Justin Taylor's Blog, page 85

February 10, 2015

Jim Crow, Civil Rights, and Southern White Evangelicals: A Historians Forum (Carolyn Dupont)

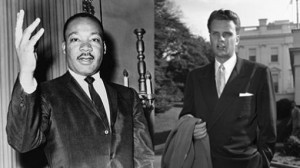

The movie Selma reminds us that white clergy protested and marched with Martin Luther King Jr. and other African Americans in the 1960s on behalf of Civil Rights. But it also reminds us—as Anthony Bradley recently observed—that many of those clergy were from the North and were Protestant mainliners, Greek Orthodox, Jewish, and Roman Catholic. One has to wonder: where were the conservative evangelicals?

I recently posed the following questions to several historians who have studied segregation and religion in the Southern United States during the years of Jim Crow and during the Civil Rights Movement.

Did white evangelicals in the South respond to the civil rights movement in different ways from their counterparts in other parts of the United States? Is it fair to say that the majority not only refused to engage but actively opposed it? If so, what historical forces formed their particular responses and attitudes? How did evangelical theologies form or undermine their engagement?

I will be posting the historians’ answers at this blog throughout the week. The first three historians were Matt Hall (SBC), Sean Lucas (PCA), and Rusty Hawkins (Wesleyan).

Carolyn Renée Dupont is assistant professor of history at Eastern Kentucky University in Richmond, KY, and the author of the book, Mississippi Praying: Southern White Evangelicals and the Civil Rights Movement, 1945-1975 (NYU Press, 2013).

Carolyn Renée Dupont is assistant professor of history at Eastern Kentucky University in Richmond, KY, and the author of the book, Mississippi Praying: Southern White Evangelicals and the Civil Rights Movement, 1945-1975 (NYU Press, 2013).

* * *

Simply put, any suggestion that the religion of southern whites aided the civil rights struggle grossly perverts the past. While many evangelicals displayed kindness in their personal dealings with blacks, most nonetheless enthusiastically defended a system designed to advantage whites and to correspondingly disadvantage African Americans at every turn. It is true that every major denomination in the United States embraced the Supreme Court’s Brown v Board of Education decision that declared segregated schools unconstitutional. However, the picture looks very different at the local level, where southern evangelicals more often fought ferociously against any effort to dismantle the system of white supremacy. While my research has focused on evangelicals in the state of Mississippi, much of what I learned would apply to other parts of the South. The unique factors of other states or regions might make the landscape somewhat different.

Ways in Which Evangelicals Resisted Black Equality

Evangelicals resisted black equality in many ways. Some ministers preached an overt biblical sanction for segregation. Most preachers took a more oblique approach, remaining silent about the subject of black equality while condemning faith-based civil rights activism as “a prostitution of the church for political purposes.” Most southern Christians did not regard segregation as a sin, and they resented those who criticized their “way of life.” They rejected efforts from their denominations to educate them into more enlightened racial views and frequently withheld funds from agencies in the church who advocated for equality. They sacked pastors who embraced any aspect of the freedom struggle. They formed lay organizations to keep their churches segregated; many individual congregations adopted formal resolutions instructing their deacons to reject black worshippers. When school integration became unavoidable, white evangelicals forsook the public schools in droves in favor of new private schools sponsored by their churches.

Evangelicals resisted black equality in many ways. Some ministers preached an overt biblical sanction for segregation. Most preachers took a more oblique approach, remaining silent about the subject of black equality while condemning faith-based civil rights activism as “a prostitution of the church for political purposes.” Most southern Christians did not regard segregation as a sin, and they resented those who criticized their “way of life.” They rejected efforts from their denominations to educate them into more enlightened racial views and frequently withheld funds from agencies in the church who advocated for equality. They sacked pastors who embraced any aspect of the freedom struggle. They formed lay organizations to keep their churches segregated; many individual congregations adopted formal resolutions instructing their deacons to reject black worshippers. When school integration became unavoidable, white evangelicals forsook the public schools in droves in favor of new private schools sponsored by their churches.

Exceptions to the Generalizations

Certainly, we do well to remember the few notable exceptions to these generalizations. Some progressives challenged white supremacy, but they remained clustered at the seminaries, denominational headquarters, and on the mission field. Pastors occasionally spoke out, but their congregations often responded with ferocious censure, a reaction that demonstrates the sentiments of the masses. Some white evangelicals initiated noble efforts like rebuilding black churches that white extremists had burned. However, we should not confuse such efforts with advocacy for the end of segregation. As the historian Charles Payne has noted, often these endeavors demonstrate objections “to the use of violence in the defense of white supremacy, not to white supremacy itself.”

Northern Christians and Segregation

Your question raises the issue of northern Christians and their responses to the demise of segregation. Because photographs of events like the Selma March feature white ministers, we often assume that northern people of faith actively embraced the movement. This assumption needs investigating. It is true that northern ministers participated in the southern struggle, but they represented the least evangelical and most “liberal” elements in American religion. They came largely from the ranks of the Episcopal, Presbyterian (UPCUSA), Unitarian, Disciples of Christ and Methodist faiths (and from the “liberals” within those faiths), the very branches of American Protestantism that evangelicals have decried for their misguided theology. Furthermore, clerical support for the movement did not necessarily translate to the support of rank-and-file church members. My own preliminary research into the question of northern Christians’ responses to the movement indicates that a deep lay-clerical divide ran through northern congregations when it came to issues of black equality. Some northern ministers encountered serious opposition from their congregations when they advocated for black equality.

Evangelical Theology

Evangelical theology itself undermined whites’ ability to constructively engage with the demands of black activists. Generally speaking, the most theologically conservative Christians often opposed the movement for black equality most vigorously. Evangelicalism focused overwhelmingly on regenerating the individual and depicted all social problems as merely the sum of individual problems. Thus, they blamed blacks themselves for failing to equal the standards of whites, and could not grasp how segregated and unfair institutions erected insurmountable obstacles to black aspirations. In evangelical thinking, salvation, not social change, offered the answer to black failures and frustrations. However, the salvation of every person in the entire country could not correct the problems of inferior education, limited economic opportunities, discriminatory legal arrangements, and a host of other systems that rendered black Americans second-class citizens. These entrenched and systemic injustices required change in structures, not in individuals.

