examples before or since. Read Morris West’s Children of the Sun for a chilling and prescient forecast of the consequences of ignoring the plight of children in post-WWII Italy, as just one example.

So, while I’m still not equating standard of living and quality of life, if one person in the world is too poor to be able to enjoy life, the happiness of each other individual is a little diminished.

When I write about late-Georgian life, I want – first and foremost – to tell a good story. I want my readers to care about the love story of my characters, and to cheer them on to a happy ending. But I also want to do this against the background of a world with eerie similarities to our own.

October 16, 2014

Criminal injustice

I’ve been researching the justice system of the late 18th and early 19th century, It’s a fascinating period – a time of change in attitudes to crime and legal remedies for crime, as in so much else.

Our modern view is that one law should apply to all. It doesn’t always work. Money buys better lawyers, for a start. But the basic principle is that we have laws that lay down the crime and the range of punishments, and judges who look at the circumstances and apply penalties without fear or favour.

The pre-19th century situation in England was far, far different.

The pre-19th century situation in England was far, far different.

One of the major plot lines in Farewell to Kindness is the hero’s hunt for his family’s killers. In the course of the book, I reach a point where I want to get some of the minor players out of the way, and I hit on the idea of having them caught with contraband goods, arrested, and incarcerated.

I figured they’d be ripe for a little bit of pressure to make them give up some information about the real villain.

Ooops. 21st century blinkers on.

While my characters were having some money troubles (caused by my hero working behind the scenes), they were still wealthy merchants with powerful connections. And even poor peasants, as long as they had influence behind them (such as the local squire) could often slide gently out from under the attentions of the law in the system as it was then. Wealthy merchants? No problem.

So when the Excise or Customs officers (or maybe both) and the local representatives of the law (probably retainers of the local Justice of the Peace, but possibly part-time or full-time night watchmen appointed by the local City Council – no central police force yet) turned up at the door, the conversation would have gone something like this:

“What do you lot want? I’m about to have my dinner.”

“Now look here, Mr XX. Your warehouse down on the wharf is full of stolen and smuggled goods.”

“My goodness, I wonder how that happened.”

“You knew all about it. We have evidence, and a deposition from a real Earl. And we have to listen to real Earls, because they’re important.”

“Bother. You’ve got me there.”

“Yes, it’s a fair cop. So consider yourself arrested.”

“Really? How about if I just give you the goods?”

“Excellent idea. The sale of those goods should fetch a pretty penny.”

“I’ll even loan you a cart to take it all away.”

“Thank you, Mr XX. Have a nice dinner.”

Here’s a neat summary of the way the system worked. Here’s part of what the writer says about the change that was happening.

The key issue was the transition from (to use Foucault’s distinction) sovereignty to government: from a world in which crime was simply a wrong, a personal interaction between individuals or individuals and their superiors, to one in which crime was disruption, in which an offence against the criminal law was a disruption of the public peace and of the effective working of society. This meant a shift from the centrality of the court (as the place where disputants would confront one another) with no implications for the working of society, to the centrality of police and crime detection (as minimising disruption to the working of society).

To the mind of the law enforcers of the time I’m writing about, contraband goods offended those from whom the goods were stolen, and repaying those people (with smuggled goods, the offence was against the King) set the balance right. And if a little of the payment stuck to the hands of those enforcing the law, that was only fair, since they’d done the work.

So I need to go back to those scenes and rewrite them. But I have an idea!

October 14, 2014

All the news you can use

Here’s another great author resource for those with stories set in in the United Kingdom (or anywhere United Kingdom newspapers had correspondents) in the 250 years between 1710 and 1959. The British Newspaper Archive is scanning the British Library’s collection of newspapers. The goal is 40 milli0n pages, and they’re not quite quarter of the way through, but they already have 237 titles from all parts of the UK and Ireland, and from the entire time period.

Here’s another great author resource for those with stories set in in the United Kingdom (or anywhere United Kingdom newspapers had correspondents) in the 250 years between 1710 and 1959. The British Newspaper Archive is scanning the British Library’s collection of newspapers. The goal is 40 milli0n pages, and they’re not quite quarter of the way through, but they already have 237 titles from all parts of the UK and Ireland, and from the entire time period.

