R. Scott Bakker's Blog, page 24

March 26, 2013

Three Roses: The Port of Syrilla

Hey all. Roger Eichorn here yet again.

I’ve uploaded the second of two Bonus Scenes from my fantasy novel-in-progress, The House of Yesteryear (the first book in a trilogy called Three Roses). It follows the events of the first Bonus Scene.

As before, I’m including the first few paragraphs of the Bonus Scene here.

———————————————

1546, Moon of Octumnel (Early Autumn), The Hataengale Sea

The sea was in Davyd Carverus’s blood.

His family hailed from a salt-swept village outside Moraelport, on the Isle of Stars. Their father had sweated and cursed upon the decks of fishing yawls all his life, as his own father and grandfather—and likely his great-grandfather and great-great-grandfather—had done before him. Upon their twelfth birthdays, each of Carverus’s three older brothers had left the Macarieli schoolhouse to join Father in hauling the nets. Such was the life that fate and the world had prepared for Davyd Carverus—or so, with mounting anger and dread, he had believed.

He may have the sea in his blood, but not a trace of it was to be found in his soul—nor in his stomach, which rebelled against every evil undulation of the wicked waters…

March 23, 2013

Metaphilosophical Reflections III: The Skeptical Dialectic

“Human reason is a two-edged and dangerous sword.”

– Montaigne, “Of Presumption”

—————————————————–

This is the third in a series of guest-blogger posts by me, Roger Eichorn. The first two posts can be found here and here.

I’m also a would-be fantasy author. The first three chapters of my novel, The House of Yesteryear, can be found here. I’ve also recently uploaded the first of what will be two ‘Bonus Scenes’ from later in the book. You can find it here, if you’re into that sort of thing.

—————————————————–

In my previous post, I argued that skepticism and philosophy are inextricably entwined. Following Hegel, Michael Forster has made a similar argument, and I’ve benefited a great deal (and cribbed) from his discussion. But whereas Forster stops with the claim that an engagement (direct or indirect) with skepticism is a defining feature of philosophy, I’ve gone farther and tried to develop a conceptual framework for understanding why this is the case. My explanation turns on the notion of presuppositions. The view, in short, is this:

Intellectual inquiry can make determinate progress only against a background of unquestioned fundamental premises, propositions, or assumptions (what I call ‘presuppositions’).

These fundamental presuppositions provide contexts for inquiry; they are like boundary-markers or the rules of a game, in that overstepping or questioning them entails ceasing to play the ‘discursive game’ they enclose or constitute.

Calling into question context-constitutive presuppositions involves a kind of skepticism.

Stepping outside of a presupposition context entails ‘going meta,’ i.e., it entails transitioning into a more abstract domain of inquiry.

Given (3) and (4), it is skepticism that pushes us to ever-greater levels of discursive–epistemological abstraction.

In ‘going meta,’ we end up—either immediately or after some intermediary steps—within the domain of philosophy.

Given (5) and (6), it is skepticism that leads us to philosophy, i.e., philosophy begins in skepticism.

There is no uncontroversial rationale that is both global and principled for forestalling the possibility of ‘going meta,’ i.e., of calling into question any presupposition. (Principled rationales are always context-specific or ‘local.’ The claim I’m making here, then, is that there are no principled meta-contextual, i.e., global, rationales for forestalling the questioning of a presupposition or set of presuppositions.)

Given (8), according to which any presupposition can be called into question, and (6), according to which philosophy is the domain of inquiry one occupies (sooner or later) in calling presuppositions into question, it follows that philosophy as such possesses no definitive presupposition-set of its own.

Given (1) and (9), philosophy can make no determinate progress.

Given (10), philosophy ends in skepticism.

This argument can, of course, be challenged on any number of fronts. I have not, for instance, made a sufficient case for (1). I touched on it in my previous post (where I mentioned Stalnaker and Wittgenstein), but I did not attempt to defend the view in any detail. Nor, in the interests of space, am I going to do so here. It should be enough for now to note (1)’s extreme plausibility. If we visualize intellectual progress as involving forward movement, and the act of questioning presuppositions as involving backward movement, then it’s easy to see that we can make progress only if we’re not calling presuppositions into question: we have to stop moving backward before we can move forward. Given (8)—which is itself a plausible view, though with its own complications—these presuppositions-of-inquiry must remain unquestioned, either in the sense of (a) never having been thematized or (b) being set aside, “apart from the route travelled by enquiry” (Wittgenstein, On Certainty, §88), whether (i) they are recognized as questionable though necessarily unquestioned (just as the rules of a game are questionable, but cannot be questioned from within the game itself) or (ii) they are (mis)taken as lying beyond all question (as in the form of indubitable first principles, the supposedly self-evident, etc.).

In this post, I want to elaborate—and with any luck buttress—my case for (3), (4), and (6). I want, in other words, to get clearer on the dialectical relations among presuppositions, skepticism, and philosophy.

—————————————————–

In earlier posts, I introduced the idea of ‘common life,’ which I’m conceptualizing here as the general, usually invisible presupposition context that frames our everyday sayings and doings. Common life is our twofold inheritance as beings who are both embodied in nature and embedded in a society; it is our natural medium, the subcognitive water for us cognitive fishes. When we are, as Hubert Dreyfus or Richard Rorty (influenced by Heidegger and pragmatism) would put it, smoothly and effortlessly ‘coping with the world,’ the fact of common life’s inherent questionability—its possible contingency—never presents itself. At such times, common life is (to borrow some Heideggerian terminology) ‘inconspicuous’ (see: Being and Time, §§15–6). Common life becomes ‘conspicuous’ only as a result of disruptions in the orderly flow of our everyday lives. Such disruptions can be relatively minor (what Heidegger called the mode of ‘obtrusiveness’). But they can also be more significant (what Heidegger called the mode of ‘obstinacy’). The deeper the disruption, the more the presuppositional structure of common life comes into view. The more the presuppositional structure of common life comes into view, the higher its ‘index of questionability’ climbs (cf., Luciano Floridi, Scepticism and the Foundation of Epistemology, Ch. 4).

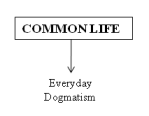

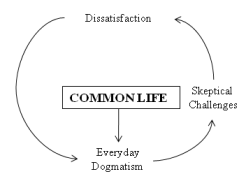

Initially, then, we occupy the standpoint of common life as what I call ‘everyday dogmatists.’ This means that we acquiesce, usually unconsciously, in everyday dogmatisms: we (mis)take (again, usually only implicitly) the presuppositions of common life for known truths.

Michel de Montaigne wrote that “[p]resumption is our natural and original malady” (Apology for Raymond Sebond). Everyday dogmatism is, in his terms, ‘everyday presumption.’ In her book on Montaigne, Ann Hartle characterizes everyday presumption as “the unreflective milieu of prephilosophical certitude, the sea of opinion in which we are immersed” (Montaigne: Accidental Philosopher, p. 106). Human beings are, as I like to put it, natural-born dogmatists.

Common life provides us not only with first-order beliefs, but also with more or less established means of adjudicating many, even most, sorts of dispute. For instance, authoritative scriptures belong to the presupposition-framework of the common life into which many people are born. For such people, appeal to scripture is capable of settling certain kinds of dispute: in these cases, common life itself provides the resources that allow for the resolution of conflicts that arise within common life.

An initial challenge to an everyday dogmatism is issued. Here we encounter the most rudimentary form of skepticism. The skeptical challenge gives rise to a state of dissatisfaction: there is a felt need to resolve the conflict, to ‘refute’ the skeptic and restore our earlier confidence in the dogmatisms of common life. In many cases of such skeptical challenges, the dissatisfaction in question can be resolved simply by drawing more water from the well of everyday dogmatisms. In more extreme cases, the skeptical challenges can be resolved only by appealing to the context-constitutive presuppositions of common life. Either way, what we have is a kind of circular dialectic of skepticism and dogmatism.

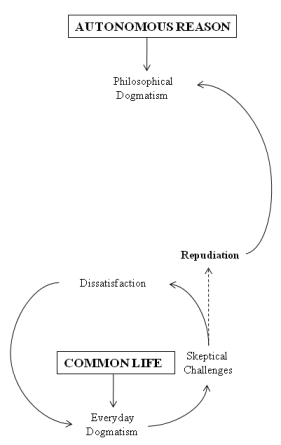

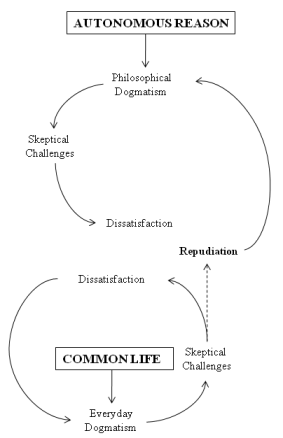

In time, though, the skeptical challenges grow more sophisticated. They reach their apogee when they call into question not just intracontextual everyday dogmatisms, nor just one or another context-constitutive presupposition of common life, but rather common life as a whole. When that happens, it becomes clear that no appeal to everyday dogmatisms can satisfactorily answer the skeptical challenge, for the skeptical challenge now calls into question the entire domain of everyday dogmatisms.

Consider a simple case of perceptual skepticism. You see a tree. You think you know it’s a tree, precisely because you can see it (and you know what trees are, what they look like, etc.). This is an entirely acceptable everyday judgment, accompanied by an entirely acceptable everyday justification. Then a skeptic comes along and asks you how you know that what you think you see is actually a tree. At this point, no dissatisfaction arises, since you have to hand your everyday justification. But the skeptic presses the point: “How do you know it’s not an extraordinarily lifelike papier-mâché tree?” This might be enough to give rise to dissatisfaction; if not, then imagine that the skeptic has some further story to tell about how the city in which you both live has funded an art project that involves the creation of amazingly lifelike papier-mâché trees. Now you’re prepared to call into question your belief that it’s a tree (along with the sufficiency of your everyday justification). What do you do now? Obviously, you walk up to the tree and inspect it. The skeptic has hardly deprived you of all your everyday means of settling disputes. You poke the tree, peel back its bark, pluck off a leaf, and conclude that, clearly, this is not a papier-mâché tree. But what do you do when the skeptic smiles and asks, “Fair enough. But how do you know you’re not dreaming?”

Now, most of us would, most of the time, simply dismiss this question as nonsense. We’d say, “‘O, rubbish!’ to someone who wanted to make objections to the propositions that are beyond doubt. That is, not reply to him but admonish him” (Wittgenstein, On Certainty, §495). But the problem of justification remains. Most of us are going to believe that we’re justified in claiming to know that we’re not dreaming (even more so that we’re not dreaming all the time) and that we therefore know all sorts of things about the world as a result of our present and past experiences. Nothing is easier, in the course of our everyday lives, than to dismiss this sort of worry. But if it nags at us—if it persists as a source of dissatisfaction—then we’re going to want to find an answer to the skeptic. But, ex hypothesi, we’ve accepted the fact that we cannot answer the skeptical challenge by appealing to our experience (in the broader case: to common life or its presuppositions), since the skeptical challenge has called into question the veridicality of our experience in toto (in the broader case: the veridicality of common life and its presuppositions in toto). What do we do?

Bearing in mind that this whole process is animated by a commitment to truth and rationality (by what Nietzsche called our ‘intellectual conscience’), without which our capacity for epistemico-existential crises would be severely limited, there seems only one path open to us: that is, to repudiate the inherent authority of common life in favor of what I call autonomous reason.

I borrow the phrase ‘autonomous reason’ from Donald Livingston’s book on Hume (Hume’s Philosophy of Common Life). Livingston claims that, for Hume, philosophy is committed to autonomous reason, according to which “it is philosophically irrational to accept any standard, principle, custom, or tradition of common life unless it has withstood the fires of critical philosophical reflection” (23). We can quibble about whether or not this applies to every philosopher or even every philosophical tradition; but that’s beside the point if the claim is correct in the main—and I think it is. Moreover, I think it’s not just superficially correct (‘in the main’), but that it illuminates a deep and important feature of philosophy that goes back to its very earliest manifestations.

Philosophy is, at least initially, predicated on skepticism regarding common life. Thus, it seeks autonomy. The philosophy–common life distinction can be understood in terms of the familiar dichotomy between reason and tradition. Reason’s autonomy from tradition is often taken to be a necessary feature of any properly critical enterprise. As Kenneth Westphal has noted in referring to a “dichotomy, pervasive since the Enlightenment, that reason and tradition are distinct and independent resources”: “because tradition is a social phenomenon, reason must be an independent, individualistic phenomenon. Otherwise it could not assess or critique tradition, because criticizing tradition requires an independent, ‘external’ standpoint and standards” (Hegel’s Epistemology, p. 77). Westphal rejects this view, but it is common enough. Nicholas Wolterstorff, for example, gives voice to it when he writes, “Traditions are still a source of benightedness, chicanery, hostility, and oppression… In this situation, examining our traditions remains for many of us a deep obligation, and for all of us together, a desperate need” (John Locke and the Ethics of Belief, p. 246). Enlightened reason, in other words, must be able to rise above the soup of prejudices that is common life; otherwise, it will be unable to establish the distance needed to criticize those traditions.

These metatheoretical concerns are usually articulated without any reference to skepticism. Even when it is separated from the Kantian project, however, critique is best understood as a response to skepticism, an attempt to forge a middle way between skepticism and dogmatism. The repudiation of the inherent authority of common life and the subsequent commitment to autonomous reason is predicated on a kind of skepticism. And this is not, as is commonly claimed or implied, unique (whether as a whole or just in character) to the modern period. Rather, this kind of skepticism was a precondition of the emergence of philosophical thought itself, 2,500 years ago. The motto for this transition is von Mythos zum Logos—from myth to reason.

—————————————————–

In his fascinating book The Discovery of the Mind—a study of conceptions of the self in archaic and ancient Greece—Bruno Snell refers to the emergence of a “social scepticism” that opened up a space within which individuals could call into question the epistemic and practical authority of the traditions into which they’d been born. Given this sort of social skepticism, according to Snell, “[r]eality is no longer something that is simply given. The meaningful no longer impresses itself as an incontrovertible fact, and appearances have ceased to reveal their significance directly to man. All this really means that myth has come to an end” (p. 24). The repudiation of myth was, on my picture, a repudiation by philosophers of common life, of the world of their fathers. Malcolm Schofield has written that “[t]he transition from myths to philosophy… entails, and is the product of, a change that is political, social and religious rather than sheerly intellectual, away from the closed traditional society… and toward an open society in which the values of the past become relatively unimportant and radically fresh opinions can be formed both of the community itself and of its expanding environment… It is this kind of change that took place in Greece between the ninth and sixth centuries B.C.” (The Presocratic Philosophers, pp. 73–4).

Going beyond the Eurocentrism of Snell and Schofield, Karl Jaspers developed the idea of what he calls ‘the Axial Age,’ a period of sudden social, political, and philosophical enlightenment that, he claimed, occurred nearly simultaneously and yet independently in Greece (with the Presocratics), India (with the Buddha), and China (with Confucianism and Daoism). In this period, Jaspers writes, “hitherto unconsciously accepted ideas, customs and conditions were subjected to examination, questioned and liquidated. Everything was swept into the vortex. In so far as the traditional substance still possessed vitality and reality, its manifestations were clarified and thereby transmuted” (The Origin and Goal of History, p. 2). As though to confirm Jaspers’s theory—though he was writing decades earlier—S. Radhakrishnan tells us that

[t]he age of the Buddha represents the great springtide of philosophical spirit in India. The progress of philosophy is generally due to a powerful attack on a historical tradition when men feel themselves compelled to go back on their steps and raise once more the fundamental questions which their fathers had disposed of by the older schemes. The revolt of Buddhism and Jainism… finally exploded the method of dogmatism and helped to bring about a critical point of view… Buddhism served as a cathartic in clearing the mind of the cramping effects of ancient obstructions. Scepticism, when it is honest, helps to reorganise belief. (Indian Philosophy, Vol. 2, p. 18)

The notion of a clear-cut transition ‘from myth to reason’ is deeply entrenched in our cultural narrative, yet it is clearly problematic if understood in an overly simplistic way. Just as Aristotle was not the first person to use logic, so the presocratic philosophers were not the first Greeks to use reason or to think reasonably. Still, I think it is clear that something important occurred during the Axial Age. It may not have been unprecedented, as some commentators want to claim, but its effects were, for (it seems to me) we are still feeling those effects today. The fundamental transition, I want to argue, is best understood not as being from myth to reason, but as being from common life to autonomous reason.