Moral Suasion and Social Change

Finally, the role that religion played in thwarting the civil rights struggle raises important questions about the effectiveness of moral suasion in creating social change. Moral suasion often proves one of the least effective ways to create change. People too easily distort, circumvent, rationalize or dispatched with moral arguments. Individuals with a vested interest in a system—as whites had (and have) in the racial hierarchy—often fail to grasp the evils of that system and will fight mightily to preserve it. And perhaps that is the bottom line: whites have benefitted from America’s racial hierarchy, and it should not really surprise us that white religious traditions have shored up these advantages. Nor should it surprise us that religion did not help pull them down.

Editors’ note: The 2015 Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission Leadership Summit, sponsored by The Gospel Coalition, will address “The Gospel and Racial Reconciliation” to equip Christians to apply the gospel on these issues with convictional kindness in their communities, their families, and their churches. This event will be held in Nashville on March 26 and 27, 2015. To learn more go here. Save 20 percent when you use the code TGC20.

February 9, 2015

Proverbs for Publishing

James K. A. Smith, editor of Comment magazine, reflects on the publishing of journals:

I want to begin at 30,000 feet, thinking about the “big picture” of why we’re doing what we’re doing and then slowly descend to some maxims that are at least a little closer to the ground of practicality. You might just think of these as a collection of proverbs from an editor in media res.

Here are his five big-picture exhortations:

Fill the Earth

Target Influencers

Curate the World

Publish to be Overheard

Extend the Sacramental

He then offers four concrete principles editors should keep in mind, and I think they are worth quoting at length:

Always Be Editing | Editing isn’t just an assignment or a task; it’s kind of a way of life. You are always on the lookout. You need to be both fueling your own imagination [I’ll talk more about this tomorrow] and looking out on the world. You need to be both investing in your knowledge and deepening your convictions while curating the world for your readers. You need to keep an ear to the ground to discern what we need to be talking about it but also keep an eye on the horizon to see the up-and-coming writers who are going to help us winsomely make sense of our world. You don’t “do” editing; you are an editor.

Take Joy in Others | A good editor is someone who finds joy in fostering the work of others. If you always need to be center stage, or if you always need to get credit, you won’t be a very good editor. Much of what an editor does never sees the light of day. The labor of conceiving, crafting, and critique articles alongside their authors will sometimes be thankless. But if you’re a good editor, your writers should be able to concede that despite the fact you pushed back on them, and half of the first draft is on the cutting room floor, the article is now better. No reader is ever going to know your role in that. To be an editor is to take joy in being the skeleton not the skin.

Ideas Matter Too Much to Tolerate Bad Writing | You don’t have to choose between form and content. And you certainly shouldn’t choose one over the other. Our incarnational or sacramental conviction means, in some sense, that we eschew the very distinction between form and content. Good form is its own kind of thinking; clear, powerful, winsome, captivating writing is an argument.

Here’s the disheartening realization I’ve had since becoming an editor: there just aren’t that many Christian intellectuals who are good writers. I hope that doesn’t sound arrogant or dismissive. But it has been my experience: there are hoards of scholars who wouldn’t know a winsome sentence if it hit them upside the head. And there are hoards of bloggers who traffic in the poignant turn of phrase but have nothing to say. The club of thoughtful Christian cultural commenters who are also good writers is discouragingly small. [Here’s a plug for all of you: please become the solution to this problem!]

Editors need to have the sensibility to recognize good (and bad) writing, and then the courage to both demand and cultivate winsome writing from authors. Now, you can save yourself a lot of time and frustration by just identifying writers who already have these gifts. But you can also cultivate such writers by investing in the process. I’m convinced that any good author welcomes such editing. (To be edited is to be loved, I tell my authors.)

Resist Easy Metrics | How do you know if you are successful as an editor and as a magazine? It’s harder than you might think. This is in part because the sort of cultural influence exercised by a magazine can often be a long game—it’s like growing an oak tree rather than growing asparagus. The fruit of your labors might even be enjoyed by your successors. Measuring success for such ventures is incredibly difficult. You often won’t know the impact you’re having.

I don’t want to give excuses for retreating to the anecdotal or insulating our endeavors from accountability. It’s just that there is something unquantifiable about the sort of cultural work we’re talking about.

At the very least I know this: Comboxes and social media are not barometers of influence; they are just easy metrics of popularity. Those are two very different things. Don’t judge your influence by page views or “Likes” or retweets. I know this is easier said than done. But we need to resist the cheap, quick feedback of a click-bait culture. It’s heartbreaking to watch previously thoughtful magazines slowly become little more than Facebook feeds clamoring for emotive responses. I would trade 10,000 “likes” for one substantive engagement from a reader who is—or one day will be—a thought leader in society.

You can read the whole thing here.

Jim Crow, Civil Rights, and Southern White Evangelicals: A Historians Forum (Rusty Hawkins)

The movie Selma reminds us that white clergy protested and marched with Martin Luther King Jr. and other African Americans in the 1960s on behalf of Civil Rights. But it also reminds us—as Anthony Bradley recently observed—that many of those clergy were from the North and were Protestant mainliners, Greek Orthodox, Jewish, and Roman Catholic. One has to wonder: where where the conservative evangelicals?

I recently posed the following questions to several historians who have studied segregation and religion in the Southern United States during the years of Jim Crow and during the Civil Rights Movement.

Did white evangelicals in the South respond to the Civil Rights Movement in different ways from their counterparts in other parts of the United States? Is it fair to say that the majority not only refused to engage but actively opposed it? If so, what historical forces formed their particular responses and attitudes? How did evangelical theologies form or undermine their engagement?

The first two historians were Matt Hall (SBC) and Sean Lucas (PCA). Today we welcome a Wesleyan to the blog. I will post the remaining two this week.

