Jude Knight's Blog, page 145

April 26, 2015

Jessica Cale talks about sex in historical fiction

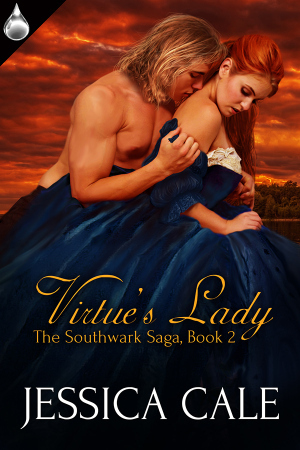

Today, I welcome Jessica Cale to the blog. Jessica is the author of Tyburn and her new release, Virtue’s Lady (see below the article). She describes herself as a recovering journalist with rather a lot of Nick Cave records writing historical romances out of a grey bedroom in North Carolina.

Today, I welcome Jessica Cale to the blog. Jessica is the author of Tyburn and her new release, Virtue’s Lady (see below the article). She describes herself as a recovering journalist with rather a lot of Nick Cave records writing historical romances out of a grey bedroom in North Carolina.

Sex in historical fiction

Sex can be a tricky topic in historical fiction because I think there are a lot of assumptions made about it that aren’t necessarily based on reality. There’s a tendency to believe that people were either better at abstaining or had enormous families, but the belief that the past was inherently more virtuous than the present is problematic. The truth is that people weren’t more sexually repressed or guided by some divine will power, but that the specifics of sex in history are too often neglected in history books because it’s seen as irrelevant, sensational, or controversial.

Myths about contraception and childbearing

One of the things that surprises people the most about sex in history is that contraception existed before the twentieth century. Condoms had existed since prehistory as evidenced by a 12,000 year old cave painting of the first condom in the Grotte de Combarelle in France, and the Egyptians had spermicidal pessaries and reliable urine-based pregnancy tests thousands of years ago. Sylphium, a sort of giant fennel, was such an effective contraceptive that the ancient world farmed it to extinction within 6,000 years. Condoms came into their own during the Renaissance when they began to take on a form we would recognize today, and Casanova himself recommended them to put ladies’ minds at ease regarding unexpected pregnancy. Condoms were regularly used from that point onward to prevent sexually transmitted disease, especially the epidemic of syphilis that returned to Europe with Columbus from the Americas. The withdrawal method was used, as well, and if that failed, there were a number of herbal mixtures that served as potent abortifacients, the recipes having been passed down through the generations with the earliest known ones coming from Ancient Egypt.

Another misconception is that people wanted to have lots of children. During the Restoration, as many as three in four children didn’t live to see their sixth birthday. Miscarriage, abandonment, and even infanticide were tragically common, as sanitation standards were abysmal and the poor couldn’t afford to have larger families. Furthermore, childbirth was the most common cause of death for women, with almost fifty percent of the female population losing their lives as a direct result of it. For common people, children were as much a burden as a blessing. The average age of marriage for men was between twenty-seven and twenty-eight, and for women it was between twenty-five and twenty-seven, so family sized tended to be naturally smaller, as well.

Myths about virginity, lesbianism, and marriage

It might also surprise you to learn that seventeenth century couples commonly cohabited before they married, sometimes for years, and virginity was not so carefully guarded a prize as it was for the upper classes that required it to ensure succession and inheritance. Women (and sometimes even men) commonly worked as prostitutes, and sometimes only for a short period of time to get ahead before they ultimately settled down or opened a business for themselves. Marriage for the poor could still take place with nothing more than a declaration and a witness.

Interestingly enough, lesbians existed and were tolerated or accepted in Britain over the last few centuries. There wasn’t always a term for it, but girls being unusually close was fairly common and even seen as innocent. What harm could come from a union that couldn’t result in pregnancy? There were even a few cases in the nineteenth century where women were allowed to marry, provided one of them presented herself as a man and attempted to serve the same role in society, which was seen by some as being more valuable and honorable than continuing to live as a woman.

The idea of the past being a time of virginity, strict heterosexuality, and repression is based on nostalgic nonsense. Sure, if your heroine’s life is riding on making a good marriage, she might be sheltered and totally inexperienced, but for the majority of the population, that just wouldn’t have been the case.

And a thought to consider

To wrap up, I’d like to leave you with a fun fact I’ve learned just this week. From at least the middle ages up until the nineteenth century, the female orgasm was believed to be necessary for conception, so the men of the past not only knew what it was, but they were good at making it happen. So much for sex in history being stuffy!

