R. Scott Bakker's Blog, page 25

January 23, 2013

Zizek, Hollywood, and the Disenchantment of Continental Philosophy

Aphorism of the Day: At least a flamingo has a leg to stand on.

.

Back in the 1990′s whenever I mentioned Dennett and the significance of neuroscience to my Continental buddies I would usually get some version of ‘Why do you bother reading that shite?’ I would be told something about the ontological priority of the lifeworld or the practical priority of the normative: more than once I was referred to Hegel’s critique of phrenology in the Phenomenology.

The upshot was that the intentional has to be irreducible. Of course this ‘has to be’ ostensibly turned on some longwinded argument (picked out of the great mountain of longwinded arguments), but I couldn’t shake the suspicion that the intentional had to be irreducible because the intentional had to come first, and the intentional had to come first because ‘intentional cognition’ was the philosopher’s stock and trade–and oh-my, how we adore coming first.

Back then I chalked up this resistance to a strategic failure of imagination. A stupendous amount of work goes into building an academic philosophy career; given our predisposition to rationalize even our most petty acts, the chances of seeing our way past our life’s work are pretty damn slim! One of the things that makes science so powerful is the way it takes that particular task out of the institutional participant’s hands–enough to revolutionize the world at least. Not so in philosophy, as any gas station attendant can tell you.

I certainly understood the sheer intuitive force of what I was arguing against. I quite regularly find the things I argue here almost impossible to believe. I don’t so much believe as fear that the Blind Brain Theory is true. What I do believe is that some kind of radical overturning of noocentrism is not only possible, but probable, and that the 99% of philosophers who have closed ranks against this possibility will likely find themselves in the ignominious position of those philosophers who once defended geocentrism and biocentrism.

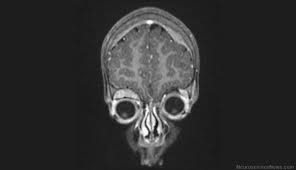

What I’ve recently come to appreciate, however, is that I am literally, as opposed to figuratively, arguing against a form of anosognosia, that I’m pushing brains places they cannot go–short of imagination. Visual illusions are one thing. Spike a signal this way or that, trip up the predictive processing, and you have a little visual aporia, an isolated area of optic nonsense in an otherwise visually ‘rational’ world. The kinds of neglect-driven illusions I’m referring to, however, outrun us, as they have to, insofar as we are them in some strange sense.

So here we are in 2013, and there’s more than enough neuroscientific writing on the wall to have captured even the most insensate Continental philosopher’s attention. People are picking through the great mountain of longwinded arguments once again, tinkering, retooling, now that the extent of the threat has become clear. Things are getting serious; the akratic social consequences I depicted in Neuropath are everywhere becoming more evident. The interval between knowledge and experience is beginning to gape. Ignoring the problem now smacks more of negligence than insouciant conviction. The soul, many are now convinced, must be philosophically defended. Thought, whatever it is, must be mobilized against its dissolution.

The question is how.

My own position might be summarized as a kind of ‘Good-Luck-Chuck’ argument. Either you posit an occult brand of reality special to you and go join the Christians in their churches, or you own up to the inevitable. The fate of the transcendental lies in empirical hands now. There is no way, short of begging the question against science, of securing the transcendental against the empirical. Imagine you come up with, say, Argument A, which concludes on non-empirical Ground X that intentionality cannot be a ‘cognitive illusion.’ The problem, obviously, is that Argument A can only take it on faith that no future neuroscience will revise or eliminate its interpretation of Ground X. And that faith, like most faith, only comes easy in the absence of alternatives–of imagination.

The notion of using transcendental speculation to foreclose on possible empirical findings is hopeless. Speculation is too unreliable and nature is too fraught with surprises. One of the things that makes the Blind Brain Theory so important, I think, is the way its mere existence reveals this new thetic landscape. By deriving the signature characteristics of the first-personal out of the mechanical, it provides a kind of ‘proof of concept,’ a demonstration that post-intentional theory is not only possible, but potentially powerful. As a viable alternative to intentional thought (of which transcendental philosophy is a subset), it has the effect of dispelling the ‘only game in town illusion,’ the sense of necessity that accompanies every failure of philosophical imagination. It forces ‘has to be’ down to the level of ‘might be’…

You could say the mere possibility that the Blind Brain Theory might be empirically verified drags the whole of Continental philosophy into the purview of science. The most the Continental philosopher can do is match their intentional hopes against my mechanistic fears. Put simply, the grand old philosophical question of what we are no longer belongs to them: It has fallen to science.

.

For better and for worse, Metzinger’s Being No One has become the textual locus of the ‘neuroscientific threat’ in Continental circles. His thesis alone would have brought him to attention, I’m sure. That aside, the care, scholarship, and insight he brings to the topic provide the Continental reader with a quite extraordinary (and perhaps too flattering) introduction to cognitive science and Anglo-American philosophy of mind as it stood a decade or so ago.

The problem with Being No One, however, is precisely what renders it so attractive to Continentalists, particularly those invested in the so-called ‘materialist turn’: rather than consider the problem of meaning tout court, it considers the far more topical problem of the self or subject. In this sense, it is thematically continuous with the concerns of much Continental philosophy, particularly in its post-structuralist and psychoanalytic incarnations. It allows the Continentalist, in other words, to handle the ‘neuroscientific threat’ in a diminished and domesticated form, which is to say, as the hoary old problem of the subject. Several people have told me now that the questions raised by the sciences of the brain are ‘nothing new,’ that they simply bear out what this or that philosophical/psychoanalytic figure has said long ago–that the radicality of neuroscience is not all that ‘radical’ at all. Typically, I take the opportunity to ask questions they cannot answer.

Zizek’s reading of Metzinger in The Parallax View, for instance, clearly demonstrates the way some Continentalists regard the sciences of the brain as an empirical mirror wherein they can admire their transcendental hair. For someone like Zizek, who has made a career out of avoiding combs and brushes, Being No One proves to be one the few texts able to focus and hold his rampant attention, the one point where his concern seems to outrun his often brutish zest for ironic and paradoxical formulations. In his reading, Zizek immediately homes in on those aspects of Metzinger’s theory that most closely parallel my view (the very passages that inspired me to contact Thomas years ago, in fact) where Metzinger discusses the relationship between the transparency of the Phenomenal Self-Model (PSM) and the occlusion of the neurofunctionality that renders it. The self, on Metzinger’s account, is a model that cannot conceive itself as a model; it suffers from what he calls ‘autoepistemic closure,’ a constitutive lack of information access (BNO, 338). And its apparent transparency accordingly becomes “a special form of darkness” (BNO, 169).

This is where Metzinger’s account almost completely dovetails with Zizek’s own notion of the subject, and so holds the most glister for him. But he defers pressing this argument and turns to the conclusion of Being No One, where Metzinger, in an attempt to redeem the Enlightenment ethos, characterizes the loss of self as a gain in autonomy, insofar as scientific knowledge allows us to “grow up,” and escape the ‘tutelary nature’ of our own brain. Zizek only returns to the lessons he finds in Metzinger after a reading of Damasio’s rather hamfisted treatment of consciousness in Descartes’ Error, as well as a desultory and idiosyncratic (which, as my daughter would put it, is a fancy way of saying ‘mistaken’) reading of Dennett’s critique of the Cartesian Theater. Part of the problem he faces is that Metzinger’s PSM, as structurally amenable as it is to his thesis, remains too topical for his argument. The self simply does not exhaust consciousness (even though Metzinger himself often conflates the two in Being No One). Saying there is no such thing as selves is not the same as saying there is no such thing as consciousness. And as his preoccupation with the explanatory gap and cognitive closure makes clear, nothing less than the ontological redefinition of consciousness itself is Zizek’s primary target. Damasio and Dennett provide the material (as well as the textual distance) he requires to expand the structure he isolates in Metzinger. As he writes:

Are we free only insofar as we misrecognize the causes which determine us? The mistake of the identification of (self-)consciousness with misrecognition, with an epistemological obstacle, is that it stealthily (re)introduces the standard, premodern, “cosmological” notion of reality as a positive order of being: in such a fully constituted positive “chain of being” there is, of course, no place for the subject, so the dimension of subjectivity can be conceived of only as something which is strictly co-dependent with the epistemological misrecognition of the positive order of being. Consequently, the only way effectively to account for the status of (self-)consciousness is to assert the ontological incompleteness of “reality” itself: there is “reality” only insofar as there is an ontological gap, a crack, in its very heart, that is to say, a traumatic excess, a foreign body which cannot be integrated into it. This brings us back to the notion of the “Night of the World”: in this momentary suspension of the positive order of reality, we confront the ontological gap on account of which “reality” is never a complete, self-enclosed, positive order of being. It is only this experience of psychotic withdrawal from reality, of absolute self-contraction, which accounts for the mysterious “fact” of transcendental freedom: for a (self-)consciousness which is in effect “spontaneous,” whose spontaneity is not an effect of misrecognition of some “objective” process. 241-242

For those with a background in Continental philosophy, this ‘aporetic’ discursive mode is more than familiar. What I find so interesting about this particular passage is the way it actually attempts to distill the magic of autonomy, to identify where and how the impossibility of freedom becomes its necessity. To identify consciousness as an illusion, he claims, is to presuppose that the real is positive, hierarchical, and whole. Since the mental does not ‘fit’ with this whole, and the whole, by definition, is all there is, it must then be some kind of misrecognition of that whole–‘mind’ becomes the brain’s misrecognition of itself as a brain. Brain blindness. The alternative, Zizek argues, is to assume that the whole has a hole, that reality is radically incomplete, and so transform what was epistemological misrecognition into ontological incompleteness. Consciousness can then be seen as a kind of void (as opposed to blindness), thus allowing for the reflexive spontaneity so crucial to the normative.

In keeping with his loose usage of concepts from the philosophy of mind, Zizek wants to relocate the explanatory gap between mind and brain into the former, to argue that the epistemological problem of understanding consciousness is in fact ontologically constitutive of consciousness. What is consciousness? The subjective hole in the material whole.

[T]here is, of course, no substantial signified content which guarantees the unity of the I; at this level, the subject is multiple, dispersed, and so forth—its unity is guaranteed only by the self-referential symbolic act, that is,”I” is a purely performative entity, it is the one who says “I.” This is the mystery of the subject’s “self-positing,” explored by Fichte: of course, when I say “I,” I do not create any new content, I merely designate myself, the person who is uttering the phrase. This self-designation nonetheless gives rise to (“posits”) an X which is not the “real” flesh-and-blood person uttering it, but, precisely and merely, the pure Void of self-referential designation (the Lacanian “subject of the enunciation”): “I” am not directly my body, or even the content of my mind; “I” am, rather, that X which has all these features as its properties. 244-245

Now I’m no Zizek scholar, and I welcome corrections on this interpretation from those better read than I. At the same time I shudder to think what a stolid, hotdog-eating philosopher-of-mind would make of this ontologization of the explanatory gap. Personally, I lack Zizek’s faith in theory: the fact of human theoretical incompetence inclines me to bet on the epistemological over the ontological most every time. Zizek can’t have it both ways. He can’t say consciousness is ‘the inexplicable’ without explaining it as such.

Either way, this clearly amounts to yet another attempt to espouse a kind of naturalism without transcendental tears. Like Brassier in “The View from Nowhere,” Zizek is offering an account of subjectivity without self. Unlike Brassier, however, he seems to be oblivious to what I have previously called the Intentional Dissociation Problem: he never considers how the very issues that lead Metzinger to label the self hallucinatory also pertain to intentionality more generally. Certainly, the whole of The Parallax View is putatively given over to the problem of meaning as the problem of the relationship between thought/meaning and being/truth, or the problem of the ‘gap’ as Zizek puts it. And yet, throughout the text, the efficacy (and therefore the reality) of meaning–or thought–is never once doubted, nor is the possibility of the post-intentional considered. Much of his discussion of Dennett, for instance, turns on Dennett’s intentional apologetics, his attempt to avoid, among other things, the propositional-attitudinal eliminativism of Paul Churchland (to whom Zizek mistakenly attributes Dennett’s qualia eliminativism (PV, 177)). But where Dennett clearly sees the peril, the threat of nihilism, Zizek only sees an intellectual challenge. For Zizek, the question, Is meaning real? is ultimately a rhetorical one, and the dire challenge emerging out of the sciences of the brain amount to little more than a theoretical occasion.

So in the passage quoted above, the person (subject) is plucked from the subpersonal legion via “the self-referential symbolic act.” The problems and questions that threaten to explode this formulation are numerous, to say the least. The attraction, however, is obvious: It apparently allows Zizek, much like Kant, to isolate a moment within mechanism that nevertheless stands outside of mechanism short of entailing some secondary order of being–an untenable dualism. In this way it provides ‘freedom’ without any incipient supernaturalism, and thus grounds the possibility of meaning.

But like other forms of deflationary transcendentalism, this picture simply begs the question. The cognitive scientist need only ask, What is this ‘self-referential symbolic act’? and the circular penury of Zizek’s position is revealed: How can an act of meaning ground the possibility of meaningful acts? The vicious circularity is so obvious that one might wonder how a thinker as subtle as Zizek could run afoul it. But then, you must first realize (as, say, Dennett realizes) the way intentionality as a whole, and not simply the ‘person,’ is threatened by the mechanistic paradigm of the life sciences. So for instance, Zizek repeatedly invokes the old Derridean trope of bricolage. But there’s ‘bricolage’ and then there’s bricolage: there’s fragments that form happy fragmentary wholes that readily lend themselves to the formation of new functional assemblages, ‘deconstructive ethics,’ say, and then there’s fragments that are irredeemably fragmentary, whose dimensions of fragmentation are such that they can only be misconceived as wholes. Zizek seizes on Metzinger’s account of the self in Being No One precisely because it lends itself to the former, ‘happy’ bricolage, one where we need only fear for the self and not the intentionality that constitutes it.

The Blind Brain Theory, however, paints a far different portrait of ‘selfhood’ than Metzinger’s PSM, one that not only makes hash of Zizek’s thesis, but actually explains the cognitive errors that motivate it. On Metzinger’s account, ‘auto-epistemic closure’ (or the ‘darkness of transparency’) is the primary structural principle that undermines the ‘reality’ of the PSM and the PSM only. The Blind Brain Theory, on the other hand, casts the net wider. Constraints on the information broadcast or integrated are crucial, to be sure, but BBT also considers the way these constraints impact the fractionate cognitive systems that ‘solve’ them. On my view, there is no ‘phenomenal self-model,’ only congeries of heuristic cognitive systems primarily adapted to environmental cognition (including social environmental cognition) cobbling together what they can given what little information they receive. For Metzinger, who remains bound to the ‘Accomplishment Assumption’ that characterizes the sciences of the brain more generally, the cognitive error is one of mistaking a low-dimensional simulation for a reality. The phenomenal self-model, for him, really is something like ‘a flight-simulator that contains its own exits.’

On BBT, however, there is no one error, nor even one coherent system of errors; instead there are any number of information shortfalls and cognitive misapplications leading to this or that form of reflective, acculturated forms of ‘selfness,’ be it ancient Greek, Cartesian, post-structural, or what have you. Selfness, in other words, is the product of compound misapprehensions, both at the assumptive and the theoretical levels (or better put, across the spectrum of deliberative metacognition, from the cursory/pragmatic to the systematic/theoretical).

BBT uses these misconstruals, myopias, and blindnesses to explain the ways intentionality and phenomenality confound the ‘third-person’ mechanistic paradigm of the life sciences. It can explain, in other words, many of the ‘structural’ peculiarities that make the first-person so refractory to naturalization. It does this by interpreting those peculiarities as artifacts of ‘lost dimensions’ of information, particularly with reference to medial neglect. So for instance, our intuition of aboutness derives from the brain’s inability to model its modelling, neglecting, as it must, the neurofunctionality responsible for modelling its distal environments. Thus the peculiar ‘bottomlessness’ of conscious cognition and experience, the way each subsequent moment somehow becomes ground of the moment previous (and all the foundational paradoxes that have arisen from this structure). Thus the metacognitive transformation of asymptotic covariance into ‘aboutness,’ a relation absent the relation.