J. Russell (Rusty) Hawkins (PhD, Rice University) is an associate professor of humanities and history at Indiana Wesleyan University. He is currently finishing a book manuscript titled Sacred Segregation: White Evangelicals and Civil Rights in South Carolina (Louisiana State University Press, forthcoming), and is the co-editor of Christians and the Color Line: Race and Religion after Divided by Faith (Oxford University Press, 2013). He has also begun researching a new project on the white flight of churches from urban America in the second half of the twentieth century.

J. Russell (Rusty) Hawkins (PhD, Rice University) is an associate professor of humanities and history at Indiana Wesleyan University. He is currently finishing a book manuscript titled Sacred Segregation: White Evangelicals and Civil Rights in South Carolina (Louisiana State University Press, forthcoming), and is the co-editor of Christians and the Color Line: Race and Religion after Divided by Faith (Oxford University Press, 2013). He has also begun researching a new project on the white flight of churches from urban America in the second half of the twentieth century.

* * *

There are two historical narratives about white evangelicals’ role in the civil rights movement; neither is cause for praise.

1. Evangelical Apathetic Non-Involvement with the Civil Rights Movement

I can tell the first narrative succinctly using a set of documents I came across a few years ago while doing research in the archival papers of the National Association of Evangelicals (NAE). Among boxes of financial statements and press clippings, I came upon a cache of letters that the NAE received in 1964 and 1965 from anxious white evangelicals across the country. These evangelicals were concerned that the NAE was offering support to the civil rights movement, thereby becoming indistinguishable from the (more liberal) National Council of Churches or the (more Catholic) National Catholic Welfare Agency. Those anxious evangelicals needn’t have worried. Contrary to false reports about the NAE throwing its weight behind the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the association had instead come to the conclusion that civil rights “is not the business of the church; so the NAE has strictly stayed out of this area.” The following March, when Martin Luther King Jr. called for ministers from around the country to descend on Selma, Alabama, to support black voting rights, the NAE again demurred, this time stating that the association “has a policy of not becoming involved in political or sociological affairs that do not affect the function of the church or those involved in the propagation of the gospel.”

In the narrative above, white evangelicals were simply a nonfactor in civil rights: although they would not support the meaning or the methods of the civil rights movement, they nonetheless would not actively oppose the movement’s ultimate goals. For many white evangelicals today, this history represents something of a best-case scenario. After all, it is no secret that the overwhelming majority of white evangelicals missed the boat when it came to the black freedom struggle of the 1950s and 1960s. Casting evangelical apathy toward civil rights as the result of naïve or misguided notions about the political nature of the movement, therefore, at least offers an explanation of how white evangelicals could have failed so miserably during the national drama of the civil rights years. This history also offers a shorter road to redemption. If evangelicals’ previous social justice shortcomings were merely the result of failing to see the overlap of the sacred and the secular, the only corrective needed going forward is a broader understanding of which issues the church must engage today.

2. Evangelical Active Opposition to the Civil Rights Movement: Hermeneutics of Segregation

But, there is a lesser known—or lesser discussed, anyway—history of evangelicals’ encounter with civil rights in the American South that must be told given the outsized influence southern evangelicalism has had on the broader American evangelical movement. Unfortunately, it is a much darker story with a more damning legacy. To state it plainly, the majority of southern white evangelicals actively opposed the civil rights movement in its various manifestations in the middle decades of the twentieth century because they saw it as a violation of God’s design for racial segregation.

In researching evangelicals in South Carolina I discovered that these conservative white Christians utilized a biblical hermeneutic of segregation to oppose everything related to racial integration from the 1954 Brown decision to the bussing of public school children in the early 1970s. In their reading of Scripture, God was the author of segregation and therefore demanded evangelical resistance to integration at every turn.

In the public sphere this opposition meant that many evangelicals assisted in organizing Citizens Councils to thwart civil rights initiatives while petitioning their political leaders to stand firm in their segregationist convictions with the assurance that “we in the South will not mix because it is not God’s plan.”

Intramural opposition to racial integration in evangelical circles was even more vociferous. Throughout South Carolina, ministers who suggested integrating their churches were dismissed from their pulpits and when the state’s Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian colleges finally desegregated in the mid-1960s, white evangelicals withheld both their financial support and their children from the institutions. As late as 1969 South Carolina leaders still received letters from constituents reminding them that it was “against [our] religion to mix. It’s in the Bible that you’re not supposed to mix races.” In their public advocacy of God’s desire for segregation, their maintenance of segregated churches, and their fleeing of desegregated public schools, southern evangelicals from the 1950s through the early 1970s demonstrated that the hermeneutic of segregation exerted a powerful force over their thought and actions.

As a growing number of latter-day southern white evangelicals begin pursuing racial justice, recognition that a substantial percentage of their forebears opposed the civil rights movement on religious grounds becomes ever more imperative. A hermeneutic of segregation helped produce today’s society. Achieving racial justice, then, will require evangelicals to grapple with this historical truth and counteract its historical residue. If a hermeneutic of segregation justified white flight, its historical residue makes it possible to view evidence of deeply entrenched residential segregation with an untroubled conscience. If a hermeneutic of segregation justified a retreat to segregated private schools, its historical residue has allowed the resegregation of public schools to proceed unabated. And if a hermeneutic of segregation justified maintaining segregated sanctuaries, its historical residue is profoundly felt in surveys reporting that, while 11:00 Sunday morning continues to be the most segregated hour of the week, most white Christians are just fine with that.

Notes

Clyde W. Taylor to W.R. Kliewer, March 23, 1965, National Association of Evangelical Papers, Box 52, Folder “Civil Rights 1965.”

“Memo for Dr. Taylor,” March 12, 1965, National Association of Evangelicals Papers, Box 52, Folder “Civil Rights 1965.”

Fred Hulon to Strom Thurmond, February 12, 1958, Strom Thurmond Papers, Subject Correspondence Series 1958, Box 24, Folder “Segregation I.”

Betty Watson to Strom Thurmond, October 4, 1969, Strom Thurmond Papers, Subject Correspondence Series 1969, Box 4, Folder “Civil Rights VII.”

February 7, 2015

Do You Literally Interpret the Bible Literally?

It is a futile desire, to be sure. But there are times I wish we could have a moratorium on the word “literally.”

I am not referring to the use of literally as an intensifier or a stand-in for the word actually or really, which Vice President Biden uses liberally. (For what it’s worth, Mark Twain, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and James Joyce were all known to use this form of “literally.”)

Instead, I am thinking of the use of the term when someone doubts the historicity of the Bible and asks if you “take the Bible literally.”

I am also thinking about intramural Christian debates about interpretation—whether we are talking about Bible translation or the days of creation or the fulfillment of prophecy—where one side will insist that they interpret the passage “literally.”

I am not a fan of linguistic legalism and I recognize the need for terminological shortcuts, but I am an advocate for clarity, and the use of an ambiguous term like literal can create confusion. It’s a single term with multiple meanings and connotations—which is true of many words—but the problem is that many assume it means only one thing.

So my proposal is that if we have a moratorium on this word, we have a chance of speaking and hearing with greater understanding.

Since I have no real authority to call for an actual moratorium and it has little chance to succeed, my alternative proposal is that when someone asks you if you take the Bible “literally” or a passage “literally,” you ask what they mean by the word and then proceed to answer in accordance with the definition they provide.

In order to show that the word literal and its usage has multiple meanings, shades of nuance, and varying connotations, consider this analysis from Vern Poythress. In it, he identifies at least five different uses of the term.

1. First-Thought Meaning (Determining the Meaning of the Words in Isolation)

First, one could say that the literal meaning of a word is the meaning that native speakers are most likely to think of when they are asked about the word in isolation (that is, apart from any context in a particular sentence or discourse).

This I have . . . called “first-thought” meaning. Thus the first-thought meaning of “battle” is “a fight, a combat.” The first-thought meaning is often the most common meaning; it is sometimes, but not always, more “physical” or “concrete” in character than other possible dictionary meanings, some of which might be labeled “figurative.” For example the first-thought meaning of “burn” is “to consume in fire.” It is more “physical” and “concrete” than the metaphorical use of “burn” for burning anger. The first-thought meaning, or literal meaning in this sense, is opposite to any and all figurative meanings.

We have said that the first-thought meaning is the meaning for words in isolation. But what if the words form a sentence? We can imagine proceeding to interpret a whole sentence or a whole paragraph by mechanically assigning to each word its first-thought meaning. This would often be artificial or even absurd. It would be an interpretation that did not take into account the influence of context on the determination of which sense or senses of a word are actually activated. We might call such an interpretation “first-thought interpretation.”

2. Flat Interpretation (Taking It Literally If at All Possible)

Next, we could imagine reading passages as organic wholes, but reading them in the most prosaic way possible. We would allow ourselves to recognize obvious figures of speech, but nothing beyond the most obvious. We would ignore the possibility of poetic overtones, irony, wordplay, or the possibly figurative or allusive character of whole sections of material. At least we would ignore such things whenever they were not perfectly obvious. Let us call this “flat interpretation.” It is literal if possible.’

3. Grammatical-Historical Interpretation (Discerning the Meaning of the Original Author)

In this type one reads passages as organic wholes and tries to understand what each passage expresses against the background of the original human author and the original situation. One asks what understanding and inferences would be justified or warranted at the time the passage was written. This interpretation aims to express the meanings that human authors express. Also it is willing to recognize fine-grained allusions and open-ended language. It endeavors to recognize when authors leave a degree of ambiguity and vagueness about how far their allusions extend. Let us call this “grammatical-historical interpretation.”

If the author is a very unimaginative or prosaic sort of person, or if the passage is part of a genre of writing that is thoroughly prosaic, the grammatical-historical interpretation of the passage coincides with the flat interpretation. But in other cases flat interpretation and grammatical-historical interpretation will not always coincide. If the author is trying to be more imaginative, then it is an allowable part of grammatical-historical interpretation for us to search for allusions, wordplays, and other indirect ways of communicating, even when such things are not so obvious that no one misses them.

4. Plain Interpretation (Reading It As If It Was Written Directly to Us)

“Plain interpretation,” let us say, is interpretation of a text by interpreters against the context of the interpreters’ tacit knowledge of their own worldview and historical situation. It minimizes the role of the original historical and cultural context.

Grammatical-historical interpretation differs from plain interpretation precisely over the question of the primary historical and cultural context for interpretation.

Plain interpretation reads everything as if it were written directly to oneself, in one’s own time and culture.

Grammatical-historical interpretation reads everything as if it were written in the time and culture of the original author.

Of course when we happen to be interpreting modern literature written in our own culture or subculture, the two are the same.

5. Literal in the Technical Sense (The Opposite of Figurative)

Of course the word “literal” could still be used to describe individual words that are being used in a nonfigurative sense.

For instance the word “vineyard” literally means a field growing grapes. In Isaiah 27:2 it is used nonliterally, figuratively, as a designation for Israel. By contrast, in Genesis 9:20 the word is used literally (nonfiguratively). In these instances the word “literal” is the opposite of “figurative.” But since any extended passage might or might not contain figures of speech, the word “literal” would no longer be used to describe a global method or approach to interpretation.

You can read the whole article here.

The bottom line: literal is an ambiguous word, and in many contexts I think it should either be avoided or defined in order to facilitate clarity in communicating meaning.

February 6, 2015

Jim Crow, Civil Rights, and Southern White Evangelicals: A Historians Forum (Sean Michael Lucas)

The movie Selma reminds us that white clergy protested and marched with Martin Luther King Jr. and other African Americans in the 1960s on behalf of Civil Rights. But it also reminds us—as Anthony Bradley recently observed—that many of those clergy were from the North and were Protestant mainliners, Greek Orthodox, Jewish, and Roman Catholic. One has to wonder: where were the conservative evangelicals?

I recently posed the following questions to several historians who have studied segregation and religion in the Southern United States during the years of Jim Crow and during the Civil Rights Movement.