The ability of reasoning to call into question—to radically disrupt—common life was recognized very early. Plato worries about it in the Republic

We all have strongly held beliefs, I take it, going back to our childhood [i.e., our pretheoretical certainties], about things which are just and things which are fine and beautiful… When someone… encounters the question ‘What is the beautiful?’, and gives the answer he used to hear from the lawgiver [i.e., from tradition], and argument shows it to be incorrect, what happens to him? He may have many of his answers refuted, in many different ways, and be reduced to thinking that the beautiful is no more beautiful or fine than it is ugly or shameful. The same with ‘just’, ‘good’, and the things he used to have more respect for. At the end of this, what do you think his attitude to these strongly held beliefs will be, when it comes to respect for them and obedience to their authority?… I imagine he’ll be thought to have changed from a law-abiding citizen into a criminal. (538c–539a)

We find the same recognition of the cultural–existential (as opposed to merely epistemological) threat of skepticism in Hegel.

The need to understand logic in a deeper sense than that of the science of mere formal thinking is prompted by the interest we take in religion, the state, the law and ethical life. In earlier times, people had no misgivings about thought… But while engaging in thinking… it turned out that the highest relationships of life are thereby compromised. Through thinking, the positive state of affairs was deprived of its power… Thus, for example, the Greek philosophers opposed the old religion and destroyed representations of it… In this way, thinking made its mark on actuality and had the most awe-inspiring effect. People thus became aware of the power of thinking and started to examine more closely its pretensions. They professed to finding out that it claimed too much and could not achieve what it undertook. Instead of coming to understand the essence of God, nature and spirit and in general the truth, thinking had overthrown the state and religion. (Encyclopedia Logic, §20)

The transition to autonomous reason, then, is in many respects a desperate gamble, an attempt to salvage by way of reason what reason itself has taken away from us, namely, the certainty and stability of common life.

—————————————————–

Thus, the move to autonomous reason gives rise to a new kind of dogmatism, not the simple, inchoate or prereflective dogmatisms of common life, but sophisticated philosophical dogmatisms. The hope of most developers of philosophical dogmatisms is to refute the skeptical challenges that led to the repudiation of common life, to restore common life on a more solid foundation. Unfortunately for philosophical dogmatists, skepticism does not obediently remain at the level of common life, waiting to be overthrown; rather, it follows them up to the level of autonomous reason, continuing to attack them where they live.

As at the level of common life, the initial response to skeptical challenges to philosophical dogmas will involve a circular return to those same philosophical dogmas, hoping to marshal more resources with which to overthrow the skeptic. But, again as at the level of common life, eventually the skeptical challenges will becomes sophisticated enough to call into question the entire epistemological project. The result is metaepistemological skepticism. Its most conceptually powerful, and historically influential, expression is found in the Agrippan Trilemma, which I briefly discussed in the previous post. The fundamental challenge of the Trilemma at the epistemological level is this: How do you justify that which makes justification possible? Just as the skeptical challenges at the level of common life ended up calling into question the presupposition context of common life as a whole, likewise skeptical challenges at the level of autonomous reason end up calling into question the presupposition context of autonomous reason as a whole. The question, of course, is where this leaves us.

I’ll take up that question, among others, in my next post.

March 20, 2013

Metaphilosophical Reflections II: The Entwinement of Skepticism and Philosophy

“… skepticism itself is in its inmost heart at one with every true philosophy.”

– Hegel, On the Relationship of Skepticism to Philosophy

“Whoever is believed in his presuppositions, he is our master and our God; he will plant his foundations so broad and easy that by them he will be able to raise us, if he wants, up to the clouds.”

– Montaigne, Apology for Raymond Sebond

—————————————————–

This is the second in a series of guest-blogger posts by me, Roger Eichorn. The first post can be found here.

I’m also a would-be fantasy author. The first three chapters of my novel, The House of Yesteryear, can be found here. I’ve also recently uploaded the first of what will be two ‘Bonus Scenes’ from later in the book. You can find that here. Now on to business…

—————————————————–

What is philosophy?

In asking this question, it is misguided—and probably hopeless—to insist upon a strict definition (i.e., a definition that specifies necessary and sufficient conditions for something to qualify as ‘philosophy’). Chances are good that no such definition is possible. Rather, it is likely that philosophy is what Wittgenstein called a ‘family resemblance’ concept, that is, a concept that picks out a number of importantly distinct things that are more or less loosely bound together by a resemblance-relation. Wittgenstein’s most famous example is the concept game: it seems impossible to provide necessary and sufficient conditions for something to qualify as a game, yet it also seems that all the various things we refer to as ‘games’ bear some sort of resemblance to one another.

What I’m after, then, is not a strict definition, but a sort of physiognomy of philosophy. What is/are the most salient or common feature(s) of the family resemblance? The explanatory desideratum is to understand what makes philosophy distinct from other intellectual domains. What distinguishes philosophy from, say, theology or the sciences? In most cases, it does seem that, as with porn, we ‘know it when we see it.’ But I think that, in addressing the question “What is philosophy?”, we can do better than simply pointing to examples. Indeed, I believe that there is a single feature of philosophy that both (a) stands out more prominently than any other and (b) provides the groundwork for a systematic explanation both of philosophy’s relation to other intellectual domains and of the apparent interminability of philosophical inquiries. That feature is skepticism.

Philosophy and skepticism are, I want to argue, inextricably entwined.

—————————————————–

Now, what exactly I mean by ‘the entwinement of skepticism and philosophy’ will be the topic of this and the two posts that will follow. Thus, my claim should not be prejudged. In particular, it should not be dismissed out of hand. Given what I’ve said so far, there are numerous ways of understanding the claim as meaning things I do not intend.

I began by asking “What is philosophy?” Now, it seems, I’m forced to address first another nebulous question, namely, “What is skepticism?” In fact, my answers to both questions will unfold together, over the course of this and subsequent posts. The questions will be approached by way of a discussion of presuppositions, specifically the idea of freedom from presuppositions, or ‘presuppositionlessness.’

What do I mean by ‘presuppositions’? It is important that we not over-intellectualize the concept, for doing so would obscure the sort of presupposition I’m most interested in. I imagine that when many people think of presuppositions, they think first of something like (i) consciously developed and articulated hypotheses, such as those posited by scientists. But there is also a deeper sense of presupposition, according to which presuppositions are (ii) the unreflective (or prereflective) commitments that frame or underlay our sayings and doings, our ‘situation’ as human-beings-in-the-world. Presuppositions of this sort lie so far in the background—or, alternatively, saturate so completely—our cognitive lives as to be effectively invisible. Such presuppositions can, at least in principle, be made visible; but such a process of explication involves thematizing commitments that were already there, rather than (as in the case of scientific hypotheses) developing new commitments. A third sort of presupposition lies somewhere between the two: (iii) they are not hypotheses, but neither are they entirely unreflective. In most cases, this third kind of presupposition will be taken, by those who hold them, as obviously true, perhaps as ‘self-evident.’ Thus, they will not be seen as presuppositions by those who hold them, but as something like fundamental, immovable, or indubitable beliefs/truths.

I shall refer in what follows to presupposition contexts. A presupposition context is a ‘situation,’ with regard to our sayings and doings, that is framed and defined by either the second or the third sort of presupposition introduced in the previous paragraph. Presupposition(ii) contexts define what I call ‘common life,’ i.e., the context into which we’re ‘thrown’ (as Heidegger would say), both as natural beings and as products of a particular culture. Such contexts are the ‘background’ of our ‘everydayness’; their constitutive presuppositions determine to a large extent how the world shows up for us, in the sense of how things strike us, how they appear to us to be. These presuppositions are expressed affectively as well as—indeed, perhaps more fundamentally than they are expressed—cognitively.

For instance, I happen to think that incest is wrong. The proposition is one I find that I cannot fail to assent to. Why do I believe that incest is wrong? I could, of course, marshal any number of reasons to support the belief, but (a) the belief, in its cognitive guise, is capable of withstanding devastating counterarguments, and (b) even if I were brought around, intellectually, to rejecting the belief (which happens when I stop and really think about it), the belief qua affective-disposition remains. In other words, even if I ‘officially’ reject the proposition that incest is wrong, I continue to find incest repulsive. (Regarding this example: see the study referenced and discussed by Jesse Prinz in The Emotional Construction of Morals, p. 30.) This repulsion is, on my view, an expression of the sort of deep underlying commitment that constitutes the context of common life. Common life is, as Wittgenstein put it, an inherited background: “I did not get my picture of the world by satisfying myself of its correctness; nor do I have it because I am satisfied of its correctness. No: it is the inherited background against which I distinguish between true and false” (On Certainty, §94). Presupposition(ii) contexts, then, are similar to what Wittgenstein refers to as ‘world-pictures’: “The propositions describing this world-picture [= in my terms, context-constitutive presuppositions] might be part of a kind of mythology. And their role is like that of rules of a game; and the game can be learned purely practically, without learning any explicit rules” (On Certainty, §95).

Presupposition(iii) contexts are specialized domains of inquiry. Their constitutive presuppositions are more or less reflective on a case-by-case basis. Often, their constitutive presuppositions are going to match, and arise from, presuppositions framing the more general context of common life, with which specialized domains of inquiry are (at least) going to overlap. So, for instance, historians presuppose that the past existed (i.e., that the world didn’t pop into existence five minutes ago), that the past is unchanging, that certain kinds of presently existing artifacts are capable of informing us about what happened in the past, etc. It may be that a given historian has never actually formulated the belief that the past existed, in which case it looks more like an unreflective Type-2 presupposition. The important point, however, is that the claim that the world has existed for x number of years is constitutive of the very practice of historical inquiry. The historical-inquiry domain is specialized for precisely this reason: it has more or less definite boundaries, the crossing of which constitutes something like a foul. If a nosy ‘subversive epistemologist’ (to borrow a helpful phrase from Michael Forster)—or perhaps a moon-eyed metaphysician—butts into an historical debate to ask, “But how do you know the world didn’t pop into existence five minutes ago?”, the historians have to hand a principled rationale for rejecting the question, for it lies outside the limits of the game they’re playing. The historical-inquiry game can only proceed on the basis of such presuppositions. Calling these context-constitutive presuppositions into question would entail the cessation of historical inquiry. One would begin, instead, to philosophize.

As I suggested above, it can be misleading to refer to Type-2 and Types-3 presuppositions as presuppositions. Type-2 presuppositions can seem to run ‘deeper’ than any mere presupposition. As for Type-3 presuppositions, they are taken to be true (and so not merely presupposed) by those who hold them. In the first case, ‘presupposition’ can seem too intellectual a notion; in the second case, it can seem inappropriate insofar as ‘presupposing’ seems to imply a degree of doubt or tentativeness. All of that is true enough. The rationale for nevertheless referring to ‘presuppositions’ in these cases is that that is how they appear from a philosophical standpoint.

As I’ll argue in more detail in my next post, the practice of philosophy is both historically and conceptually predicated on an initial skepticism regarding the inherent epistemic and practical authority of common life. It strives to provide, now on a purely rational basis, the explanations and justifications that it itself took away from common life. Crucial to stripping common life of epistemic and practical authority involves thematizing, and subsequently calling into question, its presuppositions. (This does not mean that philosophers are necessarily hostile to everyday presuppositions. On the contrary, I find that they are generally apologists. But qua philosophers, they seek—usually without outright admitting as much—simply to transplant everyday presuppositions into richer, more solid, and, above all, more rational ground. We can engage in combat in order to strengthen as well as to overthrow.) Philosophy adopts the same sort of attitude toward the more reflective presuppositions of specialized contexts: what the historian takes to be self-evident or indubitable, the philosopher reduces to the status of a mere presupposition.

—————————————————–

It’s hardly surprising, then, that philosophy has traditionally striven to free itself from presuppositions. We simply accept, without reasons, all sorts of things in common life as well as in other, less ‘radical’ domains of inquiry. Moreover, as context-constitutive, such presuppositions form the ground of our presupposition-contextual epistemic–doxastic practices. Given this picture, it can seem that, barring the establishment of presuppositionless knowledge, we’re doomed to irrationality—to playing mere games in the upper stories of the citadel of reason while failing, or even refusing, to investigate its foundations, to see whether the building is sound, whether it rests upon the ground of truth.

In the Republic, Plato argues that genuine knowledge must be presuppositionless: it must descend from the top of the Divided Line down. If we try to make progress bottom-up, we’re “compelled to work from assumptions, proceeding to an end-point, rather than back to an origin or first principle” (510b). He considers the example of geometry and arithmetic: “[T]here are some things they take for granted in their respective disciplines. Odd and even, figures and the three types of angle. That sort of thing. Taking these as known, they make them into assumptions. They see no need to justify them either to themselves or to anyone else. They regard them as plain to anyone. Starting from these, they then go through the rest of the argument, and finally reach, by agreed steps, that which they set out to investigate” (510c–d). Plato associates this sort of inquiry with what he simply calls “thinking” (534a). ‘Thinking’ deals with objects of knowledge, but cannot arrive at genuine knowledge itself, precisely because it cannot dispose of its presuppositions. “As for the subjects which we said did grasp some part of what really is [i.e., geometry and arithmetic]… we can now see that as long as they leave the assumptions they use untouched, without being able to give any justification for them, they are only dreaming about what is. They cannot possibly have any waking awareness of it. After all, if the first principles of a subject are something you don’t know, and the endpoint and intermediate steps are interwoven out of what you don’t know, what possible mechanism can there ever be for turning a coherence between elements of this kind into knowledge?” (533b–c). Knowledge, on the other hand, is acquired only when one achieves freedom from presuppositions: the soul “goes from an assumption to an origin or first principle which is free from assumptions” (510b). Reason “uses assumptions not as first principles, but as true ‘bases’—points to take off from, entry-points—until it gets to what is free from assumptions, and arrives at the origin or first principle of everything. This it seizes hold of, then turns round and follows the things which follow from this first principle, and so makes its way down to an end-point” (511b–c). The method of achieving presuppositionlessness Plato calls ‘dialectic’: “The dialectical method is the only one which in its determination to make itself secure proceeds by this route—doing away with its assumptions until it reaches the first principle itself” (537d).

The same commitment to presuppositionlessness can be found in Kant. As in Plato, this commitment pushes Kant to reject experience as capable of providing rational satisfaction. “[E]xperience never fully satisfies reason; it [i.e., reason] directs us ever further back in answering questions and leaves us unsatisfied as regards their full elucidation” (Prolegomena). “[R]eason does not find its satisfaction in experience, it asks about the ‘why,’ and can find a ‘because’ for a while, but not always. Therefore it ventures a step out of the field of experience and comes to ideas.” Unfortunately, the move to ‘ideas’ doesn’t help; even here, “one cannot satisfy reason,” for the ‘whys?’ never let up (Metaphysik Mrongovius). As he puts it in the first introduction to the Critique of Pure Reason, “Reason falls into this perplexity through no fault of its own. It begins from principles whose use is unavoidable in the course of experience and at the same time sufficiently warranted by it. With these principles it rises (as its nature also requires) ever higher, to more remote conditions. But since it becomes aware in this way that its business must always remain incomplete because the questions never cease, reason sees itself necessitated to take refuge in principles that overstep all possible use in experience, and yet seem so unsuspicious that even ordinary common sense agrees with them. But it thereby falls into obscurity and contradictions” (Avii–viii). In other words, the common understanding makes use of principles that, although they are taken to be unproblematic in the course of everyday life, reason (i.e., philosophy) unmasks as objectively unjustified presuppositions (cf., Critique of Pure Reason, A473/B501). Reason, which is not held in check by experience or by the contingencies of common life, strives after, and is satisfied by nothing less than, presuppositionlessness or, in Kant’s terms, the unconditioned. “[R]eason in its logical use seeks the universal condition of its judgment… [T]he proper principle of reason in general (in its logical use) is to find the unconditioned for conditioned cognitions of the understanding” (Critique of Pure Reason, A307/B364). “[R]eason demands to know the unconditioned, and therewith the totality of all conditions, for otherwise it does not cease to question, just as if nothing had yet been answered” (“What Real Progress Has Metaphysics Made…?”).

Unlike Plato, however, Kant rejects the possibility at arriving at any sort of transcendent ground of truth. Instead, he argues that we can only have knowledge within the sphere of experience. Still, experience is structured in such a way, he argues, that we can have certain knowledge of what must be the case for experience to be possible at all. (Kant calls this approach transcendental, which refers to conditions of possibility, not to ‘transcendence.’) For Kant, the quest for presuppositionless knowledge ends not in transcendence, but in the uncovering of the determinate limits of knowledge. As he puts it, reason will only be satisfied with “complete certainty”—which entails presuppositionlessness, since any lingering presuppositions could be doubted—“whether it be one of the cognition of the objects themselves or of the boundaries within which all of our cognitions of objects is enclosed” (Critique of Pure Reason, A761/B789).

There is a quite different tradition in Western philosophy, going back at least to Aristotle, that can be seen as furnishing a counterexample to my claim that philosophy strives for presuppositionlessness. It is often thought that Aristotle was not concerned with skeptical problems, that he did not consider them worthy or requiring of response or refutation. He is often taken to preempt skeptical philosophers by claiming that some of what they call ‘presuppositions’ are known to be true even though their truth cannot be demonstrated. There’s clearly something right about the latter claim at least: as Aristotle says in the Posterior Analytics, “We contend that not all knowledge is demonstrative: knowledge of the immediate premises is indemonstrable” (72b). The ‘immediate premises’ are what Aristotle calls ‘first principles.’ His argument, then, is that the truth of first principles cannot be demonstrated, yet nevertheless we can know them.

First off, I think it is clear that Aristotle’s philosophy is indeed entwined with skepticism, broadly construed (i.e., ‘subversive epistemologies’). As we’ve just seen, he presents in the Posterior Analytics an anti-skeptical argument. A similar anti-skeptical intent can be found elsewhere in the Aristotelian corpus, such as in the defense of logical laws in Metaphysics Book Gamma. And while he has far more regard than Plato does for common, prephilosophical opinion (endoxa)—often using them as starting-points for the development of his own positions—he is ultimately skeptical of endoxa, for he displays both a willingness to reject it (when it happens to be wrong) and a desire to provide it with a more rational foundation (when it happens to be right). If this is right, and if I’m right to conceptualize the entwinement of skepticism and philosophy as I’ve been doing so far, then we should find in Aristotle a commitment to the epistemic ideal of presuppositionlessness. But just as it has seemed to many that Aristotle is concerned with skepticism, so it may seem that he lacks a commitment to the epistemic ideal of presuppositionlessness. Addressing this issue in anything approaching a thorough way is impossible here. All I’m going to do is focus on the anti-skeptical position we’ve looked at from the Posterior Analytics, according to which first principles are known immediately and indemonstrably. Does this mean that Aristotle contents himself with presuppositional knowledge?

Aristotle’s argument in the Posterior Analytics anticipates—and may well have been the source of—the most powerful of all skeptical arguments, namely, the Agrippan Trilemma, according to which any attempt to justify a claim will end either in vicious circularity, infinite regress, or brute hypothesis. Aristotle rejects outright the possibility of an infinite chain of justifications. He also rejects circularity, for on his view, demonstrative knowledge relies on premises that are both prior to and better known than the conclusions derived from them. In the case of circular justifications, though, the same propositions would have to be alternatively prior and subsequent to each other, alternatively better and worse known than each other. Finally, he denies that immediately known first principles are mere hypotheses; if they were, then the most that could be concluded from them is that “if the primary things [the first principles] obtain, then so too do the things derived from them.” His way of avoiding the Trilemma is to reject the assumption that all knowledge must be demonstrable: there is a type of indemonstrable knowledge, namely, knowledge of first principles. But how do we know first principles? On this, Aristotle’s remarks are cryptic, to say the least. Such knowledge is not innate, but is said to “come to rest in the soul” as a result of “induction” from various instances of “perception” (100a–b). Are these first principles merely presupposed, or are they known? The skeptic—as well as many a dogmatist, such as Plato—will claim that they’re merely presupposed. Aristotle, however, is going to deny this. As we’ve seen, he holds that the first principles can be known, not merely hypothesized. In fact, he holds that all demonstrative knowledge rests on prior knowledge: “All teaching and all learning of an intellectual kind proceed from pre-existent knowledge” (71a). Aristotle, then, is not content with presuppositional knowledge. We can disagree over the effectiveness of his strategy, but that his strategy evinces a commitment to presuppositionlessness should be clear.

Aristotle’s brand of anti-skeptical foundationalism can be found not only in later Aristotelians, but also, I would argue, in such philosophically distant groups as the so-called commonsense philosophers. Like Aristotle, commonsense philosophy, from Thomas Reid to G.E. Moore to Jim Pryor, maintain that some things (indeed, a great many things) are simply and irrefutably known and so cannot be genuinely called into question. These privileged bits of knowledge are indubitable, immovable, self-evident.

The problem—as Ambroise Beirce underlines in the entry on “Self-Evident” in The Devil’s Dictionary—is that, when scrutinized, self-evident seems to mean merely that which is “[e]vident to one’s self and to nobody else.”

—————————————————–

More recently, many philosophers have questioned the viability or necessity of attaining freedom from presuppositions. It has been argued, for instance by Robert Stalnaker, that ‘pragmatic presuppositions’ are a necessary condition for discourse (see his Content and Context, p. 49). In On Certainty, Wittgenstein seems to make a similar argument: “[T]he questions that we raise and our doubts depend on the fact that some propositions are exempt from doubt, are as it were like hinges on which those turn” (§341). But, Wittgenstein adds, “[I]t isn’t that the situation is like this: We just can’t investigate everything, and for that reason we are forced to rest content with assumption. If I want the door to turn, the hinges must stay put” (§343). “It may be that all enquiry on our part is set so as to exempt certain propositions from doubt, if they are ever formulated. They lie apart from the route travelled by enquiry” (§88).

I’ll return to some of these ideas in subsequent posts. For now, I want merely to point out that, on the picture I’m presenting, all domains of inquiry are presupposition-contextual from a philosophical standpoint. It may be that determinate intellectual or dialogic progress can only be made against a fixed background of unquestioned commitments. If this is so, and if I’m right that philosophy is traditionally committed to the ideal of presuppositionlessness, then we would have the beginnings of an explanation of the apparent interminability of philosophical inquiries. Philosophy, even when explicitly committed to presuppositionlessness, often proceeds presupposition-contextually, such as when it mistakes its presuppositions for self-evident first principles. If progress cannot be made presuppositionlessly, then the only way for philosophy to make progress would be somehow to forestall the possibility of calling into question the presuppositions structuring a given philosophical discourse. The problem with this is that philosophy does not appear to have any determinate boundaries, such as those that structure historical inquiries. Philosophy, in short, lacks a principled means of calling “Foul!” Philosophers are free, qua philosophers, to call into question any presupposition whatsoever. It seems, in fact, that the task of securing a determinate set of presuppositions for philosophy—a presupposition-set that would allow philosophy to make determinate progress—is actually incoherent, for it seems that the only rational way to forestall the possibility of calling into question context-constitutive presuppositions is to ground or justify those presuppositions; yet doing so is tantamount to stripping those presuppositions of their status as presuppositions.

In the Apology for Raymond Sebond, Michel de Montaigne wrote that “[i]t is very easy, upon accepted foundations, to build what you please… Whoever is believed in his presuppositions, he is our master and our God; he will plant his foundations so broad and easy that by them he will be able to raise us, if he wants, up to the clouds… If you happen to crash this barrier in which lies the principal error, immediately [philosophical dogmatists] have this maxim in their mouth, that there is no arguing against people who deny first principles.” In Montaigne’s view, “there cannot be first principals for men,” given the limits of our reason. “To those who fight by presupposition, we must presuppose the opposite of the same axiom we are disputing about. For every human presupposition and every enunciation has as much authority as another, unless reason shows the difference between them. Thus they must all be put in the scales, and first of all the general ones, and those which tyrannize over us.” For as Kant wrote, “[R]eason has no dictatorial authority; its verdict is always simply the agreement of free citizens, of whom each one must be permitted to express, without holding back, his objections and even his veto” (Critique of Pure Reason, A738–9/B766–7).

March 18, 2013

Three Roses: The Sack of Nevegas

Hello all! Roger Eichorn here again.

Sorry for the delay in posting the second of my “Metaphilosophical Reflections.” I hoped to have it ready today. Instead I’ve blundered my way into doing a bunch of reading to fill a gap in the story I want to tell. I should have the second post up tomorrow or the next day. Currently, the plan has me writing five posts in total. I expect to have all of them up by the end of the month.

As for my fantasy writing, I’ve decided to keep it simple: I’m going to post two ‘Bonus Scenes’ from later sections of the book (that is, later than the first three chapters, which can be read here). The scenes are continuous and relatively self-contained: they center on a character (Davyd Carverus) who was introduced earlier but was never focused on. Thus, the scenes represent the beginning of Carverus’s ‘viewpoint arc,’ and should be relatively easy to follow even pulled from the rest of the story. You can find the first Bonus Scene here. I’ve included the first few paragraph below:

—————————————

1546, Moon of Dathiel (Late Spring), Nevegas

Davyd Carverus would later swear that he had seen the arrow before it struck—its arc somehow plucked from swirling chaos, as though his gaze were pinned to the fault line of fate.

Under the late spring sun, the arrow, fired from the walls of the Holy City of Nevegas, bloomed in the neck of the Duke of Iseldas. The duke teetered, his arms pinwheeling, and fell to the mud at his horse’s hooves. The damnable fool was wearing his famous white cloak, which marked him as commander of the imperial army. It was useful for one’s troops to be able to identify their leader from a distance, but such information was equally exploitable by one’s enemies, a truth the duke learned in most dire fashion, once and for all, in the final choking moments of his life.

A reverent, almost superstitious hush fell within the ring of men nearest the duke—but only for a moment. Nothing would prevent the imperial force from storming the walls, not stone nor steel nor the roar of the defenders’ cannon batteries. And now, with Iseldas dead, nothing would prevent the sacking—the utter despoiling—of the city that lay beyond…

March 15, 2013

Metaphilosophical Reflections I: Preliminaries

“Men have, as it were, a calling to use their reason socially… From this it follows naturally that everyone who has the principium of conceit, that the judgments of others are for him utterly dispensable in the use of his own reason and for the cognition of truth, thinks in a very bad and blameworthy way.”

– Immanuel Kant, Blomberg Logic

—————————————

Hello all! This is Roger Eichorn. I’ll be guest-blogging here for the remainder of the month, while Scott and his family are on vacation.

Like Scott, I’m here to peddle two sorts of product: philosophy and fantasy fiction (though, also like Scott, I find myself increasingly unable to tell them apart!). On the philosophy side of things, I intend to present a series of posts that will introduce my metaphilosophy, that is, my philosophy of philosophy. My metaphilosophical speculations bridge the systematic and the historical sides of my philosophical interests. Thus, I’ll have occasion both to discuss the history of philosophy and to indulge in a bit of first-order philosophizing of my own.

As for my fantasy fiction, I hope that my front-page posts will drum up some renewed interest in the chapters that are already posted here. If time and inspiration strikes, I may devote a front-page post or two to my fantasy work. I’m not sure what form such posts would take. I’d be interested to hear people’s thoughts on what they’d be most interested in reading. Three options have occurred to me as likely possibilities: (i) I could post selections from later parts of the book, that is, later than the three chapters already posted here; (ii) I could try to write short, standalone-ish companion pieces, like Scott’s Atrocity Tales; or (iii) I could write ‘historical’ or ‘metaphysical’ posts about the world in which the story takes place, like the sort of material one might find in an Appendix.

Obviously, (i) would be the easiest. In a perfect world, I would love to do (ii)—but it would require the greatest expenditure of time and energy. Moreover, I’ve never been good at short fiction. My ‘short story’ ideas are invariably novel-sized ideas—and my ‘book’ ideas are invariably ‘series-of-books’ ideas! It would certainly be an interesting experiment, but I would run a serious risk of falling on my compositional face. As for (iii), it would fall somewhere between (i) and (ii) on the ‘difficulty’ / ‘risk-of-creative-failure’ axis.

Now, in the remainder of this post, I’d like to raise and discuss some of the questions that motivate my metaphilosophical reflections. Most generally, there are fundamental questions such as “What is philosophy?” and “How is philosophy related to other domains of intellectual inquiry?” In conversation, I often get at these issues by asking, “Just what exactly do philosophers think they’re doing when they philosophize?” If I’m allowed to go on, I often elaborate thusly: “I mean, what do philosophers hope to achieve? And why do they suppose that their methods—whatever those happen to be—are apt for achieving those ends? Why those methods and not others?”

It’s interesting that there seems to be no uncontroversial answers to questions of this sort. The same cannot be said of most, if not all, other established domains of intellectual inquiry. I mean, sure, historians or sociologists or physicists might give different answers to these sorts of questions, but there is likely to be a more or less easily achieved equilibrium between their differing answers. Not so in philosophy. As for methodology, there might be (and undoubtedly is) real disagreement among, say, historians about how best to pursue historical investigations; but on closer inspection, those methodological disagreements are likely to be based on a broad foundation of agreement such that their disagreements are relatively superficial. Not so in philosophy.

This should not be taken to mean that there is no metaphilosophical harmony among philosophers. There is. But it is local—across both time and space—to a degree that far exceeds that of other domains of intellectual inquiry. Moreover, what harmony does exist seems accidental (as opposed to ‘essential’), in the sense that it doesn’t appear to arise from any intrinsic feature of philosophy itself. In most cases, it doesn’t even arise from a shared explicit commitment to some sort of metaphilosophical ‘self-understanding.’ In most cases, it seems rather to be a function of where and with whom one first studied philosophy, or to be the residue of a ‘politics of exclusion’ perpetuated by philosophers either by (a) reading (or assigning) only certain sorts of texts, or (b) actively looking down upon certain other sorts of texts (and those who read or assign them).

In short, compared to other intellectual disciplines, philosophy-as-such seems untethered, curiously free of any definitive theoretical or conceptual commitments. (I say ‘philosophy-as-such’ to emphasize my unwillingness to play the inclusion/exclusion game. That is, at the level of abstraction from which I’m beginning, there is no basis for claiming that person x, who calls herself a philosopher, really is a philosopher, whereas person y, who also calls herself a philosopher, isn’t really a philosopher. One finds such accusations being made, for instance, across the notorious—and notoriously unhelpful, from an explanatory standpoint—Analytic–Continental divide.)

Another question that motivates my metaphilosophical reflections concerns the apparent interminability of philosophical disputes. It is often claimed, especially by those unsympathetic to philosophy, that philosophy hasn’t made any progress in 2,500 years. This is frequently contrasted with the startling successes of mathematics and the hard sciences in the modern era. Often, pointing to this contrast is considered sufficient to prove philosophy’s intellectual bankruptcy. As will become apparent over the course of this series of posts—and as longtime TPB’ers already know—I’m an unlikely candidate for Champion of Philosophy, given that I’m a card-carrying Skeptic. Even so, I think that the common picture of ‘futile philosophy’ alongside ‘all-conquering science’ is deeply naive.

To begin with, there’s the historical fact that all the sciences—indeed, virtually every branch of intellectual inquiry—was once part of philosophy proper. Far from having made no progress in 2,500 years, philosophy has in fact succeeded in spawning every branch of the modern academic tree. (It’s telling that all Ph.D’s are doctors of philosophy.) Furthermore, as I’m going to argue in subsequent posts, at the level of abstraction at which philosophical disputes are interminable, all disputes are interminable, regardless whether the disputes’ subject matter is thought of as belonging to ‘philosophy.’ In other words, the interminability of philosophical disputes points up a general fact about human cognition, not a fact peculiar to some specialized domain of inquiry called ‘philosophy.’ Indeed, as I’ve suggested above, there is a sense in which no such domain of inquiry exists. There are no clear boundaries, no clear definitions, of ‘philosophy.’ Ultimately, I want to argue that ‘philosophical reflection’ is distinguished from other forms of intellectual inquiry neither by its subject matter nor by its methodology, but rather by its radicality (which should be understood literally, as pertaining to roots, an etymological link that gives us the word ‘radish’). In subsequent posts, I’ll connect the ‘radicality’ of philosophy to the idea of presuppositionlessness, which I take to be the concept by means of which philosophy can be distinguished from, and related to, other domains of intellectual inquiry.

The metaphilosophical problem of interminability connects up with another question I’m interested in, one that seems especially pertinent given the dust-up in the discussion thread of Scott’s latest post on the Blind Brain Theory: namely, the philosophical significance of disagreement, specifically disagreement among epistemic peers. I may or may not take up this issue to the extent it deserves, as it’s secondary to the main points I want to make. That’s why I want to flag it here as an issue that should be kept in mind as we proceed.

There’s a sense in which the interminability of philosophical inquiries seems to be a function of—or at least to be correlated to—the interminability of philosophical disagreements. On the other hand, unless we subscribe to a consensus theory of truth (which should be kept separate from a consensus criterion of truth) it seems that, in and of itself, disagreement is epistemically unproblematic. After all, if person x is right about p and person y is wrong about p, then the fact that persons x and y continue to disagree about p has no bearing on the truth or falsity of p. Yet even if this is right (which—again, barring a consensus theory of truth—it seems to be), it strikes me as wrongheaded in the extreme to deny that persistent, irresolvable disagreement among epistemic peers is epistemically problematic (in some sense, at least). In my view, while disagreement may be unproblematic with respect to theories of truth (i.e., with regard to truth as such), it is deeply problematic with respect to criteria of truth. In other words, even if disagreement does not stand in the way of us being right, it does (at least among epistemic peers) stand in the way of us knowing we’re right.

Kant saw this clearly. “[R]eason,” he wrote, “has no dictatorial authority; its verdict is always simply the agreement of free citizens, of whom each one must be permitted to express, without holding back, his objections and even his veto” (Critique of Pure Reason, A738–9/B766–7). He refers to “the comparison of our judgments with those of others” as a “touchstone of truth,” while “[t]he incompatibility of the judgments of others with our own is… an external mark of error” (Jäsche Logic). And in the Blomberg Logic, he claims that “[a]s long as there is controversy concerning a thing… as long as disputes are exchanged by this side or the other, the thing is not yet settled at all.” Underlying these claims is a commitment to the view that human beings share in one and the same common humanity. There is no principled way, at the least at the outset of a dispute, to privilege one person’s opinion over that of another, for we are all human. If we genuinely know that we know that p—that is, if we have genuine reflective knowledge that p and not simply an unverified (though possibly true) belief that p—then we should, it seems, be able to demonstrate to others that we know p such that they will come to recognize the truth of p and come to believe—and know—p as well.

In many domains of inquiry—including that vast, amorphous domain I call ‘common life,’ which simply refers to our everyday world, in which many things are routinely inquired into, etc.—there are more or less established means of arriving at the sort of rational consensus Kant has in mind. (A prime generator of consensus in today’s world is Google, as when someone interrupts a dispute by saying, “Just Google it!”) An example can be found in Plato’s Meno, in which Socrates teaches (‘demonstrates’ the truth of) geometric axioms to a slave-boy. Now, looked at more closely, available mechanisms for generating rational consensus are all questionable with respect to whether or not they are productive of genuine knowledge. (Google certainly is.) But even so, it is peculiar that philosophy is a domain of inquiry that, as a whole, has no generally agreed upon methods for generating consensus. Again, as I suggested above, I think this points up not a shortcoming of philosophy as such, but rather a shortcoming of human cognition as such. Hence, no matter how well-established a given ‘regime of truth’ may be, intellectual history suggests that none is immune to revision, reconceptualization, and rejection. Even those geometric proofs that Plato taught the slave-boy can be called into question by non-Euclidian geometries.

So what is going on when a number of people, all possessing at least the minimum intellectual capabilities necessary to grasp the matter in hand, cannot agree? My answer, in short, is that these people are working on the basis of differing sets of underlying presuppositions, meaning that their disagreement is rooted in a deeper disagreement about which they are not actively arguing. Hence, they are unable to make progress toward consensus, for the roots of their disagreement go deeper than their debate does.

Depending on how much conceptual baggage one loads onto this initial characterization, the view will likely seem either obviously (and so uninterestingly) true or else overly (and hence uninterestingly) simplistic. There is a sense in which I agree with the ‘obviously-true’ charge—though I think that the consequences of the view, once thought out, are far from obvious. As for the ‘overly-simplistic’ charge: while I agree that the view is literally neat, I think it will become clear, once it’s looked at more closely, that the apparent simplicity of the view’s initial statement masks all sorts of hidden complexities.

One thing my view does not do is provide a means of escaping dialogic impasses, if ‘escape’ means generating consensus. The most I hope for is to point toward the possibility of reorientation, the possibility of coming to view the epistemic–doxastic state both of ourselves and of others—and hence the nature of our disagreements—differently such that we don’t give in to the tempting move Wittgenstein noted when he wrote, “Where two principles really do meet which cannot be reconciled with one another, then each man declares the other a fool and a heretic” (On Certainty, §611).

With respect to the charge of foolishness, we would do better to recognize that we are all fools. As Michel de Montaigne wrote, in the voice of the Delphic Oracle, “There is not a single thing as empty and needy as you [i.e., Man], who embrace the universe: you are the investigator without knowledge, the magistrate without jurisdiction, and all in all, the fool of the farce” (Of Vanity).

With respect to the charge of heresy, we would do better to question our own judgment at least as strongly as we question that of the person with whom we disagree. Again quoting Montaigne: “… it is putting a very high price on one’s conjectures to have a man roasted alive because of them” (Of Experience).

I look forward to working through some of these ideas with all of you over the next couple weeks. I’ll do my best to keep up with the comments. Thanks for reading!

March 11, 2013

The Ptolemaic Restoration: Object Oriented Whatevery and Kant’s Copernican Revolution

“And now, after all methods, so it is believed, have been tried and found wanting, the prevailing mood is that of weariness and complete indifferentism” –Immanuel Kant, The Critique of Pure Reason

.

So, continuing my whirlwind interrogation of the new Continental materialisms, I want to turn to Object-Oriented Whatevery via the lens of Levi Bryant’s, “The Ontic Principle: Outline of an Object Oriented Ontology.” As always, I need to impress I’m a tourist and not a native of these philosophical climes, so I sincerely encourage anyone who comes across what seems to be an obvious misreading on my part to expose the offending claims in the comments. My goals, once again, are both critical and constructive: in the course of showing you why I think it’s obvious that Bryant cannot deliver the goods as advertised, I want to demonstrate the explanatory reach and power of BBT, not as any kind of theoretical panacea, but as a system of empirically tractable claims that, in the tradition of scientific theory more generally, are quite indifferent to what we want to be the case. Like I’ve said before, the conclusions suggested by BBT are so radical as to almost qualify as a reductio, were it not for the fact that a reductio is precisely the way it would appear were it true. And besides, as I hope some of you are at least beginning to see, there is something genuinely uncanny about its explanatory power.

Essentially I want to argue that BBT may actually deliver on what Bryant advertises–a way out of the philosophical impasses of the tradition, even a ‘flat ontology’ rationalized via difference!–though its consequences are nowhere near so kind. I’ve corresponded with Levi in the past, and he strikes me as a good egg. It’s his position I find baffling. With any luck he’ll do what Hagglund found incapable: acknowledge, expose, and contradict–inject some much-needed larva into Three Pound Brain!

Bryant begins, not by rehearsing the primary motive of critical philosophy–namely, how the failure of dogmatic philosophy to produce theoretical knowledge convinced philosophers to examine knowing–but rather the claim of critical philosophy, the notion “that prior to any claims about the nature of reality, prior to any speculation about objects or being, we must first secure a foundation for knowledge and our access to beings” (262). This allows him, quite without irony, to rehearse what he takes to be the primary motive of Object Oriented Ontology: the failure of critical philosophy to produce theoretical knowledge. “Faced with such a bewildering philosophical situation,” he writes, “what if we were to imagine ourselves as proceeding naively and pre-critically as first philosophers, pretending that the last three hundred years of philosophy had not taken place or that the proper point of entry into philosophical speculation was not the question of access?” In other words, given the failure of three centuries of critical philosophy to produce theoretical knowledge, perhaps the time has come to embrace, as best we can, the two millennia of dogmatic failure that preceded it.

Thus he motivates a turn away from the subject of knowledge to the object of knowledge, from the epistemological to the ontological–as we should, apparently, given that the object comes first. After all, as Heidegger made ‘clear,’ “questions of knowledge are already premised on a pre-ontological comprehension of being” (263). Unlike Heidegger, however, who saw in this pre-ontological comprehension an interpretative basis for theorizing a collapse of subject and object (which quickly came to resemble a conceptually retooled subject), Bryant sees a call to theorize, in tentative fashion, the ‘ultimate generalities’ that objectively organize the world. Premier among these tentative ultimate generalities, he asserts, is difference. This leads Bryant to pose what he calls the ‘Ontic Principle,’ the claim “that ‘to be’ is to make or produce a difference” (263).

Why should difference be our ‘fundamental principle’? Well, because all epistemology presupposes it. As he writes:

Paradoxically it therefore follows that epistemology cannot be first philosophy. Insofar as the question of knowledge presupposes a pre-epistemological comprehension of difference, the question of knowledge always comes second in relation to the metaphysical or ontological priority of difference. As such, there can be no question of securing the grounds of knowledge in advance or prior to an actual engagement with difference. 265

To which the reader might be tempted to ask, How do you know?

This is one of those junctures that makes me (if only momentarily) appreciate Derrida and his tireless attempts to show philosophers the inextricable co-implication of dokein and krinein. The easiest way to illustrate it here is to simply wonder aloud what is ‘presupposed’ by difference. If difference comes before epistemology because epistemology ‘presupposes’ difference as its ‘condition,’ and if the ultimate ‘first first,’ no matter how ‘tentative,’ is what we are after, then we should inquire into the presuppositions of our alleged presupposition. Since there can be no difference without the negation of some prior identity, for instance, perhaps we should choose identity–snub Heraclitus and do a few rails with Parmenides.

Can counterarguments be adduced against the ontological primacy of identity? Of course they can (and Bryant helps himself to a few), just as counterarguments can be adduced against those counterarguments, and so on and so on. In other words, if critical philosophy is motivated by the failure of dogmatic philosophy to produce theoretical knowledge, and if Bryant’s neo-dogmatic philosophy is motivated by the failure of critical philosophy to produce theoretical knowledge, then perhaps we should skip the ‘and centuries passed’ part, assume the failure of neo-dogmatism to produce theoretical knowledge and, crossing our fingers, simply leap straight into neo-critical philosophy.

Far from ‘escaping’ or ‘solving’ anything, this strategy–quite obviously in my opinion–perpetrates the very process it sets out to redress. Let’s call this state of oscillating institutional emphasis on the subject and the object of knowledge, ‘correlativity.’ And let’s call ‘correlativism’ the idea according to which philosophy can only ever prioritize either subject or object and never any term other than these two.

Why has correlativism so dominated philosophy since its Modern inception? I actually think I can give a naturalistic answer to this question. The dichotomy of subject and object, of course, possesses a myriad of conceptual attenuations, binaries such as thought and being, mind and body, spirit and matter, ideal and real, epistemology and ontology, to name but a few of the oppositions that have constrained the possibilities of coherent, speculative thought for centuries now. There are other binaries, certainly, categorical conceptual oppositions (such as that between difference and identity) that a number of philosophers (like Heidegger) have recruited in various attempts to think beyond subjectivity and objectivity, only to find themselves, inexorably it seems, re-inscribed within the logic of ‘correlativism.’ In this sense, I will be following a very well-trodden path, though one quite different than the one proposed by Bryant above–or so I like to think.

The primary problem I see with Bryant’s approach is that it takes the failure of critical philosophy to produce theoretical knowledge to obviate the need to answer the primary question that it sought to answer, which is, namely, the question of securing speculative truth despite the limitations of our nature. We are afflicted with numerous ‘cognitive scandals,’ basic questions it seems we should be able to answer but for whatever reason cannot. What is the good? Does the external world exist? What is beauty? Does the past exist? What is justice? Do other minds exist? What is consciousness? No matter how many answers we throw at these and other questions, the skeptic always seems to carry the day–and handily.

For whatever reason, we lack the capacity to decisively answer these questions. When it comes to the problems of critical philosophy, Bryant would have you focus on the ‘critical’ and to overlook the ‘philosophy.’ What precisely failed when it came to critical philosophy? Given the manner it seeks to redress the failure of dogmatic philosophy, the more obvious answer (by far one would think) is philosophy. And indeed, the more cognitive psychology learns about human reasoning, the more understandable the generational failure of philosophy to produce theoretical knowledge becomes. Human beings are theoretically incompetent, plain and simple. Doubtless we have the capacity to theorize, but it is a capacity that evolved long before our theories could exhibit any accuracy. Whatever fitness it rendered our ancestors had precious little to do with theoretical ‘discovery.’ Science would not represent the signature institutional achievement of our times were it otherwise.

In all likelihood, the critical impulse, the call for reason to critique reason, had no special part to play in critical philosophy’s failure to secure theoretical knowledge. So why then did it fail to improve the lot of philosophy? Well, who’s to say it hasn’t? Perhaps it improved the cognitive prospects of philosophy in a manner that philosophy has yet to discern. It’s worth recalling that for Kant, the project of critique was in an important sense continuous with the greater enterprise of Enlightenment. Noting the power of mathematics and natural science, he writes:

Their success should incline us, at least by way of experiment, to imitate their procedure, so far as the analogy which, as species of rational knowledge, they bear to metaphysics may commit. Hitherto it has been assumed that all our knowledge must conform to objects. But all attempts to extend our knowledge of objects by establishing something in regard to them a priori, by means of concepts, have ended in failure. We must therefore make trial of whether we may not have more success in the tasks of metaphysics, if we suppose that objects must conform to our knowledge. This would agree better with what is desired, namely, that it should be possible to have knowledge of objects a priori, determining something in regard to them prior to their being given. We should then be proceeding precisely on the lines of Copernicus’ primary hypothesis. Failing of satisfactory progress in explaining the movements of the heavenly bodies on the supposition that they all revolved around the spectator, he tried whether he might not have better success if made the spectator to revolve and the stars to remain at rest. A similar experiment can be tried in metaphysics, as regards the intuition of objects. (Critique of Pure Reason, 22)

If it is the case that the sciences more or less monopolize theoretical cognition, then the most reasonable way for reason to critique reason is via the sciences. The problem confronting Kant, however, was nothing less than the problem confronting all inquiries into cognition until very recently: the technical and theoretical intractability of the brain. So Kant was forced to rely on theoretical reason absent the methodologies of natural science. In other words, he was forced to conceive critique as more philosophy, and this presumably, is why his project ultimately failed.