Justin Taylor's Blog, page 55

March 15, 2016

My Conversation with David Mathis on the Habits of Grace

I recently had the privilege of sitting down with David Mathis—executive editor for Desiring God and pastor at Cities Church in the Twin Cities—to talk about his new book, Habits of Grace: Enjoying Jesus through the Spiritual Disciplines (with a group study guide sold separately).

Crossway provided some time-stamps for our conversation

00:00 – What do the endorsements for the book tell us about what you were trying to do in Habits of Grace?

02:21 – What are you getting at when you talk about “habits of grace”?

04:39 – In your experience, what are some of the main challenges that Christians face with respect to the “habits of grace”?

07:48 – When it comes to our intake of God’s Word, why is it important to emphasize both breadth and depth?

09:51 – How do we ensure that our understanding and practice of the spiritual disciplines is biblical and not unduly shaped by non-Christian influences?

13:04 – Where and how is the Holy Spirit present in your understanding of living the Christian life?

16:30 – With the multitude of books already in print related to the spiritual disciplines, why did you feel the need to write another one?

Endorsements

“This book is about grace-empowered habits, and Spirit-empowered disciplines. These are the means God has given for drinking at the fountain of life. They don’t earn the enjoyment. They receive it. They are not payments for pleasure; they are pipelines. All of us leak. We all need inspiration and instruction for how to drink—again and again. Habitually. If you have never read a book on ‘habits of grace’ or ‘spiritual disciplines,’ start with this one. If you are a veteran lover of the river of God, but, for some reason, have recently been wandering aimlessly in the desert, this book will be a good way back.”

“This book is about grace-empowered habits, and Spirit-empowered disciplines. These are the means God has given for drinking at the fountain of life. They don’t earn the enjoyment. They receive it. They are not payments for pleasure; they are pipelines. All of us leak. We all need inspiration and instruction for how to drink—again and again. Habitually. If you have never read a book on ‘habits of grace’ or ‘spiritual disciplines,’ start with this one. If you are a veteran lover of the river of God, but, for some reason, have recently been wandering aimlessly in the desert, this book will be a good way back.”

John Piper, Founder, desiringGod.org; Chancellor, Bethlehem College and Seminary

“Simple. Practical. Helpful. In Habits of Grace, Mathis writes brilliantly about three core spiritual disciplines that will help us realign our lives and strengthen our faith. In a world where everything seems to be getting more complicated, this book will help us to downshift and refocus on the things that matter most.”

Louie Giglio, Pastor, Passion City Church, Atlanta; Founder, Passion Conferences

“Although this little book says what many others say about Bible reading, prayer, and Christian fellowship (with two or three others tacked on), its great strength and beauty is that it nurtures my resolve to read the Bible and it makes me hungry to pray. If the so-called ‘means of grace’ are laid out as nothing more than duties, the hinge of sanctification is obligation. But in this case, the means of grace are rightly perceived as gracious gifts and signs that God is at work in us, which increases our joy as we stand on the cusp of Christian freedom under the glories of King Jesus.”

“Although this little book says what many others say about Bible reading, prayer, and Christian fellowship (with two or three others tacked on), its great strength and beauty is that it nurtures my resolve to read the Bible and it makes me hungry to pray. If the so-called ‘means of grace’ are laid out as nothing more than duties, the hinge of sanctification is obligation. But in this case, the means of grace are rightly perceived as gracious gifts and signs that God is at work in us, which increases our joy as we stand on the cusp of Christian freedom under the glories of King Jesus.”

D. A. Carson, Research Professor of New Testament, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School; Cofounder, The Gospel Coalition

“Most people assume that disciplined training is necessary for attaining any skill— professional, academic, or athletic. But for some reason, Christians do not see this principle applying to their Christian lives. In his excellent book, Habits of Grace, David Mathis makes a compelling case for the importance of the spiritual disciplines, and he does so in such a winsome way that will motivate all of us to practice the spiritual disciplines of the Christian life. This book will be great both for new believers just starting on their journey and as a refresher course for those of us already along the way.”

Jerry Bridges, author, The Pursuit of Holiness

“David Mathis has more than accomplished his goal of writing an introduction to the spiritual disciplines. What I love most about the book is how Mathis presents the disciplines—or ‘means of grace’ as he prefers to describe them—as habits to be cultivated in order to enjoy Jesus. The biblical practices Mathis explains are not ends—that was the mistake of the Pharisees in Jesus’s day and of legalists in our time. Rather they are means by which we seek, savor, and enjoy Jesus Christ. May the Lord use this book to help you place yourself ‘in the way of allurement’ that results in an increase of your joy in Jesus.”

Donald S. Whitney, Associate Professor of Biblical Spirituality, Senior Associate Dean of the School of Theology, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary; author, Spiritual Disciplines for the Christian Life

“So often, as we consider the spiritual disciplines, we think of what we must do individually. Mathis takes a different approach that is both insightful and refreshing. Along with our personal time of prayer and reading, we are encouraged to seek advice from seasoned saints, have conversations about Bible study with others, and pray together. The Christian life, including the disciplines, isn’t meant to be done in isolation. Mathis’s depth of biblical knowledge along with his practical guidance and gracious delivery will leave you eager to pursue the disciplines, shored up by the grace of God.”

Trillia Newbell, author, Enjoy, Fear and Faith, and United

“This is the kind of book I turn to periodically to help examine and recalibrate my heart, my priorities, and my walk with the Lord. David Mathis has given us a primer for experiencing and exuding ever-growing delight in Christ through grace-initiated intentional habits that facilitate the flow of yet fuller springs of grace into and through our lives.”

Nancy DeMoss Wolgemuth, author; radio host, Revive Our Hearts

“There is not a Christian in the world who has mastered the spiritual disciplines. In fact, the more we grow in grace, the more we realize how little we know of hearing from God, speaking to God, and meditating on God. Our maturity reveals our inadequacy. Habits of Grace is a powerful guide to the spiritual disciplines. It offers basic instructions to new believers while bringing fresh encouragement to those who have walked with the Lord for many years. It is a joy to commend it to you.”

Tim Challies, author, The Next Story; blogger, Challies.com

“When I was growing up, spiritual disciplines were often surrounded by an air of legalism. But today the pendulum has swung in the other direction: it seems that family and private devotions have fallen off the radar. The very word habits can be a turnoff, especially in a culture of distraction and autonomy. Yet character is largely a bundle of habits. Christ promises to bless us through his means of grace: his Word preached and written, baptism, and the Lord’s Supper. Like a baby’s first cry, prayer is the beginning of that life of response to grace given, and we never grow out of it. Besides prayer, there are other habits that grace motivates and shapes. I’m grateful for Habits of Gracebringing the disciplines back into the conversation and, hopefully, back into our practice as well.”