Virtue’s Lady

Virtue’s LadyLady Jane Ramsey is young, beautiful, and ruined.

After being rescued from her kidnapping by a handsome highwayman, she returns home only to find her marriage prospects drastically reduced. Her father expects her to marry the repulsive Lord Lewes, but Jane has other plans. All she can think about is her highwayman, and she is determined to find him again.

Mark Virtue is furious when Jane arrives in Southwark. In spite of his growing feelings for her, he knows that the crime-ridden slum is no place for a lady. Jane must set aside her lessons to learn a new set of rules if she is survive and to prove to Mark—and to herself—that there’s more to her than meets the eye.

Buy Links

Liquid Silver * Amazon * Barnes & Noble * Kobo * All Romance E-Books * iBooks * Goodreads

And meet Jessica on:

Website * Facebook * Twitter: @JessicaCale * Google+ * Tumblr * Pinterest * Tsu * Amazon Author Page * Goodreads Author Page

April 24, 2015

Lest we forget.

Today is Anzac Day. Today, New Zealand and Australia pause to remember those who fought and those who fell in service to their country. Anzac is an acronym from Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, the name given to the expeditionary force formed in Egypt in 1915 to fight in World War I.

Anzac Day has become a time for us to remember those — both in uniform and as civilians — who served in any of the armed conflicts in which Australia or New Zealand has been involved. But today is special. Today is 100 years to the day from the first landings on the beach at Gallipoli, in what is now called Anzac Cove.

As I type this, it is 6am in New Zealand and around the country people of all ages are attending dawn ceremonies. This is the crowd at Wellington, in the newly opened Memorial Park.

Here’s what it was like 100 years ago, in the words of someone who was there (George Bollinger, who kept a detailed diary).

Sunday 25th April The day is beautifully fine. We are steaming full speed, close to the southern shores of Gallipoli. What a day of days! We left Lemnos at 6.00 am and continuously from 8.00 am we have moved amongst a roar of thunder. At present we are within a very few miles of our warships and transports, which are stationary here. What a sight! Their big guns never cease, and as we see the flash and burst of the shells on land, we think thousands of Turks must be going under. Has ever a bombardment like this taken place before? Our men are very calm, and some are even lying about reading and taking no notice of the bombardment. Boom, boom, boom. It never ceases. What batteries could reply to these 15 inch mouths of destruction.

Monday 26th April 3.15 am. ‘Packs on’ was roared out. Torpedo destroyers are alongside to take us ashore. 9.40 am. On shore in the thick of it. The first casualty in our company was in my section. Just before dawn we were on the destroyers waiting for surf boats to take us ashore. Stray bullets were landing around us and suddenly Private Tohill who was standing just in front of me dropped with a bullet through his shoulder. Immediately after, Private Swayne was shot in the forehead. It was a relief to get ashore. The Australians were frightfully cut about effecting a landing yesterday. They say there are at least 6000 casualties. They did heroic work and the whole world will know of it. We are in a gully immediately behind the firing line and will be called in to relieve at any moment. Two New Zealand battalions were in last night and got cut about. The Turks have overwhelming numbers and it is a perfect wonder how the Australians captured these heights. In landing as many as 49 were killed in one boat and a whole regiment was practically wiped out. The din and roar and whistle of the missiles is awful. As we sit here the ambulance are passing with wounded on the stretchers. 5.00 pm. We climbed heights to take our place in reserve, to firing line. We are right in the fire zone and saw some awful sights.

Tuesday 27th April At daylight this morning a terrific artillery duel raged. The Turks put hundreds of shells onto our landing place. At 10.00 am we were marched north along the beach, and as we got under heights we met crowds of wounded coming down. Oh how callous one gets. Word rushed down from above for Hawkes Bay and Wellington-West Coast Companies to reinforce at the double, as our fellows were getting massacred. We threw off packs and forgot everything in that climb up the cliffs. We fixed bayonets on reaching top and got into it. The country is terribly hilly and covered with scrub from four to five feet high. On we rushed against a rain of bullets and our men began to drop over, before they fired a shot. We started to get mixed and were everywhere amongst the Australians. Our men were dropping in hundreds.

Wednesday 28th April We were relieved about 8 o’clock. Mostly our nerves were gone.We retired back and tried to rest: our casualties were very heavy. We manned the trenches again at 6 o’clock. No sleep and nothing to eat, just a craving for drink, and the wounded always empty our bottles. The Turkish trenches are now on a ridge about 200 yards away. Our warships are shelling them, but unfortunately have also accounted for a number of our casualties.

We have been told many times that Australia and New Zealand learned to be countries, rather than simply colonies of Mother England, on the beaches of Gallipoli. That hell was, in some ways at least, the birthplace of our nations, and the beginning of our shared heritage.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

April 21, 2015

Thieves with a boat or patriots?

One of the made-to-order stories I gave away last month needed a bit of research. The winner asked for a buccaneer. So what, I wondered, was the difference between a pirate, a buccaneer, a corsair, a privateer, or any other ship-going bandit?

Thieves with ships

Pirates, I found, were fundamentally outlaws. ‘Thieves with ships’ one website I found called them. They ransack towns and capture ships looking for loot and people to sell or hold for ransom. They answer to no-one except their own appointed leaders, and recognise no law outside of themselves. Leaving aside the romantic image from books and movies, they were and are a ruthless lot of men and women, loyal only to one another and a danger to everyone else.

Not that I don’t find something to admire in the way that the pirates of the Caribbean ran a democratic society based on ability, where every man and woman of the crew had a say in how it ran and who should be captain, and a share of the loot. But I’d find it a challenge to make a hero of any of them. It could be fun, mind you, but I’d need a novel, not a short story.

Buccaneers, it turns out, were privateers and pirates in the West Indies in the 17th Century. The word comes from the French boucan, meaning smoked meat. The buccaneers started by selling meat gained from hunting, then found there was more money to be made by attacking towns on behalf of the French and the English, who were at war with Spain at the time.

And corsair is a word the English applied to foreign pirates, particularly Muslim pirates operating out of North Africa. They also applied it to the French and even the Spanish when at war with them, which was most of the time. They intended that as an insult, and it was certainly taken that way. Corsairs were also keen to find loot, but they were particularly interested in capturing slaves. Muslims being forbidden to enslave (or even rob) other Muslims, the corsairs attacked any underprotected European or American ship that strayed into their path, thus combining the religious duty of harrying the infidel with the economic pleasure of making a profit.

Thieves with a licence

Which brings us to privateers. In times of war, governments would issue letters of marque and reprisal — commissions to entrepreneurs with boats. The licence or commission would give the ship the right to attack ships belonging to whoever the country was at war with. In the 1812 war between the United Kingdom and the United States, which is in the background of my short story Kidnapped to Freedom, both countries commissioned privateers. The US had a very small navy but a large merchant fleet, and the UK navy was heavily committed to the war against Napoleon.

The commission specified what they were allowed to do, and any prisoners were treated as prisoners-of-war. But the prize — the ship and the cargo — paid for the enterprise.

All-out privateers often sailed with multiple teams headed by ship masters, who could take over a prize ship and bring it back to port. They were essentially pirates, but with a single focus on their nation’s enemy. They would never dream of attacking a neutral or allied nation’s ships or ports.

Many cargo ships also carried letters of marque authorising them to seize enemy ships. This also made them privateers, but part-time privateers rather than full-time.

When the war was over, those cargo ships would carry on with their usual business. The problem with privateers, though, was that the end of the war destroyed their livelihood, and history records many pirates who began their lives as privateers but branched out at the end of the war they were commissioned for.

I made my short-story’s hero a merchant captain from the Maritime States of Canada, with letters of marque from the United Kingdom. I hope my winner thinks I’ve got close enough to a buccaneer.

April 19, 2015

Playing the story game

I have a pagination problem in my CreateSpace files, so CreateSpace tells me, and it won’t let me download a pdf proof until I fix it. Tonight. I’ll do it tonight when I get home.

Meanwhile, I thought you might like to see the covers of the two stories I wrote as prizes for those who won made-to-order stories from me last month: one at the Bluestocking Belle’s housewarming party, and one at the launch of Farewell to Kindness.

Here’s how I play the made-to-order story game.

The winner gives Jude Knight three characters or objects, and a trope. Jude writes a 2000 word to 5000 word short story any way she likes, but it needs to include the three choices and be an interpretation of the trope. Jude retains copyright (and may use the story later either as it is or amended), but the winner gets a printed copy despatched from CreateSpace within three weeks of giving Jude the specification. (Delivery speed will depend where in the world you happen to be.)

Crystal and Tiffany, Saturday is the three week point, and I’m going to make it!

April 17, 2015

In defence of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham by Jacqueline Reiter

Today, I welcome Jacqueline Reiter to the blog. Jacqueline has a PhD in late 18th century political history from Cambridge University. She is very possibly the only world expert on the life of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, and has written an unpublished novel about his relationship with his brother William Pitt the Younger. She is currently writing Chatham’s biography for Pen & Sword Books. When she finds time she blogs about her research at https://alwayswantedtobeareiter.wordpress.com and she tweets at https://twitter.com/latelordchatham.

Today, I welcome Jacqueline Reiter to the blog. Jacqueline has a PhD in late 18th century political history from Cambridge University. She is very possibly the only world expert on the life of John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham, and has written an unpublished novel about his relationship with his brother William Pitt the Younger. She is currently writing Chatham’s biography for Pen & Sword Books. When she finds time she blogs about her research at https://alwayswantedtobeareiter.wordpress.com and she tweets at https://twitter.com/latelordchatham.

I’ll be bold: John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham was a very interesting, and thoroughly underappreciated, gentleman.

I know that’s what you’re thinking. (Unless you’re thinking “Who is the 2nd Earl of Chatham?” in which case don’t be bashful, because you’re not alone in that.) Really? The 2nd earl of Chatham? Why bother with him?

It’s a very good question. Chatham has a terrible historical reputation. His claim to infamy is his unfortunate attempt to command a military expedition. The result was the disastrous Walcheren campaign of 1809, which went as wrong as any expedition can be expected to go. Walcheren aside, he is overshadowed by his famous father, Pitt the Elder, 1st Earl of Chatham, and his equally famous brother, Pitt the Younger. “Unattractive, vain, pompous, stupid,” thundered the 1940s Pitt family chronicler Tresham Lever: “The most stupid and useless of the Pitts”.[1]

“Stupid and useless”?! I couldn’t disagree more. I stumbled on Chatham by accident while studying his famous brother, and he has never let me go since. It’s rare to find someone so universally deprecated, and, while the stories about him aren’t all unfounded, he has definitely had a bad press. Don’t believe me? To help you make up your mind, I present five facts about John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chatham – or, as I tend to call him, John.

He wasn’t stupid

Nope, not even a bit of it. Not as clever as his brother William, perhaps, but none of the Pitt siblings was stupid. His education (at home, with a tutor) was considered “singular” by at least one contemporary, but it furnished him with a lifelong love of complex mathematics (he was discussing Euclidian geometry in his letters at 15) and natural history. Like his father and brother, he was an accomplished classicist. When he grew up he was considered a sensible sort, with a reputation in cabinet for giving unostentatious good advice.

….. But he was vain (and lazy)

Mmmm. His nickname of “the late Lord Chatham” was not undeserved. Joseph Farington recalled that, when Chatham was compared with his successor as First Lord of the Admiralty, “it was admitted that Lord Chatham has greater abilities, if an unconquerable indolence, did not prevent their being exerted”.[2] I’ve rarely seen him making appointments earlier than two in the afternoon. I once read about him reviewing the militia at ten a.m. and nearly fell over in shock.

Mmmm. His nickname of “the late Lord Chatham” was not undeserved. Joseph Farington recalled that, when Chatham was compared with his successor as First Lord of the Admiralty, “it was admitted that Lord Chatham has greater abilities, if an unconquerable indolence, did not prevent their being exerted”.[2] I’ve rarely seen him making appointments earlier than two in the afternoon. I once read about him reviewing the militia at ten a.m. and nearly fell over in shock.

Chatham even kept the King waiting. He once turned up four hours late at a royal function.

And, yes, he was “vain”, maybe even “pompous”. His niece, Lady Hester Stanhope, said that never “did anybody ever contrive to appear as much of a prince as he does: his led horses, his carriages, his dress, his star and garter [KG! KG!], all of which he shows off in his quiet way with wonderful effect”.[3] Chatham’s brother William had a reputation for sloppy dressing, frequently described as wearing muddy boots or greasy leather breeches. Chatham would rather have died.

He wasn’t lucky

“If ever any individual drew a prize in the great lottery of human life, that man was the present Earl of Chatham”, Sir Nathaniel Wraxall wrote, cuttingly.[4] Wraxall was a jealous, poisonous gossip. Chatham’s luck was superficial and I don’t envy his life one bit.

But he inherited one of Britain’s most famous titles

True: but it stopped him leading his own life. His parents forced him to resign from the army in 1776 as a protest at the war with revolutionary America. When he returned in 1778 he was obliged to accept undesirable postings to places like the West Indies to avoid being deployed against the American rebels. Later, he was forbidden from serving on the continent lest he die and propel his heir (his brother William Pitt) into the House of Lords. And though he undoubtedly benefited from being the prime minister’s brother, he was constantly compared to his more famous relatives.

OK, but he inherited pots of money, yes?

Also true, to an extent. Chatham inherited a nominal income (after 1803) of £7000 a year, a £4000 pension settled on the Earldom of Chatham and a £3000 pension acquired by his father for three lives. Whoopee, as they say. But the estates he inherited were so mired down in debt that Chatham had no choice but to sell them (his father actually raised more than £10,000 IN ONE GO on the security of his son’s inheritance, and there were other debts as well).

Chatham unfortunately didn’t learn from his father’s poor example. He spent most of his life taking out massive loans from friends and moneylenders (some respectable, others ……. less respectable) to help keep him and his wife in West End properties, carriages and expensive silverware. But, after working through a number of bonds, contracts and legal proceedings detailing the Chatham family finances, it seems he started off at a distinct disadvantage. He was still trying to fulfil the terms of his father’s will as late as 1809, nearly thirty years after the first Lord Chatham died.

Very well. But he was lucky in love.

Chatham married his childhood sweetheart, Mary Elizabeth Townshend, after an endearingly bashful courtship. (Chatham came over all tongue-tied every time he tried to propose, and kept missing opportunities to speak up. It’s all rather sweet, although I suspect Mary wanted to kick him in the shins by the end of it.)

The couple remained close throughout the thirty-eight years of their marriage. They went everywhere together (except on campaign) and I’ve never been able to substantiate the rumours that he had a mistress. (And anyway he’d never have had time: as I said, he and Mary went EVERYWHERE together.)

But Mary’s life was full of illness. She spent nearly the first year of her marriage unable to walk across the room due to some sort of rheumatic complaint. She celeberated her recovery with a miscarriage, and never did manage to carry a child to term. Worse still, between 1807 and 1809 she developed what may have been a form of schizophrenia. It nearly broke their marriage; remarkably, it did not. But Mary relapsed in 1818, and never really recovered. She died suddenly in 1821 of unidentified causes, and Chatham remained profoundly depressed for over a year.

Not so lucky, then.

He wasn’t as pathetic as people think

Chatham’s public reputation rests on his less-than-stellar performance at Walcheren, and his career as First Lord of the Admiralty and Master-General of the Ordnance. Walcheren didn’t cover him with laurels, and I must say he was not the right person for that task. But his cabinet career did not suck nearly as much as people think.

Everyone who worked closely with Chatham seems to have been fond of him, in a rather protective way. He remained friendly with several members of his Admiralty Board long after he left the Admiralty, and one of his underlings at the Ordnance thought he was the best Master-General in a generation (no, really, I’m not making this up). And his military secretary at Walcheren, Thomas Carey, wrote (AFTER the failure of the campaign): “In understanding few equal him, & in Honor or Integrity He cannot be excelled”.[5]

Hyperbole? Perhaps. But one thing’s for sure: Chatham inspired loyalty.

He’s worthy of your time

As great as his father or brother? Not a chance. An administrative genius, or a great military commander? Hah, don’t make me laugh. But unimportant? Uninteresting? Unworthy? Sorry, can’t agree. He spent more than twenty years at the highest levels of government, holding highly responsible wartime posts; he’s much more than the bunch of unsubstantiated rumours circling about him in the contemporary and secondary literature. (And don’t get me started on THOSE.) He’s not in the first rank of historical personages, but he mattered.

Have I convinced you yet?

References

[1] Sir Tresham Lever, The House of Pitt (London, 1947), pp. 361-2

[2] Joseph Farington, The Farington Diary I (London, 1922), 64, 170

[3] Duchess of Cleveland, The Life and Letters of Lady Hester Stanhope (London, 1914), p. 52

[4] Sir Nathaniel Wraxall, Posthumous Memoirs of my Own Time (London, 1836) III, 128

[5] Thomas Carey to William Huskisson, 3 May 1810, BL Add MSS 38739 f 26

April 15, 2015

No such thing as a free lunch

Sharks enjoy free lunches right up until fish and chips time.

One of my friends pointed out to me this morning that Farewell to Kindness and Candle’s Christmas Chair are both up on a free ebooks site.

As we explored further, we found some peculiar things.

First, every book we looked at had been downloaded 600 and something times, and had 40 something reviews.

Second, this included books that had never been published, some of which we haven’t finished writing.

Third, the text describing the books, the cover images, and the reviews (where there are reviews) are identical to those available on Goodreads.

And when we clicked on the links to go to the sites for downloading and for reading on line – both supposedly separate sites from the front-end listing site – we found identical text, complete with grammatical errors, on all three sites.

When we tried to go further and were asked for our credit card details, we stopped.

So here’s the thing. Don’t try to read free books from an internet site.

Many of them are virus traps or fronts for scammers who want to steal your money, your identity or both.

Even if you don’t nuke your computer or lose your life savings, you’re likely to get a substandard product, particularly if it has been scanned in a hurry by someone who needs to get the book through the OCR software before they have to get it back to the library.

And let’s not even talk about the writer, who has put in months, maybe years, to write the book and who is lucky if they get $1 in the hand for each sold copy. Figures for average number of books sold vary depending who you’re talking to, but 100, 250, and 500 are the numbers I hear most often. A week, you say? A year? No, good reader, ever. In the book’s entire life. If you don’t feel bad about taking a dollar off someone who gets paid $500 for a year’s work, then drop me a line. I have a url for you, and all they’ll want in return is your credit card information.

We authors understand that budgets aren’t infinitely flexible, and that – while food and housing come before books – books are a life necessity. We understand because nearly all of us have lived on constrained budgets, most of us still do, and few of us make more from writing than the writing habit costs us.

The world is full of ways to get cheap good books: libraries, subscription schemes, legitimately free books or books for 99c. Join a few readers’ groups on Facebook or sign up for an eretailers newsletter to find out when books are on sale. Come to book parties and join in the games. If you’re a keen reader, why not write reviews? Many people who have set up a book review site have more books than they can handle given to them, because writers need honest reviews like babies need milk, and for many of the same reasons.

In the end, I can’t stop people pirating my books, and I wouldn’t if I could. At least they’re being read. And maybe the people who read them will go on to buy other books from me later. If they survive the shark-infested waters of pirate land, that is.

April 13, 2015

Romance novels are feminist

Here’s a book I’m putting on preorder: Dangerous Books for Girls by Maya Rodale. I did her survey last year when she was researching for the book, and I read the preview over the weekend. Here’s an excerpt:

Here’s a book I’m putting on preorder: Dangerous Books for Girls by Maya Rodale. I did her survey last year when she was researching for the book, and I read the preview over the weekend. Here’s an excerpt:

It’s easy to see how women were stifled in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: for most women owning property, financial independence, a real education, and a voice in the political process were just not on the table. And while women’s status has changed dramatically for the better in Western society, we’re still Not. Quite. There.

It has been nearly a century since the Equal Rights Amendment was proposed and it hasn’t been ratified to the U.S. Constitution. Women still do not receive equal pay for equal work. We are still debating whether women can have control over their own bodies—but insurance will gladly cover all the Viagra a man wants. Our academic institutions and respectable media predominantly study and review literature by men—and they definitely don’t cover genre fiction, like romance. That’s just America. China has one child policies resulting in an overabundance of boys. In Afghanistan, families without sons encourage their daughters to live as boys (the practice of Bacha Posh), because it’s shameful to be a girl or to have a girl. Again and again we see women considered less—unless it’s in a romance novel.

Because of this high valuation of men and low valuation of women, we’re more comfortable talking about one, lone man instead of a genre that speaks to the hopes and dreams of millions of women.

This isn’t about bashing dudes. Romance readers love men. There are even men that love romance novels. Romance novels are all about two individuals meeting and loving and living as equals. It’s not even just about men and women and heterosexual relationships. Romance novels featuring LGBT characters are written and read and becoming increasingly popular. Romance novels are about two people discovering their best, true selves and finding a loving, egalitarian relationship.

But when the subject of romance novels comes up and we talk about Fabio, we are really talking about a cultural tendency to value dude stuff more than lady stuff. We are showing our fear of love and pleasure. And we are sidestepping a conversation about possibly the most revolutionary, feminist literature ever produced.

Take a look for yourselves. Fabulous stuff.

April 11, 2015

Alpha and omega

My hero in Farewell to Kindness is an alpha male.

No, not the Alpha and the Omega, though it is Sunday here in New Zealand.

In a number of Facebook events, and most recently in a discussion on the Facebook group ‘I Love Historical’, we’ve been invited to comment on whether we prefer alpha or beta heroes.

I wasn’t quite sure what people had in mind by the terms, so I’ve done a bit of research, and here’s the result.

The terms come from research into dominance hierarchies in social animals. The alpha male is the leader; the one with the greatest access to food and mates. In some social species, only the alpha male can mate; in others, mates are shared by the alpha and his trusted lieutenants; in still others, the males lower down the social hierarchy will sneak access to the females, or several lower ranked individuals will gang up on the boss.

David, the hero of my current WIP Encouraging Prudence, is a beta.

The beta male is the lieutenant — the alpha’s trusted offsider. He will often take over as alpha if the alpha is disabled or killed.

Next down the hierarchy is the gamma, and so on, till we get to the omega — the animal no-one wants to be, the weed who everyone picks on.

Depending on the species, females can also be alphas, betas, gammas, and omegas. A female alpha might be pack leader, as with hyenas, or half of an alpha pair, as with wolves.

Popular culture has seized on the terms alpha and beta, but has them wrong. I found a lot of articles implying beta was the opposite of alpha, and was a bad thing to be. Not so. Beta is the cushy role, the wingman spot. Beta individuals suffer less stress, but still enjoy many of the benefits of leadership as they coast along in their leader’s train.

How much any of this applies to people is questionable. We’re a hierarchical social animal, beyond a doubt, but our tendency to pair bonding and our ability to ignore our instincts both mitigate against a true alpha, beta, gamma type of social structure.

How much any of this applies to people is questionable. We’re a hierarchical social animal, beyond a doubt, but our tendency to pair bonding and our ability to ignore our instincts both mitigate against a true alpha, beta, gamma type of social structure.

That said, the categories are more useful than I expected in romantic fiction.

Think of the alpha male as the one who must be in charge; the natural leader who finds it hard to sit back and let others take the lead (though a good alpha is happy to delegate to a trusted beta).

The beta male is the one with the same ability to lead but not the same drive to always be first; the lieutenant who can always be trusted to support his leader but who can step up to take over if he has to.

And the gamma is a follower born, happy to take and carry out orders, and only really happy when he has someone to look up to.

I’ve saved this chart in my character tools database. I found it on an organisational psychologist’s site, and I think it will be a great help in character development in novels to come.

April 9, 2015

The 18th century cookie cutter

I’ve found some lovely cookie cutters while I’ve been researching for Gingerbread Bride.

Flat hard wafers seem to have first been made in 7th century Persia, and spread into Europe through the Muslim conquest of Spain. And gingerbread was a great favourite in England from medieval times.

Wooden moulds to shape the dough gave way to metal cutters in or around the 16th century. They were made on the spot to the buyer’s specification, every one different.

Historically cookie cutters were made by family members and itinerant tinsmiths who travelled the country. Often the tinsmith would spend several days making cake tins, pans and pails. The cookie cutters for the most part were made from left-over tin scraps. Some interesting examples have turned up showing they were made from flattened baking powder tins and canisters.

As well as the dough and the cutters, I’ve been researching the story. First written down in the 1870s, the gingerbread man is part of a much older classification of folk tales: the runaway food stories. The British tradition seems to have leant towards pancakes and bunnocks, but the gingerbread story, when it first appeared in print, came with the note that a servant girl told it to the writer’s children, and that she had it from an old lady. So I feel quite justified in using the story in my novella for the Bluestocking Belles box set. Here’s the excerpt where my heroine remembers the story.

Mary smiled with satisfaction as she placed the last of the little gingerbread ladies into the box. In the four weeks she had been at Aunt Dorothy’s, she had learned a number of recipes, and helped with all kinds of baking, but the gingerbread biscuits that the cook of the Ulysses taught her had become her special contribution to the success of the shop.

Making them took her back to the galley where Cookie ruled with a rod of iron over various helpers, but always had time for a lonely little girl. She could still hear his deep gravelly voice telling the story of the run-away gingerbread horse, or it might be a dog, or whatever cutter shape he had used at the time. She would be hovering over the tray of hot biscuits, waiting for them to cool enough to ice and eat.

“And he ran, and he ran,” Cookie would say, “with all the village behind him: the old lady, the fat squire, the pretty milkmaid, and the hungry sailor. But none of them could catch the gingerbread horse.”

The story would continue, with the gingerbread horse escaping one would-be eater after another, and mocking them all, until Cookie had iced the first biscuit, and she would then wait, patient and giggling, for the gingerbread horse to encounter the river, and the fox.

First, he’d put the horse over her back. Then, as the river water rose, on her head. And finally, she would tip her head back, and he would perch the biscuit on her nose, and say the words she had been waiting for. “And bite, crunch, swallow, that was the end of the gingerbread horse.”

Aunt Dorothy had round cutters, and star cutters, and cutters in the shape of various animals. When the miller’s daughter asked for gingerbread ladies and gentlemen for her wedding breakfast, Mary had been delighted with the conceit, and the cutters the tinker made to her pencil drawings worked very well.

The icing gave them clothes and features; a whole box of little gingerbread grooms, and a box of little gingerbread brides. The miller’s daughter would be very pleased.

April 8, 2015

Writing to a different drummer

Stop trying to fit in when you were born to stand out.

I write the type of historical romance that I like to read, with strong determined heroines, heroes that almost deserve them, and villains who are more than paper cut-outs. I like complex plots with real issues at stake, and I enjoy a sense of the rich tapestry of life, with characters galore. I especially like writers who create fictional worlds that they revisit time and again, where each book stands alone as a story, but where we meet characters we’ve known before from other books.

Quite early on while writing Farewell to Kindness, I had a few critiques from book industry people that suggested I was skirting too near to the edges of the historical romance genre. I should remove the villains’ POV chapters. I should simplify the plot. I should soften the heroine, who starts the book by threatening to shoot someone. I should remove some of the action and add in more about the romance. I should move the meeting of the hero and heroine closer to the front of the book. I should remove the two secondary romances, the heroine’s older sister, and a number of other characters.

These critiques were kindly meant. My advisers wanted me to write a book that would sell. Writers need readers. The story isn’t just the one I tell; it’s the one you hear, and until you hear it, it doesn’t live.

I didn’t ignore them. I tightened my writing a lot. I did remove some characters and ‘unnamed’ others to make them less distracting. But I didn’t completely rewrite my book, either. The book these advisers wanted me to tell could have been written by any competent writer. It wasn’t one I could throw a year of my life at.

I launched Farewell to Kindness last week, with over a hundred books presold and the reassurance that prereaders had enjoyed it. And I am finding readers, and I love that they’ve enjoyed the book, and cried in the right places, and argued over whether the hero’s cousin is an arrogant so-and-so, and written me some wonderful reviews. Maybe my audience will be small, and a different book may have reached more readers. But this is my book, and I love it.

Yesterday, a couple of things happened that prompted the following private message conversation with fellow Bluestocking Belle Mariana Gabrielle. The trigger was a series of comments from another writer about how we need someone experienced in the industry to comment on our books so that we can tailor them for the market.

Mariana: This laying down the law about writing for the market just bugs me. Silly, really, but true nonetheless.

Jude: It must be nice to know everything.

Mariana: LOL. Exactly. LOL really is one of those days!

Jude: Short weeks are always crazy. And I got a 3 star review on Amazon that pointed out the ways I don’t comply with industry norms. (Not a bad review — quite a fair one – but just a reminder of why I went indie.)

Mariana: I hate the fair ones.

Jude: This review started “This book is pretty good, but it’s not a good match for my tastes,” and went on to suggest cutting out a lot of the plot twists and spending more time on the romance. Which is fine, but this was not that book.

Mariana: ‘Not a good match’ says it all. At least that was acknowledged.

Jude: I get cross with those who pontificate about the one right way.

Mariana: Me, too; about anything, not just writing.

Jude: Yep. Makes my skin crawl. I’m fine with ‘right for me'; just not ‘my way or no way’.

Mariana: That’s why I trained myself to talk about what works for me. Much more palatable.

Jude: If I’d responded [on the post that triggered this conversation] it would have kept the point off topic. But I’m tempted to do a new post on how ‘the industry’ inevitably plays it safe by doing what has worked, and therefore is doomed to playing catch up when readers follow something new and different.

Mariana: That sounds like a good point, and I have opinions on that. Trying to be “the next XXXXX” is incredibly stupid. By the time you think it, you are too late.

Jude: If I let others shape my writing I might be mildly successful but dissatisfied.

Mariana: Many of my friends say, “You could write the next 50 Shades…” They don’t get that there is no next 50 Shades. No next Twilight or Harry Potter. Trying is a fool’s game.

Jude: If I write what I want to write, I will be satisfied, and if people like it they’ll need to come to me to get it.

Mariana: Yep. And my integrity will be intact.