And so it continues: Our intuition of conscious unity arises from the way cognition confuses aggregates for individuals in the absence of differentiating information. Our intuition of personal identity (and nowness more generally) arises from metacognitive neglect of second-order temporalization, our brain’s blindness to the self-differentiating time of timing. For whatever reason, consciousness is integrative: oscillating sounds and lights ‘fuse’ or appear continuous beyond certain frequency thresholds because information that doesn’t reach consciousness makes no conscious difference. Thus the eerie first-person that neglect hacks from a much higher dimensional third can be said to be inevitable. One need only apply the logic of flicker-fusion to consciousness as a whole, ask why, for instance, facets of conscious experience such as unity or presence require specialized ‘unification devices’ or ‘now mechanisms’ to accomplish what can be explained as perceptual/cognitive errors in conditions of informatic privation. Certainly it isn’t merely a coincidence that all the concepts and phenomena incompatible with mechanism involve drastic reductions in dimensionality.

In explaining away intentionality, personal identity, and presence, BBT inadvertently explains why we intuit the subject we think we do. It sets the basic neurofunctional ‘boundary conditions’ within which Sellars’ manifest image is culturally elaborated–the boundary conditions of intentional philosophy, in effect. In doing so, it provides a means of doing what the Continental tradition, even in its most recent, quasi-materialist incarnations, has regarded as impossible: naturalizing the transcendental, whether in its florid, traditional forms or in its contemporary deflationary guises–including Zizek’s supposedly ineliminable remainder, his subject as ‘gap.’

And this is just to say that BBT, in explaining away the first-person, also explains away Continental philosophy.

Few would argue that many of the ‘conditions of possibility’ that comprise the ‘thick transcendental’ account of Kant, for instance, amount to speculative interpretations of occluded brain functions insofar as they amount to interpretations of anything at all. After all, this is a primary motive for the retreat into ‘materialism’ (a position, as we shall see, that BBT endorses no more than ‘idealism’). But what remains difficult, even apparently impossible, to square with the natural is the question of the transcendental simpliciter. Sure, one might argue, Kant may have been wrong about the transcendental, but surely his great insight was to glimpse the transcendental as such. But this is precisely what BBT and medial neglect allows us to explain: the way the informatic and heuristic constraints on metacognition produce the asymptotic–acausal or ‘bottomless’–structure of conscious experience. The ‘transcendental’ on this view is a kind of ‘perspectival illusion,’ a hallucinatory artifact of the way information pertaining to the limits of any momentary conscious experience can only be integrated in subsequent moments of conscious experience.

Kant’s genius, his discovery, or at least what enabled his account to appeal to the metacognitive intuitions of so many across the ages, lay in making-explicit the occluded medial axis of consciousness, the fact that some kind of orthogonal functionality (neural, we now know) haunts empirical experience. Of course Hume had already guessed as much, but lacking the systematic, dogmatic impulse of his Prussian successor, he had glimpsed only murk and confusion, and a self that could only be chased into the oblivion of the ‘merely verbal’ by honest self-reflection.

Brassier, as we have seen, opts for the epistemic humility of the Humean route, and seeks to retrieve the rational via the ‘merely verbal.’ Zizek, though he makes gestures in this direction, ultimately seizes on a radical deflation of the Kantian route. Where Hume declines the temptation of hanging his ‘merely verbal’ across any ontological guesses, Zizek positions his ‘self-referential symbolic act’ within the ‘Void of pure designation,’ which is to say, the ‘void’ of itself, thus literally construing the subject as some kind of ‘self-interpreting rule’–or better, ‘self-constituting form’–the point where spontaneity and freedom become at least possible.

But again, there’s ‘void,’ the one that somehow magically anchors meaning, an then there’s, well, void. According to BBT, Zizek’s formulation is but one of many ways deliberative metacognition, relying on woefully depleted and truncated information and (mis)applying cognitive tools adapted to distal social and natural environments, can make sense of its own asymptotic limits: by transforming itself into the condition of itself. As should be apparent, the genius of Zizek’s account is entirely strategic. The bootstrapping conceit of subjectivity is preserved in a manner that allows Zizek to affirm the tyranny of the material (being, truth) without apparent contradiction. The minimization of overt ontological commitments, meanwhile, lends a kind of theoretical immunity to traditional critique.

There is no ‘void of pure designation’ because there is no ‘void’ any more than there is ‘pure designation.’ The information broadcast or integrated in conscious experience is finite, thus generating the plurality of asymptotic horizons that carve the hallucinatory architecture of the first-person from the astronomical complexities of our brain-environment. These broadcast or integration limits are a real empirical phenomenon that simply follow from the finite nature of conscious experience. Of BBT’s many empirical claims, these ‘information horizons’ are almost certain to be scientifically vindicated. Given these limits, the question of how they are expressed in conscious experience becomes unavoidable. The interpretations I’ve so far offered are no doubt little more than an initial assay into what will prove a massive undertaking. Once they are taken into account, however, it becomes difficult not to see Zizek’s ‘deflationary transcendental’ as simply one way for a fractionate metacognition to make sense of these limits: unitary because the absence of information is the absence of differentiation, reflexive because the lack of medial temporal information generates the metacognitive illusion of medial timelessness, and referential because the lack of medial functional information generates the metacognitive illusion of afunctional relationality, or intentional ‘aboutness.’

Thus we might speak of the ‘Zizek Fallacy,’ the faux affirmation of a materialism that nevertheless spares just enough of the transcendental to anchor the intentional…

A thread from which to dangle the prescientific tradition.

.

So does this mean that BBT offers the only ‘true’ route from intentionality to materialism. Not at all.

BBT takes the third-person brain as the ‘rule’ of the first-person mind simply because, thus far at least, science provides the only reliable form of theoretical cognition we know. Thus it would seem to be ‘materialist,’ insofar as it makes the body the measure of the soul. But what BBT shows–or better, hypothesizes–is that this dualism between mind and brain, ideal and real, is itself a heuristic artifact. Given medial neglect, the brain can only model its relation to its environment absent any informatic access to that relation. In other words, the ‘problem’ of its relation to distal environments is one that it can only solve absent tremendous amounts of information. The very structure of the brain, in other words, the fact that the machinery of predictive modelling cannot itself be modelled, prevents it, at a certain level at least, from being a universal problem solver. The brain is itself a heuristic cognitive tool, a system adapted to the solution of particular ‘problems.’ Given neglect, however, it has no way of cognizing its limits, and so regularly takes itself to be omni-applicable.

The heuristic structure of the brain and the cognitive limits this entails are nowhere more evident than in its attempts to cognize itself. So long as the medial mechanisms that underwrite the predictive modelling of distal environments in no way interfere with the environmental systems modelled–or put differently, so long as the systems modelled remain functionally independent of the modelling functions–then medial neglect need not generate problems. When the systems modelled are functionally entangled with medial modelling functions, however, one should expect any number of ‘interference effects’ culminating in the abject inability to predictively model those systems. We find this problem of functional entanglement distally where the systems to be modelled are so delicate that our instrumentation causes ‘observation effects’ that render predictive modelling impossible, and proximally where the systems to be modelled belong to the brain that is modelling. And indeed, as I’ve argued in a number of previous posts, many of the problems confronting the philosophy of mind can be diagnosed in terms of this fundamental misapplication of the ‘Aboutness Heuristic.’

This is where post-intentionalism reveals an entirely new dimension of radicality, one that allows us to identify the metaphysical categories of the ‘material’ and the ‘formal’ (yes, I said, formal) for the heuristic cartoons they are. BBT allows us to finally see what we ‘see’ as subreptive artifacts of our inability to see, as low-dimensional shreds of abyssal complexities. It provides a view where not only can the tradition be diagnosed and explained away, but where the fundamental dichotomies and categories, hitherto assumed inescapable, dissolve into the higher dimensional models that only brains collectively organized into superordinate heuristic mechanisms via the institutional practices of science can realize. Mind? Matter? These are simply waystations on an informatic continuum, ‘concepts’ according to the low-dimensional distortions of the first-person and mechanisms according to the third: concrete, irreflexive, high-dimensional processes that integrate our organism–and therefore us–as componential moments of the incomprehensibly vast mechanism of the universe. Where the tradition attempts, in vain, to explain our perplexing role in this natural picture via a series of extraordinary additions, everything from the immortal soul to happy emergence to Zizek’s fortuitous ‘void,’ BBT merely proposes a network of mundane privations, arguing that the self-congratulatory consciousness we have tasked science with explaining simply does not exist…

That the ‘Hard Problem’ is really one of preserving our last and most cherished set of self-aggrandizing conceits.

It is against this greater canvas that we can clearly see the parochialism of Zizek’s approach, how he remains (despite his ‘merely verbal’ commitment to ‘materialism’) firmly trapped within the hallucinatory ‘parallax’ of intentionality, and so essentializes the (apparently not so) ‘blind spot’ that plays such an important role in the system of conceptual fetishes he sets in motion. It has become fashion in certain circles to impugn ‘correlation’ in an attempt to think being in a manner that surpasses the relation between thought and being. This gives voice to an old hankering in Continental philosophy, the genuinely shrewd suspicion that something is wrong with the traditional, understanding of human cognition. But rather than answer the skepticism that falls out of Hume’s account of human nature or Wittgenstein’s consideration of human normativity, the absurd assumption has been that one can simply think their way beyond the constraints of thought, simply reach out and somehow snatch ‘knowledge at a spooky distance.’ The poverty of this assumption lies in the most honest of all questions: ‘How do you know?’ given that (as Hume taught us) you are a human and so cursed with human cognitive frailties, given that (as Wittgenstein taught us) you are a language-user and so belong to normative communities.

‘Correlation’ is little more than a gimmick, the residue of a magical thinking that assumes naming a thing gives one power over it. It is meant to obscure far more than enlighten, to covertly conserve the Continental tradition of placing the subject on the altar of career-friendly critique, lest the actual problem–intentionality–stir from its slumber and devour twenty-five centuries of prescientific conceit and myopia. The call to think being precritically, which is to say, without thinking the relation of thought and being, amounts to little more than an conceptually atavistic stunt so long as Hume and Wittgenstein’s questions remain unanswered.

The post-intentional philosophy that follows from BBT, however, belongs to the self-same skeptical tradition of disclosing the contextual contingencies that constrain thought’s attempt to cognize being. As opposed to the brute desperation of simply ignoring subjectivity or normativity, it seizes upon them. Intentional concepts and phenomena, it argues, exhibit precisely the acausal ‘bottomlessness’ that medial neglect, a structural inevitability given a mechanistic understanding of the brain, forces on metacognition. A great number of powerful and profound illusions result, illusions that you confuse for yourself. You think you are more a system of levers rather than a tangle of wiretaps. You think that understanding is yours. The low-dimensional cartoon of you standing within and apart from an object world is just that, a low-dimensional cartoon, a surrogate, facile and deceptive, for the high-dimensional facts of the brain-environment.

Thus is the problem of so-called ‘correlation’ solved, not by naming, shaming, and ersatz declaration, but rather by passing through the problematic, by understanding that the ‘subjective’ and the ‘normative’ are themselves natural and therefore amenable to scientific investigation. BBT explains the artifactual nature of the apparently inescapable correlation of thought and being, how medial neglect strands metacognition with an inexplicable covariance that it must conceive otherwise–in supra-natural terms. And it allows one to set aside the intentional conundrums of philosophy for what they are: arguments regarding interpretations of cognitive illusions.

Why assume the ‘design stance,’ given that it turns on informatic neglect? Why not regularly regard others in subpersonal terms, as mechanisms, when it strikes ‘you’ as advantageous? Or, more troubling still, is this simply coming to terms with what you have been doing all along? The ‘pragmatism’ once monopolized by ‘taking the intentional stance’ no longer obtains. For all we know, we could be more a confabulatory interface than anything, an informatic symbiont or parasite–our ‘consciousness’ a kind of tapeworm in the gut of the holy neural host. It could be this bad–worse. Corporate advertisers are beginning to think as much. And as I mentioned above, this is where the full inferential virulence of BBT stands revealed: it merely has to be plausible to demonstrate that anything could be the case.

And the happy possibilities are drastically outnumbered.

As for the question, ‘How do you know?’ BBT cheerfully admits that it does not, that it is every bit as speculative as any of its competitors. It holds forth its parsimonious explanatory reach, the way it can systematically resolve numerous ancient perplexities using only a handful of insights, as evidence of its advantage, as well as the fact that it is ultimately empirical, and so awaits scientific arbitration. BBT, unlike ‘OOO’ for instance, will stand or fall on the findings of cognitive science, rather than fade as all such transcendental positions fade on the tide of academic fashion.

And, perhaps most importantly, it is timely. As the brain becomes ever more tractable to science, the more antiquated and absurd prescientific discourses of the soul will become. It is folly to think that one’s own discourse is ‘special,’ that it will be the first prescientific discourse in history to be redeemed rather than relegated or replaced by the findings of science. What cognitive science discovers over the next century will almost certainly ruin or revolutionize fairly everything that has been assumed regarding the soul. BBT is mere speculation, yes, but mere speculation that turns on the most recent science and remains answerable to the science that will come. And given that science is the transformative engine of what is without any doubt the most transformative epoch in human history, BBT provides a means to diagnose and to prognosticate what is happening to us now–even going so far as to warn that intentionality will not constrain the posthuman.

What it does not provide is any redeeming means to assess or to guide. The post-intentional holds no consolation. When rules become regularities, nothing pretty can come of life. It is an ugly, even horrifying, conclusion, suggesting, as it does, that what we hold the most sacred and profound is little more than a subreptive by-product of evolutionary indifference. And even in this, the relentless manner in which it explodes and eviscerates our conceptual conceits, it distinguishes itself from its soft-bellied competitors. It simply follows the track of its machinations, the algorithmic grub of ‘reason.’ It has no truck with flattering assumptions.

And this is simply to say is that the Blind Brain Theory offers us a genuine way out, out of the old dichotomies, the old problems. It bids us to moult, to slough off transcendental philosophy like a dead serpentine skin. It could very well achieve the dream of all philosophy–only at the cost of everything that matters.

And really. What else did you fucking expect? A happy ending? That life really would turn out to be ‘what we make it’?

Whatever the conclusion is, it ain’t going to be Hollywood.

January 21, 2013

The Toll

Aphorism of the Day: This? Yeah, well, dope smoke that, motherfucker.

.

I want to say I’m not quite sure what I’m doing anymore. But then I’m not sure what it means to say one is doing anything anymore. The reflexes seem to be in functioning order… Be witty. Be urbane. Charm those around you, and most importantly, impress. You never know… You never know…

These are the offerings we cast into the blackness–nowadays. This is what throws us on our bellies, what we burn. This is what it means to live in a world without bubbles of air, where the social has flooded the most ad hoc recess, the most hidden pocket. Always guarded. Always poised to be poised. Always polite, lest… who the fuck knows?

Bury that scream deep in the meat.

Look, it says. Just give it to me, whatever it is it wants.

You were never good at the game–or at least you rarely count yourself as such. If you were, it would be easy. And it’s anything but. You look at them wondering that you wonder, huddling about a spark of pedestrian superiority, the glee of seeing, the one that twist smiles into cramps, like toddlers hiding in plain view. What joy there is in deception!

Bury it.

Where is the agon? The strife? What you call ‘professionalism’ is prestidigitation, the absence of personality made indicator of truth–the faux voice of no one to cement a faux view from nowhere. The winnowing of idiosyncrasies as grace. Nowhere is the mania for standardization more noiselessly sublimated than in academia.

Life has become a conflict of machines: the stochastic wave of your nature, paleolithic consciousness shooting the translucent curl, versus the deterministic demands of a metastatic bureaucracy, forever punishing you for your margins of error.

And now look at you, weeping for reasons no one would care to admit.

Shush. Shush, you fool. The belly is full. The bowel voided.

Honesty has always been an angle.

Smile for the camera. No one can pretend not to be a politician anymore.

Set a great stone before the tomb.

I like talking to addicts. I like thinking I can see further, that I have some kind of wisdom to impart. I mourn the flutter of indecision, the wary squint, when something in my tone or vocabulary gives me away. I like learning the lingo, the names of things illegal. I like bullshitting about things that seem worth bullshitting about–though only at the time. I like to be the one that knows. I like that my life has been tragic, that I can stop strangers cold with my memories. And I find it strange, this inability to arbitrate between personas.

This is soul rotting stuff, this.

Philosophy sets you at odds with your origins as it is. It alienates and isolates you, especially when all seems convivial. Or maybe you’re ‘just-different-that-way.’ Maybe I’m ‘you-had-to-be-there’ like, all the way down.

But I doubt it.

To be a philosopher is to forever hold your tongue, watch what you say. They grow quiet around the turkey when you speak, out of forbearance, not interest or deference. They endure more than understand. They refuse more than fail to recognize your ‘expertise’–and how could they not, when it would relieve them of their humanity? To accord you authority would be to concede their right to judge and believe, to dare hold forth a world from their small corner.

How could they not despise? Lampoon your cartoonish pretension? And above all, how could they not distrust what you see?

All theory is megalomania, a crime against interpersonal proportion. Could you imagine actually telling them what you believe? That they are hapless, cretinized, duped, tyrannized by their purchase patterns, their stories, their comedians and body-mass-indices?

That they are the They? The hoi-fucking-polloi?

But then it cuts both ways, doesn’t it? Maybe you catch a glimpse of it, now again, the lunatic scale of your defection. The inkling of undergraduate condescension–of patience.

The knowledge that you would be murdered were this any other age hangs like implicit smoke about you.

If you are young, you’re still working through the consequences of what you are becoming. You still resent. You still primp and preen, declaim before make-shift worlds. You can still taste the transformation of frustrated pride into ingrown loathing. If you are not so young you have already learned to be wry and acerbic, to speak only to make the people around the turkey laugh or wonder. You find refuge in observation, and even manage to flatter yourself, on occasion, for your anthropological isolation. If you’re lucky, you recover joy in ways devious and orthogonal. You heap abuse upon what you have become as both lubricant and prophylactic. You imagine Zizek fucking groupies, wag your eyes at the circus that was once your passion.

You let mystery become the one simple. Perhaps find wisdom in exhaustion.

I’m not sure what I’m doing any more. What I’m writing or for whom, whether it’s important or outrageous or pathetic. I’ve never been a robust person. I’ve always been frail in ways that stoke a father’s outrage, enough to worry that I’m not a match for whatever it is–let alone this. Always faintly amazed that I have survived. And always driven.

All I know is that indulgences exact a toll.

Back when I was doing my PhD a friend of mine would walk his dog every night, one of those toy breeds that sound like rats when crossing hardwood floors. A classmate of ours, a solitary soul, happened to live a few doors down. He would see him through his patio doors every night, laying motionless on his couch watching the tube, soaked in erratic prints of white and blue. Every night. Passive. Watching. Wordless.

Never screaming.

And he would wonder about him. Theorize.

January 18, 2013

The Introspective Peepshow: Consciousness and the ‘Dreaded Unknown Unknowns’

Aphorism of the Day: That it feels so unnatural to conceive ourselves as natural is itself a decisive expression of our nature.

.

This is a paper I finished a couple of months back, my latest attempt to ease those with a more ‘analytic’ mindset into the upside-down madness of my views. It definitely requires a thorough rewrite, so if you see any problems, or have any questions, or simply see a more elegant way of getting from A to B, please sound off. As for the fixation with ‘show’ in my titles, I haven’t the foggiest!

Oh, yes, the Abstract:

“Evidence from the cognitive sciences increasingly suggests that introspection is unreliable – in some cases spectacularly so – in a number of respects, even though both philosophers and the ‘folk’ almost universally assume the complete opposite. This draft represents an attempt to explain this ‘introspective paradox’ in terms of the ‘unknown unknown,’ the curious way the absence of explicit information pertaining to the reliability of introspectively accessed information leads to the implicit assumption of reliability. The brain is not only blind to its inner workings, it’s blind to this blindness, and therefore assumes that it sees everything there is to see. In a sense, we are all ‘natural anosognosiacs,’ a fact that could very well explain why we find the consciousness we think we have so difficult to explain.”

More generally I want to apologize for neglecting the comments of late. Routine is my lifeblood, and I’m just getting things back online after a particularly ‘noro-chaotic’ holiday. The more boring my life is, the more excited I become.

January 8, 2013

Brassier’s Divided Soul

Aphorism of the Day: If science is the Priest and nature is the Holy Spirit, then you, my unfortunate friend, are Linda Blair.

.

And Jesus asked him, “What is your name?” He replied, “My name is Legion, for we are many.” - Mark 5:9

.

For decades now the Cartesian subject–whole, autonomous and diaphanous–has been the whipping-boy of innumerable critiques turning on the difficulties that beset our intuitive assumptions of metacognitive sufficiency. A great many continental philosophers and theorists more generally consider it the canonical ‘Problematic Ontological Assumption,’ the conceptual ‘wrong turn’ underwriting any number of theoretical confusions and social injustices. Thinkers across the humanities regularly dismiss whole theoretical traditions on the basis of some perceived commitment to Cartesian subjectivity.

My long time complaint with this approach lies in its opportunism. I entirely agree that the ‘person’ as we intuit it is ‘illusory’ (understood in some post-intentional sense). What I’ve never been able to understand, especially given post-structuralism’s explicit commitment to radical contextualism, was the systematic failure to think through the systematic consequences of this claim. To put the matter bluntly: if Descartes’ metacognitive subject is ‘broken,’ an insufficient fragment confused for a sufficient whole, then how do we know that everything subjective isn’t likewise broken?

The real challenge, as the ‘scientistic’ eliminativism of someone like Alex Rosenburg makes clear, is not so much one of preserving sufficient subjectivity as it is one of preserving sufficient intentionality more generally. The reason the continental tradition first lost faith with the Cartesian and Kantian attempts to hang the possibility of intentional cognition from a subjective hook is easy enough to see from a cognitive scientific standpoint. Nietzsche’s ‘It thinks’ is more than pithy, just as his invocation of the physiological is more than metaphorical. The more we learn about what we actually do, let alone how we are made, the more fractionate the natural picture–or what Sellars famously called the ‘scientific image’–of the human becomes. We, quite simply, are legion. The sufficient subject, in other words, is easily broken because it is the most egregious illusion.

But it is by no means the only one. The entire bestiary of the ‘subjective’ is on the examination table, and there’s no turning back. The diabolical possibility has become fact.

Let’s call this the ‘Intentional Dissociation Problem,’ the problem of jettisoning the traditional metacognitive subject (person, mind, consciousness, being-in-the-world) while retaining some kind of traditional metacognitive intentionality–the sense-making architecture of the ‘life-world’–that goes with it. The stakes of this problem are such, I would argue, that you can literally use it to divide our philosophical present from our past. In a sense, one can forgive the naivete of the 20th century critique of the subject simply because (with the marvellous exception of Nietzsche) it had no inkling of the mad cognitive scientific findings confronting us. What is willful ignorance or bad faith for us was simply innocence for our teachers.

It is Wittgenstein, perhaps not surprisingly, who gives us the most elegant rendition of the problem, when he notes, almost in passing (see Tractatus, 5.542), the way so-called propositional attitudes such as desires and beliefs only make sense when attributed to whole persons as opposed to subpersonal composites. Say that Scott believes p, desires p, enacts p, and is held responsible for believing, desiring, and enacting. One night he murders his neighbour Rupert, shouting that he believes him a threat to his family and desires to keep his family safe. Scott is, one would presume, obviously guilty. But afterward, Scott declares he remembers only dreaming of the murder, and that while awake he has only loved and respected Rupert, and couldn’t imagine committing such a heinous act. Subsequent research reveals that Scott suffers from somnambulism, the kind associated with ‘homicidal sleepwalking’ in particular, such that his brain continually tries to jump from slow-wave sleep to wakefulness, and often finds itself trapped between with various subpersonal mechanisms running on ‘wake mode’ while others remain in ‘sleep mode.’ ‘Whole Scott’ suddenly becomes ‘composite Scott,’ an entity that clearly should not be held responsible for the murder of his neighbour Rupert. Thankfully, our legal system is progressive enough to take the science into account and see justice is done.

The problem, however, is that we are fast approaching the day where any scenario where Scott murders Rupert could be parsed in subpersonal terms and diagnosed as a kind of ‘malfunction.’ If you have any recent experience teaching public school you are literally living this process of ‘subpersonalization’ on a daily basis, where more and more the kinds of character judgements that you would thoughtlessly make even a decade or so ago are becoming inappropriate. Try calling a kid with ADHD ‘lazy and irresponsible,’ and you have identified yourself as lazy and irresponsible. High profile thinkers like Dennett and Pinker have the troubling tendency of falling back on question-begging pragmatic tropes when considering this ‘spectre of creeping exculpation’ (as Dennett famously terms it in Freedom Evolves). In How the Mind Works, for instance, Pinker claims “that science and ethics are two self-contained systems played out among the same entities in the world, just as poker and bridge are different games played with the same fifty-two-card deck” (55)–even though the problem is precisely that these two systems are anything but ‘self-contained.’ Certainly it once seemed this way, but only so long as science remained stymied by the material complexities of the soul. Now we find ourselves confronted by an accelerating galaxy of real world examples where we think we’re playing personal bridge, only to find ourselves trumped by an ever-expanding repertoire of subpersonal poker hands.

The Intentional DissociationProblem, in other words, is not some mere ‘philosophical abstraction;’ it is part and parcel of an implacable science-and-capital driven process of fundamental subpersonalization that is engulfing society as we speak. Any philosophy that ignores it, or worse yet, pretends to have found a way around it, is Laputan in the most damning sense. (It testifies, I think, to the way contemporary ‘higher education’ has bureaucratized the tyranny of the past, that at such a time a call to arms has to be made at all… Or maybe I’m just channelling my inner Jeremiah–again!)

In continental circles, the distinction of recognizing both the subtlety and the severity of the Intentional Dissociation Problem belongs to Ray Brassier, one of but a handful of contemporary thinkers I know of who’ve managed to turn their back on the apologetic impulse and commit themselves to following reason no matter where it leads–to thinking through the implications of an institutionalized science truly indifferent to human aspiration, let alone conceit. In his recent “The View from Nowhere,” Brassier takes as his task precisely the question of whether rationality, understood in the Sellarsian sense as the ‘game of giving and asking for reasons,’ can survive the neuroscientific dismantling of the ontological self as theorized in Thomas Metzinger’s magisterial Being No One.

The bulk of the article is devoted to defending Metzinger’s neurobiological theory of selfhood as a kind of subreptive representational device (the Phenomenal Self Model, or PSM) from the critiques of Jurgen Habermas and Dan Zahavi, both of whom are intent on arguing the priority of the transcendental over the merely empirical–asserting, in other words, that playing normative (Habermas) or phenomenological (Zahavi) bridge is the condition of playing neuroscientific poker. But what Brassier is actually intent on showing is how the Sellarsian account of rationality is thoroughly consistent with ‘being no one.’

As he writes:

Does the institution of rationality necessitate the canonization of selfhood? Not if we learn to distinguish the normative realm of subjective rationality from the phenomenological domain of conscious experience. To acknowledge a constitutive link between subjectivity and rationality is not to preclude the possibility of rationally investigating the biological roots of subjectivity. Indeed, maintaining the integrity of rationality arguably obliges us to examine its material basis. Philosophers seeking to uphold the privileges of rationality cannot but acknowledge the cognitive authority of the empirical science that is perhaps its most impressive offspring. Among its most promising manifestations is cognitive neurobiology, which, as its name implies, investigates the neurobiological mechanisms responsible for generating subjective experience. Does this threaten the integrity of conceptual rationality? It does not, so long as we distinguish the phenomenon of selfhood from the function of the subject. We must learn to dissociate subjectivity from selfhood and realize that if, as Sellars put it, inferring is an act – the distillation of the subjectivity of reason – then reason itself enjoins the destitution of selfhood. (“The View From Nowhere,” 6)

The neuroscientific ‘destitution of selfhood’ is only a problem for rationality, in other words, if we make the mistake of putting consciousness before content. The way to rescue normative rationality, in other words, is to find some way to render it compatible with the subpersonal–the mechanistic. This is essentially Daniel Dennett’s perennial argument, dating all the way back to Content and Consciousness. And this, as followers of TPB know, is precisely what I’ve been arguing against for the past several months, not out of any animus to the general view–I literally have no idea how one might go about securing the epistemic necessity of the intentional otherwise–but because I cannot see how this attempt to secure meaning against neuroscientific discovery amounts to anything more than an ingenious form of wishful thinking, one that has the happy coincidence of sparing the discipline that devised it. If neuroscience has imperilled the ‘person,’ and the person is plainly required to make sense of normative rationality, then an obvious strategy is to divide the person: into an empirical self we can toss to the wolves of cognitive science and into a performative subject that can nevertheless guarantee the intentional.

Let’s call this the ‘Soul-Soul strategy’ in contradistinction to the Soul-First strategies of Habermas and Zahavi (or the Separate-but-Equal strategy suggested by Pinker above). What makes this option so attractive, I think, anyway, is the problem that so cripples the Soul-First and the Separate-but-Equal options: the empirical fact that the brain comes first. Gunshots to the head put you to sleep. If you’ve ever wondered why ‘emergence’ is so often referenced in philosophy of mind debates, you have your answer here. If Zahavi’s ‘transcendental subject,’ for instance, is a mere product of brain function, then the Soul-First strategy becomes little more than a version of Creationism and the phenomenologist a kind of Young-Earther. But if it’s emergent, which is to say, a special product of brain function, then he can claim to occupy an entirely natural, but thoroughly irreducible ‘level of explanation’–the level of us.

This is far and away the majority position in philosophy, I think. But for the life of me, I can’t see how to make it work. Cognitive science has illuminated numerous ways in which our metacognitive intuitions are deceptive, effectively relieving deliberative metacognition of any credibility, let alone its traditional, apodictic pretensions. The problem, in other words, is that even if we are somehow a special product of brain function, we have no reason to suppose that emergence will confirm our traditional, metacognitive sense of ‘how it’s gotta be.’ ‘Happy emergence’ is a possibility, sure, but one that simply serves to underscore the improbability of the Soul-First view. There’s far, far more ways for our conceits to be contradicted than confirmed, which is likely why science has proven to be such a party crasher over the centuries.

Splitting the soul, however, allows us to acknowledge the empirically obvious, that brain function comes first, without having to relinquish the practical necessity of the normative. Therein lies its chief theoretical attraction. For his part, Brassier relies on Sellars’ characterization of the relation between the manifest and the scientific images of man: how the two images possess conceptual parity despite the explanatory priority of the scientific image. Brain function comes first, but:

The manifest image remains indispensable because it provides us with the necessary conceptual resources we require in order to make sense of ourselves as persons, that is to say, concept-governed creatures continually engaged in giving and asking for reasons. It is not privileged because of what it describes and explains, but because it renders us susceptible to the force of reasons. It is the medium for the normative commitments that underwrite our ability to change our minds about things, to revise our beliefs in the face of new evidence and correct our understanding when confronted with a superior argument. In this regard, science itself grows out of the manifest image precisely insofar as it constitutes a self-correcting enterprise. (4)

Now this is all well and fine, but the obvious question from a relentlessly naturalistic perspective is simply, ‘What is this ’force’ that ‘reasons’ possess?’ And here it is that we see the genius of the Soul Soul strategy, because the answer is, in a strange sense, nothing:

Sellars is a resolutely modern philosopher in his insistence that normativity is not found but made. The rational compunction enshrined in the manifest image is the source of our ability to continually revise our beliefs, and this revisability has proven crucial in facilitating the ongoing expansion of the scientific image. Once this is acknowledged, it seems we are bound to conclude that science cannot lead us to abandon our manifest self-conception as rationally responsible agents, since to do so would be to abandon the source of the imperative to revise. It is our manifest self-understanding as persons that furnishes us, qua community of rational agents, with the ultimate horizon of rational purposiveness with regard to which we are motivated to try to understand the world. Shorn of this horizon, all cognitive activity, and with it science’s investigation of reality, would become pointless. (5)

Being a ‘subject’ simply means being something that can act in a certain way, namely, take other things as intentional. Now I know first hand how convincing and obvious this all sounds from the inside: it was once my own view. When the traditional intentional realist accuses you of reducing meaning to a game of make-believe, you can cheerfully agree, and then point out the way it nevertheless allows you to predict, explain, and manipulate your environment. It gives everyone what the they want: You can yield explanatory priority to the sciences and yet still insist that philosophy has a turf. Wither science takes us, we need not move, at least when it comes to those ‘indispensable, ultimate horizons’ that allow us to make sense of what we do. It allows the philosopher to continue speaking in transcendental terms without making transcendental commitments, rendering it (I think anyway) into a kind of ‘performative first philosophy,’ theoretically innoculating the philosopher against traditional forms of philosophical critique (which require ontological commitment to do any real damage).

The Soul-Soul strategy seems to promise a kind of materialism without intentional tears. The problem, however, is that cognitive science is every bit as invested in understanding what we do as in describing what we are. Consider Brassier’s comment from above: “It is our manifest self-understanding as persons that furnishes us, qua community of rational agents, with the ultimate horizon of rational purposiveness with regard to which we are motivated to try to understand the world.” From a cognitive science perspective one can easily ask: Is it? Is it our ‘manifest understanding of ourselves’ that ‘motivates us,’ and so makes the scientific enterprise possible?

Well, there’s a growing body of research that suggests we (whatever we may be) have no direct access to our motives, but rather guess with reference to ourselves using the same cognitive tools we use to guess at the motives of others. Now, the Soul-Soul theorist might reply, ‘Exactly! We only make sense to ourselves against a communal background of rational expectations…’ but they have actually missed the point. The point is, our motivations are occluded, which raises the possibility that our explanatory guesswork has more to do with social signalling than with ‘getting motivations right.’ This effectively blocks ‘motivational necessity’ as an argument securing the ineliminability of the intentional. It also raises the question of what kind of game are we actually playing when we play the so-called ‘game of giving and asking for reasons.’ All you need consider is the ‘spectre’ neuromarketing in the commercial or political arena, where one interlocutor secures the assent of the other by treating that other subpersonally (explicitly, as opposed to implicitly, which is arguably the way we treat one another all the time).

Any number of counterarguments can be adduced against these problems, but the crucial thing to appreciate is that these concerns need only be raised to expose the Soul-Soul strategy as mere make-believe. Sure, our brains are able to predict, explain, and manipulate certain systems, but the anthropological question requiring scientific resolution is one of where ‘we’ fit in this empirical picture, not just in the sense of ‘destitute selves,’ but in every sense. Nothing guarantees an autonomous ‘level of persons,’ not incompatibility with mechanistic explanation, and least of all speculative appraisals (of the kind, say, Dennett is so prone to make) of its ‘performative utility.’

To sharpen the point: If we can’t even say for sure that we exist the way we think, how can we say that our brains nevertheless do the things we think they do, things like ‘inferring’ or ‘taking-as intentional.’

Brassier writes:

The concept of the subject, understood as a rational agent responsible for its utterances and actions, is a constraint acquired via enculturation. The moral to be drawn here is that subjectivity is not a natural phenomenon in the way in which selfhood is. (32)

But as a doing it remains a ‘natural phenomenon’ nonetheless (what else would it be?). As such, the question arises, Why should we expect that ‘concepts’ will suffer a more metacognitive-intuition friendly fate than ‘selves’? Why should we think the sciences of the brain will fail to revolutionize our traditional normative understanding of concepts, perhaps relegate it to a parochial, but ineliminable shorthand forced upon us by any number of constraints or confounds, or so contradict our presumed role in conceptual thinking as to make ‘rationality’ as experienced a kind of in inter fiction. What we cognize as the ‘game of giving and asking for reasons,’ for all we know, could be little more than the skin of plotting beasts, an illusion foisted on metacognition for the mere want of information.

Brassier writes:

It forces us to revise our concept of what a self is. But this does not warrant the elimination of the category of agent, since an agent is not a self. An agent is a physical entity gripped by concepts: a bridge between two reasons, a function implemented by causal processes but distinct from them. (32)

Is it? How do we know? What ‘grips’ what how? Is the function we attribute to this ‘gripping’ a cognitive mirage? As we saw in the case of homicidal somnambulism above, it’s entirely unclear how subpersonal considerations bear on agency, whether understood legally or normatively more generally. But if agency is something we attribute, doesn’t this mean the sleepwalker is a murderer merely if we take him to be? Could we condemn personal Scott to death by lethal injection in good conscience knowing we need only think him guilty for him to be so? Or are our takings-as constrained by the actual function of his brain? But then how can we scientifically establish ‘degrees of agency’ when the subpersonal, the mechanistic, has the effect of chasing out agency altogether?

These are living issues. If it weren’t for the continual accumulation of subpersonal knowledge, I would say we could rely on collective exhaustion to eventually settle the issue for us. Certainly philosophical fiat will never suffice to resolve the matter. Science has raised two spectres that only it can possibly exorcise (while philosophy remains shackled on the sidelines). The first is the spectre of Theoretical Incompetence, the growing catalogue of cognitive shortcomings that probably explain why it is only science can reliably resolve theoretical disputes. The second is Metacognitive Incompetence, the growing body of evidence that overthrows our traditional and intuitive assumptions of self-transparency. Before the rise of cognitive science, philosophy could continue more or less numb to the pinch of the first and all but blind to the throttling possibility of the latter. Now however, we live in an age where massive, wholesale self-deception, no matter what logical absurdities it seems to generate, is a very real empirical possibility.

What we intuit regarding reason and agency is almost certainly the product of compound neglect and cognitive illusion to some degree. It could be the case that we are not intentional in such a way that we must (short of the posthuman, anyway) see ourselves and others as intentional. Or even worse, it could be the case that we are not intentional in such a way that we can only see ourselves and others as intentional whenever we deliberate on the scant information provided by metacognition–whenever we ‘make ourselves explicit.’ Whatever the case, whether intentionality is a first or second-order confound (or both), this means that pursuing reason no matter where it leads could amount to pursuing reason to the point where reason becomes unrecognizable to us, to the point where everything we have assumed will have to be revised–corrected. And in a sense, this is the argument that does the most damage to Sellar’s particular variant of the Soul-Soul strategy: the fact that science, having obviously run to the limits of the manifest image’s intelligibility, nevertheless continues to run, continues to ‘self-correct’ (albeit only in a way that we can understand ‘under erasure’), perhaps consigning its wannabe guarantor and faux-motivator to the very dust-bin of error it once presumed to make possible.

In his recent After Nature interview, Brassier writes:

[Nihil Unbound] contends that nature is not the repository of purpose and that consciousness is not the fulcrum of thought. The cogency of these claims presupposes an account of thought and meaning that is neither Aristotelian—everything has meaning because everything exists for a reason—nor phenomenological—consciousness is the basis of thought and the ultimate source of meaning. The absence of any such account is the book’s principal weakness (it has many others, but this is perhaps the most serious). It wasn’t until after its completion that I realized Sellars’ account of thought and meaning offered precisely what I needed. To think is to connect and disconnect concepts according to proprieties of inference. Meanings are rule-governed functions supervening on the pattern-conforming behaviour of language-using animals. This distinction between semantic rules and physical regularities is dialectical, not metaphysical.

Having recently completed Rosenberg’s The Atheist’s Guide to Reality, I entirely concur with Brassier’s diagnosis of Nihil Unbound’s problem: any attempt to lay out a nihilistic alternative to the innumerable ‘philosophies of meaning’ that crowd every corner of intellectual life without providing a viable account of meaning is doomed to the fringes of humanistic discourse. Rosenberg, for his part, simply bites the bullet, relying on the explanatory marvels of science and its obvious incompatibilities with meaning to warrant dispensing with the latter. The problem, however, is that his readers can only encounter his case through the lense of meaning, placing Rosenberg in the absurd position of using argumentation to dispel what, for his interlocutors, lies in plain sight.

Brassier, to his credit, realizes that something must be said about meaning, that some kind of positive account must be given. But in the absence of any positive, nihilistic alternative–any means of explaining meaning away–he opts for something deflationary, he turns to Sellars (as did Dennett), and the presumption that meaning pertains to a different, dialectical order of human community and interaction. This affords him the appearance of having it both ways (like Dennett): deference to the priority of mechanism, while insisting on the parity of meaning and reason, arguing, in effect, that we have two souls, one a neurobiological illusion, the other a ‘merely functional’ instrument of enormous purport and power…

Or so it seems.

What I’ve tried to show is that cognitive science cares not a whit whether we characterize our commitments as metaphysical or dialectical, that it is just as apt to give lie to metacognitively informed accounts of what we do as to metacognitively informed accounts of what we are. ‘Inferring’ is no more immune to radical scientific revision than is ‘willing’ or ‘believing’ or ‘taking as’ or what have you. So for example, if the structures underwriting consciousness in the brain were definitively identified, and the information isolated as ‘inferring’ could be shown to be, say, distorted low-dimensional projections, jury-rigged ‘fixes’ to far different evolutionary pressures, would we not begin, in serious discussions of cognition or what have you, to continually reference these limitations to the degree they distort our understanding of the actual activity involved? If it becomes a scientific fact that we are a far different creature in a far different environment than what we take ourselves to be, will that not radically transform any discourse that aspires to be cognitive?

Of course it will.

Perhaps the post-intentional philosophy of the future will see the ‘game of giving and asking for reasons’ as a fragmentary shadow, a comic strip version of our actual activity, more distortion than distillation because neither the information nor the heuristics available for deliberative metacognition are adapted to the needs of deliberative metacognition.

This is one reason why I think ‘natural anosognosia’ is such an apt way to describe our straits. We cannot get past the ‘only game in town sense’, or agency, primarily because there’s nothing else to be got. This is the thing about positing ‘functions’: the assumption is that what we experience does what we think it does the way we think it should. There is no reason to assume this must be the case once we appreciate the ubiquity and the consequences of informatic neglect (and our resulting metacognitive incompetence). We have more than enough in the way of counterintuitive findings to worry that we are about to plunge over a cliff–that the soul, like the sky, might simply continue dropping into an ever deeper abyss. The more we learn about ourselves, the more post hoc and counterintuitive we become. Perhaps this is astronomically the case.

Here’s the funny thing: the naturalistic fundamentals are exceedingly clear. Humans are information systems that coordinate via communicated information. The engineering (reverse or forward) challenges posed by this basic picture are enormous, but conceptually, things are pretty clear–so long as you keep yourself off-screen.

We are the only ‘fundamental mystery’ in the room. The problem of meaning is the problem of us.

In addition to Rosenberg’s Atheist’s Guide to Reality I also recently completed reading Plato’s Camera by Churchland and The Cognitive Science of Science by Thagard and I found the contrast… bracing, I guess. Rosenberg made stark the pretence (or more charitably, promise) marbled throughout Churchland and Thagard, the way they ceaselessly swap between the mechanistic and the intentional as if their descriptions of the first, by the mere fact of loosely correlating to our assumptions regarding the latter, somehow explained the latter. Thagard, for instance, goes so far as to claim that the ‘semantic pointer’ model of concepts that he adapts from Eliasmith (of recent SPAUN fame) solves the symbol grounding problem without so much as mentioning how, when, or where semantic pointers (which are eminently amenable to BBT) gain their hitherto inexplicable normative/intentional properties. In other words, they simply pretend there’s no real problem of meaning–even Churchland! “Ach!” they seem to imply, “Details! Details!”

Rosenberg will have none of it. But since he has no way of explaining ‘us,’ he attempts the impossible: he tries to explain us away without explaining us at all, arguing that we are a problem for neuroscience, not for scientism (the philosophical hyper-naturalism that he sees following from the sciences). He claims ‘we’ are philosophically irrelevant because ‘we’ are inconsistent with the world as described by science, not realizing the ease with which this contention can be flipped into the claim that the sciences are philosophically irrelevant so long as they remain inconsistent with us…

Theoretical dodge-ball will not do. Brassier understands this more clearly than any other thinker I know. The problem of meaning has to be tackled. But unlike Jesus, we have cannot cast the subpersonal out into two thousand suicidal swine. ‘Going dialectical,’ abandoning ‘selves’ for the perceived security of ‘rational agency’ ultimately underestimates the wholesale nature of the revisionary/eliminative threat posed by the cognitive sciences, and the degree to which our intentional self-understanding relies on ignorance of our mechanistic nature. Any scientific account of physical regularities that explains semantic rules in terms that contradict our metacognitive assumptions will revolutionize our understanding of ‘rational agency,’ no matter what definitional/theoretical prophylactics we have in place.

Habermas’ analogy of “a consciousness that hangs like a marionette from an inscrutable criss-cross of strings” (“The Language Game or Responsible Agency and the Problem of Free Will,” 24) seems more and more likely to be the case, even at the cost of our ability to make metacognitive sense of our ‘selves’ or our ‘projects.’ (Evolution, to put the point delicately, doesn’t give a flying fuck about our ability to ‘accurately theorize’). This is the point I keep hammering via BBT. Once deliberative theoretical metacognition has been overthrown, it’s anybody’s guess how the functions we attribute to ourselves and others will map across the occluded, orthogonal functions of our brain. And this simply means that the human in its totality stands exposed to the implacable indifference of science…

I think we should be frightened–and exhilarated.

Our capacity to cognize ourselves is an evolutionary shot in the neural dark. Could anyone have predicted that ‘we’ have no direct access to our beliefs and motives, that ‘we’ have to interpret ourselves the way we interpret others? Could anyone have predicted the seemingly endless list of biases discovered by cognitive psychology? Or that the ‘feeling of willing’ might simply be the way ‘we’ take ownership of our behaviour post hoc? Or that ‘moral reasoning’ is primarily a PR device? Or that our brains regularly rewrite our memories? Think, Hume, the philosopher-prophet, and his observation that Adam could never deduce that water drowns or fire burns short of worldly experience. What we do, like what we are, is a genuine empirical mystery simply because our experience of ourselves, like our experience of earth’s motionless centrality, is the product of scant and misleading information.

The human in its totality stands exposed to the implacable indifference of science, and there’s far, far more ways for our intuitive assumptions to be wrong as opposed to right. I sometimes imagine I’m sitting around this roulette wheel, with fairly everyone in the world ‘going with their gut’ and stacking all their chips on the zeros, so there’s this great teetering tower swaying on intentional green, leaving the rest of the layout empty… save for solitary corner-betting contrarians like me and, I hope, Brassier.

January 2, 2013

The ‘Human’: Discovery or Invention?

Aphorism of the Day:

;

“A lack of historical sense is the congenital defect of all philosophers. Some unwittingly even take the most recent form of man, as it developed under the imprint of certain religions or even certain political events, as the fixed form from which one must proceed.”

– Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human

;