For a payment (a one off payment for 40 pages in 365 days, or as many pages as you can devour on a monthly or annual subscription), you can search hundreds of millions of articles by keyword, name, location, date or title, and get the results and then the page where the article appears on your screen in an instant.

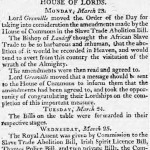

I haven’t subscribed yet, but it’s in next month’s budget. Leaf through their blog to see some great examples of stories (and newspaper pages), and of how people are using the resource. (The image to the right – of a page reporting the success of the Slave Trade Bill – was taken from their blog. Click on it to make it large enough to read.)

October 13, 2014

Let’s roll them! – a history of chairs for invalids

Wheels on chairs for invalids go back a very long way. We have documentary evidence of them in a Chinese print reliably dated to AD525, but human ingenuity quite possibly put chairs and wheels together long before that.

It’s likely, though, that only the rich had such chairs. Certainly, once wheeled chairs for invalids begin to regularly pop up in the documentary record, the posteriors seated in them belonged to the rich and the noble.

In 1595, King Philip II of Spain was sketched sitting in a reclining chair with wheels on each leg. It was clunky and heavy, and he needed to be pushed around by a servant, but – hey – king, right?

In 1595, King Philip II of Spain was sketched sitting in a reclining chair with wheels on each leg. It was clunky and heavy, and he needed to be pushed around by a servant, but – hey – king, right?

Self-propelling chairs arrived remarkably quickly after that, unsurprisingly developed by someone who was himself in need of a chair. In 1655, Stephen Farfler, a paraplegic watchmaker, moved himself around in a chair with three wheels. He moved around by turning handles that worked on the geared front wheel.

Most of the sites I looked at when researching wheelchairs jump from Farfler to John Dawson of Bath. But wheelchairs – both ordinary chairs with wheels and more advanced chairs designed specifically to have wheels – continued right through.

Most of the sites I looked at when researching wheelchairs jump from Farfler to John Dawson of Bath. But wheelchairs – both ordinary chairs with wheels and more advanced chairs designed specifically to have wheels – continued right through.

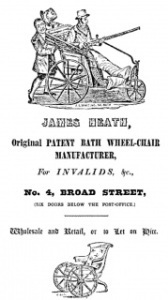

And, in any case, the Bath chair was invented around 1750 by James Heath. Bath was becoming popular as a spa town, but it was not designed to easily get around in a carriage, and ordinary wheelchairs really only worked well on a flat surface such as inside the house.

The Bath Chair was designed to take invalids out and about; primarily down to the Roman Baths for the treatment, and then back home again. Until then, invalids used the sedan chair, which required two attendants to carry. The Bath Chair just needed one person at the back pushing. Furthermore, the occupant of the chair had the steering stick and could therefore directly control the direction of travel. I can see that would be appealing to the average wealthy dowager!

You can see from the advertisement that Heath also sold wheelchairs. The example shown appears to have wheels at the front and stabilising legs at the rear, so no doubt the attendant lifted slightly when he pushed.

But the self-propelling chair had not gone away. John Joseph Merlin, a Belgian inventor and watchmaker (and, perhaps not incidentally the inventor of the in-line skate) created a successful chair that became the model for others. Keith Armstrong, in A very short history of the bicycle and wheelchair, says:

In the mid 1770’s he invented roller-skates and presented his new creation by arriving at a London party playing his violin whilst gliding around the room. Merlin received rapacious applause and an encore, the party-goers demanded that he repeated his act, during the second attempt, he quickly discovered that he didn’t known how to stop and he had a major accident. The next we read about him is of the invention of a new type of self-propelled wheelchair… His design was so successful that 120 years later, a London catalogue of medical equipment was able to boast nine different ‘Merlin’ wheelchairs available on their books. Merlin died in 1803.

As far as I can tell, the Merlin chair had small handles on its arms. But the name ‘Merlin chair’ was retained for later chairs where the occupant was able to turn the large rear wheels to get around, and – by the late 19th century – the smaller propelling wheel had arrived, to help people keep their hands clean.

Meanwhile, back at the end of the 18th century, let’s not forget John Dawson. The most prominent Bath chair maker of his time, his chairs outsold everyone else’s. Since, by all accounts, they were not very comfortable, we must assume that the others were worse!

There’s still a long way to go till we get to the sort of chair I’ve shown below, but the rest of the journey can wait for another post.

Letting the imagination free wheel

Some of my friends have said “Where do you get your ideas?” No doubt it differs from writer to writer, but if you’re interested in the way my mind works, here’s an example.

Some of my friends have said “Where do you get your ideas?” No doubt it differs from writer to writer, but if you’re interested in the way my mind works, here’s an example.

I’ve found that not writing on my novel on Sunday is having unexpected side effects. My imagination, which continues producing plot lines and snippets of dialogue, goes off at tangents while I’m paying attention to 2014. Snarls in Farewell to Kindness untangle themselves. New ideas for the next three books slip into those evolving plots. And whole new sets of characters and story ideas beg for a wee bit of brain time.

The weekend before last, two characters with cameo spots in Farewell to Kindness demanded their own story.And they’re going to get it. Look before Christmas for a free short story or novella (not sure yet) about how Viscount Avery (also known as Candle because he is tall and thin and has red hair) meets Minerva Bradshaw, who makes wheeled chairs for invalids.

The first seeds were planted when I was populating the village where Elizabeth, my heroine, lives. I had a block of land in behind the row of workers’ cottages that Elizabeth and her family live in. I decided to make it one estate; a comfortable gentleman’s detached house and garden belonging to a retired manufactory owner, called Bradshaw.

But why would the Bradshaws move to a tiny village on the edge of the Cotswolds? I decided that they wanted to be nearer to their daughter, who had married a peer. And, because he was a peer, they didn’t want to be too close, in case they embarrassed the Viscount and his new wife. The manufacturer’s daughter, Lady Avery, was now waiting in the wings, ready for her entrance.

A couple of months later, my hero and heroine went to an assembly in a nearby country town. The assembly has been organised by a group of local women, including the social climbing doctor’s wife and the local Baroness who is my villainess and a complete snob.

I needed a target for the Baroness’s snobbery, and fortunately Lady Avery was right there. So I put her on the committee of patronesses.

I also realised that I needed my secondary lead, Alex, who had been sent home to recuperate after breaking one leg and being shot in the other, to be mobile for a later scene, so I took the opportunity while he was having dinner at the doctor’s house to let him borrow a Bath Chair. In a prescient move, I explained that the chair had belonged to Lord Avery’s mother, and Lady Avery had donated it to the doctor when her mother-in-law died.

Which brings us to the Sunday in question. On Saturday evening, I’d been writing about what happened at the assembly, and the villain, feeling insulted by Alex, had sabotaged the chair.

It occurred to me that Bradshaw could be a retired carriage maker, and so he could diagnose that the collapse was foul play, and not fair wear and tear. Then I thought how much more fun it would be if his daughter provided the diagnosis, which would make her, as a tradesperson herself, even more of a target for the Baroness’s scorn.

By the end of the day, she was fully formed in my mind – an only daughter, born to older parents and their dear delight. With a bluestocking mother and a highly successful father, she is given the education of a lady, but loves best to follow her father around the manufactory. He does mainly design, but he teaches her to handle tools, and she turns her skills to designing and producing chairs for invalids.

In the real world, John Dawson invented the Bath Chair in 1783. [Or did he? See my post on the history of wheelchairs.] In my putative short story, Bradshaw Coaches is giving him a run for his money by 1805, when young Randall Avery comes looking for something a bit special in the way of chairs for his invalid mother.

And is directed to a workshop to consult with ‘Min Bradshaw’. Benjamin or Dominic, he wonders? Minerva is working on the undercarriage of a nearly completed chair.

The overalls were filled by a delightfully female rear. His stunned brain, impaired by the sudden loss of blood to other regions, could only think “definitely not a Benjamin or a Dominic.”

“Hand me that wrench.” The voice was undeniably female, too, with husky overtones that made him think… all sorts of things he shouldn’t think about an innocent, even if she was a tradesman’s daughter.

I’ve been researching the history of wheelchairs, which is meat for another blog post.