Michael Horton, J. Gresham Machen Professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics, Westminster Seminary California; author, Core Christianity: Finding Yourself in God’s Story

“David Mathis has given us a book on the spiritual disciplines that is practical, actionable, and accessible. He speaks with a voice that neither scolds nor overwhelms, offering encouragement through suggestions and insights to help even the newest believer find a rhythm by which to employ these means of grace. A treatment of the topic that is wonderfully uncomplicated and thorough, Habits of Grace offers both a place to start for beginners and a path to grow for those seasoned in the faith.”

Jen Wilkin, author, Women of the Word; Bible study teacher

“I am drawn to books that I know are first lived out in the messiness of life before finding their way onto clean sheets of paper. This is one of those books! David has found a well-worn path to Jesus through the habits of grace he commends to us. I am extremely grateful for David’s commitment to take the timeless message in this book and communicate it in language that is winsome to the mind and warm to the heart. This book has the breadth of a literature review that reads like a devotional. I am eager to get it into the hands of our campus ministry staff and see it being read in dorm rooms and student centers across the country.”

Matt Bradner, Regional Director, Campus Outreach

“David Mathis has provided us with a gospel-driven, Word-centered, Christ-exalting vision of Christian spiritual practices. Furthermore, he understands that sanctification is a community project: the local church rightly looms large in Habits of Grace. This book is perfect for small group study, devotional reading, or for passing on to a friend who is thinking about this topic for the first time. I give it my highest recommendation.”

Nathan A. Finn, Dean, The School of Theology and Missions, Union University

Table of Contents

Introduction: Grace Gone Wild

Part 1: Hear His Voice (Word)

Shape Your Life with the Words of Life

Read for Breadth, Study for Depth

Warm Yourself at the Fire of Meditation

Bring the Bible Home to Your Heart

Memorize the Mind of God

Resolve to Be a Lifelong Learner

Part 2: Have His Ear (Prayer)

Enjoy the Gift of Having God’s Ear

Pray in Secret

Pray with Constancy and Company

Sharpen Your Affections with Fasting

Journal as a Pathway to Joy

Take a Break from the Chaos

Part 3: Belong to His Body (Fellowship)

Learn to Fly in the Fellowship

Kindle the Fire in Corporate Worship

Listen for Grace in the Pulpit

Wash in the Waters Again

Grow in Grace at the Table

Embrace the Blessing of Rebuke

Part 4: Coda

The Commission

The Dollar

The Clock

Epilogue: Communing with Christ on a Crazy Day

You can read Piper’s foreword and Mathis’s preface here.

March 11, 2016

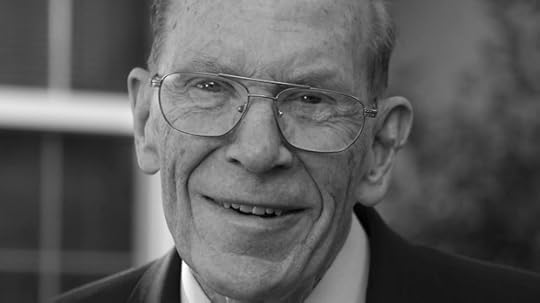

The Memorial Service for Jerry Bridges

The hour and a half memorial service for Jerry Bridges (1929-2016) was held today, Friday, March 11, 2016, at 2 pm (MT) at Village Seven Presbyterian Church. You can watch the entire service below:

If you would like to share with the Bridges family a favorite memory of Jerry or a story of how his writing impacted your life, Email feedback@navigators.org.

In lieu of flowers, gifts may be given to the Jerry Bridges Memorial Fund, or to his church, Village Seven Presbyterian Church in Colorado Springs. The memorial fund will be used to assist The Navigators Collegiate Ministry.

The Navigators

Attn: JERRY BRIDGES MEMORIAL FUND (24001100)

PO Box 6000

Colorado Springs, CO 80934

Navigator Donor Services: (866) 568-7827

Or you may give online at www.navgift.org/bridgesmemorial.

Village Seven Presbyterian Church

4055 S Nonchalant Cir

Colorado Springs, CO 80917

Or you may give to the church online.

For an obituary of Jerry Bridges—including links to his books and audio—go here.

March 8, 2016

A Wheaton Theology Professor Offers Wisdom in Light of the Wheaton Tragedy

If I walk up to my office window at Crossway Books and look across the railroad tracks to the west, I can see the campus of Wheaton College, including the distinctive white spire above the center named after its most famous alumnus, Billy Graham. Founded by evangelical abolitionists in 1860 “for Christ and his kingdom,” the school has garnered a reputation over the years as the Evangelical Harvard, seeking to show that a liberal arts college can combine rigorous academic training and faithful piety.

As many readers will know, Wheaton was embroiled in controversy from December 2015 to February 2016, centered around statements by political science professor Larycia Hawkins. Announcing on Facebook her plan to wear the hijab during Advent, she explained: “I stand in religious solidarity with Muslims because they, like me, a Christian, are people of the book. And as Pope Francis stated last week, we worship the same God.”

A firestorm of controversy ensued, fanned into flame by forces both inside and outside of the school. Though it was in the same town in which I work, I mainly followed the developments at a distance (that is to say, online), even offering my own modest proposal on the same-God debate.

We have not heard, however, from many faculty members inside Wheaton regarding their perspective on what happened or what we can learn from this difficult season for Wheaton. I am grateful, therefore, to share the following essay by Daniel J. Treier, Blanchard Professor of Theology at Wheaton College. Suggesting that this may be a ”‘teachable moment,’ not just for Wheaton specifically but more generally for Christians in higher education,” Dr. Treier calls the Christian community to consider how “four key features of biblical wisdom might help us to understand how Dr. Hawkins, Dr. Jones, parents, and professors could act in reasonably good faith yet reach a tragic outcome.”

More could be said here, but not less. For anyone who watched or commented on this tragedy—both from within and from outside—this is a wise essay worth carefully considering.

—Justin Taylor

The Wheaton Tragedy

Daniel J. Treier

March 9, 2016

Wheaton College (IL), where I have taught theology for fifteen years, recently endured a two-month media firestorm. Generally reliable details of the narrative are available via that bastion of truth, the Internet. In miniature: A tenured political science professor, Larycia Hawkins, was placed on administrative leave after asserting that Christians and Muslims worship the same God. This assertion appeared in a Facebook post explaining her decision to wear a hijab during Advent, expressing “embodied solidarity” with Muslim women prominently facing discrimination. As controversy ensued, Wheaton’s provost Stanton Jones believed that Dr. Hawkins did not provide adequate theological clarification of how her statements were consistent with the college’s evangelical statement of faith.

