Justin Taylor's Blog, page 81

March 17, 2015

How Historians Ask Questions of Primary Sources

Professor Eric Foner of Columbia University is one of the preeminent historians working today. His Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution is a landmark book, and The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery is considered a definitive look at the subject. His most recent book is called Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad.

Professor Eric Foner of Columbia University is one of the preeminent historians working today. His Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution is a landmark book, and The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery is considered a definitive look at the subject. His most recent book is called Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad.

Dr. Foner (age 72) has taught a three-class unit on the Civil War for over three decades. This is his last year teaching the class, and he has partnered with edX to make them available online for free.

One helpful feature of these classes is that they provide undergraduate students—and the rest of us—a primary on how to question, interpret, and discuss the backbone of historical research: primary sources. I’ve taken the material and broken it up into a Q&A below. At the end, you’ll see an example of a primary source, some answers to some questions, and some links for you to try it yourself.

What is a primary source?

What is a primary source?

A primary source is a document, image, or artifact that provides first-hand or eyewitness information about a particular historical person, event, or idea.

What are some typical examples of primary sources?

Typical examples include

letters

diaries

newspapers

photographs

paintings

maps

oral histories

How can primary sources help historians?

Primary sources can help historians answer research questions and gather evidence to support their arguments.

For scholars, these materials—and the questions they raise—constitute the foundational elements of historical work. Interrogating primary sources is one of the fundamental tasks every historian must perform in order to craft a nuanced, contingent, and evidence-based argument.

How do different types of texts offer varying potential questions and answers?

Wills, financial records, and military accounts document the day-to-day functioning of a society.

Photographic albums, engravings, and printed ephemera provide glimpses into the iconography of a culture.

Personal belongings and correspondence beckon toward the intimate details of private lives, while mass-produced keepsakes blur the lines between historical evidence and pop-cultural kitsch.

What starting questions should one ask of a document?

When working with primary sources it is important to begin with a few observational and interpretive questions, which can often suggest future research directions.

When was this source created? If the source is not dated, can you use any contextual clues to make an educated guess?

Who created it? If no individual’s name is apparent, can you guess their position within society?

What was the original purpose of this source? Why was it created and what was its intent?

Who is the intended audience of the source? How does this influence the way information is presented?

Is there anyone, besides the author, who is represented in the source? What can you learn about them?

How has the meaning of the source changed over time?

How might a historian use this source as a piece of evidence? What research questions might it help to answer? What story might you tell using this source?

Can you give an example?

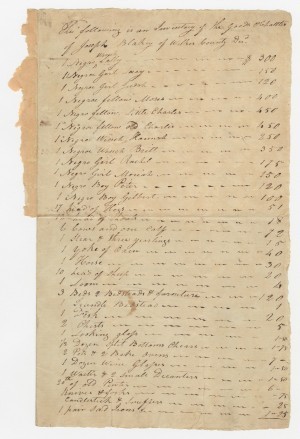

The following (Cyrus Gordon – Abraham Lincoln Collection, 1846-1980, Columbia University, Rare Book & Manuscript Library) is a Bill of Sale from the State of Louisiana. You can click the image to enlarge it:

Using the questions above, the answers would be along the following lines:

October 4, 1859

Anthony Wiesemann of St. Louis, Missouri.

This document is a bill of sale for a slave woman. This was a legal document meant to transfer property rights to this woman from Wiesemann to her new owner, Denis C. Daniel of St. Mary Parish, Louisiana for the sum of $1,450. [FYI: this is equivalent to $37,658.98 in 2014 dollars.]

The primary audience for this document was the purchaser, Denis C. Daniel, and his heirs.

This document also represents the subject of the sale, “a certain negress, slave for life, named Sarah Jane, aged 17.”

While this source originally served as a legal document guaranteeing property rights, today it shows us how people were held and valued as property.

A historian might use this document to show how the demand for slaves continued to grow in the years immediately before the Civil War.

These questions and answers are really just the beginning. If you go here, and scroll down to Week 3, you can see another document and some initial observations and questions from a historian of women and gender, an environmental historian, and a labor historian. Different questions, angles, and comparisons can lead to new discoveries and lines of inquiry.

How can I try this for myself?

To use the rubric above to look at primary sources from the Civil War era, go here, here, and here.

What are some further resources for learning more about the use of primary sources in historical research?

Thomas Andrews and Flannery Burke, “What Does it Mean to Think Historically?” Perspectives on History 45, no. 1 (January 2007).

Keith C. Barton, “Primary Sources in History: Breaking Through the Myths,” The Phi Delta Kappan 86, no. 10 (June 2005): 745-53.

Sam Wineburg, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001).

March 16, 2015

Happy Saint Patrick

From Timothy Paul Jones and Church History Made Easy:

For more on the life of Patrick and his influence, you can listen to this lecture or read this book by Michael Haykin (the cover notwithstanding, it is not a children’s book!).

March 13, 2015

22 Benefits of Meditating on Scripture

Joel Beeke, in his essay on “The Puritan Practice of Meditation,” writes that “The Puritans devoted scores of pages to the benefits, excellencies, usefulness, advantages, or improvements of meditation.” Dr. Beeke lists some of the benefits as follows:

Meditation helps us focus on the Triune God, to love and to enjoy Him in all His persons (1 John 4:8)—intellectually, spiritually, aesthetically.

Meditation helps increase knowledge of sacred truth. It “takes the veil from the face of truth” (Prov. 4:2).

Meditation is the “nurse of wisdom,” for it promotes the fear of God, which is the beginning of wisdom (Prov. 1:8).

Meditation enlarges our faith by helping us to trust the God of promises in all our spiritual troubles and the God of providence in all our outward troubles.

Meditation augments one’s affections. Watson called meditation “the bellows of the affections.” He said, “Meditation hatcheth good affections, as the hen her young ones by sitting on them; we light affection at this fire of meditation” (Ps. 39:3).

Meditation fosters repentance and reformation of life (Ps. 119:59; Ez. 36:31).

Meditation is a great friend to memory.

Meditation helps us view worship as a discipline to be cultivated. It makes us prefer God’s house to our own.

Meditation transfuses Scripture through the texture of the soul.

Meditation is a great aid to prayer (Ps. 5:1). It tunes the instrument of prayer before prayer.

Meditation helps us to hear and read the Word with real benefit. It makes the Word “full of life and energy to our souls.” William Bates wrote, “Hearing the word is like ingestion, and when we meditate upon the word that is digestion; and this digestion of the word by meditation produceth warm affections, zealous resolutions, and holy actions.”

Meditation on the sacraments helps our “graces to be better and stronger.” It helps faith, hope, love, humility, and numerous spiritual comforts thrive in the soul.

Meditation stresses the heinousness of sin. It “musters up all weapons, and gathers all forces of arguments for to presse our sins, and lay them heavy upon the heart,” wrote Fenner. Thomas Hooker said, “Meditation sharpens the sting and strength of corruption, that it pierceth more prevailingly.” It is a “strong antidote against sin” and “a cure of covetousness.”

Meditation enables us to “discharge religious duties, because it conveys to the soul the lively sense and feeling of God’s goodness; so the soul is encouraged to duty.”

Meditation helps prevent vain and sinful thoughts (Jer. 4:14; Matt. 12:35). It helps wean us from this present evil age.

Meditation provides inner resources on which to draw (Ps. 77:10-12), including direction for daily life (Prov. 6:21-22).

Meditation helps us persevere in faith; it keeps our hearts “savoury and spiritual in the midst of all our outward and worldly employments,” wrote William Bridge.

Meditation is a mighty weapon to ward off Satan and temptation (Ps. 119:11,15; 1 John 2:14).

Meditation provides relief in afflictions (Is. 49:15-17; Heb. 12:5).

Meditation helps us benefit others with our spiritual fellowship and counsel (Ps. 66:16; 77:12; 145:7).

Meditation promotes gratitude for all the blessings showered upon us by God through His Son.

Meditation glorifies God (Ps. 49:3).

You can read the whole essay here.

March 12, 2015

Why the Christian Narrative Is Not a “Metanarrative”

In The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (1979 French edition; 1984 English translation), philosopher Jean-François Lyotard argued that the “postmodern” outlook can be simplistically defined as “incredulity toward metanarratives”—that is, mistrust or skepticism about the totalizing stories of modernism and their grounds for universal legitimacy.

In response to this line of thinking, it is not uncommon for Christians to suggest that Christianity itself is a metanarrative—the ultimate universal story.

But Michael Horton (and others) argue that this well-intentioned move is based on a misunderstanding of what “metanarratives” mean. Horton writes, “For Lyotard, a metanarrative is a certain way in which modernity has legitimized its absolutist discourse and originated or grounded it in autonomous reason.” The biblical storyline is not grounded in this way, so while it is a mega-story, it is not really a meta-narrative (which refers to the level of discourse and its basis, not to the size and scope of the story).

Horton writes:

All of our worldviews are stories. Christianity does not claim to have escaped this fact. The prophets and apostles were fully conscious of the fact that they were interpreting reality within the framework of a particular narrative of creation, fall, redemption, and consummation, as told to a particular people (Israel) for the benefit of the world. The biblical faith claims that its story is the one that God is telling, which relativizes and judges the other stories about God, us, and the world. . .

Horton continues:

The prophets and apostles did not believe that God’s mighty acts in history (meganarratives) were dispensable myths that represented universal truths (metanarratives). For them, the big story did not point to something else beyond it but was itself the point. God really created all things, including humans in his image, and brought Israel through the Red Sea on dry ground. He really drowned a greater kingdom than Pharaoh and his army in Christ’s death and resurrection. God’s mighty acts in history are not myths that symbolize timeless truths; they create the unfolding plot within which our lives and destinies find the proper coordinates.

Metanarratives give rise to ideologies, which claim the world’s allegiance even, if necessary, through violence. The heart of the Christian narrative, however, is the gospel—the good news concerning God’s saving love and mercy in Jesus Christ. It is the story that interprets all other stories, and the lead character is Lord over all other lords. . . .

Horton shows how the Christian meganarrative is a “counterdrama” to all of the meganarratives and metanarratives of this passing age:

It speaks of the triune God who existed eternally before creation and of ourselves as characters in his unfolding plot. Created in God’s image yet fallen into sin, we have our identity shaped by the movement of this dramatic story from promise to fulfillment in Jesus Christ. This drama also has its powerful props, such as preaching, baptism, and the Supper—the means by which we are no longer spectators but are actually included in the cast. Having exchanged our rags for the riches of Christ’s righteousness, we now find our identity “in Christ.” Instead of God being a supporting actor in our life story, we become part of the cast that the Spirit is recruiting for God’s drama. The Christian faith is, first and foremost, an unfolding drama. Geerhardus Vos observed, “The Bible is not a dogmatic handbook but a historical book full of dramatic interest.” This story that runs from Genesis to Revelation, centering on Christ, not only richly informs our mind; it captivates the heart and the imagination, animating and motivating our action in the world. When history seems to come to a standstill in sin, guilt, and death, the prophets direct God’s people to God’s fulfillment of his promise in a new covenant.

—Michael S. Horton, The Christian Faith: A Systematic Theology for Pilgrims on the Way (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2011), chapter 1.

March 11, 2015

Are the Religion Clauses of the Constitution Contradictory?

The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution says that

The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution says that

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion . . .”

followed immediately by the Free Exercise Clause:

“or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

Together these are called the “Religion Clauses” of the First Amendment.

Some people suggest that they are contradictory: the Establishment Clause encourages the exercise of “religion” in every possible sense, and at yet the purpose of the Free Exercise Clause is to keep religion from being practiced to such a degree that politics are influenced.

Political philosopher J. Budziszewski rebuts the argument:

The Free Exercise Clause does not say that the government should encourage the exercise of religion in every possible sense.

What it says is that Congress must not prohibit it. That’s all.

The Establishment Clause does not say that the government should keep religion from influencing politics.

What it says is that Congress must not make laws concerning official churches, like the Church of England. That’s all.

There is no conflict whatsoever between saying that the national legislature must not prohibit the practice of faith, and saying that it must not make laws concerning official churches.

Conflict arises only when you try to make the clauses mean more than they do.

Budziszewski goes on to argue that the chief reasons advance for the Religion Clauses were themselves religious:

The Framers didn’t want the practice of faith prohibited, because they thought we have duties to God.

But they didn’t want Congress to get into the official church business, because they thought religious truth is best promoted by religious competition.

The states, and the people thereof, were left to do as they thought best.

March 8, 2015

Why Jerram Barrs Read “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows” Six Times in Six Months

Jerram Barrs of Covenant Theological Seminary explains below why he deeply loves J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. (Spoilers included.)

Barrs explains more about this in his book Echoes of Eden: Reflections on Christianity, Literature, and the Arts.

.

March 6, 2015

Watch Mike Reeves Teach on the English Reformation and the Puritans

This is a great pairing: one of my favorite teachers (Mike Reeves) paired with one of my favorite resources (Ligonier’s DVD/CD teaching series) on a fascinating period in church history (the English Reformation and the Puritans).

Here is a description of the series:

Few stories contain heroism, betrayal, ricocheting monarchs, bold stands against repressive authorities, and redemption like this one. And fewer generations have modeled commitment to the gospel and the application of God’s Word like the Puritans of England. In this 12-part series, Dr. Michael Reeves surveys Puritan theology and the work of the Holy Spirit when the Reformation flourished in England. Major milestones of this movement underscore the Puritan’s special place in history, as they displayed spiritual wisdom and discernment still benefiting pulpits and believers today.

You can watch the first session, on “William Tyndale and the English Reformers” below for free:

Here’s a description of that first session:

The Reformation in England is a thrilling story of the recapturing of God’s grace. In this first lesson, Dr. Reeves relates the emergence of the English Reformation in connection to influences outside the country, especially Erasmus and Luther. We then learn of the foundational role played by Thomas Bilney and the White Horse Inn within England. The lesson culminates with a focus on the English Reformer William Tyndale, particularly in connection to his translation of the Bible into English. Such forbidden labors and the product that resulted not only led to his martyrdom but also catalyzed the Reformation cause in England.

You can purchase the audio or video set of additional sessions here, or get individual sessions one at a time.

You can also download a study guide for free.

For Robert Godfrey’s church history survey, which I highly recommend, go here.

March 4, 2015

FAQ on the Human Soul

Some notes from J. P. Moreland’s book, The Soul: How We Know It’s Real and Why It Matters (Chicago: Mood Press, 2014).

Some notes from J. P. Moreland’s book, The Soul: How We Know It’s Real and Why It Matters (Chicago: Mood Press, 2014).

What is dualism?

The view that the soul is an immaterial thing different from the body and brain.

What is substance dualism?

The view that a human person has both

a brain that is a physical thing with physical properties, and

a mind or soul that is a mental substance and has mental properties.

What is Thomistic substance dualism?

The view that the (human) soul

diffuses,

informs (gives form to),

unifies,

animates, and

makes human

the (human) body.

The body is not a physical substance, but rather an ensouled physical structure such that if it loses the soul, it is no longer a human body in a strict, philosophical sense.

What is the soul?

The soul is a substantial, unified reality that informs (gives form to) its body.

The soul is to the body like God is to space—it is fully “present” at each point within the body.

The soul and body relate to each other in a cause-effect way.

Do animals have souls?

Animals have a soul, but it is not as richly structured as the human soul. It does not bear the image of God, and it is far more dependent on the animal’s body and its sense organs than is the human soul.

What are some a rguments for substance dualism and the immaterial nature of the soul?

1. Our basic awareness of the self

We are aware of our own self as being distinct from our bodies and from any particular mental experience we have, and as being an uncomposed, spatially extended, simple center of consciousness.

This grounds my properly basic belief that I am a simple center of consciousness.

In virtue of the law of identity, we then know that we are not identical to our body, but to our soul.

2. Unity and the first-person perspective

If I were a physical object (a brain or body), then a third-person physical description would capture all the facts that are true of me.

But a third-person physical description does not capture all the facts that are true of me.

Therefore, I am not a physical object. Rather, I am a soul.

3. The modal argument

I am possibly disembodied (I could survive without my brain or body).

My brain or body are not possibly disembodied (they could not survive without being physical).

Therefore, I am not my brain or body, I am a soul.

4. Sameness of the self over time

A physical object composed of parts cannot survive over time as the same object if it comes to have different parts.

My body and brain are physical objects composed of parts that are constantly changing, and therefore cannot survive over time as the same object.

However, I do survive over time as the same object.

Therefore, I am not my body or my brain, but a soul.

What is the relevance of neuroscientific data to whether or not we have a soul?

Neuroscience is a wonderful tool, but it is inept for resolving disputes about the nature and existence of consciousness and the soul. The central issues in those disputes include philosophical, theological, and commonsense topics. Neuroscientific data are simply irrelevant for addressing those topics.

Neuroscience shows correlation between mind and brain, not that mind and brain are identical.

How is the law of identity relevant to this relationship?

Leibniz’s law of the indiscernability of identicals states that for any entities x and y, if x and y are identical, then any truth that applies to x will apply to y as well.

Some things are true of the mind or its states that are true of the brains or its states; therefore, physicalism is false and dualism (provided it is the only other option) is true.

What are the states of the soul?

Just as water can be in a cold or hot state, so the soul can be in a feeling or thinking state. Here are five such states:

sensation: a state of awareness, a mode of consciousness (e.g., a conscious awareness of sound or pain)

thought: a mental content that can be expressed as an entire sentence and that only exists while it is being thought

belief: a person’s view, accepted to varying degrees of strength, of how things really are

desire: a certain inclination to do, have, avoid, or experience certain things

act of will: a volition or choice, an exercise of power, an endeavoring to do a certain thing, usually for the sake of some purpose or end

What are the faculties of the soul?

The soul has a number of capacities that are not currently being actualized or utilized.

Capacities come in hierarchies:

First-order capacities (e.g., I have the first-order capacity or ability to speak English)

Second-order capacities to have first-order capacities (e.g., I have the potential to speak Russian, though it is not actualized)

And so forth

Higher-order capacities are realized by the development of lower-order capacities under them.

The capacities within the soul fall into natural groupings called faculties. A faculty is a “compartment” of the soul that contains a natural family of related capacities. For example:

Sensory faculties

sight (All the soul’s capacities to see are part of the faculty of sight. If my eyeballs are defective, then my soul’s faculty of sight will be inoperative just as a driver cannot get to work in his car if the spark plugs are broken. Likewise, if my eyeballs work but my soul is inattentive—say I am daydreaming—then I won’t see what is before me either.)

smell

touch

taste

hearing

The will: a faculty of the soul that contains my abilities to choose

Emotional faculties: one’s abilities to experience fear, love, and so forth

Mind and spirit

Mind: that faculty of the soul that contains thoughts and beliefs along with the relevant abilities to have them

Spirit: that faculty of the soul through which the person relates to God (Ps 51:10; Rom 8:16; Eph 4:23) [prior to regeneration, most of the capacities of the unregenerate spirit are dead and inoperative; at the new birth, God implants new capacities in the spirit]

March 3, 2015

Lifelong Lessons in Humility from Our Lord

From a sermon by the Church Father Basil of Caesarea (c. 330-379):

In everything which concerns the Lord we find lessons in humility.

As an infant, he was straightway laid in a cave, and not upon a couch but in a manger.

In the house of a carpenter and of a mother who was poor, he was subject to his mother and her spouse.

He was taught and he paid heed to what he needed not to be told.

He asked questions, but even in the asking he won admiration for his wisdom.

He submitted to John—the Lord received baptism at the hands of his servant.

He did not make use of the marvelous power that he possessed to resist any of those who attacked him, but, as if yielding to superior force, he allowed temporal authority to exercise the power proper to it.

He was brought before the high priest as though a criminal and then led to the governor.

He bore calumnies in silence and submitted to his sentence, although he could have refuted the false witnesses.

He was spat upon by slaves and by the vilest menials.

He delivered himself up to death, the most shameful death known to men.

Thus, from his birth to the end of his life, he experienced all the exigencies that befall mankind and, after displaying humility to such a degree, he manifested his glory, associating with himself in glory those who had shared his disgrace.

—Basil of Caesarea, Homily 20.6, as cited in Michael A. G. Haykin, Rediscovering the Church Fathers: Who They Were and How They Shaped the Church (Wheaton: Crossway, 2011), 115.

An Interview with Ray Ortlund on Creating Gospel Culture in the Church

I really enjoyed the opportunity to sit down with Ray Ortlund, lead pastor of Immanuel Church in Nashville, to talk about his book, The Gospel: How the Church Portrays the Beauty of Christ (Crossway, 2014).

I really enjoyed the opportunity to sit down with Ray Ortlund, lead pastor of Immanuel Church in Nashville, to talk about his book, The Gospel: How the Church Portrays the Beauty of Christ (Crossway, 2014).

Ray is a man who loves the gospel and would love to see churches infused with both gospel doctrine and also gospel culture.

You can read more about and from the book here.

The Crossway blog included this helpful outline of timestamps from our conversation:

00:00 – In the book, you talk about “gospel-doctrine” and “gospel-culture.” What do you mean by these terms?

07:03 – You say that gospel-doctrine without gospel-culture equals hypocrisy. What does that look like?

10:10 – You say that gospel-culture without gospel-doctrine equals fragility. What does that look like?

11:32 – You say that gospel-doctrine with gospel-culture equals power. How do we have both of these?

13:51 – Do you agree that, when the Holy Spirit works, there is much personal cost to God’s people?

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers