Justin Taylor's Blog, page 83

February 24, 2015

FAQ on Baptism in the Early Church

Some conclusions from Everett Ferguson’s 975-page tome, Baptism in the Early Church: History, Theology, and Liturgy in the First Five Centuries (Eerdmans, 2009):

Some conclusions from Everett Ferguson’s 975-page tome, Baptism in the Early Church: History, Theology, and Liturgy in the First Five Centuries (Eerdmans, 2009):

Is there evidence for infant baptism exist before the second part of the second century?

“There is general agreement that there is no firm evidence for infant baptism before the latter part of the second century.” (p. 856)

Does this mean that infant baptism didn’t exist?

“This fact does not mean that it did not occur, but it does mean that supporters of the practice have a considerable chronological gap to account for. Many replace the historical silence by appeal to theological or sociological considerations.” (p. 856)

Why did infant baptism emerge?

“The most plausible explanation for the origin of infant baptism is found in the emergency baptism of sick children expected to die soon so that they would be assured of entrance into the kingdom of heaven.” (p. 856)

When did it catch on and become the dominant understanding of baptism?

“There was a slow extension of baptizing babies as a precautionary measure. It was generally accepted, but questions continued to be raised about its propriety into the fifth century. It became the usual practice in the fifth and sixth centuries.” (p. 857)

What was the mode of baptism in the early church?

“The comprehensive survey of the evidence compiled in this study give a basis for a fresh look at this subject and seeks to give coherence to that evidence while addressing seeming anomalies. The Christian literary sources, backed by secular word usage and Jewish religous immersions, given an overwhelming support for full immersion as the normal action. Exceptions in cases of a lack of water and especially of sickbed baptism were made. Submersion was undoubtedly the case for the fourth and fifth centuries in the Greek East and only slightly less certain for the Latin West.” (p. 857)

Was this a change from an earlier practice, a selection out of options previously available, or a continuation of the practice of the first three centuries?

“It is the contention of this study that the last interpretation best accords with the available facts. Unless one has preconceived ideas about how an immersion would be performed, the literary, art, and archaeological evidence supports this conclusion.” (p. 857)

The Complementarian Publishing Conundrum

New Testament scholar Tom Schreiner, on the challenges of writing on complementarianism and the attractiveness of new egalitarian interpretations of Scripture:

Sometimes I wonder if egalitarians hope to triumph in the debate on the role of women by publishing book after book on the subject. Each work propounds a new thesis which explains why the traditional interpretation is flawed.

Complementarians could easily give in from sheer exhaustion, thinking that so many books written by such a diversity of different authors could scarcely be wrong.

Further, it is difficult to keep writing books promoting the complementarian view. Our view of the biblical text has not changed dramatically in the last twenty five years. Should we continue to write books that essentially promote traditional interpretations? Is the goal of publishing to write what is true or what is new?

One of the dangers of evangelical publishing is the desire to say something novel. Our evangelical publishing houses could end up like those in Athens so long ago: “Now all the Athenians and the strangers visiting there used to spend their time in nothing other than telling or hearing something new” (Acts 17:21, NASB).

Revisionism and reinterpretation require that we return to the text to see if these things are so. In February of 2016, Crossway will publish the third edition of Women in the Church: An Interpretation and Application of 1 Timothy 2:9-15, edited by Andreas J. Köstenberger and Thomas R. Schreiner. It contains a number of essays on this classic passage, including extensive new research on parallels to the syntax of 1 Timothy 2:12 from the first century.

A Crash Course on Influencers of Unbelief: Machiavelli

This is a series on some influential modern thinkers who influenced the world of unbelief. (For previous entries, see Freud and Marx.)

These are notes based on an essay by Peter Kreeft and a course notebook; Kreeft is the author of Socrates Meets Machiavelli: The Father of Philosophy Cross-Examines the Author of The Prince (St. Augustine’s Press, 2012).

Who was Niccolò Machiavelli?

He was a Florentine political theorist who founded modern political and social philosophy.

How do you pronounce his last name?

mock-ee-ah-VELL-ee

When did he live?

1496-1527. (For historical reference, Machiavelli was born 13 years after Luther and 13 before Calvin.)

What was Machiavelli’s significance?

Seldom in the history of thought has there been a more total revolution.

Did Machiavelli recognize how radical he was?

He compared his work to Columbus’ as the discoverer of a new world, and to Moses’ as the leader of a new chosen people who would exit the slavery of moral ideas into a new promised land of power and practicality.

What is his most famous work?

The Prince. (The print version was published posthumously in 1532.)

What are the three key assumptions of The Prince?

Everything that Machiavelli says in this book follows from three assumptions:

Metaphysical assumption: Reality consists only of material facts (not objectively real ideals, goods, or values).

Anthropological assumption: Man, by nature, is wicked, selfish, competitive, and immoral. (Matter is essentially competitive and so is men; therefore, “morality” contradicts reality.)

Epistemological assumption: Reality is revealed only by sense observation. (Human history is an empirical science.)

For all social thinkers prior to Machiavelli, what was the goal of political life?

Virtue. Politics was the art of the good. The conception of a good society was one in which people are good.

For Machiavelli, what was politics?

The art of the possible.

How much did this point influence subsequent social and political philosophers?

Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, Mill, Kant, Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, Dewey all subsequently rejected the goal of virtue.

What was Machiavelli’s argument?

Traditional morals are like the stars (beautiful but too distant to cast any useful light on our earthly path). We need instead man-made lanterns (i.e., attainable goals).

In other words, we must take our bearings from the earth, not from the heavens; from what men and societies actually do, not from what they ought to do.

According to Machiavelli, what is the relationship between the actual and the ideal?

The ideal should be judged by the actual, not the actual by the ideal.

For Machiavelli, what is the relationship between the means and the end?

Not only does the end justify the means (any means that work), but the means even justify the end (the end is worth pursuing only if there are practical means to attain it).

For Machiavelli, what is the greatest good?

Success. (He is the father of pragmatism.)

What did Machiavelli think about morals?

He was an anti-moralist. A successful prince, he wrote, needs “to learn how not to be good” (The Prince, ch. 15), how to break promises, to lie, to cheat, and to steal (ch. 18).

How did he view religion?

He believed that every religion was a piece of propaganda whose influence lasted between 1,666 and 3,000 years. And he thought Christianity would end long before the world did.

He saw his life as a spiritual warfare against the Church and its propaganda.

Who were Machiavelli’s allies and to whom did he direct his philosophy?

Machiavelli wrote for and was supported by lukewarm Christians who loved their earthly fatherland more than heaven, Caesar more than Christ, social success more than virtue.

What was his goal?

Domination or control.

What were the two tools that were need to command men’s behavior and thus to control human history?

The pen (propaganda) and the sword (arms).

In his view, what determined all of life and history?

virtù (force)

fortuna (chance)

What is virtù?

strength

power

prowess

Virtù is not moral virtue, but rather the ability to impose one’s will on someone or something else.

What is fortuna?

luck

chance

fate (whether good or bad)

What is the formula for success?

maximize virtù

minimize fortuna

He ends The Prince with this shocking image: “Fortune is a woman, and if she is to be submissive it is necessary to beat and coerce her” (ch. 25).

What does all of Machiavelli’s advice boil down to?

How to move something from the fortuna category to the virtù category.

What is the relationship of laws and arms?

“You cannot have good laws without good arms, and where there are good arms, good laws inevitably follow” (ch. 12).

Machiavelli believed that “all armed prophets have conquered and unarmed prophets have come to grief” (ch. 6). Jesus, the supreme unarmed prophet, came to grief (he was crucified and not resurrected). But his message conquered the world through propaganda, through intellectual arms.

This was the war Machiavelli set out to fight.

How did social relativism emerge from Machiavelli’s philosophy?

He argued:

Morality can only come from society (since there is no God and no God-given universal natural moral law).

But every society originated in some revolution or violence.

Therefore, the foundation of law is lawlessness. The foundation of morality is immorality.

How did Machiavelli criticize Christian and classical ideals of charity?

He asked:

How do you get the goods you give away? By selfish competition. (All goods are gotten at another’s expense: if my slice of the pie is so much more, others’ must be that much less.)

Thus unselfishness depends on selfishness.

The argument presupposes materialism and it is flawed (spiritual goods do not diminish when shared or given away, and do not deprive another when I acquire them).

What was Machiavelli’s anthropology (view of human beings and their nature)?

Machiavelli believed we are all inherently selfish. There is no such thing as an innate conscience or moral instinct. The only way to make men behave morally is by force—in fact, totalitarian force, to compel them to act contrary to their nature.

If a man is inherently selfish, then only fear and not love can effectively move him. He wrote, “It is far better to be feared than loved ” (ch. 17).

Kreeft:

The most amazing thing about this brutal philosophy is that it won the modern mind, though only by watering down or covering up its darker aspects. Machiavelli’s successors toned down his attack on morality and religion, but they did not return to the idea of a personal God or objective and absolute morality as the foundation of society. Machiavelli’s narrowing down came to appear as a widening out. He simply lopped off the top story of the building of life; no God, only man; no soul, only body; no spirit, only matter; no ought, only is. Yet this squashed building appeared (through propaganda) as a Tower of Babel, this confinement appeared as a liberation from the “confinements” of traditional morality, like taking your belt out a notch.

Satan is not a fairy tale; he is a brilliant strategist and psychologist and he is utterly real. Machiavelli’s line of argument is one of Satan’s most successful lies to this day. Whenever we are tempted, he is using this lie to make evil appear as good and desirable; to make his slavery appear as freedom and “the glorious freedom of the sons of God” appear as slavery. The “Father of Lies” loves to tell not little lies but The Big Lie, to turn the truth upside down. And he gets away with it—unless we blow the cover of the Enemy’s spies.

February 23, 2015

Why an Actual Infinity Cannot Exist and Therefore We Know that the Universe Had a Beginning

Philosopher William Lane Craig has done more than any other contemporary to popularize and develop the Kalam Cosmological Argument, which is simple to formulate and difficult to refute. The premises of the argument are as follows:

Everything that begins to exist has a cause.

The universe begins to exist.

Therefore, the universe has a cause.

Dr. Craig has used Hilbert’s Infinite Hotel Paradox to show the absurdities of an actual infinity (as opposed to a potential infinity) existing. Maria Papova explains the origin and popularization of Hilbert’s paradox:

To help ordinary humans tussle with this extraordinary concept, German mathematician David Hilbert conceived of what is now known as the Infinite Hotel Paradox — a brilliant and mind-bending specimen of that neat intersection of science and philosophy: the thought experiment. Hilbert came up with the Infinite Hotel Paradox in 1924, but it was popularized only after his death by Russian-American theoretical physicist George Gamow’s 1947 book One Two Three . . . Infinity: Facts and Speculations of Science.

Jeff Dekofsky produced an animation for TED-Ed, which you can watch here:

You can watch below as Dr. Craig explains the concept and applies it to this argument:

A Crash Course on Influencers of Unbelief: Karl Marx

This will be an occasional series on some influential modern thinkers who influenced the world of unbelief. (For the first one on Freud, go here.)

These are notes based on an essay by Peter Kreeft, author of Socrates Meets Marx: The Father of Philosophy Meets the Father of Communism (St. Augustine’s Press, 2012).

Who was Karl Marx?

A German philosopher-economist and a revolutionary socialist who founded Communism.

When did he live?

1818-1883.

What is the significance of his philosophy?

Marxism is not the most important, the most imposing, or the most impressive philosophy in history.

But until recently, it has clearly been the most influential. In just two generations, Marxism inundated one-third of the world—a feat accomplished only twice in human history (by early Christianity and by early Islam).

What is Marx’s most famous work?

What is Marx’s most famous work?

The Communist Manifesto (1848), co-authored with Friedrich Engels.

What is the genre of The Communist Manifesto?

It is essentially a philosophy of history, past and future.

What was Marx’s view of the past?

Marx held a cynical view, reducing all of it to class struggle between:

oppressor and oppressed

master and slave

This includes all sorts of relationships, like:

king vs. people

priest vs. parishioner

guild-master vs. apprentice

husband vs. wife

parent vs. child

What was Marx’s view of the present?

There are only two classes:

the bourgeoisie (the “haves”) — the owners of the means of production.

the proletariat (the “have-nots”) — the non-owners of the means of production.

What was Marx’s view of future history?

Marx held a naïve vision:

The proletariat (the have-nots) must sell themselves and their labor to the bourgeoisie (the owners) until the communist revolution.

The communist revolution will eliminate (i.e., murder) the bourgeoisie

As a result, classes and class conflict will thus be abolished, ushering in a millennium of peace and equality

How was Marxism structurally and emotionally like a religion?

Marx took over the forms and the spirit of his Jewish religious heritage, but not the content. He retained all the major structural and emotional factors of biblical religion in a secularized form.

Marx, like Moses, is the prophet who leads the new Chosen People, the proletariat, out of the slavery of capitalism into the Promised Land of communism across the Red Sea of bloody worldwide revolution and through the wilderness of temporary, dedicated suffering for the party, the new priesthood.

The revolution is the new “Day of Yahweh,” the Day of Judgment

Party spokesmen are the new prophets

Political purges within the party to maintain ideological purity are the new divine judgments on the waywardness of the Chosen and their leaders.

Where did Marx’s idea’s come from?

Hegelian philosophy

Enlightenment rationalism

Economic reductionism

Utopian socialist thinkers

What was Marx’s relationship to Hegelian philosophy?

Marx said that he turned German idealist philosopher Georg Hegel (1770-1831) on his head. He transformed Hegel’s philosophy of “dialectical idealism” into “dialectical materialism.”

What radical ideas did Marx inherit from Hegel?

Monism. Everything is one; the distinction between matter and spirit is illusory. For Hegel, matter was only a form of spirit; for Marx, spirit was only a form of matter.

Pantheism. The distinction between Creator and creature is false. For Hegel, the world is made into an aspect of God (pantheism); for Marx, God is reduced to the world (atheism).

Historicism : Everything (even truth) changes; there is nothing above history to judge it; therefore, what is true in one era becomes false in another, or vice versa. Time = God.

Dialectic . History moves only by conflicts between opposing forces, a “thesis” vs. an “antithesis” evolving a “higher synthesis.” This applies to classes, nations, institutions and ideas. The dialectic continues until the kingdom of God finally comes. Hegel virtually identified this kingdom with the Prussian state. Marx internationalized it to the worldwide communist state.

Necessitarianism , or fatalism. The dialectic and its outcome are inevitable and necessary, not free.

Statism . There is no eternal, trans-historical truth or law, therefore the state is supreme and uncriticizable. Marx again internationalized Hegel’s nationalism.

Militarism . There is no universal natural or eternal law above states to judge and resolve differences between them, therefore war is inevitable and necessary as long as there are states.

What was Marx’s economic reductionism?

The traditional view of the relationship of man and society is:

Mind rules body.

Man rules his societies.

Society rules its economics.

Marx stood each of these on its head:

Within man, thought is totally determined by matter.

Man is totally determined by society.

Society is totally determined by economics.

What is communism?

Marx wrote: “The theory of communism may be summed up in the single phrase: abolition of private property.”

How does Marx deal with the objection that Communism abolishes many good things?

Marx does not deny that Communism does away with:

privacy

private property

individuality

freedom

motivation to work

education

marriage

family

culture

nations

religion

philosophy

However, Marx says that capitalism has already abolished them. For example, he argues that “the bourgeois sees in his wife a mere instrument of production.”

How does Marx respond to the objection that Marxist materialism contradicts itself?

The objection: If ideas are nothing but products of material and economic forces, then communist ideas are only that too. To attack the grounds of thought is to attack one’s own attack.

Marx sees this and admits it. But the functions of words, in his view, is not to prove what is true but to encourage the revolution. Marx is essentially a pragmatist.

What are some further objections to Marxism?

Marx’s appeal for “Working men of all countries, unite!” even if pragmatic, is still self-defeating. Marx believes in fate, not free will, and the revolution is inevitable. Therefore, he can’t appeal to free will while denying it.

The predictions simply have not worked. The revolution did not happen when and where Marxism predicted. Capitalism did not disappear—nor did the state, the family, or religion.

Communism has not produced contentment and equality anywhere it has gained power.

Kreeft:

All Marx has been able to do is to play Moses and lead fools backward into the slavery of Egypt (worldliness). The real Liberator is waiting in the wings for the jester who now “struts and frets his hour upon the stage” to lead his fellow “fools to dusty death” the one topic Marxist philosophers refuse to face.

February 21, 2015

What Is the Deepest Issue Facing the Church Today?

J. P. Moreland offers an interesting answer:

The deepest issue facing the church today is this:

Are its main creeds and central teachings items of knowledge or mere matters of blind faith, privatized personal beliefs, issues of feeling to be accepted or set aside according to the individual or cultural pressures that come and go?

Do these teachings have cognitive and behavioral authority that set a worldview framework for approaching science, art, ethics—indeed, all of life? Or is cognitive and behavioral authority set by what scientists or the American Psychiatric Association say, by what Gallup polls tell us is embraced by cultural and intellectual elites. . . .

The question of whether or not Christianity provides its followers with a range of knowledge is no small matter. It is a question of authority for life and death, and lay brothers and sisters are watching Christian thinkers and leaders to see how we approach this matter.

—J. P. Moreland, The Soul: How We Know It’s Real and Why It Matters (Chicago: Moody Publishers, 2014), 14.

February 20, 2015

A Crash Course on Influencers of Unbelief: Sigmund Freud

This will be an occasional series on some influential modern thinkers who influenced the world of unbelief. These are notes based on an essay by Peter Kreeft, author of Socrates Meets Freud: The Father of Philosophy Meets the Father of Psychology (St. Augustine’s Press, 2014).

Who was Sigmund Freud?

An Austrian neurologist and author who founded psychoanalysis.

When did he live?

From 1856 to 1939. (For American point of reference, he was born 5 years before the US Civil War and died in the same month as World War II began.)

What were his main vocations and what was his influence in each?

He was the inventor of the practical therapeutic technique of psychoanalysis. (He was a genius; psychologists today stand in his debt for some of his insights.)

He was a theoretical psychologist. (Like Columbus, he mapped out some new continents but made some major mistakes.)

He was a philosopher and religious thinker. (Here he was strictly an amateur and little more than an adolescent.)

How did Freud approach psychology?

He wanted to reduce the complex to the controllable, and he wanted to make psychology into an exact science. (This doesn’t work, though, because man is never only an object but also a subject.)

What was his greatest work?

The Interpretation of Dreams (1900). He rightly emphasized the subconscious forces that move us, but he underemphasized their depth and complexity.

What was Freud’s most influential teaching?

Sexual reductionism.

As an atheist, Freud reduced God to the dream of a man.

As a materialist, Freud ultimately reduced man to sex.

God → dream of a man

man → his body

the human body → animal desire

desire → sexual desire

sexual desire → genital sex

In what ways do thinkers like Freud confuse wants and needs?

Premise 1 below may be true, but premises 2, 3, and 4 do not follow from it.

All normal human beings have sexual wants or desires.

These sexual wants or desires are needs or rights.

No one can be expected to live without gratifying these sexual needs or rights.

To suppress these sexual wants or desires is psychologically unhealthy.

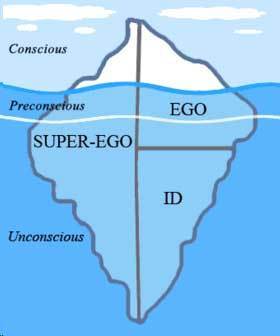

How did Freud divide up the human psyche?

He identified three divisions, but these are not the same as the traditional notions of appetite, will, and intellect (and conscience).

Super-ego. The unfree, passive reflection in an individual’s psyche of societal “thou shalt nots”—restrictions on his desires. We need to realize that our “own” insights into good and evil is simply a mirror of man-made social laws.

Ego. A mere facade; there is no free will.

Id. The only real self is impersonal; it’s comprised simply of animal desires.

Just as Freud denied God (“I Am”), he denies God’s image, the human “I.”

For Freud, what is the fundamental illusion of humanity?

Religion.

What did he see as the only light?

Materialistic scientism.

What are his most famous anti-religion books?

Moses and Monotheism (1939)

The Future of an Illusion (1927)

Where did Freud believe that the infantile illusion of religion came from?

Four sources:

Ignorance . Religion is a pre-scientific guess at how nature works (if there is thunder, there must be a Thunderer, a Zeus).

Fear . Religion is our invention of a heavenly substitute for the earthly father (he dies, gets old, goes away, or sends his children out of the secure home into the frightening world of responsibility).

Fantasy . God is the product of wish-fulfillment (there’s an all-powerful providential force behind the terrifyingly impersonal appearances of life).

Guilt. God is the ensurer of moral behavior (once, long ago, a son killed his father, the head of a great tribe; that primal murder has haunted the human race’s subconscious memory ever since).

What was Freud’s most philosophical book?

Civilization and Its Discontents (1930).

What was the argument?

The meaning of life and human happiness are unattainable. But we can experience psychotherapy, moving ”from unmanageable unhappiness to manageable unhappiness.”

We are animals seeking pleasure, motivated only by “the pleasure principle.”

We need the order of civilization to save us from the pain of chaos.

But the restrictions of civilization curtail our desires.

So the very thing we invented as a means to our happiness becomes our obstacle.

What did he mean by eros and thanatos?

The pleasure principle leads us in two opposite directions:

Eros leads us forward, into life, love, the future and hope.

Thanatos leads us back to the womb, where alone we had no pain.

We resent life and our mothers for birthing us into pain. .

Kreeft:

Freud prophetically saw the power of the death wish in the modern world and was unsure which of these two “heavenly forces,” as he called them, would win out. He died an atheist but almost a mystic. He had enough of the pagan in him to offer some profound insights, usually mixed up with outrageous blind spots. He calls to mind C.S. Lewis’ description of pagan mythology: “gleams of celestial strength and beauty falling on a jungle of filth and imbecility.”

What raises Freud far above Marx and secular humanism is his insight into the demon in man, the tragic dimension of life and our need for salvation. Unfortunately, he saw the Judaism he rejected and the Christianity he scorned as fairy tales, too good to be true. His tragic sense was rooted in his separation between the true and the good, “the reality principle” and happiness.

Only God can join them at their summit.

An Interview with Wesley J. Smith on the Culture of Death and Legalized Suicide

Wesley J. Smith is a Senior Fellow in Human Rights and Bioethics at the Discovery Institute, a consultant to the International Task Force on Euthanasia and Assisted Suicide, and a special consultant for the Center for Bioethics and Culture.

He is the author of several books: Forced Exit: Euthanasia, Assisted Suicide and the New Duty to Die is a classic on the assisted-suicide/euthanasia movement; Culture of Death: The Assault on Medical Ethics in America critiques the dangers of the modern bioethics movement; Consumer’s Guide to a Brave New World explores the morality, science, and business aspects of human cloning, stem cell research, and genetic engineering; A Rat Is a Pig Is a Dog Is a Boy: The Human Cost of the Animal Rights Movement looks at the animal rights/liberation movement; and his most recent book, The War on Humans, critiques the radicalism of the environmental movement.

In the following, he sits down for a conversation with Dead Reckoning TV to talk with Brian Mattson and Jay Friesen:

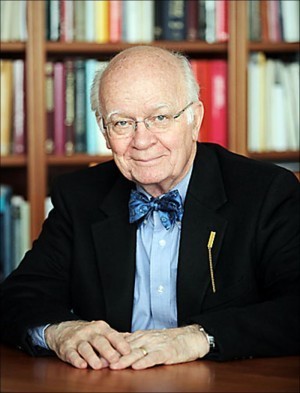

Martin Marty on Why You Should Read a Non-Lutheran’s Book about Luther on the Christian Life

Martin E. Marty (b. 1928) is one of the most distinguished and prominent interpreters of religion and culture in the 20th century. After receiving a PhD from the University of Chicago in 1956, he served as a Lutheran pastor in the suburbs of Chicago (1952-1962) before becoming a professor at the University of Chicago Divinity School (1963-1998), where the Martin Marty Center for the Advanced Study of Religion is named in his honor.

Martin E. Marty (b. 1928) is one of the most distinguished and prominent interpreters of religion and culture in the 20th century. After receiving a PhD from the University of Chicago in 1956, he served as a Lutheran pastor in the suburbs of Chicago (1952-1962) before becoming a professor at the University of Chicago Divinity School (1963-1998), where the Martin Marty Center for the Advanced Study of Religion is named in his honor.

Professor Marty served as president of both the American Academy of Religion and the American Society of Church History, and he has been a senior editor of The Christian Century since 1956.

His biography of Martin Luther (yes, Martin Marty on Martin Luther) was published in 2004 in the Penguin Lives series, and remains perhaps the best short introduction available for the great Reformer’s life and contribution.

He recently penned the afterword to Carl Trueman’s new book, Luther on the Christian Life: Cross and Freedom (Crossway, 2015), praising its unique contribution and explaining how it will contribute to the actual living of the Christian life for those who read it. Professor Marty’s reflections are reprinted below.

Author Carl Trueman has done readers a favor by viewing Martin Luther through a particular prism, one whose perspective can help change lives. Had he simply written a biography, he could have performed a service to readers in general, people who seek to be informed about important topics. While researching he could have scaled the figurative Everest of the 120-plus volumes of Luther’s writings and tried to condense his vision from there in the pages of this relatively short book. Additionally, he would have had to do justice to some of the literally thousands of writings about the man regularly measured to be among the five most significant figures in the millennium past. Readers might have thereupon been dazzled or benumbed by the amount of data served up by often profound and elegant biographers.

Trueman’s acceptance of an assignment in this particular series meant that the authorial choices he made had to relate, as this book does, to Luther’s ponderings on and expressions of the Christian life. It was to contribute to the living of lives among readers in our generation. Accepting that choice meant leaving out many tantalizing subjects, since Luther touched on so many dimensions, events, and themes of human existence. Let it also be said that the author’s need to select also helped save him from having to deal with embarrassing or appalling Luther topics, for example, his late-in-life notorious anti-Semitism—on which, to be sure, Trueman does touch with some pain and much fairness.

Luther on the Christian life? More predictable and more easily handled themes could have been “Luther on Christian doctrine” or “Luther on Christian preaching,” or . . . Think how much easier an author would have it if he dealt with a figure like John Wesley or Saint Francis or hundreds of others whose specialty is devotion to holiness, sanctification, or ethics, as Luther’s was not or has not often been perceived to be. Of course, Trueman could not have commented on the Bible, as he has done in discussing writings that make up much of Luther’s works, without having dealt with the many incentives to, and models of, the Christian life.

What readers must by the end have found remarkable is the way Dr. Trueman has brought clarity and some sense of system to the often obscure, paradoxical, and anything-but-systematic writings of Luther on the Christian life. I would argue that Trueman has served well by keeping his feet on firm ground as he has stood on an approach to Christian life which he sometimes calls Presbyterian or Reformed or evangelical, often in differing combinations. He has never done that flat-footedly or heavy-footedly, but usually incidentally, since he was not writing a book of Presbyterian-Reformed-evangelical doctrine, which can easily be learned by consulting encyclopedias or works of polemics. His intent was not overtly to say, “Notice us! We’re better than you are!” but always to sharpen his points and add color and clarity to his narrative through comparison.

What, we might ask, is the potential profit from his viewing Luther through non-Lutheran eyes? (Readers need little reminder that books on Luther through Lutheran eyes, for all their worth, can often miss much or distort some of what they display or argue!) The profit in this instance? Such an approach helps readers of various confessional, denominational, and personal stances to move from the known—their own understandings—to the relatively unknown “other.” Elements of faith as they show up in the Christian life stand in sharper relief when the comparative approach illumines what was already known and probably taken for granted.

To take an example: when I deal with Muslim worshipers and theologians, as I have done in dialogue with Muslims or in an Islamic school, I later reflect with a greater awareness of the role of the doctrine of the Trinity or witness to the incarnation when Muslim students show puzzlement about Christian Trinitarian and incarnational talk. Why are these two topics so important to us Christians, we are asked? What are the sources and consequences of our beliefs? In the case not of Christians relating to Muslims but of Christians-of-one-sort in relation to Christians-of-another-sort, as it shows up in ecumenical conversation or comparative courses on Christian ethics, the gulfs between commitments in various confessional camps may often look like mere nuances, subtleties, or subjects for Pecksniffian polemicists to distort. Yet in choices made about the life of Christians, these differences can be either alienating or positively informative. The book you have just read will contribute to your living of the Christian life. A rereading—which I picture will be an enjoyable exercise—will confirm this.

Martin Luther’s pursuits thus jostle those who share them through the book’s realistic readiness to deal with Anfechtung, a peculiar sort of doubting. After reading this, they may well be more ready to deal with their own doubts. Those who had been casual about drawing on Scripture to guide their daily lives cannot help but draw closer, thanks to this account of Luther’s probes. Also, in the past century Roman Catholic devotion to scriptural studies is often acknowledged to have been enriched by Luther’s drawing on the Bible for the deepening of the Christian life.

I live across the street from a strategic and compelling Presbyterian church and on occasion am able to attend worship there. As I listen to and share in the hymnody, prayer forms, ethical injunctions, and proclamations of the gospel, I join other non-Presbyterians in affirmation, celebration, and a feeling of being in company or at home. Yet there are not-infrequent moments when, for example, a preacher will explain something to the diverse congregants on a particular day, while wrestling with a particular text, by making an explicit reference to the fact that something emphasized in the Presbyterian tradition can provide color and impetus for the living of the Christian life.

Such an approach magnificently stands out and is helpful in a world where Christians often have to settle for banal, wishy-washy expressions that do little to help inform the Christian life. For example, we who are not Mennonites can learn from their peace witness without becoming Mennonites, or can draw closer to God through the liturgical and musical witness of Episcopalians without having to “jump ship” and sail on an Anglican vessel. As this book which you readers have just finished makes clear, the pursuit of the Christian life is not a matter of picking and choosing, or gazing through a kaleidoscope with jittery images, but is a serious business of seeking perspective and focus. Readers of many sorts will be more equipped than before to share that pursuit, and will want to join me in expressing gratitude to author Carl Trueman.

Martin E. Marty

Emeritus Professor at the University of Chicago

author of Martin Luther

For more information on the book, including other endorsements and sample material, go here.

For more information on the series, go here.

Photo image credit: Tony Reinke

February 18, 2015

You Say You Want a (Sexual) Revolution?

Ross Douthat looks at the sexual revolution from two angles: (1) its ostensibly egalitarian facade, and (2) its exploitative and predatory nature:

Viewed from one angle, the sexual revolution looks obviously egalitarian. It’s about extending to everyone the liberties — the freedom to be promiscuous, to pursue sexual fulfillment without guilt — that were once available only to privileged cisgendered heterosexual males. It’s about ushering in a society where everyone can freely love and take pleasure in anyone and anything they want.

But viewed from another angle, that same revolution looks more like a permission slip for the strong and privileged to prey upon the weak and easily exploited. This is the sexual revolution of Hugh Hefner and Larry Flynt and Joe Francis and roughly 98 percent of the online pornography consumed by young men. It’s the revolution that’s been better for fraternity brothers than their female guests, better for the rich than the poor, better for the beautiful than the plain, better for liberated adults than fatherless children . . . and so on down a long, depressing list. At times, as the French writer Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry recently suggested, this side of sexual revolution looks more like “sexual reaction,” a step way back toward a libertinism more like that of pre-Christian Rome — anti-egalitarian and hierarchical, privileging men over women, adults over children, the upper class over the lower orders. . . .

He then shows the way in which these two aspects try to converge rather than conflict:

But the essential dream of our age isn’t conflict; it’s a synthesis, in which the aristocratic thrills of libertinism are somehow preserved but their most exploitative elements are rendered egalitarian and safe.

The hope, in other words, is that we can eventually have the fun of Rome without all the nasty bits: Contraception and abortion will pre-empt the inconvenient infant, age-of-consent laws will make sure that young people’s initiation doesn’t start too early, and with enough carefully drawn up regulations for initiating intercourse we can all experience the courts of Tiberius and Heliogabalus without anybody getting hurt.

So our sexual egalitarians don’t want to shut down the party or end the bacchanal. They just want hookup culture to be governed by affirmative consent, for prostitutes to become empowered sex workers, for misogynistic porn to be balanced out by feminist alternatives, for dangerous patriarchal polygamy to give way to safe egalitarian polyamory, and for De Sade’s Justine to find happiness as a submissive protected by her safe words.

You can read the whole thing here.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers