Justin Taylor's Blog, page 61

December 14, 2015

How to Use the Lord’s Prayer to Pray in the Lord’s Way

John Piper models it for us in this new four-minute video from Desiring God:

You can find more resources here.

December 12, 2015

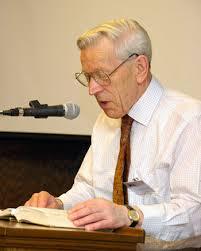

“I. Howard Marshall (1934-2015): A Tribute,” by Darrell Bock

Ian Howard Marshall, born on January 12, 1934, died on December 12, 2015, after a short battle with pancreatic cancer. Marshall, an Evangelical Methodist who was born and lived most of his life in Scotland, served as Professor Emeritus of New Testament Exegesis at the University of Aberdeen. He was a prolific author who influenced countless evangelical scholars through his mentorship and writings. One of his former students, Darrell Bock, Executive Director of Cultural Engagement and Senior Research Professor of New Testament Studies at Dallas Theological Seminary, earned his doctorate under Professor Marshall at Aberdeen in 1983. Here is his tribute to the man.

Guest post by Darrell Bock

If one writes about the life of a scholar, you can expect a list of his books and academic accomplishments. But what is that scholar like as a person? What mark did that leave? When I think of I. Howard Marshall, it is who he was that made him special, not just what he did.

If one writes about the life of a scholar, you can expect a list of his books and academic accomplishments. But what is that scholar like as a person? What mark did that leave? When I think of I. Howard Marshall, it is who he was that made him special, not just what he did.

In 1979, my wife and I travelled to Aberdeen to begin an adventure in study that would open up not only gospels study and attention to the works of Luke-Acts, but an awareness that the Christian faith extended its impact around the world in a wide array of ways.

The initial tour guide into that journey was I. Howard Marshall. It had been the works of Marshall in New Testament Christology and a newly published, full commentary on Luke (the first done in more than forty years) that had drawn me to Aberdeen. Here was a mentor who was emerging as the successor to F. F. Bruce (1910-1990), a top flight evangelical teaching in Europe and writing at the highest level of the academic study with a pen that expressed a deep faith in his Lord.

I had expected to see a giant of a man. In fact, Howard reflected the humble Scottish roots of his home. Rather than a six-foot plus giant, Sally and I met a man who she could look at eye to eye, but his welcome and heart was the size of Texas. It was common to hear that he was meeting with students not just to review the current chapter dedicated to their thesis (what the British call a dissertation) but to pray with them. He opened his home to welcome those students and host them, making sure their arrival in Scotland and a foreign land had left them feeling at home.

He engaged in theological discussion and debate as a conservative of deep conviction who demanded that one’s work be thorough but also fair to the views being challenged. He spoke with a soft voice that communicated with clarity and gravity about the way one should regard the Scripture. That captured people’s attention. The depth of his awareness covering a sweep of topics was stunning. Despite all of that ability and knowledge, what struck one about Howard was his humility and devotion to God. His critique was delivered with a gentleness that not only made clear what might be misdirected but also that showed he cared about how that critique was received.

One incident after my time in Aberdeen is still clear to me. On a return visit to Aberdeen, we brought our family with us. Our two girls had been born in bonnie Scotland, but my son had not. It was the first and only time Howard met our son, who was a very young, playful, five-year-old boy at the time. The Marshalls had a tea warmer in the shape of penguin. Another aspect of Howard’s personality is that he had a classic Scottish wit. So Stephen spotted the warmer and was drawn to it. He offered Stephen to let him play with it and got down on the floor with him to share in the moment. Stephen took advantage of his new playmate and promptly placed the penguin on Howard’s head, leaving both of them laughing and my wife nothing short of horrified. But that was Howard, sensitive to where people were coming from with an eye to where they could go. When I remember Howard Marshall, it is this moment that most typifies him as a person.

If you saw him on the street, you would have no idea that here was a person who would impact biblical studies for decades. What you saw was a believer who cared about people so much that his study showed his care. Yes, Howard Marshall was a great biblical and New Testament scholar who could tell you more about Jesus than most, but as a person he was what the Lord calls us all to be, a person who loved God and his neighbor—not just teaching about that connection but showing it.

We will miss him, but never forget the life lessons he taught.

See also the TGC tribute written by another former student, Ray Van Neste.

December 10, 2015

Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s Harvard Commencement Address

In 1974, the Soviet Union deported dissident writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn, . . . author of The Gulag Archipelago and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, and winner of the 1970 Nobel Prize in literature. After living in Cologne, Germany; Zurich, Switzerland; and at Stanford University, he settled in Cavendish, Vermont, in 1976.

Two years later, Harvard awarded the 59-year-old Solzhenitsyn an honorary doctor of letters degree and chose him as its Commencement speaker. His address on June 8, 1978, was Solzhenitsyn’s first public statement since his arrival in the United States. Given the suffering he had endured in the Soviet Union, many in the audience expected that the writer’s address would be a stern rebuke to Communist totalitarianism, combined with a paean to Western liberty and democracy.

The Tercentenary Theatre audience was in for a rude surprise.

“The Exhausted West,” delivered in Russian with English translation under overcast skies, chastised the arrogance and smugness of Western materialist culture and exposed the adverse effects of some of those achievements that Western democracies had long prided themselves upon. “The defense of individual rights has reached such extremes as to make society as a whole defenseless against certain individuals,” the author declared, for example. “It is time, in the West, to defend not so much human rights as human obligations.”

Solzhenitsyn’s brilliant, iconoclastic speech ranks among the most thoughtful, articulate, and challenging addresses ever delivered at a Harvard Commencement.

You can read the complete English translation given that day.

You can watch also watch the speech below (which begins around the 2:00) mark, in simultaneous translation from English into Russian.

December 9, 2015

The Star of Bethlehem on Fox News

On Fox News Lauren Green recently interviewed Dr. Colin Nicholl about his new book, The Great Christ Comet: Revealing the True Star of Bethlehem (Crossway, 2015):

Watch the latest video at video.foxnews.com

December 8, 2015

A Crash Course on the Muslim Worldview and Islamic Theology

Adam Francisco (who has a Ph.D. in Islamic-Christian relations from Oxford University) is professor of history at Concordia University in Irvine, California.

His work on the history of Islam is nuanced and informed. As one online bio notes, “He has a unique ability to see and understand both the difficulties facing Christians who wish to evangelize their Muslim friends and the Muslims who are being asked to come to Christ. Many of his unique insights come from personal experiences sharing his faith with Muslims.”

To get a taste, see the first couple of videos produced by Modern Reformation below, which provide some brief historical background.

If that whets your appetite, you can view four lectures he gave at Faith Lutheran Church in Capistrano Beach, California, on

The Muslim Worldview

Islamic Theology: Part 1

Islamic Theology: Part 2

Islam in America

The Moody Bible Institute, Business, and the Making of Modern Evangelicalism

From my Themelios review of Tim Gloege’s Guaranteed Pure: The Moody Bible Institute, Business, and the Making of Modern Evangelicalism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015):

In this engaging and provocative study, Timothy Gloege seeks to show how two generations of evangelicals at the Moody Bible Institute (hereafter MBI) used new business ideas and techniques to create a modern form of “old-time religion,” smoothing the rise of consumer capitalism and transforming the dynamics of Protestantism in America.

In the first half of his book, Gloege examines post-Civil War evangelicalism under the influence of D. L. Moody and R. A. Torrey. Responding to labor unrest in Chicago, Moody (the shoe-salesman-turned-revivalist) strategized with local business leaders to build an army of “Christian workers” who could convert the middle class and restore social stability. In his efforts to create “Christian workers”—the evangelical version of the idealized industrial worker in the Gilded Age—Moody forged new links between economic identity and religious identity.

But when the masses from the working class were not converted and social order was not restored, Moody’s project was in crisis. His conception of the Christian life—a personal relationship with God, guided by a plain reading of Scripture, leading to practical and quantifiable results—was bringing more disorder than order. Instead of joining the respectable middle class, Moody’s working-class converts were becoming Populists (critiquing capitalism and professionalization) or Pentecostal (speaking in tongues and rejecting medicine). Even Torrey, Moody’s most famous evangelistic associate at MBI, had been led by his “plain reading” of the Bible and his “evangelical realism” to embrace faith healing, a decision that tragically cost his daughter her life when he delayed the administration of medicine while she was ill, bringing about controversy and scandal. The death of Moody—one week before the dawn of the twentieth century—can be seen as the death of respectable evangelicals’ hermeneutical innocence. No longer could a plain reading of Scripture be embraced without fear of radically disruptive results.

In the second half of the book, Gloege traces the attempt of MBI to stabilize evangelicalism without depending upon churchly guardrails. This entailed the creation of a modern form of “old-time religion,” much of it owing to MBI board chairman Henry Parsons Crowell (who shifted the operating metaphor from Christian worker to Christian consumer) and dispensational Bible teacher James M. Gray (who popularized an esoteric alternative to Moody’s plain-reading of Scripture).

Just as Crowell’s Quaker Oats business had increased its market share by eliminating wholesalers—who traditionally funneled goods between retailers and consumers—Crowell positioned MBI to reach the end consumer of religion, the respectable middle class, while bypassing the institutional church and her denominations. To do this he used the tools of a consumer culture he had perfected at Quaker Oats: trademark, packaging, and promotion. Quaker Oats won the market through the visage of a smiling Quaker vouching for a “pure” product packaged in a safe and sealed container; so now the moniker of Dwight L. Moody guaranteed the purity of the product MBI was offering to savvy consumers who faced unprecedented choice in the religious market.

In order to carry the day, however, a historical tradition had to be invented that would function as a new standard of orthodoxy—a set of essentials or fundamentals capable of uniting a transdenominational coalition of respectable conservative evangelicals. This was achieved through the publication of The Fundamentals (1910-1915), funded by oil businessman and Biola founder Lyman Stewart and produced under the functional control of MBI.

In the final chapter of the book (before an epilogue that applies the book’s findings to contemporary evangelicalism), Gloege narrates the growing separation between MBI and the World Christian Fundamentals Association. Although they were largely on the same page theologically, key stylistic and political differences emerged between MBI and the militant fundamentalists. The demise of combative fundamentalism among the respectable middle-class was ultimately to the benefit of MBI, whose ministry continues to thrive today, even if it no longer dominates the conservative evangelical market.

For my analysis of the book, you can read the whole thing here.

December 4, 2015

A Simple Way You Can Help Get 100,000 Free Study Bibles into the Hands of Leaders Around the World

From Crossway:

The Great Hunger and Need for God’s WordSo many Christian leaders on the front lines of global ministry are under-resourced, lacking even Bibles and the most basic Christian resources.

To help meet this great hunger and need for God’s Word, Crossway is requesting your help to equip 100,000 Christian leaders with copies of the ESV Global Study Bible, in places where the need is greatest, particularly in India, Africa, and other parts of Asia.

Partner with UsTo accomplish this distribution, we are seeking to raise $400,000 by December 31, 2015. Our prayer is that through the Lord’s gracious provision—working with on-the-ground frontline ministry partners—we can with great efficiency send an additional 100,000 free copies of the ESV Global Study Bible to Christian leaders hungry for God’s Word. For many of these Christian leaders, the Global Study Bible may be the only doctrinally sound Bible-teaching content that they have.

If the Lord should lead you, would you please consider making a gift of support to help provide an additional 100,000 free Global Study Bibles?

You can easily donate here.

December 3, 2015

“God Isn’t Fixing This”: Andy Crouch’s Pitch-Perfect Response

Christianity Today executive editor Andy Crouch has a pitch-perfect response to the critique that “God isn’t fixing this” and that politicians and people of faith should stop saying our “thoughts and prayers” are with the victims of the San Bernardino shooting and that action is needed rather than prayer.

Christianity Today executive editor Andy Crouch has a pitch-perfect response to the critique that “God isn’t fixing this” and that politicians and people of faith should stop saying our “thoughts and prayers” are with the victims of the San Bernardino shooting and that action is needed rather than prayer.

Crouch writes, “We can say with some confidence that all the following are true.”

[The bold headings are my summations. What follows are excerpts from each of Crouch’s points.]

[1. Almost all of us naturally express empathy in our familiar terms.]

1.a. When news of a tragedy reaches us, almost all of us find our thoughts overwhelmed for minutes, hours, or days, depending on the scope, severity, and vividness of the loss. This is called empathy—our ability to put ourselves in the place of others and imagine their suffering and fear, as well as heroism and courage, and to wonder how we would react in their place.

1.b. Almost all human beings, whatever their formal religious affiliation, find themselves caught up in a further reaction to tragedy: reaching out to a personal reality beyond themselves, with grief, groaning, and petition for relief. . . .

1.c. Unless the tragedy is literally at our door, this empathic response—call it “thoughts and prayers”—is all that is available to us in the moments after terrible news reaches us. . . .

1.d. It is unrealistic, and arguably cruel, to ask for fresh words in the moment that we are confronted with suffering and loss, let alone horror and evil. Every human being, in these moments, falls back on liturgies—patterns of language and behavior learned long before that get us through the worst moments in our lives. . . .

1.e. Politicians and public figures are fundamentally like all other human beings and have the same basic responses to tragedy. This is true no matter their position on controversial issues of policy (say, gun control). So it is no surprise that they respond immediately, like the rest of us do, with familiar words and phrases that express their human solidarity with those who suffer. . . .

[2. Prayerful lament is right and does not ask God to “fix” things.]

2.a. To offer prayer in the wake of tragedy is not, except in the most flattened and extreme versions of populist Christianity, to ask God to “fix” anything. . . .

2.b. An equally valid and instinctive form of prayer in the face of tragedy is lament, which calls out in anguish to God, asking why the wicked prosper and the righteous suffer. . . .

2.c. No honest accounting of history can deny that God, if there is a God, is terrifyingly patient with evil. And yet, over and over, astonishing goodness, holiness, and reconciliation have emerged from even the most heinous acts of violence. . . .

[3. Prayer and action should not be played against each other.]

3.a. To suggest that we should act (though usually without specifying how those of us not physically present could act in the immediate wake of tragedy or terror), instead of pray, therefore, is to ask us to deny our capacity for empathy.

3.b. At the same time, the Bible makes it clear that God despises acts of outward piety or sentimentality that are not matched with action on behalf of justice. . . .

3.c. Therefore we must never settle for a false dichotomy between prayer and action, as if it were impossible to pray while acting or act while praying. . . .

3.d. To insist that people should act instead of pray, or that we should act without praying, is idolatry, substituting the creature for the Creator. . . .

[4. The victims are in our thoughts and prayers.]

4. Therefore the victims of the shootings in San Bernardino, and all those who were caught up in the violence and live this very moment in its awful continuing reality and consequences, and also those who perpetrated the violence, are in our thoughts and prayers.

You can read the whole thing here.

Does the Bible Support Slavery?

What do you think is wrong with the following argument?

Bible translations talk of “slaves.”

In the OT no objection is made to having slaves.

In the NT Christians are not commanded to free their slaves but are told to submit.

Therefore, biblical texts approve of slavery.

We know that slavery is wrong.

Therefore, biblical texts approve of something that is wrong.

Remember that when evaluating an argument

terms are either clear or unclear

propositions are either true or false,

arguments are either valid or invalid.

So if you disagree with argument above, you’d have to show that there is

an ambiguous term,

a false premise, or

a logical fallacy (the conclusion does not follow from the premises).

In the lecture below, delivered on October 30, 2015, at Lanier Theological Library, Peter Williams gave a fascinating lecture responding to this argument. Dr. Williams (PhD, University of Cambridge) presides over Tyndale House in Cambridge (one of the finest theological libraries in the world for biblical scholarship) and is an affiliated lecturer at Cambridge University.

His thesis is that using the most common definition of slavery, the Bible does not support slavery.

To make his argument, he examines the key Old Testament and New Testament texts said to support slavery. Along the way, he looks at the biblical words commonly associated with slavery and how their translation has changed over time. He also looks at the logic of the Old Testament world and the way ancient societies were structured quite differently from ours.

The lecture below is under an hour, and then he takes Q&A for around 20 minutes:

For reading on this subject, you could start with the following by philosopher Paul Copan:

Does the Old Testament Endorse Slavery? An Overview

Does the Old Testament Endorse Slavery? Examining Difficult Texts

Why Is the New Testament Silent on Slavery—Or Is It?

December 2, 2015

The True Story of Pain and Hope Behind “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day”

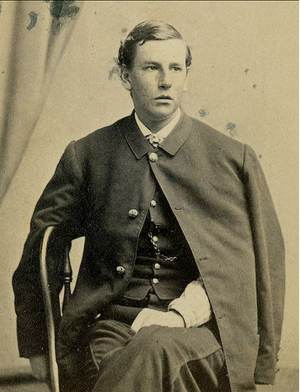

In March of 1863, 18-year-old Charles Appleton Longfellow walked out of his family’s house on Brattle Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and—unbeknownst to his family—boarded a train bound for Washington, D.C., traveling over 400 miles across the eastern seaboard in order to join President Lincoln’s Union army to fight in the Civil War.

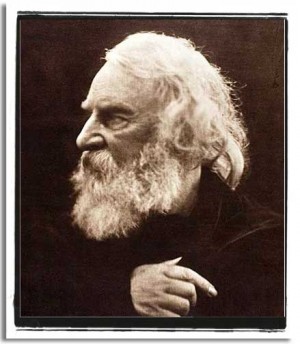

Charles (b. June 9, 1844) was the oldest of six children born to Fannie Elizabeth Appleton and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the celebrated literary critic and poet. Charles had five younger siblings: a brother (aged 17) and three sisters (ages 13, 10, 8—another one had died as an infant).

Less than two years earlier, Charles’s mother Fannie had tragically died after her dress caught on fire. Her husband, awoken from a nap, tried to extinguish the flames as best he could, first with a rug and then his own body, but she had already suffered severe burns. She died the next morning (July 10, 1861), and Henry Longfellow’s facial burns were severe enough that he was unable even to attend his own wife’s funeral. He would grow a beard to hide his burned face and at times feared that he would be sent to an asylum on account of his grief.

When Charley (as he was called) arrived in Washington D.C., he sought to enlist as a private with the 1st Massachusetts Artillery. Captain W. H. McCartney, commander of Battery A, wrote to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow for written permission for Charley to become a soldier. HWL (as his son referred to him) granted the permission.

Longfellow later wrote to his friends Charles Sumner (senator from Massachusetts), John Andrew (governor of Massachusetts), and Edward Dalton (medical inspector of the Sixth Army Corps) to lobby for his son to become an officer. But Charley had already impressed his fellow soldiers and superiors with his skills, and on March 27, 1863, he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry, assigned to Company “G.”

After participating on the fringe of the Battle of Chancellorsville in Virginia (April 30-May 6, 1863), Charley fell ill with typhoid fever and was sent home to recover. He rejoined his unit on August 15, 1863, having missed the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1863).

1868

While dining at home on December 1, 1863, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow received a telegram that his son had been severely wounded four days earlier. On November 27, 1863, while involved in a skirmish during a battle of of the Mine Run Campaign, Charley was shot through the left shoulder, with the bullet exiting under his right shoulder blade. It had traveled across his back and skimmed his spine. Charley avoided being paralyzed by less than an inch.

He was carried into New Hope Church (Orange County, Virginia) and then transported to the Rapidan River. Charley’s father and younger brother, Ernest, immediately set out for Washington, D.C., arriving on December 3. Charley arrived by train on December 5. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was alarmed when informed by the army surgeon that his son’s wound “was very serious” and that “paralysis might ensue.” Three surgeons gave a more favorable report that evening, suggesting a recovery that would require him to be “long in healing,” at least six months.

On Christmas day, 1863, Longfellow—a 57-year-old widowed father of six children, the oldest of which had been nearly paralyzed as his country fought a war against itself—wrote a poem seeking to capture the dynamic and dissonance in his own heart and the world he observes around him. He heard the Christmas bells that December day and the singing of “peace on earth” (Luke 2:14), but he observed the world of injustice and violence that seemed to mock the truthfulness of this optimistic outlook. The theme of listening recurred throughout the poem, eventually leading to a settledness of confident hope even in the midst of bleak despair.

You can read the whole poem below:

I heard the bells on Christmas Day

Their old, familiar carols play,

and wild and sweet

The words repeat

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And thought how, as the day had come,

The belfries of all Christendom

Had rolled along

The unbroken song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Till ringing, singing on its way,

The world revolved from night to day,

A voice, a chime,

A chant sublime

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

Then from each black, accursed mouth

The cannon thundered in the South,

And with the sound

The carols drowned

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

It was as if an earthquake rent

The hearth-stones of a continent,

And made forlorn

The households born

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!

And in despair I bowed my head;

“There is no peace on earth,” I said;

“For hate is strong,

And mocks the song

Of peace on earth, good-will to men!”

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

“God is not dead, nor doth He sleep;

The Wrong shall fail,

The Right prevail,

With peace on earth, good-will to men.”

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers