Justin Taylor's Blog, page 66

October 20, 2015

Robert Lawrence Kuhn: A Model for How to Dialogue with a Christian Philosopher

Thoughtful conversations, combining inquisitive questioning and respectful listening, shouldn’t be unusual—but they are.

Robert Lawrence Kuhn is an international corporate strategist, investment banker, and public intellectual. He is trained as a scientist, with a PhD in brain research. He created and hosts the public television series Closer to Truth, where he interviews the world’s greatest thinkers on fundamental issues of existence—particularly cosmos, consciousness, and philosophy of religion.

Kuhn, who grew up as a theist, is now noncommittal on the Big Questions:

What do I think? Does God make sense? To me, honestly, nothing makes sense! God? No God? Both hit circularities, regresses, dead-ends. Arguments? I love them all, but in the end, they all falter. Theistic arguments, atheistic arguments—none are dispositive. I’ve (half) joked that if I had to chose, I’d have to say that I find the atheistic arguments more palatable to swallow but the theistic conclusion more satisfying to digest. That doesn’t make sense, of course. And I guess that is my point. It’s not scientifically becoming to admit belief without reason. But to me, honesty trumps image. Throughout this multiyear adventure of producing and hosting Closer To Truth, perhaps I’ve progressed. I now see a richer, more textured picture of what a Supreme Being, if such a being exists, might be like. Many people seem certain of their beliefs. I wish I were certain. I may continue lurching and lapsing in my beliefs, but I will never cease wondering, striving, searching. As for me, for now, passionate uncertainty is closer to truth.

Below is his two-hour conversation with William Lane Craig (author of one of Christianity’s most influential works of apologetics, Reasonable Faith). Dr. Craig says it may be the best interview he’s ever received. Kuhn models a refreshing example of respectful listening, processing, and pressing for clarification. (The video is broken down into various parts here.)

October 19, 2015

C. S. Lewis on the Theology and Practice of Worship

C. S. Lewis may seem like an odd subject for study when it comes to the theology and practice of worship. He was neither a clergyman nor a professional theologian. And though he wrote wisely and winsomely on a wide range of subjects related to the Christian life, he devoted relatively little attention to ecclesiology, liturgy, music, and corporate worship. Nevertheless, the broad outlines of his thinking on the subject of worship can be reconstructed from his occasional essays and private letters. In this post I will seek to demonstrate that Lewis is a valuable, if neglected, voice in discussions about worship and that coming to terms with his perspective will be instructive for all of us, even if we are not fully persuaded by all of his presuppositions and arguments. I will first explore Lewis’s understanding of praise, followed by a survey of his thoughts on the corporate nature of worship, including church music, liturgy, and the sacraments. I will then conclude with a brief analysis.

Why God Commands Praise

Lewis (b. 1898) was baptized in the Church of Ireland (an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion) and attended church with his family during his early years. In 1911, three years after the death of his mother, he abandoned his belief in Christianity. Lewis remained an agnostic until 1929 or 1930, at which time he converted to theism, admitting that “God was God” and feeling like “the most dejected and reluctant convert in all of England.”

In his Reflections on the Psalms, published in 1958, Lewis admits with some embarrassment that when he first began to draw near to God in belief, and even for some time afterward, he found the command to praise God a stumbling block. After all, he noted, we routinely reject those who seek and expect praise and congratulations: “We all despise the man who demands continued assurance of his own virtue, intelligence or delightfulness; we despise still more the crowd of people round every dictator, every millionaire, every celebrity, who gratify that demand.” He took this horizontal reality and applied it vertically: “Thus a picture, at once ludicrous and horrible, both of God and of His worshippers threatened to appear in my mind.”

The Psalms in particular were problematic for him. These were not merely intellectual difficulties for Lewis but profoundly troubling to him spiritually. Lewis found it hideous that God was honored by thanks and praise (Ps 50:23), akin to saying, “What I most want is to be told that I am good and great.” He was bothered by “the suggestion of the very silliest Pagan bargaining,” whereby the Psalmist seems to offer praise to God if he will do something for him (cf. Ps 54:1, 6). He was appalled by the argument that God should save his supplicant from death since those in Sheol cannot give him praise (Ps 30:10; 88:10; 119:175). He found it extremely distressing that mere quantity of praise seemed like an important consideration to God (Ps 119:164). “Gratitude to God, reverence to Him, obedience to Him, I thought I could understand; not this perpetual eulogy.” Lewis was likewise confused, and disturbed, by the teaching that God has the “right” to be praised.

In response, Lewis asks us to begin with something like an inanimate object, which has no rights. What do we mean, he asks, when we say that it is “admirable”? We mean more than that it is admired by others; bad works are often admired and good works ignored, so something can be admired without being truly admirable. We also mean something more than that it deserves to be admired in the sense that an injustice would obtain if admiration is not bestowed. Rather, Lewis argues, an admirable object deserves or demands admiration in the sense that “admiration is the correct, adequate, appropriate, response to it,” and conversely that failing to admire it means we are “stupid, insensible, and great losers” because “we shall have missed something.” In other words, Lewis is saying that something is admirable when admiration is both a fitting and obviously necessary response to it. Lewis then applies this concept to God: “He is that Object to admire which (or, if you like, to appreciate which) is simply to be awake, to have entered the real world; not to appreciate which is to have lost the greatest experience, and in the end to have lost all.”

Lewis came to see that in his previous difficulties with the concept of praise, he had failed to see that “it is in the process of being worshipped that God communicates His presence to men.” This is a key point for Lewis: the command to praise is not just so that God can receive something, but it is bound up the very giving of God himself. So Lewis now had an answer to his previous conception that commanding and craving worship would be “like a vain woman wanting compliments, or a vain author presenting his new books to people who have never met or heard of him.” Lewis had thought about praise of God (and other things) in terms of compliment, approval, or honor. What had escaped his notice is the notion that “all enjoyment spontaneously overflows into praise.”

The world rings with praise—lovers praising their mistresses, readers their favorite poet, walkers praising the countryside, players praising their favorite game—praise of weather, wines, dishes, actors, motors, horses, colleges, countries, historical personages, children, flowers, mountains, rare stamps, rare beetles, even sometimes politicians or scholars.

We not only spontaneously praise what we value but instinctively urge others to join in our praise, rhetorically asking, “Isn’t she lovely? Wasn’t it glorious? Don’t you think that magnificent?” This unlocked the Psalms for Lewis: the psalmist, in enthusiastically imploring others to praise God, was simply doing what all of us do when we enjoy and worship something. “My whole, more general difficulty about the praise of God,” Lewis writes, “depended on my absurdly denying to us, as regards the supremely Valuable, what we delight to do, what we indeed can’t help doing, about everything else we value.”

Lewis next explores the psychology behind this dynamic of necessarily praising what we enjoy. Praise does more than express enjoyment, it actually “completes the enjoyment; it is its appointed consummation.”

It is not out of compliment that lovers keep on telling one another how beautiful they are; the delight is incomplete till it is expressed. It is frustrating to have discovered a new author and not to be able to tell anyone how good he is; to come suddenly at the turn of the road, upon some mountain valley of unexpected grandeur and then to have to keep silent because the people with you care for it no more than for a tin can in the ditch; to hear a good joke and find no one to share it with . . . .

Lewis agrees with the first answer to the Westminster Shorter Catechism, which states that man’s chief end is “to glorify God and enjoy Him forever.” In heaven, Lewis says, when we can fully worship God in spirit and in truth, we shall know that these are really the same thing: “Fully to enjoy is to glorify. In commanding us to glorify Him, God is inviting us to enjoy Him.”

Feelings and Worship

To glorify God by enjoying him forever is the ideal, and it is the eternal destination of all who are in Christ. But Lewis routinely sounds a note of realism, pushing back against the temptation of an over-realized eschatology in our worship. Lewis says that our worship services in local churches—both in how they are conducted and in our own capacity to participate—are merely “attempts” at worship. They are never fully successful; in fact, he goes so far as to say that they are “often 99.9 percent failures, sometimes total failures.” As he does so often, Lewis deploys an evocative metaphor to illumine his point: “We are not riders but pupils in the riding school; for most of us the falls and bruises, the aching muscles and the severity of the exercise, far outweigh those few moments in which we were, to our own astonishment, actually galloping without terror and without disaster.”

Borrowing imagery from John Donne, Lewis reminds us that our earthly worship is merely “tuning our instruments.” The tuning up of an orchestra is delightful only for those who anticipate the symphony. Our most sacred rites, like the Jewish sacrifices in the Old Testament that preceded the sacrifice of Christ, are like the tuning and the promise, not the performance itself. And tuning an instrument, Lewis reminds us, entails much duty but little delight. However, he notes, “the duty exists for the delight.” When we engage in “religious duties” we are like people “digging channels in a waterless land, in order that when at last the water comes, it may find them ready.” Lewis continues: “There are happy moments, even now, when a trickle creeps along the dry beds; and happy souls to whom this happens often.”

In 1949, Lewis was invited to attend the confirmation and first holy communion of his goddaughter, Sarah Nylan. Lewis was unable to attend but penned her a letter with counsel about her mindset and expectations when partaking of communion for the first time:

[D]on’t expect (I mean, don’t count on and don’t demand) that when you are confirmed, or when you make your first Communion, you will have all the feelings you would like to have. You may, of course: but you also may not. But don’t worry if you don’t get them. They aren’t what matter. The things that are happening to you are quite real things whether you feel as you wd. wish or not, just as a meal will do a hungry person good even if he has a cold in the head which will rather spoil the taste. Our Lord will give us right feelings if He wishes—and then we must say Thank you. If He doesn’t, then we must say to ourselves (and Him) that He knows us best.

Lewis went on to assure his goddaughter that this is one of the few subjects upon which he feels he knows something. He relates his own personal struggles on this very front: “For years after I had become a regular communicant I can’t tell you how dull my feelings were and how my attention wandered at the most important moments. It is only in the last year or two that things have begun to come right—which just shows how important it is to keep on doing what you are told.”

Church Music

When it comes to the issue of church music, Lewis assumes from the outset of his discussion that “nothing should be done or sung or said in church which does not aim directly or indirectly either at glorifying God or edifying the people or both.” He relates the two ends in this way: “Whatever we edify, we glorify, but when we glorify we do not always edify.” In other words, the edification of God’s people always glorifies the Lord, but there are individual God-glorifying actions that do not benefit the congregation as a whole. Lewis points to 1 Corinthians 14:2-5 as an example, where Paul prefers understandable (and therefore edifying) prophecy more than speaking in unknown tongues that are unintelligible to others.

Based on this Pauline principle, should the church forbid unintelligible music that is incomprehensible to the understanding of the congregants? Lewis rejects the comparison for three reasons. First, tongues were probably not glorifying to God on account of their aesthetics but rather due to their miraculous nature, involuntary expression, and ecstatic state. Church music, on the other hand, seeks to glorify God by its excellence: “In the composition and highly-trained execution of sacred music we offer our natural gifts at their highest to God, as we do also in ecclesiastical architecture, in vestments, in glass and gold and silver, in well-kept parish accounts, or the careful organization of a Social.” Second, the incapacities to understand a foreign tongue and to understand good music are different in kind. The first is absolute and equal across a group, while the second is not absolute and is not equally incurable. Finally, the alternative to a foreign tongue is an intelligible language, whereas most of the time the alternative to learned music is popular music, which amounts to giving people what they want.

Lewis, for his part, doubts that church members are truly edified when they are allowed to shout out their favorite hymns (a common practice in some low-church settings). He acknowledges that people enjoy doing this and that it is “as wholesome and innocent as a pint of beer, a game of darts, or a dip in the sea.” He also believes that it can be done to the glory of God, just like eating and drinking (cf. 1 Cor 10:31). What Lewis wants to know is “whether untrained communal singing is in itself any more edifying than other popular pleasures.” Lewis remains unconvinced that it is: “I do not yet seem to have found any evidence that the physical and emotional exhilaration which it produces is necessarily, or often, of any religious relevance. What I, like many other laymen, chiefly desire in church are few, better, and shorter hymns; especially fewer.” Lewis—who himself regularly attended the service at his parish church that did not have music—finds the case for abolishing all church music much stronger than the case for abolishing the difficult work of a trained choir in place of the “lusty roar of the congregation.” And yet he knows that the whole of Christendom, reformed and otherwise, would be against an absolute prohibition of music. So he is willing to offer admittedly tentative suggestions as to the way in which church music, if it must be used, can please God or help to save the souls of men.

First, Lewis judges that both camps—the high brows and the low brows—overestimate the spiritual value of the music they prefer. Neither excellence nor enthusiasm signifies specifically religious activity. Second, Lewis articulates the attitudes that should be adopted by both high- and low-brow practitioners and proponents:

One is where a priest or an organist, himself a man of trained and delicate taste, humbly and charitably sacrifices his own (aesthetically right) desires and gives the people humbler and coarser fare than he would wish, in a belief (even, as it may be, the erroneous belief) that he can thus bring them to God. The other is where the stupid and unmusical layman humbly and patiently, and above all silently, listens to music which he cannot, or cannot fully, appreciate, in the belief that it somehow glorifies God, and that if it does not edify him this must be his own defect.

In this way, there will be a means of grace to hearers even through music they have both disliked. It is an offer and sacrifice of taste. Lewis laments that the inverse—where a performer trained in excellence “looks with contempt on the unappreciative congregation” or when the untrained “look with the restless and resentful hostility of an inferiority complex on all who would try to improve their taste”—is a situation where the offering is not blessed and the spirit moving among them is not the Holy Spirit.

Lewis is aware that in offering this perspective he is providing little practical help, but the problem, he cautions, is never merely musical. If both parties are on the right spiritual track then there should not be insurmountable difficulties: “Discrepancies of taste and capacity will, indeed, provide matter for mutual charity and humility.”

For Lewis, the primary purpose of music coincides with the fundamental purpose of the universe: the glory of God. So for the “musically illiterate mass,” among which he numbers himself, a passion for the glory of God means that we must be as ready to glorify him by silence, when required, as by shouting. He counsels those like him to maintain a posture of learning and intelligent listening. “It is not the mere ignorance of the unmusical that really resists improvements. It is jealousy, arrogance, suspicion, and the wholly detestable species of conservatism which those vices engender.” Lewis strongly opposes the practice of democracy in the church, which appeases inferiority complexes and enables our natural hatred of excellence.

Lewis acknowledges that it is more difficult for him to provide counsel for musicians. He returns to the question of how we may glorify God. Lewis observes that all natural agents glorify their Creator by continually revealing the powers he has granted them. As humans, both our good actions and evil actions thus glorify God in a certain sense. Applied to music, Lewis avers, “An excellently performed piece of music, as a natural operation which reveals in a very high degree the peculiar powers give to man, will thus always glorify God whatever the intention of the performers may be.” But of course we want to glorify God in another kind of way, one bound up with intentionality. Lewis confesses that he himself cannot know the facility or difficulty of an entire choir maintaining this collective intentionality, though he says that when they do succeed in this, “I think the performers are the most enviable of men; privileged while mortals to honour God like angels and, for a few golden moments, to see spirit and flesh, delight and labour, skill and worship, the natural and the supernatural, all fused into that unity they would have had before the Fall.” And yet Lewis continues to insist that no degree of excellency can serve as a sufficient condition for glorifying the Lord. “We must beware,” he warns, “of the naive idea that our music can ‘please’ God as it would please a cultivated human hearer. . . . For all our offerings, whether of music or martyrdom, are like the intrinsically worthless present of a child, which a father values indeed, but values only for the intention.”

Innovation in the Church Service

Lewis, despite his personal and strongly held preferences, believed that “anything the congregation can do may properly and profitably be offered to God in public worship.” Individual congregations should make these decisions in accordance with their own abilities for excellence and edification. “If one had a congregation (say, in Africa) who had a high tradition in sacred dancing and could do it really well I would be perfectly in favour of making a dance part of the service. But I wouldn’t transfer the practice to a Willesden [Northwest London] congregation whose best dance was a ballroom shuffle.”

At the same time, Lewis was a traditionalist who was suspicious of novelty and innovation, reveling in the regularity of the church’s liturgy. He did not believe churches should try to lure people to church by “incessant brightenings, lightenings, lengthenings, abridgements, simplifications, and complications of the service.” He equated novelty with entertainment value, and he was convinced that most parishioners (like himself) were impatient with innovation.

Every service is a structure of acts and words through which we receive a sacrament, or repent, or supplicate, or adore. And it enables us to do these things best—if you like, it “works” best—when, through long familiarity, we don’t have to think about it. As long as you notice, and have to count, the steps, you are not yet dancing but only learning to dance. A good shoe is a shoe you don’t notice. Good reading becomes possible when you need not consciously think about eyes, or light, or print, or spelling. The perfect church service would be one we were almost unaware of; our attention would have been on God.

Novelty, according to Lewis, prevents this state from materializing: “It fixes our attention on the service itself; and thinking about the worship is a different thing from worshipping.”

Doctrinal and Liturgical Developments

Beginning in May of 1949, Lewis wrote several letters to the editor of the periodical Church Times, responding to pieces advocating for liturgical developments. In registering his concerns, Lewis provides us with a glimpse into the reasons behind his hesitancies regarding liturgical innovation.

First, Lewis stresses the necessity of uniformity—if in nothing else, at least in the amount of time the rite requires. “We laymen may not be busier than the clergy but we usually have much less choice in our hours of business. The celebrant who lengths the service by ten minutes may, for us, throw the whole day into hurry and confusion.” Lewis believes this could be a distraction and even lead to resentment.

Second, Lewis notes that the Anglo-Catholic theologian-priest who penned the original piece describes various possibilities of liturgical variants, casually including “devotions to the Mother of God and to the hosts of heaven.” Lewis responding by imploring the clergy to believe that laypeople “are more interested in orthodoxy and less interested in liturgiology as such than they can easily imagine.” Lewis comments that an inclusion of these elements would divide a congregation into two camps. Whereas some may assume that this would constitute a liturgical divide, Lewis insists that it would actually be a doctrinal one. “Not one layman would be asking whether these devotions marred or mended the beauty of the rite; everyone would be asking whether they were lawful or damnable.”

Lewis closes by offering a plea for the authorities to remember the vulnerable position of the laypeople they are charged to lead:

What we laymen fear is that the deepest doctrinal issues should be tacitly and implicitly settled by what seem to be, or are avowed to be, merely changes in liturgy. . . . We laymen are ignorant and timid. Our lives are ever in our hands, the avenger of blood is on our heels, and of each of us his soul may this night be required. Can you blame us if the reduction of grave doctrinal issues to merely liturgical issues fills us with something like terror?

One could get the impression from this that Lewis was merely expressing his disapproval of Roman Catholic dogma. Though Lewis made clear his differences with Rome, this was not necessarily the issue at play with his displeasure about liturgical changes. If the Church of England had erred in “abandoning Romish invocations of saints and angels, by all means let our corporate recantation, together with its grounds in scripture, reason and tradition be published, our solemn acts of penitence be performed, the laity re-instructed, and the proper changes in liturgy be introduced.” What bothered Lewis was the idea that Anglican priests could make these decisions individually without corporate due process. Lewis believed that controversy could cease in one of two ways: “by being settled, or by gradual and imperceptible change of custom. I do not want any controversy to cease in the second way.”

“I submit,” Lewis wrote, “that the relation [between liturgy and belief] is healthy when liturgy expresses the belief of the Church, morbid when liturgy creates in the people by suggestion beliefs which the Church has not publicly professed, taught, and defended.” “Most of us laymen,” he writes in another letter, “desire to believe as the Church believes.”

Sacramentalism

Lewis was confirmed in the church (as an agnostic teenager), began a practice of weekly confession to a priest near the end of October 1940, and received the last rites (or extreme unction, or anointing with oil) when he was in a coma in 1963—but he did not refer to any of these practices as a “sacrament.” He followed the Protestant tradition of reserving the designation of sacraments for baptism and Holy Communion.

Because Lewis did not write extensively on the sacraments themselves, we can orient ourselves to his overarching approach by coming to the subject through the backdoor, as it were. Lewis wrote about his understanding of the sacramental nature of reality, which provides us with a paradigm for discerning his approach to the two key Christian ordinances.

For a Christian, there should be a unity between the sign and the signified, between the religious rite and the reality it is intended to communicate or convey. But this is not always the case in our experience. By analogy, Lewis notes that there is a stage in the life of a child when he cannot separate the religious meaning from the festal character of Christmas and Easter. Lewis once heard the story of a young boy who murmured to himself a poem on Easter morning that began, “Chocolate eggs and Jesus risen.” But Lewis reminds us that the child’s effortless and spontaneous enjoyment of this unity is short-lived. At some point he will decouple the spiritual from the ritual and festal aspects of Easter. As Lewis puts it, “chocolate eggs will no longer be sacramental.” Once the distinction is made, prioritization is required: “If he puts the spiritual first he can still taste something of Easter in the chocolate eggs; if he puts the eggs first they will soon be no more than any other sweetmeat.” Applying this to the Eucharist and Baptism, one must focus on Christ more than the elements or the water, but those physical emblems can be a means of tasting or seeing the spiritual presence of Christ.

In an essay on “Transposition,” Lewis explores the relationship between the supernatural and the natural, arguing that it should not surprise us to see “the reappearance in what professes to be our supernatural life of all the same old elements which make up our natural life and (it would seem) of no others.” For example, the Bible describes heaven with familiar images like crowns, thrones, and music, and devotion between God and man is explained with the language of human lovers. Then he asks whether we should really be surprised that “the rite whereby Christians enact a mystical union should turn out to be only the old, familiar act of eating and drinking?”

Lewis goes on to explore the relationship between the higher medium and its transposition into the lower medium. While the relationship between speech and writing is correctly described as symbolic, the term will not do for the relationship between a picture and the visible world. “The suns and lamps in pictures seem to shine only because real suns or lamps shine on them: that is, they seem to shine a great deal because they really shine a little in reflecting their archetypes.” The sunlight in a picture, Lewis concludes, “is a sign, but also something more than a sign: and only a sign because it is also more than a sign, because in it the thing signified is really in a certain mode present.” Lewis writes that if he had to offer a name for this, he would call it “sacramental,” not symbolic.

Baptism

Lewis, faithful Anglican that he was, believed in paedobaptism and was not baptized as a believer following his conversion. In Mere Christianity, an apology for the main claims of the Christian faith, he wrote, “There are three things that spread the Christ life to us: baptism, belief, and that mysterious action which different Christians call by different names—Holy Communion, the Mass, the Lord’s Supper.” Some have taken this to be an indication of his belief in, or at least openness to, baptismal regeneration. One most use caution in making a definitive pronouncement either way, given that Lewis does not appear to address this question directly in his writings. It seems likely that Lewis believed, with the Anglican church, that baptism is a means of grace, but does not operate in the fashion of ex opera operato. For example, there is no evidence Lewis regarded his own baptism as spiritually efficacious.

When a correspondent once asked Lewis about whether one is “made a Christian” by baptism, Lewis responded: “It is only the usual trouble about words being used in more than one sense. Thus we might say a man ‘became a soldier’ the moment that he joined the army. But his instructors might say six months later ‘I think we have made a soldier of him’. Both usages are quite definable, only one wants to know which is being used in a given sentence.” Though Lewis changes the subject to answer another question from this correspondent, and his answer is not definitive in either direction, it seems likely that Lewis intended this distinction to indicate that the language of the New Testament, whereby conversion and baptism are inextricably intertwined, need not mean that baptism necessarily produces regeneration.

Holy Communion

Holy Communion, Lewis writes, is the only rite we know of that the Lord himself instituted. Lewis points for support to Luke 22:19 (“Do this in remembrance of me”) and 1 Corinthians 11:24 (“If you do not eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink His blood, yet have no life in you”). Lewis admits that he does not know and cannot imagine what the disciples understood Jesus to mean when, with unbroken flesh and with unshed blood, handed them the bread and wine, declaring that they were his body and blood (Luke 22:19-20; Matt 26:26-28). He found it impossible to conceive of an Aristotelian substance stripped of its accidents and endowed with the accidents of another substance. In so saying this, he was rejecting the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation. On the other hand, he writes, he gets on no better with those who understand the elements as “mere bread and mere wine, used symbolically to remind me of the death of Christ. They are, on the natural level, such a very odd symbol of that . . . and I cannot see why this particular reminder—a hundred other things may, psychologically, remind me of Christ’s death, equally, or perhaps more—should be so uniquely important as all Christendom (and my own heart) unhesitatingly declare.” In other words, Lewis rejects the memorialist view (or his understanding of it) as insufficient. Nevertheless, Lewis writes that he finds “no difficulty in believing that the veil between the worlds, nowhere else (for me) so opaque to the intellect, is nowhere else so thin and permeable to divine operation. Here a hand from the hidden country touches not only my soul but my body. Here the prig, the don, the modern, in me have no privilege over the savage or the child. Here is big medicine and strong magic . . . the command, after all, was Take, eat: not Take, understand.” In stressing the real spiritual presence of Christ, Lewis was seeking to preserve the profound mystery of the Eucharist while rejecting what he regarded to be inadequate alternatives.

Conclusion

What are we to make of Lewis’s arguments and perspective? Some of our responses will surely be determined by our respective ecclesiastic perspectives. For example, Baptists will demur from his understanding of paedobaptism, and Roman Catholics will reject his objections to Marian devotion or transubstantiation. But what of those arguments that are not explicitly tied to an ecclesiastical position?

Several brief comments may be made by way of analysis and application. First, Lewis is profoundly insightful regarding the power and psychology of praise. God does not command worship for himself because of neediness, but rather is providing us with a means toward our own great joy in him. This has far-reaching implications for our satisfaction in God and for the importance of evangelism.

Second, Lewis is right to explore the relationship between duty and delight as the former serving the latter. He is a realist with respect to human finitude and sin, and he recognizes that we do not yet consistently experience what we shall someday see and feel in full freedom. Perhaps because Lewis not an exegetically driven thinker, he does not wrestle with the divine command and expectation for continual rejoicing (1 Thess 5:16; Phil 4:4) among other commands to express the affections. As such, we are left to guess how he would incorporate this divine imperative into his understanding of worship. One can also wonder whether he is guilty of an under-realized eschatology in his zeal to combat the triumphalism of an over-realized eschatology. Lewis’s comment to his goddaughter that feels don’t matter—even accounting for a touch of hyperbole—does not seem compatible with the New Testament emphasis on the importance of the affections.

Third, while Lewis offers sagacious counsel for both the musically trained and the musically illiterate, his displeasure in singing is disconcerting, especially given Paul’s commands for us to address “one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody to the Lord with your heart” (Eph 5:19) and to be “singing psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, with thankfulness in your hearts to God” (Col. 3:16). Lewis also seems to denigrate all popular-level hymns as falling below a standard of excellence and thus being deficient. I do not see in his own conception that there can be standards of excellence within various genres and levels of music, and that so-called popular hymns may at times highlight the immanence of God at the same time that more sophisticated songs may emphasize the transcendence of God.

Fourth, we can appreciate Lewis’s critiques of entertainment-oriented innovation as a means of drawing new worshippers, though it seems in hindsight that he naively assumed that his own love of tradition would hold sway among fellow congregants, neglecting to consider that the phenomenon of itchy ears (2 Tim 4:3) is not just a tolerance for bad doctrine but an acceptance of bad teachers who undermine the truth in various ways.

Fifth, given Lewis’s ecumenical inclinations, expressed in his understanding of common-denominator (“mere”) Christianity, it is refreshing to see his passion with respect to doctrinal purity and tradition in the liturgy. It is especially moving to see his plea, within the hierarchical structure of his own ecclesiastical context, for the clergy to remember the vulnerability of the sheep who must depend on their under-shepherds to lead and instruct them.

Finally, I find Lewis’s understanding of the sacraments to be quite illuminating and instructive. For those who share Lewis’s disagreements with both Transubstantiation and mere memorialism, Lewis provides an illuminating perspective on how we can see the cup of blessing as an actual “participation in the blood of Christ” and the bread we break as “a participation in the body of Christ” (1 Cor 10:16). It seems to me that Lewis’s perspective here is compatible with the understanding that John Calvin set forth in his Institutes.

As noted in the opening of this paper, we may ultimately disagree with Lewis on various aspects of worship, but his clear thinking and gift of insight can provoke all of us to reexamine our presuppositions and to clarify our positions. For that reason, Lewis is a neglected voice in worship conversations, and the recovery of his perspective can only serve to strengthen our investigation into this crucial subject, which should lead to our engagement with the living triune God.

Notes

Of the making of biographies of Lewis there seems to be no end. They can be categorized in accordance with their approach: some are overly cynical or suspicious (e.g., A. N. Wilson, C. S. Lewis: A Biography [New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2002]); some are hagiographical, with virtually no criticisms (e.g., the authorized biography by his friends Roger Lancelyn Green and Walter Hooper, C. S. Lewis: A Biography, 2nd ed. [New York: HarperCollins, 2003]); and some take a more mediating and judicious approach (e.g., George Sayers, Jack: A Life of C. S. Lewis, reprint ed. [Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2005], Alan Jacobs, The Narnian: The Life and Imagination of C. S. Lewis, reprint ed. [New York: HarperOne, 2008], and now Alister McGrath, C. S. Lewis—A Life: Eccentric Genius, Reluctant Prophet [Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale, 2013]).

In a letter to N. Fridama (February 15, 1946), Lewis provides a succinct summary of his upbringing with respect to Christianity: “I was baptized in the Church of Ireland (same as Anglican). My parents were not notably pious but went regularly to church and took me. My mother died when I was a child. . . . I abandoned all belief in Xtianity at about the age of 14, tho’ I pretended to believe for fear of my elders. I thus went thro’ the ceremony of Confirmation in total hypocrisy. My beliefs continued to be agnostic, with fluctuation towards pantheism and various other sub-Xtian beliefs, till I was about 29″ (C. S. The Collected Letters of C. S. Lewis: Books, Broadcasts, and the War, 1931-1949, vol. 2, ed. Walter Hooper [San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2004], 702).

C. S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy: The Shape of My Early Life (1st ed., 1955; reprint, New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1966), 228-29. Lewis claims that this took place in the Trinity Term of 1929, but McGrath, C. S. Lewis—A Life, 141-45, makes a persuasive case that Lewis’s recollection of dates was often faulty and that the evidence points to June of 1930 as a more probable date for this change.

C. S. Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms (1st ed., 1958; reprint, New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1986), 80.

Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms, 91.

Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms, 91.

Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms, 92.

Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms, 92.

Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms, 93.

Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms, 93.

Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms, 94.

Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms, 95.

Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms, 95.

Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms, 97.

Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms, 97.

Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms, 96.

Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms, 97.

C. S. Lewis to Sarah Neylan (April 3, 1949), Collected Letters, 3:1587.

Lewis to Neylan, Collected Letters, 3:1587.

C. S. Lewis, “On Church Music,” in C. S. Lewis, Essay Collection and Other Short Pieces, ed. Lesley Walmsley (London: HarperCollins, 2000), 403.

Lewis, “On Church Music,” 403.

Lewis, “On Church Music,” 404.

Lewis, “On Church Music,” 404.

Lewis, “On Church Music,” 404-405.

Lewis, “On Church Music,” 405. Cf. also Lewis’s correspondence with Erik Routley (July 16, 1946), where he writes, “To the minority, of whom I am one, the hymns are mostly the dead wood of the service” (Collected Letters, 2:720). To another correspondent Lewis writes, “I naturally loathe nearly all hymns: the face, and life, of the charwoman in the next pew who revels in them, teach me that good taste in poetry and music are not necessary to salvation” (C. S. Lewis to Mary Van Deusen [December 7, 1950], Collected Letters, 3:69).

Will Vaus, Mere Theology: A Guide to the Thought of C. S. Lewis (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004), 175.

Lewis, “On Church Music,” 405.

Lewis, “On Church Music,” 405.

Lewis, “On Church Music,” 405-406.

Lewis, “On Church Music,” 406.

Lewis, “On Church Music,” 406.

Lewis, “On Church Music,” 406.

Lewis, “On Church Music,” 407.

Lewis, “On Church Music,” 407.

C. S. Lewis, Letter to Erik Routley (September 21, 1946), Collected Letters, 2:740.

C. S. Lewis, Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer (1st ed., 1964; Orlando: Harcourt, 1992), 4.

Lewis, Letters to Malcolm, 4.

Lewis, Letters to Malcolm, 4.

C. S. Lewis, “The Church’s Liturgy, Invocation, and Invocation of Saints,” Essay Collection and Other Short Pieces, ed. Lesley Walmsley (London: HarperCollins, 2000), 773-76.

Lewis, “The Church’s Liturgy,” 773-74.

Lewis, “The Church’s Liturgy,” 773.

Lewis, “The Church’s Liturgy,” 773.

Lewis, “The Church’s Liturgy,” 319.

See Vaus, Mere Theology, 169-71, for a summary. Regarding devotion to Mary in particular, Lewis expressed his own views in a letter to a Mrs. Van Deusen: “My own view would be that a salute to any saint (or angel) cannot in itself be wrong any more than taking off one’s hat to a friend: but that there is always some danger lest such practices start one on the road to a state (sometimes found in R.C.’s [Roman Catholics]) where the B.V.M. [Blessed Virgin Mary] is treated really as a deity and even becomes the centre of the religion. I therefore think that such salutes are better avoided. And if the Blessed Virgin is as good as the best mothers I have known, she does not want any of the attention which might have gone to her Son diverted to herself” (Collected Letters, 3:209). Lewis also addressed the question in a letter to H. Lyman Stebbins: “The Roman Church where it differs from this universal tradition and specially from apostolic Xtianity I reject. Thus their theology about the B.V.M. [Blessed Virgin Mary] I reject because it seems utterly foreign to the New Testament: where indeed the words ‘Blessed is the womb that bore thee’ [Luke 11:27-28] receives a rejoinder pointing in exactly the opposite direction. Their papalism seems equally foreign to the attitude of St Paul towards St Peter in the Epistles. The doctrine of Transubstantiation insists in defining in a way wh. the N.T. seems to me not to countenance. In a word, the whole set-up of modern Romanism seems to me to be as much a provincial or local variation from the central, ancient tradition as any particular Protestant sect is. I must therefore reject their claim; tho’ this does not mean rejecting particular things they say.” C. S. Lewis to H. Lyman Stebbins (May 8, 1945), in The Collected Letters of C. S. Lewis: Books, Broadcasts, and the War, 1931-1949, vol. 2, ed. Walter Hooper (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2004), 646-47.

C. S. Lewis, Church Times (July 1, 1949), 427; Lewis, Essay Collection, 774

C. S. Lewis, Church Times (August 5, 1949), 513; Lewis, Essay Collection, 775.

C. S. Lewis, Church Times (July 1, 1949), 427; Lewis, Essay Collection, 774.

C. S. Lewis, Church Times (July 15, 1949), 464; Lewis, Essay Collection, 775.

Vaus, Mere Theology, 193.

Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms, 48-49.

C. S. Lewis, “Transposition,” in Lewis, Essay Collection, 268.

C. S. Lewis, “Transposition,” 272.

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (1st ed., 1952; New York: HarperCollins, 1980), 62.

C. S. Lewis to Genia Goelz (March 18, 1952), Collected Letters, 3:172.

October 16, 2015

How Doctrine Serves the Gospel

John Piper, God Is the Gospel:

The gospel is not only news. It is first news, and then it is doc- trine. Doctrine means teaching, explaining, clarifying. Doctrine is part of the gospel because news can’t be just declared by the mouth of a herald—it has to be understood in the mind of a hearer. If the town crier says, “Amnesty is herewith published by the mercy of your Sovereign,” someone will ask, “What does amnesty’ mean?” There will be many questions when the news is announced. “What is the price that has been paid?” “How have we dishonored the King?” When the gospel is proclaimed, it must be explained. What if the shortwave radio announcer used technical terminology that some of the prisoners were not sure of? Someone would need to explain it. Unintelligible good news is not even news, let alone good.

Gospel doctrine matters because the good news is so full and rich and wonderful that it must be opened like a treasure chest, and all its treasures brought out for the enjoyment of the world.

Doctrine is the description of these treasures.

Doctrine describes their true value and why they are so valuable.

Doctrine guards the diamonds of the gospel from being discarded as mere crystals.

Doctrine protects the treasures of the gospel from the pirates who don’t like the diamonds but who make their living trading them for other stones.

Doctrine polishes the old gems buried at the bottom of the chest. It puts the jewels of gospel truth in order on the scarlet tapestry of history so each is seen in its most beautiful place.

And all the while, doctrine does this with its head bowed in wonder that it should be allowed to touch the things of God.

It whispers praise and thanks as it deals with the diamonds of the King.

Its fingers tremble at the cost of what it handles.

Prayers ascend for help, lest any stone be minimized or misplaced.

And on its knees gospel doctrine knows it serves the herald. The gospel is not mainly about being explained. Explanation is necessary, but it is not primary. A love letter must be intelligible, but grammar and logic are not the point. Love is the point. The gospel is good news. Doctrine serves that. It serves the one whose feet are bruised (and beautiful!) from walking to the unreached places with news: “Come, listen to the news of God! Listen to what God has done! Listen! Understand! Bow! Believe!”

—John Piper, God Is the Gospel: Meditations on God’s Love as the Gift of Himself (Wheaton: Crossway, 2005), 21-22.

October 6, 2015

Anselm’s Prayer for Fullness of Joy in God

Anselm of Canterbury (c. 1033-1109):

I pray, O God, that I may know you and love you,

so that I may rejoice in you.

And if I cannot do so fully in this life

may I progress gradually until it comes to fullness.

Let the knowledge of you grow in me here [on earth],

and there [in heaven] be made complete;

Let your love grow in me here

and there be made complete,

so that here my joy may be great in hope,

and there be complete in reality.

Lord, by your Son, you command, or rather, counsel us to ask

and you promise that we shall receive

so that our “joy may be complete” [John 16:24].

I ask, Lord, as you counsel through our admirable Counselor.

May I receive what you promise through your truth so that my “joy may be complete” [John 16:24].

Until then let my mind meditate on it,

let my tongue speak of it,

let my heart love it,

let my mouth preach it.

Let my soul hunger for it,

let my flesh thirst for it,

my whole being desire it,

until I enter into the “joy of the Lord” [Matt. 25:21],

who is God, Three in One, “blessed forever. Amen” [Rom. 1:25].

Anselm, Proslogion

October 1, 2015

Discipling People with Intellectual Disabilities

Jill Miller (wife of Paul) is a gift to the church. Here’s a short video of her discipling her daughter in the Lord:

For more on the Bethesda curriculum—Bible studies for those affected with intellectual disabilities—go here.

I interview Paul about this curriculum last year:

An Interview with J. I. Packer on Cultivating Awe, Christian Meditation, and Knowing Christ

In the foreword for Mark Jones’ new book, Knowing Christ, J. I. Packer writes:

The Puritans loved the Bible, and dug into it in depth. Also, they loved the Lord Jesus, who is of course the Bible’s focal figure; they circled round him, centred on him, studied minutely all that Scripture had to say about him, and constantly, conscientiously, exalted him in their preaching, praises, and prayers.

Mark Jones, an established expert on many aspects of Puritan thought, also loves the Bible and its Christ, and the Puritans as expositors of both; and out of this triune love he has written a memorable unpacking of the truth about the Saviour according to the classic Reformed tradition, and the Puritans supremely. It is a book calculated to enrich our twenty-first-century souls, and one that it is an honour to introduce.

Just here, however, there lies—or maybe I should say we have, or perhaps even we are—a problem. To put it pictorially, souls are small in the modern Western world, and we have less of an appetite for this kind of nourishment than our spiritual health actually requires. We would do well to ask ourselves some questions.

Have we ever, up to now, worked our way through any book that fully displays our Saviour as the brightest lights in the historic Reformed firmament have viewed him? Here is such a book: are we interested?

Have we ever formed the holy habit of contemplating Jesus in solitude, allowing Scripture passage after Scripture passage to show us his many-sided glory and to draw us out in the many-angled adoration that is our proper response? This book will help us form that habit.

Do we cultivate awe in the presence of the one who calls us who believe his brothers and sisters, and who once took the place of each of us under the unimaginably horrific reality of divine retribution for our sins? And do we often make a point of telling ourselves, and telling him, how lost we would be without him? Or are our minds as Christians always on other things? The present book will lead us in the right path.

Do we constantly acknowledge the presence of Christ, who through the Holy Spirit keeps his promise to be with us always, whether we cherish his gracious and triumphant companionship or not? This book will help us to possess our possession at this point.

Thank you, Mark Jones; you serve us well. May we all benefit from the wealth of enlivening gospel truth and wisdom that you have put together for us in the pages that follow.

The book is available from WTS Books, Amazon, and others.

Below is a conversation between Dr. Jones and Dr. Packer:

And a couple of blurbs about the book:

“This is a work that will serve the church permanently in helping readers ‘to know,’ whether much better or for the first time, ‘the love of Christ that surpasses knowledge.’ I commend it most highly.”

—Richard B. Gaffin, Jr.

“Knowing Christ is a majestic gem that will be passed down from generation to generation as a beloved devotional. Its author takes the reader by a loving pastoral hand into depths and riches, exhorting us to know Christ better and to love him more.”

—Rosaria Butterfield

September 29, 2015

Not All Doctrines Are at the Same Level: How to Make Some Distinctions and Determine a Doctrine’s Importance

Here are three models I have found helpful over the years.

Erik Thoennes: 4 Categories Based on 7 Considerations

Erik Thoennes, professor of theology at Biola University, writes the following in Life’s Biggest Questions: What the Bible Says about the Things That Matter Most (Crossway, 2011):

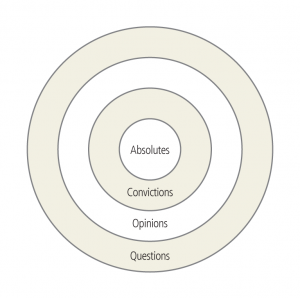

The ability to discern the relative importance of theological beliefs is vital for effective Christian life and ministry. Both the purity and unity of the church are at stake in this matter. The relative importance of theological issues can fall within four categories:

absolutes define the core beliefs of the Christian faith;

convictions, while not core beliefs, may have significant impact on the health and effectiveness of the church;

opinions are less-clear issues that generally are not worth dividing over; and

questions are currently unsettled issues.These categories can be best visualized as concentric circles, similar to those on a dart board, with the absolutes as the “bull’s-eye”:

Where an issue falls within these categories should be determined by weighing the cumulative force of at least seven considerations:

biblical clarity;

relevance to the character of God;

relevance to the essence of the gospel;

biblical frequency and significance (how often in Scripture it is taught, and what weight Scripture places upon it);

effect on other doctrines;

consensus among Christians (past and present); and

effect on personal and church life.These criteria for determining the importance of particular beliefs must be considered in light of their cumulative weight regarding the doctrine being considered. For instance, just the fact that a doctrine may go against the general consensus among believers (see item 6) does not necessarily mean it is wrong, although that might add some weight to the argument against it. All the categories should be considered collectively in determining how important an issue is to the Christian faith. The ability to rightly discern the difference between core doctrines and legitimately disputable matters will keep the church from either compromising important truth or needlessly dividing over peripheral issues.

(Diagram copyright 2009 Crossway Bibles. Posted with permission.)

Albert Mohler’s 3 Orders of Doctrine

In this article, Al Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and professor of theology, distinguishes between three levels of doctrine:

first-order doctrines: a denial of which represents the eventual denial of Christianity itself

second-order doctrines: upon which Bible-believing Christians may disagree, but they create significant boundaries between believers, whether as distinct congregations or denominations

third-order doctrines: upon which Christians may disagree, but yet remain in close fellowship, even within local congregations

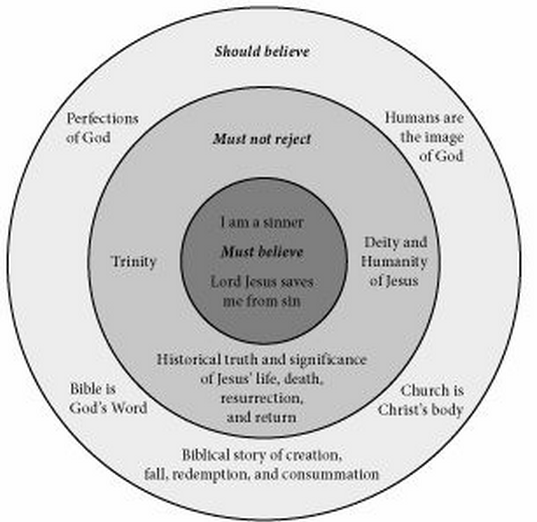

Michael Wittmer’s 3 Categories of Belief

Michael Wittmer, professor of theology and historical theology at Grand Rapids Theological Seminary, wrote a helpful book entitled, Don’t Stop Believing: Why Living Like Jesus Is Not Enough. He classifies Christian beliefs into three categories:

what you must believe

what you must not reject

what you should believe

In a 2008 interview with Dr. Wittmer, I asked him to explain these categories:

These categories are my attempt to describe the relative importance of Christian beliefs, distinguishing between those beliefs essential for salvation and those essential for a healthy Christian worldview.

[What You Must Believe]

In the book of Acts, the bare minimum that a person must know and believe to be saved was that he was a sinner and that Jesus saved him from his sin. As Paul told the Philippian jailer, “Believe in the Lord Jesus and you will be saved” (Acts 16:29-31; cf. 10:43). This is enough to counter the postmodern innovator argument that we can be saved without knowing and believing in Jesus.

[What You Must Not Reject]

But any thinking convert will inquire further about this Jesus. While he may not know much more at the point of conversion than Jesus is the Lord who has saved him, he will quickly learn about Jesus’ life, death, resurrection, deity and humanity, and relation to the other two members of the Trinity. Anyone who rejects these core doctrines should fear for their soul.

According to the Athanasian Creed, whoever does not believe in the Trinity and the two natures of Jesus is damned. However, since it seems possible for a child to come to faith without knowing much about the Trinity or the hypostatic union (this is likely not the place where most parents begin), I take the Creed’s warning in a more benign way—that we do not need to know and believe in the Trinity and two natures of Christ to be saved, but that anyone who knowingly rejects them cannot be saved.

[What You Should Believe]

The final category is important doctrines which genuine Christians may unfortunately misconstrue. I think that every Christian should believe that Scripture is God’s Word, know its story of creation, fall, redemption, and consummation, and know something about the nature of God, what it means to be human, and what Jesus is doing through his church. However, many people have been genuine Christians without knowing or believing these things (though their ignorance or disbelief in these facts significantly diminished their Christian faith).

Thus, I believe that every doctrine in this diagram is crucially important for sound Christian faith. And some are so important that we cannot even be saved without them.

Diagram posted with permission of Zondervan.

September 28, 2015

Patrick Johnstone on the Origin of “Operation World” and How You Can “Pray for the World”

Jason Mandryk talks with missionary-turned-missions-researcher Patrick Johnstone (b. 1938) about Operation World (in my view, one of the most remarkable Christian publications of the 20th century):

I’m very happy that InterVarsity Press has published a new book that carries on the legacy of Operation World, entitled Pray for the World. Here’s a description of it:

I’m very happy that InterVarsity Press has published a new book that carries on the legacy of Operation World, entitled Pray for the World. Here’s a description of it:

For decades, Operation World has been the world’s leading resource for people who want to impact the nations for Christ through prayer. Its twofold purpose has been to inform for prayer and to mobilize for mission. Now the research team of Operation World offers this abridged version of the 7th edition called Pray for the World as an accessible resource to facilitate prayer for the nations. The Operation World researchers asked Christian leaders in every country, “How should the body of Christ throughout the world be praying for your country?” Their responses provide the prayer points in this book, with specific ways your prayers can aid the global church. When you hear a country mentioned in the news, you can use Pray for the World to pray for it in light of what God is doing there. Each entry includes:

Timely challenges for prayer and specific on-the-ground reports of answers to prayer

Population and people group statistics

Charts and maps of demographic trends

Updates on church growth, with a focus on evangelicals

Explanations of major currents in economics, politics and societyJoin millions of praying people around the world. Hear God’s call to global mission. And watch the world change.

George Marsden Lectures on C. S. Lewis’s “Mere Christianity”

George Marsden’s next book is a biography of C. S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity (March 2016), in Princeton’s innovative series profiling the lives of religious books.

Here is a lecture on the ongoing vitality of Lewis’s classic, delivered at Biola University on February 26, 2015.

September 24, 2015

4 Tips for Using a Study Bible Well

Here are some suggestions from a recent article I wrote for Ligonier’s Tabletalk magazine:

Here are some suggestions from a recent article I wrote for Ligonier’s Tabletalk magazine:

First, use your study Bible discerningly.

The most important feature in a study Bible is the horizontal line that divides the biblical text from the biblical interpretation. Everything above the line is inerrant and infallible. Everything below the line is filled with good intentions but may not be true. We are to be like the noble Bereans who cross-checked the teaching they received with the authoritative Word of God (Acts 17:11; see 1 Thess. 5:21). To paraphrase Galatians 1:8-9, “Even if we or a bestselling study Bible should preach to you a gospel contrary to the one we preached to you, let it be accursed.”

Second, use your study Bible for more than just the notes.

I am convinced that the most underutilized and yet important parts of a good study Bible are the introductions to each biblical book. A careful reading of the introduction will help you see the big picture. Use study Bible introductions well, and you will be less likely to take a passage out of context.

Third, use more than one study Bible.

Not all study Bibles are created equal. There are some I would highly recommend and some I would highly discourage Christians from using. Don’t make your decision primarily based on the quality of the Bible or the attractiveness of the design or the promises on the box. Rather, do some research to find out the theological position of the study Bible, who wrote and edited the notes, and whether there is a focus or theme that it is trying to advance.

Fourth, use your study Bible as an opportunity to interpret the Bible with the communion of saints.

Some people object to study Bibles. After all, do we need all these notes to tell us what Scripture really says? But “God has appointed in the church … teachers” (1 Cor. 12:28). As C.H. Spurgeon noted, “It seems odd, that certain men who talk so much of what the Holy Spirit reveals to themselves, should think so little of what he has revealed to others.”

The best study Bibles don’t present startling new interpretations. They put you in dialogue with the best interpreters—teachers who are gifts of God to the church—to help us rightly handle His Word. When they do, we can truly say: all glory to God alone.

You can read the whole article here, in which I try to show how good study Bibles, used well, can give good guidance in understanding history, practicing exegesis, and making theological application.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers