Justin Taylor's Blog, page 65

October 31, 2015

498 Years Ago Today: An Interview with Carl Trueman on Luther and His 95 Theses

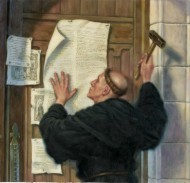

On October 31, 1517—a Saturday—a 33-year-old former monk turned theology professor at the University of Wittenberg walked over to the Castle Church in Wittenberg and nailed a paper of 95 theses to the door, hoping to spark an academic discussion, making the first order of business the proposition that all of life should be marked by repentance. Little did he know that this call for an disputation on repentance would eventually change the course of history through a reformation of the church and the culture.

Below is an interview with Carl Trueman, Paul Woolley Professor of Church History at Westminster Theological Seminary. His Luther on the Christian Life: Cross and Freedom (Crossway, 2015)—with a foreword by renowned Luther scholar Robert Kolb and an afterword by America’s most famous Lutheran historian Martin Marty—is an indispensable resource on appropriating Luther for today.

The town of Wittenberg (c. 1536), a tiny mud-cottage town in east Germany that served as the capital of Electoral Saxony.

A 1522 printed copy of Luther’s 95 theses.

Had Luther ever done this before—nail a set of theses to the Wittenberg door? If so, did previous attempts have any impact?

I am not sure if he had ever nailed up theses before, but he had certainly proposed sets of such for academic debate, which was all he was really doing on October 31, 1517. In fact, in September of that same year, he had led a debate on scholastic theology where he said far more radical things than were in the Ninety-Five Theses. Ironically, this earlier debate, now often considered the first major public adumbration of his later theology, caused no real stir in the church at all.

The door of the Schloßkirche (castle church) in Wittenberg, Germany. The original doors were burned in a bombardment in 1760; the current doors—made of bronze and inscribed with the text of the 95 Theses in the original Latin form—were installed in 1858.

What was the point of nailing something to the Wittenberg door? Was this a common practice?

It was simply a convenient public place to advertise a debate, and not an unusual or uncommon practice. In itself, it was no more radical than putting up an announcement on a public notice board.

What precisely is a “thesis” in this context?

A thesis is simply a statement being brought forward for debate.

Luther was bothered by the use of “indulgences.” What was that?

An indulgence was a piece of paper, a certificate, which guaranteed the purchaser (or the person for whom the indulgence was purchased) that a certain amount of time in purgatory would be remitted as a result of the financial transaction.

A woodcut by Jörg Breu the Elder of Augsburg (c. 1530) showing the sale of indulgences.

At this point did Luther have a problem with indulgences per se, or was he merely critiquing the abuse of indulgences?

This is actually quite a complicated question to answer.

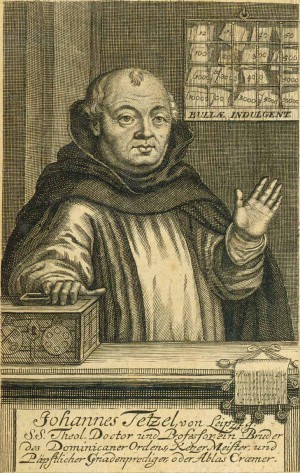

Johann Tetzel (1465-1519), a Roman Catholic German Dominican friar and preacher.

First, Luther was definitely critiquing what he believes to be an abuse of indulgences. For him, an indulgence could have a positive function; the problem with those being sold by Johann Tetzel in 1517 is that remission of sin’s penalty has been radically separated from the actual repentance and humility of the individual receiving the same.

Second, it would appear that the Church herself was not clear on where the boundaries were relative to indulgences, and so Luther’s protest actually provoked the Church into having to reflect upon her practices, to establish what was and was not legitimate practice.

Was Luther trying to start a major debate by nailing these to the door?

The matter was certainly one of pressing pastoral concern for him. Tetzel was not actually allowed to sell his indulgences in Electoral Saxony (the territory where Wittenberg was located) because Frederick the Wise, Luther’s later protector, had his own trade in relics. Many of his parishioners, however, were crossing over into the neighboring territory of Ducal Saxony, where Tetzel was plying his trade.

Luther had been concerned about the matter of indulgences for some time. Thus, earlier in 1517, he had preached on the matter and consulted others for their opinions on the issue. By October, he was forced by the pastoral situation to act.

Having said all that, Luther was certainly not intending to split the church at this point or precipitate the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy into conflict and crisis. He was simply trying to address a deep pastoral concern.

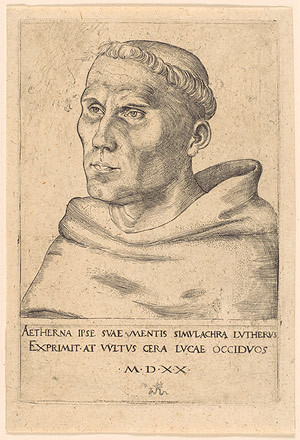

An engraving from 1520 by Luther’s friend, Lucas Cranach, depicting Luther as an Augustinian monk.

Was Luther a “Protestant” at this point? Was he a “Lutheran”?

No, on both counts.

He himself tells us in 1545 that, in 1517, he was a committed Catholic who would have murdered—or at least been willing to see murder committed—in the name of the Pope. There is some typical Luther hyperbole there, but the theology of the Ninety-Five Theses is not particularly radical, and key Lutheran doctrines, such as justification by grace through faith alone, are not yet present. He was an angry Catholic, hoping that, when the Pope heard about Teztel, he would intervene to stop the abuse.

So how did that act of nailing these theses to the door ignite the Reformation?

On one level, I am inclined to say “Goodness only knows.” As a pamphlet of popular revolution, it is, with the exception of the occasional rhetorical flourish, a remarkably dull piece of work which requires a reasonably sound knowledge of late medieval Catholic theology and practice even to understand many of its statements. Nevertheless, it seems to have struck a popular chord, being rapidly translated into German and becoming a bestseller within weeks. The easy answer is, therefore, “By the providence of God”; but, as a historian, I always like to try to tie things down to some set of secondary or more material causes.

The time was right for some kind of protest: anticlericalism, economic strain on all classes of society, and a growing resentment of tax money flowing south to Italy all helped to create an environment in which various groups—peasants, knights, nobility, intellectuals—all saw in Luther’s protest something with which they could sympathize. Yet, even so, the revolutionary power of such a technical composition is, in retrospect, still quite surprising.

So what happened after he nailed the theses to the church door?

Albert of Mainz, painted by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1526)

As to what happened next, well, the debate (ironically) did not. But the theses were translated into German and within weeks were circulating throughout Saxony. They became a popular rallying point of protest, despite the fact that most of the readers would not really have understood them.

Procedurally, Albrecht of Mainz, the bishop responsible for this specific indulgence sale, sent an official complaint to Rome but, in an era of slow communication, this took time to arrive. This bought Luther precious months to continue to develop his theology. The next big event is really the Heidelberg Disputation which took place at a regular chapter meeting of the Augustinian Order in April 1518. It was there that Luther was really able to put his emerging theology on public display.

How important was the printing press in spreading Luther’s reforms?

The printing press is crucial. For the first time in history, news and ideas can be transmitted in a stable form across vast areas of land and throughout populations.

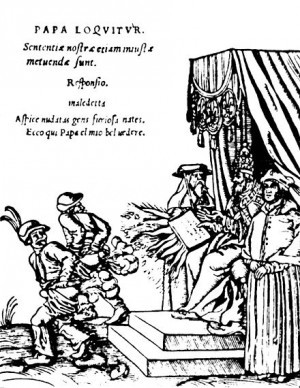

A woodcut by Lucas Cranach commissioned by Martin Luther (1545), depicting the response of German peasants to a papal bull of Pope Paul III.

Of course, most people could not read. But Reformation pamphlets often had graphic (sometimes even pornographic) woodcuts which communicated even to the illiterate who were the good guys and who were the bad. Thus, we have the possibility of mass movements and of the arrival of “popular opinion.”

Cheap print also fueled the rise of literacy, which was to be vital in the spread and establishment of Protestantism in the long term.

For those today who want to read the 95 Theses, what would you recommend?

The place to start is probably Stephen Nichols’s edition (with an introduction and notes).

Nevertheless, if you really want to understand Luther’s theology, and why it is important, you will need to look beyond the Ninety-Five Theses. Probably the best place to start would be Robert Kolb and Charles P. Arand, The Genius of Luther’s Theology: A Wittenberg Way of Thinking for the Contemporary Church.

* * *

The following clip is from the movie Luther, starring Joseph Fiennes (2003):

And here is Dr. Trueman talking about his book:

*The painting at the beginning of this post is by Greg Copeland (courtesty of Concordia Publishing House) and can be found in Paul Maier’s excellent book for older kids, Martin Luther: A Man Who Changed the World.

October 30, 2015

An FAQ on Mysticism and the Christian Life

“The Appearance of the Holy Spirit before Saint Teresa of Ávila,” painted by Peter Paul Rubens (1614)

Why is mysticism so hard to define?

Mysticism is a notoriously vague and complex word. One can make it so specific so as to exclude those throughout history who would self-identify as mystics. On the other hand, one can define it so vaguely that virtually nothing is excluded. Scholars have long recognized the challenge of providing provide one umbrella explanation that sufficiently covers at least two millennia of practice. As Evan B. Howard notes, there is no one single definition that covers all of the sufficient and necessary conditions of mysticisms, and no terminological consensus exists among scholars. This does not mean, however, that nothing useful may be said.

Is there a good working definition?

Philosopher Winfried Corduan provides a very general definition that encompasses a wide variety of mystical understandings. Mysticism, he writes, seeks:

an immediate link with the Absolute.

Corduan notes that presupposed in such an understanding is that

such an Absolute exists,

the Absolute is distinct from the phenomenal word,

a connection with the Absolute is possible, and

the connection between the seeker and the Absolute can be direct and unmediated.

This definition would apply to Christian mystics as well as to Eastern religions (such as Hinduism) that have a strong mystical strain.

What is Christian mysticism?

D. D. Martin offers a good working definition of the key elements involved in such practice:

Christian mysticism seeks to describe an experienced, direct, nonabstract, unmediated, loving knowledge of God, a knowing or seeing so direct as to be called union with God.

Each aspect of this definition is crucial, which can be shown by pointing out what Christian Mysticism is refuting or reacting against.

First, the encounter with the divine Absolute is experiential, not merely notional. The goal is participation with God, not merely acquiring additional knowledge about him.

Second, the encounter is direct, not indirect. The goal is not to merely to know more about God, but to know God himself.

Third, the knowledge sought is nonabstract: to learn or see something that is not vague or symbolic but something particular, concrete, and real.

Fourth, the encounter or knowledge is to be unmediated. Yes, Scripture and Christ may play a role, but the point is to be united to God himself with no intermediaries—no distance and no distractions.

Finally, the goal of all of this knowledge is love. When the Apostle Paul wrote about knowing fully, even as he has been fully known, it was in the context of the enduring eternality and priority of love (1 Cor 13:12).

What are some historical examples of Christian mysticism?

Because of the terminological vagueness associated with Christian Mysticism, a wide variety of historical precedents may be seen throughout church history.

Origen introduced the notion of “mystical interpretation” by seeking to uncover the hermeneutical principles of spiritual interpretation. Paul had written that “the mystery” (Gk. mysterion) was made known to him by “revelation,” and Origen wanted to recover these deeper or hidden meanings, which were distinct from the literal or plain meanings.

Maximus the Confessor later developed a “mystical theology,” with a stress upon the process whereby a Christian comes to participate or join in the fellowship of the life of the Triune God.

So depending upon how they define their terms, figures like Augustine and Aquinas, Wesley and Edwards, have all been categorized as holding to some form of mystical theology and practicing some form of mystical experience. But including these figures likely expands the term so far that very few would be excluded. On the best definitions of mysticism (see D. D. Martin above), key mystics—or advocates of mystical theology and experience—would include figures from the fourth to eighteenth centuries such as Gregory of Nyssa, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, John Ruysboreck, the anonymous author of The Cloud of Unknowing, Julian of Norwich, Therese of Lisieux, Thomas a Kempis, Teresa of Avila, St. John of the Cross, Francois de Sales, Madame Guyon, Francois Felenon, George Fox (founder of the Quakers, or Friends), John Woolman, and the Schwenkfelders (a radical Puritan sect founded in the 1730s).

Some key advocates in the twentieth century would include Thomas Merton, Henri Nouwen, Brennan Manning, and Richard Foster—the latter of which has done more than perhaps any other contemporary author to introduce and commend the attractiveness of mysticism to evangelicals. There are other examples, like A. W. Tozer, who practiced a form of Protestant mysticism, though in more restrained manner than his Catholic and Quaker counterparts.

What is the mystical way?

This was developed by the most radical of the Mystics: the sixteenth-century writers Teresa of Avila (The Interior Castle) and St. John of the Cross (The Dark Night of the Soul).

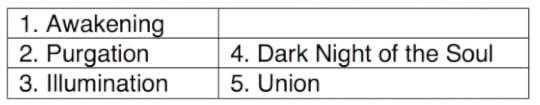

A lot of times you’ll read that their “mystical way” is a three-fold path to uniting with the divine:

awakening,

purgation, and

illumination.

But this is incomplete. That’s only the first part of the mystical way—the path that many achieve, but which is ultimately insufficient if one is seeking true union with God. To arrive at this rarefied destination, one must go through the further state of the dark night of the soul.

What are all the various stages or states the mystic can go through?

First, the mystic experiences an awakening. Psychologically, this is akin to a conversion. He or she comes alive, sensing and seeing (as if for the first time) the attractiveness and reality of Divine Reality. This is not an action per se but an increased awareness, which often arrives suddenly with overwhelming joy and anticipation.

Second, the mystic is met with the contradiction in his life between this awakened or heightened spiritual consciousness combined with his own attachment to material things (earthly things, the things that are below; cf. Col. 3:2b) and his own desires that work against the desires for Divine Reality. These elements of attachment must be purged through self-discipline and mortification (the misdeeds of the flesh must be put to death; cf. Rom. 8:13b).

Third, this leads to the transcendent state of joy whereby the mystic’s soul is illuminated. He or she has been awakened and their sinful desires have been purged, so now they are able to see divine reality in a new light. This is the step of the mystical ladder most often associated with visions, reports of ecstasy, and ineffable delight. But this is where most mystics stop.

Fourth, those who have mastered the previous steps come to realize that even the joys of illumination are bound up with self, and a further purging or emptying must take place. Whereas many popular-level interpreters associate the dark night of the soul with a period of seeming absence from God or a struggle with spiritual depression, in reality John was identifying here a deep and dark experience where even the joy of being in the presence of God must be mortified and purged as being bound up the ego. In his conception, the person must die not only to the sinful self (step 2), but also to self altogether.

Then, and only then, fifth, will the mystic experience a true and indescribable transformative encounter and participation with the absolute, as the self is absorbed into the Divine through the final process of union where the two become one.

The five steps of this ascent of the soul could be schematized as follows, where the awakening is a perquisite for the purgation and illumination, and where the dark night of the soul and the union are further corresponding elements of removal and renunciation followed by the ineffable presence of God:

Biblical spirituality can be defined as the grace-motivated, fruit-bearing pursuit of the triune God—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—in accordance with his own self-revelation. Eternal life is life with this God, and this life only comes through the mediatorial work of the incarnate, crucified, risen, and reigning Son, who said, “I am the way, and the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me” (John 14:6). Likewise, his “Helper,” the “Spirit of truth,” bears witness to the Christ (John 15:26) and teaches and reminds us all that the Son taught on earth (John 14:26)How would you define the biblical vision of spirituality?

What are the goals of biblical spirituality?

The goal of biblical spirituality is the goal of the Christian life: to glorify this triune God by enjoying fellowship with and knowledge of God through godly conformity to his image and character. Each aspect of this goal is elucidated for us in God’s Word. We are to do everything—even the routine and mundane things like eating and drinking—“for the glory of God” (1 Cor. 10:31). We do this because there is “surpassing worth” in knowing our Lord and our Savior (Phil. 3:8, 10). The whole point of Christ’s work on the cross was so that “that he might bring us to God” (1 Pet 3:18). God’s will for us is our “sanctification” (1 Thess. 4:3), and that means that we must “train [ourselves] for godliness” (1 Tim 4:7). As we do, we are working in according with God’s predestined plan that we will ultimately be “conformed to the image of his Son” (Rom. 8:29).

What are the means of biblical spirituality?

Toward this end, we are to engage in spiritual practices, means of grace, which are divine gifts that we are to be actively engaged in as we pursue fellowship with God for the glory of God in conformity with the image and character of God. These means are both personal (like prayer in our prayer closets) and corporate (like prayer in our congregations), and involve activities that are done only once (like baptism), that are done regularly (like the Lord’s Supper), and that are to be in some ways practiced continually (like prayerful meditation; cf. 1 Thess. 5:17; Josh. 1:8).

How do we know if a spirituality is truly “biblical”?

Essential to the practice of biblical spirituality is that the practices and theology behind them must be genuinely biblical. This observation creates an immediate conundrum, however, for all theologies and practices that claim the name of Christ also claim the mantel of biblical sanction. But there is a difference between practices that arise from the very text of Scripture and those that are not ostensibly permitted by it. The Apostle Paul commands us to “test everything; hold fast what is good” (1 Thess. 5:21), and the ultimate test is the clear, authoritative, sufficiency, and necessary word of God. Jesus prayed to his Father that we might be sanctified in the truth, adding in his prayer to the Father that “your word is truth” (John 17:7). Jesus indicated the indispensability of the Word when he quoted Deuteronomy to the effect that “Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of God” (Matt. 4:4). The author of the book of Hebrews highlights the active essential role of Scripture in forming our spiritual lives and combating sin: “the word of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged word, piercing to the division of soul and of spirit, of joints and of marrow, and discerning the thoughts and intentions of the heart” (Heb. 4:13).

What is required of a person to practice biblical spirituality?

What I’ve said so far could leave a false impression if the practice of spiritual disciplines and the training for godliness are divorced from the very shape or structure of the Christian life, for according to the Bible, the very act of “spiritual” activity can only be done by those who have the Spirit and those who do not. In the New Covenant there is a profound demarcation between those who have been “born again” and those who have not (cf. John 3:3ff). “The natural person,” according to Paul, does not accept the things of the Spirit of God” whereas the “spiritual person” has “the mind of Christ” (1 Cor. 2:14-16). But in the New Covenant, all begin in the same position, having fallen short of the glory of God (Rom. 3:23), such that there is not even one that is righteous (Rom. 3:10ff). Because of the sin and death that came through the one man Adam (Rom. 5:12ff), we are all in need of divine grace, and all in need of the covenant righteousness achieved by a new and perfect high priest and covenant representative. In the great exchange Christ takes upon himself our unrighteousness and graciously gives to us his own righteousness (2 Cor. 5:21). We receive this note by works or physical inheritance or national identity but by grace through faith (Rom. 5:1; Eph. 2:8-9). Then, having been fully accepted and adopted as God’s own and filled with his presence, we are to walk in the works he has eternally ordained for us (Eph. 2:10). In union with the crucified and risen Christ, we become what we are, being actually transformed into the legal reality we have as justified saints (Rom. 6:1-11), such that sin becomes an unthinkable and contradictory reality in our lives (Rom. 6:12-23). This sanctifying work continues and culminates in our glorification, such that when he appears on that final day, “we shall be like him, because we shall see him as he is” (1 John 3:2).

What are some similarities between Christian mysticism and biblical spirituality?

For those who find Christian Mysticism deficient, it would be tempting to identify only the ways in which it falls short. But we must reckon with the fact that very few distortions of truth are complete distortions. If they were, no genuine Christian would find attractive elements to them. There are several positive elements of overlap between Christian Mysticism and the biblical witness.

First, Christian Mystics are committed theologically to Trinitarianism. In an age where Christian sects (such as the Mormons or the Jehovah’s Witnesses) seek to revive forms of Arianism and polytheism, it is important for us to recognize the salutary commitment of those in the Catholic, Quaker, and Orthodox traditions who maintain a belief in the Triune God, with a ruling and sending Father, a redemption-accomplishing Son, and a redemption-applying Spirit.

Second, Christian Mystics understand that God is both transcendent and immanent. Though we may critique the balance in their theology, they believe that God has authority over all things as the transcendent Lord and that he is covenantally present with his people. Both poles of the divine life must be present in their theology for the presupposition to make sense that they can seek an intimate encounter with and union with a loving and ineffable God.

Third, the Christian Mystic recognizes that seeing God is the summa bonum, the highest good. All of us long for the day when we shall see God as he is (1 John 3:2), when we shall see him face to face rather than in a mirror dimly, to know him fully rather to partly, to know him even as we are known (1 Cor. 13:12). The Christian Mystic is not content to wait for this in the future but commendably desires to experience the fullness of God (Eph. 3:19) and the eternal depth and duration joy of his presence now (Ps. 16:11). The Christian Mystic rightly desires to experience union with God and to become a “partake of the divine nature” (2 Pet. 1:4). No one can fault him for relentlessly pursuing the great good in all the earth.

Fourth, the Christian Mystic understands the necessity of personal and private encounters with God as an essential aspect of the Christian life. Even though their understanding and practice of this is subject to criticism (see below) we can charitably recognize that they take Jesus’s command seriously to “go into your room and shut the door and pray to your Father who is in secret,” and they believe the resulting promise: “your Father who is in secret will reward you” (Matt. 6:6).

Fifth, the Christian Mystic understands the great emphasis upon the heart. It is possible for us to have notitia (knowledge) and assensus (assent) without fiducia (trust). We may have great thoughts of God and believe great things about him, but if we still we be spiritually deficient unless and until we move toward him in whole-souled trust—seeking to love him with every aspect of our being, with all of our mind, soul, strength, and heart.

Sixth, related to the above, the Christian Mystic understands that an encounter with God has mysterious elements to it that defy rational analysis or categorization. He delights in that which cannot be fully comprehended, marveling at God’s “unsearchable riches” (Eph. 3:8) and God’s love that “surpasses knowledge” (Eph. 3:19) and God’s ways that are “inscrutable” (Rom. 11:33). The Christian Mystic rejoices that no one can fully know the mind of the Lord (Rom. 11:34).

Finally, the Christian Mystic understands that an encounter with God cannot be self-generated. There is nothing automatic about a link, union, or participation with God. There is effort and labor involved. The Christian Mystic, even if he or she is deficient in his application, rightly sees that they must first be awakened to divine reality. They see that they must put to death or mortify all that is contrary to God and his will. They seek the joy of illumination, all for the end that they might know and be with God—even at great sacrifice to their own time, talent, and treasure.

Considered in this light, there are many commendable aspects of Christian Mysticism, especially at the aspirational level. Unfortunately, there are also serious deficiencies in practice and theology that mean Christian Mystics fall short of the biblical picture of spirituality.

What are some d ifferences between Christian mysticism and biblical spirituality?

First, Christian Mystics tend to have an optimistic understanding of human nature. As noted above, they do not believe that mystical experiences can be self-generated, and hence it would be incorrect to label them Pelagian. But it would not be inappropriate to suggest that many of them were semi-Pelagian, or at least practiced spirituality in such a way that would lead one to this conclusion. For some, this is more explicit than for others (note George Fox’s notion that all of us are born with a divine “spark”). If all of us have a principle of grace or a ray of divine light residing within us, no matter our eternal spiritual condition, it follows that the ultimate difference between those who progress toward illumination and on to union are those with whom the human will has made a self-determination. The biblical view, to the contrary, is that all of us were “dead in the trespasses and sin in which you once walked . . . we all once lived in the passions of our flesh, carrying out the desires of the body and of the mind and were by nature children of wrath, like the rest of mankind.” Paul proceeds immediately to reveal the difference between those who remain in this state and those who change: “But God, being rich in mercy, because of the great love with which he loved us, even when we were dead in our trespasses, made us alive together with Christ—by grace you have been saved—and raised us up with him and seated us with him in the heavenly places in Christ Jesus, so that in the coming ages he might show the immeasurable riches of his kindness toward us in Christ Jesus” (Eph. 2:1-7).

Second, there is another deficient element to the Christian Mystic’s anthropology: he does not fully recognize the healthy and holistic way in which God has created us. The Christian mystic tends to rend asunder what God has joined: doctrine and devotion, head and heart. Because the mystical experience is not open to falsification, external examination, or even rational analysis, the role of the “heart” must be elevated above the “mind.” In fact, part of the purgation process is to rid oneself of one’s thoughts that could supplying distracting data that would prevent a divine encounter. Whereas the biblical model is to fill our hearts and mind with the great and precious promises of God (2 Pet. 1:4)—meditating on his Word day and night (Josh. 1:8), such that it is compared to our daily, sustaining bread (Matt. 4:4)—the Christian Mystic seeks to not only purge himself of all that is sinful and encumbering (stage 2) but ultimately wants to purge himself of even his delights in the character and presence of God (stage 4). This is deeply and manifestly unbiblical.

Third, despite what they might profess, the Christian Mystic’s actions tend to undermine the necessity of grace. Biblically, there is grace to forgive and there is grace to empower. We are saved by grace (Eph. 2:8-9), and yet Paul also regularly imparts a benediction of “grace and peace” to his readers. Paul is livid with the false teaching in Galatia that suggests that we start with grace and then move on to works as the means of spiritual sustenance, incredulously asking, “Are you so foolish? Having begun by the Spirit, are you now being perfected by the flesh?” (Gal. 3:3). The Christian Mystic often gives the impression that God might begin the process but it is up to us to find the right formula or set of rules to experience a deep and mystical encounter with him. Whereas the Christian Mystic is content to speak about the ascent and descent of the human soul in its question for a divine encounter, God tells us in his word that we are not to say in our hearts, “‘Who will ascend into heaven?’ (that is, to bring Christ down) or ‘Who will descend into the abyss?’ (that is, to bring Christ up from the dead). Rather, it says: “The word is near you, in your mouth and in your heart (that is, the word of faith that we proclaim); because, if you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved” (Rom. 10:6-10).

Fourth, the previous point flow is bound up with the Christian Mystics’ downplaying of the legal and forensic aspects of divine salvation. The work of Christ on the cross not only wipes our slates clean, but it also provides us with full, legal righteousness in the sight of God. We are not merely put back into the pre-probationary garden, where Adam was sinless but with the potential to fall; rather, we are united to Christ and adopted as his young brothers and as sons of the Most High. Everything he has, we have. Our salvation is secure not because of our works but because of his work. The Christian Mystic seems to view Christ mainly as our example, with the danger of Christ as our savior at times downplayed—and usually with Christ as substitute almost completely obscured. Only in so far as we realize that we are possessed by Christ and fully accepted by our Father can we be freed to walk with him in love, without servile fear. In so doing, our relationship to God is more like living with a loving Father whom we aim to please than it is like working for a boss whom it is difficult to visit with and where one’s job is always on the line.

Fifth, the Christian Mystic confuses the biblical order of union with Christ and communion with God. All who are spiritual—that is, all who are born again and made alive with God—are united with him. There are not some Christians who are united and some who are not. It is part of a package deal. With the legal and relational reality of union with Christ, we have communion—fellowship, participation—with the triune God. Whereas our union with Christ is immovable and secure, our communion with God can have ups and downs. There can be moments of greater and lesser closeness and relationship as we repent and return to the Lord again and again. The Christian Mystic conflates these two aspects of the divine-human relationship because he has such a small category for the forensic reality, and thus he is—in a sense—seeking that which he could already obtain from a childlike trust in his substitute and savior, and runs the serious risk of perpetuating self-righteousness in seeking to work for that which could be his as a gift. Another way of describing this is that the Christian Mystic has an under-realized soteriology.

Sixth, combined with the Christian Mystic’s under-realized soteriology, there is an over-realized eschatology. As mentioned above, we are united to Christ and seated in the heavenly places (Eph. 2:7). Those in Christ have already died and our life is “hidden with Christ in God.” What the Christian Mystic seems to fail to recognize is that when Christ returns, the—and only then—will we “appear with him in glory” (Col. 3:3-4). The Christian Mystic is seeking for something good—to be in the full and final presence of God without sin or stain and to be ultimately absorbed into the life of the Trinity—but he is seeking it at the wrong time. Our focus should be on communing with God through the means of grace, through individual discipline and corporate worship, seeking to know him more and more as we love God with all that we are and seek to love our neighbors as ourselves.

Seventh, the Christian Mystic makes a fundamental misstep in seeking to have a direct and immediate experience of God that is unmediated. At first glance, this desire can be seen as commendable. Should we not want to experience the presence of the Lord apart from any barriers or intermediaries or encumbrances? The biblical answer is that we should want to experience God in the way that he has ordained. First, we return once again to the issue of the work of Christ, who was sent by the Father to have a mediatorial role. He did not come as only a teacher or as a great example, but as our substitute savior, the lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world (John 1:29), the “one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus, who gave himself as a ransom for all” (1 Tim. 2:5-6). The only way to the Father is through him (John 14:6), and the Spirit and the Son combine to intercede for us before the Father and interpret our inarticulate prayers (cf. Rom. 8:27). Secondly, returning to the idea of an over-realized eschatology, we must recognized that on this side of the new heavens and the new earth, God “has spoken to us by his Son” (Heb. 1:2), and we have access to his Son through his written Word. So the Word of God must be an irreducibly central role in both our communication to, and our communication from, the living God. To seek to separate God from his word, and Christ from his work, are unthinkable unrealities. And to bypass both of these mediatorial aspects of divine communication is a grave mistake that opens the door to that which contradicts the word of God.

Eighth, though not all Christian Mystics have the exact same presuppositions regarding the corporate nature of fellowship, there is a troubling tendency in the tradition to practice spiritual isolationism. We noted earlier in this essay that the Christian Mystic rightly obeys Jesus’s command that there are times when we must get alone in our prayer closets to pray in secret to our Father who is in secret. But the Christian Mystic sees the height of spiritual achievement as involved the mystical process of purging all distractions and individually seeking a communion with God. Even many Mystics who have sought to live in community have done so in a way that is isolated from society at large. What seems to be a noble quest for God, involving a renunciation of earthly pleasures (from marital love to clothing that does not scratch) is not held forth in the Bible as the ideal of godliness. We are to be eager to gather with the saints in order to stir one another up to love and good works, to encourage and meet with one another instead of neglecting each other. The idea of full-time Christians withdrawing from society and banding together may seem more spiritual, but it is not biblical. Spiritual growth takes place not only in the prayer closet, but in corporate worship as the people of God gather together to hear the Word of God read, and the Word of God proclaimed, and the Word of God sung.

Ninth, the Christian Mystic may be critiqued for having an incipient Gnosticism in his theology and practice. While biblical spirituality would certainly encourage every professing believer to purge himself of sinful thoughts and behavior, the Christian Mystic tends to go beyond this. The body, and the things of this world, are frequently regarded as competitors with God rather than gifts from God to be utilized and enjoyed. When Paul tells us to “set our minds on things that are above, not on things that are on earth” (Col. 3:2), he does not have in mind a fundamental spiritual-material duality. This is seen by his explanation of those earthly things we must shun just a few verses later: “Put to death therefore what is earthly in you: sexual immorality, impurity, passion, evil desire, and covetousness, which is idolatry. . . .anger, wrath, malice, slander, and obscene talk from your mouth” (vv. 5, 8). These are contrasted with “compassionate hearts, kindness, humility, meekness, and patience” (v. 12). The Christian Mystic must seriously reckon with Paul’s association of deceitful spirits and demonic teaching with the forbidding of things like marriage and foods under the guise of godliness (1 Tim. 4:1). Instead, Paul says, “everything created by God is good, and nothing is to be rejected if it is received with thanksgiving, for it is made holy by the word of God and prayer” (1 Tim. 4:4). If the Christian Mystic insists that some of God’s created goods must be purged, and that even his enjoyment of God’s very presence must be put away in the dark night of the soul in order to achieve union with God, then he is walking in contradiction to the very way and will of God.

Finally, although this has been touched on before in various ways, we may note again the crucial place that Scripture should play in our understanding of and practice of biblical spirituality. A bedrock principle of spirituality that is biblical is that Scripture itself plays an essential, norming role. God has spoken, and he is not silent (to use Francis Schaeffer’s memorable terminology). His word is clear, not obscure. His word is authoritative, not just advisory. His word is necessary, not optional. And his word is sufficient, not just helpful. The Apostle Paul proclaimed that “All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work” (2 Tim. 3:16-17). At the end of the day, this is one of the clearest contrasts between Christian Mysticism and biblical spirituality. In the former, spiritual quests are made that are not informed and constrained by God’s self-revelation in holy Scripture. If we want our spirituality to be biblical, Scripture must be our norming norm.

For some further definitions of and interactions with Christian Mysticism that have informed my perspective, see:

D.D. Martin, “Mysticism,” in Walter A. Elwell, ed., Evangelical Dictionary of Theology (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1984), 744.

Winfried Corduan, Mysticism: An Evangelical Option? (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1991; reprint: Wipf & Stock).

Arthur L. Johnson, Faith Misguided: Exposing the Dangers of Mysticism (Chicago: Moody, 1988).

Donald S. Whitney, “Doctrine and Devotion: A Reunion Devoutly to Be Desired“

October 29, 2015

19 Turning Points in the History of Philosophy and Theology

The following is adapted from John Frame’s A History of Western Philosophy and Theology (P&R, 2015).

AD 33

Jesus is crucified and resurrected. The incarnation of God in Jesus Christ establishes the truth of the Christian worldview and fulfills the history in which redemption from sin and death forms the core of the Christian gospel.

165

165

Justin, of the first generation of Christian philosophers and apologists, dies as a martyr to his faith.

313

313

Roman Emperor Constantine issues the Edict of Milan, which ends empire-wide persecution of Christianity. In 325 he convened the first ecumenical council of the church at Nicaea, which affirmed the deity of Jesus Christ.

354-430

354-430

Augustine’s writings culminate the theological and philosophical achievement of the patristic era and mark the beginning of the medieval, in which the church takes over from the Roman Empire the dominant role in philosophy and the preservation of ancient thought.

1274

1274

Thomas Aquinas’s Summa Theologiae combines Platonic, Aristotelian, and biblical elements to form the classical medieval synthesis of faith and reason. Aquinas relegates the Greek form-matter scheme to the realm of natural knowledge, and then adds a higher level in which faith and revelation supplement reason.

1517

1517

Martin Luther attaches Ninety-five Theses to the church door in Wittenberg, marking the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. Philosophically, the Reformation renounces the autonomy of reason (including Aquinas’s “natural reason”) and seeks to govern its thought by God’s written Word

1624

1624

Edward, Lord Herbert of Cherbury enumerates fine points of natural religion in De Veritate, which marks the beginning of English deism and the liberal tradition in theology. The liberal tradition renounces biblical authority and seeks knowledge in ways that follow the autonomous pretensions of secular thought.

1637

1637

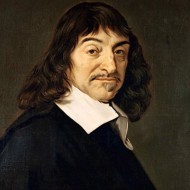

René Descartes’ Discourse on Method introduces a radically secular turn in philosophy, similar to the beginning of the discipline in 600 BC. As Thales set aside all tradition and religion to think by reason alone, so Descartes sets aside everything he considers doubtful, including Scripture and Christian tradition.

1781

1781

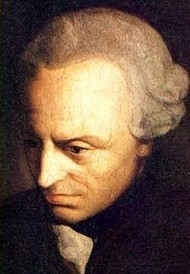

Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason creates a “Copernican revolution” in epistemology, in which the forms of experience are imposed on the world, not by God, but by the human mind. Thus Kant establishes human autonomy far more firmly as the fundamental authority for philosophy and theology. In Religion within the Limits of Reason Alone, Kant draws out the theological implications of this change, transforming the Christian gospel into an autonomous ethic. In Kant, the human mind essentially replaces God.

1807

1807

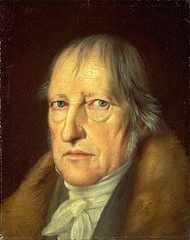

Georg W. F. Hegel publishes his Phenomenology of the Spirit, which renews the rationalist tradition after Kant’s critique, but continues Kant’s program of identifying God with the human mind.

1848

1848

Karl Marx publishes his Communist Manifesto, which converts Hegel’s neo-rationalism into a political ideology. Marx calls the proletarian working class to unite in a revolution to overthrow the capitalist bourgeoisie in order to establish a classless society.

1880

1880

Abraham Kuyper, in his inaugural address as a professor at the Free University of Amsterdam, announces that there is not one square inch of territory over which Jesus Christ does not say, “Mine!” Kuyper’s work begins a new era, in which Christians no longer seek to validate their work by secular models, but rather to assert forcefully the distinctive worldview of the biblical revelation.

1900

1900

Albrecht Ritschl publishes The Christian Doctrine of Justification and Reconciliation, developing Kant’s moralism into a theological movement with great influence in the churches.

1919

1919

Karl Barth publishes The Epistle to the Romans, which fell “like a bombshell in the playground of the theologians” and proved the end of Ritschlianism. But in many ways, Barth’s work was another synthesis with secular thought.

1921

1921

Ludwig Wittgenstein publishes his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, launching the method of solving all philosophical disputes by examination of language. But at the end of the book, he recognizes that his project is self-refuting.

1927

1927

Martin Heidegger publishes Being and Time, which (with the writings of Jean-Paul Sartre and others) seeks to reconstitute philosophy on a consistently atheistic basis.

1955

Cornelius Van Til publishes The Defense of the Faith, which seeks to establish philosophy and Christian apologetics on a distinctively biblical epistemology.

Cornelius Van Til publishes The Defense of the Faith, which seeks to establish philosophy and Christian apologetics on a distinctively biblical epistemology.

1967

1967

Alvin Plantinga publishes God and Other Minds, beginning a new era of professional acceptance for Christian philosophers.

The Last Judgment

Jesus Christ returns on the clouds with power and glory to judge the living and the dead, to vindicate his disciples, and to turn over his kingdom to his Father in the Holy Spirit. His appearance settles all arguments as to the truth of divine revelation and begins a new era of faithful human philosophic exploration.

Taken from The History of Western Philosophy and Theology by John M Frame (ISBN 978-1-62995-084-6), appendix pages 871-875, used with permission of P&R Publishing Co. P O Box 817, Phillipsburg, N.J. 08865 www.prpbooks.com

October 28, 2015

3 Reasons Those Who Are Unbiblically Remarried After a Divorce Should Not Leave Their New Spouse

The official catechism for the Roman Catholic Church forbids that Eucharistic communion be given to those who have divorced and remarried and are living in this second marriage as man and wife:

In fidelity to the words of Jesus Christ—“Whoever divorces his wife and marries another, commits adultery against her; and if she divorces her husband and marries another, she commits adultery”—the Church maintains that a new union cannot be recognized as valid, if the first marriage was. If the divorced are remarried civilly, they find themselves in a situation that objectively contravenes God’s law. Consequently, they cannot receive Eucharistic communion as long as this situation persists. For the same reason, they cannot exercise certain ecclesial responsibilities. Reconciliation through the sacrament of Penance can be granted only to those who have repented for having violated the sign of the covenant and of fidelity to Christ, and who are committed to living in complete continence.

Toward Christians who live in this situation, and who often keep the faith and desire to bring up their children in a Christian manner, priests and the whole community must manifest an attentive solicitude, so that they do not consider themselves separated from the Church, in whose life they can and must participate as baptized persons:

They should be encouraged to listen to the Word of God, to attend the Sacrifice of the Mass, to persevere in prayer, to contribute to works of charity and to community efforts for justice, to bring up their children in the Christian faith, to cultivate the spirit and practice of penance and thus implore, day by day, God’s grace.

The Catholic Synod of Bishops recently debated this issue, with liberal bishops arguing that exceptions to this rule should be made on a pastoral, case-by-case basis. The synod functions not as a decision-making body within the Church but rather provides the Pope with reflections and counsel through their deliberations and final report. While Pope Francis seems to be with the liberal bishops on this, it’s unclear to me (as an outside Protestant observer) that there will be any change to the Church’s doctrine or practice.

Evangelicals are divided on the question of what exceptions, if any, allow for divorce and then for remarriage. They tend to be united, however, against the Catholic view that a sinful remarriage should also be broken.

In his book This Momentary Marriage: A Parable of Permanence (Wheaton: Crossway, 2009), 170-71, John Piper offers three reasons for this view. I’ve reprinted the relevant section below.

I do not think that a person who remarries against God’s will, and thus commits adultery in this way [Luke 16:18], should later break the second marriage. The marriage should not have been done, but now that it is done, it should not be undone by man. It is a real marriage. Real covenant vows have been made. And that real covenant of marriage may be purified by the blood of Jesus and set apart for God. In other words, I don’t think that a couple who repents and seeks God’s forgiveness and receives his cleansing should think of their lives as ongoing adultery, even though, in the eyes of Jesus, that’s how the relationship started. There are several reasons why I believe this.

1. Deuteronomy 24:4 speaks against going back to a first husband after marrying a second.

First, in Deuteronomy 24:1-4, where the permission for divorce was given in the law of Moses, it speaks of the divorced woman being “defiled” in the second marriage so that it would be an abomination for her to return to her first husband, even if her second husband died. This language of defilement is similar to Jesus’ language of adultery. And yet the second marriage stood. It was defiling in some sense, yet it was valid.

2. Jesus seemed to regard multiple marriages as wrong but real.

Another reason I think remarried couples should stay together is that when Jesus met the woman of Samaria, he said to her, “You have had five husbands, and the one you now have is not your husband” (John 4:18). When Jesus says, “The one you have now is not your husband,” he seems to imply that the other five were. Not that it’s right to divorce and marry five times. But the way Jesus speaks of it sounds as though he saw them as real marriages. Illicit. Adulterous to enter into, but real. Valid.

3. Even vows that should not be made should generally be kept.

The third reason I think remarried couples should stay together is that even vows that should not be made, once they are made, should generally be kept. I don’t want to make that absolute for every conceivable situation, but there are passages in the Bible that speak of vows being made that should not have been made, but they were right to keep (like Joshua’s vow to the Gibeonites in Joshua 9). God puts a very high value on keeping our word, even when it gets us in trouble (“[The godly man] swears to his own hurt and does not change,” Ps. 15:4). In other words, it would have been more in keeping with God’s revealed will not to remarry, but adding the sin of another covenant-breaking does not please God more.

There are marriages in the church I serve that are second marriages for one or both partners, which, in my view, should not have happened, but are today godly marriages—marriages that are clean and holy, and in which forgiven, justified husbands and wives please God by the way they relate to each other. As forgiven, cleansed, Spirit-led followers of Jesus, they are not committing adultery in their marriages. These marriages began as they should not have but have become holy.

October 27, 2015

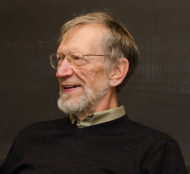

Two Concerns with Thomas Merton’s Vision of the Christian Life

Thomas Merton (1915-1968) was an author, poet, activist, and Trappist monk. His spiritual autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain—named after the mount of purgatory in Dante’s The Divine Comedy (cf. 242)—was completed in 1946 at Gethsemani Abbey in Kentucky. After being edited and redacted by his superiors, it was published in 1948 when Merton was 33 years old, quickly becoming the bestselling non-fiction book of the year and a spiritual classic.

This long and well-written memoir defies easy summation. The narrative is split almost exactly in the middle, narrating his journey prior to embracing Catholicism and after it.

I want to look briefly at two key points of this second half of the book regarding Merton’s vision of living the Christian life.

I want to look briefly at two key points of this second half of the book regarding Merton’s vision of living the Christian life.

First, there is a strange quality—at least to these evangelical ears—to Merton’s conversion account. To be sure, it is clear that Merton is coming to the end of himself, tired of seeking satisfaction in the ways of the world. And it is clear that he has converted to Catholicism. What is less clear is whether he understands the objective work accomplished by Christ on his behalf. His overarching perspective—especially in conjunction with his sacramental understanding of Communion and baptism—is centered on incorporation and participation in the life of God, and recapitulation of the death and suffering of Christ, such that the forensic foundation of the work of Christ is so eclipsed as to be virtually invisible. Without this anchor, it is difficult to ground the Christian story in something more substantial and stable than mere “spirituality.” It cannot be entirely surprising, therefore, to learn that in the years following the publication of his memoir Merton grew increasingly attracted to Zen Buddhism as his monastic resentment grew.

Second, I believe that Merton had a defective understanding of God’s creational gifts and a misunderstanding of the call to bear our cross daily for Christ. He suggests that for a man to enter a religious Order and to serve in his vocation fruitfully, “it must cost him something, and must be a real sacrifice. It must be a cross, a true renunciation of natural goods, even of the highest natural goods” (319). It is true that Christ teaches self-denial and cross-bearing (Luke 9:23), but this is something required of all believers, not just a special few called to a set-apart life. It is not self-denial according to communal rules, but denial of worldly pleasures. It is not the rejection of natural goods, but the embracing of the Giver and all the good that he gives in Christ. The monastic version of the contemplative life embraced and advocated by Merton is difficult to square with Paul’s strong argument against asceticism in 1 Timothy 4:1-5. He speaks of the demonic deceit and conscience-seared insincerity of those

who forbid marriage and require abstinence from foods that God created to be received with thanksgiving by those who believe and know the truth. For everything created by God is good, and nothing is to be rejected if it is received with thanksgiving, for it is made holy by the word of God and prayer.

At one point Merton says that he desires solitude, “to be lost to all created things, to die to them and to the knowledge of them, for they remind me of my distance from You” (461). But the perspective of C. S. Lewis is much more biblically faithful:

Creation seems to be delegation through and through. [God] will do nothing simply of Himself which can be done by creatures. I suppose this is because He is a giver. And He has nothing to give but Himself. And to give Himself is to do His deeds—in a sense, and on varying levels to be Himself—through the things He has made. (my emphasis)

By failing to ground his understanding of the gospel in the forensic work of Christ on our behalf, and by downplaying the gifts of the Giver as a means of communing with him, Merton provides an unstable framework for living the Christian life as it is set forth in the Bible. There may be valuable things to glean from Merton’s story and prescriptions, but much of it is surely cautionary and should be read discerningly.

What Is the Relationship between Christianity and Words?

We think, hear, speak, sing, write, and read words all day, every day. Our lives are loaded with words.

We think, hear, speak, sing, write, and read words all day, every day. Our lives are loaded with words.

So what do words have to do with Christianity?

Almost everything.

At every stage in redemptive history—from the time before time, to God’s creation, to man’s fall, to Christ’s redemption, and to the coming consummation—“God is there and he is not silent” [Francis Schaeffer].

God’s words decisively create, confront, convict, correct, and comfort. By his words he both interprets and instructs.

If you wanted to construct a biblical theology of words, you could get pretty far in just the first few pages of your Bible.

God’s Original Words

The early chapters of Genesis are replete with God using words to create and order, name and interpret, bless and curse, instruct and warn.

God commands (“And God said, ‘Let there be . . . ‘”), and reality results (“and there was. . . .” “And it was so”).

God names (“God called . . . “), and things are publicly identified.

We learn later that it is “by the word of his power” that God’s Son, Jesus Christ, continually sustains and “upholds the universe” (Heb. 1:3).

Before God creates man, he first uses words to announce his intention (“Let us make . . . “). And once Adam and Eve are created, their first experience with God involves words, as he gives them the cultural mandate (Be fruitful, multiply, fill the earth, subdue it, have dominion), explains their freedom (“You may . . . “), and warns them against disobeying his command (“You shall not . . . “).

Against God’s Words

When Satan slithers onto the scene as a crafty serpent, his first action is to speak, and his wicked words are designed to call into question the very words of God. The first step is to sow the seed of doubt (“Did God actually say . . . ?”). And the second step is the explicit accusation that the Creator was really a liar (“You will not surely die”).

When Adam and Eve rebel against the only restriction they were given, they express for the first time words that are so common for us today: fear (“I was afraid”), shame (“I hid myself”), and blame (that woman—whom you gave to be with me!).

God then interprets their new fallen world for them—and also gives the first words of the gospel, foretelling the time when he will send his Son to save his people and crush the head of his enemy. God uses words to tell of the coming Word made flesh (John 1).

The Words of the Word

When God’s Son eventually enters into human history as the God-man, he lives by God’s Word (Matt. 4:4), keeps God’s Word (John 8:55), and preaches God’s Word (Mark 2:2).

The Father gave Jesus words, Jesus gave them to his followers, and his followers received them (John 17:8).

Jesus’ words are inseparable from his person and thus can be identified as having divine attributes. [Jesus frequently refers to who he is and what he says as a package deal: “me and my words,” e.g., Mark 8:38; Luke 6:47; John 12:48; 14:24.] To be ashamed of Christ’s words is on the same level as being ashamed of Christ himself (Luke 9:26).

His words are eternal: unlike heaven and earth, Christ’s words will remain forever (Matt. 24:35).

They have power: Jesus could cast out spirits with “a word” (Matt. 8:16); he merely had to “say the word” and someone could be healed (Matt. 8:8).

Jesus’ words are “spirit and life,” “the words of eternal life” (John 6:63, 68).

Jesus’ words dwell or abide in those who are united to Christ and abiding in him (John 8:31; John 15:7;Col. 3:16).

Only those who hear and keep Jesus’ word receive blessing and eternal life (Luke 11:28; John 5:24; 8:47,52).

Those who heard him were “amazed at his words” (Mark 10:24), hanging on every word and marveling at his gracious speech (Luke 19:48; 4:22).

They recognized that his words possessed a unique authority (Luke 4:32).

Worldly Words

But Jesus critiqued those who used the words of their prayers to conceal the hypocrisy of their hearts, heaping up “empty phrases” and wanting to be “heard for their many words” (Matt. 6:7).

He accused them of using their traditions to make “void the word of God” (Matt. 15:6).

His own words found no place in their hearts—some couldn’t bear to hear his words, and some heard his words but refused to keep them (John 8:37, 43; 14:24). In response, Jesus’ enemies “plotted how to entangle him in his talk” (Matt. 22:15).

Jesus warned that how one hears and responds to Jesus’ words reveals the ultimate dividing line within salvation history: on the day of judgment we will each give an account “for every careless word,” being either justified or condemned by our words (Matt. 12:36-37), for “what comes out of the mouth proceeds from the heart” (Matt. 15:18).

If you hear and practice Christ’s words, you are like a wise man building a house on a rock-solid foundation that can remain standing even during a torrential storm. But hearing Christ’s words and failing to do them is like building a house on sand, which will crumble to the ground in the midst of the storm (Matt. 7:24-26).

The Word of the Gospel

In the book of Acts and in the Epistles, the gospel message—

the good and glorious news that

“another true and obedient human being has come on our behalf,

that he has lived for us the kind of life we should live but can’t,

that he has paid fully the penalty we deserve for the life we do live but shouldn’t” [Graeme Goldsworthy],

with all of the personal and kingdom implications that that entails

—is referred to as “the Word.”

As you read God’s Word and consider the deep implications of the gospel for your life, you’ll begin to discern a pattern [with thanks to Tim Keller for this way of framing the issue]:

God has holy standards for how we are to speak words and listen to words.

This side of heaven we will never fully measure up to God’s holy standard regarding the use of our tongue.

Jesus fulfilled what we (along with Adam, Israel, and every prophet, priest, and king) failed to do: his words were perfect words, without sin. By his punishment-bearing, substitutionary death, his words can become our words.

Our day-by-day failure to use our tongue as we ought—for God’s glory and for the good of his people—comes from a functional rejection of Christ the Word.

It is only as we look to Jesus, rejoicing in him and in his atoning provision, that we are freed to walk—and talk—in his way.

How Then Should We Speak?

If God is a God of words, and if Jesus and his gospel are inseparable, then how should we—those who seek to follow him—use our words?

The book of Proverbs is an excellent place to start, giving pithy statements about what godly and ungodly speech looks like. For a sampling, consider these contrasts [with thanks to Vern Poythress for the original chart]:

Proverb

Godly Words

Ungodly Words

10:32

The lips of the righteous know what is acceptable.

The mouth of the wicked [knows] what is perverse.

12:18

The tongue of the wise brings healing.

Rash words are like sword thrusts.

13:1

A wise son hears his father’s instruction.

A scoffer does not listen to rebuke.

13:3

Whoever guards his mouth preserves his life.

He who opens wide his lips comes to ruin.

13:10

With those who take advice is wisdom.

By insolence comes nothing but strife.

13:18

Whoever heeds reproof is honored.

Poverty and disgrace come to him who ignores instruction.

14:3

The lips of the wise will preserve them.

By the mouth of a fool comes a rod for his back.

14:25

A truthful witness saves lives.

One who breathes out lies is deceitful.

15:1

A soft answer turns away wrath.

A harsh word stirs up anger.

Some Pauline Questions to Ask

Here are some Pauline questions we can ask ourselves about the words we are using:

Are these words gracious? (Col. 4:6)

Are these words seasoned with salt? (Col. 4:6)

Are these words corrupting? (Eph. 4:29)

Are thee words building up the church for good? (Eph. 4:29)

Are these words giving grace to those who hear them? (Eph. 4:29)

Are these words fitting and appropriate? (Eph. 4:29)

Are these words true? Are they spoken in love? (Eph. 4:15, 25)

May the Lord help us use our words in accord with the Word of God as we seek to walk with the Word made flesh.

[Adapted from Justin Taylor, “Introduction,” The Power of Words and the Wonder of God, ed. John Piper and Justin Taylor (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2009), 15-18. Used with permission.]

October 26, 2015

What Does Grace Have to Do with Nature? (Or What Is the Relationship between Christ and Culture, or the Bible and Higher Education?)

This lecture from Bruce Ashford, provost, dean of faculty, and professor of theology and culture at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary—delivered in September 2015 at the school—is well worth your time:

Ashford surveys five competing visions of the relationships between “grace” (God’s saving works and word) and “nature” (not only the created order but also the cultural order). Ashford identifies the following relationships with application toward education:

Grace above nature (“bottom-floor education”). Often associated with manualist Thomists. God’s gracious salvation is something that adds to, and fulfills, the natural realm.

Grace against nature (“a plague on the educational house”). Often associated with certain Anabaptists and Pietists. The Fall corrupted the natural world ontologically in such a manner that God’s salvation causes Christians to withdraw from the world and live a Christian life separate from it.

Grace in tension with nature (“pastors and educators as dual ministers of God”). Associated with Luther and some Reformed evangelicals. The natural realm and the realm of grace each have their own integrity, existing alongside of one another.

Nature without grace (“a naked public quad”). Atheistic view.

Grace renews or restores nature (“an educational preview of a coming kingdom”). Associated with Abraham Kuyper, Herman Bavinck and the best way to describe the views of Irenaeus and Augustine. Sin does not have the power to corrupt the natural realm structurally. Instead, it corrupts the natural realm directionally. God’s still-good-structurally creation is misdirected toward false gods and idols. When Christians receive God’s grace in salvation, they are liberated from their idolatry, liberated to shape their cultural activities toward Christ rather than toward false gods and idols. Their cultural activity is redirective.

The good folks at SEBTS came up with a graphic to illustrate the options:

Ashford explains that all of the options—sans number four (nature without grace)—are advocated by various Christian traditions.

He goes on to argues for the fifth view (grace renews nature).

Joseph Sunde provides some notes from Ashford’s argument:

When God created the world, he created it good. He spoke his word, and his word called forth something from nothing, and then it ordered that world. It gave it a certain ordering, and that could be viewed as God’s thesis for the world. This is the way the world ought to be.

But Satan . . . called that into question. He spoke a word against God’s word, and that . . . antithesis remains today operative everywhere, and operative in every human heart, even Christians. . . .

After the fall, the world remains structurally good but directionally bad. . . . The world the way it is ordered remains good. The fact that we have sun and moon and stars and dry land and water and human beings and animals— that’s good. And the fact that we have a certain cultural order is also good. Things like the arts and the sciences and politics and economics. . . . All of these sorts of things we do in this realm remain good in their what-ness. The fact that they exist is good.

These creational and cultural things are not corrupted ontologically; we don’t have to separate from them. But they are bad directionally. Because sin is essentially a redirecting of the heart away from God . . . and because it is religiously rooted and located in the heart, it radiates outward into everything we do. And so we continue to be cultural beings and social beings, but all of our social and cultural doings are corrupted by sin and idolatry. . . .

Grace and nature belong together . . . Christ Jesus’ redemption should transform us in the entirety of our being, and as it redirects our heart from idols toward the one, true living God, it should then change the way we operate in culture. . . . His lordship is as wide creation, and therefore it is as wide as our cultural eyes. . . . Our mission, therefore, the Christian mission is as wide as the entirety of our cultural and social lives, involving both our words and our deeds and our teaching and learning.

Ashford goes on to suggest three questions that should be asked (and answered) when we find ourselves in any sphere of culture:

What is God’s creational design for this realm of culture?

How has it been corrupted and misdirected by sin and idolatry?

In what ways can I help bring redirection to this realm by shaping my activities in light of Christ’s Lordship rather than in submission to idols?

Again, it’s worth watching and listening to the whole thing. For more, see Ashford’s book, Every Square Inch: An Introduction to Cultural Engagement for Christians (Lexham Press, 2015), and my interview about it here.

The Freedom of Getting Over Yourself

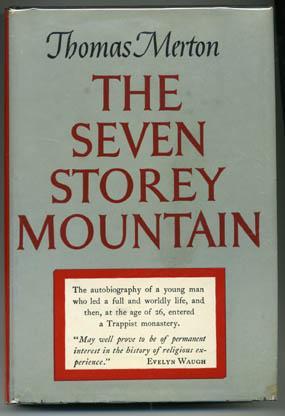

Chesterton:

Chesterton:

How much happier you would be if you only knew that these people cared nothing about you!

How much larger your life would be if your self could become smaller in it; if you could really look at other men with common curiosity and pleasure; if you could see them walking as they are in their sunny selfishness and their virile indifference!

You would begin to be interested in them because they were not interested in you.

You would break out of this tiny and tawdry theater in which your own little plot is always being played, and you would find yourself under a freer sky, in a street full of splendid strangers.

—G. K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy (1908), chapter 2, “The Maniac”

October 22, 2015

“The Most Important Book Ever Written on the Major Figures and Movements in Philosophy”?

That’s what Vern Poythress says about John Frame’s new book, A History of Western Philosophy and Theology (P&R, 2015).

That’s what Vern Poythress says about John Frame’s new book, A History of Western Philosophy and Theology (P&R, 2015).

A lot of people poke fun at book endorsements that bestow superlatives upon the volume being reviewed (“best,” “most important,” etc.).

And yet at the same time, there has to be a best and most important book for each category, right? Maybe Poythress is right and Frame’s is it. If you asked Poythress what makes a book the best in its genre, I think he would say that the best book is the book that works most closely from an explicitly God-centered, biblical worldview. And if that is the criteria, then I would actually have a hard time thinking of a better book than Frame’s for a survey of the major philosophers of western philosophy.

Here’s the blurb I wrote for the book:

Many Christians today mistakenly think of philosophy as an esoteric endeavor irrelevant to Christian theology and discipleship. But Colossians 2:8, among other verses, indicates that we must learn to discern the ways in which human philosophies can be deceitfully empty and captivating. Furthermore, it implies that there is such a thing as “philosophy . . . according to Christ.” In this fascinating survey, John Frame walks us through the history of philosophy to show the varied ways in which both secular philosophies and deficient Christian attempts at philosophy exhibit signs of both irrationalism and rationalism. The result is not only a historical overview of the key players and their philosophers, but also a model for how to integrate philosophy and theology in a way that honors the Lord by taking every thought captive so that we can obey Christ and submit to his lordship (2 Cor. 10:5). Highly recommended!

Here are what others (including Poythress) have written:

John Frame has done it again! In the lucid and comprehensive style of his Theology of Lordship volumes, he here presents a full overview of Western thought about knowledge of God as it must appear to all who receive Holy Scripture, as he does, as the record, product, and present reality of God speaking. And the solid brilliance of the narrative makes it a most effective advocacy for the Kuyper-Van Til perspective that in a well-digested form it represents. It is a further outstanding achievement by John Frame. The book deserves wide use as a textbook, and I hope it will achieve that. My admiration for John’s work grows and grows.

—J. I. Packer, Board of Governors’ Professor of Theology, Regent College, Vancouver, British Columbia

Few in our day champion a vision of God that is as massive, magnificent, and biblical as John Frame’s. For decades, he has given himself to the church, to his students, and to meticulous thinking and the rigorous study of the Bible. He has winsomely, patiently, and persuasively contended for the gospel in the secular philosophical arena, as well as in the thick of the church worship wars and wrestlings with feminism and open theism. He brings together a rare blend of big-picture thinking, levelheaded reflection, biblical fidelity, a love for the gospel and the church, and the ability to write with care and clarity.

—John Piper, Founder and Teacher, desiringGod.org; Chancellor, Bethlehem College and Seminary, Minneapolis

When I was a young man, I plowed through Bertrand Russell’s 1945 classic, A History of Western Philosophy. A couple of years ago I read the much shorter (and more interesting) work of Luc Ferry, A Brief History of Thought. Between these two I have become familiar with many histories of Western thought, each written out of deep commitments, some acknowledged, some not. But I have never read a history of Western thought quite like John Frame’s. Professor Frame unabashedly tries to think through sources and movements out of the framework (bad pun intended) of deep-seated Christian commitments, and invites his readers to do the same. These commitments, combined with the format of a seminary or college textbook, will make this work invaluable to students and pastors who tire of ostensible neutrality that is no more neutral than the next volume. Agree or disagree with some of his arguments, but John Frame will teach you how to think in theological and philosophical categories.

—D. A. Carson, Research Professor of New Testament, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School

This is the most important book ever written on the major figures and movements in philosophy. We have needed a sound guide, and this is it. Philosophy has many ideas and systems that are attractive but poisonous. Over the centuries people have fallen victim again and again. Frame sorts out the good and the bad with clarity and skill, using the plumb line of Scripture. Along the way he also provides a devastating critique of liberal theologies, showing that at bottom they are philosophies of human autonomy masquerading as forms of Christianity.

—Vern S. Poythress, Professor of New Testament Interpretation, Westminster Theological Seminary; Editor, Westminster Theological Journal

Here’s the broad table of contents:

Philosophy and the Bible

Greek Philosophy

Early Christian Philosophy

Medieval Philosophy

Early Modern Thought

Theology in the Enlightenment

Kant and his Successors

Nineteenth Century Theology

Nietzsche, Pragmatism, Phenomenology, and Existentialism

Twentieth Century Liberal Theology, Part 1

Twentieth Century Liberal Theology, Part 2

Twentieth Century Language Philosophy

Recent Christian Philosophy Appendices Appendix A: “Certainty,”

At the end of the book are 20 appendices (half reviews, half articles), an indexed glossary, and an annotated bibliography.

How to Run a Bookstore to the Glory of God and for the Good of the Church

I love the vision of Chun Lai, Ben Dahlvang, and the brothers at Westminster Bookstore in Philadelphia. As an affiliate partner with them for the past several (I receive a small percentage for resources purchased through my blog), I’ve been able to witness their faithfulness both in terms of how they serve the public and in how they serve authors and publishers behind the scenes. It is refreshing to see a bookstore run so well, with service as a hallmark and theological fidelity as a cornerstone.

Here is a short video introduction that captures the heartbeat behind this faithful ministry:

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers