Jude Knight's Blog, page 123

December 25, 2016

Merry Christmas from sunny Featherston

December 23, 2016

Christmas presents in Georgian England

No presents, and no tree to put them under. Not on a Regency Christmas Day

Authors of Regency stories face an interesting challenge when writing a Christmas novel. Our modern readers are so accustomed to the association between gifts and Christmas Day that historical accuracy can be jarring for them.

Not that people didn’t give presents during the long Christmas season before the Victorians picked up a few German customs and marketed them through newspaper columns on the habits of royalty, Dickens stories, and popular magazines. People in the northern hemisphere have always given presents at some point during that season when winter seems as if it is going to last forever, but at last the night of the winter solstice passes and the days slowly begin to grow longer.

The day varied. Solstice night itself, the first day (or week) of the new year. People gave their children food treats hoarded against the feast, and gifts of dolls and carved animals, often home made. Wealthier people very likely gave richer gifts, as happens today. And kings and other leaders undoubtedly gave gifts to their followers, who would judge their personal standing with the boss by the size of the present.

Christian missionaries didn’t invent gift giving and feasting in the darkest part of the year. But they did Christianise it, ascribing the feast to the birth of Christ. And boy, was it a feast. In medieval times, people partied for 12 days (after fasting all December).

But they didn’t give presents on Christmas Day (or Christmas Eve, either). Instead, Christmas was a time for church going and feasting. The 24 day fast might have disappeared with the dissolution of the monasteries and the foundation of the Church of England, but the food blowout on Christmas Day remained, with all but the very poorest of the poor managing a special meal to mark the day.

The Puritans during the Commonwealth knocked off even that. No Christmas at all. But the Restoration meant all those Christmas customs crept back out of the shadows for people to rejoice in once again.

St Stephen’s Feast Day was the traditional day for giving to servants and tradespeople, and the needy (as good King Wenceslas did). The Feast of Stephen is 26th December. Family members didn’t get presents then, though. They had to wait.

In Scotland, 31st December, or New Year’s Eve, was gift day. English children had a few more days to go; family and friends were given presents on Twelfth Night, the day before the Feast of the Epiphany (6th January).

Different places, different customs. Children in various parts of Northern Europe received their presents from St Nicholas of Myrna on 5th December, the eve of his feast day or on the day itself. St Nicholas was born in France and buried in Italy, and quite why he favoured Dutch and German children with a visit is a mystery lost in history. He visited Central Europe, too, but not until 19th December, his feast day there.

In modern times, all these visits have been moved to 24th December, which makes the poor bishop’s task much harder. However, he has inherited Odin’s magic reindeer to pull his sleigh, so that must help.

Greek children had St Basil, whose feast day is 1st January. He arrived in the night on New Year’s Eve, leaving presents, and the families would exchange the gifts they’d bought or made at or after the New Year’s Day feast.

To make things even more complicated, different countries moved their calendars from Julian to Gregorian at different times.

All of which presents a minefield for a conscientious author.

My Christmas novellas include Candle’s Christmas Chair, Gingerbread Bride, and two novellas in Holly and Hopeful Hearts: A Suitable Husband and The Bluestocking and the Barbarian. Holly and Hopeful Hearts is on special at 99c, but the sale ends soon.

See my books page for more information.

December 21, 2016

Unwilling attraction on WIP Wednesday

out of copyright; (c) Museum of London; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

They met, they fell in love, their families were delighted, and they married. It would be a lovely life, but not a particularly exciting story. We authors like to torture our characters with all kinds of barriers along the way, and a favourite trope is the push-pull of unwilling attraction.

You know the sort of thing. Intellectual women with sharp tongues are not my type, but I can’t resist her. He is an unreliable rake, but his kindness is hugely appealing. We readers look forward to finding out how they get past their own preconceptions.

So share an excerpt, if you will, where your characters are feeling this dilemma, and I’ll give you one from the very start of A Raging Madness.

The funeral of the dowager Lady Melville was poorly attended—just the rector, one or two local gentry, her stepson Edwin Braxton accompanied by a man who was surely a lawyer, and a handful of villagers.

Alex Redepenning was glad he had made the effort to come out of his way when he saw the death notice. He and Captain Sir Gervase Melville had not been close, but they had been comrades: had fought together in Egypt, Italy, and the Caribbean.

Melville’s widow was not at the funeral, but Alex was surprised not to see her when he went back to the house. Over the meagre offering set out in the drawing room, he asked Melville’s half brother where she was.

“Poor Eleanor.” Braxton had a way of gnashing his teeth at the end of each phrase, as if he needed to snip the words off before he could stop chewing them.

“She has never been strong, of course, and Mother Melville’s death has quite overset her.” Braxton tapped his head significantly.

Ella? Not strong? She had been her doctor father’s assistant in situations that would drive most men into a screaming decline, and had continued working with his successor after his death. She had followed the army all her life until Melville sent her home—ostensibly for her health, but really so he could chase whores in peace, without her taking loud and potentially uncomfortable exception. Alex smiled as he remembered the effects of stew laced with a potent purge.

Melville swore Ella had been trying to poison him. She assured the commander that if she wanted him poisoned he would be dead, and perhaps the watering of his bowels was the result of a guilty conscience. The commander, conscious that Ella was the closest to a physician the company, found Ella innocent.

Perhaps it had all caught up with her. Perhaps a flaw in the mind was the reason why she tried to trap Alex and succeeded in trapping Melville into marriage, why she had not attended Melville’s deathbed, though Alex had sent a carriage for her.

“I had hoped to see her,” Alex said. It was not entirely a lie. He had hoped and feared in equal measure: hoped to find her old before her time and feared the same fierce pull between them he had been resisting since she was a girl too young for him to decently desire.

“I cannot think it wise,” Braxton said, shaking his head. “No, Major Redepenning. I cannot think it wise. What do you say, Rector? Would it not disturb the balance of my poor sister’s mind if she met Major Redepenning? His association with things better forgotten, you know.”

What was better forgotten? War? Or her poor excuse for a husband? Not that it mattered, any more than it mattered that Braxton used the rank Alex no longer held. It was not Braxton’s fault Alex’s injury had forced him to sell out.

The Rector agreed that Lady Melville should not be disturbed, and Alex was off the hook. “Perhaps you will convey my deepest sympathies and my best wishes to her ladyship,” he said. “I hope you will excuse me if I take my leave. I have a long journey yet to make, and would seek my bed.”

December 19, 2016

Tea with Mary

Mary was a daughter of the navy, raised aboard ship by her admiral father and a succession of nurses. She had learned her company manners from the gentlemen’s sons who vied to sit at her father’s table, and had them polished almost to breaking point during her one London Season.

Since then, she’d become wife to her own captain, and in her own world of naval wives, she knew precisely how to behave. She had even — her husband being grandson to an earl — become comfortable with those aristocrats she counted as family, counting among her close friends the wife of the current earl.

But having afternoon tea tête–à–tête with a duchess was outside of her experience. She had met the Duchess of Haverford at various entertainments in London. Her Grace’s sister had been mother to the current earl, so they had even attended some of the same family events. But she would never dare to presume on such a distant acquaintance were the circumstances not — what they were.

Summoned in response to a note asking Her Grace for an audience, she had expected to be seen as a petitioner, with perhaps a secretary on hand to make notes. Instead, she had been shown to a private sitting room, where two chairs waited in a sunny window overlooking a garden, the great lady herself occupying one.

“Mrs Alexander Redepenning, ma’am,” the butler announced, and the duchess rose to greet her.

Mary took the hand offered, and curtseyed. “Thank you for agreeing to see me, Your Grace.”

“But of course. You are family, my dear, and I always have time for family.”

“It is in that hope I have come, Your Grace.”

Shrewd hazel eyes examined her, then the duchess seated herself again, saying decidedly, “Then be seated, Mary — I may call you ‘Mary’, may I not? Tell me how you have your tea, and then tell me what I may do to help you with whatever distresses you.”

Mary obeyed, and was very soon sipping tea with lemon from a cup of delicate china.

“Well, Mary?” the duchess prompted.

“It is a long story, ma’am. It concerns Susan, my sister-in-law, her daughter Amelia, and my son James. I am not sure where to begin.”

“At the beginning, my dear,” Her Grace suggested.

Mary Redepenning is the heroine of Gingerbread Bride, a Christmas novella written for the Bluestocking Belles holiday box set in 2015. Gingerbread Bride is free this month as part of a promotion with 149 other novellas and novellas.

The Duchess of Haverford appears in many of my books, first helping her nephew with his love affair in Farewell to Kindness. She also aided and abetted the not-quite-hero, her son, in A Baron for Becky. Most recently, she has been the hostess of the Christmas house party in the Bluestocking Belles box set Holly and Hopeful Hearts, which is also on special for December, at only 99c.

This scene, though, takes place some twelve years later, when Mary’s 11 year old son and her 16 year old niece go missing, and her sister-in-law Susan disappears in pursuit. These events won’t happen until The Realm of Silence, which will be book three of The Golden Redepenning series.

You can read the first two chapters of Gingerbride Bride here.

December 16, 2016

The Virgin Wife

I’ve read a couple of stories recently that bought into the myth that non-consummation was grounds for an annulment. Even today, the law is not quite that simple, although many jurisdictions allow non-consummation as grounds for divorce. But back in Georgian and Regency England, the fact that the marriage had not been consummated, if it could be proven, was not grounds for either divorce nor annulment.

First, a definition of terms. Annulment is a legal declaration that a marriage never existed. Divorce is a legal declaration that a marriage is at an end, and the husband and wife no longer have marital obligations one to the other.

Annulments were not quick, they were not painless, and they required one or more of three circumstances. These circumstances were fraud; inability to contract a marriage; and impotence. Even taking the case could make both the husband and the wife social outcasts. If the annulment went through, the woman was reduced to the status of a concubine, and her children became illegitimate. The man had no further obligations to support her or the children.

Fraud could include using a false name with the intention of fooling your intended spouse or their family, or making promises in the marriage settlement you had no ability to carry out. For example, if you settled a non-existent estate on your daughter’s new husband, he could claim this as grounds for annulment. He would not necessarily win — it would be up to the church court to decide the extent to which any of these fraudulent behaviours were intentional, and how much they influenced the decision to marry.

Inability to contract a marriage meant that at the time of the marriage you already had a living spouse, you were related by blood to your intended spouse (closely enough for marriage to be forbidden — there was a list), you were sufficiently insane not to know what you were doing, or you did not have the consent of your guardian if you were under 21.

Proving that the man was impotent or the woman was incapable of sexual intercourse was even more difficult. Even if the man was prepared to admit to such a thing, the judges would not take his word. First came a medical examination. Was there a visible physical abnormality? Did the man show the ability to become aroused? Had the man shared his bed with his wife exclusively for years without the woman losing her virginity? (So no lovers on the side for either of them.)

If he could have an erection with anyone, he was clearly not impotent, and in earlier periods two accomplished courtesans might be hired by the court to test the impotency. By the 19th century, doctors were used, and one does not wish to enquire too closely into their methodologies.

Rats. There go some useful plot lines. But on the other hand, what fun to work your way around them.

December 14, 2016

Secrets on WIP Wednesday

New Zealand television currently has an advert for a car that says ‘when they write the story of your life, will anyone want to read it?’ To which my response as an author is ‘I hope not’. Boring fictional stories are happy life stories.

New Zealand television currently has an advert for a car that says ‘when they write the story of your life, will anyone want to read it?’ To which my response as an author is ‘I hope not’. Boring fictional stories are happy life stories.

To keep our fictional stories compelling, we authors look for plot twists and surprises. Where would we be without secrets? If all the characters and all the readers knew everything we know, the plot twists would disappear and the way to the ending would be obvious. No story.

This week, I’m inviting you to give me an excerpt about a secret. Finding it out. Becoming aware of it. Deciding to keep it. Hearing a hint at it. Whatever you wish.

Mine is from The Lost Treasure of Lorne, a made-to-order story I’m currently writing.

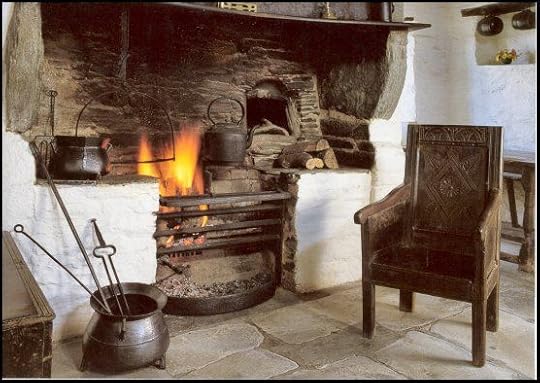

Caitlin spent a restless night ignoring the ghosts, which was becoming more and more difficult. She was in the kitchen and had already stoked the fire to toast a slice of bread when the cook arrived from the village, trailed by several kitchen maids.

“A bad night, was it?” Mrs McTavish asked.

Caitlin nodded, threading a slice of bread onto her toasting fork.

Mrs McTavish shook her head. “I can’t say I blame them. Just a week till the young master’s birthday and the end of the three hundred years. Sad, that. I can’t say but that the villagers will be pleased to see the castle free of its haunting, but it seems tough on the poor ghosties. If only there was someone to help young Master John fulfill the prophecy. Have a care, Mrs Moffatt. You’ll have the toast in the fire.”

Caitlin jerked her head back to the toasting fork, and returned it to the proper distance from the flame. “Just a week?” she repeated.

“Why, yes. 1485 it was that the Fourth Marquis of Lorne killed his daughter and her lover, and his father and mother for good measure. On the last day of August, so the old stories say, Lady Normington prayed to God for vengeance, and paid with her blood for the justice she sought.”

So Mrs McTavish was of the school that held the Normington woman was a prophesying saint, rather than a cursing witch. And no wonder the ghosts were growing so agitated. But wait. “Master John is a Normington, Mrs McTavish,” she pointed out.

“Half Lorimer and living in Castle Lorne. That’s been enough to doom someone to be a ghost afore now. He is Lorimer enough to find the treasure. But it is too late. Two, the lady said, and he the last Lorimer of Lorne.

This time, the toast caught alight before she noticed. It was not just what Mrs McTavish had said that distracted her, but the reaction of the ghosts. Crowding into the kitchen, row on row, even standing in the fireplace itself, they were cheering and clapping.

Two Lorimers. She had known that two were required, but — like the cook — she had believed it was too late. The King’s heralds had hunted down all branches of the Lorimer family tree and so had the Duke of Kendal, looking for one surviving twig, and coming up empty. They were wrong.

December 13, 2016

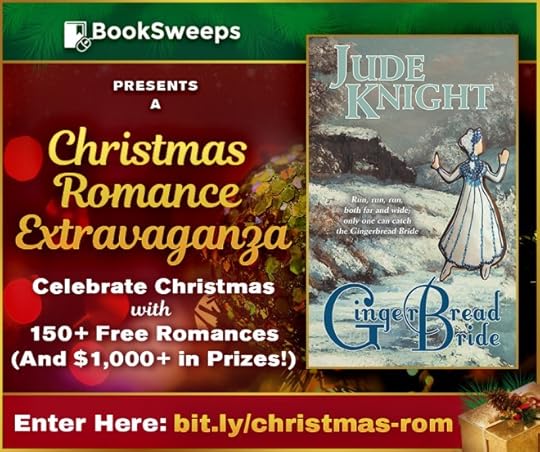

Revealed in Mist is available now

Prue’s job is to uncover secrets, but she hides a few of her own. When she is framed for murder and cast into Newgate, her one-time lover comes to her rescue. Will revealing what she knows help in their hunt for blackmailers, traitors, and murderers? Or threaten all she holds dear?

Enquiry agent David solves problems for the ton, but will never be one of them. When his latest case includes his legitimate half-brothers as well as the lover who left him months ago, he finds the past and the circumstances of his birth difficult to ignore. Danger to Prue makes it impossible.

Smashwords: http://bit.ly/2dBfNGq

iBooks: http://apple.co/2dVsHPq

Barnes and Noble: http://bit.ly/2dCsbCg

Kobo: http://bit.ly/2hrFztC

Amazon US: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B01N7HI8IA/

December 12, 2016

Tea with Charity

Charity Smith waited in the beautiful parlour to which she had been shown. Built to a more human scale than the gargantuan halls and stairways along which the butler had whisked her, the parlour was still rich and elegant, but she sensed that the paintings had been chosen to suit the pleasure of the room’s owner; that the duchess herself had the pretty wallpaper above the carved wainscoting and the plush drapes that picked out the cornflower blue of the wallpaper pattern. The chairs and sofas had been upholstered in darker blues or sea greens; here a floral, there a stripe. And here and there a bold red vase or cushion set off the more muted colours. And gold, or at least gilt, was everywhere: in the frames of paintings, on cupboard doors, inlaid into table tops, gilding the curves of carving.

Above, the same colours repeated in the ornately painted ceiling. This room was a far cry from the humble cottage in which she had been hidden for six years, or the farmhouse in Oxfordshire she shared with two other women and all their children. She stiffened her spine. The Charity of six months ago would have slunk away, intimidated by the gap between her and the woman she was about to meet. But the loss of her reputation, her marriage, and her home had paradoxically taught her her own strength. She would not be returning home without the child.

She stood and curtseyed when the Duchess of Haverford entered the room, unconsciously squaring her shoulders ready to fight. But the duchess surprised her. “Mrs Smith, I am so sorry to have kept you waiting. You must be beside yourself with worry about your dear sister. But I am confident that David will find her, and all will be well in the end. And, of course, you shall take your niece home with you when you go.”

As she spoke, she took a seat and patted the place at her side. “But come and sit down. Take tea with me and tell me about your children. Did you leave them well?”

Charity is the sister of Prudence Virtue, my heroine in Revealed in Mist. This scene happens after the end of Revealed in Mist, and during the events that start Concealed in Shadow. The first (which is a complete romance and thriller plot, and a stand-alone story) is released tomorrow. Follow the links to find out more, or read on for an excerpt.

“Are you sure Mr. Wakefield will not mind?” Charity asked for the hundredth time.

Prue reassured her again. Of course he would not object to her bringing Charity to his town house for a few days. Would he? Weeks of separation had left her yearning for him, but had it given him time for second thoughts? One slightly used spy, no longer in the first flush of youth, and with a secret that would surely give him a disgust of her, if he ever discovered it.

But Mrs. Allen made them welcome and told Prue the mail had brought a letter from David yesterday, saying he and Gren were leaving for London. They should be home tomorrow or the next day. Prue left Charity to settle into the bedroom Mrs. Allen prepared for her, while Prue wrote a note to Lady Georgiana, asking for permission to call.

They had talked it over at length while with Charissa, and in the carriage on the way from Essex. At inordinate length.

Charity could not, would not, stay in Selby’s cottage. She would go somewhere she was not known and introduce herself as a widow, using another name. Mrs. Smith, she said, for who was to find one Mrs. Smith among thousands?

But how she and the children were to live was a problem. Prue would help, of course. She could double the allowance she was paying, would triple it if Charity would allow. Tolliver’s work paid well enough, and she had a little set aside.

Charity wanted to borrow Prue’s nest egg. She had some idea of setting up a milliner’s shop. Not in London, but somewhere cheaper to live and safer for the children. “Even you said I make beautiful hats, Prue,” she argued.

True enough, but running a business required more than an eye for fashion and an artistic touch with a needle. Prue didn’t want her savings to be frittered away and leave Charity and the girls in a worse situation than before.

“We need somewhere for you and the children to stay while we consider how best to make your plan work,” she told Charity. “I know a lady who supports women in your sort of trouble. She may have a place.” Or she may never wish to speak to Prue again, in which case they needed to think of something else.

On one thing Charity was determined: Prue was not to ask Selby to support his daughters until they moved somewhere he could not find them. “It is not as if he is going to give us any money, anyway, Prue. He barely gave us a thing when I thought I was his wife. Just a few pounds now and again, when he visited. The servants’ pay is several quarters in arrears. Oh, dear. Should I not pay them before I let them go?” Another problem for her to worry at, until Prue was ready to leap screaming from the carriage with her hands over her ears.

The note sent, Prue went to check that Charity had everything she needed.

Her sister was sitting next to the window in her bedchamber, looking out.

“It is very grand, Prue, is it not? Not your David’s town house, though that is finer than I expected. But the streets, the carriages, the people. We are not even in London here, are we? Not really?”

“This is Chelsea,” Prue told her. “We are not in the City, but nor are we far. What would you like to see while we are here, Charity?”

“I will just stay here, Prue, please, except when we go to visit your friend. I want to make arrangements for somewhere to live, then go and collect the girls to take them to their new home. I miss them so much. Besides, imagine if I bumped into Selby!” Charity shuddered.

Perhaps she was wise, though in a city the size of London, the chances of her meeting Selby were slender.

“I need to go out, Charity. I received a note from the agency.”

Prue had told Charity about the mythical agency that placed her with people who needed temporary staff to fill a particular short-term need, and Charity anxiously grasped Prue’s hand.

“You are not going alone, Prue? Is there a footman you can take to protect you?” She shook her head, dismissing whatever thoughts of assault and robbery had entered them. “How silly of me. You know how to…” She made a vague gesture with one hand. Prue had been teaching Charity a few tricks to save herself from attack, some of which would discourage the most persistent man. Charity had been both repelled and intrigued.

“I will take a hackney, Charity, and my little gun.” And the knife strapped to her calf. And the pins in her hair.

“They will not want to send you away, will they? Oh, I am being so selfish. But Prue, I do not know what I would have done these past weeks without you.”

“I will not leave until you and the girls are safe,” Prue assured her. “If it is a job, I will tell them to find someone else.”

December 11, 2016

Revealed in Mist is nearly here

Revealed in Mist is released on iBooks, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, and Smashwords on 13 December. It’ll be coming on Amazon at around the same time — I’m putting the file up this evening or tomorrow evening New Zealand time, so it will be published as soon as it goes through their approval process. And it has been up on Amazon as a print book for over a week, since I wanted to order some books to come to New Zealand in time for an event in February, and the cheapest form of delivery takes a couple of months. I’ve even sold two print books! Woohoo!

Apart from sharing the memes I’ve made (see them below), I’m not making a big splash, but look in the New Year for a blog tour and some other activities. In particular, I’m planning a detective game, which I hope you’ll enjoy. Meanwhile, I’m looking forward to hearing what you think of my hero and heroine.

December 9, 2016

Give us our 11 days

I’m writing a story where one of the major plot pivots is the shift from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar, an event that (possibly) caused riots in Britain in the 18th century.

Running an empire on Bula time

Julius Caesar established the Julian calendar, in 46 BC. It was a reform of the Roman calendar, which was so complicated it had a committee to keep it in tune with the actual solar year. They would decide when to add or remove days, which made it hard to plan anything with precision. Caesar wanted a system that didn’t change from year to year, and he employed an astronomer to create a calendar based entirely on the length of time the earth takes to go around the sun.

What makes the calculation tricky is that this revolution isn’t an exact number of days. It takes, on average, 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes and 45 seconds for the earth to go around the sun. So Caesar’s astronomer hit on the idea of a 365 day year, with an extra day in February every four years.

A Feast day in Spring

As it turned out, a day every four years is too many, and by the sixteenth century, one of the most important feast days of the church — Easter — was in danger of losing its (Northern hemisphere) connection to Spring. Pope Gregory XIII hired an Italian scientist to fix the problem. Aloysus Lilius devised the variation we use today. In the Gregorian calculation, we add a leap day if the year can be divided by four, but not if it can also be divided by 100. However, if the year can also be divided by 400, in goes the leap day.

It isn’t perfect. In another 2,000 years, we’ll be a day out again. But it’s a lot closer.

No Papists messing with our calendar!

Pope Gregory’s reform took effect as soon as his proclamation went out, not only establishing the new system but making a one-off change — a jump of more than a week — to realign the dates with the seasons.

Italy, Spain, Portugal, and other Catholic countries all adopted the new calendar. European Protestants, however, saw the change as some kind of a plot, and refused to have anything to do with it. But one by one in the eighteenth century, common sense, trade, and political links prevailed.

No messing with our tax year!

Many of the German states switched early in the century. England changed in September 1752. The Calendar Act (an Act for Regulating the Commencement of the Year and for Correcting the Calendar now in Use) was introduced in 1751, passed through Parliament, and was signed into law in May 1752. Not only did it provide for 2nd September 1752 to be followed by 14th September 1752, but it also moved New Year’s Day from 25th March to 1st January. The previous New Year’s Day was the Feast of the Annunciation, and so Lady’s Day, and traditionally the day for paying taxes and rents. Changing the date of the tax payment would have shorted that tax year, so while the calendar year now started on January 1st, the start of the financial year remained as 5th April, or 25th March under the Julian Calendar. It was changed to 6th April in 1800 (which would have been a leap year under the Julian, but wasn’t), and 6th April it remains in Britain to this day.

The rioting was probably a myth

People were upset about the change, fearing that the government was taking 11 days off their lives. But the story that there were riots is not borne out by newspapers and other contemporary accounts. Possibly it comes from the Hogarth painting of an election meeting, shown above. The calendar reform was an election campaign topic in 1754, and the painting shows a demonstration outside the window. You can just see a sign saying ‘Give us our 11 days’.