Subsequent conversations reached a stalemate while media coverage escalated. Dr. Jones initiated formal termination procedures that would commence with a review by the Faculty Personnel Committee. Already an overwhelming majority of the faculty opposed Dr. Hawkins’s termination, especially after she posted online a statement of theological clarification. Wheaton’s Faculty Council unanimously formalized a recommendation for Dr. Hawkins’s reinstatement, grounded in critique of administrative procedures. Supporters of Dr. Hawkins intensified various private and public campaigns. Additional faculty members, who previously shared some of the administration’s theological concerns or were undecided, came to support Dr. Hawkins’s immediate reinstatement, believing that her clarifying statement precluded any violation of a particular tenet of the statement of faith.

Advocacy on both sides reached a fever pitch of Facebook and Twitter salvos from professors, alumni, and pundits. Media stories proliferated internationally, partly because three Wheaton alumnae report on religion for national outlets. One of them publicized multiple confidential materials leaked by faculty members. Few cultural elites or Wheaton professors sympathized publicly with the administration’s concerns. Younger and more progressive alumni joined the administration’s critics in vocal support for Dr. Hawkins.

The Faculty Diversity Committee issued a private report that raised significant concerns about administrative procedures as well as racial and gender inequity affecting the case. Shortly thereafter Dr. Jones sent a detailed written apology to Dr. Hawkins. He revoked the termination proceedings and left the decision about reinstating Dr. Hawkins in the hands of Wheaton’s president, Philip Ryken. The Diversity Committee’s report leaked while Dr. Hawkins and Dr. Ryken were addressing the possibility of her reinstatement. Dr. Hawkins and Dr. Ryken reached a confidential agreement to end her employment at the college, at which point Dr. Jones’s apology was made public. A joint worship service and a joint press conference ensued.

Of course the controversy is not really over, regardless of whether media interest waxes or wanes. Months, even years, of rebuilding lie ahead. The college is left sifting through the rubble of its latest firestorm while grieving the loss of a treasured professor, and Dr. Hawkins was left to find a new place of service. (By the way, Dr. Hawkins is a valued colleague and family friend, but in this essay I use her academic title rather than operating on a first-name basis. She deserves every indication of the respect that chummy students sometimes deny to female professors in my conservative circles.) Rebuilding requires time for lament and space for grief, even expressions of anger. Early commentary requires restraint, recognizing the risk of damaging relationships we hope to heal.

Both Tragedy and Wisdom: A Neglected Perspective

Yet I offer this essay to commend a neglected perspective, worth considering before views harden so thoroughly that our rebuilding efforts cannot incorporate any alternatives. Thus far public commentary from my Wheaton colleagues has been overwhelmingly one-sided, for understandable reasons. If, however, those who grieve over Dr. Hawkins’s departure but sympathize with our administration’s theological concerns remain entirely silent, then rebuilding efforts will produce lopsided results.

Indeed, perhaps we face a “teachable moment,” not just for Wheaton specifically but more generally for Christians in higher education. Wheaton is far from the only school navigating the challenges of a social media age, the dramas of faculty advocacy, the limits of academic freedom, or perceived tensions between genuine diversity and confessional identity. Moreover, Wheaton’s treatment as an icon—by the media, the broader academy, and various stakeholders from both left and right—could mean that the recent controversy has larger consequences for the accreditation, finances, and politics of Christian higher education.

Most pundits have taken clear sides dominated by political, theological, or academic agendas—not to mention suspicion and sheer speculation. To state my alternative succinctly: What if the dominant categories for assessing this controversy should be the pair of “tragedy” and “wisdom”? What if we tried to imagine how each major stakeholder in the controversy could act in reasonably good faith yet contribute to a tragic outcome? And what if we tried to learn our lessons for the future from both the fragmentary wisdom and the limitations displayed by each?

I have been pondering how biblical wisdom addresses our communal life because of James 1:19-20: “My dear brothers and sisters, take note of this: Everyone should be quick to listen, slow to speak and slow to become angry, because human anger does not produce the righteousness that God desires” (NIV). These verses confronted my own slowness to listen (to certain people anyway), my speed in speaking (without adequate information), and my fiery self-righteousness. As a Christian liberal arts professor, I find it painful to be so unwise.

What if we listen—really listen, seeking the peaceable and teachable wisdom of James 3:17-18—to the perspectives of all the relevant stakeholders? Despite our differences, and the other relevant questions this essay brackets out, these stakeholders claim a shared commitment to Scripture’s authority. Thus four key features of biblical wisdom might help us to understand how Dr. Hawkins, Dr. Jones, parents, and professors could act in reasonably good faith yet reach a tragic outcome.

1. Listening and Speaking

Wisdom’s emphasis on the character of our listening and speaking especially helps us to examine Dr. Hawkins’s perspective. How many critics listened carefully to understand sympathetically what she sought to do? James, the New Testament’s Wisdom literature, prohibits self-righteous slander (4:11-12). Catechesis from the Ninth Commandment enjoins thinking and speaking as well of others as possible, even refraining from expressing justifiable criticism if we can. Dr. Hawkins’s critics frequently failed to honor God’s law in this way.

James 2 and 5 also apply, for they demonstrate that enduring wisdom and prophetic action are not automatically opposed. Hoping to demonstrate solidarity with a verbally, politically, and sometimes physically abused group, Dr. Hawkins championed marginalized persons that James prophetically defends. Unfortunately that solidarity resulted in verbal abuse of Dr. Hawkins, as some critics violated James 3 with particularly vile responses. If some of the concern was primarily political, then James 4:1-10 further applies: Were such critics really concerned for evangelical truth, or instead committing spiritual adultery with a cultural agenda?

Of course Dr. Hawkins was making a public statement in the first place, and she responded to the critics’ and administration’s publicity with more of her own. As the controversy ensued, some of her rhetoric about “Wheaton College,” while commendably avoiding personal attack by name, risked going beyond prophetic confrontation into casting many of the institution’s stakeholders in the worst possible light. Yet neither side backed down, each blaming the other for turning up the temperature. And it is important for those who cannot imagine responding as Dr. Hawkins did to attempt—however inadequately—to put ourselves in her shoes: a single, black female living in downtown Chicago, teaching at a white male-dominated suburban evangelical institution, confronting a post-Ferguson world. Before dismissing the rhetoric of “prophetic” response—about which I will express concerns below—we first should listen to the cries of the side James takes. Among reactions to Dr. Hawkins the partisan anger of worldly wisdom frequently trumped the listening ears, teachable heart, and peaceable spirit of Christian wisdom.

2. Prudence and Courage

Biblical wisdom prioritizes not only listening and speaking but also prudence and courage, helping us to examine the perspective of Wheaton’s administration. How many critics listened carefully to their concerns and imagined alternatives to their course of action? The challenges they faced highlight the necessity and limitations of prudence as well as its complex relation to courage.

Once discussions of the “same God” question moved beyond one-line sound bites, credible answers functionally involved both “yes” and “no” elements. Emphases varied to one side or the other, and some scholars tried to champion a simple “yes,” but then definitions of “worship” or “same” qualified even their claims. The confusion created among Wheaton’s constituency by the “yes” of Dr. Hawkins’s initial statement did not always stem from bigoted politics. In some contexts the statement could suggest a form of religious solidarity stemming from pluralism rather than evangelical clarity—although again it is important to account for context: Brother/sister language would have less freighted implications outside of white, Midwestern, evangelicalism. Eventually we need to address this pedagogical and contextual dimension of the controversy, but here we need to ponder the prudential dimension.

To begin with, the necessity and limitations of prudence: Dr. Jones’s apology indicated specific mistakes made in the process of dealing with his theological concerns. We should honor his courage and humility by acknowledging these mistakes, yet it remains illuminating to understand them as well-intentioned if naïve. For instance, given a complicated prior history with Dr. Hawkins, Dr. Jones initially approached her indirectly, through a faculty intermediary, which might have seemed like deft treatment but ended up seeming differential. Sometimes we fall victim to unexpected responses or unintended consequences.

Biblical wisdom, beginning with fear of the Lord, is moral and spiritual. For all its borrowing from other cultures, Proverbs transcends mere skills. Disregarding its speech ethics, for example, generally counts as folly—living as if there were no God and thereby fracturing the covenant community. It is frequently appropriate to seek forgiveness for failures to act wisely.

Nevertheless, the Bible also acknowledges the necessity and complexities of mundane prudence, which cannot always obtain desired results. Job 28 underscores the difficulty of finding wisdom, and Ecclesiastes underscores the difficulty of applying any wisdom we apparently have. Given the fallen way of the world from Genesis 3 on, not to mention our finitude, we cannot always anticipate the consequences of our actions. Perhaps we can rarely even make predictions with much reliability. How many of us would have done better in the provost’s shoes, facing a brave new social media world? Ill-informed character assassins simultaneously championed “reconciliation” yet felt free to allege bigotry, impute motives, and question opponents’ intelligence, whereas Dr. Hawkins rightly denounced demonizing Dr. Jones.

In hindsight, the administration might have created the necessary public distance from Dr. Hawkins’s statement by indicating concern and asking for patient trust without instantly imposing administrative leave. To those of us acquainted with institutions where Dr. Hawkins would have been summarily fired, administrative leave could appear moderate, making space for restorative outcomes; yet to many it was decidedly irregular, and to Dr. Hawkins it was understandably drastic. Even if administrative leave were the best course of action, it could have been handled better.

Not just the necessity and limitations of prudence are apparent, though; so is its complex relation to courage. Many, both inside and outside of the college, viewed its response pragmatically: Dr. Jones had to respond to an angry constituency, but he imprudently overreached, backing himself and Dr. Hawkins into a corner. More and more people took this line after Dr. Hawkins released her theological affirmation of the statement of faith.

Yet the obvious element of truth in this view should not eclipse the vital question of whether the theological concerns were merely pragmatic or potentially legitimate. Personally knowing Wheaton’s leaders to be driven primarily by conscience rather than consequences, I take seriously their signal that the concerns were not primarily pragmatic. Nor were they primarily technical, concerning some line item of the statement of faith or a monolithic institutional answer to the same-God question. By contrast, relatively few people have acknowledged that the concerns could be pedagogical, concerning—in our president’s prominent words—whether Dr. Hawkins adequately “affirmed and modeled” the evangelical heritage reflected in the statement of faith. This pedagogical concern further introduces the need for discerning courage among leaders in Christian higher education.

At first our administration apparently felt that courage required holding fast. They likely found it difficult to imagine a future in which tenured faculty members could essentially refuse to acknowledge the administration’s responsibility for shaping the institution’s theological identity. They likely found it difficult to imagine reinstating Dr. Hawkins without offering their constituency—parents in particular—a ringing theological endorsement. In the end, they apparently felt that courage required backing down to a degree. At minimum, the provost demonstrated courage in making his apology; as the saga continues, the administration has demonstrated courage in taking further public flak for the outcome, including continued suspicion from people who refuse to take either the president or the provost at their word.

The awkward intersection of prudence and courage especially confronts schools like Wheaton as they genuinely and deeply desire to have faculty and student diversity reflect the fullness of Christ’s global body. Yet their institutional histories and cultures impose perceived constraints on making professors and students from previously marginalized backgrounds feel truly at home. Administrators will need the prudence and courage to maintain their schools’ confessional integrity despite the occasional costs—refusing to concede that perceived tensions between authentic diversity and theological fidelity create a zero-sum game. Administrators will also need the prudence and courage to navigate legitimate, even essential, theological and cultural change despite internal and external opposition. They cannot amend statements of faith, or create supplemental do’s and don’ts, with every new potential controversy. Yet they must provide for apparent change precisely in order to perpetuate living rather than dead traditions, to maintain narrative continuity with the best of their past while helping students to encounter the fullness of global Christianity.

3. Tradition and Inquiry

Biblical wisdom further involves a pedagogical dialectic of tradition and inquiry, which helps us to examine the perspective of parents and other stakeholders. How many parents thought carefully about what is necessary to form wise students? How many of Wheaton’s critics thought holistically about this concern, rather than thinking that real education would leave students rather unfettered by the evangelical heritage?

Parents are legitimately interested in having Christian colleges teach their stated tradition(s) with integrity. So do other stakeholders such as alumni and additional donors. Thus Dr. Jones’s worries over theological confusion were not cravenly caving to donors but keeping a pedagogical covenant. Professors understandably worry about losing academic freedom, but focusing on publicly representing a statement of faith actually protects us. Our private belief-states vary frequently and wildly. If we fulfill our public responsibility to represent the institutional heritage embodied in our statement of faith, then administrators cannot properly act on speculation to the contrary. In the present case, a professor might have made a similarly controversial statement in a classroom or office without creating such public complications. In other cases, our administration routinely defends us from comparatively private student, parent, or donor complaints.

In return, however, such protection requires faculty stewardship—to relate academic freedom to Christian liberty, to pursue teaching and scholarship that represents a school’s heritage rather than taking license to reject its stated faith or despise its historic constituency. Since administrators have few tools—short of termination proceedings—for engaging tenured professors’ theological pedagogy, restraint and trust become essential on all sides. If professors want the freedom to be prophetic without being fired, in rare cases administrators may need the freedom either to seek clarification privately or else to support alternatives publicly.

If parents are legitimately interested in a school’s faithful teaching of its tradition(s), they are also responsible—in their students’ best interest—to foster robust inquiry. It is a dangerous myth of the late modern West that every student must undergo a collegiate crisis in order to “own” faith for themselves. Nevertheless, biblical wisdom makes ample space for inquiry that challenges tradition, fostering stronger adherents and deeper understanding of the faith. Some parents and students are more willing for schools to offer such space than others; indeed, Christian higher education offers an ecology of institutions with different amounts and kinds of space for inquiry. Administrators and professors must educate parents, students, and other stakeholders regarding both the need for inquiry and appreciation for the school’s tradition(s).

4. Prophecy and Pedagogy

Given this pedagogical dimension of the controversy, a final aspect of biblical wisdom helps us to examine the perspective of the faculty. How many of us pondered not only all the various perspectives highlighted above but also the long-term educational health of our institution? Or how substantial are our internal disagreements about what comprises educational health?

Some faculty members increasingly sounded like they were criticizing not just the administration’s actions or underlying concerns, but even the school’s heritage itself—as if by implication evangelicalism is so tainted by racism and sexism as to be unredeemable. Moreover, some faculty members were so convinced of their cause that they leaked confidential documents or implied a lack of good faith and intelligence on the part of anyone sharing the administration’s concerns. A colleague’s silence rather than advocacy became subject to curiosity, then speculation, and ultimately peer pressure.

Moving forward involves the obvious challenge of rebuilding faculty-to-administration relationships. Yet we face subtler challenges of rebuilding faculty-to-faculty relationships: restoring governance that incorporates all colleagues; that does not generate a social media circus whenever someone doesn’t get their way; that involves meaningful deliberation without leaked communication; that, indeed, rejects the media claim that no campus event is entitled to any privacy at all. Vocal faculty members have suggested that fear of the administration suppresses academic freedom, but they have not acknowledged the possibility that strident advocacy suppresses freedom and generates fear among their colleagues.

Faculty advocacy in this case signals not just governance challenges but also a larger educational issue. Both sages and prophets may have had “schools” in biblical times; if so, unfortunately, the schools largely fostered false prophets, whereas the true ones were typically isolated and persecuted. Today, as evangelicals in higher education freshly promote social justice, do we risk virtually identifying education with advocacy? To what degree does taking up a prophetic mantle leave us so convinced of our causes that we refuse to engage critique, freely indoctrinating students in our own activism rather than educating them about alternatives or exploring underlying causes? To what degree does the prophetic advocate inherently demonize anyone who disagrees?

Older models of educational detachment were not pervasively neutral but actually reinforced certain powers that be. Yet the current emphasis on prophetic advocacy threatens to reject not only tradition as such but also a considerable degree of what passes for inquiry. My colleagues and I need to face the extent of our differences with each other, not just the administration. While our differences do not affect hiring and firing as overtly, they do so covertly—raising fundamental questions of not just what to teach but even what it means to teach.

Technical definitions aside, “prophets” are sometimes necessary. Evil becomes so entrenched that dramatic confrontation is required. But educational institutions are by definition oriented to wisdom rather than prophecy. Earlier, often ill-informed, evangelical activism exacerbated our movement’s contributions to injustice. So an educational community periodically needs prophetic confrontation. Even so, aside from rather clear and direct divine mandates, “prophets” need wisdom. Perhaps understandably, in this case Dr. Hawkins prioritized prophetic confrontation over pedagogical alternatives for addressing our conservative constituency, thus defining the possibility of “reconciliation” on her terms. In likewise making prophecy their pedagogy, at least some faculty members mirrored the administration in leaving untried any longer path of quiet diplomacy. Other vital considerations, such as missiology, became rhetorical pawns in a war rather than guideposts on a genuine quest for insight. Perhaps controversy was inevitable and confrontation essential; but, tragically, the opportunity to educate our constituency and our ability to reason together have diminished substantially.

Two Final Challenges

Will this Wheaton tragedy foster any newfound wisdom? I have tried to indicate how the actions of all parties could involve good faith and fragmentary wisdom despite the tragic outcome. If so, then our primary focus should not be fighting over the assignment of blame but seeking mutual growth in wisdom. All the same, we must be sober about two final aspects of our challenging circumstances.

First, “Christian liberal arts” education may be more effective at conveying intellectual skills and professional success than fostering wisdom. Extreme right-wing and left-wing rhetoric is not isolated among alumni. It is hard to quantify how many people quietly engaged thoughtful perspectives rather than jumping to conclusions, but a distressing proportion of the visible responses from all Wheaton stakeholders violated James 1:19-21. Four years of education can only do so much, but unfortunately the alumni reaction matches the mixed character of the response from me and my colleagues.

Second, significant aspects of the Wheaton tragedy parallel surrounding controversies throughout higher education. The increasing animosity between boards, administrators, and faculties; the new orthodoxy of advocacy; the resulting chaos when demands for justice clash with established educational protocols; the harshness of our disputes—such realities suggest that Christians are far from immune to surrounding trends.

Our president rightly insists that Wheaton needs the gospel more than anyone. Ultimate hope rests in the resurrection, of which the deaths of two treasured colleagues poignantly reminded our community last November. More proximate hope appears in glimpses of grace and wisdom that peeked through the stormy clouds of recent months. Yet Wheaton offers a very visible case study regarding the challenges of a social media age, which makes it all the harder to overcome systemic brokenness while sustaining an educational tradition of Christian wisdom.

Daniel J. Treier (PhD, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School) is Blanchard Professor of Theology at Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois.

He is the coeditor of nine books and author of four, including Virtue and the Voice of God (Eerdmans, 2006) and Introducing Theological Interpretation of Scripture (Baker Academic, 2008).

His most recent work, co-authored with Kevin Vanhoozer, is the inaugural volume in the series Studies in Christian Doctrine and Scripture: Theology and the Mirror of Scripture: A Mere Evangelical Account (IVP Academic, 2015).

The God-Centered Ground for Making Room for Atheism in the Public Square

God himself is the foundation for our commitment to a pluralistic democratic order—not because pluralism is his ultimate ideal, but because in a fallen world, legal coercion will not produce the kingdom of God. Christians agree to make room for non-Christian faiths (including naturalistic, materialistic faiths), not because commitment to God’s supremacy is unimportant, but because it must be voluntary, or it is worthless. We have a God-centered ground for making room for atheism. “If my kingship were of this world, my servants would fight” (John 18:36). The fact that God establishes his kingdom through the supernatural miracle of faith, not firearms, means that Christians in this age will not endorse coercive governments—Christian or secular.

This is why we resist the coercive secularization implied in some laws that repress Christian activity in public places. It is not that we want to establish Christianity as the law of the land. That is intrinsically impossible, because of the spiritual nature of the kingdom. It is rather because repression of free exercise of religion and persuasion is as wrong against Christians as it is against secularists. We believe this tolerance is rooted in the very nature of the gospel of Christ. In one sense, tolerance is pragmatic: freedom and democracy seem to be the best political order humans have conceived. But for Christians it is not purely pragmatic: the spiritual, relational nature of God’s kingdom is the ground of our endorsement of pluralism, until Christ comes with rights and authority that we do not have.

You can read the whole thing here.

March 6, 2016

Jerry Bridges (1929-2016)

Jerry Bridges entered into the joy of his Master this Sunday evening, March 6, 2016. He was 86 years old.

He suffered cardiac arrest on Saturday morning en route to the emergency room at Penrose Hospital in Colorado Springs. A medical team performed CPR for 20 minutes, but his brain function was very compromised, with the result that he was placed on life support. Life support was removed after family was able to say their final earthly goodbyes.

Childhood

Gerald D. Bridges was born on December 4, 1929, in a cotton-farming home in Tyler, Texas, to fundamentalist parents, six weeks after the Black Tuesday stock market crash that led to the Great Depression.

Jerry was born with several disabilities: cross-eyed and deaf in his right ear (which was not fully developed), along with spine and breastbone deformities. But given his family’s poverty, they were unable to afford medical care for these challenges.

His mother passed away in 1944 when he was 14.

Conversion

In 1948, as an 18-year-old college student right before his sophomore year began, Jerry was home alone one night and acknowledged to the Lord that he was not truly a Christian, despite growing up in a Christian home. The next week in his dorm room at the University of Oklahoma he was working on a school assignment and reached for a textbook, happening to notice the little Bible his parents had given him in high school. He figured that since he was now a Christian, he ought to start reading it daily, which he did (and never stopped doing so for the rest of his days).

The Navy

After graduating with an engineering degree on a Navy ROTC scholarship, he went on active duty with the Navy, serving as an officer during the Korean conflict (1951-1953). A fellow officer invited him to go to a Navigator Bible study. Jerry went and he was hooked. He had never experienced anything like this before.

When stationed on ship in Japan, he got to know several staff members of the Navigators quite well. One day, after Jerry had been in Japan for six months, a Navy worker asked him why he didn’t just throw in his lot with the Navigators and come to work for them. The very next day Jerry failed a physical exam due to the hearing loss in his right ear, and he was given a medical discharge after being in the Navy for only two years. Jerry was not overly disappointed, surmising that perhaps this was the Lord’s way of steering him to the Navigators.

When he returned to the U.S., he began working for Convair, an airplane manufacturing company in southern California, writing technical papers for shop and flight line personnel. It was there that he learned to write simply and clearly—skills the Lord would later use to instruct and edify thousands of people from his pen.

The Navigators

Jerry was single at the time, living in the home of Navigator Glen Solum, a common practice in the early days of The Navigators. In 1955 Jim invited Jerry to go with him to a staff conference at the headquarters of The Navigators in Glen Eyrie at Colorado Springs. It was there that Jerry sensed a call from the Lord to be involved with vocational ministry. He was resistant to the idea of going on staff, but felt conviction and prayed to the Lord, “Whatever you want.” The following day he met Dawson Trotman, the 49-year-old founder of The Navigators, who wanted to interview Jerry for a position, which he received and accepted. Jerry was put in charge of the correspondence department—answering letters, handling receipts, and mainly the NavLog newsletter to supporters.

When Trotman died in June of 1956 (saving a girl who was drowning), Jim Downing took a position equivalent to a chief operations operator. A Navy man, Jim Downing knew that Jerry had also served in the Navy and tapped him to be his assistant.

Jerry struggled at times in his role, unsure if this was his calling since his position was so different from the typical campus reps. After ten years on staff he told the Lord, “I’m going to do this for the rest of my life. If you want me out of The Navigators you’ll have to let me know.”

In the early 1960s Jerry served for three years in Europe as administrative assistant to the Navigators’ Europe Director. In 1963, at the age of 34, he married his first wife, Eleanor Miller of The Navigators following a long-distance relationship. Two children followed: Kathy in 1966, and Dan in 1967. From 1965 to 1969 Jerry served as office manager for The Navigators’ headquarters office at Glen Eyrie.

From 1969 to 1979 Jerry served as the Secretary-Treasurer for The Navigators. It was during this time that NavPress was founded in 1975. Their first publications began by transcribing and editing audio material from their tape archives and turning them into booklets. They produced one by Jerry on Willpower and Leroy Eims—who started the Collegiate ministry—encouraged Jerry to write. Jerry had been teaching at conferences on holiness, so he suggested a book along those lines. In 1978, NavPress published The Pursuit of Holiness , which has now sold over a million copies. Jerry assumed it would be his only book. A couple of years later, after reading about putting off the old self and putting on the new self from Ephesians 4, he decided to write The Practice of Godliness—on developing a Christlike character. That book went on to sell over a half a million copies.

Jerry served as The Navigators’ Vice President for Corporate Affairs from 1979 to 1994. It was in this season of ministry that Eleanor developed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. She went to be with the Lord just three weeks after their 25th wedding anniversary. The following year Jerry married Jane Mallot, who had known the Bridges family since the early ’70s.

Jerry’s final position with The Navigator’s was in the area of staff development with the Collegiate Mission. He saw this ministry as developing people, rather than teaching people how to do ministry. In addition to his work with The Navigators, he also maintained an active writing and teaching ministry, traveling the world to instruct and equip pastors and missionaries and other workers through conferences, seminars, and retreats.

In 2014, Jerry published a memoir of his life, tracing the providential hand of God through his own story: God Took Me by the Hand: A Story of God’s Unusual Providence (NavPress, 2014). He closes the work with seven spiritual lessons he learned in his six decades of the Christian life:

The Bible is meant to be applied to specific life situations.

All who trust in Christ as Savior are united to Him in a loving way just as the branches are united to the vine.

The pursuit of holiness and godly character is neither by self-effort nor simply letting Christ “live His life through you.”

The sudden understanding of the doctrine of election was a watershed event for me that significantly affected my entire Christian life.

The representative union of Christ and the believer means that all that Christ did in both His perfect obedience and His death for our sins is credited to us.

The gospel is not just for unbelievers in their coming to Christ.

We are dependent on the Holy Spirit to apply the life of Christ to our lives.

His last book, The Blessing of Humility: Walk within Your Calling, will be published this summer by NavPress.

Legacy

One of the great legacies of Jerry Bridges is that he combined—to borrow some titles from his books—the pursuit of holiness and godliness with an emphasis on transforming grace. He believed that trusting God not only involved believing what he had done for us in the past, but that the gospel empowers daily faith and is transformative for all of life.

In 2009 he explained to interviewer Becky Grosenbach the need for this emphasis within the culture of the ministry he had given his life to:

When I came on staff almost all the leaders had come out of the military and we had pretty much a military culture. We were pretty hard core. We were duty driven. The WWII generation. We believed in hard work. We were motivated by saying “this is what you ought to do.” That’s okay, but it doesn’t serve you over the long haul. And so 30 years ago there was the beginning of a change to emphasize transforming grace, a grace-motivated discipleship.

In the days ahead, many will write tributes of this dear saint. I would not be able to improve upon the reflections and remembrances of those who knew him better than I did. But I do know that he received from the Lord the ultimate acclamation as he entered into the joy of his Master and received the words we all long to hear, “Well done, my good and faithful servant.” There was nothing flashy about Jerry Bridges. He was a humble and unassuming man—strong in spirit, if not in voice or frame. And now we can rejoice with him in his full and final healing as he beholds his beloved Savior face to face. Thank you, God, for this man who helped us see and know you more.

Here are some resources from Desiring God in conversations from a few years ago where they sought to capture from Jerry what he has learned and how he would counsel believers to grow in grace:

Jerry Bridges wrote more than 20 books over the course of nearly 40 years:

The Pursuit of Holiness (NavPress, 1978)

The Practice of Godliness (NavPress, 1983)

True Fellowship (NavPress, 1985) [later published as The Crisis of Caring (P&R, 1992); finally republished as True Community (NavPress, 2012)]

Trusting God (NavPress, 1988)

Transforming Grace (NavPress, 1991)

The Discipline of Grace (NavPress, 1994)

The Joy of Fearing God (Waterbrook, 1999)

I Exalt You, O God (Waterbrook, 2000)

I Give You Glory, O God (Waterbrook, 2002)

The Gospel for Real Life (NavPress, 2002)

The Chase (NavPress, 2003) [taken from Pursuit of Holiness]

Growing Your Faith (NavPress, 2004)

Is God Really in Control? (NavPress, 2006)

The Fruitful Life (NavPress, 2006)

Respectable Sins (NavPress, 2007) [student edition, 2013]

The Great Exchange [co-authored with Bob Bevington] (Crossway, 2007)

Holiness Day by Day (NavPress, 2008) [a devotional drawing from his earlier writing on holiness]

The Bookends of the Christian Life [co-authored with Bob Bevington] (Crossway, 2009)

Who Am I? (Cruciform, 2012)

The Transforming Power of the Gospel (NavPress, 2012)

31 Days Toward Trusting God (NavPress, 2013) [abridged from Trusting God]

God Took Me by the Hand (NavPress, 2014)

The Blessing of Humility: Walk within Your Calling (NavPress, 2016)

March 3, 2016

What Would Would It Look Like If Christians Took the Ninth Commandment Seriously?

If they did, it might look something like what the Westminster Divines outlined in the Westminster Larger Catechism’s answer on the duties required of the ninth commandment (“”You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor”).

Question 144: What are the duties required in the ninth commandment?

Answer: The duties required in the ninth commandment are,

the preserving and promoting of truth between man and man, and the good name of our neighbor, as well as our own;

appearing and standing for the truth;

and from the heart, sincerely, freely, clearly, and fully, speaking the truth, and only the truth, in matters of judgment and justice, and in all other things whatsoever;

a charitable esteem of our neighbors;

loving, desiring, and rejoicing in their good name;

sorrowing for, and covering of their infirmities;

freely acknowledging of their gifts and graces, defending their innocency;

a ready receiving of a good report, and unwillingness to admit of an evil report, concerning them;

discouraging tale-bearers, flatterers, and slanderers;

love and care of our own good name, and defending it when need requireth;

keeping of lawful promises;

studying and practicing of whatsoever things are true, honest, lovely, and of good report.

March 1, 2016

Joni Eareckson Tada on John Piper’s Lessons from a Hospital Bed

John Piper’s newest little book is short and inexpensive and designed to be given away to those wanting not to waste their hospital stay.

Here is Joni Eareckson Tada’s foreword:

I know hospitals. I wish I didn’t, but over the years I’ve become all too acquainted with their stale corridors and freezing-cold operating rooms. It started back in 1967 when a reckless dive into shallow water snapped my neck, leaving me a quadriplegic. When they rushed me to the hospital on that hot July afternoon, I had no idea I wouldn’t be discharged until April 1969.

One morning I was lying on a gurney in the hallway outside the urology clinic. After two hours of waiting and counting ceiling tiles, a lab worker came through the doors to announce I would be “first after lunch break.” I moaned. My shoulders were already hurting from lying flat so long. As the urology staff headed to the cafeteria, my heart sank. More to the point, I nearly choked in a flood of fear and claustrophobia.

Crying was out. There was no one around to wipe my tears. So I decided to comfort my soul with a hymn. In no more than a whisper, I sang a favorite from church choir:

Be still, my soul: the Lord is on thy side.

Bear patiently the cross of grief or pain.

Leave to thy God to order and provide;

In every change he faithful will remain.

Be still, my soul: thy best, thy heavenly Friend

Through thorny ways leads to a joyful end!

I was only seventeen years old, or maybe eighteen, but that moment defined how I would engage life in a hospital. My stay would not be a jail sentence. Come hell or high water, I determined that this hospital would be, well, a gymnasium for my soul, a proving ground for my faith, and a mission field for God.

Sound improbable for a teenager? It is. And looking back, it was. Yet I was enough of a Christ follower to know I had to hold onto biblical hope, or else I would go crazy. Yes, I was still wrestling against depression, still struggling with how to actually live without the use of my hands or legs—even after I was released from the hospital in 1969. But I would not allow myself to sink into despair. That small, resolute act made all the difference, not only then but also years later when I battled stage 3 cancer and chronic pain.

This is why I love the little book you are holding in your hands. You may think its chapters are too short to carry any real weight, but they are perfectly pithy: wisdom delivered through a peashooter. In Lessons from a Hospital Bed, John Piper does not have to vet himself as a seasoned navigator of hospitals (much like good ob-gyns never have to give birth to a baby). His credentials come from his Spirit-breathed ability to tell you what’s prudent—what the right thing to do is with all the hours you’ll log while languishing in your hospital bed.

So please, don’t plow through this booklet too quickly. Read its lessons prayerfully and act on their counsel intentionally. Next to your Bible, this little book is your best guide in making certain your hospital stay does genuine good for your soul.

As John has often said, “Don’t waste your suffering.” And friend, I trust his Lessons from a Hospital Bed will help you avoid doing just that during your time in the hospital. It’s not a jail—it’s a gymnasium. So flip the page and get started. And may God’s healing hand of grace rest on you during your illness.

Joni Eareckson Tada

Joni and Friends International Disability Center

Fall 2015

You can get the book here, and read an excerpt at the Crossway site.

For bulk orders, this is your best option.

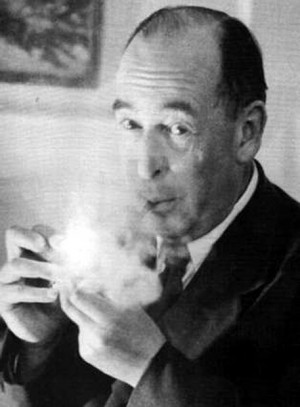

C. S. Lewis: “You Have Never Talked to a Mere Mortal”

C. S. Lewis:

C. S. Lewis:

It may be possible for each to think too much of his own potential glory hereafter; it is hardly possible for him to think too often or too deeply about that of his neighbor.

The load, or weight, or burden of my neighbor’s glory should be laid daily on my back, a load so heavy that only humility can carry it, and the backs of the proud will be broken.

It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare.

All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations.

It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics.

There are no ordinary people.

You have never talked to a mere mortal.

Nations, cultures, arts, civilization—these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat.

But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit—immortal horrors or everlasting splendors.

This does not mean that we are to be perpetually solemn.

We must play.

But our merriment must be of that kind (and it is, in fact, the merriest kind) which exists between people who have, from the outset, taken each other seriously—no flippancy, no superiority, no presumption.

And our charity must be real and costly love, with deep feeling for the sins in spite of which we love the sinner—no mere tolerance or indulgence which parodies love as flippancy parodies merriment.

Next to the Blessed Sacrament itself, your neighbor is the holiest object presented to your senses.

—C. S. Lewis, The Weight of Glory (reprint, HarperOne, 2001), pp. 45-46.

February 29, 2016

An FAQ on Nominating and Electing the President of the United States

Over at TGC Joe Carter has a helpful FAQ, asking (and answering) the following questions:

How Presidential Nominees Are Selected

How are presidential candidates chosen?

How are delegates chosen?

What is a “superdelegate”?

How are delegates allocated among candidates?

What the difference between a primary and a caucus?

What is “Super Tuesday”?

What is the “SEC Primary”?

When are the remaining primaries and caucuses?

How the President of the United States Is Elected

Do we vote for the President?

Where did the Electoral College system come from?

Who decides how many electoral votes each state receives?

How do these electoral votes decide who becomes President?

Who are these electors?

Do the electors have to vote for the candidate who received the most votes in their state?

How many electoral votes are needed to win?

Wouldn’t relying on the popular vote be a better system?

You can read it here.

February 24, 2016

C.S. Lewis’s Poem, “What the Bird Said Early In The Year”

On an early Sunday morning, September 20, 1931, 32-year-old C.S. Lewis (Fellow and Tutor of English Literature at Magdalen College, Oxford), 39-year-old J.R.R. Tolkien (Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford), and 35-year-old Hugo Dyson (Tutor and Lecturer at Reading University) took a walk together on Addison’s Walk in the grounds of Magdalen College at the University of Oxford. Their time together had begun the night before at dinner, but their conversation continued late into the night. After Tolkien left around 3 a.m., Lewis and Dyson continued talking until they retired at 4 a.m.

Two days later (Tuesday, September 22), Lewis recounted the scene to his longtime friend, Arthur Greeves:

We began on metaphor and myth—interrupted by a rush of wind which came so suddenly on the still, warm evening and sent so many leaves pattering down that we thought it was raining. We all held our breath, the other two appreciating the ecstasy of such a thing almost as you would. We continued (in my room) on Christianity: a good long satisfying talk in which I learned a lot: then discussed the difference between love and friendship—then finally drifted back to poetry and books.

Later in the letter, writing about the writings of William Morris, Lewis notes:

These hauntingly beautiful lands which somehow never satisfy,—this passion to escape from death plus the certainty that life owes all its charm to mortality—these push you on to the real thing because they fill you with desire and yet prove absolutely clearly that in Morris’s world that desire cannot be satisfied.

The [George] MacDonald conception of death—or, to speak more correctly, St Paul’s—is really the answer to Morris: but I don’t think I should have understood it without going through Morris. He is an unwilling witness to the truth. He shows you just how far you can go without knowing God, and that is far enough to force you . . . to go further.

The following month (October 18), Lewis wrote to Greeves again about their conversation:

Now what Dyson and Tolkien showed me was this: that if I met the idea of sacrifice in a Pagan story I didn’t mind it at all: again, that if I met the idea of a god sacrificing himself to himself . . . I liked it very much and was mysteriously moved by it: again, that the idea of the dying and reviving god (Balder, Adonis, Bacchus) similarly moved me provided I met it anywhere except in the Gospels. The reason was that in Pagan stories I was prepared to feel the myth as profound and suggestive of meanings beyond my grasp even tho’ I could not say in cold prose ‘what it meant’.

Now the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened.

(You can find an imaginative reconstruction of their conversation here.)

Years later Lewis wrote a poem entitled “What the Bird Said Early in the Year,” which not coincidentally is set in Addison’s Walk, and has to do with a spell becoming undone. Let him who has ears to hear, hear.

I heard in Addison’s Walk a bird sing clear:

This year the summer will come true. This year. This year.

Winds will not strip the blossom from the apple trees

This year, nor want of rain destroy the peas.

This year time’s nature will no more defeat you,

Nor all the promised moments in their passing cheat you.

This time they will not lead you round and back

To Autumn, one year older, by the well-worn track.

This year, this year, as all these flowers foretell,

We shall escape the circle and undo the spell.

Often deceived, yet open once again your heart,

Quick, quick, quick, quick!—the gates are drawn apart.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers