Jude Knight's Blog, page 131

May 22, 2016

Bodice rippers, feminist literature, or just good yarns (Part 3 of 3)

This is the last part of the article based on my talk at Featherston Booktown. Part 1 talked about Dangerous Books for Girls, and the first of six reasons that romances are a threat to the establishment. Part 2 gave three more reasons. So here are the last two.

#5 Because female orgasms

Romance novels are about people falling in love, which means (whether they are at the sweet end of the spectrum or far down the other end at erotica) they are about people who feel a sexual attraction to one another. This might well be a revelation to some now, as it was 200 years ago. Women have sexual desires. Women experience sexual pleasure. And women’s feelings, sensations and experiences are different to those of men.

A novel is a safe place to explore sexuality. It can’t make you pregnant. People don’t get STDs by taking books out of the library. Romance novels tell women that a hero cares for the pleasure of his beloved; that he puts her pleasure ahead of his own. Dangerous Books indeed!

And today’s best romance writers are very good at writing about sex, unlike the authors celebrated in the annual ‘Bad Sex Awards’, from which comes this gem:

Surely supernovas explode that instant, somewhere, in some galaxy. The hut vanishes, and with it the sea and the sands – only Karun’s body, locked with mine, remains. We streak like superheroes past suns and solar systems, we dive through shoals of quarks and atomic nuclei. In celebration of our breakthrough fourth star, statisticians the world over rejoice.

Compare the list of ‘Bad Sex Award’ excerpts to the list of scenes that will get you hot and bothered, or this one, which is a first kiss.

She opened her mouth, already shaking her head, and he hurried on to say his piece before she could object. “You could marry me. I don’t flatter myself that I am a prize, but I am a better bet than Hackerton. Marry me, and let me care for you, Rose.” He bent, curving low to capture her mouth. It was as soft and full as it looked, though at first stiff and unresponsive.

But she followed his lead in this as she had in the dance, and what had begun as an impulsive gesture to prevent her from saying no became a luxurious vortex that spun him out of space and time until he was oblivious of everything except the giving, the taking, the sharing of their lips, their tongues, their mouths.

She looked dazed when he drew back. Well, good. He was dazed. He gathered her against his chest and rested his cheek on her hair. “Marry me, Rose,” he repeated.

#6 Because HEA

If a fictional heroine escapes the confines of the house, chooses love, has orgasmic sex, and dies at the end of the story, the message is clear: Don’t try this at home. But if she lives happily ever after? The message is also clear: Live the dream, girl!

In romance novels, the heroine lives. Not only that, she lives happily ever after, which is shorthand for a life of being loved for oneself and for having achieved a measure of security.

(Dangerous Books for Girls, by Maya Rodale)

Unhappy endings appear to be a convention in literary novels. They may be beautifully written, challenging, interesting, and effective in their own way. But they are not hopeful, and people need hope if they are to change their lives. Live the Dream!

While I’m here, can I just dispose of one particular feminist critique of romantic fiction, that it teaches women to believe that happiness lies in a successful love affair? Excuse me? This is a romance. Read the label on the box. If it says cornflakes, don’t grumble at finding cornflakes. If it says romance, don’t be offended by the happy ending.

The happy ending is not more nor less a fiction than all the killers brought to justice in murder mysteries, or the appearance of magical creatures and powers in fantasy novels, or technology that does not exist in science fiction. Do readers of thrillers really believe that a lone hero, with brooding good looks and the memories of an appalling childhood, will ride into town and save the day? No. It’s fiction.

But some killers are brought to justice, technology that was science fiction ten years ago is true today, sometimes one person might make a difference, and happy ending do happen.

And if some find that concept dangerous, isn’t that their problem?

Changing the world, one reader at a time

Around six months ago, I started posting my novel A Baron for Becky on Wattpad, one chapter at a time. ‘Grandmother,’ said the 15-year old, ‘don’t you realise that’s a site for fan fiction about One Direction?’

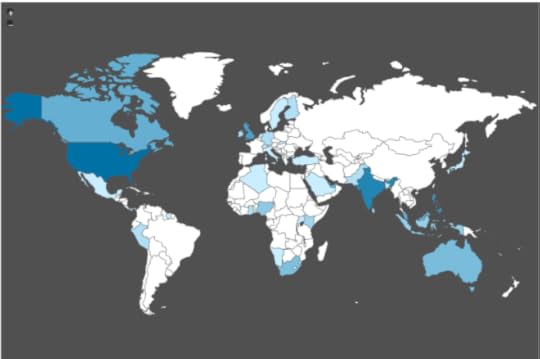

But I had read of other novelists building a following by posting there, and I figured it was worth a try. I did not know what to expect. I certainly didn’t expect the results reported in the site’s analytics. In the last few weeks, since I posted the final chapter and epilogue, ‘reads’ (Wattpad measures how many people read each part of a ‘work’) have been rising by several hundred a day. As of today, A Baron for Becky has had over 11,000 reads, and nearly half of those have been from parts of the world where romance novels are as dangerous today as they were in England two hundred years ago.

The darker the blue, the higher the concentration of readers: 15% in India, 9% in Philippines, 4.5% in Malaysia, plus readers in Pakistan, Nigeria, Uganda, Ghana, Algeria, Namibia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Peru, Suriname, Indonesia, Mexico and other places too small to show unless you zoom in on the map.

I’m writing Dangerous Books, and they’re being read by Girls.

Reading romance novels is an affirmative action

As I’ve said before, genre is not a statement about quality, it’s a way to sort books. So why is it still open season on romance novels. Why is it rare to find a romance novel in a high school syllabus, or the study of the genre at university.

Take a look at the names that the genre attracts: mommy porn, chick lit, bodice ripper—they’re all about gender. It is hard not to conclude that the unthinking dismissal, often by people who have never read a romance novel, is anti-woman. And if that’s the case, reading romance is an affirmative action.

So read romantic fiction proudly. Read the best, by all means. In my sub-genre, read Elizabeth Hoyt, or Grace Burrowes, or Courtenay Milan, or Mary Balogh, or any one of a score of other thoughtful talented writers who research carefully and write brilliantly.

Or read light frothy stuff that gives you a rest from your day job. Again, you have many fine writers to choose from.

But read a romance. By doing so, you are supporting a writer who believes that women should have the same freedom as men to make choices.

Bodice rippers, feminist literature, or just good yarns? (Part 2 of 3)

In part 1 of this article, I made the claim that romance novels are inherently feminist. Pop back and read part 1 for the argument so far!

In part 1 of this article, I made the claim that romance novels are inherently feminist. Pop back and read part 1 for the argument so far!

In part 2, I continue to argue the point that romances are Dangerous Books for Girls.

#2 Because the love match

Back when the romance novel first started, and even now in many parts of the world, marriages were not about being in love. Marriages were first and foremost alliances of families, at best a mutual exchange of value (my daughter for your cow, a better parcel of land for our joint grandson, your support in the House of Lords in return for my investment in your mills with a family connection to cement the alliance).

While technically in England neither party could be married without their consent after the mid-18th century Hardwicke Marriage Act, in practice, children (and particularly daughters) were raised to understand that marriage was about position, status, property, and opportunity.

The circles that controlled the most status and property, and that therefore had the most to lose if women wanted to have more than a token say in their life partner, were also those that controlled education and publishing. They had a vested interest in suppressing books that suggested that love matches were to be preferred, as do their counterparts in other parts of the world today.

This is not to say that the Brontes and Jane Austen and a plethora of other writers invented stories about love matches. But think of the great love stories before that time and name a few that ended well! Tristan and Isolde? Launcelot and Guinevere? Romeo and Juliet? Outside of fairy tales (As Valerie Paradiz points out in Clever Maids, fairy tales were stories shared for and by women), literature is largely and grimly devoid of happy love matches.

#3 Because escape

Romance novels, along with other genre novels, are often called escapist. This is used as a denigrator, as if escape is a bad thing. Who needs to escape? People in a cage. Who objects to escape? People who control the cage.

In romance novels, readers can live vicariously through the heroine. They can go to the ball. They can visit exotic places, triumph over the villain, fall in love with a rogue and have their heart broken then discover someone worthy to love instead.

They can take a break, a rest, from whatever consumes their day-to-day lives,—a high-pressure cut-throat job, childcare and housework, a daily grind just to pay the bills, illness or disability—and try being someone else for a change.

Escapist fiction broadens the view of what is possible. No wonder the establishment regarded it then, and still regards it now, as Dangerous.

#4 Because the author-ity

It has been said that men write about the big picture and women about the domestic world. This is a gross generalisation, of course. But certainly as a reader I tend to read more books by women than by men, because I’ve found that books by men tend to focus more on the chase, the action, while books by women tend to focus more on the personal growth of the characters. And I’m interested in people and how they interact.

An article about a program that picks the gender of a writer based on a piece of text has this to say:

Men more often concern themselves with actions, ideas, and analysis. Women more often concern themselves with processes, perceptions, and implications. Philip Ball observes, “men talk more about objects, and women more about relationships.”

Gender Genie claims a 60–70% accuracy, which is better than a random guess.

Romances are about human relationships, usually from the perspective of a woman. Women are the authority. More than that, a woman is usually the author. And in the (fictional) world controlled by the woman author, before the end of the novel the male love interest is going to learn to love, respect, understand and value a woman.

(When I got to this part of my talk, a man in the audience asked me if that meant this might lead readers to be disappointed in real life men, to which I answered ‘Yes, absolutely. And a good thing, too!’

Romances that teach women that they can be loved, respected, understood and valued are very Dangerous Books.)

Part 3 (two more reasons and the conclusion)

Bodice rippers, feminist literature, or just good yarns? (Part 1 of 3)

Story tellers tend to start from one of three main story elements: a character, a setting or situation, or something that went wrong. (How to Plot 101: don’t ask yourself what happened next; ask yourself what went wrong.)

For each of the following pictures, pick a main character, decide the setting, and tell yourself what went wrong. I’ve written below the picture what genre the story should be.

Now remember those main characters, and in a minute you’ll find out why.

What genre is best?

Genre is an interesting thing. It’s a sorting device that allows booksellers and librarians to shelve books into groups, to make it easy for readers to find the kinds of story they like, but in the minds of readers, and perhaps especially critics, it is sometimes scene as saying something about quality.

And no genre attracts more name-calling than the romance genre: trashy books, mummy-porn, bodice rippers, chick-lit. The headline to this blog post is the title of my talk at Featherston Booktown yesterday, and I heard from a number of people beforehand that they believed precisely the opposite. They had not themselves read romance, but they knew it to be poor writing, formulaic, and anti-feminist.

I have read romance. Lots of romance, and particularly historical romance, which is the sub-genre I write in. And I’ve read all sorts of other fiction too. And in every genre—not excluding mainstream and literary fiction—I’ve found books that are well written and researched, and books that are so poorly done I can’t finish them. I’ve also found those gems that stay with me; great books that change or deepen my view about something, so that I return and read them again, revisiting and finding deeper layers in the book and in myself.

There is no best genre. And there’s no worst genre, either.

So why does romance get so much flak?

Let’s define terms. A romance novel has two characteristics. If it doesn’t fit both, it may be an excellent book, but it isn’t a romance. (And remember, genre is just about how to shelve the book.)

the story is about the growing emotional attachment between two people

the story ends with the hope that the two people have a happy future together.

Romantic stories that qualify for the first but not the second include: Titanic, Romeo and Juliet, The Marriage of Mergotta, Gone with the Wind. Not romances.

And I’m using the term feminism to mean the belief that women have the right to the same social, economic, educational and other opportunities as men, and should be as free as men to make choices about those opportunities. By that definition, I’m a feminist. And so, I am about to argue, are romance novels as a genre.

Dangerous books for girls

So why, for more than 200 years, has the romance novel been derided by the establishment? I’ve organised my response under six headings taken from Maya Rodale’s book Dangerous Books for Girls: The Bad Reputation of Romance Novels Explained. Her headings, my thoughts—but I highly recommend the book. Her overview of the past 200 years, her survey results, and her thoughts about what it all means make fascinating reading.

So why were and are romance novels Dangerous Books for Girls?

Because women

Because the love match

Because escape

Because the author-ity

Because female orgasms

Because HEA

Let’s talk about what each of those mean.

#1 Because women

A few minutes ago, I got you to pick main characters for four different stories. How many women did you pick? When I did this exercise during my talk, male characters outnumbered female characters eight to three. I used the same painting several times for different genres, and I included the romance genre as one of the options. Twice. So two of those three women were main characters in a romance. (The other was a spy.) In the other genres, males outnumbered females eight to one.

This is pretty typical. Women had 30% of speaking roles (and 12% of lead roles) in recent movies. Books about women don’t tend to win literary awards, either. In her study of the last fifteen years results for six major book length fiction awards, Nicole Griffiths found that only one, the Newbury Medal, consistently had books about girls or women (girls, in this case, the Newbury being for children’s books). Of the other five—so seventy-five prizes in total (Pulitzer Prize, Man Booker Prize, National Book Award, National Book Critics’ Circle Award, and Hugo Award), only eight prizes were awarded to books with a woman or girl as the major protagonist. And, by the way, all of those were written by women.

Romances are written by women (about 80% of writers are women), for women (around 90% of readers), about women. Women are central or at least co-equal in almost every plot. They’re not a plot device. Even when the heroine is Too Dumb To Live, the plot still hinges on her choices. Even if the hero is a creep calling out for a restraining order, the plot still hinges on the heroine’s choices.

The book isn’t over till the heroine gets what she wants.

May 18, 2016

Animals on WIP Wednesday

My friend and fellow Bluestocking Belle Caroline Warfield is fond of owls, and is thinking of putting one in her next book. She comments that she has had sheep, goats, a dog, a cat, horses, and a number of chickens, but not an owl.

My friend and fellow Bluestocking Belle Caroline Warfield is fond of owls, and is thinking of putting one in her next book. She comments that she has had sheep, goats, a dog, a cat, horses, and a number of chickens, but not an owl.

My books have been relatively deficient in animals. One heroine’s daughter had a pet rooster, I wrote a short story about a pet cat, and horses are common. I had wolves in another short story, but they didn’t stay wolves for long, and were not pets. And, of course, The Raven’s Lady has a raven in it.

But animals feature in two current works-in-progress.

In my novella for the Belles’ holiday box set, I have a kitten. The housekeeper’s cat has produced a litter, and several of them will pop on in various stories in the set.

And two horses feature in the novel I’m writing at the moment: the heroine’s colt, which she has to leave behind when she escapes her bullying relatives, and the canal boat horse, Daisy.

Do any of your stories have animals? Share them here, in the comments. Here’s my kitten from The Bluestocking and the Barbarian.

When he left his chamber, three gold tassels depended from the front of each boot, and proved a tempting target. A kitten darted out from under an occasional table when James stopped to close the door behind him, and took a flying leap at the tassels, as James discovered when he felt the sudden weight.

He took a careful step, expecting the small passenger to drop away, but it buried its claws and its teeth into its golden prey and glared up at him.

“Foolish creature,” he told it going down onto the knee of the other leg so that he could reach it and remove it, carefully lifting each paw to detach the tangled claws. “These gaudy baubles are to attract my lady, not a fierce little furry warrior.” He lifted the kitten in one hand, and held it up to continue his lecture face to face. “Now where do you belong, hmmm? Have you wandered off from your Mama? Do you belong to this house, I wonder, or did you come with a guest?”

The kitten squeaked a tiny meow.

“No, little one. I will not put you down to chew my tassels, and to trip one of the great ladies or be trodden on by one of the gentlemen. You are a pretty little fellow, are you not?” He tucked the cat against his chest and rubbed behind its ears, prompting a loud rusty purr incongruously large for the small frame of the kitten.

Focused on the kitten, he was still aware of footsteps approaching and looked up to see Hythe, who looked uncomfortable in a tight fitting jerkin over short ballooning breeches that allowed several inches of clocked stocking to show between the hem of the breeches and the thigh-length fitted boots. The short robe, flat cap, and heavy flat chain gave a further clue, and Hythe had tried for authenticity by stuffing padding under the jerkin—a pillow, perhaps?

“Henry the Eighth?” James ventured, half expecting Hythe to walk past without speaking, or make another intemperate verbal attack.

Instead, the younger man nodded. “My sister Felicity picked it. Er… I wanted to speak with you… I owe you an apology, Winder… Er… Elfingham. My sister Felicity told me that… Well, the fact is I made an accusation without checking my facts.” Hythe nodded again, clearly feeling that he had said what he needed to say.

“Very handsome of you, Hythe,” James said.

Hythe ran a finger around inside his collar, flushing slightly. “Yes, well. The thing is… You will tell Sophia that I apologized, will you not?”

Ah. Clearly Sophia had expressed her discontent.

“Sisters can be a trial, can they not,” James said, and Hythe warmed to the sympathy.

“Just because she is older, she thinks she can…” He visibly remembered his audience. “Sophia is of age, and will make her own decisions. But I think it only fair to tell you that I have advised her to wait until after the hearing at the Privileges Committee before she makes any decision.”

James inclined his head. He could understand Hythe’s position. He hoped he could persuade Sophia to ignore the advice. Time to change the subject. He held up the little kitten.

“Do you happen to know where this little chap belongs?”

Hythe flushed still deeper. “So that’s where he got to. He… ah… appears to be mine. In a way. The housekeeper’s cat had kittens and this one seems to have adopted me. Little nuisance.”

But Hythe’s hands were gentle as he took the kitten from James, and he tucked it under his chin, his other hand coming up to fondle the furry head.

“I’ll just put him back in my room so he doesn’t get in anyone’s way.”

Hythe retreated back down the hall. James could not hear individual words, but from the sound of his voice, he was giving the kitten a loving scold. And James had managed to have what almost amounted to a conversation with his intended brother-in-law. He would count that as a win.

May 14, 2016

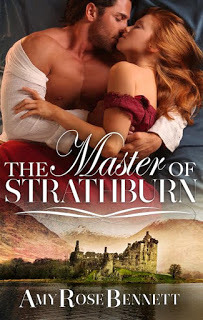

Review: The Master of Strathburn

For her newest release, Amy Rose Bennett has returned to Scotland, this time in the years after the failure of the Jacobite rebellion that resoundingly defeated in 1746. I loved Lady Beauchamp’s Proposal, and this novel is even better.

For her newest release, Amy Rose Bennett has returned to Scotland, this time in the years after the failure of the Jacobite rebellion that resoundingly defeated in 1746. I loved Lady Beauchamp’s Proposal, and this novel is even better.

The eldest son of the Earl of Strathburn has returned home. But it won’t be fatted calf on the spit if his stepmother and younger half-brother gets his way. Robert Grant was spirited away ten years ago, just ahead of arresting soldiers, after he led men in the disaster that was Culloden. And if Simon and the redcoats catch him, the charge of treachery still stands.

Jessie Munroe is in hiding from Simon, too. He is determined to make the lovely girl his mistress, and if she is unwilling, so much the better. In Simon’s view, that adds a bit of spice.

When Robert and Jessie both choose to hide in the same place, the sparks we’ve come to expect from Ms Bennett set fire to the page. Without giving away too much of the plot, I can tell you to expect misunderstandings, a noble warrior protector with a hot body, a determined intelligent heroine, and a couple of truly nasty villains. Simon is the kind of horrid person who pulled the wings of flies when he was a boy.

But his mother is well and truly worthy of the tradition of Lady Macbeth and the wicked stepmother trope. She is not at all concerned about her son’s fondness for raping the help, gambling and spending away the estate’s income, and drinking himself blind. He is her boy, and should be allowed to have what he wants.

Ms Bennett has given us a thrilling romance with an historical background that feels authentic, a couple of chase scenes with cliff-hanger consequences, some clever plot twists, and plenty of passion. I’m delighted to have had the opportunity to review an advance reader copy.

See Amy Rose Bennett’s New Sexy Novel for more about the book, and some buy links.

May 12, 2016

Amy Rose Bennett’s new sexy novel

Today, I welcome Amy Rose Bennett to my site on her blog tour for the Master of Strathburn. I loved this book, and will be posting a review within the next 24 hours, but meanwhile, read on.

And if you love Facebook parties, join Amy for hers: 15 May at noon till 5pm EDT.

About the Book:

Title of New Release: The Master of Strathburn

Publisher: Escape Publishing (Harlequin)

Release date: May 15, 2016

Blurb:

Robert Grant has returned home to Lochrose Castle in the Highlands to reconcile with his long-estranged father, the Earl of Strathburn. But there is a price on Robert’s head, and his avaricious younger half-brother, Simon, doesn’t want him reclaiming his birthright. And it’s not only Simon and the redcoats that threaten to destroy Robert’s plans after a flame-haired complication of the feminine kind enters the scene…

Jessie Munroe is forced to flee Lochrose Castle after the dissolute Simon Grant tries to coerce her into becoming his mistress. After a fateful encounter with a mysterious and handsome hunter, Robert, in a remote Highland glen, she throws her lot in with the stranger—even though she suspects he is a fugitive. She soon realizes that this man is dangerous in an entirely different way to Simon…

Despite their searing attraction, Robert and Jessie struggle to trust each other as they both seek a place to call home. The stakes are high and only one thing is certain: Simon Grant is in pursuit of them both…

Pre-order Buy Links:

Amazon: http://ow.ly/ZJKFR

Barnes & Noble: http://ow.ly/102Xim

iBooks: http://ow.ly/102Xtu

Google Play: http://ow.ly/102XJ1

Kobo: http://ow.ly/102XQu

About the Author:

Amy Rose Bennett has always wanted to be a writer for as long as she can remember. An avid reader with a particular love for historical romance, it seemed only natural to write stories in her favorite genre. She has a passion for creating emotion-packed—and sometimes a little racy—stories set in the Georgian and Regency periods. Of course, her strong-willed heroines and rakish heroes always find their happily ever after.

Amy is happily married to her own Alpha male hero, has two beautiful daughters, and a rather loopy Rhodesian Ridgeback. She has been a speech pathologist for many years but is currently devoting her time to her one other true calling—writing romance.

Connect with Amy:

Website and Blog: http://AmyRoseBennett.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AmyRoseBennett.Author

Twitter: https://twitter.com/AmyRoseBennett

Pinterest: http://www.pinterest.com/AmyRoseBennett/

Hosted By:

Secret Realm Book Reviews & Services

www.thesecretrealm.com

May 11, 2016

Antagonists on WIP Wednesday

I do enjoy writing a good villain. Not all of my books have one. Sometimes, the only obstacles to the hero and heroine come from within, or from their life circumstances. Overcoming those can be hard and the journey can be satisfying, but for a true hiss-boo moment, with rotten tomatoes flying from the audience and ladies fainting in the gallery, we need a moustache-twirling, hand-rubbing, snickering, wicked villain.

I do enjoy writing a good villain. Not all of my books have one. Sometimes, the only obstacles to the hero and heroine come from within, or from their life circumstances. Overcoming those can be hard and the journey can be satisfying, but for a true hiss-boo moment, with rotten tomatoes flying from the audience and ladies fainting in the gallery, we need a moustache-twirling, hand-rubbing, snickering, wicked villain.

So what does your WIP hold? Is your antagonistic force a person, and is that person a villain? Share an excerpt that shows him or her in all their dreadful glory! (And if you don’t have a villain, share your antagonist anyway.)

Here are two of my villains, from A Raging Madness. Ella is escaping from the window of her bed chamber, and stops at the bottom of the climb for a rest.

Inside, a very long way away on the other side of the gentle fog that embraced her, two people were talking. Constance and Edwin. It did not matter. They were silly people, anyway. Gervais had not admired his older half-brother; a matter in which he and Ella were in rare accord. The two men shared a mother, but little of that kind, gentle woman showed in either son: the one a bullying, often violent rake; the other a sanctimonious Puritan—but another bully for all that. Not as much so as his wife.

The bully was bullied. Ella suppressed her giggle. Sssshhh. Mustn’t make a sound. She was running away. Soon. First she would have a little sleep.

But as she closed her eyes, her own name caught her attention. Constance and Edwin were talking about her? She forced herself to concentrate, to listen.

“No, Mrs Braxton. Ella will not convince them she is sane. I have chosen with care, I tell you. I visited six asylums before this one, and this is perfect for our purposes. The doctor in charge has promised to keep her dosed, and even if he does not, the place itself will drive her insane. If you saw it, heard the noise… Yes, my dear, I can assure you, our plans are sound.”

Constance answered, the whine in her voice grating against Ella’s eardrums. “But what if you are wrong, Edwin? If she convinces someone in authority that she is sane, prison will be the least…”

“No, my dove. Not at all. No one at the asylum will listen to her ravings, and if they did, what of it? Who will they tell? Even in the worse case, all we need do is say her mind was turned after mother’s death, and how glad we are that she is well again.”

“I do not know.” The frown was heavy in Constance’s voice. “But we cannot keep her here. I trust Kingsford, but the other servants may start to murmur. It will drive her insane, you say?”

“It will. I guarantee it. I hesitate to mention it, Mrs Braxton, it not being a topic for a lady’s delicate ears…”

“Spit it out, Edwin. What?”

“My own treasure, I am given to understand that the attendants avail themselves of the, er, charms of the patients, and even do a, er, trade with the nearby town. Not, of course, with the approval of the medical staff. No, of course. That would be most unprofessional. But it is most enterprising of them, and serves our purposes rather well, dear sister being a comely woman.”

Ella puzzled this out. Surely Edwin did not mean that the attendants forced the women, and prostituted them?

“Ah. Very good,” Constance said. “The woman is horribly resilient. Any decent gentlewoman would have succumbed to madness long since with all your brother put her through, and what has happened since. But surely even she is not coarse enough to withstand multiple rapes.”

“The doctor will be here tomorrow,” Edwin said, with enormous satisfaction. “And she will be safely tucked away where she can do no harm.”

Their voices faded as they moved away, clearly leaving the room since the window went dark.

May 9, 2016

What’s love got to do with one of the earliest typewriters?

Did you know that one of the earliest typewriters was invented by a man for the woman he loved, who was going blind? She used the typewriter to write letters to her friends, including to the inventor. Isn’t that a cool story?

Did you know that one of the earliest typewriters was invented by a man for the woman he loved, who was going blind? She used the typewriter to write letters to her friends, including to the inventor. Isn’t that a cool story?

Having heard that at a seminar recently (on Web Accessibility, if you would believe it), I went looking for inventions inspired by love, and here’s part of my list.

There’s the ‘funky’ shopping cart invented by the man whose wife couldn’t carry the shopping bags and didn’t want ‘an old lady shopping trundler’.

There’s the man who invented a faster hair dryer (though that might have been impatience rather than love).

Almost two decades before Alexander Bell, an Italian immigrant invented a voice communication device to link his basement laboratory to the second-floor bedroom of his bedridden wife.

What about the sound technician married to a woman with cystic fibrosis that invented a device using sound to break up mucus in his beloved’s lungs?

The same desire to make life better for a loved one inspired two women. One invented a shirt that her husband could close with magnets so that his Parkinson’s did not prevent him from dressing himself. One created a belt that let her husband take the equipment that constantly cleansed his blood out onto the golf course, giving him back his freedom.

And then there’s familial love. For example, two rather famous men reckon they owed their invention to their mother’s love.

May 8, 2016

Sunday retrospective

In the last half of November in 2014, I was sent Farewell to Kindness off to beta readers and began writing Candle’s Christmas Chair.

In the last half of November in 2014, I was sent Farewell to Kindness off to beta readers and began writing Candle’s Christmas Chair.

The Epilogue to Farewell to Kindness threw me a curve ball that took me more than nine months to find in the bushes. I lost the heroine of what was then still called Encouraging Prudence. (And figuring out what my characters were trying to tell me has turned that book into two: Prudence in Love, and Prudence in Peril.) In ‘When you break eggs make omelettes’, I posted about the conundrum of stories that escape their author, with a long quote from Juliet Marillier.

I posted about happy endings, agreeing with those who criticise them as unrealistic, and pointing out:

The critics are, of course, quite right. Happy endings do not happen in reality. And neither do sad endings. In fact, endings of any kind are a totally artificial construct. My personal story didn’t begin with my conception; my conception was simply an event in the story of my parents, and my story is an integral part of that. Nor will it end at my death. What I’ve made (children, garden, quilts, books) will carry on after me.

Whenever we write and whatever we write, we impose an artificial structure on reality. We choose a point and call that the beginning. And we choose another point and call that the end.

My post about psalm singers might be worth a look. They played an important role in the communities of the 18th and early 19th century, and in my novel Farewell to Kindness. I give a bit of history and a couple of YouTube clips of songs as they might have sung them (one psalm and one considerably more secular).

‘How to tell what novel you are in’ was a link and quotes from a series of Toast posts, including How to tell whether you’re in a Regency novel, and How to tell whether you are in novels by a number of other authors. A sample?

7. A gentleman of your acquaintance once addressed you by your Christian name as he brushed his fingers against the lace filigree of your fichu. You still blush at the recollection.

And in my last post for November, I talked about the cycle of the liturgical year, and how earlier times fitted this cycle to the rhythms of the season and the demands of agriculture. Before most people were driven from the land and commerce began to rule over piety, church holy days meant holidays. And even into the late Georgian, the week long feast of Whitsuntide remained.

In Farewell to Kindness, the action of a third of the novel happens before the backdrop ofWhitsunweek (also known as Whitsuntide).

Apart from walks, fairs, picnics, horse races and other activities, the week was known for the brewing of the Whitsunale. This was a church fundraising activity–the church wardens would take subscriptions, create a brew, and sell or distribute it during the week of Whitsuntide. It has a certain appeal. It would certainly be a change from cake stalls and sausage sizzles!

Whitsunweek was the week following the Feast of Pentecost (WhitSunday), and seems to have been the only week-long medieval holiday to survive into early modern times. It usually fell after sheep shearing and before harvest, and it was a week of village festivities and celebrations.

May 5, 2016

What went wrong in WIP Wednesday

What could possibly go wrong?

And I didn’t choose the title of this post to acknowledge that it isn’t even Wednesday. Today, I’m using a writing tip as my starting point for the day’s theme.

When writing, don’t ask yourself what happens; ask yourself what goes wrong.

If nothing goes wrong, there isn’t a plot, and every plot is a series of obstacles, external or internal, between the protagonists and their goals.

So please share a few lines in your WIP where things seem to be going as they should but suddenly turn pear-shaped.

My excerpt is from the second book in The Golden Redepennings series, A Raging Madness. Alex and Eleanor have stopped in a village so that Alex (who has large chunks of shrapnel floating around in his thigh) can rest and Eleanor can go through the worst of the withdrawal from the opiates her horrible relatives have been forcing down her throat. But Alex has just met someone that Ella knows; someone who believes her brother-in-law’s claims that she is insane. Note that Alex, a product of his time, tries to avoid a direct lie.

Ella sat at the table under the window, where she could peer around the curtain at the garden without being seen. No rector yet. Down below, Alex had moved her chair so he could watch the path from the house. He was eating her toast, and drinking tea from the cup Jonno had poured her. After a moment’s hesitation, she lifted the window, just slightly. There. If they talked in the garden, she would hear the whole conversation.

She flinched at the sound of the door knocker, and fought the urge to run across to the other side of the house to see who was calling.

“See who that is, Jonno, would you, since our landlady is out?” Alex said calmly, and he had buttered and jammed another slice of toast before Jonno ushered two men out into the garden. Yes. The rector, and the other must be his friend, the local vicar.

From this angle, she could see Alex’s face, but not the rector’s. She could hear their voices, though.

“So! You are this Mr Reid. What are you playing at, Redepenning, and what have you done with poor Lady Melville?”

At the last question, Alex, whose eyes had been twinkling, sobered. “Lady Melville? She is still missing then? Surely you do not think I…?” He stood suddenly, looking so affronted that the rector took a step back. “Rector, I must protest. What sort of a gentleman would take advantage of a woman of frail mental capacity? I am not such a villain!”

He subsided back into his chair, waving the piece of toast he still held at the other seating around the table. “You will excuse me; the walk tired my leg. Please. Take a seat, gentlemen. Can my servant fetch you tea? I regret that our landlady is from home, but I would happily convey a message.”

The vicar sat, while the rector remained standing. “Mr Reid, or is it Major Redepenning…?”

“Mr Redepenning, in fact. I have sold out, sir, because of my injury. But I beg you to keep my true name a secret. A lady’s reputation, you know, though I am embarrassed to discuss such a matter with a man of God.”

The rector sat then, and rushed into speech, leaning towards Alex in his urgency. “Yes. Well that is the point, is it not? This so called lady; this Mrs Reid. If she is not Lady Melville, who is she? Eh? Who is she? That is the point.”

Alex, amusement lighting his face, said, “Jonno, is Mrs Reid still off on her walk?” He dropped his voice, confidingly. “You would be reassured if you could meet the lady, gentlemen, though I do not suppose she would be pleased with that solution. Alas, I fear I have been a disappointment to her. Hence the walk! And last time she lost her temper, I did not see her for months. Still, you are welcome to wait. I am sure she will return.”

He dropped his voice, and Ella had to strain to hear him. “She is not happy about her condition,” he confided. “Well. And one cannot blame her, of course.”

“Her condition?” The rector seized on the words. “She is ill?”

“Oh yes,” Alex confirmed. “That is why we stopped in this village. The motion of the carriage… One hopes the child is her husband’s, distressing though the thought is. It would be most unfortunate were it born with fair hair like mine. Or the Redepenning blue eyes. That would be hard for a husband to overlook, do you not think?”

“Sir!” The vicar rose to his feet, almost spitting with shock and horror. “I take leave to tell you, sir, that you are a despicable cad.”

(And yes. I’ve been missing my usual WIP Wednesday posts because things went wrong. But hey. Life.)