Did white evangelicals in the South respond to the Civil Rights Movement in different ways from their counterparts in other parts of the United States? Is it fair to say that the majority not only refused to engage but actively opposed it? If so, what historical forces formed their particular responses and attitudes? How did evangelical theologies form or undermine their engagement?

I will be posting the historians’ answers at this blog throughout the week.

The first respondent was Matt Hall of Southern Seminary.

Today I’m pleased to welcome to this forum Sean Michael Lucas (PhD, Westminster Theological Seminary), who is an associate professor of church history at Reformed Theological Seminary in Jackson, MS, and the senior minister of the historic First Presbyterian Church, Hattiesburg, MS. He is the author of Robert Lewis Dabney: A Southern Presbyterian Life and the forthcoming For a Continuing Church: The Roots of the Presbyterian Church in America.

Today I’m pleased to welcome to this forum Sean Michael Lucas (PhD, Westminster Theological Seminary), who is an associate professor of church history at Reformed Theological Seminary in Jackson, MS, and the senior minister of the historic First Presbyterian Church, Hattiesburg, MS. He is the author of Robert Lewis Dabney: A Southern Presbyterian Life and the forthcoming For a Continuing Church: The Roots of the Presbyterian Church in America.

* * *

While it is the case that conservatives in the old Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS, often called “the Southern Presbyterian Church”), taken as a group, opposed the Civil Rights movement, the story is a little bit more complex than that in two ways.

First, there were different positions on how to think about racial integration; and, second, there was also change over time for the movement as a whole.

1. Positions

That there would be differing positions on the most explosive issue to face the American South is not surprising. What perhaps is surprising is that these differing positions are reflected in a generally conservative religious and political subset.

Segregationists

W. A. Gamble, stated clerk of Central Mississippi Presbytery, represented hardline racial intransigence. Featured in Citizen’s Council events in the Jackson area, Gamble frequently defended Jim Crow laws, warning that “it cannot be forgotten that the removal of segregation laws, and the consequent mingling of the races more and more, will inevitably result in miscegenation.” He also held that those who opposed “segregation by law” would be complicit “in developing a mongrel population, a development I believe God disapproves.” Racial traditionalists like Gamble tried to frame their defense of segregation in theological terms, appealing especially to Acts 17:26; however, their most powerful arguments were emotional, playing on white fears of mixed race marriages.

Moderates

While Gamble’s position was likely held by a wide number of southern Presbyterian conservatives, there were other positions. L. Nelson Bell, the long-time associate editor of the Presbyterian Journal and founder of Christianity Today, held what was viewed to be a moderate position. On the one hand, “forced segregation is un-Christian because it denies the rights which are inherent in American citizenship.” In addition, as Bell’s son-in-law Billy Graham demonstrated, the Gospel needed to be preached “to all on an unsegregated basis.” To demand continued legal segregation would undercut the preaching of the Gospel in America and abroad. On the other hand, though, forced integration opened the door to the possibility of race mixing that was unthinkable. Better to do away with the legal barriers for blacks’ participation in American society, but then let Christian love and prudence take its natural course.

While Gamble’s position was likely held by a wide number of southern Presbyterian conservatives, there were other positions. L. Nelson Bell, the long-time associate editor of the Presbyterian Journal and founder of Christianity Today, held what was viewed to be a moderate position. On the one hand, “forced segregation is un-Christian because it denies the rights which are inherent in American citizenship.” In addition, as Bell’s son-in-law Billy Graham demonstrated, the Gospel needed to be preached “to all on an unsegregated basis.” To demand continued legal segregation would undercut the preaching of the Gospel in America and abroad. On the other hand, though, forced integration opened the door to the possibility of race mixing that was unthinkable. Better to do away with the legal barriers for blacks’ participation in American society, but then let Christian love and prudence take its natural course.

Integrationists

There were still others, and especially among the younger generation who would take PCUS pulpits in the 1960s, who believed that segregation in society and church was repugnant to the Gospel and that the church should work toward modeling an integrated community. Bill Hill, who pastored West End Presbyterian Church and First Presbyterian Church in Hopewell, Virginia, simultaneously, worked toward racially inclusive meetings, especially in his evangelistic work during the 1940s and 1950s. In many ways ahead of his time, Hill modeled the same race-blind evangelistic imperative as Billy Graham.

There were still others, and especially among the younger generation who would take PCUS pulpits in the 1960s, who believed that segregation in society and church was repugnant to the Gospel and that the church should work toward modeling an integrated community. Bill Hill, who pastored West End Presbyterian Church and First Presbyterian Church in Hopewell, Virginia, simultaneously, worked toward racially inclusive meetings, especially in his evangelistic work during the 1940s and 1950s. In many ways ahead of his time, Hill modeled the same race-blind evangelistic imperative as Billy Graham.

Likewise, Donald Patterson, James Baird, and Kennedy Smartt—all members of the steering community that would birth the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) in 1973—all worked toward racial inclusion in their respective ministries. These PCA founders, along with Frank Barker and D. James Kennedy, made it plain that the continuing Presbyterian church would not be a “white man’s church” nor stand for racial solidarity. Like Hill and Graham, these founders believed that the Gospel should produce a racially inclusive church.

2. Changes

This last group represents the second point: that there was change over time on the racial issue for these southern Presbyterian conservatives. While there were very few southern Presbyterian conservative voices in the 1940s urging racial inclusion, by the late 1960s, it was unthinkable to most young conservative leaders that the church would remain racially separated. The question to ask is why: why were the larger theological and cultural arguments for continued racial segregation unpersuasive to the younger leaders who would form the PCA?

Billy Graham

I think the answer comes back to Billy Graham. For southern Presbyterians, Graham represented what they most wanted for their church: a thorough commitment to the Bible as the inerrant Word of God, a gentle and winsome evangelical theology, and a determined zeal for evangelism and missions. When Graham determined in 1952-53 that he could no longer preach the Gospel to segregated meetings because that would represent a betrayal of the Gospel itself, younger southern Presbyterian conservatives nodded their heads in agreement. They too would work toward preaching the Gospel to all men and women regardless of race because the Good News was for all.

I think the answer comes back to Billy Graham. For southern Presbyterians, Graham represented what they most wanted for their church: a thorough commitment to the Bible as the inerrant Word of God, a gentle and winsome evangelical theology, and a determined zeal for evangelism and missions. When Graham determined in 1952-53 that he could no longer preach the Gospel to segregated meetings because that would represent a betrayal of the Gospel itself, younger southern Presbyterian conservatives nodded their heads in agreement. They too would work toward preaching the Gospel to all men and women regardless of race because the Good News was for all.

But Graham also modeled their thoughts on cultural engagement. Committed to the “spiritual mission of the church,” even these younger southern Presbyterians believed that the way to effect cultural change was through preaching the Gospel. Graham’s crusades brought such social effects, not because he preached a “Social Gospel,” but because he preached the true Gospel—and changed men and women brought about a changed society. By preaching the Gospel to racially inclusive groups like Billy Graham did, southern Presbyterian conservatives hoped that the Gospel itself would produce the “beloved community” that they too wanted for their country. They longed to see an America that reflected the Gospel itself.

Of course, that does not mean that the founders of the PCA or their sons and now grandsons have seen that sort of transformation. Far from it—our own theological beliefs have still been trumped far too often by other deeper-seated commitments to race, class, or region. However, from a historical perspective, this explains why I believe that the PCA—the continuing, conservative mainline successor to the PCUS—must continue to work toward racial reconciliation and inclusion that the Gospel itself demands.

February 5, 2015

Jim Crow, Civil Rights, and Southern White Evangelicals: A Historians Forum (Matthew J. Hall)

The movie Selma reminds us that white clergy protested and marched with Martin Luther King Jr. and other African Americans in the 1960s on behalf of Civil Rights. But it also reminds us—as Anthony Bradley recently observed—that many of those clergy were from the North and were Protestant mainliners, Greek Orthodox, Jewish, and Roman Catholic. One has to wonder: where where the conservative evangelicals?

I recently posed the following questions to several historians who have studied segregation and religion in the Southern United States during the years of Jim Crow and during the Civil Rights Movement.

Did white evangelicals in the South respond to the Civil Rights Movement in different ways from their counterparts in other parts of the United States? Is it fair to say that the majority not only refused to engage but actively opposed it? If so, what historical forces formed their particular responses and attitudes? How did evangelical theologies form or undermine their engagement?

I will be posting the historians’ answers at this blog throughout the week.

The first respondent is Matthew J. Hall (Ph.D., University of Kentucky), who serves as vice president of academic services at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, where he also teaches courses in church history and American history. He is co-editor of the forthcoming Essential Evangelicalism: The Enduring Legacy of Carl F. H. Henry (Crossway). His dissertation was on “Cold Warriors in the Sunbelt: Southern Baptists and the Cold War, 1947-1989.” You can follow him on Twitter at @MatthewJHall.

The first respondent is Matthew J. Hall (Ph.D., University of Kentucky), who serves as vice president of academic services at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, where he also teaches courses in church history and American history. He is co-editor of the forthcoming Essential Evangelicalism: The Enduring Legacy of Carl F. H. Henry (Crossway). His dissertation was on “Cold Warriors in the Sunbelt: Southern Baptists and the Cold War, 1947-1989.” You can follow him on Twitter at @MatthewJHall.

* * *

As a historian who is also a Southern Baptist, I am in something of a perpetual quandary. In all of my research on the long history of racial justice and the black freedom movement, I find that my fellow churchmen who supported the cause of justice were more often the exception, not the rule. Instead, my research—and that of historians far more accomplished than me—makes quite clear that white evangelicals throughout the South were overwhelmingly opposed to the civil rights movement. They may have couched their opposition in more genteel ways than the Klan—yes, the White Citizens Councils would do the job—but oppose it they did nonetheless.

A couple caveats here. First, it’s worth noting that the evangelical canopy has always been a broad and unwieldy one. Broad enough to include Anabaptists and Campbellites, Wesleyans and Presbyterians, Pentecostals and Lutherans—we should be leery of speaking of it in monolithic terms. But it does seem that in its most traditional forms, regardless of geography, evangelicals were often those not only skeptically removed from the civil rights movement, but directly opposed to it. There were notable exceptions, of course. And, as noted by historians such as David Swartz and Brantley Gasaway, there has always been a stream within the broader evangelical river that has prioritized social action and justice.

But it does seem self-evident that, in the main, white evangelicals—particularly those in the South—were deeply invested in efforts to either uphold Jim Crow or to try to slow down its dismantling. While a previous generation of historians suggested this was symptomatic of “cultural captivity,” I’m not so sure. In fact, in many cases, it seems that evangelical theology—or at least distorted models of it—were part of the reason segregationist beliefs and structures took shape the way they did. The unfortunate reality isn’t that evangelical theology in the South was muted when it came to racial justice, it’s that it was actively used to undermine justice and to perpetuate a demonic system. And that’s the cruelest historical irony of it all: those who loved the “old rugged cross” were often also those who torched crosses in protest of desegregation.

Why was this? Why did this particular subgrouping of evangelicals seem especially vulnerable to this cultural and theological blindness? It was a malady not unique to southern white evangelicals, but it did afflict them in particularly pronounced ways. Let me try to give some historical reasons.

1. Many white southern evangelicals had a deficient doctrine of sin.

Let me be clear. These evangelicals had a very clear understanding of the personal realities of behavior contrary to revealed biblical norms, or at least a somewhat selective list of them. But where they fell short was in articulating a fully-orbed doctrine of sin, one that has deep roots in the Christian tradition and is far more pessimistic about the extent and effects of sin. A classic Protestant understanding of sin might have helped them recognize the ways in which sin infects not only personal individual choices, but also social structures, economic systems, legal codes, etc. But by relegating sin only to the realm of individual choice, it allowed white evangelicals to denounce anything broader as political entanglement that had no connection to Christian ethics or witness.

2. White evangelicals often capitulated to the racist hysteria surrounding fears of intermarriage.

Those who denounced the civil rights movement routinely trotted out the allegation that the cause was fundamentally about “mixing the races” and marrying off blacks and whites. For many southern whites, the thought of their white daughter married and sexually united to a black man was unfathomable. A long and horrendous tradition had developed citing clumsily applied biblical passages that were purported to demonstrate God’s prohibition of such marriages. Evangelicals should have known better and been immune to such poor biblical interpretation. But when opponents of the civil rights movement tried to delegitimize the movement by “warning” of the secret motives of its leaders, far too many evangelicals were susceptible to their tactics.

3. White southern evangelicals were blinded by their majority status to the injustice around them.

Other historians have noted that blacks and whites often inhabited two different worlds. Southern whites often thought they knew the world of subordinate blacks, assuming all was well in the racial hierarchy. Jim Crow allowed for southern whites—including the large number of them who claimed membership in churches—to sincerely believe that everyone within the system was content. Only a few “troublemakers” ever seemed to voice dissent, and those that did often could end up on the other end of a rope, hanging from a lynching tree due to allegations of some impropriety or questionable criminal allegation. In part, this helps explain why so many southern whites excoriated the civil rights movement as merely the fabrication of a group of “outside agitators” sent in to stir up strife among the otherwise docile and happy black population. While they were eventually disabused of that notion, it seemed to them to be the only rational explanation for the powder keg that seemed to have exploded out of nowhere.

4. White southern evangelicals imbibed and perpetuated the Lost Cause mythology.

Developing at the end of Reconstruction and the closing of the nineteenth century, white southerners constructed memories of the Old South and the Civil War that perpetuated assumptions about white superiority, the necessity of racial segregation, and the seemingly victimized status of the region. It found expression among trained historians, but at the more popular level—one deeply infused with religious meaning—it became even more influential as a form of civil religion. For many southern whites, including evangelicals, it provided a worldview that told them that slavery was an unfortunate institution that would have naturally run its course, that the South was marked by a different chivalrous—and more Christian—moral code than the rest of the nation, that the “War of Northern Aggression” was an unconstitutional incursion into southern states’ rights, and that the South still represented the only great hope for long term American stability and prosperity. Well in place by the 1950s, the Lost Cause mythology inoculated massive numbers of white southerners—including Jesus-loving, gospel-preaching, soul-winning churchgoers—to be leery of anything that suggested that the status quo was characterized by injustice and unrighteousness.

Evangelicals are right to prioritize the work of racial reconciliation and its rooting in the gospel of Jesus Christ. But reconciliation by its very nature requires some sometimes unpleasant conversations and mutual understanding to answer the question, “How did we get here?” I’m hopeful for the future of evangelical racial reconciliation in part because I see a new generation willing to look to the past with honesty and to listen, even when it’s uncomfortable and unpleasant. Even more, I am confident that the gospel that reconciles sinners to God and to one another is as powerful as ever.

February 3, 2015

The Sequel for “To Kill a Mockingbird”—Written in the 1950s—Will Be Published in July 2015

Harper Lee (b. 1926) wrote her first novel, Go Set a Watchman (304 pp.), in the mid-1950s while she was in her thirties. The setting was roughly contemporary to Lee’s own time, featuring Maycomb County (an imaginary district in southern Alabama) during the 1950s. One of the main characters was an adult woman named Scout (Jean Louise) Finch, and the novel included flashback’s to her childhood.

Harper Lee (b. 1926) wrote her first novel, Go Set a Watchman (304 pp.), in the mid-1950s while she was in her thirties. The setting was roughly contemporary to Lee’s own time, featuring Maycomb County (an imaginary district in southern Alabama) during the 1950s. One of the main characters was an adult woman named Scout (Jean Louise) Finch, and the novel included flashback’s to her childhood.

Harper Lee’s editor was captured by these flashbacks and persuaded her to write a new novel with young Scout as the narrator, set in the same Alabama town 20 years earlier in the early 1930s. Lee recounts, “I thought [Go Set a Watchman] a pretty decent effort.” After being asked to set the book aside in order to write the prequel, she notes, ”I was a first-time writer, so I did as I was told.

That second novel became the famed To Kill a Mockingbird, which was published on July 11, 1960. It went on to sell 40 million copies worldwide, won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1961, and was enshrined in the American canon of literature.

In the fall of 2014, attorney Tonja Carter—family friend and successor in her sister’s law firm—discovered the manuscript in a secure location, affixed to an original typescript of To Kill a Mockingbird. Harper Lee was unaware that the book had survived, and was surprised and delighted to hear about its existence. She writes, “After much thought and hesitation, I shared it with a handful of people I trust and was pleased to hear that they considered it worthy of publication. I am humbled and amazed that this will now be published after all these years.”

In the next book, “Scout (Jean Louise Finch) has returned to Maycomb from New York to visit her father, Atticus. She is forced to grapple with issues both personal and political as she tries to understand her father’s attitude toward society, and her own feelings about the place where she was born and spent her childhood.”

The book will be released on July 14, 2015, with an initial printing of 2 million copies. You can pre-order it from Amazon here.

The title of the book is apparently an allusion to Isaiah 21:6, “For thus the Lord said to me: ‘Go, set a watchman; let him announce what he sees'” (ESV).

February 2, 2015

6 Principles for Effective, Redemptive Communication

One thing that strikes me about some pockets of conservative Christian writing on the internet is how little attention is given toward the art of persuasion. It’s one thing to be right; it’s another thing to present true doctrine in a compelling way that adorns our doctrine (Titus 2:10). We are sometimes satisfied merely to proclaim instead of following the apostle Paul who sought to “persuade Jews and Greeks” and who said that the “knowing the fear of the Lord, we persuade others” (2 Cor. 5:11).

Several years ago, David Powlison was invited to answer some questions for a secular journal, Psychology Today, seeking to introduce a wide range of religious therapies. (Also answering the questions were advocates for counseling from within the worldviews of Judaism, Native American Spirituality, Catholicism, Islam, Hinduism, Mormonism, African Spirituality, Secular Humanism, Twelve Step Spirituality, Christian Psychology, and Buddhism).

In seeking to provide compelling answers to genuine questions from those outside the faith, Powlison studied the biblical model for effective, redemptive persuasion. He notes that “Jesus’ interaction with the Samaritan woman in John 4 and Paul’s speech at the Areopagus in Acts 17 provide rich examples of what these communication tasks look like in action.” [For a whole book analyzing one of these interactions, see Paul Copan and Kenneth Litwak’s The Gospel in the Marketplace of Ideas: Paul’s Mars Hill Experience for Our Pluralistic World (IVP Academic, 2014).

Below is an outline of what he saw in Scripture. I find these to be helpful reminders for evangelism and for all of our discourse as we seek to win the world to Christ.

1. Know those with whom we wish to speak.

What do my readers believe, do, assume? What are their intellectual and professional habits? What is their reality map? What are their goals and expectations? . . .

2. Genuinely seek the welfare of those you are speaking to.

I must care. I must love. I must treat with respect. . . . It has been life and joy for me to come to Christian understandings—I want my readers to share the same, to know the goodness and wisdom of the same Savior who mercifully found me.

3. Enter the hearers’ frame of reference.

I’ve been asked to enter a conversation that they initiated. To do so, I must be willing to speak a foreign language, as it were, to talk in their terms, to answer the questions they are asking. I am willing to speak the language that expresses the experience of people who are outsiders to Christian faith . . . And I am willing to get personal, disclosing who I am as a person. In each answer, in attempting to explain what I believe and do, I start in their world and seek to stay connected to that world—even as I explain the world that I think all of us actually inhabit. I take their questions seriously. I hope that every answer stays on point and answers the question asked—rather than ignoring their questions in order to assert my own predetermined talking points.

4. Shake readers’ habitual frame of reference.

I want to take what is familiar and portray it in a different light. The very things that readers know best actually mean something quite different from what they assume. So, though I take their questions seriously, I reshape the meaning of those questions. I redefine terms. I overturn implicit assumptions. I seek to retell their version of reality to demonstrate how they miss very important things. Not only do they have significant blind spots, but they misconstrue things they take as givens. The things they see most clearly and care about most deeply don’t actually mean what they imagine. I want to arouse dissonance, to rattle the cage, to create a dilemma. So even while speaking in their terms, I am retelling their story in a way that brings fatal flaws, inner contradictions, illusions, and blind spots to light.

5. Portray Christian faith in a fresh, relevant way.

I want them to understand “religion” in ways they’ve never heard or understood before. . . . I assume that they do not know how true Christianity pointedly illumines their questions, explains the people and problems they deal with, and reframes everything they do in trying to be helpful. I want to show and tell better ways of making sense of people. I want to show and tell better and more significant solutions. I want to show and tell better, truer, and more enduring hope. I want to surprise readers with how the gospel of Jesus Christ intercepts who they are and intervenes in what they do.

6. Woo, invite, and open a door for readers and hearers to change their minds.

So I include the reader in almost every paragraph—“This is for you. This is about all of us.” I want a reader to know, “You live in the same world I do. . . .” We live in God’s world—wittingly or unwittingly, willingly or unwillingly. Awaken. Understand yourself within this new, better reality that I am portraying. Understand who you are and what you do in a bright new light. Come to the Lamb of God. . . .

Powlison writes:

A redemptive communication strategy not only engages people winsomely, but also serves a larger purpose. It opens the door to the three stages of a living, lifechanging faith: knowledge, assent, and trust (notitia, assensus, fiducia).

Real faith starts with coming to know something.

Then I must come to agree that it is true.

Finally I must shift the weight of my life onto that truth.This correlates to three aspects of pastoral communication:

informing,

convincing, and

persuading.Writers and speakers make a judgment call about the necessary balance between these activities in any piece of communication.

You can read the whole thing here and also see how he actually answers the questions Psychology Today posed to him: David Powlison, “Giving Reasoned Answers to Reasonable Questions,” JBC 28:3 (2014): 2-14.

CROSS: A One-Night Missions Conference Online for Free: Friday, February 27, 2015

Here is a wonderful opportunity for individuals, families, small groups, co-workers, youth groups, college groups and dorms to gather together for four hours to hear from gifted teachers on the need and means of taking the gospel to the nations.

You can watch the Cross conference live, for free, here.

Just register to watch. And if you’re hosting a viewing of the simulcast and want to invite others to, sign up here. (That link will also let you see other viewing locations in your area.)

Here are the speakers, their message titles, and the times (all times Eastern).

Friday, February 27, 2015

7 pm — Main Session 1

John Piper, “Undaunted by the Darkness: Invincible Joy for the Sake of the Nations”

Panel, “Who On Earth Are We Talking About? Naming the Unreached and Unengaged and Why”

9:30 pm — Main Session 2

Note: The following three talks will only be 15 minutes each.

Kevin DeYoung, “Putting the Spread of the Gospel at Risk One Click at a Time”

Mack Stiles, “Clever Missionaries Need Not Apply”

Thabiti Anyabwile, “Don’t Mortgage the Mission”

10:15 pm — Main Session 3

David Platt, “Undaunted by Resistance: Sustaining Missionary Zeal for the Sake of the Nations”

January 30, 2015

You Don’t Need to Be Able to Define a Word Before You Know What It Means

Winfried Corduan:

The possible objection that I cannot know what a term means unless I can provide an exhaustive definition for it rests on a thorough misunderstanding of the nature of language. We do not know what words mean because we know their definitions. Such a requirement would mean that all nonreflective language users (e.g. children) do not know the meaning of their talk—an absurd proposal. Surely definitions are quite helpful, e.g. when looking up the meaning of unknown words in dictionaries. But dictionaries also only report meaning; they do not legislate it.

—Winfried Corduan, Mysticism: An Evangelical Option? (1991; reprint, Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2009), 22 n. 2.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers